Following a journey to Ireland in 1847, the Quaker William Bennett expressed his fear that the British public was becoming inured to accounts of extreme hunger, noting disconsolately that the word “STARVATION . . . has now become so familiar, as scarcely to awaken a painful idea” (132). His concerns were not without foundation. During the 1840s, a decade that has come to acquire a special connection with “hunger” in historical discourse, column upon column of newsprint was dedicated to the topic, as a catalogue of contributory factors – bad harvests; prolonged economic depression; protectionist policies, such as the notorious Corn Laws; an austere Poor Law (dubbed the “Starvation Act” by its opponents); and, from 1845, a catastrophic famine in Ireland – combined to politicise questions of access and entitlement to food. Given this context, it is hardly surprising to find that hunger figured as an insistent, though contentious, issue within early-Victorian print culture, generating a mass of commentary and debate. As Peter J. Gurney has pointed out in a recent article on the politics of consumption in the “Hungry Forties,” “the struggle over the representation of scarcity was particularly acute during this crucial period,” as depictions of want were strategically deployed by newspapers associated with a variety of competing factions and interest groups, especially those, such as the Chartists and the Anti-Corn Law League, who were keen to instigate political reforms (101).

It is important to recognise, however, that concerns about hunger were not confined to the working-class or radical press. In this essay, I want to consider hunger and, in particular, the problem of its representation in a selection of early-Victorian periodicals that targeted a readership with little direct experience of its visceral pangs: the prosperous middle classes. During the 1840s, several new, illustrated weeklies, designed to appeal to this group of readers, came to prominence.Footnote 1 Similar in certain respects to modern magazines, these versatile, multi-media publications aimed to amuse and entertain, but also to provide commentary on some of the most pressing social issues of the day, including pauperisation and starvation. Critical studies have drawn attention to this social reportage, but have tended to focus narrowly on a single publication, the commercially successful Illustrated London News (ILN), or its coverage of the Irish Famine.Footnote 2 My intention is to broaden the scope of previous enquiries, examining representations of hunger from the ILN alongside those from some of its competitors in the middle-class market: Punch, the Pictorial Times and the Lady's Newspaper.Footnote 3 I also want to reconnect portrayals of the Irish Famine with depictions of English working-class hunger in order to demonstrate that the highly patterned (though often ideologically contested) iterations of hunger which recur, both visually and textually, in the illustrated periodicals of the 1840s form a kind of representational paradigm: taken together, they reveal the general challenge inherent in “making present” a condition experienced by its sufferers in terms of diminution, absence or lack, while also contending with the specific problem of re-presenting the somatic experience of hunger to members of a social class largely detached from its miseries. The critic Elaine Scarry notes that

when one hears about another person's physical pain, the events happening within the interior of that person's body may seem to have the remote character of some deep subterranean fact, belonging to an invisible geography that, however portentous, has no reality because it has not yet manifested itself on the visible surface of the earth. (3)

This essay will explore the ways in which early-Victorian periodicals attempted to bridge this experiential divide and make “real,” by textual or visual means, the pain of other people's hunger.Footnote 4

Notably, during the 1840s, a growing consciousness of the difficulty of portraying the realities of hunger to a well-fed audience gripped the middle-class media. On a number of occasions, leading daily newspaper the Times conceded that stories about “death by starvation” were both alien and alienating to its readers. An article published in December 1846 prefaced its account of the death of Joseph Woodward, a two-year-old child from the parish of St. Pancras, with a lengthy (and rather pointed) apology:

We are aware that there exists in many minds a decided aversion, fostered into a comfortable state of incredulity, to all mention of extraordinary suffering. Not only do we make ourselves exceedingly troublesome by thrusting on our readers such incidents as death by starvation, but we subject our columns to many a charge of being brimfull of lies. . . . When the broad sheet of The Times . . . emerges at . . . the genial precincts of the breakfast-table, a column of small print headed “Another death by destitution” . . . comes rather like a wet blanket on the warm curiosity of the gentleman in a dressing-gown, with a devilled drumstick on his plate, and a game pie in reserve. (“London, Tuesday, December 1, 1846” 4)

Three weeks later, the newspaper was obliged, once again, to apologise for bringing “this painful subject” to the notice of its sated readership:

It cannot be more irksome to our readers that we should be continually harping on the same subject, than it is painful to ourselves to be compelled to regard “death by starvation” as one of the standing topics for our leading columns. (“London, Wednesday, December 23, 1846” 4)

The Times’ suspicion that hunger was a topic distasteful to the affluent middle and upper classes seems to have been shared by the hungry themselves. In his memoirs of the Irish Famine, survivor Hugh Dorian encapsulated the newspaper's anxieties about widespread ambivalence toward working-class malnourishment in a neat aphorism: “the satiated never understand the emaciated” (223).Footnote 5

Yet, whether successful or not, efforts to “understand the emaciated” were repeatedly made in the print culture of the 1840s in a variety of textual and visual forms. Unlike daily newspapers such as the Times, the weekly illustrated periodicals on which I wish to concentrate here were not limited to straightforward reportage in their accounts of privation. Marketing themselves as miscellanies with a remit to entertain as well as inform, and with the advantage of a production time that enabled the inclusion of multiple engravings alongside text, these publications frequently supplemented their prose writings on hunger with pictorial and/or poetical representations. Focusing specifically on these forms, I want to explore what is at stake in their deployment: what did images and poems about hunger offer to middle-class readers that conventional, “factual” journalism did not? What kinds of strategies did these representations draw upon to engage but also placate the readers the Times feared it was antagonising with its unpalatable reports on poverty? As one might expect, the tone and purpose of representations of hunger could vary according to the demands of different target readerships; yet, often, a complex and protean picture emerges in which publications confound easy assumptions about stance and approach. For instance, the overtly political, three-penny Punch was renowned for taking broad, satirical swipes at establishment figures and their ineffective responses to poverty in its poems and cartoons, but, in addition to this burlesque content, its early editions contained some surprisingly sensitive poetic offerings on the situation of the English working poor. Indeed, its representations of hunger often evinced greater compassion and empathy than those located in the female- and family-orientated Lady's Newspaper, Pictorial Times, and ILN (all priced at 6d.), for, although these publications had an interest in presenting sentimentalised illustrations of human suffering, owing to the perceived expectations of their readers, their sympathy for the hungry was often muted by an underlying political conservatism. Ambiguities and inconsistencies could also emerge within periodicals as middle-class attitudes to hunger shifted or mutated in response to specific political crises. R. F. Foster points out that, during the years of the Irish Famine, Punch's sympathy for the starving diminished as Irish support for the rebellious Young Ireland movement grew (178-80).Footnote 6 Highlighting such oscillations and vagaries, this essay will examine the contradictory ideologies that surrounded “hunger” in the 1840s and consider whether the inscription of the condition in image and verse worked ultimately to vivify or distance its effects for middle-class readers.

Hunger and Ideology

Modern historical scholarship has sought to re-evaluate understandings of the “Hungry Forties,” pointing out, for instance, that this label is in fact a retrospective one, originating in the early twentieth century when it was coined as part of a propaganda drive against protectionist tariff reforms.Footnote 7 However, as Gurney insists, this critical reassessment “should neither obscure the fact that a great many working people suffered . . . nor lead us to underestimate the political centrality of the debate on hunger” between 1840 and 1849 (101).

Of course, hunger at this time was nothing new. Food historian John Burnett points out that “the whole of the first half of the nineteenth century was miserably hungry for many,” implying that the “Hungry Forties” should be read as part of an historical continuum rather than as a disruptive, but transitory, aberration in the narrative of nineteenth-century progress (35). Indeed, were I to broaden the scope of this enquiry and attempt to map the incidence of famine and starvation across epochs and nations, it would become tempting to position hunger as a universal feature of human society, a natural and timeless phenomenon which is, in the words of Sharman Apt Russell, “as big as history” itself (15). However, as James Vernon points out in his excellent cultural study of the condition, “hunger's perpetual presence and apparently unchanging physical characteristics belie the way in which its meaning, and our attitudes toward the hungry, change over time” (2). He elaborates,

We have all known, however briefly and superficially, what hunger feels like. . . . Hunger hurts, but . . . how it has hurt has always been culturally and historically specific. We need to take seriously the very slipperiness of hunger as a category, for the modern proliferation of terms signifying its various states – ranging from starvation to malnutrition and dieting – bear witness to its changing forms and meanings. (7–8)

Hunger, then, is both material condition and cultural construct; viscerally grounded in bodily reality, it is also subject to the transformative effects of history and signifying practice.

Representations of the sustained and sometimes life-threatening hunger experienced by the indigent and labouring poor in the 1840s – the kind of hunger on which this essay will focus – make manifest the fluidity and complexity described by Vernon. As a number of critics have noted, Victorian understandings of hunger were delimited by a series of competing ideologies.Footnote 8 In the light of Malthusian discourse, hunger could be understood as an inevitable part of human existence, a natural phenomenon which provided a necessary check on burgeoning populations by disciplining or excising the indolent and the thriftless. Alternatively, it could be read (as it had been for many centuries) as the instrument of divine providence, a heavenly-ordained punishment for human sin. These explanatory models were to become particularly significant during the years of the Irish Famine when they were adopted by a number of English commentators, including Charles Trevelyan, Assistant Secretary to the Treasury and chief administrator of Famine relief. Fusing the language of Christian providentialism with that of political economy, Trevelyan famously wrote in his 1848 assessment of the crisis, “posterity will trace up to [the] famine the commencement of a salutary revolution in the habits of a nation long singularly unfortunate, and will acknowledge that on this, as on many other occasions, Supreme Wisdom has educed permanent good out of transient evil” (1).

Opposed to this kind of ideological position was the interpretation of hunger as a social problem demanding a compassionate response, a construal which had its roots in eighteenth-century humanitarianism. Thomas W. Laqueur suggests that new ways of speaking about “the pains and deaths of ordinary people” emerged at this time in the form of “humanitarian narratives”: textual accounts of suffering in which details of somatic trauma and causality were particularised and emphasised in order to engender sympathy and forge a “common bond” between the narratives’ subjects and their addressees (177). Significantly, the keen sensibility and reforming instinct which structured these narratives later came to inform an assortment of nineteenth-century writings on poverty and hunger, ranging from parliamentary inquiries and coroners’ reports to industrial novels and articles in the periodical press.

The latter sphere was perhaps one of the most important in which narratives of hunger materialised in the 1840s. As Vernon notes, “the hungry became figures of humanitarian concern only when novel forms of news reporting connected people emotionally with [their] suffering” (17). He suggests that in the nineteenth century “new journalistic techniques and styles of reporting,” such as “personal stories about helpless starving children” or “the anguish of a mother unable to make ends meet,” helped to convey to readers “the human agonies of hunger” (18). Within these new forms of journalism, sentimentality performed a political function. June Howard, among others, has noted that sentiment can help to bridge the gap between reading self and afflicted other by simultaneously “locat[ing] us in our embodied and particular selves and tak[ing] us out of them,” an affinitive gesture which encourages ameliorative social action (77). Yet, as Laqueur acknowledges, humanitarian narratives can also produce antithetical responses, causing readers to detach themselves from the sufferings of others (202-03). In the epigraph to his essay, Laqueur quotes from Primo Levi's The Drowned and the Saved:

Compassion itself eludes logic. There is no proportion between the pity we feel and the extent of the pain by which pity is aroused. . . . Perhaps it is necessary that it can be so. If we had to and were able to suffer the sufferings of everyone, we could not live. (qtd. in Laqueur 176)

Detachment, then, may co-exist with sympathy, functioning as a necessary psychical defence against the debilitating consequences of unrestrained affect. In this light, it is notable that the emotive content of the representations of hunger discussed below is often countered by an array of subtle (perhaps even unconscious) “distancing” strategies; poems and pictures dating from the 1840s appear to vacillate uncertainly between ideological positions, shifting from dispassionate providentialism to humanitarian fellow-feeling and back again. In the following sections of this essay, I want to explore the implications and effects of this indeterminacy in image and verse.

The Politics of Sentiment: Hunger and the English Labouring Classes

For much of the 1840s (even, significantly, following the onset of the Irish Famine in 1845), middle-class illustrated periodicals appear to have been concerned chiefly with the hunger of the impoverished English lower classes. The early numbers of Punch, in particular, reveal an interest in the plight of this demographic. The opening article of the first issue, published in July 1841, made clear to readers that although Punch's title “may have misled you into a belief that we have no other intention than the amusement of a thoughtless crowd . . . we have a higher object” (“The Moral of Punch” 1). A key political target was the contentious Corn Laws, legislation which Punch linked explicitly to the problem of hunger: an 1842 full-page cartoon by A. S. Henning depicted a gaunt Britannia and famished lion protesting against Peel's sliding scale of import tariffs on grain, while an 1846 full-cut by John Leech anticipated the future benefits of free trade by imagining the British lion post-Repeal as pot-bellied and replete with beer and bread (Henning 89; Leech, “British Lion” 69). These cartoons typify the reformist politics of Punch's early numbers, but, dealing in symbols and abstractions, they work primarily to satirise political figures, institutions and policies. In Punch's poetical offerings, however, a more sombre tone emerges, along with a clearer sense of compassion for the victims of hunger.

The long-established relationship between poetry and affect meant that this literary mode was regularly adopted within early-Victorian periodicals to draw attention to social inequalities and the sufferings of the poor. A series of poems published in Punch in 1842, carrying titles such as “Pauper's Corner,” “The Prayer of the People,” and “Lays of the Lean,” participated in this trend, utilising first-person voices or deliberately emotive language to engage readers’ sympathies and highlight the problem of working-class hunger.Footnote 9 Of variable quality, these poetic contributions tended to be ephemeral, but when Thomas Hood's “The Song of the Shirt” was published anonymously in Punch's 1843 Christmas number (bordered, somewhat incongruously, by a procession of comical grotesques), it enjoyed huge popular success: the poem was eagerly reprinted by newspapers from across the political spectrum, used for propaganda purposes by textile industry reformers, and even set to music and performed on stage.Footnote 10 Inspired by reports of the wretched existence of England's seamstresses, “The Song of the Shirt” contrasts the steadily growing material output of an unnamed woman's sweated labour (“Stitch! Stitch! Stitch! / . . . Seam, and gusset, and band, /Band, and gusset, and seam”) with the rapid attenuation of her own physical form, which is revealed in her musings:

From its Gothic rendering of the seamstress's wasted form to the apostrophic appeal of the final two lines, this stanza petitions the emotional senses in a manner analogous to that found in eighteenth-century sentimental poetry. Yet, as Jason R. Rudy points out in his study of Victorian poetics, Hood's “Song” also draws on contemporary influences; in its stylistic features, and particularly its endowment of “a solitary voice with the weight of the collective,” the poem can be seen to borrow from the “working-class, and specifically Chartist, poetry of [its] time” (73).

A comparable exploitation of the rhythms and rhetoric of working-class poetry can be identified in a number of the verses printed by Punch in the 1840s. For instance, with its simple “abab” rhyme-scheme, alternating lines of iambic tetrameter and trimeter, direct form of address, and overtly political stance, “The Pauper's Song,” published in January 1845, takes inspiration from the “oral tradition of hymns, airs, and broadsides” that Anne Janowitz suggests also influenced early, anonymous Chartist ballads (135). The target of Punch's attack in “The Pauper's Song” is the reviled New Poor Law; the “famish'd,” “ragged” speaker argues that gaol is a more desirable option than the workhouse, because, although both institutions are forms of “prison,” he will at least receive sufficient fare to satiate his hunger in the former: “The Convict eats as good a meal, /But gets a little more” than the pauper, he suggests (Leigh 38). The desperate hunger alluded to in the poem is confirmed in the wood-cut illustration alongside it: a haggard-looking man leans against his stick, his torn and crumpled clothing hanging loosely from his emaciated frame (Figure 16). Even the thorny branches surrounding his figure are bare and barren, emphasising the poem's themes of poverty and dearth.

Figure 16. “The Pauper's Song.” Engraving from Punch 8 (1845): 38. Courtesy of Cardiff University Library: Special Collections and Archives.

Yet, in spite of its evident sympathy for the plight of the hungry, Punch's poetic and visual discourse here is far from radical. “The Pauper's Song” seems to appeal to a specifically middle-class concern: namely, the fear that an overly punitive system of poor relief might precipitate working-class criminality. This anxiety manifested itself repeatedly in early Victorian culture. It was suggested that several inmates of the notorious Andover Union, where starving paupers tried to appease their hunger by sucking marrow from animal bones being ground for fertiliser, committed theft in order to effect their removal from the workhouse to the relative comfort of gaol.Footnote 11 Later, an article on workhouses in Household Words expressed the widespread fear that “we have come to this absurd, this dangerous, this monstrous pass, that the dishonest felon is, in respect of cleanliness, order, diet, and accommodation, better provided for, and taken care of, than the honest pauper” (Dickens 205). The call for reform implicit in Punch's “Pauper's Song” emanates, then, not only from sympathetic concern but also from a fairly conservative desire to maintain social order. In this light, it is significant that the accompanying illustration of pauperisation is enclosed by a neat border; the insidious social problem broached in the poem is restricted and contained within its visual correlate. It is also significant that the pictured pauper averts his gaze from the implied spectator, shielding his face with his hands; the image is structured in such a way as to elicit pity while simultaneously enabling Punch's middle-class readership to avoid a direct, and potentially distressing, confrontation with working-class hunger.

Another subtle strategy of mollification can be identified in the poem “Ye Peasantry of England,” which was published in Punch in January 1846 in response to the Duke of Norfolk's suggestion that, in times of scarcity, agricultural workers might sustain themselves on a diet of hot water flavoured with curry powder.Footnote 12 Perhaps unsurprisingly, Punch's rejoinder to this ludicrous proposal was a piece of biting satirical verse which, like the “The Pauper's Song,” mimicked a poetic style commonly associated with plebeian protest. The poem's scornful refrain, “when hunger rages fierce and strong/To your curry powder go,” echoes the language of dissent that had characterised earlier nineteenth-century agrarian risings (“Ye Peasantry” 9). The archaic diction used in the poem's opening address, meanwhile, hints at an even longer tradition of popular rural protest – a tradition which, the poem insinuates, may soon be revivified. The ironic inflection in the lines

points to the possibility of an alternative outcome, where starving labourers, rising like Shelley's famous “lions after slumber,” abandon their places and do roar out for more (“Ye Peasantry” 9; Shelley 1175) . The threat of such violent revolt is tempered, though, by the poem's sentimental and idealised conception of England's peasantry. The nation's “hardy labourers” are also “hungry fathers,” struggling to provide for their young, the poem reminds us in a gesture designed to emphasise the fundamental decency and benignancy of the working poor (9). Corresponding allusions to the middle-class values of hard-work and family can be identified throughout Punch's verses on rural poverty: “The Ploughman's Petition” (1847), for instance, ventriloquises the voice of a “poor agricultural labouring man” who is both industrious (“I work well for my living”) and responsible for nurturing a family (“Recollect that a wife and young children have I”) (117). In the collective imaginings of Punch's urbane contributors, the “peasantry of England” is reassuringly romanticised as assiduous, upstanding and innately honourable.

Peter W. Sinnema detects similar sorts of “placating . . . strategies” at work in the ILN's investigations into English agrarian poverty in the 1840s (102). Laurel Brake and Marysa Demoor suggest that the ILN was “the title that first successfully yoked news and pictures in a sustainable and enduring publication in Britain” (2). The interplay between text and image in the periodical was by no means uncomplicated, however. Sinnema describes an 1846 double-page, illustrated feature on “The Peasantry of Dorsetshire” as a “complex and conflicting verbal-visual collaboration” (100). Inspired by a series of letters to the Times regarding the sufferings of Dorset's labouring population, the piece confirms the prevalence of hunger in the area. “It is, perhaps, worthy of remark that dishes, plates, and other articles of crockery, seem almost unknown,” the paper's correspondent writes, adding, “there is, however, the less need for them, as grist bread forms the principal, and I believe only kind of food which falls to the labourer's lot.” “Want, famine, and misery” are described as endemic, while, overall, the county's peasants are characterised as “hungry, emaciated and squalid” (“The Peasantry of Dorsetshire” 156). Intriguingly, though, these textual claims are not reflected in the nearby illustration of a group of healthy-looking, neatly-dressed agricultural labourers (Figure 17). As Sinnema points out, this image is “striking for its benign composition” and picturesque depiction of rural England (101). Its rustic figures seem to be unmarked physically by the ravages of hunger, appearing instead as plump and content. They may differ (in terms of class, dress, and lifestyle) from the ILN's typically urban readers but, importantly, their difference is entirely non-threatening. Indeed, Sinnema suggests, these peasants may “be embraced as a vital link with a common past”; in their “bucolic, earthy visages, English history and the proud legacy of the yeomanry can be read,” and this pictorial nostalgia helps to neutralise the language of hunger and suffering which saturates the accompanying article (101).

Figure 17. “Dorsetshire Peasantry.” Engraving from the Illustrated London News, 5 Sept. 1846: 157. Courtesy of Cardiff University Library: Special Collections and Archives.

The discordance between text and image here highlights the conflict between the ILN's desire to commentate on pressing social issues – “to keep continually before the eye of the world a living and moving panorama of all its actions and influences” (“Our Address” 1) – and its need to show consideration for the sensibilities of its “real, faithful, and influential patrons, – the RESPECTABLE FAMILIES OF ENGLAND” (Preface iv). A similar dilemma faced its contemporaries. In its opening number, published in January 1847, the Lady's Newspaper revealed its determination to shield readers from distressing or offensive content, promising:

Our paper will become a sort of omnibus of information – a public vehicle of advancement, – of which all may avail themselves with comfort and with safety; for the conductor has the power, and will not fail to exercise the right, of excluding all that can be objectionable. (Dance 2)

Weighty disquisitions on working-class hunger were largely absent, then, from the Lady's Newspaper; where references to the topic did appear, they tended to be oblique, peripheral or comfortingly sugar-coated. A piece entitled “The Beggar Child – A Capriccio,” published in the paper's weekly poetry column in October 1847, represents a case in point. The ragged child described in the poem functions as an object of amusement for the implicitly middle-class speaker, who renders the child's hunger as an essential part of his appeal. The poem's first stanza celebrates the boy's “wild” appearance, whimsically detailing the way in which his “once . . . bottle-green” trousers now “flap round his legs so lean” (Z. 409). In the second stanza, the beggar child's hunger is further subsumed under his quirkiness:

This ambivalent paean makes light of the child's physical condition, instead lauding his capacity for self-sufficiency. He is painted as a colourful, enterprising “area-sneak,” a street-urchin in the resourceful and comical “Artful Dodger” mould. Notably, his reconnaissance activities are rewarded with the prospect of a juicy beefsteak on which to sate his hunger, and this vision of plenitude helps to negate the troubling spectre of juvenile malnourishment which might otherwise haunt the work.

The poem's final stanza completes the idealisation of the beggar boy's existence with its entreaty

The conflation of itinerant lifestyle and self-determining liberty here fits with Celeste Langan's notion of “Romantic vagrancy,” a representational practice in which “the vagrant's mobility and expressivity are abstracted from their determining social conditions” and the ability “‘to come and go’ . . . becomes, in itself, the pure form of freedom” (17, 20). Of course, the alternative to this unfettered existence would be incarceration in the prison-esque workhouse bemoaned by the speaker of Punch's “Pauper's Song.” “The Beggar Child” lauds free-will and autonomy over the restrictions and confinements of parochial relief. Nevertheless, the poem's Rousseauvian investment in “freedom” – a condition which confers on the beggar boy an almost transcendental status – remains problematic, as it threatens to obscure, or even negate, material concerns about his hungry body.

As the examples discussed so far reveal, middle-class illustrated periodicals of the 1840s developed a number of textual and visual strategies – including sentiment, idealisation and nostalgia – to help distance their readers from potentially painful representations of English working-class hunger. This task would prove more difficult, however, when it came to representing the horrors of the Irish Famine, a calamity which began with the emergence of the blight phytophthora infestans in the potato crop in 1845 and resulted, by the end of the decade, in death, destitution and diaspora on an unimaginable scale.

Gothic Tropes and “Pictorial Facts”: Figuring the Irish Famine

Representations of the Irish Famine were impeded not only by the usual reluctance to expose middle-class readers to excessively harrowing accounts of starvation but also by an implicit awareness of the inadequacies of representation itself. “To describe properly the state of things . . . is a vain attempt,” wrote William Bennett in 1847; “It is impossible, – it is inconceivable” (132). The severity and extent of the malnourishment witnessed in Ireland in the 1840s far exceeded that experienced in England during the same period. Daniel Donovan, a doctor working in Skibbereen at the height of the Famine, sought to distinguish the “famine cachexia, or lingering starvation” he observed in his Irish patients from the cases of short-term or acute starvation more usually seen in working-class communities during times of food shortage. In a letter to fellow physician Robert Fowler, he wrote, “The cases with which I have been most familiar [in Ireland] were ones of lingering starvation, the supply of food having been insufficient for months. . . . In such cases, as was naturally to be expected, there was a gradual absorption of fat, with atrophy, and attenuation of the intestines” (qtd. in Fowler 151). Famine cachexia caused the starving body to become autophagous – to cannibalise itself. The extreme character of this type of starvation helps to explain why “the constant refrain of those who observed the famine [was], ‘It cannot be described’” (Marcus 10).

David Lloyd categorises such abbreviated accounts of events in Ireland as examples of the “indigent sublime,” which, he suggests, is “linked to . . . the much-theorized unrepresentability of the traumatic event, being registered as a shock suffered by observers who do not themselves undergo the perils of starvation” (156). Paradoxically, though, the unrepresentability of the Famine did not curb attempts to depict Irish hunger in the illustrated press. As Lloyd acknowledges, “Though perhaps the most frequent observation on the Famine is that its horrors defy description, that its ‘fearful realities’ cannot be represented, there is, nonetheless, an abundance, a surplus of representations of it” (161). What is most interesting about these representations is their circuity and reflexiveness. Chris Morash argues that

even before the Famine was acknowledged as a complete event, it was in the process of being textually encoded in a limited number of clearly defined images. Indeed, for an event which we customarily think of as being vast, the archive of images in which it is represented is relatively small and circumscribed. (“Literature, Memory, Atrocity” 113)

A pattern of specific discursive formations emerged in responses to the Famine and one of the most common of these, Morash suggests, was the representation of hungry victims as “stalking skeletons,” or the living dead (Writing 5). Interestingly, this trope can be identified in a number of the poetical responses to Irish hunger that appeared in the ILN. A poem depicting a funeral at Skibbereen, published in January 1847, makes a clear connection between the “shroudless dead” body that is to be buried and the “gaunt procession” that follows it, stalked by the “vulture Famine”:

A month later, the ILN published another poem bewailing the fate of an “uncoffin'd, unshrouded . . . corpse” and, again, suggested that hunger had skeletonised the victim's body prior to expiration: “No disease o'er this Victim could mastery claim, /‘Twas Famine alone mark'd his skeleton frame!” (T –.100).

In both of these cases, Gothic imagery conveys something of the ghastliness of the Famine to the ILN's readers; however, the very excessiveness of this language, rooted in literary tradition, risks rendering the horrors it speaks of problematically unreal. As Leslie Williams notes,

Images, verbal or visual, of intense distress and suffering, might excite human empathy. They may, however, simultaneously raise barriers against it. . . . For many people, there is a point at which the sufferer moves from the category of a human being to that of a grotesque. (Daniel O'Connell 349)

The figure of the “stalking skeleton” is one that threatens to breach this conceptual threshold and, consequently, many middle-class periodicals from the 1840s eschewed poems dealing explicitly with the gruesome experience of starvation. The delicately circumspect Lady's Newspaper, for instance, shunned all but the most euphemistic allusions to Irish hunger in its poetry column. “A Lament for Erin,” published at the height of the Famine in January 1847, is one of the periodical's rare offerings on the subject; notably, however, the poem carefully avoids making direct reference to events in Ireland, instead taking refuge in symbol and metaphor:

Although very different from the humorous verse and love poetry typically found in the Lady's Newspaper, “A Lament for Erin” has, nonetheless, been carefully shaped to meet the expectations of its female, middle-class audience. The poem's sentimental tone and romanticised personification of Ireland as a mourning mother encourage sympathy for a passive and politically benign version of Irish suffering – a version that obligingly veils the grim realities of death by starvation.

Pictorial representations of Irish hunger, by contrast, often made claims to verisimilitude. There seems to have been an ongoing desire to enable middle-class readers to visualise the Famine accurately, and this prompted editors periodically to dispatch their own artists to Ireland to produce “authentic” images of the nation's distress. In 1846, the Pictorial Times announced that it had sent a “Pictorial Commissioner” to Derrynane in County Kerry in order to assess the true “Condition of the People of Ireland.” “That justice may be done to Ireland – Ireland must be known as she really is,” the periodical proclaimed, adding, “Let us make an offering in her behalf of PICTORIAL FACTS” (“Pictorial Times Commissioner” 51).Footnote 13 The direct equation of visual information with fact, here, was reiterated throughout the subsequent article, which ran over a number of weeks: readers were repeatedly assured that “the sketches which illustrate our statements, are faithful, unexaggerated representations, drawn in every case on the spot” (“Condition of the People” 62). Actually, these images were far from spontaneous in conception; accompanying captions reveal that the scenes and subjects depicted by the Pictorial Times’ artist were not arbitrarily chosen but pre-determined, selected to fit with specific quotations extracted from existing accounts of Irish poverty (particularly those produced in 1845 by Times reporters Thomas Campbell Foster and William Howard Russell).Footnote 14 The Pictorial Times’ vision of Derrynane did not simply mirror an unmediated, external reality; it built on and reaffirmed an extant body of knowledge and, in doing so, helped to ossify English ideas about Ireland.

Occasionally, the Pictorial Times did acknowledge the particularity and partiality of its cultural gaze. In the first of its articles on the condition of Ireland, it pledged to examine the country's state “with English eyes, with a concern primarily to enlighten English minds, and to excite the compassion of English hearts” (“Condition of the People” 53). Given this focus, it is perhaps unsurprising to find that the engravings featured in the series tended to illustrate those aspects of Irish existence conventionally highlighted in the English press as examples of the nation's alterity: the poor condition of the housing, the prevalence of dirt and squalor, the unsettling proximity of human and animal living-quarters, and the ragged appearance of the people. Less obvious in the Pictorial Times’ illustrations is the impact of hunger on the Irish tenantry: although Irishmen and women are usually shown wearing shabby clothing or, in some cases, rags, from which their poverty may be inferred, their facial features and bodily proportions are not discernibly different from those of other figures depicted in the periodical. For instance, Tom Sullivan, a tenant on the O'Connell estate, is portrayed as a dishevelled but robust-looking man with ramrod-straight posture, even though the caption beneath his portrait indicates that he and the other members of his household are gripped by a debilitating hunger: “‘Had he plenty of potatoes?’ ‘Indeed he had not.’ ‘Of milk?’ Never; nor half a enough [sic]. Never had enough for either dinner or breakfast. All his children were as badly off as himself” (“Condition of the People” 60). Elsewhere, hunger is perceptible only through coded body language: an illustration of the inhabitants of J. Shar's cabin (Figure 18) shows an otherwise hearty-looking woman hugging her arms to herself in a gesture that Williams claims is still used in parts of rural Ireland to suggest hunger (Daniel O'Connell 213).Footnote 15

Figure 18. “Derrynane Beg – Interior of J. Shar's Cabin.” Engraving from the Pictorial Times, 24 Jan. 1846: 57. Courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

The problem of accurately but sensitively representing hungry bodies also troubled the ILN's illustrated articles on Ireland. In 1847, the periodical commissioned artist James Mahony to produce a series of sketches and written reports on Skibbereen and its surroundings, “with the object of ascertaining the accuracy of the frightful statements received from the West [of Ireland], and of placing them in unexaggerated fidelity before our readers” (100). The series, like the one published a year earlier in the Pictorial Times, ran over consecutive weeks and was intended to “direct public sympathy” toward Ireland's “suffering poor” (116); however, the scenes selected for illustration did not always serve this purpose unambiguously. Frequently, Mahony adopted a panoramic perspective in his images which worked to obfuscate the effects of the Famine. His vision of Ballydehob, for instance, takes in the surrounding landscape and, as a result, the pictured town, shown nestling in the middle-distance between a looming mountain range and the gently meandering Skibbereen Road, forms part of a pleasingly picturesque scene (Figure 19). Within this vista, there is little evidence of the “frightful” destitution mentioned in the accompanying article. Mahony's image does not focus on the extreme human suffering experienced in the locality, where, according to one witness, people were “dropping . . . daily” from starvation and fever (117). Indeed, like his representations of “Skull, from the Ballidchob” and “Skibbereen, from Clover-Hill” (101), Mahony's sketch of Ballydehob is only sparsely populated; the few, small figures included face away from the spectator, their distance and posture making it difficult to discern the visual signifiers of malnourishment in their persons.

Figure 19. James Mahony, “Ballydehob, from the Skibbereen Road.” Engraving from the Illustrated London News, 20 Feb. 1847: 117. Courtesy of Cardiff University Library: Special Collections and Archives.

A significant number of the ILN's illustrations of western Ireland in 1847 assumed this kind of remote view-point, visually tempering the effect of the periodical's detailed textual coverage of the Famine. Certain images, though, did undertake the task of representing the hungry close-up. Typically, these portraits concentrated on starving women and children, for, as Margaret Kelleher points out, the spectacle of such vulnerable victims functioned (then as now) as a ready cultural stimulus to pity (2). Mahony's depiction of a woman begging for money to bury the dead child she still nurses in her arms is, indeed, almost mawkish in its emotivity (Figure 20). Kelleher suggests that this illustration's affective power stems not only from its “strong evocations of the Madonna and Child” but also from its intimation of an inverted natural order: “when the maternal body . . . becomes the place of death, a primordial breakdown has occurred” (23).

Figure 20. James Mahony, “Woman Begging at Clonakilty.” Engraving from the Illustrated London News, 13 Feb. 1847: 100. Courtesy of Cardiff University Library: Special Collections and Archives.

Along with grieving mothers, orphaned children, forced to fend for themselves, were a recurrent and harrowing feature of Famine imagery. A week after the ILN printed the picture of the bereaved “Woman Begging at Clonakilty,” an engraving of two barefooted youngsters, scavenging for potatoes in a barren field, appeared in the periodical. Like its predecessor, “Boy and Girl at Cahera” (Figure 21) is notable for its pathetic appeal; however, the image's poignancy is marked by a strange ambivalence. Margaret Crawford acknowledges that the children's pinched features and thin, spiky hair are clear signifiers of starvation, but argues that the limbs of both “appear sturdy, contrary to what one would expect in prolonged famine conditions” (81). Obviously, it would be naive to demand photorealist exactness from nineteenth-century engravings: wood-cut illustrations in early-Victorian periodicals were constrained by the inherent limitations of the medium and contemporary modes of production.Footnote 16 Nevertheless, given the general emphasis on fidelity to reality in middle-class illustrated periodicals such as the ILN, it seems anomalous that so many Famine victims should have been pictured with non-attenuated physiques.

Figure 21. James Mahony, “Boy and Girl at Cahera.” Engraving from the Illustrated London News, 20 Feb. 1847: 116. Courtesy of Cardiff University Library: Special Collections and Archives.

Crawford suggests that a possible explanation for this phenomenon lies in the psychology of perception: “what an artist perceives at any given time is conditioned by experience and purpose rather than by his/her mental mirror of the scene” (88). The extreme emaciation witnessed during the Famine often exceeded the frame of reference of those sent to record it and thus “many artists working in the 1840s . . . failed to capture the full horrors before them: consciously or unconsciously they filtered out some of the more shocking human features of famine,” focusing instead on a range of culturally familiar “symbols of hunger,” such as “gaunt and haggard countenances, and ragged clothing” (Crawford 88). The realism of Famine illustrations could also be affected by ideology. Images in middle-class periodicals tended to echo existing cultural ideas about Irish national identity, tacitly reinforcing stereotypes about the indolence, intransigence and barbarism of the people. Significantly, in the ILN's “Boy and Girl at Cahera,” the boy gazes directly at the implied reader in an almost belligerent fashion, while his female companion is subtly animalised in the act of turning the ground with her hands in search of something to eat. These Irish children are objects of pity, but they are also carefully “othered,” dissociated from the civilised gentility of the intended reader.

A similar ambivalence can be detected in a later ILN series on the “Condition of Ireland,” published in December 1849. By this point, the Famine had been in the news for four years and, interestingly, with the passage of time, the ILN's illustrations of Irish hunger seem to have grown bolder and, in certain cases, more extreme. Figures such as Bridget O'Donnel and her children (Figure 22) appear markedly more emaciated than the mothers and infants sketched by Mahony in 1847; their ragged clothes expose a greater expanse of flesh, making it easier for readers to perceive their wasted frames and to connect them with the “half-clad spectres” described in the associated article (“Condition of Ireland” 404). There is, indeed, something haunting about the image of O'Donnel; with her delicate facial features but androgynous body and weirdly elongated limbs, she monsters the Victorian feminine ideal, appearing closer to the “stalking skeletons” of the ILN's Famine poetry than the full-figured matriarch of middle-class ideology. Her distended outline is perhaps indicative of the artist's struggle to represent a figure so thin as to confound the idea of what is “human.” This struggle seems also to have affected the ILN's engraving of “Miss Kennedy Distributing Clothing at Kilrush” (Figure 23), which appeared on the same page as the image of O'Donnel. Disturbingly, one of the female recipients of Miss Kennedy's charity is illustrated, in the periodical's own words, “crouching like a monkey, and drawing around her the only rag she had left to conceal her nudity” (“Condition of Ireland” 405). The textual and iconographic animalisation of the destitute woman, here, serves to undermine her humanity to potentially damaging effect. As Lloyd points out, history has shown that “the victim's dehumanisation this side of death” helps to make his or her ultimate “extirpation thinkable and admissible” (156).

Figure 22. “Bridget O'Donnel and Children.” Engraving from the Illustrated London News, 22 Dec. 1849: 404. Courtesy of Cardiff University Library: Special Collections and Archives.

Figure 23. “Miss Kennedy Distributing Clothing at Kilrush.” Engraving from the Illustrated London News, 22 Dec. 1849: 404. Courtesy of Cardiff University Library: Special Collections and Archives.

Of course, it is important to recognise that the “othering” of starving Irish men and women in English illustrated periodicals was not necessarily a conscious or coherently conceived response to the horrors of the Famine; indeed, the process often co-existed with explicit and heartfelt expressions of compassion for the hungry. Whether wittingly produced or not, however, notions of otherness performed an important cultural function, subtly suggesting the difference and distance between the subjects of Victorian periodicals’ discourses on food scarcity and the middle-class consumers of those discourses. Maud Ellmann argues that “there is something about hunger, or more specifically about the spectacle of hunger, that deranges the distinction between self and other” (54). The conceptual partitions put in place by the ILN and its competitors worked to preserve the limits of this self/other divide and thus implicitly helped to safeguard English, middle-class identity.

Arranging Hunger on the Printed Page

When analysing the complex range of meanings produced by Victorian illustrations of hunger, it is important to pay attention not only to their visual content, but also to their distribution and organisation on the printed page. Patricia Anderson notes that

the medium for transmitting an image. . .can also be the agency by which that image's meaning is altered. Its position on the page, the caption, text, and name of the publication together provide a context for the picture, a context which directs the reader-viewer's attention toward a specific message which may, or may not, be literally depicted. (57–58)

Anderson's comments are particularly relevant to the illustrated poems from Punch discussed in this essay, as the situation and context of these pieces could modify the range of meanings and responses produced. The buffoonery enacted by the procession of comical grotesques bordering Hood's “Song of the Shirt,” for instance, sits uneasily with the gravity of the poem's themes and tone, potentially undermining the urgency of its political message. A similar incongruity seems to trouble the positioning of “The Pauper's Song” and its accompanying image of destitution: in this case, poem and illustration are situated directly above a satirical article and cartoon lampooning Lord Brougham's recreational activities in the South of France. Owing to the typeface and spacing employed, however, it is “The Pauper's Song” to which the reader's eye is inevitably drawn. The poem's dominance is further enhanced by its links with the full-cut on the facing page, which depicts Prime Minister Robert Peel telling an impoverished labourer and his family, “I'm very sorry my good man, but I can do nothing for you” (Leech, “Agricultural Question” 39). Here, Punch's organisation of material suggests its commitment to social reform: the proximity of the two mutually-interested features encourages readers to make connections across pages, identifying in the pauper's wasted state the labourer's future fate and in Peel's reluctance to introduce measures that would antagonise his party the political forces underpinning social problems such as pauperisation.Footnote 17

Elsewhere, the physical layout of the printed page could work to moderate the traumatising effects associated with distressing textual or visual portrayals of hunger. The ILN (which prided itself on its high quality production values) proved particularly adept at this kind of structuring of multi-media information. Critics including Williams and Sinnema have demonstrated how the periodical's meticulously arranged special features worked to reassure readers by balancing letterpress and engravings to create an overall “sense of symmetry, order and control” (Williams, Daniel O'Connell 339). The resulting “compositional equilibrium” (Sinnema 44) can be identified in a number of the illustrated articles examined in this essay, such as the main double-page spread of the feature on “The Peasantry of Dorsetshire,” discussed above, where four illustrations of equal proportions are positioned symmetrically around a horizontal band of text. This neat, precise layout carefully frames the ILN's communications about working-class life for the benefit of its middle-class readers; the inherent harmony and regularity of its design cleverly counteracts disturbing references to poverty and disorder within the text.

The ILN's competitors in the middle-class market were, for the most part, unable to match the technical precision and quality of its layouts, but did not let this deter them from attempting to emulate its methods of organising materials on the page. An 1848 report on “The Special Commission and the Irish Peasantry” in the Lady's Newspaper, for example, threaded three columns of print around five symmetrically distributed wood-engravings, to striking effect (41). The co-ordination of images in this case can be seen to influence the range of meanings produced; significantly, the disquieting image of an Irish beggar-woman and her starving children on the bottom right-hand corner of the page is counterbalanced by a representation of two hearty-looking Irish peasant girls on the left.Footnote 18

Dissonances can emerge, then, from the semantic gaps between illustrations and by examining the structural relations between sets of images we can identify the ambivalent attitudes toward hunger, and the Irish Famine in particular, in circulation in Victorian Britain. The Pictorial Times regularly supplemented its commentary on the situation in Ireland with two, contrasting visual interpretations of events: a double-page 1846 report on “Irish Agitation and Destitution” asked readers to compare the “moral impatience” of the nationalist politicians illustrated on the verso with the submissiveness of the starving family depicted on the recto (120). A year later, in a feature on the “Famine in Ireland,” the periodical again invited readers to compare two, conflicting representations of the crisis: an engraving of three hostile-looking peasants, armed with bayonets, appeared above one showing a relief convoy under military escort, watched by a group of hungry onlookers (Figures 24 and 25). In the thin, horizontal strip of text separating the images, the Pictorial Times took pains to emphasise the contrast:

On the one hand, we behold the operation of the arrangements of a wise and humane Government for supplying a destitute and famine-stricken population with the means of existence. The wheels of the meal cart creak under the burden which is to relieve hundreds of human beings from the horrors of starvation. . . . Look on that picture – and on this. A band of lawless ruffians, who prefer the wages of crime to the fruits of honest industry – who would rather spill human blood to purchase a meal, than till the generous earth for the sake of its abundance; this band, armed with such weapons of offence as violence or robbery have placed within their reach, positively await the coming of the supplies. (281–82)

Figure 24. “Irish Armed Peasants Waiting for the Approach of a Meal Cart.” Engraving from the Pictorial Times, 30 Oct. 1847: 281. Courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

Figure 25. “Meal Cart, Under Military Escort, Proceeding to a Relief Station, Clonmel.” Engraving from the Pictorial Times, 30 Oct. 1847: 281. Courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

The dyadic approach employed here enables the Pictorial Times to bridge differing ideological perspectives on the Famine, extending its sympathy to deserving members of the Irish peasantry on the one hand, while condemning what was commonly perceived as nationalist ingratitude, idleness and aggression on the other. The visual foregrounding of the official relief effort in the second image would have appealed to the preconceptions of a large section of the periodical's middle-class readership: the self-congratulatory focus on English exertion and efficacy here not only adumbrates the acuteness of the Famine's effects but also chimes with Victorian stereotypes regarding Irish lassitude and dependency.

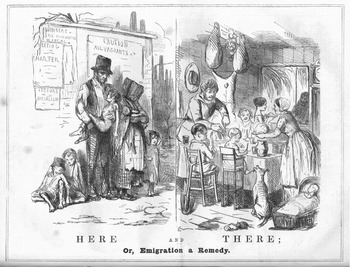

A well-known 1848 cartoon in Punch, likewise, used contrasting images to both commiserate with and tacitly censure the Irish. In “Here and There; or, Emigration a Remedy” (Figure 26), the destitute family located “here” is clearly depicted in line with the humanitarian narratives discussed earlier in this essay: a haggard father holds an emaciated child, faint with hunger, in his arms, while two further frail and shrunken children support each other on the ground (26). Should this family choose to emigrate, the opposite image suggests, its members’ lives will be suffused with plenty: “there,” a plump, happy group is shown sitting around a well-stocked dinner table, with a couple of hams hanging overhead for good measure. The sympathy implicit in the first image is muted in the second, which suggests that the “remedy” for Irish hunger is within the reach of the afflicted. The advocacy of emigration aligns the cartoon with the political economy espoused by commentators such as Harriet Martineau, who wrote that “a vast emigration” from Ireland would present the country with the opportunity “to begin afresh, with the advantage of modern knowledge and manageable numbers” (111). Ultimately, then, the conflicting ideologies located in Punch's cartoon, signified through its bifocal arrangement, permitted its middle-class readers to empathise with, but also absolve themselves of responsibility for, other people's hunger.

Figure 26. “Here and There; Or, Emigration a Remedy.” Engraving from Punch 15 (1848): 26. Courtesy of Cardiff University Library: Special Collections and Archives.

The Problem of Representation

As theorists of iconography have long argued, the selection and arrangement of images in illustrated texts is never ideologically neutral. The manner in which the images (and poems) discussed in this essay were distributed on the printed page would have had important cultural and material effects, helping to moderate public perceptions of the hungry and, potentially, influencing levels of enthusiasm for private philanthropy. As the London Journal noted in 1848, “English charity is large and bountiful, but it is eccentric in its course” (“Destitution in the Metropolis” 412). Where depictions of starvation stimulated feelings of habituation or distaste, their affective power was dramatically reduced.

Middle-class Victorians’ attitudes toward endemic hunger were influenced not only by recurrent representations of the Famine in Ireland but also by repeated portrayals of English working-class poverty in the periodical press. The extent of the suffering experienced in England and Ireland may have differed during the “Hungry Forties,” but the strategies and techniques used to represent it were remarkably similar. Via a series of pictorial and poetical representations, illustrated periodicals attempted to realise the chronic, and often life-threatening, hunger that beset the socially and economically vulnerable, without offending middle-class sensibilities or inducing the kind of ennui associated with over-familiarity. Typically, verse was used to humanise the victims of hunger and to stimulate sympathy; however, the frequent recourse to Gothic language in poetic offerings could also highlight the alterity of the hungry. Wood-cut engravings regularly promised to reproduce faithfully the sufferings of the English and Irish peasantry, but these images were constructed, selective and invariably shaped by ideological concerns.

Owing to the complex and often contradictory attitudes to hunger with which they were loaded, the poems and pictures discussed in this essay could elicit a range of possible responses. On the one hand, they could work to vivify the horrors of starvation for a middle-class readership unaccustomed to the paroxysms of want and possibly even incite members of this politically enfranchised class to demand progressive social reform. On the other hand, they could militate against this kind of activism by distancing or naturalising working-class hunger, positioning it as the unfortunate but inevitable fate of the indigent “other.” Such negativity was particularly evident in responses to the Irish Famine, as illustrations of this event were frequently coloured by assumptions about Irish character. In October 1847, the Pictorial Times concluded that the “gloomy picture” of Irish society painted in images such as its own engraving of “lawless ruffians,” waiting in ambush for a meal cart (Figure 24), “almost serve[d] to justify the penuriousness that would deny assistance to one-half of Ireland, on the ground of the crimes and indolence of the other half” (282). The periodical's ambivalence seems to have been shared by the wider public. Peter Gray notes that stereotypes of Irish barbarity and ingratitude played a role in the emergence of “compassion fatigue” in the autumn of 1847. Earlier that year, £171,533 had been raised in response to a letter from Queen Victoria appealing for contributions toward famine relief, but when a second letter was issued in October 1847 only £27,000 was donated (209–13). This perceptible shift in attitudes indicates the mutability of early-Victorian perspectives on hunger, while also pointing to the burgeoning power of the illustrated press.

It is important to recognise, however, that although representations of hunger in middle-class periodicals were influential they were not intentionally deceptive or insidious. What they reveal, collectively, is the impossibility of reproducing the experience of hunger neutrally, or in its exactitude, in textual and pictorial form. During the Victorian period, cultural understandings of hunger were negotiated (as they are today) through certain recognisable, reiterated motifs in which ideological meanings inhered. What these anxiously repeated poetical and iconographical depictions finally attest to is the idea that hunger's gnawing reality resists representation: its agonies are always-already lost to both contemporary and modern-day readers of Victorian illustrated periodicals, as the printed page inevitably supplants the attenuating bodies of English and Irish sufferers with an intricate web of visual and textual signifiers.