This article discusses how currency in Japan, still largely regionalized at the beginning of the seventeenth century, was unified under the Tokugawa Bakufu (shogunate), and examines special characteristics of both the processes behind the unification and the unification itself.

In recent years, many advances have been made, particularly in the field of Japanese medieval history, in topics such as regionality in the circulation of coins during the transition between the medieval and early modern periods, the background and influence of anti-shroffing edicts (erizeni-rei 撰銭令), the use of rice as a currency, and the spread of gold and silver as money. Behind this growing interest lie developments in the study of coins unearthed during archaeological investigations, whose reliability as historical evidence is backed by sound excavation methodology and detailed reports. Thus it is possible to study the history of currency for the relevant period in specific terms from both documents and material remains.

Studies on regionality are connected to some extent with studies of domain currencies by scholars such as Kobata Atsushi (1905–2001), Itō Tasaburō (1909–1984) and Enomoto Sōji (b. 1924).Footnote 1 Their work has paved the way for reassessing the significance of the early modern tri-metallic currency system and how it was achieved. The conventional view of the monetary history of this period is that it has unfolded in a number of stages according to the political vicissitudes of the shogunate: during the course of the seventeenth century, the use of gold and silver was established in conjunction with the foundation of Tokugawa rule, copper coinage was standardized somewhat later with the issue of the Kan'ei tsūhō 寛永通宝, and subsequently a three-currency system spread throughout the country. The growth of the three-currency system was indeed a long-term process, but to view the issue of currency at the beginning of the period entirely as a government monopoly and an exercise of compelling force is less convincing. How was early modern currency unification achieved, and how was it different from unification in later times? To answer these questions, I would like to reposition early modern currency more comprehensively within the political and economic climate of the times.

The phenomenon of currency unification throughout the Japanese archipelago represented a breakaway from the contemporary East Asian currency sphere, composed mainly of silver ingots used by weight, and of Chinese Song copper coins, originals as well as later imitations.Footnote 2 To put it another way, it can be considered the currency dimension of the seclusion (sakoku 鎖国) policy, that is, an aspect of national independence. Thus we cannot exclude wider global factors when describing domestic currency unification, and this viewpoint will also form one of my main considerations in this article.

We will here emphasize copper coinage, which has been less studied, and by comparing it to gold and silver currency, I will attempt to give a more complex and dynamic view of currency unification in early modern Japan.

BAKUFU CURRENCY AND GOLD AND SILVER IN THE DOMAINS

In 1600, Tokugawa Ieyasu defeated his enemies at Sekigahara and assumed political control over the whole country. The following year he set up a silver mint monopoly in Fushimi, near Kyoto, authorizing the minting of oval-shaped silver ingots called the (Keichō) chōgin 丁銀 and smaller coin-shaped silver ingots called mameita-gin 豆板銀.Footnote 3 The same year gold koban 小判 and ichibuban 一分判 coins were issued through the gold mint monopoly in Edo, under the directorship of Gotō Shōzaburō Mitsutsugu 後藤庄三郎光次 (1571–1625). This was essentially the first time officially minted currency had been issued, and it came from gold and silver mints authorized by the government. The gold and silver mints not only cast gold coins and silver ingots for the government, using bullion sent as tax payments to the Bakufu (the Tokugawa shogunate), but were also guaranteed, in lieu of a service fee or a commission, a monopoly to buy both high-quality cupelled silver produced by the ash-blowing method called haifuki 灰吹 and refined gold (sujikin 筋金) direct from the mines, which circulated in the market as money-by-weight, and to cast this into official gold and silver currency for sale at a profit. From the middle of the seventeenth century, however, production fell at gold and silver mines throughout the country, and so did the volume of bullion appearing on the market. The two mints were then forced to rely on tax bullion from the major mines under direct government supervision, but they remained authorized to mint gold and silver, so that by the end of the seventeenth century domestic gold and silver currency was virtually standardized throughout the country, based on the output from government mints.Footnote 4

These currency provisions were enforced by law. In 1609, a letter dated Keichō 14.5.3 co-signed by the superintendent of mines Ōkubo Nagayasu 大久保長安 (1545–1613) and other Sunpu overseers was sent to daimyo and daikan 代官 (local magistrates) with gold and silver mines in their territory, banning them from smelting gold and cupelling silver. This was intended to prevent both the illegal minting of gold and silver currency under the pretence of refining ore and the illegal private trading of bullion earmarked for government use, as well as to ensure that the official gold and silver mints maintained a monopoly on the bullion. The illegal minting of gold and silver currency had been made a crime punishable by death from early in the period, and this was extended in 1643 to the “private minting” (shichū 私鋳) or counterfeiting of copper coins, following the issue of the new Kan'ei tsūhō in 1636. Nationwide edicts were promulgated to this effect, and the penalty took the form of crucifixion, the most extreme of all the death sentences, which signified that forgery had come to be considered a crime on a par with being a Christian. The fiat of the Tokugawa government on this matter extended into all of the domains.

During this same time, silver was the single most important item of the export trade from Japan. In the first decade of the seventeenth century, Tokugawa Ieyasu attempted to ban the export of high-quality haifuki (cupelled) silver and limit export silver to the lower-quality chōgin.Footnote 5 Subsequently a new silver mint was established in Nagasaki around 1616 to cast currency for trade and so regulate silver exports there.Footnote 6 The Keichō chōgin though, with a fineness of only 80 percent, was of a lower quality than the trade silver of East Asia at that time, and so pure haifuki silver was preferred for export. As a result, however much foreign merchants were compelled to accept the chōgin, they would in fact exchange it within Japan for cupelled silver, which they then exported.Footnote 7 Japanese traders too, up until 1635, during the time they were still permitted to travel and trade abroad under the vermilion-seal (shuinsen 朱印船) system, would refine the chōgin abroad at the point of trade and use it there.Footnote 8 By controlling cupelled silver and limiting trade silver to the chōgin, the Tokugawa government apparently aimed to close the door on daimyo freely purveying cupelled silver and so strengthen its own trade monopoly. All the same, in the seventeenth century domain lords were developing gold and silver mines on their land and refining the ore into ingots of a set level of purity. These they hallmarked (gokuin 極印) with seal impressions and other designs as a guarantee of quality and used as currencies within their own domains. There was also haifuki silver with no hallmark. Documentary and archaeological research has provided us with a detailed knowledge of the existence of such domain currencies, and domain silver in particular. In line with the aims of this article, I would now like to position these domain currencies in relation to the Bakufu and the silver mints.

Enomoto Sōji has summarized types of silver according to domain, and discussed silver usage taking Tsugaru and Kaga as examples, based on the following three documents connected with the Kyoto silver mint: “Memorandum concerning the minting of chōgin from cupelled silvers produced in various domains” (Haifuki-zukai no kuniguni yori idemōshi sōrō haifuki chōgin ni fukitate mōsu oboe 灰吹遣之国々より出申候灰吹丁銀に吹立申覚), submitted to the Bakufu by a mint official, Kano Shichirōemon 狩野七郎右衛門 in 1668; “Graded list of cupelled silvers from various domains” (Shokoku haifuki kurai zuke 諸国灰吹位付, Document 2) dating from the Genroku (1688–1704) or Kyōhō (1716–1736) era; and “List of cupelled silvers from various domains” (Shokoku haifukigin yose 諸国灰吹銀寄, Document 3) of 1771.Footnote 9Haifuki silver from various mines was used for a small number of domain currencies. These currencies were used not simply as money within the domain; they were also used to obtain government specie, either by being sent to Edo or exchanged within the domain, and could even be circulated outside the domain (for example, the “adopted silver ingots” torikomigin 取込銀 of Kaga). However, they were discontinued in the latter half of the seventeenth century, as the amount of silver being mined decreased and as they were exchanged for, and supplanted by, the official Bakufu currencies (silver chōgin, copper Kan'ei tsūhō).

The three documents quoted by Enomoto derived from the Kyoto mint itself, and we should note that each type of silver was valued in terms of the ore used to mint the chōgin. For example, the 1668 document, referring to silver from the province of Kaga, reports:

Item. Eight monme 匁Footnote 10 of copper is added to one hundred monme of haifuki wrapped in red-dyed paper, making a chōgin of 108 monme. This wrapped haifuki is said to have come from the north country, which has been re-smelted into wrapped haifuki for “expense silver” (tsukaigin 遣銀).Footnote 11

This “red-paper wrapped haifuki” was the “expense money” (tsukaigin) of the ruling Maeda family of Kaga, in other words, Kaga domain currency. The domain purchased cupelled silver from mines in the north and recast it according to a set level of fineness. Later, at the silver mint, eight monme of copper were added to it to make chōgin. Apparently silver produced in the northern provinces was of the highest quality, then below that came haifuki wrapped in red paper, and lowest of all the chōgin issued by the government. Kano's document mentions that copper was added in this way to all domain silver, which strongly suggests the mints regarded domain silver as bullion. The other two documents evaluated domain silver, not in terms of how much copper should be added, but by its relative value against Keichō chōgin silver. For example, a 10 percent premium (ichiwari-iri 一割入) was required to convert Keichō chōgin silver into “high-grade (cupelled) silver” (jōgin 上銀). One-for-one exchange was called tsurikae 釣替; anything above this was shown by the character iri 入 (“plus”) and below it by the character hiki 引 (“minus”). Documents 2 and 3 record silver down to a considerably lower quality than did Kano's report, and the number of varieties increases as the years pass. The lowest value appears in the “Graded list of cupelled silvers from various domains” as 33 percent biki 三割三歩引 (minus premium) at the locale of Sadamaru zaisho in Takada domain in Echigo against the chōgin, and in the “List of cupelled silvers from various domains” as six to seven waribiki at Kujira 1-chōme in Inaba. Numerous remintings of silver between the issue of the Keichō chōgin and the Genbun-era (1736–1741) chōgin resulted in the lowering of the quality of the silver in circulation, and so by the second half of the eighteenth century, the mints were apparently buying up even lower grade silver.

This demonstrates that domain silver was entirely positioned in relation to the chōgin, so that bullion was valued, not on an objective grade, but in terms of a numerical value in relation to Keichō chōgin silver. This was a source of profit for the silver mints as they assessed their minting fees. The balance of power between the shogunate and the domains too is reflected in the chōgin-centred currency. Whereas the chōgin was a nationwide currency minted under the authority of government-licensed mints, domain silver was not much more than money circulating within one domain, and, however high its quality, outside the domain it was nothing more than bullion. The irreversible nature of the relationship between domain silver and the chōgin, where the former was used to mint the latter, worked towards achieving the unification of silver currency, which was in high demand in the central urban areas. We should note, though, that the silver mints did not actively purchase silver that was of such a low grade that they could not make a profit from it. When we think in terms of currency unification, profit demarcated the limits of production as far as the silver mints were concerned, in so far as they were independent businesses undertaking currency issue. Thus, logically, we cannot deny the possibility that debased silver ingots (akugin 悪銀) remained in circulation within small areas, and in all probability comprised the lowest grade of silver mentioned in the “Graded list of cupelled silvers from various domains” and the “List of cupelled silvers from various domains” above.

COPPER CURRENCY UNIFICATION: THE KYŌSEN (BITASEN)

In 1608 (Keichō 13), an ordinance issued by the Bakufu and co-signed by the officials Ina Tadatsugu 伊奈忠次 (1550–1610), Andō Shigenobu 安藤重信 (1558–1622) and Doi Toshikatsu 土井利勝 (1573–1644) was fixed to public noticeboards in Edo, banning the use of the Eirakusen 永楽銭 (the Yongle tongbao 永樂通寶, a Ming copper coin). The following year, an official parity was announced between gold, silver and copper, the ratios being one gold ryō 両 = fifty silver monme = one kanmon 貫文Footnote 12 of Eirakusen = four kanmon of copper kyōsen 京銭 (“money from the capital region”). The Eirakusen, which had been standard currency in the eastern provinces since the late sixteenth century and enjoyed a favourable parity against gold coin there, remained a money of account, despite the ban on its physical circulation. The standard coin taking its place was the coin favoured in Kansai, the bitasen 鐚銭, otherwise known as kyōsen, with a face value of one mon 文. These two ordinances can be considered a type of anti-shroffing edict (erizenirei 撰銭令) applying to the shogunal lands in Kanto. Since copper was the main means of payment along transportation routes, it was in the interest of the Bakufu, racing to organize the post stations along the highways between the old capital region and Edo, to abolish circulation of the region-specific Eirakusen. It thus was already looking to unify copper currency through the kyōsen, by guaranteeing its stable circulation at an official fixed rate. The Bakufu subsequently issued anti-shroffing edicts on occasions such as the Shogun's official visit to Kyoto, and ordered over and over again that low-quality coins be removed from circulation, and that the kyōsen be circulated at the official rate. As the standard currency specified by the Bakufu, the kyōsen could be used throughout all the domains. We can call this stage, preceding the introduction of the Kan'ei tsūhō in 1636, the period of copper currency unification through the kyōsen.Footnote 13

Though the kyōsen had been made the official standard by the government, many daimyo continued to mint and circulate their own copper coinage within their domains or over a restricted area. We know that this occurred in Akita, Mito, Nagato, Buzen Kokura and Satsuma,Footnote 14 where local coins had names such as the Akita namisen 並銭, Nagato kunisen 国銭, Hagisen 萩銭, Kawachisen 河内銭, and Satsuma kajikisen 加治木銭 (the Chinese Hongwu tongbao 洪武通寶 coin). In the poetry collection Kefukigusa 毛吹草, published around 1637, we get a glimpse of what local currencies were circulating before the introduction of the Kan'ei tsūhō: there was the “zeni” 銭 (called the “new zeni” 新銭) of Hitachi, the “hariganezeni” 針金銭 of Dewa, the “zeni” (used by pilgrims to the Ise Shrines from around the country) of Nagato, and the “korosen” 洪武銭 (Chinese Hongwu coins) of Chikugo and Satsuma (both in Kyushu). More information about the Akita coins has come to light in recent years as a result of archaeological finds, since we can study the actual coins.

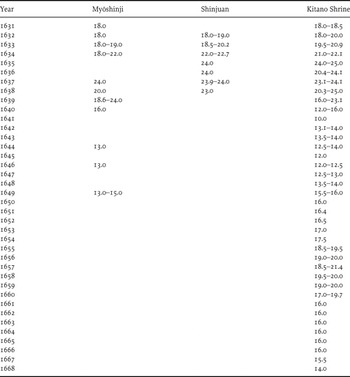

We know the parity of Akita coins against gold and silver in the early years of the Keichō era (1596–1615): between 1597 and 1601, one gold ryō was exchanged at between 68 and 95 kanmon of copper coin, while in 1600–1601, one monme of silver was worth between 2 kan 500 mon and 3 kan 300 mon of copper coin.Footnote 15 The conversion rate of one kanmon of copper coin was therefore between around 0.3 and 0.4 monme of silver. For comparison, let us look at the exchange rates of copper coins in Kyoto in the period 1598–1630 (Table 1). In 1600–1601, one kanmon of copper coin was worth between 6.5 and 7 monme of silver in Kyoto. The standard silver in Kyoto would have been the Keichō silver minted by the government from 1600, thus there is a strong possibility that Akita silver was of a higher quality. But even so, it was only worth a tenth or less of Kyoto silver. An entry dated Genna 3 (1617) 10.13 in the diary of Umezu Masakage 梅津政景 (1581–1633), an administrator of the silver mines in Akita domain, records the exchange rates against silver when changing namisen for kyōsen in 1615: “100 monme of silver = 418 kan 980 mon in namisen.” One kan of kyōsen was worth “20 monme of silver.” Since one kanme of namisen was worth around 0.238 monme of silver, the Akita namisen was therefore worth less than one eighty-third of the kyōsen. This exchange rate of kyōsen was much the same as it was at the Kyoto exchange in the same year.Footnote 16 As I will mention below, there is a possibility that this namisen was different in form from the Akita copper coin of the early part of the Keichō era, but at any rate, falls in the exchange rate with silver and the threefold rise of the copper coin market in Kyoto caused the exchange rate of the Akita namisen to fall extremely low.

Table 1. Zeni exchange, Kyoto, 1598–1630

Sources: For Myōshinji and Shinjuan, “Myōshinji nōgechō”, “Shinjuan nōgechō”, Daitokuji monjo (Kyōto Daigaku Kinsei Bukka Kenkyūkai ed. Reference Kyōto daigaku kinsei bukka kenkyūkai1962); Kitano Tenmangū shiryō, miyaji kiroku; Kitano Tenmangū shiryō, nengyōjichō; Chōmyōji monjo, Kyōto jūroku honzan kaigōyō shorui 4; Kyōto Reizen chō monjo 1.

Note: The numerical values are silver monme to one kanmon of copper coin.

Archaeological finds show that coins without lettering (mumonsen 無文銭) circulated in Akita domain. Moreover, a large number of thin, light-weight coins called wasen 輪銭 have been discovered.Footnote 17 We know that in general if copper coins were cast over and over again by casting the replica in the original mould, they would become lighter and thinner. It is very likely that coins minted in the early part of the Keichō era deteriorated into the namisen of the later years of that era, and we can see the result of this in the fact that the exchange rate of copper against silver fell. The term harigane zeni 針金銭 (“wire coins”) applied to the coins of Dewa domain seems to reflect this. It is likely that the Satake lords of Akita switched from the namisen to the kyōsen in 1615 due to the fact that debased coins both hindered the production of copper currency itself and eventually limited its circulation. In addition, the Eirakusen had already been circulating in Akita. Copper coins in Akita demonstrate that differentiation between coins was well advanced in the local circulation zone. Whether the namisen itself was actually abolished, though, or whether standard coins were simply exchanged for it, leaving it entrenched as the smallest unit of price calculation, needs further study.

What position did the kyōsen occupy when other small-denomination coinage circulated in a daimyo's domain? From the Genna era (1615–1624), the Hosokawa lords of Kokura domain in Buzen province circulated gold currency called Migitaban 右田判, wrapped and sealed by a gold merchant called Migita, and hallmarked silver ingots called Hirataban 平田判. From 1624 to 1628 they minted a “new [copper] coin” (shinsen 新銭) for circulation within the domain,Footnote 18 while stockpiling kyōsen for use outside the domain and to give to emissaries.Footnote 19 A letter from Hosokawa Tadaoki 細川忠興 (1563–1646), lord of Kokura, to his son Tadatoshi 忠利 (1586–1641), dated Kan'ei 9 (1632) 7.11 concerns the dismissal of a certain Katō of Kumamoto, but it also contains a passage expressing Tadaoki's anger regarding Tadatoshi's dealings with a shogunal envoy passing through the Hosokawa domain:

I was indeed exceedingly surprised that you had instructed the townsman in charge of the lodging at the post station to accept the kyōsen on the grounds that each province has a different currency, and told him that you would later buy back the money. You must not act in this way when shogunal envoys are passing through this province. I believe that expending concern over such a request might compromise your own position in the future.Footnote 20

Tadatoshi had ordered an innkeeper to accept the kyōsen that the envoy was carrying, without requiring him to exchange them first, and told him he would buy them back later. Tadaoki was worried that such excessive solicitude for the shogunal envoy did not befit his son's position. His words suggest that he considered it a daimyo's prerogative to have his own currency circulating on his domain. This episode can therefore be viewed as an example of the shifts that were occurring in the changing relationship between the Bakufu and the domains over the daimyo's right to issue currency. The kyōsen had been made, as we have seen, the standard currency nationwide, but its use was actually based on the political supremacy of the Bakufu vis-à-vis the daimyo rather than on outright legal enforcement. The above exchange between father and son reflects stages in the development of Bakufu authority, revealing to us differences in attitude towards it between Tadaoki, who had lived through the period when the Tokugawa house was simply first among equals, and Tadatoshi, living in the time of Tokugawa Iemitsu, the undisputed power-holder.

The stage of currency unification in the form of the kyōsen lasted from around 1608 to 1636, when the Kan'ei tsūhō, a one-mon copper coin, was issued. During this period, the kyōsen circulated throughout the country as a standard coin authorized by the government, though the use of domain copper coins and low-denomination haifuki silver was allowed locally. Currency – gold and silver as well as copper – was moving comparatively gently towards unification on the basis of the political ascendancy of the Bakufu, though independent currency zones belonging to various domain lords were recognized.

THE EXPORT OF COPPER COINS AND ITS CESSATION

It is known that the Dutch exported copper coins cast in Japan early in the seventeenth century.Footnote 21 I would now like to consider what the situation surrounding their export at that time reveals about the production and circulation of copper coins within Japan.

In 1634, Joost Schouten (d. 1644), director of the VOC factory in Ayutthaya, wrote to his counterpart in Hirado seeking to import copper coins from Japan to Cochinchina. Specifically, he mentioned:

What will give the greatest profit is what is called the sakamoto. It circulates as the best quality type, and sells at 8 monme 5 fun of chōgin per thousand, but in Cochinchinese currency it sells for 10 monme per thousand. Recently the prices of gold and raw silk have risen steeply and so (it) now sells for 11 or 12 monme.Footnote 22

We can understand from this that the coin known as “sakamoto” was already highly regarded, and it is likely that it had already been exported at other times (and not necessarily just by the Dutch). Yōko Nagazumi suggests that the name “sakamoto” derives from the town of Sakamoto, near Kyoto, where there was a copper mint, which is plausible enough. It is however difficult to agree with her that the minting of the Kan'ei tsūhō had already begun there at that time. The coin certainly was minted at Sakamoto from 1636, so it is likely that the place already had a good track record of copper casting; moreover, the Kefukigusa gives “clay for copper moulds” as a product of the province of Ōmi, in which Sakamoto lies. This in turn suggests that superior-quality copper coins (that is, coins falling within the range of the kyōsen) were being minted in Sakamoto prior to the Kan'ei tsūhō, and it is also logical to think that the copper coins in demand in Southeast Asia are more likely to have been the kyōsen, which mostly bore Song Chinese inscriptions, than the newly minted Japanese coins.

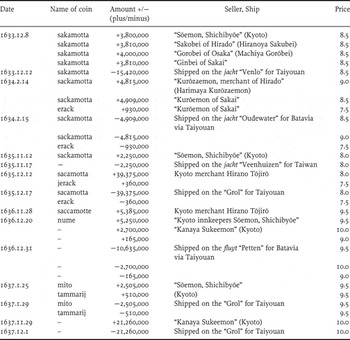

We can confirm details of the export of copper coins by the Dutch between 1633 and 1637 from the Diary (Dagh-Register) of the VOC factory in Hirado. Table 2 shows the amount of copper coin bought in by the factory as “plus”, and the amount exported as “minus”. The table contains information about the name of the coin appearing in each transaction, the name of the seller, the name of the ship it was sent out on, the amount, and the price. It shows that in response to Schouten's request a large volume of copper coins was purchased mainly from merchants in Kyoto and exported on ships heading to Taiwan and Batavia. Other Dutch documents confirm such records of purchases and exports.Footnote 23 Cargoes consisted of between a minimum of around 2,250,000 coins per shipment to a maximum of around 40,000,000 coins. We should note that the coins were called mostly sakamotta, sackamotta and sacamotta, but other names also appear, such as erack, jerack, mito, nume and tammarij. Sakamoto and mito both refer to mints,Footnote 24 and erack/jerack is probably the “Eiraku tsuhō”. Nume refers to the side of the coin that is not inscribed, and probably corresponds to the character nume 滑 meaning “slippery”. Volume 4 of the Butsurui shōko 物類称呼 (Koshigaya Gozan, 1775), in its definition of “zeni” 銭 says, “In the Kinai (capital) region, the obverse [of the coin] is called moji, and in the eastern provinces it is called kata. The reverse is called in Kinai nume and in the eastern provinces name.” Nume may indicate a coin without inscription on either side (mumonsen). However its value compared favourably with that of the sakamoto, so it was probably well formed and comparatively thick. It is uncertain what “tammarij” refers to. In terms of one thousand coins, the value of the sakamoto ranged from 8 monme (mas Footnote 25) to 9 monme 5 fun of silver, that of the erack, 7 monme 5 fun, and that of the nume, mito and tammarij, 9 monme 5 fun. The Kyoto copper exchange at the time (see Table 3) ranged between 18 and 24 monme per one kanmon of silver. Though the prices show a rapid rise, the Dutch factory consistently bought their copper at half the above values, or less.Footnote 26

Table 2. Export of Copper Coins by Dutch Ships, 1633–1637

Source: Dagregister gehouden in Japan 't Comptoir Bij, Archief Nederlandse Factorij Japan NFJ 53 (KA 11686). (Hirado oranda shōkan “shiwakechō” 1635–1637, in Hiradoshi shi, Kaigai shiryō-hen I.)

Note: Price expressed as silver mas (monme) per 1,000 coins.

Table 3. Zeni exchange, Kyoto 1631–1668

Sources: For Myōshinji and Shinjuan, “Myōshinji nōgechō”, “Shinjuan nōgechō”, Daitokuji monjo (Kyōto Daigaku Kinsei Bukka Kenkyūkai ed. Reference Kyōto daigaku kinsei bukka kenkyūkai1962); Kitano Tenmangū shiryō, miyaji kiroku; Kitano Tenmangū shiryō, nengyōjichō; Chōmyōji monjo, Kyōto jūroku honzan kaigōyō shorui 4; Kyōto Reizen chō monjo 1.

Note: The numerical values are silver monme to one kanmon of copper coin.

The merchants who sold coins to the Dutch factory, such as Sōemon 宗右衛門, Shichibyōe 七兵衛 and Kanaya Suke'emon 金屋助右衛門 of Kyoto, Hiranoya Sakubei 平野屋作兵衛 and Harimaya Kurōzaemon 播磨屋九郎左衛門 of Hirado, Machiya Gorōbei 町屋五郎兵衛 of Osaka, and Kawachiya Ginbei 河内屋銀兵衛 of Sakai, maintained constant trade relations with the Dutch, also selling them copper ingots in the same period.Footnote 27 The large volumes of copper coins sold by Hirano Tōjirō 平野藤次郎 of Kyoto, a wealthy merchant who had previously sent trading vessels abroad under the vermilion-seal licence, was directly related to the 1635 ban on overseas trade by Japanese. The Diary reported, “Because of the ban on the vermilion-seal trade, an employee of Hirano Tōjirō had to cancel the planned shipments to Tonkin. He said that if the Company needed copper coins, he would like to supply them.”Footnote 28 With the end of the official trade by Japanese ships, Hirano sounded out the Dutch about buying the copper coins he had intended to export to Tonkin himself. As a result, they were able to buy the copper on very good terms, at 8 monme of silver per one thousand coins.Footnote 29 We can assume that the around 40,000,000 coins bought by the factory that year comprised the shipment that Hirano had intended to send off in his own ship under licence.

We are already familiar with the export of copper coins to Southeast Asia by licensed Japanese ships. Coins were a particularly important item in the Japanese trade with Tonkin and Cochinchina.Footnote 30 Between 1631 and 1635, Chaya 茶屋 sent five ships to Cochinchina; Suetsugu 末次 sent two ships each to Tonkin and Cochinchina; Sueyoshi 末吉 sent three ships to Tonkin; Suminokura 角倉 sent three ships to Tonkin; and Hirano (Tōjirō) sent one ship each to Tonkin and Cochinchina. Between 1632 and 1634 Hirano dispatched one ship per year, though the destinations are not known.Footnote 31 Hirano Tōjirō and Chaya Shirōjirō 茶屋四郎次郎 were involved in exporting copper coins, as can be seen from the fact that around the tenth month of Kan'ei 10 (1633) they placed a check on copper coin exports by the Dutch through the Osaka commissioner (machi bugyō 町奉行), Kugai Masatoshi, Inaba no kami 久貝因幡守正利 (d. 1649), in an attempt to guarantee their own profits.Footnote 32

The Dutch spoke of Hirano Tōjirō as “a merchant trader of high standing in Quinam.”Footnote 33 A report dated 7 October 1636 to the Governor-General of the East Indies, Antonio van Diemen (1593–1645) from Abraham Duycker, oppercoopman at the VOC factory in Taiyoan (Taiwan) gives an account of the vermilion-seal ship trade in Quinam (Cochinchina).Footnote 34 We will focus here on how copper coins were used. First the king's order of six hundred to eight hundred bundles, each with 15,000 coins (9,000,000 to 12,000,000 coins) and 50,000 to 60,000 kin (c. 160 monme) of copper, was delivered at the purchase price, and also distributed among senior officials at the same price. Locally resident Japanese took most of the remaining coins. Employees were sent to the interior where they made advance payments of 100 to 200 monme to local inhabitants and collected raw silk. Because it was possible to raise silkworms for two seasons each year there, money was paid in advance for the next season's raw silk. Thus, the coins brought on the vermilion-seal ships were sold to the king and the officials at cost to expedite trade, and the rest was capital used for advance payments for raw silk locally. This report appears to reflect trading practices by Hirano himself.

Table 2 reveals how often Hirano prepared a shipment of coins for a single trading voyage, and that most of the said coins were sakamoto. As we saw above, Hirano sent out a ship each year from 1632, so we may suppose that he procured and exported nearly 40,000,000 sakamoto per voyage. Since around 10,000,000 coins were sold cheaply to the king and his officials in Cochinchina, this is not the enormous volume it might seem at first glance. The 5,380,000 or so coins that the Dutch factory bought from Hirano in 1636 were either what he had obtained after the abolition of the licensed trade the previous year or stock that he was selling off. The 15,420,000 sakamoto purchased in 1633 and the 9,720,000 sakamoto acquired in 1634 came, not from Hirano, but by a different route. If we add these amounts together, the annual minting of sakamoto must have been in excess of 50,000,000 (50,000 kanmon). As we have seen, Chaya Shirōjirō appears also to have exported copper coins, and if we assume that he purchased them from Sakamoto, the amount minted there increases even further. Sakamoto had already been a major producer of kyōsen, and there must have been a marked increase in the amount of coin minted there as compared to earlier times. The basis for such growth was probably the technological revolution and improvements to the whole minting system that marked the division between the medieval and early modern periods.

The sakamoto comprised the majority of coin exports down to 1635, but in the following year the coin type changed. Since Sakamoto began minting the Kan'ei tsūhō from the second half of 1636, production of the sakamoto (kyōsen) would have ceased. The trend towards a rise in price per thousand coins that occurred after 1636 and the issue of the Kan'ei tsūhō was part of a general price rise that included the sakamoto. Around the same time, Batavia ordered the Hirado factory to mint between 180,000 and 200,000 gulden worth of copper coins to bolster the Quinam trade, and it was planned to send them to Taiyoan (Taiwan) together with a small amount of lump copper.Footnote 35 This plan did not however eventuate. With the formation of new minting infrastructure in Japan, the source of kyōsen supply ran dry, while supply-and-demand pressure on the coins pushed export prices up. And when the government banned the export of copper in 1637, the Dutch factory hastened to procure copper coins in place of copper bullion. The Hirado Diary notes, “The emperor has strictly forbidden even the smallest amount of copper being taken out of Japan. Instead of the 6,000 piculs of copper ordered, we are sending 1,200 bundles of copper coins to Cornelis Caesar (1610–1657) at the Dutch factory in Quinam.”Footnote 36 Twelve hundred bundles represented 18,000,000 coins. The Dutch factory continued to collect copper, and in November the same year bought 21,260,000 copper coins from “Kanaya Sukeemon” in Kyoto, to make up the final shipment the following month.Footnote 37

PLANS TO MINT A NEW COPPER COIN

François Caron (1600–1673), an official at the Dutch factory in Hirado (and later its opperhoofd, or manager, from 1639 to 1641), mentions money and weights and measures in the Beschrijvinghe van het Machtigh Coninckryck Japan (A True Description of the Mighty Kingdom of Japan).

They have besides their Gold and Silver Coins, a sort of Copper Monies, which they call Casies, and it is of differing value in many of the Kingdoms, but His Majesty hath resolved to recoin these Casies into one fashion, to which end he hath ordered all the old ones to be turned in, and bought them of their owners at their full worth and price, wherewith his Officers have been busied these four years.Footnote 38

Casies refers to the copper zeni, “Kingdoms” are the daimyo's domains, and “His Majesty” is the Tokugawa Shogun. From its content, it is clear the passage refers to the minting of the Kan'ei tsūhō. The Shogun had determined to mint this new coin to resolve a situation where coins of differing composition and value were circulating in the various domains. Caron's comment that it had taken four years to accumulate old coins as raw material for minting is of great interest. It is thought he wrote this passage in the latter part of 1636, so if we take his comment at face value, the government had been buying up old coins since 1633. No supporting evidence for this statement has been found, but the suggestion that the plan to mint new coins had gone through a preparatory period of several years prior to the issue of the Kan'ei tsūhō in 1636 merits further study.

When the Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu visited Kyoto in 1634, Hosokawa Tadatoshi, who was then residing in the capital, wrote to the Nagasaki commissioner (Nagasaki bugyō), Sakakibara Motonao 榊原職直 (1586–1648), in a letter dated int. 7.19 that he had received a report that “To Samon-dono and Matsu Etchū-dono” (Toda Ujikane 戸田氏鉄, 1576–1655, lord of Amagasaki in Settsu, and Matsudaira Sadatsuna 松平定綱, 1592–1652, lord of Ōgaki in Mino) had been ordered to make a study about converting all coins in current use to new coins.Footnote 39 Though this was only hearsay, it is the earliest known reference to the government's plan to mint a new copper coin. The study would have looked carefully into the possibility of successfully carrying out a plan to exchange old coins for newly minted ones on a scale never before attempted, as well as organizing how it was to be achieved.

When we consider Hosokawa's remark in conjunction with the statement in the True Description of the Mighty Kingdom of Japan, the former seems to be the more reliable. Caron reported that, as of the latter part of 1636, the buying up of old coins had been going on for four years. Table 3 shows that the exchange rate for zeni in Kyoto from around 1633 had indeed gone beyond the standard 18 monme per kanmon, and in 1636, when the Kan'ei tsūhō was issued, it had risen to as much as 24 monme. Such a rise is consistent with Caron's description. But the rise can be explained in a different way. Iemitsu's planned visit to Kyoto in 1634 necessitated active procurement of sufficient copper coins for travelling expenses, and it is very likely that this is what caused the price of zeni to go up. And the rise after 1634 can be explained as the result of people buying up old coins in anticipation of the minting of new coinage while awaiting the outcome of Toda and Matsudaira's study.

It cannot have been a coincidence that this study had been ordered at just the time when Iemitsu was visiting the imperial capital. Not far from Kyoto was Sakamoto, where kyōsen were being minted on a large scale for use in the domestic market and where coins made for export were procured by the vermilion-seal merchants. This would not have escaped the notice of Iemitsu and his advisers, and it is hardly surprising that the government should have been concerned, given that the good quality of Sakamoto copper coins and their large-scale production encouraged their unrestricted export. To what extent the institution of the ban on Japanese travelling abroad and the end of the licensed trading system the following year (1635) were related to the plan to mint a new coin as a result of Toda and Matsudaira's study cannot be determined. However, the surest and speediest way to replace the old coins (kyōsen) with a large supply of new ones would have been to secure the traditional production sites and reorganize workers and facilities to mint them. Thus Sakamoto attracted attention, and it is likely that Toda and Matsudaira recommended a strategy for putting the plan into action. All in all, the various pieces of evidence that we have, taken together, suggest that the plan to mint the Kan'ei tsūhō for circulation on a nationwide basis was launched in 1634 when Iemitsu visited Kyoto, not earlier.

At the end of the sixth month of 1635, the Bakufu initiated a survey throughout Japan of the money then circulating.Footnote 40 The rōju 老中 (“Elder”: senior Bakufu counsellor) Sakai Tadakatsu 酒井忠勝 (1587–1662) summoned the various domain karō 家老 (senior officials) to a meeting to find out what currencies (“gold, silver, copper coins, rice”) were in circulation, in order to procure what was needed. The Mōri lord sent his senior representative in Edo (Edo kahanyaku 江戸加判役), Ihara Gen'i 井原元以 (d. 1642), and the Hagi domain deputy in Edo (kōginin 公儀人), Fukuma Naritatsu 福間就辰, to the meeting. Ihara reported that the chōgin was used in Suō and Nagato, that it was exchanged for haifuki for smaller transactions, and that gold was not used. “The copper coins (zeni) used are really poor-quality kuninamisen (coins circulating within the domain only).” Rice was not used for small transactions. Bakufu financial comptrollers (kanjōkata 勘定方) Ina Tadaharu 伊奈忠治 (1592–1653), Sugita Tadatsugu 杉田忠次 and Sone Yoshitsugu 曽根吉次 heard the reports and recorded the responses. From the expression “really poor-quality” we can surmise that the coins were obviously of low quality compared with the standard kyōsen. They may have been the 8,855 kan of kunisen and the 94 kan of Kawachisen mentioned in 1632 by Masuda Motonaka 益田元祥 (1558–1640), karō of Hagi domain, in his index of deliveries of domain products.Footnote 41 The Mōri, as if reflecting their political relationship with the Bakufu, minted and circulated poor-quality domain copper coins that did not compare favourably with the good-quality kyōsen. Furthermore, the Bakufu had already given up on the idea of using the kyōsen in direct link with the East Asian currency zone, and was moving towards a new and total currency unification through the new coin.

ISSUE AND CIRCULATION OF THE KAN'EI TSŪHŌ

Let us now look at the unification process by studying how the old coins were eliminated once the Kan'ei tsūhō was issued, and how those daimyo who had previously minted copper coins for use in their own domains reacted to it.

On the fifth day of the fifth month of 1636 (Kan'ei 13), official noticeboards in Edo announced the issue of the Kan'ei tsūhō (from 6.1). The following day, the rōju Sakai Tadakatsu called the Edo deputies of the daimyo to his house and in the presence of the other rōju notified them of the planned issue.Footnote 42 Nabeshima Katsushige 鍋島勝茂 (1580–1657), lord of Saga domain in Kyushu, wrote to his domain karō, Taku Shigetoki 多久茂辰, that the use of local currencies would be banned from the beginning of the sixth month and that the new official coin would then go into circulation.Footnote 43 This reveals that while the public noticeboards said that the new coin would be used in conjunction with the old, there was private communication to the effect that the old coins could no longer be used after the first day of the sixth month, and so Katsushige was reminding his officials to ban the circulation of old coins on the domain from that day.

The order to mint the coins was conveyed to Kyoto and Osaka on the seventh day of the fifth month, and on the twentieth day, two constables (kachimetsuke 徒目付) were despatched to Ōtsu bearing the text displayed on the noticeboards. Around the same time, there was an acute shortage of copper coins along the main highways, and as an emergency measure, the military officials (ōbankata 大番方) Kuru Masachika 久留正親 and Obata Shigemasa 小幡重昌 were sent to Osaka to distribute “old coins” from the Bakufu treasuries in Osaka and Kakegawa along the Tōkaidō, the Nakasendō and the Mino Road. Along the Tōkaidō, each post station received 100 kanmon, and along the Nakasendō and the Mino Road between Moriyama and Nagoya, each post station received 60 kanmon. On 6.23, the inspector (metsuke 目付) Ishigaya Sadakiyo 石谷貞清 (1594–1672) and others were sent to the Kyoto region to make sure people were complying with the orders about the new coin and to inspect the minting at Sakamoto; they returned to Edo in the ninth month. On 6.26, orders were issued to recruit mint workers in Osaka, and probably the recruitment of mint workers in Kyoto also occurred at around the same time.

Consequently, minting in the Kyoto region could have started no earlier than the autumn. Hosokawa Tadatoshi wrote in a letter dated 11.10 to the Nagasaki commissioner Sakakibara Motonao that the shortage of copper coins was continuing on the highways between Kyoto and Edo and was causing a lot of inconvenience.Footnote 44 In the circumstances, on 11.26 the Bakufu, in order to increase and disperse the production of copper coin, ordered that mints be established in eight domains: Mito, Sendai, Yoshida in Mikawa, Takada in Echizen, Matsumoto in Shinano, Okayama, Nagato and Takeda (the domain of Nakagawa Naizen in Bungo). Their daimyo were required to mint the coins according to the sample sent, to sell them off everywhere at fixed prices, and to recruit staff themselves. The government established these mints strategically to spread the new, standardized coins throughout the country, as the use of samples suggests. In 1637 the mints began full-scale operations, and the Bakufu, in banning the export of copper, sought to secure their supply of raw material.Footnote 45 And so, with minting underway, the new coins went into circulation.Footnote 46 As far as we can see from the Kyoto exchange records (Table 3), prices finally fell after 1639.

The daimyo, following the express wishes of the Bakufu, hastened to ban the use of the old coinage and introduce the Kan'ei tsūhō. The Date lord of Sendai had sent a copy of the public announcement about the new coin to the domain through the Edo karō in a co-signed letter dated Kan'ei 13.5.9 and ordered that public noticeboards be erected throughout the domain to make it a matter of common knowledge.Footnote 47 The Asano of Hiroshima, too, notified the domain through the karō in a letter dated Kan'ei 13.5.29, directing that public noticeboards be erected both in the domain and in post stations along the Sanyōdō (highway) and that conveyance charges be paid in copper coin rather than in silver as in the past.Footnote 48 Instances had already been seen since the time of the kyōsen of daimyo switching to copper as the basis of conveyance charges as they organized roads and traffic within their domains, but instances of copper taking over from silver as the standard after the introduction of the Kan'ei tsūhō can be found, not only by the Asano lords but also by the Ikeda of Tottori. Through the institution and supply of a standardized coin, the role of copper coins as a means of payment on the highways spread throughout the country.

The above-cited letter from Nabeshima Katsushige to his domain confirms that the Bakufu expected the individual daimyo to acquire the new coins independently and be responsible for sending them to their domains.Footnote 49 Shimazu Iehisa 島津家久 (Tadatsune 忠恒, 1576–1638) thought he would purchase some new coins in Osaka on his way back to his domain in Satsuma, but his Edo karō considered that there was not much time before the changeover on 6.1, and so it would be better to request merchants in Osaka and Sakai to make the purchase.Footnote 50 In fact it was actually impossible to change to the new coinage on that date, so their qualms were in the end groundless.

The situation was serious for daimyo who had until now minted their own coins in their domains. The Mōri forbade the use of the old akusen in Hagi from 6.5, and ordered that rice and silver be circulated as an interim measure until the new coins could be bought from the Sakamoto mint.Footnote 51 Their mint workers were engaged by the Edo mint. The Shimazu too had minted their own coins, the kajikisen, and they inquired of Fukasu Kurōemonnojō 深栖九郎右衛門尉, a vassal of the rōju Sakai Tadakatsu, whether it was possible for the old coins to remain in use for the time being.Footnote 52 In the second month of the following year (1637), the Shimazu put in a request to the Bakufu to mint the Kan'ei tsūhō in Satsuma, but it was not approved because mints had already been set up in other places.Footnote 53 However, they were allowed to use the old coins, which meant they immediately avoided a loss of around 1,000 kanme of silver which they would have suffered if the old coins had been scrapped.Footnote 54 Probably preserving the means of circulation in the domain and avoiding a loss as far and for as long as possible had been the intent of the daimyo all along. When the Kan'ei tsūhō were brought into use in Satsuma, the kajikisen remaining in the domain treasury were exported to the Ryūkyūs.Footnote 55

When the Bakufu ordered the eight mints to be set up in various domains in the eleventh month of 1636 (Kan'ei 13), mint workers became an issue. The Mōri requested the Bakufu on 1.8 the following year to be allowed to mint the new coins, and after that entered into negotiations with the copper mint in Edo over the employment of skilled workers. After the domain was prohibited from minting its own coins, its workers were sent to the Edo mint; but now the domain was asking for them back. Various incidents had occurred: a man from the domain who had been engaged by the Edo mint fled back home, and another who had been employed by the Okayama mint submitted an illegal petition in Edo.Footnote 56 Since any incident involving someone from the domain, even if they were working outside it, concerned the daimyo, they tried to prevent people leaving who were likely to cause trouble outside. Likewise, behind the Shimazu request to mint Kan'ei tsūhō in the domain was the preservation of its mint to provide a workplace for its workers to restrict them from seeking work outside. After 1637, when the request was turned down, workers who had minted the kajikisen left for the Kyoto area, and as can be seen in a document dated Kan'ei 15 (1638) 8.8, if workers from Satsuma domain went to another area and got involved in manufacturing akusen (“privately minted” coins), this could cause difficult problems for their domain and so it was decided to recall them.Footnote 57 Even though with the issue of the Kan'ei tsūhō copper coins were being officially minted, it must have been difficult to eliminate the possibility that the mobility of mint workers would lead to private minting or the casting of akusen.

The quality of the new coins deteriorated somewhat from around 1639,Footnote 58 and as their circulation came to a standstill and the mints were forced to halt operations, mint workers suffered a decrease in the places they could work. As a result, problems associated with forgery and illicit minting began to surface. In 1639 and 1640, illicit minting of Kan'ei tsūhō was revealed to have occurred around Sakamoto.Footnote 59 On the Kyoto zeni exchange (Table 3), one kanmon of zeni fell in value from above 20 monme of silver in 1639 to below 15 monme the following year. On Kan'ei 17 (1640) 11.22, the eight domain mints closed, and on 12.23 the following year (1641), zeni mints in three places in the Kansai region also ceased operations. Probably the Edo zeni mint also stopped at this time. Half the unsold coins stockpiled at the four mints in Tokugawa domains were sold at the official rate of 4 kanmon for one gold ryō to subsidize the bankrupt mints.Footnote 60 In the second month of Kan'ei 20 (1643), the government proclaimed throughout the country that the minting of the new coins would be prohibited everywhere,Footnote 61 and this was drafted into a final law. It was then that the private minting and counterfeiting of copper coins was decreed a state crime.Footnote 62

From around 1640, the whole country suffered what has become known as the Kan'ei famine, at the same time as there was an oversupply of copper coins and a fall in the exchange rate against gold and silver currencies. Urban workers who lived on their wages, as well as the post system maintained by the Bakufu, were particularly vulnerable to both the famine and the scarcity of copper currency, and in 1642 and 1643 the government gave various kinds of aid, with the particular intention of supporting the highways and post stations upon which it depended. In brief, besides providing rice, the government bought up copper coins to restore the exchange rate. The purpose of the official purchase was to bring stability to the currency market. Having succeeded in providing the homogenous Kan'ei tsūhō, the Bakufu, in dealing with the administrative mismanagement that had resulted in overproduction, acquired the means of bringing the zeni exchange under control.

CONCLUSION

During the early modern period, the government-authorized three-currency system spread to every part of Japan, but this did not mean “unification” in the sense that all other currencies were abolished. Backed by the authority and prestige of the Bakufu, the official central currencies were made standard everywhere, and any attempts to block their circulation were severely punished under the law. All the same, other coins were permitted within the domains. Early in the period, domain gold and silver, as well as distinctive copper coins, circulated, and domain paper currencies (hansatsu 藩札) also came into use. However these were never on an equal standing with the three standard currencies, which enjoyed both political and economic prestige. This form of currency unification marks out the early modern period from the times before and after it.

As a result of the activity of the gold and silver mints and the decline in gold and silver production, Bakufu gold and silver currencies spread throughout the country in the middle of the seventeenth century, though in certain districts low-grade cupelled silver still existed. Since the Bakufu had restricted silver exports to the chōgin, high-grade cupelled silver could not be obtained and so gradually a clear demarcation arose between foreign and domestic in the East Asian silver currency zone.

It was a similar story with copper coins. The kyōsen had been directly linked with the East Asian copper currency zone, but as a result both of controls on trade and a developing national consciousness, the Bakufu turned to minting its own coin, the Kan'ei tsūhō. The kyōsen may be considered the final stage in the copper coinage system that had been in effect among the people since medieval times, its circulation managed and selected according to the private market. As the proliferation of anti-shroffing edicts at the beginning of the period indicates, copper coinage was unstable both in terms of supply and quality, but on the other hand, it was a lucrative trade item and some mints expanded to produce tens of millions of coins annually for export. Thus the decision to mint the Kan'ei tsūhō included the desire to unify the currency domestically, as well as to take over and control production of the kyōsen as it was linked to foreign trade. Towards the end of the Kan'ei era there appears to have been a plan to export surplus Kan'ei tsūhō from the Osaka mint, but it was not implemented due to opposition from Bakufu advisers, and the export of copper coins was put off for the time being.Footnote 63 The minting of the Kan'ei tsūhō and the later ban on the export of copper signal the beginning of Japan's withdrawal from the East Asian copper currency zone.

As a result of the diffusion of the Kan'ei tsūhō, coins circulating domestically tended to become increasingly standardized throughout the country, though in fact a certain degree of regionality and stratification remained. First, there was the continuing existence of ei 永 and kyo 京. Accounting based on the Eiraku tsūhō continued throughout the period in the financial zone comprising Kantō and the eastern provinces, where it was long used as a convenient unit expressing one thousandth of a ryō. The kyōsen too functioned in a part of the eastern region as the standard coin for tax assessment.Footnote 64 This was not limited to the time before the Kan'ei era. At Uchiura on the Izu peninsula documents connected with the assessment of basic land tax (nengu 年貢) as well as of other miscellaneous taxes are shown using the kyō unit right until the final years of the Edo period.Footnote 65 The boat dues (funayaku kin 船役金) in Edo were also shown in kyōsen from the Kan'ei era, and we can confirm that this applied also in the Genroku (1688–1704) and Shōtoku (1711–1716) eras.Footnote 66 Probably this reflects a survival from the time the tax assessments were first made. When paying taxes, though the exchange of gold one ryō = four kanmon of kyōsen applied, it is thought that conversion was according to the actual gold/zeni exchange. At the stage when they were diverging from the copper currency in circulation, ei and kyō became the money of account used when assessing taxes.Footnote 67

Then, we have the existence of large-denomination copper-based notes. In the latter part of the Edo period, notes with a face value of above one kanmon were being widely issued in the provinces of Mutsu, Dewa, Etchū, Izumo and Hyūga. Because transactions in these areas were made mainly in terms of fragmental copper coins, when large transactions were settled, it was a matter of convenience to issue a copper-based note in a large denomination.Footnote 68 It is of interest that many of the areas where notes were prevalent were those where coins without inscription (mumonsen) had circulated in the early part of the Edo period. With just a few exceptions, mumonsen were largely thin and light, and were of low value compared with coins like the kyōsen. If these were the lowest units of transaction at a local level, it is unlikely that they would have disappeared easily even when official standard coins like the kyōsen and Kan'ei tsūhō were introduced. There is also a strong possibility that even if the actual coins disappeared they remained as units of account. An entry from 1818 in the Kagiya nikki, the diary of a wealthy Morioka merchant, notes the insufficiency of copper coins, and says “Because akusen (“base coins”) as well as kosen (“old coins”) are in very short supply, all people are suffering hardship in their daily lives.”Footnote 69 We do not know what exactly these akusen and kosen were, but this is a strong hint that these coins were the everyday currency. Many questions remain to be resolved in the study of copper coins in early modern Japan, but we may suppose that at the lowest level akusen continued to be used as regional currency as they always had been.