In spring 1911, the daily paper Excelsior published a series of articles detailing Beethoven's fate in Paris. The sculpture under consideration was by M. de Charmoy, and was to be erected at Ranelagh on the western outskirts of the city (see Figure 1). The statue met with an unfortunate end at the hands of the Conseil Municipal. Tired of the ceaseless parade of statuary ‘invading’ Paris, the committee terminated plans for the monument in the name of urban aesthetics. The musical greatness of ‘le Père des Neuf-symphonies’ could not override the threat of statuomanie, in full efflorescence since the advent of the Third Republic. Public intellectuals and snippy columnists alike ranted about the surfeit of statues cluttering the city's expansive, Haussmannized boulevards. An editorial in Gil Blas entitled ‘La question des statues’ lauded the government official in charge of such projects, one Maurice Le Corbellier, for taking a categorical position: ‘It consists, purely and simply, of refusing all new locations marked for the erection of statues in the interior of Paris.’Footnote 1 In his Économie esthétique, M. Maignan suggested a more moderate solution. No statue should be erected, he advised, unless the topography of the location appeared to call for one.Footnote 2 A slim pamphlet contained the most vehement protest. Gustave Pessard's Statuomanie parisienne provided an astonishing tally of the new monuments in Paris: the number of statues raised between 1870 and 1911 was six times that of statues erected in the preceding 70 years.Footnote 3 ‘The way things are going,’ Pessard warned,

we run the risk of seeing before long not only the Luxembourg, the Parc Monceau and the Cours la Reine, but all the squares of Paris including the Champs-Élysées and the Tuileries, and even the smallest empty spaces left to us, invaded by a gaggle of unknown nobles, garbed in frock coats and pantaloons, with bizarre accessories that verge on the ridiculous, shock our eyes, blemish and sadden the aesthetics of our promenades, and transform our gardens into veritable cemeteries.Footnote 4

Rhetorical histrionics aside, Pessard's underlying claims were sound, particularly about the types of new statues being disseminated. Instead of presenting abstracted, ancient heroes, these monuments were didactic: Louis Pasteur standing for ‘Scientific Progress’, for example, and Victor Hugo for ‘Liberty’.Footnote 5 Charmoy's Beethoven, with its rippling torso and Hellenic grandeur, might have met the main administrative requirement for new public statuary (the subject must have been dead for ten years), but it ultimately proved incompatible with the prevailing political winds.

Figure 1. Charmoy sculpture of Beethoven. Reproduced, courtesy of Répertoire Internationale de la Presse Musicale, from Musica, 4/32 (May 1905), 80.

As Maurice Agulhon notes, ‘The Third Republic came to appear in retrospect the most statuomaniacal regime of all.’Footnote 6 Republicanism had a spotty history in France. Statues offered it a simple, silent ratification. By their mere presence, these stone representations of accomplished men embodied the laic virtues officials hoped to promote. While not an explicit governmental programme, statuomanie had a public educational function akin to other, more obvious civic reforms. Michael D. Garval has described a ‘literary “statuemania”’ that gripped turn-of-the-century French society, a rêve de pierre envisioning ‘a seamless fusion of writer, work, and monument. […] There prevailed this curious double vision, almost a collective schizophrenia, with a keen awareness of the vagaries of change, existing alongside an equally powerful dream of purposefulness, solidity, and immutability.’Footnote 7 Garval suggests that this commemorative impulse had a talismanic aspect, protecting against contemporaneous sociopolitical instabilities. The undeniable multifariousness of aesthetic modernism, along with ever more precarious politics, would ultimately defeat this rosy monumentalism.

In the same year as Pessard's jeremiad, ballet engaged in its own statuomanie, with two works that drew upon Greek artefacts for inspiration: Ravel and Fokine's Daphnis et Chloé and Debussy and Nijinsky's L'après-midi d'un faune. Just as the Third Republic sought to rid itself of the decadence of Second Empire excess, so too were choreographers searching for alternatives to the empty, overwrought gestures of classical ballet. Ancient Greece, full of stark lines and simple garb, seemed a fruitful source of inspiration. Unlike the literary statuomania that Garval observes, the balletic version was distinct both genetically and aesthetically. Not that dance was now turning for the first time to the animation of statuary for inspiration. Such a trope stretches back centuries, and includes Rameau's Pygmalion and Beethoven's Die Geschöpfe des Prometheus, among others.Footnote 8 In Music Speaks, Daniel Albright posits that ‘the statue that moves is a kind of totem, not just for ballet, but for all experiments at the boundaries between one artistic medium and another – what might be called Zwischenkunst, or interart’.Footnote 9 I argue that the statuomaniacal impulse of the Third Republic – intertwined with, even as it sought distance from, the Second Empire – and the statuarial inspiration of Daphnis and L'après-midi enact the boundary-crossing that Albright theorizes, demonstrating in this statuomanie a peculiarly belle époque aesthetics and politics.

This article situates Daphnis and L'après-midi within three related frameworks: first, the disputes over urban statuary with which we began; secondly, shifting conceptions of time's ontologies; and thirdly, developments in technologies of observation that were themselves implicated in the effort to animate other, older statuary. I have chosen these frameworks in order to suggest that, despite their contemporaneity, these ballets bookend a shifting notion of how bodies could, and should, move. I argue that the dancing body as staged in L'après-midi is qualitatively different from that of Daphnis, and that this difference points to the ways in which belle époque optical modalities responded to critical shifts in ways of seeing. This juxtaposition also offers scholars and historians new ways of critically seeing these works. Instead of focusing on the scandale d'occasion of L'après-midi's première, or bypassing these ballets entirely in favour of the following year's Nijinskian and Stravinskian balletic tribulations, I hope to demonstrate in this article that Daphnis and L'après-midi are crucial moments in a consideration of belle époque spectatorial practices, as their shared classical topos throws optical shifts into sharp relief. In both ballets, the animation of statuary, at once retrospective and prospective, confronts aesthetic and political issues endemic to art of this period and had a lasting influence on the legacies of Ravel and Debussy.

Greek life

During the first decades of the twentieth century, dance was strongly associated with antiquities through the work of Isadora Duncan. In 1903, she and her brother Raymond (also a dancer) spent a year in Greece with the rest of her family, interrupting their fledgling dance careers in order to immerse themselves in the culture of Hellenic antiquity. They retraced Ulysses’ journey in Homer's Odyssey, draped in the diaphanous tunics that would become Isadora's signature.Footnote 10 In her memoirs, she recalled her intention that ‘Clan Duncan should remain in Athens eternally, and there build a temple that should be characteristic of us’. Although these plans went unrealized, Greece lingered in Duncan's memory and art. She later visited London, again with Raymond, where they together devoted themselves to the study of ancient artefacts:

We bought some cot beds for the studio and hired a piano, but we spent most of our time in the British Museum, where Raymond made sketches of all the Greek vases and bas-reliefs, and I tried to express them to whatever music seemed to me to be in harmony with the rhythms of the feet and the Dionysiac set of the head, and the tossing of the thyrsis.Footnote 11

In his history Le ballet contemporain, the critic Vladimir Svetlov discussed Duncan and her career at length, calling her a ‘statue come to life, an embodiment of the myth of Galatea’; he claimed that ‘her dancing evokes for us, in all of its varied colours, scenes of life in ancient Greece’.Footnote 12 But as Anthony Sheppard has noted, Duncan's Greece was her own invention: a general stimulus, rather than an archetype to emulate.Footnote 13 Although Daphnis and L'après-midi extended this interest in antiquity, they diverged from Duncan's Hellenism in important ways. Both Fokine and Nijinsky, each in his own way, adopted specific ancient artefacts as models for their respective choreographic projects.

The inception of the Daphnis project predated that of L'après-midi by several years. Diaghilev himself had broached the topic to Ravel in 1909, the first year in which he presented ballets in Paris; but Fokine's interest in Longus's romance had been kindled years earlier, even before he arrived in France.Footnote 14 Inspired by the Russian symbolist Dmitriy Merezhkovsky's 1895 translation of the work, Fokine envisioned a ballet that avoided artificial and ahistorical stylization in favour of something more grounded and accurate, in keeping with the principles of the Mir iskusstva collective, several of whose members would be Fokine's future collaborators. In his memoirs, he described the specific archaisms that shaped Daphnis's choreography, reflecting his faith that such gestural archaeology would actually enhance the fluid ‘naturalism’ of the movements:

The dances of shepherds and shepherdesses, bacchantes, warriors, Chloe, and Daphnis were based on the Greek plastique of the period of Greece prime. In the dances of Darkon and the nymphs I used more archaic poses. The nymphs were less human than the other mortals. Their positions were almost stylized and exclusively in profile. Darkon was supposed to convey the impression of being rough and clumsy in contrast to the agile and graceful Daphnis with whom he decided to compete in dancing. That is why, for the composition of Darkon's part, I utilized more angular positions. Of course all the dancers were either barefoot or in sandals.Footnote 15

As Lynn Garafola has emphasized, naturalism, now a maligned concept, was during the pre-war period ‘a galvanizing imaginative force’ that functioned symbiotically with the earnest antiquarianism Fokine was attempting.Footnote 16 The bacchanale finale, for example, with its mutable groupings of the corps de ballet, resembled a flickering bas-relief, especially in the ‘intertwined arms’ of the dancers.Footnote 17Daphnis's choreography thus represented the ideas of an intellectual constellation that had its inception in Russia, but achieved realization only in Paris.

In contrast to Fokine's preoccupation with actual antiquarianism, Ravel's score was in his own words ‘a vast musical fresco, less concerned with archaism than with faithfulness to the Greece of my dreams, which is similar to that imagined and painted by French artists at the end of the eighteenth century’.Footnote 18 The composer's nostalgic conception of the ballet's historical setting was exactly the sort of thing Fokine wished to supersede with accurate gestural recreation. This tension between Fokine's desire for purification and Ravel's for hazy aestheticism amounted to a collision of two archaic visions, bringing questions of timeliness and synthesis to a head. Fokine had actually enquired of his collaborator whether it might be conceivable to recreate ‘authentic’ Greek music. The composer quickly disabused him of that possibility. Instead, the score of Daphnis deploys Ravel's customary sensuality, which critics either lauded or loathed. Émile Vuillermoz fell into the first camp, writing of the ‘spontaneity of the harmonic language, the freshness of these new inventions, the cohesion of the orchestra, whose remarkable sonorousness never appears effortful or polemical – all pointing to a strong and successful artistry’.Footnote 19 It was a ‘complete synthesis’ of materials.Footnote 20 Others, however, found the music perplexing. Le gaulois mulled over its place in the history of music. Was it ‘the music of tomorrow’? Or at least of ‘a new school’? Not venturing an answer, the paper merely concluded that the work was ‘curious’ and ‘disconcerting’.Footnote 21 The most specific critique focused on the work's alleged lack of rhythmic vitality. Writing for Le temps, Pierre Lalo published the baldest accusation: ‘It is missing the most important quality of ballet music: rhythm.’Footnote 22 Arthur Pougin at Le ménestrel agreed, though the question of rhythm appeared only at the end of a bewildering admixture of anaemic praise and vague complaints.Footnote 23 Gustave Samazeuilh was more circumspect, admiring the vigour of the pirate music and the finale while simultaneously wishing for greater ‘rhythmic contrast’ elsewhere.Footnote 24 These critiques in fact echoed Fokine's own misgivings that Ravel's score lacked a certain ‘virility’ except in the sections Samazeuilh identified in his article.

Complaints such as these obscure the fact that, at certain moments in Ravel's indolent score, music directly inspires the choreography and at times actually replaces movement. Dorcon's danse grotesque is an example of the first case. With its incessant duple metre, heavily accented on the first beat, the opening timpani rhythm on repeated Es recalls nothing so much as relentless barefoot stomping.Footnote 25 It becomes a sort of vestigial aural marker, on which Fokine could then base his gestures. In his extended review of Daphnis and L'après-midi for Comoedia illustré, Henri Gauthier-Villars described the number, as well as Daphnis's fleet response. His collapsing of rhythm into an audiovisual mélange is striking, especially given the accusations critics had levelled at the music. ‘The danse grotesque of the cowherd Dorcon,’ he writes, ‘punctuated by Bolm with truly remarkable passion, vigour and metrical precision, is full of innovative and pleasing gestures; the poetic dance of Daphnis where Nijinsky's bare arms spill out of his open tunic […] will be one of the most artistic inventions of this astonishing creator of visual rhythms.’Footnote 26 Though lacking the kind of insistent rhythmic motifs that help to propel movement in conventional ballet music, Daphnis presented an alternative in this particular moment with the timpani: illustrative rhythmic gestures that yielded corresponding visual translation. Much as the choreography was inspired by the animation of statuary, Ravel's music provided an aural animating force that intensified the relationship between music and gesture from complementation to synthesis.

While many productions of the time were deemed ‘synthetic’ (purporting a harmonization of music and dance that enhanced rather than disrupted or demeaned), Daphnis attempted something distinct from dances by Duncan or Loïe Fuller, among others. Davinia Caddy has recently explored the ‘representational conundrum’ music and dance at times enacted during the belle époque, using Fuller as one of her case studies. Fêted for her whirling performances with copious diaphanous silks, Fuller, in Caddy's summation,

discarded what she regarded as a naïve theory of mimesis, based on both the objective imitation of fixed points of reference and the cultural authority of the author. Unseating this authority, she promoted the agency of the observer (the spectator inside the theatre) and that of herself, as observer of music; and she represented this music in all its imagined metaphoricity – its infinite powers of suggestion. To put this in other words, Fuller envisaged dance as profoundly deconstructive, a critique of both aesthetic perception and musical signification.Footnote 27

Caddy also discusses Valentine de Saint-Point's highly cerebral métachorie, which ‘imagined an artistic defense mechanism, a protective shield against the musical magnetism that rendered dance merely contingent, merely representational’.Footnote 28 As these two examples demonstrate, questions of synthesis – in various and divergent iterations – preoccupied many, if not most, artists at the début de siècle. I would suggest that Daphnis, despite its contemporaneity with these most ‘modern’ of ballets and dancers, subscribed to a type of synthetic artistic production that persisted from the nineteenth century. Seen this way, the animating force of Ravel's music for Fokine's choreography serves as a useful foil for the more prospective complications of L'après-midi d'un faune.

The synthetic aspects of the ballet were amplified in sections utilizing the eoliphone (also known, more casually, as the wind machine), the unquestioned instrumental celebrity of the score. An orchestral novelty, it had made dramatic appearances in works such as Strauss's Don Quixote (1897). In Daphnis, its function was more than atmospheric, though it did contribute to the ‘hazy sensuality’ of Ravel's ancient Greece. As critics then and now have noted, the ballet's scenario has little action and intrigue, apart from the fruitless pirate shenanigans.Footnote 29 The slight narrative derives all of its meagre momentum from Pan's two timely appearances: at the behest of Nymphs and in order to trounce the pirates. (Even Daphnis and Chloé's only real coupling occurs while in disguise as the god and his beloved prey, Syrinx.) The stage direction for the opening scene describes Pan's odd yet potent dramatic position:

A meadow at the edge of a sacred wood. In the background, hills. To the right, a grotto, at the entrance of which, hewn out of the rock, is an antique sculpture of three Nymphs. Somewhat toward the background, to the left, a large rock vaguely resembles the form of the god Pan.Footnote 30

Daphnis himself comes across as a pliant bystander, swooning at Chloé's abduction and remaining absent through all of Part Two, only to reappear after her safe return. Daphnis prostrates himself before the sculpture of the Nymphs who, perceiving his distress, slowly come to life. The Nymphs move first to other-worldly strings, then halting winds, and finally the eoliphone (in its first appearance in the ballet). After presenting a danse lent et mystérieuse, they spot the prone Daphnis. They dry his tears, lead him towards the rough-hewn rock, and there invoke Pan in order to accomplish the rescue of Chloé. The eoliphone sounds intermittently through this sequence, accompanying the Nymphs’ actions (see Example 1). When Daphnis moves to offer himself in supplication, it falls silent, reinforcing its association with non-mortal beings. Ravel exchanges the eoliphone for a pianissimo bass-drum roll as Pan's outline appears on the rock face; its deeper register underscores the ominous forces at work. The eoliphone is directly associated with Pan at his second and final appearance. Having grown tired of watching Chloé's wilting dance, the pirate king Bryaxis moves to carry her off (presumably to rape her), but supernatural effects suddenly beset the atmosphere. Satyrs – Pan's traditional coterie – surround the brigands, and according to the stage directions the god's ‘fearsome shadow is outlined on the hills in the background, making a threatening gesture’.Footnote 31 A swell to fff on the eoliphone accompanies this moment, after which the pirates flee (see Example 2). As with the Nymphs, the sound of the machine announces the movement of a superhuman figure. Here Pan's ‘action’, however, is reduced to an unspecified gesture or, more accurately, to a shadow of a gesture, according to the scenario – akin to the bas-reliefs and sculptures Daphnis was based on, as are the animated Nymphs.

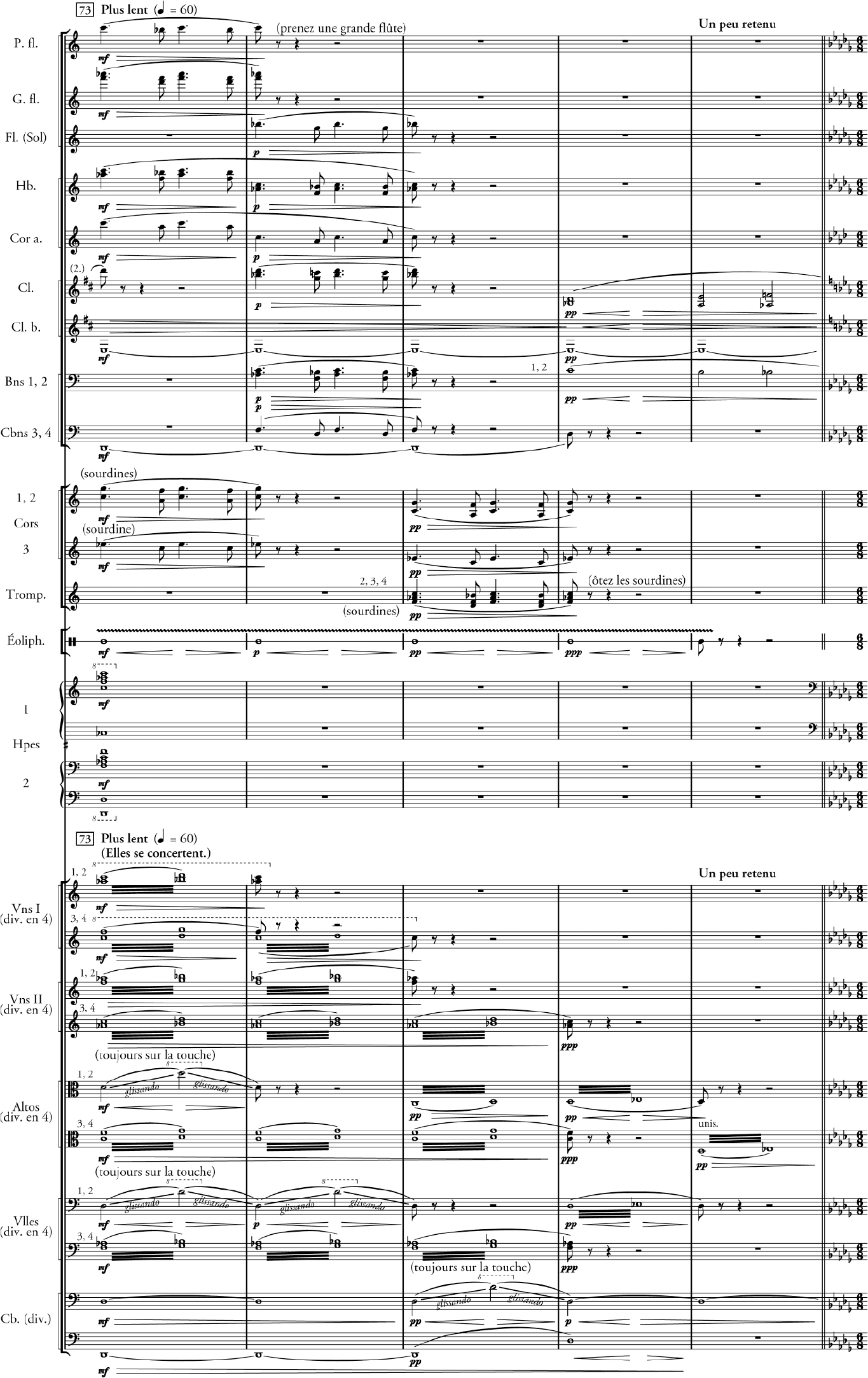

Example 1. Ravel, Daphnis et Chloé (1912), from figure 73.

Example 2. Ravel, Daphnis et Chloé (1912), from bar following figure 152.

Ravel's use of the eoliphone here and in the previous instance presents a pair of moments in the ballet that can be extrapolated as a larger comment on the work's original production. Dorcon's clumsy bumbling and Daphnis's fancy footwork provide examples of the way Ravel's music illustrated gestures, but the appearance of the eoliphone suggests that sound not only facilitated physical animation, but actually replaced it at crucial junctures. The moment of greatest dramatic tension – indeed, one of the few moments during which people are not merely standing around watching others dance – requires no overt instigation. Instead, the eoliphone serves as a surrogate, sound replacing movement in a way generally unfamiliar to ballets of the period.Footnote 32

As this reading of the eoliphone's peculiar status suggests, Daphnis's relationship to statues and statuomanie is more complicated than a first glance might suggest. Fokine hoped that in basing the ballet's gestures on statuary, his choreography would represent the kind of realism that bordered on the naturalistic, which he had aimed for since leaving Russia: a renovated, particularized vocabulary of movement to replace the stylized, decorative gestures of classical ballet. ‘Just as life differs in different epochs’, he explained,

and gestures differ among human beings, so the dance which expresses life must vary. The Egyptian of the time of the Pharaohs was very different from the Marquis of the eighteenth century. The ardent Spaniard and the phlegmatic dweller in the north not only speak different languages, but use different gestures. These are not invented. They are created by life itself.Footnote 33

But instead of archaeological verisimilitude, Fokine found his use of statuary to be more akin to that of the contemporaneous statuomanie engulfing his adopted city. Mary Simonson has written about Hellenism in American pageants, but a broad statement she makes about the uses of classicism applies here too:

Ancient Greece symbolized a simpler, unified society in which people were intimately connected with their own bodies, the natural world, and that which was beautiful and good. As a result, Hellenism was surely a cure for greed and anti-intellectualism, and a source of taste, enlightenment, and refinement in the increasingly secular, industrialized world.Footnote 34

If the Parisian statuomaniacal impulse was about disseminating certain laic virtues through the proliferation of stone figures purportedly embodying them, then Fokine's animated balletic statues were to embody gesturally his own aesthetic values. Artistic synthesis, then, trumped realism as antiquarianism gave way to the holistic principle guiding the ballet. Ravel's illustrative score suggests the extent to which the integration of media mattered to both collaborators. Despite dabbling, as was au courant, in statuary, the ballet remained faithful to a familiar aesthetic model from the nineteenth century. Daphnis privileged the synthetic – symbiotic gesture and music – over a desire for the realistic. Not so L'après-midi d'un faune.

Moving music

The urban absurdity of statuomanie underscores France's political priorities, which coincided with ballet's own: renovations of the present through restagings of the past. But the nation was also undertaking a much more practical re-evaluation of time. Between 15 and 23 October 1912, Paris hosted the Conférence Internationale de l'Heure. Greenwich had been the zero meridian for nearly 30 years, but the French had stubbornly refused to submit to its horological primacy. Recognizing both the value and the inevitability of global standardization, President Raymond Poincaré organized a conference that would begin the process in France. A wily political move, it served to diminish any lingering exasperation with the nation's clocks. Though endless quibbles delayed standardization for another year, 1912 marked a watershed, as Stephen Kern describes it, in the effort ‘to rationalize public time’.Footnote 35 Time itself, however, was simultaneously entangled in its own ontological complications. Was it cellular, a parade of discrete instants, or more hydroponic, emerging from a continuous and indivisible stream? And how did one reconcile the new strictures of public time with the intense subjectivity of private time?

Proust grappled famously with these questions, but the most influential contribution came from the philosopher Henri Bergson, who provided an aggressive, if elegantly packaged, attack on prevailing notions of time. For Bergson, true lived experience depended on the concept of durée, which he described as ‘the continuous progress of the past which gnaws into the future and which swells as it advances’.Footnote 36Durée was heterogeneous, subjective, sequential and interior, whereas its falsely objective counterpart was homogeneous, spatialized, simultaneous and public. Bergson's argument took aim at positivist thinkers of the time, whom he berated for their plodding, segmented analyses of the known world. True knowledge came instead from intuition, a perceptual mode that evaded analysis. As he wrote in An Introduction to Metaphysics, ‘By intuition is meant the kind of intellectual sympathy by which one places oneself within an object in order to coincide with what is unique in it and consequently inexpressible. […] Intuition, if intuition is possible, is a simple act.’Footnote 37 Intuition offered true perception, an unmediated experience of reality.

In the process of explicating the indivisibility of durée, Bergson turned to music:

Listen to a melody with your eyes closed, thinking of it alone, no longer juxtaposing on paper or an imaginary keyboard notes which you thus preserved one for the other, which then agreed to become simultaneous and renounced their fluid continuity in time to congeal in space; you will rediscover, undivided and indivisible, the melody or portion of the melody that you will have replaced within pure duration. Now, our inner duration, considered from the first to the last moment of our conscious life, is something like this melody.Footnote 38

As Kern has noted, Bergson's definitions of durée were notoriously, and wilfully, opaque.Footnote 39 Music, however, provided a comparatively straightforward analogy. Melody, when apprehended in fluent sequence rather than spatial simultaneity, mirrored the processes of one's own lived experience in time. Others related Bergson and his work to music as well. Writing for Comoedia, the critic Louis Laloy published in 1914 an article subtitled ‘M. Henri Bergson et la musique’. After a brief précis of key philosophical concepts, Laloy sketched a parallel between music and durée:

Music is a temporal art. Without a doubt the reading of a poem is successive, and we contemplate a picture or a statue as we might browse a book. But the difference here is that music is complete only once performed, and this performance does not depend solely on the duration that we would like to choose, but a particular duration, of which the form and the movements are determined. It is by this property that music comes so easily to us, while we listen to a soul that is its own, and not ours.Footnote 40

Laloy went so far as to describe a modern trinity, made up of Bergson, Debussy and Rodin. Each, in his respective medium, ‘manifested the state of our society even as they determined it. It is for this reason that secret connections unify them, and one can say that such music could not be produced except in the company of such philosophy, and vice versa.’Footnote 41 The links between Bergson and Debussy struck Laloy so strongly that he neglected to include Rodin and his art in the final phrase. Bergson himself had acknowledged having an ‘intuitive predilection’ for Debussy's music, describing it as ‘a music of duration because of the use of a continuous melody that accompanies and expresses the unique and uninterrupted current of dramatic emotion’.Footnote 42

Unlike Daphnis, L'après-midi d'un faune began its life as a stand-alone orchestral score. Composed between 1891 and 1894, it was Debussy's breakout work, his only effort of comparable size up to that point being the far less original symphonic suite Printemps, written during his Prix de Rome sojourn. Based on the poem by Stéphane Mallarmé, the Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune derived inspiration from the text without attempting, as Debussy professed, any exact illustrative effects. Calling it in a letter to his friend the critic Gauthier-Villars ‘the general impression of the poem’, he continued: ‘If the music were to follow it more closely it would run out of breath, like a dray-horse competing for the Grand Prix with a thoroughbred.’Footnote 43Fin de siècle reviewers agreed, at least about the music's elusiveness, even evasiveness. Writing for Le Figaro, Charles Darcours categorically dismissed the work:

We did not enjoy Debussy's Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune, based on an eclogue by the poet Mallarmé. The quest for a play of timbres is this young composer's only interest, though it is true he is highly skilled at the areas in which he specializes. Pieces of this sort are pleasurable to write, but not to hear.Footnote 44

Others were similarly indifferent. André Ghesse found ‘not much music’ in the score beyond its bewitching aural colours.Footnote 45 A critic for Le temps was more generous, though he did note the rarefaction that surrounded many a Debussy composition.Footnote 46 While the Prélude seems to have dodged the accusations of spinelessness that Daphnis accrued, its music was certainly not conventional ballet music – that is, music with a pronounced rhythmic profile.

We can hear this nebulousness most clearly – if that is not too oxymoronic a task – at the climax of the work. Cast in D♭ major (the enharmonic parallel major of the suggested opening tonality), the section utilizes an unimpeded triple-time signature. But as Debussy builds the music, he simultaneously integrates triplets phrased in two, adding a new and disorientating level of subdivision. The effect is comparable to Bergson's heterogeneous, uninterrupted flow of time and melody, a ‘music of duration’. The piece, however, does not end there, and instead returns to the languorous opening flute solo, this time raised slightly from its torpor by pianissimo harp figurations. So while resonances exist between Bergson's philosophical meditations on time and Debussy's own temporal manipulations in the Prélude, there are ways in which his music cannot be entirely subsumed under a Bergsonian rubric. What I do hope to have shown, however, is that the concrete historical links between these two men – as shown in Laloy's article and Bergson's own invocations of his compatriot – hint that the Prélude's complicated afterlife was due to more than personal fractiousness between Debussy and Nijinsky.Footnote 47 Shifting notions of time, encapsulated by Poincaré's civic negotiations and discernible in the aesthetic preoccupations of belle époque artists, were responsible for a kind of cultural fractiousness as well. The balleticized Prélude served as a site of corporeal negotiation for these shifts, with Debussy's score not just an odd partner for Nijinksy's choreography, but instead at philosophical odds with it.

A faun's coterie

Laloy forgot about Rodin, but we need not. Even such an esteemed artist did not escape censure for his contributions to Parisian statuomanie. This civic blight had come to the attention of the New York Times, which reprinted part of Le Corbellier's address to the Paris Art Commission. ‘Why’, he pressed them, ‘is the statue of the “Penseur” by Rodin, on the steps of the Panthéon? Why three statues to Alfred de Musset? How many, in that case, should Victor Hugo have?’ Le Corbellier's proposed solution was to corral these monuments at the city's outskirts, arranged in ‘intelligent order’ so as to ‘accomplish their [didactic] purpose’.Footnote 48 But even as these stone guests overstayed their welcome on busy boulevards, Parisian museums curated archaeological exhibitions of ancient artefacts that drew, among others, choreographers such as Fokine and Nijinsky.

Although Fokine's choreography for Daphnis was based on actual Greek statuary, Nijinsky's for the Prélude, so the story goes, owed as much to ancient Egyptian artefacts at the Louvre as to true classical works. As his sister Bronislava Nijinska recounts in her memoirs, Nijinsky declared:

I want to move away from the classical Greece that Fokine likes to use. Instead, I want to use the archaic Greece that is less known and, so far, little used in the theater. However, this is only to be the source of my inspiration. I want to render it in my own way. Any sweetly sentimental line in the form or in the movement will be excluded.Footnote 49

Even before L'après-midi d'un faune's première, then, its aesthetic sensibilities had diverged both from Ravel's hazy, eighteenth-century Greece and from Fokine's naturalistic, rotund Hellenic gestures. The collaboration – if it could even be called that – between Nijinsky and Debussy shunned the sort of synthesis Daphnis so prized. Indeed, it was only Diaghilev's slick charm and deep pockets that vouchsafed the project in the face of the composer's reluctance. Nijinska recounts the tortured inception of the choreography, recalling that the ballet required an exactitude of execution at odds with conventional balletic practice, which often benefited from the embellishment and improvisation of the artist. Nijinsky, however,

was the first to demand that his whole choreographic material should be executed not only exactly as he saw it but also according to his artistic interpretation. Never was a ballet performed with such musical and choreographic exactness as L'Après-Midi d'un Faune. Each position of the dance, each position of the body down to the gesture of each finger, was mounted according to a strict choreographic plan. One must remember that the majority of dancers in this ballet could not understand Vaslav's composition. They did not like the choreography at all. They felt they were restricted and would often complain, saying such things as ‘What kind of ballet is this? … There is not a single dancing pas – not a single free movement – not a single solo – no dances at all … We feel as though we are carved out of stone.Footnote 50

If Nijinsky turned his Faun and his Nymphs into statues, his sister served as his clay. For hours, he would use her pliable form to sculpt the postures he saw so clearly in his mind's eye, but that eluded the descriptive language needed to convey these ideas to his dancers. His Chief Nymph, Lydia Nelidova, proved the most problematic. Nelidova had been exported from Russia expressly for the role – her remarkable height and commanding presence lent her the appropriate gravitas. She, however, would exclaim: ‘Have I come all the way for this?’Footnote 51 Nelidova's caustic attitude, coupled with Nijinsky's own doubts about his readiness for this choreographic undertaking and the simmering rivalry between him and Fokine, amplified tensions in the weeks leading up to L'après-midi's première.

Those tensions have obscured more subtle, complex contexts for L'après-midi, contexts that speak to the issues of artistic synthesis (or lack thereof), as well as those of belle époque spectatorial practices. The scandal of L'après-midi's ending – an onanistic spasm and then melting relaxation – has been the subject of many a savoured retelling.Footnote 52 Much, too, has been made of the disjuncture between Debussy's sinuous music and Nijinsky's jerky gestures. Dance and music historians have often attributed the incommensurability of the ballet's expressive registers to conflicting aesthetic aims. That friction, however, was an echo of a deeper conflict, one having to do with the era's competing ontologies of time, and the resulting visual perception of bodies in motion.Footnote 53Daphnis and L'après-midi demanded different ways of seeing.

Intuitive seeing

It is in Bergson's work that issues of time and technology were linked explicitly to modes of seeing. In the final chapter of his Creative Evolution, Bergson explores, and ultimately critiques, the unsurpassed analytical capabilities of the cinematograph. Attacking the prevailing notion that cinematography animated the frozen image, Bergson suggests instead that it provides the illusion of motion – ‘immobility set beside immobility’, rather than fluid, unbroken movement. The parade of static images rendered on film merely simulated motion through the movement of the reel itself. Bergson exposes the artificiality of cinematography in order to present the false perceptual model of analysis rather than the truth of intuition. But in the process of making this argument, he offers deep insight into the mechanism of film as such:

Of the gallop of a horse our eye perceives chiefly a characteristic, essential or rather schematic attitude, a form that appears to radiate over a whole period and so fill up the time of gallop. It is this attitude that sculpture has fixed on the frieze of the Parthenon. But instantaneous photography isolates any moment; it puts them all in the same rank, and thus the gallop of a horse spreads out for it into as many successive attitudes as it wishes, instead of massing itself into a single attitude, which is supposed to flash out in a privileged moment and illuminate a whole period.Footnote 54

Film removed the representative and the aesthetic from the contemplation of motion. Instead of an elegant summation of a specific gestural moment (as in sculpture), technology, in its indifference, presented randomized views of any movement under consideration. In that way, cinematography stood in opposition to the concepts of intuition and durée. All it could offer was an unselective optical mode that supported analytical renderings at odds with the lived experience Bergson championed. The implications for L'après-midi d'un faune were great: rather than the sonic wash of Debussy's score, the gestures of the ballet subscribed to a much more fragmentary conception, which itself was rooted in the mechanical apparatus that Bergson abhorred.

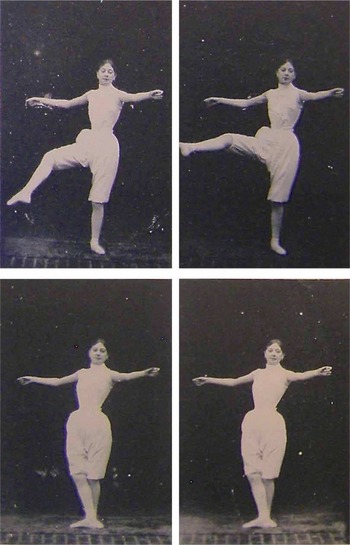

Technologies such as the chronophotograph and the cinematograph were brought to bear on L'après-midi through contemporary critical studies, one example being Maurice Emmanuel's thesis on the issue of animating images from antiquity. He undertook a study of Greek orchestique for his doctoral work, the point of which was, in his words, ‘an archaeological restoration the components of which are the orchestics furnished by the monuments figurés’.Footnote 55 The main method for his reconstruction of ancient dance was the examination and reanimation of artefacts. Chronophotography played an integral role in this thesis. Emmanuel utilized the technology to dismantle complex motions (using a plainly garbed female model among others; see Figure 2) which he then compared with the images from antiquity.

Figure 2. Maurice Emmanuel, Essai sur l'orchestique grecque: Étude de ses mouvements d'après les monuments figurés (Paris, 1895), section entitled ‘Les exercises préparatoires’, excerpts from Figure II.

Around the same time, one of Bergson's illustrious colleagues at the Collège de France was also using the apparatus to launch a revolutionary, scientific study of bodily mechanics.Footnote 56 Although Étienne-Jules Marey began these studies as early as the 1850s, his most important contributions date from the fin de siècle. In his 1891 explication of chronophotography for the Revue générale des sciences, he granted that conventional photography allowed the study of objects and beings at rest ‘to perfection’,Footnote 57 but failed when motion entered into the equation. How might one harness the unique abilities of the camera, he asked, in order to observe things in motion with the same acuity? Chronophotography provided the answer. In its ability both to fix otherwise undetectable motions on film and to depict motion through rapid succession, the technology invited a range of applications that Marey detailed in his Revue générale article. Scientists and other interested parties could now study terrestrial, aquatic and aerial motion of humans and other animals with new precision. He even provided representative illustrations of men running, tortoises swimming and birds flying, among other images.

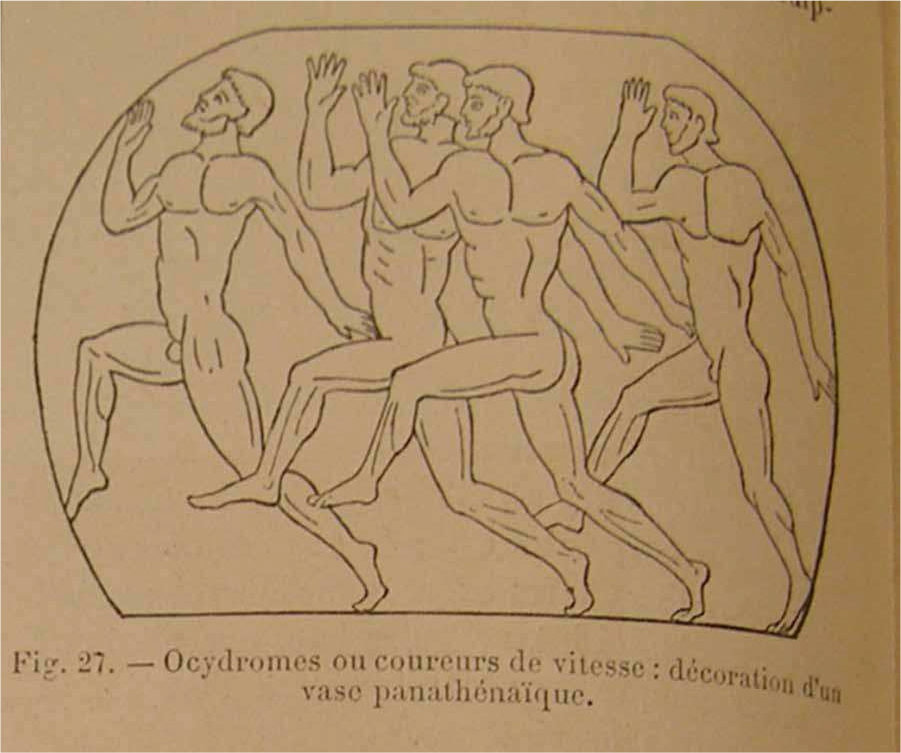

Nested between these applications, however, was a section entitled ‘Application aux beaux-arts’. Marey suggested that certain artists had already taken advantage of documentary photography to achieve an ‘authentic image’ of ‘the attitudes of man or animals in their most rapid states of movement’.Footnote 58 Art from antiquity, he argued, presented a less accurate depiction – more frenzied, less balanced – of running figures, whereas modern images aligned more with reality, courtesy of photography. For his example of the former, he offered an image from a vase panathénaïque. On its surface, the artefact resembles the chronophotographic images Marey reproduced throughout the article: a picture of four nude, muscular runners (see Figure 3). He even identified a certain congruence between one of the figures and a photographic image of a man running provided in his next example. But whereas the photographic image captured a randomized moment, Bergson would say, the vase represented deliberate, stylized summaries of four postures in running – the difference between the optical mode of the chronophotograph as opposed to perception grounded in an experience of durée. Marey's triumphant description of the technology's manifold possibilities was thereby dependent on a model of rationalized time opposed to Bergson's ‘heterogeneous flux’, to borrow Marta Braun's apt phrase.Footnote 59 By this logic, the gestural repertoire of Debussy and Nijinsky's ballet stood in direct contrast to the music's guiding principle. Unlike Daphnis's comparatively untroubled symbiosis, then, L'après-midi d'un faune engaged in a friction-filled production as well as collaboration.

Figure 3. Illustration from Étienne-Jules Marey, ‘La chronophotographie: Nouvelle méthode pour analyser le mouvement dans les sciences physiques et naturelles’, Revue générale des sciences, 21 (15 November 1891), 689–719 (p. 706).

Several reviewers noted the disjunction between Debussy's svelte, Bergsonian score and Nijinsky's spasmodic choreography. In Le temps, Lalo described the music's ‘undulating and supple lines’, in contrast to the ‘rigid, mechanical postures’ with ‘everything angular and jerky’.Footnote 60 Even as it scolded L'après-midi's conclusion, Le gaulois praised Debussy's ‘exquisite’ score.Footnote 61 Vuillermoz offered the most verbose comparison, writing of the ‘marionette-like gestures’ of the dancers and the ‘voluptuous suppleness’ of the music.Footnote 62 As these excerpts suggest, what disturbed critics was the contrast between the music, pristine in its timeless, recondite harmony, and gestures that took on the signifiers of modern life. Mechanical, linear, geometrical even – these adjectives were echoed in other publications. The Journal des débats politiques et littéraires spoke of ‘brusque, automatic movements’, resembling the dancing of ‘mechanical dolls’,Footnote 63 while Le courrier musical dubbed the ballet a ‘scientific’ pantomime.Footnote 64 Charles Méryel even compared the dancing to a cinematographic animation of bas-reliefs.Footnote 65 Lalo went the furthest in his flagellation of the unartful choreography: ‘Dismantle is the right word: nymphs and faun “take movement apart”, exactly like military exercises; one thinks of the gestures of an automaton, and of the Prussian infantry on parade.’Footnote 66 This insinuation of the militaristic lent the movements of L'après-midi an ominous cast. Marey's proto-cinematic experiments, then, suggest that the rationalization of time engineered by Poincaré was echoed in the rationalization of how bodies should move. Dancing bodies were not exempt from this influence.

Frieze frame

The two ballets under consideration demonstrate allegiances to conflicting temporal ontologies and optical epistemologies. Daphnis privileges protracted, reflective looking over L'après-midi's more observational mode. In Ravel and Fokine's ballet, characters stand around and watch each other dance for much of the time, acting as a sort of diegetic audience framing the opening contest, Lyceion's attempted seduction of Daphnis, Chloe's dance of supplication for the pirates, and the pantomime between ‘Pan’ and ‘Syrinx’ before the rollicking finale. Even the wordless chorus – a nod to Greek theatre in another guise – contributes to the impression of Elysian sensuality rather than observing or commenting on the ensuing action. With the exception of Dorcon's graceless number, which is presumably met with laughter from both audiences (on and off stage), each of these moments depicts exemplary dancing. Whatever their sentiments about the music, the sets, the scenario or other aspects of the production, critics unanimously praised the performances of Nijinsky and Karsavina: his ‘grace and eurythmic agility’, her ‘languid charm’.Footnote 67 These performances within the ballet thus recreate the act of watching Daphnis itself, subscribing to an older, synthetic and contemplative, model of production and reception. Ravel worked to create a score that translated Fokine's ‘silent language of arms and legs’ into music.Footnote 68 It was ‘systematically danceable’.Footnote 69

L'après-midi d'un faune, however, presented the balletic body as something to be empirically observed – not over time, but in the moment. In his memoirs, Fokine suggested that L'après-midi could be classified as a pantomime rather than a ballet with ‘no harm done’:

But harm can be done when this series of poses is introduced as a new form of dance and the new road along which, from 1912 on, the ballet should develop. That course was being seriously suggested at the time. It is fortunate that this prediction, made for publicity purposes, did not materialize. In the twenty-eight years since the premiere of ‘Faune’, ballet has not made a single step in the direction indicated by Nijinsky's work. But how could it have been otherwise? How could dance develop on a base completely devoid of dancing?Footnote 70

Fokine's sarcasm was directed at Nijinsky's idiosyncratic gestural repertoire, much of which concentrated on the minute manipulations of one body part to the exclusion of all else. While Daphnis is narratively static, L'après-midi is choreographically so.Footnote 71 The opening depicts the Faun reclining on his rocky ledge, playing his flute with offhand indolence. Abandoning his instrument, he tastes some grapes before being distracted by the arrival of the lovely Nymphs. Much of the next section deploys the mechanistic near-marching so reviled by Nijinsky's colleagues and critics alike. Between the sparse movements, the Nymphs pose in groups resembling antique statuary – usually in threes, as was customary in such artefacts. Preparing for her bath, the Chief Nymph drops her final veil and is left alone with the intently observing Faun. They engage in a protracted interaction, he stalking and she (reluctantly) retreating. Their denuded pas de deux culminates in one of the ballet's few moments of physical contact: interlocked elbows that coincide with the beginning of the musical dénouement (see Figure 4). The ballet concludes with the Faun procuring his escaped prey's veil, and the ensuing dance he enacts with this surrogate. Choreographically, the ballet remains angular and static, focusing on specific parts of the anatomy: most memorably a flat, outstretched palm with splayed thumb.

Figure 4. Photograph of Nijinsky and Nelidova (as Faun and Chief Nymph) taken by Baron Adolf de Meyer (1912). Reproduced by kind permission of Dance Books from Jennifer Dunning, L'après-midi d'un faune: Vaslav Nijinsky 1912: Thirty Three Photographs by Baron Adolf de Meyer (London, 1983).

As Emmanuel writes in his study, ‘Mechanical movements and expressive movements or gestures are clearly distinguished in our era and in our customs from the dance, or from the orchestics, as the Greeks called them. Orchestic movements are, in fact, neither purely mechanical nor strictly mimetic.’Footnote 72 As reviewers noted, the dancers in L'après-midi resembled modern machinery of the time, a curious conflation of the retrospective and the prospective. Critics such as Svetlov had made such comparisons before, though in the context of virtuosity: ‘The human being transforms itself into a machine, and a machine can deploy a technique as pure and abundant as one could wish. And that is why everything this mechanism produces ceases to be interesting.’Footnote 73 When reviewers harnessed the language of mechanicity and automatism to describe Nijinsky's choreography, however, it was not in response to his virtuosity. There was only one leap in the entire ballet, which the Faun executes in his pursuit of the Chief Nymph. Far from a moment of transcendence, it was instead an animalistic pawing given flight. The ballet shunned impressive gesture in favour of an unhurried examination of flexing musculature and held postures.

In that way, L'après-midi's choreography reflects the developing technologies of observation that fragmented and scrutinized the body for greater efficiency, unlike the parade of ballets it preceded. It even diverged from Ravel and Fokine's production, with which it shared an interest in antiquarianism. Its bodies are fragmented and disjointed; it declines more familiar musical and choreographic cohesion; and it dramatizes observation as its optical mode. In perhaps the most charged moment of the work – when they are alone on stage, engaged in their protean courtship – the Faun and the Chief Nymph interact through their eyes as much as, if not more than, through their bodies. Caddy has read this moment as one of audiophilia, when the characters are hypnotized by Debussy's music:

Stage gesture [or rather a lack of it] sets the music apart as an object of attention, one that is seemingly experienced by characters on stage […] This beautiful, gushy, overripe, clichéd, Romantic, bel canto theme inveigles the characters into a sensual immediacy betrayed by their exaggerated stillness – a stillness that in turn betrays music's infamous power to enthrall.Footnote 74

Such a reading, however, neglects the intensity of their visual connection. During the stasis that Caddy identifies, the Faun and the Nymph engage in a kind of charged mutual observation that belies their stillness. Each scrutinizes the other, plotting the next, protracted foray. At the most Bergsonian moment in the score – when musical and experiential time gush forth unimpeded – the gaze becomes acutely intent and gestures minimal. The choreography's stasis sets the music's kinesis in even sharper relief, delineating the incongruence between the optical and aural registers: the music moves, the bodies do not.

The statuomaniacal impulse

Historians have long noted the rupture between music and dance in L'après-midi d'un faune. Hanna Järvinen describes how audiences had to reconcile ‘new kinds of relations between the musical score and the bodies of the dancers performing on stage’. Her argument is that Nijinsky's ballet proved important because ‘it emphasized the choreographer as the absent author of dance’ owing to its jarring formal qualities.Footnote 75 In Caddy's consideration of the work, she also questions the relationship between the ballet and changing practices of spectatorship. She traces its iconology to Charcot's Salpêtrière and the contorted, hysterical bodies on display there. While arriving at a related conclusion, I suggest that L'après-midi's imagery stemmed from a far closer source. Ballet and the nation engaged in statuomania for the purposes of renovation – an engagement that had unanticipated consequences for dance in the form of L'après-midi.

Which returns us to the statues with which we started. Beethoven's luckless Parisian fate aside, the Third Republic's statuomanie illustrates French political priorities, which coincided with ballet's own: renovations of the present through restagings of the past. During the belle époque, popular physical culture shaped dance. Daphnis et Chloé and L'après-midi d'un faune participated in this larger context through a reformation of ballet's own public face. To use Agulhon's turn of phrase, the ‘didactic monumentalism’ (‘monumentalité didactique’) of statues aimed to renew civic virtue and thereby help the nation cohere, particularly in the face of impending military conflict.Footnote 76 The balletic body seems to have felt this influence in the shift from a flurried and frivolous gestural repertoire to one more grounded and, as we have seen, searchingly realistic. That realism, however, had consequences not only for dancers, but also for viewers, who themselves were grappling with a new culture of visuality based on emerging optical technologies. Martin Jay has persuasively argued that ocularcentrism was itself under assault during the fin de siècle and the belle époque.Footnote 77 I have attempted to demonstrate that a multimedia art form such as ballet underwent its own curious dérangement: in Daphnis, the extreme symbiosis of music and gesture, which reinforced the synthetic principle at work in its production; in L'après-midi, the replacement of the fluid and fluent gestures of contemplated bodies to the minute flexing of analytically observed physiques. While Fokine and Nijinsky both succumbed to the statuomaniacal impulse, each choreographer channelled that impulse singularly and specifically. Even as at crucial moments in both ballets sonic kinesis emphasizes somatic stasis, Daphnis and L'après-midi staged divergent conceptions of how bodies could and should move.

But in one of those unforeseeable and delectable historical reversals, Debussy's music itself turned to stone after his death. Marianne Wheeldon discusses the composer's legacy as amalgamated by La revue musicale in its ‘Tombeau de Claude Debussy’. Published in 1920, the issue contained three forms of homage: articles on the composer's life and career, foreign-correspondent style accounts of his influence abroad, and ten brief scores solicited for the occasion. ‘Considering the number and variety of contributions to the Debussy issue,’ Wheeldon writes, ‘it is perhaps surprising that so little mention is made of the last four years of the composer's life.’ She continues, noting the less than laudatory tone evident in several of the submissions: ‘The compositions of the Tombeau, if they pay tribute to his musical style at all, dwell almost entirely on works drawn from earlier in his career.’Footnote 78 Probably to nobody's surprise, one of those earlier pieces was Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune. In the period after his death, the work so defined Debussy's oeuvre that it was immortalized in stone, along with Le martyre de Saint-Sébastien and Pelléas et Mélisande, at the Parisian monument erected in his honour (see Figure 5). Conceptualized in maquette as early as 1923, though not fully realized until nearly a decade later, the memorial was the work of the twins Jean and Joël Martel, both familiars within the arty bon ton.Footnote 79

Figure 5. Jean and Joël Martel at the inauguration of the Debussy memorial (1932). Reproduced from Gallica: ‘Inauguration du monument élevé à Claude Débussy: Jean et Joël Martel, les deux sculpteurs du monument de Claude Debussy’ (press photo, Agence Mondial).

In his article for La semaine à Paris, Charles Fegdal described the aim of the brothers Martel as follows: ‘to penetrate, to understand, and to express in sculpture Debussy's esprit mallarméen’.Footnote 80 Although the score of the Prélude was by then nearly 40 years old, it continued to guide, indeed to dictate, the composer's rhetorical, musical and, now, monumental reputation. An extended piece for La renaissance de l'art français et des industries de luxe in anticipation of the work's completion went further, describing the Martels’ sculptural style as ‘simplification of lines and forms, well-calibrated balance of proportions, [and] concern for linear and geometric frameworks’. Remove the mention of aesthetic equipoise, and these phrases echo the descriptions of Nijinsky's choreography for L'après-midi we encountered earlier. This resemblance was no accident, as the author of the article suggested that the Martels depicted not their own conception of the music, but instead ‘a sort of interpretation by the ballet russe’.Footnote 81 Even in Debussy's monumental afterlife, then, the Prélude's music was endlessly refracted through a Nijinskian prism.

These two articles on the Debussy memorial in Paris spent much time meditating on and rhapsodizing about the Martels’ careful synthesis of the sculpture with its natural setting. Fegdal recommended visiting in the late morning – eleven o'clock, to be precise – in order to see the work with the light hitting just so, illuminating the details of the monument, the shimmering pool in front, and the lush foliage all around.Footnote 82 This attention to harmonious enmeshment differentiated the Debussy sculpture from that of many a composer, as did the Martels’ decision not to portray him in phlegmatic verisimilitude, wearing everyday, albeit spiffy, clothing. To Paul Sentenac, the brothers made ‘a confession’. As children, ‘they often played in the paths of the Parc Monceau’, one of Pessard's original examples in his shrill critique of the stone blight descended upon various Parisian locales. In their own art and time, including their stone memorial to Debussy, the Martels attempted to resist such indiscriminate statuefication.Footnote 83