Introduction

‘No health without mental health’. This statement has been endorsed by the WHO, the Pan American Health Organization, the EU Council of Ministers, the World Federation of Mental Health and the UK Royal College of Psychiatrists (Churchill, Reference Churchill2010). Mental disorders are an important source of long-term disability, dependency and mortality. The chronicity, severity and impact of many mental disorders contribute to 14% of the global burden of disease, although this number may be significantly underestimated due to the inadequate appreciation of the connections between mental disorder and other health conditions (Prince et al. Reference Prince, Patel, Saxena, Maj, Maselko, Phillips and Rahman2007). Despite its impact, mental health remains a low priority in most countries (WHO, 2010). A recent paper assessing US adults’ self-reported willingness to pay for treatments of mental health conditions and general medical conditions, found that respondents were less likely to pay for psychiatric disease treatments even though these diseases were recognised by participants as severe and burdensome health problems when compared to general medical diseases (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Damschroder, Kim and Ubel2012).

There is an increasing contradiction between the limited population impact of clinical treatments for mental disorders and the dramatic rise of mental disorders in the world (WHO Executive Board, 2011; Meng & D'Arcy, Reference Meng and D'Arcy2013). Mental health promotion aimed at promoting positive mental health by increasing psychological well-being (PWB), competency and resilience, and mental disorders prevention aimed at reducing or preventing the occurrence of mental disorders, are the most effective and cost-effective avenues to solve the contradiction (WHO, 2004).

Multiple disciplines, including social science, biological science, neurological science and genetics have provided significant insight into the role of risk and protective factors in mental disorders and mental health (WHO, 2004). Recently, Wittchen et al. (Reference Wittchen, Knappe, Andersson, Araya, Banos Rivera, Barkham, Bech, Beckers, Berger, Berking, Berrocal, Botella, Carlbring, Chouinard, Colom, Csillag, Cujipers, David, Emmelkamp, Essau, Fava, Goschke, Hermans, Hofmann, Lutz, Muris, Ollendick, Raes, Rief, Riper, Tossani, van der Oord, Vervliet, Haro and Schumann2014) reviewed the necessity and importance of understanding the role of a behavioural science in research on mental health and mental disorders, as most maladaptive health behaviours and mental disorders are caused by the interaction of developmental dysfunctions of psychological functions and processes as well as underlying neurobiological and genetic processes. They suggest that the fragmented and ‘disciplinary insularity’ of mental health research should be replaced by a trans-disciplinary effort with an emphasis on the behavioural science. Studies on mental health prevention in the field of behavioural science could provide new opportunities for psychiatric disease prevention and mental health promotion.

Mental health is not just the absence of mental disorders, it is ‘a state of well-being’ in which every individual is able to realise his or her own abilities, cope with daily stress, work productively and contribute to society (WHO, 2001). The terms quality of life, life-satisfaction, sense of well-being and PWB are often used interchangeably, they are commonly considered as positive psychology. However, PWB is not just about happiness or the absence of distress, but a relatively complex notion composed of six constructs (Ryff & Keyes, Reference Ryff and Keyes1995). PWB includes self-esteem, mental balance, social involvement, sociability, control of self and events and happiness. Coping strategies are generally categorised into positive and negative coping (or adaptive and maladaptive coping) (Smedema & McKenzie, Reference Smedema and McKenzie2010). ‘Positive coping’ and ‘negative coping’ are being used simply to describe the outcomes that have been associated with these types of coping strategies. Coping strategies can also be categorised as cognitive and behavioural coping. Positive coping, adaptive or ‘good’ strategies include seeking social support and physical exercise (Billings et al. Reference Billings, Folkman, Acree and Moskowitz2000; Folkman & Moskowitz, Reference Folkman and Moskowitz2000; Salmon, Reference Salmon2001), in contrast, going on as if nothing happened, self-destructive behaviour, and concentrating on what will happen next are seen as negative, maladaptive coping strategies (Lemaire & Wallace, Reference Lemaire and Wallace2010). Research on relationships among PWB, coping strategies and distress has shown that: (1) PWB and distress are correlated components of mental healthiness and psychiatric disease (Lamers et al. Reference Lamers, Westerhof, Bohlmeijer, ten Klooster and Keyes2011); (2) negative coping methods are associated with more severe psychiatric problems, depressive symptoms and life dissatisfaction in women with breast cancer (Hebert et al. Reference Hebert, Zdaniuk, Schulz and Scheier2009; Gustems-Carnicer & Calderon, Reference Gustems-Carnicer and Calderon2013); and (3) positive coping strategies have a beneficial effect on depressive symptoms, phobic anxiety and distress among undergraduates (Gustems-Carnicer & Calderon, Reference Gustems-Carnicer and Calderon2013). A better understanding of relationships among PWB, coping strategies and distress is pivotal to achieve a good mental health (Shiota, Reference Shiota2006). These factors can also be treated as targets for mental health promotion and mental health prevention.

There has been a significant amount of research on the latent constructs of PWB, coping, stress and distress scales (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Bormann, Cropanzano and James1995; Ryff & Keyes, Reference Ryff and Keyes1995; Masse et al. Reference Masse, Poulin, Dassa, Lambert, Belair and Battaglini1998; Brooks et al. Reference Brooks, Beard and Steel2006; Rexrode et al. Reference Rexrode, Petersen and O'Toole2008; Smedema & McKenzie, Reference Smedema and McKenzie2010). Pottie & Ingram (Reference Pottie and Ingram2008) examined effects of coping on daily distress and PWB in parents of children with autism, and found that higher levels of positive mood were associated with positive coping strategies, including problem focused coping, social support, positive reframing, emotional regulation, whereas, negative coping methods, e.g. blaming, withdrawal, etc. predicted lower level of positive mood. Blalock et al. (Reference Blalock, Devellis and Giorgino1995) explored the roles of coping and stress in adjustment of osteoarthritis, and found that: (1) coping strategies predicted the level of PWB at 6 month; (2) social withdrawal and self-criticism were associated with distress; and (3) positive coping (e.g. problem solving) had a positive effect on PWB. A recent study in patients with glioma and their caregivers showed that patients’ PWB and distress were influenced by availability of support, personal resilience, etc. (Cavers et al. Reference Cavers, Hacking, Erridge, Kendall, Morris and Murray2012). However, to our knowledge, no study has examined the different roles played by distress and coping strategies in PWB for the general population and diverse disease groups in a single population.

The present study investigated structural relationships among PWB, distress and ways of coping, and identified major correlates of PWB for both the general population and subgroups (e.g. disease groups) using a nationally representative Canadian population data.

Methods

Data source

Data analysed were from the public use microdata file of the Canadian Community Health Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being 1.2 (CCHS 1.2), which is a nationally representative community mental health survey designed to collect cross-sectional data on mental health status, determinants of health and access to and perceived need for formal and informal services and supports, functioning and disability and covariates. A more recent 2012 Canadian Community Survey of Mental Health while containing data on the prevalence of mental disorder and distress did not assess coping or PWB. The CCHS 1.2 is unique in containing population level data on ways of coping, PWB, distress and diagnosable mental disorders. The CCHS 1.2 interview included a modified version of the World Mental Health-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI) instrument used by the WMH 2000 project. The WMH-CIDI is a lay-administered psychiatric interview that generates a profile of those with a disorder using the definitions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV). The survey also collected data on a variety of measures of psychosocial functioning as well as standard socio-demographic variables. Well-trained lay interviewers using computer-assisted interviewing procedures administered the survey. The survey used a multistage stratified cluster design to ensure the national representativeness of the data. It was conducted by Statistics Canada between May and December 2002 (Gravel & Béland, Reference Gravel and Béland2005). The overall response rate was 77.0%, with a total completed sample size of 36 984 respondents (Patten et al. Reference Patten, Wang, Williams, Currie, Beck, Maxwell and El-Guebaly2006). More details about this survey can be found in previous publications (Dewa et al. Reference Dewa, Lin, Kooehoorn and Goldner2007).

Measures

The measures analysed in this study included a Psychological Well-Being Scale, a Psychological Distress Scale, a Ways of Coping Scale and modules on chronic physical conditions, selected common mental disorders and socio-demographic information.

Model indicators

Psychological well-being

Masse's 25-item Psychological Well-Being Scale (Masse et al. Reference Masse, Poulin, Dassa, Lambert, Belair and Battaglini1998) was used with an altered scoring system (items scored as 0–4 with a total score range of 0–100) to measure PWB. Higher scores indicated greater well-being. As noted earlier the scale contains six constructs: self-esteem, social involvement, mental balance, control of self and events, sociability and happiness. The Cronbach alpha – a measure of internal consistency of the scale (Cronbach, Reference Cronbach1951) was excellent (α = 0.94).

Distress

The ten-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) designed to measure the level of distress and severity associated with psychological symptoms in population surveys was used in this survey (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Andrews, Colpe, Hiripi, Mroczek, Normand, Walters and Zaslavsky2002). The K10 has been identified having four constructs (labelled as nervous, negative affect, fatigue and agitation) (Brooks et al. Reference Brooks, Beard and Steel2006). The internal consistency was 0.87.

Ways of coping

The 14 questions on ways of coping used in this survey were derived and modified in wording from three coping scales (Statistics Canada, 2004). The majority of questions (ten items) were taken from Folkman and Lazarus's Ways of Coping Revised (WOC-R) (Folkman & Lazarus, Reference Folkman and Lazarus1985). Other questions were selected from Amirkhan's Coping Strategy Indicator (CSI) (three items) (Amirkhan, Reference Amirkhan1990) and Carver et al's COPE scale (one item) (Carver et al. Reference Carver, Scheier and Weintraub1989). Because the coping questions in the survey were derived from three coping scales, we conducted exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to identify the constructs of positive coping and negative coping captured by the 14 items. Positive coping and negative coping were found to have three constructs each: problem solving, somatic relief and spirituality for positive coping and internal avoidance, self-destructive behaviours and external avoidance for negative coping. The internal consistency of positive and negative coping sub-scales was 0.54 and 0.64, respectively. Appendix 2 has the detailed information of all three scales studied.

Subgroup categories

Socio-demographic variables (age, gender, marital status, income, education and immigration status), physical and psychiatric disease groups (self-reported long-term medical conditions diagnosed by a health professional, which included 31 chronic health problems, lifetime major depressive disorder, lifetime manic episode, lifetime panic disorder, lifetime social phobia and lifetime agoraphobia) were considered in the subgroup analyses.

Data analyses

The cross-validation test was applied to assess the generalisability of our results to an independent dataset. We randomly divided the CCHS 1.2 data into two sets, so both datasets had equal sample size. One dataset was used for training and another for validation. EFA, CFA and structural equation modelling (SEM) were used to investigate the relationships among PWB, ways of coping and distress. Factor analysis and SEM are statistical techniques for testing and estimating relationships by reducing the number of observed variables into a smaller number of latent variables (Schreiber et al. Reference Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow and King2006). EFA has been used to simplify interrelated measures and to explore the possible structure that underlies a group of observed variables (Child, Reference Child1990). CFA is used to verify the structure that has been identified a priori by EFA or the hypothesis that have been proposed. SEM is a general multivariate analysis technique that incorporates and integrates path analysis and factor analysis, and also has been proven useful in solving many substantial social and behavioural sciences analysis problems. SEM was chosen to analyse the data, as it is a highly versatile tool frequently used in psychology and related areas to investigate complex relationships among variables.

In SEM, the key variable(s) of interest is usually ‘latent construct’, which may be hypothetical or unobserved. SEM consists of a measurement model, which shows relationships between latent constructs and their indicators and a structural model, which includes the relationships among the latent constructs (Schreiber, Reference Schreiber2008). The measurement model is evaluated through EFA and CFA, and structural relations of the latent factors are then modelled by a structural model (Lei & Wu, Reference Lei and Wu2007).

Data analyses were performed in three major stages – as outlined in Fig. 1. In the first stage, the six-construct model of PWB (Masse et al. Reference Masse, Poulin, Dassa, Lambert, Belair and Battaglini1998) and the four-construct model of distress (Brooks et al. Reference Brooks, Beard and Steel2006) were tested with CFA for each dataset independently. We also conducted EFA and CFA for the ways of coping questions. In the second stage, we conducted the initial structural model based on the three measurement models (PWB, distress and coping) and our hypothesis. The goodness-of-fit test was tested for all measurement and structural models. The model chi-square, the comparative fit index (CFI) (Bentler, Reference Bentler1990), the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Steiger, Reference Steiger1990) and the normed fit index (NFI) (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999) were used to test the model fit and further fitting. Acceptable fit values for the CFI and NFI are close to 1.0 (Bentler, Reference Bentler1990) and for the RMSEA less than 0.06 (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). The Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used to determine the better fitting model. Once an initial model fitted well, we did not modify it to achieve even better fit (MacCallum et al. Reference MacCallum, Browne and Sugawara1996). Finally, in the third stage, we used our final model to explore the differences between population and disease subgroups. All the analyses were conducted using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics Version 19.0. NY: IBM Corp.), and AMOS (Arbuckle, Reference Arbuckle2006).

Fig. 1. The processes of data analysis.

Results

The chi-square test was used to examine the demographic differences between the training and validation datasets. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics on the socio-demographic variables for the training and validation datasets. There were no statistically significant statistical differences between the two datasets across different demographic characteristics (p > 0.05).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for socio-demographic variables between the training and validation datasets

In the first stage, CFA was used to test measurement models of PWB and distress. A measurement model of ways of coping was built using the training dataset, and validated by the validation dataset. A structural model was built based on the three measurement models using the training dataset. We evaluated the assumptions of multivariate normality and checked the outliers. No univariate or multivariate outliers were observed. The maximum-likelihood estimation was used because our data (training and validation datasets) were normally distributed. The goodness-of-fit test was used for both measurement and structural models. All measurement and structural models represented a good fit (Appendix 1). Although all chi-square tests are significant, other goodness-of-fit indices suggest a good fit between the models and the observed data (CFI greater than 0.95, RMSEA smaller than 0.06 and NFI greater than 0.95) (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). A criticism of the chi-square statistic as a measure of model fit is that as the sample size increases, the likelihood of getting significant differences between the estimated and the actual matrices also increases and the CCHS.12 survey is a very large with 36 984 subjects (Ullman, Reference Ullman, Tabachnick and Fidell2001).

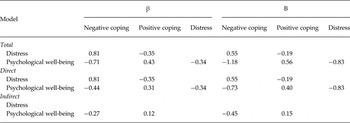

In the second stage, the structural model built was validated by the validation dataset. Similarly, the goodness-of-fit test was examined. To improve the fit of the structural model, re-specification of the model was attempted to try to achieve a better-fit model. Figure 2 provides the final structural model for the relationships among PWB, ways of coping and distress. Distress was related positively to negative coping (standardised coefficient = 0.81) and negatively related to positive coping (standardised coefficient = −0.35). Positive coping was predictive of a higher level of PWB (standardised coefficient = 0.43), including a direct effect (standardised coefficient = 0.31) between positive coping and PWB and an indirect effect between positive coping and PWB mediated by distress (standardised coefficient = 0.12). Whereas, negative coping predicted a lower level of PWB (standardised coefficient = −0.71), including a direct effect (standardised coefficient = 0.44) between negative coping and PWB and an indirect effect between negative coping and PWB mediated by distress (standardised coefficient = −0.27). PWB was negatively related to distress (standardised coefficient = −0.34) (Table 2).

Fig. 2. The final structural model for the relationships among ways of coping, distress and PWB. Note: This is a simplified figure to represent standardised coefficients of the final structural model for the relationships among ways of coping, distress and PWB. Distress was related positively to negative coping and negatively related to positive coping. Positive coping was predictive of a higher level of PWB, including a direct effect between positive coping and PWB and an indirect effect between positive coping and PWB mediated by distress.

Table 2. Results from the final fit structural model of the validation dataset

β = standardised regression coefficient; B = un-standardised regression coefficient.

In the third stage, we used our final structural model to test differences between diverse diseases subgroups by qualitatively comparing the strongest path between subgroups. There were no significant differences in the pattern of standardised coefficients for the structural model between men and women or for other socio-demographic groups by age, marital status, income, education or immigration status (Table 3). A significant difference in the pattern of standardised coefficients for the structural model was observed between the lifetime major depressive disorder group and depression-free group. The path between distress and PWB was the strongest relationship in the depression group, whereas the non-depressed group had the path between PWB and negative coping as the strongest. This phenomenon was also observed for the social phobia and chronic condition subgroups. In contrast, the path between PWB and negative coping was the strongest relationship in agoraphobia group and the path between distress and PWB was the strongest relationship in agoraphobia-free group. The path between PWB and distress was the strongest relationship for lifetime manic episode group and manic episode-free group. This was also true for both panic disorder group and panic disorder-free group.

Table 3. Standardised regression coefficients for subgroups with the final structural model

Note: The bolding of standardised regression coefficients in the table indicates the major coefficient for each model.

Discussion

Principal findings

The present study investigated the structural relationships among PWB, distress and ways of coping, and identified major correlates of PWB for the general population and subgroups using national representative data of the Canadian population. The study results generally confirm our hypotheses that: distress was positively related to negative coping and negatively related to positive coping; positive coping predicted a higher level of PWB, whereas negative coping was correlated with a lower level of PWB. PWB was negatively related to distress. The same relationships were also found in the subgroups. The path between PWB and distress was the most dominant one among those with psychiatric disease (except agoraphobia) and chronic physical disease. Our results further suggest that distress is the most important predictor for PWB. For people with psychiatric diseases, attention should be focused on elimination of distress to maintain a higher level of PWB. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the importance of distress and coping strategies in PWB in different subgroups of a general population using a large national population-based sample, which has high stability and provides greater generalisability for our findings.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study has the following strengths: (1) we used the CCHS 1.2 – a large-scale dataset, which can provide more precise results as a result of its large sample size. The large sample is able to more accurately model the population measured and with the large sample, parameter calculations are minimally influenced by the introduction of new participants, ensuring stability of parameter estimation. The stability of model findings is sensitive to the sample size (Tanaka, Reference Tanaka1987). (2) Our model was based on a national population-based data; therefore our findings can be generalised to similar population settings. (3) The analyses using both the training and validation datasets provide an additional test of the stability and generalisability of the model. The interpretations of the present study need to consider the following limitations. First, this study took measurements at only one-point time, it implies that the relationships examined in the model are purely correlations/associations and inferences of causality are inappropriate. Second, all measures used in this study, including diagnoses of psychiatric problems, were based on self-report, though the WMH-CIDI questionnaire applied the DSM-IV criteria to assess psychiatric diseases. Self-report measures may have validity problems. Respondents may exaggerate or underreport the severity or frequency of problems. The internal validity of results may be influenced by self-report measures. Third, although the overall internal consistency is good for the scales of distress and PWB, the internal consistency of positive and negative coping sub-scales is low, which may have a negative influence on reliability of the scale of ways of coping. Fourth, data on PWB, distress and ways of coping was collected with respect to a 30-day reference period, which may lead to recall bias. It influences the accuracy or completeness of the recollections retrieved by respondents regarding events or experiences from the recent past.

Comparison with other studies

Previous literature has consistently suggested that negative coping correlates with lower PWB and greater distress, whereas positive coping correlates positively with greater PWB and negatively with distress (Diong & Bishop, Reference Diong and Bishop1999; Sung et al. Reference Sung, Puskar and Sereika2006; Frydenberg & Lewis, Reference Frydenberg and Lewis2009). The structural relationships among PWB, distress and ways of coping are reconfirmed by our large nationally representative sample. However, no study has been conducted to explore the relationships among PWB, distress and ways of coping for different subgroups. Our findings identified major correlates of PWB in both the general population and population subgroups. The regression coefficients of the structural model were consistent across different demographic subgroups. Negative coping had a major impact on distress for all demographic subgroups. Whereas, for the population with diseases (both physical and psychiatric diseases, except agoraphobia), distress was the more important correlate than the person's coping strategies in determining subjective PWB.

Although negative coping was correlated to positive coping, negative coping was positively related to distress, as more negative coping methods anticipated higher distress, whereas positive coping predicted lower distress. Both negative and positive coping were directly related to PWB, with the indirect mediation of distress. The findings are in line with previous literature – negative coping in a very stressful situation has a negative impact on distress, whereas positive coping tends to reduce distress (Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Dell'Oliver, Koch and Buckler2002; Sohl et al. Reference Sohl, Schnur, Sucala, David, Winkel and Montgomery2012), and people who had a higher distress reported a lower level of PWB (Borren et al. Reference Borren, Tambs, Idstad, Ask and Sundet2012). The mechanism(s) behind these relationships is not universal. One possible explanation is that maladaptive behaviours (negative coping) may be related to lower self-esteem, which is linked to distress. Alternatively, personality processes could affect the type of coping strategies chosen through stress appraisal processes. Park et al. (Reference Park, Heppner and Lee2010) examined relationships of maladaptive coping style, self-esteem and distress among 508 Korean college students. They found that maladaptive coping was positively associated with distress and negatively influenced on self-esteem. Studies on self-esteem have found that individuals with poorer self-esteem suffer significantly more depressive symptoms and distress (Houlihan et al. Reference Houlihan, Fitzgerald and O'Regan1994). Another possible explanation is stress appraisal process. Major et al. (Reference Major, Richards, Cooper, Cozzarelli and Zubek1998) examined the effects of personality on distress, well-being and decision satisfaction in a longitudinal study of 527 women who had first-trimester abortions, and found that: (1) women with more resilient personalities viewed their abortion as less stressful and had more self-efficacy for coping with the abortion; and (2) more positive appraisals projected better acceptance, well-being and a positive coping style.

Implications for practice

It is suggested that mental health prevention and promotion in a general population should target reducing negative coping strategies to improve PWB, as negative coping was the strongest predictor of increased distress in the general population. Preventive public health actions should include: (1) disseminating the consequences of negative coping strategies; (2) recognition and early identification of negative coping's signs in a variety of social environments, e.g. schools, workplaces, etc. should be addressed; and (3) stress availability and benefits of positive coping strategies under different real life stressful scenarios.

Increasing the general public's knowledge and practice of adaptive coping strategies would seem to ideally suited to public mental health interventions and ideally suited to a longer term ehealth or internet education and prevention strategies. Internet plus prevention programmes have high levels of consumer acceptance and adherence and are seen to have great mental illness prevention potential (Gun et al. Reference Gun, Titov and Andrews2011; Christensen & Petrie, Reference Christensen and Petrie2013).

In this study, the path between PWB and distress was the most dominant one among those with psychiatric disease (except agoraphobia) and chronic physical disease. Patient oriented psychiatric intervention and treatment should be directed to reducing the symptoms of distress. For mental health care practitioners distress reduction is a credible and immediate primary target for a one-on-one or small group clinical setting in order to maintain or improve their patients’ level of PWB and a prerequisite to more overarching behavioural changes. Therapeutic lifestyle changes (TLCs) are lifestyle factors, such as increasing physical activity, improving diet, changing work environment, increasing social participation, etc. They are potent in determining both physical and mental health, as they can reduce the risk of occurrence of cancers, cardiovascular diseases, obesity, etc., and also act as psychotherapy or treatment for some mental disorders (Frattaroli et al. Reference Frattaroli, Weidner, Dnistrian, Kemp, Daubenmier, Marlin, Crutchfield, Yglecias, Carroll and Ornish2008; Meng & D'Arcy, Reference Meng and D'Arcy2013). These factors are related to coping skills. Some religious behaviours can be seen as positive coping methods, as they could predict better ego, moral and cognitive development (Alexander et al. Reference Alexander, Rainforth and Gelderloos1991). TLCs are currently underutilised as the importance of lifestyle factors in mental health is underestimated (Walsh, Reference Walsh2011). Important TLCs, e.g. exercise, relaxation, stress management, etc. should be introduced and used by medical professionals as means of reducing distress and improving PWB.

Author Contributions

X.M. and C.D. conceived and designed the study, and wrote and revised the manuscript. X.M. performed and analysed the study data.

Financial Support

This research was supported by funding from the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation (SHRF), and Alfred E. Molstad Trust, Department of Psychiatry, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatchewan, Canada.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Appendix 1. Fit statistics for measurement and structural models of the training dataset

Fit statistics for measurement and structural models of the training dataset

Appendix 2. The detailed information of the scales used in the present study

Psychological well-being

The following statements that people might use to describe themselves. Please use ‘almost always’, ‘frequently’, ‘half the time’, ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ to rate each statement.

Sub-scales of PWB

-

• Self-esteem

-

- During the past month, …

-

- you felt self-confident.

-

- you felt satisfied with what you were able to accomplish, you felt proud of.

-

- you felt loved and appreciated.

-

- felt useful.

-

-

• Mental balance

-

- During the past month, …

-

- you felt emotionally balanced.

-

- you were true to yourself, being natural at all times.

-

- your life was well-balanced between your family, personal and professional activities.

-

- you lived at a normal pace, not doing anything excessively.

-

-

• Social involvement

-

- During the past month, …

-

- you were a ‘go-getter’, you took on lots of projects.

-

- you had goals and ambitions.

-

- you felt like having fun, participating in sports and all your favourite activities and hobbies.

-

- you were curious and interested in all sorts of things.

-

-

• Sociability

-

- During the past month, …

-

- you smiled easily.

-

- you did a good job of listening to your friends.

-

- you got along well with everyone around you.

-

- you had a good sense of humour, easily making your friends laugh.

-

-

• Control of self and events

-

- During the past month, …

-

- you were able to clearly sort things out when faced with complicated situations.

-

- you were quite calm and level-headed.

-

- you were able to easily find answers to your problems.

-

- you were able to face difficult situations in a positive way.

-

-

• Happiness

-

- During the past month, …

-

- you found life exciting and you wanted to enjoy every moment of it.

-

- you had the impression of really enjoying life.

-

- you felt good, at peace with yourself.

-

- you felt healthy and in good shape.

-

- your morale was good.

-

Distress

The following questions were used to describe themselves. Please use ‘all of the time’, ‘most of the time’, ‘some of the time’, ‘a little of the time’ or ‘none of the time’ to rate each question.

Sub-scales of distress

Nervous

-

• During the past month, i.e. from [date] 1 month ago to yesterday,

-

- about how often did you feel nervous?

-

Negative affect

-

• During the past month, i.e. from [date] 1 month ago to yesterday, …

-

- about how often did you feel hopeless?

-

- about how often did you feel sad or depressed?

-

- about how often did you feel so depressed that nothing could cheer you up?

-

- about how often did you feel everything was an effort?

-

- about how often did you feel worthless?

-

Fatigue

-

• During the past month, i.e. from [date] 1 month ago to yesterday, … about how often did you feel tired out for no good reason?

-

- about how often did you feel restless or fidgety?

-

- about how often did you feel so restless you could not sit still?

-

Agitation

-

• During the past month, i.e. from [date] 1 month ago to yesterday,

-

- about how often did you feel so nervous that nothing could calm you down?

-

Ways of coping

The following questions about the stress were used to describe themselves. Please use ‘often’, ‘sometimes’, ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ to rate each question.

Sub-scales of coping

-

• Positive coping

-

- Spirituality

-

• How often do you pray or seek spiritual help to deal with stress?

-

- Somatic relief

-

• How often do you jog or do other exercise to deal with stress?

-

- Problem solving

-

• How often do you try to solve the problem?

-

• To deal with stress, how often do you try to look on the bright side of things?

-

• To deal with stress, how often do you talk to others?

-

• To deal with stress, how often do you try to relax by doing something enjoyable?

-

• Negative coping

-

- Internal avoidance

-

• How often do you blame yourself?

-

• To deal with stress, how often do you wish the situation would go away or somehow be finished?

-

- Self-destructive behaviours

-

• How often do you sleep more than usual to deal with stress?

-

• When dealing with stress, how often do you try to feel better by eating more, or less, than usual?

-

• When dealing with stress, how often do you try to feel better by smoking more cigarettes than usual?

-

• When dealing with stress, how often do you try to feel better by using drugs or medication?

-

• When dealing with stress, how often do you try to feel better by drinking alcohol?

-

- External avoidance

-

• When dealing with stress, how often do you avoid being with people?