INTRODUCTION

Recognizing that the consequences of political repression can persist long after the repressive regimes themselves, scholars have turned renewed attention to the study of historical episodes of repression.Footnote 1 Most of those studies rely on cross-national analyses to determine the conditions under which governments adopt repressive measures against citizens (Davenport Reference Davenport1996; Harff Reference Harff2003; Krain Reference Krain1997; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Huth and Balch-Lindsay2004), principally noting that autocracies are more likely to impose violent repression than democracies.Footnote 2 Recently, however, a growing number of studies have begun to examine the distribution of repression within countries using subnational data (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006; Charnysh and Finkel Reference Charnysh and Finkel2017). These studies often recognize that populations within countries can have heterogeneous experiences with violent repression, and thus that the long-term effects of repression can also vary.

Despite these advances, few of the existing studies, including those with a sub-national focus, have considered the long-term political effects of political repression. This has obscured our understanding of the enduring influences of violent repression, particularly in terms of how it may have shaped historical social cleavages and affected citizens’ political attitudes and behavior.Footnote 3 Employing novel data and advanced research designs, recent studies have endeavored to examine the persistent effects of past violent events on citizens’ political and social perceptions. These studies examine the effects of past political repression on political attitudes by studying, inter alia, the influence of anti-Jewish policy on the current culture and politics in Europe (Grosfeld, Rodnyansky, and Zhuravskaya Reference Grosfeld, Rodnyansky and Zhuravskaya2013; Charnysh and Finkel Reference Charnysh and Finkel2017), the political identities and behavior in democratized Spain after decades-long authoritarian ruling and civil war (Balcells Reference Balcells2012; Rodon 2018), the current levels of distrust toward the South Korean government in previously violence-ridden districts during the Korean War (Hong and Kang Reference Hong and Kang2017), and social and political distrust that arose from the Cultural Revolution in China (Wang Reference Wang2021).

Our study aims to expand the literature not only by exploring the effects of political violence on contemporary political behavior but also by examining how the effects vary over decades of democratization. Focusing on political violence in the context of Taiwan, a country that has achieved stunning economic success and a peaceful democratic transition over the past half-century, this article constitutes one of the recent attempts to investigate how violent repression may affect constituents’ political behavior and attitudes in the long run. Employing survey data collected periodically over the last three decades, we demonstrate the long-term effects of Taiwan's February 28 Incident on voting behavior and political attitudes related to Taiwan's primary social cleavage.

Three studies have recently, and concurrently, contributed to identifying the persistent effects of state repression. Rozenas, Schutte, and Zhukov (Reference Rozenas, Schutte and Zhukov2017) find that Stalin's forced deportation of residents in western Ukraine to Siberia in the 1940s reduced electoral support for pro-Russian political parties in contemporary elections in the victimized region. In the same country, Rozenas and Zhukov (Reference Rozenas and Zhukov2019) found that Stalin's coercive agricultural policy in the 1930s have had a long-term effect on anti-Russia attitude in famine-ridden communities. Studying the deportation of Crimean Tatars in 1944, Lupu and Peisakhin (Reference Lupu and Peisakhin2017) demonstrate that families transmit the traumatic effects of the deportation to their offspring, thereby affecting political identities, attitudes, and behaviors across generations. While the outcomes of those two studies’ also address political behavior, a key difference is that, in the case of Taiwan, the perpetrator of violence continued to govern the country for decades after the incident. This implies that it might be more difficult to detect the long-term effects in our study, as the perpetrator may have adopted various measures to dilute or eliminate any negative effects in order to avoid long-term political disadvantages. Furthermore, a unique feature of this study is that we explore multiple mechanisms through which the long-term effects have persisted and which may explain how the effects have changed over the three decades since democratization, during which time reconciliation has been pursued.

Taiwan's 228 Incident occurred on February 28, 1947, following street protests against the Chinese government and its leading Kuomintang Party (KMT). The protests resulted in draconian repression by the KMT army; estimated deaths range from 10,000 to 30,000 (Fleischauer Reference Fleischauer2007; Horton Reference Horton2017).Footnote 4 Despite the critical role of the Incident in Taiwan's subsequent political development, existing studies have not explored or assessed its long-term political impact.Footnote 5 Meanwhile, numerous questions remain unanswered: How does a population exposed to such severe government-led violence differ from subsequent generations? Did the subsequent 40-year rule of KMT drive citizens to assimilate, or have they remained traumatized? How have the democratic transition and reconciliation processes influenced those effects?

To address these questions, we build a dataset of victims from the Incident in each township who received compensation, or whose families received compensation, from the government between 1995 and 2015.Footnote 6 We combine those data with three sets of contemporary surveys in Taiwan, which were conducted periodically from 1990 to 2017. While testing the location-based mechanism, which is the primary channel examined by most of the above-mentioned studies on the historical persistence of state-sponsored violence, our study additionally explores a mechanism whereby the generation sharing the traumatic experience, through either direct or indirect exposure, exhibits a unique pattern in political attitudes or behavior today. The effect is conceivable in this context, given that the casualties occurred throughout the entire island.

Our analyses show that the generation that experienced the February 28 Incident, and the people who live in towns that suffered more collective casualties as a result of the Incident, hold different political attitudes compared to other constituents. In addition, we find that the generation that experienced the Incident is less supportive of the KMT in presidential elections. Geographic effects are particularly pronounced in historical urban districts, where the Incident's victims were heavily concentrated, regarding presidential elections as well as national identity. Despite democratization and reconciliation efforts, generational effects have generally increased since 2000, with geographic effects remaining constant or decreasing.

THE FEBRUARY 28 INCIDENT

Taiwan, historically known as Formosa, remained solely populated by its indigenous inhabitants until the early seventeenth century, when foreign forces such as the Dutch East India Company first began to systematically colonize the island. By the late 1600s, control of Taiwan fell under the Qing Empire, which maintained control of the island until 1895, when Japan launched its own colonization of the island that lasted until the end of the Second World War. One month after the surrender of Japan in 1945, Taiwan was placed under the Chinese Nationalist government (KMT) control, with General Yi Chen appointed as the Governor.

Governor Chen's leadership contributed to the worsening of Taiwanese living conditions after the war. Many commodities, such as rice, were shipped to the Mainland to support the KMT's civil war against the Chinese communists, and Chen's policies and governance more generally resulted in serious food shortages, high inflation, and unemployment on the island (Stead Reference Stead1946). The prevalence of political corruption, which had been relatively rare during Japanese colonial rule, undermined the rule of law, generating widespread discontent and resentment among the Taiwanese population (Stead Reference Stead1946; Phillips Reference Phillips and Rubinstein1999).

On the evening of February 27, 1947, an enforcement team from the Tobacco Monopoly Bureau accompanied by four policemen confiscated the cigarettes and cash of a street vendor illegally selling cigarettes on a busy street in Taipei. When the vender begged for her cash to be returned, a member of the enforcement team struck her head with a pistol, causing her to fall to the ground. While this type of brutal treatment had become common during the years following the arrival of the Chinese administration, this particular incident triggered the anger of Taiwanese onlookers, who formed a hostile circle around the government agents, challenging their actions. As the agents fled the scene, running into the nearby police station, a shot was fired into the crowd, killing a bystander. This further ignited the fury of the Taiwanese crowd, already deeply frustrated with Chen's administration. The protesters sieged the police station, demanding that the agents be handed over (Durdin Reference Durdin1947a; Lai, Myers, and Wei Reference Lai, Myers and Wei1991). Their request was ignored.

On the morning of February 28, an angry mob gathered in front of the Taipei Branch of the Tobacco Monopoly Bureau. Military police fired into the crowd with machine guns from the roof of the office, causing some casualties and triggering riots throughout the city. The situation escalated beyond control when soldiers and police continued to open fire on civilians to quell the riots. Violent clashes between the Taiwanese people and government officials over the control of public infrastructure spread throughout the entire island and continued during the following days. As the events unfolded, local representatives and elites formed settlement committees throughout the island to maintain public order, and they met with Governor Chen to advocate political reforms to address corruption and increase self-governance.

While negotiating with Taiwanese elites, Governor Chen seems to have secretly requested reinforcements from the KMT central government (Durdin Reference Durdin1947c). Landing in the northern and southern ports of Taiwan on the evening of March 8, the KMT government launched an island-wide crackdown over the following week. Immediately following the crackdown, the KMT government initiated a massive purge that targeted Taiwanese elites (Phillips Reference Phillips and Rubinstein1999). Governor Chen jailed or ordered the execution of individuals who had participated in the settlement committees or who were perceived to have ever promoted greater self-governance or criticized the KMT leadership (Durdin Reference Durdin1947c). The number of deaths in 1947 was estimated to be between 18,000 and 28,000, according to a government report released by the KMT government in 1992 (The February 28 Incident Research Report, 1992), but the exact number remains unknown.

Following the Incident, a hunt for Taiwan's citizens who had considered being involved during the Incident or resisting the KMT regime on the island persisted for four decades, a phenomenon known as Taiwan's “White Terror.” The February 28 Incident became a social and political taboo until the late 1980s, when democratic pressures emerged and martial law was lifted (Fleischauer Reference Fleischauer2007). Taiwan's first popular election for all of its legislative seats, a political milestone, was held in 1992, followed by a presidential election in 1996. The liberalization of Taiwan's political landscape not only provided a voice to the opposition for the first time, but it also ushered in the beginning of a national dialogue regarding the February 28th Incident.

THEORETICAL EXPECTATIONS

The Incident has been a focal point of Taiwanese politics since the beginning of its democratization process. Following public pressure, the KMT government released the first official report on the February 28 Incident in 1992. Then-President Lee Deng-Hui offered a formal apology and mobilized his party to pass a law in 1995 to provide compensation to the victims of the Incident and their families. In 1997, the law was revised to establish February 28th as Taiwan's Peace Memorial Day (Chen Reference Chen2008). While these actions are perceived by some as having tempered the importance of the issue in the context of increasing political competition, the Incident has been subject to new discourses in the 2000s, with commemorative ceremonies held every year, including events organized by the two major parties and joined by millions of Taiwan's citizens 18 days before the 2004 presidential election. If the Incident did not have any long-term effects, it would be difficult to rationalize these political actions.

Yet, in contrast to fairly widespread political and public attention, the effects of the Incident have received relatively scant attention from researchers. After democratization, studies of the Incident—which to that point had been banned—were pursued primarily by historians, who have focused primarily on improving the understanding of the historical, social, and political environment surrounding the event. Some recent studies, such as Fleischauer (Reference Fleischauer2007), Shih and Chen (Reference Shih and Chen2010), and Hou (Reference Hou2011), have exploited qualitative data to evaluate the role of ethnic identity in the Incident and how the Incident may have incited ethnic conflict between the Taiwanese and Mainlanders.Footnote 7 Despite these strides, assessments on the impacts of the Incident and its role within the society remain fairly limited.

Given the critical role the Incident played in Taiwan's political developments, we hypothesize that the it may have impacted political attitudes and behavior through two channels: a geographic one and a generational one. The geographic channel focuses on how the Incident's damage to a town affects the political behavior or attitudes of its residents half a century later. More casualties in a town mean that a resident of that town would be more likely to have either experienced the KMT's crackdown or to have relatives, friends, or neighbors who experienced or witnessed the violence. With democratization in the late 1980s, the media, a number of political movements, and some academic research broke the taboo on coverage of the incident, emphasizing the tragic nature of the events and seeking to recover collective memories about it that had been suppressed.Footnote 8 Hence, we expect that voters from more heavily damaged townships collectively are more likely to hold a more negative political view toward the KMT after democratization, compared to those with less significant atrocities.

It is important to note that political preference for the KMT did not appear to vary across regions or areas before the Incident. While it is impossible to obtain any quantitative data or qualitative information on public opinions related to KMT popularity in the 1940s, previous studies on the Incident and on Taiwan's political history have not mentioned or hinted at any difference across regions or between historically urban and rural areas in support for the KMT.Footnote 9 As historians have documented, using newspaper evidence published before the Incident, many Taiwanese cheerfully stood in the streets throughout the island to welcome the arrival of the KMT army after Japan surrendered in August of 1945. Between their arrival and the Incident (i.e., from October of 1945 to February of 1947), the KMT's corruption and unpopular economic, linguistic, and social policies affected nearly all Taiwanese people indiscriminately, promptly leading to an island-wide riot immediately after the conflict in Taipei. Therefore, it is unlikely that a large number of casualties in a town were driven by town-specific hostility toward the KMT that had existed before the Incident and persisted afterward.Footnote 10

Instead, according to historical accounts, the KMT army appears to have chosen its crackdown strategy largely for reasons of effectiveness. When the KMT's reinforcements landed in Taiwan's two major ports at Keelung and Kaohsiung cities eight days after the Incident, they quickly took control of the island by indiscriminately shooting people in the streets, particularly in major cities, for three days (Durdin Reference Durdin1947a, Reference Durdin1947b). Taiwan's major cities in 1947 included Keelung, Kaohsiung, Taipei, Chia-Yi, Sing-Zu, Taichung, and Tainan.Footnote 11 Once the riots in these cities were suppressed, the island was largely under the KMT's control. Based on our data, the average rate of identified victims in these major cities is much higher than in other places, with substantial variance across towns within these cities.Footnote 12

This discussion of the KMT's crackdown strategy has two implications. First, the casualty distribution has little or nothing to do with political preferences for or against the KMT that existed when the Incident occurred. Second, the Incident likely left a deeper scar in the major cities, especially in their violence-ridden towns. Indiscriminate shootings happened more frequently in these major cities and may have left those who witnessed such violence traumatized. In fact, many of those who were arrested in the weeks following the Incident were publicly executed in front of these cities’ main stations. This suggests that in the major cities, more time may have been required to heal and more pronounced long-term geographic effects may have followed from the Incident. To investigate this possibility, we treat the seven major cities as our key subsample in additional analyses.Footnote 13

The other channel we examine is generational. We hypothesize that specific generations witnessing or experiencing the February 28 Incident would be less supportive of the KMT. Through socialization after a critical event, cohorts often share political attitudes related to a past event (Neundorf, Gerschewski, and Olar Reference Neundorf, Gerschewski and Olar2020). As most Mainlanders had not moved to Taiwan until 1949, non-Mainlander populations born before 1947 were the primary cohorts exposed to the traumatizing experience during and in the aftermath of the Incident. We predict that these generations, particularly the cohorts who had reached at least school age when the Incident took place (Bartels and Jackman Reference Bartels and Jackman2014), will collectively show more negative political attitudes and voting behavior toward the KMT, as they were most negatively affected by the violence.Footnote 14 Although the intergenerational transmission of the trauma would reduce the relative impact of the generational effect, the latter would still exist as long as the effect is not fully transmitted across generations.

A potential difficulty in identifying the generational effect is that the generations exposed to the Incident may also have shared other distinctive experiences that took place before or after the Incident.Footnote 15 Colonial occupation by the Japanese government from 1895 to 1945 is the major political development before the Incident. However, as mentioned, existing historical studies all suggest that the Taiwanese of the time held quite favorable views of the KMT when it arrived at the end of 1945, about one year and two months before the Incident occurred. Given that the Incident is generally considered the event with the widest, deepest, and most consequential impact on Taiwan's subsequent political development after the KMT arrived, it would be inconceivable to preclude the Incident as a principal reason for the transformation of views of these generations toward the KMT. After the Incident, the major, island-wide political event is Taiwan's “White Terror,” which was triggered by the Incident and lasted through subsequent decades until democratization. The repressive measures taken by the KMT-led government which spurred White Terror, as well as some small-scale events occurring in the 1970s, presumably have impacted both the generations experiencing the Incident and those born after it, and therefore may have mitigated the Incident's effect. The effects we estimate in the following section are possibly the lower boundary of the true effects of the Incident.

We will examine the long-term effects on vote choices and political attitudes over time, as detailed in the next section. We expect the long-term effects to be more salient regarding political attitudes than vote choices because the latter can be affected by electoral campaign measures of candidates and their other attributes (e.g., personal valence or charisma). We are also theoretically interested in how reconciliation following democratization might have shaped the long-term effects of the Incident, an issue that has not been addressed in the literature.

EMPIRICAL STRATEGY

To assess the long-term effects of the Incident on citizens’ support for the KMT in national elections and its key policies, we employ three dependent variables. The first and second dependent variables are national identity and ethnic identity, the former of which has been considered the most critical social cleavages in Taiwan since the early 1990s (Hsieh Reference Hsieh2004, Reference Hsieh2005). National identity is determined based on the respondents’ support for independence or unification. Among the two major political parties, the KMT has been leaning toward eventually unifying with Mainland China, while the DPP has been strongly in favor of building a new nation. The variable is coded 1 if the respondent supports independence (i.e., establishing a new nation), 2 if the respondent supports the maintenance of the status quo (i.e., maintaining Taiwan's current national title and constitution), and 3 if the respondent favors unification with the People's Republic of China (PRC). Our dataset shows that 21.3% of respondents in the dataset support independence, 58.5% favor the status quo, and 20.2% support unification.Footnote 16 Ethnic identity measures whether a respondent identifies him- or herself as Chinese, Taiwanese or some combination of the two. We code ethnic identity in descending order from those identifying themselves as Chinese, which is closest to what the KMT has endorsed in the past; thus, Taiwanese is coded as 1, Chinese and Taiwanese and Taiwanese and Chinese as 2, and Chinese as 3.

Our final dependent variable is whether a survey respondent cast his/her vote for a candidate from the KMT or other Pan-blue parties in the previous presidential election.Footnote 17 Pan-blue parties consist of the KMT, the New Party (CNP), the People First Party (PFP), and Minkuotang (MKT), supporting a Chinese nationalist identity.Footnote 18 Presidential elections in Taiwan have been held every four years since 1996. We code voting choice as 1 if the respondent answered that he or she voted for KMT or a Pan-blue candidate in the previous election.

We rely on three survey datasets covering different periods for these three dependent variables. The first is the Taiwan Social Change Survey (TSCS), collected by Academia Sinica since 1985.Footnote 19 The surveys that explicitly pose political questions have been conducted thus far in 1985, 1990, 1992, 1993, 1995, 1998, 2000, and 2010.Footnote 20 The second set of surveys was collected by several scholars affiliated with the Election Study Center of National Cheng Chi University, which covered elections in the 1990s. We have combined its data on two presidential elections (1996, 2000).Footnote 21 The third set of survey data comes from Taiwan's Election and Democratization Study (TEDS) spanning 2002 to 2017.Footnote 22 The merging of datasets for this analysis constitutes, as far as we know, the longest timespan of data for studying the long-term trends in political behavior and national identity among Taiwan's constituents.Footnote 23

Our primary independent variables capture the victimization arising from the February 28 Incident through geographic and generational channels. Investigating the geographic channel requires information about the number of victims within each town in 1947. As the exact number of victims in the aftermath of the February 28 Incident remains unknown, we rely on the two victim sources that are the most reliable and systematic with regard to the Incident.Footnote 24 The first and main source consists of a directory of victims published by the 228 Memorial Foundation. The second source of data is the February 28th Data Books, published by Academia Sinica's Institute of Modern History.Footnote 25 The Data Books provide information on victims who were not included in the 228 Memorial Directory.

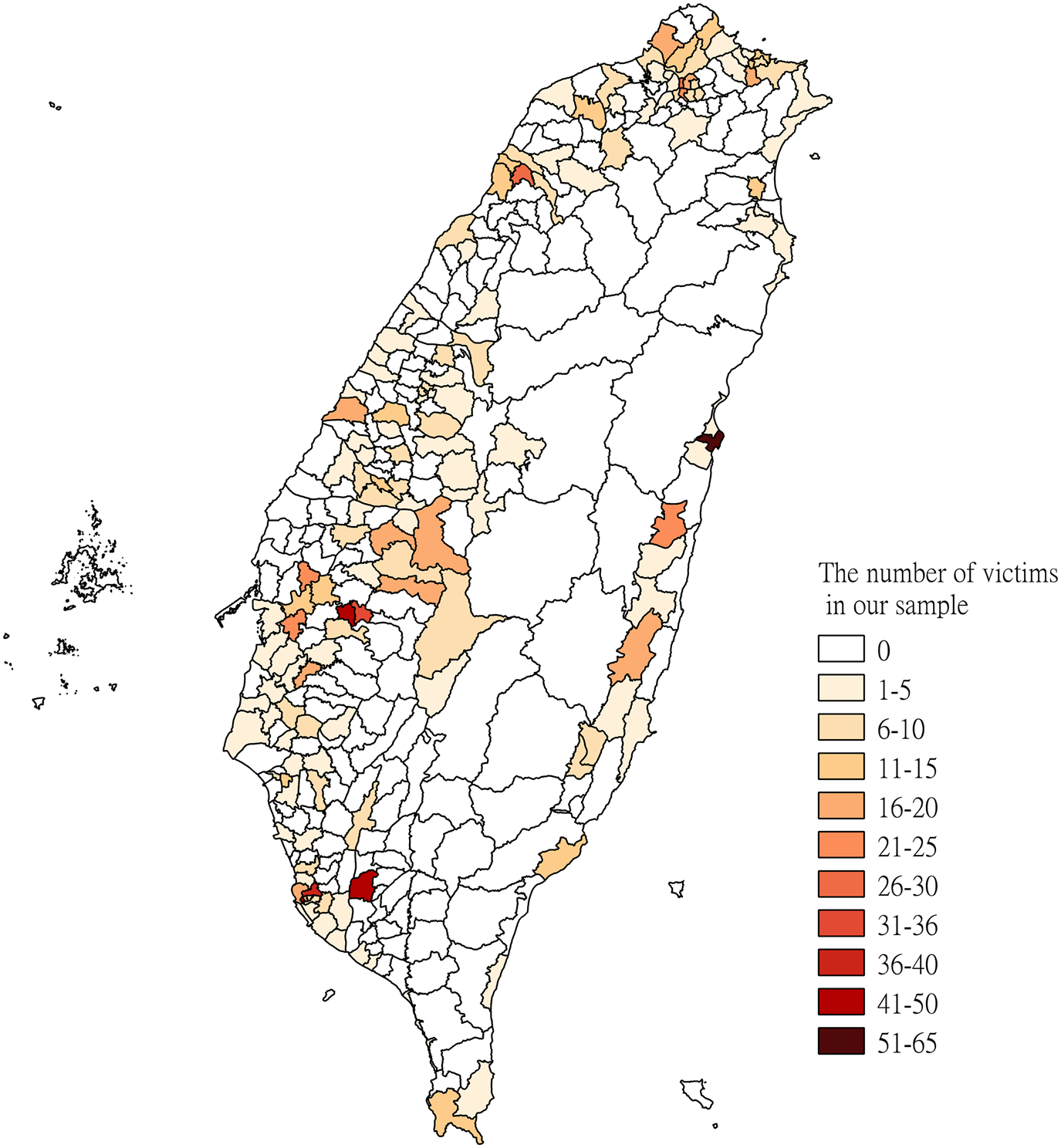

Through extensive efforts to match township information with the identified victims, we were able to compile a dataset of 1,424 cases, each of which includes township information and counts the number of identified victims for each town, as displayed in Figure 1.Footnote 26 This figure shows that the casualties were located all over the island and were somewhat concentrated in some districts of major cities. This pattern is largely consistent with what has been described in existing historical studies (e.g., The February 28 Incident Research Report that the government published in 1992), demonstrating face validity of this sample.

Figure 1 Geographic Distribution of the February 28 Victims

To construct our explanatory variable for the geographic channel, township victimization, we first divided the number of victims within each town in our sample by its population in 1956, the earliest systematic population information available, and multiplied by 1,000 in order to obtain the share of identified victims during the February 28 Incident. Finally, we matched each respondent's township information with the rate of identified victims in that respondent's town.

The other mechanism we examine is the experienced generational one, which we estimate by analyzing distinctive political attitudes and behaviors of the segment of the non-Mainlander population born before 1941.Footnote 27 Those who were under 7 years old when the Incident took place are considered too young to have clear memories about the Incident. Our results remain qualitatively similar when we treat non-Mainlanders born between 1941 and 1950 as one of the experienced cohorts. To understand how the age of the subject during the experience shapes long-term political attitudes toward the responsible party in Taiwan, we divided Taiwan's population into the following five groups: Mainlanders, non-Mainlanders born in or before 1920 (labeled as “experience before1920”), non-Mainlanders born between 1921 and 1930 (“experience born192130”), non-Mainlanders born between 1931 and 1940 (“experience born193140”), and non-Mainlanders born after 1940. We include the first four groups as our independent variables, leaving non-Mainlanders born after 1940 as our reference group in all regression analyses.Footnote 28

Estimating the experienced generation effect may require some caution. A person's political attitudes and behavior at any point reflect the person's age (life cycle effect), the timing of the survey (period effect), and generation (cohort effect), as assumed in the framework of an age-period-cohort (APC) model (Glenn Reference Glenn1976; Yang and Land Reference Yang and Land2006; Smets and Neundorf Reference Smets and Neundorf2014; Huang Reference Huang2019). Therefore, to identify the generational or cohort effect, that is, the effect of an event on a particular generation differing from the effect on other generations, it is necessary to disentangle it from the confounding age and period effects.Footnote 29 While we are interested in the effects of experience shared widely across a cohort, our empirical question is not exactly in line with the APC model where an entire cohort is assumed to share a common experience. In our case, only the non-Mainlander population experienced the Incident directly or indirectly and have shared the experience. Nonetheless, to control potential confounding effects, we include age, its squared term, and a dummy variable for each survey year in our primary regression models. Moreover, to address potential identification problem among these three colinear time trends, we later use the hierarchical age-period-cohort (HAPC) model suggested by very recent APC studies as the first robustness check.

In addition to these key independent variables, we control for a number of factors that are likely to affect political behavior and attitudes. Our control variables include the respondent's gender (male = 1), education level (less than primary = 1, middle school = 2, high school = 3, junior college = 4, university and post-graduate = 5), marital status (married = 1), and ethnicity: (Hakka = 1).Footnote 30 All variables are described in Table A.1 in the Online Appendix.Footnote 31 Lastly, we employ ordered probit and logit models for national and ethnic identities and electoral outcomes, respectively.Footnote 32 Robust standard errors are clustered at the township level.

EMPIRICAL FINDINGS

The first three subsections of this section examine how the experience of the traumatic incident affects constituents’ crucial political attitudes such as national identity and ethnic identity and vote choices in presidential elections in Taiwan. After discussing the effects across decades, we explore several robustness checks.

NATIONAL IDENTITY

As discussed in the previous section, several recent political science studies have provided empirical evidence supporting the long-term impact of political violence on political attitudes in different contexts. The contentious issue of defining Taiwan's “national identity” has persisted as the most salient social cleavage shaping political developments and vote choices on the island since democratization in the early 1990s, and it has been widely studied over that period (Hsieh and Niou Reference Hsieh and Niou1996; Lin, Chu, and Hinich Reference Lin, Chu and Hinich1996; Chang and Wang Reference Chang and Wang2005; Hsieh Reference Hsieh2004, Reference Hsieh2005; Ho, Weng, and Clarke Reference Ho, Weng and Clarke2015; Huang Reference Huang2019). Using the data spanning the 30 years between the 1990s and the late 2010s, this study contributes to the literature by showing the effects of historical political repression in forming a national identity. More critically, given that national identity constitutes the most conspicuous social cleavage in democratized Taiwan, our analysis suggests how the Incident has affected constituents’ electoral behavior by shifting the national identities of victimized generations and residents.

Table 1 presents the analyses for national identity. The results show that the respondents’ experience with the February 28 Incident significantly affects whether they support building a new nation, maintaining the status quo, or unifying with the mainland. Cohorts born in Taiwan before the Incident are less likely to support unification, which has stood as one of the key political slogans of the KMT since its arrival in Taiwan. In other words, those Taiwan-born residents who experienced the Incident are more likely to support building a new nation, which is, conversely, a long held DPP slogan. In all analyses, the reference group is non-Mainlanders born after 1940. The effects are strongest among those who were young adults (age 17–26) and remember the event clearly, followed by those born in the 1930s (7 to 16 years old when the Incident occurred). The effects become smaller but do not disappear among the younger cohort. The average marginal effect of each cohort illustrated in Figure A.1 also confirms a strong generational effect among the cohorts who experienced the Incident.Footnote 33 Average marginal effect estimation indicates that Taiwanese born in the 1920s are, on average, 9.5 percent less likely to support unification, while those born in the 1930s are 7.4 percent less likely to do so, on average.

Table 1 The Effect of the February 28 Incident on National Identity (1990–2017)

Note: The reference group is non-Mainlanders born after 1940. Variables not shown are survey-year fixed effects. Robust standard errors clustered at the township level in parentheses.

+ p < 0.10, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

To explore the effects over the last few decades after democratization, we divide the research period into three time blocks and re-examine the specifications from Column (1): the 1990s (1990–1999) in Column (2), the 2000s (2000–2009) in Column (3), and the 2010s (2010–2017) in Column (4). In general, we find that the negative cohort effects are most apparent in the 2000s, whereas in the 1990s and the 2010s, the effects among the birth cohorts of the 1920s or before seem to dissipate or get smaller. The effects among the 1930s birth cohort remain significant and increasing throughout the periods.

More importantly, we find clear evidence that respondents from heavily victimized townships during the February 28 Incident were much more likely to support building a new nation and to oppose unification with the PRC. The geographic effect is negative and significant in Column (1). We plot the marginal effects in Figure A.2 in the Online Appendix. It shows that township victimization has a positive association with supporting new nation-building and is negatively correlated with endorsing unification: all else equal, increasing township victimization by one unit raises the probability of supporting building a new nation on average by 2 percent and decreases the probability of supporting unification on average by 2 percent (Figure A.2).Footnote 34

We further analyze whether respondents’ national identity differed in the historically urban districts, where the Incident left a larger number of victims compared to other parts of the island (Column (1), Table 2).Footnote 35 We find that the geographic effect of the Incident exists clearly and consistently across all periods among the seven cities that had been distinctive urban districts since 1947. In rural areas, we find no geographic effect of severely victimized townships regarding national identity (Table A.9 in the Online Appendix).Footnote 36

Table 2 The Effect of the February 28 Incident in Historically Urban Districts (1990–2017)

Note: The reference group is non-Mainlanders born after 1940. The estimates of age, age2, Mainlander, Hakka, male, education, and married are not reported. Robust standard errors clustered at the township level in parentheses. The full table is available in the Online Appendix as Table A.3.

+ p < 0.10, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Estimates of the control variables for individual socio-economic features and identity variables are broadly consistent with the findings from previous election studies in Taiwan. Regarding the age effect, we find a curvilinear relationship before 2010. During this period, the effect of age follows a U-shape as the squared term is positive while the single term is negative. This finding indicates that, for this period, young and old voters tend to support unification while middle-aged voters are more likely to avoid it. However, after 2010, younger voters tend to be against unification. Mainlander, Hakka ethnicity, and educated respondents are more likely to be unification supporters. Male respondents are more likely to support independence.

ETHNIC IDENTITY

Ethnic identity is another critical avenue through which the Incident may have shaped Taiwanese voters’ political attitudes. Many studies have noted that one of the key issues dividing Taiwanese society is whether people ethnically identify themselves as Chinese as opposed to Taiwanese (Hsieh and Niou Reference Hsieh and Niou1996; Lin, Chu, and Hinich Reference Lin, Chu and Hinich1996; Chang and Wang Reference Chang and Wang2005; Hsieh Reference Hsieh2005; Ho, Weng, and Clarke Reference Ho, Weng and Clarke2015). Generally speaking, Taiwan's population has shown a shift in ethnic identity, with more respondents identifying themselves as Taiwanese or both Taiwanese and Chinese, rather than Chinese only, in more recent periods. Yet, significant variation exists among the population regarding their self-selected ethnic identity, which substantially affects citizens’ voting behavior.

In Table 3, we examine whether experiences with the Incident affect the ethnic identity of respondents. The results of the experienced generational effects are similar to those we find for national identity. Non-Mainlanders born before the Incident tend to identify themselves as Taiwanese rather than Chinese, the very identity that the KMT has emphasized throughout its administration. This cohort effect suggests a strong impact from the Incident, and it does not dissipate over time. Figure A.1 illustrates the average marginal effects of each cohort. The size of the effect is noticeable: Cohorts born before the 1920s are, on average, 30 percent more likely to identify as Taiwanese and 12 percent less likely to identify as Chinese. The respective figures drop to 20 percent and 8 percent for the 1920s-born cohort, and they further decline among subsequent cohorts, but the significance does not disappear. Clearly, the effects on ethnic identity are much more pronounced than those on national identity. Another difference between ethnic and national identity is that the effect on ethnic identity is the largest among non-Mainlanders born before 1921, compared with the other experienced cohorts, while those born between 1931 and 1940 stand as the most affected group in national identity analyses. A clear difference we notice from the analysis of national identity is that the geographic effect is negative but statistically insignificant in the analysis of ethnic identity. The geographic effect is also insignificant in our subsample analysis of historical urban districts (Column (2), Table 2). Other control variables have effects similar to the previous national identity analysis (Table A.4). Mainlander and Hakka identity, higher education, and being male are correlated with Chinese ethnic identity. The age effect is inconclusive in estimating ethnic identity.

Table 3 The Effect of the February 28 Incident on Ethnic Identity (1990–2017)

Note: The reference group is non-Mainlanders born after 1940. The estimates of age, age2, Mainlander, Hakka, male, education, and married are not reported here, but the full table is available in the Online Appendix as Table A.4. Robust standard errors clustered at the township level in parentheses.

+ p < 0.10, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS

Our empirical findings on the long-term effects of the Incident on voting choice in presidential elections are presented in Table 4. We find evidence supporting our experienced generation hypothesis in presidential elections in Column (1): non-Mainlander residents in Taiwan who were born in the 1920s and experienced the February 28 Incident tended not to vote for the KMT in elections from 1990 to 2017, in comparison to non-Mainlander residents who were born after 1940. The average marginal effect of each generation illustrated in Figure A.1 also confirms a strong generational effect among the cohorts who experienced the Incident: non-Mainlanders born in the 1920s are, on average, 5.3 percent less likely to vote for the KMT's presidential candidates.

Table 4 The Effect of the February 28 Incident on Presidential Election (1990–2017)

Note: The reference group is non-Mainlanders born after 1940. The estimates of age, age2, Mainlander, Hakka, male, education, and married are not reported. Robust standard errors clustered at the township level in parentheses. The full table is available in the Online Appendix as Table A.5.

+ p < 0.10, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

It is noteworthy that the results of the presidential election outcome in the 1990s reflect only one election: the first direct presidential election in Taiwan, held in 1996. The incumbent Lee Deng-Hui from the KMT became the first directly elected president of Taiwan with 54 percent of the vote; Peng Ming-min from the DPP had the next largest count, with 21 percent. Lee Deng-Hui's personal background (e.g., allegedly as a victim of the Incident) and efforts in the 1990s may have played an important role in winning support from those experiencing February 28 Incident in the 1996 election. While the results for the 2010–2017 are from two presidential elections, the sample size is much smaller (i.e., less than 500 survey respondents born before 1950), making it difficult to examine generational effects for this period. The geographic effect (township victimization) is negative and marginally significant in Model (1) of Table 4, but not significant in separate subsamples. The marginally significant geographic effect suggests that statistical difference detected in presidential voting choices among respondents who were born in violence-ridden townships is not notably pronounced. On the other hand, in our subsample analysis of historically urban districts we find significant and large geographic effects (Table 2). In historically urban areas, where the Incident left a larger number of victims compared to other parts of the island, voters from heavily victimized districts are less likely to support candidates from the KMT (Column (1), Table 2). Holding other variables at the observed value, an increase in township victimization by 1 unit decreases the probability of voting for the KMT by an average of 5.2 percent. The same pattern was not found among rural townships (Table A.9). These results confirm our theoretical intuition that a deeper scar imposed on major cities induced a more pronounced long-term effect.

Estimates for controls are consistent with the overall findings from the previous studies. Voters who identify themselves as Mainlanders show strong support for the KMT. In addition, voters who self-identify as Hakka ethnicity appear more likely to support the KMT. More educated voters tend to support the KMT in presidential elections, and female and married respondents are also more likely to support the KMT.

EFFECTS OVER DECADES

Over the last three decades, the experienced generation and geographic effects have evolved differently. As shown in our empirical results in Table 1, the geographic effects were most salient in the 1990s, became smaller in the 2000s, and disappeared in the 2010s. However, the experienced generational effects on national and ethnic identities and presidential vote choices became strengthened in the 2000s and remained in the 2010s (as seen in Tables 1, 3, and 4), except that a statistically significant effect is not found with the small sample size of presidential votes from 2010–2017.

Overall, our results support the claim that the February 28 Incident has gradually become a topic of national political debate after democratization. Its effects are transmitted and shared by the affected generations, rather than being confined to heavily affected districts. The DPP's electoral campaign claiming the truth and reconciliation process regarding the Incident, such as the 228 Hand-in-Hand Rally in 2004,Footnote 37 was effective in mobilizing political support in the 2000s, although its effects have dwindled since. Lee Deng-Hui's KMT government introduced a series of measures to compensate victims in the 1990s. This also appears to have contributed to his presidential election in 1996. While the saliency of the Incidence in national and ethnic identities remains throughout the 2010s, its salience in presidential elections is to be examined once data from the years after 2017 are available. A noteworthy point is that even though the direct effect of the Incident on the presidential election campaign may dissipate over time, the overall impact is likely to remain because vote choices are often driven by identities, on which we find continuously strong effects of the Incident in the recent period.

ROBUSTNESS

Three other empirical specifications are worth exploring. First, we additionally employ the hierarchical APC (HAPC) model following the most up-to-date methodological suggestions from recent studies (Smets and Neundorf Reference Smets and Neundorf2014; Huang Reference Huang2019). We note that our estimates of interest do not exactly fit the standard APC model, where the entire generation is assumed to share the same experience or socialize together. Nonetheless, to address potential concerns regarding the collinearity among cohort, age, and period, we employ HAPC models as our first robustness check. As shown in Table 5, the results suggest that our earlier findings are robust. After accounting for the linear cohort trend and the age effect in a quadratic form in Level 1, in additional to the random effect estimation of the cohort effect and the period effect in Level 2, we find that non-Mainlanders who experienced the Incident are significantly less likely to support the KMT candidate or key policy, or identify themselves as Chinese.Footnote 38 Interestingly, we find that the geographic effects in presidential vote choices and ethnic identity are now statistically significant.

Table 5 HAPC Analysis: The Effect of the February 28 Incident (1990–2017)

Note: The reference group is non-Mainlanders born after 1940. We employ the mixed effect ordered probit for Models (1) and (2) (meoprobit in Stata), and mixed effect probit for Model (3) (meprobit in Stata). The full table is available in the Online Appendix as Table A.10, A.11 and A.12.

+ p < 0.10, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Second, we exclude Mainlanders from our sample. As shown in Table A.13, our primary results remain qualitatively similar if we exclude Mainlander observations, except that the generational effects in presidential elections no longer exist, with high correlation between the cohort and age variables.Footnote 39 Third, although we do not theoretically expect an endogeneity problem with victims, as detailed in Section 3, we explore a potential instrumental variable (IV) approach. As mentioned, the KMT troops came to two major ports of Taiwan, Keelung and Kaohsiung, and were deployed throughout the island. Motivated by this historical fact, we construct an instrumental variable using the shortest distance from these two ports. In our two-stage least squares regression, we regress the township victimization on the shortest distance from the two ports, which we find to be negative and statistically significant. In the second stage, we estimate electoral behavior and political attitudes using the instrumented township victimization variable. As reported in Table A.14, we find that for all dependent variables, our instrumented township victimization variables show negative and statistically significant associations. Although the results are clearly supportive of our findings, we report these findings as additional results rather than primary ones, given our concerns about the exclusion restriction. The IV specification requires that our instrumental variable (the distance from the ports) affect the dependent variable (the KMT support) only through its effect on repression and we cannot completely rule out the possibility of all other channels in the past 70 years.

CONCLUSION

Political violence significantly reshapes the psychology of residents who are directly or indirectly exposed to the event. Although these incidents have left lasting marks on the politics of the countries where they occur, how these traumatic events shape individuals’ attitudes in the long run has rarely been analyzed systematically. Among recent studies delving into the long-term effects of violent events, evaluations of the fluctuating effects over time and the diverse mechanisms of effect transmission have been scarce.

Using the case of Taiwan's February 28 Incident, this study has examined how an incident of political violence has affected political identities and voter choices of Taiwanese citizens after the country's democratization nearly a half century later. We focus in particular on exploring generational and geographic mechanisms through which traumatic effects may be sustained, tracing how those effects change over thirty years of democracy. We find supporting evidence for the long-term effect of political violence and repression: compared to subsequently born non-Mainlander cohorts, non-Mainlander respondents who experienced the Incident during their school years or in their 20s were less likely to identify themselves as supporters of unification with People Republic of China or as Chinese. They are also less likely to support the KMT in presidential elections held after democratization. Furthermore, political violence may also leave long-lasting scars in severely damaged districts, as recently found in other contexts (Rozenas, Schutte, and Zhukov Reference Rozenas, Schutte and Zhukov2017; Rozenas and Zhukov Reference Rozenas and Zhukov2019). We find that voters residing in heavily victimized townships were more likely to support building a new nation. Our subsample analyses reveal more nuanced geographic effects on elections: in historical urban districts where the destructive effect of the Incident was more concentrated, we find that voters from victimized townships were more likely to reject unification and vote against the KMT candidates in presidential elections. While our study is not the first to provide evidence of the long-term effects of political repression, it advances our understanding by revealing that the effects are not constant across time and districts. Instead, the impact fluctuates conditional on contemporary political conditions and the severity of damage caused by the repression.

Our study suggests that the traumatic effects of political violence in the past do not naturally dissipate after democratization. Our results show that the February 28 Incident has gradually become a topic of political debate at the national level. The Incident's effects become shared by the affected generations, not limited to heavily affected districts. Although the generations who lived through the Incident will be less and less able to participate in future elections, this does not necessarily suggest that the political effects of the Incident will simply fade away. In fact, the traumatic effect may be transmitted to their descendants, as found by Lupu and Peisakhin (Reference Lupu and Peisakhin2017). Our study suggests that transitional justice and reconciliation following authoritarian repression require a long-term process with consistent effort by the government as well as citizens. Finally it is worth highlighting the role of democracy in coping with a historical tragedy. Democratic elections in Taiwan have led the issue of the Incident politically salient. At the same time, democracy also has provided an arena for people to disclose, reconcile, and potentially resolve the conflict over time. Although how effective the reconciliation is may depend on political environment, party system, and the progress of transitional justice, the case of the February 28 Incident clearly shows how a social and political conflict can be peacefully discussed and managed in a democratic system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank John Fuh-sheng Hsieh, Sarah Hummel, Gabriel Lenz, Anja Neundorf, Grigore Pop-Eleches, and the participants of the panel for Authoritarian Legacy at the 2017 MPSA Annual Meeting for comments and suggestions. We also thank Jhih-Wei Lee, Meng-Huang Chiou, and Hui-Yin Chen for their assistance for data collection and coding and Yishuang Li and Ching Hsuan Lin for research assistance. We would like to thank Academia Sinica's Institute of Sociology and the Center for Survey Research for sharing the Taiwan Social Change Survey (TSCS) data collected in 1990, 1992, 1993, 1995, 1998, 2000 and 2010, and Chiuling Chen for assistance regarding the TSCS data. We would like to thank the Election Study Center of National Cheng Chi University for sharing its survey data conducted from 1991 to 2000 and Taiwan's Election and Democratization Study (TEDS) Project for sharing its survey data collected from 2001 to 2016 (for detailed data information, please visit http://teds.nccu.edu.tw/main.php). Responsibility for any errors in the resulting article remains our own.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2021.24.

CONTRIBUTIONS OF FUNDING ORGANIZATIONS

Fang-Yi Chiou acknowledges the research grant support for hiring research assistants from Taiwan's Ministry of Science and Technology (grant number: MOST 105–2628-H-001–002-MY3).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare none.