7 Folksong arrangements, hymn tunes and church music

In his 1934 essay ‘The Influence of Folk-song on the Music of the Church’, Vaughan Williams argues for an alternative history of church music, one in which the long-standing influence of folk and popular traditions on church musicians and their compositions is given its due. In his view, the impulse to attribute musical works to the authorship of known composers had obscured general knowledge of this influence, and he sets out in the essay to put the record straight. At one point, observing that the famous Passion Chorale ‘O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden’ originated as a parody of the early seventeenth-century German love-song ‘Mein G’müth ist mir verwirret’, he challenges Franz Böhme’s opinion that the original song was composed by Hans Leo Hassler in 1601. Noting that Hassler’s version ‘has all the appearance of a folk-song’, he asserts that ‘it is quite possible that Hasler [sic] only arranged it. Such things were quite usual in those days before the modern craze for personality set in.’1

The remark neatly encapsulates beliefs that the composer held dear – the idea that art and popular musical traditions have long been interdependent, and the related notion that composers throughout the centuries have drawn on local popular musics as a source of artistic inspiration, and should do so again. Somewhat unexpected, though, is the implied criticism of Romanticism and the cult of the individual genius – ‘the modern craze for personality’ – which he insinuates did much to damage this healthy state of affairs. To a Renaissance composer like Hassler, untouched by Romantic canons of creativity, it was evidently all the same whether he wrote the tune in question or merely arranged it; not so to Böhme, who as a nineteenth-century musicologist and editor of the Altdeutsches Liederbuch (1877) presumably felt the need to ascribe the tune to Hassler’s personal invention.

We do not normally think of Vaughan Williams as an ‘anti-Romantic’ composer. Holding music to be ‘the vehicle of emotional expression and nothing else’, he took lifelong inspiration from nineteenth-century poets like Whitman and Arnold and drew, perhaps more consistently than any other twentieth-century symphonist, on Beethoven and the heroic tradition.2 Sharing the nineteenth-century belief in a nation’s unique cultural characteristics, he turned to native folksong and to models of early English composition in order to craft a personal and highly idiosyncratic style. But embedded in this project of self-creation was a suspicion of the unbridled individualism associated with Romanticism. While reflective of national pride, his turn to Tallis, Gibbons and Purcell was equally driven by an attraction to musical ‘historicism’ and the compositional and emotional discipline it imposed on the musician. Folksong, similarly, brought its own welcome restraints. Passed down orally from singer to singer over generations, it reflected ‘feelings and tastes that are communal rather than personal’.3 In these terms, folksong offered opportunities for self-discovery, paradoxically, by freeing the composer from the intolerable pressure, unrealizable in itself, always to be original.

On one level, anti-Romantic sentiment must always have a place in so ‘collective’ an endeavour as establishing a national school of composition. Yet it is clear that Vaughan Williams’s opposition went deeper than mere logistical calculation and touched on core values that he retained throughout his life. Chief among these was the social utility of the artist – the idea, as he famously put it, that the ‘composer must not shut himself up and think about art, he must live with his fellows and make his art an expression of the whole life of the community’.4 It was in this spirit that he entered into the musical life of his time not just as a composer, but also as a conductor, lecturer, competition adjudicator, and much else. In these capacities, he worked with young and old, professional and amateur, alike, and saw himself as a practical musician whose job it was to help others engage with music actively and meaningfully. Hence his avoidance, in his own music, of the most extreme ‘modernistic’ (and potentially alienating) devices of the day; hence also the delight he took in writing music to fit different circumstances. Viewing himself as a facilitator of ‘national’ (i.e. local and community-based) music-making, he was a craftsman on the model (as he saw it) of Hassler, less concerned about the aesthetic sources of his creativity than its social effects.

That these ideas permeate Vaughan Williams’s life and work is amply demonstrated by even the most casual survey of his oeuvre. The simplified arrangements he frequently made of his works – by means of cueing in alternative instruments or recasting works for reduced forces – are oft-cited examples of this emphasis. Another is the astonishing amount of ‘functional’ music he produced – smaller works intended chiefly for amateur performance or written for religious services and commemorative occasions. This Gebrauchsmusik amounts to more than half of his published and unpublished catalogue. These works do not, of course, come close to matching the large-scale compositions in intensity or expressive significance (and, being smaller and often very short, they represent far less than half of his total output in terms of actual playing time). But it is a remarkable percentage nonetheless, one that testifies to the depth of the composer’s social idealism and that demonstrates with unexpected force the importance of ‘secondary’ compositional work to his nationalist vision.

What follows, then, is a first attempt to provide a survey of Vaughan Williams’s ‘functional’ music for amateurs, or at least that portion of it covered by folksong arrangements, hymn tunes and church music.5 Admittedly, not all of the church music falls neatly into the ‘amateur’ category, but the small scale of these works, their specific purpose, and the manifest influence of folksong and popular hymnody that they display, clearly justify their inclusion here. The discussion will take up the three groups in turn, surveying the composer’s engagement with each, identifying key works, and, where possible, noting stylistic traits that parallel developments in his musical language as a whole.

Folksong arrangements

Vaughan Williams’s arrangements of English folk music take many forms. They are scored for small orchestra, chamber ensemble, military and brass band, solo piano, chorus (mostly mixed but also women’s and men’s) and solo voice (usually accompanied by piano); are intended for home, school, concert and church use; and are included as incidental, dancing, occasionally even diegetic, music for plays, masques, pageants, ballets and operas. So numerous are his settings, indeed, that a final reckoning is virtually impossible, especially as the more ambitious arrangements (like those found in the suite English Folk Songs (1923) and other borderline ‘free compositions’) typically quote tunes piecemeal or as a kind of contrapuntal quodlibet. Arrangements of individual folksongs (i.e. arrangements identified as such and not intended as part of a larger musical design) are somewhat easier to tabulate, though even here we need to differentiate between folksongs (i.e. tunes with mostly secular texts), folk carols (tunes with religious texts) and folk dances (tunes without texts). Collating these, we arrive at 47 separate publications containing 260 distinct arrangements (at least 12 more are unpublished). Settings of Scottish, Welsh and Irish as well as continental folksongs and carols also appear in these and other sources, adding a further 31 individual arrangements to this total.6

There were of course long-term compositional benefits to be gained from this work. Crafting so many different arrangements in so many different formats had the potential to bring folksong within reach of a wide segment of the population, and thus deepen public appreciation of native musical traditions. This, it was hoped, would help solve the perennial problem of generating an audience for the English composer who had long been passed over in favour of continental musicians. (A cornerstone of this strategy, pursued by Cecil Sharp and enthusiastically supported by Vaughan Williams, was to introduce folksongs to the populace at an early age by including folksongs in the school curriculum.)7 But social and humanitarian concerns were a possibly more important motivation, for folksong was held up as a cultural artifact common to the experience of all English men and women; its dissemination throughout society as a whole would thus serve as a reminder of a shared cultural heritage and help forge connections between social classes. It would also transfer to a new, literate class of performers long-standing oral traditions of making music ‘for yourself’.

It was an ambitious agenda, especially since not everyone shared the composer’s belief in folksong’s contemporary relevance. The ingrained prejudice against folksong as antiquated and extraneous to the modern world was strong, and countering it required careful presentation. One approach was to focus primarily on those songs that seemed relevant by virtue of their recent collection. Vaughan Williams occasionally arranged folksongs that he found in antiquarian sources like William Chappell’s Popular Music of the Olden Time (1853–9), but by far the great majority of his settings are of songs collected by Cecil Sharp, Lucy Broadwood, H. E. D. Hammond and others, himself included, active in the contemporaneous Folk Revival. A second, and more important, strategy was to select the most attractive folksongs for publication – those, as he put it, that possessed ‘beauty and vitality’8 – and clothe them in equally attractive arrangements. ‘Beauty and vitality’ are subjective values, and while Vaughan Williams dropped occasional hints about what made one folksong better than another,9 he refrained from identifying a specific method for arranging them. It was essential to focus on the melody – the arranger must be ‘in the grip of the tune’ so that the setting ‘flows naturally from it’, he wrote10 – but beyond that his own tendency was to pursue a wide range of compositional solutions, tailoring his arrangements to the abilities of those who would probably perform them. As a result, simple piano and choral arrangements, derived from parlour-music and popular choral traditions, stand alongside more elaborately ‘worked’ settings that draw on art-song and choral part-song repertories. The separation between styles is never absolute, however, as even the simplest arrangements show the traces of the skilled composer.

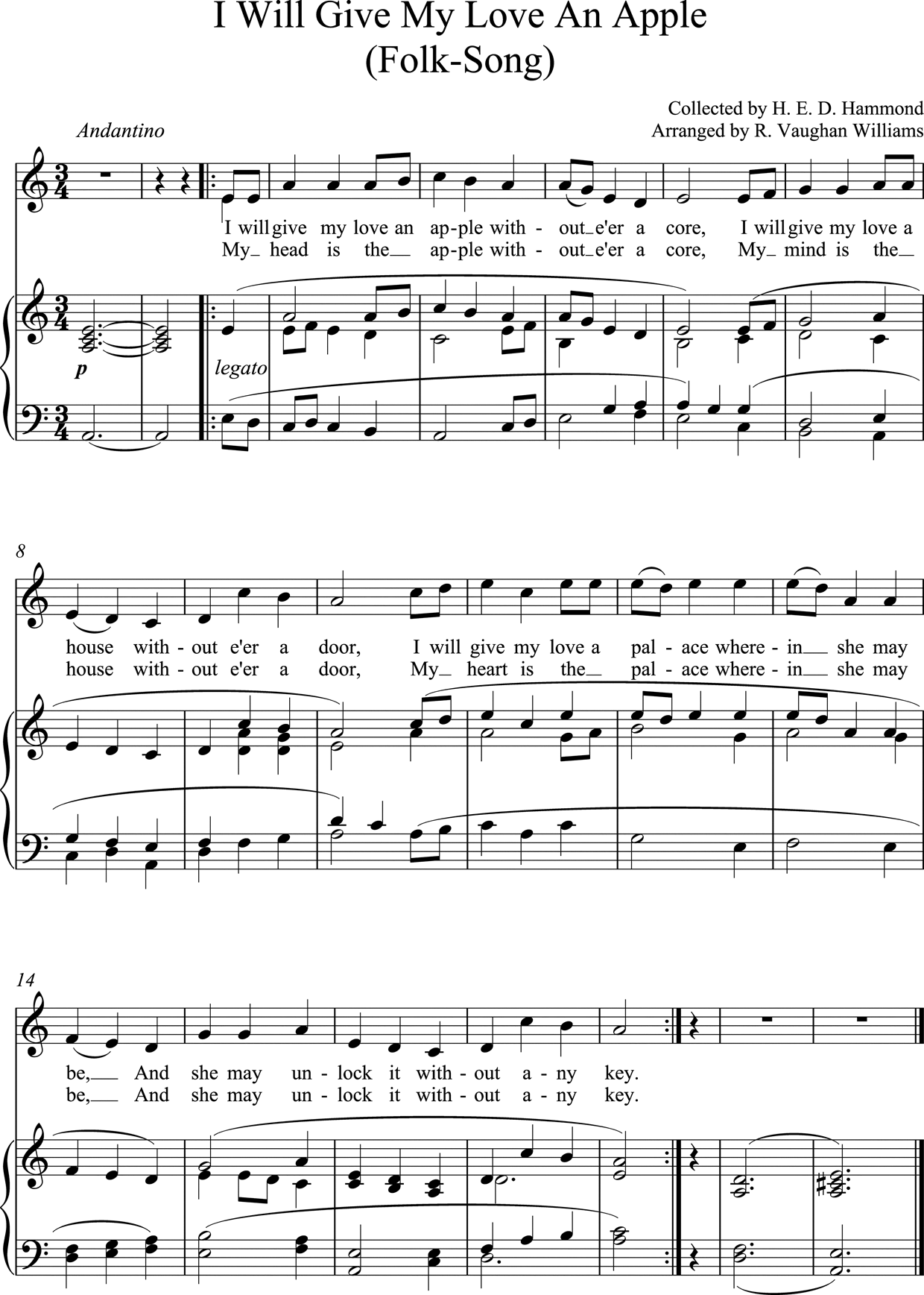

‘I Will Give My Love An Apple’, from Folk Songs for Schools (1912), for unison singing and piano accompaniment, offers a case in point (see Ex. 7.1). Vaughan Williams always reserved his ‘simplest’ manner for children, on whose musical tastes and preferences much of the hope for the future evidently depended, and the setting is clearly designed with their inexperience in mind. The tune in the vocal line is doubled throughout by the pianist’s right hand, while the steady three- (occasionally four-) part texture, with its unvarying crotchet rhythm, provides further encouragement. The Aeolian melody, with its occasional tricky skips, might seem to represent a challenge for children, but Vaughan Williams’s strict modal diatonicism and careful placement of each chord lend it an inevitable air. Carrying this off successfully is harder than it looks and is in fact rooted in part-writing techniques taken from the ‘learned’ tradition. The many chord voicings and inversions, the careful control of suspensions and other diatonic dissonances, the well-conceived bass that moves mostly by step and usually in contrary motion to the melody – these sustain a sense of forward motion that splendidly enhances the tune. Contributing to the overall effect are the unexpected move to the F (VI) chord in bar 15, the late (and once-only) employment of which lends extra weight to the end of the strophe, and the careful integration of the tune’s frequent quaver-quaver-crotchet rhythm throughout the accompaniment. Such concern for the overall architecture of the setting demonstrates the degree of ‘composerly’ skill that Vaughan Williams was prepared to bring to even his most modest folksong settings.

Ex. 7.1. ‘I Will Give My Love An Apple’.

The settings for adult vocal groups, by contrast, run the gamut from simple to more complex in tone and construction. To some extent, the level of difficulty or elaboration is a function of the specific choral subgenre drawn on in each case. Thus a dozen settings for unaccompanied men’s voices (TTBB), largely homophonic and with the melody principally in the 1st Tenors, invite comparison with the eighteenth-century glee and especially (given the folksong material on which they are based) the early nineteenth-century German Männerchöre repertory. ‘The Jolly Ploughboy’ (1908), ‘The Ploughman’ (1934) and the old English air ‘The Farmer’s Boy’ (1921) are exemplary. Other TTBB arrangements, however, combine this ‘direct’ style with the varied textures and more intricate part-writing of the contemporaneous part-song. Thus ‘Bushes and Briars’ (1908) and ‘Dives and Lazarus’ (1942, from Nine Carols for Male Voices) – to take two widely separated publications – pass the tune engagingly between different voices and use overlapping suspensions to create piquant harmonies that express the text. The striking polychords at the final cadence of the former, in particular – parallel 64 chords sounding against a dissonant pedal – convey the despair of the final verse while also briefly anticipating the bitonal effects of the composer’s music of the 1920s. Timbral contrast between texted soloist and wordless choir, first essayed in ‘The Winter Is Gone’ (1912) and incorporated into the Fantasia on Christmas Carols of the same year, becomes an especially favoured device, and contributes much to the appeal of celebrated arrangements like ‘The Turtle Dove’ (1919) and the Scottish ‘Loch Lomond’ (1921).

Elaboration is especially pronounced in the twenty-six settings whose scoring for unaccompanied mixed voices (SATB and its variants) draws even more firmly on the part-song tradition. Shifting textures and thoroughgoing counterpoint are the very lifeblood of arrangements like ‘A Farmer’s Son So Sweet’ (1926) and the SATB versions of ‘Bushes and Briars’ and ‘The Turtle Dove’ (both 1924), as well as of a number of non-English settings like the Manx ‘Mannin Veen’ (1913) and the Scottish ‘Alister McAlpine’s Lament’ (1912) and ‘Ca’ the Yowes’ (1922). The timbral innovations of this last, in particular – wordless female voices ‘distanced’ from the texted lower voices by means of their high register and parallel motion – resemble those found in Vaughan Williams’s purely original compositions from the period. Similar effects inform the Five English Folk Songs (1913), probably the composer’s most famous folksong settings, in any medium, and still frequently heard today. The vocal virtuosity demanded by these arrangements is unsurpassed in his output (Michael Kennedy surmises that they were composed for a choral competition).11 Frequent vocal divisi results in as many as six different parts (in ‘The Spring Time of the Year’) while rapid-fire voice exchange (‘The Dark-Eyed Sailor’, ‘Just as the Tide Was Flowing’) creates a dizzying effect. In ‘The Lover’s Ghost’, folksong material combines with techniques drawn from the sixteenth-century madrigal, a distant forebear of the part-song. Textural contrasts and points of imitation punctuate the structure while, in verse 3, competing melodic fragments of the tune are presented in both ‘real’ and ‘tonal’ contexts (and in original and inverted forms) to create Elizabethan false relations.

Other mixed-voice settings display a similar thematic integration. The ‘derived’ counter-melody of the 1924 ‘Bushes and Briars’ increasingly dominates the setting as it proceeds, culminating in the anguished clash of descending lines in the final verse. The rocking tertian progressions of the whimsical SATB ‘An Acre of Land’ (1934), themselves drawn from the skipping thirds of the melody, inform the tonal plan, which ambles no less whimsically between tonic and relative minor. Even the opening modal mixture (E♯ in the soprano vs. E♮ in the tenor) that ‘summarizes’ the tune in the celebrated SATB ‘Greensleeves’ (1945) turns out on closer inspection to encapsulate the harmonic conflict between tonal and modal forms of the dominant and ultimately between the setting’s principal keys of F♯ and A. Similar links between modal inflection and tonal argument are found in the Serenade to Music (1938) and the Sixth Symphony (1944–7) from the same period.

No obvious stylistic divide between subgenres emerges when it comes to the ninety-five settings for solo voice and piano accompaniment. The dominance of the late Victorian royalty ballad and parlour song, already a problem for those who would establish an art-song tradition in England, was keenly felt by those seeking to disseminate folksongs through arrangements for the domestic market. For a high-minded composer like Vaughan Williams, contemptuous of the commercial music industry12 but cognizant of its popularizing potential, compromise was inevitable. Not that his arrangements merely duplicate the stereotyped arpeggiations and simplistic harmonies of the parlour ballad (a few of the twelve French and German folksong settings from 1902–3 come close, but are saved by the tasteful manner in which the formulae are applied). Rather, his tendency is to combine Victorian elements with the more sophisticated techniques of the solo art song. Sometimes the competing styles are kept separate – as in ‘The Lost Lady Found’ and ‘As I Walked Out’, Nos. 4 and 5 of Folk Songs from the Eastern Counties (1908), where uniformly simple triads and textures in one setting give way to melting diatonic dissonances and an elegantly shifting formal arrangement in the next. More typically, the two styles are combined in the same setting, as with ‘Tarry Trowsers’ (No. 2 from the same collection), in which popular ‘oompah’ rhythms mix with Bachian counterpoint, and ‘The Lincolnshire Farmer’ (No. 12), where broken-chord vamps are clothed in Debussian harmony. ‘The Saucy Bold Robber’ (No. 10), likewise, begins with simple crotchet rhythms in the accompaniment, only to pick up speed in later verses and conclude with chromatic runs worthy of Liszt.

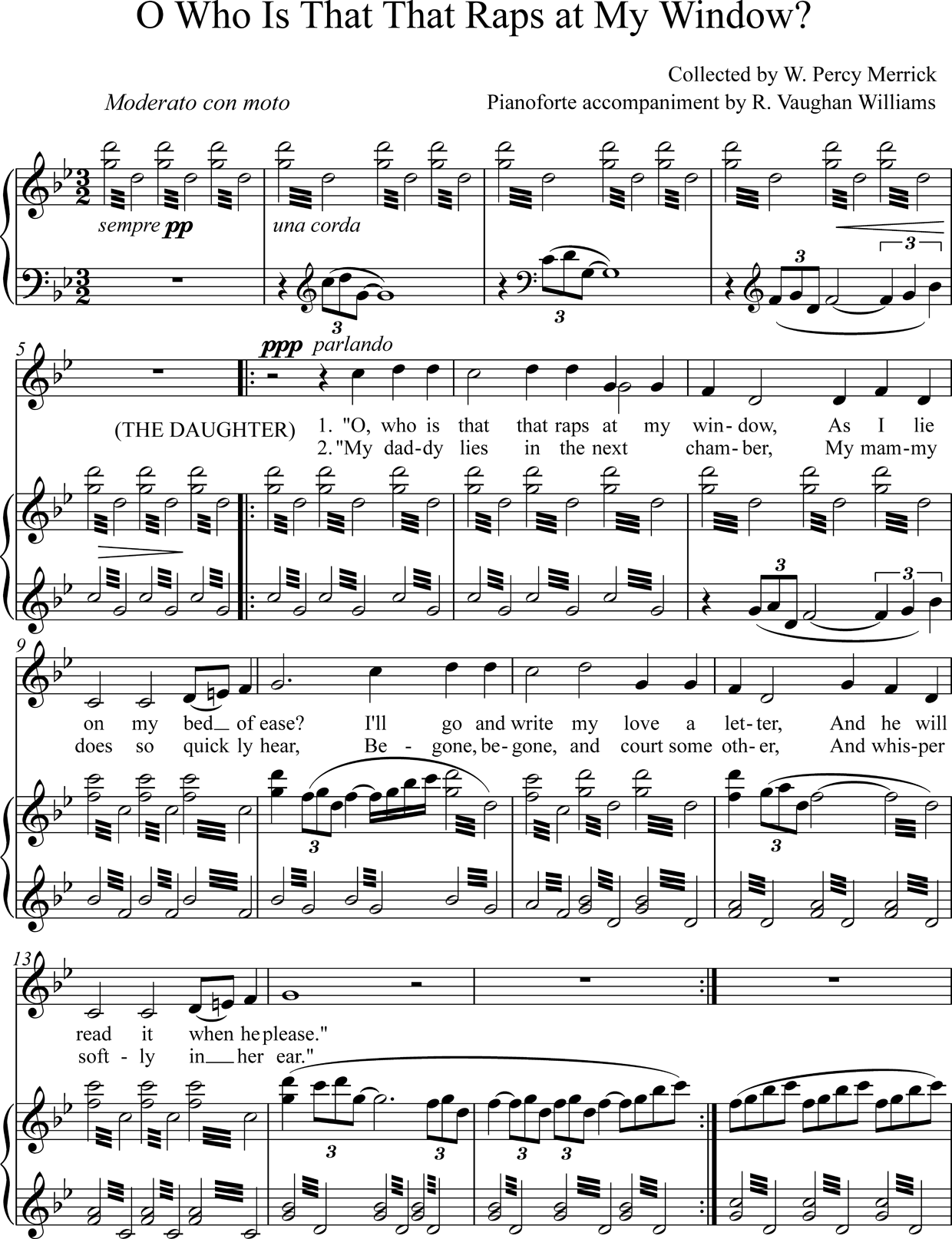

Folk Songs from Sussex (1912), comprising fourteen arrangements of folksongs collected by W. P. Merrick, offers a stronger dose of art song. The continental styles that were mostly hinted at in the 1908 collection are more prominent here; in some cases, they form the core of the setting. The atmospheric effects and passionately descending parallel seventh chords of ‘Low Down in the Broom’ (No. 2) are deeply indebted to Debussy, for example, while Wagner stalks the wildly chromatic passages of the carol ‘Come All You Worthy Christians’ (No. 9). Fauré, too, permeates ‘The Seeds of Love’ (No. 11, with violin ad lib.), where lush harmonies, richly arpeggiated, reveal a side of the composer glimpsed virtually nowhere else. By no means are these and other settings from the collection pale imitations of their models, however: integrating continental styles with the strong diatonic lines of folksong, they embody the hard-won eclecticism of Vaughan Williams’s first maturity. ‘O Who Is That That Raps at My Window’ (No. 5) virtually summarizes this in its tremolo effects, static polychords and shifting pentatonic pitch collections – elements that contribute to a dramatic intensity not unlike that of On Wenlock Edge (see Ex. 7.2). The gapped head-motive, a Vaughan Williams fingerprint here drawn from the first phrase of the tune and presented in a variety of timbral and harmonic contexts, anchors the setting formally, while the motive’s rhapsodic extensions in bars 10 and 14–16 anticipate those of The Lark Ascending, begun two years later. The non-functional juxtaposition of triads, observable beneath the surface activity in bars 10–15, is another mark of the mature style; their return during the dramatic final verse, forte and spaced out over as many as four octaves, is in the manner of the Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis and other works that reserve purely triadic harmony for climactic moments.

Ex. 7.2. ‘O Who Is That That Raps at My Window’, bars 1–16.

Whatever pressure he felt to conform to Edwardian song culture, ‘O Who Is That That Raps at My Window’ shows that Vaughan Williams believed that there was room for innovation so long as it was properly balanced by an awareness of the needs and expectations of amateurs.13 Thus we find the same mixture of novelty and convention, elaboration and simplification, throughout all his later arrangements for voice and piano – in the Eight Traditional English Carols (1919) and Twelve Traditional Carols from Herefordshire (1920), notable for their frequent modal mixture, as well as in Folk Songs from Newfoundland (1934) and Nine English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachian Mountains (c. 1938; published 1967). Here, as before, idiosyncratic and ‘uncomplicated’ settings stand side by side, while more than a few combine elements of both. Reduced textures – slighter chords, single-line accompaniments, etc. – increasingly characterize the last two publications, but this is less a concession to routine than a reflection of the relative austerity of Vaughan Williams’s interwar manner. Like the Shove and Whitman settings of the mid-1920s, the reduction of means results in concentration of material, as pithy head-motives and rhythmic figures, even the occasional counter-melody, distil the essence of the vocal line. An outwardly simple arrangement like ‘The Ploughman’, from Six English Folk-Songs (1935), packs all this and more into its sixteen bars, making it a small masterpiece of structural integration.

After 1945, Vaughan Williams turned almost exclusively to choral settings. The choice is partly explained by the fact that twenty-two of the thirty-seven arrangements from this period were written for Folk Songs of the Four Seasons (1949) and The First Nowell (1958), two large-scale choral works based around the idea of the folksong ‘anthology’. The retrospective aura surrounding these works – reinforced by the familiarity of most of the tunes selected – is not, however, matched by the arrangements themselves, which offer much to surprise. The unusual scoring (for women’s voices with orchestral or piano accompaniment) and striking modal innovations of the 1949 work, in particular, closely parallel the timbral and tonal experiments of the composer’s last decade. No two settings are quite alike – even the ‘unison’ settings vary in the forces used for accompanying descants – while the synthetic modal scales and contrapuntal knottiness of a cappella two- and three-part settings like ‘The Sheep Shearing’ and ‘The Unquiet Grave’ make them among the most interesting of his entire career.

Hymn tunes

Among Vaughan Williams’s best-known – and certainly most widely disseminated – folksong arrangements are the seventy or so that he adapted as hymn tunes and published in The English Hymnal (1906; revised edition, 1933) and its later offshoot Songs of Praise (1925; enlarged edition, 1931).14 Tunes like ‘Monks Gate’ (adapted from ‘Our Captain Calls’), ‘Kingsfold’ (‘Dives and Lazarus’) and ‘Forest Green’ (‘O Little Town of Bethlehem’, adapted from ‘The Ploughboy’s Dream’) have spread well beyond the Church of England to occupy a permanent place in the repertories of Catholic and Reformed congregations alike. But the composer’s involvement with hymnody went much deeper than mere folksong campaigning, for he served as music editor of these hymn books,15 an enormous undertaking that brought him into close contact with a wide range of musical traditions, many from outside his native shores. These volumes have been much praised for their editorial discernment and clarity – he exhumed old versions of tunes and greatly improved on contemporary practices of source identification – and for the quality of their musicianship. Arrangements by Vaughan Williams (and his adaptations of others’ arrangements) are among the most common versions of tunes like ‘Helmsley’ and ‘Winchester Old’, met with in the hymn books of many different faiths, while his redaction of ‘Lasst Uns Erfreuen’ (‘Ye Watchers and Ye Holy Ones’), used for the doxology in many English-speaking churches and homes to this day, is possibly one of the best-known melodies in Christendom. His eighteen original hymn tunes, likewise, are among the most popular written in the twentieth century; ‘Sine Nomine’ (‘For All the Saints’), ‘Salve Festa Dies’ (‘Hail Thee, Festival Day’) and ‘Down Ampney’ (‘Come Down, O Love Divine’), among others, have spread across the globe, lodging themselves within many hymnodic traditions, and show no signs of disappearing.16

Much has been written about the apparent incongruity of a self-proclaimed atheist – one who ‘drifted into a cheerful agnosticism’ later in life – devoting so much time and energy to religious music.17 Whatever the precise nature of his beliefs, there can be little doubt that writing for the Church of England provided for Vaughan Williams the opportunity to put his deepest artistic beliefs into action. Recognizing that for most people, church attendance represented their only regular opportunity for music-making, he set aside any theological scruples in order to focus on this crucial venue for amateur singing. Placing the needs of the congregation before those of the trained choir, he pitched tunes as low as possible, insisted on slower tempi and unison singing, and provided a wide variety of accompanimental patterns and arrangements, including various methods of combining congregation and choir.18 He also introduced much unfamiliar English material, notably folksongs but also early psalm tunes by Tallis, Gibbons and Henry Lawes. Exposure to these ‘bracing and stimulating’ melodies would, he believed, help create a demand for the music of contemporary English composers who were inspired by this same source material. It would also improve a debased musical taste by weaning congregations from the ‘languishing and sentimental’ hymn tunes of the Victorian church, and ultimately ease the grip of the commercial interests that had foisted these tunes, unwanted, upon them. Replacing what was essentially an alien and repugnant musical style with one that more truly ‘represent[ed] the people’, his reforms would improve the musical health of the nation.19

The mixture of paternalism and progressivism will be familiar from Chapter 1. On the one hand, he assumed the insufficiency of the people to make good musical choices for themselves, especially in the face of commercial pressures, and worked to ‘improve’ their taste. On the other, by insisting on unison singing and suggesting new methods of performance, he effectively elevated the congregation to a status of artistic equality with the choir. The unlikely combination of aesthetism and populism was one he shared with other early twentieth-century hymnodic reformers, notably the Poet Laureate, Robert Bridges, whose Yattendon Hymnal (1899) may be said to have initiated the trend, as well as the left-leaning Anglo-Catholics making up The English Hymnal committee, and the founders of the ‘Hymn Festival’ movement, Hugh Allen, Walford Davies and Martin Shaw among them.20 But it was Vaughan Williams who did most to mainstream these ideas, with the result that he has been singled out by critics who question how a self-styled ‘populist’ could dismiss an entire repertory of Victorian ‘favourites’.21 Close examination of the sources shows, however, that, whatever he may have said about them, Vaughan Williams was surprisingly indulgent towards Victorian hymns, retaining 118 tunes by Victorian composers in the 1906 English Hymnal, where (by his own admission) he felt some pressure to do so, and more than 70 in Songs of Praise Enlarged, where he was under no such obligation.22 It is true that he generally viewed the strong diatonic outlines of folksong and the relative austerity of early English psalmody as a salutary antidote to nineteenth-century emotionality. But then this was the attitude of many Victorian editors, particularly those of High Church leanings, who maintained earlier traditions of adapting hymn tunes from folksong and who did much to infuse the English hymn-tune repertory with music taken from older non-English sources.23 Indeed, it was their example that inspired Vaughan Williams to expand his hymn books’ offerings even beyond theirs, so that English tunes new and old now coexisted with an unprecedented number of Scottish, Welsh, Irish, continental European and even American tunes of all periods. As he later wrote of his English Hymnal experiences, ‘I determined to do the work thoroughly’ so that the book might be ‘a thesaurus of all the finest hymn tunes in the world’.24

The eclecticism of Vaughan Williams’s editorial work is often overlooked, a casualty of the insularity that often characterizes the reception of his music, and yet it holds the key to one of the meanings of his nationalism. For what he really sought with hymn tunes was not the propagation of a specifically ‘English’ musical style but rather the consolidation of a repertory of tunes, native or otherwise, that reflected English musical practice. Basing hymn tunes on early English music and folksong was only one way to achieve this; drawing on ‘outside’ sources that had made their way into English tradition was another. In these terms, the Genevan psalter, brought to England by sixteenth-century Protestants returning home after the Marian Exile, counted as ‘national music’, as did those Lutheran chorales, harmonized plainchant melodies and continental folksongs and carols (notably those adapted from the 1582 Piae Cantiones) that had entered into English usage, largely at the hands of Victorian editors. He was interested not only in retaining well-known tunes, however, but also in introducing those that might become popular. Hence his striking out into French Diocesan and American revivalist repertories as well as his digging yet deeper into sources first tapped by the Victorians. (Here, his introduction of recently collected folksongs, not just those taken from antiquarian publications, was a real innovation.) If these efforts to expand the repertory conveniently coincided with his weeding out of Victoriana, it is important to stress again his deliberate retention of a large number of these tunes. Taken to the hearts of the people, Victorian hymnody had unquestionably become part of the nation’s cultural heritage and could not be ignored.

Thus was Vaughan Williams’s approach to hymnody closer to Victorian practice than his words might suggest. The similarities extend to his own original hymn tunes which, if they carefully avoid the ‘sickly harmonies of Spohr’ and the ‘operatic sensationalism of Gounod’, still partake of the ‘grand effects’ of nineteenth-century art music that Nicholas Temperley has identified as the overriding characteristic of the Victorian hymn tune.25 This is the case with ‘Sine Nomine’ and ‘Salve Festa Dies’, with their ‘orchestral’ organ parts and ‘symphonic’ treatment of vocal forces, no less than with ‘Down Ampney’ and ‘Magda’, whose lyrical warmth and intricate part-writing clearly emulate tunes by John Bacchus Dykes and Samuel Sebastian Wesley. Even the composer’s concern for a tune’s ‘singability’ – its accessibility to congregations of limited musical experience – seems to have been anticipated by the Victorians. It is no coincidence that all of the tunes mentioned here are firmly tonal, nor that his folksong adaptations tend to blunt the idiosyncrasies of the source melody by harmonizing modal and gapped scales in a tonal context and by ironing out irregular rhythms and phrase lengths. Such alterations were an inevitable consequence of the need to match tunes with metrical texts; even so, it is plain that he took extra care to bring ‘unorthodox’ tunes into line with Victorian norms.26

Not that innovation was lacking. The slower tempi, lower pitching and varied arrangement offerings were all radically new, as was the insistence on unison congregational singing. Indeed, one of the most striking features of The English Hymnal was the adaptation of the ‘unison song’ to the hymn-tune format. This very English choral subgenre, whereby harmony is relegated to the accompaniment while all voices (here, congregation and choir) crowd on to the melody line, had been adapted to church hymnody by Stanford and Parry but not to the extent that Vaughan Williams used it. Meanwhile, his revival of psalm-tune settings by Ravenscroft and others, in which the congregation was directed to sing the tune (in the tenor) against the choir’s four-part harmony, contributed to the emergence of the popular ‘descant’ style of Anglican hymnody after 1915.27 Purely stylistic innovation, by contrast, was slower to emerge. Possibly the success of ‘Kingsfold’ and ‘Kings Lynn’, two adapted folksongs whose modal eccentricities were not ‘edited out’ of the 1906 English Hymnal, convinced him that congregations could sing such music; whatever the inspiration, Songs of Praise introduced a spate of original hymn tunes that emphasized the ‘characteristic’ features of folksong and early English music. Tunes like ‘Mantegna’, rooted in the Phrygian scale and with wildly unpredictable harmonies throughout, and ‘Oakley’, whose sudden turn to Elizabethan dance rhythms halfway through makes for a striking formal experiment, drink deep at the well of native tradition and unabashedly proclaim a ‘national’ style.

These tunes represent the extreme, however. By far the more common procedure in the later hymn books was to combine native elements with mainstream techniques, as in the celebrated ‘King’s Weston’ from 1925 (see Ex. 7.3). The rugged Dorian melody and repeated VII–i progression (occurring in bars 1–2, 6, 10 and 15–16) announce a boldly modal music, while a descending stream of parallel 63 chords in bar 13 – concluded, after an interruption, on the third beat of bar 14 – introduces a taste of fauxbourdon. Yet these ‘characteristic’ features are carefully blended with traditional methods of part-writing, dissonance treatment and long-range formal planning whereby an insistent melodic pattern of rising pitches and repeated rhythms mounts until its sudden reversal in bar 13. So dramatic a trajectory is enhanced by the infiltration of the modal E minor tonic by its relative G major, a competing ‘tonal’ key area that reinterprets the crucial D major chord (VII in E) as a dominant (note its strong reinforcement by the secondary dominant in bars 11–12). The ‘true’ key is ambiguous because the composer carefully refrains from directly emphasizing either tonic – here the parallel 63 chords at precisely the moment we anticipate resolution are a stroke of genius – and it is only with the arrival at the E minor chord in the last bar, at once surprising and expected, that harmonic tension is released.

Ex. 7.3. ‘King’s Weston’.

In its mixing of native materials and common-practice techniques ‘King’s Weston’ embodies a kind of synthetic ‘middle ground’ between innovation and convention, ideological commitment and broad-minded inclusiveness, that we find in Vaughan Williams’s engagement with hymnody as a whole. Even the details of the arrangement reflect this blended approach, for the massed voices and unconventional three-part accompaniment draw both on the ‘unison song’ format of the reformers and on the Victorian practice of giving ‘orchestral’ weight to the organ part. The forceful tone and ‘Sine Nomine’-like march tread, meanwhile, conform to the ‘muscular Christianity’ of Caroline Noel’s very Victorian text, with its militant references to ‘captains’, ‘empires’ and ‘victory’.

Church music

Vaughan Williams’s early atheism appears to have affected his attitude towards other forms of liturgical music for, apart from hymn tunes and a few student works, he wrote no music for the church until 1913. This was the isolated anthem ‘O Praise the Lord of Heaven’, composed for the fortieth anniversary of the London Church Choir Association. Music appropriate to Anglican worship does begin to appear with greater frequency after World War I; still, many of the works from this period were either commissioned or written with specific performers in mind. Altogether, only eight of the composer’s twenty-seven mature liturgical works (comprising small-scale anthems, motets, canticles and organ preludes, as well as a small clutch of simple prayer settings for children) were composed entirely ‘on spec’.

Like his hymn-tune arrangements, in other words, Vaughan Williams’s church music would seem chiefly to be an outgrowth of his philosophy of musical citizenship. A number of these works – the Te Deum in G (written for the enthronement of the Archbishop of Canterbury, 1928), the Festival Te Deum ‘founded on traditional themes’ (for the coronation of George VI, 1937), ‘The Souls of the Righteous’ (for the dedication of the ‘Battle of Britain’ Chapel, Westminster Abbey, 1947), O Taste and See and the The Old Hundredth Psalm Tune (for the coronation of Elizabeth II, 1953) – were specially composed for state occasions. Others, like the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis (‘The Village Service’, 1925) and the simple Anglican-chant setting of Psalm 67 that he wrote for St Martin’s Church, Dorking in 1945, were explicitly geared to the limited resources of the parish choir. Taken together, these works display an extraordinary disparity in their intended audience and venue, and yet are united in a shared focus on filling a specific need. Moreover, many of them can be performed using ‘alternative’ forces, while some are even suitable for non-liturgical performance at outdoor festivals, public ceremonies and concerts.

The use of popular hymn tunes in many of these works confirms this broadly democratic approach. ‘St Anne’ (‘O God Our Help in Ages Past’) appears in both ‘Lord, Thou Hast Been Our Refuge’ (1921) and ‘O How Amiable’ (1934), while the entire text of the 1954 Te Deum and Benedictus is grafted, somewhat bizarrely, on to a series of well-known psalm tunes. This last choral work has a part for the congregation, as do the four so-called ‘hymn-anthems’, of which the The Old Hundredth Psalm Tune, mentioned above, is the best known. This genre, popularized by the interwar Hymn Festival but appropriate to worship services, combined congregation and choir by presenting the different verses of popular hymns in varied forms of arrangement (a descant was obligatory), sometimes with brief instrumental interludes linking the strophes.28 A more striking experiment involving untrained voices is the complete set of Services (Morning, Communion, Evening) in D minor written for performance at Christ’s Hospital boarding school in 1939. No hymn tunes are employed, but an ingenious arrangement – a unison congregational part, seldom rising above d′′, combines with more complex music for SATB choir – allows (as the score states) for ‘a large body of voices [to] share in the musical settings of the service’. Here, the ‘unison song’ of the school assembly joins with the traditional forms of Anglican church music to create a work in which all can take part.

About a third of Vaughan Williams’s church music invites congregational participation; the remainder is for the trained choir alone and occupies a sliding scale from relatively easy to extremely difficult – further proof of his determination to provide music for every situation. Whatever the difficulty, liturgical and musical tradition is closely observed. Thus the Te Deum settings provide cuts for the authorized ‘shortened form’ of that canticle, while the D minor Communion Service follows the Prayer Book’s sequence of movements to the letter, with the Gloria placed last (Some Responses are also included). It is true that motets (only one of them in Latin) outnumber anthems, the more strictly Anglican genre, but this may reflect the development of a late nineteenth-century type of cathedral anthem, pioneered by Stanford, to which the name ‘motet’ was generally affixed.29 Stanford’s stylistic innovations, indeed, are palpable in the prominent organ parts (often quite independent of the voices) of several works as well as in the tight construction of ‘O Clap Your Hands’ (1920), the Te Deum in G and others. The Irish composer’s application of cyclical elements to all the movements of a service, thus creating a unified musical experience spanning a whole day, is actually carried further in the D minor Services, as nearly all the material can be traced back to the first two themes (bars 1 and 36) of the opening Te Deum. Finally, the antiphonal effects of the cathedral tradition are prominent in many works, achieved through the juxtaposition of decani and cantoris choral groups (or their equivalents) and by the playing of soloists off against the full choir in the manner of verse anthems and services.

The selection and handling of texts, likewise, show an impressive familiarity with church history and tradition. Most are taken from The Book of Common Prayer and the Authorized (King James) Version of the Bible, though the composer pushes past Anglican orthodoxy by also setting the dissenting prose of Bunyan (‘Valiant for Truth’, 1940) and mysterious Catholic texts by Skelton (‘Prayer to the Father of Heaven’, 1948) and the Office of Tenebrae for Maundy Thursday (‘O Vos Omnes’, 1922). Hymns and metrical psalm texts are also prominent – in the ‘hymn-anthems’, of course, but also in the remarkable ‘Lord, Thou Hast Been Our Refuge’, which interleaves the Prayer-Book version of Psalm 90 with the first verse of Isaac Watts’s metrical paraphrase of the same. Critics who complain of the work’s stylistic incongruities – Watts’s poem is set to the sturdily diatonic ‘St Anne’, its ‘proper’ melody, while the Prayer-Book words are set to a rhythmically and modally flexible plainchant – have possibly overlooked this textual nuance.

So intimate a knowledge of the liturgy, texts and music of the Established Church speaks strongly of the composer’s cultural nationalism – his love for the words of the Authorized Version, his respect for patterns of worship that have prevailed in England for centuries, even his ‘inclusive’ embrace of the range of religious traditions (Puritan, Catholic, centrist) making up the Anglican compromise. (The works pointedly based on English folksong – the 1937 Te Deum, and the Benedictus and Agnus Dei that he contributed to J. H. Arnold’s Oxford Liturgical Settings (1938) – clearly also embody this ‘cultural’ view of the Church.) And yet, the intensity of expression in certain works suggests the possibility of an added personal motivation. It seems hardly coincidental that the stream of Vaughan Williams’s liturgical choral works effectively began with his return from the Great War, an experience that most commentators now agree triggered in him some kind of emotional if not metaphysical crisis. In particular, the immediate post-war works – ‘Lord, Thou Hast Been Our Refuge’, ‘O Vos Omnes’ and the Mass in G minor (1922) – communicate a sense of spiritual urgency that is conveyed by texts that emphasize human weakness and by settings that are predominantly sombre, occasionally anguished, but also flecked with unmistakable moments of radiance. The mysterious, even devotional mood of these works, one of which was directly inspired by Catholic ritual,30 is decidedly private, not public, in expression, and may well mark a shift from the composer’s early atheism to a mature agnosticism or possibly to something approaching orthodox Christian belief. For the charged atmosphere of these works is not exclusive to the immediate post-war period. It resurfaces in ‘Valiant for Truth’ and in ‘Prayer to the Father of Heaven’, as well as in ‘The Voice out of the Whirlwind’ (1947) and ‘A Vision of Aeroplanes’ (1956), works whose harrowing Old Testament imagery asserts the base inadequacies of human beings.

We should be wary of interpreting these works too securely in conventional religious terms, however. They may acknowledge human fallibility and insignificance but this does not mean that Vaughan Williams necessarily addressed himself to a specifically Christian God. He was certainly drawn to the ethical teachings of Christ and found solace in the Christian focus on the life of the spirit. But he would never have asserted that Christianity had a monopoly on what he called the ‘ultimate realities’: in the tradition of philosophical idealism, no religious faith had exclusive access to the realm that lay ‘beyond sense and knowledge’.31 Indeed, the inscrutability of these regions prepared him for a stoical acceptance of the possibility that the spirit did not exist at all. Whatever his uncertainty, the aspiration remained, and he viewed it as the role of the artist to share intimations of spirit with others in a language that they could understand. Hence his adoption of the ready-made frameworks of Christian ritual, and hence his focus on the everyday needs of the human community around him. The anguished cry that concludes the Agnus Dei and thus the Mass is a plea for peace directed not merely to the Divine but to all of humanity in the wake of World War I. The triumphal entry of the hymn tune ‘St Anne’, sweeping away all doubts at the conclusion of ‘Lord, Thou Hast Been Our Refuge’, celebrates God’s role as protector even as it proclaims the power of a shared musical culture to comfort and sustain us.

Like the folksong settings but unlike the hymn tunes, the church music roughly follows the mainstream of Vaughan Williams’s stylistic development. Thus the antiphonal forces of ‘O Praise the Lord of Heaven’ – two full choirs and semi-chorus – employ the textural and dynamic contrasts of the Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis, written three years earlier, while the blatant root-position parallel triads of ‘O Clap Your Hands’ announce the new simplification of means of the 1920s. The stylistic possibilities of retrenchment, meanwhile, are explored in ‘O Vos Omnes’, where chromatic parallel chord streams (at ‘desolatam’, for example) anticipate the bitonality and localized atonality of the large-scale experimental works of the interwar years. Expressive devices peculiar to the post-1945 music are observable as well – the shadings of light and dark resulting from subtle shifts of mode and tonality (‘The Souls of the Righteous’, ‘Prayer to the Father of Heaven’) and the captivation with new timbres and scales (‘A Vision of Aeroplanes’). Even works written in his patented ‘public’ vein – remarkably consistent across his entire career – echo more distinctive compositions from the same period. The melismatic jubilations of the 1928 Te Deum resemble those heard in the Benedicite, while the Jubilate from the D minor Morning Service shares material with the finale of the Fifth Symphony.

But it is the personal synthesis of elements taken from a wide variety of historical styles and periods that most strongly links the church music with Vaughan Williams’s output as a whole. This can be observed anywhere but is perhaps best illustrated by the Mass, a work whose neo-Tudor associations have obscured awareness of a wider eclecticism. Techniques favoured by sixteenth-century English church musicians – false relations, fauxbourdon-like textures, contrasts between soloist(s) and the full choir – are indeed present, but they are combined with others – canon and points of imitation, sectional division of the text (articulated by textural contrasts), emphasis on the church modes – that were the lingua franca of the period, common to English and continental music alike. Even these Renaissance techniques are but a ‘starting-point’32 for what is clearly a highly personal essay, however. The false relations derive less from contrapuntal logic than from Vaughan Williams’s idiosyncratic modal harmony (itself adapted from Debussy), while the traditional ‘sectional’ organization is cross-cut by nineteenth-century methods of thematic recall, both within and across movements. The striking employment of two SATB choirs, ‘answering’ one another and often combining into eight parts, likewise, would seem to derive less from Renaissance models than from the imaginative reconstructions of the nineteenth-century Cecilian movement.33 (Extreme dynamic markings – reaching pppp in the Credo – suggest this as well.) Folksong plays a role too, not merely in the frequent pentatonic gestures (as at ‘Gratias’ in the Gloria) but also in the way those gestures contribute to localized and even long-range motivic argument.

Though not lengthy, the Mass is undeniably a major work, a masterful utterance that the composer never sought to duplicate. The same cannot be said of the other works discussed in this chapter: small-scale ‘functional’ works chiefly intended for amateurs that for the most part trace well-worn patterns of genre, performance and style. What is remarkable is that, within this limited framework, Vaughan Williams produced such interesting music, much of it paralleling (and in some cases even anticipating) developments in his musical language. In the final analysis, though, innovation was secondary to the overarching social goals that he conceived for this music. With it, he sought to familiarize generations with a wealth of beautiful melody, raise awareness of a common cultural heritage, and above all inspire individuals to make music for themselves.

My thanks to Hugh Cobbe, Marc B. Meacy, Paul Emmons, Mark Rimple, Danton Arlotto, Tracie Meloy, Gail Dotson and especially Oliver Neighbour, to whom this essay is dedicated, for the loan of materials and for much help and advice in the preparation of this essay.

Notes

1 NM, 78.

2 Quotation from NM, 12. See Oliver Neighbour, ‘The Place of the Eighth among Vaughan Williams’s Symphonies’, in VWS, 213–33, and Lewis Foreman, ‘Restless Explorations: Articulating Many Visions’, in VWIP, 1–24, for discussion of the composer’s place in the Romantic tradition.

3 Cecil Sharp, quoted in NM, 32.

4 VWOM, 42.

5 , The Music of Ralph Vaughan Williams (Oxford University Press, 1954), 242–4, and , Vaughan Williams (London: Faber and Faber, 1963), 117–20, 123–42, devote sections of their books to these repertories but their treatments are generally very brief. , ‘The Church Music of Ralph Vaughan Williams’, Journal of Church Music 3/7 (July–August 1961), 2–5, offers a similarly short critical introduction.

6 There are an additional eighteen arrangements of ‘old English’ songs and carols, anonymous compositions that (in his view) bordered on folksong. For the rationale used in arriving at these numbers, see the series of checklists by the present author appearing in RVW Society Journal 49–51 (October 2010–June 2011).

7 , Cecil Sharp: His Life and Work (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1967), 58–67; see also VWOM, 270.

8 VWOM, 249.

9 See NM, 19–20; VWOM, 205–13. An unstated but nonetheless clear preference for modal (as opposed to tonal) folksongs emerges from his fieldwork practices and his selection of songs for publication. See , ‘Vaughan Williams and the Modes’, Folk Music Journal 7/5 (1999), 609–26.

10 , ‘Review of Six Suffolk Folk-Songs, collected and arranged by E. J. Moeran’, Journal of the English Folk Dance and Song Society 1/3 (1934), 173.

11 KC, 66.

12 VWOM, 25–30.

13 This may be why, in the course of an otherwise positive review of his folksong arrangements, Vaughan Williams criticized Cecil Sharp for his ‘fear of the harmony professor’ and timidity generally. See VWOM, 233–4. Certainly, modern settings by ‘such fiery young steeds’ (as he called them) as Benjamin Britten and E. J. Moeran met with his whole-hearted approval. See his reviews of folksong settings by these and others in Journal of the English Folk Dance and Song Society 1/3 (1934), 173–4, and 4/4 (1943), 164.

14 There were also many spin-off publications of these two volumes, of which Hymns Selected from The English Hymnal (1921) and Songs of Praise for Boys and Girls (1929) are representative. The Oxford Book of Carols (1928), co-edited with Percy Dearmer and Martin Shaw, also includes many hymn-like settings of folk carols.

15 Songs of Praise was co-edited with Martin Shaw.

16 Dickinson, Vaughan Williams, 488–93, provides a concordance of hymn tunes composed or arranged by Vaughan Williams that were reprinted in other twentieth-century hymn books. A complete list of the composer’s original hymn tunes will appear in a forthcoming article by the present author in the periodical The Hymn.

17 UVWB, 29. Byron Adams, ‘Scripture, Church and Culture: Biblical Texts in the Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams’, in VWS, 99–117, and , ‘Beyond Wishful Thinking: A Re-Evaluation of Vaughan Williams and Religion’, Ralph Vaughan Williams Society Journal 36 (June 2006), 14–23, provide differing views of the composer’s religious beliefs.

18 , ‘The Music of The English Hymnal’ in (ed.), Strengthen for Service: 100 Years of The English Hymnal 1906–2006 (Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2005), 133–54, provides an overview of Vaughan Williams’s editorial methods.

19 Quotations from KW, 33–4, and VWOM, 32.

20 For the social and political views of the committee members, see , Percy Dearmer: A Parson’s Pilgrimage (Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2000), esp. 62–3. The ‘Hymn Festival’ was a non-liturgical ‘service’, popular between the wars, in which members of the congregation met for the sole purpose of singing – and practising – hymns. See , Twentieth Century Church Music (Oxford University Press, 1964), 99–100.

21 , The Music of the English Parish Church (Cambridge University Press, 1979), vol. i, 319–30.

22 See Ian Bradley, ‘Vaughan Williams’ “Chamber of Horrors” – Changing Attitudes towards Victorian Hymns’, in Luff (ed.), Strengthen for Service, 231–43 at 236–9, and Julian Onderdonk, ‘Folk-Songs in The English Hymnal’, in Reference Temperleyibid., 191–216 at 205–10, for discussion of the composer’s selection of sources. Also significant in this context are the composer’s fourteen chorale preludes, eleven of which are based on nineteenth-century British hymn tunes.

23 , The Music of Christian Hymnody (London: Independent Press, 1957), 115–21.

24 VWOM, 116.

25 Temperley, Parish Church, 303–10. Other quotations from KW, 33.

26 Onderdonk, ‘Folk-Songs’.

27 Temperley, Parish Church, 324–5; , ‘Hymn Tune Descants, Part i: 1915–1934’, The Hymn 54/3 (July 2003), 20–7.

28 Routley, Twentieth Century Church Music, 105–6.

29 , ‘Church Music in England from the Reformation to the Present Day’ in (ed.), Protestant Church Music: A History (New York: W. W. Norton, 1974), 729.

30 UVWB, 142.

31 VWOM, 101; NM, 122.

32 , Vaughan Williams, 3rd edn (Oxford University Press, 1998), 128.

33 In most sixteenth-century English antiphonal writing, the decani and cantoris sides are kept strictly separate; when combined, they nearly always double the same parts. Expansion of parts in tutti passages does characterize the polychoral writing of sixteenth-century Venetian composers like Willaert and the Gabrielis, but it is doubtful that Vaughan Williams was familiar with this repertory.