Recent autocracy research illustrates that authoritarian regimes do not only rely on repression but also institutionalize sophisticated forms of co-optation (Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008; Gandhi and Przeworski Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2007; Ginsburg and Simpser Reference Ginsburg and Simpser2014; Morgenbesser Reference Morgenbesser2016).Footnote 1 In addition, there is a nascent strand of literature which shows that autocrats apply different strategies of legitimation to prolong their rule (Dukalskis Reference Dukalskis2017; Gerschewski Reference Gerschewski2013; Grauvogel and von Soest Reference Grauvogel and von Soest2014). Several new typologies categorize authoritarian regimes as per these institutional features and, based on average regime lengths in each category, propose more or less enduring autocracy types (e.g. Geddes et al. Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014; Kailitz Reference Kailitz2013; Wahman et al. Reference Wahman, Teorell and Hadenius2013). These contributions highlight crucial factors of autocratic survival – yet, by focusing on single aspects of authoritarian rule, they cannot sufficiently explain why some authoritarian regimes are more resilient than others.

This article examines how authoritarian regimes combine various strategies of repression, co-optation and legitimation to remain in power. The contribution of the article is two-fold. First, I conceptualize the hexagon of authoritarian persistence as a framework to explain how authoritarian regimes manage to survive. The hexagon is a modified version of Johannes Gerschewski’s (Reference Gerschewski2013) three pillars of stability and conjointly looks at six core strategies of autocratic rule (repression of physical integrity rights, repression of civil and political rights, co-optation as compensating vulnerability or simulating pluralism, specific and diffuse support of legitimation). Based on set theory, the hexagon can account for the causal complexity of autocratic survival and breakdown. Second, the empirical part of the article applies the hexagon by using fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). The exploratory and case-oriented analysis refers to 62 authoritarian regimes of various types (1991–2010) and examines the combined effects of the several strategies on authoritarian persistence. The resulting five configurations of the hexagon – which I call hegemonic, performance-dependent, rigid, overcompensating and adaptive authoritarianism – provide a new and finer-graded picture of autocratic survival.

The article proceeds as follows: the subsequent theoretical sections offer a literature review and illustrate the added value of the hexagon as a new framework to explain authoritarian persistence. Before spelling out the operationalization of the hexagon, I outline the methodological approach and demonstrate why fsQCA is most suitable to assess the different strategies of autocratic power maintenance. The last part summarizes the analysis and discusses five configurations of the hexagon as the major findings of this article, followed by some concluding remarks.

Repression, co-optation and legitimation

The burgeoning research about autocracies illuminates crucial aspects of autocratic survival. Several contributions offer detailed qualitative analyses of modern authoritarianism in one or a few cases (Brownlee Reference Brownlee2007; Hemment Reference Hemment2015; Slater Reference Slater2010). They further study the strategies and techniques in single types of autocracies and illuminate, for example, how electoral regimes make use of seemingly democratic institutions to prolong their rule (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010; Morgenbesser Reference Morgenbesser2016; Schedler Reference Schedler2006).

Sharing a strong focus on authoritarian institutions, there is also a range of quantitative studies which reveal that authoritarian regimes do not solely rely on repression but institutionalize clever ways of co-optation to handle the challenges of sharing power with influential elites while controlling the population at large (Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008; Gandhi and Przeworski Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2007; Ginsburg and Simpser Reference Ginsburg and Simpser2014; Svolik Reference Svolik2012). By looking at the most prominent institutional characteristic of a regime, several new categorizations of autocracies in monarchies, personalist, military or single- and multiparty regimes have been proposed (Cheibub et al. Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010; Geddes Reference Geddes1999; Geddes et al. Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014; Hadenius and Teorell Reference Hadenius and Teorell2007; Kailitz Reference Kailitz2013; Wahman et al. Reference Wahman, Teorell and Hadenius2013). The novel data sets have been applied in numerous large-N comparisons and triggered a lively debate about the resilience and performance of the different authoritarian regime types (e.g. Kailitz and Stockemer Reference Kailitz and Stockemer2017; Miller Reference Miller2015; Roberts Reference Roberts2015).

The typologies of authoritarian regimes offer different explanations about the survival strategies in each regime type. Barbara Geddes (Reference Geddes1999) argues that single-party regimes are more resilient than other regime types because party cadres are more likely to negotiate. By using game theory, she illustrates that co-optation rather than exclusion is the rule in this regime type since everyone is better off if all factions can hold on to office. Axel Hadenius and Jan Teorell (2007: 153) argue that multiparty regimes are least resilient and most likely to democratize because their electoral system allows for some contestation, which makes these regimes amenable to gradual improvements. These and other accounts of autocratic longevity are theoretically compelling, yet there are significant empirical variations concerning the regimes’ durability in each of the proposed categories. Several multiparty regimes, for example, make strategic use of the minimally competitive elections and seem particularly persistent (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2013). Generally, the typologies are based on different concepts of autocracy, refer to divergent empirical scopes and make contrary statements about the resilience of the various regime types. The comparisons of the data sets by Matthew Wilson (Reference Wilson2014), Edeltraud Roller (Reference Roller2013) and Michael Wahman et al. (Reference Wahman, Teorell and Hadenius2013) illustrate that the choice of data set can have significant effects on the results of empirical analyses.Footnote 2 Beside this and critical for the analysis in this article is that while the new typologies highlight single factors of authoritarian rule, their unidimensional classifications as per the most outstanding institutional characteristic of a regime do not explain the multifaceted nature of authoritarian survival.

In contrast to this, Gerschewski’s (Reference Gerschewski2013) model of the three pillars is a seminal framework which attempts to synthesize the multiple factors of autocratic stability. By arguing that recent autocracy research focuses mainly on repression and co-optation and has lost sight of legitimation, the pillars assume that any type of autocratic regime makes use of these three core principles of autocratic rule. The difference between regimes is that they institutionalize the strategies of repression, co-optation and legitimation in varying degrees. There is a nascent strand of literature which illustrates that claims to legitimacy are crucial aspects of autocratic survival (Dukalskis Reference Dukalskis2017; Dukalskis and Gerschewski Reference Dukalskis and Gerschewski2017; Kailitz and Wurster Reference Kailitz and Wurster2017; Maerz Reference Maerz2018; Omelicheva Reference Omelicheva2016; Polese et al. Reference Polese, Ó Beacháin and Horák2017; von Soest and Grauvogel Reference von Soest and Grauvogel2017a). Furthermore, Carsten Q. Schneider and Seraphine F. Maerz (Reference Maerz2017) analyse how the interplay of repression, co-optation and legitimation affects the survival of electoral regimes. However, as I illustrate in the following section, to assess the different strategies of authoritarian power maintenance in autocracies at large, the theory of autocratic persistence needs to be further developed.

The hexagon of authoritarian persistence

This article conceptualizes the hexagon of authoritarian persistence as a theoretical framework to analyse the multi-causal phenomenon of authoritarian persistence. The hexagon is based on Gerschewski’s (Reference Gerschewski2013) three pillars of stability and defines the institutionalization of various forms of repression, co-optation and legitimation as the core survival strategies of autocratic rule.Footnote 3 While Gerschewski illustrates in great detail why repression, co-optation and legitimation are relevant for autocratic survival, this article outlines these aspects only briefly and rather focuses on explaining how the hexagon of authoritarian persistence differs from the three pillars of stability. To further develop the theory of autocratic persistence, I propose two major modifications of Gerschewski’s three pillars, as explained in the following two sections. First, I suggest different concepts of co-optation. Second and more importantly, instead of the rather static model of the three pillars, I introduce the hexagon as an enhanced framework which is based on set theory and accounts for the causal complexity of autocratic survival.

New concepts of co-optation

The three pillars have two dimensions each: specific and diffuse support of legitimation, high- and low-intensity repression, formal and informal co-optation (Gerschewski Reference Gerschewski2013). The two dimensions of repression distinguish between highly visible, violent acts that target a large number of people or well-known individuals and less visible forms of coercion such as surveillance, harassment or the denial of employment and education.Footnote 4 To conceptualize the hexagon, I adopt these two forms of coercion but I change the slightly misleading names since the labels of high- and low-intensity repression wrongly suggest that these are the endpoints of the same underlying concept. Borrowing the names for both forms of repression from David Cingranelli and David Richards (Reference Cingranelli and Richards2013), I call the first repression of physical integrity rights and the second repression of civil and political rights. Apart from this, I also draw upon Gerschewski’s (Reference Gerschewski2013: 20) non-normative concept of legitimation by Max Weber (Reference Weber2002) and distinguish between specific support (for example, that gained by a good socioeconomic performance or domestic security) and diffuse support of legitimation (for example, ideologies, religious, nationalistic, traditional claims, the charisma of autocratic leaders, cf. Easton Reference Easton1965).Footnote 5

One crucial change when transforming the three pillars into the hexagon concerns the two dimensions of co-optation. While it is theoretically compelling to conceptualize co-optation as formal and informal ways of tying strategic partners to the regime, I hold that such a clear-cut separation is empirically not feasible since formal and informal institutions of co-optation are often inseparably fused (Isaacs Reference Isaacs2014). Furthermore, finding valid indicators for measuring informal institutions is a highly challenging task, particularly for large numbers of cases (Helmke and Levitsky Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004). Therefore, I propose two different and empirically more valid concepts and distinguish between co-optation as compensating vulnerability and co-optation as simulating pluralism.

Following Alexander Schmotz (Reference Schmotz2015: 442), co-optation as compensating vulnerability is defined as the capacity of a regime to compensate for various pressure groups. As per Schmotz (Reference Schmotz2015), these pressure groups include the military, organized labour groups, financial organizations (called ‘capital’), influential political parties, politicized ethnic groups and large-estate landowners. Because these groups have a great threat potential for the survival of authoritarian regimes, they are co-opted by providing them with institutional inclusion or material benefits.

In contrast to this first form of co-optation, I conceptualize a second form – co-optation as simulating pluralism – which is not about real compensation but rather an imitation of it. By establishing fake multiparty systems and pretending competitiveness, this strategy of co-optation is supposed to make elite groups believe that some power is allocated to them while it is only the innermost circle of the regime which maintains full control. Typically, this form of co-optation is observed in so-called hegemonic regimes (Sartori Reference Sartori2005: 205–6). Following the broadly used categorization of autocracies into closed, hegemonic and competitive regimes (Brownlee Reference Brownlee2009; Donno Reference Donno2013), the defining feature of closed autocracies is that they have no elected legislature or rule with a single-party regime. Competitive regimes are multiparty systems which permit at least a minimum amount of electoral competition. As opposed to this, hegemonic regimes hold regular multiparty elections – yet do not allow for real electoral competition. Instead, they maintain sham multiparty systems which are either clearly dominated by the ruling party or consist of several satellite parties which pretend contestation. In other words, hegemonic regimes co-opt strategic elites as loyal members of their own strictly controlled parties or grant them the privileges of official posts in other broadly impotent parties. In both cases, such institutional inclusion is not about a transfer of power but merely about simulating for selected individuals the prospects of political participation while tying their fate to the ruler’s survival. However, these toy parliaments and rubber-stamp politics alone do not ensure a regime’s endurance – it is rather the (non-)effective combination of this co-optation strategy with other strategies of co-optation, legitimation and repression which determines autocratic survival, as the next section further illustrates.

The causal complexity of authoritarian persistence

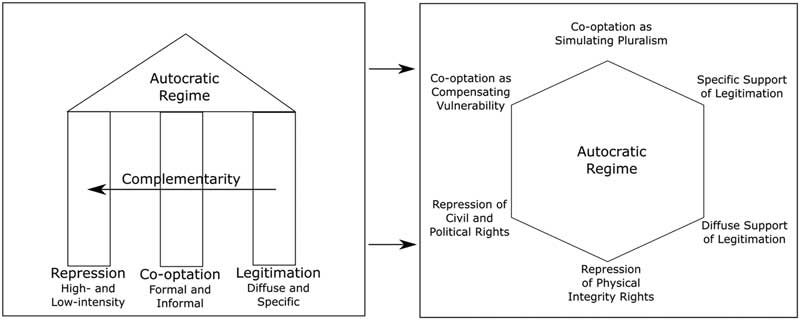

As Gerschewski (Reference Gerschewski2013: 23–5) illustrates in his detailed explanations of the three pillars, decisive for the endurance or breakdown of an autocratic regime are the combined effects of repression, legitimation and co-optation. In other words, stable authoritarian regimes institutionalize the three pillars in varying degrees and display different configurations of them. Gerschewski explains the varying institutionalization between the pillars by referring to exogenous, endogenous and reciprocal reinforcement effects. Based on the concept of institutional complementarity, Gerschewski (Reference Gerschewski2013: 29–30) assumes for autocratic stability all dimensions of the pillars except for high- and low-intensity repression to be mutually exclusive. This results in two stable configurations which combine either both dimensions of repression, diffuse support and formal co-optation or low-intensity repression, specific legitimation and informal co-optation. Yet, I argue that these ‘two worlds of autocracies’ (Gerschewski Reference Gerschewski2013: 30) do not fully grasp the causal complexity of autocratic survival, which is why I propose the hexagon (see Figure 1) as a more elaborated configurational framework.

Figure 1 From Gerschewski’s Three Pillars to the Hexagon of Authoritarian Persistence

The hexagon of authoritarian persistence is rooted in set theory. This implies that the framework accounts for the three characteristics of causal complexity in set theory, namely asymmetric causal relations, conjunctural causation and equifinality (Ragin Reference Ragin1987; Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012: 78). To explain these three core concepts of set theory, I refer to the example of studying authoritarianism. First, autocracy is not simply the opposite of democracy. Geddes’ (Reference Geddes1999: 121) seminal contribution and her statement that ‘different kinds of authoritarianism differ from each other as much as they differ from democracy’ hint at these asymmetric causal relations and counter the simplified classification of autocracies as merely non-democratic. Along these lines, the hexagon is also based on the assumption of causal asymmetry: The reasons for autocratic regimes to endure are not simply the opposite of what explains autocratic breakdown.

Second, the hexagon enables us to look at several aspects of autocratic rule at once and examine how this interplay affects authoritarian persistence. The basic idea of this so-called conjunctural causation is that authoritarian persistence emerges from the intersection of these aspects as appropriate preconditions (Ragin Reference Ragin1987: 25). In contrast to the typologies outlined above, which classify an authoritarian regime by merely focusing on its most prominent institutional characteristic (such as the electoral system or the military), the hexagon zooms in on combinations of conditions which conjointly cause authoritarian persistence. While the model of the three pillars already hints at this conjunctural causation but limits it to two configurations, I look at the different forms of repression, co-optation and legitimation not as mutually exclusive endpoints of the same underlying concept but rather as individual features of authoritarian persistence, visualized in the shape of the hexagon. Based on this enhanced perspective, the hexagon can reflect the diverse combinations of survival strategies in persistent autocracies of various types and is not limited to ‘two worlds’. Furthermore, the hexagon assumes the relationship between the institutionalized forms of repression, co-optation and legitimation to be various instead of always complementary, as it is conceptualized for the three pillars (Gerschewski Reference Gerschewski2013: 29). Following Andreas Schedler (Reference Schedler2013), I hold that the institutional settings in authoritarian regimes are ambiguous due to informational as well as institutional uncertainties. Different from the three pillars analysis, authoritarian persistence is not understood as a static concept of stability but rather as the endurance of authoritarian regimes over time, occasionally also under rather unstable conditions or with counterintuitive combinations of the six strategies, as the empirical explorations in this article show.

Third, the hexagon is based on the assumption of equifinality, meaning that I expect to find different, mutually non-exclusive explanations of authoritarian persistence (Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012: 78). The empirical part of this article is exploratory in its nature and applies the hexagon to identify which strategies authoritarian regimes combine to ensure their survival. The resulting configurations of the hexagon are similar to what Colin Elman (2005) called an explanatory typology. Due to the hexagon’s accounts of asymmetric causal relations, conjunctural causation and equifinality, such configurations clearly differ from conventional understandings of categories in typologies (e.g. Collier et al. 2008: 157) because they are neither mutually exclusive nor collectively exhaustive. Metaphorically speaking, the hexagon is a toolbox of authoritarian rule out of which authoritarian regimes take their set of strategies. As a matter of course, some authoritarian regimes apply similar sets of strategies, which is why I expect to find combinations of strategies which (partly) overlap. The added value of this set-theory perspective on the survival strategies of authoritarian regimes is that it unravels the causal complexity of these survival strategies and thereby provides a new and more finely graded picture of authoritarian persistence.

Research design

Method

The theoretical framework of the hexagon is based on set theory, which strongly suggests using set methods for an empirical application of the framework. Similar to Schneider and Maerz (Reference Schneider and Maerz2017), this article applies fsQCA to analyse authoritarian survival strategies. Set methods employ formal logic and Boolean as well as fuzzy algebra and refer to a rather unusual terminology, which is why this section explains key terms and provides a short outline of how fsQCA is applied.Footnote 6

The strength of fsQCA and its suitability for the analysis in this article is that, instead of looking at single factors in isolation from each other, it allows us to examine the combined effects of several factors on authoritarian persistence. In set-theory terminology, the six strategies illustrated in the hexagon are called the conditions which – depending on their combinations – generate authoritarian persistence or no authoritarian persistence as the two qualitative states of the outcome. The different combinations of the six strategies are so-called configurations of the hexagon.

In fsQCA, asymmetric causal relations are tested by separate analyses for the occurrence and non-occurrence of the outcome (Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012: 81). Accordingly, the summary of the findings in this article is divided into the analysis of authoritarian persistence and the analysis of no authoritarian persistence.

Essentially, fsQCA consists of two different procedures: the test of necessity and the test of sufficiency. The analysis of necessity comes prior to the analysis of sufficiency and assesses whether a condition or disjunctions of conditions are supersets of the outcome, meaning that the outcome cannot be achieved without these conditions. The test of sufficiency looks at whether a condition or conjunctions of conditions (conjunctural causation) are subsets of the outcome. Because perfect super- or subset relations are empirically rare, both of these tests make use of coverage and consistency parameters (Ragin Reference Ragin2006).Footnote 7 Consistency values express the percentage of cases’ membership in super- or subset relations and therefore indicate to what degree the empirical data are in line with these relations (Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012: 324). For the test of necessity, those conditions which pass the consistency and coverage thresholds are further tested for their empirical relevance (Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012: 236).

At the core of the test of sufficiency is the so-called truth-table analysis. Each row of a truth table stands for one of the logically possible combinations of conditions. Ergo, an analysis with k number of conditions has a truth table with 2 k rows. Those rows which pass the thresholds for consistency and coverage and contain one or more cases are considered sufficient for the outcome. These rows are used for the logical minimization which typically produces different and mutually non-exclusive explanations for the outcome of interest (equifinality). Those rows which do not contain any cases as empirical evidence – the logical remainders – can still be included in the process of logical minimization, yet, only based on assumptions (Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012: ch. 6). Depending on these assumptions, the conservative (no assumptions), the most parsimonious (assumptions on all logical remainders) or the intermediate (some assumptions, the so-called easy counterfactuals) solution formula is obtained.

Operationalization

Due to the general problems of data accessibility in autocracies, the analysis in this article is constrained in terms of its empirical scope and time sensitivity and thus rather exploratory in its nature. Measuring legitimation in authoritarian regimes is extremely challenging, particularly if done for a larger number of cases. While data about protests or child mortality rates and GDP growth are merely indirect measures, this analysis relies on the expert survey of Christian von Soest and Julia Grauvogel (Reference von Soest and Grauvogel2017a), which provides a first data set on legitimacy claims of authoritarian regimes. Yet the survey data is limited in terms of cases, only covers the period from 1991 until 2010 and offers observations per regime span and not per year. A second and more general constraint is that due to its combinatorial nature, the analysis in this article looks at all indicators for the hexagon at once. Because of missing values in each of these indicators, the number of cases is further limited.

The analysis refers to 62 cases of authoritarian regimes, starting in 1991.Footnote 8 One rationale for choosing this point of time is linked to the many new state formations after the fall of the Soviet Union. At first, this period of transformation in the early 1990s had been enthusiastically called a latecomer of the third wave of democratization (Huntington Reference Huntington1991). However, it soon turned out that this labelling was overly optimistic and that authoritarianism became more real again (Geddes Reference Geddes1999; McFaul Reference McFaul2002). After several stumbles and initial signs of democratization, many of the newly independent states had transformed into fully-fledged autocracies by the end of the 1990s. The second reason for choosing 1991 concerns the general transformation of authoritarianism in a post-Cold War and increasingly globalized world. Today’s dictators employ new strategies and a range of seemingly democratic practices to stabilize their rule (Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008; Schedler Reference Schedler2013). The period of the analysis from 1991 to 2010 allows me to assess the impact of these novel strategies on authoritarian persistence.

The case selection is further guided by this article’s definition of autocracy. I borrow from Barbara Geddes, Joseph Wright and Erica Frantz (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014), who propose a somewhat minimalistic definition, allowing for a clear borderline between democracies and autocratic regimes. Their comprehensive data set on autocratic regimes (1946–2010) forms the basis for the cases of my analysis.Footnote 9 The data set classifies autocracies as such if: (1) the executive achieved power by other means than fair, competitive and free elections; (2) the executive achieved power by fair, competitive and free elections but changed these rules afterwards; or (3) the military prevents compliance with these rules or changes them (Geddes et al. Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014: 317).

One key element of Geddes et al.’s (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014) data set is that, based on their definition of autocracy, they use a combination of rigorous criteria to identify clearly the beginnings and ends of autocratic regimes rather than inferring them from yearly democracy codes as is done in other data sets (Cheibub et al. Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010; Wahman et al. Reference Wahman, Teorell and Hadenius2013). Based on this, a regime end is a change of the basic rules about the identity of the leadership group which can but not necessarily has to lead to a transition to democracy. The fine-graded assessment distinguishes between intra-regime leadership successions (for example, in monarchies or Turkmenistan in 2006, coded as no regime end) and other leadership successions which also affect the composition of the leadership group at large (coded as regime end). Following Geddes et al. (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014), I code those regimes as persistent which do not end between 1991 and 2010. All regimes which end before 2010 are seen as non-persistent regimes. This means that out of the 62 cases of authoritarian regimes, 51 are coded as persistent and 11 as non-persistent.Footnote 10

The conditions for the analysis are the six core concepts of the hexagon: repression of physical integrity rights (repp), repression of civil and political rights (repc), co-optation as compensating vulnerability (coopv), co-optation as simulating pluralism (coops) and diffuse and specific support of legitimation (legd, legs). I measure the two forms of repression by drawing on Cingranelli and Richards (Reference Cingranelli and Richards2013). The names of both forms are inspired by the two main indices in their data set and make the operationalization straightforward, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 Operationalization of Repression and Co-optation

For the operationalization of the first form of co-optation, I follow Schmotz (Reference Schmotz2015) and his innovative way of defining co-optation as compensating vulnerability. Schmotz constructs a comprehensive index that looks at six different socioeconomic pressure groups (military, capital, parties, labour, ethnic groups, landowners), their individual strength and ambition to exert pressure and a regime’s capacity to compensate for these pressures by providing material benefits or institutional inclusion.Footnote 11 This measurement of vulnerability and compensation offers a new picture on co-optation in autocratic regimes and contributes to more valid results since hitherto used indices of co-optation are rather coarse, as further illustrated below.

Concerning co-optation as simulating pluralism, I refer to the Database of Political Institutions’ (DPI) indicators on competitiveness in legislative and executive elections (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Clarke, Groff, Keefer and Walsh2001). I consider those regimes as simulating multiparty systems which score in the two indicators on legislative or executive elections below 7 and above 4.Footnote 12 This operationalization of co-optation differs from previous approaches in two regards. First, I distinguish between fake and real electoral competition in authoritarian regimes and exclude the latter when measuring simulated pluralism. Recent contributions frequently refer to José Antonio Cheibub, Jennifer Gandhi and James Raymond Vreeland’s (Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010) trinomial indicator of party institutionalization when operationalizing co-optation. While the values of 0 and 1 indicate either no legislature or a legislature with members only from the regime party, the third value – 2 – stands for regimes which have multiparty legislatures. Yet this indicator does not distinguish between those regimes which allow for oppositional parties and those which merely set up satellite parties, faking a multiparty regime. Second, my operationalization of co-optation as simulating pluralism cuts across existing typologies of hegemonic and closed regimes. While non-competitive multiparty systems are seen as a defining feature of hegemonic regimes (Brownlee Reference Brownlee2009; Sartori Reference Sartori2005), operationalizations of this regime type are rather coarse and classify several regimes which simulate pluralism as closed regimes.Footnote 13

For the operationalization of both forms of legitimation, I refer to von Soest and Grauvogel’s (Reference von Soest and Grauvogel2017a) expert survey on legitimacy claims of authoritarian regimes. The survey relies on nearly 300 questionnaires completed by internationally renowned country experts, assessing six basic legitimation strategies. Table 2 lists these strategies and shows how I aggregate them to measure specific and diffuse support of legitimation.

Table 2 Operationalization of Legitimation

The survey of von Soest and Grauvogel (Reference von Soest and Grauvogel2017a, Reference von Soest and Grauvogel2017b) collects assessments of the most recent autocratic regime in a country, resulting in observations per regime span.Footnote 14 Besides the general difficulties of handling time-varying factors with the chosen QCA approach in this article (Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012: ch. 10.3), this constraint of von Soest and Grauvogel’s data further limits the time-sensitivity of my analysis and demands a meaningful aggregation of the other indicators which are based on country observations per year. When looking at the data, it is striking that several regimes have become increasingly repressive over the years of their existence.Footnote 15 To account for this crucial aspect and provide a valid measurement despite the constraints in terms of time-sensitivity, the average values for the time spans were weighted in favour of the latest regime years.Footnote 16

Calibration strategy and robustness tests

Calibration is a crucial step in set-theory methods in which set membership scores are assigned to cases. This process requires reasoned decisions on where to place the anchors which signify what full membership and full non-membership in each fuzzy set mean and where the point of indifference or crossover point should be located (Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012: 32). By combining theoretical knowledge and empirical evidence, the difference between relevant and irrelevant variation is made (Ragin 2008: 82–3).

Following these basic principles of calibration, I chose the anchors in Table 3 according to the meaning of the sets. The label ‘high repp’, for example, measures high amounts of repression of physical integrity rights. In other words, a regime which scores below the crossover point of 4.2 might still apply this form of repression – but not in high amounts. To ensure a high content validity of all sets, I checked several of the ‘borderline’ cases to see whether the assigned membership scores are coherent with the case knowledge at hand. In some cases, alternative positions of the anchors seemed equally plausible. For more substantive decisions in this regard, I conducted detailed robustness tests.Footnote 17

Table 3 Anchors for Calibration

Generally, the robustness tests illustrate that slight alterations of the anchors do not significantly change the results of the analysis. To make the choice of the crossover points more transparent, I further explain some of the more substantial tests and decisions. Concerning both forms of repression, the chosen crossover points seem rather low, classifying most cases as more in than out of the set.Footnote 18 However, moving up the crossover points – particularly for the set of ‘high amounts of repression of physical integrity rights’ (high repp) – would place regimes such as Turkmenistan out of the set. In view of the empirical evidence about the highly coercive nature of this regime (Human Rights Watch 2017), it is therefore reasonable and in line with the meaning of the set to choose a lower crossover point and accept the rather unequal distribution of the calibrated data.

As the histograms in the online supplementary material show, the distribution of the raw data on co-optation as compensating vulnerability is slightly skewed. This makes the calibration procedure an even more delicate issue. The tests of alternative anchors reveal that lower crossover points lead to model ambiguity which complicates the QCA results (Rohlfing Reference Rohlfing2015: 3). Higher crossover points decrease the content validity of the concept since all cases scoring above 0 are by definition already overcompensating (Schmotz Reference Schmotz2015: 448).

While von Soest and Grauvogel (Reference von Soest and Grauvogel2017b) propose calibration anchors for all the legitimation variables in their truth-table analysis, I changed most of these anchors for several reasons. First, the chosen crossover points by von Soest and Grauvogel are (with minimal deviations) based on the mean values of the respective base variables. While this can make sense in some instances and coincide with other reasons for choosing these locations for the anchors, the mean values should never be applied systematically when calibrating data. Such purely data-driven calibrations are flawed and can significantly diminish the content validity of the calibrated sets (Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012: 33). Second, von Soest and Grauvogel (Reference von Soest and Grauvogel2017b) refer to gaps in the raw data to justify their placements of the anchors. In general, this is a valid strategy since noticeable drops in the data can indicate relevant differences between the respective cases. Yet it is not a convincing approach if the raw data are pervaded by many gaps, as is the case for the legitimation variables. In contrast to von Soest and Grauvogel, I place the anchor of ‘high amount of foundational myths’ above 3, for example, because I argue that Myanmar (score of 3.00) only partly uses the successful struggles of independence as a source of legitimacy and should not be a member of this set.Footnote 19 In contrast to this, the experience of independence has a central role in the official narrative of the Uzbek regime (score of 3.25), which is why this case should indeed be a member of the set.Footnote 20 The adjustments of the other anchors follow similar rationales. The R scripts test and compare these anchors with those of von Soest and Grauvogel, which further highlights their robustness.

Summary of the findings

Analysis of authoritarian persistence

The test of necessity for the outcome authoritarian persistence reveals that no single condition or its logical negation passes the minimum thresholds of consistency, coverage and relevance. The test further shows several disjunctions of conditions with high consistency and coverage values. Yet all of them have low relevance values, indicating the trivialness of necessity for these logical OR combinations. The test of necessity concludes therefore with no statement on necessary conditions or combinations of them.

For the test of sufficiency, the truth table in this analysis consists of 64 rows, representing all logically possible combinations of the six conditions. Table 4 is an abbreviated form of the truth table. It contains only those rows for which there is enough empirical evidence available, meaning here that at least one case is assigned to the respective row.

Table 4 Truth Table for the Outcome Authoritarian Persistence

Note: Table 1 in the online supplementary material provides the full names of all cases in this analysis.

All rows above the consistency value of 0.77 are considered sufficient for the outcome authoritarian persistence. The rationale for determining this consistency threshold is two-fold. First, the value of 0.77 represents a gap in the consistency values, indicating a notable drop of consistency. Yet there are also other gaps before and after 0.77. On that account, the second reason is that including row 47 (consistency of 0.764) in the logical minimization process would mean including a logically contradictory case since Bangladesh is a non-persistent authoritarian regime. In contrast to this, the cases in row 64 (consistency of 0.782) are all persistent authoritarian regimes, which further suggests that this row can be seen as sufficient for the outcome.

For the logical minimization of the sufficient rows, I assume the presence rather than the absence as directional expectation for all conditions beside repression of physical integrity rights. The usage of high amounts of this form of coercion is costly and can damage the population’s legitimacy belief in the regime (Gerschewski Reference Gerschewski2013), which is why I make no assumptions for the logical remainders of this condition. Based on this, the intermediate solution formula (Table 5) is obtained.Footnote 21

Table 5 Intermediate Solution Formula for the Outcome Authoritarian Persistence

Notes: a Capital letters indicate presence, small letters absence, * denotes logical AND.

b Cov.r = raw coverage; Cov.u=unique coverage.

The intermediate solution formula has a high consistency value at 0.89 and explains 73% of all the cases which are coded as persistent autocratic regimes. By suggesting six sufficient conjunctions, it is a rather comprehensive equifinal explanation of authoritarian persistence. This is further underscored by the low unique and much higher raw coverage of each path (26 cases are covered by more than one path). The discussion section provides a detailed interpretation of this solution formula.

Analysis of no authoritarian persistence

The test of necessity for the outcome no authoritarian persistence concludes that there is no condition or conjunction of conditions which pass the consistency, coverage and relevance of necessity thresholds. The truth table for the sufficiency test of no authoritarian persistence (Table 7 in the online supplementary material) shows that no single row passes the minimum consistency threshold of 0.75 (Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012: 129). This indicates that the hexagon is not a suitable framework for explaining why authoritarian regimes break down since it cannot identify enough commonalities among the non-persistent regimes. Interestingly, the empirical test of Gerschewski’s three pillars in the context of autocratic elections comes to similar results (Schneider and Maerz Reference Schneider and Maerz2017: 223). This strongly suggests that in the case of regime failure, the interplay of repression, legitimation and co-optation has already stopped working and that there are other causal mechanisms at work.Footnote 22

Discussion

The intermediate solution formula for the outcome authoritarian persistence suggests six paths. Due to their strong overlap, I consider the last two paths as logical equivalents and summarize them to one configuration. This leads to five configurations of the hexagon. These configurations reflect the different combinations of survival strategies which keep autocratic regimes persistent. I call these configurations: (1) hegemonic, (2) performance-dependent, (3) rigid, (4) overcompensating and (5) adaptive authoritarianism.

The five configurations or ‘faces’ of authoritarianism are illustrated in Table 6. The first row of this table provides a graphical illustration of the solution formula that transfers the Boolean expressions of each path into the respective configuration of the hexagon. The hexagon functions here as a radar chart with 1 and 0 meaning the presence or absence of the sets as suggested by the prime implicants of the solution formula.Footnote 23 The ‘r’ in between these values indicates logically redundant prime implicants which might have been present before the logical minimization but were dropped from the respective solution term during the process of logical minimization due to their redundancy. As their intermediate position indicates, these aspects might be either present or absent in the respective regimes – yet, as per the results of the logical minimization, they are not needed to ensure the survival of these regimes. The second part of the table, rows 4 to 7, gives information about the type of cases covered by each path. Following Carsten Q. Schneider and Ingo Rohlfing (Reference Schneider and Rohlfing2013), the categorization into typical, most typical, uniquely covered and deviant cases facilitates a more fine-graded interpretation of the solution formula. The last row of the table contains those cases which are not covered by any paths of the solution formula.Footnote 24 These deviant cases regarding coverage would need to be analysed in explorative process tracing (Schneider and Rohlfing Reference Schneider and Rohlfing2013: 574) since their mechanisms of ensuring authoritarian persistence are not explained by the hexagon.

Table 6 The Many Faces of Authoritarian Persistence

Note: Table 1 in the online supplementary material provides the full names of all cases in this analysis.

The defining feature of the first configuration – hegemonic authoritarianism – is that it uses co-optation as simulating pluralism together with high amounts of diffuse legitimation and repression of civil and political rights.Footnote 25 In other words, these authoritarian regimes can be described by their hegemonic multiparty systems which merely pretend pluralism. This façade is backed up by intensively propagating ideologies, foundational myths or the personality of autocratic leaders and secured by strictly limiting the liberties of the population such as freedom of speech, assembly and association.

The most typical case of hegemonic authoritarianism is Uzbekistan.Footnote 26 Besides having an appalling human rights record (Human Rights Watch 2010), the regime strongly propagates an official ideology as a pre-political consensus on delicate issues such as religion and the role of the state (Maerz Reference Maerz2018). Furthermore, the regime maintains an elaborated system of satellite parties, each of them having fallacious names such as Uzbekistan’s Liberal Democratic Party or People’s Democratic Party of Uzbekistan. Particularly tricky in this regard is that although the latter party enjoyed the official support of 2016’s deceased president Islam Karimov, it is not a dominant party (Bader Reference Bader2009: 111). Thus, parliamentary elections in Uzbekistan indeed make a pluralistic impression – at least at first glance – since the parties’ share of seats is quite equally distributed (OSCE 2009). The other typical cases of hegemonic authoritarianism, most of them uniquely covered, also combine repression, diffuse legitimation and fake pluralism as their strategy of survival. However, some of them have a more distinctive dominant-party system. In Angola, for example, the ruling Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA) draws its legitimacy from the myths about the country’s war of independence and is uncontested in its predominance. The repressive regime officially tolerates other parties, yet none of them receives significant shares of seats in the elections – which are frequently accompanied by corruption, official intimidation or other incidences of fraud (Vines and Weimer Reference Vines and Weimer2009: 288). Not so obvious cases which exhibit this configuration of authoritarianism are Laos and Turkmenistan.Footnote 27 Egypt, Yemen and Syria proved to be persistent throughout the period of observation in this analysis. However, while the latter has been going through a highly entangled and cruel civil war for several years, the first two countries experienced regime changes after the Arab Spring. These cases and the regime of the Ivory Coast would need to be studied in more detail to illuminate the deviant mechanism leading to regime failure after 2010.

The second configuration of persistent authoritarianism are the so-called performance-dependent regimes due to their strong reliance on specific sources of legitimacy. Typical cases showing this configuration of the hexagon are the United Arab Emirates, Iran, Algeria or Oman – all resource-rich countries which allure their people with a good socioeconomic performance but also broadly control them by suppressing civil and political rights. Many of the performance-dependent regimes, in particular the uniquely covered Gulf states of Kuwait, Qatar and Bahrain and the most typical case of Saudi Arabia, are classical examples of rentierism (Beblawi and Luciani Reference Beblawi and Luciani1987). However, this configuration includes also China, Vietnam and Cuba. These communist regimes might have high growth rates or claim significant improvements in the field of education and health as their achievements, but they are also known for boosting non-material, symbolic or simply non-existing successes as their accomplishments (e.g. Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2015). Besides combining carrot and stick, the third defining feature of the performance-dependent regimes is that none of them greatly simulates pluralism. On the contrary, they rather divide at both extreme ends of this co-optation strategy. While some are long-running monarchies or communist states, the others do indeed allow for real electoral competition.

The most striking characteristic of the third configuration is that these regimes strongly apply both forms of repression. Following Schneider and Maerz (Reference Schneider and Maerz2017: 229), I call this configuration rigid authoritarianism. The name is based on the assumption that autocracies which are severe offenders of physical integrity rights are less flexible since their legitimacy is constantly at stake (Gerschewski Reference Gerschewski2013: 28). Furthermore, such terrorizing and intimidating methods are costly. Nevertheless, there is still a range of autocratic regimes with a rampant history of human rights violations. This configuration of authoritarianism typically includes internationally isolated regimes which are known for their extremely ruthless and brute leaders: North Korea, the military regime of Myanmar, conflict-ridden Sudan and Eritrea, also known as the North Korea of Africa (Weldehaimanot Reference Weldehaimanot2010: 232). Puzzling cases of this configuration are those regimes which allow for electoral competition (for example, Russia, Uganda or Algeria). Since the approval of even minimal amounts of competition creates significant uncertainties for the ruling elites (Schedler Reference Schedler2013), these regimes try to control such risks by using intense repression of physical integrity rights. However, this is an irrational and highly ambiguous strategy since it can easily delegitimize the regime and play into the hands of the opposition. Therefore, it is a somewhat unstable configuration of the hexagon, which nevertheless results in authoritarian persistence.

The nexus between high amounts of specific legitimation and repression of physical integrity rights constitutes another unstable but persistent configuration of the hexagon.Footnote 28 This rather counterintuitive combination of strategies is found in all those regimes – competitive or closed – which are covered by both the rigid and performance-dependent configuration. Post-QCA case studies could further reveal how these regimes nevertheless endure. In addition, a closer examination of Libya and Myanmar as those cases which turned out to be less resilient after 2010 would provide insights into the ambiguous effects of severe repression on the resilience of authoritarian regimes.

The fourth configuration is called overcompensating authoritarianism. Compared with the more parsimonious configurations of the other persistent autocracies, the regimes in this category intensively use both forms of legitimation and co-optation and thereby fritter resources, as the name of this configuration also indicates. The overcompensating configuration includes only a few cases. The only uniquely covered case – Cambodia – also uses high amounts of repression of physical integrity rights. Most of the persistent autocracies do not need to use as many strategies at once as the regimes with this configuration do. Particularly concerning the two co-optation strategies, it seems that applying both in high amounts is not needed for autocratic survival. As is the case in Cambodia, this merely promotes a kleptocratic elite (Hughes Reference Hughes2008: 71).

Adaptive authoritarianism is the last configuration of persistent authoritarianism in this analysis. These regimes are more flexible since they promote specific and diffuse support of legitimation without applying severe forms of repression of physical integrity rights (Schneider and Maerz Reference Schneider and Maerz2017: 225). Instead, they adopt and exploit seemingly democratic institutions and rely on electoral fraud, censorship and other, subtler means of limiting civil and political rights. The resource-rich countries with this configuration especially combine this ‘rule by velvet fist’ (Guriev and Treisman Reference Guriev and Treisman2015) with a sophisticated usage of the new information technologies. Kazakhstan, for example, has an impressive set of e-government websites, revealing a surprising citizen-responsiveness (Maerz Reference Maerz2016). Together with various claims to legitimacy, such tools enhance the efficiency and capacity of the regimes and thereby strengthen their resilience. Studies on typical cases of this modern form of authoritarianism could further explore such institutional manipulations that seem to replace traditional forms of coercion. Research about the deviant cases of Mauritania, Ghana or the long-running but recently failed regimes of Burkina Faso and Gambia might hint at instances in which this mechanism stops working. As mentioned, one hunch in this regard is that the intense use of both forms of co-optation is a waste of resources, which can have destabilizing effects over longer periods of time. Most of the resilient regimes with this configuration apply only one of the co-optation techniques in high amounts. Overall, the adaptive configuration might be trendsetting in modern authoritarianism; by combining one of the co-optation strategies with both forms of legitimation, these regimes are capable of largely avoiding the risks and costs of harsh repression.

Conclusion

This article classified persistent authoritarian regimes as per their strategies to survive by applying fsQCA. Based on the framework of the hexagon of authoritarian persistence, the analysis inquired about successful combinations of different strategies of repression, co-optation and legitimation. The empirical assessment of 62 regimes resulted in five configurations of the hexagon which provide novel and multifaceted explanations about why some authoritarian regimes are more enduring than others.

Based on these findings, there are several avenues for future research. The discussion of these five configurations of authoritarian persistence could merely illustrate the key aspects of the regimes’ varying survival strategies. However, following Schneider and Rohlfing (Reference Schneider and Rohlfing2013), I made detailed suggestions for post-QCA research on typical and deviant cases which would help to explore further the mechanisms of authoritarian persistence and breakdown, respectively. In addition, future studies might find better ways of operationalizing the concept of authoritarian persistence which minimize the constraints when using censored data and allow a testing of the configurations in a larger set of cases.

Apart from this, future research might operationalize alternative and more finely graded concepts to specific and diffuse support of legitimation (first steps in this direction are Dukalskis Reference Dukalskis2017; Dukalskis and Gerschewski Reference Dukalskis and Gerschewski2017; von Haldenwang Reference von Haldenwang2017). While this article used von Soest and Grauvogel’s (Reference von Soest and Grauvogel2017a) novel indicators on legitimizing authoritarianism, such innovative approaches are still rather limited in their empirical scope. Surveys among the population, particularly in those regimes which I called adaptive, could also facilitate crucial insights about legitimizing this less repressive and more flexible form of authoritarianism.

What are the broader implications of the findings illustrated in this article? Generally, the empirical test of the hexagon revealed that authoritarianism seems to get smarter and uses increasingly sophisticated methods to ensure its survival. This poses new challenges for the field of autocracy research and for the western policy community at large. In the discussion of the findings I argued that neither the exclusive reliance on both forms of repression (‘rigid’) nor the full use of all other aspects of the hexagon (‘overcompensating’) leaves persistent regimes much room for manoeuvre. While several authoritarian regimes attempt to disguise strict limitations of civil and political rights with a good socioeconomic performance, others find versatile ways to avoid the backfiring effects and high costs of severe repression and invent new methods of coercion and control. The seemingly democratic institutions of a range of contemporary autocracies – particularly the fake multiparty systems of hegemonic regimes – might have misleadingly appeared to some as first signs of democratization. However, this new trend in authoritarianism is a strong opponent to open and liberal political systems. By pretending to speak and act like democrats, modern authoritarian rulers exploit the new information technologies effectively to manipulate political discourses (see Maerz Reference Maerz2017). The shift in some authoritarian regimes from merely censoring internet freedom to proactively using social media and distorting the online public sphere with fabricated posts, trolls and electronic propaganda has only recently begun, and empirical analyses of this phenomenon are still rather scarce. Benefiting from recent progress in computational methods for the social sciences (Lucas et al. Reference Lucas, Nielsen, Roberts, Stewart, Storer and Tingley2015), the digital footprints of these new online strategies of co-optation, legitimation and repression could be systematically scrutinized. The study of such autocratic adaptations to a modern and globalized style of government would help unmask further faces of authoritarianism.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2018.17

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Carsten Q. Schneider, Matteo Fumagalli and Alexander Dukalskis for their valuable feedback and support. I am also highly grateful for the fruitful discussions with Johannes Gerschewski. I thank Julia Grauvogel, Christian von Soest and Alexander Schmotz for helpful comments and sharing their data. Any remaining errors are my own.