INTRODUCTION

St Albans, an ancient Christian site, was the location of one of six major construction projects involving the replacement of an Anglo-Saxon church undertaken by the Normans in the 1070s, within a few years of the Conquest.Footnote 1 The oldest parts of the existing cathedral are universally held to be those of the abbey church begun, according to Matthew Paris (c 1200–59), in 1077 by the first Norman abbot, Paul of Caen, and completed in just eleven years (fig 1).Footnote 2 Paul was a relative of Lanfranc, the influential post-Conquest Archbishop of Canterbury whose detailed Benedictine monastic code of c 1077 was adopted at St Albans.Footnote 3

Fig 1. St Albans abbey church, interior. North nave elevation, looking east: Photograph: Wojtek Buss, https://www.robertharding.com.

Cruciform in plan, with a crossing tower and transepts, the Romanesque church had an overall length of some 115m, and an aisled presbytery and nave of four and ten bays respectively.Footnote 4 The tower and transepts are circumscribed by internal wall passages on two levels. Both the nave and the transepts have a three-storey elevation. The arches of the middle storey in the nave are equal in width to those of the main arcade beneath, but they open into a windowless roof space rather than a tribune gallery. Excavations conducted by Professor Martin Biddle have indicated that the nave of the existing church was built above an earlier structure, thought to be late-tenth century in date.Footnote 5 The character, orientation and precise location of this earlier building remain to be established, but a centrally planned structure has been suggested.Footnote 6

THE EVIDENCE

The new evidence at St Albans comprises a masonry feature in the south transept whose significance was first noted by the author in 2017. The diagnostic detail, now concealed beneath the lean-to roof over the south nave aisle, is a blocked, round-headed opening in the west elevation of the west wall of the transept (fig 2a and b). Measuring 0.58m in width, it is located some 1.05m from the face of the pier that marks the junction of transept and nave. The masonry of the west wall is continuous, obscuring the usual prospect into the south transept below. Evidently, the blocked opening was originally a window in an external wall; only at some later point was it enclosed beneath an aisle roof (fig 3).

Fig 2a. St Albans abbey church, interior. The roof space over the south nave aisle, looking towards the south transept, west wall, west elevation. Photograph: author.

Fig 2b. St Albans abbey church, interior. Detail of fig 2a showing the blocked window.

Fig 3. St Albans abbey church: the existing building from the south west, showing the location of the blocked window in the south transept, now concealed under the south nave aisle lean-to roof. Image: Coleen O’Boyle and Helena Gomes.

Clearly visible on the north transept, high up on the external east wall, are two more blocked, round-headed windows, side by side, each roughly 0.50m wide, measured by eye from the ground (fig 4a and b). Comparable with the blocked window in the south transept mentioned above, they are level with the internal wall passage but would have been obscured by the pitched roofs that apparently covered the lost transept chapels.Footnote 7 Further south along the wall, on the same level, an opening with a width of 0.59m that would have been a third window in a sequence of three now serves as the entrance to a room contrived within the roof space over the north choir aisle. Located at a distance of 1.03m from the angle of the transept and the nave, this, the innermost of the former openings on the east wall, is in the equivalent position of the blocked window in the south transept described above. No other original windows of this kind on either transept seem to have survived.Footnote 8

Fig 4a. St Albans abbey church, exterior. North transept, east face. Photograph: author.

Fig 4b. St Albans abbey church, exterior. Detail of fig 4a showing the two blocked windows.

The newly recorded feature in the south transept at St Albans shows that the wall containing it, together with the adjacent wall of the nave, originally formed part of an unaisled cruciform structure. A similar detail is preserved at York Minster, where the thirteenth-century nave arcades are aligned with the solid walls of an unaisled church of the late eleventh century.Footnote 9 At York, not a Benedictine monastery but a house of canons, several courses of ashlar masonry and a nook shaft from the lost eleventh-century building survive in situ at the junction of the transept and the earlier nave, concealed by the lean-to roof over the Gothic north nave aisle.

Also hidden from view in the aisle roof spaces at St Albans, on the nave walls, are several large areas of grey render, scored on the surface to resemble freestone. As the roof space over the aisles was never a thoroughfare, the fictive ashlar masonry surviving at St Albans would originally have been an external feature, visible only from the ground below.

Taken together, these physical features confirm that the transept walls at St Albans originally stood in the context of a nave and presbytery that were unaisled. They also add to the likelihood that the incoming Normans reused much of that earlier standing structure.

THE PRACTICE OF REMODELLING

In the light of these new observations, it would be tempting to dismiss Matthew Paris, our source for the history of the Norman work at St Albans, as a late and unreliable witness for failing to mention that Abbot Paul had repurposed an old church, rather than built a brand new one. Matthew’s use of ‘reaedificavit’ to describe Paul’s work, however, might well imply that Paul had ‘rebuilt’ the church, on the same spot.Footnote 10 At all events, a little over a decade after the Norman Conquest, it seems that the decision was taken to convert the old church of St Albans into an aisled building: a pair of outer walls would have been constructed along the length of the solid nave, supporting lean-to roofs to enclose the new aisles. Next, a series of tall arched openings would have been cut out of the old nave walls at regular intervals. The existing sequence of massive nave piers would have been fashioned from the saved masonry between the openings.Footnote 11 Equipping the inherited building with aisles was clearly a priority, whereas incorporating serviceable tribune galleries was not.

The diagnostic feature in the south transept presented here was not a chance discovery but the product of a dedicated enquiry, prompted partly by anomalies in the standing building that have always called for clarification. For example, although the Norman presbytery was aisled, its walls were solid rather than pierced by arcades. The central vessel in the presbytery was therefore isolated from its flanking aisles. By way of explanation, it has been argued that the solid walls of the presbytery were destined to support a masonry vault over the central space.Footnote 12 Whether such a scheme was ever carried out in the Romanesque building is uncertain, but that has no bearing on a notional reconstruction of the aisleless church, given that its presbytery walls would, by definition, have been solid.

Another striking feature of St Albans is the somewhat crude character of the interior masonry compared with that produced in Normandy at a similar date, but equally in England. Its rather rough-hewn appearance and lack of carved ornament have, however, provoked little comment hitherto.Footnote 13 Presumably the absence of fine finish has been tacitly attributed to the relative speed with which the Anglo-Norman church is said to have been constructed, or to the documented reuse of Roman building material.Footnote 14 Implicit in this is a slightly condescending assumption about the essential primitivism of Romanesque, sidestepping the vexed question of quality but distorting the historical reality, nevertheless; according to the present reconstruction, the Romanesque masons, charged with remodelling and extending St Albans at speed while retaining much of its standing fabric, responded with imagination and skill. That the process seems to have led to some loss of refinement has passed unremarked.

The quest above ground for an earlier building at St Albans was also inspired by a growing body of research indicating that aisles were quite commonly added to unaisled naves in the post-Conquest period, most readily detectable in minor buildings.Footnote 15 At St Michael’s in St Albans, where a church of that dedication is recorded in the mid-tenth century, aisles were added to the nave towards the end of the eleventh.Footnote 16 Openings were punched through the solid Saxon walls of the small building to create arcades. The considerable width of the internal splay of the windows relative to the small size of the openings on the exterior at St Michael’s is characteristic of the Saxon period, and particularly noteworthy in connection with the nearby abbey church of St Albans, apparently remodelled and given an aisled nave at around the same time.

Systematic remodelling of this kind evidently also took place in the twelfth century in larger churches, notably those occupied by communities of priests.Footnote 17 At Worksop Priory, Nottinghamshire, regular canons were installed in an existing parish church sometime after 1119.Footnote 18 Although there are no discernible remnants of an older ‘recycled’ structure in the present aisled nave, the priory’s massive pair of western towers, which appear to be part of an integrated design, are not contemporary with the aisled nave they abut. As at St Albans, the dark middle storey of Worksop’s nave opens into an unlit roof space, in this case above nineteenth-century century aisle vaults.Footnote 19 There is no architectural connection between these roof spaces and the western towers at Worksop. Instead, access to the top of the vaults is gained, rather awkwardly, via a rectangular window-like opening on the east face of the towers. Now concealed beneath the lean-to roof over the aisle vaults, they would originally have been visible on the exterior and were probably designed as bell openings. When first built, Worksop’s western towers evidently flanked an unaisled nave.Footnote 20 The solid walls of the nave could have been ‘knocked through’ in the twelfth century to create the openings for the arcade, as argued for here at St Albans, inserting columnar supports at Worksop, rather than retaining masonry to form the piers. The lowest stage of each tower at Worksop would have been opened up internally to form the westernmost bay of the nave aisles.

THE ENCASED SPIRAL STAIR

An intriguing and unusual feature at St Albans is the spiral stair housed inside the fifth columnar pier of the north nave arcade (fig 5a and b). The staircase is not visible from the nave and its presence is seldom mentioned in modern accounts of the building, probably because a free-standing pier with an integral spiral stair, mid-way in the nave arcade of a building with aisles and wall passages, serves no obvious purpose.Footnote 21 The staircase appears to have been entered originally at ground level, via the west face of the fifth pier through an arched opening, now sealed but preserved in outline. Parallels are understandably rare; the spiral stair of c 1045 inside the south-west crossing pier of Bayeux Cathedral may well have contributed to the weakening and eventual collapse of the tower there.Footnote 22

Fig 5a. St Albans abbey church: plan (James Neale, Reference Neale1877) Image: Conway Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London.

Fig 5b. St Albans abbey church: detail of Neale’s plan, showing the north nave pier 5 containing the spiral stair ringed in red.

The stair at St Albans is only accessible today from the north aisle roof-space (fig 6a). From there it evidently led upwards but the descent was obstructed at some stage by a masonry blocking. It is reached from the roof space via an arched opening with a width of 0.65m, centred in a pilaster buttress that is 1.70m wide and projects 0.58m from the wall plane (fig 6b).Footnote 23 According to the simple reconstruction proposed here, this buttress was originally an external feature rising up the nave wall of the earlier unaisled building and subsequently cut back below when the aisle was added. The opening giving access to the stair has a modern door, but appears not to have been rebated and has clearly been remodelled. It is suggested here that the staircase itself pre-dates the aisled Anglo-Norman building and that the arched opening now leading into it was originally an external window, lighting the staircase.

Fig 6a. St Albans abbey church, interior, north nave aisle roof space: the buttress containing the entrance to spiral staircase within pier 5. Photograph: author.

Fig 6b. St Albans abbey church, interior, north nave aisle roof space: the entrance to the spiral staircase within pier 5. Photograph: author.

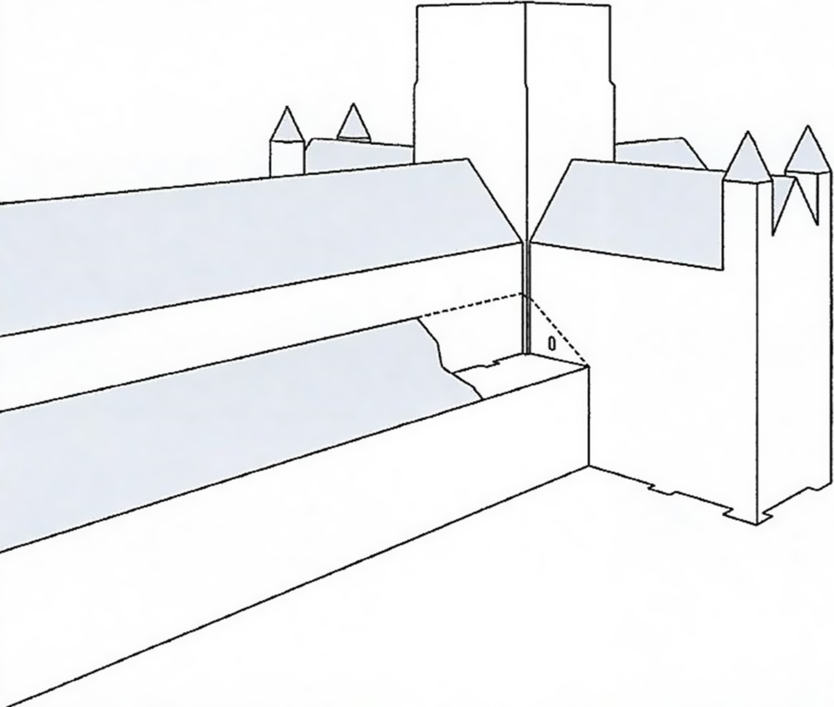

The stair at St Albans has features in common with the few surviving Anglo-Saxon spiral stone staircases, such as the columnar newel comprising dressed stone drums occurring in Lincolnshire at Broughton and Hough-on-the-Hill, and treads composed of several separate stones in each case, as at Brixworth, Northamptonshire.Footnote 24 If the stair at St Albans was indeed retained from the previous unaisled church, what purpose had it served there? Perhaps one of a pair of corner turrets representing the westernmost extent of that older building, it may have been refashioned as a nave pier for the aisled Anglo-Norman church (fig 7). A pair of western stair turrets has been notionally reconstructed at mid-tenth-scentury aisleless and cruciform St Pantaleon in Cologne, whose solid nave walls were also subsequently knocked through to connect with new aisles.Footnote 25 The stair turrets at St Pantaleon served a westwork, but there is no indication of anything comparable at St Albans.

Fig 7. St Albans abbey church: notional reconstruction of the earlier aisleless cruciform church, seen from the south west. Image: Coleen O’Boyle and Helena Gomes.

THE DATE OF THE AISLELESS CRUCIFORM CHURCH AT ST ALBANS

If, as is argued here, Romanesque St Albans is effectively an architectural palimpsest, a monumental sarcophagus incorporating the fabric of an older church, how old was that earlier structure? How did it relate to Abbot Ealdred’s aborted mid-eleventh-century building project?Footnote 26 If, as seems likely, its solid nave walls were knocked through to create the aisled Romanesque church, when did that take place? And if, as has never been questioned, Paul of Caen was responsible for constructing the existing Romanesque church after 1077, did the remodelling described here occur during his abbacy? If Paul added the aisles, the unaisled building must surely be earlier in date than 1077, but by how much? If, however, the features of the older building are not deemed to be pre-Conquest, what revised date should be assigned to the existing Romanesque church?

The claim that the remains of the aisleless cruciform church at St Albans are pre-Conquest necessarily implies that the putative rebuilding project conducted by the Normans involved a great deal more than simply adding aisles, including, for example, rebuilding the upper part of the transept walls in order to accommodate wall passages. While the salient crossing with clearly defined corners at St Albans would not be hard to place in England in a pre-Conquest context,Footnote 27 the height of the crossing arches certainly would. However, Matthew Paris records the installation of new bells in the tower (Turrim campanis instauravit) under Abbot Paul, a measure that might well have entailed some structural remodelling.Footnote 28 That the crossing tower at St Albans is apparently of brick construction, rather than the reused brick and flint masonry used elsewhere in the church, confirms that it was substantially part of the Normans’ new work.

The reconstruction offered here proposes a pre-Conquest aisleless nave at St Albans with a length of some 33m, measured from the junction of nave and transept to the pier containing the stair. This dimension is considerable but it need not weigh against a pre-Conquest date, given the nave of over 45m calculated at mid-tenth-century Canterbury Cathedral.Footnote 29 Other aspects of St Albans that might cast doubt on a possible Saxon date, always assuming they and the aisleless nave are contemporary, include the passages contained within the wall thicknesses. Wall passages, skilfully exploited in Norman architecture from about the second quarter of the eleventh century, are only likely to have been deployed in England in conjunction with Norman patronage. Their occurrence at St Albans apparently in the same context as the small blocked windows in the transepts – judged here to form part of the older aisleless church – would appear to argue strongly against a pre-Conquest date for that earlier building. It is not clear, however, that the wall passages and the small blocked windows at St Albans are indeed contemporary. The original windows do not illuminate the transept wall passages now and may never have done so; it is possible to argue that the windows predate the quintessentially Norman passages and were blocked during the Romanesque remodelling. In the nave, the average excavated wall thickness was a substantial 1.98m (6.5 feet).Footnote 30

The wide-arched openings in the middle storey of the nave, glazed in the fifteenth century, resemble those of a fully-fledged Romanesque tribune gallery. They can equally be seen as enlargements of much smaller pre-Conquest clerestory windows which, as at nearby St Michael’s in St Albans, were usually already far wider internally than on the exterior. A dark middle storey, opening into the space above the aisles as at St Albans, rather than into a gallery supported by vaults, seems to be one of the hallmarks of a converted structure.Footnote 31

Sizeable cruciform churches with aisleless naves were not such a rarity in pre-Conquest England, it seems. Anglo-Norman York no longer appears idiosyncratic beside Worksop and St Albans. Other elusive early churches may likewise stand entombed within the structure that replaced them: did the continuous inter-columnar masonry excavated in 1930 at Westminster Abbey that puzzled Alfred Clapham represent the solid nave walls of the Saxon minster?Footnote 32 Could the pre-Conquest minster at York, its whereabouts still uncertain, be embedded in the fabric of the present cathedral? Were the ‘connecting walls’ of the nave piers spotted in the foundations of St Albans by J C Buckler, the vestiges of its aisleless nave?Footnote 33

WHY BUILD AISLES?

Nikolaus Pevsner’s assertion that churches built in England before the middle of the eleventh century rarely had an aisled nave is sweeping but not unreasonable.Footnote 34 Regardless of its precise date, the aisleless cruciform church at St Albans represented an ancient building type, alleged to have been the preserve of clerical communities rather than Benedictine houses, up until the early twelfth century.Footnote 35 The Early Christian iconography of the aisleless cross-shaped church was transmitted by Carolingian epigraphers from Lombardy to Lorsch,Footnote 36 then a familiar milieu for Anglo-Saxon scholars,Footnote 37 although whether they bore the cruciferous imagery back to Britain must remain a matter for speculation. The second half of the tenth century saw the promulgation of the reformed Benedictine rite among the secular religious houses of England, a measure that was only partially effective and did not provoke a wave of church building.Footnote 38 St Albans was itself refounded as a Benedictine monastery in that period, but was nevertheless not rebuilt at that point.Footnote 39 By the late eleventh century, however, Benedictine monasticism was in the ascendant;Footnote 40 post-Conquest England had, moreover, witnessed a dramatic building boomFootnote 41 and the proliferation of a distinctive new architecture, as testified by the Anglo-Norman historian William of Malmesbury (1080–1143).Footnote 42 It may be significant, however, that William, keen-eyed commentator on church building in England, makes no mention of Abbot Paul’s new work at St Albans.

Romanesque St Albans epitomises the seismic impact of the Norman Conquest on England: as the physical manifestation of the displacement of the secular clergy by Benedictine monasticism in the second half of the eleventh century,Footnote 43 as an example of the way that an ancient building type could be speedily reconfigured for monastic use and as a demonstration of the processes by which the Normans introduced the innovative architecture of mainland Europe into their new off-shore kingdom. Among the defining characteristics of this new architecture, now called Romanesque, was the systematic creation of aisled structures.Footnote 44 The benefits of providing a church with aisles are considerable, such that the resilience of the – liturgically awkward – aisleless cruciform building type can only be ascribed to the tenacity of its iconographic tradition. Adding aisles to a nave increases the area, fenestration, impact and potentially the height of a building, and relatively cheaply. In England, the overwhelmingly post-Conquest phenomenon of aisled architecture was, if not directly inspired by the reinvigorated Benedictine rite with its emphasis on liturgical processions, as described in Lanfranc’s monastic regulations of c 1077, quite possibly a response to it;Footnote 45 an aisled nave facilitated circulation around a church, without encroaching on a sanctuary located at the crossing.

This paper gives a brief outline of a new observation. A full-scale investigation into the Romanesque abbey church at St Albans and its ‘above-ground archaeology’Footnote 46 may lead to a better understanding of the character and probable date of the aisleless cruciform building brought to light here.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am most grateful to Bob Allies, Richard Griffiths, Matilde Grimaldi, Neville Scott and Jean-Irène Pinzelli for assisting in various ways with the preparation of this paper, part of a talk given for the British Archaeological Association (BAA) in London in November 2018. I wish to thank the BAA for that opportunity and for similar instances in the past, and also the Society of Antiquaries and Lavinia Porter for supporting the present publication and providing expert referees. My thanks to Coleen O’Boyle and Helena Gomes for producing the reconstructions of the cathedral with great patience and skill. I’d also like to record my deep appreciation of the work of Professor Eric Fernie and Dr Richard Gem, leading British exponents of medieval architectural history of their generation. This paper develops the theme of my PhD by publication,Footnote 47 supervised by Professor T A Heslop, itself the culmination of decades of pondering the phenomenon of the aisleless cruciform church. The particular lines of enquiry pursued here, as well as the conclusions reached and any errors committed, are my own.