Introduction

On 24 March 2005, whilst tens of thousands of protesters gathered in front of the main governmental building in the capital Bishkek and eventually stormed it, Kyrgyz President Askar Akayev fled to Russia. Earlier that month, in response to the fraudulent parliamentary elections held in February, protests had erupted sporadically in western and southern areas of the country, gaining momentum in Jalalabad. Eventually, the arrival of the protest movement in Bishkek proved fatal to the regime (Radnitz, Reference Radnitz2006). Akayev's fall in what has come to be known as the Tulip Revolution did not lead, however, to democracy in Kyrgyzstan. Following about 2 years of transition, Kurmanbek Bakiyev, a former member of the Soviet-era elite and Akayev loyalist until 2002, managed to consolidate his power, installing a new, though brittle, authoritarian regime. Five years later, history repeated itself. In March 2010, a national Kurultai (traditional assembly) was called by civil society groups and key opposition parties to voice their demands. The violent repression of protests in the north-western city of Talas drove an even larger number of protesters to gather in the central square of the capital, violently clashing with police and taking control of key governmental buildings. Only 2 days after the start of the mass-based uprising, Bakiyev fled to his compound in the south of Kyrgyzstan (Collins, Reference Collins2011). Once again, however, the defeat of the authoritarian regime did not go hand in hand with democratization. Indeed, the country has remained authoritarian since 2011.

Kyrgyzstan represents an interesting example of a more general phenomenon tackled in the present paper: autocracy-to-autocracy transitions. These are defined here as moves between two non-democratic regimes marked by singular, characteristic events through which the fall of an autocrat and his or her ruling coalition, as well as the installation of new authoritarian rule, occur. In a debate on regime change that has largely remained focused on transformation to and from democracies, the emergence of an authoritarian regime following the defeat of a previously existing autocracy is a relatively understudied phenomenon. In order to begin filling this gap, this paper maps autocracy-to-autocracy transitions occurring between 2000 and 2015, that is, in the aftermath of the so-called third wave of democratization. The analysis identifies 32 regime changes across the world in countries with a population of over one million inhabitants ruled by an autocracy, of which 21 were transitions from one autocracy to another, with democracy emerging in only 11 cases. This means that after an authoritarian failure, a transition to a dictatorship was almost twice as likely as democratization.

The present paper proceeds as follows. The first section demonstrates why the empirical evidence of autocracy-to-autocracy transitions has been underestimated, while the second section provides a detailed discussion on varieties of authoritarianism and the main threats to authoritarian stability. The central part of the paper deals specifically with autocracy-to-autocracy transitions, highlighting three main findings: (a) just under half of autocracy-to-autocracy transitions saw the replacement of one competitive authoritarian regime with another; (b) surprisingly, most military coups do not install stable military dictatorships but competitive autocracies; and (c) the journey from one dictatorship to another is almost always set in motion by either a popular uprising or a military coup. The final section concludes.

Autocracy-to-autocracy transitions: An underestimated phenomenon

The transition from one autocracy to another is an understudied phenomenon. Although the debate on regime changes has recently experienced a significant U-turn from democratization to less clear transformations in the opposite direction, autocracy-to-autocracy transitions have remained on the periphery. For several decades, following the wave of democratization that swept across numerous regions of the world from the mid-1970s, scholars studied transitions from the authoritarian rule (O'Donnell et al., Reference O'Donnell, Schmitter and Whitehead1986) to democracy (Huntington, Reference Huntington1991), and problems of democratic consolidation (Linz and Stepan, Reference Linz and Stepan1996). Subsequently, with the end of this wave in the early 1990s, the persistence of authoritarianism and the more recent spectre of a democratic rollback have profoundly reshaped the debate. Attention has thus switched to changes within authoritarian regimes in a context of apparent continuity (Schlumberger, Reference Schlumberger2007; Way, Reference Way, Bunce, McFaul and Stoner-Weiss2010), authoritarian rule in particular places (Hill, Reference Hill2016), democratic recession or backsliding (for different views, see Diamond, Reference Diamond2015; Levitsky and Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2015; Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016; Mechkova et al., Reference Mechkova, Lührmann and Lindberg2017; Abramowitz and Repucci, Reference Abramowitz and Repucci2018; Waldner and Lust, Reference Waldner and Lust2018), democratic breakdown (Svolik, Reference Svolik2015; Tomini and Wagemann, Reference Tomini and Wagemann2018) and autocratization (Cassani and Tomini, Reference Cassani and Tomini2018).

In analysing cases of transition from one autocracy to another, this paper seeks to fill what appears to be a relevant gap in the literature on regime change. It starts from the few but important works that exist in this respect. Studying pathways from authoritarianism, for instance, Hadenius and Teorell (Reference Hadenius and Teorell2007: 152) highlight that ‘77 percent of transitions from authoritarian government resulted in another authoritarian regime’ between 1972 and 2003. In what is arguably the most accurate dataset on transitions from autocratic regimes, Geddes et al. (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014) expand their analysis to a much broader period, from 1946 to 2010. In contrast to these studies, however, the present article does not deal with all transformations from autocracy. Rather, it simply takes into account autocracy-to-autocracy transitions between 2000 and 2015. In so doing, it provides a more nuanced interpretation of the phenomenon, highlighting in particular some elements – for instance, the authoritarian contexts in which autocracy-to-autocracy transitions are more likely to occur and the modalities through which such a journey is often set in motion – that have remained underdeveloped in previous studies.

It is argued here that the underestimation of autocracy-to-autocracy transitions is the product of three main factors: the understanding of democracy as a continuous attribute; an overemphasis on elections; and the possibility that two or more authoritarian regimes might be concealed under a single autocratic spell.

To begin with, the use of datasets that qualify democracy as a continuous variable has to be mentioned. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) is a case in point here. Relying on data provided by V-Dem, Mechkova et al. (Reference Mechkova, Lührmann and Lindberg2017: 162) have recently concluded that ‘the average level of democracy in the world has slipped back to where it was before the year 2000’. In particular, considering that more countries experienced democratic backsliding than improvement during the past 5 years, the image of a decline in democracy has been proposed. In a rather similar way, using the aggregate 100-point scale measuring political rights and civil liberties of Freedom House (FH), Abramowitz and Repucci (Reference Abramowitz and Repucci2018: 128) have highlighted that around twice as many countries saw a decline in democratic terms as experienced an improvement in 2017. Whilst continuous approaches can say something about advancements and retreats in the level of democracy, they are less capable of grasping regime change transformation, thereby obscuring transitions from one authoritarian regime to another. The case of Pakistan is interesting in this regard. Both the level of political rights and the civil liberties of the country improved significantly in 2008, according to the report released by FH. However, what can be seen as an advancement from a view of democracy as a continuous trait was in regime change terms a transition from one autocracy to another, as will be shown below.

The second element is what might be understood as ‘electoral syndrome’. Coding a country as democratic as soon as substantially competitive and free elections are held would artificially multiply the number of democratizations and subsequent democratic breakdowns. To be clear, the problem does not rest with the use of poor-functioning datasets, but on the logic that underpins them. Being implicitly inspired by the so-called transitologist literature, most datasets have assumed the existence of a recurrent pattern in regime change from authoritarian rule. Through the lens of a linear and positivist interpretation of history, countries are indeed thought to move from autocracy to democracy, after the dismantling of the former, in an almost natural way. This might sound surprising; after all, it can be argued that in entitling their seminal work Transitions from Authoritarian Rule and not Transitions to Democracy, O'Donnell et al. (Reference O'Donnell, Schmitter and Whitehead1986) have suggested the uncertain character of transformations from authoritarian regimes. However, whilst there was an open-ended approach at the theoretical level, the single-case studies selected by O'Donnell et al. were rather homogeneous in exhibiting a single trajectory: from autocracy to democracy. Similarly, although conceiving a set of different transitions from authoritarian rule possible, transitologist scholars have analysed the process with categories that only fit democratization. It is thus unsurprising that transition is not considered complete when a new order (of whatever kind) is established, but rather, as specified by Morlino (Reference Morlino2011: 84), when ‘the first free, competitive, and fairly run elections’ are held. The strict overlap between the holding of the first multiparty and competitive elections on the one hand, and the installation of a democratic regime on the other, brings us to the key problematic aspect. To a significant extent, such a perspective was rather logical during the Cold War period. At that time, one-party regimes and pure military dictatorships were overwhelmingly dominant in the authoritarian world, whereas other forms of authoritarianism – variously termed – were rare (Hadenius and Teorell, Reference Hadenius and Teorell2007; Magaloni and Kricheli, Reference Magaloni and Kricheli2010; Kailitz, Reference Kailitz2013; Geddes et al., Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014). It is well-acknowledged that the situation has changed significantly since the late 1980s. Lacking support from the Soviet Union, several autocracies became dependent on Western aid for their own survival (Marinov and Goemans, Reference Marinov and Goemans2014; Levitsky and Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2015). As a tool to maximize its influence, however, the West began to promote multiparty elections in the rest of the world. Such a combination forced many authoritarian regimes to adopt democratic institutions in a context that remained authoritarian (Schedler, Reference Schedler2006; Levitsky and Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2010). In a similar scenario, the equation between the first substantially competitive elections and democratization has become weaker, if not misleading in several cases.

The case of Mauritania is revealing regarding this point. On 3 August 2005, President Ould Taya, who had run the country since December 1984, was overthrown by a military coup. Despite largely free, fair and competitive elections being held for both the national assembly and the presidency, Mauritania did not democratize. Less than 18 months after President Ould Abdallahi had been democratically elected, a new military coup halted the transition (N'Diaye, Reference N'Diaye2009). According to the dataset provided by Geddes et al. (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014), Mauritania was a democracy for just 1 year. From 2009 onwards, the country emerged as authoritarian once again. In such a way, what should be considered a transition from one dictatorship to another is instead initially consider democratization and then democratic breakdown. This helps explain why Geddes et al. (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014: 316) conclude that ‘autocratic breakdown leads to democracy more often now than in earlier decades’, empirically demonstrating that only six out of 23 falls of authoritarian dominations resulted in the installation of new autocracies in the 2000s. For similar reasons, Diamond (Reference Diamond2015) counts 25 breakdowns of democracy between 2000 and 2014, whilst in broadening the temporal horizon to the 1990s, Brownlee (Reference Brownlee2017) lists 40 such occurrences. The dismantling of an apparently great number of democracies is, however, the product of the misleading equation between authoritarian re(consolidation) or authoritarian transformation on the one hand, and democratic rollback on the other (Levitsky and Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2015).

Finally, the difficulties in recognizing the relevance of autocracy-to-autocracy transitions concern the possibility that a single continuous period of authoritarianism might actually ‘hide’ multiple, different autocratic regimes. As underlined by Geddes et al. (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014: 322), researchers usually ‘use data that code country-years as democratic or not and thus end up equating autocratic regimes with autocratic spells in empirical analyses’. In so doing, they leave out several episodes of authoritarianism breakdown, implicitly overestimating the stability of the authoritarian world and missing the numerical relevance of the journey from one dictatorship to another (for a similar argument, see also Wright and Escribà-Folch, Reference Wright and Escribà-Folch2012). The case of Egypt might help shed some light in this regard. Throughout its republican history, the country has remained authoritarian. In spite of this continuity, two successive autocratic regimes have governed Egypt without democratic interlude. The first continued until Hosni Mubarak was forced out of office in 2011. The second was instigated by Abdal Fattah al-Sisi's military coup in July 2013, and retains power today.

Varieties of authoritarian rule and its defeat

Given that this paper aims to map autocracy-to-autocracy transitions, this section seeks to highlight the variety of regimes in the non-democratic world and the different ways through which authoritarianism can be defeated. First, however, it seems important to separate democracy and autocracy. Interpreting democracy as a dichotomous variable (Sartori, Reference Sartori1987), it is here deemed as being composed of two fundamental dimensions, participation and contestation, which include four key attributes: (a) full adult suffrage; (b) free, fair and competitive elections; (c) freedom of speech, association and information; and (d) the absence of non-elected officials (Dahl, Reference Dahl1971).

All regimes that do not meet such criteria are authoritarian. This does not mean, however, that non-democratic regimes are a homogeneous group. Indeed, they may have legislatures, parties and even recurrent elections that mask the actual authoritarian nature of the regime. They are sometimes built around a super-powerful ruling party and on other occasions are the product of a collegial military junta. It is precisely the fact that autocracies vary across several dimensions that has forced scholars, in order to propose a synthetic typology, to balance incommensurably different aspects of authoritarian rule, ultimately developing categories that are neither mutually exclusive nor collectively exhaustive (Svolik, Reference Svolik2012; Wahman et al., Reference Wahman, Teorell and Hadenius2013). Addressing such a problem is not an easy task, however, and the concrete risk is an astonishing multiplication of categories with a few cases each and the consequent impossibility of generalizing beyond a single country. In identifying four conceptual dimensions of authoritarian politics and distinguishing between three and six categories for each, Svolik (Reference Svolik2012), for instance, establishes 360 possible combinations. In such a way, we might know a lot about a single case, but much less about whether a particular authoritarian regime type makes a difference.

In the post-Cold War period, the even greater heterogeneity displayed by non-democratic regimes has been matched by a correspondingly rich and variable array of typologies. Linz and Stepan (Reference Linz and Stepan1996) have proposed (beyond the classic distinction between authoritarianism and totalitarianism) post-totalitarian and sultanistic regimes, whilst the diffusion of multiparty elections has stimulated the proliferation of authoritarianism with adjectives ranging from electoral (Schedler, Reference Schedler2006) to competitive (Levitsky and Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2010). An important turning point in the debate was Geddes’ (Reference Geddes1999) seminal article in which she distinguished between personalist, military and single-party dictatorships. Primarily building on such insights, Hadenius and Teorell (Reference Hadenius and Teorell2007) have identified five main autocratic regime types: monarchy, military, no-party, one-party and limited multiparty; Gandhi (Reference Gandhi2008) has highlighted three distinct forms of non-democracy: royal, military and civilian rule; while Magaloni and Kricheli (Reference Magaloni and Kricheli2010) have discerned military, monarchic, single-party and dominant-party regimes. Drawing attention to the dimension of legitimization, Kailitz (Reference Kailitz2013) has instead identified electoral autocracy, communist ideocracy, one-party autocracy, military regime, monarchy and personalist autocracy.

From Cheibub et al. (Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010) perspective, autocracies can be distinguished according to the person who effectively rules. If the head of government bears the title of King and has a hereditary successor and/or predecessor, the non-democracy is a monarchy, whilst the case of a current or past member of the armed forces at the head of the polity describes a military dictatorship. All other autocracies are civilian. Even if clear and synthetic, the typology has its own problematic aspects. First, as shown by post-1977 Gaddafi's Libya, the person who actually rules might not be the person who formally governs. Second, not all regimes with a former member of the armed forces at the head of the government are necessarily military dictatorships. Finally, the civilian regimes category is too generic and broad, clustering together significantly dissimilar experiences.

Some of these drawbacks have been addressed by Wahman et al. (Reference Wahman, Teorell and Hadenius2013). Drawing inspiration from Hadenius and Teorell's (Reference Hadenius and Teorell2007) earlier work, they set three different modes of accessing and maintaining power at the core of their typology: hereditary succession, the actual or threatened use of military force, and popular elections. The regime types that correspond to these three modes are monarchies, military dictatorships and electoral regimes. The latter is, in turn, split into multiparty regimes (when multiparty competition is allowed), one-party regimes (when participation in elections is restricted to the government party) and no-party regimes (when no party is allowed to run) (Wahman et al., Reference Wahman, Teorell and Hadenius2013). Even in this case, theoretical and empirical issues exist. As correctly underlined by Kailitz (Reference Kailitz2013), whilst the usual mode of power maintenance in party autocracies is not popular election, the actual or threatened use of force seems a more general aspect of all kinds of autocracy rather than a specific feature of military dictatorships. Moreover, as shown by Tito's Yugoslavia between 1946 and 1979, there are also one-party regimes in which there are no elections. Finally, no-party regimes appear as a residual category, with few empirical manifestations, especially in the last decades.

In contrast, Geddes et al. (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014: 315) focus on the concept of the leadership group, that is, ‘the small group that actually makes the most important decisions’. In so doing, six main types of autocracy are highlighted: dominant-party, military, personalist, monarchic, oligarchic and indirect military. Moreover, it is also possible to have hybrid combinations of the first three types. Such a typology is not immune from questionable aspects either. On the one hand, the limited relevance of the last two categories stimulated Geddes et al. (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014) to restrict their empirical analysis to the first four types. Since the dismantling of the apartheid regime in South Africa in 1994, for instance, no other country in the world has qualified as an oligarchy, suggesting that the category remains relevant only for scholars who want to conduct history-based research. On the other hand, it is difficult to understand what distinguishes in substantial terms an indirect military from a hybrid combination of military and personalism or military and dominant-party. Finally, personalism or sultanism seem more a continuous trait than an all-or-nothing affair, therefore casting doubt on the appropriateness of identifying an ad hoc category in this regard.

The present paper does not aim to propose a completely new typology of non-democratic regimes that might substitute or improve those that already exist. The approach used here is instead pragmatic. It seeks to provide an updated typology that, drawing from previous studies, might be useful to study a phenomenon – autocracy-to-autocracy transitions – that is both peculiar and, in this paper, temporally limited.

This paper identifies varieties of authoritarianism through the use of two dimensions: hierarchical and asymmetric. Put differently, one dimension is more relevant than the other, and the second dimension applies only to a specific category. The latter is thus split into subsets that can be re-aggregated if necessary (for a similar approach, see Brownlee Reference Brownlee2009).

In a way that resembles many of the previously presented typologies, and especially that proposed by Geddes et al. (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014), the first dimension revolves around the ruling coalition, that is, the alliance of political forces and social groups that effectively runs the country. To be more precise, it refers to whether control over the polity is in the hands of a royal family (monarchy), the armed forces (military dictatorship), civilians constrained by the armed forces (civil-military regime) or autocratic civilians (civilian autocracy). This paper defines monarchies those countries in which power is not only passed from father to son, but such passage is regulated by accepted practices or the constitution (Syria and North Korea are therefore excluded). Military dictatorships comprise both those authoritarian regimes led by the military as an institution (for instance, Argentina between 1976 and 1983) and those autocracies in which the head of government is a professional soldier who has enjoyed overt military support and involvement, as exemplified by Musharraf's Pakistan from late 1999 until 2008. If power is concentrated in neither the royal family nor the armed forces, scholars should enquire whether the military directly and significantly affects politics even though the government is formally led by a civilian. If this is the case, the autocracy in question is a civil-military regime. Post-2015 Myanmar is a good example here. Despite San Suu Kyi's party victory in the 2015 elections, the military, according to the constitution, enjoyed 25% of reserved seats in the parliament and autonomy over the appointment of three key ministries.

In all other cases, the country should be considered a civilian autocracy. In such a broad camp, it is hence important to make distinctions through the introduction of the second dimension, that is, whether multiparty elections are held or not, and if the former is the case, their degree of competitiveness. As is almost unanimously recognized, the introduction of democratic procedures in contexts that remain stubbornly authoritarian has been the single most important transformation in authoritarian politics in recent decades.Footnote 1 Thanks to the second dimension, it is possible to discern between one-party regimes where only one legal party (either formally or de facto) is allowed to operate, and electoral authoritarianism, which is in turn divided into hegemonic and competitive authoritarian regimes. In the former, the degree of openness and competitiveness of elections is so limited that there is no uncertainty about their outcome, whereas in the latter the opposition can compete in a relatively meaningful way for executive power (Levitsky and Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2010). Although such a distinction is often difficult to operationalize, it seems key to disentangling the broad category of electoral authoritarianism. Pre-2003 Georgia and pre-2011 Egypt are, in this regard, good examples. The last 3 years of Shevardnadze's rule were marked by visible signs of the regime's vulnerability. The implosion of the ruling party paved the way for the astonishing results of the 2002 Georgian local elections, in which former Minister and then President Mikheil Saakashvili, who had defected to the opposition only shortly before, became the Mayor of the capital, Tbilisi (Welt Cory, Reference Bunce, McFaul and Stoner-Weiss2010; Bunce and Wolchik, Reference Bunce and Wolchik2011). Similar spaces for opposition forces or leaders were simply unthinkable in Mubarak's Egypt (De Smet, Reference De Smet2016). This does not mean that significant protest movements did not emerge in the years that preceded the fall of the authoritarian regime – in fact the reverse is true – yet the opposition could not attain the upper hand, or at least mount a serious challenge to the regime, through institutional channels.

To conclude, six distinct forms of the non-democratic regime are highlighted: monarchies, military dictatorships, civil-military regimes, one-party regimes, hegemonic authoritarianism and competitive authoritarianism. The last three categories are civilian autocracies and the last two electoral authoritarian regimes.

Another important aspect concerning authoritarian regimes revolves around the conflicts that might jeopardize their own stability. Although non-democratic regimes vary considerably in terms of lifespan, they all face some kind of threat to their rule. Nevertheless, in sharp contrast to the previous discussion on how to classify authoritarian regimes, a broad consensus has emerged among scholars concerning the two main threats that autocracies must overcome to survive in power. The first derives from within the ruling class, whilst the other comes from society (Gandhi, Reference Gandhi2008). According to Magaloni and Kricheli (Reference Magaloni and Kricheli2010), autocrats face the constant dilemma of how to effectively distribute resources between the masses and the elites. Similarly, Svolik (Reference Svolik2012) believes that authoritarian dominations suffer both the problem of control of the masses and of power-sharing within the ruling coalition. In a more complex way, Schedler (Reference Schedler2013) distinguishes vertical threats (from the masses), lateral threats (from within the elite) and external threats (from international actors). Although the international dimension is certainly an important element, it is not taken into account in this paper. In its peaceful manifestation – that is, economic sanctions, opposition support and the like – it is unlikely to work as the main (let alone only) factor that brings down an authoritarian regime. In contrast, war has the potential to violently dislodge a dictatorship from the outside. However, in the aftermath, a foreign occupation by the winning external power(s) or some kind of internal conflict represents the two most likely scenarios. Although non-democratic, these circumstances cannot meaningfully be considered authoritarian either.

When considering a lateral threat, it is thus important to distinguish whether the menace comes from the army or another institutional actor. The former case is a military coup, whereas the latter is a palace putsch. Vertical threats can be split into two subgroups as well. On the one hand, there is the victory of the opposition in elections; on the other, a popular uprising, either peaceful or violent. The transition from one autocracy to another is therefore set in motion by one of these four catalysts: a military coup, a palace putsch, an opposition victory in elections or a popular uprising.

Autocracy-to-autocracy transitions

Building on the previously discussed theoretical framework and using the dataset provided by V-Dem, all countries with a population above one million inhabitants have been coded as either democratic or non-democratic for the whole period between 2000 and 2015. As suggested by Bogaards (Reference Bogaards2012), the recurrent problem of going from degree to dichotomy when scholars use interval indexes such as V-Dem can be solved by moving beyond aggregate scores and using values on individual indicators. To qualify as a democracy, and following an almost unanimous consensus in the literature (Dahl, Reference Dahl1971; Wahman et al., Reference Wahman, Teorell and Hadenius2013; for a different approach see instead Cheibub et al., Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010), regimes must score a full 1 – on a scale from 0 (minimum) to 1 (maximum) – on universal suffrage and elected officials.Footnote 2 The other two key dimensions, that is, elections and civil liberties, have been disaggregated into two further dimensions each (free and fair elections and multiparty elections for the former; freedom of association and freedom of expression for the latter) and evaluated through the ratings provided by experts. Even if objective measures remain preferable in theoretical terms, the question of whether elections are free and fair (for instance) necessarily rests on some kind of evaluation. Moreover, considering the Bayesian measurement model developed by V-Dem, there are grounded expectations that coder errors have been minimized and comparability across countries and over time rendered feasible (Lührmann et al., Reference Lührmann, Lindberg and Tannenberg2017).

Democratic countries must have de facto free and fair elections and multiparty elections, as indicated by a score equal to or above 3,Footnote 3 and substantial freedom of expression and freedom of association, as testified by a result equal to or above 0.75.Footnote 4 Positive scores on the six attributes indicated here are individually necessary and together provide sufficient conditions to classify a regime as democratic. Moreover, to view democratization as a long-lasting process (Tilly, Reference Tilly2007; Tomini and Wagemann, Reference Tomini and Wagemann2018), the minimum standards required to code a country as democratic have to be met in at least two consecutive general elections for the executive.Footnote 5

Although more stringent criteria are used here than in many other studies, 71 countries were found to be democratic in 2015 and 62 for the whole period between 2000 and 2015. The former signifies that slightly more than 45% of countries with a population of over one million were democratic in 2015.

Taking into consideration only authoritarian regimes and using a dataset of political leaders called Archigos (Goemans et al., Reference Goemans, Gleditsch and Chiozza2009), which codes the identities of leaders in 164 countries around the world and covers (with its latest web version) the period until 2015, all cases of leadership change are identified. The next step is to select a subset in which mere leadership change that did not result in a transition from an authoritarian regime to another is excluded. Such an issue is theoretically clear, but practically thorny. In accordance with the definition provided in the Introduction, an autocracy-to-autocracy transition is recorded when the defeat of an incumbent autocrat and his or her ruling coalition determines the emergence of a new authoritarian regime. This process may be the product of either a coerced dismissal – a popular uprising, military coup or palace putsch – or the victory of the opposition in elections. However, in the latter circumstance, to be deemed an autocracy-to-autocracy transition a country is additionally required to experience an outright change in the formal and informal institutions through which power is exercised. In other words, a different type of autocracy must emerge. Such a supplementary requirement aims, first and foremost, to discard mere leadership turnovers achieved through elections, such as the case of Kenya in 2002 (Levitsky and Way, Reference Levitsky and Way2010). An outright change in regime type is not instead necessarily demanded as a condition of an autocracy-to-autocracy transition when an incumbent ruling elite is toppled through a coerced dismissal.

In contrast, all of those cases in which gradual and fine-grained dynamics resulted in intra-regime change are not taken into consideration (see Brownlee, Reference Brownlee2009). Similarly, military coups that only aim to secure extra-constitutional continuity – as exemplified by the 2005 armed forces-led installation of Faure Gnassingbé as Togolese president following his father's death – are omitted as well. Even more significantly, the breakdown of authoritarian regimes that brought about civil wars (Libya and Yemen in 2011, Central African Republic in 2013) or foreign occupations (Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003) or that were established in the wake of one of these two situations (Burundi in 2003–2005, Afghanistan and Iraq more recently) are also not considered. In fact, and as consistently demonstrated in the literature, civil wars and foreign occupations cannot be considered manifestations of authoritarian rule (Svolik, Reference Svolik2012; Wahman et al., Reference Wahman, Teorell and Hadenius2013; Geddes et al., Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014).

All in all, this paper counts 32 cases of autocratic breakdown in countries with a population of over one million inhabitants between 2000 and 2015. Only in 11 instances did they result in democratization. In the other 21 cases, the fall of autocracy was followed by the installation of a new dictatorship, rendering such a scenario almost twice as likely as democratization. All cases of autocracy-to-autocracy transitions are classified in Table 1, in which previously existing regimes, their heirs and the type and duration of the transition are reported. Three countries (Guinea-Bissau, Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine) appear twice.

Table 1. Autocracy-to-autocracy transitions (2000–15)

Source: My own elaboration.

More than half of the former regimes were competitive authoritarianism. Adding the five hegemonic authoritarian regimes, electoral authoritarianism accounts for more than three-quarters of all cases. Whilst a high concentration of cases of a specific subtype would certainly be problematic were our aim to classify all non-democratic regimes, it emerges as a significant finding here. Indeed, it shows that the phenomenon of interest – autocracy-to-autocracy transitions – often took off in a context characterized by illiberal multiparty competition. Tellingly, beyond electoral authoritarianism there are only five cases. Two regimes (Pakistan and Myanmar) were military dictatorships, while Nepal in 2006 was a recently formed monarchy. Finally, pre-2003 Guinea-Bissau and Thailand between 2006 and 2014 were civil-military regimes. In the former country, President Kumba Yalá, who had been elected in largely free and fair elections after 9 months of internal military conflict in 1998–99, was curtailed in his decisions by the signed agreement between the previous existing interim government and the military junta, which ascribed to General Ansumane Mané the right to stand above the presidency (Embaló, Reference Embaló2012). In Thailand, in contrast, the military-sponsored 2007 Constitution scrapped the 2000–06 elected Senate in favour of an only partially elected chamber in which about 10% of appointed senators had to be former military members (Chambers, Reference Chambers2010). The lack of one-party regimes in our sample is the second interesting finding. In no case was a journey from one autocracy to another started in such a context. Even if the conclusion remains tentative, especially in light of the enormous shrinking of this regime category after the end of the Cold War, one-party regimes seem to constitute stable and robust forms of authoritarianism. This insight is strongly supported by the fact that all 11 cases of successful democratization registered between 2000 and 2015 emerged from regimes that were not one-party dictatorships (for a similar argument, see also Geddes, Reference Geddes1999; Smith, Reference Smith2005; Brownlee, Reference Brownlee2009).

The numerical relevance of competitive authoritarianism is even more evident once our focus switches to newly established autocracies. The fact that 16 post-transition countries were regimes of this sort and that, as shown by Table 2, slightly fewer than half of all transitions were a journey from one competitive authoritarian regime to another after the previous existing autocracy was defeated represents the most impressive finding.

Table 2. The journey from one autocracy to another (2000–15)

Source: My own elaboration.

As largely expected, there are no instances of one-party regimes in newly established autocracies, whereas two transitions (in Egypt and Thailand) brought about the emergence of military dictatorships. Following the 2014 coup, the Thai military-installed itself at the apex of the political system and appointed four of its own members as Prime Minister and to other key posts (Baker, Reference Baker2016). General Prayut Chan-o-cha did not even try to legitimize his position as Prime Minister through flawed elections, and it remains unclear at the time of writing whether the planned February 2019 parliamentary elections will be effectively held; after all, this is nothing less than Chan-o-cha's sixth promised polling date. Although the position of General al-Sisi as president of the country has already been ‘legitimised’ twice by some sort of electoral competition (in 2014 and 2018), Egypt does not differ significantly from Thailand. Not only are the Ministry of Defence, of Interior and other three Ministries led by officials, but the penetration of the army in every sphere of society is so astonishing that the degree of militarization of political life is possibly even greater in today's Egypt than during Nasser's military regime (Springborg, Reference Springborg2018).

The final two cases are the civil-military regime that has taken shape in Myanmar since San Suu Kyi's party victory in the 2015 parliamentary elections and the short-lived monarchy in Nepal. After King Gyanendra dissolved the parliament and cancelled local elections in 2002, he concentrated all executive power in his hands in 2005, thereby establishing a monarchical dictatorship (Gellner, Reference Gellner2007).

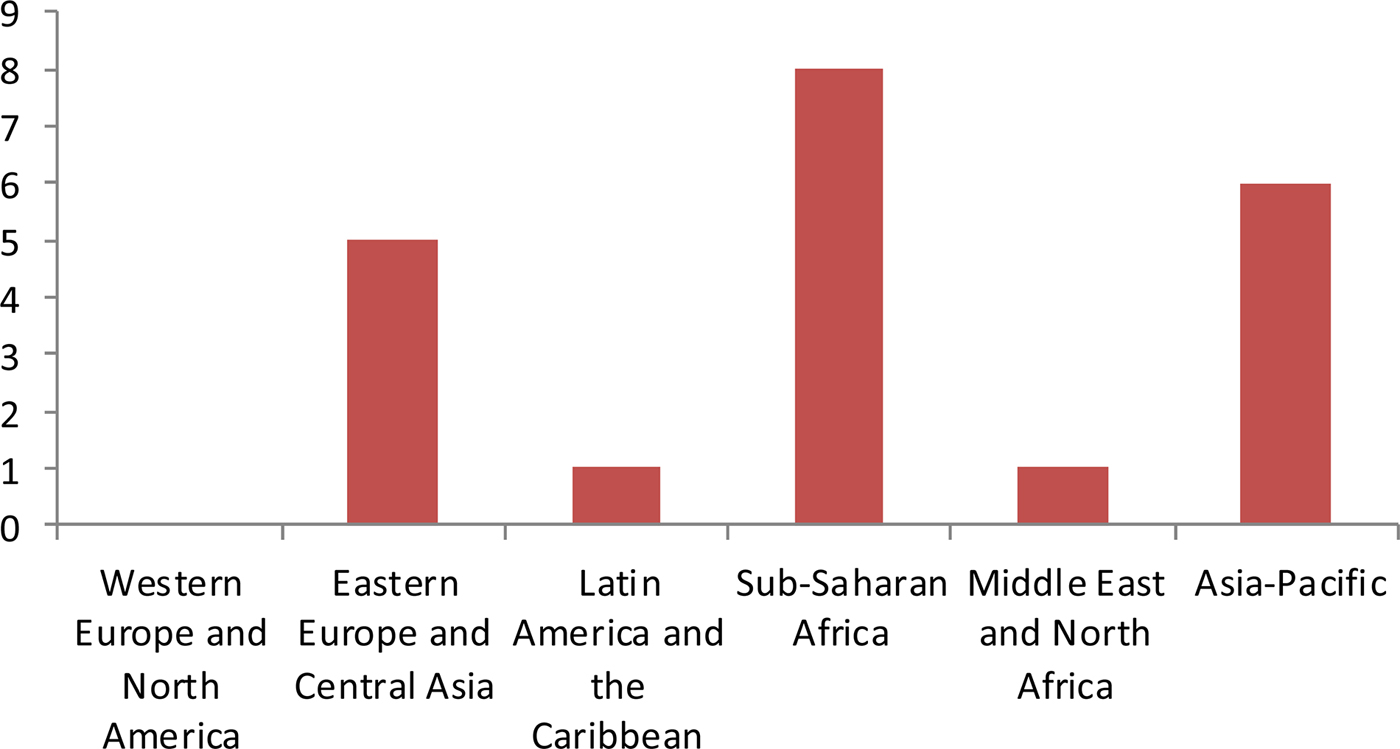

As shown in Figure 1, autocracy-to-autocracy transitions between 2000 and 2015 are spread unevenly across the globe.

Figure 1. Autocracy-to-autocracy transitions across the world, 2000–15.

To some extent, this should not come as a complete surprise. After all, a transition from one autocracy to another is logically impossible in democratic contexts. In this regard, finding no empirical manifestations of the phenomenon in Western Europe and North America is simply obvious. In a similar way, it should not be astonishing to encounter only one case – Haiti – in Latin America and the Caribbean. Whilst there are signs of a diffuse democratic malaise and authoritarian regimes are not completely absent, the region was largely democratic in the period analysed, especially in the early years. Such a scenario reduces the likelihood of a transition from one authoritarian regime to another. Similarly, in those regional contexts in which authoritarian regimes are stable, autocracy-to-autocracy transitions should represent rare occurrences. The Middle East and North Africa, in spite of the Arab uprisings, strongly confirm such an expectation, with the exception only of Egypt. In contrast, almost all those regions that were transitions from one authoritarianism to another were concentrated in Eastern Europe and Central Asia (five cases), Asia-Pacific (six cases) and, especially, sub-Saharan Africa (eight cases). These three contexts were the main theatres in which the defeat of authoritarian regimes in the wake of the so-called third wave of democratization produced greater instability, a low degree of institutionalization and new and brittle autocracies, rather than stable and well-functioning democratic regimes.

The catalysts for transition

As made clear in Figure 2, the overwhelming majority of autocracy-to-autocracy transitions were the product of either a popular uprising or a military coup.

Figure 2. The way in which autocracy-to-autocracy transitions were set in motion, 2000–15.

Only three cases did not follow one of these two paths. On the one hand was the palace putsch in Nepal and the consequent transformation of a competitive authoritarian regime into a monarchy; on the other were the two victories of opposition forces in elections. Tellingly, the latter took place in two military regimes: Pakistan in 2008 and Myanmar in 2015. These two cases should not be seen as the dismantling of dictatorships, but rather as partial and relatively smooth disengagements of the armed forces from daily politics. The non-coerced ending of the two regimes is coherent with a broad literature that has seen in the corporate interests of the military the primary factor that creates factions and splits within its leadership, eventually advising a return to the barracks to protect the military as an institution (Geddes, Reference Geddes1999; Marinov and Goemans, Reference Marinov and Goemans2014). In such a regard, institution-building and political institutionalization represent strategies that military regimes can use to weaken internal contrasts and maintain some relevant grip on power (Croissant and Kamerling, Reference Croissant and Kamerling2013). Although the transitions were the product of the victory of opposition forces in parliamentary elections, in Pakistan and Myanmar the holding of largely free and fair elections was indirectly produced by diffused mobilizations. In spite of these similarities, Pakistan has emerged as a competitive autocracy in which the long-lasting influence of the military is almost entirely indirect, whereas post-2015 Myanmar is a civil-military regime where the civilian leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi is severely limited by the armed forces (Barany, Reference Barany2018). It would appear that two main elements exist that can explain the different trajectories. First, Myanmar was dominated by a military junta from 1988 to 2015. In contrast, Pakistan did not show any kind of collegial military government, but rather approximately 8 years of a dictatorship led by a professional officer who enjoyed support from the military as an institution. Put differently, the longevity and penetration of military rule were certainly more relevant in Myanmar than in Pakistan.

Moreover, in contrast to the negotiated exit of the Pakistani military from power in the wake of growing pressure from some sectors of society (especially judges, lawyers and other middle-class professionals), the violent crushing of the 2007 Buddhist monk-led uprising allowed Myanmar's military junta to dictate its own conditions (Croissant and Kamerling, Reference Croissant and Kamerling2013; Shah, Reference Shah2014). Through the approval of a new constitution, the military reserved for itself 25% of the seats in the National Assembly, full autonomy over budgeting and appointments in the Ministry of Defence, Home Affairs and Border Affairs, and the authority to nominate six of the 11 members of the powerful National Defence and Security Council (Barany, Reference Barany2018; Dukalskis and Raymond, Reference Dukalskis and Raymond2018). In contrast, there are no reserved seats in the Pakistani parliament for military officers. More significantly, the whole cabinet – even the sensitive Ministry of Defence – is completely civilian. The continued importance of the influence of the military in Pakistan is therefore indirect (Shah, Reference Shah2014).

Returning to the most common ways in which countries transitioned from one autocracy to another, Figure 3 helps shed some light on the phenomenon.Footnote 6

Figure 3. Autocracy-to-autocracy transitions unleashed by a popular uprising or a military coup, 2000–15.

There were eight occurrences of the popular uprising in six countries: Georgia 2003, Ukraine 2004, Kyrgyzstan 2005, Nepal 2006, Kyrgyzstan 2010, Egypt 2011, Ukraine 2013–14 and Burkina Faso 2014.Footnote 7 Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan are thus present twice. In all cases except Nepal the outbreak of radical, mass-based protests emerged in contexts of electoral authoritarianism, whether hegemonic or competitive. Leaving the peculiar case of Egypt aside – where, after a prolonged and uncertain transition, a new popular movement was exploited by the army, leading to the installation of a military dictatorship – all popular uprisings resulted in competitive authoritarianism. It is also interesting to note that in six countries elections go some way towards explaining the fall of the previous regime, illustrating how they can provide oppositions with an opportunity. In particular, the conduct of blatantly stolen elections was the key catalyst for the emergence of broad opposition coalitions in all post-Soviet countries during the so-called Colour revolution. The scenario was more complex in Nepal and Egypt, where although opposition forces and disgruntled citizens did not take to the streets in a clear response to fraudulent elections, it seems clear that recent significant frauds at the ballot box provided an impetus to mobilize a few months later. In Burkina Faso, it was instead Compaoré’s attempt to propose a constitutional change to extend presidential term limits that spurred mass protests. In sharp contrast, neither the uprising in Kyrgyzstan in 2010 nor the upheaval in Ukraine in 2013–14 had anything to do with elections. The former was the product of a coming together of different civil society groups and opposition forces in the informal institution of a popular assembly (Kurultais), while the latter was unleashed by President Yanukovych's decision not to sign the European Union (EU) Association Agreement in November 2013. Aside from the two Kyrgyz upheavals, which emerged first in rural and small towns, the other six cases were urban-based revolts in which the role of the capital city emerged as critical. This does not mean that there were protests only in Kathmandu or Ouagadougou. However, the emergence of mass protests in the capital, with the main square constantly occupied by demonstrators and transformed into a city of tents (as happened in Kyiv twice as well as in Cairo), signalled the immediate breakdown of routine governance, putting the regime to the test.

Not all uprisings were an impressive display of the strength of the masses. Only the two Ukrainian uprisings (and especially the first) were close to reaching the record high of at least one million protesters who gathered in Cairo and throughout the country. In Nepal and Burkina Faso, significant and radical mass-based protests were reported as well, but these failed to escalate to such a magnitude. In Kyrgyzstan, even considering the small population of the country, the peak of 15,000 protesters during the 2005 events remained rather modest, while the Georgian uprising (which was often seen as an instance of the strength of popular will) exceeded 20,000 people in the streets only after Shevardnadze's resignation. The numbers of the 2010 Kyrgyzstan uprising were even less significant. It must be noted that in all eight cases, defections from the armed forces or their unwillingness to do the dirty work of keeping the autocrat in power eventually proved decisive.

Ten autocracy-to-autocracy transitions were unleashed by a military coup: Central African Republic in 2003, Guinea-Bissau in 2003, Haiti in 2004, Mauritania in 2005, Bangladesh in 2007, Guinea in 2008, Madagascar in 2009, Niger in 2010, Guinea-Bissau in 2012 and Thailand in 2014.Footnote 8 In most cases, the intervention of the army took place in contexts characterized by some form of illiberal multiparty competition, whereas in two instances (Guinea-Bissau in 2003 and Thailand in 2014) the existing regime was a civil-military dictatorship. The most surprising element, however, concerns the end point of the trajectory. In nine out of 10 cases, the following autocracy was not a military dictatorship. With the mere exception of Thailand, all of the other autocracy-to-autocracy transitions unleashed by a military intervention into politics did not install a military regime. This strongly confirms Marinov and Goemans’ (Reference Marinov and Goemans2014) finding that post-Cold War coups tend to lead to competitive elections much more than in the past.

Even if all of the other cases were instances of civilian autocracy (and often competitive authoritarianism), it is important to draw a distinction between two rather different scenarios. First of all, there is what should be called ‘personal transitions’ (N'Diaye, Reference N'Diaye2009: 135). Following a successful military coup, the leading figure within the armed forces might take the opportunity to exploit the situation, presenting himself or herself in civilian dress and winning almost completely free and fair multiparty elections. In such cases, it is often difficult to assess the real grip of the military on power. Officially the presidency and the cabinet are entirely civilian, yet the officer-turned-president clearly relies (especially in the first years) on the military infrastructure to garner consensus and to govern in settings characterized by poorly functioning state structures. At the same time, in his or her attempt to achieve room to manoeuvre, the president tries to build new channels of political mobilization and power. Such attempts are often resisted by the military. Planned or real (either failed or successful) military coups are a strong confirmation in this regard. François Bozizé in the Central African Republic (CAR) in 2003–13 and Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz in Mauritania from 2008 onwards are two key cases in point. Guinea, on the other hand, represents a failed personal transition. Having seized power just hours before the death of former dictator Lansana Conté in December 2008, the army captain Moussa Dadis Camara announced that he would not run in the upcoming elections. In April 2009, however, Camara made a U-turn. Despite this, following the military-led massacre of at least 157 peaceful civilians in late September, Camara was shot in mysterious circumstances and treated in Morocco. The failure to achieve a personal transition pushed Guinea towards the second scenario, which according to Marinov and Goemans (Reference Marinov and Goemans2014: 803) is a ‘guardian coup’: a situation in which the military takes power to oust an erratic and inept civilian leadership and then rapidly returns the country to elections after reforming the system. Guinea-Bissau in 2003 and 2012, Bangladesh in 2007, Madagascar in 2009 and Niger in 2010 are examples of such a scenario. In contrast to military coups that lead to pure military autocracies, the clampdown on political forces and civil society is undoubtedly milder in guardian coups. In Niger and Guinea-Bissau in 2012, for instance, demonstrations were not tolerated, but political parties were allowed to operate. Moreover, in sharp contrast to personal transitions, the post-coup electoral competition did not see the participation of former military officers. Unsurprisingly, all guardian coups – often following an interim government led by technocrats or internationally endorsed figures – resulted in competitive authoritarianism. In many respects, Haiti in 2004 was a similar case. However, Jean-Bertrand Aristide's regime was not overthrown by a classic military coup, but by an armed insurgency that began in the port city of Gonaïves by a local gang, later to be joined by former members of the defunct Haitian military. Finally, it is interesting to note that all military coups took place in countries in which the armed forces have historically played an important role. In Thailand, for instance, there have been 19 coups since the abolition of absolute monarchy in 1932, whereas Niger has spent 22 of its 58 years as an independent country under military rule.

Conclusion

This paper has focused on autocracy-to-autocracy transitions. There were 21 occurrences of such phenomena between 2000 and 2015. Considering that the defeat of an authoritarian regime led to democracy in only 11 cases in this period, the installation of a new authoritarian regime after the fall of a dictatorship was almost twice as likely as democratization. In spite of their frequency and relevance, autocracy-to-autocracy transitions have remained a largely understudied form of regime change. Thus, the main scope of the present paper has been to start filling the gap in a body of literature that remains overwhelmingly focused on transitions to and from democracy. In particular, three main factors have been identified as crucial to explaining the underestimation of autocracy-to-autocracy transitions. First, qualifying democracy as a continuous variable enables the identification of democratic advancements and retreats but says little about regime change. Second, the emergence of democracy, especially in the post-Cold War period, is a complex and long-lasting process that cannot be reduced to the holding of the first mainly free, fair and competitive elections. Finally, a unique autocratic spell can actually be composed of multiple authoritarian regimes.

Providing an updated typology of non-democratic regimes and discussing the main ways through which authoritarian regimes can be defeated, this paper has identified 21 autocracy-to-autocracy transitions. While the uneven geographical distribution of the cases – being almost entirely concentrated in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Asia-Pacific and sub-Saharan Africa – does not come as a surprise, other findings were less predictable. First, more than three-quarters of the 21 transitions initiated in situations characterized by minimally pluralistic and minimally competitive elections resulted in similar contexts. Even if hegemonic autocracies were significantly more present in the years prior to the start of the transition than after, the general lesson is that the journey from one autocracy to another is largely an affair related to electoral (and specifically competitive) authoritarianism. This seems to point to the unstable character of many poorly functioning autocracies, especially in the Third World, which is too brittle to become fully stable authoritarian regimes and are simultaneously incapable of undergoing a successful process of democratization. They therefore tend to pass from one form of authoritarian domination to another.

Second, despite the numerous different threats to the stability of authoritarian rule, almost all autocracy-to-autocracy transitions between 2000 and 2015 were set in motion by either a military coup or a popular uprising. This finding does not contradict a broad literature that highlights the strictly anti-democratic character of the armed forces and the limited likelihood that a transition launched by mass protests to gain control over ruling elites even just momentarily might lead to democracy. Interestingly, the only two cases in which an autocracy-to-autocracy transition was the product of opposition victory in elections occurred in the military regimes of Pakistan and Myanmar. As argued, these were not instances of the dismantling of dictatorships, but rather pacted (and in the case of Myanmar, partial) disengagements of the army from daily politics.

Third and finally, and as paradoxical as it might sound, with the exception of the Thai case, no military coups installed a military domination. This confirms what other scholars have noticed elsewhere concerning the frequent tendency of the armed forces to stage what should be regarded as guardian coups in the post-Cold War period. That is, military coups that aim to remove an erratic and inept autocratic civilian regime and then return the country to new elections in a context that remains, nevertheless, authoritarian.

Author ORCIDs

Gianni Del Panta, 0000-0002-6914-4462.

Acknowledgements

I thank Jonathan Hill, Gerrit Krol, all the participants in this special issue and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. In particular, I would like to mention the two guest editors, Andrea Cassani and Luca Tomini. Any errors or omissions remain, of course, mine.

Financial support

The research received no grants from public, commercial or non-profit funding agency.