The category and perception of a class of performers known as singer-songwriters did not emerge into public consciousness until after 1968. Indeed, Google Ngram shows that the term ‘singer songwriter’ has no usage prior to the early 1970s. It is true that there were individuals referred to as ‘singer and songwriter’ as early as the 1870s, and earlier in the twentieth century the descriptions ‘singer songwriter’ and ‘songwriter-singer’ were used. These terms are rare, however, after World War II.1 The ‘singer-songwriter’ is not anyone who sings his or her own songs, but a performer whose self-presentation and musical form fit a certain model. There had been rock singers who wrote their own songs since Chuck Berry, but they were not singer-songwriters. Bob Dylan, who helped create the conditions for their emergence, was not himself called a singer-songwriter in 1968, and he did not produce an album that fit the label until Blood on the Tracks in 1974. While the singer-songwriter becomes highly visible in 1970, in retrospect we can see that the movement emerged in 1968, when Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell, and Laura Nyro released important early examples. What distinguished the singer-songwriter was both a musical shift away from the more raucous styles of rock and a lyrical shift from the more public concerns that had helped to define the folk revival. By the early 1970s, James Taylor, Mitchell, Carole King, Jackson Browne, Carly Simon, and others created a new niche in the popular music market. These singer-songwriters were not apolitical, but they took a confessional stance in their songs, revealing their interior selves and their private struggles.

The year 1968 was a turning point not only because it was the high-watermark of the New Left, but also because it saw the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the bloody police riot at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, and the disappointment of Richard Nixon being elected President and the Vietnam War continuing unabated. Up until 1968, youth culture was hopeful about progressive change and about individual opportunities, but the events of that year began to alter the dominant outlook. In the summer of 1969, Woodstock provided a few months of uplift, but the shift was solidified in the reading given to the free concert at Altamont in December. The anti-war movement would continue, of course, and the student strikes of the 1970, which shut down more than 450 campuses in the wake of the Kent State shootings and the US invasion of Cambodia, might be seen as the largest manifestation of the student Left, but also its last gasp. There would be no major campus ‘unrest’ in the years that followed. In the summer of 1969, Students for a Democratic Society, the leading New Left organisation, disintegrated. One of its fragments, the Weatherman faction, turned to a strategy of violence it hoped would incite the working class to join them. It resulted rather in the opposite reaction, and made the New Left look loony, dangerous, and out of touch. There had been sporadic violence throughout the 1960s, but as Time reported in early 1971, even the Weatherman group, by then reduced to a tiny underground contingent, had publicly forsworn violence after an explosion killed three of its own in a Manhattan apartment used for bomb-making. Time noted this as part of what it called ‘the cooling of America’, discussed in a ten-page special section, which observed that ‘In rock music … a shift can be perceived from acid rock to the soft ballads of Neil Young, Gordon Lightfoot, and James Taylor’.2

Time’s ‘cooling’ thesis is questionable with regard to music. The Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, and Grand Funk Railroad represented the emergence in the early 1970s of what Steve Waksman has dubbed ‘arena rock’, the latter three representing the roots of what would by the end of the decade be known as heavy metal. As Waksman’s title, This Ain’t No Summer of Love, suggests, he also sees the ‘decline of the sixties’, but in favour of ‘the growing demand for a heavier brand of rock’.3 Moreover, while Time’s assertion that ‘Large numbers are alienated from present political patterns. . . they believe that all the effort and idealism they have expended on such issues as the war and racism have had little impact on Washington’4 is doubtless correct, that does not mean that one can account for the rise of the singer-songwriter entirely in terms of a retreat from the politics of the New Left. For one thing, even among the young, it is not clear that opposition to the war, much less to racism and other social inequities, was ever a majority view. For another, the student Left was never driven purely by these issues. Nick Bromell argues a ‘sense of estrangement from everything that might give life meaning is what the writers of the Port Huron Statement [the founding document of SDS5] were trying to articulate as a political problem when they claimed that people are “infinitely precious and possessed of unfulfilled capacities”, and when they opposed “the depersonalization that reduces human beings to the status of things”’.6 The insistence on the personal in the work of the singer-songwriters remains consistent with this position. The rock audience was maturing. While The Beatles had expanded the audience for rock and roll to include college students, a younger cohort, who had been early teens when The Beatles invaded, was now entering college. With The Beatles having broken up, they were looking for something new. But it is also true that new political issues were emerging. One might hazard a guess that female listeners in particular sought not only more mature themes, but also perspectives that matched their own experiences as women, especially in light of the women’s movement that was emerging at just this moment.

The key to understanding the changes in popular music in the early 1970s is the realisation that the market was already beginning to fragment. By 1969, the top 40 format, which had long dominated radio, was being challenged. Progressive rock stations were programming album tracks – and sometimes, whole albums – instead of singles. Bands like Grand Funk and Black Sabbath, who appealed to younger listeners, continued to be heard on top-40 stations, while the singer-songwriters clearly benefited from the style and mood of new stations. In place of shouting and hype, the new format featured DJs who spoke, if not quite in hushed tones, more or less conversationally. Their approach was no longer to sell, but to curate. But it was not just changes in rock that mattered. Another condition for the emergence of the singer-songwriter was the decline of folk as a distinct style and scene. The early issues of Rolling Stone, a magazine identified strongly with rock, give a good sense of this process. In one of its first issues in 1967, one finds a story about Joan Baez going to jail to protest the draft and a notice of Judy Collins’ new album, Wildflower, of which is observed, ‘for the first time she has written her own material for the record … three of her original songs’.7 Baez was known as a folksinger and Collins is identified as such, but their very presence in Rolling Stone is evidence that the boundary between rock and folk had already become flexible.

An indication of the way in which the singer-songwriter would be understood is apparent in Jon Landau’s positive review of James Taylor’s self-titled first album. The review begins,

James Taylor is the kind of person I always thought the word folksinger referred to. He writes and sings songs that are reflections of his own life, and performs them in his own style. All of his performances are marked by an eloquent simplicity. Mr Taylor is not kicking out any jams. He seems to be more interested in soothing his troubled mind. In the process he will doubtless soothe a good many heads besides his own.8

These remarks reveal the moment of the singer-songwriter’s emergence with striking clarity. One key point is the connection Landau makes to folk music, which is utterly inaccurate. The folk revival of the 1950s and early 1960s had little to do with reflections of individual lives. Folk music of this era was a celebration of community. It promised to put the listener in touch with ‘the people’, and even when its lyrics were not explicitly political, the identification of it with the people made it a political statement. As one of the chief proponents of the revival, Izzy Young put it, ‘the minute you leave the people, or folk-based ideas, you get into a rarified area which has no meaning anymore’.9

Bob Dylan is, of course, a key figure in the transition from folk to singer-songwriter music even though he was not himself a singer-songwriter until later. Dylan’s very early work is folk, and Dylan’s songs were heard as public music and not private revelation even though as early as ‘It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue’, he was writing songs that were rooted in his private experience. But this song, along with later expressions of similar emotion, such as ‘Maggie’s Farm’ and ‘Like a Rolling Stone’, were not heard as particularly personal. And the dominant emotion they seemed to express, anger, is one not typically associated with introspection. Dylan, however, did turn to introspection in ‘My Back Pages’, a song that was heard as repudiation of his earlier, more political stance.10 Irwin Silber in ‘An Open Letter to Bob Dylan’, published in Sing Out (November 1964), wrote about songs that would later be released on Another Side, ‘I saw at Newport how you had lost contact with the people … [the]new songs seem to be all inner-directed, no, inner-probing, self-conscious.’11 In 1965 Izzy Young describes Dylan and others going through a ‘period of gestation from “protest” to “introspection”’.12 But Dylan moved away from introspection in his work of the later 1960s, which culminated in Nashville Skyline (1969), an album of commercial-sounding country music.

Folk music began ‘a sharp commercial decline’ in 1965, the year Dylan performed his fabled electric set at the Newport Folk Festival.13 Almost at the same time, folk rock emerged as a successful commercial genre, but the singer-songwriter movement did not in the main come out of folk rock, which retained folk’s public orientation and married it to rock beats and arrangements. The first singer-songwriters were people who came from outside rock. These emerge in 1968, including Randy Newman, who had been writing songs since 1961, releasing his first album (Randy Newman) in 1968, Laura Nyro, who had been part of folk scenes in New York and San Francisco, with Eli and Thirteenth Confession, and Canadian poet Leonard Cohen releasing his first album (Songs of Leonard Cohen). All of these records would be influential, and taken together they are evidence of change in popular music. But these first buds of the singer-songwriter spring are not in the main typical of what the movement in the 1970s would become. Those central to mainstream of the singer-songwriter in 1970s had some connection to the folk movement itself. A key figure in the transition from folk to singer-songwriter was Tom Rush, a folk performer who did not mainly record his own compositions. According to Stephen Holden, Rush ‘was the first to popularize songs by Jackson Browne, James Taylor, and Joni Mitchell’14. In 1968, Rush released Circle Game, which included songs by all three, at a time when only Mitchell had an album of her own. It may be the Tom Rush of Circle Game whom Jon Landau was thinking of when he listened to James Taylor, especially since Landau was then writing for Boston’s Real Paper and Rush’s home base was the Boston area folk scene. Rush’s most famous composition, ‘No Regrets’, first released on Circle Game, is an introspective song that has more in common with the confessional songs Mitchell would later write than with those Rush recorded on this album. ‘No Regrets’ recounts the narrative of a past relationship in images that belie the chorus’ assertion that the singer has no regrets about its ending. While this disjunction makes the song a bit less overtly confessional than, say, ‘Fire and Rain’, or ‘River’, it is more personal than Mitchell’s contemporary work.

James Taylor was the first of the group to emerge clearly as a new kind of performer. That did not happen with his first album, which despite good notices did not sell many copies. In 1969, he appeared to acclaim at the Newport Folk Festival, where he met Joni Mitchell who would be his girlfriend for the next several years. But it was not until the success of his second album, Sweet Baby James, and especially the song ‘Fire and Rain’, which got wide AM airplay, that Taylor began to be recognised as ‘a new troubadour’ and ‘the first superstar of the seventies’.15 What distinguished the new singer-songwriters was the confessional mode, and ‘Fire and Rain’ was the first song in this mode to become a hit.

‘Fire and Rain’ illustrates the confessional mode perfectly. As I have written elsewhere, ‘What is remarkable about “Fire and Rain” is the starkness of the pain and despair it reveals. Pop music had long featured laments about lost love, but being pop they seemed to be conventional rather than personal. “Fire and Rain”, however, advertises itself as autobiography.’16 It does this, however, not by the explicitness of its references – or by their truth or accuracy – but by the language of the lyrics and the style in which the song is performed. That fans heard the song as autobiographical is clear from the press coverage, although while the song was on the charts the references remained obscure. In early 1971, Rolling Stone explained the autobiographical background of each verse: a friend’s suicide, Taylor’s heroin addiction, and the break-up of Taylor’s first band, the Flying Machine.17 Rolling Stone and the nearly simultaneous New York Times Magazine piece also discuss at some length Taylor’s confinement on two occasions in mental hospitals, one of which he sang about in an early song, ‘Knockin’ Round the Zoo.’ Indeed, both of these long articles are more focused on Taylor’s personal life than on his music.

As I argued in Rock Star, songs like ‘Fire and Rain’ came to be called ‘confessional’ because of a perceived similarity to the poetry of what by the late 1960s was being called the confessional school. Robert Lowell’s Life Studies (1959) was the first book to be discussed as confessional, its poems making explicit use of autobiographical materials presented in a relatively plain style, especially compared to the more elaborate diction and poetic effects of his earlier work. Among the other members of the school were three of Lowell’s writing students, W. D. Snodgrass, Sylvia Plath, and Anne Sexton, the latter two embodying for many a connection between confessional poetry and the emerging women’s movement. Clearly, one appeal that this poetry had for readers was its sense of authenticity; it seemed to be not only telling the truth, but also telling it about problems that anyone might suffer. Confessional poetry, however, was not defined by its accuracy to the facts of the author’s life. For the critic who first named the movement, M. L. Rosenthal, the key issue is the way that the self is presented in the poems, the poet appearing as him or herself and not in the convention of an invented ‘speaker’.18 As Irving Howe explained later, ‘The sense of direct speech addressed to an audience is central to confessional writing.’19 That sense of direct address is present in ‘Fire and Rain’ and in many other songs of Taylor, Mitchell, and Browne. In other words, what mattered ultimately is not whether the details were true, but that they were presented in a form that made them seem so.

Joni Mitchell’s Blue (1971) cemented the confessional stance of the singer-songwriter. Mitchell’s previous release, Ladies of the Canyon (1970) had included a mixture of confessional songs, such as ‘Willy’ and ‘Conversation’, with the more folk-like compositions ‘Circle Game’ and ‘Big Yellow Taxi.’ Blue leaves out the folk sound and lyrics entirely, in favour of a style likened at the time to both ‘torch’ songs and ‘art’ songs.20 Yet neither of these labels is quite right. The lyrics establish a sense of direct address and autobiographical reference by using more or less conversational language, including specific details of time and place. Like ‘Fire and Rain’ which begins, ‘Just yesterday morning’, and Mitchell’s ‘River’, opens with ‘It’s coming on Christmas’, Mitchell’s ‘Carey’ is set in a tourist town where she complains of having ‘beach tar’ on her feet, while ‘A Case of You’ and ‘The Last Time I Saw Richard’ include accounts of particular taverns. These latter two songs also include fragments of conversations, giving them a documentary character. There is also often a sense of helplessness that Taylor and Mitchell’s songs share with confessional poetry. Taylor cannot remember to whom he should send the song his friend’s death has provoked him to write. Mitchell complains that she is ‘hard to handle,’ selfish’ and ‘sad’, a description that sounds strange in the first person. The admission of such failings, along with revelations such as Taylor’s stay in a mental hospital, point to another dimension of the term, ‘confessional’, the sense that secrets are being revealed. Finally, there are musical cues that make us feel that what we are hearing is a direct address to us and not a performance or show meant mainly to entertain. I have already noted that the singer-songwriters moved away from the sing-along style, with its catchy melodies, major chords, and upbeat tempos typical of the folk revival. What we get instead are Mitchell’s open tunings or Taylor’s unusual chords presented at a slow tempo in arrangements that distinguish these recordings as something other than folk. The accompaniment, unlike in much rock, allows the lyrics to take the foreground, but it is also distinctive, individualising the material rather than making it sound traditional.

Rosenthal had understood Lowell’s confessional poetry as ‘self-therapeutic’.21 One finds evidence of that in both Taylor and Mitchell as well. Taylor’s songs on first several albums often report on his mental state, or describe one, such as when he’s ‘going to Carolina’ in his mind. Mitchell’s songs may be less obvious about their therapeutic intent, but it’s hard to read songs like ‘River’ any other way. Why is the singer telling us she’s selfish and sad? In an interview in 1995, Mitchell said of this song, ‘I have, on occasion, sacrificed myself and my own emotional makeup … singing “I’m selfish and I’m sad” [on “River”], for instance. We all suffer for our loneliness, but at the time of Blue, our pop stars never admitted these things.’22 Earlier, she had said she ‘became a confessional poet’ out of ‘a compulsion to be honest with my audience’.23 Later, Mitchell herself would deny that her songs were confessional, rejecting the idea that she wrote them under ‘duress’, and describing their motive as ‘penitence of spirit’.24 It is not clear that confessional poetry directly influenced singer-songwriters like James Taylor or Joni Mitchell. But whether the singer-songwriters were reading Plath or Lowell is irrelevant to the fact of the similarities in the two bodies of work and that the audiences for each seemed to like them for similar reasons.

One of those reasons has yet to be addressed. Rosenthal does not value Lowell’s poetry merely because of its shift away from high-modernist norms or its honest expression. He reads these poems as expressions of social critique that reveal ‘the whole maggoty character’ of American culture that the poet ‘carries about in his own person’.25 With regard to Life Studies this may be a strong reading, but Lowell went on, in the sonnets that would make up the Notebook and History volumes, to write poetry that was explicitly critical. And with Plath and Sexton, the fusion of personal revelation and social critique was much more widely perceived. These poems were commonly understood as feminist statements by 1970, and this connection leads us to reconsider the question of whether the emergence of the singer-songwriter represented a retreat from politics or social concerns. While the new genre clearly represents a change in focus and in attitude from public confrontation and anger to personal struggle and a reflective sadness, it does not entail a rejection of social concerns.

Indeed, feminist issues were often entailed in the concerns of the singer-songwriters, and this mode was well suited to their expression. Joni Mitchell became known as a performer who expressed a distinctly female perspective (see Chapter 18). ‘Mitchell’s songs illustrate the notion that the personal is the political by the way in which they deal with the power dynamics of intimate relationships.’26 Feminist organising in the second wave was focused on consciousness raising, that is, helping women understand that what had seemed to be merely private problems were in fact the product of systemic male dominance. Consciousness raising might be seen as a confessional form because it asked women to publicly voice their personal issues. Moreover, the turn away from confrontation and anger, while not entirely reflective of the women’s movement, can also be seen as consistent with feminism’s goals. Because feminism could not succeed by depicting men and women as inherently opposed camps, its expression needed to offer the possibility of mutual understanding and positive personal transformation for both genders. Mitchell refused to call herself a feminist, saying that the term was ‘too divisional’, but that very refusal reveals the desire for a different kind of politics. Here songs gave voice to the concerns of many women by using her own life as an example. But one could argue that it was not just female singer-songwriters who raised feminist concerns. While I will not assert that Taylor, Browne, or the Dylan of Blood on the Tracks were intending to make feminist statements, by reflecting on their roles in intimate relationships, they were at least beginning to react to a key feminist demand.

By 1972, the phenomenon of the singer-songwriter was already widely recognised, as Meltzer’s profile of Jackson Browne from that year reveals:

for those of who were listening Jackson … was the prototype singer-songwriter years before it had a context. He was ahead of his time so they called him a rock singer, an individual rock singer without a band. The only others at the time were people like say, Donovan and [Tim] Buckley and Tim Hardin – and Donovan was already recording with a group, in fact, they all were. Certainly Jackson was not folk, that category had already been erased from the slate.27

Browne’s confessionalism was less consistent than Taylor’s or Mitchell’s at this time, but one song on For Everyman, his second album, ‘Ready or Not’, is as clear an example of the mode as one can find. The song is a narrative in which the singer describes how he met a woman in a bar, took her home for the night, and discovers soon after that she is pregnant. As Cameron Crowe describes it, the story is about the origin of Browne’s first child, Ethan, and meeting of his mother, Phyllis, ‘the model, actress, and star of the bar-fight/knock-up adventure described in Jackson’s song’.28 The song’s attitude differs from that of ‘Fire and Rain’ or ‘River’ in being someone what distanced and ironic. The singer is not depressed, but bemused. Browne would continue to mix confessional material with more public songs, and he would be associated with environmentalism and the anti-nuclear movement.

Carole King and Carly Simon were also widely understood to be important examples of early 1970s singer-songwriters, and they would both further the mode’s association with feminist concerns. While on the whole these artists’ work was less confessional than Mitchell’s, it was understood as direct address. King had begun writing songs with partner Gerry Goffin in the early 1960s, and the duo penned hits for a long list of artists including The Shirelles, The Drifters, The Animals, The Byrds, and Aretha Franklin. King did not release her first record as a singer, Writer, until 1971, but it was her second album of that year, Tapestry, that broke through. The album included a version of ‘Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow’, a song she and Goffin had written for the girl group The Shirelles who made it a hit ten years earlier. Susan Douglas argued that The Shirelles’ recording had made female sexual desire explicit, but King’s version made the song’s question seem personal.29 But the big hit from Tapestry was ‘I Feel the Earth Move’, a much more explicit celebration of a woman’s pleasure in sex. Carly Simon’s ‘That’s the Way I’ve Always Heard it Should Be’, called into question the traditional expectation that marriage was what all women want. As Judy Kutulas described it, ‘Simon situated her song within feminism and self-actualising movements with lines such as “soon you’ll cage me on your shelf, I’ll never learn to be just me first, by myself”.’ The performance, by contrast, was hesitant and fragile, conveying uncertainty.30 Her later hit, ‘You’re So Vain’, upped the autobiographical ante, making everyone wonder about whom the song was written. The songs of both King and Simon were perceived as authentic and personal, even if the personalities they expressed seemed more stable than those of Mitchell or Taylor.

As the singer-songwriter genre developed, it did not remain bound by confessionalism per se, though it retained the idea of authentic individual expression. Even in the early 1970s, there were artists associated with the movement, such as Gordon Lightfoot and Cat Stevens, whose work was less explicitly personal. Lightfoot’s big hit was ‘The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald’, a traditional ballad about a Great Lakes shipwreck. But the confessional mode has continued to be used, from Dylan’s account of the break-up of his marriage in Blood on the Tracks to Richard and Linda Thompson’s record of their break-up, Shoot out the Lights (1982), on through to Suzanne Vega, Tori Amos, Liz Phair, Alanis Morissette, Juliana Hatfield, Laura Marling, and many others. The emergence of the singer-songwriter was not just a moment in the early 1970s, but the start of a new formation that continues to this day.

The era of the German Lied stretched approximately from the mid-eighteenth to the early twentieth century. It flowered most richly during the nineteenth century, chiefly in the hands of four leading composers: Franz Schubert (1797–1828), Robert Schumann (1810–1856), Johannes Brahms (1833–1897), and Hugo Wolf (1860–1903). Altogether they produced more than a thousand songs, from which the core Lied repertoire is drawn today.1 These men were fine pianists although none was a singer of their own material except in the loosest sense.2 This chapter focuses on figures who were both composers and performers of their own material, in other words, possible precedents for a modern conception of the singer-songwriter. Their activity has often been overlooked because the concept of the public song recital was in its infancy for the greater part of the nineteenth century, so while most singers sang songs within mixed programmes, none could earn a living exclusively in this way and most participated in a thriving salon culture.3 Many were women, who benefited from the opportunities for musical training which emerged in the late eighteenth century. In comparison, professional pianists or even conductors, as in Schumann’s case, had clearer routes to establishing a professional identity. Indeed, from the very outset, the piano was integral to Lied performance. Therefore although the term ‘Lied singer-songwriter’ is used throughout this chapter, the implication is always, in fact, Lied singer-pianist-songwriter. This chapter traces the history of Lied singer-songwriters in three stages: a consideration of Schubert’s predecessors and contemporaries (c. 1760–1830), Schubert’s followers (c. 1830–48), and finally, contemporaries of Brahms and Wolf (c. 1850–1914).

Broadly speaking, the Lied evolved from a technically undemanding type of music largely aimed at amateur (often female) singers, to a genre which eventually dominated professional recital stages in 1920s Berlin.4 Various interlinked factors contributed to this shift: the rise of institutionalised musical training; the concomitant emergence of the idea of a ‘recital’; and the astronomical growth of the music publishing industry, which made sheet music for every conceivable technical standard available to the public.5 Songwriters worked in an ever more complex environment which coexisted with (but did not fully supplant) the original, amateur, private nature of the genre.

The years 1820–48 were arguably the golden age of the Lied singer-songwriter, since the genre had matured in Schubert’s hands, whilst the keyboard writing was still usually within the reach of a keen amateur. From the mid-century onwards, many instances of the genre were so pianistically demanding that singers without the requisite keyboard skills could only hope to compose simpler, folk song derived types that persisted throughout the century. While Lied singer-songwriters were almost inevitably superb singers themselves, the compositional emphasis upon the accompaniment grew.6 As musical training grew more specialised, multi-skilled musicians became increasingly rare. Nowadays, there is not a single professional Lieder singer who would consider accompanying themselves onstage, and only a few would have the keyboard skills to accompany themselves in private.

Schubert’s predecessors and contemporaries

The work of a number of early Lied singer-songwriters includes examples of two coexisting, but discrete, influences: the virtuosic Italian sacred and stage music which dominated the courts and public performance spaces of the Holy Roman Empire; and the new, transparent, folk-styled German Lied which emerged in response to the literary and philosophical theories of Johann Christoph Gottsched (1700–1766) in the 1730s.7 Gottsched’s contemporary, the tenor Carl Heinrich Graun (1703/4–59), exemplifies this split. A professional tenor at the court of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Graun composed the simplest of Lieder alongside his Italian opera, court and church music. His songs appeared in various compilations from 1737 onwards. The ‘Ode’ below, drawn from the posthumously published compilation Auserlesene Oden zum Singen beym Clavier (1764) is a typical example.

Example 2.1 Graun, Auserlesene Oden zum Singen beym Clavier (1764), vol. 1, no. 7, ‘Ode’, bars 1–6.

The singer and composer Johann Adam Hiller (1728–1804) is now mainly remembered for his operas. Hiller greatly admired his predecessor Graun, and like him, was proficient in the techniques and styles of Italian opera.8 By his own admission, in the 1750s his tastes drew him increasingly towards the ‘light and singable, as opposed to the difficult and laborious’.9 Hiller’s importance in the development of German musical culture lies not only in his composition of songs, but also in his commitment to raising the standard of public concert singing:

It has always been a concern of mine to improve the state of concert singing. Previously this important task had been regarded too much as a lesser occupation, and there was no other singer except when one of the violists or violinists came forward, and with a screechy falsetto voice … attempted to sing an aria which, for good measure, he could not read properly.10

Hiller was involved with the subscription concerts of the Grosse Concert-Gesellschaft in Leipzig, and also founded his own singing school, which embraced general musicianship, choral and solo singing.11 Crucially, he supported the training of women, and several female singer-songwriters of the next generation studied with him, including Corona Schröter (1751–1802), discussed further below, and Gertrud Elisabeth Schmeling (later Mara) (1749–1833). Hiller drew his pedagogical aims into his songwriting, thus aria-like works sit alongside simple folk-style tunes in his collections. These include the Lieder mit Melodien (1759 & 1772), Lieder für Kinder (1769), Sammlung der Lieder aus dem Kinderfreunde (1782), and 32 songs in the Melodien zum Mildheimischen Liederbuch (1799).

The great Lied scholar Max Friedlaender (1852–1934) argued that this was the point at which the German Lied became truly independent of foreign models.12 Hiller’s generation of songwriters consisted of a mixture of amateurs and professionals, singers, composers, poets, collectors and editors. Their activity acquired huge ideological and political significance in Germany following Johann Gottfried von Herder’s coining of the term ‘folk song’ (‘Volkslied’) in the 1770s: this would define the distinct cultural identity of ‘Germany’, a country which did not yet exist except in the imagination of its peoples.13 By the early nineteenth century, building on Herder’s ideas, writers like the Schlegel and Grimm brothers regarded folk song as a ‘spontaneous expression of the collective Volksseele (or folk soul)’.14 This new manifestation of German identity had to be accessible, in keeping with the way that lyric poetry was developing; indeed, poetry and music were so closely wedded that the term Lied applied equally to poems as to songs. The poetry often consisted of ‘two or four stanzas of identical form, each containing either four lines of alternating rhymes or rhymes at the end of the second and fourth lines only’.15 The melodies were often short and memorable, supported by the barest of accompaniments. Importantly, the prevailing aesthetic of simplicity meant that the singing and composition of the Lied was not limited to technically skilled professionals as, say, the composition of operas and symphonies might be. This ideology persisted well into the next century, endorsed by influential figures such as the writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) and the song composers Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752–1814) and Carl Friedrich Zelter (1758–1832). Melody remained paramount; the accompaniment would ideally provide just harmonic support, ‘so that the melody can stand independently of it’.16 It is therefore unsurprising that some of Goethe’s amateur associates in his home town of Weimar were more prolific Lieder composers than many professional musicians.17 Alongside its political weight, the Lied was also the symbol of culture in the upper classes, evidence of Bildung or self-cultivation.

The Lied was also considered respectable for women in a way that opera could never be. Goethe’s friend Corona Schröter was a beneficiary of Hiller’s belief that women should have access to musical education. A singer, actress, composer and teacher, Schröter published two Lieder collections in 1786 and 1794, prefacing the first set with an announcement in Cramer’s Magazin der Musik: ‘I have had to overcome much hesitation before I seriously made the decision to publish a collection of short poems that I have provided with melodies … The work of any lady … can indeed arouse a degree of pity in the eyes of some experts.’18 A sense of her compositional style can be seen in Example 2.2. Schröter was also an important voice and drama teacher. She was awarded a lifelong stipend for her singing by the Duchess Anna Amalia of Weimar and her voice was praised by both Goethe and Reichardt.19 Despite her close association with Goethe (she acted in and composed incidental music to his play Die Fischerin of 1782), her compositions are hardly known.20

Example 2.2 Schröter, ‘Amor und Bacchus’ (published 1786), bars 1–12.

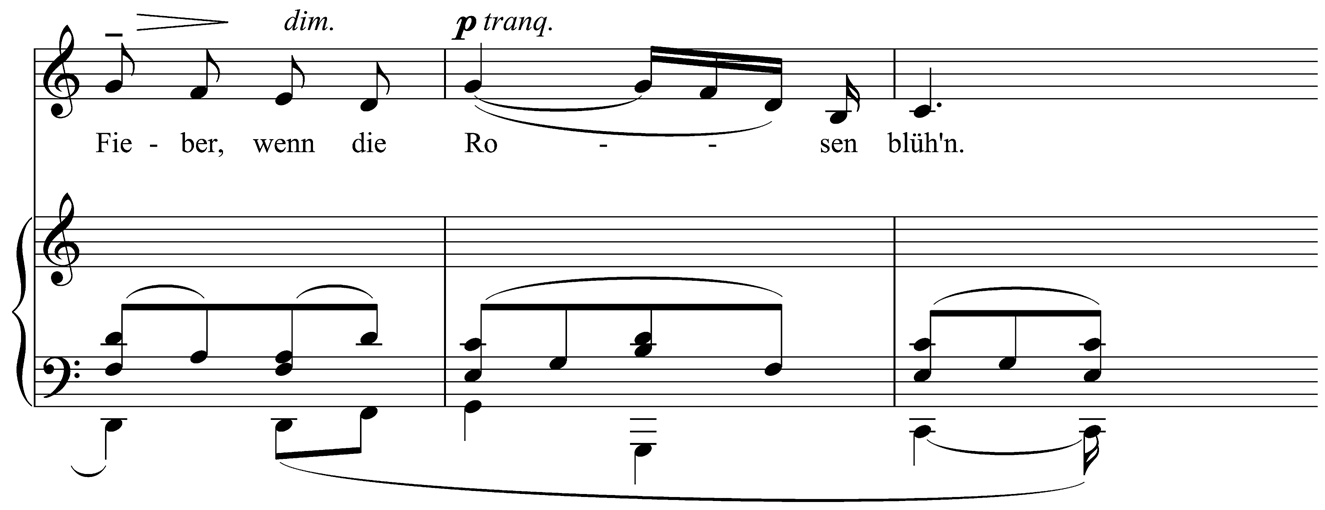

In an age when the two leading songwriters, Zelter and Reichardt, were not singers of their own songs, it is figures like Schröter who emerge as central. Two other women who, unlike Schröter, had no access to formal musical education but benefited from their cultivated home environments, were Luise Reichardt (1779–1826) and Emilie Zumsteeg (1796–1857). Reichardt was the daughter of Johann Friedrich Reichardt. She gleaned her musical knowledge from the illustrious company which frequently met in her father’s home in Giebichenstein near Halle, for whom she regularly sang. These figures included the leading lights of German literary Romanticism such as the Grimm brothers, Ludwig Tieck, Novalis (Friedrich von Hardenberg), Joseph von Eichendorff, Clemens Brentano, and Ludwig Achim von Arnim. Luise Reichardt was a remarkable woman. She moved to Hamburg in 1809 while her father was still alive, supporting herself as a singing teacher and composer. Additionally, she played a central role in bringing Handel’s choral works to wider attention, translating texts and preparing choruses for performances which were then conducted by her male colleagues. Although her compositional achievements were overshadowed by her father’s, she wrote more than seventy-five songs and choruses, many of which became extremely popular. Some of her songs were published under her father’s name in 12 Deutsche Lieder (1800). Luise Reichardt’s ‘Hoffnung’ (see Example 2.3) was so popular that it endured well into the twentieth century in arrangements for small and large vocal ensembles, particularly in English translation under the title ‘When the Roses Bloom’.

Example 2.3 Luise Reichardt, ‘Hoffnung’, bars 1–18.

Reichardt’s contemporary Emilie Zumsteeg was also the daughter of one of the most successful songwriters of the day, Johann Rudolf Zumsteeg (1760–1802), who lived in Stuttgart. Emilie Zumsteeg had a fine alto voice and developed a substantial career as a pianist, singer, composer and teacher.21 Like Luise Reichardt, Emilie Zumsteeg’s social circle included many leading poets of the day, which stimulated her interest in the Lied. She wrote around sixty songs, and her Op. 6 Lieder were praised in the national press. Almost a century later, they were still singled out for their rejection of Italian vocal style: ‘After this modish Italian entertainment music, it does us much good to get acquainted with the simple, straightforward and intimately sung German songs of Emilie Zumsteeg.’22 The quality of Zumsteeg’s voice was reflected in the relative adventurousness of her compositions; the same reviewer also observed that the first and third song of the set required a larger vocal range than usual.

Bettina von Arnim (1785–1859) presents a very different model of Lied singer-songwriter from the professionally independent Reichardt, Schröter, and Zumsteeg. The sister of one great poet, Clemens Brentano, and the wife of another, Ludwig Achim von Arnim, she too existed in a highly cultivated literary circle that encouraged a text-centred conception of the Lied. Although she composed roughly eighty songs, most of these are fragments, since her true strength lay in improvisation. Von Arnim ‘constantly struggled to commit her ideas to paper and permanence’.23 Only nine songs were published in her lifetime.24

The Westphalian poetess Annette von Droste-Hülshoff (1797–1848) was one of a significant number of nineteenth-century writers who composed settings of their own and others poets’ verses. These settings tended to follow transparent folk song models, reflecting the original ideological underpinning of the Lied as poetry/music for the people. Similar songs by the poets Hoffmann von Fallersleben and Franz Kugler were absorbed into German folk culture and reproduced anonymously in anthologies throughout the century.25 Von Fallersleben in particular popularised his songs through his own performances. The children’s songs he composed remain popular nursery rhymes in Germany today, while his patriotic songs are still sung by male-voice choirs.

Von Droste’s musical activity was more in keeping with her cultivated and aristocratic background in Westphalia. Music was practised at a high standard at home and was complemented by frequent visits to the theatre and concerts. Her letters reveal her to have been a great admirer of keyboard improvisation, when it was well done, and this is also evident in her songs.26 She was a highly competent pianist; one letter to a friend recounts the events of a concert in which she was to participate with another singer: ‘Finally, when the concert was about to begin, Herr Becker, who was to accompany us, declared that he couldn’t do it and that I, therefore, would have to play the piano myself … well, it went fine and we were greatly applauded.’27

Von Droste’s composition was further stimulated by her growing interest in collecting folk songs (through the influence of her brother-in-law, the antiquary Johann von Lassberg). As a result, she made an arrangement of the Lochamer Liederbuch, one of the most important surviving collections of fifteenth-century German song, in c. 1836. Her uncle, Maximilian Friedrich von Droste-Hülshoff (1764–1840), also gave her a copy of his 1821 guide to thoroughbass, entitled Eine Erklärung über den Generalbass und die Tonsetzkunst überhaupt. Drawing together these various influences, she made settings of her own poetry and verses by leading writers such as Goethe, Byron, and Brentano. None were published in her lifetime.

Women singer-songwriters generally came from well-to-do, cultivated families which offered creative stimulus through an educated social circle – essential in the absence of widespread opportunities for formal training. While gifted Italian women could gain an outstanding musical education, this was not the case in Germany.28 Barred from most public activity, the Lied offered women an arena in which they could be creative without transcending the limitations imposed by societal mores. In other words, women, as well as men, could compose songs, but the professional status of ‘composer’ was deemed appropriate only for men. The nature of the genre fixed it in the home, a space in which women could perform their own compositions without attracting criticism. Following the work of Hiller, Schröter, Zumsteeg and others, education for women flourished. The idea of the Lied as private entertainment and edification was increasingly embraced by a ‘bourgeoisie now prosperous and ambitious enough to want to imitate the sophisticated leisure of the upper classes’.29

Most importantly, from the 1810s onwards, Schubert exploded the limits of the genre by revolutionising the piano accompaniments, and fusing a German sensibility with the richness of Italian vocal music (thanks to the influence of his teacher, the distinguished composer Antonio Salieri (1750–1825)). The tenor Johann Michael Vogl (1768–1840) was thirty years older than Schubert, but their collaboration was to bring about the ‘professionalisation’ of Lieder-singing. The ‘German bard’s’ memorable performances of Schubert’s songs with the composer himself at the piano were widely celebrated.30 Like Schubert himself, Vogl initially trained as a chorister.31 His own compositions included masses, duets, operatic scenes and, of course, Lieder.32 As an aside, Vogl’s two published volumes of songs evince a range of influences from cosmopolitan Vienna: the folk-like German Lied and his professional background as an operatic singer. As a result, while his songs are generally quite straightforward, they are not formulaic (see Example 2.4).

Example 2.4 Vogl, ‘Die Erd’ ist, ach! so gross und hehr’ (published 1798), bars 1–20.

Lied singer-songwriters after Schubert

Despite the transformations effected by Schubert, the political and ideological urge to resist the evolution of the Lied was very much alive. In 1837, long after Schubert’s death, the Lied was defined in Ignaz Jeitteles’ Ästhetisches Lexikon as possessing: ‘easily grasped, simple, undemanding melody, singable by the amateur; a short or at least not lengthy lyric poem with serious or comic content; the melody of the Lied should only exceptionally exceed an octave in compass, all difficult intervals, roulades and ornaments be avoided, because simplicity is its main characteristic.’33 Such a definition could just as easily have been penned half a century earlier. At the same time, public song performance was burgeoning, culminating in the baritone Julius Stockhausen’s performances of complete song-cycles by Schubert and Schumann in the mid-1850s and 1860s.34 Within this maelstrom of influences, the Lied could be anything from the simplest tonal melody accompanied by a few chords, to vocally and pianistically virtuosic songs for the concert stage. In this context, it is worth turning to two Viennese Lied singer-songwriters: Johann Vesque von Püttlingen and Benedict Randhartinger. Each represented a strand of song-making that has been largely forgotten, but was just as productive and popular as works by the masters of the genre.

The distinguished diplomat, jurist, musician and artist Johann Vesque von Püttlingen (1803–1883) was extremely well-connected. He participated in soirées with Schubert, Vogl, the composer Carl Loewe, and the playwright Franz Grillparzer. However he also socialised with composers of the next generation including Robert Schumann, Otto Nicolai, and Hector Berlioz. He even sang his own settings of the poetry of Heinrich Heine to Schumann, who liked them very much.35 Vesque exemplifies the thriving and unselfconscious culture of amateur song performance and composition in the nineteenth century. Like many figures of the Biedermeier period, he was astonishingly proficient in many diverse areas. He was skilled enough to take the tenor role in Schumann’s oratorio Das Paradies und die Peri at the Leipzig Gewandhaus when the singer due to perform had to cancel at short notice – a testament to just how porous the term ‘amateur’ was.36 Under the pseudonym ‘J. Hoven’ (which drew on the last two syllables of Beethoven’s revered name), he composed 300 songs, of which no fewer than 120 are settings of Heine. His 1851 song-cycle of Heine settings, Die Heimkehr, is, at 88 songs, the longest in musical history. After the revolutions of 1848, which were not only a political but also a cultural watershed in Austro-Germany, Vesque’s songs were dismissed as sentimental and old-fashioned. Nevertheless, many have innovative forms, exceptionally well-crafted melodies, and imaginative accompaniments. See, for instance, the rippling, watery texture he devised for the opening of ‘Der Seejungfern Gesang’ (The Song of the Damselfly) Op. 11 no. 2:

Example 2.5 Vesque, ‘Der Seejungfern Gesang’ Op. 11 no. 2, bars 1–6.

It has also been pointed out that Vesque anticipated some aspects of Wolf’s songs, particularly his flexible, speech-like setting of the German language.37 See, for example, Op. 81 no. 58 ‘Der deutsche Professor’:

Example 2.6 Vesque, ‘Der deutsche Professor’ Op. 81 no. 58, bars 1–15.

Vesque’s songs also testify to the quality of his voice. There is no doubt that he deserves to be better known as an exceptionally successful amateur singer-songwriter.

One further Viennese Lied singer-songwriter is the tenor Benedict Randhartinger (1802–1893). Like Schubert, he studied at the Wiener Stadtkonvikt and also with Salieri, before joining the Wiener Hofmusikkapelle. Alongside many other works, he wrote an astonishing four hundred songs, and was successful as a professional performer of his own works – a singer-songwriter in the truest sense, and one with the added lustre of having known Schubert and Beethoven personally.38 Indeed, he was so highly regarded that in 1827, he was ranked alongside Schubert and Franz Lachner as one of the ‘most popular Viennese composers’.39 Clara Schumann and Franz Liszt were among his accompanists.40 He had particular success with his dramatic ballads, a sub-genre of German song that gained enormous popularity through the century.

An important influence on Randhartinger was the north German tenor and composer, Carl Loewe (1796–1869). Loewe’s development as a singer-songwriter was shaped by a promise he made to his devout father, a Pietist cantor, not to write music for the stage; possibly as a result of this, he channelled his sense of the dramatic into his songs and ballads, some of which are nearly half an hour long and show some similarities to dramatic scena. He was also a highly successful composer of oratorios. For most of his life, Loewe was the civic music director in Stettin, the capital of Pomerania near the Baltic Sea. He taught at the secondary school during the week and supplied music for the local church on Sundays.41 However, during the summer holidays, particularly from 1835–47, he travelled and built his reputation as a performer of his own ballads. His performances were enjoyed in Mainz, Cologne, Leipzig, Dresden, Weimar, and Vienna, and further afield in France and Norway.42 In 1847 he even performed for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in London.43 Among his fans was Prussia’s crown prince, who later became King Friedrich Wilhelm IV.44

Loewe’s ballads have remained in the repertoire, but many are unprepossessing on the page. Randhartinger apparently preferred Schubert’s songs to Loewe’s because he found them more ‘singable’; it is possible that Randhartinger found the demanding vocal range of Loewe’s songs not to his taste.45 Nevertheless, as with Schubert, Loewe’s first opus from 1824 already marked him out as a songwriter of great imagination and distinction, as is seen from the drama of the vocal line and the detail of the shimmering, unearthly accompaniment in Example 2.7.

Example 2.7 Loewe, ‘Erlkönig’ Op. 1 no. 3, bars 1–14.

The rapid decline of Loewe’s tremendous popularity suggests that his own interpretation was central to the success of the music. His recitals had an intimacy that distinguished them from the public world of, say, the piano recital. There were never more than two hundred people in the audience. Given the small scale of this musical career, Loewe’s fame is all the more remarkable. For Schumann, Loewe was nothing less than a national treasure, who embodied a ‘German spirit’, a ‘rare combination of composer, singer and virtuoso in one person’.46

Lied Singer-Songwriters in Brahms’ and Wolf’s day

By the second half of the century, opportunities for singer-songwriters were shifting. On one hand, it was increasingly acceptable for women to have concert careers (if not operatic careers) after marriage. On the other hand, the Lied onstage had evolved well beyond the simple folk song, thereby excluding anyone who was not truly proficient on the piano.

The career of the teacher, composer, singer and pianist Josephine Lang (1815–1880) showed how the possibilities of publication for female Lied singer-songwriters had been transformed. The daughter of a noted violinist and an opera singer, Lang was a precociously talented pianist who composed her earliest songs when she was just thirteen years old.47 At fifteen she met Felix Mendelssohn, who listened to her performing her own Lieder, and he praised her talent warmly, calling her performances ‘the most perfect musical pleasure that had yet been granted to him’.48 Lang was to publish over thirty collections of songs during her lifetime, as well as gaining a considerable reputation as a singer at the Hofkapelle in Munich.49 Her circle of friends included Ferdinand Hiller, Franz Lachner, and Robert and Clara Schumann. She married the poet Christian Reinhold Köstlin in 1842; when he died in 1856, she supported herself and her six children through teaching. Lang, like Vesque, wrote songs which merit greater attention, as evinced by the opening of ‘Schon wieder bin ich fortgerissen’, published in 1867 (see Example 2.8).

Example 2.8 Lang, ‘Schon wieder bin ich fortgerissen’ Op. 38 [39] no. 3, bars 1–18.

Pauline Viardot-García (1821–1910) was a tremendously successful singer from a family of celebrated vocal performers. Sister of Maria Malibran and daughter of Manuel García, she enjoyed success on the operatic stage as well as the concert platform, and regularly appeared in London, Berlin, Dresden, Vienna and St Petersburg. A fluent speaker of Spanish, French, Italian, English, German and Russian, she composed vocal works in all of these languages (over a hundred items in all), and also added vocal parts to piano works by Chopin.50 Her Lieder include settings of poems by Eduard Mörike, Goethe and Ludwig Uhland, including her very first published song: a setting of Uhland’s Die Capelle which she produced at the request of Robert Schumann for inclusion in his journal, the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, in 1838.51 As a cosmopolitan performer and composer, Viardot-Garcia’s contribution to the Lied is small but significant, given her close friendships with the Schumanns, Mendelssohn, Brahms and Wagner. She was also an influential vocal teacher.

In the last few decades of the nineteenth century, the Breslau-born George Henschel (1850–1934) emerged as an exceptionally gifted singer, pianist, conductor and composer who did much to promote the Lied in Germany, England and America. Henschel was a member of the Brahms circle and a protégé of the violinist Joseph Joachim and his wife, the contralto Amalie. The Joachims were keen to support Henschel’s career as a singer, and he appeared in many concerts alongside Amalie Joachim, who was a great proponent of the Lied in public concerts.52 Henschel later performed with Brahms in the mid-1870s; but by this stage, he was already accompanying himself in private gatherings.53 Following a hugely successful debut in London in 1877, he travelled to the United States in 1880 with his Boston-born fiancée, Lilian Bailey (1860–1901), who was also a singer. When the two gave their first Boston recital on 17 January 1881, Henschel took the role of singer and accompanist, playing for both himself and his bride-to-be.54

Henschel’s importance as a Lied performer was twofold. He was one of the first performers to give regular vocal recitals in which there were almost no non-vocal items – he turned away from the traditional ‘miscellany’ model of programming in order to put the song centre-stage.55 He also acted as the sole interpreter of his own compositions on many occasions, and both the accompaniments of his own pieces, and those of other songs he chose to perform, suggest that he was a prodigiously talented pianist. His numerous song compositions include twenty-five numbered opus sets for solo voice, several collections for duet and vocal quartet, choral works and an opera. Since he was popular with both English and German-speaking audiences, many of his Lieder were published with English translations, and he also composed many songs to English poems, such as Tennyson’s Break, Break, Break and texts from Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies.56 They range from straightforward parlour pieces, almost certainly intended for an informal setting, to more pianistically and vocally complex items, such as the ballad Jung Dietrich, Op. 45, published in c. 1890:

Example 2.9 Henschel, ‘Jung Dietrich’ Op. 45, bars 1–16.

The decline of the Lied is often dated to the outbreak of the First World War, with Richard Strauss’ Vier letzte Lieder of 1948 as its epilogue. As a result of Germany’s defeat, the growing international popularity of the genre was abruptly halted; within the nation, other changes took place which affected its fate. It should be stressed, however, that in the pre-war period, the Lied was more popular than ever.57 For this reason, it is more accurate to talk of a fragmentation of the Lied than a decline, and this was brought about by a range of social and musical factors. Firstly, the collective political impetus behind the Lied – the establishment of the German nation – was defused through Prussia’s victory in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1, which led to the establishment of a unified German nation. The narrowing of professional pathways, and the rise in complexity of both vocal and piano parts meant that the likelihood of finding a single performer capable of singing and playing the piano at a professional level had decreased. In connection with this technical elevation, composers sought to lift the ‘humble’ Lied to the perceived grander status of the symphony and opera, and thus were increasingly attracted by larger-scale, more complex variations of the genre such as the song-cycle and orchestral Lied. A significant aesthetic shift was initiated by Hugo Wolf, who reasserted the centrality of the poem, as Gottsched had proposed a century and a half earlier. It was Wolf’s practice to preface the performance of each of his songs with a recitation of the text; although this arguably restored its supremacy, it also put asunder words and music, which in the ablest of hands had fused so seamlessly. Furthermore, in order to give due attention to each inflection of a poem, Wolf’s musical realisations were musically and conceptually extremely demanding. Harmony in the age of Modernism – of which Wolf was an important precursor – also altered the relationship between melody and accompaniment, which had hitherto generally been intuitive and supportive.

The rejection of received musical models by the followers of Richard Wagner also led to a diversification of approaches to the Lied. Gustav Mahler integrated his songs into his symphonies; Arnold Schoenberg used his Lieder for small-scale experiments with radical harmony; and his pupil Hanns Eisler rejected this aesthetic entirely to write Hollywood-style songs in an attempt to reclaim the Lied’s ‘traditional location at the border between the popular and the serious’.58 The lack of a unified view of what the Lied should be served to render it too esoteric and practically complex to retain a place in live private music-making and contemporary popular culture. As jazz and light music took its place there, the development of recording technology offered the Lied a new home. While the Lied continues to live on the recital stage and in the recording studio, the singer-songwriters of the Lied exist no more.

The early history of bluegrass music provides numerous opportunities to examine the tangly issues of song authorship and ownership. Emerging as a sub-genre of country music in the years immediately following World War II, the bluegrass sound and repertoire are rooted in pre-war ‘hillbilly’ music, traditional Anglo-Celtic folk song and tunes, as well as African American blues, jazz, and spirituals. The bluegrass sound found an audience and became a ‘genre’ within the context of a booming post-war commercial country music industry.1 Indeed, the most highly esteemed bluegrass groups, such as Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys, Flatt and Scruggs, and the Stanley Brothers, were established in the late 1940s and 50s. It is during this period that many bluegrass standards were first composed and recorded for commercial release. Bluegrass, then, reaches back into the tradition of anonymously penned, publicly shared folk song, but evolved in a nascent country music industry that peddled publishing contracts and legally determined composition credits.

Focusing on the early career of bluegrass pioneer Bill Monroe, this chapter explores the tensions that emerge between songwriting practice and conventional views of authorship in the commercial music industry. Monroe, the self-proclaimed and widely acknowledged ‘father of bluegrass’, began his professional performing career in the 1930s amidst a quickly evolving recording industry. During this period, underdeveloped and vague copyright legislation enabled industry executives and, in some cases, artists to secure copyright in ways that did not necessarily reflect the songwriting process. Authorship claims were even murkier in the country music industry where artists regularly recorded, ‘arranged’, and/or asserted ownership of a vast repertoire of ‘traditional’ material. While most of Monroe’s songwriting credits are sound, a number of ambiguous or decidedly misleading authorship claims have surfaced.2 In some instances, erroneous credits stem from the politics of ensemble composition and Monroe’s governing position in his ever-changing group, the Blue Grass Boys. More often, however, it appears he was adopting conventional industry practice (e.g., using pseudonyms, purchasing material, et cetera) and attitudes towards songwriting and ownership.3

I begin with a brief biographical profile of Bill Monroe (1911–1996), which is inevitably intertwined with the early histories of both bluegrass and the country music industry. This section provides context for an examination of one of Monroe’s most well-known songs, ‘Uncle Pen’. Through this case study I consider songwriting as a collaborative pursuit while examining the ensemble politics and industry pressures that perpetuate a rigid view of songwriting concerned with individual composers and their works. In addition to providing a profile of one of the most celebrated songwriters in bluegrass and country music, this chapter aims to broaden our understanding of the songwriting process and demonstrate how song authorship is not only determined by creative practice, but is influenced by the mechanisms of the commercial music realm.

Bill Monroe, bluegrass, and the early country music industry

Bill Monroe’s interest in music flourished during his adolescent years. The youngest of eight children, the music he encountered in church, on recordings, and in his small community near Rosine, Kentucky, provided respite from boredom and loneliness.4 He was encouraged by his mother Malissa Vandiver, a multi-instrumentalist with a vast repertoire of old-time tunes and ballads, and was particularly drawn to the fiddle playing of her brother, Pendleton Vandiver. As a teenager, he experimented with his voice, singing old-time songs or ‘hollering’ in a bright, high tenor on the vacant fields of his family farm.5 Monroe was largely a self-taught musician and during these early years he closely observed a number of local musicians, picking up fragments of musical knowledge and sounds that would later form the basis of his own style. Aspiring to perform with his older brothers, Charlie and Birch, he adopted the mandolin as his primary instrument. With a few rudimentary lessons from Hubert Stringfield, one of his father’s farmhands,6 Monroe quickly excelled on the instrument.

Through the 1920s, Bill Monroe began his performance career accompanying, on rhythm guitar, two local musicians who would become major influences on his artistic growth. Shortly after his father died in 1928 (his mother died just six years prior), the teenaged Monroe briefly resided with his Uncle Pendleton (aka Pen), the relative who initially sparked his deep interest in traditional music. Pen, who maintained an extensive repertoire of fiddle tunes, regularly performed at weekend barn dances. Alongside his Uncle Pen, Bill not only acquired paid performance experience, but he also developed a strong sense of rhythm and amassed a collection of tunes that he could transpose to his mandolin.

During these years Monroe also accompanied Arnold Schultz, a local African American blues guitarist and fiddler. Backing Schultz’s fiddle, he clocked in more hours playing all-night barn dances and earned respect as a capable performer.7 Perhaps more valuably, elements of both Schultz’s guitar and fiddle playing seeped into Monroe’s own style. ‘There’s things in my music’, he states, ‘that come from Arnold Schultz – runs that I use a lot in my music’.8 Schultz also galvanised Monroe’s fondness for blues music.9 Indeed, blues-inflected harmonies, rhythm, and phrasing permeate his music and bluegrass in general.10

In 1929 Bill Monroe followed his brothers Charlie and Birch to Chicago where the three found work at an oil refinery.11 While there, the brothers began to take their music in a more professional direction performing as the Monroe Brothers at Chicago area barn dances and on local radio stations. By 1934 Birch departed for a more stable livelihood just as Charlie and Bill secured a regular radio spot on Iowa’s KFNF. Now, sponsored by a patent medicine company called Texas Crystals, the pared-down Monroe Brothers were able to perform music on a full-time basis. Soon after, they would encounter Victor Records Artist and Repertory producer, Eli Oberstein.

In 1933, Oberstein was in charge of relaunching a subsidiary of Victor called Bluebird Records, which specialised in southern blues and country music. Oberstein, like many of his counterparts in the early country music industry, embarked on ‘field trips’ throughout the rural south with the aim of unearthing marketable songs and unexploited talent. Setting up makeshift recording studios throughout the southern United States, he ‘discovered’ and established recording deals with a number of notable early country artists including Ernest Tubb and the Carter Family. In February 1936, while on a field trip to Charlotte, North Carolina, he crossed paths with the Monroe Brothers and promptly made plans to record them. Under Oberstein’s direction, the Monroe Brothers recorded a total of sixty songs for Bluebird, the majority of which consisted of material from established gospel songbooks, commercial country/hillbilly music, as well as a smattering of traditional folk songs, ballads, and popular songs from the African American tradition.12

That the Monroe Brothers’ repertoire drew so heavily on popular, religious, and folk music written by other songwriters, both known and anonymous, is not exceptional. Indeed, those on the ground floor of the commercial country music industry in the 1920s and 30s inherited a vast catalogue of unrecorded music that had circulated between amateur and folk musicians for decades prior. This large stock of pre-composed material provided lucrative, and often questionable, opportunities to release a continual flow of music. Eli Oberstein was particularly notorious for his ability to attain legal control of artists and their music, aggressively hunting artists already signed to contracts, establishing dummy publishing houses, and publishing songs using pseudonyms with most of the royalties directed towards himself.13 Not surprisingly, working with Oberstein, Bill and Charlie did not retain publishing royalties for their Monroe Brothers recordings and made only dismal returns with Bluebird’s sales royalty rate (0.125 cents per side sold).14

While they were not necessarily profitable for the Brothers, the Bluebird singles were a valuable marketing tool that helped them establish a place within the country music industry. Stylistically, the Monroe Brothers represented the ‘brothers duet’ trend that surfaced in the 1930s and included such acts as the Delmore Brothers, the Blue Sky Boys, and Karl and Harty. The brothers duet sound is characterised by close harmony singing. In the Monroe Brothers, Bill built on his early experimentation ‘hollering’ in isolation by harmonising with his brother, working his powerful, high pitches into performance and recording contexts, and incorporating his distinctive voice into the Brothers’ interpretations of stock material. In later years, Bill Monroe’s singing style, commonly described as the ‘high lonesome sound’, would become a defining characteristic of bluegrass music.

Like a number of other brother ensembles, the Monroe Brothers backed their vocal harmonies with guitar (Charlie) and mandolin (Bill). However, as Neil Rosenberg observes, their virtuosic musicianship set them apart. They often performed at a much quicker tempo than their counterparts, giving their music a driving sense of urgency. Furthermore, while Charlie ornamented his rhythm guitar playing with melodic bass runs, Bill chopped percussively on his mandolin and burst into explosive leads.15 In his mandolin solos, Bill aimed to capture all of the nuances of his favourite fiddlers, especially his uncle Pen. He also worked in other influences such as ‘accidental notes and half-tone ornamentations taken from blues guitar’.16 In doing so, he not only developed his own style, but reimagined the mandolin as an exhilarating lead instrument.

The Monroe Brothers recorded their Bluebird singles over the course of six hasty sessions. For the most part, the rapid-fire succession of songs demanded straight reproductions of pre-composed material. At times, however, they used their vigorous and occasionally haunting brothers duet sound to enliven songs they heard in their community, on the radio, or discovered in gospel songbooks. While they did not claim songwriting credits for any of their Bluebird material, the brothers demonstrated compositional skill through their arrangements. For instance, the success of their signature song, ‘What Would You Give in Exchange for Your Soul?’, spawned three sequels, which included alternate lyrics and made slight melodic deviations from their original source, a gospel songbook called Millennial Revival.17 Meanwhile, Bill’s mandolin leads were becoming more exploratory and inventive on songs like ‘Nine Pound Hammer is a Little too Heavy’ and ‘I Am Ready to Go’.18

In 1938, after prolonged sibling tensions came to a head, the Monroe Brothers disbanded. Soon after, Bill Monroe established his first band, the Blue Grass Boys. Looking to distance himself from the sound of the Monroe Brothers, he fused instrumental prowess with a range of musical influences in a small ensemble context. This required musicians that were both capable instrumentalists and could follow direction. In addition to Monroe’s mandolin, the first Blue Grass Boys line-up19 consisted of Cleo Davis (guitar), Art Wooten (fiddle), and Amos Garren (upright bass). By including the fiddle, Monroe created opportunities for new melodic possibilities while tying his musical vision to the fiddle-tune traditions he held in such high regard. Amos Garren’s bass, on the other hand, encouraged a tight rhythmic discipline, which was lacking in the Monroe Brothers.20 Monroe coached each musician, imparting specific runs, licks, and textures inspired by his love of folk tunes, old-time string band music, blues, and jazz.

With all four members sharing the vocal duties, Monroe’s new band also broadened the harmonic scope beyond that of his previous act. Like his instrumental coaching, Monroe facilitated quartet-singing rehearsals in which the band arranged harmony parts for a number of well-known gospel songs. All-male gospel quartets, which sang in close four-part harmony, were popular during the 1920s and 30s. Appearing as the Blue Grass Quartet, Monroe’s group would perform gospel standards, reducing the instrumentation to just guitar and mandolin in order to showcase their vocal harmonies.21 In later years, quartet singing would have a strong presence in the harmonies of secular bluegrass music.

Through the early 1940s Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys achieved a distinctive sound within the country music field. It wasn’t until the second half of that decade, however, that ‘bluegrass’ was solidified as a genre.22 Specifically, the 1946–48 roster demonstrated unparalleled virtuosity, released a string of commercially successful singles, and maintained a popularity that yielded dedicated fans, as well as imitators. This ‘classic’ Blue Grass Boys era included Lester Flatt’s smooth lead vocals and rhythm guitar, was pinned down by Cedric Rainwater’s walking bass lines, and featured exhilarating instrumental breaks from Monroe (mandolin), Chubby Wise (fiddle), and Earl Scruggs (banjo).

Apart from the band’s capability as a cohesive unit, perhaps the most noteworthy contribution during this era was Earl Scruggs’ exceptional banjo playing. Employing his thumb, index, and middle fingers, Scruggs was able to produce continuous, rapid arpeggios that contained complex melodies while propelling the music forward. The sound became known as ‘Scruggs-style’ banjo, and for many fans it is a defining feature of bluegrass music.

By the early 1950s, bluegrass was characterised as a style of music rooted in the ostensible simplicity of folk song and early country, but with a sonic explosiveness and instrumental mastery more reminiscent of bebop. Bluegrass, Alan Lomax famously reported, is ‘folk music in overdrive’.23 While each Blue Grass Boy brought their unquestionable talents to the group, and many contributed to the genre in the decades following, bluegrass is ultimately a realisation of Bill Monroe’s musical vision. The Blue Grass Boys became a space where he could creatively assemble his musical influences. What’s more, utilising the resources of a highly skilled band, Monroe was able to earnestly demonstrate his proficiency as a songwriter and arranger. Over the course of his career with the Blue Grass Boys, he composed or co-composed a number of bluegrass and country standards such as ‘Kentucky Waltz’, ‘Blue Moon of Kentucky’, ‘Can’t You Hear Me Callin’’, and ‘Uncle Pen’.

While Monroe’s contributions to the popular music canon are now widely recognised,24 his legacy has been dogged by questions regarding the legitimacy of his songwriting credits. These uncertainties emerged from three main philosophical and ethical discussions surrounding creative influence, the songwriting process within an ensemble setting, and the mechanisms of the early country music industry. The remainder of this chapter explores issues of composition, authorship, and ownership focusing on one of Monroe’s most well-known songs, ‘Uncle Pen’. The song is noteworthy for how it reflects Monroe’s biography and influences, was composed collaboratively, and highlights some of the complexities that emerge when establishing authorship in the commercial music realm.

‘Uncle Pen’: authorship, ownership, and collaborative composition

While it is difficult to pin down exactly when ‘Uncle Pen’ was composed, accounts from former Blue Grass Boys indicate that the song emerged around 1949–50.25 It was first recorded for Decca Records on 15 October 1950. In the decades following, ‘Uncle Pen’ would become one of Monroe’s signature compositions, featured regularly in his live shows, sprinkled throughout his recorded output, and performed innumerable times by both professional and amateur bluegrass groups. What’s more, Monroe’s Uncle Pendleton Vandiver (d. 1932), for whom the song is a tribute, would emerge as a key presence in the artist’s biography and the broader narrative of bluegrass music. Indeed, for fans and followers of Monroe, especially those within the 1960s urban folk revival, Uncle Pen, the person, became something of a mythical figure – a repository of obscure Irish and Scottish fiddle tunes, a catalyst of bluegrass’ driving rhythm, an emblem of and musical link to some notion of pre-modern, pre-commercial ‘authenticity’.

Meanwhile, ‘Uncle Pen’, the song, has emerged as an archetypal bluegrass composition. As David Gates observes, recounting the life of ‘an old fiddler and the tunes he used to play’, the song imparts an anxiety ‘that the old ways of life, and the music that went with them, are vanishing’.26 This is certainly reflected in Monroe’s nostalgic lyrics, which offer a bucolic image of Pen’s fiddle resounding through the countryside, drawing the townspeople together. In an allegorical move alluding to the anxieties observed by Gates, the final verse laments the death of Uncle Pen and the silence that comes over the community.

Like many bluegrass songs, ‘Uncle Pen’s’ lyrics convey nostalgia for a pre-modern sense of community and a view of traditional music as part of the social fabric of rural America. This is tied to notions of collective music-making, which the bluegrass ensemble epitomises and celebrates. Within bluegrass discourse there is an emphasis on the collective; the constituent parts coming together as one unit, listening and responding to one another in order to create a tight, cohesive musical entity. Indeed, the bluegrass sound relies on interlocking rhythms, vocal blending, and subtle shifts in the instrumental balance.

Within this collective music-making environment, songs are often composed as group members exchange and build upon each other’s musical ideas. Such was the case with ‘Uncle Pen’. The first recording of the song features, in addition to Monroe, Jimmy Martin (guitar, vocals), Merle ‘Red’ Taylor (fiddle), Rudy Lyle (banjo), and Joel Price (bass, vocals). There are slightly divergent accounts of who exactly produced the initial spark for the song, though most agree it started with Monroe and Red Taylor.27 All agree that ‘Uncle Pen’ was a group effort and, indeed, the first recording bears the stylistic mark of each performer.

Rudy Lyle recalls that Monroe first begin composing the song ‘in the back seat of the car … on the way to Rising Sun, Maryland’.28 This scenario is likely given the numerous accounts of Monroe picking his mandolin and devising lyrical fragments while on the road between performances.29 Sometimes the musicians surrounding Monroe would latch on to and experiment with one of his musical ideas.30 Alternatively, he might approach particular Blue Grass Boys with a basic melody or single verse in the hopes that they might help develop it into a complete song. According to Merle ‘Red’ Taylor, this is precisely how the framework for ‘Uncle Pen’ was initially sketched out. While resting at a hotel near Danville, Virginia, Monroe came to Taylor’s room with a few ideas for a song about his uncle Pendleton Vandiver. Monroe directed his fiddler to come up with a melody that would mimic the ‘old-timey sound’ of Pen’s fiddling. After spending some time working on his own, Taylor emerged with a fiddle melody that pleased Monroe and became the song’s primary instrumental hook. ‘Bill wrote the lyrics for “Uncle Pen”’, Taylor recalls, ‘and I wrote the fiddle part of it’.31

Two other contributions also stand out in the performance and arrangement of ‘Uncle Pen’. Firstly, as Rosenberg and Wolfe note, Monroe, Jimmy Martin, and Joel Price’s three-part harmony on the song’s chorus was uncommon in the group’s Blue Grass Boy repertoire during this time.32 They were, however, accustomed to singing harmony during their gospel quartet features, and if Monroe did not specifically direct his singers, it is likely that they were experimenting with the stylistic conventions of gospel harmony in arranging the song’s chorus. The second contribution is Jimmy Martin’s guitar run, which caps off the final a cappella moments of the song’s chorus while providing an elasticity that propels the reintroduction of Taylor’s fiddle melody. The lick strongly resembles what is now referred to as the ‘(Lester) Flatt run’ and has become a stylistic marker of bluegrass guitar.