Introduction

The Italian post-war period saw the explosion of photography as a medium of mass communication. The historical importance of this visual shift has been extensively narrated in terms of the moving image: it is well known how the films of Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio de Sica and others were instrumental in refashioning a national ethos around the experience of the war and liberation. A story still largely to be told concerns the role, momentous if more hidden, more ‘naturalised’ in the folds of social life, that photography played in ferrying Italy to the shores of democracy and modernity. If hopes of economic and political revolution were frustrated with the early onset of the Cold War, one visible index of change and sure token of western-style democracy was the increased production and circulation of images. Fascism held a strict state monopoly over the use of photographs. The exponential growth after 1945 of a popular press (newspapers, illustrated magazines and fotoromanzi) as well as personal snapshots was the tangible proof that Fascism and its closed visual order had been shattered and replaced by a new visual regime.Footnote 1 Notwithstanding the Cold War and the censorship and moralism of the Christian Democratic government, Italy was set, at least photographically, on a new trajectory. In the late 1940s and 1950s, a rising flow of photographs prepared the tumultuous economic development of the 1960s. Ambiguously balanced between the promise of modernity and nostalgia, photography heightened the nation’s visibility to itself, and contributed to moulding a new historical sense and new awareness of Italy’s position in an expanded geopolitical context.

Photography in the post-war period transitioned Italy to modernity. Through an analysis of the iconic images of Franco Pinna and Tazio Secchiaroli, two representative photographers who emerged in the 1950s, this essay will explore the confrontation between memory and modernity at the heart of this transition. Understanding the visual mediation achieved by photography is a complex affair. The images that in the 1950s compelled a nation forward – Via Veneto and a changing rural Italy, movie stars and everyday people zipping about on the first Lambrettas and Vespas – are still an inextricable part of our contemporaneity. Charged with the task of retroactively constructing a collective memory of Italy’s emergence into modernity, these photographs provide a (deceptively) immediate access to the past. Seemingly bypassing the quagmires of historical interpretation, photography affords an iconic if laconic narrative cohesiveness to the long Italian post-war and its tortuous and puzzling unfolding which came to a close with a breathtaking plunge into full-blown modernity at the end of the 1950s.

Roland Barthes commented extensively on society’s normative use of photographs to create an ‘image-repertoire’ which ‘de-realises the human world of conflicts and desires’ (Reference Barthes1980, 118). In Reference Barthes1957, he noted how modern mythologies heavily rely on iconic images, ‘indisputable images’ where ‘presence is tamed, put at a distance, made almost transparent’ (118). In the icon, myth ‘transforms meaning into form’ (131). Flattening both history and photography, myth creates an image deprived of memory but not of existence, where ‘history evaporates, only the letter remains’ (117). Modern myths adroitly sweep historical traumas and cultural contradictions under a deceptively transparent surface and inhibit the past and the power it holds to interrogate our present.Footnote 2 ‘History decays into images and not into stories’ (Benjamin Reference Benjamin2002, N11, 4). That is why the 1950s are often apprehended as a gallery of ready-made icons that transform a mystifying historical reality into a set of consoling myths. La dolce vita is one such example of how over a 50-year span a conflicted cinematic narrative morphed into a myth, even a national ethos.

Walter Benjamin’s notion of photography as dialectic at a standstill challenges this inhibiting power. Foregrounding photography’s power to inhabit the present moment with what Barthes calls an ‘absolute, original, mad realism’ (Reference Barthes1980, 119), Benjamin redefines the tasks of historical methodology: photography interrupts history and invites an understanding and mourning of the past that opens up the possibility of other histories.Footnote 3 By visually engaging with iconic photographs and their power to inhabit the materiality of the world, this essay will address suppressed histories of the post-war period. As the 1950s remain swathed in well-rehearsed categories inherited from still entrenched ideological and historical debates, photography offers a methodologically oblique point of entry for cultural historical enquiry. Exploration of the 1950s, by engaging the materiality of its visual texture and the complexity of specific photographic practices, opens up new vistas for understanding this crucial mid-century transition from post-Fascism to what Guy Debord early on baptised the global society of spectacle, in whose light – or shadow – we are still living (1997, 53–64).

The icons

The belated photographic boom in post-war Italy gave rise to photographic practices at once intensely vernacular, yet endowed with a global reach: paparazzismo and ethnographic photography. This essay will focus on Franco Pinna, photojournalist, ethnographic photographer, and later set photographer for Fellini, and the way his work intersected with the activity of another photographer, the original paparazzo, Tazio Secchiaroli. Two sets of photographs shot a few months apart at the end of the 1950s will evoke in a flash the historical constellation of modernity and tradition within which the Italian 1950s unfolded.

Figure 1 Tazio Secchiaroli © Tazio Secchiaroli/David Secchiaroli

‘Aiché Nanà. The striptease that changed Italy’, announced La Repubblica on the fiftieth anniversary ‘of the sinful night which inaugurated la dolce vita’ (5 November 1958).Footnote 4 The photo is part of a sequence, shot by Tazio Secchiaroli, of the Lebanese belly dancer Kiash Nanah, alias Aiché Nanà, stripping in the nightclub Rugantino during the birthday party of a young Roman aristocrat (Figure 1). In attendance were some of the characters who, in a year’s time, will be playing themselves in Fellini’s La dolce vita (Anita Ekberg and Laura Betti among others).

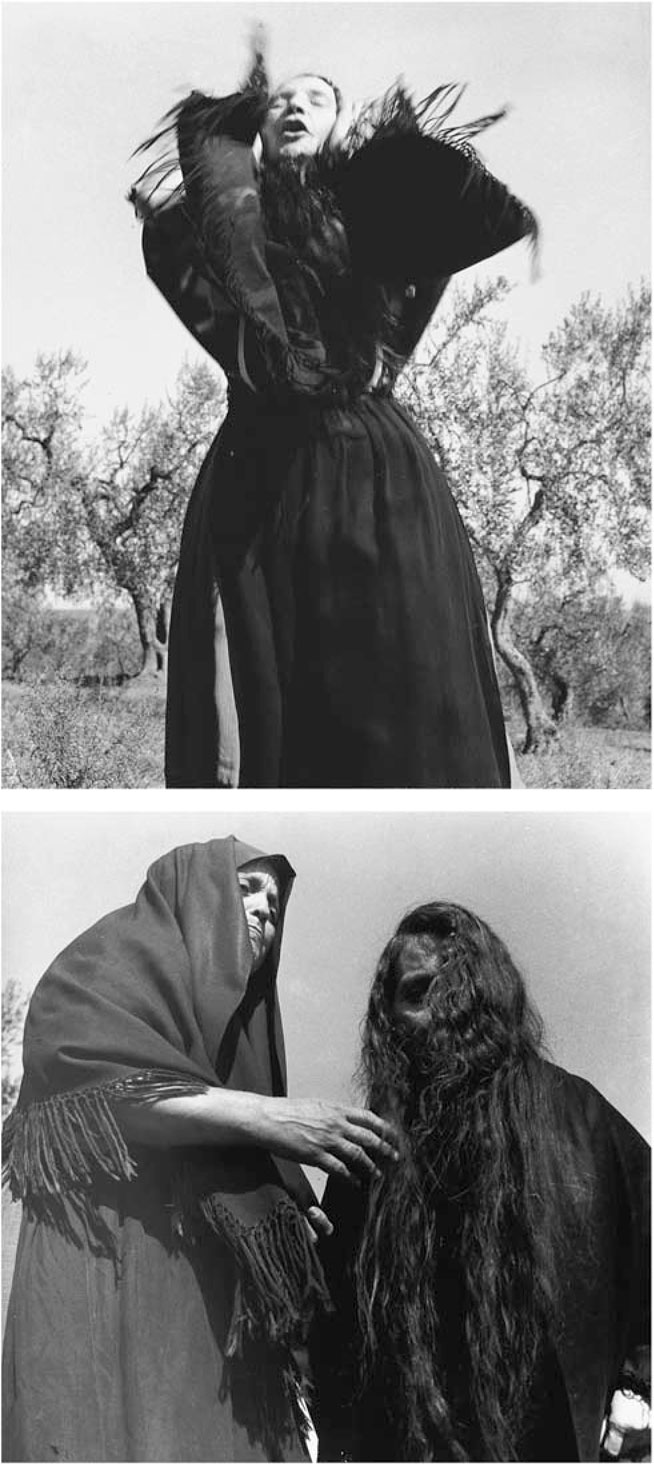

Figure 2 Franco Pinna

Between 20 June and 10 July 1959, Franco Pinna, working with a team led by anthropologist Ernesto de Martino, records in the southern region of Salento the ritual to heal the peasant Maria di Nardò (Figure 2). Afflicted by the ‘return of the bad past’, symbolised by the bite of the tarantula, the woman withstands the crisis by giving it symbolic form before relatives and hired musicians through dance and music. The photographic sequence would appear in de Martino’s study of tarantismo, La terra del rimorso Reference de Martino(1961).

These images are iconic condensations of the apparently incommensurable cultural horizons defining the national imaginary of 1950s Italy: la dolce vita’s promise of a tantalising future, and the ancestral and unmoving past of la terra del rimorso. The 1950s as a space of cultural transition finds a puzzling, emblematic expression in this encounter. What do mourning practices and la dolce vita, taranta dance and striptease, have to do with each other? To unravel the dialogue between these photographs, it is necessary to journey outside the frames, into the surrounding historical, cultural and geographical landscapes. To explore how Italy, through photography, visually negotiated the persistence of the past and the advent of modernity, the essay will first trace a genealogy of political action photography leading to paparazzismo and to ethnographic photography, and then examine the significance of the journey to the South. De Martino’s theorisation of remorse is a central idea to understand the 1950s. Focusing on Pinna’s photography and de Martino’s ethnography as sites where post-war Italy faces the intractable realities of death and the return of a ‘bad’ past, the essay will explore how ritual mourning interrogates an amnesiac culture of benessere, thus exposing history as a modern repressed.

Cold War and Blitzphotographie

By the midpoint of the twentieth century, photographers had emerged as the ambiguous heroes of modern times. Whether real life photojournalists like Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson, or fictional figures like L.B. Jefferies, ‘Jeff’, in Rear Window (1954), and Dick Avery in Funny Face (1957), photographers seem to embody the enigmatic epic of late modernity with its forever expanding and morphing society of the spectacle. Franco Pinna and Tazio Secchiaroli are specific Italian iterations of these modern visual argonauts.Footnote 5

Photography for Franco Pinna started as a political act. At the beginning of 1950 he joined the Communist Party and became a photojournalist, bringing to it both the energy and fearlessness of a man who does not shy away from trouble.Footnote 6 The photograph he took in Rome on 16 May 1952, during a surge of street demonstrations protesting the visit of General Ridgway, commander of the NATO forces, is a good example of his aggressive reporting style.

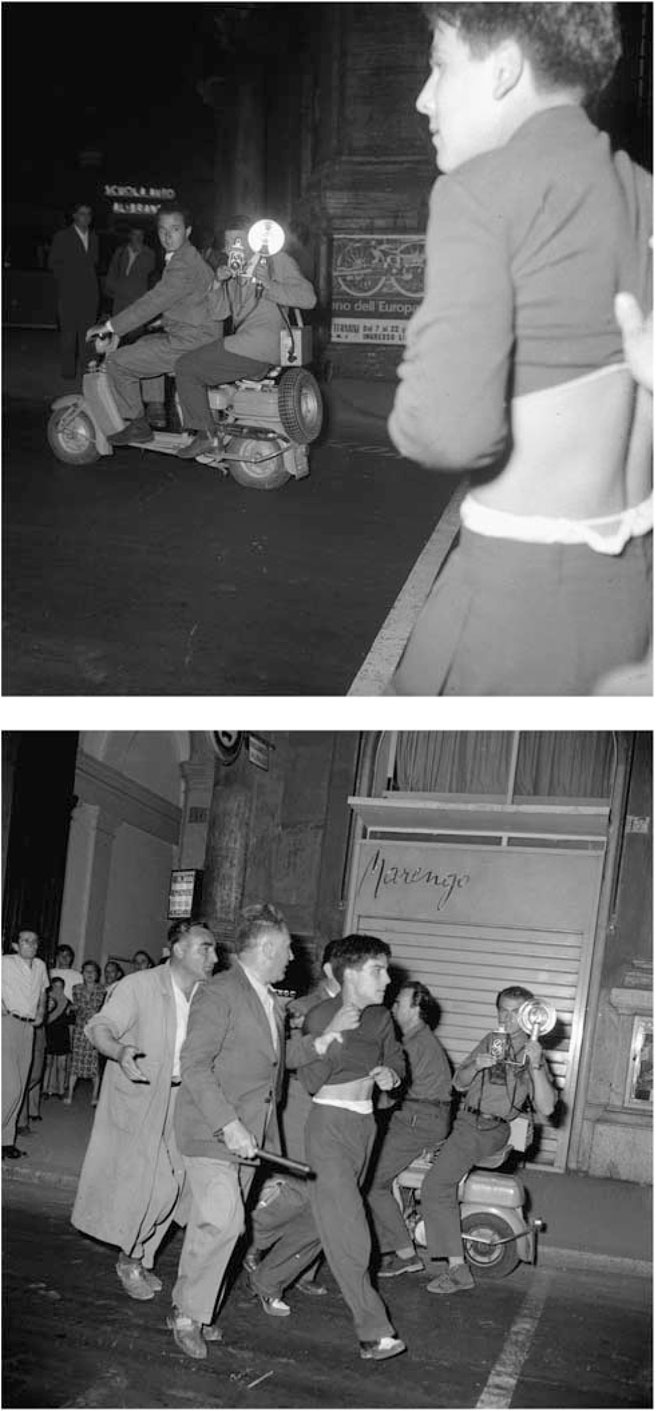

Pinna documents the unrest in Largo Chigi by photographing beatings by plain-clothes policemen and then escaping on a scooter. What was caught in the flash of his camera? (Figure 3). In the foreground, the overexposed silhouette of the arrested demonstrator and, in the dark background, another photographer, Luciano Mellace, shooting the same picture from the back of a Lambretta driven by Tazio Secchiaroli. The result is a mirror image of Pinna in the act of photographing (Figure 4). Nobody knew it at the time, but the real breaking news of this scoop was the self-reflexivity of the images: a self-portrait of photographers as new heroes of the emerging media society. With a shift – soon to be theorised by Marshall McLuhan – the actual event in its materiality and historical specificity is wiped out in the crisscrossing of the flashes while the medium emerges as the ultimate and lasting message. This photographic diptych has since become so iconic it is routinely misidentified and flattened under the rubric ‘the age of the paparazzi’. The playfulness which evokes later scenes of Via Veneto erases the harsh and obscurely violent years of the Cold War, as if the early 1950s never happened, as if the miracolo economico took off soon after the end of the war.Footnote 7 This desire to do away with history is inscribed on the very body of Pinna’s photograph, often cropped to eliminate partially or entirely the figure of the demonstrator. By cutting the 1950s out of the frame, the present does away with contradictory, troubling, unresolved histories and their visual and existential residues – in short, the possibility of seeing and understanding differently.

Figure 3 Franco Pinna portraying Tazio Secchiaroli and Luciano Mellace and Figure 4: Luciano Mellace portraying Franco Pinna

Tazio Secchiaroli, before being baptised by Federico Fellini as paparazzo, was also a communist militant from Cento Celle.Footnote 8 He recorded Italy’s political tensions in the early 1950s, like this dramatic street fight in 1953 between neo-fascists and workers from L’Unità (Figure 5) or the iconic Altare della patria (1956; Figure 6) depicting a demonstration of young neo-fascists in Rome. Neo-fascists, friars and celerini (the post-war anti-riot police) were the iconic currency of the 1950s before la dolce vita invaded the streets of Rome. It is against a history of repression and restoration that the final Italian take-off into modernity at the end of the 1950s has to be read. A few events are worth remembering. The Vatican, after its massive intervention in the 1948 elections (which saw the victory of the Christian Democrats), kept casting a long shadow on Italian political life. In 1949, the Pope excommunicated the Communists and in 1953, he openly supported the referendum on the legge truffa, which would have granted a super-majority to the coalition that reached 50 per cent-plus-one votes. After its 1952 electoral success in the south, the MSI, the neo-fascist party, was silently accepted as a democratic player in defiance of the constitutional article prohibiting the reconstitution of a fascist party. Finally, the history of the 1950s is dotted with the systematic suppressions of worker and peasant demonstrations: from Modena, where in 1950 six workers were shot to death by the police, to Mussomeli in Sicily in 1954, where four people died while protesting the lack of water, and Reggio Emilia in 1960, where five people were shot while protesting the right-wing Tambroni government.

Figure 5 Tazio Secchiaroli © Tazio Secchiaroli/David Secchiaroli

Figure 6 Tazio Secchiaroli © Tazio Secchiaroli/David Secchiaroli

Taken during the most repressive years of the Christian Democratic regime, these images document the emergence of a new kind of photography, aptly baptised by critic Giuseppe Pinna as Blitzphotographie. These photographs offer a revealing peek into the political and social reality of conflict and violence which characterises the early 1950s – police beatings, the persistence of fascism, the collusion between the Church and political power. Portraying ‘graceless yet very vibrant actions’ (Pinna Reference Pinna2002, 12), Blitzphotographie sets itself radically apart from the measured style and formal balance of Henri Cartier-Bresson, the photographer often invoked as a critical point of reference. Pinna and Secchiaroli do not freeze a ‘decisive moment’, but rather ‘the heat of the moment’; one ripe with unknown possibilities. Going beyond the generic intent of documenting, Blitzphotographie is explicitly political. Although brief, this practice and its under-theorised body of work is a crucial point of departure for understanding some of the most innovative developments in Italian post-war photojournalism, paparazzismo and visual anthropology.

Inspired by Magnum Photos, the photographic agency that Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson founded in 1947, Pinna and his friends Caio Mario Garrubba and Plinio De Martiis started the co-operative Fotografi Associati in 1952. This initiative expressed a new consciousness of the photographic profession and the desire to create, within the highly balkanised world of the Italian publishing and information industries, an independent space for critical photojournalism. The experiment was short-lived. Despite the efforts of this new generation, photography retained a subaltern status within Italian culture: photographers were rarely credited for their work; steady employment was non-existent.Footnote 9 As the decade wore on, the activist photographers either became paparazzi or gravitated to the glamorous and moneyed world of cinema (in the 1960s both Pinna and Secchiaroli would become set photographers for Fellini).

Born as an act of engagement, Blitzphotographie was tamed into a more socially acceptable and economically viable product, those sly images of the paparazzi. As suggested by the title of a 1981 collective history of the field, L’informazione negata (Negated News), this taming amounted to the successful stifling of critical photojournalism. The story of Secchiaroli is one of cultural adaptation to an environment where political and market forces exerted an intense ideological repression. This ‘liberal’ visual regime successfully deflected the transgressive eye of the camera from news to visual anecdotes (those beloved by Mario Pannunzio, the legendary editor of Il Mondo), from politics to gossip (think of the Montesi scandal), from street events to the staged world of high society and cinema.Footnote 10 The boundaries delimiting Italian photography run along the same perimeter tightly enclosing post-war Italian democracy. In recent nostalgic accounts depicting a mythical golden age of photography, this story of co-optation has been transfigured into the quintessential example of Italian freewheeling inventiveness, paparazzismo becoming the unique, home-grown version of photo reportage.Footnote 11 Reversing ‘the derogatory connotation of the label paparazzo, reinventing Fellini’s neologism in ideal terms’ (Sekula Reference Sekula1984, 28), these accounts pre-empt a critical understanding of post-war Italian photojournalism and, in the end, do a disservice to Secchiaroli himself.Footnote 12 It is not the scoops of startled starlets and disgraced political figures – Daniel Boorstin’s ‘pseudo-events’ instigated by the photographer (1964, 39–40) – that make the work of Secchiaroli memorable, but the photographs where he daringly placed his camera in the middle of the street, taking the emotional pulse of historical upheavals.

After facing each other on Largo Chigi, Secchiaroli and Pinna proceeded in opposite directions. The Aiché Nanà sequence, at once sensationalistic scoop and document of socio-cultural change, is a crucial point of passage in Secchiaroli’s photography. Pinna, on the other hand, chose to remain political. Taking Blitzphotographie to the geographical margins (the South, the suburbs of Rome, his native Sardinia), he realised an important body of ethnographic photography.

The ethnographic expeditions

Between 1952 and 1959, Italian anthropologist Ernesto de Martino organised a series of expeditions in Lucania and Salento. The journeys produced a vast collection of song recordings curated by Diego Carpitella, and a rich body of photographs by Arturo Zavattini, Ando Gilardi and Franco Pinna. The first expedition was in the summer of 1952 to Tricarico, the hometown of activist poet Rocco Scotellaro. The event was widely publicised in the leftist press in connection with Cesare Zavattini’s Bollettino degli scrittori, a call to Italian writers to expose the hidden realities of the country.Footnote 13

Born from the desire to document, the journey to the south is in itself a fascinating record of the political and utopian yearnings of an intellectual class dispirited and marginalised within the conservative post-war order. But de Martino’s ethnographic journey, straddling the line between science and politics, soon moved beyond the narrowing horizons of neorealism. As anthropologist Clara Gallini has suggested, Lucania, for de Martino, ‘becomes a place from which to interrogate one’s self and others, in order to find in both the traces of a communal history’ (2000, xxxvi.). The photographic surface is the complex visual materialisation of that ‘place’. Engaging their various registers as documents, modern iconic images and dialogic spaces of questioning, Pinna’s photographs afford what Clifford Geertz calls a ‘thick description’ of de Martino’s ethnographic encounters and post-war ‘neomeridionalism’.

Introduced by his friend, the anthropologist and photographer Franco Cagnetta, Pinna joined de Martino in his second expedition in the autumn of 1952. Travelling through various villages in Lucania, armed with a Rolleiflex, Pinna shot 150 black and white photographs, now mostly lost, and a documentary Dalla culla alla bara, also lost.Footnote 14 During this trip, de Martino shifted his attention from ‘background ethnography’ (Faeta Reference Faeta1999, 86), the general description of a socio-cultural reality as shown in Arturo Zavattini’s photographs (Figure 7 and 8), to the structural study of specific religious and magical practices, in particular peasant rituals of mourning and healing.

Figure 7 Arturo Zavattini, 2 June 1952. Female costume, La Rabata, Tricarico and Figure 8: Arturo Zavattini, 2 June 1952. Interior, Tricarico.

Photography played a crucial, yet implicit role in ‘focusing’ de Martino’s gaze.Footnote 15 While he is rightly credited as having inaugurated visual anthropology in Italy, his relationship with photography was uneasy.Footnote 16 After the first trip to Tricarico, Arturo Zavattini was not invited back; Pinna, who took his place and became a steady collaborator, saw his photographic production treated in an ancillary, even dismissive way.Footnote 17 During field research photography was expected to keep a low profile, striving for invisibility. Yet what now jumps out from Pinna’s photographs is exactly the one event which at the time was taken for granted: the improbable but startlingly real encounter between an archaic world of ritual and the silent harbinger of technological modernity, the camera.

Techniques: lamentation and photography

The few images left of Pinna’s 1952 reportage focus on the funeral lament, the core of de Martino’s research for Morte e pianto rituale (Death and Ritual Mourning). First performed in the house of the deceased in preparation for the burial and then repeated at established times in the weeks and months to follow, the lamento displays a religiosity suspended between pagan and Christian practices.

These powerful images show Grazia Prudente and Carmina di Giulio, the lamentatrici of Pisticci, professional mourners hired by the families of the deceased (Figures 9 and 10). Pinna’s visual style is strikingly different from the distanced, peacefully descriptive images taken by Arturo Zavattini the previous summer (Figure 7 and 8). In these photos, as in a conversation, the camera at once addresses and is boldly addressed by the women. Pinna’s style drives home the fact that photography is the product of a ‘mediation between two subjects who represent each other within fields of reference at once near and distant . . . a practice of negotiation between two diverse visual orders’ (Gallini Reference Gallini1999, 25).Footnote 18 The effect is one of an unfolding communication, in which the ritual constructs itself for the camera, while the camera responds to the visual order of the archaic gestures. In the halved figure, with and without a face, as if poised on the threshold of two worlds, Pinna caught an emblematic embodiment of the condition of mourning.

Figure 9 and Figure 10 Franco Pinna

The setting for all these images is in a forlorn, atemporal countryside. There is a precise reason for this. The mourning ritual can be performed only for the dead. To lament without the dead would bring bad luck. Only after the mediation of Vittoria de Palma, the social worker who accompanied all the expeditions, did the women agree to act out the lamentation for the ethnographic team, but only far away from the town.

The fact that the lamentation is a reconstructed performance for Pinna’s camera raises questions about the authenticity of the ethnographic event. Nonetheless, it was exactly the command quality of the performance which revealed the defining feature of the ritual to de Martino: its repeatability. Whether ‘real’ or fictitiously recreated, the lamentation is always staged, a highly codified ‘crying without a soul’. The ritual lamentation is a technique to construct the dead and, in the process, the living as distinct elements. Through this symbolic practice the bereaved can transpose her own loss into an alternative reality, which de Martino calls ‘metahistory’, where the painful event can be ‘de-historified’, a necessary step to allow the mourner to re-enter the historical space of the community. This ‘ritual theatre’ gives form to a potentially annihilating emotion, wavering between the two poles of catatonic depression and violence (the paroxysmal gestures of the standing figure), that de Martino defined as the ‘crisis of presence’.

Photography’s input into de Martino’s theorisation is crucial. By isolating iconic gestural units, the camera reveals the structural organisation of the lament according to a modular, repeatable sequence of gestures – the hands raised to the head; the loosening of the hair; the rhythmic motion of the body – a basic grammar of the technique of mourning handed down from time immemorial in the Mediterranean basin, as de Martino’s visual appendix to Morte e pianto rituale, the ‘Atlante figurato del pianto’ illustrates (Figure 11).

Figure 11 Funeral cortège from the tomb of Sancho Saiz de Carillo, now in the National Museum of Catalan Art in Barcelona

De Martino’s theory unwittingly highlights the deep affinity that the ancient ritual shares with modern photography as techniques of reproduction. The rite, sifted through a modern visual order, is decoded, yet in the process it unexpectedly raises the question of photography’s own ritualistic nature. What is the modern ritual performed by photography?Footnote 19

Death live

During the August 1956 expedition in Lucania, Pinna again shot many staged lamentations, but also, on his own initiative, photographed a live lamentation at Carolina Latronico’s funeral in Castelsaraceno. Together with the scenes of tarantismo in the church of Galatina in Salento photographed in 1959, this sequence is exemplary in ethnographic photography, catching the event ‘in atto’ (Figure 12–17).

Figures 12–17 Franco Pinna: The funeral of Carolina Latronico, Castelsaraceno, 1956

Direct and bold, these images stand out as a masterful expression of Pinna’s action-photography. At the same time, Pinna’s camera remains contained and humbled on the intimate and claustrophobic stage of sorrow, dissolving in the chorality and overwhelming emotion of the moment. Confronted with the absoluteness of death, the photographer disappears, as if absorbed into the urgency of this crisis of presence. Yet, at the same time, the camera unnaturally stills and silences the convulsive reality of mourning and, with an eerie mirroring effect, allies itself with the stillness at the centre of the photos, the face and body of the deceased Carolina Latronico (Figure 18). Diego Carpitella criticised Pinna’s photography for this ‘controtempo’, accusing it of being ‘out of sync’ with the event (1996, p. 141). But he failed to recognise that what he called ‘sfalsatura’ is the very ontological feature of the medium, one which contains the mechanism that defines the modern (i.e. photographic) construction of the live event as a death (145–146).

Figure 18 Franco Pinna: The deceased Carolina Latronico

It has long been acknowledged that photography plays a crucial role in the modern figuration (and erasure) of death. Roland Barthes noted the historical connection between photography and what Edgar Morin calls the ‘crisis of death’ beginning in the second half of the nineteenth century. ‘Death must be somewhere in a society . . . perhaps in this image which produced death while preserving life’ (Reference Barthes1980, 92). In modern society, photography would thus take the place of mourning rituals, as an ‘asymbolic death’ (92), a figuration of loss through displacement and erasure. Photography denies disappearance by disseminating and multiplying presence, but, as Barthes notes, is a weak monument; it has the impatience of all things modern (93). Being at the same time sunya and tathata (Barthes Reference Barthes1980, 5), void and reality, photography compresses within itself the two moments of the lamentation: the crisis of presence and the return to reality. As a witness to the passing (death) of the moment, photography dehistoricises the event in the metahistory of the image, and promises a re-entry into history. Instead of granting acceptance of the reality of loss, photography gives us a deceptive sense of control, the illusion of the endless retrievability of time, that life, if only in the shape of the image, will always be at our fingertips.Footnote 20 The temporal figure that photography evokes is not the monument but that anonymous, sprawling, finally indifferent figure, the archive – be it that of the iCloud or a more traditional library.Footnote 21

Around the bed of Carolina Latronico, different techniques of constructing death come together. Lamentation’s declared task is to separate the living from the dead and return the grieving subject to the living, thus achieving ‘forgetting’. Photography muddles the line between life and death, granting an iconic afterlife, an uncertain ‘remembrance’ without a working through. In Pinna’s images, mourning gives way to photography, immediacy to mediation, ritual to spectacle, as the unique event becomes infinitely retrievable, transportable, consumable outside of its context.Footnote 22 Yet, at the same time, the ancient practices open a reflection on the rituals of modern society and manage to reveal how anthropologists and photographers inhabit an unconscious constructed by the eye of the recording instrument.Footnote 23 Who mourns in Castelsaraceno? Consciously, the family of Carolina Latronico; unconsciously, the members of the expedition, who record the passing of peasant culture and their post-war ideals.

Going south

Susan Sontag observed how photography, appearing on the world scene at a time of historical acceleration, has been culturally invested with the elegiac task of recording the progress of modernity as loss and disappearance (Reference Sontag1977, 15–16). Photography closely shared with the contemporaneous new discipline of anthropology this mix of unrestrained expansionism and pious archiving. It was through photographic records of ‘primitive’ communities dispatched from the exotic peripheries to the western metropolis that the first anthropologists built their narratives.Footnote 24 The ethnographic discipline has been so closely entangled with photography that its history could be narrated in terms of the evolving understanding of the medium from mechanical producer of objective ‘documents’ in the nineteenth century to a self-reflexive site of interaction between observer and world observed in the late twentieth century. Perched on the unstable border separating the modern and the primitive, technology and magic, subject and object, photography afforded a material space where anthropology could consciously reflect on its practice. As Christopher Pinney notes: ‘Anthropology continues to define itself through – and against – the nature of photography’ (2011, 154), allowing the Western anthropologist to keep redefining the nature of his/her encounters, first with objectified (colonial) bodies, then the (complex) cultures that surrounded them, and eventually with his/her own self.

De Martino’s work participates in this radical shift that followed post-war decolonisation, and gave rise to a self-reflexive and visually informed anthropology.Footnote 25 His 1961 book La terra del rimorso opens with the recognition that the ethnographic journey, no matter how close to or far from home, has to do first of all with the anthropologist himself and his world; it is an act of consciousness that illuminates one’s own culture. To support his biographical and self-reflexive gesture, de Martino quotes at length from the nearly contemporary Claude Lévi-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques (Reference Lévi-Strauss1955):

What have we come here to do? What exactly is an ethnographic inquiry? . . . The ethnographer can hardly disinterest himself from his civilisation and refuse any responsibility for its faults, so much so that his very existence as ethnographer would be incomprehensible in any other way than as an attempt at redemption: the condition of the ethnographer is a symbol of expiation. (24)

De Martino adds no commentary, but the stark words of the French anthropologist introduce a discordant note in his discourse. The ethnographic encounter, for de Martino an object of dispassionate contemplation, is for Lévi-Strauss a site of cultural trial. Unabsorbed and unresolved, Lévi-Strauss’s words hint at a deeper and more troubling self-conscious involvement of de Martino in his ethnographic project of exploration of the mournful world of southern peasantry.

The South that Carlo Levi had exiled to a mythical world ‘beyond Eboli’, enters history with de Martino.Footnote 26 Notwithstanding this radical shift that brings north and south closer to one another, de Martino’s ethnographic journey is constructed along a clear fault line separating ‘the one who travels to know and the one who is visited to be known’ (de Martino 1994, 21). What divides the two worlds is not geography or an abstract temporality (historical modernity vs. atemporal primitiveness) but two alternate registers of history, as if the South were inhabiting an historical underbelly of the modern world. For de Martino, history is an accomplished act of consciousness safely circumscribed within the present of scientific enquiry (‘storia da comtemplare’), or of political action (‘passione attuale’), namely, the desire to emancipate the South overtly motivating the ethnographic journey. Against this world of light, stands a history steeped in shadows, the past – unresolved, haunting, mournful – granted to the southern peasants. Lévi-Strauss’ words question exactly this displacement of history’s irrationality, the past as guilt and loss, to a ‘primitive south’.

In Tristes Tropiques, the French anthropologist evokes ‘passions’ which bring him into close quarters with the people he studies. History is at one time the individual history of the ethnographer and a history encompassing centuries of western colonialism that he shares with the natives. By speaking of the condition of the ethnographer as a symbol of expiation, Lévi-Strauss places ‘remorse’ at the heart of the anthropological enterprise, a (Western) crisis of presence that he relentlessly explores in the intense confessional text of Tristes Tropiques. The ‘sadness of the tropics’ is the dwindling culture of the Amazon’s tribes, but it is first of all the ‘sadness of Europe’ (the violence of its colonial project, its pillage of resources, its flattening of the world’s diversity and specificity, its genocide of native peoples foreshadowing the event pressing at the edges of Strauss’s text, fascism and the Holocaust). Lévi-Strauss reminds de Martino that the land of remorse he located in the southern region of Salento is first of all a region of the ethnographer’s mind.

Coming to terms with fascism was the original impetus behind de Martino’s engagement with anthropology. His first book, Naturalismo e Storicismo nell’Etnologia (Reference de Martino1941), was conceived as a direct response to the dramatic historical present: ‘Our civilisation is in crisis: a world seems to be going to pieces, another is announced . . . modern civilisation needs all its energies to overcome the crisis that it is facing’ (12).Footnote 27 From this perspective, the study of primitive societies is seen as an urgent step toward understanding ‘certain modern dispositions of the soul’ (xi). Yet, having set out looking for the roots of modern irrationality, de Martino uncovers instead the birth of human subjectivity. His second book, Il mondo magico, written in the darkest days between 1944 and 1945 and published in 1948, reads magic and shamanism as the original struggle of subjectivity to emerge from nothingness. Yet after having established a compelling parallelism between the primitive and modern crises of subjectivity, and having thus radically challenged his teacher Benedetto Croce’s belief in the innate quality of rationality, de Martino’s theory stalls.Footnote 28 With a double, though unresolved movement of recognition and distancing, de Martino endows magic practices with the dignity of ‘a defined cultural drama’, but still a drama long overcome in human history. Leaving undeveloped and finally severing the connection between the modern and ancient crisis, between the present as a realm of historical rationality and the irrational past, de Martino disavows the irrationality and existential anguish unleashed by fascism. This theoretical and ethical roadblock is carried over into his post-war work, and pointedly raises Lévi-Strauss’ question: what has the ethnographer come to do on the scene of the primitive?

In his introduction to Il mondo magico, Cesare Cases magisterially explains the compensatory mechanism that underlies de Martino’s intellectual compromise: ‘What happens is a kind of transfer: the emotive charge impressed [by the experience of fascism and the war] is projected on the object; the lability and precariousness experienced in the present become the essential features of the magic world [. . .] This transfer works out in such a way that the magic world constitutes a “redemption of presence” for the western world’ (xxv). The momentous mirroring at work in La terra del rimorso between ethnography as ‘a symbol of expiation’ and the peasant practice of expiation known as tarantismo illustrates the persistence of this displacement. Post-war neo-meridionalism, the rush to chronicle and emancipate the South, of which de Martino’s project represents the highest and most complex expression, emerges as an unconscious journey for the modern ‘north’ in search of healing.Footnote 29 In the post-war, the South becomes an emblem as layered as the tarantula, in which mythical and political anguish, exorcising rituals and emancipatory practices confront each other. Having gone south to emancipate the living, de Martino and Pinna bring back a lesson on how to be emancipated from the dead.

Viareggio – what to do with the dead?

Upon its publication in 1957, Morte e pianto rituale became a literary sensation, and the following year it was granted the prestigious Viareggio Prize, usually reserved for works of fiction. In the words of a radio commentator, de Martino ‘gives space to an open discourse on death, although’, the journalist pointedly added, ‘on the death of others, those in the deep South’ (Gallini Reference Gallini2000, viii). In an Italy swept suddenly forward by tumultuous economic development, Morte e pianto rituale generated a cultural frisson, raising the apparently untimely question, articulated in the first pages of the book through the words of the philosopher Croce, ‘What should we do with the dead?’

In Frammenti di Etica (1922), Croce answered this question ruthlessly, invoking ‘the wisdom of life’: ‘Forget them!’ Rather than a process unfolding in time, forgetting is envisioned as a draconian act of will performed by a ‘healthy’ subject untarnished by any modern, psychoanalytic notion of the human mind as a field of unresolved forces. Long repressed and reviled in Italy through the joint efforts of Croce’s idealism, Fascism and the Catholic Church, psychoanalysis was, in a way, smuggled into Italy through the land of remorse. One of the projects of the short-lived Einaudi Collana viola, the ethnographic collection that de Martino curated with Cesare Pavese in the 1940s, was to be the publication of Freud (eventually aborted). But while engaging with psychoanalytic theory, even de Martino grew weary of fully exploring the connections between ‘primitive’ lamentation and Freud’s notion of Trauerarbeit. This remarkable resistance of Italian culture to psychoanalysis is intimately tied to a wide cultural failure to elaborate a modern ethos of memory. To stave off becoming a pathology, the act of forgetting requires a process, a representation, a social performance. As Nietzsche and, more recently, Marc Augé have noted, forgetfulness is essential to living and healing. But it imposes a price, a conscious expenditure, a working through, rituals that Augé calls ‘dispositifs destinés à penser et à gérer le temps’ (Reference Augé2001, 75). Without that, individuals and societies might think they are moving ahead when they are instead stuck in time, a time that they have forgotten how to forget.

So the question raised in Viareggio in 1958 was a crucial one for an Italian polity racing ahead of its pasts: What to do with the dead? ‘Industrial revolution against funeral lamenting’ read the title of one book review, as if the question had been superseded by modernisation itself, and death, like poverty, could be finally resolved and left behind. Short of a symbolic procedure that, like the lamentation, allows the construction of the dead and the living as separate yet related entities, what should a modern society do? What it has learned to do: namely, keep performing its own compensatory rituals organised around the modern photographic icon: taking pictures, making films. In fact, it is in a film, a global box office success, that, a year later, the urgent question of death and the return of the bad past wrapped in the seductive glitter of modern life finds an epochal representation. Fellini’s La dolce vita is the point of convergence of Pinna and Secchiaroli’s images which opened this essay. There, modern and primitive ritual meet, giving rise to a cogent representation of the crisis of presence at the heart of the new società del benessere. Footnote 30

Photography – the modern surface where glamour and mourning ambiguously coalesce – is at the heart of Fellini’s film.Footnote 31 Built around arresting images in the press, like the Aiché Nanà striptease, La dolce vita is a film thought and narrated through photographs, and like a photograph it is at once profound and superficial. Through a storytelling built on a series of unrelated episodes, where each displaces the previous like the progression of pictures in an album, the film invites a reflection on temporality and its relation to memory and ethics. The modern hero, Marcello Rubini, straddles a fine line between meaning and oblivion, moving through life, both like and with the paparazzi, vicariously, unconsciously, from event to event. A character who came to Rome in search of a brilliant career as a writer, with a vague past in the provinces, he is bereft of a clear narrative memory even within the story: loves, deaths, adventures fall from his consciousness like the pages of yesterday’s newspaper. Why does he give up writing? Why and what does he want to write in the first place? Why is he together with his girlfriend Emma and why does he leave her? (The same could be asked about Maddalena.) In the end, Marcello amounts to nothing because he remembers nothing, because nothing is worth remembering. As if sealing this amnesiac condition, in the final scene of the film, he does not recognise Paola, the blonde girl he met previously at the beach restaurant, the one who looked like ‘an Umbrian angel’. While she mimics, against the roar of the ocean, who she is and where they met, Marcello gestures his incomprehension, not simply because he cannot hear. He cannot remember.

Although permeated by unrelenting bitterness, with almost each of its episodes closing on an actual or threatened death, the film is commonly remembered as an icon of the easy, glamorous life. If we consider how Fellini himself placed the meaning of the film in Steiner’s killing of his children and suicide, the history of the reception of La dolce vita becomes itself an exemplary case of repression and forgetting. The refusal to confront loss hinders a critical engagement with the past; mourning, in the words of critic Alessia Ricciardi, ‘instead of being understood as an ethical question . . . comes to be rephrased as an aesthetic device or posture (not a process of careful self-interrogation, but a kitschy display of nostalgia)’ (2003, 4).

From the terrace of Steiner’s apartment, a distraught Marcello looks at the dead body of his friend Steiner. What is he thinking? (Figure 19) What should he do with these dead? Films can hardly represent thoughts, but they give us close-ups, landscapes, dialogues and music. Behind a speechless Marcello looms not the actual landscape outside of Steiner’s apartment, but a reproduction – a photograph or even a drawing – of one of the most iconic landscapes of modern Italy: the EUR neighbourhood in Rome. Planned by Mussolini for the 1942 universal exposition, the EUR was completed only in the 1960s. A signature image of modernity in many films of the 1960s, this backdrop, on which past, present and future merge, is emblematic of Italy’s confusion about historical temporality. It is not by chance that Marcello’s most dramatic crisis is framed by the amnesiac modernity of the EUR. The EUR is the re-bite of the bad past – modernity as the land of remorse. Or at least this is what it should be. ‘I love the EUR because it is without history, the oldest monument being a 1965 gas pump’, Fellini explains in a 1972 documentary, Fellini e . . . l’EUR, in a TV series in which various artists reveal an important source of their inspiration. It speaks of the future, Fellini continues, ‘but a future we already know, therefore comforting’. Feeling provisional like a stage set where history has turned into a disposable prop, the EUR ‘stimulates’, quoting Fellini once again, ‘a feeling of freedom, of an alibi . . . of a temporary, cinematic life invented day by day’. The boundless amnesiac cinematic present which in La dolce vita amounts to a secular hell, has been transformed for Fellini by 1972 into a dream and desire, an existential aspiration, the very figure and condition of creativity, one which stands in for the work of memory. As Andrea Minuz has recently noted, Fellini here expresses a profound national ethos, namely, I would argue, a uniquely Italian carelessness about history, one which still persists, finding its latest dispiriting avatar in Paolo Sorrentino’s Jep Gambardella (La grande bellezza, 2013). In this film, la dolce vita proves to be Italy’s ongoing fixation, a modern pharmakon (both cure and poison) to a longstanding ‘crisis of presence’, a failed confrontation with historical loss.

Figure 19 Fellini, La dolce vita

And so, Marcello Rubini, bereft of a future or past, stands as an exemplary Italian subject. Italy’s national identity, or the often bemoaned lack of one, could be seen as the persistently absent cultural elaboration of the past leading to a confused sense of any collective project. The question raised in 1958 of what to do with the dead remains to be addressed. Modern icons acting as national memory aids prevent the working through of what is unresolved, controversial, divided, impure, and thus impede the construction of what Nietzsche calls a critical history, a history metabolised through a process of memory and forgetting.

End: rituals to hide and rituals to heal

Pinna and Secchiaroli’s photographs stage a jump from a modern to a primitive setting, disavowing the history in between. Their uncanny mirroring, however, forces open their iconic closure, inviting a reflection on memory and modernity and, specifically, Italy’s penchant for forgetting. One image speaks of fun, the other of pain. That of fun – as Fellini reveals in his restaging of the striptease in the final party scene of La dolce vita – is redolent with pain, while that of pain speaks of healing. One image is a promise of erotic freedom and unbounded prosperity: the other, a stark reminder of poverty and the constraints of traditional society; yet the two performances share similarities as well. Like the liberating taranta dance, the striptease is a highly codified ritual, though one of unclear liberating potential. The body of a woman is central to both performances, a privileged theatre of emotions (Gallini Reference Gallini2000, xxviii), working in both cases as a ‘medium’ which conveys different individual and collective upheavals. The body of Maria di Nardò is the stage of a crisis, and the symbolic performance is a turning point of the disease. The body of Aiché Nanà is not in crisis. Yet, her performance, rendered iconic though photography, is perceived as a ‘historical’ turning point, marking the beginning of another era, away from the land of remorse towards the land of benessere, an ‘electrifying’ crisis that also carries uncertainties and anxieties, which the ‘medium’ – both the body of the woman and the photographic apparatus – translates into a soothingly sensual language. In both rituals, the woman’s body speaks of larger collective tensions, at once primitive and modern, between slavery and emancipation (economic, cultural and sexual), spectacle and cure, oblivion and self-understanding.

Read against the primitive ritual, the automatism and unquestioned nature of the modern performance is exposed, upsetting our expectations about agency. Maria di Nardò is a subject who, while unconscious of the ‘true’ nature of her illness, is consciously struggling to regain her health, her body the medium of her cure. Aiché Nanà is just a body (one of an underage, intoxicated, and orientalised foreigner), only a medium for the onlookers’ ‘cure’. In a surprising reversal, the ancient ritual reveals itself as a conscious moment of healing, one that gives symbolic form to the hold that the bad past has on us; the modern ritual is unconscious of its reasons.

To what does the striptease give a symbolic form? La dolce vita’s fictional re-enactment offers an answer. As a final attempt to revive a flagging party, Marcello, now a fully-fledged hack writer for scandal magazines, proposes a striptease. The newly divorced Nadia (the Rumanian actress Nadia Gray, born Nadia Kujnir) volunteers to do it as a way to celebrate the voiding of her marriage and the ‘baptism’ of a new life. It is a gesture of rebellion and flaunted emancipation, a literal shedding of the past. Yet Nadia’s performance is a flop, painful both for performer and spectators (Figure 22). As one onlooker tells her, the striptease requires a precise tempo, a coolness that uses the body as a tool, a machine; it is a ritualised grammar of gestures: ‘you made a mistake . . . the bra is the one before last’. Mechanically reproduced, repeatable, easily consumable, the striptease mimics tarantismo to create a love-making without a soul. It is all form, no content: it dehistoricises the present, dispelling all concerns with past or future. The striptease repeats the tarantismo setting (the circle of spectators, the music, the waving of garments), but does not deliver one from the past, only from garments. The outcome is not a body at rest, but simply a naked/shamed body. Not unlike photography, the striptease works according to a logic of exposure, the progressive shedding of veils, yet the meaning of its disclosures, as well as the nature of its ‘memory’, remains suspended. If present, the release, erotic, physiological not historical, is only for the spectators. You see everything and understand nothing.Footnote 32

Figure 20 Tazio Secchiaroli © Tazio Secchiaroli/David Secchiaroli and Figure 21: Franco Pinna

Figure 22 From Fellini, La dolce vita and Figure 23: Gustave Doré: Detail from the illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy, Arachne, (Purg. XII, 43, 44)

After the striptease, La dolce vita ends on the beach in the first washed-out light of the morning. As the partygoers stream out of the pinewoods, they happen upon a big shapeless creature stranded on the shore whose main feature is a huge vitreous eye, which fascinates Marcello because ‘it keeps looking on’. In a society punctuated by the indifferent flashes of cameras, this persistent look is the closest thing to the re-bite of the tarantula; a still eye that stands in judgment. In the chaotic and ungainly sea monster, photography and the unprocessed past find a compelling alignment. The unreconciled past is shapeless, it defies visual co-optation and manages instead to keep staring back. The stripper/tarantula, on the other hand, graphically merged in Gustave Doré’s monster (Figure 23), embodies the ‘bite’ of the bad past and erotically disavows its existence. If de Martino’s ethnographic journeys to the South raised the question of what to do with the dead, the answer from the Italy of the miracolo economico was evasive . . . and effective. The sinful night at the Rugantino propelled Italy into modernity by riding on the euphoric wave of la dolce vita, paradoxically easing the traumas of both the past and the future with a promise of forgetting. After all, that very Italian adjective ‘dolce’ has been joined, at least since Leopardi, with oblivion. What actually may have started circa 1958 in Italy is a new age of forgetting, one in which the modern rituals of photography and cinema are, with their ‘fugitive testimony’ (Barthes Reference Barthes1980, 93), tenuously holding our sense of time together.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Giuseppe Pinna and Claudio Domini from the Archivio Franco Pinna and Carmela Biscaglia from the Centro di documentazione Rocco Scotellaro for their generous support, and Giovanna Bertelli at the Achivio Secchiaroli for permission to use their materials.

Notes on contributor

Giuliana Minghelli is an Associate Professor of Italian and Film Studies at McGill University. Her research focuses on questions of history, ethics and memory at the intersection of literature, cinema and visual culture. She is the author of In the Shadow of the Mammoth: Italo Svevo and the Emergence of Modernism (University of Toronto, 2003) and Cinema Year Zero: Landscape and Memory in Post-Fascist Italian Film (Routledge, 2013). She edited The Modern Image: Intersections of Photography, Literature and Cinema in Italian Culture (2009) and co-edited with Sally Hill, Stillness in Motion: Italy, Photography and the Meanings of Modernity (Toronto UP, 2015). She is currently working on a research project on shame in post-war culture.