Introduction

Every year, discoveries of ancient Egyptian monuments and artworks are widely disseminated across the media, providing further evidence for the cultural and spiritual richness of ancient Egypt. ‘Caches’—deposits of intentionally hidden artefacts—figure among discoveries that particularly stimulate the collective imagination and the interest of researchers. The practice of caching is well evidenced in Egypt and the Near East, dating to the Predynastic and even the Neolithic periods (e.g. Williams Reference Williams1982; Freikman & Garfinkel Reference Freikman and Garfinkel2009). Many types of cache have so far been discovered, from caches of mummies and sarcophagi, to statues, papyri and jewels, to more modest, sometimes mixed, deposits of coins, ostraca and embalming instruments (e.g. Maspero Reference Maspero1881; Quibell Reference Quibell1898: 3; Legrain Reference Legrain1906; Kamel Reference Kamel1968; Hegazy & Van Siclen Reference Hegazy and Van Siclen1989; Reddé et al. Reference Reddé, Gout and Lecler1992; Eaton-Krauss Reference Eaton-Krauss2008; Wahby Taher Reference Wahby Taher2011; Faucher et al . Reference Faucher, Meadows and Lorber2017). These numerous deposits do not all fulfil the same function(s)—many functional categories are found in the literature. These include funerary, ‘cultic’ or votive caches, caches for storage, preservation, execration or consecration; and also foundation deposits and treasures—the definition and identification of which are not always clearly established.

Although they represent some of the most spectacular discoveries, caches of sacred objects are particularly poorly documented. In Egypt and neighbouring regions, their role was to preserve, inside the temple precinct, and thus concealed from impious eyes, divine statues, ex-votos, cultic instruments and furniture consecrated in the sanctuaries. Religious items, well known from inventories made by the clergy throughout Egyptian history (Cauville Reference Cauville1987), retained their sacred character and power and required protection from any exterior intrusion. Upon going out of use, these artefacts were gathered in an enclosed space by the temple priests, being the only individuals authorised to manage this type of religious material.

Caches of sacred objects are divided into three main groups, differentiated according to context: pits, also known as favissae (e.g. Legrain Reference Legrain1905; Saghir Reference Saghir1992; Coulon Reference Coulon2016a); caches in foundation trenches (e.g. Robichon et al. Reference Robichon, Barguet and Leclant1954: 34; Charloux Reference Charloux2012); and so-called ‘built’ caches, such as a niche, a reinforcement in the masonry of a building, or a specific built structure, for example, in a well or cistern (e.g. Quibell & Green Reference Quibell and Green1902: 27; Thiers Reference Thiers2014). The caches of religious artefacts discussed here represent deposits in secondary contexts only. Thus, furnishings and statues in primary contexts (e.g. in official religious spaces, in a domestic sanctuary or in a tomb) are excluded from this category.

Caches of religious artefacts are distinguishable from other categories of caches, in particular ‘treasure’, which would be identified here as a ‘safety deposit’ (Vernus Reference Vernus1989). This comprises a group of objects whose value is more economic than cultic (e.g. ingots, coins, jewels) and which were buried with the intention of being retrieved at a later date. ‘Foundation deposits’ are also composed of sacred artefacts placed in pits, but in a primary context: the artefacts are often quite small and of standardised composition, and were intended for the commemoration and protection of the buildings under which they were buried (Weinstein Reference Weinstein1973; Schmitt Reference Schmitt, Kousoulis and Lazaridis2015).

Caches of sacred objects were unlikely to have been temple ‘dustbins’ with no specific purpose; the burial of sacred artefacts was probably accompanied by ceremonies, the exact nature of which is unknown due to the absence of descriptive historical sources. Contrary to many other events in the religious life of the temple, the rites and practices surrounding these caches do not seem to have been the subject of textual or iconographic descriptions (but see Coulon Reference Coulon2016b). The archaeological study of these particular assemblages should, therefore, illuminate the actions and intentions of those who buried the objects, and the associated ceremonial rites (Jambon Reference Jambon and Coulon2016). Unfortunately, due to a lack of published field data, it is as difficult to characterise and classify these deposits typologically as it is to date them. Excavations around the temple of Ptah in Karnak, Egypt, have recently provided the fortuitous opportunity for a detailed study of an in situ favissa cache. These excavations are part of the permanent CFEETK research project (Ministry of Antiquities, Egypt; USR3172 of the CNRS, France), and the discovery has led to the formulation of new hypotheses concerning the raison d’être of these rich assemblages.

Area and method of study

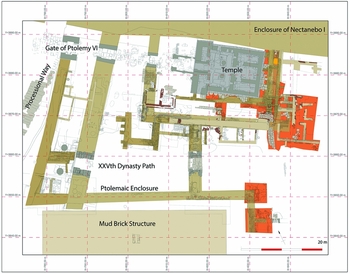

The temple of Ptah is located at the northern edge of the domain of Amun-Re in Karnak (Figure 1). Erected during the New Kingdom by Thutmosis III (Eighteenth Dynasty), the present monument was built over an older structure (Thiers Reference Thiers and Beinlich2013; Charloux & Thiers Reference Charloux and Thiers2017). The temple was modified during the course of the New Kingdom, before more extensive refurbishment changed its layout during the first millennium BC (Biston-Moulin & Thiers Reference Biston-Moulin and Thiers2016) (Figures 2 & 3). The space inside the temple precinct was finally occupied by civilian installations in the Ptolemaic and Roman-Byzantine periods (David Reference David2013; Durand Reference Durand2015).

Figure 1. Plan of the temple of Amun in Karnak and the area under study (© CFEETK-CNRS-MoA: G. Charloux, K. Guadagnini).

Figure 2. The sector of the temple of Ptah showing the areas excavated in 2015 (© CFEETK-CNRS-MoA: M. Abady Mahmoud, G. Charloux, K. Guadagnini, P. Zignani et al.).

Figure 3. Overview of the temple of Ptah in Karnak (© CFEETK-CNRS-MoA: J.-Fr. Gout).

The favissa was discovered in December 2014, less than 3m behind the edifice of Thutmosis III, 1.75m south of the mudbrick enclosure of Nectanebo I (Figure 4). It quickly became clear that a series of earlier reconstructions had disturbed the area. Excavation revealed that the favissa had been intentionally dug between two long brick walls running north–south. They were probably placed here as a preparatory structure for the laying of paving that no longer exists. The favissa and the brick wall to the west would, therefore, have been covered by paving slabs.

Figure 4. The favissa in its archaeological context, at the back of the temple of Ptah (© CFEETK-CNRS-MoA: G. Charloux, K. Guadagnini).

The oval-shaped pit measured 1.46m north–south and 1.05m east–west. Its vertical sides were exposed to a depth of almost 1m (Figure 5). The upper part was partially restituted by the CFEETK archaeologists, notably on its south-west side, which was destroyed due to recent disturbances. Three distinct layers of clayey and dense silt filled the favissa. The bottom of the pit, upon which was placed the statue of Ptah, comprised a layer of yellow desert sand from a lower level (i.e. the pit cut into previous archaeological contexts). Several fragments of inlay were found by systematic sieving with a 7mm mesh. Photogrammetry at each stage of the excavation was used to create 3D reconstructions of the exact in situ artefact positions. Field photographs were also assembled and adjusted using Photoscan software, with an accuracy of ≤10mm using topographic points (three to five points per stage) taken by a robotic Leica TPS1200+ total station. A 3D model of the favissa was then created with 3DSMax software using field data and the objects themselves (recreated by this photogrammetric method), following restoration. This systematic process was necessary, as it was impossible to leave the artefacts in situ once they had been exposed; the local authorities required them to be moved into secure storage at the end of each day. Immediate conservation was provided by a team of CFEETK conservators (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Plan of the favissa and reconstructed image of the restored objects, after 3D modelling (© CFEETK-CNRS-MoA: G. Charloux, K. Guadagnini).

Figure 6. Conservation of an Osiris statuette (© CFEETK-CNRS-MoA: J. Maucor).

The objects and stages of deposition

The favissa contained 38 objects made of limestone (some gilded), greywacke, probably wood (but completely lost), copper alloy, faience and Egyptian frit (Figure 7), as follows:

-

• Fourteen statuettes and figurines of Osiris;

-

• Eleven fragments of inlay (iris, cornea, false beard, cap, strand of hair, inlay plaque) from statues;

-

• Three baboon statuettes (representing the god Thoth);

-

• Two statuettes of the goddess Mut (one with hieroglyphic inscriptions);

-

• Two unidentified statuette bases;

-

• One head and one fragmentary statuette of a cat (Bastet);

-

• One small fragmentary faience stele recording the name of the god Ptah;

-

• One head of a statuette of a man in gilded limestone;

-

• One lower part of a statue of the seated god Ptah, sawn and repaired;

-

• One sphinx;

-

• One unidentified metal piece.

Figure 7. Main artefacts discovered: top left) male head; top right) lower part of the limestone statue of the god Ptah; bottom left) limestone sphinx; bottom right) small statue of Osiris (© CFEETK-CNRS-MoA: J. Maucor).

With one exception, all of the artefacts were fragmentary, having been damaged in antiquity.

Four stages of the burial sequence were identified:

-

1. First, the digging of the favissa had cut through three older levels, including an earlier pit. The available evidence suggests that the size of the original pit had been constrained by the adjacent mudbrick walls.

-

2. Next, the artefacts were placed in the bottom of the favissa. The first artefact deposited was the lower part of the limestone statue of the seated god Ptah, lying on its right side. Given the depth of the pit and the weight of the statue, there is no doubt that this statue was positioned manually by at least two or three individuals. The statue was intentionally placed in the south-east portion of the pit to leave space for a wooden effigy of the god Osiris (Figure 8), of which only the decorated surface coating and elements of the appliquéd metal (beard and two feathers of the Atef Crown) have survived. Several concentrations of painted and gilded coating suggest the presence of other organic statues or statuettes, long since disappeared. The other artefacts were then distributed evenly around and above the statue of Ptah during backfilling of the favissa (Figure 9).

-

3. In the third stage, over 200mm of backfill was deposited before the small limestone sphinx statue was placed in the north-east area of the pit.

-

4. Finally, there were two more depositions of soil before a small male head was placed in the upper layer. The cut edges of the pit at the level of this head were not observed in the field, due to subsequent disturbance. The nature and position of the head in the upper layer of the favissa, between the first courses of the brick wall, however, leave little doubt as to its association with the deposit of statues below.

Figure 8. Excavating the remains of the covering of a wooden statuette of Osiris (© CFEETK-CNRS-MoA: M. Abady Mahmoud).

Figure 9. Reconstructed cross-section of the favissa looking south (after 3D modelling of the restored objects) (© CFEETK-CNRS-MoA: K. Guadagnini).

Despite the layered character of the deposit, a detailed inspection of the stratigraphy does not indicate any later disturbance following the burial. As with numerous other favissae, it clearly highlights the ephemeral character of the act of burying such objects (e.g. Quibell & Green Reference Quibell and Green1902: 34–35; Legrain Reference Legrain1905: 66).

Discussion

Dating

Favissae are generally difficult to date accurately: the items in the pit provide, at best, a terminus post quem for its digging, whereas the archaeological levels sealing it, when extant, provide a terminus ante quem. The artefacts from the Ptah favissa had been used for a long time before being deposited. The fragmentary statue of Ptah dates back to the New Kingdom, probably to the pre-Amarna period, as evidenced by other restored examples (Barbotin Reference Barbotin, Valbelle and Yoyotte2011). A Third Intermediate Period/Late Period date (Twenty-fifth to Thirtieth Dynasties) is suggested for the statuettes and figurines, mainly through stylistic comparisons of the two greywacke statuettes of Osiris and the inscriptions on a statuette of Mut. The small statue of the sphinx, however, tells a slightly different story; its general appearance, the shape of the face and eyes and the modelling of the muscles support a late Ptolemaic date, whereas the gilded male head may date the artefact to the early Ptolemaic period. This supports the conclusions of the pottery analysis, which dates a few sherds to early Ptolemaic times among a vast majority of Late Period wares. This confirms the stratigraphic analysis: the paving and the southern door of the temple façade were most probably installed in the Ptolemaic period. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that the artefacts were removed from the sanctuary and then buried by its priests in the second half of the Ptolemaic period, around the second century to the middle of the first century BC.

The statue of the god Ptah and its physical and symbolic protection

The central positioning of the fragmentary statue of Ptah on the base of the favissa indicates that this was the main object in the deposit. Moreover, being larger than the other figures (see Traunecker Reference Traunecker2004: 52), it represents the only cultic statue in the favissa (with the possible exception of the faience beard from another large statue). The statue of Ptah was also facing west, meaning that it was positioned on the central axis of the north chapel of the sanctuary, where, in antiquity, the cultic statue of the god Ptah was placed. Other artefacts support a link between the favissa and the neighbouring temple: the presence of four caps in blue faience—attributes of Ptah—and a small faience stele recording the name and a representation of Ptah. Taking these elements into account, it is reasonable to suggest that the statue of the god was originally housed in the neighbouring sanctuary.

The intentional layering of the artefacts and the care taken over their relative distribution must have been the product of well-established rituals, a few characteristics of which can be discerned:

First, there is the particular care accorded to the protection of the central effigy. Deposited on a layer of yellow sand, the divine statue was ‘wrapped’ in a protective ‘cloak’ of small, damaged votive images, which surround it on all sides and above.

The middle stage of the favissa was placed under the protection of the sphinx, a well-known mythical guardian, which was facing eastwards towards the sunrise. The presence of a protective guardian in the form of a sphinx, or sometimes a lion or jackal (Anubis), occurs sufficiently often to consider it a common element in statue caches (e.g. at Saqqara North (Emery Reference Emery1967: pl. XXI, no. 2) or at Karnak North (Robichon et al. Reference Robichon, Barguet and Leclant1954: 34, fig. 65); see also Coulon Reference Coulon2016b: 33–34, fig. 12). This hypothesis is substantiated by the high proportion of these effigies in votive contexts (Pinch & Waraksa Reference Pinch, Waraksa, Wendrich, Dieleman, Frood and Baines2009: 5). If it is indeed associated with the favissa, the male head perhaps represents an additional stage of protection. Finally, paving most probably sealed the items in the favissa, as seen in other caches of this type (see Jambon Reference Jambon and Coulon2016: 157). Another important observation addresses the ‘mutilation’ of the artefacts in the favissa—or at least the fact that they were invariably fragmentary or damaged. This is a recurring phenomenon in this type of deposit, as recorded by virtually all excavators (e.g. Chassinat Reference Chassinat1921: 56–57; Mond & Myers Reference Mond and Myers1940: 49). It has been suggested that these statue caches were made following catastrophic events (e.g. fire or earthquake), invasion or conflict, religious change, cleaning of a cluttered sanctuary, or simply following the deterioration of the cultic objects (Bonnet & Valbelle Reference Bonnet and Valbelle2005: 174). Distinguishing between various events and phenomena such as these, using archaeological evidence, however, remains difficult. It should be remembered that the criteria determining when statues went out of use in ancient Egypt are unknown. Although it is usually difficult to identify events that led to breakages, it is nonetheless obvious that some breakages occurred well before the artefact was deposited in a cache; this is the case, for example, with one statuette of Mut in the Ptah favissa cache (Figure 10), and for statues of Amun in the favissa of Luxor (Saghir Reference Saghir1992: 16). The latter shows evidence of ancient restoration, recognisable as cracks filled with mortar. Equally, it is known through numerous textual attestations that the ‘political’ destruction of statues was clearly supported in Egypt (Boraik Reference Boraik2007), the Levant and Mesopotamia (Ben-Tor Reference Ben-Tor, Gitin, Wright and Dessel2006). It can also be assumed that some damage resulted from the act of deposition, although it would be difficult to infer any ritual motivation for such damage. This may have been the case for the small sphinx statue in the favissa—its broken front left paw was placed against the front part of its body; the object may have been broken during its deposition. Equally, there are quite specific cases of the crumbling of statues that are difficult to ascribe to political or accidental events (e.g. Robichon et al. Reference Robichon, Barguet and Leclant1954: 47).

Figure 10. Statuette of Mut following excavation from the favissa (© CFEETK-CNRS-MoA: J. Maucor).

Damage to the physical integrity of statues can be quite remarkable. At Deir el-Bahari, for example, the figures of Mentuhotep II and Amenhotep I were systematically decapitated, and the heads and bodies buried in pits far away from each other (Arnold et al. Reference Arnold, Winlock, Burton, Hauser and Peek1979; Szafranski Reference Szafranski1985: 259–62). In the 1930s, Mond and Myers (Reference Mond and Myers1940: 16; pl. XI, fig. 1 and pl. L., fig. 2) discovered two similar cases at Armant. Here, the heads and bodies of two different colossus statues were combined to create a complete statue. These unusual examples illustrate the intentional regrouping of separate statue parts.

These lines of evidence suggest that the systematic occurrence of artefact breakage is more important than the actual reasons behind such damage. Whatever their origins, the breakages occurred before, or sometimes during, deposition. It can be deduced that the statues must have been, in some way, at the end of their ‘lives’ or of their use. This ‘death’ of a statue was a crucial influence in its deposition; were the breakages intended to ‘channel’ the energy of the statues (Bianchi Reference Bianchi2014: 22), or to ‘deactivate’ their power? Or did the simple state of being broken confer eligibility for inclusion in the ritual? Current evidence is clearly insufficient to explain the raison d’être of the deposits, or to determine the intentions of the depositors.

A simulacrum of a tomb of Osiris

It is well known that, in ancient Egypt, the god's statue had its own ‘existence’: made for the temple by craftsmen who knew about ‘secret things’, it was ‘born’ in the ‘Mansion-of-Gold’ before being invested with the soul of the divinity during the ceremony of the ‘opening of the mouth’. During its ‘life’, the statue was cared for according to the ‘Daily Ritual’: it was washed, coated, perfumed, dressed, fed, and the like. Various practices were added to these daily rituals, such as the regeneration of divine power by the rays of the sun. As a receptacle for the divinity, the statue also participated in annual liturgical processions and religious celebrations of the city. What happened to the divine image at the end of its use-life is more difficult to understand. It has been suggested that the oldest effigies from the temple at Dendera were deposited, perhaps even ‘immured’, in the crypts of the temple itself (Cauville Reference Cauville1987: 112; Cauville et al. Reference Cauville, Lecler, Lenthéric, Ménassa, Deleuze and Laferrière1990: 16). A passage in the Temple Manual explains the role of the crypt: “When there is trouble on the earth, then we put the cultic images of all the gods there to distance them from it” (Quack Reference Quack2004: 14). Through this role of protection and concealment, it seems that crypts and caches of objects had certain functions in common (see Vernus Reference Vernus and Coulon2016). This dichotomy may, however, result from two successive stages in the ‘life’ of the divine statue or religious objects. Firstly, the crypts, sometimes considered as simulacra of the tomb of Osiris (Traunecker Reference Traunecker2004), preserved figures in a primary context, where they continued to play a role in the cultic function of the temple. Secondly, the caches gathered together statues, fragments of statues or objects that were no longer in use in the temple and which were therefore deposited in a permanently sealed secondary context.

At the end of its ‘life’, the statue was taken out of the sanctuary and ritually buried. The inhumation was carried out by the temple priests (perhaps the “chief of rituals” or the “purifier of the god”; Quack Reference Quack and Coulon2010: 25) as part of an act intended to hide, protect and organise the deposit. The favissa constituted the grave of the statue, both literally and figuratively.

Assimilating the deceased with Osiris, god of the dead and lord of the hereafter, was a normal practice in ancient Egypt. We suggest that this assimilation also included the statue of the divine cult (on this subject, see Kristensen Reference Kristensen2009), which, at the end of its life, was buried in a cache, a simulacrum of an Osirian tomb. In a recent study on the Cachette de Karnak, Jambon (Reference Jambon and Coulon2016) envisaged a funerary role for the favissae of the Luxor region, with ceremonies carried out during the burial of the statues. Equally, Szafranski (Reference Szafranski1985: 261–63) suspected a similar destiny for a statue of Amenhotep I at Deir-el-Bahari. It is, therefore, clearly no coincidence that the statue of the god Ptah was buried, fragmented and out of use, at the bottom of a pit at the back of the temple of Ptah in Karnak. Here, Ptah was assimilated with Osiris in a regeneration phase. His tomb was territory forbidden to everyone, its opening constituting a “violation of an interdiction” (Vernus Reference Vernus1989: 38). The omnipresence of Osiris in this type of context provided an adequate accompaniment to the figure of the god Ptah into the hereafter, thereby predicting the proper regrouping of Ptah's scattered limbs and his future rebirth (Traunecker Reference Traunecker2004: 52).

By far the largest category of images of a god in the Ptah favissa comprised the 14 figurines of Osiris. The most remarkable was a wooden figure placed at the bottom of the pit, which has now disintegrated despite the efforts of the conservators. In fact, small bronze Osiris figures, in particular, are consistently found in Egyptian caches. A simple funerary use, however, once the statuettes had been broken, cannot be discounted. The funerary custom of accompanying the deceased with statuettes was common in ancient Egypt.

Mythical guardians (e.g. sphinx) were added in association with these Osirian effigies, as discussed above. The caches of religious artefacts—especially the more complex caches—show, therefore, several characteristics of the Osirian burial.

The practice of burying statues in favissae cannot be dissociated from other types of pit inhumations of mummies or Osirian figurines. These include, for example, the famous Osirian ‘corn-mummies’ (Coulon Reference Coulon, Estienne, Huet, Lissarague and Prost2014). As devotion to Osiris took multiple forms (Coulon Reference Coulon and Coulon2010: 12), the Osirian simulacra probably showed great variation in type. The evidence discussed above suggests that the burial of sacred artefacts no longer in use, arranged around a divine statue, formed part of an extensive pattern of coherent and varied Osirian burial practices. The favissa of the temple of Ptah constitutes an exceptional example of the grave of a statue of a god situated close to its main place of worship.

Acknowledgements

This project is supported by LabEx Archimede from programme ‘Investissement d'Avenir’ ANR-11-LABX-0032-01. We particularly wish to thank the Ministry of Antiquities of Egypt (MoA), the CNRS and the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs for their financial, technical and scientific support. A monograph in preparation will soon provide all of the documentation and commentaries to the preliminary results presented in this article.