In the San Salvario neighbourhood of Turin sits Cesare Lombroso's Museum of Criminal Anthropology, an institution in which small exhibition halls and shadowy rooms resemble large curiosity cabinets. In this space the remains of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century incarcerated individuals and deemed deviants have found their final resting place. Nearly thirty skeletons stand in a queue near the entrance to one of the museum's main halls, as if greeting visitors with their morbid forms. A bedecked outfit once worn by the notorious Italian brigand Antonio Gasparoni is displayed in a privileged position in the museum's main room; an informational panel positioned below the flashy outfit recounts Lombroso's acquisition of the outlaw's skull. Hundreds of crania sit neatly in macabre camaraderie in glass-front cabinets, once scrupulously studied for atavistic physical characteristics, including dimples, asymmetry and indentations. Some are intact, while others remain scarred by the scientist's saw. Remnants of infamous bandits such as Gasparoni coexist alongside those of lesser-known figures. Countless photographs of violent criminals – many of which are organised by race, similar physiological and phrenological features and sex – are displayed near death masks. Sitting side-by-side, the wax faces of thieves and homicidal killers stare out onto the museum's wooden floors. Displayed among these numerous corporeal objects are decorated water pitchers, drawings, engravings, paintings, poetry and mechanical trinkets created by those once imprisoned or in asylum, adding a further dimension to the sinister space.

These collected items represent the culmination of the troubling work of Cesare Lombroso and his protégés in the field of criminal anthropology. Beginning in the 1870s, the field of positivist criminology, led by Lombroso (1835–1909), sought to locate the organic causes of criminality. Rejecting metaphysics in favour of empiricism, proponents believed that deviancy and criminality were objectively readable through the body's physiognomy and physique. Lombroso's perspectives gained traction in Italy in the decades following unification, as they offered distinguishable reasons for the number of seemingly uncontrollable issues that plagued the new nation, including persistent violent and organised crime, increased poverty in the nation's southern regions, and the precarious economic conditions and political changes that came with urbanisation and industrialisation.

Lombroso believed that criminality was legible in highly expressive ways, including through abnormal modes of verbal expression, the artistic work of incarcerated individuals and signs of inscription – particularly tattoos (Figure 1).Footnote 1 Through his longstanding fascination with arte brut – a term he came to use in reference to poetry, writings and art objects created by asylum dwellers and incarcerated people – Lombroso moreover conceptualised the criminal as an exceptional, if problematic, individual capable of raw artistic expression. Many of his theories were based on pre-existent gendered and racist stereotypes from literature, taken to extremes through newfound claims of scientific objectivity and empirical study. Lombroso, who fancied himself a poet before turning to science in order to make a living, never completely eradicated the arts from his work. He integrated literary and artistic figures, including composers, philosophers and writers, as sources for discussion within his works on deviancy. His theories gained remarkable traction with a bourgeois public audience as well as with artistic luminaries of his time.

Figure 1. ‘Tatuaggi delinquenti’ from L’uomo delinquente, 5th edn (Turin, 1898).

Yet during his life, it appears that Lombroso did not realise the breadth of his influence over artistic production. Placed amidst the ‘raw art’ objects and pieces that decorate the otherwise macabre Museum of Criminal Anthropology, a plaque written by one of the museum's curators offers a reflection on the impact of the scientist's work in the last decades of his life: Lombroso ‘never seemed to see the possible connections [of his work] with the artistic manifestations of his time, and he did not sense the potential scope that the interpretation of what he had at hand might have allowed’. This will come as no surprise to those familiar with Lombroso; his mental capacities failed him in the years leading up to his death in 1909. The curator's remark nevertheless raises questions concerning the scope of the scientist's influence upon the artistic and musical cultures of Lombroso's time.

Although cultural historians have long been intrigued by Lombroso's intensely problematic and often slippery conceptions of deviancy, it has only been in recent years that musicologists and literary scholars have begun to question the role of late nineteenth-century science in Italian musical culture. As Jonathan Robert Hiller has argued, Lombroso's criminological writings played a crucial role in building Italian national consciousness in the post-unification era, and his ideas in turn influenced verismo literature and depictions of race in Verdi's Otello.Footnote 2 In the 2017 issue of the Laboratoire italien, Jean-Christophe Coffin suggests that Lombroso's concept of the musical genius was related to that of the mentally ill, linking the eccentric, artistic persona with the psychologically abnormal individual.Footnote 3 In the same issue, Pierangelo Gentile further suggests that Lombroso reserved the concept of genius for German composers such as Wagner, and that many Italian composers could be better understood as ‘ingenious’, due not only to their nationality and music, but also to their physiology.Footnote 4 And while Arman Schwartz has suggested that the shift from mysticism towards positivism within Italian scientific discourses influenced Puccini's configurations of realist soundscapes, scholars have yet to examine the impact of the positivists’ prominent criminological projects on the musical language and dramaturgical conventions of operatic verismo.Footnote 5

Lombroso's most influential work in the field of criminology culminated in the 1890s with the giovane scuola, the generation of composers following Verdi whose verismo works often featured deviant characters – including criminals, prostitutes and libertines – which came to dominate the Italian operatic scene. The particular connections between criminal anthropology and verismo were by no means coincidental. The literary leaders of the verismo movement, Giovanni Verga and Luigi Capuana, both knew Lombroso and used thematic ideas from the scientist's works in their own writings. Lombroso's visions of the Italian South, conception of the born criminal and descriptions of the female prostitute informed a number of characters in Verga's and Capuana's works, and in turn Lombroso's literary style was inspired by his literary colleagues. While Verga's and Capuana's works were adapted as operatic texts – most notably Verga's short story, then play, Cavalleria rusticana – the link between Lombroso and contemporary opera is more direct: playwrights, librettists and composers were familiar with the scientist's work. In particular, Giuseppe Giacosa, the playwright and co-librettist for a number of Puccini's operas, including Manon Lescaut, La bohème, Tosca and Madama Butterfly, was a close friend of Lombroso and frequented his salon in Turin throughout the 1890s. The French playwright Victorien Sardou, who composed the text source for Giacosa and Luigi Illica's libretto for Tosca, was said to have incorporated Lombroso's ideas within his plays.Footnote 6

The criminal anthropologist's aestheticised model of deviancy allows us to better conceptualise the sociocultural roots that underline modes of character expression in verismo. It also offers an opportunity to revisit critically the coalescence of art and life that largely distinguishes the dramatic environment of Italian opera produced during this era. Drawing on Lombroso's work together with sources from the Archivio Lombroso, the Museum of Criminal Anthropology and the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography in Turin, I demonstrate how Puccini's Tosca (1900) articulates Lombroso's signs of expressive deviancy. The composer's recycled modes of lyrical and motivic expression in the characters of Cavaradossi and Scarpia, respectively, call into question the significance of romantic stylistic gestures within verismo opera. In light of the critical anxiety felt by writers and critics concerning the shifting status of character type, plot lines, vocality and sound at the height of operatic verismo, this article reveals how contemporary criminological theories provided an avenue for composers such as Puccini to subvert modes of subjective, romantic expression to new scientifically inspired ends. Ultimately, Lombroso's bourgeois version of Italian perversity helped shape verismo's dramaturgical modes of expressing social deviance and character objectivity for turn-of-the-century Italian audiences.

Deviating from the norm: Lombroso in post-unification Italy

Lombroso was considered the most influential Italian thinker of the end of the nineteenth century, and he provoked a shift in Italian attitudes towards criminality and social deviancy. Following unification, citizens were confronted with continual rises in crime, poverty and violence, and were troubled by the lack of cultural cohesiveness that characterised their new Italy after centuries of existence as separate nation states. As Mary Gibson and Nicole Hahn Rafter have observed, Lombroso's concerns about locating and studying marginalised populations within Italy were prompted by the economic and political changes that came with democratisation, industrialisation and regionalised urbanisation.Footnote 7 Italy felt the weight of an inferiority complex: the nation's identity rested largely on the notion that marginalisation was a central element of modern Italianness.Footnote 8 The esteemed literary historian and pedagogue Francesco de Sanctis, who served as Italy's Minister of Public Education for a number of years in the 1860s and 1870s, championed the power of free will by which Italians might educate themselves, and particularly their children, out of these attitudes of cultural marginalisation, inferiority and even insincerity.Footnote 9 The emerging school of positivist scientists also felt responsible for making sense of these changes. Their approach, however, contrasted with De Sanctis's pedagogical model of educational and moral reform. To solve the perceived problem of Italy's cultural degeneracy and the so-called ‘atavistic’ members of its population, the positivists conducted studies in criminology to find the empirical roots of the nation's cultural vices.Footnote 10 The positivists believed that by identifying, separating and objectifying its so-called abnormal or deviant citizens the difficulties of a nation could be resolved or at the very least alleviated. This theory gained traction through findings from ethnological studies conducted in the 1870s. As a member of the Società italiana di antropologia e di etnologia [Italian Society of Anthropology and Ethnology], established in 1871, Lombroso and three other scientists were called on to create and distribute surveys throughout the country to document physical and anatomical attributes of citizens.Footnote 11 Among the goals for these questionnaires was to advance, as David Horn describes, ‘an evolutionary history and a geography of crime’ throughout Italy.Footnote 12 For Lombroso and his contemporaries, their intellectual gaze was anxiously turned towards the nation's south, which was considered the wellspring of many of its most serious issues.Footnote 13 Most alarmingly to the physician, studies showed that cities in the Mezzogiorno (from Rome southward) had anywhere from fourteen to twenty-three times more crime than comparative northern cities.Footnote 14 By the late 1870s, these concerns caught his keen attention. He believed that the nation had reached a point of self-destruction with its population increase and disproportionate rise of violent crime, much of which – particularly brigandry – was directed at social and civil institutions.Footnote 15 Rather than regarding the escalation of crimes as an outgrowth of the changing socioeconomic and political changes within the country, Lombroso theorised that most crimes were committed by descendants of ‘savage’ or ‘prehistoric’ individuals who had not been subject to modern laws but rather to primitive customs. He believed that the criminal type could be physically distinguished from normative individuals. This influential and to a great extent regionalised mentality concerning Italy's social problems reached an apogee with Lombroso's theory of the criminale nato. Inspired by Bénédict Morel's concept of degeneration and Arthur de Gobineau's racial theories, Lombroso's ‘born criminal’ was in its most extreme manifestation an evolutionary throwback who could not control its basic instinct for criminal or deviant behaviour.Footnote 16

Lombroso's five editions of L'uomo delinquente (1876–97) addressed these marginalised populations that aroused concerns within the European and American popular imaginations at the time. Over the five successive versions of this text, Lombroso devoted sections of his studies to organised crime, poverty and brigandage in southern Italy, exposés about the atavistic physiognomy most prevalent in lower-class individuals and racial minorities, and the location of intelligence, creativity and even genius of deviant types. He also included studies of more intrinsic tendencies of deviancy, including particular facial gestures or ticks, claustrophobia, libidinal drive and inclinations towards vagrancy. As Gibson, Stewart-Steinberg and Horn have all discussed, Lombroso's works were for a time understood as offering effective solutions for the seemingly uncontrollable issues that plagued the nation.Footnote 17

While Lombroso's principles were accepted to varying degrees by his contemporaries, many facets of his work were highly influential amongst scientists and a general readership in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Lombroso's theories prompted both conservative and liberal policy changes within the Italian criminal justice system.Footnote 18 As Hiller and Stewart-Steinberg have elaborated, Lombroso attracted non-specialist interest because of his colloquial, sometimes sensational style of composition as well as his inclusion of topical discussions concerning literature, popular authors, musicians and historical figures within his treatises.Footnote 19 He often cited conventional wisdom and earlier literary tropes to correct stereotypes about deviancy, gender and race in order to impose ‘new’ ideals that were rooted in scientific fact. As Hiller remarks, ‘This retroactive application of scientific principles to understand past literary figures and musicians allowed the school to be able to make the case that their theories were universally consistent throughout history; all that was necessary was for positivist science to discover them.’Footnote 20 In one instance in L'uomo delinquente, Lombroso criticised the messages of ‘bad’ writers in order to insert his own conception of the criminal's lack of moral consciousness:

Criminals exhibit a certain moral insensitivity. It is not so much that they lack all feelings, as bad novelists have led us to believe. But certainly the emotions that are most intense in ordinary men's hearts seem in the criminal man to be almost silent, especially after puberty. The first feeling to disappear is sympathy for the misfortunes of others, an emotion that is, according to some psychologists, profoundly rooted in human nature.Footnote 21

Though unacademic and casual to a modern audience, his literary references reached his readers’ cultural sensibilities and helped him garner popularity beyond a scientific readership. Indeed, Lombroso's work prompted a large-scale shift in Italian reading trends. By the end of the nineteenth century, scientific texts constituted nearly a third of books being purchased in Italy.Footnote 22 This simultaneously marked the waning influence of the legal class and classical theories of criminality as promoted by Cesare Beccaria in the eighteenth century. In contrast to Beccaria's ideology, which suggested that the criminal was inherently good and that society shaped an individual's deviant behaviour, Lombroso's positivistic stance created irredeemable yet compelling cultural villains.

Lombroso's unification of science and the arts

An acknowledged polymath, Lombroso brought together the arts and sciences by studying the creative output of those he considered deviant. Incorporating the writings of Stendhal, the poetry of Dante, the musings of Berlioz and Rossini and the musical output of Verdi and Wagner into his publications, he also regarded esteemed creative figures as apt subjects for intellectual enquiry. Indeed, his earliest efforts to fuse the arts with his own scientific enquiries drew on his fascination with the psychology of creative genius and its relationship to insanity and deviancy. He wrote extensively about these ideas throughout his career in a number of publications, including in the five editions of L'uomo delinquente, its counterpart La donna delinquente [Criminal Woman] (1895), Polemica in difesa della scuola criminale positiva [A Polemic in Defence of the Positive Criminal School] (1886) and the earlier Genio e follia [Genius and Madness] (1864). A number of scientists in Britain and France had already questioned the relationship between geniuses and the insane, including Alexandre Brierre, Louis-Francisque Lélut and Jacques Moreau.Footnote 23 Similar to the Italian physician, these scientists were advocates for phrenology, claiming, as Jean-Christophe Coffin summarises, that there was ‘neuro-anatomical evidence’ of genius.Footnote 24 In his multiple editions of Genio e follia, which were (like his other works) translated into English, French, Russian and Spanish, Lombroso incorporated a number of musical figures into his ‘radical hypotheses’ of the pathological genius, including Mozart, Rossini, Donizetti, Verdi and Wagner. According to Lombroso, the creativity of artists and musicians often masked neuroses, mental abnormalities and deviant tendencies.Footnote 25 Not all composers were regarded equally in Lombroso's pathological theories. In the 1888 publication L'uomo di genio [The Man of Genius], Rossini was categorised as a ‘genius in inspiration’, praised for his ability to compose so easily that he could write music in bed.Footnote 26 While mentioned otherwise in lists of geniuses, Bellini was not given much attention, but Donizetti was a key figure of fascination for Lombroso, emblematic of the severe neurotic genius for his struggles with sclerosis and meningitis and his well-known mental disorders during his later years.Footnote 27 As Pierangelo Gentile has observed, Lombroso avoids the term ‘genius’ in his discussions of Verdi in 1890s after the premiere of Falstaff for fear of critiquing the living icon as a deviant or degenerate.Footnote 28 Perhaps unsurprisingly given Lombroso's intense nationalism, he describes Wagner as an alienated genius with degenerative psychosis. In the same decade, Lombroso also published in what would soon become Italy's top musicological journal. In an article entitled ‘The Most Recent Scientific Surveys on Sounds and Music’, published in the inaugural issue of the Rivista musicale italiana of 1894, he begins with a striking (if self-serving) observation on the state of Italian music: ‘Even music, this art that seemed inspired by feeling and the most complete subjectivity has entered into a completely scientific phase.’Footnote 29

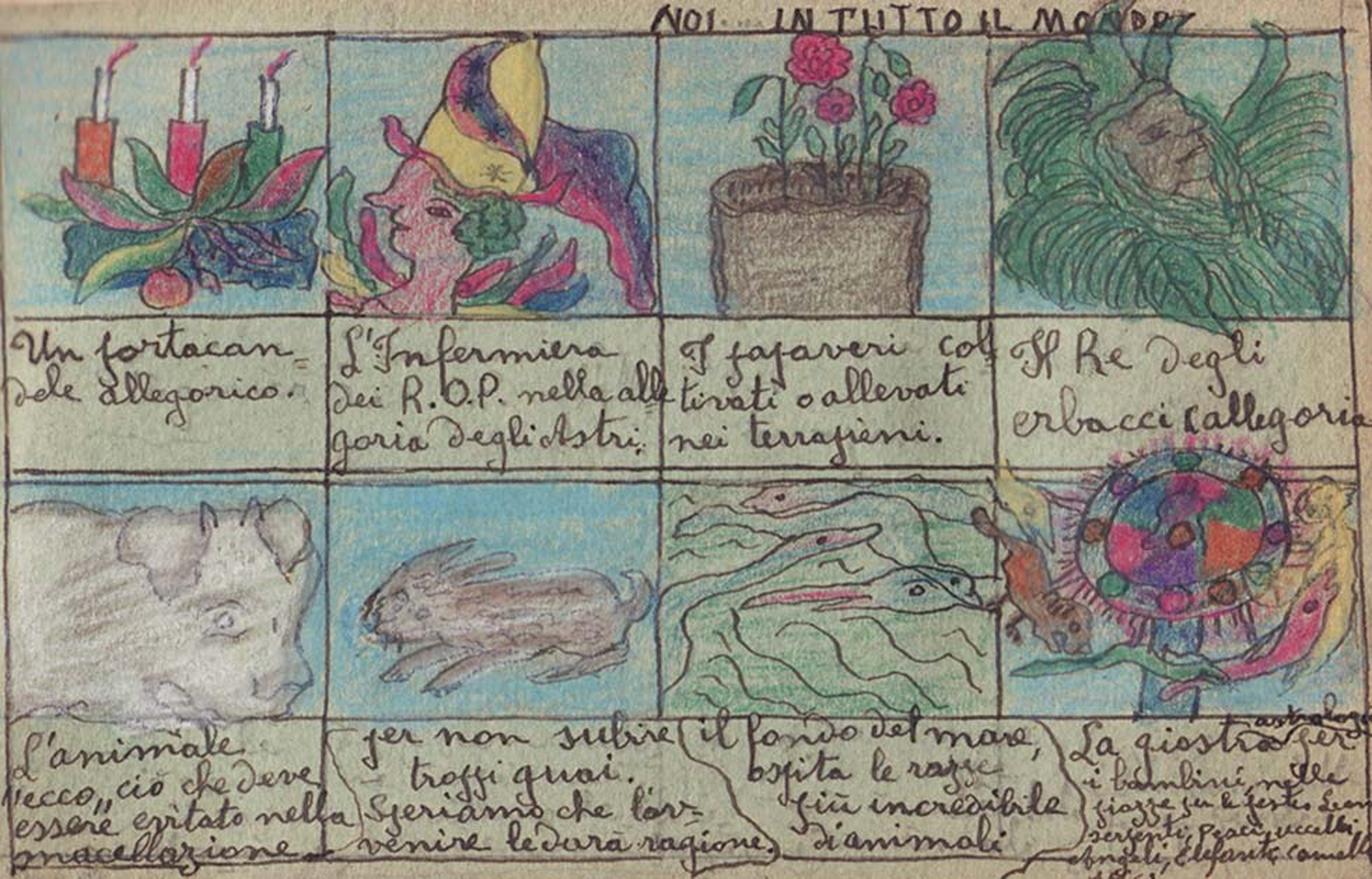

The origins for much of Lombroso's work concerning the specific relationship between artistry and deviancy dates back to the 1870s, when he began to devote serious attention to the artistic output of the incarcerated, the mentally ill and the ‘mattoid’. (The latter was his own devised term for ‘semi-mad’ individuals, including political criminals and revolutionaries, who were not born atavistic but showed psychological abnormalities.) Along with his protégés, his son-in-law Mario Carrara and pupil Giovanni Marro, Lombroso amassed poetry, writings, songs and art objects created by these marginalised groups in collections they called arte brut (also art brut). Many of these works are displayed today in the Museum of Criminal Anthropology and the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography in Turin (Figures 2a and 2b).Footnote 30

Figure 2a. Mario Bertola, Noi … In tutto il mondo [Us … All over the world], a folio from his sixty-page booklet containing illustrations and descriptions of plants and animals (c.1900–10). Bertola was treated in the Psychiatric Hospital of Collegno at the turn of the twentieth century. From the Art brut collection of the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography in Turin. (Colour online)

Figure 2b. Francesco Toris, Il nuovo mondo, sculpture made from animal bone (c. 1900–10). Toris was treated in the Psychiatric Hospital of Collegno at the turn of the twentieth century. From the Art brut collection of the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography in Turin. (Colour online)

Consisting of both practical and ornamental objects, including decorated water jugs, pencil drawings, watercolours, clothing, embroidered fabrics, writings and trinkets made from rags and animal bones, this collection displays works composed exclusively by self-taught artists. While a large number of the works on display were created by inpatients of the Psychiatric Hospital of Collegno around the turn of the twentieth century, many others were created by individuals incarcerated in Italian prisons dating back to at least the 1870s. As noted in L'uomo delinquente and Genio e follia, Lombroso theorised that there was something fundamentally unaffected about the creativity of these individuals because of their atavistic nature; their uncontrived artistic expression contrasted with what he considered the artifice of contemporary high art. He imbues these pieces with primitivistic symbolism by categorising them alongside functional objects (to him, also understood as ‘rough’ art) produced by indigenous communities in North Africa and East Asia. As evidenced in this collection, Lombroso's diagnostic criticism reads as both voyeuristic and exoticist, materialising his interrelated understanding of deviancy, raw creativity and atavism, and thereby blurring the boundaries between art critic and criminal anthropologist.

Through their efforts of curation, Lombroso and his younger protégés not only aestheticised criminals, they also constructed a deviant character type that was disposed to lyrical demonstration. The ‘uncommon writings’ held at the Archivio Lombroso, adjacent to the Museum of Criminal Anthropology, consist of journals, drawings, letters and writings produced by incarcerated individuals from the 1870s through to the 1930s. This collection not only reflects Lombroso's own ideologies but also demonstrates its continuing legacy. Carrara, Lombroso's closest disciple, was responsible for acquiring additional writings for the archive after his father-in-law's death in 1909. Categorised as N. Catalogo: 785 in the archive, the notebook of Sicilian prisoner Gaspare Maggio contains many poems, all of which were composed during the final years of his incarceration from 1875 until 1880 in the San Vito prison of Agrigento in Sicily. Maggio's poems obsessively detail his solitude during his detention:

Over the course of the notebook, a narrative emerges, as Maggio describes his experience as il cammino [the journey] countless times. He details his arrest and transfer to numerous prisons before ending up in Agrigento. The form of his poetry mostly consists of alternating quatrains and octaves, and he frequently makes use of an impure form of the ottava siciliana. Maggio's blend of ruggedness in formal errors and topical matter with clear attempts at erudition fit into Lombroso's idea of the arte brut aesthetic, and this journal was likely collected to contribute to the scientist's theories of criminal literature as developed in L'uomo delinquente.

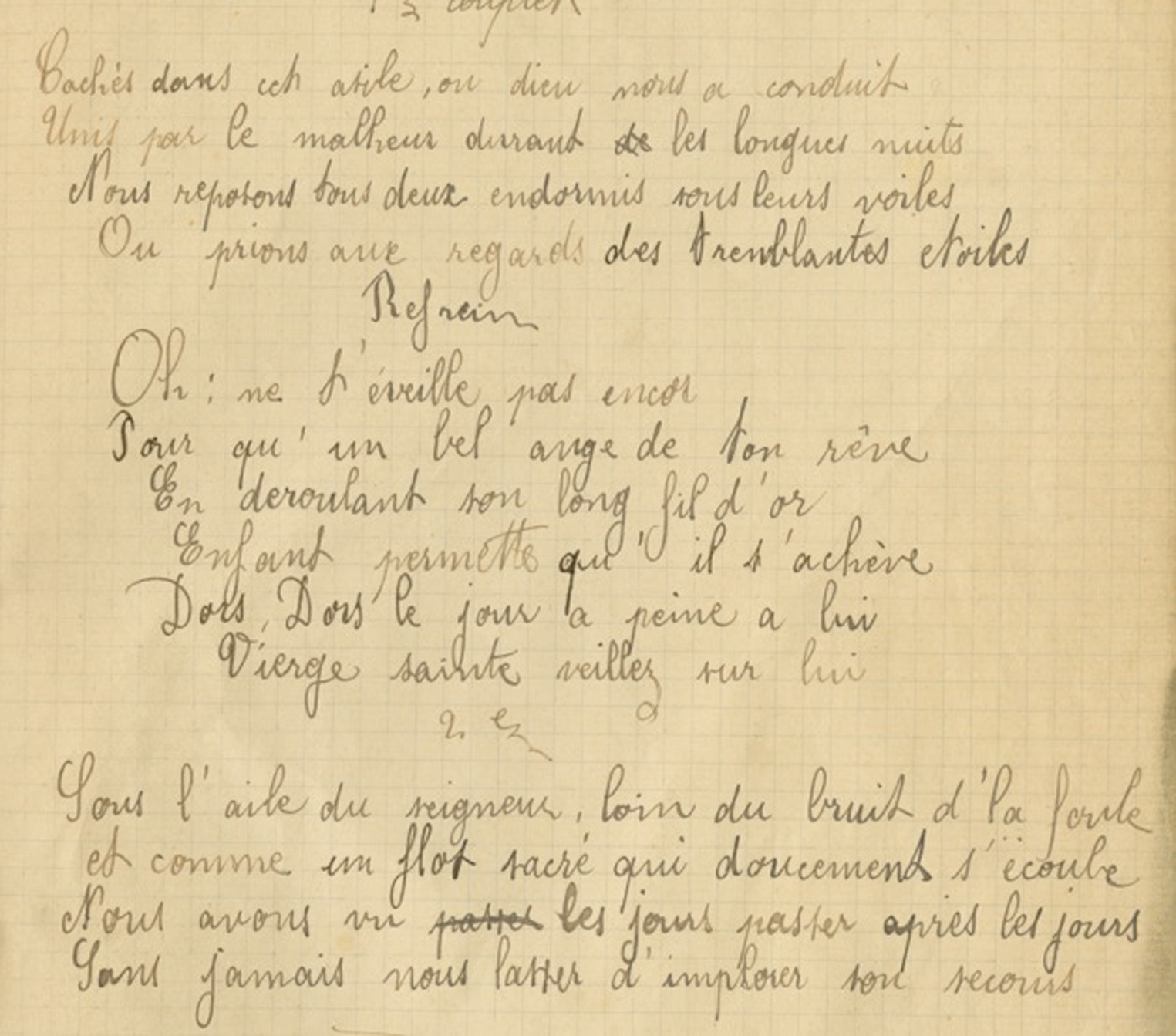

A number of journals from the collection were composed by incarcerated individuals that expressed themselves in a rather melodramatic fashion. N. Catalogo: 807.1 and 807.2, for example, contain the two journals of Alice Valtre, a prostitute, murderer and arsonist who cited operatic verse and popular song to narrate her life. Valtre's archived notebooks, entitled Memorie, pensieri e riflessioni [Memories, Thoughts and Reflections] were written from September 1908 until her arrest for filicide at the end of 1912.Footnote 31 807.1 contains descriptive diary entries and 807.2 contains poems, song verses and cited operatic numbers. Valtre often presented her identity and her circumstances in a dissociative, theatrical manner. In both journals, Valtre alternates writing in French and Italian throughout. Often, her simpler day-to-day recollections are written in French, and her more affected recollections are in Italian. At the beginning of 807.1 two penned sketches of ‘Monsieur et Madame Belcredi’ serve as an introduction to her own life with Imbert, her lover. Within her file and corresponding news reports detailing her trial, no mention of a Belcredi family exists. Given that she immediately launches into a stream of consciousness narrative describing her life with Imbert, Monsieur and Madame Belcredi may very well be fictional, perhaps the couple's alter egos. At moments in this initial section of 807.1, Valtre engages in affected conversations with herself in Italian. For example, she directs her musing towards an imaginary beloved:

And if some cloud accumulates on my soul, and makes life sad and heavy, the memory of you breaks through, like the sun with its rays through stormy clouds. You are the one who illuminates my path. I am sure that the ship of my life will often be beaten by the storm … But do not be sad: it will be me alone that will suffer. You are beautiful, and out in front of you, you can open a path strewn with roses and violets.Footnote 32

In Valtre's mannered writing, she uses redundancies and repetition to accentuate dramatic phrases or idealised visions. Starting on folio 27 of 807.1, Alice's writing takes a turn towards simplicity as her ‘Memorie’ section begins. She shifts into French and offers only brief recollections of her day-to-day life. Here we gain a definitive sense of her disenchanted life. She describes wandering the streets of Turin, sometimes engaging in prostitution. Not once does she mention her son, Leopoldo, whom she abused and neglected. Significantly, however, the last piece she includes in 807.2, her book of poems and verse, is the ‘Berceuse’ from Benjamin Godard's opera Jocelyn (1888) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. N. Catalogo: 807.2, Alice Valtre – Folio 25R, a citation from the ‘Berceuse’ of Benjamin Godard's opera, Jocelyn (1888). Archivio Lombroso, Museum of Criminal Anthropology in Turin. (Colour online)

In this lullaby, the character Jocelyn prays for protection for a sleeping child. It is striking that Valtre includes this text at the end of her notebook, around the same time that she and Imbert were plotting her son's murder. This particular operatic citation presents a moment of aestheticised dissociation for Valtre, while for the reader it provides a stark expressive contrast to the horrific realities of her behaviours and crime.

The materials from the Archivio Lombroso, the Museum of Criminal Anthropology and the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography attest to the theory of Lombroso and his protégés that genius, madness and creative expression are closely related. In such writings, they also aestheticise criminals and highlight their artistic or literary creativity. In one such instance in the first edition of L'uomo delinquente, Lombroso analyses a prisoner's poetry and calls it an ‘exquisite delicacy’ worthy of the likes of Petrarch.Footnote 33 Completing his chapter on ‘Criminal Literature’, impressed that supposedly atavistic deviants could compose commendable verse, Lombroso claimed that such writings stood to voice ‘their boiling passions and enable them to depict themselves and their suffering with extraordinary eloquence’.Footnote 34 Writings such as those by Maggio, Valtre and the anonymous Petrarchan poet, pieces that were typically self-referential or reflective in nature, were used by Lombroso and his followers to illustrate that that certain behavioural qualities were innate to criminals, and in doing so they constructed deviant characters that were inherently dramatic.

Lombroso's influence spreads

Lombroso's criminological work inspired preeminent artists of the time, as he corresponded with a wide range of luminaries. Giovanni Verga and Luigi Capuana met Lombroso in the 1870s and 1880s respectively, and each maintained a close relationship with the scientist until he died in 1909. Verga was drawn to his theories of deviant personae: Vito Moretti has claimed that he was inspired by Lombroso's ‘positivistic’ thinking, and in particular his ‘biological theories of correlation between physical phenomena and the worlds of thinking or acting’.Footnote 35 Hiller has more pointedly argued that Lombroso's ‘social-Darwinist vision of Southern Italy and its people’, as well as his theories of the born criminal and the female prostitute, shaped Verga's characters in a number of his works set in the Italian South.Footnote 36 These include a volume of short stories about Sicilian peasant life entitled Vita dei campi (1880), which contained Cavalleria rusticana, the foundation for Mascagni's eponymously titled opera, and the novella La lupa [The She-Wolf], a text that Giulio Ricordi commissioned Verga to adapt as a libretto for Puccini in the early 1890s. Puccini set a great deal of this libretto to music and visited Verga in Catania, where he took many photographs for inspiration, although ultimately it was not completed.Footnote 37 Verga's other notable texts inspired by Lombroso's ideologies include I malavoglia and Maestro-don Gesualdo (1889), both of which formed part of his unfinished I vinti (Il ciclo dei vinti), a projected five-novel cycle detailing man's struggle. After Verga's death in 1922, Lombroso's extensive series of publications was found on his bookshelves at his home in Catania, together with criminological and anthropological texts by his contemporaries.Footnote 38 Capuana worked with Lombroso on a number of scientific projects in the 1880s and 1890s, including notorious forays into hypnotism involving the exploitation of impoverished citizens in Capuana's hometown of Catania.Footnote 39 The two men shared a keen investment in spiritualism, and their collaborative work inspired Capuana's 1884 essay Spiritismo?, as well as the dedication of his later novel Un vampiro (1907) to Lombroso. Other high-profile writers influenced by the criminal anthropologist include Émile Zola, Arthur Conan Doyle and Edmondo De Amicis. The latter was a long-time friend and collaborator, and the scientist and the writer cultivated a professional relationship from at least 1880, when they were planning a conference in Turin about the psychological effects of wine, specifically the connections between excessive drinking and criminal behaviour.Footnote 40 They published the proceedings of this meeting in a co-authored book, Il vino: anima e psyche [Wine: Soul and Psyche]. In 1886 De Amicis wrote the children's novel Cuore, which secured him lasting popularity. During its early reception Cuore was sanctioned by the Italian state as an important educational text for young readers, as it promoted virtues considered key to developing a cohesive national identity. Throughout the novel De Amicis incorporated Lombroso's physical stereotypes of Italian southerners to distinguish particular characters. In an attempt to reach beyond northern readers, who could sympathise with the protagonist who was a young schoolboy from Turin, De Amicis created the character of Coraci, a Calabrian boy who stands out from his northern peers for his dark skin and striking physical attributes. Coraci's racialised features – which his peers repeatedly note – echo Lombroso's descriptions in L'uomo delinquente and the more explicit L'uomo bianco e l'uomo di colore [The White Man and the Man of Colour].Footnote 41

De Amicis develops his attitudes towards the Italian South in a 1904 essay entitled ‘La musica mendicante’ [‘Vagrant Music’]. In addition to promoting the unsavoury and criminal stereotypes amidst the pastoral beauty, he describes a penchant for noisiness as further evidence of a lack of cultivation. Throughout the essay – which reads at some moments like an ethnography and at others as a meditation – the author conveys in colourful language his own scattered glimpses of southern Italy:

All the illnesses, all the deformities, all the aspects of misfortune and pain come from everywhere: … to the Sicilian boy who travels on foot, singing to the whole peninsula, and with his first notes makes me raise my head as if [seeing] the sudden vision of a blue gulf crowned with forests of oranges. And all the appearances of poverty and ruin, all the signs of the troubled life of a stray, even in the instruments; all the voices of exhaustion and anguish in the sounds of those forgotten violins, of those scraping harps, of those screeching guitars, of those accordions that bleed, of those trumpets and those coughing and whistling flutes, of those tambourines … it seems as though they ask for pity from the tired hand that strikes them.Footnote 42

De Amicis invokes vocality and sound throughout his narration in order to create a cohesive identity of Italy from his varied recollections of these rustic, disenfranchised spaces. He hears beggars as the ‘dying voices of tenors’ and impoverished individuals ‘singing’ with hunger.Footnote 43 A ‘soprano’ carries a note from a window near a noisy restaurant, while a ‘dense aria from comic opera’ resounds when money falls on the cobblestones of a community inhabited by ‘emaciated men’, ‘thieves’ and ‘tattered, pretty little girls’.Footnote 44 His brief vignettes, set in both bucolic towns and city streets, paint an image of contemporary Italy as not only musical but inherently operatic. Yet, as he continues, De Amicis draws attention to the simultaneity of artistic vocality and common noise that characterises these scenes:

While the artist plays or sings, the servants beat the carpets, the cobbler pounds the sole, the blacksmith beats on the anvil, the hurried people go up and down the stairs shouting; wagons and carts enter and leave; the voice of the ‘virtuoso’ is overwhelmed by the cry of the walking pedlar of pulses or brooms; the verses of the romance that speaks of love, of the moon and of paradise rise in the air full of the vapours of laundry, and mix in the open rooms with the clatter of dishes … with all the most prosaic miseries of tiresome daily life. Alas! Alas! What hard contrasts and what bitter derision!Footnote 45

Closing his rumination, the ‘voices and instruments of ear torture’ that De Amicis describes throughout impress him with a sense of ‘thoughtful, loving admiration’ rather than ‘irritation against the art they outrage’.Footnote 46 The sounds of music and the noises of life create for the author a novel, desirable form of sonic and lived expression, an amalgamation of noisy stereotypes with the cultivated musicality of the nation's heralded art form of opera.

De Amicis not only intensifies regional and character-oriented stereotypes promoted by Lombroso and his literary colleagues, but also responds to concerns about operatic sound raised by critics of verismo over the previous decade and a half. In fact, soon after the premiere of Tosca in 1900, De Amicis had endorsed Puccini as a force of Italian regeneration in an article for the Argentinian newspaper La prensa, a piece that was then reprinted in L'illustrazione popolare in Milan.Footnote 47 While De Amicis views the juxtaposition of romanticised operatic voices and the brutal naturalistic sounds of a lower-class Italian environment in a positive light, a number of music commentators who observed such coarseness on the operatic stage itself were much more displeased by the results in practice. Writing for the Gazzetta musicale di Milano, Vito Fedeli laments:

The works of the young modern composers all resemble one another. Almost all of them have that uniformity of confused melodic-instrumental polyphony, that chaos of disconnected modulations, that infinite variety of little melodic ideas, badly developed if at all, which taken together betray the extent of a composer's uncertainty. He seems caught between old traditions – the binding aesthetic values with which he was raised – and the feverish desire to improve art itself by discovering the new path towards which recent progress and the needs of the public must point.Footnote 48

Fedeli summarises key criticisms of the operatic verismo movement. He questions how Italian opera could simultaneously evoke realism, voice a modern, nationalistic attitude, and still articulate the celebrated melodic beauty that for generations had characterised the tradition. In his view, the giovane scuola had failed to a certain degree. He viewed their stylistic changes to the Italian operatic tradition as haphazard and as a sign of compositional immaturity. Stylistically, as he suggests in the passage above, verismo operas often feature expansive orchestral forces, a breakdown of versification, and greater use of open forms, all of which create greater naturalistic flexibility of expression and dramatic continuity. Like many others, Fedeli found these resultant naturalistic features somewhat unpleasant and aesthetically irreconcilable with the traditions of the past.

Something old, something new? The trouble with Tosca

Never was this particular criticism of operatic verismo more relevant than in reviews of Puccini's Tosca. Though written ten years after the initial craze of operatic verismo launched by Cavalleria rusticana in 1890, Tosca maximises the stylistic and character-oriented innovations of the movement that were set in motion during the previous decade. Tosca prompted polarising responses from journalists and critics. While many celebrated Puccini's take on the verismo style in Tosca, many were scornful. Furthermore, critics called into question the increasingly trite nature of operatic deviants and their seemingly conventional handling at the dawn of a new century. But rather than regarding this shift in attitudes as a response to compositional shortcomings, as Fedeli proposes, or to stylistic derivation, we can get closer to the heart of the realist vision of this repertoire by engaging with contemporary criminological views as conceptualised by Lombroso and his literary followers, specifically those concerning the expressive modalities of Italy's deviant populations.

Concluding his review of Tosca's January 1900 premiere, Luigi Torchi declared: ‘Strong subjects such as Tosca do not agree with Puccini's ingenuity nor with his temperament … With Tosca, [Puccini] did not compose an original work. He has run into kaleidoscopic manipulations of style, which extend throughout the Wagner–Massenet range; he has not told us anything new, perhaps because he has nothing to say to us again in this genre.’Footnote 49 The flat nature of the opera's characters displeased many commentators from both a narrative and musical standpoint. Puccini's aspirations for scenic authenticity in Tosca were manifested largely in his construction of a realistic Roman soundscape, an effort achieved through studies of the Vatican's sacred rituals, the sound of cathedral bells and local dialect.Footnote 50 Hearing past the opera's novel if unwelcome din of Roman bells, Torchi and other progressive critics of the time perceived in Tosca abhorrent, superficial clichés rather than sympathetic, heroic characters, as Alexandra Wilson has noted in her study of the opera's early reception.Footnote 51 Torchi's objections boiled down to two significant observations. First, Tosca comprised a hodgepodge of conventional and odd modes of expression. Second, and more importantly, the opera's ‘strong subject’ of scandalous deviancy and criminality that dissatisfied the majority reflected contemporary fears about the moral decay that plagued much of Italian culture.Footnote 52 Critics were specifically dissatisfied with the characters’ modes of musical expression: through the unsavoury guise of stylised operatic verismo they heard masked archetypes rather than feeling, heroic characters. While many critics attributed Tosca's dark tone to its French source, Victorien Sardou's melodrama La Tosca, the Italian fascination with criminology underlies both the dramatic and the musical unsavouriness of Puccini's opera.

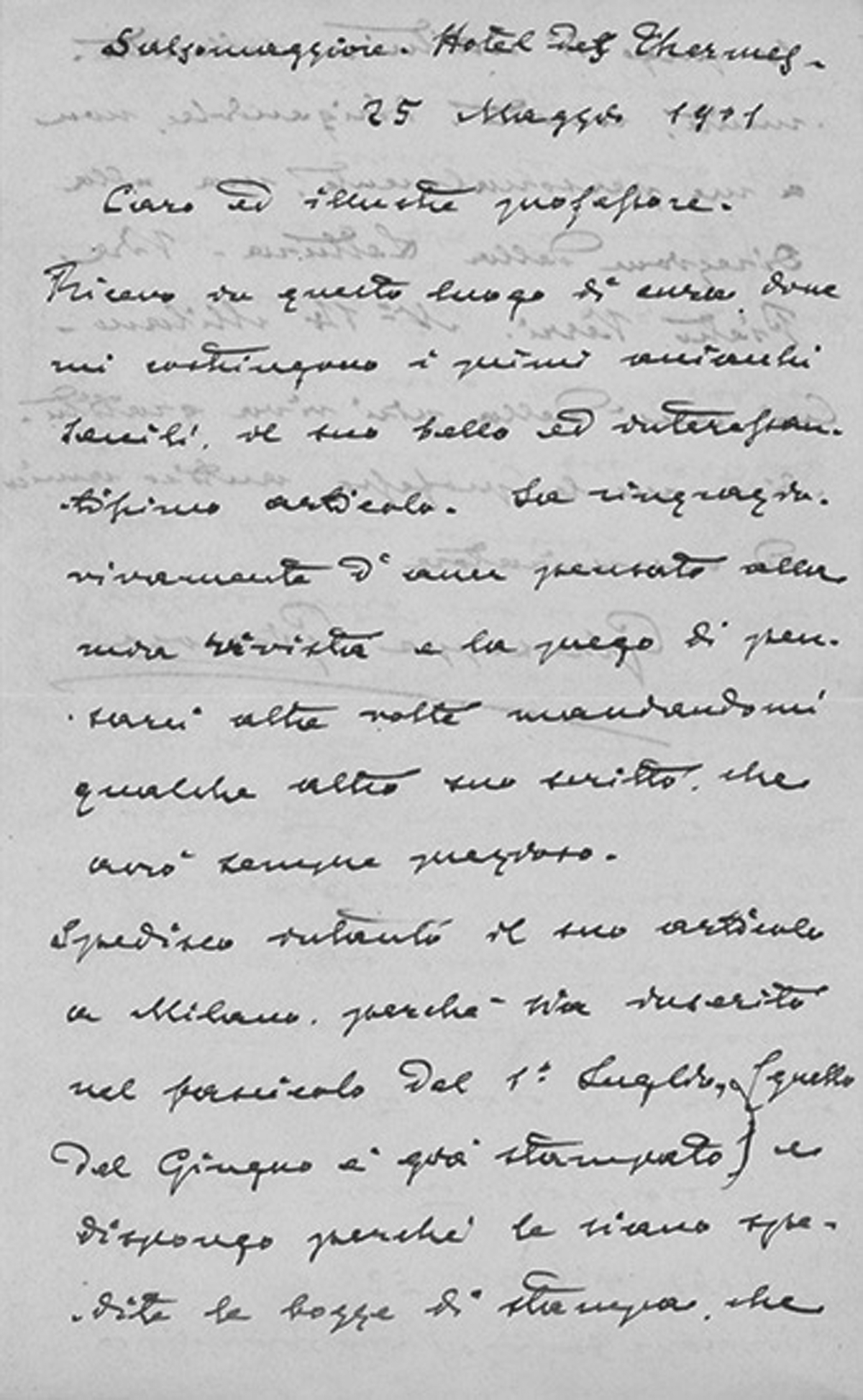

Given the mass popularity of Lombroso's positivist theories amongst the Italian public by the turn of the century, it comes as no surprise that an opera so centred on deceit, criminal action and violence featured contemporary archetypes of deviancy. Documents from the Archivio Lombroso further show that some of the key creative figures of Tosca had connections to Lombroso. Max Nordau, the author of the widely acclaimed 1892 text, Entartung [Degeneration], which was dedicated to Lombroso, wrote a letter to the fellow physician dated 11 February 1897. In the note Nordau celebrates the Italian physician's widespread popularity in France and shares that Sardou commemorates Lombroso's spiritualist works with at least two explicit references in his play Spiritisme (1897).Footnote 53 Archived letters also show that Giuseppe Giacosa, the co-librettist of Tosca, had a relationship with Lombroso that spanned at least twenty years, from 1880 to 1901 (Figures 4a and 4b).

Figure 4a. IT SMAUT Carrara/CL. Giacosa, Giuseppe. 5A. This is an excerpt of a letter dated 3 November 1880 from Giacosa to Lombroso. Archivio Lombroso, Museum of Criminal Anthropology in Turin. (Colour online)

Figure 4b. IT SMAUT Carrara/CL. Giacosa, Giuseppe. 5B. This is an excerpt of a letter dated 25 May 1901 from Giacosa to Lombroso. Archivio Lombroso, Museum of Criminal Anthropology in Turin.

Lombroso and Giacosa's correspondence details reunions with colleagues, recollections of conferences they both attended and introductions amongst friends during their travels, suggesting both a friendship and professional relationship.Footnote 54 Beyond the documented connections between Lombroso and Tosca's literary collaborators, aspects of contemporary criminology exist not only in Tosca's plot – filled with criminals, political revolutionaries and a murderous diva – but in Puccini's musical techniques as well.

Objective lyricism: the case of Cavaradossi

The process of transforming Sardou's five-act melodrama into a three-act opera was, of course, an act of reduction; yet as librettists Giacosa and Illica reconfigured Cavaradossi's part to accommodate Puccini's lyrical moments, his character came to more clearly resemble Lombroso's archetype of the mattoid. As Lombroso describes in L'uomo delinquente, the mattoid is – unlike the born criminal – more difficult to identify because his deviancy consists of obsessive or eccentric self-expression rather than specific physical attributes.Footnote 55 Lombroso found this type most often among political revolutionaries. With ‘their exaggerated sense of their own worth’, he wrote, like ‘monomaniacs and geniuses, mattoids seem to espouse serious ideas’, yet their expression is marked by ‘absurdity’, ‘prolixity’ and ‘trivialities’.Footnote 56 As Puccini and his librettists edited Sardou's play, they cut the descriptions of Angelotti and Cavaradossi's relationship, their backgrounds and their shared political views, and introduced some dramatic shortcuts. For example, in the play, the two anti-royalist Republicans had never before met, and develop a friendship within the diegesis; in the opera, they know each other already. One of Giacosa's primary tasks was to provide space for lyrical moments, and in doing so, he transformed the nature of Cavaradossi's character. Sardou's Cavaradossi is far more level-headed and stoic than his operatic counterpart. Puccini's Cavaradossi participates in lyric expression on a par with the singer Tosca throughout the opera, but in an ‘unconscious’ mode that captures the archetype of the mattoid. Though time is constantly of the essence in Tosca, Cavaradossi manages to wax poetic in the elaborated text for ‘Recondita armonia’ in Act I, ‘E lucevan le stelle’ in Act III, and following the duet ‘O dolci mani’.

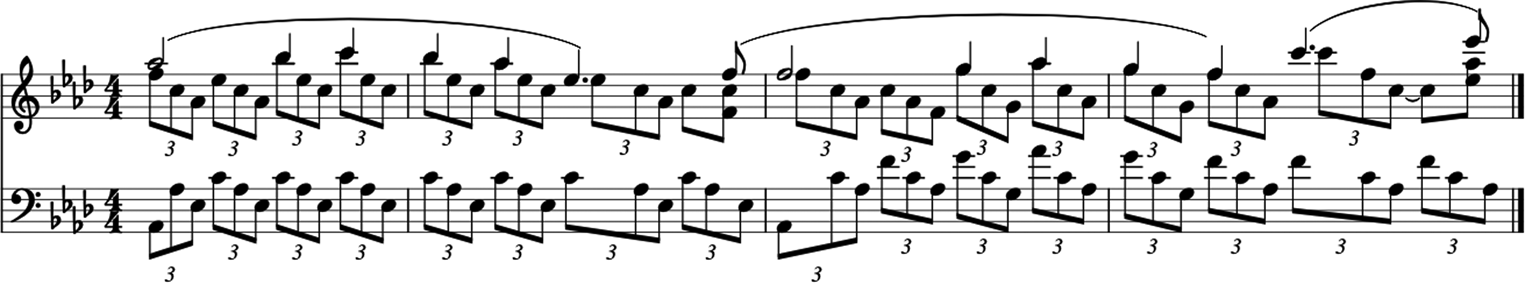

Puccini's writing accentuates Cavaradossi's new poetic nature with indulgent lyricism that resembles La bohème's Rodolfo far more than the voice of an ardent revolutionary. His effusive singing in ‘O dolci mani’ illustrates his shift of character (Example 1). As Cavaradossi awaits his impending execution, Tosca comes to see him, and with urgency she shares the news of Scarpia's murder and their safe conduct. Cavaradossi then rhapsodises over Tosca's sweet hands in an andantino sostenuto in 3/4 time: his arpeggiating phrases in F major, starting on pick-ups or weak beats of the bar, evoke self-indulgence. Swept into his own poetics, his line briefly shifts into a 2/4 time in the parallel minor in a heroic, declamatory style. An orchestral reminiscence of the music that accompanied Tosca and Scarpia's safe conduct agreement is then heard loudly in F minor, prompting Cavaradossi to soar over the orchestra before returning to his original arpeggiated melody, initiating another episode of rhapsodising.

Example 1. Puccini, Tosca, reduction of ‘O dolci mani’, Act III.

The poetic form of the text resembles the beginning of an Italian sonnet, an uncommon poetic form in Italian opera.Footnote 57

While the eight lines of the aria do not use the iambic pentameter of the traditional sonnet form, the aria contains two quatrains with an ABBA rhyme scheme, which enhance the self-consciously poetic nature of the piece. Interrupting Cavaradossi's indulgent verbosity at such an inappropriate time, Tosca demands that he ‘listen’, an ironic instruction given that she is the celebrated singer. In more succinct lyrical phrases, she shares the practical details of their imminent escape. This scene conveys Cavaradossi's seeming obliviousness to the urgency of his predicament: he is fashioned into an oddly poetic revolutionary, obsessed with immediate expression more than political justice. Not only can we hear Cavaradossi's music as a testament to the expressive capacity of the contemporary mattoid, we can also complicate the notion that lyricism was utterly incompatible with the project of Italian realism by situating his mode of expression within prevalent scientific theories.

Tosca's Tatuaggi: Scarpia's inscriptions of deviance

Like the role of Cavaradossi, Scarpia's part was expanded to greater lyrical proportions, which had an impact on his characterisation. In both the original play and the opera, Scarpia's nefarious reputation precedes him. In the opening exchange between Angelotti and Cavaradossi in Act I of Puccini's opera, the latter scorns Scarpia as ‘a bigoted satyr who indulges his lecherous desires under the guise of religion, and makes both the confessor and the hangman the servant of his wantonness!’Footnote 58 In Sardou's play, Scarpia's notorious reputation and criminal background are detailed far more extensively in these initial exchanges between Angelotti and Cavaradossi. Upon mentioning Scarpia in conversation with Cavaradossi in Act I of the play, Angelotti connects the Sicilian Baron with the Neapolitan brigands Mammone and Fra Diavolo, and calls him ‘a real monster who bore holes in the throats of his victims’, suggesting a more serious vision of Scarpia's criminal background than even Puccini's opera offers.Footnote 59 As Lombroso points out, unlike more modernised nations where violence amongst gangs and brigands had decreased by the end of the nineteenth century, banditry continued to plague Italy, particularly in the southern regions of the peninsula. What concerned the scientist most from a criminological stance was that brigands – a type of born criminal – committed atrocities intended to harm the nation's social institutions, civil establishments and citizens.Footnote 60

In a letter sent to Giulio Ricordi on 14 December 1896, Giacosa voiced his annoyance at compromises he had to make with Puccini in order to expand Scarpia's expressive role in the opera. He writes, ‘This Scarpia, who wastes time describing himself, is absurd.’Footnote 61 Giacosa's major additions include Scarpia's Act I monologue and the erotically charged ‘Ha più forte sapore’ and ‘Già. Mi dicon venal’ in Act II, which together accentuate the Baron's dishonest and lustful nature. Specifically, as he divulges to Ricordi in the same letter, Giacosa found the Baron's eloquent, lyrical treatment in ‘Ha più forte sapore’ ill-suited to such a model villain, and claimed that a deviant character – even one that is technically an aristocrat – should express himself not in words but in actions. Like Giacosa, Torchi too was critical of the composer's use of lyrical expression for the character of Scarpia. He observes:

And Scarpia – what characterises him musically? Only his motif, the thematic motif that takes its name from him. In his sentimental and erotic outbursts, always expressed with exaggerated emphasis, he is neither more nor less than a usual lyrical baritone, like Tosca is neither more nor less than a typical prima donna. No one can find in him the expression of his horrendous human nature, when he reveals himself as a hypocrite and a libertine. His lyric outburst is, for that very reason, always exaggerated and false.Footnote 62

While Torchi criticised Puccini's musical depiction of Scarpia, claiming that the Baron lacked an expressive sense of cruelty because of his false modes of lyrical expression, he regarded the character's crude motif as an appropriate defining gesture through its voiceless expression. For both the librettist and the critic, this coincides with Lombroso's basic tenet that the deviance of a born criminal should first and foremost be readable through the body's presentation.

Yet while Giacosa and Torchi complained about the unconvincing lyrical trappings of the opera's villain, Puccini nevertheless evoked Scarpia's inherently sinful character through his effective use of leitmotif. As the curtain rises for Act I, Scarpia's motif blasts through the orchestra, a dense series of chords built on a whole-tone scale. The theme's rough-hewn harmonic motion – from B flat to A flat to E major – offers erratic, sensational energy, but without distinct character (Example 2).

Example 2. Tosca, Act I opening, Scarpia's leitmotif.

The theme's next iteration, a bombastic accompaniment to Scarpia's entrance in Act I, ‘Un tal baccano in chiesa!’, offers further clarity. In this scene, he provokes fear amongst all present; the Sacristan, as the stage directions dictate, cowers and stammers frightfully in his presence. As heard in the following syncopated lines of the violins and violas, the harmonic remnants of his motif echo and dissipate through the church as the choir members scatter away from him. Scarpia's motif remains largely unchanged until his death scene at the end of Act II. After he is stabbed in the middle of the number, ‘E qual via scegliete?’, his motif (transposed down a tone) gently unfolds and slackens, not through a change of heart, but through sheer corporeal decay (Example 3).

Example 3. Tosca, Act II, from ‘Tosca, finalmente mia!’ (Scarpia's death scene). Scarpia's leitmotif appears in strings, marked in brackets.

In this moment, these chords serve as a kind of bodily or physiognomic sign rather than a lyrically expressive device. In contrast, Cavaradossi's and Tosca's leitmotifs depict their characters with expressive nuance, as melody is their primary device of recognition (Examples 4a and 4b). Furthermore, their leitmotifs transform in subsequent reappearances, as they are either sung, or their contour, accompaniment or harmonies are changed. In contrast, with its static nature and lack of expressive, melodic character, Scarpia's leitmotif defines him as a fixed, soulless archetype.

Example 4a. Tosca, Act I, reduction from ‘Mario! Mario! Mario!… Son qui!’ Tosca's leitmotif.

Example 4b. Tosca, Act I, from ‘Un tal baccano in chiesa’. Cavaradossi's leitmotif.

Scarpia's leitmotif arguably serves as a two-fold metaphor for the criminal tattoo – forming both an inscription of an archetypal self, and a sensational etching on the body to express its vices. As evident in L'uomo delinquente, Polemica in difesa della scuola criminale positiva and collected photographs preserved in his archive, Lombroso considered criminals’ tattoos as a significant means of reading deviancy on the body. ‘Tattoos are external signs of beliefs and passions,’ he remarked succinctly in the first edition of L'uomo delinquente.Footnote 63 Stock themes emerge from Lombroso's studies of the tattoo, including love, lustful obscenities, war, religion and references to criminal acts, especially amongst brigands. Considering the evocative nature of Scarpia's name, we can gain further insight into the layers of inscription written onto the Baron's criminal character. Scarpia – a close play on the Italian verb scarificare – to ‘scarify’ – suggests, if coincidentally, not only the capacity to invoke fear but also to make shallow incisions in the skin. The sound of Scarpia, built of a crude, unfeeling design, marks his crimes and his vices in a similar manner to his non-fictional, decorated counterparts. In L'uomo delinquente, Lombroso even likens notes in a musical chord to the abnormalities of the criminal's physicality and appearance. He claims that, ‘As a musical theme is the result of a sum of notes, and not of any single note, the criminal type results from the aggregate of these anomalies, which render him strange and terrible, not only to the scientific observer, but to ordinary observers who are capable of an impartial judgment.’Footnote 64 In light of this comparison, we might consider Scarpia's strange motif – an aggregate of anomalously arranged chords – as the sonic manifestation of this assembled criminal type. The dissonant chord, composed of many sonic facets that create a striking whole, resembles the varied characteristics that create this iconic decipherable criminal.

By reconceptualising Tosca with our retrospective gaze as a crystallisation of larger sociocultural and scientific projects within a unified Italy, we might broaden our understanding of how social and musical conventions carried modern meanings in their verismo afterlife. History repeats itself time and time again in Tosca, well beyond the opera's scandalous historical drama. Puccini's use of romantic lyricism and leitmotif on the one hand, and Lombroso's appeal to a mass public through the integration of conventional wisdom on the other, allow us to hear, see and conceptualise the opera's recycled and reinvented tropes. As the sounds and ideals of previous generations influenced Puccini's opera, it is no wonder that progressive critics such as Torchi viewed Tosca as a regressive work not only in the composer's repertoire but in the tradition of Italian opera more broadly. After all, since its inception ten years earlier, ‘operatic verismo’ had been considered by many an aesthetic contradiction because of its stylistically derivative nature.

Yet the musical shortcomings of verismo were not solely a failed aspiration for sonic or stylistic modernity through the mapping of conventional precedence onto shocking, criminal narratives. As seen and heard through Tosca, the archetypes of deviancy that affected both Puccini's opera and the popular imagination were instead somewhat antiquated and flawed. In their efforts to locate the organic causes of deviancy, Lombroso and his positivist colleagues undermined themselves. They did so by qualifying and quantifying criminals through the very subjectivity of their ‘deviant’ artistic expression as well as their individualistic modes of bodily presentation. Thereby, Puccini's lyrical or inscriptive, ‘leitmotivic’ characters read as contemporary musical manifestations of objective deviants. In this light, perhaps operatic verismo is not quite the oxymoron it has seemed.