INTRODUCTION

A Forme of prayers bound with one of only two extant copies of the 1557 Anglo-Genevan prose psalter proposes a method of psalm reading more contentious than might at first appear. “Heare,” dictates a rubric just after the Creed, “may be redde Psalmes agreable to the state and condition wherein we do feele our selves, as may be learned by their arguments.”Footnote 1 This directive shows that the adjoining psalter—the first English prose version with a textual apparatus updated to the standards of Continental scholarship—facilitates reading of a particular kind: its “arguments,” the printed headnotes summarizing each psalm, allow the reader to select the psalm appropriate for the occasion at hand. As instruction for prayer, occasional psalm reading departs sharply from the monthly reading of all 150 psalms in sequence prescribed by the Edward VI Prayer Book (1552), better known as the Book of Common Prayer. This 1557 Forme of prayers precedes the first in a series of psalm printings culminating in the Book of Psalms found in the pages of the 1560 Geneva Bible, the Elizabethan age's most popular. The Book of Common Prayer would become official state liturgy under Queen Elizabeth (r. 1558–1603). Their contrast announces a friction between material and method at the heart of Elizabethan psalm reading.

With few exceptions, scholarship on Elizabethan psalm culture as a popular phenomenon concentrates on the singing psalter, The whole booke of Psalmes (1562), often called Sternhold and Hopkins.Footnote 2 Due to its ubiquity during the period, this psalter is hard to avoid. Beth Quitslund describes the singing psalter as appealing to “nearly all of the English church.”Footnote 3 Alec Ryrie characterizes its aggressive universality: “It crossed the space between private and liturgical use, and it could drown out any ministerial protest.”Footnote 4 Noting its completion in exile and subsequent church acceptance, Ruth Ahnert finds in Sternhold and Hopkins a synthesis of the impulses to reform “from below” and “from above” that divided earlier Tudor psalmody.Footnote 5 Focus on the singing psalter presents the psalms as a force of cultural unity in Elizabethan devotional life, that rare point of accord in an age of doctrinal conflict.

Yet prose psalters exerted an influence just as profound, albeit far more divisive. The few studies attending to the period's prose psalms distinguish between stand-alone psalters and the Books of Psalms printed in bibles.Footnote 6 There is good reason, however, to include both in the category of prose psalters, since stand-alone and bible-bound printings often correspond in translation and paratext and were often, as the present study shows, used interchangeably.Footnote 7 Prose psalters (thus conceived) appeared in almost twice as many editions as Sternhold and Hopkins during the first three decades of Elizabeth's reign.Footnote 8 They contained the psalms Elizabethan Protestants read in church, where unlike the singing of metrical psalms, their plainsong or spoken recitation was a mandatory part of the service.Footnote 9 Protestants also used these psalms in their homes, often in private imitation of public liturgy.Footnote 10 Prose psalters would have been as integral to daily devotion as the singing psalter and even more closely connected to church ritual.

But if Sternhold and Hopkins achieved dominance across sectarian lines, prose psalters often helped draw them. Whether bible-bound or stand-alone, distinct versions of the prose psalter competed for dominance on the early Elizabethan book market. As Aaron Pratt demonstrates for bibles, it was often paratext, rather than translation, that distinguished these versions.Footnote 11 The paratexts of distinct prose psalters dictate reading methods at odds with one another, opposed ways of working through the collection of short biblical poems the psalters contain. These methods positioned their psalters within the defining ecclesiastical conflict of the period: the nascent rift between the Church of England and nonconformist Protestants, or Puritans, as they came to be called. Recent historiography views early modern Protestantism as a “broad-based religious culture,” at least “when examined through the lens of devotion and lived experience.”Footnote 12 Printed prose psalters, however, provide material evidence of competing convictions on a topic of great significance for Elizabethan daily life: how the psalms should be read.

Extant Elizabethan prose psalters in libraries and archives have something more to say on this topic. A significant percentage bear handwritten annotations, a form of material evidence seldom found in copies of Sternhold and Hopkins.Footnote 13 Print, taken by itself, documents prescription rather than reader practice, issuing a mandate “from above,” to adapt Ahnert's terms. The markings of Elizabethan readers show what these readers felt they needed to add to their printed prose psalters to suit their own devotional purposes: a contribution “from below.” Reader markings demonstrate both what readers did with the psalm reading methods prescribed by their psalters and, even more importantly, what they did without them, the traditions and insights they introduced to the page.Footnote 14 The marked pages of prose psalters thus disclose a negotiation between above and below, prescription and practice. Study of these pages allows reconstruction of not only how the psalms should be read but, to the extent possible, how they were read.

They were not read as intended. The claim of this article is that two distinct methods of psalm reading shaped the prose psalters that circulated in Elizabethan England, but that the independence of readers—observable in their markings—reshaped them. At its most physical, the distinction in methods is between continuous and discontinuous reading.Footnote 15 The Book of Common Prayer requires the reader to work through the psalter sequentially once per month, reading the psalms dictated by the Prayer Book's calendar each morning and evening. The goal is comprehensive coverage according to a method uniform across the spiritual community. In contrast, Anglo-Genevan scholarship advocates inhabiting the emotional and spiritual posture of the psalmist. The reader is to select now from one portion of the text, now from another, in order to apply the appropriate psalm to the appropriate situation in the reader's life.Footnote 16 The goal is an understanding charged with feeling. Calendrical and occasional reading, as I call these two methods, were not wholly incompatible—though supporters of the latter sometimes inveighed bitterly against the former—but early in the period they functioned as distinct ideals and were distinctly productive.

Attending to the use Elizabethan readers made of their prose psalters shows the continual fine-tuning characteristic of Elizabethan Protestantism. Early on, printers developed paratexts and supplementary material directing readers to one method or the other. Paratexts could either guide readers through the Prayer Book schedule by assigning the psalms dates and times, or facilitate the matching of psalm to occasion through arguments and topical headings. Reader markings, however, confirm Kate Narveson's insight that attempted regulation of bible reading often provoked readings more “varied and active” than intended.Footnote 17 Readers no more acceded to the program of use printed in their prose psalters than they did to the prescriptions of the established church. They mingled the cultural ideals of calendrical and occasional reading through modification of text and apparatus. These readings, in turn, shaped printing practice. Printers eventually mingled the distinct styles of paratextual direction, achieving more broadly appealing, and hence more profitable, psalters. For printers and readers alike, then, the distinction between calendrical and occasional reading provided the framework for a thriving culture of psalm reading, but one subject to the same conflicts and compromises as the national church.

HISTORICAL ORIGINS OF THE COMPETING PROSE PSALTERS

The debate over psalm reading methods originated in the historical episode also responsible for the founding of the Anglo-Scots community in Geneva: the so-called Troubles at Frankfurt. The story is familiar. At Frankfurt in late 1554, one group of Marian exiles—the English Protestants who weathered the reign of the Catholic Mary Tudor (r. 1553–58) on the Continent—fell into increasing conflict with another over objections to ceremony in the Book of Common Prayer. As a result, the objecting party, led by John Knox (ca. 1514–72) and William Whittingham (d. 1579), resettled in the Geneva of John Calvin (1509–64), where they went on to produce the scholarship that would incorporate Calvinist thought into Elizabethan Protestantism: a liturgy, a complete metrical psalter, numerous English translations of Calvinist doctrine, a series of anti-Marian political pamphlets, and—their labor of the longest shadow—the Geneva Bible.Footnote 18 Historians have traditionally viewed the Troubles as the first salvo between conformists and Puritans, an origin myth Elizabethan Puritans cultivated themselves in a 1574 pamphlet entitled A Brieff discours off the troubles begonne at Franckford.Footnote 19 Although this document arguably creates a spurious sense of historical continuity, it remains an indispensable source for the events of 1554 and 1555.Footnote 20 Most important for present purposes, A Brieff discours details the objections Knoxians, as they are called, took to the Prayer Book.

One important objection was to the practice of calendrical reading. The pamphlet reproduces a letter describing the Prayer Book liturgy that the Knoxians sent Calvin for his appraisal in late 1554.Footnote 21 The description highlights the Prayer Book's deviations from the practices Calvin had prescribed for Geneva, those to which budding reformers on the international stage generally aspired. Many items are thinly veiled grievances, among them the reading of scripture “suche as the callender apointethe for that daie . . . For all holy daies are nowe in like use as were amonge the Papistes / onelye verye fewe excepted.”Footnote 22 Calvin eschewed lectionaries as a remnant of the Catholic liturgical year, instead using the lectio continua method, whereby he preached through a whole book of the bible, one short passage at a time, with (for the most part) no correspondence to annual cycle.Footnote 23 He could thus have been expected to sympathize with the English exiles’ strongly worded conflation of the Prayer Book lectionary with the Catholic liturgical calendar it was meant to replace.Footnote 24 In this respect, the exiles aspired to Calvin's own practice.

The letter launches a more muted attack on the Prayer Book's method of psalm reading. After the opening of morning prayer, the letter explains, “By and by also there folowe 3. Psalmes together at thende off every one.”Footnote 25 This detail forms part of the letter's condemnation of lengthy scripture readings during service—of “whole chapter” lessons—which the Knoxians regarded as an “irksome and unprofitable form.”Footnote 26 Calvinist bible preaching was on short passages, and although the psalms sung in Calvinist churches evolved from one to three per service, they were never sung continuously (“together at thende off every one”) and often sung only half a psalm at a time.Footnote 27 Brevity of text allowed for a singing in which, as Calvin put it, the “heart and affection . . . follow after the intelligence”: a singing with understanding.Footnote 28 Sharing Calvin's ideal for psalm singing, the Knoxians invented the sum of three psalms, an approximation for the up to six dictated by the Prayer Book, to show that the readings prescribed by the calendar were too lengthy to achieve the understanding sought. Calvin's approving, if general response to the letter (also printed in A Brieff discours) would have affirmed the Knoxians in their objections, or at least would have seemed to do so, although their approach to the lectionary differed markedly from Calvin's (a point to which I will return).Footnote 29 When in 1556 the Anglo-Scots community in Geneva began to produce their own liturgies and psalters, they omitted the lectionary not only for the Old and New Testaments but also for the psalter.

THE TRANSLATION USED IN COMMON PRAYER

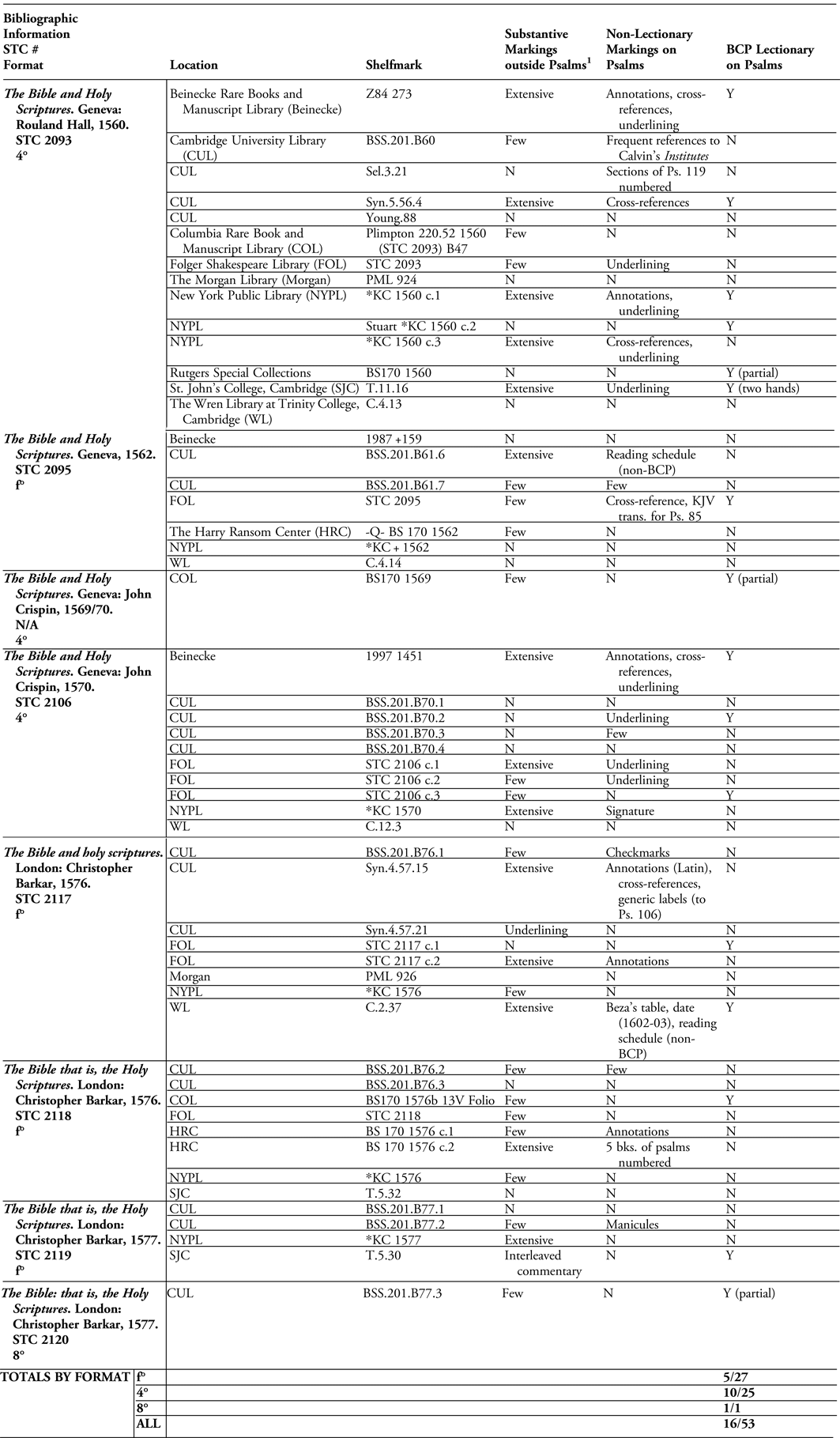

Thomas Cranmer (1489–1556) had established the rota, or monthly schedule, for psalm reading in the 1549 first version of the Book of Common Prayer, and this schedule remained essentially unchanged in the 1552 version that formed the subject of the Frankfurt controversy, and later in the 1559 version issued upon the ascension of Elizabeth and in use throughout her reign.Footnote 30 All these versions include Cranmer's preface, which leverages the practice of psalm reading to justify a revised liturgy. “Now of late tyme,” the preface complains, “a fewe of [the psalms] have been dailye sayed (and ofte repeated) and the rest utterly omitted.”Footnote 31 Pre-Reformation English clergy had, in fact, worked through the psalter on a weekly basis.Footnote 32 Nonetheless, Cranmer positions reading of the entire psalter, rather than, for instance, only the penitential psalms, as a revival of the lost practice of the early church. The Prayer Book corrects unequal scriptural valuation throughout the bible by means of its “Kalendar,” which, as the preface announces, calls for continuous reading of the whole scripture “without breakyng one piece therof from another.”Footnote 33 Psalm reading is of special importance, warranting a separate “order howe the Psalter is appoynted to be readde” and a “Table for the ordre of the Psalmes to be sayd at Morninge and Eveninge prayer,” which apportions readings of one to six consecutive psalms to morning and evening for each of the thirty days of the month (with some stipulations for shorter or longer months and for the very long Psalm 119) (fig. 1).Footnote 34 The Kalendar—labeled “Almanack” in the 1552 version but present in 1549 as well—then articulates these psalm readings onto a detailed yearly schedule of one month per page, where they are joined by readings from other portions of the bible. The result is a comprehensive lectionary by which most parts of the Old Testament and Apocrypha are read through once per year; the New Testament (excepting Revelation) three times per year; and the psalter once each month.Footnote 35

Figure 1. The Order and Table from The booke of the common prayer, 1549. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Mzj 145 +A4 1549D, sigs. Aiiiv–Aiiiir.

From the Prayer Book's inception, corresponding stand-alone prose psalters appeared whose paratexts facilitate the calendrical reading prescribed by the lectionary. During the sixteenth century, these psalters were sometimes bound with Books of Common Prayer, sometimes separately; in the latter case, they were often accompanied by an abridgement of the Prayer Book or simply a Table and Kalendar. Their psalms are those of the Great Bible, the first royally authorized version, from which extracts of scripture printed in sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Books of Common Prayer universally derived. Miles Coverdale (1488–1569) completed the Great Bible translation in 1539, and it included one of four versions of the psalms he produced in the space of six years.Footnote 36 The Great Bible psalms were largely an update of those found in Coverdale's 1535 bible, the first complete bible in English. For that version, Coverdale, who was not proficient in Hebrew, based the psalms on the Vulgate and several more recent German and Latin translations. In updating them for the Great Bible, Coverdale then incorporated corrections from a new Latin translation by Sebastian Münster (1488–1552).Footnote 37 There was no legal injunction for exclusive use of the Great Bible psalms with the Prayer Book, giving rise to scholarly speculation that metrical psalms may have sometimes been substituted.Footnote 38 Yet the appearance of common prayer psalters that printed the Great Bible psalms lent them de facto official status. A highly idiosyncratic version, extracted at an arbitrary moment in the proliferation of psalm translations, endured because of association with state liturgy, with some help from Coverdale's eloquence.

Common prayer psalters quickly developed conventions of page layout. Like in the Great Bible, the psalms stand beneath their numbers and incipits (their Latin first lines from the Vulgate), and the text appears in black letter. Unlike in the Great Bible, the psalter is “poyneted as it shalbe sayde or songe in churches,” meaning verses are set apart from one another and each is divided by a colon to indicate where a singer would change notes.Footnote 39 Following a 1549 edition printed by Richard Grafton (1506/07–1573)—who, along with his former partner Edward Whitchurch (d. 1562), was responsible for the printing of all Prayer Books in Edwardian London—common prayer psalters frequently include directions that dictate calendrical reading as explicitly as possible.Footnote 40 While the Great Bible printed psalm-number page headings and marginal cross-references, the headings now featured the day of the month on which that page's psalms were to be read and the margins dictated “Mattins” and “Evensong” in Grafton's 1549 edition, “Morning prayer” and “Evening prayer” in 1552 and thereafter, to denote where the reader should begin (fig. 2). These paratexts evince a single-minded intent to guide the reader through the rota.

Figure 2. The psalter or psalmes of David, 1549, with “Mattins” updated to “morninge prayer.” Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Vp1 2, sig. Aiir.

The Prayer Book lectionary and corresponding common prayer psalter proved remarkably stable, even perversely so.Footnote 41 The Table and Kalendar remained essentially unchanged throughout the Elizabethan period and endured even into the 1662 revision of the Prayer Book, issued after the Restoration. During a period in which vernacular biblical scholarship advanced rapidly, the text of the common prayer psalter stood still, altered only by the addition of verse numbers, frequent by the end of Elizabeth's reign.Footnote 42 While the 1662 Prayer Book incorporated the text of the King James Bible into the rest of its services, its psalms remained those of the Great Bible.Footnote 43 If it was an arbitrary process that led sixteenth-century congregants to open the fourth day's morning prayer by declaring “the law of the Lord” “an undefiled law,” rather than a “perfect law,” as Coverdale's bible of 1535 and almost every English translation besides the Great Bible's would have it, congregants into the mid-twentieth century did the same.Footnote 44 The Church of England's lectionary aimed to bring reading practices into step and inscribe them with church authority. To this end, a well-defined method and a standardized text were crucial.

THE TRANSLATION ACCORDING TO THE HEBREW

By omitting the psalm lectionary from the liturgy that they published in February 1556, the Genevan exiles established a position on psalm use unique not only in the English context but in the Protestant. The 1556 Forme of prayers and ministration of the Sacraments incorporates the practice of psalm singing, well established on the Continent, into an English service (though this practice had not actually been a point of contention at Frankfurt).Footnote 45 In doing so, the exiles claim to take for model the “best reformed churches,” presumably French Calvinist churches, which had embraced the singing psalter of Clément Marot (1496–1544) since the 1540s.Footnote 46 The 1556 service includes two instances when psalms are to be sung, before and after the sermon. One and Fiftie Psalmes of David in Englishe metre—a modified reprint of thirty-seven metrical psalms by Thomas Sternhold (1500–49) with additional versifications by John Hopkins (1520/21–1570), Whittingham, and perhaps others—appears at the end of the volume to facilitate this usage. Method of psalm selection, however, remains unspecified, presumably at the discretion of the minister. This procedure departs from the Book of Common Prayer, which refers to its Table for the selection of psalms to be used at morning and evening prayer. Remarkably, it also departs from the method followed by Calvin. While Calvin eschewed lectionaries for preaching, a “Table for finding the psalms according to the order in which they are sung in the Church of Geneva” had been authorized for use with the French singing psalter since 1546, and updated continually until 1562, when the psalter was completed.Footnote 47 This psalm lectionary differs greatly from that of the English Prayer Book. In its final form, the French Table projects the whole psalter onto a calendar of twenty-five weeks, uncoordinated with the liturgical year; it only prescribes psalms for Wednesday and Sunday services, rather than daily; and the ordering is not only biblical but also thematic. It is a psalm lectionary, nonetheless. In discarding the lectionary for Old and New Testament readings, the Genevan exiles followed Calvin's practice. In discarding the psalm lectionary, they struck out on their own. Indeed, their purely occasional approach to the psalter was closer to the anti-lectionary tendencies of the Radical Reformation than to Calvin's procedure.Footnote 48 Unlike much introduced into English Protestantism by the Genevan exiles, occasional psalm reading was English from the start, a consequence of intra-Anglo-Protestant quarrelling on the Continent, rather than a true Continental import.

The exiles also intended the prose psalter for this unique method of reading. Just as the singing psalter formed an inextricable component of the public service, the prose psalter was integral to the exile community's vision of private worship. In 1557, a year after the first edition of The forme of prayers, the exiles published a prose psalter in a pocket-sized sextodecimo volume. This edition was, with the 1557 Geneva New Testament, the first printing of scripture in English to incorporate the advanced paratexts and systems of reference already flourishing in French printing.Footnote 49 Yet because a badly damaged copy in the Bodleian Library (once thought unique) is the more accessible of only two extant, another housed at Cambridge—referenced at the start of this article—has garnered little attention.Footnote 50 The Cambridge copy (unlike the Bodleian's) includes a preceding Forme of prayers, the sole surviving printing of this version. The 1557 Forme of prayers reproduces the 1556 edition but abbreviates and modifies it for private use: it includes the confession and several prayers but omits explicitly public duties, like baptism, marriage, and visitation of the sick. The modification of the rubric calling for psalm singing offers insight into the role intended for the psalms in private worship. The 1556 Forme of prayers contains a rubric reading, “Then the people singe a Psalme, which ended, the minister pronounceth one of these blessinges, and so the congregation departeth.”Footnote 51 In the equivalent place, the 1557 version has “Heare may be redde Psalmes agreable to the state and condition wherein we do feele our selves, as may be learned by their arguments,” followed by the same blessings, with the possibility left open for others “by thy discretion.”Footnote 52 The swapping in of “Heare may be redde” for “Then the people singe” demonstrates that in private worship, the prose psalter ought to assume the role of One and Fiftie Psalmes, private reading taking the place of public singing. Rather than the minister choosing the psalm appropriate for the congregation, individual conscience—how the reader “feels”—dictates the psalm appropriate for the congregant. For the Genevan exiles, there is no categorical distinction between public liturgy and private prayer.Footnote 53 Psalm use in accordance with occasion should be pursued in both.

The text of the 1557 prose psalter strives to facilitate this type of reading. Despite the full title of the edition, The psalmes of David translated accordyng to the veritie and truth of th'Ebrue, wyth annotacions moste profitable, the psalms included are, with some minor corrections, those of the Great Bible; they are, therefore, by no means translated from the Hebrew.Footnote 54 The real distinction from the common prayer psalter rests not with translation but with apparatus, much of which was imported from One and Fiftie Psalmes. Summaries based on Calvin's psalm commentaries stand at the head of each psalm as the “arguments” intended to aid reader selection. Cross-references and “annotacions moste profitable” flank the text on all sides. After the practice of the singing psalter, and along with the New Testament of the same year, the 1557 Geneva prose psalter became one of the first presentations of scripture in English to offer verse numbers, a system of reference popularized by the French Calvinist Robert Estienne (1503–59) in the early 1550s.Footnote 55 Each element of the apparatus fits into the occasional method. The reader can use the arguments to locate particular psalms appropriate for particular occasions, appreciating the larger psalter as a kind of emotional index. The annotations allow for richer understanding of the psalm thus appropriated and so of one's own spiritual position. The cross-references situate the psalms within the greater web of scripture, while the verse numbers facilitate memorization and navigation verse to verse. If the translation is nearly the same as that of the common prayer psalter, the use implied by its paratext trades uniformity and comprehensiveness for appropriation and understanding.

In the exiles’ second prose psalter of 1559, competition with the common prayer psalter becomes explicit. The 1559 Boke of Psalmes is, like its predecessor, a tiny sextodecimo volume intended for private use. It retains nearly all the paratextual features of the 1557 prose psalter, with a few additions, but its text is retranslated directly from the Hebrew and almost identical to that which made its way into the full 1560 Geneva Bible. In addition, although this psalter no longer includes a version of The forme of prayers, new supplementary sections point out the intended manner of reading. The work opens with an epistle to Queen Elizabeth, then newly crowned, challenging her to take up the volume as the household psalter of her Protestant regime. The psalms, declares the epistle, must be “wel weighed & practised. For here shal you se painted as in a most lyvely table, in the persone of King David, suche things as you have felt and shal continually fele in your selfe.”Footnote 56 To “weigh” and “practise” the psalms, in this account, is to see in them one's own emotional state. The preface to Calvin's psalm commentaries famously calls the Book of Psalms a “mirror” of all human emotion.Footnote 57 The writer of the 1559 epistle transforms Calvin's mirror into a “table,” phrasing suggestive of a painterly tableau, certainly, but also of the Table of psalm readings in the Book of Common Prayer. Read the psalms, this writer seems to say, not with tables of stone, the tables of calendrical prescription, but with the fleshly, or rather lively, tables of the heart. Inhabit them with your emotions and let their history describe your own. The common prayer Table continues to serve as a point of comparison for the first of two tables printed at the text's end. This alphabetical index of first lines appears under the title “A Table for the Ordre of the Psalms,” surely meant to recall the identically titled Table presenting the lectionary in the 1552 Book of Common Prayer. Moreover, the 1559 Table is an updated version of the finding aid sometimes included at the end of common prayer psalters, a “Table contaynyge the names of the Psalmes after the order of the Alphabet,” though the 1559 Table lists the psalms by their English first lines rather than Latin incipits. By assigning the title of the Prayer Book's psalm lectionary to the alphabetical finding aid, the 1559 prose psalter implies that the correct order to be followed in use of its psalms is the one that helps match the reader's memory of a psalm—presumably associated with vernacular rather than Latin content—to the correct occasion. A “Second Table concerning the chief points of our religion” then allows the reader to locate appropriate thematic material—under headings like “Prayers against the wicked” or “Of the feare of God”—by psalm and verse numbers.Footnote 58 Epistle and Tables issue an invitation to appropriation in accordance with emotional understanding.

The psalter's compilers state bluntly that such a reading method opposes that prescribed by the Book of Common Prayer. A “To the Reader,” included (strangely enough) at the volume's close, objects to calendrical reading with startling clarity:

But because many ether of ignorance or custome thinke that the exercise of the Psalmes standeth in oft repeating them over, & also by saying daily a certeyne nombre, bynding them selve to saye verse for verse, til their taxe be ended, we thoght briefely to admonish wherein the true use consisteth. . . . For when we fele our selves in danger ether of outward or inward enemies, by Davids example we learne to flee unto God, examine our cause, bewayle our synnes, confesse our misery, declare our faith, cast out our complaintes before him, be earnest in prayer, and paciently to abyde til he send us deliverance, & not unadvisedly to read whatsoever Psalme commeth first to hand, or that which is appointed for this day or that day, but diligently to marke what maketh to the pourpose & present necessitie. For except we understand that, which we speake, we can not pray in faith, and that which we fele not in our selves, and to the which our hearts consent not, is done without understanding, and so is not available.Footnote 59

The Genevan exiles wage their longstanding rhetorical battle against ceremony on the field of the psalter. They oppose the “ignorance or custome” supposedly implicit in common prayer psalm reading to the “true use” consisting in emotional understanding. To read at random and to read according to the calendar are one and the same. The exiles instead champion a circular process whereby “feeling” and “understanding” mutually reinforce. Used aright, this hard-to-navigate collection of biblical poems grants direct understanding of one's own deeply felt position.Footnote 60 But in order to match feeling to psalm, one must first understand. Thus, rather than uniform sequential reading, the exiles prescribe profound knowledge of the psalter. The extensive apparatus of their text—whose material workings the “To the Reader” goes on to describe in the passages immediately following the above—aims at cultivating a reader whose feelings are everywhere woven into the fabric of scripture. This emotional understanding is the goal of occasional reading, just as comprehensive coverage in accordance with church authority is the goal of calendrical.Footnote 61

Though in many respects the culmination of these earlier psalters, the Book of Psalms as it appears in the full 1560 Geneva Bible suggests occasional reading without staking out an explicit position against calendrical. This text retains all paratextual elements of the 1559 prose psalter and adds to them topical page headings and a large introductory argument, both borrowings from French biblical scholarship.Footnote 62 The yet more thorough cross-references in the margins send the reader to other passages, encouraging discontinuous reading across the whole network of scriptural texts.Footnote 63 The densely packed interpretive annotations bring this reading into its practitioner's own life by offering what Thomas Fulton calls an “applied literalism,” an open invitation to read biblical truth into the present moment.Footnote 64 The numbered verses, which the Geneva Bible's “To the Reader” declares “moste profitable for memorie,” allow the reader to sort the insights of the biblical text and find them again when necessary.Footnote 65 In addition, the reader can now page through by page-heading topic, a further aid in the location of the psalm appropriate to the situation. The long argument preceding the Book of Psalms, original to the 1560 Geneva Bible and reproduced with all subsequent editions, adapts the 1559 prefatory material, addressed to a royal audience, for a popular one. The Psalms, it claims, open up “the riches of true knowledge, and heavenlie wisdom” to each person according to condition—to “the riche man,” “the poore man,” “He that wil rejoyce,” “They that are afflicted,” “the wicked”—“so that being wel practised herein, we may be assured against all dangers in this life, live in the true feare, and love of God, and at length atteine to that incorruptible crown of glorie, which is laid up for all them that love the comming of our Lord Jesus Christ.”Footnote 66 For the lay reader, to “practise” the psalms is to take from them understanding of one's own particular spiritual state. The reader who achieves this understanding receives not an earthly kingdom, like Elizabeth, but a heavenly one. Though nothing in the Geneva Bible's presentation of the psalms prohibits calendrical reading, neither does this presentation suggest it. The Geneva apparatus offers as much assistance to understanding as possible while leaving the path through the text to the reader's discretion. Tempering the anti-calendrical invective of 1559 serves to broaden the bible's appeal within a state whose confessional definition was still taking shape.

A later printing of the stand-alone Anglo-Genevan prose psalter, however, restored the more adversarial approach. William Seres (d. ca. 1579) came out with a close reprint of the 1559 Boke of Psalms in 1576, the same year Christopher Barker (1528/29–1599) began to print Geneva Bibles in England. This publication reproduces the text and apparatus of the 1559 edition almost exactly and includes the epistle, two tables, and incendiary “To the Reader” (still at the end). As a commercial enterprise, it almost certainly responds to growing objections to the psalm reading practices of the established church. The 1572 Admonition to the Parliament, a kind of manifesto for the Puritan cause, complains that Church of England clergy “tosse the Psalmes in most places like tennice balles,” a jab at antiphonal singing in cathedrals.Footnote 67 A 1577 refutation of Archbishop John Whitgift (ca. 1530–1604) by the Puritan Thomas Cartwright (1534/35–1603) targets the calendrical reading method specifically: “to make dayly prayers of [the psalms] hand over head, or otherwise then the present estate wherein we be, doeth agree with the matter conteyned in them: ys an abusing of them.”Footnote 68 In light of the genealogy constructed by A Brieff discours, the 1559 prose psalter would have appealed to Elizabethan Puritans as an alternative to psalters designed for “hand over head” use. Since Seres also printed common prayer psalters both before and afterward, his motive in reprinting the 1559 psalter in 1576 must have been economic rather than doctrinal. Nonetheless, the reprint shows that by that year an alternative to the common prayer psalter designed for occasional reading could make for a profitable business venture. While the neutral ground of the Geneva Bible remained the more frequent site of encounter with the Geneva prose psalms, Seres's publication demonstrates that in the decades following the Geneva Bible's first appearance, staunch divisions emerged in the way its psalms were read.

THE GENEVA BIBLE'S BOOK OF PSALMS AND ITS ELIZABETHAN READERS

How, then, were they read? Print offers an imperfect record of reader use since it demonstrates prescription rather than practice. Though still imperfect, reader markings provide a more reliable source. In order to establish a sense of the practices Elizabethan readers exercised on their prose psalters, I have surveyed traces of use in fifty-three copies of the Geneva Bible housed in ten libraries in England and the United States (see Appendix).Footnote 69 My study considers the first eight editions, four of which were realized in Genevan printing houses, four in England by Christopher Barker. Printed between 1560 and 1577, these editions include neither Books of Common Prayer nor texts or paratexts from the common prayer psalter, as became increasingly common after 1578. Apart from page size, their Books of Psalms remain unchanged from the 1560 first edition. Limiting observation of reader markings, some datable to the Elizabethan period, to these editions allows substantial recovery of the reception of the text and apparatus as the Genevan exiles had arranged them. It has the added advantage of making calendrical reading legible, because absence of the printed rota offers the opportunity for its insertion. The following analysis demonstrates the influence of the two reading methods described above, the calendrical and occasional, expressed in textual modifications and reader notes that imitate established printing practices. Remarkably, even such imitation evidences fierce reader independence from the prescriptions of the printed text: among the most frequent markings are those showing that the Geneva text was often put to common prayer use.

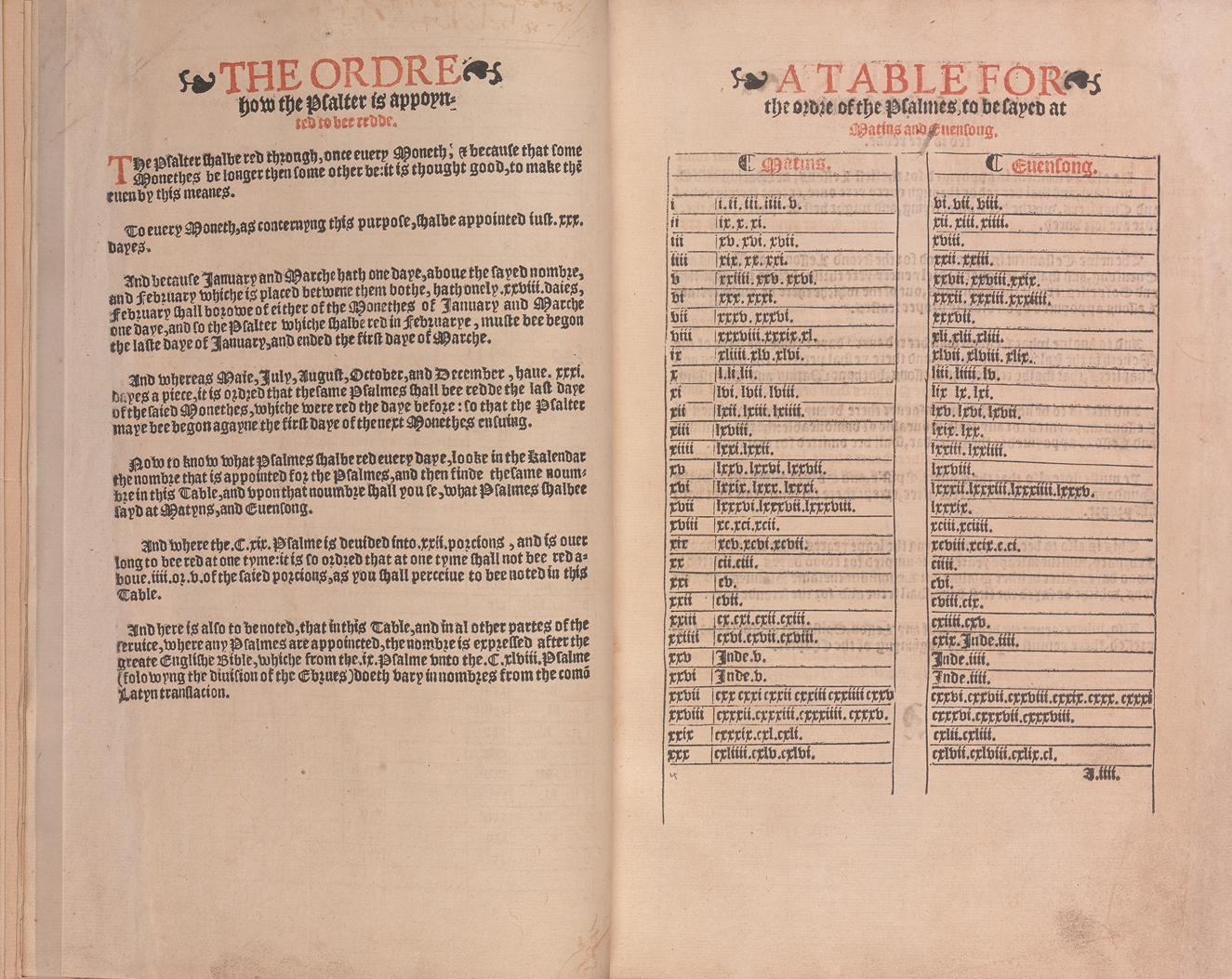

Reading against the grain was not always the norm. Reader markings often further interpretive practices initiated by printed text and paratext. Readers add cross-references, annotations, and corrections to their Geneva Bibles, sometimes amounting to a quantity of writing as dense as that printed in the margins. Although markings are seldom limited to any one book of the bible, the psalms’ central role in all varieties of Protestant worship regularly earns them extensive annotation, often tailored to their unique status as a collection of short poems. A late Elizabethan reader of a 1576 Geneva Bible housed at Cambridge University Library, for example, adds hundreds of cross-references to every page of the Book of Psalms, exponentially outstripping those printed in the margins (fig. 3).Footnote 70 The reader underlines a large portion of the text and paratext, penning cross-references directly on top of underlined language and providing explanatory annotations in Latin. Because such a reading practice relies on careful consultation of other passages of the bible, and because (quite simply) it demands the reader stop for extended periods of time to annotate, this reader must read discontinuously, focused on understanding rather than orderly procession.Footnote 71 More striking, however, is the reader's practice of labeling the genre of each psalm, a consistent Genevan strategy. The reader divides the psalms into eight generic categories, noting them in Greek alongside their printed numbers: Psalm 1 is διδακτικος (didactic), for its teachings on the life of the blessed; Psalm 2 is προφητικος (prophetic), for its proclamation of Christ's begetting.Footnote 72 Some psalms receive two generic headings: Psalm 40, for instance, is both didactic and prophetic because it provides the example of David's deliverance while foretelling deliverance through Christ. These generic distinctions are not the reader's invention but imported from a collection of psalm paraphrases by renowned Calvinist theologian Theodore Beza (1519–1605). The reader writes them in Greek because they are printed in Greek in Beza's Latin first edition of 1579, which the reader evidently has at hand. Readings of this sort appreciate the English Geneva Bible as participating in an international network of Calvinist scholarship intent on expanding knowledge of scripture for present application, the goal of those who produced this bible in the first place.Footnote 73

Figure 3. Cross-references and generic headings on the psalms in The Bible and holy scriptures, 1576. Cambridge University Library, Syn.4.57.15, [Old Testament] fol. 219r.

But readers often also put the Geneva prose psalms to a purpose quite other than that for which they were originally intended: handwritten markings of day and time demonstrate use of the psalms in accordance with the Prayer Book lectionary. Calendrical markings on the Book of Psalms appear in sixteen of the fifty-three copies consulted for the preparation of this article, or around a third. This figure rises to almost half when calculated with only quarto and octavo editions, those more likely to have been owned and used privately.Footnote 74 Since heavily used books tend not to survive, calendrical markings probably made their way into an even greater proportion of the Geneva Bibles circulating during the Elizabethan period. The markings are explicitly modeled on printed directions in common prayer psalters and Great Bibles. (Readers also frequently pen calendrical markings into editions of these texts published before the advent of the Prayer Book lectionary.) They usually take the form of a number in the margin designating the day of the month alongside the words “Morning prayer” or “Evening prayer,” sometimes with another number penned into the page heading for ease of locating that day's page. Within this basic framework almost any variation is possible. The numerals can be roman or arabic. “Morning” and “evening” can be abbreviated or reduced to a single letter, “prayer” is often omitted, and in a 1570 copy housed at the Beinecke, the Latin forms “mattins” and “vespers,” which the Book of Common Prayer abandoned in 1552, persist.Footnote 75 A mere “M1” and “E1” next to the psalm title, or even simply “m” and “e” with no other markings, sometimes suffice. Since the Prayer Book lectionary is used in Church of England practice to this day, the exact date, or even century, when these markings were made can be difficult to determine. Nevertheless, several copies with datable markings show that the practice was common during the sixteenth century.

Calendrical markings appear sometimes as the only markings in a bible's psalter, or even in the whole bible, sometimes amidst a network of markings evidencing other kinds of reader use. In the present study, the former case has proved the more common. In ten of the sixteen bibles with penned-in calendrical directions, these markings are the only substantive engagement with the biblical text (that is, excluding penmanship exercises, signatures, and other markings that do not demonstrate reading practice). In a 1560 Geneva Bible in Rutgers Special Collections, a stop-and-start calendar is the only form of marking in the entire volume.Footnote 76 Such exclusive marking suggests that, on the example of the common prayer psalter, readers found calendrical directions an essential feature of the text to be added the way a misnumbered page might be corrected, even when they do not otherwise record textual engagement.Footnote 77

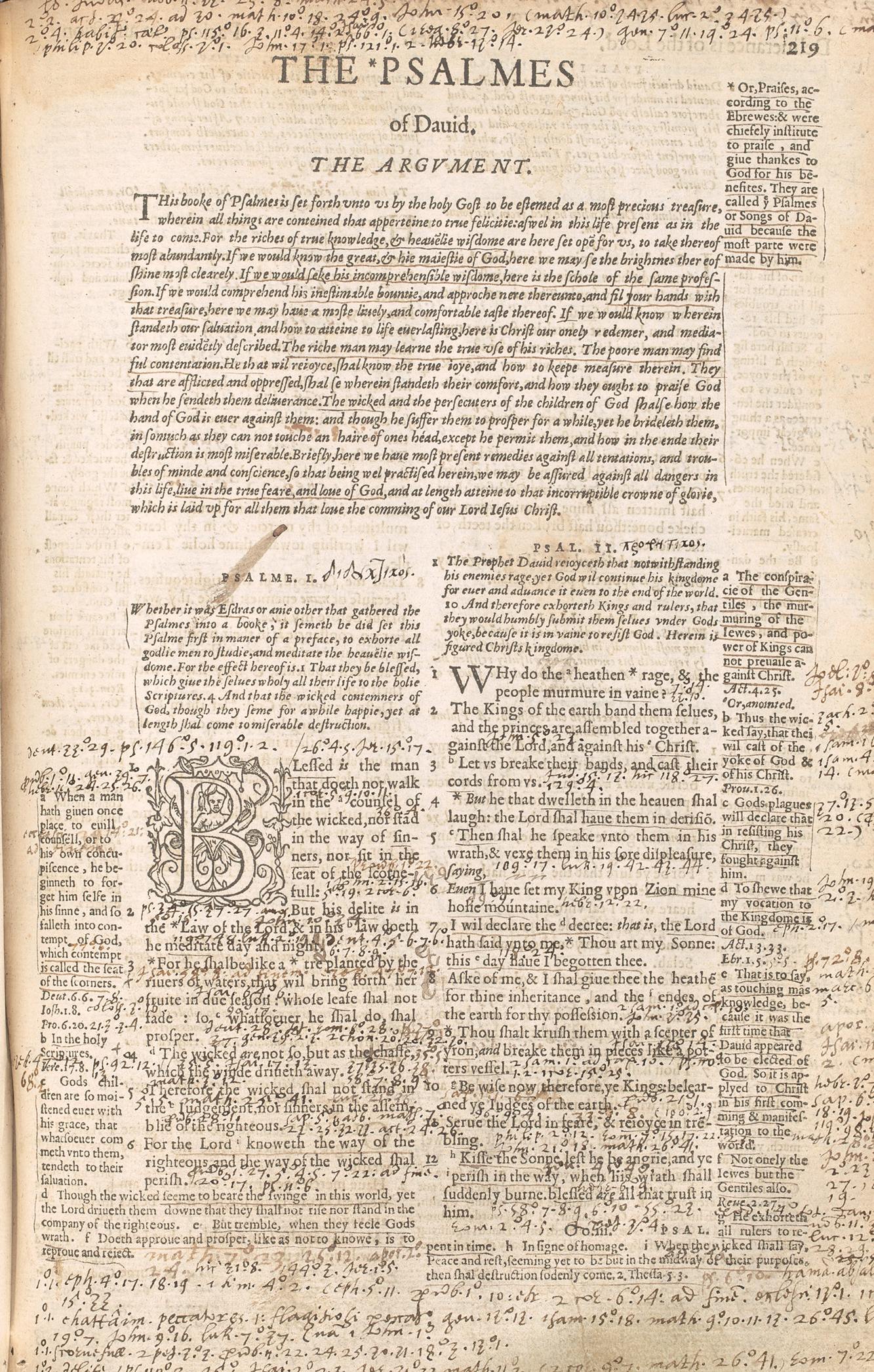

Though somewhat less common in this study, calendrical directions also appear as evidence of one reading strategy among many. Such is the case in another 1576 Geneva Bible in the collection of the Wren Library at Trinity College, Cambridge (fig. 4). This volume bears not only calendrical markings from the Prayer Book lectionary but also a penned-in table of Beza's psalm genres on the leaf before the psalms and a brief note at their end: “I ended the exposition of the Psalmes: 22. Aug. 1602: I ended them again 12. march. 1603. & began them the Sabboth after [vz?] the 18. of march.”Footnote 78 These markings, all in the same hand, suggest a reading practice of considerable complexity. This late Elizabethan reader goes through the psalms according to the Prayer Book lectionary but exhibits enough interest in Beza's table and the discontinuous reading it facilitates to copy it into the bible. Given the closing note, however, the reader uses Beza's paraphrases—the “exposition of the Psalmes” probably refers to a frequently reprinted translation of Beza by Anthony Gilby (ca. 1510–85), from which the genre table is also taken—in sequential fashion, reading one per day, as the supplied dates suggest.Footnote 79 That is, the reader exercises two forms of calendrical reading simultaneously. One imagines the reader reading the Prayer Book portion each morning and evening, but then, at some point during the day, progressing through the psalter more slowly, at the rate of one psalm per day, comparing the Geneva translation with Beza's paraphrase. At other times, the reader might navigate Beza's penned-in table to select appropriate psalms to use as personal prayers, perhaps jotting the cross-reference also found in the margins the while. Markings like these disclose the range and versatility of Elizabethan psalm reading, which often entails exercise of multiple strategies at once.

Figure 4. Beza's Table and calendrical markings on the psalms in The Bible and holy scriptures, 1576. Wren Library at Trinity College, Cambridge, C.2.37, [Old Testament] fols. 218v–219r. By permission of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge.

Markings show that setting, too, varies. Readers, in some cases, adapted the Geneva text to the Prayer Book lectionary for use in church. Since, as Archbishop Matthew Parker (1504–75) complained in a 1568 letter to Queen Elizabeth, the Geneva translation was itself “publicly used,”Footnote 80 a marked folio edition (like the one from the Wren Library) might indicate an unauthorized lectern bible used in church services or for study by enthusiastic congregants, while a quarto or octavo might be a bible brought in by a congregant in order to follow along with the service.Footnote 81 These adaptations could become quite extensive. To turn back momentarily to the larger network of Genevan texts, the Cambridge copy of the 1557 prose psalter, with a Geneva apparatus but a translation close to the Great Bible's, contains markings in an italic hand (probably dating to the seventeenth century) that not only add in calendrical directions but even alter the text to that of the common prayer psalter in the few instances where it deviates. The alterations sometimes coax the text innovatively, like at Psalm 19:4, when the reader corrects the beginning of the fourth verse, “the knowlege of theim is spred into all landes,” to the “sownde of theim is spred,” closer to the common prayer psalter's “their sound is gone out,” by writing an “s” and “nd” directly on top of the word “knowledge” while retaining the vowel sound (“ow”) as printed (fig. 5).Footnote 82 Alterations can also miss the mark: The reader modifies Psalm 17:2's “let thine eies beholde my just causes” to “let thine eies beholde the thing that is evil,” notwithstanding that the common prayer psalter has “let thine eyes look upon the thing that is equal.”Footnote 83 The error of “evil” for “equal” suggests that, in this case, the reader corrects while listening to an oral recitation of the psalm in church. In one instance, that of Psalm 14, the reader simply notes a discrepancy—“3 verses wanting”—without making any effort to compensate (more on this particular discrepancy below).Footnote 84 In addition to modifying the translation, the reader changes the verse numeration of the early Geneva version wherever it differs from that of the common prayer psalter and even replaces two missing leaves, containing portions of Psalms 78 and 146, with leaves containing handwritten transcriptions of their common prayer counterparts, now bound in with the 1557 Geneva text. Thus modified the text might be used in any Church of England service. The reader has effectively constructed a common prayer psalter out of Genevan materials.

Figure 5. The psalmes of David, 1557, with calendrical markings and corrections. Cambridge University Library, Peterborough.D.1.50, [The psalmes of David] 54–55.

The preponderance of lectionary markings in smaller-format Geneva Bibles demonstrates widespread domestic use. Like any number of reformers, Cranmer affirmed that “every man shulde reade by him selfe at home in the meane dayes and tyme, betwene sermon and sermon.”Footnote 85 To the extent that book ownership and literacy allowed, Elizabethan lay worshipers took his advice, imitating the clergy in their practice of the church lectionary.Footnote 86 The psalms they had at hand were often those in the Geneva Bible, which they probably used in conjunction with privately owned Books of Common Prayer.Footnote 87 The partial markings found in three small-format copies of the Geneva Bible, where the reader has begun to pen in a psalm lectionary and then stopped, affirm such private practice, since they likely designate actual reading patterns left incomplete, rather than one-off preparation of a volume for predicted use in the service, as might be expected in a lectern bible.Footnote 88 When they had a choice, readers may have even preferred the Geneva translation for its copious interpretive notes and apparatus.Footnote 89 A domestic reading practice could then unfold as a study session, in which the reader might pause to follow references or add marginal annotations while still adhering to the daily pattern.

If readers did not necessarily put the Geneva Bible to its foreseen use, neither did they put the lectionary. Ryrie points out that the psalm reading schedule was by far the most widely practiced portion of the lectionary, followed even by Knox, famous for his antipathy to the Prayer Book.Footnote 90 While he kept the common prayer lectionary out of Scottish liturgies, Knox must have considered a practice that he found intolerable as church prescription to be an appealing private routine. Some readers even made a game of the lectionary's unusual application. I have observed handwritten calendrical directions in two separate copies of a 1556 French-language Geneva Bible, both bearing signs of English ownership (fig. 6).Footnote 91 In one case, the calendrical markings are in French (“prieres p[our] le soir” [“evening prayers”]); in the other, in English (“M1,” “E1”). Since the Prayer Book lectionary is exclusive to the English Protestant tradition, in these cases, English readers applied their daily reading habits to a text even more remote from calendrical prescription than the English Geneva Bible, perhaps for French practice. Such varied use shows real enthusiasm for the spirit of the Prayer Book lectionary, if indifference to its letter.

Figure 6. Calendrical markings on the psalms in La Bible qui est toute la Saincte Escriture, 1556. Cambridge University Library BSS.207.B56.2, [Vieil Testament] fol. 211r.

In the hands of readers, both the Geneva Bible and the Prayer Book lectionary became versatile tools of worship. Readers did not feel constrained by the extent of the Geneva Bible's apparatus but were content to modify their bibles to suit their own purposes. That readers used the Geneva prose psalms in accordance with the Prayer Book lectionary furnishes one more piece of evidence for the well-established claim that the Geneva Bible was not a particularly Puritan text but embraced by readers of all ecclesiastical backgrounds.Footnote 92 The lectionary was not an exclusively conformist text either. Though the lectionary had been designed to establish uniformity of practice, and to that end assigned (if implicitly) a specific translation of the psalter, readers delighted in applying it wherever they wished. By using the Geneva text in their practice of the rota, readers at once adhered to the Church of England's prescribed pattern for calendrical reading, shunned its prescribed text, and registered their indifference to the intentions of the Geneva apparatus, which they revised at will. They retained autonomy from printed text and church prescription alike. As discussed below, such autonomy came to influence the practice of printers.

THE PSALTER OF THE BISHOPS’ BIBLE

The psalters appearing in Bishops’ Bibles of the 1560s and 1570s initiate a compromise in conventions associated with calendrical and occasional reading. It is generally accepted that the Bishops’ Bible, the royally sanctioned church bible produced under the direction of Archbishop Parker, was intended to provide scholarly competition for the Geneva Bible without entirely repudiating it.Footnote 93 David Daniell claims that it was meant specifically to block “the advance of the Geneva into churches,” a concern that might well account for the layout of its psalter.Footnote 94 The psalter of the 1568 first edition, a large folio aimed primarily at in-church use, offers a hybrid text of the sort readers had already been crafting for themselves in their Geneva Bibles. The text includes arguments and marginal annotations like those of the Geneva Bible, sometimes even borrowed from the Geneva Bible. The verses are numbered, and the translation has supposedly been made directly from the Hebrew, though the result falls short of Genevan rigor and is often cited as the worst part of a not particularly well-liked version.Footnote 95 Despite resembling the Geneva psalter in many elements of its format, the Bishops’ psalter also prints numbers for the days of the month in its page headings and “Morning prayer” and “Evening prayer” in the heading and margin. This layout marries the paratextual efforts of the Geneva prose psalter with those of the common prayer psalter. It implies that the psalms of the Bishops’ Bible are meant to be read both calendrically and occasionally; the reader is to work through them in accordance with a uniform method while also applying individual psalms to personal situation. The first iteration of the Bishops’ psalter attempts to fulfill the goals of the two cultures of psalm reading at once. In this sense, it provides the psalmic equivalent of the via media of the Elizabethan settlement.

The failure of the Bishops’ psalter to do justice to either goal gave rise to a fascinating episode in the history of prose psalter printing. Despite its apparatus, the unfortunate translation of the Bishops’ psalter prevented it from making inroads into church practice. Richard Jugge (ca. 1514–77), printer of all Bishops’ Bibles during his lifetime, shortly acknowledged this fact in print: the 1572 revised second folio includes a dual-columned psalter, displaying the common prayer psalms on the inner side of the page, the Bishops’ psalms on the outer side. The older psalter is labeled “The translation used in common prayer.” The new Bishops’ translation is labeled, optimistically, “The translation after the Hebrewes.”Footnote 96 In including two texts, Jugge honors the distinction between the two methods of psalm reading while recognizing the validity of both. Calendrical reading works through the psalter in accordance with church prescription; its practitioner therefore makes use of the black letter text on the inner side, the text used in church services since the reign of Edward VI. Occasional reading seeks accuracy and understanding; its practitioner turns to the outer side, to the corrected and annotated text in roman type. Within the context of the church, to which this expensive folio would have been mostly confined, one imagines the priest reciting the common prayer psalms for morning and evening prayer but studying and meditating upon the Bishops’ psalms. Both reading methods have their place within the new layout of the page. In addition, the 1572 psalter invites a third kind of psalm reading: comparative reading. It apportions verse numbers to the common prayer psalms, only the second time this had ever been done. With these in place, the enthusiastic congregant, staying behind to read after service, could assess where and to what extent the translations differ on a line-by-line basis. Since large Bishops’ folios were not widely owned, domestic readers were unlikely to face a crisis of conscience in deciding which text to look to in their daily practice of the lectionary. They would simply continue to work from the Geneva Bibles they had in their homes. Subsequent editions of the Bishops’ Bible—with the sole exception of one published in 1585—printed the common prayer psalter in place of the Bishops’, meaning readers would have the choice made for them in the future. Nonetheless, inclusion of multiple versions of the psalter in an “authorised” version of the bible illustrates adept printer response to the multiplicity of strategies employed by readers.Footnote 97 It also shows a willingness, one alien to twenty-first-century readers, to recognize the authenticity and authority of multiple translations at once.Footnote 98

THE PSALTER OF THE 1578 GENEVA BIBLE

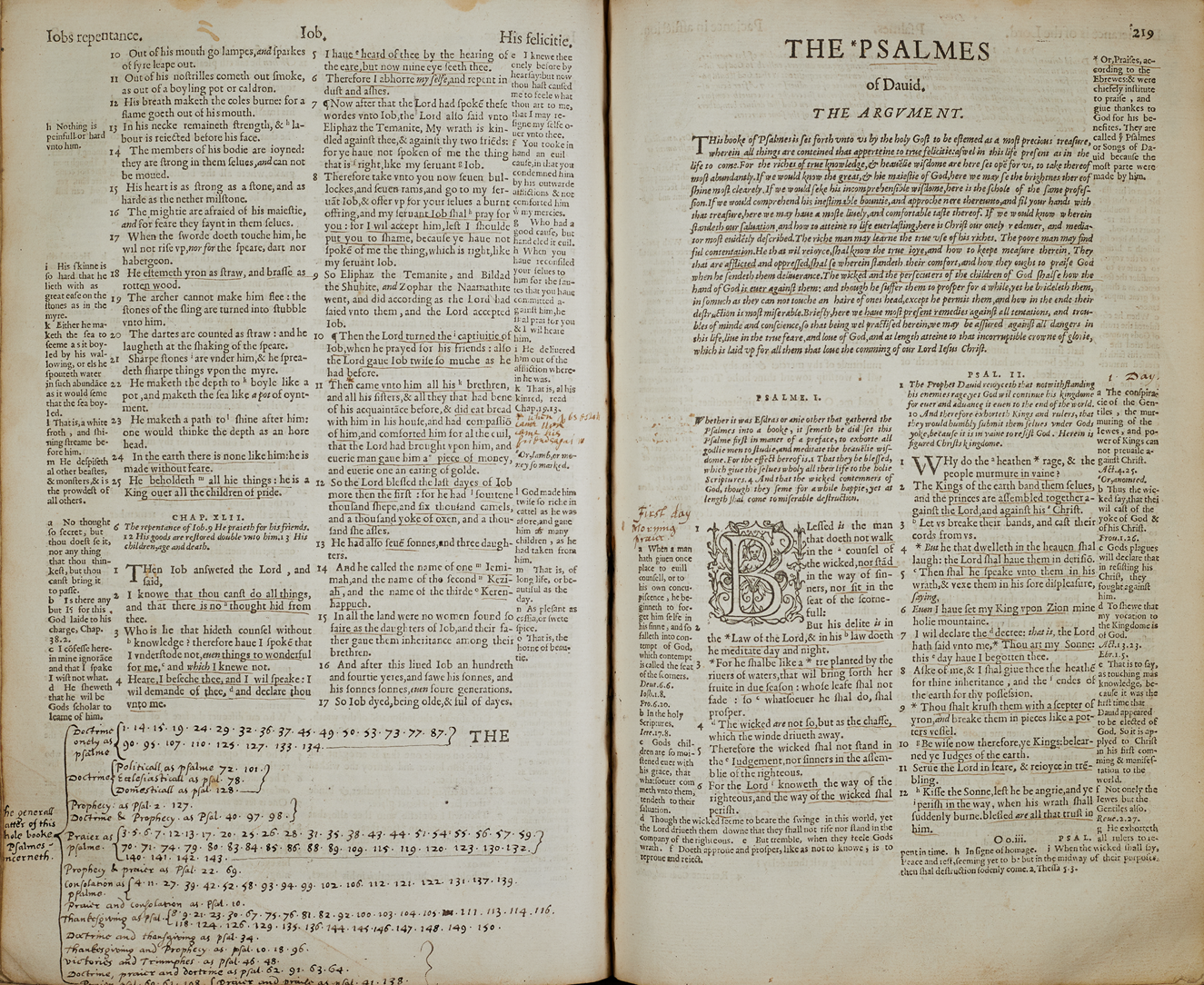

Remarkably, the Geneva Bible followed the Bishops’ lead. It, too, adopted the dual-columned psalter. For reasons not altogether clear, the Geneva Bible was not printed in England until after Parker's death in 1575. Shortly after Jugge's death in 1577, Christopher Barker obtained “exclusive rights” to the printing of all bibles in England.Footnote 99 In 1578, having already brought out two Geneva New Testaments and four full Geneva Bibles, Barker printed a large folio Geneva Bible—much larger than the preceding small folio Genevas—with the text for the first time in black letter. By all observable features, he intended this edition for the lectern. The psalter of Barker's Geneva Bible now took up the two-text layout from Jugge's 1572 Bishops’ Bible. The text prepared by Whittingham and others in Geneva stood alongside its rival, the common prayer psalter (fig. 7). The two columns are again labeled “translation used in common prayer” and “translation according to the Ebrewe” (more accurately this time), and again, the one bears black letter type, the other roman. Barker's alteration to the page heading, however, is striking. Unlike the 1572 Bishop's Bible, which reserved the heading for day and time, Barker prints the day on one side, the topic of the psalm on the other. The result is an even more perfect mélange of the conventions that had accreted around the common prayer psalter and Geneva prose psalter, respectively. The reader can now deploy calendrical or occasional reading without the apparatus weighing in on either side. Whereas the Bishops’ Bible attempted a compromise that still enforced—though multiplied—authorized translation, Barker's edition now elevates the unauthorized translation, the Geneva Bible's, to the status of the common prayer psalms. The composite text invites Elizabethan Protestants to use the psalter in the manner enjoined by the English Church or the Geneva apparatus or both. The text celebrates and affirms the composite nature of Elizabethan Protestantism: its participation in international Reformation, and its uniquely English heritage.

Figure 7. Psalms with underlining in The Bible, 1578. New York Public Library, *KC+ 1578, [Old Testament] fol. 211v.

Thus arranged, the psalter of the 1578 Geneva Bible also invites comparative reading. It retains the numbering of the common prayer psalms’ verses that the 1572 Bishops’ Bible included to facilitate comparison and, in one instance, even makes this intention explicit. Due to differences in translation, the numbering of the two columns frequently falls out of sync, generally by only a verse or two. In the case of Psalm 14, however, the common prayer column contains eleven verses while the Geneva column has only seven. In the empty space at the end of the Geneva translation, Barker adds a black letter note explaining the discrepancy: “Note that the 5. 6. and 7. verses in this 14. Psalme of the common translation, are not in the same Psalme in the text of the Ebrewe, but rather put in, more fully to expresse the manners of the wicked: and are gathered out of the 5. 140. and 10. Psalmes, and also out of the 59. of the Prophet Isaiah, and out of the 36. Psalme and are alledged by S. Paul, and placed together in the 3. to the Romanes.”Footnote 100 Barker's rather elaborate note not only details the procedure by which the additional verses came to be incorporated into Psalm 14—namely, because Paul cites Psalm 14 together with the other verses Barker mentions at Romans 3:13–18—but also justifies this procedure thematically, maintaining that by importing Paul's other citations the common prayer text manages “more fully to expresse the manners of the wicked.” The common prayer translation enriches the subject with a pastiche made upon scriptural precedent. Barker maintains the authority of the Hebrew, on the one hand, of the English tradition, on the other, and suggests that both are valuable for understanding the psalm. The two columns can and should be read together in order to gain a fuller picture of the whole.

The dual-columned psalter is only one result of Barker's attempt to produce a bible attractive to the widest possible segment of Elizabethan Protestants. Like many subsequent Geneva Bibles, but like none before, the 1578 printing is prefaced with a version of the Book of Common Prayer. This version is an abridgment. Though it retains all the material related to the lectionary, it omits the services for private baptism, confirmation, and the churching of women, as well as several rubrics. The term “priest,” current in the 1559 Prayer Book issued upon Elizabeth's ascension, is also replaced with the more Puritan-friendly “minister.” Long thought an “unauthorized puritan revision,”Footnote 101 Ian Green convincingly argues that the abridgement “was not the work of a puritan but someone trying to please puritans” and, moreover, that the abridger was likely Barker himself acting upon financial motivations.Footnote 102 If this is so, Barker's importation of the common prayer psalter and his attempt to justify its divergences likewise function as part of the project of cross-pollinating previously segregated texts and then softening church ceremony for Puritan appeal. Barker binds together texts and reading methods that had independently proved profitable for the sake of broadening his audience and selling more bibles. By packaging calendrical and occasional reading together, along with their two native, but previously opposed, translations—and by trying to reconcile these translations where they diverge most—Barker could place this bible in as many churches or other institutions as possible. While lacking the romance of theological synthesis, Barker's profit-seeking may be the most plausible explanation for why the common prayer and Geneva prose psalters appeared alongside one another even as fissures in the national church continued to expand.

AN ELIZABETHAN READER'S 1578 GENEVA BIBLE

Reading of Barker's 1578 Geneva Bible, as of Jugge's 1572 Bishops’, would usually have taken place in a church or university. At twenty-four shillings for a bound copy, twenty for an unbound, this bible was beyond the means of all but the wealthiest private households.Footnote 103 Although large-format bibles confined to public settings are less likely to contain markings than their smaller counterparts, the New York Public Library is home to a copy of the 1578 Geneva Bible that offers exceptional insight into the practice of an identifiably Elizabethan reader.Footnote 104 Almost every page bears signs of heavy use. Markings appear on all portions of the biblical text, apparatus, and supplementary material. The most common variety are underlinings and brackets, though there are also frequent manicules and even some illustrative drawings. Handwritten annotations stand in the margins throughout. The consistency of handwriting—though it sometimes lapses from italic to secretary hand within a single note—suggests that all markings are the work of one reader, a suspicion further confirmed by consistency of the markings’ preoccupations, especially with numerology and the liturgical use of the Apocrypha. There are no personal prayers, ownership markings, or markings unrelated to the biblical text (perhaps confirming institutional rather than domestic use).Footnote 105 Instead, interpretive notes in English, Latin, and French trace the textual tradition in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and even Chaldee.Footnote 106 The reader also cites other English translations of the bible: the bible of “Tho. Ma. 1537,” that is, the Matthew Bible; “the Englishe churche Bible authorised by parliament,” the 1539 Great Bible; and the bible of “G.M. the papist himself,” the 1582 Rheims New Testament, the work of English Catholic Gregory Martin (ca. 1542–82).Footnote 107 Taken together, the markings reveal an early modern reader, well versed in languages and contemporary biblical scholarship, using the 1578 Geneva Bible for intensive study.

While the scholarship cited would already suggest an early date, a handwritten note to the apocryphal book of Ecclesiasticus confirms both the markings’ Elizabethan provenance and the reader's entanglement with the age's doctrinal conflicts. The final chapters of Ecclesiasticus offer praise for important Old Testament figures, with eight verses of chapter 46 devoted to the accomplishments of Samuel. The last verse (46:20) lauds Samuel's prophesying of Saul's death from beyond the grave, an event related in 1 Samuel 28. In that chapter, the dead Samuel, summoned by the witch of Endor, tells Saul “to morow shalt thou and thy sonnes be with me.”Footnote 108 Christian exegetes have struggled with this moment because not only is necromancy forbidden by Mosaic law, but also the revered prophet Samuel ought to be in heaven, whereas Saul will certainly go to hell; it would be odd, therefore, that they should end up together. To get around this difficulty, Christians regularly claim that the Samuel of 1 Samuel 28 is not Samuel at all but Satan. Following this approach, the reader of the 1578 Geneva Bible rebukes Ecclesiasticus 46—which praises Samuel's prophecy as though Samuel were Samuel indeed—as a misrepresentation propagated by church ceremony: “The 46. Chapter is redde in o[u]r church for the first lesson at evening prayer the 17. Daye of November, even upon the daye of Quene Elisabeths raigne when all the bells are ronge for joye that sincerite & truthe is restored [to] Englande then is this false lye of Samuell redd in the churche the L[ord]. send her Longe raigne & soone to see & roote out all suche blind religions here remaining. aprill. anoe 158.”Footnote 109 17 November 1558 was the first day of Elizabeth's reign, as consultation of the bible's Almanack (where the reader has marked Ecclesiasticus 46 with a manicule) reveals. The church lectionary would thus have the deeds of Satan read as though they were Samuel's on the very day that reinaugurated England's Protestant faith, an age of supposed “sincerite” and “truthe.” The reader calls on Elizabeth to reform this aspect of the Prayer Book lectionary, dubbing church use of the Apocrypha—all passages of which the reader underlines in the bible's Almanack—“blind religion.” The tantalizing trimming of the page prevents discovery of the exact year of this annotation, but what remains is enough to establish that the reader is writing during the 1580s, within the first decade of the book's life. As such, the reader sides with a growing number of Puritans who viewed church use of the Apocrypha as a remnant of Catholicism, a position supported by the Geneva Bible's printed acknowledgment that the apocryphal books “were not received by a common consent to be read and expounded publikely in the Church.”Footnote 110 The note at Ecclesiasticus 46 and others like it reveal the reader as heavily invested in the religious controversies of the age, equipped with the scriptural knowledge to establish an informed opinion, and fully willing to dissent from the received practice of the Church of England.

Yet the reader's use of the abridged Book of Common Prayer discloses not a hot Protestant but a moderate. The reader reverses many of the changes that Barker had made for the sake of Puritan appeal. The reader underlines instances where Barker prints “minister” for the 1559 Prayer Book's “priest” and restores the latter term in the margin. In addition, beneath the printed instructions for public baptism, the reader writes out the instructions for private baptism, removed by Barker because Puritans feared that private baptism enabled covert Catholic practice.Footnote 111 The reader likewise restores an abbreviated form of the “Confirmacion” and a missing rubric from the end of the “order for the visitation of the sick.” (The only major abridgment the reader does not restore is the churching of women.) These restorations—which would find their way into later abridged Prayer Books coming from Barker's pressFootnote 112—place the reader in a position associated with the mainstream church with respect to the Book of Common Prayer, notwithstanding a Puritan position with respect to the lectionary. Ryrie argues that “many Protestants were both puritans and conformists.”Footnote 113 This reader is one such, adopting positions specific to the devotional practice at hand.

What position does this reader adopt toward psalm reading? When turning to the psalter, the reader engages both columns of the text, but with a difference. The Geneva column, as even a cursory glance reveals, boasts far more annotation than the common prayer column. There are underlinings in ink of several colors on all but a few of its psalms, likely indicating an attempt to sort out multiple readthroughs for practical application. These underlinings sometimes highlight single keywords—“decree” in Psalm 2, for instance—but more often phrases or even whole verses of particular importance or moral edification—for example, Psalm 30's “weeping may abide at evening, but joy commeth in the morning.”Footnote 114 There is one note on the Geneva translation of the Hebrew: the reader pens “not in the hebrew” and “in the hebrew” in the margins of Psalm 35:7 to contest the Geneva's judgment—made by use of black letter for interpolated words—regarding which of the verses two “pits” the original claims to have been “digged” for the psalmist's soul.Footnote 115 There is also a cross-reference at Psalm 51:7's “Purge me with hyssope” to indicate that whereas the printed Geneva note only cites Leviticus 14:6, the hyssop ritual also appears at Exodus 12:22.Footnote 116 Thirty-seven brackets flank the Geneva text at moments of significance, such as doxologies. A marginal “4” indicates the fourfold repetition of the phrase “sing praises” in Psalm 47:6 (part of the reader's numerological preoccupation).Footnote 117 Even the printed Geneva notes receive attention, boasting two brackets (for a gloss on “Rahab” in Psalm 87:4 and another on idolatry in Psalm 106:20) and one underline for the women—“Miriam, Deborah, Judith”—to whom a note to Psalm 68:11 claims “the Lord gave matter” for songs of victory.Footnote 118 In sum, the Geneva text and its apparatus warrant careful scrutiny recorded in an elaborate system of markings. Many of these markings aim at selection of notable portions of the text, perhaps in preparation for lessons or sermons, but others engage the Geneva apparatus, either highlighting printed annotations of interest or expanding commentary along similar lines. The Geneva text is read in accordance with its framers’ intentions: for appropriation and understanding.

The common prayer column, by contrast, is almost bare. Outside of Psalm 119, where the reader marks more freely, it garners only five markings. Three of these clearly indicate comparative reading (of the sort Barker's formatting suggests). At Psalm 6:7, the reader underlines the “beautie” of the common prayer psalter's “My beautie is gone for very trouble” to indicate that it is the less theologically suggestive “eye” of the Geneva's “Mine eye is dimmed for despite.”Footnote 119 At Psalm 18:45, the reader underlines “shall dissemble with me” to highlight its divergence from the Geneva's “shal be in subjection to me,” which the Geneva note nonetheless concedes can also mean “lye.”Footnote 120 And at Psalm 105:28, an underline in the common prayer psalter notes that “not obedient” becomes “not disobedient” in the Geneva, where it refers to Moses and Aaron rather than Pharaoh.Footnote 121 In one case, Psalm 49:16, the reader begins to underline a verse in the common prayer psalter before ceasing mid-phrase and underlining the whole verse in the Geneva text.Footnote 122 Since the phrase is the same in both texts, the common prayer underlining must be a readerly blunder, likely caused by habituation to single-translation texts. At Psalm 137:7, there is a single instance of cross-reference, namely, to 1 Esdra 4:45 and Revelation, linking the fall of the temple remembered in the psalm to the New Jerusalem to come.Footnote 123 The reader marks the common prayer Psalm 119—a long acrostic psalm of twenty-two sections—more freely, writing English-letter equivalents of the Hebrew-letter headings for each section, underlining six individual words (sometimes where the words read alike in both columns), and adding one set of brackets.Footnote 124 But even there the tendency is to note discrepancy, especially of a doctrinally consequential nature: for instance, the common prayer psalter's “ceremonies” in verse 8 for the Geneva's “statutes,” a distinction at the heart of the old Anglo-Genevan objection to the Prayer Book service. The reader's sparing use of manicules on the Geneva column further confirms comparative reading. At Psalm 68:4, the reader indicates, with Geneva-facing brackets and manicule, that the common prayer psalter entirely omits the name “Jah,” God's “essence and majestie,” according to the printed Geneva gloss,Footnote 125 and at Psalm 72:19, brackets and manicule point out that the second doxology of the common prayer psalter reads only “Amen. Amen” in place of the Geneva's puzzling “HERE END THE prayers of David the sonne of Ishai,” puzzling because this psalm is not where David's prayers end at all.Footnote 126 Thus, where the common prayer column is marked, or even acknowledged, these markings show either extension of the strategies exercised on the Geneva column or, more frequently, a comparison between the two. The occasional method, with some help from its cousin the comparative, would seem to take the day.

Does this reader also read calendrically? Given the reader's careful use of other aspects of the Prayer Book, along with the fact of just how widespread use of the psalm lectionary was, it seems likely. Calendrical reading would have even been mandatory in church services, which were themselves mandatory. Evidence of such reading does not appear, however, and this absence points to a serious asymmetry in the indelibility of certain reading practices. Reading for emotional understanding, the Genevan ideal, frequently entails further textual creation. In the search for one's individual place within the integrated meaning of scripture, there are always more cross-references to uncover, more interpretations to broach, more markings to make. But ritual adherence to the calendar does not tell the same tales. The text it creates is a set of directions, like stage directions in a play, to use a frequent comparison for liturgy.Footnote 127 Once these are present, the next step is to perform. Since Barker already prints directions in his 1578 Geneva Bible, there are no more markings to make; there remains only to read. In fact, absence of markings aimed at refutation of the calendrical directions—the type the reader lodges against church reading of the Apocrypha—strongly suggests adherence.Footnote 128 Though the conclusion is necessarily speculative, print, in this case, appears to have anticipated practice.

But even if the reader used the psalm lectionary eagerly, it is not clear which of the two texts the reader would have read. By including the common prayer psalms, the 1578 Geneva Bible facilitates continued use of this translation for morning and evening prayer, even as it suggests (with a touch of heterodoxy) liturgical use of the Geneva translation for other books of the bible. Yet outside the service, daily reading might have been exercised on either column or both. The Geneva prose psalms were by this point widely read in accordance with the lectionary, a situation of which Barker's 1578 Geneva Bible is rather symptom than cause. The very same year, Henry Denham (fl. 1559–90), ensign to William Seres, put out another sextodecimo reprint of the 1559 Anglo-Genevan prose psalter, which not only included the anti-calendrical “To the Reader” (finally at the front) but also printed calendrical directions. Even Barker himself released a small quarto version of the Geneva prose psalms (along with Ecclesiastes and Song of Songs) that included printed calendrical directions in the margins. The clear streams of textual production had muddied. If the markings on the common prayer psalms of the 1578 Geneva Bible at the New York Public Library might have been the product of daily calendrical reading, so too might those on the Geneva column. The reader may well have embraced the copia of Barker's text to exercise as many distinct kinds of reading on as many distinct portions of the text as the bible at hand made available. Such copious reading would be in keeping with an age in which reading strategies multiplied, sometimes opposing one another, sometimes conspiring, but an age virtually defined by the seriousness of its engagement with scripture.

CONCLUSION