German Opera in Courtly and Urban Theaters in Vienna: From the National Singspiel (1778) to Die Zauberflöte (1791)

“Vienna has its share of all the genres: French comedy, Italian comedy, Italian opera, the grand Noverre ballets, German opera, and the like,” writes Johann Pezzl in the first volume of his famous Skizze von Wien (1786).1 German opera in Mozart’s Vienna interacted with many other theatrical genres in what was widely celebrated as a rich cosmopolitan European center.2 This is not to say that the genre did not have its own distinctive musico-dramatic features and theatrical history. Vienna boasts a rich and varied German-language theatrical tradition dating back at least to the late seventeenth century, including Jesuit drama, improvised comedy in folk theaters, often interspersed with song, and musical theater performed by traveling troupes. One of the formative moments for eighteenth-century German opera was Joseph II’s 1776 announcement of the opening of the German National Theater, a spoken theatrical enterprise, which performed in one of the two court theaters, the Burgtheater, renamed the Nationaltheater. Two years later, its operatic counterpart, the German National Singspiel, was inaugurated in the same space with a new work, Die Bergknappen (The Miners), composed by the company’s first music director, Ignaz Umlauf. Featuring accomplished singers such as Caterina Cavalieri (who would later create the role of Konstanze in Mozart’s 1782 opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail [The Abduction from the Seraglio]), this court-operated company produced a number of successful works. Prominent examples include Umlauf’s Die Apotheke (The Apothecary, 1778), Die schöne Schüsterin (The Beautiful Cobbler, 1779), and Das Irrlicht (The Will-o’-the-Wisp, 1782); Franz Aspelmayr’s Die Kinder der Natur (The Children of Nature, 1778); and Salieri’s Der Rauchfangkehrer (The Chimney Sweep, 1781).

Home of the National Singspiel company, the Burgtheater was regarded as one of the finest theatrical spaces in Europe. Contemporary book and art collector Georg Friedrich Brandes, in a description from 1786, distinguishes it from Parisian theaters by its size and lighting:

It does not have a beautiful form, but it is fine, decorated in white with gold, and the fourth balcony undoubtedly much larger than those [theaters] in Paris. The lighting is also superior here. In Parisian theaters a crown hangs, which nearly fully blinds the audience members in the balconies. In Vienna two lights are installed for two balconies, through which the unpleasantness is much more dispersed, and the amphitheater is better illuminated.3

Lighting was costly and the Burgtheater’s luxury is revealed through its illumination, where candlelight glistened against the gold and white interior. Brandes emphasizes the opulence of the Viennese court, explaining that “the court here pays for everything, and has the income to do so.”4 During this initial period of the German National Singspiel, the genre was well supported and composers were provided with sufficient resources to create a distinctive German-language operatic repertory. Crucially, Joseph II was not interested in establishing a Singspiel troupe in the manner of earlier North German traditions – most notably that of Johann Adam Hiller – in which the performers were actors first, singers second. While a simple folk-like style certainly appears in late eighteenth-century Viennese Singspiel, efforts were made to recruit top singers for the National Singspiel enterprise, and a fine orchestra of at least thirty-five players was established, including strings, flutes, oboes, bassoons, horns, and, by 1782, trumpets and a kettledrum player.5 As a result, the musical writing for Viennese Singspiel from 1778 onwards does not shy away from featuring virtuosic singing and lavish orchestral timbres to paint particular scenes or situations.

Though initially successful, the German troupe at the Burgtheater proved difficult to sustain. It was disbanded in 1783 and replaced by a company that produced Italian opera buffa, one of the more popular and financially sustainable repertories. When a German company was reinstated in 1785, Emperor Joseph II issued a decree that withdrew performing privileges for all other troupes at the second royal theater, the Kärntnertortheater,6 making it the new home for the German company, a practice which lasted until 1788. In 1787 Pezzl offered the following explanation for the reinstatement of the German company: “Since a large part of the public does not understand Italian, and one wishes to also entertain them with Singspiele, a German opera is established at the same time, which performs primarily at the Kärntnertortheater.”7 The new troupe included singers such as Caterina Cavalieri and Aloysia Lange, and this period witnessed the production of Singspiele such as Franz Teyber’s Die Dorfdeputierten (1785), Mozart’s Der Schauspieldirektor (1786), Umlauf’s Die glücklichen Jäger (1786), and Dittersdorf’s Doktor und Apotheker (1786), among other works.

German opera in late eighteenth-century Vienna was not limited to the two royal theaters. Alongside the opening of the German National Theater in 1776, Joseph II also declared Spektakelfreiheit, literally meaning “freedom of spectacle,” which allowed new permanent private theaters to operate commercially. Three suburban theaters opened within a decade: the Theater in der Leopoldstadt, which was established in 1781 by Karl Marinelli; the Theater auf der Wieden, which opened in 1787 and was under the direction of Emanuel Schikaneder by 1788; and the Theater in der Josephstadt, which opened in 1788 and was run by Karl Mayer. Even with this Spektakelfreiheit, theater in Vienna was heavily censored at both the court and suburban theaters.8 Each suburban theater specialized with respect to repertory. Marinelli’s Theater in der Leopoldstadt was best known for its popular comedy in the Hanswurst tradition – popular entertainment, often improvised comedy, featuring the comic figure of “Hans Sausage.” Though of older origins, this type of entertainment had distinctly Viennese roots, which could be traced back to Hanswurst roles created by Josef Anton Stranitzky earlier in the century.9 Undoubtedly the most famous theatrical fixture of this type in Mozart’s day was the comic character Kaspar, who is described here by a contemporary:

But who, then, is Kaspar? He is the comedian at Marinelli’s theater in Leopoldstadt. I might almost say [he is] an original genius, the only one of his kind. He knows the public’s taste; with his gestures, face-pulling, and his off-the-cuff jokes he so electrifies the hands of the high nobility in the boxes, the civil servants and citizens on the second balcony, and the masses crammed together on the third floor that there is no end to the clapping.10

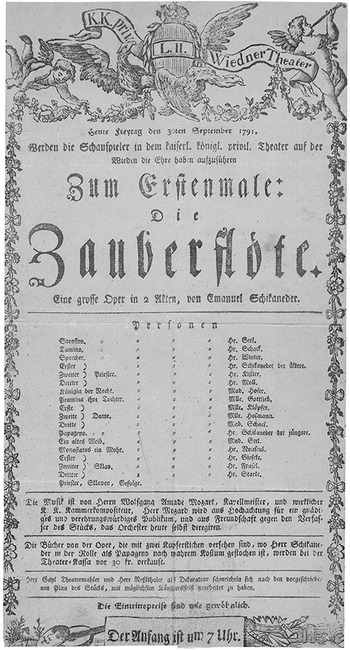

The actor playing Kaspar was Johann La Roche, and he appeared in many spoken plays and German operas, perhaps most famously as Pizichi in Wenzel Müller’s Kaspar der Fagottist (1791). Like Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte, this Singspiel finds its roots in August Jacob Liebeskind’s fairytale “Lulu, oder Die Zauberflöte” (1789). Emanuel Schikaneder’s Theater auf der Wieden (renamed the Theater an der Wien after a renovation in 1801) specialized in magic opera (Zauberoper) and machine theater (Maschinentheater). The space was outfitted with state-of-the-art technology and might well have been the only theater that could have accommodated The Magic Flute’s elaborate stage transformations.11 Finally, the Theater in der Josephstadt was perhaps less important for German opera at the time of Mozart but gained importance in the nineteenth century. German opera in Mozart’s Vienna thus traversed various theatrical venues, where it interacted with a wide range of theatrical genres, including French and Italian opera performed in translation, spoken theater, ballet, machine theater, and melodrama. This chapter offers an overview of German opera in Mozart’s Vienna by considering moments in three seminal works: Ignaz Umlauf’s Die Bergknappen (1778), which opened Joseph II’s National Theater; Wranitzky’s Oberon, a magic opera performed at the Theater auf der Wieden in 1789; and, finally, Wenzel Müller’s Kaspar der Fagottist, performed at the Theater in der Leopoldstadt in 1791.

Joseph II’s Sonic Jewel at the Nationaltheater: Ignaz Umlauf’s Die Bergknappen (1778)

Mining featured prominently in Enlightenment scientific, cultural, and political ideals. It served, as Jakob Vogel illustrates, to showcase the economic development of individual states and territories, embodied in “patriotic visions” of mineral collections open to the public.12 It is no surprise, then, that the Singspiel Paul Weidmann and Ignaz Umlauf created to inaugurate Joseph II’s German National Singspiel was Die Bergknappen (The Miners). Mining was not merely a regional enterprise that would add local color to an operatic work but a matter of patriotic pride. The Hapsburg Empire competed with other European states to expand its royal mineralogical collections and knowledge, and riches particular to geographic regions were fervently excavated and displayed. The premiere of Die Bergknappen on February 17, 1778, put Viennese Singspiel, like its prized geological stones, on the map of cultural activities in Europe. Musically diverging from previous German Singspiele sung by actors in traveling troupes, the royal company invested in star singers and secured a top-quality orchestra to ensure the venture’s success. The libretto lists the four soloists alongside their dramatic roles: Walcher, a mining officer, played by Hr. Fux; Sophie (his ward), played by Mlle Caterina Cavalieri; Fritz, a young miner, played by Hr. Ruprecht; and Zelda, a gypsy, played by Madam Stierle.13 The main plot concerns the young lovers, Sophie and Fritz, whose union is initially prevented by the older Walcher, who intends to marry Sophie himself. After the lovers thwart Walcher’s rendezvous with Sophie, he ties her to a tree, where the gypsy Zelda takes her place at night. Walcher is terrified at what he believes is an evil transformation, and Zelda reveals to Walcher that Sophie is his daughter. When the miners return to work the following morning, singing about retrieving gold for the state, Fritz warns Walcher of a dream in which the mineshaft collapses, but is ignored. The earth trembles, and Fritz’s vision comes true. He bravely enters the mineshaft to save Walcher, who is trapped below, and following a safe return, Walcher blesses Fritz and Sophie’s union.

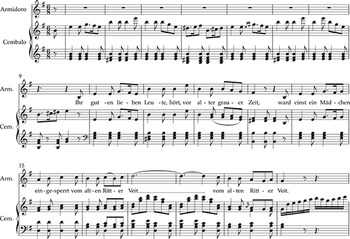

One of the most striking musical forms in Viennese Singspiel is a highly virtuosic coloratura aria sung by the lead female character. In the first years of the National Singspiel, these roles were sung by Caterina Cavalieri and included Sophie in Die Bergknappen, Nannette in Die Apotheke, and, perhaps most famously, Konstanze in Die Entführung aus dem Serail. This aria represents a significant departure from earlier Singspiele, in which virtuous female characters sang simple folk-like tunes to reveal their purity; such arias distinguished these heroines from noble characters singing in a virtuosic style that exemplified the artificiality and excessive luxury of court life. Typically set in a natural realm and often compared to birdsong, this coloratura aria type employs one or two obbligato instruments with which the voice interacts, resembling an instrumental concerto.14 In a previous scene, Walcher has punished young Sophie by tying her to a tree for the night. An engraving of the scene shows Walcher shining a light on Sophie from a second-story window, enhancing the picturesque effect of the dark scene (Figure 1.1). Sophie’s isolation in the garden at night, captured in the image, contributes to the sheer theatrical effect of two arias sung in the garden. The second of these is the coloratura aria “Wenn mir den Himmel.” It features a lengthy orchestral introduction with oboe solo, effectively halting the plot and drawing all attention to Cavalieri’s agile voice. The oboe opens with what seems at first to be a simple melodic phrase in C major. Yet when the opening figure is repeated, it is transformed into a virtuosic scalar passage, displaying the technical prowess of the performer. Sophie enters with the same melody and her coloratura passages are immediately echoed by the obbligato oboe, fusing into a double display of sonic artistry (Example 1.1a).15 This bravura passagework draws to a close in the orchestra in the manner of an instrumental concerto, though the aria is not over. The audience is treated to another virtuosic display of dexterity as the second section commences with a repeat of the opening theme. The second installment is even more spectacular than the first, as the voice and oboe intermingle, sometimes passing scalar passages back and forth, and sometimes executing sixteenth-note passages a third apart (Example 1.1b). Sophie sings of the heavens granting her new life, and, in the manner of an instrumental concerto, this second section is brought to a close by a fermata on the dominant, indicating free vocal embellishment, followed by closing material in the tonic by the entire orchestra. Her heartfelt plea seems to have been heard – she is set free and Zelda takes her place tied up against the tree.

Figure 1.1 Scene from Die Bergknappen showing Caterina Cavalieri as Sophie. Ink drawing by Carl Schütz, 1778.

Example 1.1a Umlauf, Die Bergknappen, Sophie’s aria “Wenn mir den Himmel,” mm. 29–46.

Example 1.1b Umlauf, Die Bergknappen, Sophie’s aria “Wenn mir den Himmel,” mm. 64–78.

Whereas an aria such as Sophie’s emphasizes the importance of star singers in Viennese Singspiel, the scene in which the mine shaft collapses underscores the role of the orchestra. At first glance, one might surmise that Umlauf employs various instruments to paint natural phenomena, thereby creating a sonic play-by-play of the event. Yet a closer examination, coupled with aesthetic documents on musical painting, reveals an alternate approach. Orchestral timbre is used in conjunction with descriptions by Fritz and members of the chorus of miners. This enables the audience to experience the disaster from various human perspectives. In other words, the orchestra does not merely paint nature, it paints how humans experience natural phenomena. This aesthetic is in keeping with contemporary writings such as Johann Jakob Engel’s “On Painting in Music” (1780).16 The opening of the accompanied recitative “Die Erde bebt” (The earth shakes) features fast repeated notes on the strings, which paint the shaking ground (Example 1.2).

Example 1.2 Umlauf, Die Bergknappen, Fritz and the miners’ recitative “Die Erde bebt,” mm. 6–17.

Once the chorus of miners alerts Fritz (and the audience) that Walcher is trapped, the texture shifts to slower unison writing; Fritz comments on his decision to risk his life to save his rival. As he descends, the orchestral writing features rapid scalar passages culminating in a tremolando effect; here, two chorus members sing, “Consider the danger, how we trembled.” In other words, the audience is being asked to put themselves in the miners’ shoes, and Umlauf’s orchestral writing assists with this process of identification. It is no coincidence that we also hear from Sophie in an accompanied recitative, “Ein klägliches Geschrei klingt in mein Ohr” (Example 1.3). The oboe solo paints her anxiety as she awaits the outcome of her lover’s brave rescue mission. The orchestral writing changes to rapidly repeated thirty-second notes as she describes her shaking limbs. Here, as in the earlier scene with the miners, we are privy to Sophie’s physiological responses, which are painted by the orchestra; there is little sonic rendition of the natural disaster.

Example 1.3 Umlauf, Die Bergknappen, Sophie’s recitative “Ein klägliches Geschrei klingt in mein Ohr,” mm. 1–15.

Joseph II’s decision to secure both highly trained singers and orchestral players for the National Singspiel enabled composers such as Umlauf to produce first-rate operatic works in the German language. While many authors have emphasized the Singspiel’s apparent reliance on genres such as French opéra comique and Italian opera buffa, a closer examination of this little-known German repertory suggests a more complex situation. Viennese Singspiel engaged with other genres while at the same time rapidly striving to forge its own distinct musico-dramatic forms and conventions. The establishment of this institution served an important purpose: it made the production of German opera a matter of national urgency. The ability to hire star singers such as Caterina Cavalieri allowed for the creation of highly virtuosic concerto-like arias, which featured prominently in Viennese Singspiel for several decades. Joseph II’s National Singspiel project may not have lasted very long, but it created an impetus for, and influenced, a German operatic repertory that would flourish in urban theaters across Vienna.

Magic Opera at the Theater auf der Wieden: Wranitzky’s Oberon (1789)

Of the three main suburban commercial theaters in Mozart’s Vienna, Schikaneder’s Theater auf der Wieden exhibited the strongest predilection for theatrical works that incorporated magical themes, often featuring elaborate stage machines.17 One of the most popular fairytale Singspiele prior to Die Zauberflöte was written by composer Paul Wranitzky and librettist Karl Ludwig Giesecke. Oberon, König der Elfen premiered on November 7, 1789, and the work was quickly disseminated across the German-speaking realm, with performances in Frankfurt am Main in 1790, Mainz in 1791, Berlin and Augsburg in 1792, and Lemberg, Buda, and Pest in 1794; it spread to Linz, Krakow, Prague, Bratislava, Warsaw, and Hamburg during the mid-1790s.18 Its popular appeal can be attributed not only to its spectacular visual effects but also to various musico-dramatic features, which may be familiar to admirers of Mozart’s last opera.

Hüon, a German knight, is sent by King Charlemagne to rescue the Sultan of Bagdad’s daughter, Amande. Because the reunion of the fairy king and queen depends on the fidelity of Hüon and Amande, Oberon and Titania are keen to assist in the mission. Together with his father’s squire, Scherasmin, Hüon successfully navigates a forest and is guided by Oberon’s two genies in his search for Amande. The lovers escape Bagdad on a ship, but a strong storm renders them unexpectedly shipwrecked in Tunisia, where they become captives of Sultan Alamansor and his wife Alamansaris. Despite attempts by the Tunisian rulers to seduce Hüon and Amande, the two remain faithful even in the face of death. Oberon arrives just in time to save the pair, who have withstood all their trails, and Hüon and Amande are freed.

While it is tempting to focus exclusively on musical forms and devices, it is worth keeping in mind that Singspiel is an operatic genre that intersperses extended spoken dialogue with song. The dialogue between characters is therefore an essential component of generic analysis. And, as we shall see, theories of comedy in German opera are distinct from its Italian and French counterparts, and these differences often come to the foreground when the spoken dialogue is considered. The opening scene features the serendipitous encounter between Hüon and the comic character Scherasmin: the German knight finds himself lost in a forest, while the local has gathered a bundle of wood and is wearing “wild attire.”

(While Scherasmin wants to leave, Hüon holds him back from behind.)

Hüon Stop!

Scherasmin (falls to the ground) Oh, oh! Wrathful Mr. Death! I called you only because my bundle of wood became too heavy, so that you can help me carry it.

Hüon Simple-minded person!

Scherasmin Pardon me for my naïveté. Let me regale on roots and herbs for another five years, maybe I’ll improve by then.

Hüon Stupid, who wants to harm you! Just look at me, I am a human being, like you.

Scherasmin (remaining turned away from him) Someone else might believe you. I know very well that you disguise yourself every day with a different garment from your wardrobe.

Hüon Not true. I am an unfortunate one who has got lost here. Show me the way out of this forest and I will show you my gratitude.

Scherasmin (straightens up) Well, I will take a risk on your gratitude. But if you take me, poor devil, for a ride, then I’ll cry out and woe to you.19

This comic encounter between the young knight and the Rousseauian natural man, soon to become his companion on a mission, is designed to amplify the differences in cultivation, social class, and kinds of knowledge. Scherasmin, for instance, has gained sufficient natural knowledge to survive in this hostile environment, whereas Hüon is very much in need of assistance. The two men also recognize their common humanity, and, implicitly, the scene drives home Enlightenment ideals of human equality and freedom. As the conversation unfolds, Scherasmin (and the audience) learns that Hüon is of noble descent and that he is on an impossible mission to travel to Bagdad, where he is to collect a handful of hair from the Sultan’s beard, retrieve four of his back teeth, and take his daughter as a bride. Hüon discovers that Scherasmin used to serve his (now deceased) father and has been living in a cave in the forest for some fifteen years. Upon learning of the brave knight’s mission, Scherasmin vows to serve him. This outcome alone is a paradigmatic example of typical interactions between working and noble classes in German opera.

Whereas Italian opera buffa revels in servants “uncrowning the King,”20 often through feats of deceit, comedy in late eighteenth-century Singspiel is often generated by bringing together the most unexpected characters from vastly different social classes and backgrounds. These “unexpected encounters,” such as the one between Hüon and Scherasmin (as well as Tamino and Papageno), showcase both noble and lower-class everyday life experiences and perspectives. More often than not, they feature productive collaboration between social classes. Put another way, comic lower-class characters in Singspiel often assist, rather than derail, noble characters in achieving their missions. It is well worth noting that Singspiel performers such as Emanuel Schikaneder were superb actors, whose comic gestures especially for characters such as Scherasmin and Papageno kept audiences returning to theaters.21 In effect, the performative and comic dimensions of Singspiel came alive in the spoken dialogue, and they were reinforced by gesture, perhaps signaling the genre’s debt to the heritage of the Hanswurst.

Comic Antics and Folklike Music: Kaspar der Fagottist (1791) at the Theater in der Leopoldstadt

“One is now hungry for spectacular pieces [Specktakelstücken] … and, as such, this Magic Zither was taken up in Vienna and Prague, and was performed numerous times,” an anonymous editor writes in the 1794 preface to librettist Joachim Perinet and composer Wenzel Müller’s Kaspar der Fagottist, oder Die Zauberzither (1791).22 Marinelli’s aforementioned Kaspar figure appears as a comic sidekick named Kaspar Bita, accompanying Prince Armidoro on a mission to rescue Princess Sidi. Daughter of the radiant star-queen Perifirime, the beautiful Sidi is held captive by an evil sorcerer, Bosphoro. Following their initial encounter in an enchanted forest, Perifirime endows Prince Armidoro with a magic ring and zither, and Bita with an enchanted bassoon, to ensure the success of their mission. While the opera certainly features magical sounds and visual spectacle, including a balloon ride toward the end of the opera, the comic character Bita is undoubtedly one of its main attractions. From his comic encounters with Perifirime – when, for example, he asks if he may drown in her wine cellar if he must die – to lighthearted songs celebrating women and wine, Bita’s comic episodes are accentuated by the sound of a bassoon. Like Papageno in The Magic Flute, he needs nothing more than bread, wine, and a woman to love, and is easily scared by the sudden, spectacular transformations prevalent in magic operas. For instance, on one occasion, as he and Prince Armidoro approach Bosphoro’s castle high on a cliff, the prince turns a magic ring, thunder and lightning ensue, and the prince disappears. Terrified, Bita runs for cover, turns motionless, and then runs to the back of the stage, only to dash back out as flames emerge from the earth. As it happens, the prince has transformed himself into a little old grey man, and Bita recognizes him only by his voice.

Once the pair meet Bosphoro, Armidoro demonstrates his musical talents with the magic zither and, eventually, sings “Es hielt in seinem Felsennest,” a Romanze (a well-known song type in German opera), in the presence of Princess Sidi. This strophic song form sums up the moral of the story. While it is self-reflexive – it presents the crux of the tale at hand – it is performed within the diegesis of the opera as though it had nothing to do with the plot and is typically set in the distant past. In this instance, Armidoro sings the ancient tale of a young girl held captive in a castle tower high on a rocky cliff. A young knight passes by, hears her screaming, and promises to return at midnight to free her. That night at twelve o’clock the knight returns, throws up a rope for the girl to descend, and the story ends with a romantic kiss. Musically, the Romanze features a lilting melody in 6/8, typically beginning in the minor mode, with a turn to the major for the middle portion of the song (Example 1.4 shows the opening of the aria in a contemporary vocal score with an altered verse of unknown origin).23 First appearing in mid-eighteenth-century French comic opera, the Romanze frequently appears in North- and South-German Singspiel, often telling the tale of a young woman being rescued from captivity. The simple, repeatable, songlike quality of this form fueled its popularity, and these tunes were disseminated well beyond theaters as folksongs and circulated in popular piano-vocal scores.24 Armidoro’s performance is followed by Bita teaching Princess Sidi to dance, and naturally in Vienna she would be taught a waltz. Self-reflexive commentary ensues as Bita sings that “a waltz is in keeping with German ways” (“ein Waltz ist so nach deutscher Art”) in his Act 2 song “Ein Walzer erhitzet den Kopf und das Blut,” thereby celebrating German musical and cultural identity.

Example 1.4 Müller, Kaspar der Fagottist, Armidoro’s Romanze “Es hielt in seinem Felsennest,” mm. 1–20 (from a contemporary vocal score with altered text).

The popular folklike quality of Viennese Singspiel was not limited to solo numbers. Choruses, especially men’s choruses, feature prominently in the genre and are often sung by groups of individuals easily recognizable in society. Whereas Umlauf’s Die Bergknappen features a chorus of miners, Die Zauberzither showcases a group of hunters at the opening of the opera. Their presence is announced with hunting horns – a sound typically limited to the nobility in Italian opera – now appropriated by the bourgeoisie to showcase everyday German life. The opening chorus “Hau hau hau, auf Jäger seyd wach,” featuring the echoing sound of working men singing in the forest, presents an idealized image of working-class German citizens contributing to society through manual labor, including mining, forestry, and hunting. Initially populating eighteenth-century Singspiel, these character groups would continue to appear in operas such as Carl Maria von Weber’s Der Freischütz and in nineteenth-century German lieder.

Conclusion

Joseph II’s inauguration of the National Singspiel in 1778 provided an impetus for the production of high-quality German-language opera that would rival its French and Italian counterparts. German opera in the decade leading up to The Magic Flute (1791) was forged in a transnational context and featured a rich array of musico-dramatic forms that we encounter in Mozart’s last opera. Lavish orchestral writing, especially for scenes of heightened emotion, and concert-like virtuosic arias for the female heroine in Umlauf’s Die Bergknappen, set the stage for Mozart’s deployment of the orchestra and the Queen of the Night’s arias. Spoken dialogue inspired by German comedic practices featuring encounters between lower-class comic characters and princes enrich our understanding of Papageno and Tamino’s first exchange. The comic features of Kaspar, along with the memorable, folklike singing style, made Papageno a familiar and beloved figure. These musico-dramatic forms and features, well established in the decade leading up to The Magic Flute, clearly resonated with the public. They likely also contributed to the opera’s enduring success and can bring new insights for our enjoyment of Mozart’s last opera even today.

Most of the operas Mozart produced in Vienna in the last decade of his life, including The Abduction from the Seraglio, The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Così fan tutte, were premiered at the Burgtheater, the imperial court theater in the city center. The Magic Flute, by contrast, was produced at the Wiednertheater (also known as the Theater auf der Wieden), a private and commercial institution in the Viennese suburbs. The author of The Magic Flute’s libretto, Emanuel Schikaneder, was not only the Wiednertheater’s director, but also one of its greatest stars, as epitomized by the role of Papageno, which he created specifically for himself. Schikaneder became the director of the Wiednertheater in 1789, when he was approached by his ex-wife Eleonore Schikaneder after the death of Johann Friedel, her codirector and the Wiednertheater’s founder. Prior to his directorship at the Wiednertheater, Schikaneder led several theater troupes in Southern Germany and Austria, including in Augsburg, Regensburg, and at Vienna’s Kärntnertortheater. The Magic Flute’s libretto, therefore, reflects Schikaneder’s experience both with the German theater repertoire presented by regional theater companies in the 1770s and 1780s and with the conventions of the repertoire presented on Viennese commercial suburban stages around 1790. At the same time, the libretto reveals Mozart’s own sensibilities with respect to German-language theater and his wide-ranging experience with opera at the Vienna court theater.

To what extent Mozart himself may have contributed to the opera’s libretto is not entirely clear. What makes the search for Mozart’s textual contributions particularly problematic is how little is known about the libretto’s inception. In an effort to clarify the enormous richness of subjects and themes in The Magic Flute, many previous studies have explored literary and theatrical works that critics and scholars believe influenced the conception and construction of the libretto. Emphasis has also been placed on Mozart’s and Schikaneder’s personal involvement with Masonry and with the contemporaneous repertoire of the Viennese suburban theaters. A substantial literature attempts to identify the sources from which many specific elements in the libretto derive. At the same time, The Magic Flute appears distinct and original, in ways that emerge from its libretto, when compared to many of the works produced by court and commercial theaters of the period.

This essay focuses on The Magic Flute’s links to theatrical aesthetics of the Vienna court theater, as well as debates surrounding late eighteenth-century calls for the establishment of a German national theater tradition, and suggests that Schikaneder’s and Mozart’s experiences with the world of late eighteenth-century German theater traditions shaped The Magic Flute’s libretto significantly. At the end, I will attempt to show that Mozart’s contributions to Schikaneder’s libretto in fact enhance the work’s status as both a culmination of decades-long debates about German national theater and a harbinger of a future course for German national opera.1

German National Theater Reform

The Magic Flute’s libretto reflects numerous ideas that German theorists had been debating since the 1730s in connection with a reform of the national theater. Among the many contexts for understanding the libretto, this may be one of the most important. Mid-eighteenth-century German aestheticians, such as Johann Christoph Gottsched, wanted to raise German theater to the level of the theatrical traditions of other countries, especially France and Italy. To achieve this end, German playwrights focused on works that were fully written out (as opposed to partially improvised), adhered to the principles of French neoclassical drama (such as the Aristotelian unities), and were both morally upright and didactic. One of the goals of the German reformers was to gain financial backing from German states and principalities in order to make German works more competitive with Italian and French operas and dramas, which represented the main fare at most German court theaters in the early 1700s. Through a repertoire of didactic national works, German intellectuals wanted both to transform German audiences into cultivated and well-behaved subjects and to express emerging notions of German national uniqueness (or moral superiority).2

Schikaneder and Mozart were both well versed in this tradition. Prior to taking over the directorship of the Wiednertheater in the fall of 1789, Schikaneder had directed German theater companies in various cities that produced elevated German dramas, including works by Goethe and Lessing. Schikaneder’s own spoken and musical dramas also subscribed to reformist viewpoints.3 Mozart, too, participated in this cultural movement and famously expressed support for German national opera in his letter of February 5, 1783, to Leopold Mozart: “Every nation has its own opera and why not Germany? Is not German as singable as French and English? Is it not more so than Russian?”4 Several of the works that scholars cite as important sources for The Magic Flute’s libretto in fact originated within the tradition of German reform drama. Most prominent among these is Tobias Philipp von Gebler’s play Thamos, König in Ägypten (Thamos, King of Egypt), which premiered at the Vienna court theater (the Burgtheater) in April 1774. Like The Magic Flute, this play involves a conflict between a benevolent high priest/king (Sethos, a deposed Egyptian king) and a power-hungry, manipulative, and cruel priestess (Mirza), who stabs herself when she realizes her evil plan to help her nephew (Pheron) usurp the throne of Egypt has failed. Thamos certainly belongs to the tradition of German reform drama because of its elevated plot and didactic ending (the evil characters die, the virtuous ones are rewarded, and righteous behavior is exalted and commented upon throughout the play).

For Gebler’s play, Mozart wrote three choruses and five instrumental numbers (four interludes and one postlude). Early versions of two of Mozart’s three choruses were performed as part of the first production of Gebler’s play at the Vienna Burgtheater in 1774.5 Mozart revised these two choruses, added a third one, and wrote the instrumental music sometime between 1775 and 1780.6 Unfortunately, we do not know for certain for which performance this additional incidental music was intended. The similarity between Thamos and The Magic Flute led early twentieth-century Schikaneder biographer Egon Komorzynski to speculate that Mozart revised and expanded the Thamos music for a production by Schikaneder’s itinerant troupe, which performed in Salzburg between September 17, 1780 and February 27, 1781.7 Since there is no record of a Schikaneder production of Thamos in Salzburg, however, later scholars connected Mozart’s revision to the documented Salzburg performance of the play with an unspecified composer’s music by Karl Wahr’s company on January 3, 1776.8 Whether it was performed by Schikaneder’s or Wahr’s company, Mozart’s Thamos music does illustrate the composer’s exposure to and artistic interactions with German reform drama in the 1770s. We know from a letter to his father of February 15, 1783, that Mozart thought well of this work and was disappointed when the national company in Vienna refused to perform Gebler’s Thamos, and thus his choruses and interludes.9

Although Thamos quickly disappeared from German stages, Mozart’s choruses and interludes were eventually repurposed for Karl Martin Plümicke’s Lanassa, another reform German drama. Lanassa was performed throughout the 1780s by the troupe of Johann Böhm, including during Mozart’s visit to Salzburg in September and October 1783.10 According to a poster dating from September 17, 1790, Böhm’s troupe performed Lanassa with Mozart’s choruses and interludes in Frankfurt, and Mozart may have attended a performance during his visit to the city for the coronation of Leopold II.11 Like many German dramas of the 1770s and 1780s, Lanassa contains elements that clearly prefigure The Magic Flute: The exotic plot takes places in an unspecified Indian port and is filled with depictions of religious rites; the drama’s main theme is the criticism of religious fanaticism and human sacrifice (the main heroine’s much older husband dies and she is supposed to be burnt alive on his funeral pyre). The most prominent connection to The Magic Flute is the claim of the main hero, General Montalban, that he is no conqueror but simply a human (“Kein Überwinder bin ich, ich bin ein Mensch”), which prefigures the Speaker’s and Sarastro’s statements that Tamino is not just a prince but a human (Speaker: “Er ist Prinz.” Sarastro: “Noch mehr – er ist Mensch!”).12

In Vienna, the most powerful endorsement of the reformist movement occurred in 1776, when Emperor Joseph II transformed the court theater into a National Theater devoted solely to presenting German spoken plays; the German opera troupe, or National Singspiel, was added in 1778. Shortly after his move to Vienna, Mozart became involved with the National Singspiel, for which he composed The Abduction from the Seraglio, which premiered in 1782. In two famous letters to his father dating from the fall of 1781, Mozart provides numerous details about his working relationship with Viennese playwright Gottlieb Stephanie the Younger on The Abduction’s libretto. For example, Mozart asked Stephanie to reorder the musical numbers and rework the plot, which led to the creation of a new, moralistic finale at the end of the second act.13 It is possible (likely, even) that Mozart was similarly involved in the inception and development of The Magic Flute’s libretto. The libretto of The Abduction in many ways prefigures that of The Magic Flute, particularly in its reformist intensity (the opera presents exemplary actions that are explicitly promoted by text and music) and its variety of styles (a libretto that combines simple, strophic songs with more complex arias; a quartet resembling an Italian comic opera finale; and a vaudeville conclusion akin to those in contemporary French opéra comique).14

After Joseph II decided to replace the National Singspiel with an Italian opera company in 1783, German opera in Vienna moved into the hands of private entrepreneurs. Remnants of the reformist attitude toward opera was at times rekindled at the state-supervised Kärntnertortheater, which was rented out to private theater companies and for a brief period (1785–88) accommodated a variant of the court-supported National Singspiel.15 At the request of Joseph II, Schikaneder became one of the temporary tenants at the Kärntnertortheater between November 5, 1784 and January 6, 1785, and during his brief stay in Vienna his company featured numerous German operatic works originally introduced by the National Singspiel. He even opened his brief Viennese stagione with The Abduction.16 Before returning to Vienna in 1789, Schikaneder traveled through various parts of Southern Germany, and his longest director position was in Regensburg (between February 1787 and August 1789), where he featured both The Abduction and Lanassa.17 German reform drama therefore represents a crucial context for Schikaneder’s and Mozart’s work on the libretto for The Magic Flute.

Fairy-Tale Operas in the Viennese Suburbs

In creating the libretto for The Magic Flute, Schikaneder also drew from a number of magical, fairy-tale operas that were particularly popular with the Viennese public. Such works were already prominent in the repertoire of the National Singspiel and its Kärntnertortheater variant. Among the most popular ones were the Viennese German adaptation of André Grétry’s Zemire et Azor (1778), Ignaz Umlauf’s Das Irrlicht (Will-o’-the-Wisp, 1782), and Joseph Martin Ruprecht’s Das wütende Heer (The Wild Army, 1787). But it was the suburban operatic repertoire that had the most direct influence on The Magic Flute’s libretto. German opera flourished in commercial theaters that began appearing after 1776 in the Viennese suburbs. In the late 1780s and early 1790s, productions of magical operas shifted to the Leopoldstadt Theater and, after Schikaneder’s assumption of the directorship there, also to the Wiednertheater.

A particularly important prototype of Viennese magical, fairy-tale opera is Oberon, König der Elfen, premiered by Schikaneder’s troupe on November 11, 1789, with a libretto by Wiednertheater actor and playwright Karl Ludwig Giesecke and music by Paul Wranitzky. For the Viennese Oberon, Giesecke adapted (or, according to some commentators, plagiarized) the North German text written in 1788 and published in 1789 by the actress Friederike Sophie Seyler, who in turn based her work on Christoph Martin Wieland’s 1780 epic poem Oberon. In his revision, Giesecke executed many changes that closely resemble those found in earlier Viennese librettos that also adapt preexisting texts (such as Stephanie’s libretto for The Abduction). Wranitzky was no doubt closely familiar with these earlier Viennese operas, since in the late 1780s he served as the orchestral director, first at the Kärntnertortheater during the National Singspiel revival, and later at the Burgtheater. Giesecke reduced passages of spoken dialogue and the number of arias, ultimately allowing for fewer but longer musical numbers (with more of a sense of contrast): the first act of Seyler’s original libretto, for example, features two arias for both the Papageno-like servant Scherasmin and the Tamino-like hero Hüon, whereas the corresponding first act of Giesecke’s text features only one aria for each, allowing for greater stylistic distinction.18 Giesecke also created numerous ensembles, either from Seyler’s solo numbers or from her dialogues. At the very beginning, for example, Giesecke transforms a spoken monologue and an aria for Scherasmin into an introductory multisectional action duet for Scherasmin and Hüon, in which Scherasmin complains about his lonely existence in the woods (where he retired after the death of his master, Hüon’s father), is scared by the approaching Hüon (whom he mistakes for the bringer of death), and then hides and is discovered by Hüon. Also commensurate with Viennese German libretto adaptation is Giesecke’s creation of multisectional finales for the first and second acts. Just as in The Abduction and other Viennese works from the National Singspiel era, Giesecke’s finales alternate musical dialogue with moments of reflection, which are often moralistic.19 In the first-act finale, for instance, Oberon exhorts Hüon to be brave and virtuous, and Hüon promises to be just that. Oberon then addresses a group of dervishes, whom he had earlier punished for religious hypocrisy, urging them to be true to their religious beliefs. As Oberon flies away, the finale concludes with a section in which Hüon, Scherasmin, and the dervishes celebrate Oberon, thank him for his “teachings,” and promise to devote themselves to virtue. The finales of Oberon and its Viennese predecessors likely served as models for the finales of The Magic Flute, where passages of dialogue alternate with communal, reflective (and often moralistic) moments. Many passages come to mind: the first-act finale opens with the Three Boys preaching virtue to Tamino, and the second-act finale opens with an episode in which the Three Boys prevent Pamina from stabbing herself. Mozart usually introduces striking shifts in tempo, dynamics, and style to emphasize these maxims – in particular, he often employs the pastoral style in connection with moralistic and utopian ideas.20

Following the production of Oberon, Schikaneder’s company produced several magical operas, which recent studies have identified as the closest precursors of, and models for, The Magic Flute libretto. Many of these works were heavily indebted to another work of Wieland’s (written in collaboration with his son-in-law, J. A. Liebeskind): the three volumes of fairy tales titled Dschinnistan, published between 1786 and 1789. Three musical works based on Dschinnistan premiered in Vienna in the seasons leading up to The Magic Flute. The earliest one, Der Stein der Weisen, oder Die Zauberinsel (The Philosopher’s Stone, or The Magic Island), premiered a little over a year after Oberon, on November 11, 1790, with a libretto by Schikaneder. The work became particularly prominent in 1996, after musicologist David Buch found that a manuscript score of Der Stein der Weisen, newly returned to the Hamburg State and University Library from Russia, contained attributions of two segments of the second-act finale to Mozart. (Even before this discovery, the second-act duet “Nun liebes Weibchen” [K. 625] had been generally considered Mozart’s work because of the existence of a partial autograph).21 Der wohltätige Derwisch, oder Die Schellenkappe (The Beneficent Dervish, or The Fool’s Cap) was also composed to a text by Schikaneder by a collection of composers. Premiered in early 1791, just a few months before The Magic Flute, its musical numbers are not as extensive as those in Der Stein der Weisen. This is reflected in its genre designation: Whereas surviving printed librettos referred to Der Stein der Weisen as “eine heroisch-komische Oper” (a heroic-comic opera), Der wohltätige Derwisch was designated a “Lust- und Zauberspiel” (comedic and magical play). (The third Dschinnistan opera was Kaspar der Fagottist, oder Die Zauberzither and will be discussed in the section below.)

Composed by the same author for the same company and theater, the texts of Der Stein der Weisen and Der wohltätige Derwisch share numerous similarities with The Magic Flute. All three works are infused with aspects of the Dschinnistan tales, including supernatural elements, magical objects, religious ceremonies, exotic settings, princely couples accompanied by comical servant ones, and wise, Sarastro-like figures. Scholars have identified numerous elements of The Magic Flute’s libretto that originated in the tales of Dschinnistan, one of which was in fact titled “Lulu, oder Die Zauberflöte” (Lulu, or The Magic Flute). Other characters and plot devices Schikaneder most likely derived from Dschinnistan include the Three Boys (“Die klugen Knaben” [The Clever Boys], volume III, story 3); the tests of flood and fire and the ancient Egyptian setting (“Der Stein der Weisen,” volume I, story 4); a villainous slave who spies on the heroine and is punished rather than rewarded for it (“Adis und Dahy,” volume I, story 2); and a hero who falls in love with the heroine’s portrait (“Neangir und seine Bruder” [Neangir and his Brothers], volume I, story 3).22 Whereas the German reform drama represents an important general context for the libretto of The Magic Flute, many specific elements of the opera were clearly derived from fairy-tale Singspiele of the Viennese suburban theaters and late eighteenth-century fairy-tale literature.23

Suburban Subversion and Parody

To fully understand The Magic Flute libretto, we must consider both how it resembles and how it differs from the works that immediately preceded it in the suburban theaters. Der Stein der Weisen and Der wohltätige Derwisch served as models in some respects; however, they do present a slightly different tone from The Magic Flute in that they partially abandon the reformist zeal that characterized the German reform repertoire at the Viennese National Theater. In these pre-Magic Flute works, Schikaneder seems to reference works produced at the Leopoldstadt Theater, his main competitor in Vienna at this time. According to Buch, the Leopoldstadt Theater started producing a lot of magical works after 1784, and this trend continued into the 1790s.24 The aesthetic principles pursued in these works differed substantially, however, from those at the National Theater. The Leopoldstadt Theater to a large extent continued the traditions of earlier Viennese popular theater. Although Leopoldstadt plays were no longer improvised, as was the case throughout the first half of the eighteenth century, they still contained risqué humor, coarse language, and often engaged in parodies of more serious dramas. These elements often centered around the stock character of a comical male servant figure, called Hanswurst in the early part of the eighteenth century and Kaspar (or Kasperl) in the Leopoldstadt productions.25

One Leopoldstadt opera with coarse comedy that scholars have cited as related in content to The Magic Flute is Das Sonnenfest der Braminen (The Brahmins’ Sun Festival), an exotic opera with a plot related to that of The Abduction, which premiered on September 9, 1790. Several scenes of Das Sonnenfest explicitly ridicule elevated situations from reform dramas, such as Lanassa. The plots of both works center on righteous Europe and heroes who rescue heroines in distress from either a harem (Das Sonnenfest) or an inhumane religious ritual (Lanassa). But the Leopoldstadt work upends the virtuous borrowed plot. In Lanassa, the European hero is aided by the long-lost brother of the heroine, who, even before recognizing his relationship to the heroine, decides to save her for humanistic reasons (“Menschenliebe”). In Das Sonnenfest, by contrast, the main hero is nearly seduced by his long-lost sister in a suggestive duet.26

The same irreverent ethos dominates another pre-Mozart Dschinnistan opera, Kaspar der Fagottist, oder Die Zauberzither (Kaspar the Bassoonist, or The Magic Zither), premiered at the Leopoldstadt Theater on June 8, 1791.27 In the nineteenth century, this work became a source of yet another controversy surrounding The Magic Flute’s libretto: in an 1841 article, Friedrich Treitschke suggested that after the premiere of Kaspar der Fagottist Mozart and Schikaneder transformed the initially sympathetic Queen of the Night into a villainess to avoid replicating the plot of this Leopoldstadt opera, which featured a sympathetic fairy queen Perifirime. This theory is generally discredited nowadays.28 The operas do share numerous features, including a prominent use of “magic” instruments. This particular shared feature, however, illustrates the different aesthetics guiding the two works. In The Magic Flute, Tamino’s flute and Papageno’s magic bells tame wild animals, give Tamino and Pamina encouragement and strength at crucial moments, and pacify Monostatos and his crew. The opera’s celebration of music’s ethical powers creates a connection to the Orpheus story, the subject of numerous operas and ballets featured at court theaters in Vienna and elsewhere.29 Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice, which premiered in Vienna in 1762, became the most celebrated representative of this elevated type of court opera; it was performed several times at the National Theater in 1782 and 1783. Der Fagottist, by contrast, ridicules rather than emulates the Orpheus myth and opera seria.30 Der Fagottist’s counterpart to the magic flute is a magic zither presented by Perifirime to Tamino-like Prince Armidoro, but it is mainly used in various amorous adventures. Even less like its Magic Flute counterpart is the eponymous magic bassoon. Throughout the opera it is associated with sexual innuendo, such as when Kaspar uses it to impress the servant Palmire or when he complains about his broken “Blasinstrument” (blowing horn) after returning from a tryst with Palmire. Also peculiar is the duet in which Kaspar gives a bassoon lesson to the Monostatos-like character Zumio, in which quite explicit references to oral sex abound.31

Elements of similar fairground humor, quite distant from the preferences of German reformists, can also be found in Der Stein der Weisen and other magical operas by Schikaneder and his team. For example, Der Stein der Weisen plays humorously with the topic of marital infidelity when it presents how the evil magician Eutifronte abducts the Papagena-like character Lubanara, who was earlier heard praising infidelity in an aria, and places a pair of gilded antlers (a prominent symbol of cuckoldry) on the head of Lubano, the Papageno-like husband of Lubanara. Schikaneder and his compositional team further ridicule Lubano’s unhappy marriage by bringing in a chorus of hunters, who mistake Lubano for a stag and chase him around.

Reformist Qualities of The Magic Flute’s Libretto

Even though The Magic Flute libretto emerged from, and is closely associated with, the world of Viennese popular suburban theater, it differs from that tradition significantly in that it mainly avoids the parodistic elements featured in the Leopoldstadt operas and Schikaneder’s other Wiednertheater librettos, such as Der Stein der Weisen. In fact, a few scenes in The Magic Flute appear to engage Der Stein der Weisen directly in a moralistic dialogue. For example, the padlock the Three Ladies place on Papageno to punish him for pretending to be the killer of the serpent that threatened Tamino at the beginning of the opera has a parallel in the padlock that Lubano places on the door of his cabin to prevent the unfaithful Lubanara from meeting other men. But such parallels also point to ways in which the librettos of these operas differ significantly. In Der Stein der Weisen, the locking of the door occurs within a duet for Lubano and Lubanara (No. 5, “Tralleralara! Tralleralara!”), and the two characters react to it with a communal utterance of nonsensical syllables: “Mum, mum! Dideldum!” In The Magic Flute, the first-act quintet (No. 5, “Hm! Hm! Hm!”) begins with the unlocking of Papageno’s padlock and then leads to a communal statement, a maxim that explains the moralistic significance of the episode:

|

|

Mozart launches the maxim with the musical phrase that introduced the nonsensical reflection in Der Stein der Weisen, as if he wanted to point out the striking difference between the neglect of the padlock’s moralistic potential in the earlier work and the didactic significance of the maxim in the later opera.

The attention to communal, moralizing statements in The Magic Flute exemplifies calls for such statements in German reformist theater criticism of the time. For example, a 1789 essay in the Kritisches Theater-Journal von Wien complains that Karl Friedrich Hensler’s Leopoldstadt play Das Glück ist kugelrund, oder Kasperls Ehrentag (Happiness is Fickle, or Kaspar’s Day of Honor, premiered on February 17, 1789) does not present clear moral truths and should not be performed any longer; according to the critic, only fairy-tale works with clear moral statements are worthy of presentation.32 The Magic Flute’s libretto is governed by ideas similar to those expressed in the critique, as demonstrated by an actual link to the quite popular Das Glück ist kugelrund.33 In both works, characters attempt to commit suicide by hanging themselves. In Hensler’s play, Kasperl’s suicide attempt leads to magical comedy: first, when the ladder that he climbs to reach a tree branch disappears; and second, when a door with a nail to hold the noose transforms into a cloud from which a fairy appears to tell him she is bringing him happiness.34 In the second-act finale of The Magic Flute, Papageno is prevented from hanging himself by the Three Boys who, unlike Hensler’s fairy, draw a moralistic warning from the situation: “Stop, Papageno! And be smart! / Life is lived only once, let that be sufficient for you.” (“Halt ein, o Papageno! und sey klug. / Man lebt nur einmal, dies sey dir genug.”)

The subtle, yet significant, differences between The Magic Flute and its most immediate predecessors (the fairy-tale operas of Schikaneder and the Leopoldstadt authors) bring us back to the question of Mozart’s involvement in the libretto’s production. The opera’s adherence to the principles of a reformed, didactic German national theater contrasts with most other Schikaneder librettos from the Wiednertheater era, and this in turn suggests that Mozart may have been responsible for the difference. That Schikaneder would be willing to make concessions to Mozart’s suggestions about the overall aesthetic character of the libretto is not surprising, since, compared to the other composers working for the suburban theaters in Vienna, Mozart was an international celebrity. Mozart was also the first composer writing for the Viennese suburban stage who also had experience with both the National Theater and the court theater in Vienna. In the works created with his long-term creative team, Schikaneder seems to be concerned about competing with the parodistic and risqué productions at the Leopoldstadt Theater and heeding the principle, which he himself mentioned in prefaces to his own works, that morals and reformist uprightness are not good for the box office of his commercial institution.35 However, in his collaboration with Mozart, Schikaneder clearly emphasizes elements associated with genres, such as the German reform drama and opera seria, produced predominantly by state- or court-supported institutions. This includes engaging in moralizing statements, especially on the part of Sarastro and the Priests. Some of these statements are reprehensible – among the most straightforwardly racist or sexist utterances in all of eighteenth-century opera – and are usually censored in present-day productions of The Magic Flute, although we can assume that they were widely accepted in the eighteenth century. These statements, however, do contribute to the unique quality of the opera’s libretto and its combination of aesthetic viewpoints associated with suburban, commercial, and popular theatrical traditions on the one hand, and reformist, national, state- and court-sponsored traditions on the other.

The Magic Flute is a notoriously complex work that accommodates a large number of different theatrical and musical styles. The opera’s connection to the ideals of German reform drama is particularly significant, because it illustrates that even within the confines of a private, commercial theater Mozart and Schikaneder aimed at the creation of a high-minded work. In the handwritten list of his compositions, Mozart famously referred to The Magic Flute as a “teutsche Oper” (German opera), an unusual designation since the titles of most other contemporary Viennese operas referred to the works’ dramaturgical features, not their language or national character (e.g., heroisch-komische Oper or lustiges Singspiel). The resonance between The Magic Flute and the moralistic concepts of German national theater suggests that the designation might have had a symbolic meaning – that for Mozart The Magic Flute, with its didacticism, represented a truly German national work.

The Magic Flute was conceived and created specifically for the Theater auf der Wieden and its company of players, under the direction of Emanuel Schikaneder. Despite its status today as a work of genius, Schikaneder and Mozart’s opera was not conceived in a vacuum, so understanding its vibrant theatrical context can help us avoid subscribing to what David Buch has called “the myth of singularity.”1 Like all works of art, The Magic Flute was a product of its time and place: Schikaneder and other librettists had written magical operas for the Theater auf der Wieden in the years immediately preceding 1791; Mozart and Schikaneder created roles with specific singers and their talents in mind; and other theaters were also presenting operas featuring similar characters and plotlines. Certain features of The Magic Flute adhere to traditions that were already in place at this theater – a plot that includes a serious couple as well as a comic one, for example, or the simple style of Papageno’s entrance aria. And musical aspects of the opera, such as the role of the choruses, bear more resemblance to the works of the theater’s regular or “house” composers than they do to the works of other composers that were also performed there.2 The personnel of the Theater auf der Wieden were also influenced by other theaters in the city, particularly by the Theater in der Leopoldstadt, their main competitor. This chapter provides an overview of the Theater auf der Wieden under Schikaneder’s directorship in the years leading up to the premiere of The Magic Flute, in order to situate the opera in its original performance venue.

The Freihaus auf der Wieden and Its Theater

Until 1850, the city of Vienna comprised only the area that is today’s first district. It was encircled by a massive, defensive wall, which, in turn, was surrounded by a flat area called the glacis, which served to expose invading armies to the city’s defenders. Abutting the glacis were the various suburbs or Vorstädte, all of which are today a part of the city of Vienna. In 1781, five years after Joseph II announced his Spektakelfreiheit, which allowed private theaters to put on performances for profit, Karl Marinelli opened his Theater in der Leopoldstadt, the first suburban theater in Vienna. Schikaneder, who in 1786 was employed at the Burgtheater, appealed to Joseph for special permission to open a theater just like Marinelli’s, but on the glacis, in a location where people living in three suburbs would have had easy access to it. Joseph turned down the request, but agreed that Schikaneder could open a theater within a Viennese suburb instead. In the end, it was a German actor and director, Christian Rossbach, who received permission from Joseph in 1787 to build a theater in the suburb of Wieden (which was incorporated as Vienna’s fourth district in 1850).

The Theater auf der Wieden, as it came to be called because of its location in the eponymous suburb and its proximity to the Wieden river, was a two-story rectangular theater that could seat about 800 people and operated from 1787 to 1801. It was sometimes referred to as the Wiednertheater or the Schikanedertheater, but should not be confused with the Theater an der Wien, which replaced it in 1801 and still exists today. Although the Theater auf der Wieden was a free-standing building, it was situated within the perimeter of an enormous apartment complex in greater Vienna called the Starhembergisches Freihaus, after the Starhemberg family, which had owned the land as a fief since 1643. Four years later, upon payment of a thousand gulden to the court, the family was released from owing property taxes in perpetuity, hence the name “Freihaus.”3 After several fires and much subsequent rebuilding, it became, by the end of the eighteenth century, the largest privately owned apartment complex in Vienna. The Freihaus encompassed 25,000 square meters (269,098 square feet), with 402 buildings of various sizes, and housed around 10,000 people. The floorplan of the building gives a sense of how large the Freihaus was, particularly if we note how the 800-seat theater, located below the third courtyard (Hof), comprises a small fraction of the total space (see Figure 3.1.). We know that by the mid-nineteenth century the complex boasted a concert hall, a library, a dance school, a sports center, and the businesses of countless artisans. With excellent drinking water to be had from its many wells, the Freihaus was essentially a self-contained city within the city. Tailors and shoemakers provided their services, and small shops sold everything from textiles, needles, and nails, to socks, pens, ink, and even violin strings.4 By adding a theater to the Freihaus, Rossbach, the first director, was probably hoping to take advantage of the patronage of a built-in audience.5

Figure 3.1 Plan of the ground floor of the Hochfürstlich Starhembergischen Freihaus auf der Wieden in Mozart’s day. The Freihaus Theater can be seen above the garden. Andreas Zach, landscape architect, 1789. Pen, ink, and watercolor.

The theater building commissioned by Rossbach (in which The Magic Flute would eventually premiere) was built by Andreas Zach, who was also responsible for renovations of the entire Freihaus. According to Michael Lorenz, the original plans for the theater show that its walls were of masonry, but the interior was made of wood, in keeping with the conventions of such buildings at the time. While it was not physically connected to the surrounding, far larger Freihaus building (it stood in the middle of a field), its tiled roof was taller than the apex of the Freihaus’s roof.6 The plans for the theater also show a wooden passageway – one of six in the Freihaus – which was likely intended to allow audience members to cross the courtyard and arrive at the theater without muddying their feet.7 The theater’s dimensions were thirty by fifteen meters, with almost half of that space occupied by the twelve-meter-deep stage area, presumably to allow for elaborate sets.8 Surviving engravings from some productions as well as descriptions of sets in contemporary press reports attest to their grandeur. Tall buildings and realistic trees flank singers as they descend into the ground on a moving platform in Der Stein der Weisen (The Philosopher’s Stone), and a review of Babylons Pyramiden (The Pyramids of Babylon) refers to the theater’s technical capability to surprise the audience with a rustic, hut-like exterior that gives way to show a large, impressive temple, or an enormous haystack that opens up to reveal many beautifully rendered rooms.9 As to the appearance of the interior of the theater, it was painted simply and included a proscenium arch flanked by life-size statues of a knight with a dagger and an elegantly masked lady, but it is unclear whether it looked this way from its early days. Entrance to the theater cost seventeen kreutzer to the parterre and seven to the upper floor.10

Lorenz’s extensive research on the history of the theater building shows that there were several attempts to expand its capacity of 800 seats by building either a new wing or an entirely separate building in a different courtyard of the Freihaus. A map of the planned expansion that Lorenz discovered shows what the actual second floor of the theater looked like, including private boxes and a spiral staircase.11 These more ambitious plans, which date from around 1790, were probably curtailed due to financial problems, when the main backer of the theater, Joseph von Bauernfeld, faced financial ruin in 1793.12 Schikaneder, the director at the time, had to pay off the creditors, and the owner of the theater, Anton von Bauernfeld, Joseph’s brother, gave the building to his wife as part of a divorce settlement in 1794. The list of items from the theater that were transferred to Antonia von Bauernfeld includes everything from the walls and the number of private boxes to the locations of the various benches and whether or not they were upholstered.13

Early Directors of the Theater auf der Wieden

Rossbach was already running performances of plays, ballets, and some operas in a temporary, wooden structure in the city center, when, on September 29, 1787, he announced in the Wienerzeitung that his new theater would be opening on October 7 and that, hoping to please all theater friends and benefactors, he would spare no expense and present a play with songs, a related opera buffa, and a plot-appropriate ballet of national character.14 Such mixtures of pieces were common for traveling troupes and catered to the taste of the Viennese public.15 We do not know the exact repertoire Rossbach presented on his stage, but there could not have been much of it since his directorship lasted a mere six months.

The next director, Johann Friedel, a writer and the leader of his own traveling acting troupe, took over, together with Eleonore Schikaneder (a member of the troupe and the estranged wife of Emanuel), in 1788. A number of oft-quoted reports claim a romantic relationship between these two, but since there are no primary sources to confirm it, this may be a result of theater gossip handed down through the generations.16 We do know that Emanuel and Eleonore were apart during this time, because he was in Augsburg with his troupe of opera singers. Friedel was better known and more successful as a writer, and his tenure as director was largely unsuccessful. His preference for Lessing and Schiller over more standard comic fare did not endear him to contemporary audiences, although it coincided with Emperor Joseph II’s intention to elevate and promote German-language spectacles as part of his larger plan to unify German-speaking nations.

In a speech given on March 24, 1788, at the premiere performance of his directorship, Friedel begged the audience to be patient with him and not to expect too much.17 Reviewers criticized Friedel as inexperienced because of various directorial missteps; these included offering too many different shows in a row, with the result that the actors were underprepared, and scrambling to find enough performers to cover each type (Fach) of role – even assigning women to play male roles, as one outraged report notes.18 One writer acknowledged that these lapses might have been due to Friedel’s ill health, but added that this was no excuse for subjecting audiences to ill-prepared actors reading rather than performing their parts from memory or for reducing the role of reviewers to commenting on whether these parts were read poorly or relatively well.19

Thus far, Friedel’s troupe had performed only plays, but in January of 1789 he made plans to introduce German-language opera. A German opera troupe was engaged to begin after Easter; the goal was to offer a wider variety of entertainment.20 Even prior to Easter, Friedel brought opera, mainly in the form of a few German translations of Italian comic works, to the Theater auf der Wieden for the first time. The press deemed this move a financial calculation, comparing it to Schikaneder’s earlier engagement with the state theaters and writing that although Schikaneder’s previous performances in a Viennese theater had been mediocre at best, they nevertheless filled the house with a charmed Viennese public, always eager for more German-language opera.21 German opera, in other words, was immensely popular but panned by the critics. As the Kritisches Theater Journal von Wien damningly put it, “The theater was full, but the actors were empty.”22 Friedel ran the theater for just a year and died after an extended illness on March 31, 1789, at the age of thirty-eight. Since she was female, the codirector, Eleonore Schikaneder, may have thought it unrealistic to run the theater by herself, so she sought the assistance of her husband, Emanuel. The years of his directorship represented a golden age, the most important period in the story of the Theater auf der Wieden and the one that produced The Magic Flute.

Characters and Repertory

The first work to premiere under Schikaneder’s directorship of the theater was his own Der dumme Gärtner im Gebürge, oder die zween Anton (The Stupid Gardner in the Mountains, or The Two Antons), with music by Johann Baptist Henneberg and Benedikt Schack. Schikaneder himself played Anton, a character intended as competition for the popular Kasperl, a comic figure who reigned at the rival Theater in der Leopoldstadt. Anton never achieved Kasperl’s level of acclaim in Vienna, but both characters represent a tradition in Viennese comedy that originates in the much older Hanswurst figure, popularized by Josef Anton Stranitzky in the first half of the eighteenth century. With roots in the Italian commedia dell’arte, this largely improvised comic type allowed Stranitzky and later performers the freedom to create a witty lower-class or servant character, who could outmaneuver his aristocratic or bourgeois masters while improvising lines that were relevant to, or even critical of, contemporary society. Much of the appeal of such comedy lay in making the upper classes look ridiculous. It was for this reason that Empress Maria Theresia had attempted to control improvised comedy in 1752, finally banning it in 1770, at which time a protocol for censoring theatrical works was established.23 Nevertheless, improvised comedy continued in full force through the reign of Joseph II. Even a theater reviewer was shocked by what Kasperl was able to get away with on the stage of the Theater in der Leopoldstadt in 1789 as he offended morals and religion, to say nothing of good taste.24

Papageno is the most famous of these lower-class characters, whose lineage continued into the nineteenth century. Having inherited their main features, he is generally bumbling, good-hearted, cowardly, and ruled by his appetites, but he deviates from them in that he says nothing in The Magic Flute that is particularly subversive. Characters such as Leporello in Don Giovanni, also share Hanswurstian features. Whereas in Mozart’s time such figures were associated more with silliness and coarse humor, the nineteenth-century successors of Hanswurst returned to criticizing authority, not only through improvised lines they might have sneaked into the written text but also in the development of a type of metalanguage that was an unexpected by-product of the censorship process – a censor struck an offensive word from a libretto and replaced it with an innocent one – and the performer, through nuance, could convey the original offensive meaning, presumably much to the delight of the audience.25

On a visit in 1768, Leopold Mozart was unamused by the undying popularity of Hanswurst and characters of his ilk among the Viennese and called their antics “foolish stuff.”26 But the elitist opinion of Mozart, senior, was in the minority. The Viennese loved their Hanswursts, Antons, and Kasperls.27 Wanting to capitalize on the popularity of Der dumme Gärtner, Schikaneder created six sequels featuring Anton over the next six years. In 1791 Mozart wrote his Variations K. 613 on “Ein Weib ist das herrlichste Ding auf der Welt” (A woman is the most wonderful thing in the world), a popular aria from the second Anton opera, Die verdeckten Sachen (The Obscured Things).28

On November 7, 1789, Schikaneder presented Paul Wranitzky and Karl Ludwig Gieseke’s opera, Oberon, König der Elfen (Oberon, King of the Elves), initiating a new era in Viennese popular theater that culminated in Die Zauberflöte.29 Oberon was enormously successful, and Schikaneder’s rival Karl Marinelli, director of the Theater in der Leopoldstadt, took notice and began presenting competing magical operas in his theater. Oberon was novel, not only because it was a magically themed and newly written German-language opera, but also because magical aspects were a central rather than an incidental part of the misadventures of an Anton or Kasperl figure.30 There had been magical operas in Vienna before this time, of course, but the subject of the supernatural was treated differently then. During the reign of Maria Theresia (1740–80), magic on the stage had been frowned upon because it was thought to encourage superstition and to detract from religious teachings.31 But under her son Joseph, censorship around magic on the stage was loosened, and later operas such as Oberon and The Magic Flute employed aspects of the supernatural to transmit Enlightenment morals. For example, Sarastro’s powers of good are related to the sun, the Queen of the Night’s evil powers are connected to the moon, and the rites undergone by Pamina and Tamino emphasize fortitude and wisdom. The religious-seeming ceremonies and even quasi-religious figures like Sarastro would not have made it past the censor prior to 1780. Joseph’s successors (Leopold II and Francis II) tightened censorship laws again, but with more emphasis on eradicating political and sexual content than magical or anti-religious material.32

The centrality of magic was not the only similarity between Oberon and The Magic Flute. Both operas include a couple subjected to various difficult trials, a magical instrument (in Oberon it is a horn), music that compels villains to dance, and the use of coloratura to indicate supernatural power. Oberon is a trouser role, written for soprano and premiered by one of the central figures of Schikaneder’s troupe, Josepha Hofer, who, in addition to being Mozart’s sister-in-law, was also the first Queen of the Night.33 Other than The Magic Flute, Oberon was perhaps the best-known magical opera of its time, and it was performed widely outside Vienna, for example in Frankfurt and Hamburg.34 One reason so many other Viennese magical operas, both those contemporary with and especially later than The Magic Flute, never captured the imagination of audiences outside the city could be their connection to the so-called Lokalstück (local farce). This tradition of popular comic pieces included numerous references to either Viennese landmarks or local incidents that someone in Vienna would have understood, but that made them less accessible to people living elsewhere.35

Since theaters and their offerings were a major source of entertainment for the public, people frequently attended the same show multiple times. In Mozart’s day, even the upper echelons of society attended the Theater auf der Wieden and its rival houses. Leopold II and his wife, Maria Luisa, for example, brought the visiting Sicilian court to a performance of Der Stein der Weisen (1790), having also attended a performance of the same opera nine days earlier. The nobility often rented boxes for an entire season, sometimes in more than one theater, which gave them (or their friends) the opportunity to attend all performances of all the works in any given season. The theater provided a place of entertainment, and repeated attendance could bring great familiarity with the repertoire, but it was also a useful venue for conducting business deals and pursuing romances – eighteenth-century opera audiences were hardly as quiet and polite as twenty-first-century ones.

Schikaneder’s Troupe