Introduction

International Health Disaster Response Programs (HDRP) such as foreign medical teams and field hospitals are presumed to be expensive.1-Reference VanRooyen, Hansch, Curtis and Burnham5 The evidence supporting this assumption is limited—are these interventions being compared to non-disaster interventions or to each other? What is the appropriate health metric in disasters, and should the costs of these interventions be measured? If it is possible to measure costs and outcomes, why isn't this measurement undertaken?

There is a growing demand that international health programs be both effective and provide good value for the money.Reference Murray, Anderson and Burstein6-Reference Schieber, Gottret, Fleisher and Leive11 Major international donors such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and the Gates Foundation, along with World Health Organization (WHO), academic groups and non-government consortiums, have generated documents, metrics, new departments, and coalitions in an attempt to improve both the effectiveness and the efficiency of health aid.12, 13 Measuring health outcomes with metrics in some form of cost utility analysis (CUA), such as cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), has become an increasingly important component in the assessment of health interventions.Reference King and Bertino14-Reference Hutubessy, Chisolm and Edeger16

For health-oriented disaster programs, it would seem relatively easy to collect data on cost and impact. After all, these are often unique programs that require funding, and tracking outcomes is a common medical practice. The short duration might be expected to make it easier to track funding and outcomes than for programs with long timelines.

The relative paucity of literature concerning costs, outcomes, and “economic health metrics” of HDRP may have many reasons. These vary from the difficulty in collecting and analyzing the data, institutional issues for aid organizations, ethical issues regarding CUA in general, and, most importantly, whether disasters have unique aspects that may make CUA either inappropriate or impossible to assess.

This last issue is critically important if donors become more obsessed with utilizing CUA for funding. This study will review the concepts of CUA as they relate to HDRP, consider the specific difficulties applicable to performing CUAs in disaster situations (Table 1), and discuss the relevance of CUA to HDRP. Finally, this study will utilize previously published articles that have performed a CUA for HDRP, or given enough information to prove that it is possible to make these calculations. Consideration will be made as to the future role for CUA for disaster response.

Table 1 Difficulties applicable to performing CUAs in disaster situations

Report and Discussion

Definitions

An appropriate starting point for this analysis is to be clear on the utilization of terms. Most all health metrics utilize a fraction; the numerator is the cost of an intervention and the denominator is some measure of benefit to the recipient population.Reference Baltussen, Adam and Tan-Torres Edejer17, Reference Murray, Evans, Acharya and Baltussen18 The most common health metric is Cost Effective Analysis (CEA), which, for developing nations and injury in general, is usually expressed as United States Dollars (US $) per Disability Adjusted Life Year (DALY).Reference James and Foster19-Reference Lopez, Mathers, Ezzati, Jamison and Murray21 The DALY is the sum of Years of Life Lost (YLL) plus Years Lived with Disability (YLD). YLL are calculated as life expectancy (either ideal or a regional/local) minus the age at death. YLD are also calculated in the same manner, but are adjusted for a Disability Weighting, expressed on a 0 to 1 scale, with 1 being a year spent in perfect health.Reference Jamison, Breman and Measham20-Reference Murray and Acharya23 With discounting, but uniform age weighting, a newborn's potential YLL is approximately 30, a 30-year-old's is 26, and a 60-year-old's is approximately 17.Reference Mathers, Salomon, Ezzati, Begg and Lopez24

The methodology is extensively documented elsewhere.Reference Fox-Rushby and Hanson22, Reference Mathers, Vos, Lopez, Salomon and Ezzati25, Reference Murray and Lopez26 In brief, various states of health were ranked relative to each other in multiple focus groups, to develop a presumed preference of health states. As an example, a foot or leg amputation has a DALY of 0.300, but a finger is 0.102.Reference Mathers, Bernanrd and Iburg27

Hundreds, if not thousands, of studies have been performed using CUA to assess public health interventions, many of them in the international setting. Immunization programs often appear to be the most economical, with programs claiming numbers around under US $10/DALY.Reference Bradt28, 29 At the other end of the spectrum, open heart surgery in the United States is greater than US $5,000/DALY.29 While there are many criticisms of the methodology and assumptions of this approach, the DALY remains the dominant health metric for CEA in the developing world, and commonly is used to compare various interventions.

Cost-Effective Data Collection and Analysis in Disaster Response

Studies of CUA often have methodological problems.Reference Drummond and Sculpher30-Reference Neumann, Zinner and Wright37 One difficulty is generating the appropriate total for costs in the numerator. Guidelines have been published, discussing such relevant issues as start-up costs, allocation of program costs, and the utilization of expatriate staff.Reference Drummond and Jefferson34, Reference Evans, Edejer, Adam and Lim38, Reference Baltussen, Adam and Tan-Torres Edejer39 This last issue is very significant for disaster programs that utilize expatriate staff; their cost should be calculated at the actual cost. If they are volunteers, then the cost is considered to be zero.Reference Drummond and Jefferson34 “Opportunity costs” of their lost wages have typically not been included in calculations.

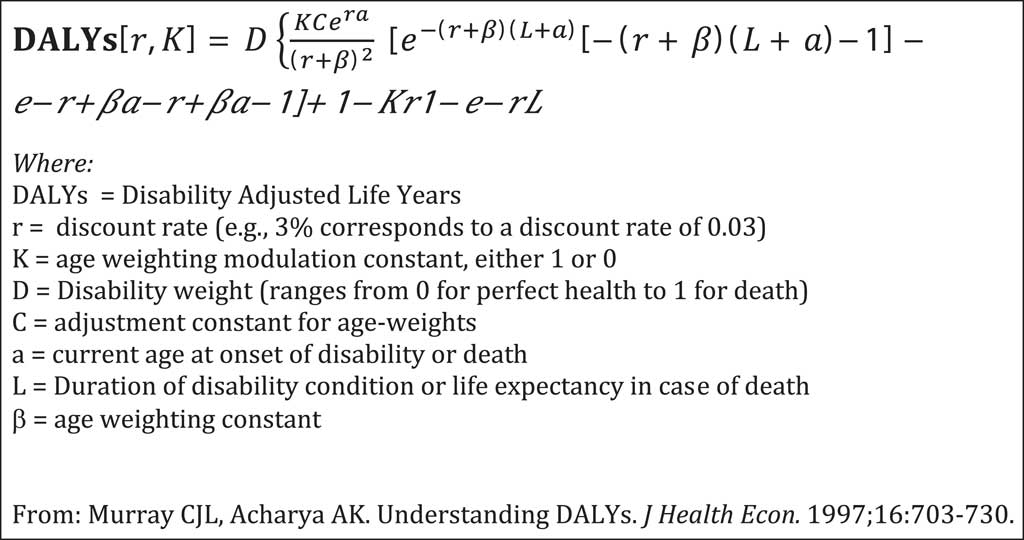

Calculation of the denominator, the DALY (YLL plus YLD) also may be difficult. One problem is the number of assumptions required to generate the constants for the formula. These include how to value money over a life expectancy (discounting), what is an appropriate life expectancy, and what is the relative value of life at different ages (“age-weighting”). All of these assumptions lead to an onerous-appearing mathematical formula (Figure 1).Reference Murray and Acharya23 Fortunately, the formula may be reduced to a calculation for Excel spreadsheets (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington USA).Reference Fox-Rushby and Hanson22

Figure 1 Formula for calculation of DALYs

Attempts have been made to standardize the assumptions required for the CEA calculations,Reference Baltussen, Adam and Tan-Torres Edejer17 but, acknowledging that there continue to be differences in assumptions used, prominent peer-reviewed medical journals generally have asked that authors document the assumptions made, rather than dictating which to use.Reference Jefferson and Demicheli31 Most articles appear to agree on the use of discounting cost over time at a 3% rate, and most seem to discount life-years in the same manner. But there is variation in the use of age weighting between the original concept of non-uniform age weighting, and of uniform age weighting; the former places slightly higher value on the years lived at the middle portion of life.Reference Mathers, Salomon, Ezzati, Begg and Lopez24 The more recent WHO recommendations are to use uniform age weighting, but with discounting (Table 2).Reference Baltussen, Adam and Tan-Torres Edejer39

Table 2 Uniform and non-uniform age weightingFootnote a

a Adapted from Mathers et al,24 with 3% discounting

Another controversial point is what potential life span is to be utilized.Reference Arnesen and Kapiriri40-Reference Mathers, Murray and Lopez42 The original studies chose an optimal life span of 82.5 years for women and 80 years for men, but these numbers may not be realistic for impoverished communities. Accordingly, there are now regional numbers that may be used.Reference Arnesen and Kapiriri40 As discussed above, as long as the assumptions used are documented, data can be considered with or without discounting and/or age-weighting.

Directly relevant to a disaster response is the need to have sufficient outcome information to make the calculations. Without outcome information, one cannot compare the intervention to the “null” or “counterfactual,” i.e., if the intervention had not occurred at all. While it may be tempting to think that disaster care is of a certain benefit, many times there is an over-supply of providers, and sometimes it appears that the organized intervention made little or no impact.Reference Von Schreeb, Riddez, Samnegård and Rosling2, Reference De Ville de Goyet4

An example would be the incremental value of an additional field hospital following the Bam Earthquake.Reference De Ville de Goyet4 If the assumption is made that the response was the only resource for an intervention, especially for traumatic injuries, the outcome calculation and subsequent YLL and YLD calculations should be straightforward, and any limitation would be due to poor data collection and a lack of planning. If a program is so shortsighted that outcomes cannot be followed, perhaps the intervention itself should be questioned.43-Reference Roy, Shah, Patel and Coughlin45

Institutional Issues for Aid Organizations

While the concept of providing beneficial care to the recipients in an efficient manner is commonly accepted, presenting actual numbers creates the potential for ranking programs based on efficiency. In turn, this may make less “efficient” programs less likely to be funded, creating a competitive environment. This may not be in the global interests of the aid agencies or the beneficiaries.Reference Proudlock, Ramalingam and Sandison46

Organizations may also be concerned about the vast number of assumptions that go into the calculations, and the great variety in incurred costs calculation methods, which can differ according to time, place, and accounting procedures. CUA is difficult within a single organization, and likely inaccurate if used to compare among organizations and activities. The pursuit of effectiveness also has been criticized as discouraging innovation among aid organizations.Reference Harvey, Stoddard, Harmer and Taylor9 The difficulties in accounting are not unique to disaster response, and it is generally accepted that small variations in cost/DALY probably do not mean much. However, when the costs/DALY differ by a power of 10 or 100, they are much more likely to be meaningful.29

Disaster needs assessments are extremely difficult to complete for the initial response, and are usually based on limited knowledge. Accordingly, it would seem punitive that well-meaning interventions cause an organization to be labeled as “inefficient” if adequate productivity could not be calculated. Other have stated that the efforts expended in generating budgeting and compliance calculations are not justified by the benefits.Reference Natsios47

Those organizations that rely on “technical experts,” or expatriate staff paid at home nation rates, will likely find this significantly impacts their CUA,Reference Gosselin, Maldonado and Elder48 and may be even more resistant than those who utilize national staff. On the other hand, for foreign aid in general, this practice has been criticized,Reference Gosselin, Maldonado and Elder48-Reference Herfkens and Bains50 and poor performance in CUA may be an appropriate criticism for HDRP.

Additionally, the argument could be made that the outcomes measurable by DALYs are only one part of the value of HDRPs, and that the apparent efforts in the curative services may be significant in showing solidarity to the affected nation,Reference Robertson, Bedell, Laveru and Upshur51 with the potential to lead to quicker recovery. Multi-faceted international aid groups may view their disaster programs as entrées to future humanitarian programs, essentially “loss-leaders.” Another value that is not captured by health metrics is the potential value of teaching and examples. An International Urban Search and Rescue Team may not have saved many lives, but it may inspire an affected nation to develop its own local teams, which have a greater likelihood for future success.

Ethical Issues

Ethical arguments about the utilization of CEA in general are common,Reference Anand and Hanson52-Reference Brock59 and, of direct relevance to HDRPs that often take on a very utilitarian approach,Reference James and Foster60 there is a perspective that such a “utilitarian” or “Consequentialist” approach is inconsistent with humanitarian perspectives.Reference Robertson, Bedell, Laveru and Upshur51, Reference James and Foster60 However, if one accepts that most disaster response is based on utilitarian concepts of doing the greatest good for the greatest number,61 then this seems to be a weak argument against CUA.

Unique Aspects of Disasters

CUA typically has been used as a measure for interventions for a population. Most commonly, there is some specific health issue for which there is accumulated information about incidence and prevalence, and about the cost of intervention. Additionally, estimations must be made about the potential utilization and outcomes of the intervention. This information allows an estimation of total cost, or changes in cost from prior interventions, that becomes part of a “sectoral” analysis for the health sector, and “informs” potential allocations of a fixed budget.Reference Hutubessy, Chisolm and Edeger16, Reference Baltussen, Adam and Tan-Torres Edejer17 This approach has aspects of a zero sum concept, i.e., funding for one project must come at the expense of another. However, if it is assumed that funds for each disaster are raised separately, and do not come from the overall moneys available for international health, this may be a significant reason not to compare disaster response funding to other potential international health programs.

Disasters may have some common issues, but vary in many unpredictable ways. The unique aspects of disasters lead to specific issues with calculation of CUA (Table 3). Early in a disaster, it is difficult to know what acute needs are, and what resources remain capable of providing them. This makes the counterfactual, not doing an intervention, very hard to calculate.

Table 3 Unique issues in disasters

Additionally, there is only one set of global disability weights, but the significance of various disabilities is not comparable across cultures and societies.Reference James and Foster19, Reference Ustun, Rehm and Chatterji62-Reference Reidath, Allotey, Kouame and Cummins64 In an affluent society, one might become an amputee following a painless resection for vascular problems or a tumor; be given general anesthesia in the operating room and adequate post-operative pain medication, and receive a well-fitted prosthesis and disability payments from the government. Following an earthquake in a developing nation, one might lie in excruciating agony in rubble for several days, be dragged out by neighbors, receive an amputation with local anesthesia, have no post-operative pain medication, face a long wait for a poorly fitted prosthesis, and live in a hilly town with potholes. Both disabilities have a disability weighting of 0.300. It is far easier to be blind in New York or London than in the Sudan, but the DALY does not account for that.Reference Reidath, Allotey, Kouame and Cummins64, Reference Zou65

While there are many ethical issues regarding CEA, one of particular relevance to disasters is the suggestion of thresholds, that is, the value at which an intervention is cost-effective.66, Reference Eichler, Kong, Gerth, Mavros and Jonsson67 The Council on Macroeconomics has developed thresholds for “attractiveness” of interventions, ranging from “very cost-effective” for interventions that cost less than the Gross Domestic Product (GDP)/person to “cost-effective” for interventions costing less than three times the GDP/person.Reference Eichler, Kong, Gerth, Mavros and Jonsson67 Implicit in this is that interventions costing more than three times the GDP are not cost-effective. This would seem an extra burden for the poorest countries to bear, especially if a region has just had its local domestic product reduced to zero by a disaster.

Using Cost Utility Analysis for Health Disaster Response

Despite all of the above barriers, Gosselin, Gialamas, and Atkin demonstrated in 2011 that a CUA of an HDRP could be calculated when they reviewed a trauma response to the Haiti Earthquake.Reference Gosselin, Gialamas and Atkin68 Their calculations demonstrated a CEA of $343/DALY averted.

For HDRPs, there are no other publications to compare the above numbers to, but there is data that can be utilized to generate some approximations. One set of data comes from von Schreeb, who reviewed multiple field hospital deployments, with estimation that a field hospital daily bed cost is approximately US $2,000 per day.Reference Von Schreeb, Riddez, Samnegård and Rosling2 If one uses an approximation of 3.5 days as the average stay,Reference Fernald and Clawson69 the cost per patient per occupied bed would be US $7,000. If this saves the life of a young person, it would avert about 30 DALYs (discounted), or be valued at US $233/DALY averted. This estimation will be affected by occupancy, and the true disability weightings of procedures occurred, and also by the counterfactual (if no field hospital equals no care). If occupancy is averaging 50%, a value of US $466/DALY is calculated, and the typical patient is a leg amputation, the cost per DALY becomes over US $1000. These numbers are very inexact, but they show a general range of hundreds of US $ per DALY.

Another approximation could be generated using the data available from the Fairfax, Virginia USA Urban Search and Rescue Team in Haiti.Reference Macintyre, Barbera and Petinaux70 They recorded 15 rescues who survived, one of whom received an amputation. Assuming that their follow-up data is accurate, and that all would have died without their intervention, their efforts averted 383 DALYs. The costs are not entirely obvious; past United States Agency for International Development costs for an international USAR team have been approximately US $2 million.71 Utilizing that number (and ignoring the costs of the French team which assisted on multiple rescues, and the cost of patient care following the rescues) generates a CEA of US $5,221/DALY. This may represent either a relatively poor value, or be one of the situations where the international social and political significance of demonstrating solidarity, assisting a transition to recovery, and potential education is worth the investment.

Conclusion

With all the above limitations, CUA of HDRPs can be performed, and doing so more often will add to the body of scientific knowledge. Costs that are reasonably close or even a multiple of two or three may not be very significant, but if the CUA of a program differs in magnitude from that of others by a power of 10, 100, or even 1000, that merits attention.

There are a vast number of reasons that CUA may be distasteful to the humanitarian community. Those who champion CUA never have claimed it was perfect, nor have they suggested that CUA be the sole determinant of any program; it is suggested that CUA be utilized to “inform.” Decisions may also depend on many other factors, including ethical, social, cultural, political and budgetary.Reference Baltussen, Adam and Tan-Torres Edejer17, Reference Murray, Evans, Acharya and Baltussen18, Reference Chapman, Berger, Weinstein, Weeks, Goldie and Neumann72-Reference Shillcutt, Walker, Goodman and Mills74

Despite the complexities of using CUA for disaster response, it is possible to perform the required calculations, and a common metric should not be rejected without further analysis and consideration. It may be that the Global Burden of Disease project is an inappropriate tool for disaster evaluation, and needs modification for disaster response, but the field of disaster research has not demonstrated that. Research in this area should expand to evaluate which health metrics to use, and how to use them.

Abbreviations

- CEA:

Cost Effective Analysis

- CUA:

Cost Utility Analysis

- DALY:

Disability Adjusted Life Year

- GDP:

Gross Domestic Product

- HDRP:

Health Disaster Response Programs

- US:

United States

- WHO:

World Health Organization

- YLL:

Years of Life Lost

- YLD:

Years Lived with Disability