Space syntax, GIS and perspectives on urban mapping

The dominant focus of mapping research in urban history focuses around the implementation of GIS (Geographical Information Systems) technologies for historical research, a field known as Historical GIS (HGIS).Footnote 1 By assigning two-dimensional co-ordinates from a given cartographic projection to diverse archive source materials in a process known as georeferencing, GIS enables ‘messy’ historical data to be precisely located on maps and plans of urban space. Mapped data can help identify relationships between phenomena that may not be self-evidently connected by revealing their shared location. While GIS offers a powerful platform for the mapping, analysis and visualization of historical spatial datasets, the relationship of these geographically spatialized data to the structure of urban space, most notably with respect to urban street networks, is rarely addressed systematically. One reason for this is that much historical data (and data in general) lends itself to aggregation at the scale of the administrative boundary at which it was originally collected; another is simply that, in the absence of a specific spatial-morphological proposition, it is not clear how an understanding of street network structure can advance historians’ interpretation of urban life itself.

Space syntax takes the town plan or map as the starting point for empirical research into the historical relationship between urban space and urban life on the basis of the network (i.e. relational) analysis of urban space viewed configurationally as a differentiated system of spaces. In this, it differs from culturally determined approaches to urban history in which historical maps and cartographies of data are typically treated as illustrative (i.e. to be explained contextually), rather than as artifacts that carry analytical weight and contribute explanations in their own right. One reason for this is because the relationship of many contemporary urban historians to maps remains ambivalent. Many, if not most, consider maps much as they would texts, as unreliable and compromised productions of particular social and cultural milieus. Such critical scrutiny of maps is essential but becomes problematic when it sustains, sometimes rather too axiomatically, the assumption that the primary value of maps to historical research is to reveal the ideologies that produced the representation or even the urban environment itself, rather than to probe their surfaces for clues as to how people actually lived in the past.

The dominance of the cultural emphasis on textuality in historical studies since the 1990s has, we argue, resulted in an epistemological blind spot that has obstructed urban historians from thinking about the ways in which maps can be approached empirically as sources for understanding the urban built environment as an inhabited space.Footnote 2 A shared enthusiasm for maps across the interdisciplinary spatial humanities still sits uneasily with many social and cultural historians’ sense that social-scientific ‘mapping’ techniques, largely associated with GIS, tend to privilege technical expertise and the demands of the methodological model over a contextual understanding of the source material. Yet from a space syntax perspective cartographic representations are morphologically as much as culturally encoded, offering detailed descriptions of the material affordances of historical built environments as much as codifications of the symbolic ordering of urban landscapes.

The central proposition of space syntax theory for urban-scale analysis is that the spatial configuration of the street network provides researchers with the elusive link between what the historical geographer Colin Pooley refers to as ‘patterns on the ground’ (the material city of built forms) and the corresponding social patterns they mediate and reproduce.Footnote 3 Space syntax analysis of maps and plans produces both visual and numerical descriptive data which can inform propositions, for example about patterns of movement, encounter and land use in the past, that can both be qualified by non-cartographic historical sources and help in their interpretation. This is especially powerful when historical sources exist at the resolution of the street or building plot (for example, census or business directory data). Such sources can be mapped on to contemporaneous plans of the street network – the ‘shape of habitable space’ as Penn calls it – rather than to relatively abstract area-based political or administrative boundaries, as is the norm in much HGIS scholarship.Footnote 4 Analysis of street networks using space syntax allows the relative accessibility of different street spaces to be quantified, thereby enabling the delineation of urban activities such as the diversity of business types or the structure of a kinship network, to be read back from the plan as socio-spatial as much as a socio-economic phenomena.

The space syntax analysis of urban street networks is typically implemented in a GIS environment but space syntax was not developed as a specifically GIS application, having been created for the purposes of architectural research and possessing its own portfolio of dedicated (mainly open-source) software.Footnote 5 Implementation of space syntax in a GIS environment is now standard but the emphasis on the analysis of built form configuration requires a rethink of HGIS epistemology.Footnote 6 Visualizations of the urban built environment made using GIS often have a contextual rather than an explanatory purpose, with the georeferenced basemap providing the background to the foregrounded arrangement of georeferenced data that constitutes the primary analytical focus. Here, the agency of the street network itself in explaining the patterning of historical data is likely to be subsumed in a generalized topographical description (for example, noting the location of buildings, open spaces and rivers) that comprises a necessary context but with little interpretative power. Such a contextual approach does not sufficiently challenge the widely held view amongst urban historians that equates a research focus on the spatial arrangement of urban built form less with the emergent patterning of everyday routines than with forces of ideological domination and control.Footnote 7 The effect of this strongly cultural emphasis, it is argued, is effectively to dematerialize the ‘noise’ of everyday urban life and repress the potential of built form in explaining its dynamics.

In this spirit, we deploy the term ‘spatial culture’Footnote 8 as a motif to propose how space syntax, both as a conceptual scheme and formal method of map and plan analysis, positions its contribution to the research agenda of urban history. Research in urban spatial cultures is specifically concerned with the proposition that the material or ‘artifactual’ arrangements of built forms is generative of social life through its historical role in mediating the production, reproduction and material embedding of social information across space and time.Footnote 9 This information is continually re-embodied in spatial practices (such as movement and encounter patterns) that are discretely located in space and time.Footnote 10 It proposes that the spatial-morphological analysis of town plans, used in conjunction with available evidence indicating how people lived, worked and socialized in urban space, can provide insights into the low-level hum of movements and meetings that sustained the quotidian life of towns and cities.

The remainder of this article is divided into three main sections: the first discusses space syntax research into the social history of the nineteenth-century city in order to highlight a number of important methodological themes; the second critically examines the theoretical principles of space syntax mapping methods, and the third identifies some historiographical contexts of space syntax research.

Space syntax research into the social history of the nineteenth-century city

Space syntax has been applied to many periods of urban history, not only by space syntax researchers but also by specialists from other fields, most notably archaeologists and historians of cities in the classical world.Footnote 11 Space syntax research in nineteenth-century cities has, we propose, now reached a level of maturity which is enabling it to extend beyond its own dedicated field to become part of a broader interdisciplinary conversation with urban and social historians.Footnote 12 In developing this dialogue, space syntax researchers have been attracted to a previous generation of historians and historical geographers of the nineteenth-century city who used social cartography to visualize census data in exploring questions such as the residential distribution of migrant groups and residential segregation, and more generally to those scholars concerned with the built environment of the city as much as with its representation.Footnote 13 Space syntax research in historical mapping positions itself in relation to this tradition in urban history, which, we believe, still has a contribution to make. This section reports on the growing corpus of studies using space syntax to examine how the configuration of urban form helped to shape the social history of nineteenth-century English cities and highlights five important methodological themes that are common, to a greater or lesser extent, across this body of work.

Identifying the spatial-morphological question in the historical questionFootnote 14

A recent interdisciplinary collaboration (2016–17) between Sam Griffiths and Katrina NavickasFootnote 15 explores how space syntax analysis can be deployed in conjunction with historical data to yield fresh insights into the relationship of urban space and diverse sites of political meeting.Footnote 16 The project uses an ArcGIS platform to join political meetings data compiled and georeferenced manually by Navickas, to spatial-morphological data produced using space syntax (i.e. configurational) analysis of the historical street networks of Manchester and Sheffield.Footnote 17 Analysing the structure of an historical street network makes it possible to assess the spatial, as well as the social, relationships of nineteenth-century political meetings.Footnote 18

While the project certainly aims at methodological innovation, its primary purpose is rooted in an historical question. Studies of industrial cities in Britain have traditionally focused on socio-economic and environmental conditions rather than on the arrangement of built form in explaining occurrences of political meetings. Literary sources and contemporary descriptions inflected with romanticism often represent the experience of the industrial city as intrinsically traumatic and oppressive. This portrayal informs an enduring tradition in urban sociology and town planning that represents the industrial city as a symptom (one might say a symbol) of an unjust society. As a commonly held, almost a priori, assumption, this view rather silences alternative readings of the industrial city as a highly complex social space characterized by distinctive and dynamic patterns of co-presence, movement and encounter between people, information, symbols and objects.Footnote 19 It follows that the focus of historical research has been on the large outdoor meeting rather than more routine popular political meetings that were the most characteristic form of political action in the industrial city.

The research project was implemented in a two-phase time-series database of over 1,000 political meetings and meeting places in Manchester (715 entries) and Sheffield (249 entries) between 1775 and 1850. A total of 185 sites in Manchester and 70 sites in Sheffield were identified and categorized. The majority of sites in both cities were pubs and inns, but they also included squares, assembly rooms, court houses, streets and theatres and purpose-built meeting buildings, among others. Two historical basemaps for each city were selected from the beginning and end of the time-series: Green's 1794 map of Manchester; and William Fairbanks’ 1797 map of Sheffield; and the two 5-inch to the mile first edition (1849–50) Ordnance Survey maps of both cities. These basemaps were first traced in ArcGIS to produce simplified road-line maps of the street networks which were then converted to space syntax axial and segment maps in DepthmapX space syntax software. This process produces a range of configurational variables associated with each road segment for analysis. A further stage of cartographic analysis of both cities, using methods from Conzenian urban morphology and space syntax research, provided a range of formal descriptions of urban spatial structure from the micro-morphological domain of the street-building interface to the street network of entire urban areas.Footnote 20

The next stage of analysis required joining the spatial configurational data (for each road segment) to the georeferenced point data (describing each political meeting) in the GIS. This spatial join enabled analysis of the relationship between the spatial structure of the urban built environment and the location of political meetings to be approached through the street network rather than being aggregated to arbitrary administrative or political boundaries imposed onto this space.

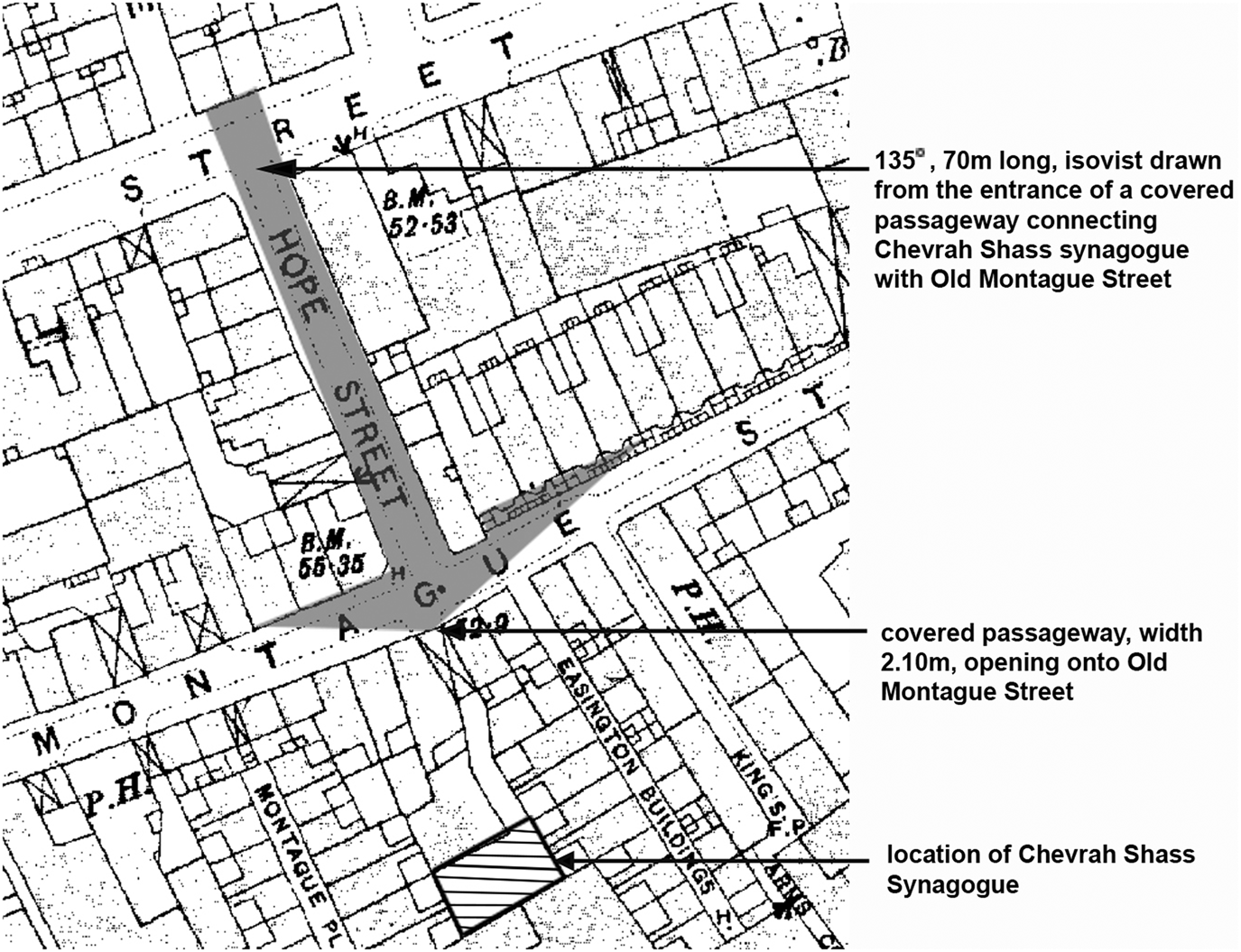

The visualization of locations of all the political meeting places in the Manchester database (Figure 1) was overlaid on a space syntax road segment map showing the 20 per cent most accessible segments that highlights the probable urban-scale structure of movement. Once the spatial-morphological data was joined to the historical meetings data in the GIS, the different categories of political meeting and meeting site were spatially profiled by assigning mean configurational values which could be compared. Three spatial variables from space syntax models are key to the profiling exercise and subsequent interpretation.

1. Accessibility: refers to how relatively close one urban space (e.g.) street or square is to another; that is how integrated or segregated the space is in relation to all other spaces in the urban system (or a subset of those spaces); the theory proposes that integrated space is more likely to be a movement destination than segregated space.

2. Foreground and background networks: in space syntax a ‘foreground network’ typically refers to the structure of space that connects different centres and sub-centres of a city and is associated with higher levels of movement, encounter, commerce and social co-presence, and more generally, with socially ‘generative’ action; a ‘background’ network typically refers to residential areas that are embedded in interstices of the foreground network and are said to be socially ‘conservative’ in the sense of reproducing existing social relationships, or at least localizing dissent.

3. Accessibility is pervasive and relative to urban scale: a spatial element such as a high street may function as an interface between a dense ‘noise’ of localized movements and proportionately fewer movements at relatively larger scales.

Figure 1. Location of political meeting places overlaid on space syntax street network analysis of Manchester in 1849, highlighting in dark grey the top 20 per cent most accessible segments. Image by Blerta Dino, Sam Griffiths and Katrina Navickas.

The baseline profiling exercise showed how, in Manchester and Sheffield, political meetings occurred in higher than average accessibility locations both at the urban scale and at the neighbourhood scale – often taking place at the interface of both. This tendency was stronger in Manchester than in Sheffield – suggesting that political meeting places in Manchester showed greater tendency to diversify their locations as the city's built environment expanded in the first half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 21

The picture emerging from the project is that in the cities of Sheffield, and especially Manchester, distinctive spatial infrastructures for political meetings can be identified. This proposition is useful in rebalancing the weight of research that focuses on the largest and most symbolically significant meetings and meeting places. It grounds new research that takes seriously the particular role of the industrial built environment in offering sufficient spatial-locational niches to sustain a broad range of meeting activities from the local to the city scale of urban space. It shifts the research emphasis from individual meetings to exploring the functional dynamics of a spatial culture of political meeting that was pervasive in industrial cities.

Joining historical data to spatial data precisely and at the highest possible resolution

An early example of space syntax historical research is a series of studies that drew on the extensive poverty surveys of London produced by Charles Booth in the 1880s and 1890s. Alongside a vast corpus of writing and statistics, the results of Booth's study had been captured on a detailed colour map, first published in 1889 and subsequently revised in 1898–99, which finely delineated an array of seven socio-economic gradations from poverty to prosperity. The space syntax analysis used these maps to explore the relationship between physical segregation and poverty in cities by linking the poverty data with the spatial (configurational) attributes of the city's streets and comparing the two.Footnote 22 This work demonstrated how a purely descriptive use of Booth's maps omits an important aspect of his findings regarding the deleterious effects that the specific arrangement of streets in cities, especially the physical segregation of areas, can have on the people living in them. Using a street-based GIS-supported analysis of the distribution of poverty classes, the study found a strong statistical association between poverty and low integration. Further analysis of changes in the street network, alongside Booth's second survey 10 years later, indicated that there was a circular influence between social and spatial change: slum clearances had had the effect of improving the economic situation of inhabitants of the immediate area, but this masked the fact that the poorest people were forced to move to cheaper (and less spatially privileged) locations elsewhere, breaking vital social ties.

The precise joining of spatialized social data to configurational space syntax data in a GIS is key to using space syntax for historical research. Linkages at the scale of individual addresses, building plots or streets are preferable to data that are aggregated to areal boundaries (polygons) that do not reflect the structure of everyday lived space. Even when data is visualized at the street scale, it is difficult to interpret what spatial distributions mean without being able to differentiate precisely between areas of the street network on which they are located. Peter Hall's early work in planning history used business directory entries overlaid on schematic maps of London neighbourhoods to analyse the changing spatial distribution of London's furniture industry from the nineteenth century onwards.Footnote 23 In 2016, a research collaboration between the Space Syntax Laboratory and Professor Howard Davis (University of Oregon) revisited this study specifically to examine the role of urban structure in supporting the organization of small-firm urban manufacturing. The space syntax research identified significant differences in the spatial morphologies of the two furniture-making areas (Fitzrovia and Shoreditch) that point to the existence of distinctive spatial cultures of manufacture that can help explain the different development trajectories of these industries, originally identified by Hall.Footnote 24

Figure 2 shows a data attribute table produced by the researchers into the spatial dynamics of London's nineteenth-century furniture industry that has been exported from GIS into MS Excel; each row shows one business address. For the project, business addresses from trade directories were first linked to individual building plots identified in historical Ordnance Survey maps and Goad fire insurance plans, and secondly, joined with space syntax variables from configurational analysis of London's street network assigned to the equivalent building plots derived from the historical plans.

Figure 2. Table of historical and space syntax data joined in GIS to analyse the accessibility of functional specialisms in London's nineteenth-century furniture industry. Data on London's furniture industry by permission of Professor Howard Davis, University of Oregon. Image by Blerta Dino and Sam Griffiths.

Qualifying and contextualizing the configurational analysis with archive source material

Historical research using space syntax relies upon a broad range of source materials to provide contexts, qualifications and to resolve ambiguities that are invisible in purely quantitative data. It deploys these additional sources to evaluate and tease out further meanings from sometimes opaque statistical patterns. In one example, space syntax research into the Jewish ‘ghetto’ (as conventions in social history tend to label it) of London's East End found a much greater level of residential mixing between Jews and non-Jews in the most spatially integrated streets.Footnote 25 This is consistent with the evidence from Charles Booth's notebooks (of interviews carried out with beat policemen), which points to the existence of a wide range of street types associated with various patterns of ethnic mixing. Kushner draws on oral testimony to argue similarly that boundaries between Jewish and non-Jewish were highly porous at that time, with East Enders engaging in many mixed activities.Footnote 26 Yet other oral sources speak of a much harder boundary between so-called Jewish districts and neighbouring streets, for which the Jewish incomer would be seen as an interloper.Footnote 27 The complexities and contradictions in the historical evidence provide the space syntax analysis with an essential interpretative context while suggesting new avenues of enquiry, in this case exploring configurational patterns of ethnic mixing using historical data on kinship patterns, subletting and employment.

A related investigation into historical patterns of immigrant economic activity in Manchester and Leeds found that the location of the ‘ghetto’ was within spatial reach (configurationally speaking) of the economic heart of both cities.Footnote 28 This spatial proximity allowed for multiple social identities to be asserted. While strong kinship ties were maintained within the relatively (spatially) segregated immigrant quarter, these existed in parallel to economic connections to the wider city. In some cases, people continued to live in the original place of settlement, while building up a business base in the city centre. Interestingly, Gilliland and Olson have found equivalent findings in a similar study of Jewish settlement patterns in Montreal.Footnote 29 These examples illustrate how space syntax analysis enables the historian to pursue hypotheses regarding the effects of the material organization of the urban setting on urban life through its ability to describe social data in terms of the structure of lived space, and – more specifically – to control for spatial effects when analysing social patterns using a range of archival source materials.

Even without employing detailed space syntax modelling, a ‘configurational reading’ of an historical map can take a step beyond considering urban cartography as simply illustrative of a moment in time. For example, recent work on the Hull-House maps of wage rates and country of origin for a large tract of the city of Chicago in the late nineteenth century finds that by comparing wage classes present in the main streets and the (highly dilapidated) back alleys, the historian can obtain a clear picture of the spatial juxtaposition of poverty and prosperity.Footnote 30 Adding to the analysis the spatial location of immigrant clusters – and accounting for their particular migration histories through traditional textual sources – provides the researcher with an enriched picture of the nature of immigrant settlement patterns at a crucial historical juncture. Reading urban form configurationally means decoding mapped social data to reveal the relational aspects of poverty and segregation at the scale of the street and neighbourhood, providing additional insight into the everyday life of the city.Footnote 31

Configurational analysis conceptualizes road networks as the structure of lived space

Urban space syntax analysis is fairly associated with the analysis of road networks and this can seem a rather instrumental exercise with more relevance to traffic planners than urban historians. It is important in this context to bear in mind the theoretical status of space syntax representations of road networks as just one of a family of syntactical representations of lived space – what Conroy Dalton calls ‘embodied diagrams’ that differentiates them from abstract planning models.Footnote 32 Sometimes other representations are required, even in urban-scale analyses. Vaughan et al.'s study of the streets, alleys, courtyards and buildings of London's nineteenth-century East End takes a micro-morphological look at the conditions through which a distinctive urban spatial culture emerged for its Jewish community at that time.Footnote 33 The study cross-referenced Goad plans, literary sources, the Booth study notebooks and maps, photographs, contemporaneous descriptions of local street life, minutes of the synagogue societal organization and newspaper reports. The research team developed a spatial inter-visibility analysis of the synagogues, chapels and churches in an area of Whitechapel to consider the ways in which the social-cultural relationships of Jewish inhabitants of the district were shaped by their surroundings. Space syntax analysis was also deployed to discover how the visibility of synagogues from the main street network corresponded to the socio-economic context of their immediate environs.

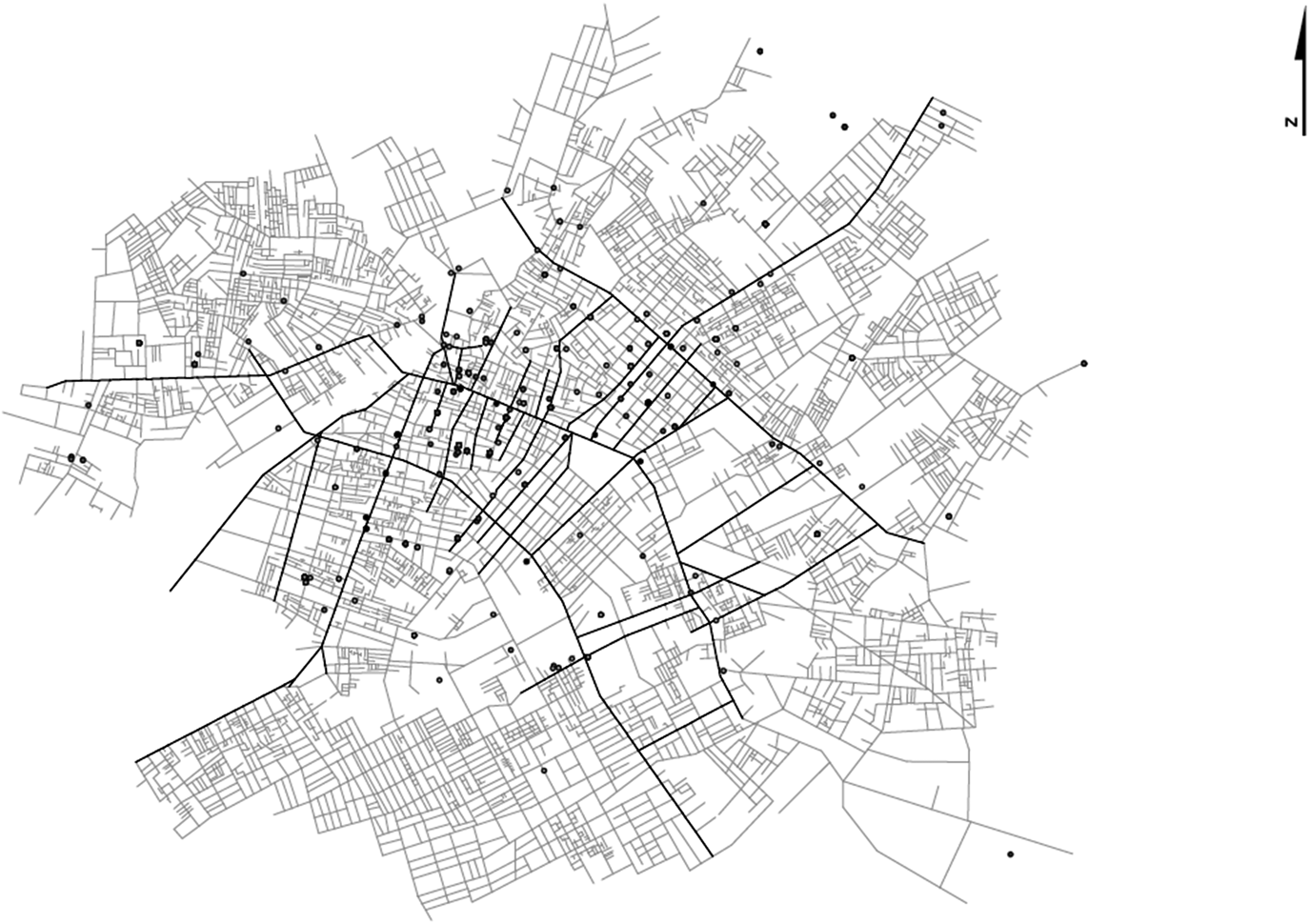

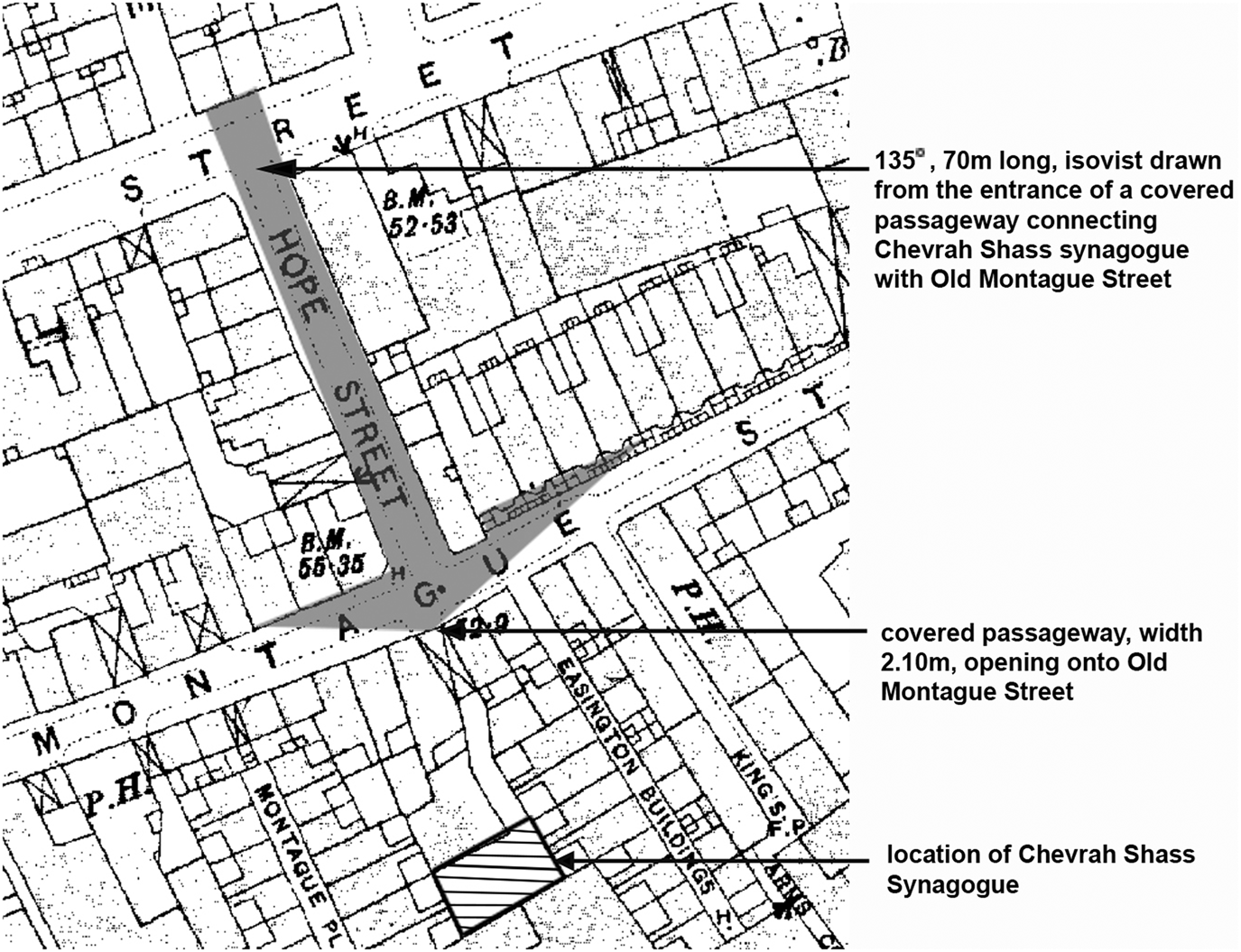

Figure 3 provides an example of this work that was developed around the elementary syntactic representation of the isovist, a method for describing the visibility relationships of urban space from particular locations on the map. Here, the method was deployed to make a numerical comparison of the visibility and socio-economic setting of 21 places of worship within the study area. This distinguished types of synagogues, churches and chapels not only on the basis of their architecture but also according to their urban embedding and intra-visibility relationships with each other.

Figure 3. Isovist of Hope Street, Whitechapel, viewed from the interface of Old Montague Street and the passageway leading to Chevrah Shass Synagogue c. 1890. Image by Laura Vaughan, Kerstin Sailer and Blerta Dino.

Morphological history helps to explain, as much as it is explained by, the social history of towns and cities

Urban space is not a timeless backdrop to social action but a relational structure through which the temporalities of morphological history and social history interweave to create enduring but complex spatial cultures.Footnote 34 Developing this theme, a series of four publications by Griffiths explore the agency of the urban encounter field as a source of routine and ritual in the everyday life of Sheffield in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Griffiths shows how, in configurational terms, Sheffield's urbanization was characterized by a series of transitions from a relatively sparse nucleated circulatory structure, to an extended area of dense spatial proximity by the mid-nineteenth century, to the emergence of strong linear structures along historical routes connecting the late nineteenth-century web of suburban centres.Footnote 35 Space syntax analysis reveals the multi-dimensional complexity of configurational descriptions that relate to the deep structure of the pre-industrial historical road network. These descriptions were then deployed in more hermeneutical mode to interpret changes in the relationship of home and work and the routes of organized processions in Sheffield, as spatial practices emergent over the nineteenth century.Footnote 36 This transition reveals a gradual symbolic privileging of urban-scale movement in a spatial culture that associated routine bodily mobility with social mobility. The study makes extensive use of archive research, particularly newspaper sources, to present a mapping of Sheffield's processional culture on to the dynamics of its quotidian spatial culture, showing how one cannot be properly understood without the other.Footnote 37 This perspective also informs an account of the rise of Sheffield's cutlery industry as a spatial culture of manufacturing, noting how many customary practices in the industry can be interpreted as means to control the easy flow of information that enabled the city to function as ‘one great factory’, despite an absence of central planning.Footnote 38 Cumulatively, these Sheffield studies suggest how space syntax methods can be used to map morphological processes of change and continuity in social spaces, enabling new interpretative possibilities for sources relating to the quotidian life of the cities to emerge.

The morphological history of the suburban built environment of Greater London from c. 1820, specifically its role in sustaining socio-economic diversity over time, was the focus of two major EPSRC research projects in the Space Syntax Laboratory.Footnote 39 Here, space syntax analysis of Greater London's suburban evolution was combined with traditional sources, principally business directory records, to test hypotheses regarding patterns of spatial continuity and change in the relationship between road network, building development and land use. It showed how the growth processes of Greater London's historical road network were related to the persistence of socio-economic activity within its local town centres.Footnote 40 By enabling diverse, localized patterns of such activity to become accessible at a range of spatial-morphological scales over time, the movement affordances of the historical road network were shown to be a key agent in the unfolding of this dynamic socio-spatial process (Figure 4).Footnote 41

Figure 4. Evolution of the street network in High Barnet (left-hand circle) and Loughton (right-hand circle). Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2014. Image by Ashley Dhanani for the Adaptable Suburbs project.

By placing the morphological history of social space in the foreground of the research methodology and examining how the material circumstances of socio-economic arrangements have changed over time, it was possible to offer a different perspective on urban processes to those reinforced by standard periodizations of social history, which tend to render the built environment as relatively static. Focusing on the micro-morphological scale of the individual suburban high street, Griffiths considers how analytical work on configurational structures and land-use patterns stimulates a consideration of the role of the built environment in perpetuating community as a ‘performance’ that normally extends beyond the life spans of the individuals who inhabit it for any given period.Footnote 42 It was argued that the high street constitutes a site for negotiating modes of historical continuity, expressed as a capacity for negotiating on-going social change in local contexts. In a similar vein, Tom Bolton's research into the evolution of railway neighbourhoods illustrates how historical investigation combines land-use mapping, space syntax and built form analysis, coupled with a thick textual description of the social and economic characteristics of the city, providing evidence of how early decisions regarding the siting of railway infrastructure can set in to long-term processes of urban formation widely characterized as being on the ‘wrong side of the tracks’.Footnote 43

From maps to mapping using space syntax

Space syntax has its origins in research undertaken at the Bartlett School of Architecture during the 1970s.Footnote 44 For its principal founders Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson, space is the existential problem that society (an intangible abstraction) must ‘overcome’ through its material (architectural) organization and the cultural codes that co-evolved to control patterns of potential co-presence, movement and encounter between different social groups.Footnote 45

Space syntax theory proposes that maps and plans are not only semiotic constructions representing the mapmaker's worldview but also diagrams that encode spatial-morphological descriptions of inhabited space as an intersubjective domain of movement and encounter. Rendered as networks and analysed as graphs using space syntax methods and software, these numeric forms of description are said to be ‘non-discursive’, as they denote complex spatial arrangements of material phenomena that can only be described quantitatively (at least in the first instance), and in that sense evade conventional linguistic definition. In space syntax theory, these spatial descriptions signify the configurational qualities of what Hillier refers to as the ‘encounter field’;Footnote 46 the complex arrangements of social interfaces regulating patterns of co-presence and interaction that he regards as the essential ‘raw material’ for social life of any kind to take place.Footnote 47 Historical research in spatial cultures focuses on articulating the spatio-morphological and socio-economic definition of the urban encounter field within a single explanatory framework.

In advocating space as a useful category of historical analysis,Footnote 48 it is important to acknowledge the concerns of most social theorists of space that to engage with formal spatial analysis is to invite the temporal and cultural decontextualization of the subject. From the mid-nineteenth century, Ordnance Survey in Britain was deploying sophisticated technologies to produce Euclidean cartographic surveys to a high degree of precision, largely for facilitating tasks of state governance. The process through which these maps were produced, however, self-evidently entailed relatively little embodiment of the urban experience itself. In this sense, official cartography indeed represents statist and capitalist power vectors – what Michel de Certeau calls the ‘strategic’ views of those in possession of power.Footnote 49 For the social anthropologist Tim Ingold, such an absolute separation between map production and the populations whose place of living and working constitute the cartographic object is both symptomatic and generative of social alienation.Footnote 50 For Ingold, the tacit assumption that the operation of ‘mapmaking’ involves an unmediated transcription from the structure of the world to the structure of the map characterizes the ‘cartographic illusion’, since in reality it is the mapmaker's world that is being represented.Footnote 51 While we acknowledge this argument, is it not equally possible that the mapmaker's operation may also translate other dimensions of social information into cartographic form (for example, pertaining to material, spatial-morphological relationships alongside those pertaining to ideological, conceptual ones)? In other words, is Ingold correct in collapsing absolutely the cartographic representation of the urban built environment into a hegemonic strategy of symbolic ordering, or does the cartographic diagram retain traces of socio-spatial formations that escape, or at least are not categorically reducible to, such an ordering process?

For Ingold, the map as a cartographic output of a scientific process is distinguished from mapping as an embodied cultural practice. Mapping in this sense involves human agents in the bodily re-enactment of movements in performative mode, whether by retracing the steps of a journey or through recounting its itinerary through speech and gesture, sometimes with the aid of inscriptive tools such as pens. Interestingly, Ingold finds equivalence between mapping as a narrative device of communal remembering in indigenous communities and the gestural act of marking a journey on a contemporary published map, with the crucial qualifier that such a marking would commonly be regarded as a defacement rather than a narrative telling. Yet such defacements have long been part of the Situationist and psychogeographer's visual repertoire, and is not running a fingernail along the streets of an intended case-study area an act of defacement that most urban historians commit? It is certainly gestural.

Ingold's argument is revealing because it suggests how the fundamental space syntax representational diagram of the urban street network – the axial map – could be considered as a defacement of the cartographic object in Ingold's sense. Unlike the itinerary of the psychogeographer, it provides an allocentric (i.e. all point to all point) network description of the urban encounter field rather than an egocentric diary of a particular route. An axial map (or graph) consists of a network or configurational model that renders urban built form as the longest and least set of lines that connect all the areas of open space (see above, Figure 1, for an example of a similar space syntax representation, the segment map, that is derived from an underlying axial model).Footnote 52 The axial map is then processed in a computer to produce a range of syntactic variables, for example measuring the relative depth of a given space within the urban system of spaces, as a starting point for exploring social phenomena such as probable levels of pedestrian activity.

Urban-scale space syntax as a mapping method begins from the axial map as a radical simplification and abstraction of the system of open space represented in the cartographic basemap. Yet before high-speed graph processing computer software became readily available, space syntax variables were calculated manually from graphs showing the connectivity of axial lines drawn onto tracing paper overlaid on the basemap (typically an Ordnance Survey map). This method necessitates a meticulous mapping process which involves sustained reflection about the structure of the cartographic representation and how it functioned as a lived space, as well as an ability to step back from the semiotic content of the basemap to the overall configuration of a settlement pattern.Footnote 53

The increasing use of road-centre line data to produce large space syntax models of contemporary cities means analogue (after Ingold we might say ‘gestural’ techniques) such as tracing by hand are now uncommon in most areas of space syntax research. The action of drawing on tracing paper over a basemap remains implicit (and, epistemologically speaking, vital), however, in admitting the degree of variability in spatial modelling that liberates syntactic representations to be developed in the context of specific historical research questions rather than simply as models applied on a one-size fits all basis. This scope for variability (for example as to the resolution at which the axial map is constructed) allows town-plan analysis using space syntax to represent the historical built environment as an encounter field in an open-ended manner, embracing the material nature of lived space without excluding the socio-economic and cultural contexts in which encounter fields emerge and are controlled.Footnote 54

Surprisingly perhaps, Hillier's emphasis on urban space as a non-determining or ‘probabilistic’ encounter field (as opposed, for example, to a 1:1 correspondence between the spatial morphology of a street layout and patterns of movement and interaction) resonates with Ingold's emphasis on the impossibility of social structure being mapped onto the material world in its own image – the source of the ‘cartographic illusion’. Hillier et al. are similarly categorical on this point.Footnote 55 They claim that spatial configuration (as, for example, represented in an axial map) offers an ‘alternative basis for encounters’ to that ‘dictated by the social structure’, it describes a complex performative field in which individualized spatial practice may become collectively communicated as meaningful social practice.Footnote 56 The axial map, in other words, represents the spatio-morphological dimension of cartographic productions that, while it certainly does not escape definition in socio-economic or cultural terms, neither is it wholly reducible to socio-economic or cultural explanation.Footnote 57

In historical research, one must, necessarily, rely on cartographic sources since the historical built environment it represents is in the past. Given this profound limitation, it is important to note how Ingold's concern that scientifically cartography collapses the openness of reality into the totality of the mapped representation has its anti-materialist counterpart in the sort of cultural reduction that translates the myriad possibilities of everyday social spaces into restatements of hegemonic cultural codes. Historical work using space syntax takes seriously the proposition that, after Lefebvre, acknowledging the sociality of space means assigning a degree of social agency to material arrangements that conform to the artifactual (that is morphological or configurational) principles that give an intelligible definition to material arrangements in time and space. This disjunction of the spatio-morphological and the cultural is reminiscent of Lefebvre's distinction between the material ‘texture’ of the lived city and text itself as constituting different kinds of hermeneutical object.Footnote 58

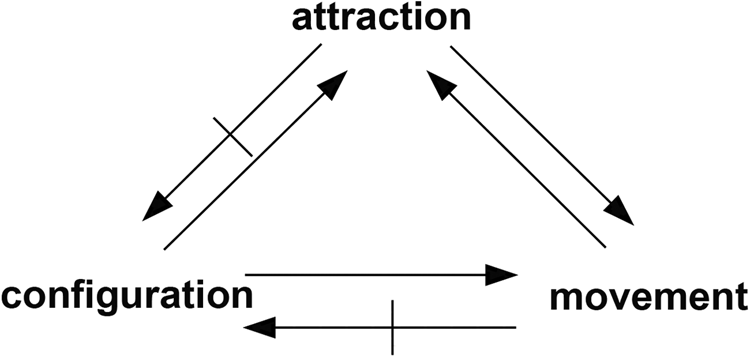

Space syntax, then, is not offered as an instrumental ‘technique’ but as a theory of socio-spatial description distinguished by its ability to make the link from relatively static material formations to social processes. A core proposition in this respect is that the encounter field described by the spatial configuration of a street network is typically anterior to the emergence of specific land-use attractors (for example, significant sites such as churches or town halls) in shaping possible patterns of movement in urban space – in other words, the configuration of the urban grid itself is the primary source of movement dynamics. The diagram in Figure 5 illustrates the space syntax theory of ‘natural movement’. It illustrates how the spatial configuration of built form generates patterns of movement and attraction in urban space. While these can influence each other, core space syntax theory starts from the premise that movement and attraction do not themselves affect configuration.Footnote 59 The theory of natural movement enables space syntax theory both to classify urban types according to the ‘social logic’ of given morphological arrangements, while also revealing space as an agent in organizing the complex patterning of social life ‘on the ground’.

Figure 5. The relationship of configuration, attraction and movement in space syntax theory. Redrawn from B. Hillier, A. Penn, J. Hanson, T. Grajewski and J. Xu, ‘Natural movement: or, configuration and attraction in urban pedestrian movement’, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 20 (1993), 31.

Ingold's theorization of mapping offers a powerful critique of the cartographic productions of modernity that is widely and legitimately endorsed by much urban historiography. An undesirable consequence of this critique, however, has been to contribute to the relegation of the epistemological status of the map for research into the material conditions and practices of everyday urban life. Asserting that modern-era cartographic surveys encode spatial-morphological as well as semiotic information is not to conflate the cartographic representation of reality with reality itself. Rather, the argument is that a map considered as a spatial-morphological description of the urban past does not neatly conform to the same map conceived as an ideological description. Spatial-morphological descriptions are defined by the relative positioning of the material objects (i.e. buildings) represented on the map, rather than their symbolic positioning in ideological landscapes described by Ingold's human subjects. It is in revealing this disjunction between material affordance and symbol that map analysis using space syntax can offer new possibilities for research in urban history.

Historiographical contexts

The marginalization of un- or mis-represented urban populations is especially relevant to the historiography of the nineteenth-century industrial city. Durkheim characterized urban modernity in terms of its physical and moral density, making an intimate connection between the form and content of social life (what he refers to as ‘social morphology’) in cities inflated by unprecedented population growth.Footnote 60 The urbanization associated with industrialization explains why Britain gave rise to the phenomenon of the social reformer as urban investigator engaged with surveying and tabulating the conditions of life in the ‘uncharted territory’ of the mushrooming industrial towns.Footnote 61 Both as physical and social environments, these places were as alien to the understanding and taste of classically educated elites as the imperial acquisitions in India and Africa were to the mass of the British population. The founder of the Salvation Army William Booth made this association explicit in comparing the slums of contemporary cities to the jungles of equatorial Africa – both were, he believed, equally godless and removed from civilization.Footnote 62 At about the same time, William Booth's contemporary, the social reformer Charles Booth, was producing his pioneering street maps that revealed to the educated British public the extreme contrasts of wealth and poverty that existed cheek by jowl in London. The development of mapping technologies and practices, by organizations as diverse as Ordnance Survey, Temperance societies, municipal boundary commissions and fire insurance companies all emerged in the broader context of the nineteenth-century reformist enthusiasm to map the ‘urban interior’. Recent urban historians have tended to interpret the nineteenth-century enthusiasm for mapping in terms of a Foucauldian push for social control. Here, mapping technologies are said to be explicitly political in enabling middle-class elites and the imperialist state to assert spatial order as a means of enforcing ideological discipline on anonymous and potentially revolutionary, urban populations.Footnote 63

From a space syntax perspective, however, the cultural framing of cartographic productions does not invalidate the value of maps as rich records of past material realities a priori, no matter how epistemologically compromised they may be. Of course, in disciplines such as archaeology, historical geography and urban morphology, a considerable amount of analytical precision has long been applied to the material culture of urban development.Footnote 64 Nor should scholarly historians write off as ‘naïve’ the priority given to maps and photographs of the built environment in local and community histories.Footnote 65 But if, as R.G. Collingwood argued, history is basically ‘humanistic’ in the sense that it is concerned with what people have done in the past and constructs its narratives on this basis, then something more is required to engage better mainstream historical studies with the kind of analytical work on built form for which maps and plans are core source materials.Footnote 66

This is especially true of research on British cities from at least the eighteenth century where the profusion of textual and visual sources available means the interdisciplinary concerns of built environment specialists may seem of marginal interest. As the urban morphologist Michael Conzen has reflected, scholars in his field of research have shown little interest in history as historians recognize it, and vice versa.Footnote 67 The result is that the conceptual link between the organization of built form (the material basis of everyday life) and what people do, think and mean (i.e. quotidian urban culture) remains under-conceptualized. As late as 2000, Colin Pooley could state that despite the theoretical strides made by Henri Lefebvre and David Harvey in explaining the social nature of space, and after decades of cartographically based research into questions such as residential segregation, the ‘extent to which changes in urban structure altered people's lives is often little more than conjecture’.Footnote 68 This situation seems unlikely to change in the face of a de facto division of labour between contradictory epistemological positions in the humanities and social sciences in which maps are viewed primarily as cultural texts or as elementary indices of physical urban transformation.

If, however, maps are not viewed exclusively through contrasting disciplinary lenses, then how might they be usefully interrogated as historical sources for a better understanding of everyday urban life, but without risking deterministic associations between the materiality of built form, what it does (functionally) and what it means (socially)? Lefebvre established that space is erroneously conceptualized as a passive container of social life.Footnote 69 Yet the principal legacy of historians adopting his line on the ‘social production’ of space has been to cast space in abstract, immaterial terms as the ideological formation of macro socio-economic processes.Footnote 70 For all Lefebvre's own emphasis on ‘spatial practice’ and ‘lived space’, his influence on social history has largely been to sustain a strongly cultural emphasis on cartography as a system of ideologically encoded ‘representations of space’, that alienates rather than, in any sense, records material reality. This epistemological difficulty has, of course, not prevented many historians from engaging with the built environment in their research into quotidian urban life.Footnote 71 One must conclude, however, that they are doing so in the absence of the conceptual and methodological tools that would both facilitate and create fresh opportunities for their research. In short, there is an epistemological need for a conceptually reflexive mode of map analysis able to express the materiality of social space without sacrificing the sociality of social space.Footnote 72

Addressing this question requires a return to the sometimes vexed question of methodology in historical studies.Footnote 73 We maintain that urban historians could find value in reconnecting with a neglected historiography in which maps and plans are approached as much for what they say about urban life, as how they frame it ideologically.Footnote 74 So far, spatial humanities as a nascent interdisciplinary domain has been, arguably, less about rediscovering maps as sources per se so much as deploying a particular technology, GIS, to give precise spatial definition to a range of historical, literary and cultural sources.Footnote 75 In its early days, HGIS could be fairly criticized as an exercise in large-scale data cataloguing, often conducted at some remove from the research interests and skill sets of practising urban historians. The epistemological ground is rapidly shifting, however, as on-going interdisciplinary engagement identifies new topics where GIS technology can be productive for historians, notably in areas of applied and public history.Footnote 76 There is still much work to do, however, in identifying at a conceptual level what HGIS enables, that goes beyond accelerating the task of putting dots on maps to offer genuinely innovative interpretative possibilities for traditional (and necessarily finite) historical source materials.Footnote 77 While HGIS undoubtedly offers a very useful platform for the spatial analysis and visualization of historical data, it does not, as a set of tools, address the conceptual problem of linking urban materiality with the sociality of space, yet this issue must lie at the heart of the debate regarding the epistemological value of developing map analysis as a serious research method for urban history.

Conclusion

Advocacy of the space syntax approach to historical mapping understandably elicits the suspicion that a set of technologically enabled techniques threatens to intervene in the vital dialogue of the historian with his or her sources. We have argued that, on the contrary, map analysis using space syntax can help advance this dialogue by re-presenting the cartographic image as an encounter field generative of spatial cultures, rather than as a physical backdrop or cultural mirror. Producing space syntax data by notionally ‘defacing’ the town plan with axial lines would be characterized by the philosopher of science Ian Hacking as the ‘creation of phenomena’.Footnote 78 Historians may be reluctant to engage with created data sources because they lack tangible presence in the archive and therefore may be regarded as inauthentic. Yet historical accounts that assume something about how space functions socially for movement and encounter, often in the absence of any firm theoretical or evidential basis for this assumption, make a strong case for engaging with the theories and methods of space syntax. Such an engagement has implications for the historian's use of language, since space syntax descriptions of urban space are quantitative and visual, leaving to the historian the job of interpreting the data in the light of other sources and contextual knowledge. This interpretative process is open-ended as configurational descriptions of space are said by Hillier to be ‘non-discursive’ in that, as numeric expressions, they lack exact referents in natural language. Indeed, it is precisely the capacity of the material organization of social space to resist absolute semantic definition that explains why it cannot be reduced to cultural representation.Footnote 79

Configurational analysis shows how spatial nouns from ‘ghetto’ and ‘slum’ to ‘street’, ‘thoroughfare’ and ‘square’ present generic linguistic categories lacking in clear historical definition. Such terms have broad resonance in the historiography of the nineteenth-century city but tend to conceal significant differences between social spaces and their socio-economical functions in relation to the wider urban context. The space syntax perspective on map analysis is useful to those who would guard against the conflation of maps as cultural productions with the lives of people who lived and worked in the urban spaces they represent.Footnote 80 It demonstrates the aptness of E.P. Thompson's response to the critique of historical research methods by Marxist social theorists that the empirical mode of historical investigation is not to be conflated with ‘empiricism’ as an ideological formation. If the formal analysis of maps and plans using space syntax can help historians to get more from these sources and access the urban past in new ways, then this is surely sufficient justification for advocating their use in historical research – it does not diminish the task of proper contextualization and interpretation.Footnote 81

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963926820000206.