How do political parties respond to a democratic transition? More specifically, how do former authoritarian parties survive through democratic transitions, when countries implement competitive elections and abolish institutional advantages that had favored those authoritarian regimes? Although democratic transitions might be expected to weaken the incumbent political parties associated with authoritarian regimes, many such parties have performed surprisingly well in the competitive elections that follow. Prior research explains how post-authoritarian parties paradoxically maintain power through democratic transitions (Cheng Reference Cheng2006; Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010, Reference Levitsky and Way2012; Slater and Wong Reference Slater and Wong2013; McCann Reference McCann, Domínguez, Greene, Lawson and Moreno2015), focusing on the strategic incentives authoritarian leaders face and how these incentives affect post-authoritarian parties and political systems.

In this study, we add a complementary sociological perspective to the list of previous studies on the topic, by investigating how social networks both enabled and constrained the strategic decisions of post-authoritarian and challenger parties during Korea's democratic transition. Massive street protests forced the authoritarian regime to hold free and fair elections for the Presidency in 1987 and for the National Assembly in 1988. Yet, the post-authoritarian Democratic Justice Party (DJP) won the Presidency in 1987, largely because the democratic opposition unexpectedly splintered into rival parties fielding separate candidates, the Reunification Democratic Party (RDP) and the Party for Peace and Democracy (PPD). The post-authoritarians even managed a two-thirds supermajority in the National Assembly in 1990, as the RDP merged with the DJP to form the Democratic Liberal Party (DLP). These outcomes raise two crucial questions. Why did a unified democratic opposition splinter into the RDP and the PPD, and why did the RDP cross ideological lines to merge with the DJP rather than their ideological allies in the PPD?

The answer that we present focuses on party composition in the period of institutional change. By analyzing individual-level data on Korean party members and their networks in the early 1990s, we show that the existence of social ties among different parties’ politicians, or the lack thereof, explains the type of party merger in 1990, i.e. the exclusion of one of the major liberal parties. The 1990 party merger is one of the most crucial events characterizing Korea's so-called “conservative” or “gradual” democratization process (Fowler Reference Fowler1999; Slater and Wong Reference Slater and Wong2013). Our analyses suggest that the ties to economic, social and political elites built by the post-authoritarian party while in power became an important resource during the democratic transition, enabling the party to defend its position and vested interests. This sociological approach also assumes that political parties are formed and merge not only as a result of standard political factors but also due to deeper personal connections among politicians.

Social ties are concrete manifestations of trust and reciprocity (Granovetter Reference Granovetter1985; Coleman Reference Coleman1988; Putnam, Leonardi, and Nanetti Reference Putnam, Leonardi and Nanetti1994) that facilitate strategic actions such as resource exchanges and alliances (Tsai Reference Tsai2000). Conversely, the lack of social ties indicates a lack of trust, where collective action is constrained by agency and transaction costs (Granovetter Reference Granovetter1973, Reference Granovetter1985; Burt Reference Burt1992). An analysis of social network structures—the patterns formed by the presence or absence of ties—may thus reveal much about the incentive structures that rational actors face (Knoke Reference Knoke1994). In the context of a democratic transition, we argue that social networks play a crucial role in party politics, shaping the strategic options available to party leaders in emerging institutional conditions.

Towards this end, we investigate how political parties responded to institutional changes during South Korea's democratic transition, and how their choices can be understood by taking into account the social networks of legislators. Previous studies generally explained the 1990 three-party merger in Korea as a strategic choice made by party leaders to advance their political interests and maximize the probability of survival (Cotton Reference Cotton1992; Kim Reference Kim1997; Slater and Wong Reference Slater and Wong2013). Yet, the question of why the observed merger took place instead of others that offered even stronger strategic incentives remains unanswered. We find that informal yet tangible ties between the RDP and the DJP members gave their leaders the common ground needed for a party merger that cut across ideological boundaries, while the absence of such ties between other combinations of parties ruled out those potential combinations. This approach demonstrates that parties are formed and merge not only as a result of traditional factors in politics but also due to individual-level networks among political elites.

REVISITING THE KOREAN DEMOCRATIC TRANSITION

In 1987, President Chun Doo Hwan, authoritarian leader of South Korea at the time, faced a critical decision. Constitutionally barred from renewing his tenure, Chun had designated his friend and longtime lieutenant Roh Tae-Woo as his successor. Chun's plans to transfer power to Roh, however, were vigorously contested by student protesters, who quickly gained support from labor unions, religious groups, and political parties. By June even office workers had joined the protests, and well over a million protesters paralyzed the nation. With international attention focused on Korea and the country in danger of losing the 1988 Summer Olympics, Chun could not militarily suppress the uprising. Lacking other viable options, on June 29 Roh announced institutional reforms including free and competitive elections. Thus, instead of inheriting Chun's authoritarian regime through a rubber-stamp election, Roh and the post-authoritarian DJP would have to win a competitive contest.

Roh faced longtime opposition leaders Kim Young-sam and Kim Dae-jung, as well as former authoritarian Kim Jong-pil. Although Kim Young-sam and Kim Dae-jung had competed against one another for leadership of the pro-democracy forces since the 1960s, they united against Chun in the 1980s, creating the RDP in April 1987 and leading June's street protests together. Roh was also opposed by Kim Jong-pil, another authoritarian leader who had been Chun's rival until being purged and placed under house arrest. Kim Jong-pil rallied other post-authoritarian figures purged by Chun and formed the New Democratic Republican Party (NDRP) in 1987. Despite such opposition, Roh won the presidency in 1987 and even gained a two-thirds supermajority in the National Assembly by 1990, aided by two counterintuitive events.

First, the pro-democracy figures snatched defeat from the jaws of victory. Kim Dae-jung and his followers defected from the RDP and formed the PPD in October 1987, two months before the presidential election. As rival presidential candidates, Kim Young-sam and Kim Dae-jung split the pro-democracy vote in the December 1987 presidential election, respectively earning 28.0 and 27.0 percent of the vote. This allowed Roh to win the presidency with only 36.6 percent of the vote. Similarly, in the April 1988 legislative election, the DJP won the largest number of seats (125 seats), compared to 70 for the PPD, 59 for the RDP and 35 for the NRDP.

Second, the DJP, NDRP, and the RDP merged into the DLP in January 1990. While the DJP remained the largest party in the Assembly after the 1988 election, it nevertheless lacked a majority, and Roh and the DJP leadership began to consider a merger with opposition parties to reinforce their hold on the assembly. The media, and indeed the Assembly members themselves, expected one of two mergers. A DJP–NDRP merger would achieve a simple majority (164 out of 299 seats) by combining two post-authoritarian parties with similarly conservative orientations. Another possibility was an RDP–PPD merger, which would produce a pan-democratic party that would match the DJP's 129 seats. In contrast, a DJP–PPD merger would produce a party embodying radically different ideologies and policy platforms, but nevertheless commanding a large majority (199) of seats. Indeed, a high-ranking DJP member later stated in his memoirs that the DJP first proposed a merger with the PPD, and only merged with the RDP and the NDRP later because Kim Dae-jung rejected the original proposal (Park Reference Park2005).

The actual DJP–NDRP–RDP merger came as a surprise to most Korean citizens and scholars, as many believed that the RDP was too ideologically distinct from the DJP and NDRP. Nevertheless, despite the ideological gap between the parties and the exclusion of rank-and-file members from secretive negotiations known only to top party members, only five RDP members defected from the merger. The five dissenters eventually joined the PPD, demonstrating that rank-and-file members could defy Kim Young-sam. This makes the acquiescence of other RDP members even more puzzling. Another puzzle is why Kim Young-sam accepted a similar merger to the one Kim Dae-jung rejected.

The 1990 merger has received considerable attention from political scientists, who have noted the importance of political gains through merger decisions. Cotton (Reference Cotton1992) argues that authoritarian rulers repeatedly co-opted Korean opposition parties from Syngman Rhee onwards, and that the merger was only the latest incident in this tradition. Slater and Wong (Reference Slater and Wong2013) describe the merger as the DJP's effort to co-opt an opposition party in order to sustain and even enlarge its political strength under democratic rule. Kim (Reference Kim1997) has provided perhaps the most detailed explanation, leveraging coalition theory to explain why this particular merger took place as opposed to one of the more plausible alternatives. Recently, Cheng and Huang (Reference Cheng, Huang, Loxton and Mainwaring2018) also claim that the merger helped the authoritarian successor party (DJP) to credibly promise further political reforms and stability to the voters, which led to a landslide victory in the following legislative and presidential elections. In this study, we complement the existing approaches by proposing that social ties among politicians played a critical role in shaping post-authoritarian political interactions that eventually shaped the long-term political terrain of a democratized Korea. The following section elaborates how social ties among politicians affect their strategic decisions during democratic transitions.

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

What factors determine the dynamics of political parties during democratic transitions? While prior studies have widely recognized that stable party systems are crucial to democratic consolidation (Kitschelt et al. Reference Herbert, Mansfeldova, Markowski and Toka1999; Diamond, Linz, and Lipset Reference Diamond, Linz, Lipset, Diamond, Hartlyn, Linz and Lipset1989), party dynamics during democratic transition have yet to receive a thorough examination, even as party systems during democratic transition are known to be volatile (Tavits Reference Tavits2008). Indeed, the creation of new parties, the collapse of existing parties and other forms of party instability are rare in established democracies, but are far more common during democratic transitions (Harmel and Robertson Reference Harmel and Robertson1985; Tavits Reference Tavits2008). The end of authoritarian repression enables the formation of new political parties, or at least the legal incorporation of previously illegal parties that emerge into the open (Olson Reference Olson1998; Van Biezen Reference Van Biezen2005). Opposition parties that had been tolerated but limited may transform themselves into fully functional parties (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010, Reference Levitsky and Way2012). Furthermore, the institutional uncertainty characterizing democratic transitions facilitates party mergers and splits (Kim Reference Kim1997). Why certain parties form and are sustained during democratic transition while others fail to emerge or last, however, has yet to be thoroughly explained, though scholars have noted that both strategic entry (Hug Reference Hug2001) and voter support (Geddes Reference Geddes1999; Tavit Reference Tavits2008) play a role.

Political parties have traditionally been viewed as groups of individuals cooperating to enact shared ideologies and policy platforms on one hand, and to maximize their political power on the other hand. Individuals who share the same political ideologies sort themselves into ideologically homogeneous parties, partly because people who share similar views tend to sort themselves into homophilous groups (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Cook Reference Miller, Smith-Lovin and Cook2001) and partly because ideologically cohesive parties tend to be more effective, exhibiting party discipline and remaining aligned in legislative voting (Powell Reference Powell2000; Poole Reference Poole2005; Hix et al. Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2007). Thus, a fundamental premise in party formation is that party members share similar ideologies (Janda Reference Janda1980), causing cross-party differences to reflect ideological cleavages (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset, Rokkan and Mair1990). But ideological homogeneity within political parties tends to be much weaker than it might first appear (Budge, Robertson, and Hearl Reference Budge, Robertson and Hearl1987; Lorwin Reference Lorwin1971), suggesting that mechanisms other than ideology also shape party boundaries. For this reason, a large literature (Duverger Reference Duverger, North and North1954; Downs Reference Downs1957; Aldrich Reference Aldrich1995) has highlighted the political gains from party formation and mergers. Political scientists have long suggested that party leaders may care more about their own electoral survival than the implementation of their parties’ policy platforms (see, for example, Michels Reference Michels1915). Consequently, electoral success can be taken as the fundamental goal of political parties and the key factor shaping party systems (Duverger Reference Duverger, North and North1954; Downs Reference Downs1957). This opens the door to parties having much greater ideological diversity than might be expected.

Ideology and interests both bear upon inter-party dynamics. On one hand, ideologically similar parties tend to be more likely to cooperate and merge. Examples include the 1981 merger between the Social Democratic Party and the Liberal Alliance in the United Kingdom (Denver Reference Denver1983; Studlar and McAllister Reference Studlar and McAllister1996), the 1987 formation of the UMP in France, and the 2003 merger between the Progressive-Conservative and the Reform/Canadian Alliance parties in Canada (Bélanger and Godbout Reference Bélanger and Godbout2010; Marland and Flanagan Reference Marland and Flanagan2013). On the other hand, ideologically dissimilar parties may ally to maximize electoral outcomes and terms in office, and to achieve desired policy decisions (Strom Reference Strom1990; Shepsle and Bonchek Reference Shepsle and Bonchek1997). For example, communist successor parties in 1990s Eastern Europe often cooperated with nationalist parties (Ishiyama Reference Ishiyama1998). Empirical evidence suggests that the same mechanisms might also drive party mergers, despite mergers representing a more fundamental and longer-term commitment than coalitions (Bélanger and Godbout Reference Bélanger and Godbout2010).Footnote 1

Exactly how ideology and political gains drive inter-party dynamics depends greatly on the social ties between legislators. Comprised of actors as well as the social ties linking them, social networks both enable and constrain the strategic actions of individuals and organizations alike. Sociologists and organizational theorists have found that the presence or absence of a tie between any two nodes matters greatly, because actors who know and like one another tend to trust and perhaps look out for one another. While studies have examined network dynamics across several different political arenas (Knoke Reference Knoke1994; Ward, Stovel, and Sacks Reference Ward, Stovel and Sacks2011), three research streams bear directly on our focus on party dynamics. One stream focuses on friendship networks within legislatures. Caldeira and Patterson (Reference Caldeira and Patterson1987) and Arnold, Deen, and Patterson (Reference Arnold, Deen and Patterson2000) find that political friendships significantly influenced legislators’ voting patterns. A second research stream focuses on the role of interpersonal networks in party formation: Padgett and Ansell (Reference Padgett and Ansell1993), for example, argue that the Medici party in Renaissance Florence originated from the interpersonal ties of Cosimo de Medici. Finally, political scientists have recently recognized the importance of social networks in non-democratic settings (Razo Reference Razo2008; Keller Reference Keller2015). In the absence of a systematic political selection system, scholars suggest that social networks among politicians often play a critical role in authoritarian regimes.

Given the political uncertainty characterizing democratic transitions, social ties should exert important effects on political parties and their members during these periods. The interpersonal trust between connected individuals can greatly facilitate collective actions to create new parties and inter-organizational cooperation to merge two parties together under the uncertain conditions characterizing democratic transitions. As dense ties increase a group's cohesiveness (Coleman Reference Coleman1988), more densely connected groups should be more likely to coalesce into political parties. Once incorporated into a party, densely connected groups should also be more likely to remain together in that party, without splitting into rival parties or collapsing altogether.

We propose that these insights regarding social network structure enable and constrain the types of strategic actions proposed by scholars emphasizing political interests or ideologies. In a fragmented party system with a plurality rule, parties have interests in cooperating or allying formally. Party ideology provides guidance but does not explain the 1990 merger case. We claim that social networks explains the outcomes that interest-based or ideology-centered theory have not successfully accounted for. Social ties, which emerge from a wide variety of social interactions, facilitate cooperation between individuals and organizations regardless of their origins or ideology, lowering agency and other transaction costs (Baker Reference Baker1990; Powell Reference Powell1990; Uzzi Reference Uzzi1996). Thus, the presence or absence of social ties bear greatly on the incentives that political leaders face when making strategic decisions.

EMPIRICAL SPECIFICATION

DATA AND VARIABLES

We examine ties between politicians elected to the 13th National Assembly (1988–1992). We focus on Assembly members not only because they constituted nearly the entirety of important political actors during Korea's democratic transition, but also because party leaders had incentives to achieve a supermajority, a simple majority or status as the largest opposition party in the Assembly. We chose dyads of Assembly members as our unit of analysis, in order to relate party boundaries (i.e. whether or not two Assembly members belonged to the same party) to social affiliations including school and regional ties. We rely on data from the Stanford Dataset on the Korean National Assembly (Choi, Kang, and Shin Reference Choi, Kang and Shin2014), which was coded from the Republic of Korea National Election Commission (2007), the Republic of Korea National Assembly (1998) and the Choinsŭ Inmul Chŏngbo Database of prominent Koreans (2005). Of the 299 members of the Assembly, data on social relationships was available for 293 members. The 42,778 possible dyads between these 293 Assembly members represent our sample.

To analyze how social affiliations affect the boundaries of a political party, we coded whether or not each dyad of Assembly members belonged to the same party. We code party boundaries as a dichotomous characteristic of dyads of Assembly members to make them commensurate with other characteristics of dyads including social and instrumental affiliations. If both members in a dyad are affiliated with the same party, their dyad is coded 1. If two members belong to different parties, the dyad is coded 0. Considering how radically party boundaries shifted after the 1990 merger, we coded this variable once as of the 1988 election and once again after the 1990 merger. While DJP, RDP, and NDRP members would be coded as belonging to different parties as of 1988, they would be coded as belonging to the same party after 1990.

We then code variables for key social affiliations. The importance of social ties in the Korean context has long been recognized (Yee Reference Yee2000; Ha Reference Ha2007). Three types of ties have the most importance in Korea. As might be expected, kinship ties with immediate and extended family members are considered the most important. Yet, trust between high-school classmates nearly reaches the degree of trust found between family members.Footnote 2 Strong relationships are also found between individuals originating from the same regions (Yee Reference Yee2000). The family–school–regional nexus is so prevalent that it shapes business and politics in profound ways in Korea.Footnote 3 We code a dyad of Assembly members as sharing the same regional origin if they were born in the same province in present-day South or North Korea. We coded a dyad as having a high school alumni affiliation if both members spent any time attending the same high school. We also coded a social affiliation that is considered less important than region and high-school alumni relationships but that may nevertheless be worth noting, membership in the same civil society organizations. We differentiated organizations that were implicitly politicized from those that were not. Either way, past experiences working together in voluntary organizations could generate trust that would enable political cooperation.Footnote 4

To control for ideological similarity, we code affiliations pertaining to Assembly members’ ideological leanings. Dyads are coded as members of the same past political parties if they belonged to the same political parties prior to the 13th session, regardless of whether they were Assembly members at the time. We coded this affiliation as a valued tie, with some dyads sharing membership in several prior parties. We also coded a dyad as members of the same quasi-parties if they belonged to one of four organizations that functioned like parties. The minjuhwa chujin hyeobuihoe (Council for the Promotion of Democracy) was founded by Kim Young-sam and Kim Dae-jung in 1984 to carry out pro-democracy activities under political repression; it later merged into the New Korean Democratic Party in 1985. Kim Young-sam also founded the minju sanakhoe (Mountaineering Club for Democracy) for his own supporters. The hanahoe, a secret society of elite military officers led by Chun Doo-hwan and Roh Tae-woo, constituted the core of the 1980 coup. Most hanahoe members held high political office during Chun's regime. The yushin jeongwuhoe (Committee for Revitalizing Reform) consisted of proportional representatives nominated by President Park Chung-hee under the authoritarian 1972 constitution. This group served as Park's personal delegates in the Assembly and functioned as a separate political party from the DJP. Finally, we coded dyads according to whether or not the two individuals belonged to the same advisor groups. Senior political figures received advice from official legislative aides, political party advisors and policy advisors, as well as unofficial personal advisors. These advisors not only built enduring relationships with the leaders they advised, they also built ties amongst themselves. Advisor groups such as the Kim Dae-jung's Donggyodong faction and Kim Young-sam's Sangdodong faction were cohesive not only ideologically but also socially. Taken as a whole, shared membership in past political parties, quasi-parties and advisor groups features both ideological affinity and social cohesion. Controlling for these affiliations makes it possible to observe the independent effects of regional, high school, and other social affiliations.

METHODS

We analyze the relationship between membership in the same political party and social or political affiliations in two ways. First, we visualize connection patterns for each type of affiliation using multidimensional scaling (MDS), a descriptive technique of arranging nodes (i.e. what is connected) in two dimensions based on their pattern of connections.Footnote 5 More strongly tied nodes are clustered near one another in two-dimensional space, while more weakly tied or disconnected notes are repelled apart. The nodes in these analyses are the four political parties as of 1988, as well as other relevant social or political entities. These nodes are tied together by aggregate individual-level connections, where connections between individual members of these nodes are taken as connections between the nodes themselves. This technique shows the pattern of individual-level connections linking various parties and social or political entities, and consequently, how various affiliations connect pre-merger parties with one another.

Second, we conduct logistic regressions estimating the likelihood that two individuals belong to the same party. While MDS provides an intuitive visual representation of the affiliations between parties, it nevertheless cannot tease apart the effects of different types of affiliations. Further, regression analyses provide a stronger basis for making causal inferences, especially in the absence of endogeneity. Indeed, the time lag between the social affiliations (coded prior to 1988) and the two dependent variables (coded as of 1988 and 1990) reduces endogeneity concerns. Given the dichotomous nature of the dependent variables, logistic regression is employed to estimate the following equation:

The key dependent variable is whether Assembly members i and j now belong to the same political party; the explanatory variables are social and political affiliations. Political affiliations show whether i and j were affiliated to the same party in the past, included in the same advisory group, or were members of the same political gatherings. Social affiliations indicate whether politicians i and j are from the same region, attended the same high school, or shared membership in a non-political civil organization.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS

MULTIDIMENSIONAL SCALING (MDS)

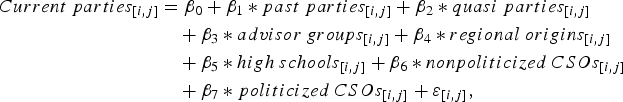

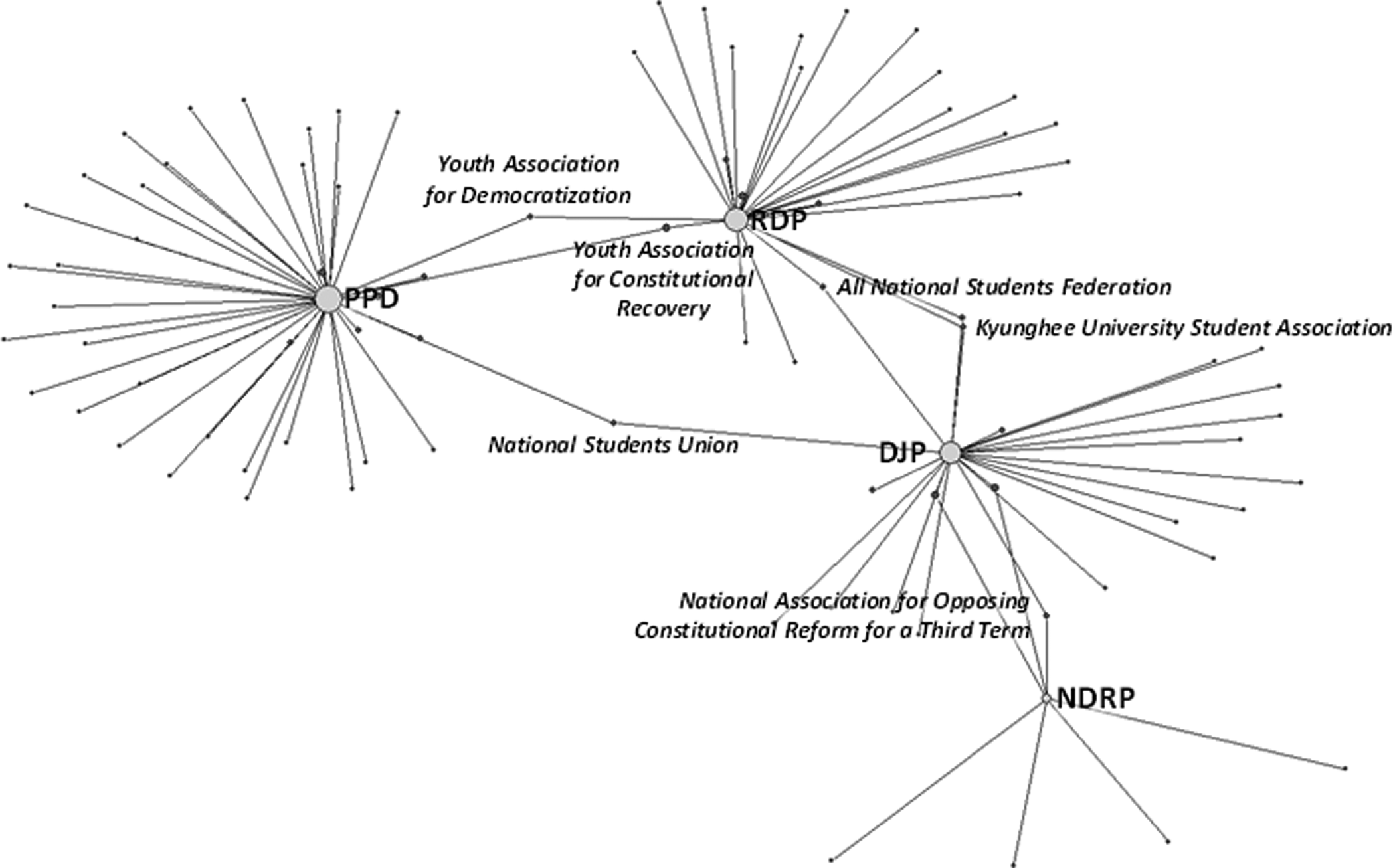

Figures 1 through 6 illustrate social networks of Assembly members from the 13th National Assembly (1988–1992). These figures show that social and political ties among Assembly members are stronger among DJP, NDRP, and RDP members, while PPD members largely do not share connections with any of the other parties. Figure 1 shows Assembly members’ regional origins as well as the political parties circa 1988.

Figure 1 Birth Province of Party Members

In this diagram, light-colored circles (i.e. nodes) represent pre-merger political parties and dark-colored circles represent provinces of origin. Lines (i.e. connections) represent the individuals in a given political party who were born in a given province. Thicker lines indicate a greater number of affiliations. MDS clusters nodes that are more strongly connected but push apart those that are unaffiliated. Thus, two nodes that are closer together in the diagram can be interpreted as being more strongly affiliated with each other, or indirectly affiliated by their mutual connections with a third node. Interpreted in this manner, Figure 1 shows unsurprisingly strong correspondences between the DJP and the RDP with the Gyeongsang region, the NDRP with the Chungchung region and the PPD with the Jeolla region. What is perhaps more surprising is the considerable overlap between the DJP, RDP, and NDRP and the degree to which the PPD and the Jeolla region are isolated. For example, while the discussion of regionalism in Korean politics mainly focuses on the cleavage between the Gyeongsang and Jeolla regions, less well known is the fact that legislative representatives born in Chungchung provinces were almost entirely absent in the PPD, representing an even smaller than those born in Gyeongsang provinces.

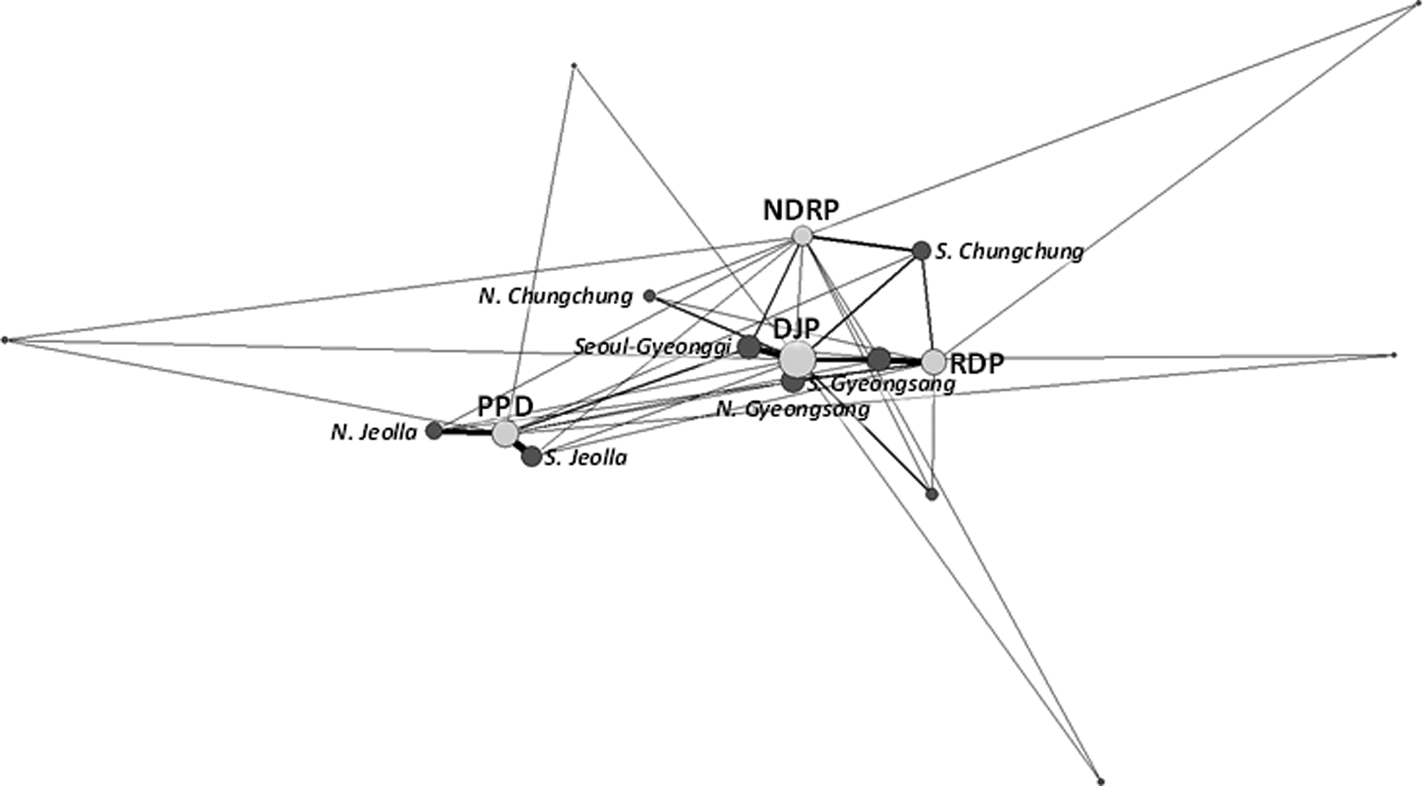

High school affiliations parallel regional patterns, perhaps unsurprisingly considering that most high school students typically remain in their home regions. As Figure 2 shows, the DJP, RDP, and NDRP draw heavily from graduates of schools in their home regions but also include many members who graduated from schools outside their home regions, especially from Seoul and Gyeonggi Province. Thus, many high school affiliations cut across these parties. In contrast, a higher proportion of PPD members graduated from Jeolla high schools, especially Gwangju #1 High School, and the PPD is consequently more isolated.

Figure 2 High Schools of Party Members

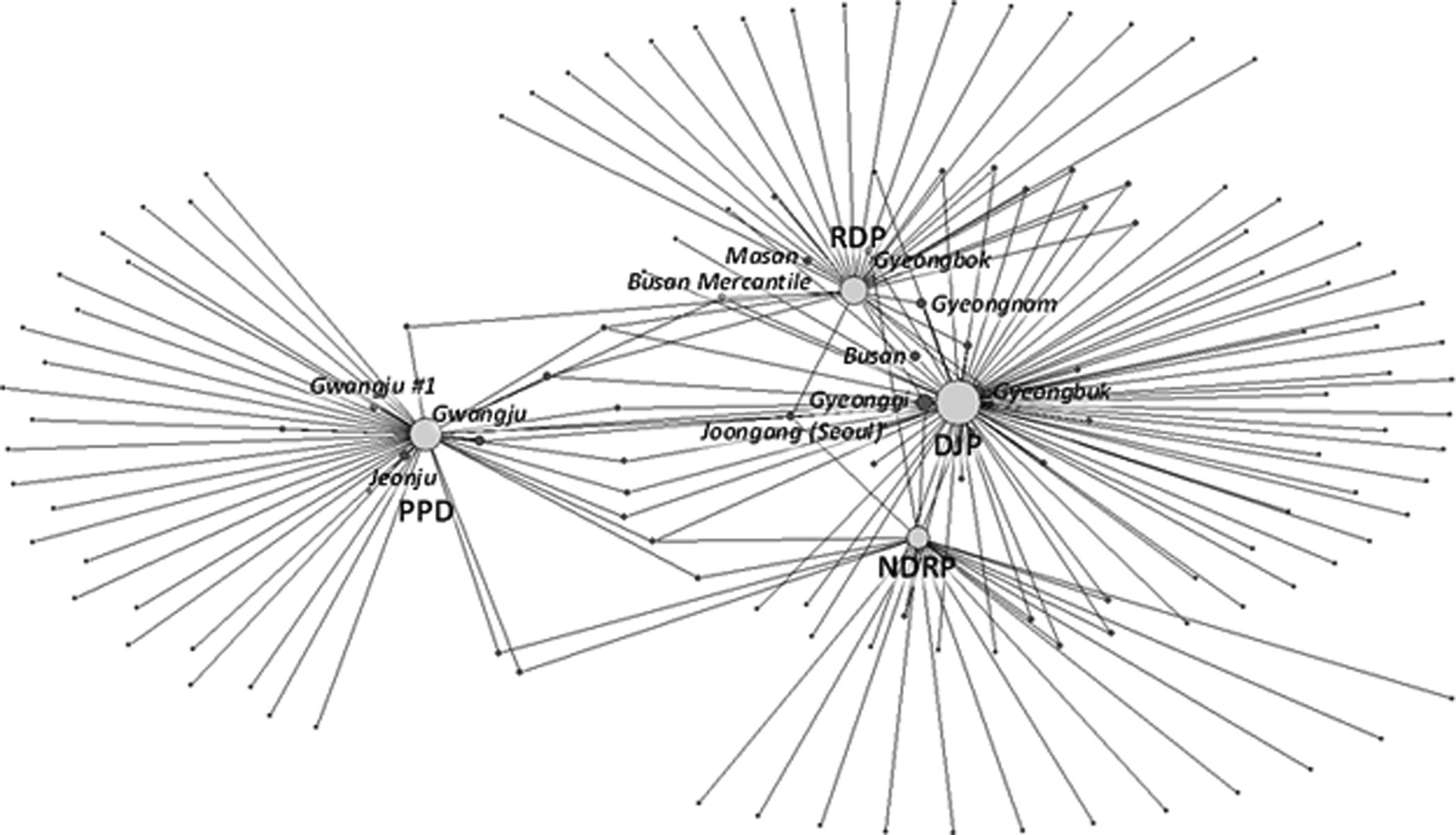

The PPD was isolated even in civil society sectors unrelated to regional origins. Figures 3 and 4 show Assembly members’ shared memberships in non-politicized and politicized civil society organizations. In both diagrams, the RDP was affiliated with the PPD and the DJP, occupying an intermediate position. Despite the RDP's ideological proximity to the PPD, however, the RDP did not have meaningfully stronger ties to the PPD than the DJP. This is somewhat surprising especially in Figure 4, where civil society organizations reflect not only social cohesion but also ideological leanings. One possible explanation is that RDP members had been allowed to participate in organizations such as the Seoul Olympic Committee and UNESCO as Assembly members alongside DJP members under authoritarian rule, when PPD members were excluded from the political process altogether. Overall, these findings support the proposition that regions of origin, high schools, and other social affiliations share a general pattern wherein the DJP, NDRP, and the RDP are cohesively connected, while the PPD remains isolated.

Figure 3 Membership in the Same Civil Society Organizations Not Involved in Political Activities up to 1988

Figure 4 Membership in the Same Civil Society Organizations Involved in Political Activities up to 1988

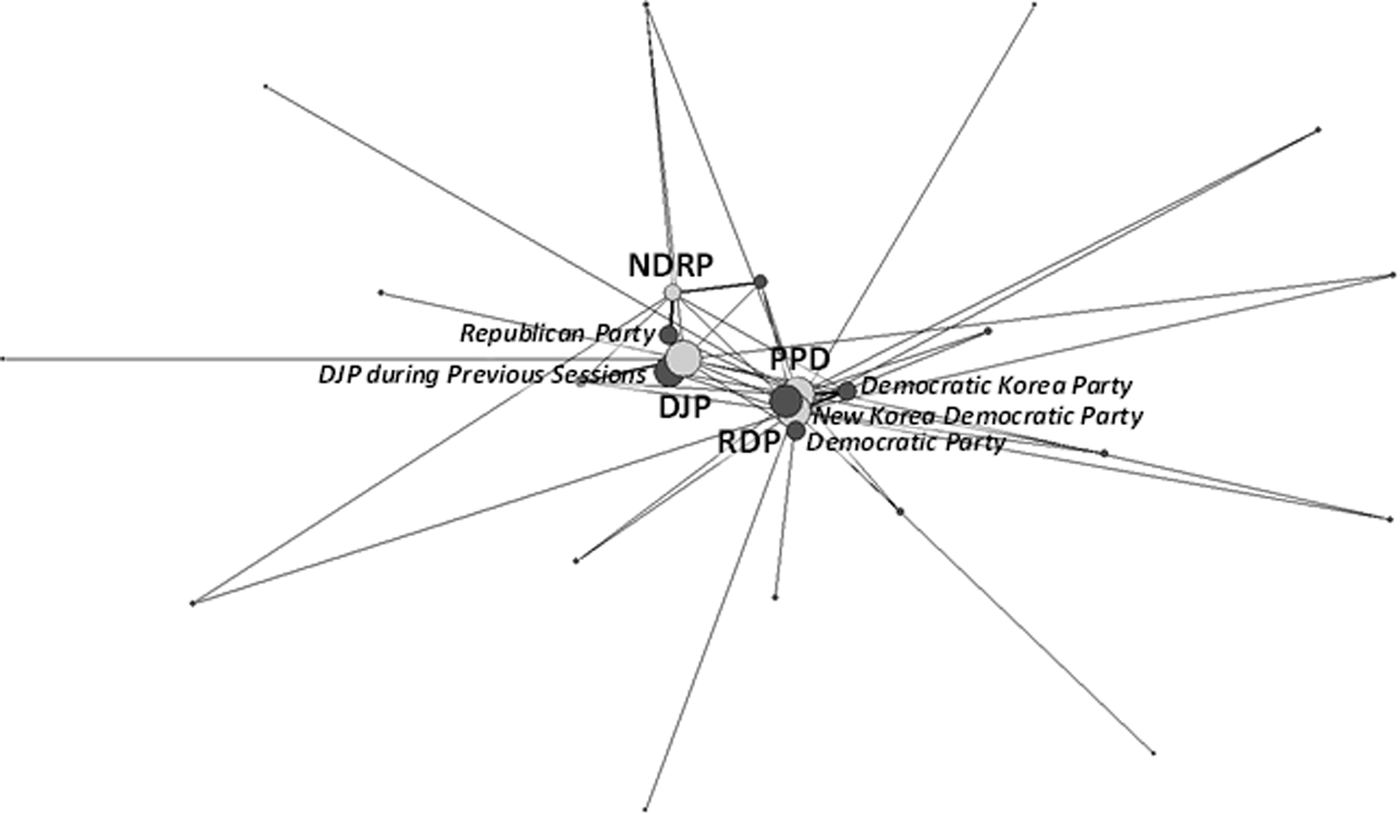

Unlike the social ties that isolate the PPD, analyses of ideologically driven affiliations clearly indicate that the ideological divide separates the post-authoritarian DJP and NDRP from the pro-democratic PPD and the RDP. Figure 5 shows not only the parties as of the 1988 election but also the historical parties with which Assembly members were previously affiliated. Each link between parties represents an individual who was a member of both parties. The core of this network consists of two distinct clusters. One cluster is comprised of the DJP and the NDRP from the 13th session, as well as past authoritarian parties such as the Republican Party and earlier incarnations of the DJP. The other cluster includes the RDP and the PPD from the 13th Assembly, as well as past democratic parties such as the Democratic Party, the Democratic Korea Party and the New Korea Democratic Party. This pattern highlights the ideological divide separating the DJP and NDRP on one hand from the RDP and the PPD on the other.

Figure 5 Membership in the Same Parties Prior to 1988

Quasi-party affiliations show a similar pattern. Indeed, the polarization between post-authoritarian and pro-democratic parties is so clear that it can be described without visualization. The minjuhwa chujin hyeobuihoe is associated only with the RDP and the PPD, while the minju sanakhoe is associated only with the RDP. In contrast, the hanahoe and the yushin jeongwuhoe are respectively associated with the DJP and the NDRP. The existence of two entirely separate groups (i.e. components) clearly indicates ideological polarization.

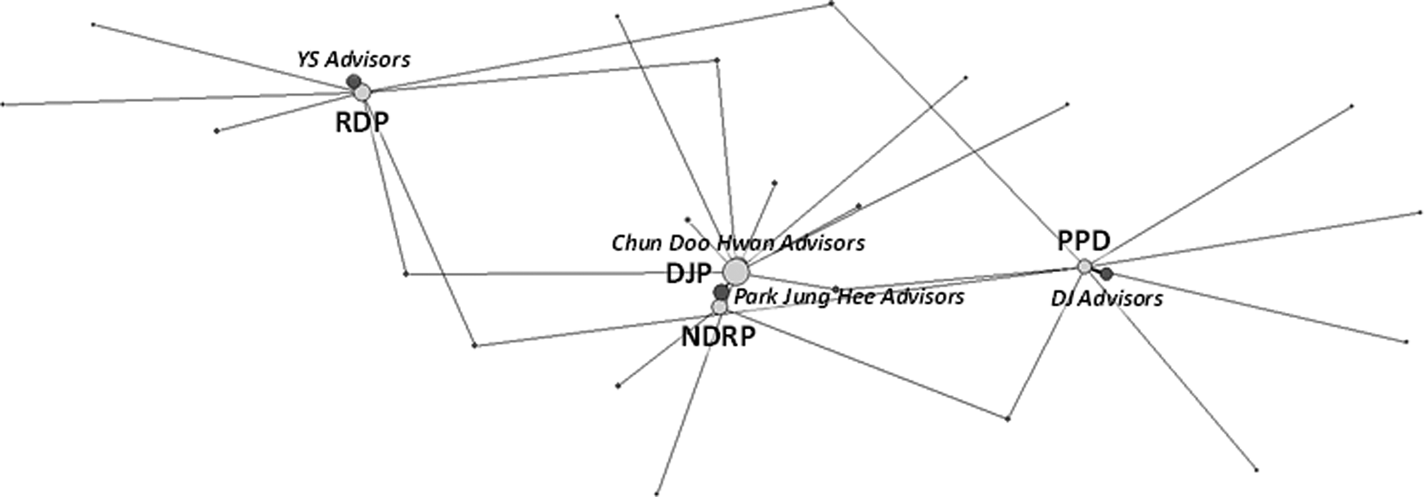

Finally, advisor group affiliations show a somewhat different pattern. Figure 6 shows affiliations linking important advisor groups and parties. Not surprisingly, there is a strong relationship between specific advisor groups and parties. To the very limited extent that members of the same advisor group belong to different parties, the RDP is as strongly connected to the DJP as the PPD. This suggests a dearth of strong ties linking the Sangdodong faction at the core of the RDP to the Donggyodong faction at the core of the PPD, removing one possible link between these rival democratic parties despite their shared ideology and policy platforms.

Figure 6 Important Advisor Groups

The illustrations of the 13th Assembly members’ political and social ties underscore several aspects of the inter-party relationships before the 1990 merger. First, prior party affiliations (Figure 5) confirm the ideological proximity between the PPD and RDP and their distance from the DJP and NDRP. In contrast, two opposition parties show a clear detachment from each other in terms of other social ties measured by birthplace (Figure 1), high school (Figure 2), and non-political networks (Figure 3), and even by social networks with strong political implications (Figure 4, 6). In all diagrams, the PPD appears relatively isolated from the other three parties, while the RDP stands closer to the DJP than to the PPD. In the following regression analysis, we statistically test whether the social ties among the three parties prior to the merger created a social basis for the merger.

REGRESSION ANALYSIS

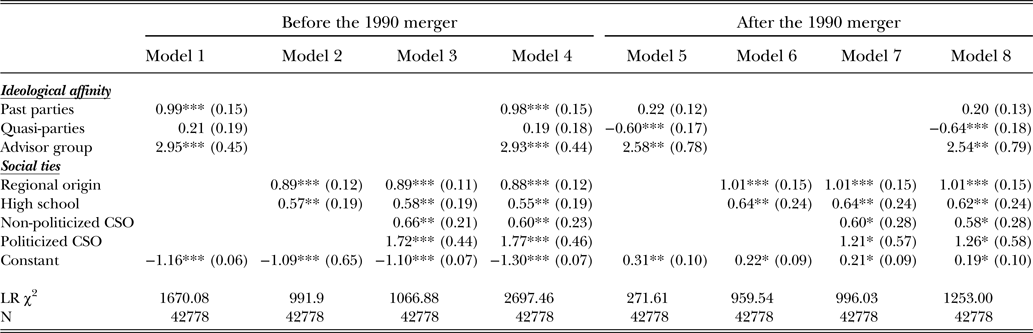

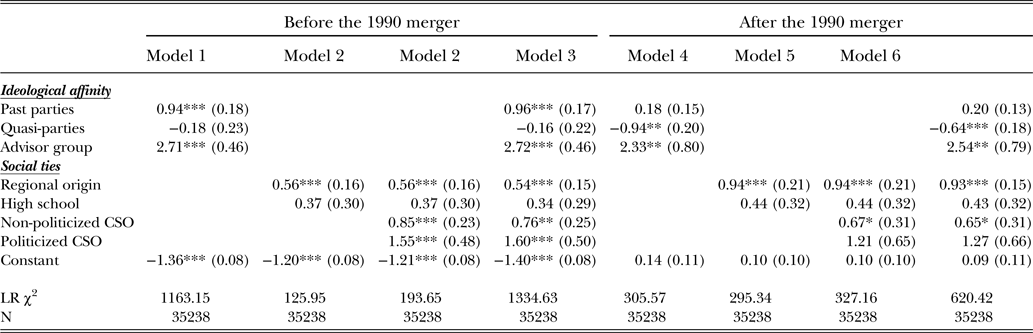

The results of our regression analysis, presented in Table 1, provide further support for our argument that social affiliations reduce the cost or difficulty of merging among the three parties. The models demonstrate that the social affiliations of interest are positively and significantly associated with the likelihood of a dyad belonging to the same party, both before and after the 1990 merger. Yet, the models demonstrate that some but not all ideologically driven political affiliations are positively and significantly associated with the likelihood of a dyad belonging to the same party. The analyses show that political networks effectively predict the probability of party affiliation before the 1990 merger, but not afterwards. Indeed, quasi-party membership is negatively and significantly associated with the likelihood of belonging to the same party after the merger.

Table 1 Estimated Likelihood that Dyad Members Belong to the Same Party

* p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001; two-tailed test.

Note: Analysis limited to dyads of 293 National Assembly members for whom data was available. Logistic regression coefficients are shown. Standard errors clustered on both members of a dyad.

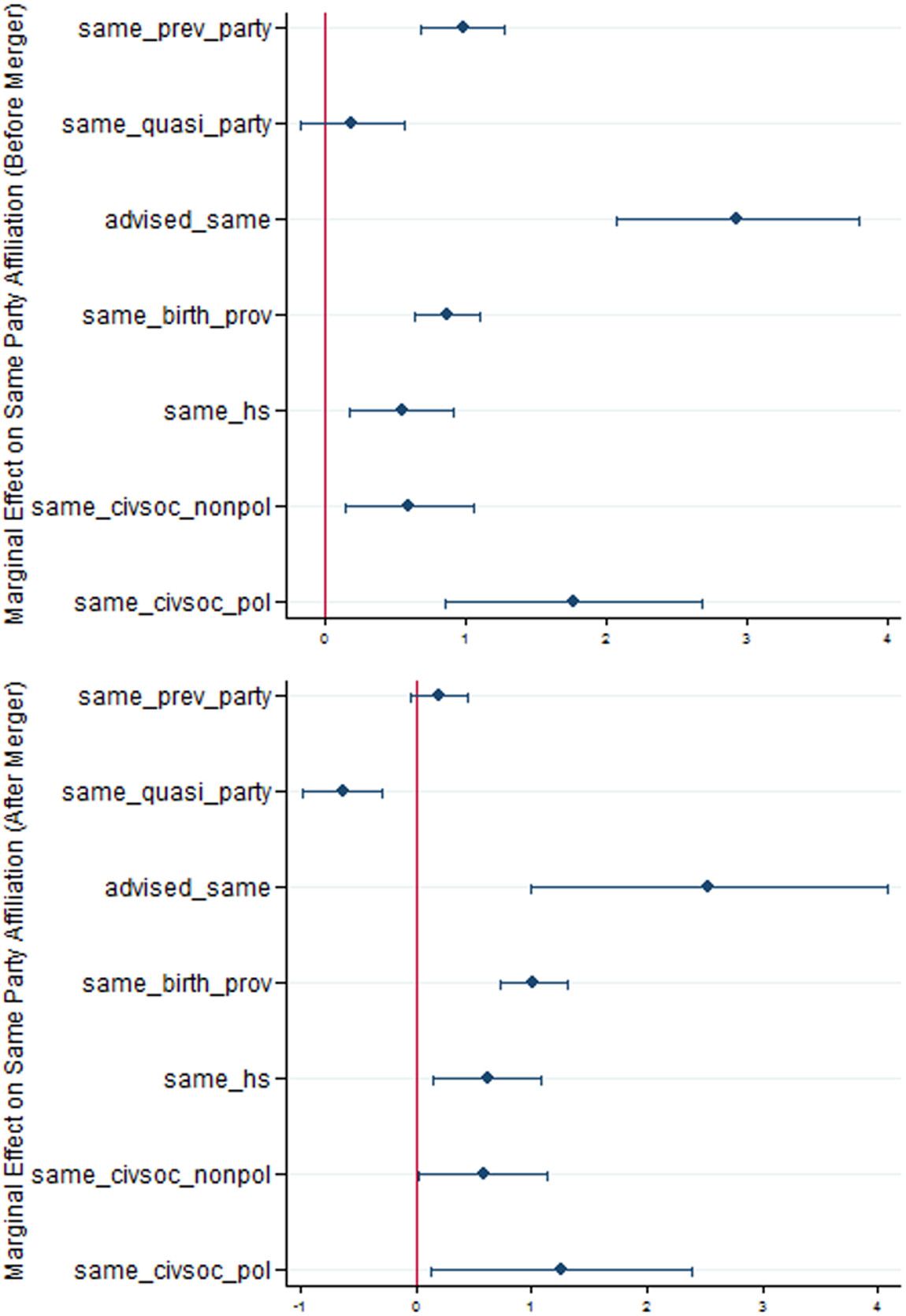

In Table 1, our unit of analysis is a dyad of two legislative members in the 13th National Assembly. Figure 7 illustrates the marginal effects of our main variables before and after the party merger based on Models 4 and 8. Models 1 to 4 estimate the likelihood that both members in a dyad belong to the same party before the 1990 merger. In Model 1, we test how ideological affinity affects party affiliation, followed by Model 2 which examines the effect of exogenous social ties (birthplace and high school) on party affiliation. Model 3 includes both exogenous and endogenous (civil society organizations) social ties. Model 4 examines both ideological and social affinity variables. Two of the three indicators of ideological affinity—membership in the same past parties and advisor groups—are positively and significantly associated with belonging to the same party. The third indicator, membership in the same quasi-parties, has no significant effect, as members of the largest quasi-party, the minjuhwa chujin hyeobuihoe, are split between the RDP and the PPD. In contrast, all four indicators of social affiliation are positively and significantly associated with belonging to the same party. These findings suggest that the boundaries of the pre-merger political parties were shaped by both ideological affinity and social affiliation, with the caveat that members of a key pro-democracy quasi-party were split between the RDP and the PPD.

Figure 7 Marginal Effects of Social Ties on Same Party Affiliation Before and After Merger

Models 5 to 8 estimate the likelihood that a dyad belongs to the same party after the 1990 merger. Again we include ideological affinity and social network first in separate models (Models 5, 6, and 7) and then together (Model 8). In these models, only one of the three indicators of ideological affinity, membership in the same advisor groups, is positively and significantly associated with belonging to the same party. Furthermore, membership in the same quasi-parties is actually negatively and significantly associated with belonging to the same party. To the extent that membership in the quasi-parties represents ideological affinity, this indicates that a dyad sharing the same ideology is more likely to be split into different parties. In contrast, all four indicators of social affiliation remain positively and significantly associated with belonging to the same party. These findings suggest that the boundaries of the post-merger parties were shaped more by social affiliation than by ideological affinity.

Model fitness (LR χ2) changes drastically after the merger, which also supports our claim. Before the merger, Model 1, which includes only ideological affinity variables (LR χ2 = 1670.08) fits better than Model 3, which includes only social ties (1066.88). After the merger, Model 5 (271.61), which parallels Model 1, fits far worse than Model 7 (996.03), which parallels Model 3. This finding highlights the value of social ties as an explanation for post-merger party membership.

The salience of regional affiliations in our analysis bears special mention. Regional identities are considered to be particularly important in Korean politics, as political mobilization based on regional origins has long been considered a key source of political cleavages. Indeed, the rivalry between the conservative Gyeongsang regions and the liberal Jeolla regions has been considered the most salient cleavage in Korean politics since the 1988 elections, affecting a wide range of political outcomes including party membership, candidate nomination and the probability of winning elections (Cho Reference Cho1998; Park Reference Park2003; Kim, Cho, and Cho Reference Kim, Cho and Cho2008; Hong and Park Reference Hong and Park2016). From this perspective, our finding that regional origins bear strongly on party membership is not at all surprising. What is more interesting, however, is that high school affiliations had a positive and significant effect on membership in the same party even after controlling for regional origins. While high school affiliations were correlated with regional origins (r = 0.15), our findings indicate that high school affiliations had a large and significant effect that was independent of regionalism. Furthermore, membership in the same civil society organizations was uncorrelated with regional origin (r = 0.02 and r = 0.00, respectively, for politicized and non-politicized civil society organizations), but nevertheless had independent and significant effects on membership in the same party.

To further analyze the effects of social ties independent from the effect of regionalism, we implement a subsample analysis where we rerun our main analyses excluding dyads of politicians who were both born either in Jeolla province or Gyeongsang province. This analysis will show whether social ties across regional boundaries affect political outcomes, and it examines whether an independent effect from social networks exists beyond the regional political cleavages.

The results in Table 2 confirm our arguments. The regional factors substantially explain the probability of being in the same party, given that both coefficients and significance levels in Table 2 decline from Table 1. Furthermore, the high school connection variable, which closely mimics the regional variable, is not significant in any models in Table 2. Nevertheless, we still find significant empirical supports for social network variables such as civil society organizations and birth province connections outside of Jeolla and Gyeongsang provinces. Politicized civil society connections after the party merger are marginally insignificant at the 95 percent confidence level but are significant at the 90 percent confidence level. This suggests that social ties have explanatory power in regions without strong ideological inclinations. Taken together, these findings indicate that social affiliations hold importance beyond what can be explained by regionalism alone, such that regionalism represents only one of several important social affiliations to consider when analyzing Korean politics. Indeed, the DJP's initial courting of the PPD as a potential merger partner, as well as Kim Dae-jung's refusal of this offer, demonstrates both the limits and importance of regionalism as an explanation.

Table 2 Estimated Likelihood that Dyad Members Belong to the Same Party (Subsample analysis excluding dyads where both were born in Joella or Gyeongsang Provinces)

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; two-tailed test.

Note: Analysis limited to dyads of 293 National Assembly members for whom data were available. Logistic regression coefficients are shown. Standard errors clustered on both members of a dyad.

CONCLUSION

Democratization needs to be understood in the context of prior authoritarianism (Geddes Reference Geddes1999). In this article, we argue that a social network approach can provide important insights regarding an institutional change where neither ideology nor political interests can fully account for patterns in the party system. We show that a social cleavage between individual politicians in long-time opposition parties under authoritarianism, the RDP and the PPD, facilitated their 1987 split despite their shared ideology. Meanwhile, cohesion along those social lines among the DJP, NDRP, and RDP members facilitated the 1990 DJP–NDRP–RDP merger. Our findings support the proposition that cross-cutting social ties or affiliations lower the cost or difficulty of mergers, while the absence of such ties or affiliations raises the costs and difficulty.

The results of this study have important theoretical implications concerning how authoritarian parties survive during democratic transitions, and what their survival means over the long term. We extend Loxton's (Reference Loxton2015) argument that post-authoritarian parties leverage the resources they accumulated while in power to expand their political base, introducing social ties as such a resource. Our findings also contribute to a growing literature on the ambiguous role of authoritarian parties during democratic transitions. Along with the Taiwanese and Mexican cases, the Korean case shows that the integration of post-authoritarian parties into an emerging democratic system induces a stable transition to democracy (O'Donnell, Schmitter, and Whitehead Reference O'Donnell, Schmitter and Whitehead1990; Slater and Wong Reference Slater and Wong2013). Yet, such a transition also allows aspects of authoritarianism to persist in the new democracy, including individual politicians, political practices and especially patterns of resource distribution. We contribute to this literature by showing that the social embeddedness of post-authoritarian parties in the emerging democratic regime affects democratic outcomes in both beneficial and adverse ways.

Our findings also yield insights regarding the development of Korean democracy. Although the 1990 merger occurred 27 years ago, its impact on Korean democracy remains profound. The merger was the watershed event that enabled the post-authoritarian party to sustain political leverage in a democratized political environment, and indeed, remain the most powerful political party in South Korea. Over the 30 years since democratization, the DLP and its successors have lost presidential elections (1997, 2002) and legislative elections (2004, 2016) only twice. Furthermore, the now impeached former president, Park Geun-hye, is the daughter of a former dictator and appointed many of her father's confidantes to key policy positions. The continuity of the DLP through democratic transition and consolidation not only shows how authoritarian incumbents can survive and even thrive, but also how they can anchor ideological conservatives into an irreversibly democratic political regime. At the same time, network-based party/alliance formations in Korean politics contributed to the long-standing regional cleavage in the country, especially the marginalization of Jeolla region. Relative social isolation of politicians from Jeolla region resulted in political isolation of the region, despite many politicians from other regions share political ideology with those from Jeolla.

Finally, although we confine our analysis to the period immediately after the democratic transition, our claim that social ties function as a political resource is a generic one. While social ties and networks exist regardless of political changes, the influence of social networks in political arenas may vary over time. Hence, we believe it is also critical to ask whether the political importance of social ties has changed during the 30 years of South Korea's democratic consolidation. Korean politics has been through various political reforms, and major corruption scandals followed by the imprisonment of numerous political figures. How these reforms and incidents might reshape the effects of social ties, especially those to major political figures, in politics remains an open question. Recently, electoral outcomes have shown some erosion in deep-rooted regionalism, which may hint at the declining importance of social ties. Meanwhile, however, the recent conservative party split suggests the continued importance of personal connections and factional politics in Korea. A systematic examination of recent individual-politician-level data merits future research, as it will demonstrate the changing value of social networks in Korean politics well after democratization.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Authors declare none.