1. Introduction

Online fanFootnote 1 communities and fan sites are home to many different fan works, perhaps the best known of which in language learning circles is fanfiction (Sauro, Reference Sauro2017). These are stories that reinterpret, reimagine, and remix the events, characters, settings, and ideas found in popular media and elsewhere. Fanfiction encompasses a wide range of genres (e.g. romance, mystery, coming-of-age stories) and text types (e.g. short stories, novel-length stories, graphic novels), including some that develop out of common fan tropes or draw upon practices specific to a particular group of fans. For instance, a common fanfiction trope that can be found across many different fandoms is the Coffee Shop Alternate Universe (AU) trope: fanfiction in which the characters from a book, movie, or television show are reimagined as employees in a local coffee shop (for an extensive discussion, see Three Patch Productions, 2016). An example of a fandom specific genre can be found in the Sherlock Holmes fandom: 221Bs are short stories of exactly 221 words, the last of which must begin with the letter B in homage to the apartment number, 221B, where Sherlock Holmes and John Watson lived on Baker Street.

Another well-known type of fanfiction particularly common among novice writers in many fan communities and which has been the focus of research in applied linguistics is Mary SueFootnote 2 fanfiction. This is a type of fanfiction where the author inserts him- or herself into the universe and story alongside favorite characters. Leppänen’s (Reference Leppänen2008) investigation of Mary Sue fanfiction by young Finnish fans showed how these teenage girls used author-insert fanfiction to explore and confront issues and pressures facing them in offline Finnish society.

Although fanfiction is the subject of a great deal of research in the field of fan studies, within applied linguistics research on fanfiction has been more limited and has predominantly taken the form of case studies that have explored the linguistic and identity development of English language learners (see, e.g., Black, Reference Black2006; Thorne & Black, Reference Thorne and Black2011). These studies have identified practices such as the use of author’s notes that accompany stories to disclose information about the writers’ offline identities to negotiate the kind of feedback they were open to receiving on their stories (Black, Reference Black2006) or as a way to connect themes and language use in their writings with their interests, personal beliefs, and language backgrounds (Thorne & Black, Reference Thorne and Black2011).

Only recently has research begun to look at the use of fanfiction as a model for pedagogical tasks for the teaching of languages in formal classroom contexts. This can be seen in the work of Sauro and Sundmark (Reference Sauro and Sundmark2016), who explored the incorporation of a task-based fanfiction project into a teacher education course for future secondary school English teachers at a university in Sweden. The use of collaborative blog-based fanfiction was found to effectively bridge the concurrent teaching of language and literature to these advanced learners of English and to simultaneously serve as a model for the type of teaching tasks these future teachers could use with their own students.

Taken together, these studies of fanfiction in applied linguistics have incorporated an assumed role for technology and language teaching and learning. For instance, Black’s (Reference Black2006) and Thorne and Black’s (Reference Thorne and Black2011) participants used the online fanfiction website https://www.fanfiction.net to publish their stories. Due to the publication format for stories on this fan site, these second-language (L2) writers could make use of the author’s notes, a section where writers can provide background or comment on their stories and communicate with potential readers, each time they published a new story or chapter. Technology also assumed a less visible but relevant role in Sauro and Sundmark’s (Reference Sauro and Sundmark2016) collaborative fanfiction project, which required the publication of the resulting stories on communal or individual blogs.

Although technology has been present and arguably crucial for the language development or identity work of these learners, the manner in which technology has mediated language learning and use around fanfiction has itself not been explored. In addition, studies of learner fanfiction have not investigated the degree to which fanfiction for L2 learning compares with other fanfiction found in the digital wilds. This present study therefore sets out to explore these intersecting issues, which have the potential to mitigate the efficacy of computer-mediated tasks that bring linguistic and digital practices from the digital wilds into the language classroom.

2. Literature review

The call to bridge the digital and linguistic practices of the language classroom with the practices of L2 users outside the classroom reflects an understanding that continuity between the in-class and out-of-class technology-mediated target language use may better facilitate teaching with CALL by, for example, minimizing the amount of time teachers and learners must spend learning how to use the technology. Beyond such practical considerations, however, looking to out-of-classroom digital practices can also aid our understanding of how technologies may work with or against our own learners’ linguistic and digital competences, thereby guiding the integration of technology into the design of teaching activities. This is what González-Lloret and Ortega (Reference González-Lloret and Ortega2014) argue for in their call to ensure that a needs analysis in a technology-mediated task-based curriculum accounts for the learners’ digital literacies relevant to the technological tools needed to complete the tasks. Looking to the concepts of extramural English, bridging activities, and affordances can help us examine and guide attempts to bridge the digital wilds with the language classroom.

2.1 Extramural English and the online informal learning of English

Extramural English (EE) is a type of “out-of-school” language learning (Benson, Reference Benson2011) that describes the myriad English-mediated activities L2 learners of English (often children and adolescents) engage in voluntarily out of school both with and without the conscious intent to learn English (Sundqvist & Sylvén, Reference Sundqvist and Sylvén2016). It includes watching films and television, listening to music, reading books, playing video games, and using social media for interaction and information sharing, all of which are common fan practices. EE therefore also includes the online informal learning of English (OILE), also known as apprentissage informel de l’anglais en ligne (AIAL) introduced by Toffoli and Sockett (Reference Toffoli and Sockett2010) in their exploration of the online English practices of non-specialist students of English in France. Longitudinal systematic analysis has been used to document specific strategies and learning processes that emerge among intermediate and advanced learners of English engaged in the online informal learning of English in French contexts (Sockett, Reference Sockett2013).

In Sweden, the context of this study, research on school-aged learners (Sundqvist & Sylvén Reference Sundqvist and Sylvén2012) found a positive relationship between EE and OILE in the form of digital gaming in English and English vocabulary, reading, and listening skills as measured on national exams. Subsequent studies found learning advantages for both primary (Sundqvist & Sylvén, Reference Sundqvist and Sylvén2014) and secondary school pupils (Sundqvist & Wikström, Reference Sundqvist and Wikström2015) who engaged in frequent digital gaming in English compared to less frequent gamers and non-gamers. More directly related to fan practices, case studies of L2 learners of English engaged in EE in the form of fanfiction writing (Black, Reference Black2006; Thorne & Black Reference Thorne and Black2011), fan page design (Lam, Reference Lam2000), or amateur translation of comics (Valero-Porras & Cassany, Reference Valero-Porras and Cassany2015, Reference Valero-Porras and Cassany2016) have also documented the informal out-of-class language and identity development of youth and young adults (Thorne, Sauro & Smith, Reference Thorne, Sauro and Smith2015). Work on EE, in particular, that focuses on fan-practices and language learning suggests a potential area for developing tasks and activities that can bridge out-of-school and in-school digitally enhanced language practices.

2.2 Bridging activities

Bridging activities are types of pedagogical activities put forth by Thorne and Reinhardt (Reference Thorne and Reinhardt2008) to address the various needs found among advanced language learners. They argue that bridging activities incorporate student-selected texts that provide “vivid, context-situated, and temporally immediate interaction with ‘living’ language use” (Thorne & Reinhardt, Reference Thorne and Reinhardt2008: 562), which serve to provide real-world contextualized examples that balance out more prescriptive and decontextualized grammar, vocabulary, and style typically found in foreign-language course textbooks. This includes, for instance, the paucity of materials focused on language and language awareness at more advanced levels, the long-standing divide between language and literature instruction (Paran, Reference Paran2008), and a disconnect between the texts and genres found in the language classroom with the digitally mediated texts and genres supported by Internet communication, online communities, and platforms, and which are increasingly relevant to language learners’ lives. Bridging activities can therefore be highly relevant for linking EE, OILE, and new media literacies, including those fostered by online fan communities, in contexts where a great deal of digital media or popular culture consumption may regularly take place in English (see, e.g., Hult, Reference Hult2010, for an examination of the presence of English-language programming on domestic television channels in Sweden).

Fanfiction tasks can potentially serve as bridging activities; specifically, they can allow for the incorporation of texts selected by students (i.e. students involved in online fan communities may draw upon existing fanfiction, fan analysis, or other popular cultural texts as inspiration for their writing choices) to help guide their transformation of elements from an existing literary text into a new story that retains both linguistic and literary elements from the source text. In this way, fanfiction tasks modeled on the fanfiction genres found online can also bring new media literacy practices into the classroom.

2.3 Affordances

The concept of affordances originated in psychology to account for an animal’s behavior in response to aspects of its environment (Gibson, Reference Gibson1977). As van Lier (Reference van Lier2000: 257) explains from an ecological perspective toward language learning, an affordance is not a property of an environment itself but rather “the relationship between properties of the environment and the active learner”. When applied to new literacy practices such as those found in social media platforms and online communities, affordances have been defined as “what is made possible and facilitated, and what is made difficult or inhibited” (Bearne & Kress, Reference Bearne and Kress2001: 91). This definition has been further broadened to include perceived affordances (Norman, Reference Norman1990) to draw upon users’ own knowledge, experience, and social practice with digital tools (Lee, Reference Lee2007). In other words, the action of students (active learners) using various social media platforms brought into the language classroom through bridging activities such as online fanfiction tasks (e.g. uploading of a video to a blog or use of tags to organize or comment on social media posts) will reflect the prior knowledge and experience of the students and teacher.

Within online fan spaces, fans’ knowledge and perception of the characteristics of different social media platforms can be seen in the different types of interaction and creative works found there. Petersen’s (Reference Petersen2014) examination of fan interaction on the blogging platform Tumblr is one such example. Among the creative fan interactions that she analyzed was a highly performative visual response to a question posed to a Sherlock fan account run by two cosplayers – fans who dress and perform as their favorite characters. Instead of producing a textual reply, the account owners took advantage of Tumblr’s very visual nature to act out their response in the form of captioned photos of themselves dressed as Sherlock Holmes and John Watson interacting with each other. Such a creative visual reply therefore drew upon not only the characteristics of the blogging platform that supported the uploading of images, but also their own experiences and socialization as members of a Tumblr-based online fan community. Their perceived affordances of Tumblr’s image upload feature might be very different from those of other Tumblr users or users of other blogging platforms. Differences in perceived affordances hold implications for language learning and language use when online fan tasks are brought into the language classroom, reflecting Kern’s (Reference Kern2014) observation that use of technology, digital or otherwise, to communicate requires mastery, but that mastery is not uniform across all users and across all communication contexts. In light of EE, OILE, and the varied experiences and socialization around digital tools and communication technologies that language learners bring to the classroom, bridging activities such as fanfiction tasks may result in new texts that are vastly different from those seen outside the classroom.

This study therefore examines the digital texts generated during the first two years of an ongoing project involving fanfiction tasks imported from the digital wilds and brought into the advanced language classroom to explore how such texts compare to those found in online fandom and how technology and learners’ experience with this technology may have mediated the resulting texts.

As this two-year iteration reflected the initial stages of an ongoing fanfiction project (entering its sixth year in 2018), these first two cohorts represented an opportunity for needs analysis that captured both digital and linguistic needs and abilities of students to better refine the instructions and teaching for future years. In order to capture the intersection of technology and language, two different research questions guided this study:

1. In what way does the use of blogs mediate the storytelling of classroom fanfiction?

2. How do classroom fanfiction texts compare with fanfiction texts found in online fan spaces?

3. Methodology

To answer the questions guiding this study, multiple sources of data were collected and analyzed. This included the blog-based fanfiction stories (n=31) completed during the two years of the project, the reflective essays (n=122) submitted by students who finished the course, an interview with a focus group of participants (n=6) representing both fans and non-fans, and a comparison mini-corpus of authentic fanfiction stories (n=18) based on The Hobbit and published to Archive of Our Own (Ao3) during the same time frame as this project.

3.1 Participants

The Blogging Hobbit fanfiction project described in this study was a language and literature task-based assignment (Sauro & Sundmark, Reference Sauro and Sundmark2016) in a course on teaching literature, required as part of an English-teacher education program at a Swedish university. The course is taught entirely in English and is taken by students in either their first or second year of study in a five-year program preparing them to teach English at lower- and upper-secondary school. As a result, students enrolled in the course range from high intermediate to advanced proficiency in English (B2–C1 on the CEFR). The fanfiction stories, blogs, and reflective papers analyzed here were collected from the 2013 (n=55) and 2014 (n=80) cohorts.

To solicit a student perspective on the experiences, volunteers from the full 2014 cohort were sought to participate in focus group interviews. The volunteers who came forward (n=6) formed one intact group whose 16,000-word story was the longest produced in either cohort and who chose to publish their story in Ao3 instead of on a blog. Although it would have been ideal to have volunteers from other groups, the Dream Team consisted of both fans and non-fans (see Table 1) who were close to members of other groups who had been less enamored of the assignment. Their involvement thus provided insights into both what made their group successful and what did not work for other less successful groups.

Table 1 The fans and non-fans on the Dream Team

Of these six members, two, E and M, represented fans of The Hobbit, the source text. Two others, B and F, openly embraced their fan identities but were fans of other media or objects and things, whereas the remaining two members, K and L, did not identify as fans or strongly rejected the fan identity despite also being active consumers of popular English-language media.

3.2 Tasks and texts

3.2.1 Collaborative role-play fanfiction

The collaborative fanfiction task that the students completed was modeled upon real-world online role-play fanfiction, often carried out in community blogs or discussion boards, in which each player contributes portions of a story from a particular character’s perspective (Sauro, Reference Sauro2014). Although there are many different subgenres of fanfiction, this particular type works best with source texts that are rich in characters (e.g. the many witches, wizards, and magical creatures of the Harry Potter books), giving players a wide variety of different personalities and possibly dialects to choose from. The text required for this course, JRR Tolkien’s fantasy novel The Hobbit, is also one that is rich in characters, creatures, and species and therefore lent itself to this type of character-based collaborative storytelling.

Students self-organized into groups of three to six, individually selected a character from whose perspective they would write, and worked together to identify a missing moment (e.g. what certain characters were doing just before or just after a major event in the novel) from The Hobbit in which to situate their story. Such missing-moment character-based storytelling required students to pay careful attention not only to the dialect and speech style of their particular character but also to other plot points within The Hobbit to ensure that their missing moment fit within the events of the novel (Sauro & Sundmark, Reference Sauro and Sundmark2016).

Those in Cohort 2013 were instructed to post their completed fanfiction to a blog and were provided with guidelines to do this as well as an authentic blog-based piece of fanfiction based on Harry Potter as a potential model. Drawing on feedback from Cohort 2013, Cohort 2014 was allowed a wider range of online publishing options in addition to blogs, including fanfiction sites and social networking sites.

The resulting 31 completed fanfiction stories ranged in length from 2,000 to slightly over 16,000 words. Of these, 24 were published on blogs, most using Wordpress or Blogger. Of the seven remaining, two were published as public Facebook groups, three were published on Ao3, and two were published in other online publishing formats.

3.2.2 Reflective papers

In addition to the collaborative fanfiction, students were asked to write individual reflection papers on the collaborative writing process, the linguistic and literary choices they made in their writing, and how such fanfiction writing tasks did or could support the development of reading, writing, listening, and speaking skills in English. The 122 reflection papers submitted were anonymized and analyzed according to cohort.

3.2.3 Real-world fanfiction

To enable comparison of the students’ fanfiction with real-world fanfiction based on The Hobbit, a mini-corpus of texts published on the fanfiction site Ao3 was compiled. The following criteria, drawn from Sinclair (Reference Sinclair2005) regarding the compilation of specialized corpora, were used in the selection of online fanfiction for this comparison corpus:

1. To ensure homogeneity of fanfiction genre and source material, only fanfiction based on The Hobbit and considered canon-compliant was included. Canon compliance is a fandom term used to describe fanfiction that attempts to remain faithful to the storyline, characterizations, and context of the original source material. Although the degree of adherence to the source material is a continuum, canon-compliant stories on Ao3 exclude those that are tagged as “crossover” (i.e. fanfiction that merges different source material; e.g. where the heroes from The Hobbit suddenly encounter the villains of the Harry Potter books) and “alternate universe” (i.e. stories that imagine the characters in an entirely different setting, such as characters from The Hobbit working in a coffee shop in New York).

2. To match genre, only completed works of fiction of similar length to the classroom fanfiction (2,000–16,000 words) were used. This eliminated novel-length fanfiction and incomplete works in progress or works of non-fiction.

3. The date of texts was also considered. Thus only fanfiction published during the duration of The Blogging Hobbit (November 2013 to January 2015) was included. This was done to account for the influence of the Peter Jackson Hobbit films released during the same period, which, according to many of the reflective papers, were influential to both fans and non-fans who wrote fanfiction for the assignment.

4. Another genre issue considered was that of romance. As none of the stories submitted for The Blogging Hobbit dealt with romance, only fanfiction tagged as “gen” (the term for non-romance stories used on Ao3) was used to eliminate fanfiction whose focus was primarily on opposite-sex (i.e. “het”) or same-sex (i.e. “slash”) romance.

5. To also account for genre, only stories rated as appropriate for teen or general audiences were included. This excluded fanfiction depicting extreme violence or erotica on Ao3.

The resulting reference corpus of online fanfiction consisted of 18 stories totaling 92,760 words. The target corpus of learner fanfiction consisted of 31 stories totaling 172,911 words. Comparison was conducted using keyword analysis, a type of statistical analysis used to identify key words, words that occur “with unusual frequency in a given text” (Scott, Reference Scott1997: 236) or target corpus, in comparison to its frequency in a reference corpus or text.

4. Results and discussion

The following results and discussion are organized according to the two research questions guiding this study that asked (1) how technology mediated the collaborative fanfiction texts produced by advanced language learners, and (2) how classroom fanfiction compared to fanfiction found in online fan spaces.

4.1 The influence of technology

The results reported in this section address González-Lloret and Ortega’s (Reference González-Lloret and Ortega2014) call for incorporating a technology needs analysis into technology-mediated task-based language teaching. A full needs analysis incorporating the digital practices of the first cohort (Cohort 2013) was not possible as we did not have access to the students prior to the start of the course. However, the experiences and feedback of the students in Cohort 2013 served as a needs analysis for the modification of the type of technology used and instructions made available to Cohort 2014 to better reflect this population’s digital practices and experiences. Thus the students’ own references to technology in their reflective papers along with visual analysis of the final published fanfiction were primary in answering this question.

4.1.1 Battling the blog

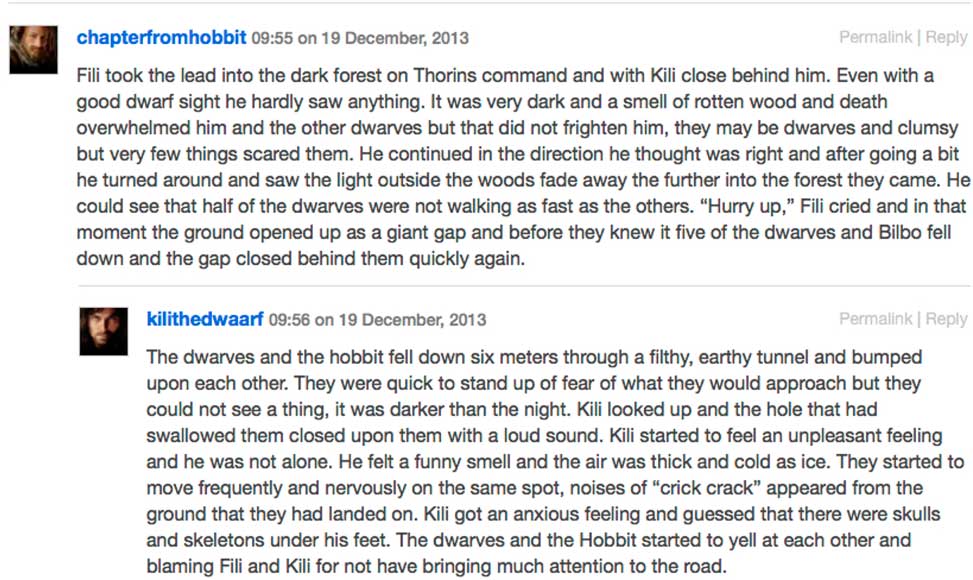

A recurring theme among a segment of Cohort 2013 was the frustration the students felt when trying to convert their stories to fit into a blog format. For several groups, this was due to the fact that although they were regular readers of blogs, they had never published in a blog before and therefore found themselves struggling with depicting the parts of their stories in the order they were meant to be read. At the same time, students had to find a way to reconcile the publishing and sharing of a story written by multiple authors in a manner that highlighted which student was voicing which character. The students had been presented with an example of blog-based fanfiction in which the storytelling took place in response in the comments to blog posts. This format allowed for linear reading of a story from top to bottom comments while also highlighting the shifting points of view and authorship. However, only one of the 12 groups made similar use of comments to facilitate storytelling (see Figure 1). A second group chose to post their story in a single blog entry and indicated the authorship by including in parentheses the author’s initials after each paragraph. These choices, while foregrounding linear storytelling and author credit, meant that this second group entirely avoided many of the characteristics of a blog, instead treating it as a static web page to be read from top to bottom.

Figure 1 Student fanfiction that made use of the comments section to support chronological storytelling

The remaining groups, however, posted the various parts to their story as separate blog posts, which resulted in frustration for a few. As one student observed, the main downside was that their story was suddenly backwards – in other words, because blog posts appear in reverse chronological order, this meant the completed stories that were posted in the order they were written had to be read from bottom to top. However, the members of this group included students who embraced this blogging feature, arguing that a blog is supposed to be a journal. They kept this reverse chronological order, arguing that although it was hard to fit the story into this sort of format, it helped them learn more about publishing in blogs and made them feel more technologically up to date and more prepared to use blogs in their own future classrooms.

Other groups, however, attempted to find ways to make use of the various affordances of a blog to facilitate chronological readability. One common strategy, illustrated in Figure 2, was the numbering of blog posts in the title to help guide the reader through the passages in the order they were meant to be read. One group in particular also made use of the customizability of the blogging tool WordPress to facilitate their storytelling through the creation of numbered linked chapters in the header bar (see Figure 3). As a result, regardless of the order in which the chapters or entries to the story had been published, a reader could easily read the story in chronological order or any other order they chose.

Figure 2 Use of numbered segments to guide readers through the story posted in reverse chronological order to a group’s blog

Figure 3 Use of linked numbered chapters in the header bar of a WordPress blog to guide readers

Although the use of the affordances of the WordPress blogging tool by this group may reflect what one would expect of proficient blog users, their strategy to facilitate storytelling was unique among the cohort. Analysis of the published stories and the comments supplied by students in their reflective papers suggest, therefore, that for many students, their limited experience with blogs posed a challenge to the presentation of their completed fanfiction and potentially the readability of their stories.

4.1.2 Exploiting the affordances of familiar online sites

In response to feedback from students in Cohort 2013, the following year, students in Cohort 2014 were given a wider range of publishing options: in addition to publishing to blogs, they could publish to other social media platforms or to actual fanfiction sites (e.g. Ao3 and fanfiction.net). Of the 19 groups, 12 chose to use blogs, three chose to publish in online fanfiction archives, two created public Facebook groups, and two published in experimental spaces with restricted or temporary access. Perhaps as a result of being given a choice, compared to the prior cohort, there were far fewer references to frustrations around the use of blogs or technology in particular in publishing their stories.

What this suggests is that allowing students to choose a publishing option was more likely to result in groups selecting a tool with which they were more familiar and therefore able to customize for the purpose of storytelling and reading. This could be seen in the final blogs of two groups who utilized the ability to embed multimedia in their blogs to reinforce their storytelling. As discussed in Sauro and Sundmark (Reference Sauro and Sundmark2016), many of the students’ fanfiction posts incorporated riddles, rhymes, and songs, in part because these were common literary devices used by Tolkien in The Hobbit. These two groups recorded themselves performing the songs found in their stories and embedded or linked to the videos of their performance in their blogs, thereby providing a visual and aural illustration to a portion of their story as well as a means for displaying their oral English abilities (see Figure 4 for an example).

Figure 4 A fanfiction blog with embedded video of the performance of a song from the story

Despite the greater facility with blogs demonstrated by members of Cohort 2014 compared to Cohort 2013, some students strategically chose to publish on a different platform for the purpose of readability and connecting to a greater audience. Such was the case with the focal group in this paper, the Dream Team, who were one of three groups to publish their story in an actual fandom space: the fanfiction archive, Ao3. According to one member, the decision to not use a blog was driven in part by how annoying it was to read due to the backwards format:

Our story is so much better looking. Yeah, because when you have, like, this blog post, it comes, like, the first is at the bottom and then you have to read up. And that was, like, really annoying when I looked at the other groups. Because I read most of the other groups, but shut some of them down after, like, okay, now I can’t handle this anymore. Exit. Exit. No. (E, Dream Team Interview)

He also pointed to additional affordances of Ao3 that friends had introduced him to and which made publishing fanfiction there more attractive. This included the ease of navigating through different parts of the story as well as the ability to convert the story into a format that could be read offline:

So you could, like, jump and skip to chapters and so on. And you could do this whole thing at once. And I had, like, friends who, like, could, what’s it called, print it and, like, have it in booklets. Because they have that function, that digital function. (E, Dream Team Interview)

The Dream Team’s familiarity with fandom, fan spaces, and fan sites similar to Ao3 were therefore crucial in their choice to not publish in a blog and to instead publish in a fan archive to support readability of their story both online and offline (i.e. in pdf format). A further motivation was their goal of reaching a broader audience beyond their classmates and teachers, something they knew to be more likely to happen in a fandom space than in a stand-alone blog. For the members of the Dream Team, reaching a broader audience would justify the extensive time and effort put into a class assignment and give their writing greater purpose. Once again, drawing upon their familiarity with online fan spaces and fanfiction, they expressed a desire to respect the fandom they were contributing to by writing a story that respected the material: according to L, “since we were actually going to publish it for fans, I thought, at least for my bits, well, I think all of our bits, there was a certain sense of respect towards the fandom that you didn’t want to, like, disgrace it with poor material.”

However, at the time of their interview, their story had received 500 views or hits and nine kudos (similar to a “like” on the social media platform Facebook) but no comments. The lack of comments, either positive or negative, was taken as a sign that their story did not entirely meet fan expectations with respect to both content and also format. As L observed after comparing their completed story to others on Ao3, “Compared to other fanfiction stories on Ao3, ours had, we had a lot of chapters and, like, pretty short texts. And it was kind of harder to read, in my opinion, than if it was one flowing text since it was so very segmented.” In other words, despite their familiarity with different fandoms and fan practices and experience with online fanfiction sites, the structure and segmenting of their story may not have matched the norms expected of fanfiction in The Hobbit fandom on Ao3 that they intended to reach.

However, another disconnect that may have limited fan interest in the Dream Team’s and other groups’ fanfiction may have stemmed from literary and linguistic differences between classroom fanfiction and fanfiction native to online fan spaces, which leads into the second research question.

4.2 Classroom fanfiction vs. fanfiction from online fan spaces

To answer the second research question, which asked how classroom fanfiction compared to online fanfiction, critical perspectives from self-identified fans in the class as well as tools from corpus stylistics, a growing field that incorporates tools from corpus linguistics into literary analysis (Culpeper, Reference Culpeper2009), was used.

Drawing upon her own extensive familiarity with fanfiction texts in other fandoms, B speculated that the Dream Team’s story, and the collaborative fanfiction of the other groups, did not resonate with fans because the classroom fanfiction did not innovate or explore fantasy and alternate scenarios in the way much popular fanfiction does:

I think people who publish fanfics that get really popular, they kind of answer to some kind of fantasy that people have about the characters. Or something they really want to explore or they create an alternate universe, so they use the characters where something really kind of exciting happens … We didn’t have anything like that, really. I mean, I think ours was very, kind of, it was very much like the book in a way, so maybe it wasn’t as exciting as some other fanfiction because it wasn’t innovating in that way. Because we weren’t trying to like this, we were trying to make it look like it could actually be a part of the book. So I think that’s the difference as well between what we did and we planned and what’s on fanfiction forums. (B, Dream Team Interview)

What B describes as “trying to make it look like it could actually be a part of the book” reflects the specific task directions required by the assignment as a way to encourage careful attention to both language form and narrative techniques in order to meet course goals (Sauro & Sundmark, Reference Sauro and Sundmark2016). In requiring students to write from the perspective of a particular existing character from The Hobbit, including capturing the speech style and personality of their character in their story while collaboratively constructing an episode that fit within the events of the source text, the assignment instructions explicitly steered the classroom fanfiction away from the alternate fantasy territory that B found characteristic of successful, well-read online fanfiction that attracted high readership and comments.

To explore B’s hypothesis further, the classroom fanfiction was compared with a reference corpus of online fanfiction from Ao3 that was published at the same time as the fanfiction for Cohorts 2013 and 2014 (see section 3.2.3). These mini-corpora were analyzed using keyword analysis, a corpus-based analysis that looks for words that occur “with unusual frequency in a given text” (Scott, Reference Scott1997: 236) and enables the identification of the most significant differences between two corpora. This was augmented by identification of negative keywords – that is, words that are unusually infrequent in the target corpus compared to the reference corpus (Culpeper, Reference Culpeper2009). Both of these analyses were carried out using AntConc Version 3.4.1m for Mac (Anthony, Reference Anthony2014). Analysis of the keywords and negative keywords in context was then used to identify differences in character, topics, writing style, and even literary techniques between the classroom fanfiction and the online fanfiction. The top 20 keywords and negative keywords in descending order of keyness, with frequency of occurrence in parentheses followed by the keyness measure (log-likelihood), are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Keywords and negative keywords in classroom fanfiction with Ao3 fanfiction as reference

Comparison of the top 10 content lexemes in both fanfiction corpora reveals that there were indeed commonalities between the classroom fanfiction and the online fanfiction. Specifically, four character names appeared in both lists (Thorin, Bilbo, Kili, and Fili), suggesting that the student fanfiction tended to feature characters who were also popular in online fanfiction. Similarly, the lexical verb say occurred in both lists, indicating its frequent use in dialog in both types of fanfiction. In addition, the word time was also in the top 10 for both types of fanfiction and was frequently used to reference the passing of time on a quest or a historical period.

Looking to the keyword analysis, the first difference to emerge concerns the other focal characters in the two different types of fanfiction. The source text, The Hobbit, follows a group of 13 characters, most of whom are dwarves, on a quest that brings them into contact with different species and magical creatures. We see eight of these characters represented in the 20 positive keywords in the classroom fanfiction texts: one wizard (Gandalf), one shape-shifter (Beorn), three dwarves, (Balin, Dori, and Bombur), one elf (Elrond), one mysterious creature (Gollum), and one hobbit (Bilbo). Among the negative keywords are four different characters, three of whom are elves (Thranduil, Legolas, and Tauriel), with the fourth being a dwarf (Bifur). This points to different focal characters in the two sets of fanfiction texts: the classroom fanfiction focused more on the characters taking part in the quest, especially dwarves, as opposed to characters encountered along the way, particularly elves. These differences can be seen in the excerpt from one of the classroom fanfiction stories produced by a group in Cohort 2013, “Down in a Hole,” as shown in Figure 1. This particular excerpt captures several characteristics common to many of the classroom fanfiction stories, including perspectives from multiple different characters, all of whom are dwarves, and third-person description of the setting and the quest in which the characters find themselves, and the other characters present in this particular missing moment of the story.

More specifically, however, a closer look at the negative keywords offers support to B’s hypothesis that online fanfiction tends to be where fans innovate to explore fantasies about certain characters in some kind of alternate universe. Of the three names of elves among the negative keywords is one that refers to an original female character not present in the text of The Hobbit but created for the Peter Jackson’s film adaptations as a way to incorporate a more visible female presence. Similarly, the other two elves, Thranduil and Legolas, are unnamed in The Hobbit though they have a visible presence in the Peter Jackson adaptation and are referenced in later books written by Tolkien concerning the same universe. Writing about these three elves, therefore, represents an innovation to the original story and one which online fans willingly explored in their own fanfiction. However, by adhering closely to the characters of Tolkien’s original text, as they had been instructed to do, the writers of the classroom fanfiction did not explore more innovative characters or connections between The Hobbit and Tolkien’s other books or the Peter Jackson films.

Stylistically, another key difference also emerged: character perspective. Among the 20 positive keywords are three that indicate a collective or group focus to the stories: we, our, us. In contrast, among the negative keywords are four singular pronouns suggesting a lesser emphasis on individual characters: she, her, his, he. The collective focus of the classroom fanfiction reflects in part the fact that each story was written by multiple authors and from multiple characters’ perspectives, something generally less common in online fanfiction. In addition, in working to depict a missing moment from The Hobbit, many of the classroom fanfiction stories maintained elements of the group quest. The shift in perspective and group quest are illustrated in the excerpt that follows in the transition between two characters’ perspectives in the story “The Missing Pages Thorin Wishes That No One Had Found” from Cohort 2013:

Balin turned towards the sound and oh did his heart skip a beat as he saw the heads of Thorin and Kili, struggling to stay above ground.

Meanwhile, back at the camp the others were resting and anxiously wondering about their friends in the woods. As waiting for food can feel like the longest wait in any time or day, Dori pulled out his flute and gave it a whistle, both to entertain the others but also to keep his mind focused on the notes in his head rather than the troubles surrounding them.

Thus, although readers of the online fanfiction were more likely to experience the adventures and experiences, not always quest related, of one or possibly several characters from a single point of view, the classroom fanfiction asked readers to experience events or a quest, tightly linked to the existing narrative of The Hobbit, and affecting groups of characters from multiple characters’ perspectives. These shifting perspectives were sometimes depicted with smooth transitions, as indicated in the above example, but in other cases, these shifts were indicated by chapter or section breaks, leading the classroom fanfiction to look more segmented than the online fanfiction, a quality that L had identified in the Dream Team’s story compared to the fanfiction found on Ao3. The shifting perspective and segmented nature of the collaborative fanfiction may therefore have given the classroom fanfiction a less cohesive look and feel than readers of online fanfiction might be used to.

5. Conclusion

This study set out to investigate the bridging of the digital and linguistic practices of the language classroom with the practices of L2 users outside the classroom through the use of fanfiction tasks. It investigated how the technology and learners’ experience with this technology may have mediated their storytelling experiences. It then examined the digital fanfiction texts generated by these advanced English language learners to see how they compared to similar fanfiction found in online fandom.

For some students, unfamiliarity with publishing in blogs affected the potential readability of their published stories; however, other students were able to take advantage of blogs’ various characteristics such as sequential comments to a blog post, a linked list of chapters in the header bar, or embedding of multimedia to illustrate songs written as part of the fanfiction. Other groups drew upon their knowledge of fandom to publish in online fandom archives instead of in blogs. Through input and observation of the first cohort of students, the technological side of the tasks was revised or expanded to better reflect the out-of-class technology experiences and preferences. In this manner, work with Cohort 2013 provided a form of necessary technology needs analysis (González-Lloret & Ortega, Reference González-Lloret and Ortega2014).

As input from the focal group of students in Cohort 2014 illustrated, in very large classes like this one with 80 to 100 students, there will inevitably be some who will have engaged with fanfiction and blogs (or any other online text or digital platform that might be a resource for a bridging activity) and some who will not. Collaborative groups that consisted of students with different levels of experience can allow for support in both the writing of the stories and use of the different aspects of the technology. Revision of the instructions in response to student input in their reflections and observation of the completed blogs allowed for refinement of the support and instructions and digital publishing options to better capture the needs and experiences of both types of students.

Comparison of the classroom fanfiction with online fanfiction identified a number of similarities, particularly with respect to several focal characters. Key differences included a focus on certain other characters, especially those who participated in the quest depicted in The Hobbit, and a greater use of first-person plural pronouns and multiple characters’ perspectives that resulted in more segmented stories than was typical in the online fanfiction. These differences were influenced in great part by the task directions, which required that the classroom fanfiction be written in groups and that each student write from the perspective of a different character, so that the resulting classroom fanfiction texts adhered more closely to the source text, The Hobbit, than did similar fanfiction found online in the wild.

Taken together, these findings suggest that future fanfiction projects should be designed to allow students greater freedom in their selection of online publishing tools and formats that reflect both their communication goals and their prior experiences. In addition, revising fanfiction task instructions to allow greater flexibility and inventiveness may potentially lead to classroom fanfiction that more greatly resembles online fanfiction and that may also serve to connect the advanced language classroom with online fan communities through feedback and comments on stories. Such changes may lead to more engaging, cohesive, or innovative stories that may reach more authentic fan audiences, influencing the motivation, interest, and language use of students and thereby better bridging technology-mediated language learning in the classroom with the EE learning engaged in by L2 learners of English in online fan spaces.

As a tool for bridging the teaching of both language and literature in the advanced L2 classroom (Sauro & Sundmark, Reference Sauro and Sundmark2016), online fanfiction tasks such as the one described here also represent a rich area for further exploration in both advanced language teaching and teacher training. Future directions concern which aspects of collaborative writing may be helpful in the teaching of literature as well as the relationship between fan identity (or non-fan identity) and its impact on participation in and subsequent learning through fanfiction tasks.

Ethical statement

In keeping with the guidelines put forth by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet), informed consent was secured from participants. Accordingly, the reflective papers and fan fiction stories written by students who did not give consent were excluded from analysis. The focus group interview and data analysis were carried out only after the conclusion of the course and grades had been assigned.

Shannon Sauro is Associate Professor of Applied Linguistics at Malmö University, Sweden, co-editor with Carol A. Chapelle of The Handbook of Technology and Second Language Teaching and Learning (Wiley-Blackwell, 2017), and past president of the Computer-Assisted Language Instruction Consortium (CALICO). Björn Sundmark is Professor of English at Malmö University, Sweden, where he teaches and researches children’s literature. He is the current editor of Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature and a member of the Swedish Arts Council.