INTRODUCTION

Philip Sidney led, as a number of biographers have recognized, a double life.Footnote 1 To modern students, he is known chiefly as a poet: the author of seductive love sonnets, a lengthy prose romance, and a pithy discourse on the role and potential of imaginative writing. Yet while some of his contemporaries did know and value his literary creations, most of them knew him chiefly as a courtier, his father the viceroy of Ireland's representative at court, the governor of Flushing in the Netherlands, and eventually a military hero. In that life he was above all concerned with the theory and practice of governance: how are societies governed, how are they best governed, and by whom? This interest in governance overflowed from his practical into his literary life and can be seen everywhere in Arcadia, both the first version and the unfinished second. And while part of it certainly originated in the political role and activities of his father in Ireland, and those of his uncle, the Earl of Leicester, in England, it seems likely that there may have been another major source: his experience of the Holy Roman Empire.

For many, knowledge of the Holy Roman Empire scarcely goes beyond Voltaire's notorious quip, “neither holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire.”Footnote 2 The current view of it is colored by the traditional English attitude to Central European affairs: quarrels “in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing,” as a prime minister put it as recently as 1938.Footnote 3 It is perhaps worth undermining that position a little by following Philip Sidney around in this polity, trying to see the empire as he saw it, and understand what he learned from its acquaintance.

PARIS TO HEIDELBERG

His first view of it was, so to speak, over the neck of a galloping horse: one can assume that his journey east from Paris in September 1572 was hurried, unplanned, and desperate.Footnote 4 During and after the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre, nobody had dared set foot outside Walsingham's embassy on the Quai des Bernardins until September 2; but as soon as the Porte St. Bernard could be safely reached and passed, the ambassador saw to it that his young English charge left the city as fast as possible—too soon for his uncle Leicester's recall order to reach him in time.

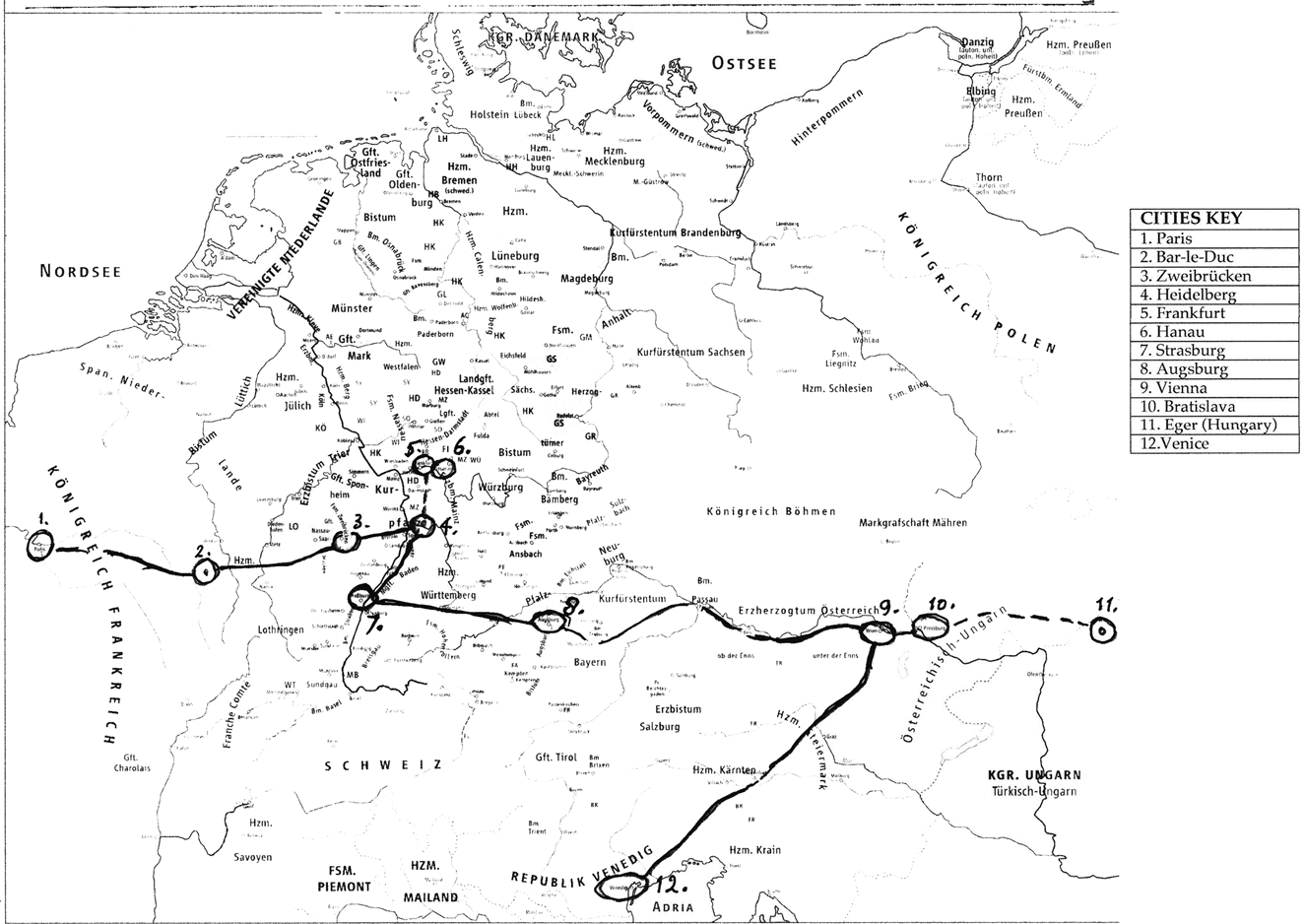

From there Sidney and his party crossed to the eastern border not by the main highways to Châlons or Nancy—the massacre had spread to the provincial capitals as well—but by the smaller road between them, which passed through Vitry-le-François and the little Duchy of Bar (fig. 1). The party consisted of six or eight horsemen, as well as a few pack animals. There was Philip himself; Francis Newton, the dean of Winchester; Lodowick Bryskett;Footnote 5 Griffin Madox; Harry White; John Fisher; and whatever servants Newton had brought. During a rest stop in Bar-le-Duc, Newton suddenly died, of unknown causes. This bothered Walsingham, who had succeeded in attaching him to Sidney's party to counteract a “lewd practice” by the young man's servants. Again, it is not known what this refers to, but Kenneth Bartlett's excellent article on the Bryskett family's secret papal diplomacy only a few years earlier may furnish the beginnings of an explanation.Footnote 6

Figure 1. The first voyage: Paris to Venice (1572–73). All images adapted from “Deutschland zur Zeit der Reformation (1547)”: Map no. 21 in F. E. Putzger, Historischer Schul-Atlas. Bielefeld: Velhagen & Klasing, 1905.

Even with a dead dean on one's hands, moving on was urgent. There were more doubtful territories to cross: a small piece of Lorraine, for example (Guise country, where Duke Charles the Great energetically harried Protestants, though he did not often actually kill them); the archbishopric of Metz, imperial and, with nearly half its population Protestant, a little easier but still too French for comfort;Footnote 7 and then at last Zweibrücken, a place of greater safety. Its Duke Johann (1550–1604) was an ally of the Reformation's most reliable fortress, the Rhine Palatinate, the goal of the journey.Footnote 8 There, for the first time since August, Sidney and his little flock could feel safe and relax. Heidelberg was, and would remain, the first of Sidney's imperial cities. It was the center of the radical Reformation in the empire. Two of Hubert Languet's friends, whom Sidney would shortly get to know, had nine years earlier produced the Heidelberg Catechism, for hundreds of years the doctrinal basis of what came to be called Calvinism.Footnote 9

Apart from a first encounter with the celebrated scholar and printer Henri Estienne (1528–98),Footnote 10 one cannot be sure exactly whom Sidney met during this first visit to the city. One must constantly bear in mind when looking at his time in the empire that he did not speak German. In educated company he might converse in Latin, but in the case of Protestant and thus vernacular churches he would have to look for something else. In view of some later advice from Languet, it seems likely that he searched out the French congregations, which—thanks to steady persecutions by Francis I and the later Valois—flourished in all the neighboring countries.Footnote 11 Sidney spoke excellent French, and would quickly have felt at home in these églises wallonnes (Walloon churches).

It so happened that the French church in Heidelberg had at this time a particularly interesting membership, which can be traced thanks to surviving marriage and baptismal registers.Footnote 12 Here when Sidney arrived were, first of all, the minister, Jean Taffin (1529–1602), a kindly and devout moderate who the following year would leave to become court chaplain to William of Orange; twenty-seven-year-old François du Jon, or Franciscus Junius (1545–1602), Orange's former chaplain and a distinguished theologian who had already led a very checkered life; Du Jon's old mentor, the elderly jurist Hugues Doneau (1527–91), and his wife; little old Girolamo Zanchi (1516–90), the great Italian Reformer who had studied under Peter Martyr Vermigli and Melanchthon, had fled the Inquisition, and had taught at Strasburg before coming here;Footnote 13 Count Rocco Guerin di Linari (1525–96), the illustrious one-eyed Florentine engineer who had fortified Metz and was now working on Heidelberg's defenses; twenty-six-year-old Charlotte de Bourbon (1546–82), the Duke of Montpensier's daughter, recently an abbess, who had left her convent of Jouarre and would three years later scandalously be married (by Jean Taffin, in the Brill) to the divorced William of Orange;Footnote 14 Bénédicte, a former nun and the wife of Pieter Dathenus (1531–88), the fiery Flemish ultra-Calvinist and former Carmelite who was Elector Frederic's chaplain and was working on a Dutch versification of the Psalms that makes Sternhold look like Shakespeare; and Charles de l'Ecluse (1536–1604), the Western world's most distinguished botanist, another pupil of Melanchthon's and about to be put in charge of the imperial botanical gardens in Vienna.Footnote 15 This was a heady mix for a seventeen-year-old English lad to meet.

Heidelberg had the third-oldest university in the empire, which now, through Elector Frederic's influence, was the most important center of Reformed learning outside Geneva. Junius and Zanchi taught there, and one of its chief and most interesting personalities was another friend of Languet's, Zacharias Ursinus (1539–83).Footnote 16 Of modest birth and indifferent health, almost pathologically shy and retiring by nature, Ursinus was tirelessly generous in his devotion to the welfare of his students and the cause of the Reformation: he ran the Collegium Sapientiae and was the only professor to visit and help afflicted students during one of the periodic plague epidemics. In spite of his shyness, Ursinus was often at the heart of the storms that afflicted the Reformation. His and Olevianus's (1536–87) catechism had been a major factor in dividing the Reformed camp; its positions on predestination and the Eucharist had enraged the Lutherans, led by Jacob Andreae, and Ursinus had been chosen to write in its defense. Shortly after this an Englishman, George Wither or Withers (1525–1605; not the poet),Footnote 17 unleashed the next tempest by defending in Heidelberg a thesis negating the right of even a godly magistrate to impose church discipline. This was denied by a Heidelberg professor, Thomas Erastus (1524–83; hence the term “Erastianism”), but upheld by the elector.

When Sidney arrived in September 1572, another battle, two years old, was nearing its ugly climax. Johann Sylvan, or Sylvanus (d. 1572), Olevianus's colleague at St. Peter's Church, had not only reformed his beliefs but gone on reforming them.Footnote 18 From Luther he had progressed to Melanchthon, from Melanchthon to Zwingli, until in 1570 he had published a confession of faith that claimed that the doctrine of the Trinity was a construction of the church fathers—one should return to the simple biblical idea of a single God the Father and Jesus the Messiah. He had written a letter to a Transylvanian anti-Trinitarian he had met at the Speyer Diet saying how he longed to move there and escape from the Palatinate's idolatry. This letter, as letters and emails will, fell into the wrong hands and ended up on the desk of the prince elector, Frederic the Pious (1515–76). He was persuaded—by no less a duo than Sylvan's own colleague Olevianus and Zanchi, the man who had fled the Inquisition—that he could not avoid an exemplary sentence. So, two days before Christmas, Sylvan was publicly beheaded in the city's principal square, with, quite possibly, a young Englishman in attendance.

Heidelberg is worth particular attention because it was the capital city for the radical Reformation, with a great university, and a center of intellectual activity. It was also one of the epicenters of just those theological controversies Languet and other Melanchthonians claimed to despise.Footnote 19 Most laymen are brought up with useful labels such as Catholicism, Lutheranism, and Calvinism. Later these might be joined by slightly subtler additions like, say, Zwinglianism or Philippism; but labels they are, and when subsequently one is confronted with polemically wielded terms such as Gnesio-Lutherans, Utraquists, Calixtines, and Ubiquitarians, eyes tend to glaze over and attention to wander. What impresses one most, though, upon entering this arena of theological mud-wrestling is the multiplicity, the uncertainty, the sense of process. These were people—singly and in groups—who were living a gigantic experiment of redefinition, the urgency of which is hard for us to understand. They were the second generation, always the most vulnerable. The Augsburg Confession, which laid down the terms of the Lutheran faith, was only just over forty years old; the Peace of Augsburg (which settled the relation between rulers and the religion of their territories) only seventeen; the Council of Trent, setting in motion the Counter-Reformation, had finally ended in 1563, nine years before. To a degree not seen for centuries, Western Christianity was in flux, in a flux of definition itself.

More will be said of this below; for now, it is good to keep in mind this continuing process of trying to fix ideas, coupled with the intensity of feeling that comes from the subject of the ideas being as important as life itself, the very parameters of body and spirit, the stuff of salvation. We are bad at empathizing and worse at sympathizing with this; whether Sidney in his late teens was so too is a question that might be usefully considered. Languet and a number of his fellow Philippists appear to have been allergic to theologians; yet, in considering, say, the various factions in an Imperial Diet, they had no doubt which represented, as they wrote, the true Religion, defining it perhaps more by its adversaries than by its doctrine.

FRANKFURT AND STRASBURG

In any event, Heidelberg was far from dull, and one suspects Sidney may have spent the winter not entirely in Frankfurt, as is usually assumed, but alternating between the two, the more as the distance between them is only just over fifty miles.Footnote 20 Frankfurt is by literary historians usually associated with the Book Fair, but there was more to the city than that.Footnote 21 In the first place, the Book Fair itself was only a part of a vast and general biannual trading fair; second, Frankfurt was in a sense the ceremonial capital of the empire. Itself, like many other cities, a freie Reichsstadt, a free imperial city, not part of a duchy but accountable directly to the emperor, it was where, by law, the election of the emperor took place, and since 1558 (with the accession of Ferdinand I) his coronation also.Footnote 22

Sidney found this second of his imperial cities in a fever of expansion, nearly doubling its size in a short time. A long wide street on the north side of town, between the first and second set of walls, the Zeil, formerly the Cattle Market, was quickly becoming a commercial center (which it still is); and it was there that another refugee from the Paris massacre was even now buying a large white house (to be known as the White House) and arranging for a printing press or two to be installed. André Wechel (d. 1581) was becoming Andreas Wechel, one of Frankfurt's greatest printers/publishers/booksellers.Footnote 23 He was a good friend of Languet's, whom Philip may have met in Paris just before the massacre, and it is likely that, new as it was, Wechel's White House was his Frankfurt lodging. He would have arrived too late for the September fair, but there were printers and booksellers galore. Once more, he would have gravitated to the French church, though to do so he had to go to Bockenheim, a couple of miles from the city walls in the territory of his later friend the Count of Hanau: here as in Strasburg, the French Reformed congregations tended to be so quarrelsome about points of principle that a decade earlier the city magistrates had exiled them to a nearby village. Oddly, this French congregation had come from England: Huguenots who had emigrated to Glastonbury in 1550 and then returned to the Continent when Edward died, settling in Frankfurt. Their minister, an intellectual from Bordeaux called Théophile de Banos (d. 1595), had been a pupil, and remained an admirer, of the murdered philosopher Peter Ramus (1515–72).Footnote 24

Frankfurt's electoral associations provided Sidney with his first glimpse of the empire as a polis, as an entity of governance. What, to the people of his time and place, was an empire? The model, of course, was ancient Rome. There had, they knew, once been a Persian Empire; and there was still an empire of the East, or of Egypt, where the sultan ruled.Footnote 25 Interestingly, the term was not (yet) applied to far-flung colonial possessions: an empire was a super state, a congeries, a grouping not of distant conquests but of proud and ancient fiefdoms under a numinous crown. Its actual government Sidney learned later, in Vienna; but its basic structures were everywhere in Frankfurt. There were, for example, seven electors: the count palatine of the Rhine, the king of Bohemia, the duke of Saxony, the margrave of Brandenburg, and the prince-archbishops of Cologne, Mainz, and Trier. These seven formed the Kurfürstenrat, the council of prince-electors, the highest element of the Imperial Estates. Next came the Reichsfürstenrat, or council of imperial princes, composed of a secular and an ecclesiastical bench. The secular bench united all those with the titles of prince, archduke, duke, count palatine, margrave and landgrave, as well as four colleges of mere counts: the Wetterau, Swabia, Franconia, and Westphalia. The ecclesiastical bench comprised all prince-bishops. A Reichsstädterat, uniting the representatives of the eighty-odd imperial cities, was of mainly advisory importance.

Frankfurt was one of the chief imperial cities, but it lay more or less in the territory of Hesse, ruled by the cautious, kind, and canny landgrave William IV (1532–92), nicknamed “the Wise.” Going there from Heidelberg was Sidney's first experience of what had for seventeen years been the empire's one great answer to the crisis of the Reformation: the principle “cuius regio, eius religio,” or “ruler decides religion.” This result of the Peace of Augsburg, agreed to with rather ill grace by Charles V, was unique, not only in its prescriptions but in its very existence and hardy survival; and it must have made a considerable impression on a youth lately fled from religion-ravaged France. The system was neither unchallenged nor without its drawbacks, but this should not blind one to the fact that it was the only organized structure of tolerance in the Western world. Because of his friendship with Languet, but also because of his own willingness to profit by this friendship, Sidney had an opportunity rare in his generation to observe this structure at work in the real world and to appreciate its qualities from an outsider's perspective.

From Heidelberg and Frankfurt he went south about ninety miles to Strasburg, his third imperial city. It lay very close to both France and Switzerland and was largely bilingual, which made it more accessible to visiting Englishmen with more French than German. Like Heidelberg, it was a city of the radical Reformation: Calvin had lived there, in the St. Thomas parish, before going to Geneva; it had been the point of contact for English Edwardians and Marian refugees; but perhaps most of all it was the city of Jean Sturm (1507–89) and his academy.Footnote 26 Sturm has not really had his due from Sidneians; but as Philip's acquaintance with him was the occasion for Sir Henry's sending Robert there as a student, this great educator of the empire may be worth a passing glance. Originally educated by the Brethren of the Common Life in Liège, he had studied at Louvain, started a Greek press there, been called to Paris's new Collège Royal (now the Collège de France) to teach classics and logic, and been invited to Strasburg in 1537 by Martin Bucer and Jacques Sturm (not a relative). A follower of Melanchthon's theological and pedagogical ideas, he started his very progressive Gymnasium in 1538, and obtained the emperor's privilege of calling it an Academy in 1562. Moreover, he had a previous relationship with England: he and Roger Ascham admired one another's work and corresponded. Sidney liked Sturm and helped him to become the successor to Christopher Mont, who had just died, as local correspondent of the English government;Footnote 27 and one of the academy's law professors, Jean Lobbet (1520–1601), became an assiduous, informative, and amusing correspondent of both Philip's and Robert Sidney's.

The man with whom Sidney lodged in Strasburg deserves a brief look, as he illustrates something very characteristic of this Western corner of the empire, both religiously and politically. From Lobbet's letters we knew him as Hubert de la Rose, an amiable citizen plagued by gout and more than a little fond of what Lobbet called purée de septembre—September mash, the red stuff that comes in bottles. But in the Strasburg archives he appears as Hubert von der Rosen, fifteen or twenty years earlier, involved in one of those parish scandals that in the radical Reformation seem to have arisen everywhere by a sort of spontaneous combustion. It is too long a story to recount here, but the gist of it was that the French church's minister was an advanced neurotic, who began by lambasting his congregation from the pulpit, for their own good, and ended up recounting his uncomfortably real battles with Satan. A group of parishioners, led by Hubert, complained to the city magistrates, whereupon the minister complained of them; eventually the magistrates got so fed up with the French church's wrangling that they closed it down, and the congregation had to travel fifteen miles to the village of Bischwiller for services. Von der Rosen, or De la Rose, had been denounced by the minister for not attending church, and had serenely stated that he had gone to the German church instead, where the atmosphere was better—which is an interesting comment on the easy bilingualism and biculturalism of this Alsatian city. Sidney, one imagines, went to Bischwiller, the more as it was also Lobbet's birthplace.Footnote 28

Another imperial personality he met in Strasburg was the Dutchman Hugo Blotius (or De Bloote; his Dutch name means “the naked one”) (1534–1608), at this time professor of ethics at the academy but whom Maximilian II (1527–76) would shortly appoint the first imperial librarian, in which position he became famous for his vast five-volume catalogue of the imperial collections and his inventory of manuscripts.Footnote 29

By the spring of 1573, then, Sidney had come to know, and know quite well, the three imperial cities of the West: those most important to sympathizers with what I am calling the radical Reformation but which might be better named the meta-Lutheran Reformation. For Easter he went back to Frankfurt for the Book Fair and a pleasant meeting with Languet; and here he also had his first introduction to the Netherlands in the person of Count Louis of Nassau (1538–74), the energetic military brother of William of Orange, who would die the following April in the Battle of Mook Heath.Footnote 30 Nassau was a small but influential county just north of the Palatinate, a member of the Franconian College of Counts. It was ruled by thirty-eight-year-old John VI (1536–1606), the second brother after William, a powerful, weighty, and serious man who had just converted himself, and thus his principality, to what in his case we may genuinely call Calvinism.

VIENNA AND HUNGARY

Now it was time to strike deeper into the empire. So, after a return to Strasburg, Sidney and his small party set out on the long journey from there to Vienna (fig. 1). It was a very long trip: even on modern roads it is around 525 miles, or 850 kilometers, crossing Baden, Württemberg, Augsburg, Bavaria, and Austria, two Lutheran and three Catholic states. Many believe that long-distance travelers went by water whenever possible; but Fernand Braudel claims that rivers were often blocked or silted, and that a multitude of tolls made water travel extremely slow and expensive. So the men would be on horseback, and the baggage—which must have been considerable, for five men touring for two (as it happened, three) years—on a string of mules.Footnote 31

When they eventually followed the Danube into Vienna, they entered the nerve center of the Germanic Empire, the city of Maximilian II's court. On a contemporary panorama, it is described as “Urbs toto orbe notissima celebrissimaque; unicum hodie in Oriente contra sævissimum Turcam invictum propugnaculum”(“the City best known and most famous in the whole world; today the only undefeated bulwark in the East against the terrible Turk”).Footnote 32 This is not what first springs to one's mind when thinking of Vienna today; but it is sometimes forgotten that Turkish-controlled territory began less than eighty miles from the city. And in that territory strange things went on. In a letter from Pressburg, Sidney was told how in the rubble of a fort bombarded by the Turks “a huge geyser erupted from the ground,” defying all attempts to stem it. So the commanding Pasha of Temesvár, having consulted his soothsayers, “gave orders to fill a Christian [a passing Serb, as it happened] up with wine, put him in a jar with rocks, throw the jar into the crater, and pile on top of it the rubble of the old fort: so that by this sacrifice the force of the waters might be broken.” And, said eyewitnesses, indeed it was.Footnote 33

Vienna, then, was a frontier city. But it was also the administrative hub of the empire and its atmosphere very much reflected the personality of its ruler, Maximilian II. Maximilian suffers, historically, from coming between his enormously powerful uncle Charles V and his peculiar, fascinating, and slightly crazy brother Rudolph II; but he was a good ruler in difficult times and an admirable man.Footnote 34 One of his great qualities was his choice of functionaries. First there were the great nobles who held the executive and ceremonial posts: men like Count Hans von Trautson (1507–89), the Lord High Steward, and Baron Rudolph Khuen von Belasy (d. 1581), the Master of the Horse. Slightly below them in rank but by no means in importance were top diplomats like Adam von Dietrichstein (1527–90) and military commanders like Lazarus von Schwendi (1522–84), both imperial councillors, the latter also a good friend of Languet's. But Maximilian had also attached to the court many of the age's foremost European intellectuals, the aulae familiares, as they were known; these were Languet's circle, and thus Sidney's chief contacts. Two of them were court physicians. The emperor's personal doctor and one of the most influential members of the court was Johannes Crafft von Crafftheim (1519–85), usually known by his Latinized name Crato, who became a friend and patron of scholars all over the empire, Languet and especially Ursinus among them.Footnote 35 The other was Dr. Thaddeus Hájek (1525–1600), who was an astronomer—he had written on the supernova of 1572Footnote 36—and had published Europe's first treatise on beer; his three sons were sent to study in England, under the aegis of the Sidney family. Blotius the librarian and L'Ecluse the botanist were aulae familiares also; others in Languet's circle were members of the university.

Here a correction is in order. Since Osborn's Reference Osborn1972 Young Philip Sidney, it has always been assumed that in Vienna Sidney and Languet lodged with the Strasburg-born humanist Georg Michael Lingelsheim (1556–1636), who was later considered as a possible tutor for Robert Sidney (1563–1626); though Béatrice Nicollier-De Weck cannot imagine why he would have been living in Vienna.Footnote 37 In fact, this has been one of those self-perpetuating errors, and as it may well have been my own, when as a young man I was helping Osborn with that book, I am glad to be able to correct it only forty-odd years later. It stems from the translation of the Latinized “Lingelius” as “Lingelsheim,” which sounds quite reasonable, especially since there was a Lingelsheim present in the Languet circle. But when I was in the Hamburg archives, looking through Languet's letter-books and Lingelsheim's own correspondence, I found that there his name is always Latinized “Lingelshemius,” which would indeed be the natural form. So then what about Languet's and Sidney's Viennese host? Eventually he appeared in a letter from L'Ecluse, in French this time, which refers to “le docteur Lingel.”Footnote 38 As such, it was possible to identify him: he was the Viennese-born Dr. Michael Lingel (d. 1585), the assistant dean of Vienna's faculty of medicine. Together with his Dutch friend (also an acquaintance of Sidney's) Andreas Dadius (d. 1583), professor of dialectic and Aristotelian philosophy, he was part of the group hired by Emperor Ferdinand, Maximilian's father, to rescue the ailing University of Vienna, much depleted by the early Reformation.Footnote 39

Languet had by now also come to Vienna, and he and Sidney spent the summer there. One of the people they saw regularly was the extremely civilized French ambassador, Jean de Vulcob (ca. 1535–1607), priest, Italophile, and lover of beautiful things. He was so impressed with the Veronese portrait of Sidney that he looked for an artist to copy it—a continuing story, to be pursued elsewhere. His assistant was young Jacques Bochetel (1554–77), who was killed a few years later at the siege of Issoire.Footnote 40 At Dr. Lingel's university that summer, the hot topic was the arrival of Jesuits. The emperor, in one of his periodic thaws toward Catholics, had agreed that Jesuits might be licensed to participate in debates. This had led to their being allowed to lecture. Lingel and the other Protestants were horrified; and, indeed, only a few years later the Jesuits would set up their own parallel arts faculty and even grant degrees. Such stories may be the basis for some of the evil remarks made about Jesuits in Sidney's correspondence.

Vienna, then, Sidney's fourth great imperial city, was where he saw the institutional structures he had learned in Frankfurt at work day by day. It was a city of urgent politics, of defense against the Turks, of administration and policy; but also a city of learned men, of pleasant botanical gardens, and of good conversation. As the heat diminished, in September, Sidney set out on an excursion. Traveling east from Vienna, he came first to Pressburg, which Hungarian speakers call Pozsony, and which, since 1919, has been known as Bratislava. At the time it was the capital of Royal Hungary (as opposed to Turkish Hungary, ruled from Buda), and Languet had a friend there also, the amiable Dr. George Purkircher (ca. 1530–77), a hospitable physician, botanist, and Latin poet.Footnote 41 How much farther into Hungary Sidney went is not sure, but from his Defense of Poesy we know that he attended at least one banquet with song and poetry. This raises the irresistible question whether on this trip he could have met young Baron Bálint Balassi (1554–94), a dashing aristocrat and the greatest Hungarian lyric poet of his time.Footnote 42 He was almost exactly Sidney's age and was currently at the fortress of Eger, or Erlau. Balassi, just the man to have given the kind of banquet Sidney describes, was most poetically—and, of course, unhappily—wooing the daughter of the Bey of Temesvár and beginning to write the verses that would make him the Hungarian Sidney.

Returned from Hungary, the English Sidney prepared to travel down to Padua, as many young Englishmen had done before him. He and his group passed through Styria and Carinthia, and crossed the mountains via the Predil Pass, only 3,800 feet but quite rugged; combined with Central Europe's notoriously bad roads, the crossing must have been an adventure for an eighteen year old from Kent. His time in Padua is not within the scope of this article; but just looking again at the route of that first year-and-a-quarter visit, it can be seen that, in a leisurely way and at firsthand, Sidney had in fact seen the whole center of the empire, from the old and learned cities in the West to the wild regions of almost Turkish Hungary in the East.

BACK TO VIENNA

The following summer Sidney set out again for Vienna, this time in new company. In Padua he had, through the mediation of Languet, met another Philip, one who also personified something crucial about the empire. Philipp Ludwig (1553–80) was Count of Hanau-Münzenberg, a scattered region just northeast of Frankfurt: the town of Hanau is now a Frankfurt suburb. He was a year older than Sidney and, having lost his father at the age of eight, had been brought up by guardians. Chief of these was Elector Frederic the Pious, the Prince of the Palatinate; another was the austere Count John of Nassau, Hanau's half-uncle, brother of William of Orange, with whom he spent three years at John's castle of Dillenburg. After a couple of years at Sturm's Strasburg academy and three more at the University of Tübingen, he was sent to Paris with a tutor, Matthew Delius (ca. 1545–ca. 1600), and a Hofmeister, or bear leader, a cultivated and aristocratic Austrian friend of Languet's called Paul von Welsperg (fl. 1575). In Paris he met Languet, who adopted him as a protégé. During the massacre he had a very narrow escape indeed,Footnote 43 went on to Basel, where he was welcomed as a relative of William of Orange and met Hotman and Beza, and eventually moved down to Padua where he met Sidney.Footnote 44

Hanau—to whom I will come back a little later—was, as a protégé of Languet's, almost another Sidney, but an imperial Sidney, a Sidney of the empire. They have certain things in common: fairly high birth (Hanau's more uncomplicated than Sidney's), a basically serious nature and upbringing (though Sidney had a sense of humor I have not found in Hanau), a perceived destiny of governance, and a tragically early death—in Hanau's case, of a mysterious and brutally sudden illness, which carried him off in four days at the age of twenty-seven.

On Sidney and Hanau's journey to Vienna, they crossed via the Brenner Pass—higher than the Predil but easier—to Innsbruck, followed the Inn to Passau and Ortenburg (fig. 2), where they visited Hanau's sister, Dorothea, and her father-in-law, Joachim Count Ortenburg (1530–1600), to console them for having the previous year lost young Anton, Count Ortenburg, Joachim's son and Dorothea's husband, and her baby son Friedrich, not yet a year old. And so on to Vienna, by now a known and comfortable city, where Sidney stayed until the following February. A new English traveler had turned up there: Edward Wotton (1548–1628), from a family that was part of the Sidneys’ Kentish circle, and who was on a very leisurely Continental tour, exercising the prodigious gift for learning languages that would one day make him a valuable diplomat.Footnote 45

Figure 2. Second voyage: Venice to England (1574–75).

Sidneians know what these two young Englishmen did in Vienna that autumn: they “gave themselves to learn horsemanship.”Footnote 46 Oddly enough, this is rarely given any attention except as the occasion for clever remarks about the Defense of Poesy. What, one might ask, was the horsemanship they had to learn, and why? And who was Pugliano, their teacher? First, why learn horsemanship in Vienna? Two or three centuries later the answer would have been obvious: even today, the Lippizaners of the Spanische Hofreitschule (Spanish court riding school), with their airs above the ground, enchant spectators the world over. In fact, the answer was just beginning to be true even then, though with a slightly different orientation. It all began with warfare, and the changes therein. No longer did knights lumber at each other with lances on vast drayhorses. The new warfare demanded light, maneuverable cavalry on light, athletic horses, capable of pirouetting, twisting and turning, and running at high speed in a charge or a pursuit. These horses were being bred in Spain out of Moorish Arab stock, and had been imported into the Spanish Kingdom of Naples. Young Maximilian, then still archduke, had been impressed with these Spanish horses, as they were called, and had founded the first imperial stud at Kladrub in Bohemia, east of Prague, in 1562. (Later his brother Charles started another at Lipica near Trieste, hence the Lipizzaner name.) And by the time he was emperor he brought up horses and a great many Spanish attendants to Vienna, and started the court riding school.Footnote 47 Here was practiced what one might call the new horsemanship, as explained by Federico Grisone in his 1550 bestseller Gli Ordini di Cavalcare (The rules of riding), which Philip recommended to his brother and which he may in fact have read even before setting out from England, as an early English version of it by Thomas Blundeville, printed in 1561, had been dedicated to Leicester. It consisted of training the horse, the mastery required for the athletic new maneuvers, and also of the art—the very Renaissance art—of making horse and rider look majestic, especially before the prince.Footnote 48

Sidney and Wotton must have been among the riding school's first pupils, at least among those having their lessons out of the rain. Since 1565 there had been a Rosstummelplatz, a horse frisking ground, beside the royal palace; but this was unusable in bad weather when it was churned quickly into mud. So just a couple of years before Sidney's arrival, one finds in the account books an order for trees to make wooden columns for a Spanische Reithalle, or Spanish riding hall: a temporary wooden structure closed on three sides and open with columns on the fourth, which—as temporary structures will—lasted one hundred years before being replaced by the magnificent riding school and Stallburg.

As for their teacher, the ridiculous Pugliano, he is so much a figure of fun in the Defense that one is tempted to take him for a fiction, as much a product of Sidney's delicious imagination as Rhombus the schoolmaster, both of them caricatures of pedantry. However, the riding instructor, I can now affirm, was perfectly real. Dr. Georg Kugler, chief historian of the Lipizzan Museum in Vienna, kindly communicated to me his findings in the Imperial Archives. “Pugliano,” he writes, “appears at the head of the lists of [Imperial] Stables staff under both Maximilian II and Rudolph II, with the title of Rossbereiter.”Footnote 49 This title, which literally means “horse-rider,” until the eighteenth century designated the head of all the stables and riding schools, with a numerous staff of almost entirely Spanish grooms and attendants: “We have payments to him for 1574 and 1576. The 1574—Sidney's year—reads: ‘Juan Pedro Poliano, an annual suit of clothes [the livery or uniform of his office], paid from the Stables budget, and a monthly salary of 30 gulden or florins; also his lodging and light from the Stables [budget]; also from the Court budget a supplement of 40 gulden.’”Footnote 50 Dr. Kugler also informs me that Pugliano appears to have been the sole Italian—probably, given his name, from Apulia, in the Kingdom of Naples—and that as Rossbereiter he was probably a gentleman, perhaps even minor aristocracy (a family of barons Pugliano had existed since the thirteenth century). It is pleasing at last to find out something definite about this egregious character. He must have been a good teacher, even if he was a monomaniac; for Sidney, true to his name of Phil-hippos, or horse-lover, was later known to be one of the best horsemen at court.Footnote 51 There are some charming illustrations of such riding lessons as the Englishmen must have had from him, in the book of the French riding master Antoine de Pluvinel, who had studied with Grisone in Naples, then worked for Henri Quatre and taught young Louis XIII the new horsemanship.Footnote 52

Languet had long been suggesting to Philip that he visit Poland for the coronation of the new Valois king. He had missed this, but the young Polish nobleman who was sent to Vienna with the invitations had told Languet that the young Englishman could always count on a warm welcome at his house near Cracow. So, in October—possibly with Wotton, or Hanau, or both—Sidney set out on an excursion to visit Poland's royal city and the house of Marcyn Leźniowolski (1548–93) (fig. 2). Poland was not part of the empire, and Sidney returned very quickly, clearly tired and disenchanted with what he, like many other foreigners, still considered a primitive and often dangerous country.Footnote 53 By December he was ill, Languet said “of immoderate study,” but the constant traveling must have been taking its toll also.

BOHEMIA

One area of the empire Sidney had not yet seen was Bohemia: in February 1575 he and Languet took advantage of the fact that the emperor was going to Prague to follow him there. On the way, they stopped over in Brünn, or Brno, where two remarkable men, Baron Jan Žerotin (1543–83) and Dr. Thomas Jordan (1539–86), introduced Sidney to one of the empire's most unusual Protestant communities, the unitas fratrum, or unity of brothers, most often known as the Bohemian Brethren. They were the remnant of the Hussite Reformation, itself based on Wyclif 's ideas, and were at this time enjoying a rare spell of imperial encouragement and freedom from persecution. For Melanchthonians, such as Languet was and Sidney was fast becoming, the Brethren were particularly interesting: their doctrine held that the love of God was all important and that theological discussion should be discouraged, and some scholars think that Melanchthon may have derived from them his concept of adiaphora—the elements of religion that, not being essential to salvation, may be practiced in different ways without scandal or danger. The Bohemian Confession, prepared for presentation to the emperor at this year's Bohemian Diet, incorporated some of their beliefs.Footnote 54

For Sidney, Brünn and Prague, the latter his fifth major imperial city, where he stayed for a short while with Thaddeus Hájek, were a lesson in the continuing imperial problem Bohemia represented. It was a Crown land: its king was the empire's heir apparent. Its nobility was proud, ancient, independent, and largely Reformed Protestant: its populace a mixture of Hussite and Catholic. For the emperor it was a continuing headache, of a kind an Englishman could understand: from the Bohemian estates he desperately needed money for defense against the Turks, while they kept wanting to talk about something else—not, in their case, the succession, but freedom of religion.

SAXONY AND HESSE

Following Prague, Sidney left for Saxony, this time in French company: with an agent of the Duke of Alençon's he had met in Prague, called Thomas Lenormand. As the map of the journey from Venice to England shows, he is now beginning to head west again—he knows that he will have to be heading back to England at some point—but he is doing so by a different route, quite deliberately visiting important parts of the empire he has not seen yet. Saxony is a most interesting case in point. It was not an ideal time for him to be going there. Just the previous year, the formidable and slightly unnerving Elector August (1526–86) had executed a complete about-turn in both religious and foreign policy. He had turned from moderate Lutheranism to Gnesio-Lutheranism, and fired, imprisoned, and, in some cases, executed all his Melanchthonian counselors. Languet, miraculously, had been spared, probably because he was both an invaluable intelligencer and far away; but it had been a very nervous year.

At the same time, August had turned his foreign policy away from a westward orientation to a northward (Scandinavian and Baltic) one: many ascribed the change to his fiercely Lutheran wife, the Danish princess Anna. So for Sidney to go there at this time meant that he really had to want to do so. From his point of view, it was an example of the downside of the Peace of Augsburg and of the ruler-decides concept: in general, that principle became controversial when the ruler did not stick to their initial choice but instituted a major change. John of Nassau's conversion to Calvinism is another case in point, though it was not as brutal as August's reversal. It is a reminder that a major part of the problem was the existence in the empire not of two but of three religions, something the Peace of Augsburg had deliberately and, as it turned out, dangerously ignored. And one might almost say that by now there were four—Lutheranism itself was increasingly divided between its moderate and its radical factions. August of Saxony's 1574 move against the Philippists (the followers of Philip Melanchthon), whom he now called crypto-Calvinists, remained within the Lutheran context, but it was quite as extreme in its consequences as if he had turned Catholic.Footnote 55

This is perhaps a good moment for a very brief reflection on the issues that so divided the parties. Apart from predestination and free will, the main problem was the nature of the Eucharist. The Lutherans, following the 1530 Augsburg Confession, held to the real presence by way of the concept of ubiquity—that Christ's divinity means that his body and blood can be present everywhere (ubique) at once. Philippists were notoriously imprecise on the Eucharist: they were not interested in what happened during the consecration but in the effects of the celebration, and were more interested in creating and maintaining the unity of Protestant churches in the face of Rome and Madrid. The Gnesio-Lutherans (in part created by opposition to the Philippists and their adiaphora: “Nihil est adiaphoron in casu scandali et confessionis” [“Nothing is indifferent in a case of scandal and doctrine”], said their theological leader, Matthias Flacius) wanted to maintain the Peace of Augsburg by way of the Augsburg Confession, strictly interpreted, and were distinguished from the moderate Lutherans mainly by their intolerance: they were strengthened by a few extremist personalities, including the fiery Matthias Flacius Illyricus (Matija Vlačić, 1520–75) from Croatia, and the Strasburger Johannes Marbach (1521–81).Footnote 56 Calvinists believed that there was a real presence but not in the elements themselves; Zwinglians that the Eucharist was no more (or less) than a memorial.

Where did Sidney stand on all this? The fascinating fact is that we do not know. Curious as it seems, he left no statement of personal religion. He translated Mornay and Du Bartas; he versified the Psalms; but nowhere does one get a clear idea of his beliefs. I suspect that as far as the Eucharist was concerned, he might have subscribed to his queen's famous answer:

Earlier I said that one should not forget the flux and the process of redefinition that was going on: here, in the struggles in Saxony as in those in Strasburg, in the Universities such as Heidelberg and in the parishes such as those in Frankfurt, Strasburg, and all over the empire, one observes that struggle, that flux, that process at work. Was it in order to see this at close quarters that he decided to go to Dresden? I do not know. What is sure is that the elector did not receive him, and that he went on to Leipzig. Leipzig was the cultural center of Saxony, and it was the home of some of Languet's oldest friends, the Camerarius family. The father, Joachim (1500–74), a great classical scholar, had recently died, but two of his sons, Joachim Jr. (1534–98), the physician and botanist, and Philip (1537–1624), the jurist, became friends and correspondents of Sidney's as they continued to be of Languet.

The final new city Sidney visited on this swing through the north-central empire was Kassel, the capital of Hesse. I have already mentioned its ruler, the quietly remarkable Landgrave William IV: he is worth looking at a little more closely, as is his conscientious young neighbor, the Count of Hanau. Languet, much involved in the continuing conflict with Spain, continually complained about the attitude of the German princes. The metaphors he used to describe them were either that of comfortable and heedless sleep or that of mildly interested but uninvolved spectators at a play. William of Hesse and Philip Louis of Hanau may help us understand this position.

William had always supported the Huguenots in France and, like other princes, had been horrified by the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre. To Frederic of the Palatinate he wrote that after Alva's depredations in the Netherlands and the new slaughter in France, only William of Orange was left: if something happened to him, “the other side will not fail to try to make use of that opportunity.”Footnote 58 At the same time, though, he remained a Lutheran, shunning theological controversy rather than plunging into it like Frederic or going to war like Frederic's son John Casimir. In part this was because, like Elizabeth, but like almost no other prince of his age, he understood the cost of war: “Our late father used to say,” he wrote, “that he would rather have 30,000 devils around him than a few thousand unpaid Reiters or Lansquenets: for devils you can chase off with a cross, but to get rid of soldiers only money or violence will do.”Footnote 59 So William steered a cautious course, concentrating on good government, the well-being of his subjects, improving the economy, and studying science.Footnote 60 Similarly, young Hanau, when in this year of 1575 he returned from his travels, was offered a high court post in Frederic's government at Heidelberg; but he refused it and settled down to unspectacular and scrupulous attention to his county's affairs. This, his biographer Gerhard Menk says, shows not irresponsibility or laziness but a clear and conscious repudiation of the Palatinate's and Nassau's internationalist and interventionist policies.

What both these choices show is that a Melanchthonian outlook and upbringing could lead to opposing types of political behavior: activist engagement against Spain and the pope, as in the case of Duplessis-Mornay and Sidney, or staying home, governing wisely, hiring no soldiers one cannot pay, and promoting peace, like William of Hesse and young Hanau. Put like this, it may also shed some light on the occasionally difficult relations between Sidney—the Sidneys—and the queen, who sympathized greatly with William's position.

It was at Easter in Frankfurt that Languet and Sidney received a secretary of Leicester's, who came with orders for the young man's immediate return to England; and so the second imperial visit, and indeed Sidney's nearly three years on the Continent, came to an end. These were his Lehrjahre, his learning years, his apprenticeship, most of it spent in the empire Languet constantly defended as the only safe place on the Continent for a young man like Philip. It is intriguing that when he went back two years later (fig. 3), in his glory as royal envoy to the new emperor, it should have been, in effect, to work against this structure of safety. For in promoting a Protestant League, he was in fact trying to persuade Lutheran princes to join their Reformed neighbors in an activism that only the Palatinate and to some extent Hesse and Nassau wholeheartedly supported.

Figure 3. Third voyage: the embassy (1577).

CONCLUSION

What, finally, had Sidney learned from his very intensive acquaintance with the empire? What he did learn was implicitly the importance of adiaphora, and explicitly the importance of princes. His Melanchthonian insistence, in all his later life and in his writings, on the role of a just prince, on the prince's crucial role in the promotion of true religion as well as the well-being of his subjects, can be explained not only by his actual experience of a multiplicity of princes and other rulers, but by his seeing the working out in reality of the Peace of Augsburg's ruler-decides principle. Only a prince could determine and, more importantly, defend whatever religion he considered true.

What he might have learned, but either did not learn or consciously rejected, was the other side of this same coin: that however imperfect this structure was, it worked, and kept the empire, at least for half a century, from becoming a daggers-drawn and sanguinary near-chaos like France or the Netherlands. It was this, not irresponsible hedonism or idleness, that kept many of the princes of the empire from joining the proffered League. The empire was not an island, as England was: it was all too permeable, and foreign wars might easily spread, like a forest fire, into the home territories—and did, indeed, for thirty years in the seventeenth century, with dreadful results. Sidney was either too young or too fiery to admit this. John Casimir might have preferred to say, too Protestant, too Reformed: the mysterious marriage proposal referred to in Languet's letters almost certainly involved Cunigunde Jacobea, Frederic the Pious's daughter and Casimir's sister, who later married John of Nassau.Footnote 61

It was the empire that taught Sidney politics beyond the narrow frame of England. It was the empire, the context of his delicate and successful mission to Rudolf II, that made him into a century-long model of an ambassador.Footnote 62 It was the empire that showed him several models of governance in action, from the cautious prudence of William of Hesse to August of Saxony's brutal authoritarianism. It was the empire, in the persons of Gianpietro Pugliano and his staff, that taught him how to control a horse in battle. It is the empire that resounds throughout the Defense of Poesy, not only in the exordium with Pugliano: “In Hungary I have seen it the manner at all feasts . . . to have songs of their ancestours’ valour.”Footnote 63 It was the empire that transformed itself into the patchwork map of the Arcadian Near East with its many states, brave knights, wise or dangerous counselors, and nubile princesses: compare the frequent mentions of unzealous sleeping imperial princes in the correspondence with Languet with the symbolically dormant Basilius. And so the Holy Roman Empire—holy in rather too many different ways, Roman in its heritage, and an empire in its always-surprising capacity to hold the incompatible together—became in five formative years the ground of experience for the life and work of Philip Sidney.