Introduction

The Italian geographer Paolo D’Agostino Orsini di Camerota opened his 1934 book, which he gave the title Eurafrica, by writing that ‘One finds these days a great deal of talk of Eurafrica’. 1 This statement is remarkable when we consider that Eurafrica had only begun to be used as a political term five years earlier. Nor was D’Agostino Orsini di Camerota overstating the case: in those five short years, a number of influential books had been published on the topic, rendering what had so recently appeared an awkward neologism into a commonplace, found everywhere from textbooks of geopolitics to speculative science-fiction.Reference Sörgel 2 From nowhere, ‘Eurafrica’ had become ubiquitous, and the ideology behind it had seeped into the popular consciousness: as Peo Hansen and Stefan Jonsson argue, ‘the general idea of an internationalization and supranationalization of colonialism in Africa was one of the least controversial and most popular foreign policy ideas of the interwar period’.Reference Hansen and Jonsson 3 While anti-colonial sentiment strongly critical of these schemes was also expressed in some quarters, 4 and African opinions on the matter were entirely ignored, Eurafrica offered a way of reconciling the regressive exploitation inherent in colonialism with the purportedly progressive notion of internationalist politics.

In this article, I focus on the development of the idea of Eurafrica in the literature of both the man and the organisation that coined it: Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi and the Pan-European Union he founded and ran. This organisation, launched in 1923 with the publication of Coudenhove-Kalergi’s programmatic book Pan-Europe,Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi 5 established national chapters in all European states in order to lobby for the creation of a Pan-European Union. As we shall see, this Union would include Europe’s African colonies, thus forming what was from 1929 onwards described as ‘Eurafrica’. While neither the first nor the only organisation calling for a federal link between the states of Europe, the Pan-European Union was the most popular of these organisations in the interwar period. Moreover, Coudenhove-Kalergi’s vision was the most readily associated with the incorporation of African territory as an integral part of a continental-scale ‘European’ political project. By co-opting Europe’s colonial present, Coudenhove-Kalergi and the like-minded writers he published in the Paneuropa journal sketched out a distinctive colonial future within his vision of the new planetary geopolitics, a third path that fell somewhere between the Mandate-based liberal internationalism of the League of Nations and what Alfred Zimmern called ‘The Third British Empire’.Reference Zimmern 6 After the Second World War, Eurafrica would become most intimately associated with the French efforts to reconcile its own colonial empire with participation in European political integration, before being appropriated as shorthand for the trade agreements signed in Yaoundé (1963 and 1969) and Lomé (1975) between European and African states.Reference Liniger-Goumaz 7 My case here is that, in its original expression, Eurafrica was not only far more explicitly imperialist and Eurocentric than its invocation at Yaoundé and Lomé might suggest; it was also less exclusively tied to the story of French colonialism. Rather, a central element of the case for Eurafrica in the interwar period was the promise of Central European participation in colonialism.

For Pan-Europeans, Eurafrica was a multifaceted entity, justified on multiple grounds. They argued that it would rationalise resources and trade in such a way that Europe would gain access to raw materials, and Africa would gain access to a market by which it might profit from these riches. They also claimed that it would resolve population pressures, as citizens of ‘overpopulated’ European states could re-settle in ‘underpopulated’ Africa, undertake infrastructural projects that would help develop lands previously thought be inhospitable, and oversee the education of the local population. These logics were presented in technical terms, and were justified statistically by recourse to simplistic metrics such as land area and population. Africa’s large landmass was held to signify resource richness, its low population density was interpreted as an inability to make the most of this land (and hence an invitation to colonisation), and Europe’s high population density as a ‘pressure’ that needed releasing through emigration.

However, complementing these purportedly technical justifications was a parallel argument framed in ‘moral-historical’ terms, which offered a share in the colonial experience to those European nations who had either had their colonies stripped at Versailles (i.e. Germany), or through ‘historical accident’ had never possessed colonies. Coudenhove-Kalergi argued that without a Eurafrican solution, European states would soon be caught between the external danger of expansionist superpowers in a closed world, and the internal danger of intra-European political tension between colony-owning and non-colony-owning states. With Eurafrica, both these dangers would be averted, to the advantage of all European states:

To the European colonial Powers would be guaranteed the possession of their colonies, which, in isolation, they would sooner or later be bound to lose to World Powers.

On the other hand, those European peoples who, as the result of their geographical position and historical destiny, did not receive fair treatment at the time when the extra-European world was divided up—such as Germans, Poles, Czechs, Scandinavians, and Balkan peoples—would find, in the great African colonial empire, a field for the release of their economic energies. (Ref. Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi5, pp. 178–179)

This paper digs into this ‘moral-historical’ justification for Eurafrica, examining the context in which it was made, and asking to what extent we ought to view the Eurafrican promise of Central European colonial access as a radical alternative to the Mandate system of the League of Nations, a re-visioning of internationalism that would make it compatible with (and thus harness the power of) fascist-colonial thought. 8

Eurafrica and the Pan-European Union

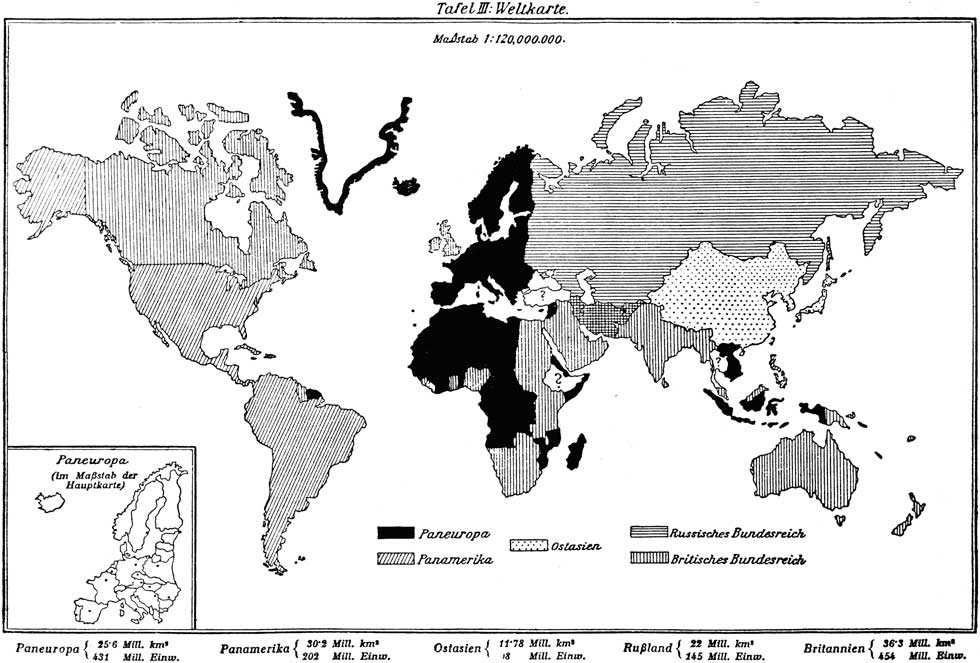

Although the Pan-European Union did not employ the specific term ‘Eurafrica’ until 1929, as an idea it was immediately obvious in the PEU’s most influential and widespread piece of propaganda: the Pan-European World Map (see Figure 1). This map was featured on a wide range of Pan-European literature and propaganda, perhaps most visibly as the rear cover of the majority of the issues of the monthly Paneuropa journal, from its very first issue, in 1924, until 1938, its cartography essentially unchanged throughout. It arrestingly depicted Coudenhove-Kalergi’s description of a ‘Pan-Europe’ that straddled the Mediterranean, bounded to the east by a line running south from Petsamo (on the Finno-Russian border) to Katanga (the south-easternmost province of the Belgian Congo) and to the west by the Atlantic Ocean (excluding the British Isles), thus forming what Coudenhove-Kalergi called ‘a clear-cut geographical unit … based on a common civilization, a common history and common traditions’.Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi 9 Coloured black and unsullied by internal state borders, this block stood proud of the various forms of hatching that marked the other four global power-blocs. It was, in short, the clearest possible visual statement of the unity of Europe with its African colonies in a supra-national, Pan-European whole.

Figure 1 The Pan-European world map (Archivní kolekce Coudenhove-Kalergi, Muzeum Chodska, Domažlice, Czech Republic).

The specifics were made clear in the book that launched the movement, Coudenhove-Kalergi’s 1923 Pan-Europe. When coming to terms with the extent of Pan-Europe, measured in terms of area and population, Coudenhove-Kalergi was clear that the colonies were to form an integral part of his vision of European unification:

the European territories of the Pan-European state-group form but a fraction of its power-complex. In order rightly to estimate the future possibilities of Pan-Europe, its colonies must also be taken into account. (Ref. Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi5, pp. 32–33)

He further distinguished between ‘Pan-Europe’s continuous empire in Africa’ and ‘Pan-Europe’s scattered colonies’, implicitly prioritising the former. Indeed, the weight placed on ‘continuous empire’ is made clear by suggestions for a rationalisation of territories, which included ‘Colonial readjustment in Africa by an exchange of England’s West African colonies for equally valuable East African colonies belonging to Europe’, and the selling off of Pan-Europe’s ‘scattered’ American colonies (i.e. French Guiana and Suriname) (Ref. Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi5, pp. 48-49). In short, from the very start of the Pan-European movement, Europe’s shared African colonies were integral to the organisation’s plans. They gave Pan-Europe the territory to form a rough balance of power with competing continental blocs, the land and resources to be economically self-sufficient, and the means to resolve the internal grievances and demographic pressures of European states.

This vision of Europe united with its African empire was given the name ‘Eurafrica’ in Coudenhove-Kalergi’s lead article to the February 1929 edition of the organisation’s Paneuropa journal, the first article in the journal to take Europe’s African colonies as its sole focus.Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi 10 (Edited versions of this article were also issued as a press release around the same time, in German, French and English.Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi 11 ) Indulging in a series of geographical metaphors, and scale-jumping with abandon, Coudenhove-Kalergi began by comparing Europe to the United States:

Africa is our South America.

Africa is the tropical Europe. Gibraltar is our Panama. Politically, West Africa is the southern continuation of Europe beyond these straits.

Europe is a house with many apartments and many tenants – but Africa is its garden. Whereas the Soviet Union separates us from Asia, and the Atlantic Ocean separates us from America – the Mediterranean connects Europe and Africa more than it separates them. So Africa has become our closest neighbour and its destiny a part of our own destiny.

From this perspective Pan-Europe is enlarged to Eurafrica – from the small Pan-Europe to a large political continent, stretching from Lapland to Angola, comprising 21 million kmReference Sörgel 2 and 360 million people. In the foreseeable future it will be possible to cross this continent under the Straits of Gibraltar with the railroad.

…Europe is the head of Eurafrica – Africa its body. The future of Africa depends on what Europe makes of it. (Ref. Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi10, p. 3) 12

We see here Coudenhove-Kalergi embracing the concept towards which he had earlier merely gestured, picking up its logical threads and running with them.

His destination was at once more specific and more open-ended than it had been previously. While concluding in general terms that securing German and Italian participation in Europe’s colonisation of Africa was crucial both for African development and for European peace, Coudenhove-Kalergi offered three possibilities by which this might take place. These were: first, the redistribution of colonial mandates (namely, those of Cameroon and Togo, which could be shared between Germany and Italy); second, the outsourcing of colonisation to ‘chartered companies’, including those from non-colony-owning states; and third, ‘the personal and economic equality of all European colonists and pioneers on African soil, regardless of native language and citizenship’ (Ref. Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi10, p. 17). This third solution was clearly Coudenhove-Kalergi’s preference. By declaring that ‘This [third] solution is within the spirit of the General Act of the Berlin Conference and, among all the proposals, most within the spirit of Pan-Europe’ (Ref. Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi10, p. 17), he aligned the PEU and the 1884–85 Berlin Conference on the same historical trajectory. Indeed, the next step suggested by Coudenhove-Kalergi was the convocation of a new ‘Africa Conference’, brokered by Britain, at which these options could be frankly discussed, and a ‘common colonisation programme’ worked out (Ref. Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi10, p. 17).

International Justice

The framing of Europe’s African colonies in terms of justice was most clearly indebted to German colonialist discourse, which asserted that the stripping of Germany’s colonies at Versailles was flagrantly unjust. This decision had been justified not on the basis that Germany was the defeated power, but on the basis that Germany had ‘mismanaged’ her colonies, and was thus unfit to be awarded a Mandate for the control of any African territory. This was most clearly expressed in the Allied and Associated Powers’ 16 June 1919 reply to German protests regarding the prospective Versailles settlement:

Germany’s dereliction in the sphere of colonial civilization has been revealed too completely to admit of the Allied and Associated Powers consenting to make a second experiment and of their assuming the responsibility of again abandoning thirteen or fourteen millions of natives to a fate from which the war has delivered them. 13

The charge of colonial mismanagement was widely seen as a rather flimsy pretext. It was a product of wartime propaganda, an accusation that was assumed rather than proven. The last Governor of German East Africa (and future president of the German Colonial Society), Heinrich Schnee, called it the ‘Colonial Guilt Lie’ (die koloniale Schuldlüge).Reference Schnee 14 Although Schnee’s argument was certainly most popular in Germany, where it served to mend nationalist pride, stoked feelings of victimisation, and rhymed conceptually with the ‘War Guilt Lie’, it also found sympathetic ears elsewhere.

These were certainly arguments to which the PEU was sympathetic. Coudenhove-Kalergi wrote in 1932 that:

Germany has not forgotten that it lost its colonies after a breach of trust by the Allied Powers. That it surrendered in 1918 after the Allies had recognized [Woodrow] Wilson’s Fourteen Points as the basis for peace.Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi 15

He continued by quoting Wilson’s Fifth Point, concerning the ‘free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims’. Coudenhove-Kalergi argued that this Point was breached in Versailles, not by the Allies’ refusal to take into account the wishes of colonial populations, but rather by their refusal to consider Germany’s colonial claims impartially. Specifically, he criticised the Allied use of the pretext of German mistreatment of natives, an accusation that Coudenhove-Kalergi claimed had ‘long been refuted by impeccable testimonies of expert witnesses from Allied and neutral nations’ (Ref. Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi15, p. 9). This state of affairs, he concluded,

embittered the German patriot more than the loss of the colonies itself. So they demand colonies not so much for the colonies’ sake, but as an expression of their equal footing as a great power and in the name of international justice. (Ref. Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi15, p. 9)

Even in 1939, speaking to an English audience on the eve of war, Coudenhove-Kalergi reiterated this point by channelling the voice of the ‘typical’ German:

Germany must be given equality in Europe. If Germany again surrendered and changed her regime, she must know that she would not be treated as she had been at Versailles, where she had not been treated equally or honourably, where she had been not only impoverished but dishonoured.Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi 16

On the issue of whether to accede to the demand for the restitution of Germany’s former colonies, Coudenhove-Kalergi was more equivocal. In the main, he was keen to stress that the solution should not be state-level transferral of territory, but rather some form of supranational cooperation that would diminish the significance of state sovereignty, if not transcend it absolutely. However, in the early 1930s, he did advance the idea of transferring the mandates for Cameroon and Togo to Germany, perhaps to be shared with Italy,Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi 17 reasoning that ‘They would redress a large part of the injustice that Germany suffered in Versailles, and thus be a decisive step towards European reconciliation’ (Ref. Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi16, p. 10). Although he would later row back from this, saying in 1939 that ‘it would be a danger to give [Germany’s former colonies] back to her’ (Ref. Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi16, p. 640), he never shied away from sympathising with the injustice of their seizure.

If this position was designed to win over the German people, among whom colonialist feeling was strong, it was not in line with the official policy of the German government, either in the Weimar or (initially at least) Nazi administrations.Reference Townsend 18 In the first years of Nazi rule, Adolf Hitler’s policy of expansionism was confined to European soil, and rejected the very idea of colonialism. In Mein Kampf, Hitler had dismissed the clamour for the recovery of German colonies as ‘the quite unrealizable, purely fantastic babble of windy parlor patriots and Babbitty coffee-house politicians’,Reference Hitler 19 and criticised the concept of colonialism as being geographically unbalanced:

Many European States today are comparable to pyramids standing on their points. Their European territory is ridiculously small as compared with their burden of colonies. (Ref. Reference Hitler19, p. 180)

Indeed, he wrote in horror of France’s African empire as tending towards a

European-African mulatto State. A mighty self-contained area of settlement from the Rhine to the Congo filled with an inferior race developing out of continual hybridization. (Ref. Reference Hitler19, pp. 937–938)

For the Hitler of Mein Kampf, Eurafrica was not a dream but a nightmare. While the Nazis would (from around 1934) gradually come to embrace the colonial movement – which, after all, shared with Nazi foreign policy the chief goal of revising the Versailles Treaty – it was the Nazi ideology that had to bend to incorporate colonial thinking rather than vice versa.

However, the Pan-European argument also departed from that of German nationalists on a second, deeper level: it was not only about the specific political injustice of the stripping of German colonies under rationalist pretences (itself just one part of Coudenhove-Kalergi’s frustration at what he saw as the betrayal of Wilson’s ideals at Versailles), but rather encompassed the broader historical injustices that meant that countries such as Czechoslovakia and Poland did not have access to colonies. On one level, this was a natural enough argument for Coudenhove-Kalergi to make: as a member of the Austro-Hungarian aristocracy, who after the dismemberment of his homeland had become a citizen of a state (Czechoslovakia) to which he felt no real connection, Coudenhove-Kalergi was more attuned than most to the ‘accident of history’ by which Central Europe had been ‘locked out’ of participation in African colonialism. Moreover, while it was true that these new, ‘artificially’ small states stood to gain by international cooperation through the League of Nations, the Mandate system had fundamentally compromised this vision of internationalism, not only by depriving Germany of its colonies on spurious grounds, but also by handing the mandates for control of these colonies to the colonial powers of Western Europe. The Pan-European solution, which offered Central European states a stake in colonialism, was thus presented as the true expression of the League’s internationalist ideals.

However, there was another, more instrumental reason for Coudenhove-Kalergi to argue for Central European access to African colonies. This was his fear that the ‘historical injustice’ that had deprived them of this access could fuel a future European civil war between a Western-European bloc of colony-owning states, supported by London, and an Eastern bloc of non-colony-owning states, supported by Moscow. By way of analogy, Coudenhove-Kalergi offered a cynical interpretation of the American Civil War, casting the Western group as the slave-owning Confederates, unwilling to give up their economic advantage, and the Eastern group as the Unionists, acting in their own economic interests, although under an idealist banner of freedom (Ref. Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi10, pp. 8–10). In this case, the freedom in question was anti-colonial national liberation, although Coudenhove-Kalergi warned that ‘the slogan of self-determination of coloured peoples would be a welcome pretext to break the colonial monopoly of Western Europe in Africa’ (Ref. Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi10, p. 10). Empathy (let alone agreement) with the anti-colonial cause was thus summarily dismissed; the point instead was that the situation whereby some European states had access to colonies while others did not had created a political tinderbox that threatened Europe itself. Speaking of Djibouti, a French exclave newly surrounded by European powers after the 1935–1936 Italian conquest of Abyssinia, Coudenhove-Kalergi wrote that ‘this African spark could ignite a European fire that would scorch the whole culture of the West.’Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi 20 The way to defuse this situation (and therefore avoid European civil war), he argued, was not to revisit the injustices of the past, but to look to a cooperative future in which such national injustices lost their meaning and melted away. For Coudenhove-Kalergi and the Pan-Europeans, Eurafrica was that future.

Conclusion

The failure of the Pan-European Union to come into being meant that its idea of shared colonialism, in which Central Europeans would be equal partners, remained just an idea. Nevertheless, the popularity of Eurafrica as a discourse, which reached far outside the bounds of the Pan-European Union and persisted well into the post-war period, means that this imaginary demands our attention. I conclude by considering two ways in which the Pan-European arguments for Eurafrica resonated with deeply held understandings of political space.

First, it rested on a peculiarly doubled vision of African space, which flipped in meaning depending on which scale one looked at. At the state scale, African space was seen as ‘closed’ (i.e. fully carved up by European states), and therefore threatening, since disputes over African territory could easily conduct violence back into Europe, while the imbalance of colony ownership stoked European tension. This connection between the ‘closure’ of political space and a fragile or precarious political situation was widely felt, and perhaps best expressed by Halford Mackinder: ‘Do you realise that we have now made the circuit of the world, and that every system is now a closed system, and that you can now alter nothing without altering the balance of everything…?’Reference Mackinder 21

In this imaginary, Central Europe’s apparent exclusion from this closed colonial system was not only unjust but potentially dangerous, as it risked igniting conflict within Europe itself. However, when seen at the supranational (or ‘Pan-European’) scale, African space was marked not by its fullness, but by its emptiness, wherein lay its great promise. At this scale, Africa was not a ‘spark’, but a valve through which spatially-rendered ‘pressures’ (political, economic or demographic) could be released. Its emptiness was an invitation: it was as if the old Crusading justification of extra-European terra nullius could be resurrected at the Pan-European level, re-imagined as Pan-European terra communis.

Second, Africa was seen as a crucible in which a united Europe, or at the very least European solidarity, could be forged, and the violence it took to forge it overlooked. If the colonies had long been sites of experimentation in new technologies of governance by imperial powers, here Africa was to be the site of experimentation for a whole new scale of governance. In this, the 1885 General Act of the Berlin Conference loomed large, both as a precedent for this sort of ambition, and as a failure that had to be overcome. Specifically, the innovatively internationalist (in theory) Congo Free State, created in Berlin, had earned infamy as a site of notorious and appalling European misrule, the experiment finally ending with Belgian annexation in 1908.Reference Fox Bourne 22 The challenge was to prove that this failure was not the result of its internationalist ideals, but of the failure to fully apply those ideals, and that a purer iteration of European co-operation in Africa would prove the efficacy of supranational governance, such that it could be introduced in Europe itself. Talk of the potential of such plans to ‘widen the horizon of Europe’Reference Coudenhove-Kalergi 23 was indicative of the way in which Africa was represented as Europe’s mission, quest or destiny, thus serving to reflect the focus squarely back on Europe (and entirely occlude colonial violence in Africa). And if Europe was finding itself in Africa, then Central European participation in colonialism became about much more than ‘fairness’ in profiting from African resources, more even than the prestige of owning colonies: it was about sharing in the European project, a project that was being produced in Africa for consumption back in Europe.

Benjamin J. Thorpe is a PhD candidate within the School of Geography at the University of Nottingham (2013–2018). His research looks at the shaping of a European political imagination during the interwar years, with particular reference to the contributions of the Pan-European Union. In the course of his doctoral research, he has been a Visiting Student at both the European University Institute, Department of History and Civilisation, in Florence (September to October 2014), and the Higher School of Economics in Moscow (October to November 2015).