Introduction

In 1845, the banker Damodar Dass of Srirangapatna loaned a large sum of money to Maharaja Krishnaraja Wodeyar III of Mysore. For the next seven decades, until the unpaid debt was turned into a public charity, the multiple claims of Damodar Dass's heirs (including four women) to this inheritance vexed the colonial state and, especially after 1881, the Mysore government, producing a rich archive.

Tracing the seven-decade journey of a royal debt (which I narrate in the first section of this article) leads us as much through the profoundly transformative moment in the politico-economic order of princely Mysore as through the more uncertain domains of the divided and dislocated subjecthood of women. What unites the two ends of this broad, if tapering, spectrum—at one end, represented by the power and flamboyance of a king who long denied the diminution of his authority, and, at the other, represented by the whispers and pleas of women who were everywhere denied their legal personhood—other than the richness of the archive and the loquaciousness of the state and law, even its silences?

In order to make sense of these entangled and asymmetrical histories of debt, honour, and complex questions of legality, we must follow the intentions of the state up to a point. However, the prodigious output of the state/law, marked by an ‘ideological construction of gender that keeps the male dominant’ permits us to undertake a different investigation.Footnote 1 This archive can, while speaking of the rights of women, be made to reveal a different kind of female personhood, showing us histories that even the epistemic violence of colonialism did not succeed in completely erasing.Footnote 2 This article therefore references debates among feminist scholars about how to measure silence, assess agency, and evaluate women-as-sign in relation to a voluminous archive that features women and their rights.

In the foreground of the archive are the politico-legal dilemmas posed by the transition from direct to indirect British rule in Mysore. The extraordinary anxiety about the accumulated debts of the Maharaja of Mysore, and the Damodar Dass loan in particular, preoccupied colonial officials for three full decades after the British gained direct control of the state in 1832. The case serves as a prism through which we can see all the traumas of the Maharaja's transition as he went from being a relatively autonomous princely authority to a mere pensioner of the East India Company, before a sharp shift restored him to kingship under the firm control of the Mysore bureaucracy after 1881.Footnote 3 The ways in which kingship, debt, reciprocality, and masculine honour were recast throughout this period frame the discussion in the second section of the article.

The claims of Damodar Dass's female heirs generated further legal dilemmas. These concerned the fraught relationship between scriptural and customary law, and, in particular, the portability of customary law between regions that were unevenly exposed to Anglo-Indian legal regimes. But these various claims to the unpaid debt also reveal the important ways in which a new moral order was being shaped. This new order is evident in the forging of the relationship between the colonial regime and the Maharaja (or, more importantly, his bureaucracy) and in the questioning of the status of four female heirs whose kinship alone was insufficient to support their claims. Thus, the claims of women who were entitled by marriage and kinship to an abstract matrix of rights were fatally wrecked by rendering them non-abstract, embodied subjects, marked now by their individual frailties. If this was the fate of women enmeshed in domestic relations, what of professional women in the non-domestic sphere, such as Ulsoor Narsee? This set of questions is raised in the second part of the article and considered in greater detail in the third part.

Taken together, I argue in the fourth part of this article, these ‘small voices of history’ reveal their potential to disturb the univocality of statist discourse.Footnote 4 For the women whose ‘lives have involuntarily collided with authority’Footnote 5 these voices recover a place that was not intended for them: ‘To make women visible, when history has omitted them, implies a corollary task: to work on the relationship between the sexes, and to make this relationship the subject of historical study.’Footnote 6 Therefore, Devaki Bai, Jumna Bai, Subhadra Bai, and the fainter voice of Mahalakshmi Bai,Footnote 7 who are first drained of life and subordinated to the common coin of kinship, are made to speak a different truth about their times. The figure of Ulsoor Narsee serves as a powerful foil to those mired in domesticity, as she occupies a far more agentive place in this period of transition, disrupting the emerging narrative of women as proxies, yet herself exemplifying the precarities of pre-colonial morality and honour to which the Maharaja had been condemned.

The article, therefore, moves between the public and the private, between the male protagonists and the female subjects-at-law, from questions of honour and reciprocality in the pre-modern period to the tensions generated between private rights and public good in the late nineteenth century. But, above all, since the women's speech is multiply mediated, coming to us via male lawyers, bureaucrats, and judges, and also in languages that the women themselves did not comprehend, we must reach beyond the words of others, glance away from the central concerns of both the bureaucratic state and the patriarchal kin-network, in order to retrieve what we can of the lives of the women.Footnote 8 In order to get there, we must first wend our way through the case that gripped the Mysore state for seven decades.

The dilemmas of a royal debt

Damodar Dass Vallabh Dass, who settled in Srirangapatna, was the most important financier and long-term creditor to the Maharaja of Mysore, Krishnaraja Wodeyar III.Footnote 9 Between January 1845 and December 1848, he lent ‘divers sums of money’ to the king at 12 per cent interest, amounting to Rs 838,922. The Maharaja, who had been reduced to a nominal (private) authority under the East India Company in 1832, showed no signs of repaying this private debt.Footnote 10 After waiting for several years, on 24 January 1855 Damodar Dass sought permission from the then-commissioner of Mysore Mark Cubbon (1834–1860) to file a suit against the Maharaja in the Chief Court at Bangalore for recovery of his debt, which had now grown to Rs 1,461,368.Footnote 11 A year after he presented 50 documents to the court, the Maharaja summoned Dass to Mysore to settle the debt.Footnote 12 Although Dass withdrew the case, no settlement was made before he died in 1857.Footnote 13

For some years the childless Damodar Dass had been accompanied in his dealings by Brijlal Dass, his only nephew and sole heir. Brijlal, whom Damodar Dass had purportedly adopted, made several fruitless trips from Madras, where he had relocated, to claim the large debt. He finally placed his claim (now totalling Rs 2,430,605/13/2) before the two commissioners, Major Elliot and Dr Campbell, who were appointed in 1864 to settle the debts accrued by the Maharaja. The commissioners reduced that sum to Rs 567,338/15/1, almost a sixth of its previous total by deducting interest, depreciating the sums related to goods sold to the king, and disallowing several promissory notes issued by Damodar Dass to the Maharaja.Footnote 14 In 1865, despite Brijlal Dass's repeated appeals against this decision during 1864, the new chief commissioner Lewin Bowring (1862–1870) urged Brijlal to accept the money and relinquish all further claims by 1868;Footnote 15 instead, Brijlal Dass launched another appeal in 1870.Footnote 16

After Brijlal Dass died without leaving a will in November 1871, the female heirs emerged onto the public stage. Brijlal was succeeded by his (second and surviving) wife Devaki Bai. The routine mechanisms of inheritance in a Vania family firm would not have concerned the state at all had she not died in 1875. Leaving nothing to chance, Devaki Bai had appointed Brijlal's daughter Jumna Bai and his ‘stepmother’ Subhadra Bai as ‘joint executrixes’ of the properties in her will. From 1881, Jumna Bai sent many individual petitions to the government, agreeing to accept the sum of Rs 567,338/15/1 which had been offered to Brijlal Dass in full and final settlement of the debt owed to the Damodar Dass family.Footnote 17 Her pleas, made via legal representatives, Messrs Fuller in London and M. Venkata Rao in Madras, were ignored by the government. In 1880, in anticipation of Mysore's return to princely rule under the young Chamarajendra Wodeyar X (1881–1894), she once more requested payment of the debt.Footnote 18

In 1886, another attempt was made to file a joint appeal with Subhadra Bai, this time relying upon the benevolence of the new Maharaja, which generated governmental interest of a higher order.Footnote 19 When Jumna Bai died in 1888, the appeal was repeated in Subhadra Bai's name and that of Jumna Bai's husband Gokul Dass Goverdhan Dass.Footnote 20 In 1889, the Mysore government granted Rs 500/- a month and Rs 83-5-4 a month to Subhadra Bai and Gokul Dass respectively.Footnote 21

An ageing Subhadra Bai kept up her petitions to the Mysore government and the Government of India for the payment of the full amount throughout the 1890s, opening up an opportunity for the reluctant Mysore government.Footnote 22 The new tangle of questions revolved around which law of inheritance was binding for the Khadayata Vania (Gujarati) migrants to Madras. Would it be Mitakshara, as followed in Madras, which ‘did not allow women to inherit’Footnote 23 or its Mayukha equivalent that was followed in Gujarat and increasingly interpreted as giving women inheritance rights? Although Bhashyam Iyengar, the Madras lawyer consulted by the Mysore government, did indeed declare that widows, daughters, and wives were permitted to inherit under Vyavahara Mayukha in western India, the status of women as heirs under Mayukha law and its applicability in Madras continued to preoccupy the Mysore government.

Only on Subhadra Bai's death in 1894, and at the insistence of the Government of India, did better wisdom prevail.Footnote 24 The Mysore government finally declared its willingness to pay up.Footnote 25 But to whom would such a debt now be repaid? Dewan Sheshadri Iyer agreed to give up his fears about the misapplication of the funds and a search for heirs was announced, to be adjudicated by a two-judge court: Mr Justice Best, chief judge, Mysore, and C. H. Jopp Esq. from the Indian Civil Service (ICS).Footnote 26 Of the eight claimants, only two were kin of Brijlal Dass, including a new claim of Mahalakshmi Bai, the sister of the childless Subhadra Bai. In 1896, Best and Jopp, after considering the ‘truth’ of each claim, dismissed them all.Footnote 27 Mahalakshmi Bai and her representative Venkata Rao left no stone unturned in pleading with the Mysore government.Footnote 28 Following her death in 1904, Venkata Rao, who as an agent of Jumna Bai and Subhadra Bai after his uncle Kasi Rao's death, had been managing ‘the business of the firm and attempting to recover the debt from the Mysore State’ since 1876, pressed his pleas for a further 12 years to no avail.Footnote 29

In 1898, the Mysore government declared its intention of honouring the list of religious and charitable beneficiaries in the 1853 will and 1857 codicil of Damodar Dass.Footnote 30 By 1902, it had converted the entire amount of the unpaid debt into a public charity. The Damodar Dass Charities Scholarships for Scientific Research and Technical Education was launched, a class of fellowships that continue to the present day. A private debt was thereby turned into a public charity administered solely by the government. In this way, the protracted claims of four women of the Damodar Dass family were finally extinguished.

Recasting debt and honour

Damodar Dass's relationship with the Maharaja of Mysore predated the rebellions that broke out in 1831 in Nagar. These soon spread to other parts of Mysore, Coorg, and Malabar, as the East India Company invoked Articles 3 and 4 of the Mysore Treaty to assume direct control of the region. The Maharaja was reduced to a stipendiary, receiving 100,000 Canteroy Pagodas (equivalent to about Company Rs 350,000) per annum in addition to one-fifth of the revenue of the state.Footnote 31

As Aya Ikegame has shown, the Maharaja's largesse both before and after 1832 was prompted by his attempt to sustain a system of kingship that had changed beyond recognition. For some time, Krishnaraja Wodeyar III obsessively gave away gifts, inam (rent-free) villages, and favours to different kinds of people—from mathadhipatis (chief abbots of mathas or monastic institutions) to dancing girls—as a way of building prestige and shoring up his shaky authority. The swelling of the Muzrai (religious and charitable establishments) account from 1811 was a sign of this prodigality. The king's gift-giving continued despite his altered status and the crippling Rs 35 lakh subsidy owed by Mysore to the Treasury (out of a total subsidy of Rs 72 lakhs from 198 states).Footnote 32 A dominion formed of fixed territory and relatively fixed revenues could hardly sustain such obsessive, non-reciprocal gift-giving.Footnote 33 When the British took direct control of Mysore in 1832, those who were owed money by the palace rose up in arms. The Gossains of Mysore who were ‘sitting in dhurna at his [the Maharaja's] palace to obtain payment of their claims’ were threat enough for the Mysore Resident, A. J. Casamaijor, to order a guard of sepoys to be stationed near the palace.Footnote 34 Fearing a fresh outbreak of discontent, this time by wealthy merchants and financiers, the government had no choice but to intervene in settling Krishnaraja Wodeyar III's debts to an assortment of ‘Huzoor Sowcars’ (a firm of three who in turn paid the innumerable Gossains supplying goods to the palace) and other bankers.Footnote 35

Krishnaraja Wodeyar III first demanded that the ‘sahookars (wealthy bankers) present all their daftars (documents)’, including those affecting other parties, for scrutiny by a panchayat he had constituted, as agreed by the then Resident of Mysore, Colonel Stokes. The debts claimed before the transfer of power to the Company had been Rs 3,900,000 and a further Rs 400,000 had been borrowed after the transfer in 1832.Footnote 36 But even in 1844, 12 years after the panchayat had been constituted, an amount of Rs 30,800,027-2-3/4 still remained unpaid. Commissioner Mark Cubbon, in his desire to bring the whole process under critical scrutiny and pay off the debts, suggested the appointment of John Peter Grant as a special commissioner for the Adjustment of the Debts of His Highness the Rajah of Mysore.Footnote 37 The Commission, though originally charged to complete its work in two years, continued until 1848. At the end of his adjudications, Grant put the debt that remained chargeable to the Maharaja at Rs 1,843,078, though Damodar Dass's claim was separately ‘placed by him in train of amicable compromise’.Footnote 38

Damodar Dass was clearly among the most important creditors of a king whose needs, tastes, and expenses far exceeded his greatly reduced means. Why had the Maharaja continued to take money and goods from local and distant sahukars and Gossains even after 1832, when his powers had been diminished?Footnote 39 David Graeber's magisterial anthropology of debt is of use here, particularly in the distinction made between a system that operates according to rules of hierarchy that are known and respected, as opposed to a system of market equivalence.Footnote 40 Damodar Dass's massive loan placed the Maharaja of Mysore, someone who had freely bestowed lands, gifts, and money until 1832, in a new relationship of equivalence with a powerful sahukar. The king nevertheless tried to incorporate Damodar Dass into a hierarchical relationship by granting him an inam (rent-free) village.Footnote 41

That Damodar Dass opted to take the Maharaja to court but withdrew the case just a year later is a sign that the banker had not quite relinquished the affective ties that bound him to his royal debtor.Footnote 42 But Damodar Dass was already in the grip of processes that subordinated the flexibilities of kin- and clan-based mercantile power to a territorialized, administrative state.Footnote 43 He declared his independence from older systems of alliance in his will of 1853, when he stated that he was ‘separate in interest from all his gnatis (kin) for nearly 75 years past (sic), and that the properties mentioned therein were all acquired by him personally and were his own’.Footnote 44 This impressive list of self-earned moveable and immoveable properties placed the king's debt among the most important of his bequests: ‘About Rs Nine lacs of rupees due both for money and articles from Maharaja Raja Saheb Krishnaraja Wodeyar of Mysore’.Footnote 45 His nephew, son of his brother Giridhar Dass, was named as his heir in both the will of 1853 and codicil of 1857. On this ‘son’ would devolve the rights to his property as well as the duties of paying out to the charities that were listed in his will. Brijlal's only child Jumna Bai was acknowledged as his ‘granddaughter’.Footnote 46

Unlike his uncle/‘father’, Brijlal Dass, who was domiciled in Madras after Damodar Dass's death, quickly mastered the new mechanisms of power. He was not bound by the rules of hierarchy and took full advantage of the protracted debates among government officials about whether the king's debts were private or public ones.Footnote 47 He went further than Damodar Dass in claiming the entire sum of over Rs 24 lakhs, comprising the original principal plus the accumulated interest until 1864. In 1867–1868, when the Maharaja died, that would have accounted for over one-fourth of the state's revenues.Footnote 48 Brijlal Dass also confronted the British commission of Elliot and Campbell over its arbitrary and capricious methods which were no different from that of the king they sought to reform.Footnote 49 Unlike his uncle/‘father’, who withdrew the case he had been allowed to file, Brijlal Dass was actively ‘prevented and hindered from prosecuting [the king] in due course of law’, a freedom he would undoubtedly have enjoyed against a private individual.Footnote 50 Here we must note this interesting paradox of a notional kingship that was exempted from prosecution despite enjoying no de facto kingly power.Footnote 51 By the 1860s, when the continuation of his line in Mysore became more certain, Krishnaraja Wodeyar III's ‘kingly’ authority was partially restored and he was once more placed above the reach of the law.Footnote 52

By stressing the capriciousness of the colonial authorities, Brijlal Dass exposed the hollowness of the ideological claim of colonial rule as a ‘rule of law’.Footnote 53 Brijlal thought even less of a king whose vulnerabilities were clearly on display; he did not share his uncle's enchantment with kingship. In two communications that he placed before the Mysore authorities, Krishnaraja Wodeyar III was shown to have made some furtive attempts to settle what was turning into a crippling embarrassment. The Maharaja had long recognized Brijlal Dass as the principal negotiator in this debt, even while Damodar Dass was still alive. Therefore, in February 1852, the Maharaja sought the intervention of his buckshee Dasappaji to convince the stubborn creditor:

In accordance with the communication received from your brother there, people were sent to Chitty's son [Damodar Dass’ son Brijlal] here to speak to him. He was however inflexible. If you meet him, bring him to reason and if he would take 9 lacs, it will be well and good. If not, let him do what he can, and we shall see about it … It must not appear as it is said at our instance.

Sri Kistna.Footnote 54

A few months later, when Brijlal's determination had become even more evident, a plaintive Krishnaraja Wodeyar III accused the buckshee of prevarication, even betrayal of the throne:

… you have not yet compromised the affairs with him, and brought him to us. This shews your indifference to the affairs of our Huzur. If this much is not done, what else can be done, now at least, you should see him and satisfy him in a suitable manner in accordance with the last note. Come before us to represent the result.

Sri Kistna

After this, in an anxious postscript, he added: ‘Anyhow you make him agree to 9 lacs (900,000).’Footnote 55

The king's desperation was laid bare in these brief notes. They also revealed that relations between creditor and debtor had been thoroughly recast. The usurer, conventionally the one of dubious morals,Footnote 56 had now become the victim of the king's broken promises, and he was reduced in these communications to an anxious hand-wringer whose hollowed-out power could only be saved by a public display of nonchalance. In 1858, Krishnaraja Wodeyar III once more attempted to settle the debt via the commissioner, Mark Cubbon, but Brijlal remained intransigent.Footnote 57

The firm of Damodar Dass/Brijlal Dass played as important a role in Mysore as the great firms of Hyderabad analysed by Karen Leonard, which were ‘serving as state treasurers, minters of money, and revenue-collectors as well as maintaining long distance credit and trade networks’.Footnote 58 Damodar Dass himself was at the head of a chain of debts contracted on behalf of Krishnaraja Wodeyar III in expectation of their settlement from the Maharaja's one-fifth share of the state's revenues.Footnote 59 The East India Company, meanwhile, had effected nothing less than a sea change in the financial systems of the Raj. That the new systems permitted not only the raising of loans, but also selling them in the market, was something that the Durbar clearly had not grasped, as J. D. Stokes, the Resident of Mysore pointed out:

They know that the Company borrow money, and they know they pay interest on it … they also know that the principal of money lent to the company is not recoverable on demand, but they do not know how it is recoverable for it does not occur to them that loan certificates are saleable in the market like any other commodity.Footnote 60

Yet the loan, though meticulously recorded by Damodar Dass in Gujarati in his bahi khata, like all his other liabilities and dues, was not yet stripped of its other meanings that bound king and subject. Why else did even J. P. Grant, the commissioner appointed to settle the Maharaja's debts, leave Damodar Dass's loan out of his purview?

Many years later, Dewan Sheshadri Iyer (1883–1901) would rightly point out that the protracted process of dealing with the unsettled debt of the Maharaja ended in 1864, when the private debt was made into a public one—that is, one that the state was bound to pay from public revenues.Footnote 61 Modern principles of debt management were being tried and tested in England with some success. Public debt had been turned into something respectable by the colonial government, especially at a time when ‘interest charges of the Government of India and England accounted for more than one-tenth of the total expenditure’, as Sabyasachi Bhattacharya has shown.Footnote 62 A new notion of honour, one that cohered more closely to British ideas of manly obligation rather than kingly gifting or more professional debt management, was being created to replace what a system that had clearly outlived its utility.Footnote 63 If Brijlal's request was posthumously considered at all, it was not because either he or his heirs exercised any right: the repayment was being considered as a ‘favour’ and as a moral obligation.Footnote 64 Successive colonial officials began elaborating on why the Maharaja was bound to repay his debt.

Sheshadri Iyer noted the enviable craftiness by which colonial officials began sermonizing on honour and obligation just at a time when that obligation was no longer their own.Footnote 65 The notion was first articulated by the Mysore Resident Cunningham in March 1881,Footnote 66 upheld by the chief commissioner of Mysore and Coorg James Gordon (1878–1881) in 1882, and endorsed by the next Resident in Mysore James Lyall (1883–1887) in 1886. Voicing his opinion on Jumna Bai's petition of 1881, Cunningham said: ‘although the person to whom the award was originally made refused to take it within the time fixed, the debt is one that is a matter of honour His Highness the Maharaja's Government could not refuse to recognize …’ and even suggested the payment of interest.Footnote 67 Successive petitions reached the secretaries of state Lord Cross (1892), Lord Kimberly (1893), and Sir Henry Fowler (1895), who ‘over-ruled [the Mysore Durbar's objections] and ordered payment in strict terms’.Footnote 68 By emphasizing that it was a moral obligation and not a legal right that was being considered, the Government of India elevated honour as the grounds on which the debt had to be paid.Footnote 69 It is no wonder that the Mysore state chose to emphasize the opposite and sought refuge in the question of the right of females to inherit under Mitakshara.Footnote 70

Barrenness and inheritance

In 1892, Sheshadri Iyer set the ball rolling in a different direction. With reference to the plea of the new heir Subhadra Bai for the payment of the debt, he said:

Here may arise the further question as to what Hindu Law is applicable to the parties, whether the law as prevalent in Madras where the parties have resided for several generations, and where the Mitakshara is the accepted authority or the law as prevalent in Guzerat from where the parties originally came and where the accepted authority is the Vyavahara Mayukha.Footnote 71

With this observation, Sheshadri Iyer, a trained lawyer and former judge himself, successfully turned attention away from competing notions of masculine honour and the knotty question of whether the Mysore state should repay what the colonial government had so deftly avoided, to the surer ground of female inheritance under Hindu law.

All the women who appeared in the thick web of transactions which became the basis of the claims and counter-claims were classified as members of ‘the [Damodar Dass] family (consisting of a childless widow and a childless lady, the daughter who is reported to be insane)’.Footnote 72 Their names appear in the colonial archive only because they are marked by a common failure: as the conduits of property, they repeatedly failed to produce a legitimate male heir. Thereby, they unwittingly become the place-holders for an inheritance that was continually deferred and could not be their own. A new possibility of legal ‘personhood’ was opened up by these women's access to property, in contrast to their relatively non-agential existence as property that was trafficked between families. Yet Iyer's characterization of the women—‘childless widow’, ‘childless lady’, and ‘insane daughter’—reveals that they were always turned into embodied, non-abstract subjects that undermined the promise of that moment.

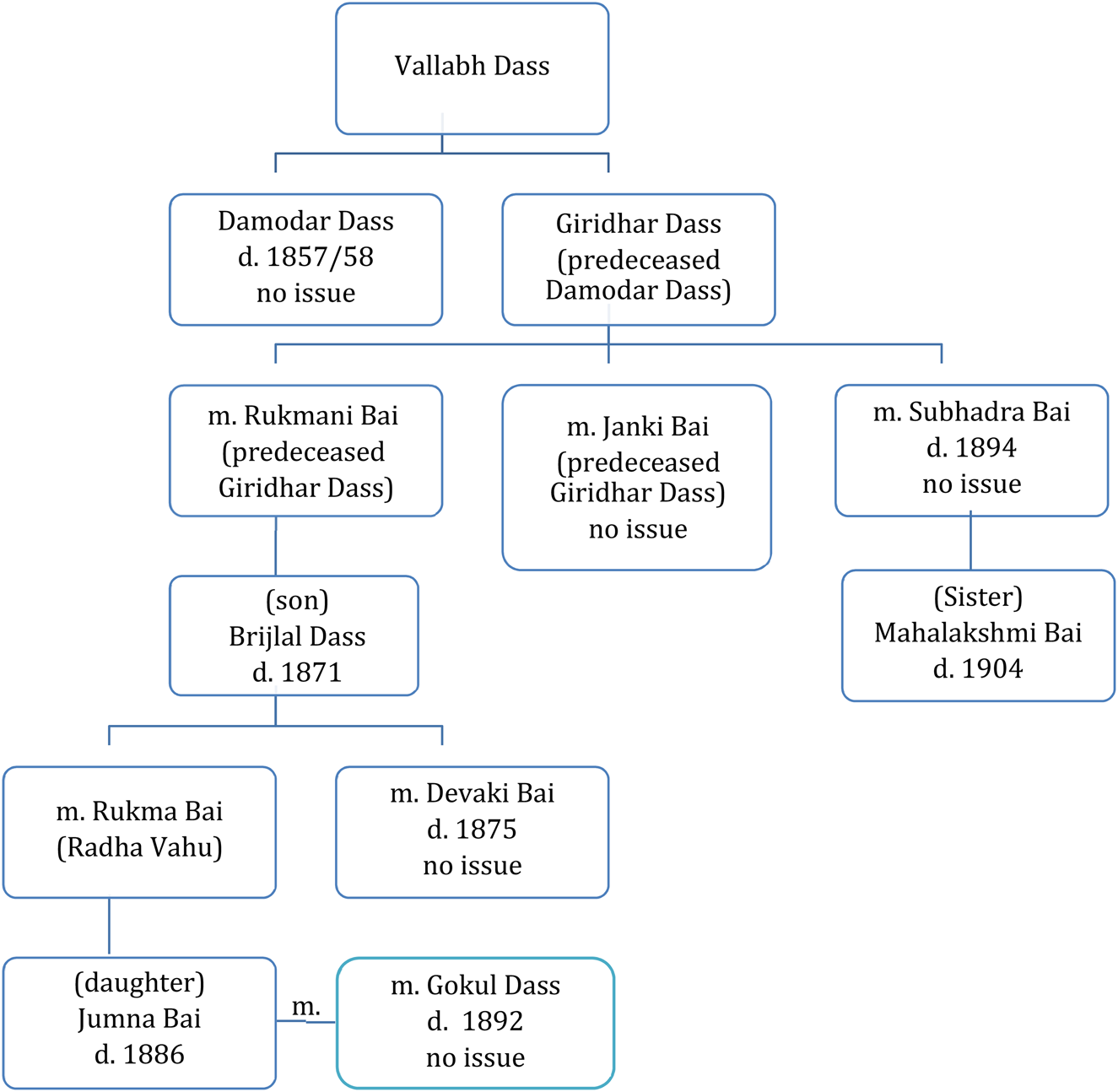

The genealogical chart that accompanied the arguments laid bare the consistency with which successive generations had failed to produce a legal male heir (see Figure 1). Damodar Dass, whose wife predeceased him, had ‘no issue’. Giridhar Das, Damodar's elder brother, had three wives—Rukmini Bai, Janaki Bai, and Subhadra Bai—but only Rukmini Bai had a son, Brijlal.

Figure 1. Damodar Dass's family tree. Source: The author.

Rukmabai, Brijlal Dass's first wife, produced only a daughter, Jumna Bai; Devaki Bai, his second wife, was childless. Devaki Bai intended to adopt a son so she only appointed Jumna Bai and Subhadra Bai as managers of the estate with restricted powers until the son turned 20. Her will stated:

Moreover, I have no issue: on account of the continuation of the lineage by the order of my husband we have looked for and found a boy and Sayadas and Sagotras for adoption. One boy out of them shall be adopted in the name of my husband, and that boy shall be married and after he becomes of the age of 20 years, my estate which may remain shall be delivered.Footnote 73

We know, after Karen Leonard,

… that marriage and inheritance practices among these patrilineal mercantile families [Gujaratis, Marwaris] were actually quite flexible, notably involving affines—relatives by marriage—as major players. Wives and their kin did play roles in mercantile family histories. Flexible family strategies meant not only continuity for the family firms but also a potentially broad spatial range of financial network.Footnote 74

Why, despite the thoroughness of the search, did nothing come of the efforts to adopt after her death? Both executrixes, now turned heirs, and Jumna Bai's husband, Gokul Dass Goverdhan Dass, assumed an even greater role in the estate's management. Yet, in her petitions to the government, Jumna Bai took care to represent herself as the ‘sole surviving heir and lineal descendent of Brijlal Dass’, asserting a right by birth and not Devaki Bai's will alone.Footnote 75 The process of laying legitimate claim to the Brijlal debt as ‘heiress at law’ required Jumna Bai to erase Devaki Bai's brief tenure. We can only speculate on the longer term calculations of this family firm, which saw Gokul Dass Goverdhan Dass firmly in the saddle for several decades. But we would not be wrong in recognizing the threat posed to his de jure enjoyment of the huge estate of Rs 20 lakhs by a possible adopted entrant.

Jumna Bai also produced no male heir.Footnote 76 Though the state's genealogical table marked her too as having ‘no issue’, in support of the rival claimants Murledas and Kessandas, 18 witnesses said otherwise before the Special Court of Best and Jopp in 1896: ‘Shortly after the marriage of Devaki and after the birth of Jumna Bai's second child Jumna began to show signs of insanity.’ Whether or not the two children survived childbirth and childhood, this slight evidence speaks differently about Jumna Bai's fertility than the official kinship table would have us believe.Footnote 77 Subhadra Bai, the third in this series of female heirs, was herself a childless widow and entertained no hope of transmitting this property even by adoption.

The undisturbed enjoyment of Brijlal Dass's estate by Devaki Bai between 1871 and 1875, and by Jumna Bai between 1875 and 1888, albeit by their proxies, was therefore finally disrupted by the series of doubts regarding the legitimacy of their inheritance. Was the law applicable to the Khadayata Vania women that of their place of extraction, namely Gujarat, or their place of residence, the Madras Presidency, where the family had resided for at least the last 90 years?

A forest of related questions sprang up. Did Devaki Bai, as a widow, enjoy absolute possession of Brijlal's estate and was she therefore entitled to bequeath her estate to her ‘daughter’ Jumna Bai and her stepmother-in-law? Was Brijlal Dass indeed adopted by Damodar Dass? Did that not make Subhadra Bai ineligible to inherit as his wife's stepmother-in-law? If Jumna Bai was indeed heiress-at-law, why did she choose to remain an executrix and not first assert her claim as daughter independent of Devaki Bai's will? These questions would unsettle the certainty with which the estate of Brijlal Dass had been managed for at least 14 years.Footnote 78

Sheshadri Iyer succeeded in convincing the Government of India to query the rights of the women concerned and the Mysore state was permitted to establish the status of each of the legatees.Footnote 79 However, the opinion sought from a leading Madras lawyer, Bhashyam Iyengar, drove the discussion in an unanticipated direction. Iyengar made it clear that the Damodar Dass family was free to adapt as slowly as possible to the laws of the place of residence, in this case South India. Until the contrary was proved, he said, the Damodar Dass family did indeed fall under the Mayukha law which permitted females—widows, daughters, and even stepmothers-in-law (as widows of gotraja sapindas)—to inherit. Drawing attention to the peculiarities of western India, and the generous judge-made law that upheld this, Iyengar concluded that the Jumna Bai inheritance could be considered as stridhan and therefore inheritable by members of the father's family, in this case her step-grandmother, Subhadra Bai. His logic is worth quoting in full:

There are really only two schools of Hindu Law i.e. that following the Mitakshara and that following the Dayabhaga of Jimutavahana. It is the Mitakshara system which obtains both in Western and Southern India, but partly on account of local customs and usages and partly on account of a difference between West and South India … there are minor differences … The growth of customary law in western India has favoured the right of females to inherit and the doctrine prevailing in other provinces that women are incapable of inheriting without a special text has not been received in Western India.

In Iyengar's words, we may detect the epistemic violence of the codification of Hindu law, which privileged scripture over forms of custom. This was compounded by Iyengar's concurrence with the strikingly Brahmanical norms that he had already described in disparaging terms:

The laxity with which in Western India females are admitted as heirs without admitting the doctrine which asserts the general incapacity for women for inheritance and its corollary that women can only inherit under special smritis is no doubt the result of usage and custom which has prevailed in Western India.

Iyengar concluded, however reluctantly,

Both on the general ground and the special ground that the right of the female gotraja sapindas in the Western school is really based upon local usage and custom, I am of opinion that the Bombay course of decisions will be applicable to the case.Footnote 80

The matter was not laid to rest. Sheshadri Iyer was convinced of the error of the western Indian judges in reading customary law so generously and even doubted the antiquity of such custom:

We have no exact information as to the mode and time of the origin of this Bombay custom which is so inconsistent with the general principles of Hindu Law as accepted throughout India and we are therefore unable to come to a final opinion as to the applicability of that custom to the parties in the present case who left Bombay about a century ago …Footnote 81

Sheshadri Iyer's insistence on a uniform Hindu law that was ‘accepted throughout India’ gives us pause. As a senior legal practitioner, he was surely aware of the debates raging in the public sphere and in the courts concerning the ‘legality’ of the matrilineal family forms and inheritance traditions of the Nairs in Malabar and Bunts in South Canara, or matrilaterality among the Basavis of Bombay Presidency.Footnote 82 His wilful ignorance contrasted with Bhashyam Iyengar's nuanced reading of the law. This begs the question: did his approach only serve the higher purpose of saving the Mysore state from a needless drain on its revenues?

Iyer did not stop there. He brought all the moral authority at his command to query the inheritance. Questions of law apart, the age, vulnerability, and social position of the women were sufficient to deny them any agency, since they could only be proxies for male ambitions. Sheshadri Iyer, preferred, therefore, to undermine what was right in law (that is, the portability of custom) and insert in its place a moral question of which he would be the supreme arbiter. He proposed a search for a settlement that ‘would possess the advantage of preventing the possibility of any scandals arising in connection with the appropriation of so large a sum of money by an aged Hindu widow without any natural advisers and surrounded only by interested vakils and law agents’. Iyer concluded that ‘the more we examine the case, the further we are from finding any proper successor to the estate’.Footnote 83

Iyer displayed breathtaking confidence as a bureaucrat. His determination to turn the women of the Damodar Dass family into objects of charity, rather than subjects of rights, had already yielded fruit when he persuaded Chamarajendra Wodeyar X to grant, as an act of benevolence, stipends to Subhadra Bai and Gokul Dass, the husband of the deceased Jumna Bai. As I later show in the case of Ulsoor Narsee, a devadasi dismissed from Mysore in the same period (a case also presided over by Sheshadri Iyer), the rule that women could not inherit property had to be established, despite laws to the contrary. A robust body of case law,Footnote 84 which showed greater flexibility of interpretation and also upheld custom, is to be found in judgments compiled in the digest of West and Buhler.Footnote 85 Though he was forced to admit that ‘[the] Daughter is [the] absolute owner in Bombay as per recent judgments’, he concluded with the caveat ‘but it is unlikely Jumnabhayi knew this recent case law’.Footnote 86

Sheshadri Iyer's firm anchoring of the women within their kin network was disturbed by Gokul Dass's interest in his wife's substantial estate. Jumna Bai claimed that she had ‘obtained probate from the HC Madras on the 22 September 1875 [for Devaki Bai's will], and since carrying on all transactions in accordance with the said Will…’.Footnote 87 Further she claimed:

…we have both [Subhathra Boyee and Jumna Boyee) been conducting all matters according to the aforesaid will [of Vrijlal] through my husband Gokul Doss Goverdana Doss. Therefore as I have been very ill in body for the last 5–6 days and cannot survive, I hereby convey all my interest and rights to my aforesaid grandmother Subhadra Boyee Amma. So the aforesaid Subhadra Boyee Amma shall after my death be the absolute owner and conduct all business matters as usual through my husband Gokul Dass Goverdhan Dass.Footnote 88

But had Jumna Bai written a will at all? It was certainly not in evidence when she died and was ‘found’ only in 1896 in time for the meetings of the Special Court. A great deal rested on the authenticity of the newly discovered will, since Subhadra Bai was not entitled to any share in the Brijlal Dass property except that which had been willed to her by Jumna Bai. On 10 April 1893, the ‘mother of Brijlal Das’ and ‘widow of Giridhar Das’ recounted her own inheritance:

Accordingly [after Devaki's will was probated] I and the said Jamuna Bai not only took possession of and enjoyed the said properties with all rights and carried on dealings but were also collecting and recovering the outstanding debts making demands in respect of them at the necessary places and enjoying (the property) with full rights and without any sort of objections on any body's part. While so, the aforesaid Jamuna Bai died having on … [this was left blank] day of August 1888 given up to me by means of a Will all the right and interest of every sort which she had to and in the aforesaid properties.Footnote 89

M. Venkata Rao admitted that

I wrote the last will and testament of Jumna Boyee the daughter of the late Birjlal Doss in the Telugu language and character at her request … I read out the same to the said Jumna Boyee who was well acquinted [sic] with Telugu language in the presence of Gunsham Doss Damodara Doss and Girder Doss Nathusa and Briji Ruthna Doss Bal Doss … thereupon Jumna Boyee put her mark to the said will and Gocul Doss her husband now deceased wrote in the will … that the mark so made therein was that of Jumna boyee.Footnote 90

As we have already seen, the Special Court did not accept Jumna Bai's will, but as the historian need not play the judge, we shall return once more to Jumna Bai's claims.

Having raised these new obstacles to the resolution of a long-pending case, it must have been with relief that Sheshadri Iyer learned of the death of Subhadra Bai at the age of 90.Footnote 91 However, Brijlal Dass's claim refused to disappear and took on an afterlife with the discovery of a will of Subhadra Bai which bestowed the estate on her sister Mahalakshmi Bai. We have come a long way indeed from Damodar Dass or even Brijlal Dass if a stepmother-in-law thought fit to appoint her own sister, now made ‘the dayadi of Brijlal Dass under Mayukha Law’, as her heir.Footnote 92 What might have worked in a Bombay court was not allowed any traction in a Mysore debate. Sheshadri Iyer clung to the dismissal of Jumna Bai's will in 1896, claiming that the state could do as it wished with this substantial fund, freed at last from ‘the surviving wrecks of this long standing claim’, to use the graphic language of M. Venkata Rao, who had been involved for so long.Footnote 93

The ways in which the possibility of the legal personhood of women, affirmed by Mayukha customary law, was undermined by a focus on the ‘frailties’ of women, allow us access to the domestic worlds of women and open up the space in which to explore of a different, affective personhood. It is to these women that we now turn.

Domestic women and their discontent

Longing

In the midst of the prolonged exchange between Mysore bureaucrats, Madras lawyers, and Government of India officials, we only hear from the women themselves through their wills and petitions. Operating within the space of these formulaic legal documents, the women were deployed to ensure that Damodar Dass's estate remained under the control of the family.Footnote 94

A search for signs that these women were not mere proxies in the hands of male family members and lawyers swiftly runs aground. One may assume that the sheer length of the case made the women legally literate in the finer points of Mitakshara or Mayukha law, but were they functionally literate? If so, in which language? From these documents, written in Telugu, translated from Gujarati, and always signed with a swastika, can we deduce that they were illiterate? Damodar Dass kept his accounts in Gujarati, transacted with the Mysore court in Kannada, and was regularly called on to testify about the rates of interest used by Krishnaraja Wodeyar III's suppliers of goods and credit. His facility with multiple languages could have been the norm for a man of his status and wealth. Literacy may have been less useful for the women of the Brijlal clan, immersed as they were in a domestic life whose solace was primarily prayer and pilgrimage.

The organized self-interest that haunt the petitions of Subhadra Bai, Jumna Bai, and Mahalakshmi Bai is occasionally broken by faint longings and desires. Devaki Bai's will, first written in Gujarati by her brother, Kishen Dass, on 30 August 1875, was signed by a swastika ‘as a hand mark of Devaki Bayi’; it was translated into Telugu for the court, and retranslated into English for the Mysore government. In that will, she appointed her mookthiars, her stepmother-in-law Subhadra Bai, and step-daughter Jumna Bai

to collect receive and recover the whole of my moveable and immoveable property and the whole of the dealings and to collect and recover the whole of what may be due from the Rajah of Mysore, the Rajah of Guddaval, and the Rajah of Vanaparthi, as well as from people and to make payments and to receive payments in the dealings I have now been carrying on and to conduct matters according to what is written by my father-in-law Damodar Dass Jee in his Will …Footnote 95

Devaki Bai, at the helm of a very substantial and complex estate, fully intended to adopt a son, but did not live to realize that longing. Could she have had much in common with the rural Patidar woman whose heart-rending emotion she may have shared?

I have my courtyard nicely dunged but barren,

Bless me with one who shall trample the yard,

and leave small foot prints upon it.Footnote 96

Her stepdaughter—‘Jumna bayi, may she live long with her husband!’—whom Devaki Bai exhorted throughout her will, could not fill that hollow; as a likely contemporary in age, Jumna Bai could not replace the young child that Devaki Bai yearned for. That space was filled by Jamni, a girl she cared for: ‘Besides this, I have been bringing up Jamni, the daughter of a Khedaval Brahmin, on her marriage at the time of giving her away in marriage, jewels of the value of Rs 500 shall be given to her.’Footnote 97

It is in these references that the wills, although prepared by legal adepts, allow small glimpses of ‘female worlds of love and ritual’, revealing spaces of devotion shared by the women of the Brijlal family and their commitment to fulfilling the spiritual wishes of Damodar Dass by propitiating deities, funding charities, and giving alms.Footnote 98 There may have been no insincerity or gap between the legal and the domestic worlds in their claims that ‘all our estates have become encumbered with debts, and [we] … ourselves are in very narrowed circumstances without even the means of adequately offering puja to our household gods’.Footnote 99 However, devotion could verge on the obsessive and even be seen as a sign of madness if it impinged upon an appropriate sense of wifely duty, as in the case of Jumna Bai.

Insanity

Jumna Bai's alleged mental infirmities were brought up for scrutiny before the two-member Special Court by Murli Dass and Kishan Dass, one of the two sets of family claimants on the money owed to Brijlal Das. Even if (as claimed by the other party of Mahalakshmi Bai and Vencata Row) Jumna Bai was within her rights as the daughter to dispose of Brijlal's property as she pleased and had written a will, could she have been fully aware of the importance of her act? Eighteen witnesses for the claimants ‘Murledas and Kessandas’ claimed ‘that shortly after the marriage of Devaki and after the birth of Jumna Bai's second child, Jumna began to show signs of insanity’. The litany of disturbed acts ranged from her mundane refusal to fulfil the norms of wifehood—she was short tempered, she talked loudly to her husband—to far more pathological behaviour:

She at first began to get angry with her husband and father and to disobey them and assault them. She used to say that people had put poison in her milk and rice. She used to declare that she heard someone talking behind the house. On one occasion she ordered a bier to be prepared and placed on it a doll of straw. After she went with her husband to Madras she got worse, she refused to come and see the body of Brijlal Dass after his death, saying that her father had not died. … [S]he occasionally sent for a book and after reading it for a time, she tore some of the leaves and threw it away. … [S]he had to be kept upstairs in a room and her food was cooked separately for her. She used to remain seated in the presence of her husband…. She threw away her food saying it was poisoned and insisted on going back to Seringapatam. … [S]he was taken to a garden at Tiravathur and there Gokaldas only visited her occasionally.Footnote 100

The witnesses for the other petitioners, Mahalakshmi Bai and Venkata Rao, were interested, in contrast, in establishing Jumna Bai's sanity at least at the point of her executing a will, if not until her death. Had she not signed deeds of sale for properties in Madras? ‘She would not have been permitted to execute deeds or pass powers of attorney as Devaki's executrix without protest from Brijrathandas, Murledas, or other interested parties in this estate.’Footnote 101 The two judges made sense of these contradictory claims by accepting Jumna's sanity, but rejecting the will itself as a forgery:

The truth of the matter we believe to be as follows: it is probably that before the date of exhibit A, Gokaldas had begun to despair of having any more children by Jumna Bai, that Jumna Bai had begun to disobey Gokaldas, to abuse him and quarrel with him and to insist on living and dining apart from him. By degrees, Jumna Bai became more and more eccentric and it is probable that the witnesses for the claimants in case no 6 have exaggerated and ante-dated these eccentricities. …We do not however, think that at the time of Devaki's death, that is in September 1875, Jumna Bai was insane, at any rate, according to the test of insanity given by Mr Bhashyam Iyengar, that is, that she was incapable of managing her own affairs.Footnote 102

The two-judge Special Court seemed less interested in her state of mind and focused instead on Venkata Rao's admission that he wrote the will. This was seen as proof enough of its illegitimacy.Footnote 103

Genuine or not, the actions that are indexed as proof of Jumna Bai's illness should interest us here, though they lead us to more questions. If Jumna Bai was indeed literate, why did she choose to affix a mark on her will: ‘Thereupon Jumna boyee put her mark to the said will and Gocul Doss her husband now deceased wrote in the will with respect to such mark that the mark so made therein was that of Jumna boyee’?Footnote 104 Gansham Doss, a clerk in the firm who was also a member of the same family, testified quite differently:

I lived in the same house with Jumna boyee, I am still in the same house. I have seen her execute many documents. I can give examples. Jumna Boyee could read and write Telugu, Guzarati and Nagari. It is the practice of the women of our caste not to sign but only to put a mark. Jumna Boyee never used to sign her name but always put her mark Satya Mark. They don't write documents or letters.Footnote 105

Yet, Krishna Doss Vital Doss, the head of the 150-strong family group of Khadayati families from Gujarat living in Madras, testified to her undoubted abilities, even two decades after her death. In court on 18 August 1906, he said:

I am head of Kadayita. … Jumna Boyee knew Nagari, but not Gujarati or Telugu. She knew to read but not write Nagari. Jumna Boyee herself put the mark, I can't say if she put it with a reed or pen or with Shayi or ink.Footnote 106

Therefore, Jumna Bai could read, if only Nagari, but not write. She was, in short, a passive literate who perhaps spent her days reading religious books.Footnote 107

Nevertheless, 20 letters concerning the banking firm's dealings and interests were also produced as evidence of the continued transactions on the Brijlal estate, even after Jumna Bai had died. The letters record a vast network of properties and interests in Bombay, Madras, Mysore, Gadwal, and Benares, and choultries at Srirangam and Madura with which Gocul Dass and his male partners were involved. Pleas for cloths for the gods, money for pilgrimage, and information about pujas conducted found their way into the predominantly business letters.Footnote 108 Confirming the almost stereotypical image of the woman of means in the nineteenth century, it is devoutness that becomes apparent to us across the centuries.Footnote 109 Jumna Bai is thus driven even further to the very edges of the affairs of men. Despite their involvement in the public worlds of money and commerce, it is the women's secluded domestic worlds that appear to have been most meaningful and afforded them solace in grief and madness.

As Rachel Sturman has pointed out, ‘the basic corporeality of persons—their fundamentally non-abstract character’ always checkmates the logic of universal humanity.Footnote 110 So strongly did their age and gender work against their capacity to comprehend business matters, let alone execute a will, that even those women whose mental abilities were not doubted by any of the contending parties, such as Subhadra Bai, became non-abstract, embodied subjects in this discourse. Thus, no less than a surgeon-major testified in 1894 that ‘[Subathra Bhaee] can converse with me freely and is intelligent and possesses sufficient mental power to understand all that she hears other people say. I am of opinion that she has quite sufficient intelligence to be able to conduct her own business.’Footnote 111 Yet she too was denied her rights in law.

Belonging

For our Khadayata women of Madras, was the gap between place of extraction and place of residence an issue that only mattered in law? The legal matter was settled, as we have seen, in arguments that decisively proved the portability of customary law from Bombay to Madras Presidency and therefore affirmed the legality of the widow, daughter, and stepmother-in-law as inheritors. But there were many non-legal ways in which a sense of belonging could be adduced, annihilated neither by time nor distance. They once more allow us a glimpse of women as the primary bearers of culture. The speed with which the men of the Khadayata community adapted to economic transformations and the new circuits of power that were in operation was not matched in the life and language of the household. Some cultural traits were very slow to change—or even became more entrenched in the immigrant community. Fifty-one men, endorsed by another 24, were at pains to establish the purity of the Khadayata links with Gujarat:

We are following the religion … which prevails there under the supremacy of our Gurus … the descendants of Srivallabhacharya, unaffected in the least by any differences prevailing in this part of the country. Besides with respect to law and usage, we are following those of Gujarat, keeping aloof from and not following those of this part of the country or of other castes or sub castes or others.Footnote 112

The Special Court weighed in with its own anthropological detail, affirming the close affinity of the Madras vanias with their place of origin:

On the evidence we think that is it quite clear that Khadayeth Vysyas in Madras generally speaking still maintain the same social and religious usages as in Gujerat. They speak Gujerathi, they obey Vallabhcharya, they dress in the main as Vysyas in Gujerat do, they use the Vikramaditya era, they begin their year with the Dipavalli, they use the Sathya mark in their account books and their religious ceremonies both in respect of marriages and funerals are the same as in Gujerat. It is, we think, pretty clear from the evidence that the Ekadhanya is worn by the married Gujerathi Vysya women in Madras, and that it and the ivory bangles are with them symbols of the married state …

At the most, they continued, there may have been some minor adaptations to the locale: ‘… both men and women wear finer cloth than in Gujerat, the women's ornaments are of finer make, the women's bodices in Madras have backs whereas they have no backs in Gujerat’.Footnote 113 Sure signs that the Khadayata Vanias of Madras had adopted at least some of the features of the South Indian upper castes were explained away. For instance, the sacred thread, which was rarely worn in Gujerat, had been adopted in Madras.

With regard to the sacred thread … there is contradictory evidence, but I think … that these insignia are adopted by men and women in order to make it clear to people with whom they consort that in the one case they belong to the Vysya class and that in the other they are married women. It comes to this that if it be true that the men have adopted the sacred thread or that the married women have adopted the bottu, they have done this not in substitution for the emblems which are worn in the place of their origin viz. Gujerat but in addition.Footnote 114

What we know of the Khadayata Vanias (and Khadayata Brahmans) comes from R. E. Enthoven. He said they ‘are found all over Gujarat [and] take their name from Khadat, a village near Parantij, about 25 miles north east of Ahmedabad’.Footnote 115 They did not, in their place of origin, sport the ‘sacred thread’. Their family priests were Khadayata Brahmans, and their family deity was Kotyarkeswar of Khadat Mahudi, near Vijapur in Baroda territory. Enthoven further noted that ‘among Khadayatas, large sums of money are frequently paid for marriageable girls’.Footnote 116 If bride price, rather than dowry, prevailed among the Khadayata community, what did it say about the place of women in the production and reproduction of the family firm? If, over such a long period of time as a century, the place of women had been transformed,Footnote 117 was it likely that women played a greater role in decision-making than the accounts we have examined would have us believe?

If the men retained active links with western India, at least for business reasons, we can only speculate on the lives of women, for whom the pilgrimage meant journeying away from domesticity. There are enough clues, in the kinds of charities and temples that Damodar Dass and Devaki Bai supported, to suggest that the Khadayata women of Madras were crafting a new sacred geography within the peninsula to include Srirangapatna, Srirangam, and Rameswaram.Footnote 118

Ulsoor Narsee: non-domestic woman as counterfoil

Our account has retrieved only small and suggestive fragments from the purposively constructed documents of Damodar Dass's female heirs. Their presence tells us much more about the vice-like grip of state officials, lawyers, or male family members, each with their own interest in depriving them of an inheritance or claiming it in their name. The presence of these women in law was further undermined by the insistence on their inherent frailties.

But what of the case of a non-domestic woman, one Ulsoor Narsee, who was enfolded in a pre-rights economy of gifting in acknowledgement of her services? A fragment from the archive yields crucial insights into the regimes of honour and gift-giving that, by the 1840s, the Maharaja had been forced to relinquish.Footnote 119 In her petition before the Grant Commission in 1846, Ulsoor Narsee questioned the Mysore government over summarily dismissing her claim from the Mysore Maharaja. She did not belong to a family of wealthy creditors or landowners, nor was she related to any other claimants by accident of marriage, like Hira Bai and most other women who appeared before Grant. It is because she did not enjoy the privilege of a mediator as skilled as M. Venkata Rao that we hear from her at all. Her independence makes her story more poignant and brings the recalibrations of kingly honour more sharply into focus.

Ulsoor Narsee had been educated from childhood as a dancing girl in the Maharaja's service. She lived in the house of another woman already in his service, close to but not within the palace. The property acquired by both women was held in common, but when a quarrel broke out between the two, Narsee approached Krishnaraja Wodeyar III and asked for a share of the joint property to be held solely by herself. Narsee used the most fragile and risky of the strategies available to her, threatening to fast until her request was granted. In this, she brought subtle pressure to bear on the man who had determined her life as a palace dancer. The tactic yielded immediate rewards when the Krishnaraja Wodeyar III promised to divide the property and give her a separate share. To that, he also added ‘the promise of fifty thousand rupees in cash, besides gold, silver utensils and a set of precious ornaments’.Footnote 120

Unlike our Khadayata women, the Palace dancers in Mysore were well educated, with the ability to read and write.Footnote 121 At about the same time, missionaries working in Mysore reluctantly spoke of the devadasis’ thirst for knowledge. A Wesleyan missionary, Mrs Hutcheon, wrote of her frustrations about starting a school for girls in Mysore in the 1840s: ‘A few pretty little girls, however, refused to leave us’; ‘they were learning so much more rapidly than our first full pariah scholars, that I felt quite encouraged’. These students were children of devadasis: ‘… these hapless ones are only taught to read, that they may become proficient in learning the abominable and immoral songs contained in their own books’.Footnote 122 Narsee was also familiar with the ways of the new ‘document raj’ and knew that ‘the palest ink is better than the best memory’.Footnote 123 It is likely that she insisted that the Maharaja commit his words to paper.Footnote 124

These events occurred six or seven years before the crisis of 1831, but they reveal the fickleness of a king without meaningful power: he never kept his promises to Narsee. Seven or eight days after the transfer of the country to the Company's government in 1832, Narsee approached the Maharaja, greatly upset. He repeated his earlier promises and again corroborated his word in writing. This encouraged Narsee to stay on in the service of the palace for five or six years after 1832, but another dispute with her ‘akka’ or fellow dancer forced her to retire from Palace services.

Before the British commissioner, Narsee produced the ‘two papers which she alleged to be the two original Neroops’ whose scrutiny yielded only scepticism about her claim. ‘These papers,’ wrote Grant, ‘purport to be letters and they are both written as to an absent person.’ Only a small part of the first communication corroborated Narsee's claims:

If you are not disposed to live with your eldest sister (the other woman was so called) I will make a fair division between you of all the property given both to her and to yourself. If you are inclined to quit me and live separately, I will give you, exclusive of the partition which I will cause to be made, one complete set of precious ornaments, gold, silver utensils, cloths (and) fifty thousand rupees in cash.

Krishnaraja Wodeyar III believed his problems were only temporary when he said in the second neroop: ‘I will not abandon you because I am brought to this (condition). I am deficient in nothing to give you what is to be given to you and afford you protection.’Footnote 125 If he had earlier shown a childish prodigality in bestowing his favourites with gifts and grants of various kinds, it was in full recognition of mutually intertwined liberty and obligation: ‘To give is to show one's superiority, to be more, to be higher in rank, magister. To accept without giving in return, or without giving more back, is to be become client and servant, to become small, to fall lower (minister).’Footnote 126 Was Narsee indeed the smaller, the lower in this relationship? Did she not display the power she wielded over her male protector when she undertook a fast that quickly yielded results? Yet, under colonial rule, the economy of gifting had been deformed and a balance sheet approach to the question of the king's debts was already in place.

Perhaps it was a sign of his own reconciliation with the new economic order that the Maharaja, to whom a sceptical Grant had sent the documents for verification in 1846, possibly more than decade after Narsee left his protection, showed no obligation to an older moral economy which had bound him to honour his words. Narsee was made into a mere dancing girl—an absent person; is it any wonder that, through his vakeels, the king denied the veracity of the documents and called them forgeries? Writing to the Government of India, to whom Narsee had also appealed, the commissioner framed his opinion within the new morality that was already taking shape in Mysore, saying ‘this is not a sort of claim to enforce which the Government of India will think itself bound to interfere’. The new morality made the dancer a dishonourable figure to whom little was due under the refashioned regime of power. Needless to say, Grant's opinion was upheld by the Honor in Council and Narsee's claim was summarily rejected.Footnote 127

Private debt to public charity

We have followed here the journey of a debt through women whose traces we find in the archives only because of their failure to produce legitimate male heirs. It not only reveals the passage of a private debt to becoming a public charity, but the growing monopoly of the state over questions of by whom, and under what circumstances, inheritance could be legitimately claimed.

Once the Mysore government realized that, despite its innumerable objections, the women were indeed entitled to their inheritance, it was only a matter of prolonging proceedings long enough for the last legitimate claimant to die, when neither Hindu law, customary law, nor the principles of natural justice could stand in the way of its decisions. In 1887, Dewan Seshadri Iyer wrote to the Resident Lyall,

I recognize that the debt is payable in honour but in the present circumstances of the family … any moneys which may be paid would be squandered with little or no resultant benefit to the family … It appears that the late Damodar Dass (the original creditor) has in his will specified certain charitable endowments to be made out of the proceeds of the claim in question. I gather His Highness would be willing to pay whatever may be required for this purpose, besides paying the members of the family some suitable annuity during their lifetime.Footnote 128

Sheshadri Iyer had turned Damodar Dass's heirs into recipients of charity, rather than claimants of rights. By 1896, he was showing some impatience with the more religious aspects of the will, doubting that ‘any civilized government should spend this large sum on charities of the nature enumerated in the Will especially where, as in the present case, the claim is one whose recognition rests on the benevolence of the Sovereign’. He suggested instead that the money be set apart and invested in Government of India securities, the interest from which

should be spent on such of the enumerated charities as may be approved by the State and upon other charities (asterisked as such as for instance educational, medical etc) of a public character which the state may appoint and ordain (not being of the nature of charities usually undertaken by direct State aid).

Elevating himself to the loftier purpose of building a public charity, he recommended that ‘The objects to be selected should of course be such as will commend themselves to the people generally and tend to advance their best and highest interests.’Footnote 129

In 1899, the committee appointed to look into the possible uses of the Damodar Dass debt decided that it ‘was not in any way bound by the terms of any will purporting to be that of Damodar Dass’ and assumed the full authority to convert the money into providing support for ‘education in some form’.Footnote 130 All religious and family obligations specified in Damodar Dass's will and codicil were dropped. The scholarships that were created were of two kinds: proceeds from four-fifths of the charity fund went to the Mysore Government Damodar Dass Scientific Research and Technical Education Scholarships, for students to pursue a programme of study in England or elsewhere, and one-fifth was reserved for general and technical education of members of the Khadayata community from which Damodar Dass hailed.Footnote 131

Conclusion

It will take me too far afield to trace the path of the Damodar Dass scholarships, which tells a tale of its own. However, the debt, its long process of recovery, and its conversion into a public charity amply reflect the moment that Mysore was reconstituted as a ‘monarchical modern’ state with large powers vested in the bureaucracy. The three sets of protagonists in this long story—the Mysore Maharajas; the family of bankers, Damodar Dass and Brijlal Dass; and their female heirs and other women who were owed by the Maharaja—were by the end of the nineteenth century clearly subordinated to bureaucratic power. The bureaucrats and administrators represented principally by Mark Cubbon and Sheshadri Iyer subtly shifted between the moral and legal registers to simultaneously uphold, exempt, and undermine the rule of law. Thus, the very Maharaja who was effectively stripped of power in 1832 was exempted from being prosecuted by a mere banker on the grounds of royal privilege in the 1860s. Even in the 1840s, he was allowed to dishonour his commitments to bankers and dancing girls alike. With regard to female claimants, whether from the domestic or non-domestic spheres, the application of the law was useful only insofar as it undermined custom and therefore their economic rights. Once the latter was upheld, the women could be denied access via the tactical deployment of a new morality and by an emphasis on the capability, or the lack thereof, of women. The woman was not a sovereign, unmarked self, capable of inhering the rights to alienable property in abstract or universal terms. Yet this Dickensian archive, which documents the hopes of generations of a family and strenuous attempts to keep female legal claims at bay, allows the feminist historian another kind of access. Sandwiched between the intentions of the colonial/princely state and the patriarchal structures of the feudal family, we are allowed small glimpses of the personhood of affect.