1. Background

The increasing involvement of the private sector in health care has been discussed extensively in most European countries and remains a hot topic nowadays (Mackintosh et al., Reference Mackintosh, Channon, Karan, Selvaraj, Cavagnero and Zhao2016; McPake and Hanson, Reference McPake and Hanson2016; Montagu and Goodman, Reference Montagu and Goodman2016; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Ensor and Waters2016). As a result of privatisation, the rapidly growing involvement of the private sector in health care is gradually challenging the role of the state, implying an urgent need to re-balance public and private sectors in delivering health services (Marshall and Bindman, Reference Marshall and Bindman2016). Scholarly literature has not presented a single attitude towards private sector involvement in services like health care (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Roehrich and Wright2013; Mills, Reference Mills2014; Roehrich et al., Reference Roehrich, Lewis and George2014; Torchia et al., Reference Torchia, Calabro and Morner2015; André and Batifoulier, Reference André and Batifoulier2016). Similarly, this paper will not explore whether gradually relying on the private sector is an effective approach for expanding the accessibility of better quality health care or not. It aims rather to address special concerns about how to measure the private sector properly (especially using legal measures) in order to secure an efficient and sustainable way of delivering health services and, more importantly, enabling people to optimally benefit from the increasing involvement of the private sector in health care.

In general, existing literature tends to be context-specific (Blumenthal and Hsiao, Reference Blumenthal and Hsiao2005, Reference Blumenthal and Hsiao2015; Maarse, Reference Maarse2006; Toebes, Reference Toebes2006; Yip and Hsiao, Reference Yip and Hsiao2014; Larsen, Reference Larsen2015). Thus, this paper takes the Chinese health care system as its basic context, taking into account that the private sector has been offered a great opportunity to grow in China and is having a significant impact on the Chinese health care system. Although a great deal of literature is available on private sector involvement in health care in China (Blumenthal and Hsiao, Reference Blumenthal and Hsiao2005, Reference Blumenthal and Hsiao2015; Yu, Reference Yu, Lin and Song2007; Ramesh and Wu, Reference Ramesh and Wu2009; Liu and Darimont, Reference Liu and Darimont2013; Yip and Hsiao, Reference Yip and Hsiao2014; Tu et al., Reference Tu, Wang and Wu2015), discussions rarely include a human rights perspective. This paper therefore attempts to fill this gap by approaching the question from a human rights perspective. In order to develop a better understanding of private sector involvement in health care in China, the paper takes private medical institutions (PMIs) as an example. By studying the case of PMIs, the paper attempts to find the answer to the following questions: to what extent does privatisation have an impact on health care in China and how does the state fulfil its role in measuring the gradually increasing private sector properly (especially using legal–regulatory measures) from a human rights perspective in order to develop a more efficient and sustainable health care system in China?

2. Context: PMIs in China

The very first PMI was set up in 1984, encouraged by Chinese economic innovation (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Liu and Meng1994), the decentralised reforms of China's administrative system and the 1982 edition of the Chinese Constitution. Thereafter, the State Council and its General Office released a series of administrative regulations and interpretations to support and promote the development of PMIs. Nevertheless, the development of PMIs was slower than expected due to the lack of explicit internal classification at that time. Recognising this impediment, in 2000, the State Council and the Ministry of Health issued guiding opinions and detailed implementations on differentiating for-profit PMIs from non-for-profit ones. Since then, for-profit and non-for-profit PMIs have both had many opportunities to improve. Besides these supportive polices, public medical institutions tend to ease their financial burden, resulting from reduced governmental subsidies, by ‘contracting out’ certain parts of their health care services to PMIs. ‘Contracting out’ activities effectively contributed to the rapid development of PMIs in China. In the 2009 health care reform, the Chinese government affirmed the supplementary role of PMIs in its health care system. From then onwards, the Chinese government released a series of provisions to support and encourage the development of PMIs, such as the recently released Guiding Principle on the Establishment of Medical Institutions in China (2016–2020).

The rapidly growing PMIs do expand health care accessibility and improve the quality of health services (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Brugha, Hanson and McPake2002; Albreht, Reference Albreht2009). However, they also inevitably result in certain risks, such as the violation of human rights and the deterioration of public health delivery (Bloche, Reference Bloche, Feyter and Isa2005; Toebes, Reference Toebes2006; Horton and Clark, Reference Horton and Clark2016). However, as Bloche (Reference Bloche, Feyter and Isa2005) argued, these risks can be minimised if the health care system is facilitated with effective regulatory strategies, especially legal–regulatory measures.

3. Structure: map the discussion

The paper is structured as follows: the paper describes the background of this study by a selective literature review and a brief narrative on the context. In order to avoid any ambiguity, the paper includes a conceptual clarification of various key terms, such as ‘privatisation’, in the section ‘Conceptual clarification and theoretical background’. Thereafter, it briefly explores the reasons and risks (i.e. advantages and disadvantages) of involving the private sector in health care and emphasises the importance of how the state fulfils its role in measuring the gradually evolving private sector. The paper then describes in detail the relevant International human rights law, thereby observing that the state is required to assume an active regulatory role rather than play a ‘provider’ role in controlling and supporting the development of the private sector in health care. Thus, the major concern of the following discussion shifts to address the regulatory role of the state in dealing with the rapidly growing private sector in health care. In the ‘Method’ part, the searching criteria and assessing tools (i.e. Figure 1 ‘The diagnostic process’) are introduced. These originated from the Preferred Reporting Items for System reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines and the ‘control knob’ framework developed by Roberts et al. The ‘Results and discussion’ section evaluates current legal–regulatory strategies (including effective legal rules and related regulatory bodies) concerning PMIs in China and provides corresponding recommendations for improving these strategies. Finally, the paper reaffirms the need to strengthen and improve the regulatory role of the state in order to guide and support the rapidly growing private sector in health care in China.

Figure 1. The diagnostic process.

4. Conceptual clarification and theoretical background

4.1 Privatisation in health care

According to the World Health Organization definition, privatisation involves the change of ‘ownership and government functions from public to private bodies’. Potential benefits of privatisation in health care include increasing efficiency (Bloche, Reference Bloche, Feyter and Isa2005; Kozinski and Bentz, Reference Kozinski and Bentz2013), promoting patient rights (e.g. diversifying health services, expanding individual choices and improving the quality of health care) (Albreht, Reference Albreht2009) and covering remote areas which are beyond the attention of public sector (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Brugha, Hanson and McPake2002). Inevitably, there are also certain concerns, such as the risk of human rights violation and deteriorating public health delivery due to the profit-seeking behaviour of private actors (Bloche, Reference Bloche, Feyter and Isa2005; Toebes, Reference Toebes2006; Horton and Clark, Reference Horton and Clark2016).

In general, there are two prominent types of privatisation: full privatisation (i.e. the transfer of ownership from public sector to private sector) and ‘contracting out’ (or, ‘outsourcing’) (Feyter and Isa, Reference Feyter, Isa, Feyter and Isa2005; Toebes, Reference Toebes2006). In contrast to full privatisation, ‘contracting out’ (or, ‘outsourcing’) in health care refers to the situation whereby public sector merely delegates responsibility for providing health care and the corresponding risk management to the private sector on the basis of contracts but retains ownership (Graham, Reference Graham, Feyter and Isa2005). These two types of privatisation cover a wide range of models regarding public–private partnerships in health care (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Roehrich and Wright2013). Research shows that cultivating a healthy public–private partnership is a plausible way to manage the gradually evolving private sector in health care and will be better able to secure the accessibility of good quality health services (Roehrich et al., Reference Roehrich, Barlow, White and Das2013, Reference Roehrich, Lewis and George2014). In this regard, the question is how to optimally balance public and private sectors in health care from a human rights perspective. I intend to explore the answer to this question with a special focus on the role of the state.

4.2 International human rights law and state accountability

International human rights law requires state members to take state accountability to protect and promote the right to health. However, the gradually increasing reliance on the private sector is easily misunderstood as a process of reducing state accountability in health care. Although increasing privatisation in health care accelerates the transfer of ‘ownership and government functions’ from public medical institutions to the private sector, thus promoting the development of private sector, the state is still responsible for ensuring that health care delivery remains the answer to the basic principles of human rights.

General Comment No. 3 of Article 2 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) broadly stipulates that the state should have a minimum core obligation in ensuring the satisfaction of the rights recognised by ICESCR, which includes guaranteeing primary health care services. Specifically, Article 12 of ICESCR recognises ‘the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health’ and state accountability in protecting and promoting the above right. This highly abstracted stipulation is very difficult to enforce. In response, the UN Commission on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights issued General Comment No. 14 to provide a further interpretation. General Comment No. 14 requires the state members of ICESCR to protect and promote the right to health according to the standards of ‘Availability, Accessibility (Non-discrimination, Physically accessibility, Affordability, Information accessibility), Acceptability, and Quality (AAAQ)’. Furthermore, in line with General Comment No. 3 and General Comment No. 14, the scope and extent of implementation may differ and be achieved progressively in accordance with the diverse conditions of the member states, but actions towards ‘AAAQ’ must be taken ‘within a reasonably short time after the Covenant's entry into force for the States concerned’.

There are other international human rights treaties and provisions which generate an indirect but profound influence on state accountability in regulating the private sector in health care services. For instance, General Comment No. 31 of Article 2 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) specifies the general legal obligations of states in regulating private entities. General Comment No. 15 of Article 11 and Article 12 of ICESCR and General Comment No. 22 of Article 12 of ICESCR delineate state accountability in monitoring and controlling the behaviour of the private sector in protecting and promoting the right to water. General Comment No. 16 of Article 17 of ICCPR stipulates the importance of the private sector such as databanks in protecting the right to privacy. With regard to vulnerable groups, such as women and children, there are articles (e.g. General Comment No. 15 and General Comment No. 24) which stipulate that state accountability in protecting and promoting the right to health of women and children cannot be absolved by delegating medical services to the private sector.

4.3 ICESCR General Comment No. 14 and the regulatory role of the state

Specifically, regulating the private sector mainly relies on ICESCR General Comment No. 14. According to General Comment No. 14, states should take their obligation to protect the right to health from third parties' infringements. In other words, it requires states to adopt their regulatory role to ensure the fulfilment of the following guidelines before allowing the expansion of privatisation in their health care systems:

‘(1) Ensuring that the privatisation of the health sector does not constitute a threat to the availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality of health facilities, goods and services; (2) ensuring that harmful social or traditional practices do not interfere with access to pre-natal and post-natal care and family planning; (3) ensuring that third parties do not limit people's access to health-related information and services; (4) to ensure equal access to health care and health-related services provided by third parties; (5) to control the marketing of medical equipment and medicines by third parties; (6) to ensure that medical practitioners and other health professionals meet appropriate standards of education, skill and ethical codes of conduct; (7) to prevent third parties from coercing women to undergo traditional practices; (8) to protect all vulnerable or marginalised groups of society, in particular women, children, adolescents and older persons, in the light of gender-based expressions of violence’ (ICESCR General Comment No. 14, para. 35).

Overall, the increasing involvement of the private sector does not change ‘the role of the state as the ultimate guarantor of the realisation of health rights obligations’ (Minow, Reference Minow2003). In contrast, the state should assume an active regulatory role in controlling, supporting and encouraging the private sector towards achieving national health goals (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Brugha, Hanson and McPake2002).

5. Methods

This section explains the strategies and criteria in searching and selecting existing literature and related legislation in China. Furthermore, tools for assessing legal–regulatory strategies are also briefly introduced.

5.1 Selection strategy and search criteria

This research follows the PRISMA guidelines.Footnote 1 To capture peer-reviewed literature, I searched for information through electronic databases, including PubMed and Google Scholar, using the timeline between 1 January 1990 and 1 January 2018. Besides peer-reviewed literature, classic monographs were also included for the sake of analysis, such as Getting Health Reform Right: A Guide to Improve Performance and Equity which was edited by Roberts et al., The Privatization of Health Care Reform: Legal and Regulatory Perspectives which was edited by Bloche, and Privatization and Human Rights: In the Age of Globalization which was edited by Feyter and Isa.

Details of the literature search are given below with an example from PubMed: I used five key terms (i.e. ‘private medical institutions’, ‘privatisation’, ‘health care’, ‘China’ and ‘regulation’) to search for the information through the PubMed advanced search builder.

The results showed that there were only 42 studies in PubMed that met the selecting criteria. The same strategy was used to search for studies in Google Scholar. The results were fairly similar to those in PubMed. Given the fact that few studies are available on the regulation of PMIs in China, I attempted to fill that gap by discussing the development of PMIs with a special focus on legal–regulatory strategies.

With regard to the legislation search, I used a law database, PKULaw, to collect China's laws and regulations relating to PMIs. Presented in Figure 2, many legal rules, including laws, administrative regulations, the interpretations of administrative regulations, the regulatory documents of the State Council and department rules concerning PMIs have been released since 2000.

Figure 2. Legal rules concerning PMIs at the state level.

Source: Pkulaw, http://en.pkulaw.cn/. Accessed 12 February 2018.

*Notes: ‘The Interpretations of Administrative Regulations’ and ‘the Regulatory Documents of the State Council’ are separated from ‘Administrative Regulations’ because the Legislation Law of the People's Republic of China (2015 Amendment) does not have an explicit stipulation on the authority of these legal rules.

In terms of the assessment strategy, I used the ‘regulation control knob’ as the basis for my diagnostic process (Figure 1) to assess current legal–regulatory strategies (including legal rules and regulatory agencies) of PMIs in China. The benchmarks used for the assessment were originated by the ‘control knob’ framework in Roberts et al.'s (Reference Roberts, Hsiao, Berman and Reich2008) book: Getting Health Reform Right: A Guide to Improve Performance and Equity. Specifically, in terms of assessing legal rules, I focused more on assessing the ‘consistency’ and ‘coherence’ of legal rules because they are also the key to the rule of law (Fuller, Reference Fuller1969). Regarding the assessment of regulatory agencies, the benchmark is ‘government capacity’ (i.e. ‘political structure’, ‘professionalism of bureaucrats’ and ‘reliability’). Through the diagnostic process, I intended to answer the question: does China have effective legal–regulatory strategies to control and support the development of PMIs?

5.2 Bias

The bias of the literature search was minimised by including the analysis of classic monographs. Some search results from Google Scholar were excluded due to not being published in English.

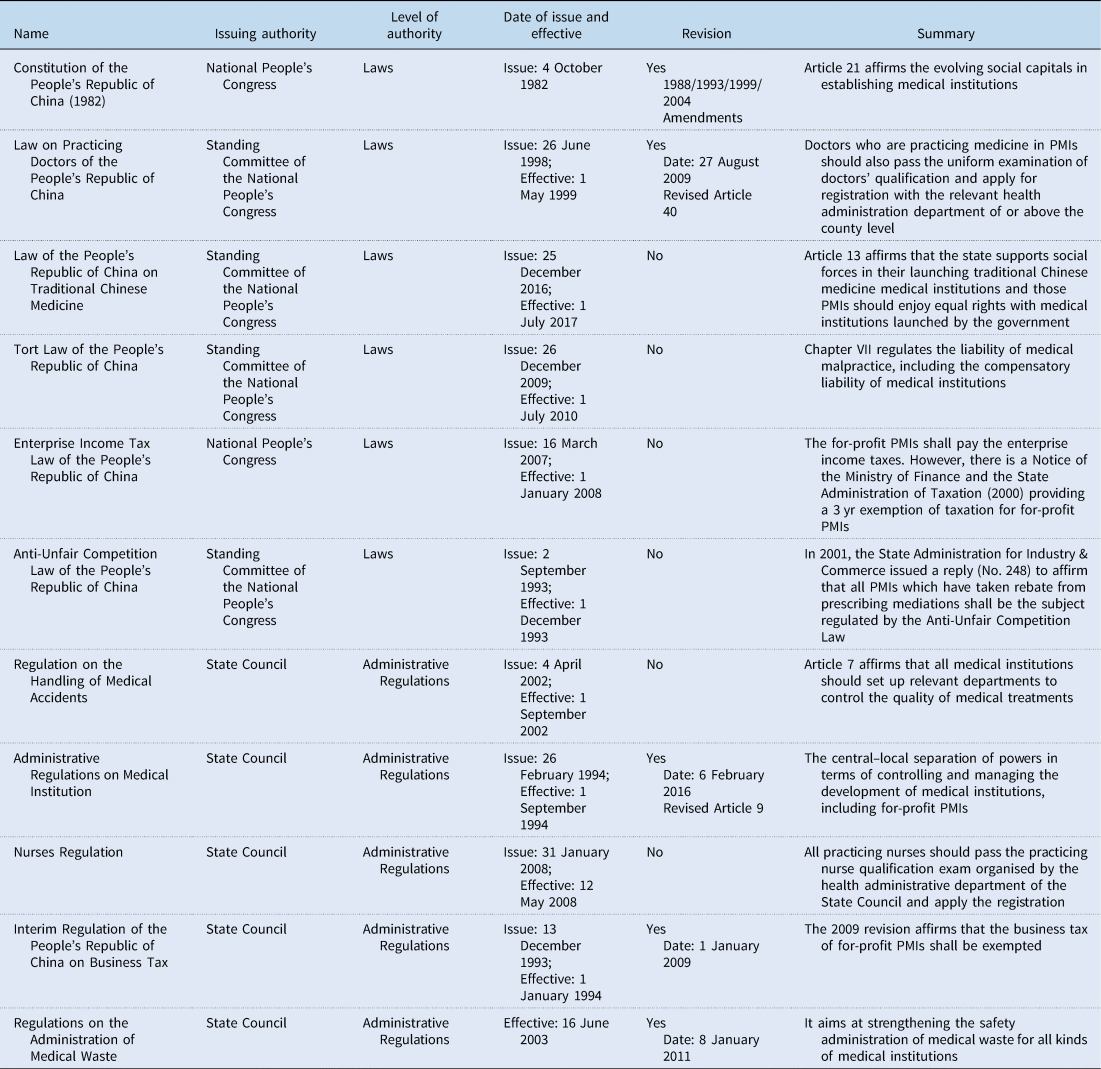

With regard to the selection of legislation, I merely focused on assessing the legal rules which had been enacted by the National People's Congress or the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (Table 1). These legal rules have higher legal authority in China's legal system, but there was actually a lack of such legal rules regulating PMIs.

Table 1. Laws and administrative regulations concerning PMIs in China

Source: Pkulaw, http://en.pkulaw.cn/. Accessed 12 February 2018.

In terms of my diagnostic process, however, the ‘control knob’ framework was formulated to provide guidelines for improving health care reform. These guidelines may also be helpful for diagnosing the performance of health care systems and adjusting the direction of government actions (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Hsiao, Berman and Reich2008).

6. Results and discussion

6.1 Deficiencies in legal–regulatory strategies concerning PMIs in China

6.1.1 Effective legal rules: weak coherence, inconsistency and legislative vacancy

Like many other countries, protecting and promoting the right to health in China is mainly achieved by enforcing legal rules in other legal fields, such as administrative law, contract/tort law or even criminal law. As a consequence, legal rules regarding health care tend to be fragmented, as are the legal rules related to PMIs. Figure 2 presents a macro view of effective legal rules concerning PMIs in China. The majority of effective legal rules relating to PMIs seem to have lower legal authority in the Chinese legal system, making it very difficult to enforce them. According to the Legislation Law of the People's Republic of China (2015 Amendment), the Constitution in China has the highest legal authority. Below this are laws, administrative regulations, department rules and local regulatory documents. Compared to the laws and administrative regulations, department rules and local regulatory documents have lower legal authority in the Chinese legal system. These are likely to be less stable, easily clash with each other and endanger substantive discretion during enforcement. PMIs are mainly regulated through department rules and local regulatory documents in China. For instance, a department regulatory document issued by the State Administration for Industry and Commerce deals with the question whether the ‘drug mark-ups’ of not-for-profit PMIs should be regulated by the Anti-Unfair Competition Law or not. Although some legal rules with a higher legal authority (i.e. laws and administrative regulations) do exist for regulating PMIs in China (Table 1), they are few and not specifically designed for regulating PMIs. Due to the lack of legal rules with a high legal authority at the central government level, PMIs are regulated unevenly across local governments. As a consequence, the coherence of legal rules relating to PMIs in China is relatively weak.

Furthermore, legal rules concerning PMIs also encounter the problem of inconsistency. The strictest part of regulation is always centralised at the registration stage, while less effort is devoted to regulating the behaviour of PMIs after they obtain a certificate from the relevant registration agencies. As Chapman (Reference Chapman2014) said, it is crucial to take measures in advance (e.g. registration and licensing strategies) to control the upcoming behaviour of the private sector in line with the human rights principles. Nevertheless, it is equally important to monitor and control the behaviour of PMIs after they obtain the certificate. This therefore deserves more attention at the current stage because regulating PMIs after registration is more likely to be overlooked.

Besides inconsistency and weak coherence, a marked disagreement regarding the legal attribute of PMIs, especially for-profit ones, may present an extra challenge for enforcement because of a legislative vacancy. In literature, the question of whether for-profit PMIs should be treated as social institutions or as market entities has been discussed intensively (Bloom, Reference Bloom2001; Nichols et al., Reference Nichols, Ginsburg, Berenson, Christianson and Hurley2004). Scholars, especially human rights professionals, lean in favour of regarding for-profit PMIs as social institutions, considering the special nature of health care in terms of morality and ethics. Conversely, for-profit PMIs themselves are willing to be identified as free market competitors, even though they run a ‘business’ that influences people's lives. This controversial issue is made worse by some health policies in China. The Chinese government tends to force for-profit PMIs to increasingly assume social responsibility whilst requiring them to deliver health care services as efficient and productive as other free competitors in the market. As illustrated in Table 1, for-profit PMIs are temporarily treated as business entities in China. However, the ‘business’ run by for-profit PMIs is a health service which is in a morally special position and which cannot therefore be totally handed over to the market (Daniels, Reference Daniels1996, Reference Daniels2001). Thus, the legislative vacancy leaves patients at the mercy of a ‘laissez-faire’ policy in health care in China (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Hsiao, Berman and Reich2008).

6.1.2 Relative regulatory agencies: the negative effects of decentralised political structure, the low professionalism of bureaucrats and lack of reliability

Government capacity is an essential determinant of regulatory success, especially in terms of promulgating and enforcing regulations (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Hsiao, Berman and Reich2008). As argued by Roberts et al. (Reference Roberts, Hsiao, Berman and Reich2008), the government capacity has an interactive relationship with the level of economic development and cultural attitude. Thus low- and middle-income countries have relatively lower administrative capacity and less support from the citizens. This section therefore aims at verifying this assumption by assessing relative regulatory agencies concerning PMIs in China with three benchmarks: political structure, bureaucratic professionalism and reliability.

Following three waves (1958, 1970 and 1978) of decentralisation reform in China, the administrative power of the central government has gradually been transferred to local governments and specific government agencies in order to maximise overall social welfare and satisfy the diverse sets of preferences of local people (Hayek, Reference Hayek1945; Tiebout, Reference Tiebout1956). Reflected in health care, regulating PMIs involves a number of government agencies in China (Table 2). Some regulatory agencies control and manage many different PMIs but focus on different aspects of PMIs. For example, the China Food and Drug Administration is responsible for supervising the use of drugs and medical devices, the General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine oversees the quality and safety of medical products, while the Ministry of Environmental Protection is responsible for medical waste. Various other government agencies are assigned to manage the differences between for-profit PMIs and not-for-profit PMIs (e.g. administrative processes and taxation). In terms of administrative processes, for-profit PMIs need to apply for registration and obtain a certificate from the State Administration for Industry and Commerce because they are temporarily regarded as business entities. The registration process for non-for-profit PMIs, on the other hand, is under the control of the Ministry of Civil Affairs and is comparatively simple. With regard to taxation, for-profit PMIs are required to pay corporate tax to the State Administration of Taxation, while not-for-profit PMIs are not. Although for-profit PMIs have a three-year exemption from taxation, very few for-profit PMIs benefit from that policy because the registration and other administrative processes normally take longer than three years. Such a self-contradictory policy endangers the reliability of relative regulatory agencies. Furthermore, due to the gap between the policy design and the real-life situation, more and more for-profit PMIs decide to become non-for-profit ones. Such a change would make it difficult to manage PMIs and thus challenges the capacity of relative regulatory agencies.

Table 2. Main sector on the state level in regulating PMIs in China

Source: Meng et al. (Reference Meng, Yang, Chen, Sun and Liu2015).

As illustrated in Table 2, all involved government agencies have been assigned responsibility for regulating PMIs. As such, the political structure seems to function well. However, there are certain overlapping areas where the professionalism and reliability of the involved government agencies encounter challenges. In order to ensure professionalism and reliability, the good performance of regulation expects these government agencies to work together to address the overlapping areas (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Hsiao, Berman and Reich2008). In China however, due to the lack of a legislative authorised division of power among these involved government agencies, regulating overlapping areas usually results in disagreements, inaction and corruption rather than checks and balances. Take drug policy for example, where the government agencies involved are the China Food and Drug Administration, the National Development and Reform Commission and the National Health and Family Planning Commission (Table 2). They all have some power to manage and supervise the distribution and utilisation of drugs in PMIs, but very few can be identified as the liable party in the event of a trade-off. This raises a question regarding the capacity of the Chinese government and the need to establish an independent regulatory body.

Overall, the issues raised (i.e. the inconsistency and weak coherence of legal rules and the lack of adequate government capacity) not only demonstrate that China does little to govern and regulate the gradually increasing number of PMIs in health care, but more importantly highlights the need to address the regulatory role of the state in guiding the private sector towards achieving national health goals.

6.2 Applying ICESCR General Comment No. 14 to improve legal–regulatory strategies concerning PMIs in China and recommendations

Considering the fact that China has signed and ratified all the relevant international treaties regarding the protection and promotion of people's health, provisions of those treaties should be applicable in guiding related health policies and law in China. In accordance with the ICESCR General Comment No. 14, regulating PMIs must take the following aspects into consideration: identifying attribute, securing equity, ensuring quality and facilitating transparency (Albreht, Reference Albreht2009). First and foremost, enacting an ‘umbrella health law’ is vitally important for strengthening the weak coherence of effective legal rules. In 2017, the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress started the drafting process of such an ‘umbrella health law’, named ‘the Basic Healthcare and Health Promotion Law’Footnote 2 (hereinafter ‘the Basic Health Law’). Now, it is in its second round of public hearing and not yet ready for issue. In the second draft of the ‘Basic Health Law’, only Article 9Footnote 3 is related to PMIs which is not sufficient. The ‘Basic Health Law’ should include a separate chapter for regulating PMIs. Furthermore, this new law should be given a higher legal authority (e.g. the level of laws and administrative regulations) in the Chinese legal system in order to link the fragmented legal rules in other legal fields.

Secondly, the PMIs chapter of the ‘Basic Health Law’ should include legal rules to clarify the attribute of PMIs, especially for-profit PMIs. If for-profit PMIs continue to be treated as business entities, then new legal rules should focus on how to control and guide the profit-seeking behaviour of for-profit PMIs for achieving national health goals. If for-profit PMIs are regarded as social institutions, then new legal rules should be established for the distinction between for-profit PMIs and non-for-profit PMIs regarding the extent of their social responsibility.

Thirdly, the PMIs chapter of the ‘Basic Health Law’ should include legal rules to ensure equal access to health care and other health-related services provided by PMIs. Due to profit-seeking incentives, for-profit PMIs may limit access to health care services for certain groups of people or charge higher fees on the basis of age or gender. Legal rules on eliminating discrimination as such should be included in the PMIs chapter of the ‘Basic Health Law’.

Fourthly, ensuring the quality of health care provided by PMIs should be an essential task of the ‘Basic Health Law’. New legal rules should be enacted to control and regulate the marketing of PMIs, especially their profit-seeking activities after registration. Furthermore, requirements on the quality of health care services should be the same for both public medical institutions and PMIs. Responsibility for monitoring the enforcement of related legal rules should be assigned to an independent regulatory body. ‘Independent’ means that the regulatory body should be independent of all regulatory agencies of the central government and under the direct control of the State Council. In each local area (i.e. city or town level), the independent regulatory body should have its own branches for daily control. These branches are also independent of local governments and other government agencies.

Last but not the least, the PMIs chapter of the ‘Basic Health Law’ and the independent regulatory body should aim at facilitating the transparency of health care market. In the market of health services, information asymmetry impedes patients' access to good quality health care. In the real-life situation, for instance, doctors tend to recommend conservative treatments to their patients to avoid the risk of medical accidents and disputes if there are no relative regulatory rules (Havighurst, Reference Havighurst and Bloche2003). Even worse, doctors working for for-profit PMIs are ‘forced’ to prescribe treatments whose effects are relatively low but which generate high profits because they need to make a profit for their PMIs in order to keep their jobs. In this regard, new legal rules and the independent regulatory body need to be established to ensure that the involvement of PMIs does not limit people's access to health-related information and services. Future efforts can be devoted to making the price of health services transparent to patients, empowering patients to defend their medical rights and express other dissatisfactions, and to ensure that health professionals comply with the ethical codes of health services (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Brugha, Hanson and McPake2002).

7. Concluding remarks

The paper begins by conceptualising privatisation and identifying potential benefits and risks it may entail. Once privatisation is recognised as an inevitable tendency in health care, what truly matters is how to guide the gradually increasing private sector to contribute to achieving desired public policy goals. In China, the rapidly growing PMIs demonstrate the huge impact of privatisation on health care and the tension between the rapid expansion of privatisation and the less effective legal–regulatory strategies (i.e. effective legal rules and relative regulatory agencies). Thus, the overall aim of this paper is to find out: to what extent does privatisation impact on health care in China and how does the Chinese government fulfil its regulatory role in measuring the gradually increasing private sector properly (especially using legal measures) from a human rights perspective.

Through the case of PMIs, the paper observes that gradually relying on the private sector in health care not only makes the Chinese health care system more efficient, but it also diversifies health services and thus expands the accessibility of health care and protects patient rights in China. Nevertheless, there are also related concerns about involving the private sector in health care in China, such as the risks of violating human rights and deteriorating public health delivery, which raise a range of regulatory issues. In assessing current legal–regulatory strategies concerning PMIs in China, the paper identifies three major concerns regarding effective legal rules (i.e. weak coherence, inconsistency and legislative vacancy) and three difficult issues regarding government capacity (i.e. the negative effects of decentralised political structure, the low professionalism of bureaucrats and lack of reliability) that impede the proper functioning of regulatory agencies in China. As a plausible response, the paper recommends that the ‘Basic Health Law’ should be a separate chapter and should be assigned to regulating PMIs and also establishing an independent regulatory body to manage the issues of PMIs in China. Detailed recommendations are the practical implications of ICESCR General Comment No. 14.

The increasing involvement of the private sector in health care is not identified as purely a ‘good’ or a ‘bad’ tendency in itself. In most cases, how the state plays its role in regulating and governing the rapidly developing private sector is the key issue and of crucial importance.