INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, radiocarbon dating was frequently used for dating organic admixtures in pottery (e.g. Hedges et al. Reference Hedges, Tiemei and Housley1992; Skripkin and Kovalyukh Reference Skripkin and Kovalyukh1998; O’Malley et al. Reference O’Malley, Kuzmin, Burr, Donahue and Jull1999; Kuzmin Reference Kuzmin2012). It is extensively applied to dating the late Stone Age cultures in eastern Europe because the availability of other organic materials is limited (Zaitseva et al. Reference Zaitseva, Skripkin, Kovaliukh, Possnert, Dolukhanov and Vybornov2009; Vasilieva Reference Vasilieva2011; Vybornov et al. Reference Vybornov, Zaitseva, Kovaliukh, Kulkova, Possnert and Skripkin2012).

Although the Bronze Age sites in east European steppes provide a variety of other carbon-containing sources, pottery dating lately became widespread for age determination of Bronze Age cultures (Chernykh and Orlovskaya Reference Chernykh and Orlovskaya2011; Kuznetsov Reference Kuznetsov2013) However, in this case the ages determined were often significantly older compared to earlier results (Morgunova and Khokhlova Reference Morgunova and Khokhlova2013; Morgunova Reference Morgunova2014). For example, the age of the Yamnaya culture based on 14C dating of pottery was determined to be more than 500 yr older compared to previous 14C dates obtained on other materials (Morgunova and Khokhlova Reference Morgunova and Khokhlova2013). The chronology of the Early Yamnaya period was based on 18 pottery 14C dates, three values run on human bones, and a single date on soil humus (Morgunova and Khokhlova Reference Morgunova and Khokhlova2013: Table 1). In determining the age of the classic Yamnaya period, 30 14C dates on human bones, 8 values on wood, 4 dates on soil humus, and 2 values on pottery were used (Morgunova and Khokhlova Reference Morgunova and Khokhlova2013: 1293, Table 2). Thus, the age of the Early Yamnaya period was determined with 81.1% of dates run on pottery, while for the Middle Yamnaya period the majority of dates (68.1%) were obtained on human bones, and 14C pottery dates made up only 4.5% of the total. It is therefore important not to rely on dates run on pottery but also consider other organic sources from the same cultural complexes. The Bronze Age sites of the east European steppe provide a good opportunity for this.

The Bronze Age is a significant historical period, which began in the mid-4th millennium BCE and ended at the transition from the 2nd to 1st millennia BCE. The eastern part of this vast area is bounded by the Ural Mountains. The largest rivers in east European steppe include the Volga, the Ural, the Don, and their many tributaries. Grasslands made this region suitable for cattle breeding. Populations of cattle-herders were dominant on this territory, and they left numerous burial mounds and habitation sites with cultural layers rich in archaeological remains.

This paper therefore aims to determine whether 14C dates run on pottery can provide credible age information, are reliable to build a Вronze Age cultural chronology, and puts forward evidence showing that pottery analysis results in older dates.

METHODS

There is a large data set of Neolithic 14C dates mostly obtained on pottery from different regions in eastern Europe (Zaitseva et al. Reference Zaitseva, Skripkin, Kovaliukh, Possnert, Dolukhanov and Vybornov2009; Vybornov et al. Reference Vybornov, Zaitseva, Kovaliukh, Kulkova, Possnert and Skripkin2012). Bronze Age pottery was also actively dated, often by applying the technology developed by Skripkin and Kovalyukh (Skripkin and Kovalyukh Reference Skripkin and Kovalyukh1998). This method allows analyzing all the organic admixtures in pottery. The carbon contained in pottery is converted into the lithium carbide with further synthesis of benzene (Skripkin and Kovalyukh Reference Skripkin and Kovalyukh1998). Currently, there are many 14C dates run on human and animal bones from the Bronze Age sites in eastern Europe (see Anthony Reference Anthony2007: 314–6). However, the pottery dates differ from the 14C dates obtained on other materials.

We sampled several Bronze Age sites that had 14C dates both on pottery and other carbon-containing materials. In addition, we dated three pots from three different sites (Lopatino kurgan 31 grave 1, Kizil-Khak II settlement, and Lebyazinka IV settlement), and had the opportunity to compare the dates obtained on two separate potsherds taken from each pot. Finally, we received and analyzed 24 14C dates from eight Bronze Age sites in east European steppes. Most of these dates are already published (see Anthony Reference Anthony2007: 266, 274–5; Kuznetsov Reference Kuznetsov2013: 18–20; Morgunova Reference Morgunova2014: 194).

MATERIALS

We analyzed the 14C dates from the sites undoubtedly corresponding to three main periods of the Bronze Age in the east European steppe (Figure 1). These archaeological cultures are clearly associated with certain periods, and their age determination is confirmed by the series of 14C dates.

Figure 1 Map of the Bronze Age sites used in the paper

The sites of the Yamnaya and Repin cultures belong to the Early Bronze Age (Anthony Reference Anthony2007). We analyzed the materials from the Repin Khutor settlement, Lopatino I burial ground, and Lebyazhinka VI and Kyzyl-Khak settlements. The Repin Khutor site on the Don River (49°11′29.13″N, 43°48′05.25″E) is a settlement with one cultural layer. We received four 14C dates on animal bones and six 14C values on pottery from this site. Mound 31 of Lopatino I burial ground on the Sok River (left tributary of the Volga River; 53°38′31.89″N, 50°39′15.04″E) belongs to the Yamnaya culture. We dated two potsherds of one pot and one human bone. Lebyazhinka VI settlement (53°41′27.60″N, 50°40′57.47″E) and Kyzyl-Khak settlement (46°56′01″N, 48°20′13″E) are sites with several cultural layers. We obtained four 14C dates on the Yamnaya–Repin pottery, two from each site.

The Late Yamnaya and the early Poltavka sites are related to the Middle Bronze Age (Anthony Reference Anthony2007: 328–36). Mound 6 of Skvortsovka burial ground on the Samara River (52°34′52.46″N, 52°08′10.91″E) and mound 4 of Tamar–Utkul VIII burial ground on the Ural River (50°53′03.93″N, 54°24′57.15″E) correspond to this very period. Two samples from each mound were dated: one pottery date and one 14C date on human bone from each site.

The Usmanovo III settlement (54°03′32.06″N, 55°31′48.29″E) is related to the Late Bronze Age generally dated to 1800–1600 BCЕ (Anthony Reference Anthony2007: 408–11). Some 500 m northeast from the settlement, the Usmanovo inhabitants created mounds over their relatives’ graves at the burial ground Kazburunovo l on the Urshak River (54°03′44.08″N, 55°32′08.1″E) (Shcherbakov et al. Reference Shcherbakov, Shuteleva, Golyeva, Lunkov and Kraeva2013). These two sites were abandoned by the Srubnaya people. There are two 14C dates on human teeth from two graves in the mound and one 14C date on pottery from the settlement.

Our study is based on materials from eight Bronze Age sites providing 15 direct pottery dates and 9 14C values on human and animal bones. Four 14C dates on bones were generated by the accelerator mass spectrometric (AMS) 14C method.

RESULTS

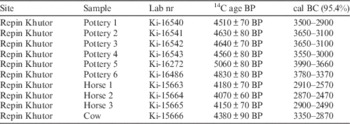

In order to determine the feasibility of direct 14C dates on pottery for archaeology of eastern Europe, we compared the dates obtained on pottery with the dates from other materials excavated at the same sites. An analysis was conducted on six fragments of pottery, three horse bones, and one cow bone (Table 1). Dates were calibrated with OxCal v 4 software (Bronk Ramsey and Lee Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013) and the IntCal13 calibration data (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013).

Table 1 14C dating results of pottery and animal bones found together in Repin Khutor (Kuznetsov Reference Kuznetsov2013).

Figure 2 summarizes the sum of date probabilities. The pottery gave much earlier 14C dates of 4000–3000 ВСE (95.4% confidence), and this is significantly different from values on the animal bones dating back to 3350–2450 ВСE.

Figure 2 Radiocarbon dates for Repin Khutor: (1) sum of 6 dates on pottery; (2) sum of 4 dates on bones; (3) both groups of dates combined. The black field means the area of overlay of the calibrated dates, obtained on pottery and bones. Dates calibrated with OxCal v 4 software (Bronk Ramsey and Lee Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013) and the IntCal13 calibration data (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013).

Figure 3 (numbers 1–5) and Table 2 present the analysis of human bones and pottery from three Yamnaya sites (Lopatino I mound 31 grave 1, Tamar-Utkul VIII mound 4 grave 1, and Skvortsovka mound 1 grave 6). There are 14C dates obtained on pottery from the Usmanovo III site, and on human teeth from the Kazburunovo I burial ground (Shcherbakov et al. Reference Shcherbakov, Shuteleva, Golyeva, Lunkov and Kraeva2013). Overall, we obtained 20 14C dates on both pottery and bones from six Bronze Age sites (Table 2), including 11 values on pottery and 9 dates on bones and teeth.

Figure 3 Dates for bones and pottery of Yamnaya sites (Early Bronze Age): (1) Lopatino I mound 31 grave 1; (2) dated pot from the ritual pit; (3) ochre-colored bowl beside the skull; (4) flint arrowhead in the buried body; (5) potsherd; (6) pot from Lebyazhinka IV; (7) calibrated dates on the Lebyazhinka IV pot.

Table 2 Paired dates from the same complexes on pottery, bones, and teeth*.

*The comparison of date pairs shows that all pottery 14C values are considerably older than bone and teeth ones, with the exception of the one coinciding pair from Skvortsovka mound 1 grave 1.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that pottery tends to give older dates in over 90% of cases in comparison with other materials excavated at Bronze Age sites in the east European steppes. Furthermore, the age of some potsherds was determined to be 500 yr older than the dates obtained on bones (Morgunova and Khokhlova Reference Morgunova and Khokhlova2013: 1290). Moreover, separate potsherds taken from the same pot gave different 14C dates.

To a certain degree, this is caused by admixtures in pottery containing crushed shells (Anthony Reference Anthony2007; Vasilyeva Reference Vasilieva2011: 74). However, we consider the origin of the raw materials used for pottery-making to be the basic reason for older age determination. The majority of the dated Bronze Age pots were made of silty clay (Salugina Reference Salugina2011: 87, 92). Silty clay is formed by sedimentary deposits at the bottom of a river. This material is characterized by a high concentration of organic matter, which can have a substantial age. Hence, the pottery dates are often on older carbon not associated with the archaeological period. Due to the unsystematic sedimentation of organic remains in silt, it is unlikely to find a general correction value that can be applied to all pottery 14C dates.

The dates obtained on Neolithic pottery excavated at east European sites form a similar picture. For example, Vybornov et al. (Reference Vybornov, Zaitseva, Kovaliukh, Kulkova, Possnert and Skripkin2012: 797) obtained 11 14C dates for the Neolithic site of Kairshak III, including 7 values on pottery, 3 on bones, and 1 on charcoal. All pottery 14C dates turned out to be older than the ones on bones and charcoal. Kuzmin (Reference Kuzmin2012: 124) previously addressed this effect. The Early Neolithic pottery from the Elshanka cultural complex does not have any organic temper (Vasilieva Reference Vasilieva2011), and pottery 14C dates will be a priori older compared to the actual age of this culture.

CONCLUSION

We have determined that Bronze Age pottery consistently gives older dates compared to the values obtained on bone and wood. The Bronze Age in eastern Europe is represented by various archaeological sites rich in other organic materials alongside with pottery. The use of wood, charcoal, and animal and human bones in age determination gives dates that appear to be more closely associated with the archaeological age. Thus, we consider direct 14C dating on pottery only appropriate for those archaeological periods that do not contain any other organic materials. In contrast, where the organic material was clearly deliberately added by potters just before firing the pot, this can be expected to give good results.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of a grant from the Russian Ministry of Education and Science (“Traditional and Innovational Models of a Development of Ancient Population in the Volga Region”). The research is conducted using funding from the Russian Foundation for the Humanities (15–11–63008). We are grateful to Dr Yaroslav V Kuzmin and the staff of Radiocarbon for extensive correcting and editing the original manuscript. We are grateful to Valeria Bondareva and Marina Petrovskaya for help in translation of this text.