Introduction

Metasyntactic ability (MSA) refers to the capacity to reflect about syntactic aspects of language (i.e., word classes and their organization in sentences) and to deliberately control them (Gaux & Demont, Reference Gaux, Demont, Barre-De and Lete1997; Gaux & Gombert, Reference Gaux and Gombert1999a, Reference Gaux and Gombertb; Gombert, Reference Gombert1992; Tunmer, Nesdale & Wright, Reference Tunmer, Nesdale and Wright1987). It appears to be associated with word recognition (Gaux & Gombert, Reference Gaux and Gombert1999a, Reference Gaux and Gombertb; Rego & Bryant, Reference Rego and Bryant1993; Tunmer & Hoover, Reference Tunmer, Hoover, Gough, Ehri and Treiman1992) and with reading comprehension – in L1 (e.g., Bowey, Reference Bowey1986; Demont & Gombert, Reference Demont and Gombert1996; Gombert & Colé, Reference Gombert, Colé, Kail and Fayol2000; Nation & Snowling, Reference Nation and Snowling2000; Tunmer, Reference Tunmer1990; Tunmer, Herriman & Nesdale, Reference Tunmer, Herriman and Nesdale1988; Ziarko, Gagnon, Mélançon & Morin, Reference Ziarko, Gagnon, Mélançon and Morin2000) and at least in the early stages of development among heritage language children (e.g., Geva & Siegel, Reference Geva and Siegel2000; Lefrançois & Armand, Reference Lefrançois and Armand2003; Lesaux, Rupp & Siegel, Reference Lesaux, Rupp and Siegel2007; Masny, Reference Masny2006). By heritage language children, we mean children that are raised in a home in which a non-majority language is spoken, speak or at least understand the language and are “to some degree bilingual in that language and in the majority language” (Valdés, Reference Valdés, Peyton, Ranard and McGinnis2001, p. 2).

Additionally, some researchers looked at possible differences between heritage language and monolingual children's MSA. Although some MSA studies observed an advantage for heritage language children over monolinguals (e.g., Cromdal, Reference Cromdal1999; Davidson, Raschke & Pervez, Reference Davidson, Raschke and Pervez2010), others have shown that heritage language children tend to present deficits in their MSA when compared with their monolingual majority-language-speaking peers (e.g., Da Fontoura & Siegel, Reference Da Fontoura and Siegel1995; Jongejan, Verhoeven & Siegel, Reference Jongejan, Verhoeven and Siegel2007; Lesaux & Siegel, Reference Lesaux and Siegel2003; Lipka et al., Reference Lipka, Siegel and Vukovic2005). For instance, in their study examining the relationship between reading difficulties in both English and Portuguese among Portuguese heritage language children living in an English-speaking environment and being schooled in English (aged 9–12 years), Da Fontoura & Siegel (Reference Da Fontoura and Siegel1995) found that even though the scores they obtained on a reading comprehension task were comparable to those of their English-speaking counterparts, they scored significantly lower on the English metasyntactic measurement, which was a completion task (oral cloze) based on Siegel and Ryan (Reference Siegel and Ryan1988).

In the task used in these studies, the participants had to complete orally a missing word in a sentence read to them. One problem related to the use of the completion task to measure MSA is the difficulty to determine whether the participants resorted to syntactic and/or semantic information in order to respond (Blackmore & Pratt, Reference Blackmore and Pratt1997; Gaux & Gombert, Reference Gaux and Gombert1999a). Moreover, the answers provided greatly depend on the participants’ lexical knowledge (Gaux & Gombert, Reference Gaux and Gombert1999a). We, thus, believe their results could, at least in part, be attributable to the measurement instrument they used.

The measurement of MSA has been at the center of a debate for years (e.g., Birdsong, Reference Birdsong1989; Cain, Reference Cain2007; Demont, Reference Demont1994; Demont & Gombert, Reference Demont and Gombert1996; de Villiers & de Villiers, Reference de Villiers and de Villiers1972; Simard & Fortier, Reference Simard, Fortier and Han2007). Researchers do not seem to agree on what instruments really allow the assessment of MSA, saying that some do not necessarily lead to the use of conscious and intentional processes (Gaux & Gombert, Reference Gaux and Gombert1999a, p. 172). MSA tasks typically correspond to judgment, correction, localization, explanation, completion, repetition and replication tasks (e.g., Correa, Reference Correa2004; Gaux & Gombert, Reference Gaux and Gombert1999b). In judgment tasks, participants have to indicate whether the sentences provided are grammatical or acceptable (Armand, Reference Armand2000; Bialystok, Reference Bialystok2001a; Demont, Reference Demont1994; de Villiers & de Villiers, Reference de Villiers and de Villiers1974) whereas in the correction task, they have to correct ungrammatical syntactic features found in sentences (Armand, Reference Armand2000; Bowey, Reference Bowey1986). In the localization task, the participants are simply asked to identify an ungrammatical syntactic feature in a sentence (Smith-Lock & Rubin, Reference Smith-Lock and Rubin1993). Researchers also ask participants to explain syntactic errors as a way to measure MSA (e.g., Galambos & Goldin-Meadow, Reference Galambos and Goldin-Meadow1990). As mentioned previously, the completion task (also called oral cloze) requires the participants to complete a sentence using the best possible word they can think of (Tunmer et al., Reference Tunmer, Nesdale and Wright1987). In the repetition task, participants are asked to repeat orally ungrammatical sentences that are read to them respecting the ungrammaticality (Armand, Reference Armand2000; Bowey, Reference Bowey1986; Demont, Reference Demont1994; Gaux & Gombert, Reference Gaux and Gombert1999a, Reference Gaux and Gombertb). Finally, some researchers resort to what they call a replication task (Gombert, Gaux & Demont, Reference Demont1994; Gombert, Martinot & Nocus, Reference Gombert, Martinot and Nocus1996; Lefrançois & Armand, Reference Lefrançois and Armand2003; Nocus & Gombert, Reference Nocus and Gombert1997; Simard & Fortier, Reference Simard, Fortier and Han2007). In such a task, the participants are asked to locate an error that is presented in an ungrammatical sentence and to reproduce the same type of error in a grammatical sentence.

This great variety of tasks used in MSA studies (see Blackmore, Pratt & Dewsbury, Reference Blackmore, Pratt and Dewsbury1995; Simard & Fortier, Reference Simard, Fortier and Han2007) could explain the considerable variation in the results obtained (Blackmore et al., Reference Blackmore, Pratt and Dewsbury1995, p. 410). In order to verify this assumption, researchers investigated MSA task demand (e.g., Cain, Reference Cain2007; Simard & Fortier, Reference Simard, Fortier and Han2007). Some looked at factors that interact with performance (e.g., Bowey, Reference Bowey and Assink1994; Cain, Reference Cain2007; Gaux & Gombert, Reference Gaux and Gombert1999a). For instance, Bowey (Reference Bowey and Assink1994) underscored the impact of semantic processing strategies used by learners to perform MSA tasks on the results they obtain. In the same vein, Gaux & Gombert (Reference Gaux and Gombert1999b) argued that classic tasks of repetition, localization, correction and judgment do not allow to measure metalinguistic ability with certainty, since a variety of factors other than an intentional reflection on the language may help to perform them (pp. 69–70). These factors correspond, among others, to the participant's implicit knowledge of the language examined, their vocabulary knowledge, and their capacity to produce sentences. According to Gaux and Gombert (Reference Gaux and Gombert1999a, Reference Gaux and Gombertb), the only task measuring MSA is the replication task, since a correct replication of an error implies that the participant explicitly analysed the language in order to know the nature of the ungrammaticality and intentionally reproduced the error (Nocus & Gombert, Reference Nocus and Gombert1997). Nocus and Gombert (Reference Nocus and Gombert1997) add that this type of task leads to substantially lower results than all the other tasks among native speakers.

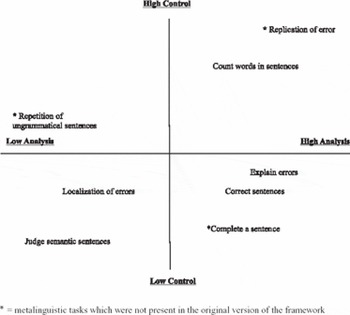

Others, such as Ricciardelli (Reference Ricciardelli1993) and Simard & Fortier (Reference Simard, Fortier and Han2007), looked at MSA task demands in terms of their levels of analysis of knowledge and control of attention demands based on Bialystok's work (e.g., Reference Bialystok and Bialystok1991, Reference Bialystok, Pratt and Garton1993, Reference Bialystok1999, Reference Bialystok2001a, Reference Bialystokb). Bialystok's framework (Reference Bialystok2001a) can be used to classify metalinguistic tasks according to two dimensions (see Figure 1). On the one hand, there is the level of analysis of knowledge, which corresponds to knowledge explicit level of structure and organization. On the other hand, control of attention refers to the level of attentional demand required to access and to activate the mental representations involved when performing various tasks (Bialystok, Reference Bialystok2001a). These two dimensions are represented as orthogonal axes. They define a Cartesian space in which their degree of involvement in each quadrant is indicated (Bialystok, Reference Bialystok2001a). Lower levels of both analysis and control are represented in the lower left quadrant and higher levels of both, in the upper right quadrant (Bialystok, Reference Bialystok, Pratt and Garton1993). Metalinguistic tasks can be placed on this Cartesian space according to the levels of both analysis and control they call upon. As Bialystok (Reference Bialystok, Pratt and Garton1993, p. 228) puts it, “[t]he placement of metalinguistic tasks in this matrix takes increasing levels of analysis and control required for the solution to specific tasks to be indicated by higher values along the x and y axes respectively”. In Bialystok's framework (Reference Bialystok2001a), judgment and identification of error tasks are located in the lower left quadrant, indicating lower levels of analysis and control whereas, both correction and explanation tasks are located in the lower right quadrant, indicating high levels of analysis. Bialystok does not give us explicit indications regarding the levels of analysis and control required by a repetition task. However, since it requires that the subject has to suppress the natural tendency to normalize erroneous utterances resorting to control (Gombert, Reference Gombert1992) without the need of highly analysed knowledge to perform it, we place this task in the higher left quadrant of the model. The replication task, considered by Gaux and Gombert (Reference Gaux and Gombert1999a, Reference Gaux and Gombertb) as the only one measuring MSA, was placed in the upper right quadrant by Simard & Fortier (Reference Simard, Fortier and Han2007), since it requires the use of the most explicit knowledge (e.g., Gaux & Gombert, Reference Gaux and Gombert1999a) and a high demand on control processes. Such a task requires that the participants focus their attention on both ungrammatical and grammatical sentences in which they have to replicate the error, while inhibiting irrelevant information. Finally, the completion task such as the one used in Da Fontoura and Siegel (Reference Da Fontoura and Siegel1995), calls for lower levels of control and higher levels of analysis since learners must have enough knowledge to make predictions about what is required to complete the sentence (e.g., Lipka et al., Reference Lipka, Siegel and Vukovic2005), but without having to inhibit any aspect of the sentence to complete the task. We present in Figure 1 an adapted version of Bialystok's framework for metalinguistic tasks in which we added the replication, completion and repetition of ungrammatical sentences tasks (identified with a star). These tasks do not appear in the original version of the framework (Bialystok, Reference Bialystok2001a).

Figure 1. Adapted version of Bialystok's (Reference Bialystok2001a) framework for metalinguistic tasks.

Generally speaking, previous studies (e.g., Bialystok, Reference Bialystok1986, Reference Bialystok1988; Galambos & Goldin-Meadow, Reference Galambos and Goldin-Meadow1990) show that heritage language children demonstrate an advantage over monolinguals specifically on tasks requiring higher levels of attentional control (Bialystok, Reference Bialystok1992, Reference Bialystok1999, Reference Bialystok2007), since, as Davidson et al. (Reference Davidson, Raschke and Pervez2010, p. 13) put it, “bilingualism requires early attention to forms of the language”. This might, in part, explain the results obtained in studies investigating MSA using a completion task which requires, we argued, lower levels of attentional control (e.g., Da Fontoura & Siegel, Reference Da Fontoura and Siegel1995). In these studies, monolinguals outperformed the heritage language children living in an English-speaking environment.

However, it should be noted that to see such “bilingual advantage”, as it is called by some (e.g., Bialystok, Reference Bialystok2001a), on metalinguistic tasks requiring higher levels of attentional control, speakers must demonstrate higher commands in both languages (e.g., Galambos & Hakuta, Reference Galambos and Hakuta1988; Galambos & Goldin-Meadow, Reference Galambos and Goldin-Meadow1990). In previous studies in which monolinguals obtained better scores on MSA tasks, they were being compared to heritage language children (e.g., Da Fontoura & Siegel, Reference Da Fontoura and Siegel1995; Lesaux & Siegel, Reference Lesaux and Siegel2003; Lipka et al., Reference Lipka, Siegel and Vukovic2005). According to Rothman (Reference Rothman2009, p. 156), it is expected that heritage language children's language competency “will differ from that of native monolinguals of comparable age”. Therefore, it could also be that the heritage language children's level of competency in both languages might not have been high enough to help them benefit from any “bilingual advantage”.

Given the above considerations, the research question investigated in the study was:

Do heritage language children with high levels of competency in both the majority and minority languages demonstrate better scores at the MSA tasks than monolinguals with similar reading and language competency?

On the basis of what was previously presented, we expected our heritage language participants with comparable language proficiency and reading comprehension skills to monolingual speakers and strong commands of both majority and minority languages to obtain better scores than the monolingual children on MSA tasks calling for higher levels of control.

Method

In a cross-sectional study, we verify whether heritage language children would obtain better scores on MSA tasks believed to call for higher levels of attentional control, namely a repetition task and a replication task, than monolingual children with comparable reading comprehension skills and language proficiency.

Participants

A total of 44 participants took part in the study, 24 girls and 20 boys. Half of them were French-L1-speaking children (FSC; n = 22), as identified by the language they use to communicate with their mother and the report of no other language being spoken at home. The remaining participants were Portuguese heritage language children (PHC; n = 22). All PHC, were of Portuguese origin and were born in Canada. They were all enrolled in a heritage language program, either as an extra-curricular activity at the regular school, or at a Saturday school. Portuguese (as a heritage language) was chosen since only a few studies investigated this population in the English-speaking part of Canada (e.g., Da Fontoura & Siegel, Reference Da Fontoura and Siegel1995) and, to our knowledge, no other study looked specifically at that language group in Québec, a Canadian province in which French is the official language. They were from the same middle socioeconomic context as their French counterparts. The mean age of the participants is 10.9 years. Although the FSC were slightly younger (M age = 10.6; age range = 7.7–13) than the PHC (M age = 11.1; age range = 7.8–13.8), there was no significant difference related to age, F(1,42) = 1.179; p < .3.

Measurement instruments

A series of instruments were used to measure MSA in French, and reading comprehension skills and language proficiency in both French and Portuguese, as well as to collect information on the participants’ background. These instruments are described in what follows.

Metasyntactic ability

In order to assess participants’ MSA in French, two tasks were used: a repetition task and a replication of error task (see Appendix). Our MSA tasks targeted French syntactic features commonly examined in prior studies, i.e., the placement of clitic pronouns (e.g., Kaiser, Reference Kaiser and Meisel1994), and the formation of passive sentences (e.g., Kail, Reference Kail1983), causative sentences (e.g., Abeillé, Godard & Miller, Reference Abeillé, Godard and Miller1997), comparative constructions (e.g., Bautier-Castaign, Reference Bautier-Castaing1977) and relative clauses (e.g., Walz, Reference Walz1981).

Additionally, our instruments’ objective is to obtain a measure of the participants’ ability to manipulate syntactic features in general and not their ability to specifically manipulate one type of construction. Therefore, various constructions of the selected syntactic features were included in the instruments. These constructions are detailed below.

The repetition of ungrammatical sentences task (Bowey, Reference Bowey1986; Demont, Reference Demont1994) requires the participants to repeat deviant sentences exactly as they heard them without correcting the errors encountered. An example of an item presented to the participants in our study, in this case containing an error about the choice of the relative pronoun, would be *Le film quoi jouait à la télévision est terminé “*The movie who was playing on television is over”. The task used in this study consisted of 20 sentences of an average length of 15 syllables (min = 13, max = 17, SD = 1.08), each containing a syntactic error (there were also 20 fillers corresponding to 20 grammatical sentences). More specifically, there were six items about the choice of relative pronouns (four with simple relative pronouns and two with complex relative pronouns). There were five items related to comparatives, with two in which que was absent and three in which que was replaced by de. Eight items targeted clitic placement among which four involved the placement of simple clitic pronouns and two involved the placement of a clitic pronoun in a causative construction (considered to be more difficult) and finally two targeted the placement of two clitics in the same sentence. Two items targeted causative constructions and two others targeted passive constructions, and in all cases the errors were related to the order of the constituents. Sentences were ordered from the easiest to the most difficult based on an interratter agreement made by three separate French-speaking judges. This order was then tested during a pilot study. The sentences were recorded by a native speaker of French on a digital recording and presented to the participants through headphones. The participants’ only task was to repeat the sentences exactly as they heard them, even though they did not sound right to them.

In the replication task, the participants were presented with 15 pairs of sentences, from the easiest to the hardest, according to Gaux and Gombert's (Reference Gaux and Gombert1999a) criterion, that of the level of similarity between the first and the second sentence of the pairs: as the sentences become less similar in their construction, it becomes harder to provide the correct answer. Pairs of sentences are considered to be similar when the target element is located in the same part of each sentence, as illustrated in examples (1) and (2) below. In each pair, the first sentence contained an error. The participants were asked to reproduce, in the second sentence, the error presented in the first one. Illustrated here is an item targeting the passive voice in French:

(1) *Le poème est récité lentement les enfants.

“*The poem is slowly recited the children.”

(2) Le ballon est lancé rapidement par le garçon.

“The ball is quickly thrown by the boy.”

In this specific case, the participants had to reproduce in the correct sentence (2) the same type of error as the one encountered in the incorrect sentence (1), which was the omission of the preposition par “by” in the passive formation. The expected response was *Le ballon est lancé rapidement le garçon “*The ball is thrown quickly the boy”. In this task, four items targeted the placement of clitic pronouns and one item targeted the choice and the placement of a clitic pronoun. Five items targeted relative clause constructions, of which two targeted the subordinate clause placement, two targeted the choice of the relative pronoun and one targeted the relative pronoun placement. Three items targeted comparatives. In one of them, que was replaced by de. In another one, the comparative adverb was misplaced. Finally, there was one in which que was omitted. Two items targeted causative constructions in which the infinitive verb was misplaced. Lastly, two items targeted passive constructions: one in which the error was related to the constituent order and the other, in which the preposition par was omitted in the object of the agent.

The sentences were presented on a visual support and read to the participants (to control for reading ability) on an audio recording. The participants had to answer orally.

Reading comprehension

In order to assess reading comprehension skills, we used a reading task in which the participants had to read a text and to answer, without access to the text, a series of 12 questions (see Foucambert, Reference Foucambert2003, Reference Foucambert, Durand, Habert and Laks2008, Reference Foucambert2009, for additional details about the reading task). The text in French (number of words = 589) and the text in Portuguese (number of words = 564) were comparable in terms of lexical and syntactic level of difficulty. For lexical difficulty, the word frequency analyses were done using Frantext (New, Pailler, Brysbeart & Ferrand, Reference New, Pallier, Brysbaert and Ferrand2004) (M = 4.67, SD = 2.59) and Portext (Maciel, Reference Maciel1990) (M = 4.79, SD = 2.57). No statistical difference between both versions in terms of lexical difficulty could be observed, t(1151) = 0.84; p < .6 (two-tailed). For syntactic complexity, the number of sentences and words per sentences were calculated for both French (number of sentences = 39, M = 13.61, SD = 9.12) and Portuguese (number of sentences = 42, M = 13.93, SD = 6.03). Again, no statistical difference could be observed between the two versions, t(79) = 1.53; p < .87 (two-tailed). The questions were all close-ended questions tapping different levels of inference (Foucambert, Reference Foucambert2003). According to Denhiere and Baudet (Reference Denhiere and Baudet1992) and Fayol (Reference Fayol1992), it is essential to measure reading comprehension through three distinct elements, text surface structure, propositional text base and the mental (or situational) model generated by the reader (see Johnson-Laird, Reference Johnson-Laird1983; Kintsch, Reference Kintsch1988; Kintsch, Welsch, Schmalhofer & Zimmy, Reference Kintsch, Welsch, Schmalhofer and Zimny1990; van Dijk & Kintsch, Reference van Dijk and Kintsch1983). One-third of the questions targeted recognition of lexical and syntactic elements which were explicitly present in the text. Another one-third of the questions targeted the evaluation of inferences produced by the participants on the basis of elements that were not explicitly present in the text. The rest of the questions assessed the coherence of the information generated by the participants on the basis of the link between the first two levels of elements and their own general knowledge.

Language proficiency

To get a measure of language proficiency in French, the participants performed version B (since version A was demonstrated to overestimate language proficiency for Quebecois according to Godard & Labelle, Reference Godard and Labelle1995) of the Échelle de vocabulaire en images Peabody (EVIP; Dunn, Theriault-Whalen & Dunn, Reference Dunn, Theriault-Whalen and Dunn1993), a standardized French Canadian translation of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – Revised (PPTV–R; Dunn & Dunn, Reference Dunn and Dunn1981). The PPVT is used by researchers to measure “the degree of balance between two languages and as an index of the comparability of the bilingual children's language in each language to those of monolinguals” (Bialystok, Reference Bialystok2001a, p. 63). For practical reasons, the group administration procedure proposed by Bourque Richard (Reference Bourque Richard1998) was used. According to the age group of the participants, the baseline (first item of the series) was identified. Then, from this baseline a total of 41, items were presented to each age group. The words were recorded by a native speaker on audio materials, and the participants had the copy of the images in a booklet. Four images, corresponding to one item, were presented on each page, and the participants were told to cross the image corresponding to the word. As for the Portuguese measure, version A of the PPVT–R (Dunn & Dunn, Reference Dunn and Dunn1981) was translated into Portuguese and presented through the same group procedure.

Procedure

We first piloted the tasks (MSA, French and Portuguese versions of the reading comprehension tasks, and the Portuguese version of the PPVT) among a group of children presenting the same characteristics as our target population (i.e., same age, same SES, etc.). This allowed us to verify whether there were problems with the items, the instruction or the procedure, and to verify our item ranking for the repetition and replication tasks.

Then, for the actual study, all FSC were met at their regular school during school hours. Language proficiency and reading comprehension tasks were administered by a research assistant in class. For the language proficiency task, two practice items were presented to the participants before completion. Later the same day or the following day, the participants were met individually by a research assistant to answer the background information questionnaire and to perform the two metasyntactic tasks: first the sentence repetition task, and then the sentence replication task. In both cases, two practice items were also presented before completing the task. Feedback was provided when needed. All individual testing was digitally recorded for further analysis. It was decided to put an end to the administration of the task after four consecutive missed items (e.g., Roman, Kirby, Parrila, Wade-Wooley & Deacon, Reference Roman, Kirby, Parrila, Wade-Woolley and Deacon2008), in order not to discourage the participants.

As for the PHC that were studying at the same school as the FSC, they followed the same procedure for the tasks in French, and were met once again a week later to perform the Portuguese version of the tasks, using the same procedure, that is that they did the language proficiency and reading comprehension tasks in group. The remaining PHC were met at their Portuguese Saturday school on two consecutive Saturdays, performing the French version of tasks on the first one, and the Portuguese versions, on the second one. In summary, the PHC children were administered all versions of the reading and language proficiency tasks in addition to the French MSA tasks; and the FSC children were administered the French versions only.

Coding procedures

For the repetition task, one point was allowed for each item (n = 20) if the target (the syntactic error) was correctly repeated. Errors in the repetition of the rest of the sentence (e.g., missing adjective (grosse “big”) in *La grosse tortue de mer nage plus lentement le dauphin “*The big sea turtle swims slower the dolphin”) were not considered since in this particular example the target error was related to the omission of que after lentement. For the replication task, one point was allowed for each right answer (correct production of the second sentence containing the same type of error found in the first sentence), for a maximum score of 15 points. These two tasks were coded by two independent raters. The interrater coefficient of reliability scores for the repetition task in French is .993. For the replication task, the interrater coefficient reliability score for the French version is .997. As for the reading comprehension and the language proficiency and tasks, one point was given for each correct answer (total score for reading comprehension = 12; total score for language proficiency = 41).

Data analyses

The Statistica® v.7.0 general linear models module was used for all statistical testing. In order to answer the research question, traditional ANCOVAs were used.Footnote 1 The results for the testing of ANCOVA assumptions, namely the normality of data distribution, normality of residuals and homogeneity of variances, were non-significant for all studied models.

Results

Our results are presented in three sections. We first present a brief overview of the variables obtained. We will then successively characterize our participants’ results for the two MSA tasks, i.e., the repetition and replication tasks.

Preliminary analyses

Table 1 presents the reliability scores and results of the normality test for each of the variables. As can be seen, we reached acceptable levels of reliability (Larson-Hall, Reference Larson-Hall2010). Overall, our variables were correctly distributed, except for the replication and the language proficiency in French, and the reading comprehension in Portuguese tasks.

Table 1. Reliability scores and normality of distribution for all tasks (raw data).

We corrected the first two distributions (Howell, Reference Howell1998) by applying in the first case the formula ![]() $v_N = \sqrt {x + 0.5}$, and in the second case, vN=x 2. These modifications normalized the distribution since the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test conducted on the results obtained for each variable did not allow to observe any significant p-values (dLanguage proficiency in French = 0.16, p > .2; dReplication in French = 0.15, p > .2). It should be noted that these corrections do not modify the observed phenomena. We were unable to sufficiently correct the reading comprehension in Portuguese distribution to normalize it according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test results. Thus, the distribution of the data remained not normally distributed for the subsequent statistical analyses.

$v_N = \sqrt {x + 0.5}$, and in the second case, vN=x 2. These modifications normalized the distribution since the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test conducted on the results obtained for each variable did not allow to observe any significant p-values (dLanguage proficiency in French = 0.16, p > .2; dReplication in French = 0.15, p > .2). It should be noted that these corrections do not modify the observed phenomena. We were unable to sufficiently correct the reading comprehension in Portuguese distribution to normalize it according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test results. Thus, the distribution of the data remained not normally distributed for the subsequent statistical analyses.

Table 2 presents the results obtained on the language tasks in French and in Portuguese. In every case, the scores obtained by the FSC group are higher than those obtained by the PHC. However, none of these differences are statistically significant, indicating that our groups are comparable both in reading comprehension (F(1,42) = 0.23; p < .7) and language proficiency (F(1,42) = 1.39; p < .3). It should be noted here a ceiling effect can be observed for both the PCH and FSC participants. As can also be seen, although our PHC participants obtained a fairly high score on the Portuguese version of the language proficiency task, they obtained an even higher score on the French version. Comparisons show that they obtained significantly higher scores on the French versions of the language proficiency (t = 8.121; p = .00, d = –1.55). Also the PHC participants scored slightly lower in French than in Portuguese for the reading comprehension tasks. Nevertheless, a statistically significant difference was not observed between their scores in French and in Portuguese for reading comprehension (t = –0.466; p = n.s.).

Table 2. Results on language tasks for each group of participants.

FSC = French-L1-speaking children; PHC = Portuguese heritage language children; max reading comprehension = 12; max language proficiency = 41

To answer our research question, we assigned the subjects to three different groups according to the scores on the reading comprehension task. Participants with a score greater than the third quartile were considered as a stronger reader group (n = 12), those with a score smaller than the first quartile were considered as weaker readers (n = 12), and those between those two boundaries were assigned to the average reader group (n = 20).

Repetition task

Results for the repetition task presented in Table 3 (first line of results) and in Figure 2 (grey bars) show a constant increase of the scores obtained on the repetition task according to the level of reading comprehension: the better the reading comprehension the higher the repetition score.

Table 3. Means (and standard errors) for percentages of repetitions (rep) and replications (repl) according to language group and reading skills.

FSC = French-L1-speaking children; PHC = Portuguese heritage language children

Figure 2. Mean percentages (computed for covariate at mean) of success according to MSA task and reading comprehension for all participants. Error bar represents 95% confidence intervals.

The results were submitted to a Group (2: PHC vs. FSC) × Reading Comprehension (3: High, Average, Low) two-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA–GLM), in which Language Proficiency in French was a covariate. The procedure yielded a significant main effect due to Reading Skill and Language Proficiency but not a significant effect of Group nor an interaction effect between Group and Reading Skill (Reading Skill: F(2,37) = 3.46, p < .05, η2p=.15; Language Proficiency: F(1,37) = 7.04, p < .02, η2p=.16; Group: F(1,37) = 3.18, p < .09; Group × Reading Skills: F(2,37) = 1.51, p < .3).Footnote 2 Fisher's LSD post hoc analysis revealed that all groups of readers differed significantly from one another (all ps < .03), and this applied to both the PHC and FSC groups.

As for Language Proficiency, the GLM module indicates the regression parameter coefficients (param = 2.57, t = 2.60, p <0 .02; β = 0.35) and shows that each additional point obtained in the language proficiency task corresponds to an elevation of 2.6% on the repetition task. Partial eta-squares for these two variables indicate similar relatively important effect size (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988).

Replication task

Results for the replication task are also presented in Table 3 and in Figure 2 (black bar). The results obtained on the replication task were submitted to a similar 2 × 3 ANCOVA–GLM where Group (2: PHC vs. FSC) and Reading Comprehension (3: High, Average, Low) were the categorical variables and Language Proficiency in French the covariate.

The procedure yielded only a very significant main effect due to Reading Skill (Reading Comprehension: F(2,37) = 6.18, p < .005, η2p=.25; Language Proficiency: F(1,37) = 0.33, p < .6; Group: F(1,37) = 0.99, p < .32; Group × Reading Comprehension: F(2,37) = 0.27, p < .8). This time, Fisher's LSD post hoc analysis revealed that the better readers significantly differed from the average readers (p < .003) and from the poorer readers (p < .001) by obtaining better results in each case.

Once more, when controlling for language level effects (reading skill and language proficiency), none of the two language groups seems to be significantly associated to better results on the replication task. However, when other effects are controlled, results reveal a strong link between the reading comprehension task and the replication task (η2p=.25): this effect is borne by stronger readers who are different from the other two categories of readers (Figure 2, black bars).

Discussion

Our objective was to verify whether PHC with reading comprehension skills and language proficiency in French comparable to French monolingual children would obtain better scores on MSA tasks believed to call for higher levels of control, that is, a repetition task and a replication task. Prior studies (e.g., Da Fontoura & Siegel, Reference Da Fontoura and Siegel1995; Lesaux & Siegel, Reference Lesaux and Siegel2003; Lipka et al., Reference Lipka, Siegel and Vukovic2005) found an advantage for monolinguals on an oral cloze, a MSA task that requires analysis of linguistic knowledge but only little attentional control. Since some heritage language children have been observed to have an advantage over monolinguals on tasks requiring a higher level of attentional control (see Bialystok, Reference Bialystok2001a), we had hypothesized that our heritage language participants (PHC) with comparable language proficiency and reading comprehension skills in French (the majority language) would obtained better scores than the French monolingual participants (FSC) on both MSA tasks (i.e., repetition and replication tasks). However, our analyses revealed no significant difference between the results obtained on any of the MSA tasks by the two groups of participants. Therefore, our hypothesis is not supported by our results.

This can certainly be explained by our PHC participants’ level of competency in both languages. Recall that the heritage language participants obtained comparable scores in both the French and Portuguese versions of the reading task and although they obtained a fairly high score at the language proficiency task in Portuguese, their result in French was statistically higher. However, it appears that the French version of the language proficiency task was too easy for both groups of participants, as can be seen by the ceiling effect in the scores. Therefore, on the basis of the scores the PHC participants obtained for each version of the reading and language proficiency tasks, we thought that they would demonstrate the “bilingual advantage” at the MSA tasks. According to the conclusions of previous studies investigating metalinguistic task demand among heritage language children (e.g., Cromdal, Reference Cromdal1999; Ricciardelli, Reference Ricciardelli1992), children with higher levels of language competency in both languages should have an advantage over the monolinguals on tasks requiring higher levels of control, such as the repetition of ungrammatical sentences and the replication of error used in the present study. In their study examining the relationship between bilingualism and metalinguistic ability, Galambos & Hakuta (Reference Galambos and Hakuta1988) emphasized that a “bilingual advantage” on their tasks, which measured MSA, could be seen when the level of bilingualism of the children was high enough (p. 159); i.e. when the level of language proficiency reached a certain level. The same idea is discussed in Carslon and Meltzoff (Reference Carlson and Meltzoff2008), who suggest that “early and intensive exposure to, and mastery of more than one language may be necessary for a benefit in aspects of executive function to manifest itself” (p. 294). However, what is meant by “higher levels of language proficiency in both languages” is not specified anywhere. It might therefore be that in our study, although our participants demonstrated rather high levels of language command in both the minority and majority languages as measured by the reading and language proficiency tasks, it might still not have been high enough. In this regard, it should be kept in mind that the Portuguese version of the PPVT was used to measure language proficiency in Portuguese, unlike the French version that is standardized, was a translation done for the purpose of the present study. The use of another instrument might have led to other results regarding our PHC level of language competency in both languages. In any case, our PHC participants’ level of competency in both languages was high enough to prevent them from demonstrating deficits in their MSA, as was observed in previous studies carried out among heritage language children (e.g., Da Fontoura & Siegel, Reference Da Fontoura and Siegel1995; Lipka et al., Reference Lipka, Siegel and Vukovic2005).

Another interesting result in our study is the difference in performance on the two MSA tasks for all participants. The variance between the two tasks is linked, in our study, to two different sets of skills in French: language proficiency and reading comprehension. For the repetition task, it is possible to observe a similar relative weight of both language proficiency and reading comprehension, whereas for the replication task only reading comprehension is significant with a strong effect size (η2p=.25) (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988). Our results thus lend support to the claim that, on the one hand, MSA is associated with reading comprehension not only in L1 and in early stages of development in L2, but also in more advanced stages of reading comprehension in L2 (as measured by both the French and the Portuguese versions of the reading comprehension task). On the other hand, our results also lend support to the claim that, to some extent, the repetition and replication tasks are distinct measures of MSA (Gaux & Gombert, Reference Gaux and Gombert1999b; Simard & Fortier, Reference Simard, Fortier and Han2007). As mentioned earlier, metalinguistic tasks can be examined according to the factors that interact with performance. In the repetition task, participants had to rely on their language knowledge to be able to remember the words in the sentences that were read to them. Their reading comprehension skills also certainly helped them being able to repeat the sentences as they heard them, since reading comprehension is associated with syntactic knowledge in both L1 (e.g., Foucambert, Reference Foucambert, Durand, Habert and Laks2008; Greenberg, Koriat & Velluntino, Reference Greenberg, Koriat and Vellutino1998; Saint-Aubin, Reference Saint-Aubin2005) and L2 (e.g., Gaux & Gombert, Reference Gaux and Gombert1999; Siegel & Ryan, Reference Siegel and Ryan1988). It should be noted that, according to Gaux and Gombert (Reference Gaux and Gombert1999b), performance on a repetition task is influenced by factors like language as well as vocabulary knowledge. In the replication task, on the other hand, the participants were provided with a visual aid they could rely on, freeing their memory and allowing them to focus specifically on the task. In this regard, future research might want to integrate a verbal working memory measure into the experimental design as a way to control for individual variation (see Daneman & Carpenter, Reference Daneman and Carpenter1980; Waters & Caplan, Reference Waters and Caplan1996, for a discussion on the topic). Although some studies on metasyntactic ability report working memory measures, these scores are not used to control for variations (e.g., Da Fontoura & Siegel, Reference Da Fontoura and Siegel1995).

One final word about the difference between the two MSA tasks should be said. As in Nocus & Gombert (Reference Nocus and Gombert1997), the replication task in our study led to results substantially lower than the other MSA task (i.e., repetition task). When Nocus & Gombert (Reference Nocus and Gombert1997) used it in L1 among children, they observed a floor effect, especially with the syntactic features, saying that morphosyntactic elements were easier for their participants. Very similarly, Lefrançois and Armand (Reference Lefrançois and Armand2003) observed a floor effect and decided to exclude from their study the data obtained from the replication task saying that “it may be too big of a challenge for 9 to 11 children in L2” (p. 229). It should be noted here that their L2 participants had just started being exposed to the L2. We believe the replication task is certainly the most challenging MSA task, and this probably in both L1 and L2. We also believe that it allows the observation of more advanced levels of language analysis and attentional control. However, the task should be further investigated in order to really understand the strategies used by participants to come up with their answers and to have a better measure of the levels of both analysis and attentional control involved. For instance, an analysis of verbal protocols gathered as the participants complete the task would certainly provide valuable information in this regard. Future research investigating MSA and reading skills might also want to look at the type of task used to measure reading skills. All previous studies used comprehension questions. We believe that another measure might have led to different results. According to Gombert et al. (Reference Gombert, Martinot and Nocus1996), MSA appears to help reading comprehension by contributing to the automatic syntactic treatment of information. This automatic syntactic treatment is supposed to facilitate reading comprehension. Therefore, it would be interesting to verify, using an online measure (e.g., reaction time, event-related potential), whether heritage and monolingual children showing similar MSA would have the same reading speed.

Conclusion

The objective of the present study was to verify whether heritage language children with higher levels of language proficiency would obtain better scores on MSA tasks than the majority-language-speaking children with comparable reading comprehension skills and language proficiency in the majority language. Even though we expected that our PHC would benefit from the advantage bilinguals have over monolinguals at metalinguistic tasks demanding higher levels of attentional control, they did not outperform the majority-language-speaking children. However, they did not demonstrate any MSA deficits either. In this, our results are different than those of Da Fontoura and Siegel (Reference Da Fontoura and Siegel1995), Jongejan et al. (Reference Jongejan, Verhoeven and Siegel2007) and Lesaux and Siegel (Reference Lesaux and Siegel2003), to name only a few. We tried to explain our results by mentioning that to observe any “bilingual advantage”, the level of language competency in both languages must be high enough (Galambos & Hakuta, Reference Galambos and Hakuta1988). Nevertheless, it is unclear what “high enough” really is. Future research should try to formalize what “high language competency in both the majority and minority language” is. We also think that aspects such as the instruments to measure reading competency as well as individual differences such as verbal working memory should systematically be examined. Finally, future research should look at different parings of languages in order to verify whether the same results would be obtained among participants from languages not as typologically similar as French and Portuguese.

Appendix. Items in metasyntactic ability tasks

Repetition task

Target items are in italics.

I. Le lion est le roi des animaux. (entrainement)

II. Mon frère adore aux jeux vidéos jouer. (entrainement)

1. Le film quoi jouait à la télévision est terminé.

2. Ton ami veut l'inviter à sa fête la semaine prochaine.

3. La grosse tortue de mer nage plus lentement le dauphin.

4. Ta sœur veut parler lui de son projet en arts plastiques.

5. Le jeu vidéo que je veux avoir pour Noël coûte très cher.

6. Mon grand-père a notre chien laissé courir dans la neige.

7. Une histoire a été lue par le professeur dans la classe.

8. Le gâteau qui je veux manger à la fête goûte très bon.

9. Les cadeaux de Noël seront sous le sapin placés.

10. Les élèves de quatrième sont plus grands que les élèves de deuxième.

11. Le directeur punit le garçon qui a fait un graffiti.

12. La maison de briques est plus solide de la maison de bois.

13. Nous ferons le spectacle dans la pièce que Max a repeinte.

14. Lucie a reçu la carte de laquelle ont dessiné ses amis.

15. Simon ne peut pas nous donner des boîtes vides pour notre projet.

16. Le représentant de la classe a nommé enfin été.

17. J'ai écrit un texte plus long que celui de ma petite sœur.

18. La voiture de mon père a finalement été réparée.

19. Il nous a raconté une histoire dont la fin était très triste.

20. J'ai fait un château plus haut celui de mes amis.

21. Le professeur a fait écrire un journal à ses élèves.

22. Elle m'a donné un chandail qui la couleur est très jolie.

23. La bonne musique a fait les danser plus tard que prévu.

24. Vous devez me les envoyer avant la fin de la journée.

25. Il ne faut pas faire manger des choses sucrées aux chiens.

26. Je pense les vous chanter pendant de concert de l'école.

27. Le personnage que mon frère a fait le dessin vit dans une forêt.

28. Il te les a fait couper trop court.

29. Le garçon dont le dessin a gagné le prix est de notre école.

30. Le bateau sur qui nous naviguons approche du quai.

31. Le très fort vent de la nuit dernière l'a fait tomber à terre.

32. Maria n'a pas pensé te faire les lire immédiatement.

33. Le projet sur lequel nous travaillons porte sur la pollution.

34. Les visiteurs du zoo ont vu se bagarrer les deux lions.

35. Le roi a fait les surveiller par ses chevaliers.

36. Le film n'est pas aussi intéressant je l'avais pensé.

37. Son père le laisse toujours nous accompagner à la piscine.

38. Les employés de l'animalerie naître ont vu les chatons.

39. Il y a moins de neige que la météo l'annonçait.

40. La tête du dinosaure est plus grosse de nous l'imaginions.

Replication task

The sentences in bold contain an error that must be identified and reproduced in the second sentence of each pair.

Items de pratique

I. Professeur mon est le plus gentil de l'école.

Ma sœur prend des cours de piano.

II. J'aimerais donner un bisou mon ourson.

J'ai utilisé la bicyclette de ma sœur.

Items de la tâche

1. Samuel donne lui la bicyclette rouge.

Sophie lui propose d'aller à la plage.

2. Le chandail est en laine que tu portes.

Le repas que vous mangez semble délicieux.

3. L'oiseau vole aussi haut de la maison.

Ce foulard est aussi doux qu'un chaton.

4. Cette belle surprise m'a fait ma peine oublier.

La grande chaleur m'a fait boire de l'eau.

5. Le texte lu est par les élèves avec intérêt.

Le gâteau est mangé avec appétit par les enfants.

6. Elle offre leur de rester à souper.

Je vous propose une belle sortie au cinéma.

7. Le poème est récité joliment les enfants.

Le ballon est lancé rapidement par le garçon.

8. Nous sommes de garçons que de filles autant.

J'ai cueilli autant de fleurs qu'elle.

9. Les skis se vendent très cher dont je rêve.

J'ai joint une équipe dont le capitaine est génial.

10. Réussir est moins difficile tu ne l'avais pensé.

Son travail est plus long que celui que j'ai fait.

11. Mon père m'a offert en pour mon anniversaire.

Tu le lui as conseillé pour son projet.

12. L'ami qui j'aimerais inviter chez moi n'est pas disponible.

Il m'a fait découvrir un auteur que je trouve intéressant.

13. J'ai fait acheter toi deux biscuits pour notre collation.

Il leur a fait corriger les erreurs dans ma dictée.

14. La fille quoi j'ai vue au magasin est dans ma classe.

J'espère que tu as reçu la lettre que je t'ai envoyée.

15. L'ami je jouais aux cartes avec qui est très rusé.

Le tableau sur lequel l'enseignante écrit est vert.