Introduction

Today, a significant majority of the Japanese people participate in Western musical culture (in the broadest sense); as composers, arrangers, performers or producers; as teachers or students; as writers, translators, editors or publishers of music literature; as programmers of music software; as workers in the music industry; as members of non-professional music ensembles; or, not the least, as consumers. Even outside Japan, for example in Europe or in the United States, the contribution of Japanese artists and companies to Western musical culture is everywhere evident. The question of how and why this came to be should be of interest to all historical musicologists.

Although there was some Western music in Japan as early as the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the roots of Japan's participation in the Western musical tradition lie in the late nineteenth century and are closely connected to the end of seclusion (1854) and the consequent process of modernization in Japan. Although Japan never became a Western colony, these changes occurred under strong pressure from Western colonial politics, and thus the Japanese modernization can be seen, from a global viewpoint, as a part of the history of nineteenth-century Western colonialism, or, in other words, as a chapter of Western history. So it might not be as strange as it seems at the first glance that an article focusing on modernization in a traditional Japanese music genre is to be found in a journal that focuses on nineteenth-century Western music culture.

There is already a certain tradition in musicology of looking at the modernization of Japanese music culture mainly as a history of the ‘introduction’ or ‘reception’ of Western music into Japan.Footnote 1 This view, however, systematically overlooks the areas of musical creativity. In the early period of modernization, the people concerned with the introduction and reception of Western music were – with a few distinguished exceptions – not professional musicians, but military leaders, missionaries, educators and politicians with limited musical ability. Musical creativity, on the other hand, naturally took place mainly in those realms of musical culture where musical ability and professional experience were available, namely among traditional musicians, who had limited access to and knowledge of Western music. That the reception of Western music was not an important part of their musical creativity does not mean, however, that their creativity had nothing to do with modernization.

First, although there is no question that modernization often went along with Western influences, ‘Western influences’ in musical culture do not necessarily mean influences of Western music. In the late nineteenth century, a modern (Western) method of education, with singing as an essential element, was introduced in Japan. Japanese educators studied the use of songs in this method and looked for a way to introduce singing to Japanese educational institutions as well. In the case of gagaku songs, however, the existing music itself was not introduced. Instead, new Japanese songs were composed for the method. So although the style of the new songs was strongly shaped by the character of the new method as well as by other tendencies of the modernization period, and thus it was certainly a ‘modern’ style, the reception of Western melodies played a minor role in this process.

Second, the modernization of Japan had another face, which deliberately rejected outside influences – not only those from the West, but also those from the Asian continent, which had informed Japanese culture for many centuries. This is why the radical changes at the beginning of modernity in Japan are also called a ‘Restoration’.Footnote 2 On the one hand, the Restoration was a consequence of a then two-centuries-old school of thought – the so-called ‘national studies’ [kokugaku, ![]() ], which may even be described as an ‘anti-modern’ rather than a modern movement. On the other hand, the ‘national studies’, and their influence on Japanese intellectuals, were used to legitimize and shape the modern nation that would eventually compete with the Western nation states. The banishment of all foreign things, even the traditional ones rooted in daily life, and the insistence on a Restoration of the ‘true old’ Japan, was thus an important part of the process of building a modern nation state. The creation of gagaku songs was perhaps one of the most Restorationist musical attempts of this era.

], which may even be described as an ‘anti-modern’ rather than a modern movement. On the other hand, the ‘national studies’, and their influence on Japanese intellectuals, were used to legitimize and shape the modern nation that would eventually compete with the Western nation states. The banishment of all foreign things, even the traditional ones rooted in daily life, and the insistence on a Restoration of the ‘true old’ Japan, was thus an important part of the process of building a modern nation state. The creation of gagaku songs was perhaps one of the most Restorationist musical attempts of this era.

To be sure, a Restorationist approach in general requires more creativity than the introduction of a foreign entity, especially in music, where the Restoration of a practice more than 1,000 years old can only be a fiction. (One may remember the intended ‘Restoration’ of the Ancient Greek tragedy in sixteenth-century Italy that resulted in the creation of modern opera.) In late-nineteenth-century Japan, Restoration of true Japanese music meant creating a new music that differed from both Western and Asian continental music, as well as contemporary Japanese music, and conformed to historical knowledge. To fill the desideratum of songs for a Western method of education with autochthonous music was a difficult task, certainly more difficult than it would have been to import the Western melodies together with the method. In the end, this difficulty, and the pressure to reach acceptable results in a short time, made the introduction of Western melodies prevail in public music education over all competing projects. The surviving relicts of educational music of that time thus create the misleading impression that innovation was mainly bound to the introduction of Western music. But in reality, the development of modern musical creativity in Japan started not from the introduction of Western music, but from traditional music. The significance of gagaku songs for this development is reflected in the fact that a number of composers of gagaku songs were among the first who succeeded in composing Western-style songs somewhat later.Footnote 3

This article is a case study of one of the many genres of Japanese traditional music that appeared together with modernity.Footnote 4 My aim is to shed some light on song collections in a mostly Restorationist style that were compiled by gagaku professionals – members of the imperial court music department – between 1877 and 1884 for a decidedly modern education. As one of the earliest examples of modern composition in Japan, this music attracts special interest, but it has received little analytical study.Footnote 5 Since my aim is to write this article as a part of the history of globalizing Western music, I will use a method of research that is more common for Western musical studies than for ethnomusicology: that of asking about the ‘compositional problems’ that the composers dealt with. This should not be done, however, without a consideration of whether and how Western concepts of musical analysis are applicable for the subject. I therefore begin with this question before proceeding to a more precise demarcation of the term ‘gagaku song’. After a treatment of technical questions relating to the analysis of gagaku songs, and an overview of music-theoretical categories and the ways in which they have changed during the compilation period, I close with analyses of three songs.

Questions

What kind of compositional problems did late-nineteenth-century composers of gagaku songs face, and how did they solve them? What characterizes the musical structure of their works? Before we try to answer these questions, it might be useful to question the questions themselves: are gagaku songs a musical genre in which ‘composers’ dealt with ‘compositional problems’ and created ‘works’ with a ‘musical structure’? These are concepts primarily associated with Western classical music, and they imply a concept of individuality of the creator and originality of the created that is by no means universal to all music.

‘Composer’

In the great majority of contemporaneous sources for late-nineteenth-century gagaku songs, each song is preceded by a few formalized head lines containing the song's title, the origin or author of the words, the composer's name, including his rank in the hierarchy of court musicians, and a number of technical terms specifying the genre, key, scale, metre and length of the song.Footnote 6 That the composer's name is seldom omitted, means that a kind of authorship was attributed to the one who had attached the music to the words; the obligatory mention of the official rank, on the other hand, reflects the fact that the author was working as a representative of his professional community. The compositions were commissioned to the court music department, and it seems that they were then assigned to individual members. The completed pieces were returned to their commissioners through the head of the department. Thus, although each piece had an individual author, it belonged to a collection that was the intellectual and artistic property of the department. If an author introduced something new, it was also a new achievement for the community, and he could do so only in accordance with the social relations within his group – either because he was acknowledged by his colleagues as an especially powerful specialist in that area, or because the innovation was approved by such an authority. In either case, the author did not retain rights to the innovation, which was available for use in new songs by his colleagues.

‘Work’

A gagaku song can thus be described as the work of a professional collective: the author of a single song was the collective, as represented by an individual member. The new songs were copied by all members of the court music department into their personal song books, and became part of the court music repertoire taught in the gagaku school and performed in public concerts.

Composition was called ‘choice of notes’ [sen-fu,

![]() ], and ‘notes’ meant the neumatic gagaku notation [hakase,

], and ‘notes’ meant the neumatic gagaku notation [hakase,

![]() ], in which each note stands for a short melody. To compose was to choose from existing melodies rather than to invent new ones. As I have shown in another article, even the Japanese national anthem, composed in 1880 by court musicians for a Western style military band, and thus not a typical gagaku song, consists mainly of common phrases of gagaku songs; the only phrases that are not common ones are closely related to an earlier version of the national anthem that was composed by a Westerner.Footnote 7

], in which each note stands for a short melody. To compose was to choose from existing melodies rather than to invent new ones. As I have shown in another article, even the Japanese national anthem, composed in 1880 by court musicians for a Western style military band, and thus not a typical gagaku song, consists mainly of common phrases of gagaku songs; the only phrases that are not common ones are closely related to an earlier version of the national anthem that was composed by a Westerner.Footnote 7

The individual author mentioned at the beginning of a song was responsible for the choice of melodic phrases, and it was acceptable to choose even longer sections of other songs if they fitted to the new words. The choice of a whole pre-existing melody for a new poem did not qualify for new authorship, however. There are several cases where pre-existing melodies were used instead of composing a new melody, and in those cases no author is mentioned, but the title of the song whose melody was used is specified.Footnote 8 Every authorized composition is thus new as a whole, but not necessarily in any of its parts. A single ‘work’ had to conform with the collection, and as a whole it had to be musically distinguishable from the other songs of the collection.

‘Musical structure’

The technical information specifying the genre, key, scale, metre and length of the song that headed each song was based on the music theory of gagaku, but in a somewhat modernized and standardized form.Footnote 9 Since the court musicians were responsible for this standardization, they must have been very much aware of the formal and structural aspects of the music; and this awareness is reflected in contemporaneous writings.

Another structural factor is the metrical structure of the poetry. Only very formalized poems in the conservative style of court poetry were proposed for composition. And a third structural feature relies on the rhythmic order provided by the accompanying instruments. The rhythm is measured by the regular beats of the shakubyōshi [

![]() ], a type of wooden clappers, which guarantees a regular tempo. Most songs are also accompanied by an ostinato, played on the wagon [

], a type of wooden clappers, which guarantees a regular tempo. Most songs are also accompanied by an ostinato, played on the wagon [

![]() , a six-stringed zither], which is repeated several times throughout the piece, although the melody of the song normally does not contain any repetition. The use of wagon ostinatos for accompaniment was adopted from traditional gagaku genres, but, in contrast to them, the gagaku song accompaniments are not common for the whole genre, but (essentially) individual for every piece. The wagon patterns therefore form an individual structural background, which is heard throughout the performance of a song.

, a six-stringed zither], which is repeated several times throughout the piece, although the melody of the song normally does not contain any repetition. The use of wagon ostinatos for accompaniment was adopted from traditional gagaku genres, but, in contrast to them, the gagaku song accompaniments are not common for the whole genre, but (essentially) individual for every piece. The wagon patterns therefore form an individual structural background, which is heard throughout the performance of a song.

‘Compositional problems’

It can be assumed that the commissioner of a song gave a poem to the court music department and prescribed the genre of the song, such as shōka [

![]() , ‘singing piece’ with wagon accompaniment] or yūgi [

, ‘singing piece’ with wagon accompaniment] or yūgi [

![]() , ‘play-song’ without wagon accompaniment], so that these elements were not a matter of choice for the composer. Other elements might be prescribed by the head of the department, or were determined by convention. If, for example, the poem contained a reference to one of the four seasons, the key of the song was pre-determined, by a rule that was given in the textbooks that were used by the court musicians in teaching and learning.

, ‘play-song’ without wagon accompaniment], so that these elements were not a matter of choice for the composer. Other elements might be prescribed by the head of the department, or were determined by convention. If, for example, the poem contained a reference to one of the four seasons, the key of the song was pre-determined, by a rule that was given in the textbooks that were used by the court musicians in teaching and learning.

In any case, the very strict limitations of each formal category made it necessary to find a strategy to fulfil all requirements, and, as we will see in our analysis, dealing with conflicting requirements was no small challenge. Since there was no tradition of song composition among the court musicians at the beginning of the era of gagaku songs, it is very unlikely that the composers had received any instruction to support them in solving these problems. They may have supported each other with their ideas and experience, but in many cases they would have to find a new solution through new strategies. So ‘compositional problems’ really did exist for gagaku song composers, and it is an interesting challenge for musical analysis to determine what they were and how they were solved.

Subject of Analysis

For the purposes of this article, ‘gagaku songs of the late nineteenth century’ means songs that were commissioned officially to the court music departmentFootnote 10 and composed in a non-Western style by its eligible members (or authorized by them),Footnote 11 during the first half of the Meiji Era (1868–1912).Footnote 12 The most important collections of gagaku songs, in this sense, are Hoiku shōka [

![]() , Childcare songs],Footnote 13 of which there are about 100 songs, and Kōtenkōkyūsho shōka [

, Childcare songs],Footnote 13 of which there are about 100 songs, and Kōtenkōkyūsho shōka [

![]() , Songs for the Institute for Research of the Imperial Classics], with 24 songs. Both collections were commissioned by educational institutions.

, Songs for the Institute for Research of the Imperial Classics], with 24 songs. Both collections were commissioned by educational institutions.

In the wider sense, songs that were composed by members of the court music department for private purposes or by independent commission, and songs composed in the style of gagaku songs by non-members of the court music department, including non-professional gagaku scholars, should also be considered as gagaku songs. There is a great variety of such songs in various kinds of sources, but their diversity makes it difficult to draw a line between proper gagaku songs and other songs that are only influenced by gagaku style. Furthermore, it is difficult to discuss this question without an analysis of the stylistic features of gagaku songs. For this reason, this paper focuses only on the two collections.

The beginning of Hoiku shōka lies in the commission of two songs for the opening ceremony of the Kindergarten of the Tokyo Women's Normal School [

![]() , Tōkyō Joshi Shihangakkō fuzoku Yōchien] in 1877.Footnote 14 Thereafter, until 1880, about 100 songs for kindergarten children and older students were composed and taught by court musicians to students at the Tokyo Women's Normal School and other schools. The names of 24 court musicians and one kindergarten teacher, the only woman who contributed to the music of an official gagaku song collection,Footnote 15 are mentioned in the sources as composers of Hoiku shōka.

, Tōkyō Joshi Shihangakkō fuzoku Yōchien] in 1877.Footnote 14 Thereafter, until 1880, about 100 songs for kindergarten children and older students were composed and taught by court musicians to students at the Tokyo Women's Normal School and other schools. The names of 24 court musicians and one kindergarten teacher, the only woman who contributed to the music of an official gagaku song collection,Footnote 15 are mentioned in the sources as composers of Hoiku shōka.

From 1880 to 1882 the work on the collection seems to have paused, perhaps because, after the foundation of the Institute of Music of the Ministry of Education [Monbushō Ongaku Torishirabe Gakari,

![]() ] in 1879 and the appointment of Luther Whiting Mason as the first foreign teacher for music education, the court musicians concentrated on the study of Western music.Footnote 16 In 1882 and 1883, after Mason had returned to America, the work on Hoiku shōka was resumed. In this period the earlier songs underwent a fundamental revision,Footnote 17 and a number of melodies were added and others deleted. At that point, the songs were already used in a number of educational institutions throughout the country. The plan of publication seems to have failed, however, and the collection fell out of use within a few years.Footnote 18 Only a few songs found their way into later songbooks.

] in 1879 and the appointment of Luther Whiting Mason as the first foreign teacher for music education, the court musicians concentrated on the study of Western music.Footnote 16 In 1882 and 1883, after Mason had returned to America, the work on Hoiku shōka was resumed. In this period the earlier songs underwent a fundamental revision,Footnote 17 and a number of melodies were added and others deleted. At that point, the songs were already used in a number of educational institutions throughout the country. The plan of publication seems to have failed, however, and the collection fell out of use within a few years.Footnote 18 Only a few songs found their way into later songbooks.

Hoiku shōka is preserved in the traditional gagaku notation in many handwritten copies, representing different stages of the compilation. A number of them were written by court musicians who participated in the collection as composers, and some of the most important sources remain in the private collections of the families of court musicians.Footnote 19

Kōtenkōkyūsho shōka was compiled in 1883 or 1884 for the Kōtenkōkyūsho, a school founded to educate Shinto clergymen. The songs were taught there for some years, but never found a wider distribution. Kōtenkōkyūsho shōka consists of 24 songs composed by 24 court musicians, 21 of whom had also contributed to Hoiku shōka.

As already mentioned, gagaku songs are performed with the accompaniment of shakubyōshi and wagon. For Hoiku shōka, but not for Kōtenkōkyūsho shōka, there exists a complete set of accompaniments for the sō [

![]() ], a thirteen-stringed zither (the instrument is often simply called ‘koto’ [

], a thirteen-stringed zither (the instrument is often simply called ‘koto’ [

![]() ], although the term koto, in its proper use, comprises other zithers as well, including the wagon), which was added for practical reasons after most of the songs were already composed. The sō accompaniment seems to have no new structural function in the song. The same is the case for the arrangements for full gagaku orchestra that exist for some of the songs.

], although the term koto, in its proper use, comprises other zithers as well, including the wagon), which was added for practical reasons after most of the songs were already composed. The sō accompaniment seems to have no new structural function in the song. The same is the case for the arrangements for full gagaku orchestra that exist for some of the songs.

Method of Analysis

The structure of the original notation of gagaku songs forced the composer to write down the words of the poem first (potentially even before he began to compose the song) and to add the melody afterwards.Footnote 20 This reflects a compositional process that gives priority to the words and regards melodies as something ‘attached to the words’. While the poem is visible as formed language, and is readable independently from the music, the connection between the melodic fragments is constituted only through the connection between the syllables to which they are attached. The phrasing is indicated by lines between the text syllables and is thus a property of the words rather than the melody.Footnote 21

In discussing compositional problems, we must not forget that traditional notation was the perspective from which gagaku song composers viewed their own and others’ works. Even if we find that a deep insight into genuinely musical forms was indispensable to compose a gagaku song, these forms were always attached to words, which came with their own form. My analysis thus begins with the words and then proceeds to the musical form.

Notwithstanding the role of the poetic form in the musical structure, musical time in gagaku songs is strictly cyclic, and is regulated by the ostinato of the accompanying instruments. The concept of timing is also graphically obvious in the wagon notation, where the symbols for the beats of the shakubyōshi form a geometric grid along which the notation is arranged.Footnote 22 Since the instrumental notation is separated from the vocal notation, however, the interrelation between the poetic form of the vocal part and the cyclic form of the instruments is not obvious from the notation.Footnote 23 Like medieval and renaissance Western polyphonic music, where the voices are notated separately, what sounds together can only be experienced in a real performance or calculated by counting beats in both notations. It is not known which strategies court musicians used to imagine the interaction between melody and accompaniment to conceptualize the musical form of a song.

In order to understand how gagaku composers worked on their songs we should actually put ourselves in their perspective and use the original notation for our analysis. Considering the fact, however, that most readers of this article are unfamiliar with East Asian scripts in general, and gagaku notations in particular, we will illustrate our analysis with transnotations to Western staff notation. Fortunately, the most essential musical parameters shown in the notation of gagaku songs, namely pitches and rhythmic values, are commensurable to Western staff notation, so that the transnotation is unambiguous in most cases. A transcription of Hoiku shōka to Western notation was published by Shiba Sukehiro,Footnote 24 but it does not include the accompaniment, and it shows, as a rule, only one version for each song. His transcription is a kind of compromise between a transnotation, which tries to preserve the structural and symbolic information of the original notation, and a translation to Western notation, which tries to render how a performance of the score sounds. The examples in this article are in a rather mechanical transnotation that looks less familiar to Western eyes, but forces the reader to think in the categories of gagaku music theory, especially with regard to beats and metre.Footnote 25

Some of our transnotations show the vocal part vertically arranged above the accompanying pattern (see Figure 5, below). The synchronous display is useful for musical analysis, but we should be aware that it is doubtless different from what the court musicians had in mind when they composed the songs. Our analysis will proceed from the general to the specific, beginning from a description of the style and ending with analyses of three songs.

Structural Categories

Form of the Poem

The gagaku songs use as texts either poems from the Man'yōshū (eighth century) and the ancient imperial collections or newer poems in the style of the ancient poetry.Footnote 26 Even the earliest gagaku songs of the Meiji Era, which were based on translations of Western song texts,Footnote 27 follow these extremely conservative forms. This means that all poems begin with a five-syllable clause,Footnote 28 followed by one or more pairs of clauses with seven and five syllables, and ending with a pair of seven and seven syllables.Footnote 29 The shortest form is the tanka [

![]() ] (5 7–5 7–7), while the longer forms are called chōka [

] (5 7–5 7–7), while the longer forms are called chōka [

![]() ].Footnote 30 The use of these ancient forms contrasts to most other songs composed in the same era, namely the songs compiled by the Ministry of Education, including most of the gagaku style ‘ceremonial songs’. Although the composers probably had no influence on the selection of texts, the poetic form is one of the important stylistic characteristics of the gagaku songs.

].Footnote 30 The use of these ancient forms contrasts to most other songs composed in the same era, namely the songs compiled by the Ministry of Education, including most of the gagaku style ‘ceremonial songs’. Although the composers probably had no influence on the selection of texts, the poetic form is one of the important stylistic characteristics of the gagaku songs.

In all songs the beginning five-syllable clause is sung unaccompanied, by the musical leader. The wagon accompaniment begins with the last syllable of the first clause, and the other singers begin with the second clause. The songs are sung in unison.

Key and Scale

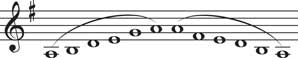

Gagaku songs have a genuine theory of scales, which is derived from traditional gagaku scales. The theory stipulates two modes, ryo and ritsu, usable in various transpositions, and two mixed scales. The theory and usage of the scales changed slightly during the compilation period. Since tonal analysis is not the focus of this article, only the scales used in the examples are displayed in Figures 1a and 1b in Western notation. They are called ichikotsuchō rissen [

![]() ] (used in Figures 3 and 4) and ōshikichō rissen [

] (used in Figures 3 and 4) and ōshikichō rissen [

![]() ] (used in Figure 5). These are ritsu scales based on the key notes D and A, respectively. As in a Western melodic minor scale, the fifth degree of the pentatonic ritsu scale is raised by a half tone if the melody ascends, so that the ascending scale is different from the descending scale.

] (used in Figure 5). These are ritsu scales based on the key notes D and A, respectively. As in a Western melodic minor scale, the fifth degree of the pentatonic ritsu scale is raised by a half tone if the melody ascends, so that the ascending scale is different from the descending scale.

Fig. 1a The D ritsu scale (ichikotsuchō rissen)

Fig. 1b The A ritsu scale (ōshikichō rissen)

Fig. 2a Two hyperbars in quick four metre

Fig. 2b One hyperbar in slow four metre

In singing practice the second and the descending fifth degree may be lowered somewhat, as shown in Figure 3c, but the transnotations here show the pitches as they are notated and stated to be correct by contemporaneous theoretical writings. For technical reasons, the wagon uses the tones of the descending scale in ascending as well.

Beat and MetreFootnote 31

The gagaku songs with accompaniment belong to two types of metre, ‘quick metre’ [haya-hyōshi,

![]() ] and ‘slow metre’ [shizu-hyōshi,

] and ‘slow metre’ [shizu-hyōshi,

![]() ]. They consist of rhythmical units called ‘big times’ [

]. They consist of rhythmical units called ‘big times’ [

![]() , written as

, written as

![]() ], ‘small times’ [

], ‘small times’ [

![]() , written as

, written as

![]() ], and ‘yin times’ [

], and ‘yin times’ [

![]() , written as ○].Footnote 32 Yin times are used in slow metre only. Essentially all times have the same length, but only big times and small times are beat. One hyōshi (we will call it a ‘hyperbar’) consists of one big time and several small times. In slow metre a yin time occurs after every beat. We call the time from one to the next beat a ‘bar’. For examples of metres, see Figures 2a and 2b.

, written as ○].Footnote 32 Yin times are used in slow metre only. Essentially all times have the same length, but only big times and small times are beat. One hyōshi (we will call it a ‘hyperbar’) consists of one big time and several small times. In slow metre a yin time occurs after every beat. We call the time from one to the next beat a ‘bar’. For examples of metres, see Figures 2a and 2b.

Fig. 3a Original notation, manuscript of Bunno Yoshiaki (1848–1920), who was also a composer of Hoiku Shōka; to read from the top to the bottom, the neumes and the columns from right to left.

Figure 3b Transnotation of Bunno's manuscript by the author.

Figure 3c Transcription by Tanabe Hisao (1919).

Figure 3d Transcription by Shiba Sukehiro, after a photocopy of a manuscript written by Shiba in 1955, original held by the Kunitachi College of Music Library.

Figure 3e Another transcription by the same, after the photographical reproduction of a manuscript written by Shiba in 1958, published in Ongaku kiso kenkyū bunkenshū, 1991. The deviation of an octave in bars 3–5 in Tanabe's transcription may be due to a deviation in the source he used, but more probably, it is a mistake by the transcriber. On the deviating key signature in Tanabe's transcription see above page 000. The other deviations reflect the divergent principles of transcription.

Fig. 4 Wagon ostinato of ‘Manabi no michi’

Fig. 5 The three songs ‘Hana tachibana’, ‘Shirogane’ and ‘Kashima no kami’ and their shared accompaniment.

The transnotations use the minim for the (big, small and yin) times and bar lines to indicate the beat times. Big time is indicated by a double bar line immediately preceding it. (Please note that the double bar line does not coincide with the boundaries of the hyperbars, since the big times do not fall on the beginning of a hyperbar.) A song in quick four metre [haya-yo-hyōshi,

![]() ] is thus written as a one-two time with a double bar line at every third bar of a hyperbar (see Figure 5, below), and the slow metres are written as a two-two time with double bar lines at the place of the big time (see Figures 3b and 4).

] is thus written as a one-two time with a double bar line at every third bar of a hyperbar (see Figure 5, below), and the slow metres are written as a two-two time with double bar lines at the place of the big time (see Figures 3b and 4).

Phrase and breath

Phrasing is an essential part of gagaku song notation and thus a structural element of the music. Vertical red lines between text syllables in the original notation indicate a continuous breath phrase, while the absence of such a line shows a break in the phrase (see Figure 3a, below). Similarly the phrasing in the transnotations is shown by horizontal lines between the text syllables (see Figures 3b and 5). In this article, the word ‘phrase’ always means a section of the melody that is sung in one breath. As I have shown elsewhere,Footnote 33 the treatment of phrases changed fundamentally between the earlier and later Hoiku shōka, and the phrasings of many earlier gagaku songs were revised around 1882.

Embellishments

Gagaku song notation shows the rough melodic shape as lines drawn at the left side of the text syllables, and the exact pitches with the Chinese characters for the relative tone names – kyū [

![]() ], shō [

], shō [

![]() ], kaku [

], kaku [

![]() ], chi [

], chi [

![]() ], u [

], u [

![]() ] for the five pentatonic scale degrees and ei-u [

] for the five pentatonic scale degrees and ei-u [

![]() ] for the heightened fifth degree in the ascending ritsu scale – above the lines (see Figure 3a). There are, however, two kinds of embellishments that are not shown as pitches: tsuku [

] for the heightened fifth degree in the ascending ritsu scale – above the lines (see Figure 3a). There are, however, two kinds of embellishments that are not shown as pitches: tsuku [

![]() ] is a kind of upper mordent, mostly performed on the second beat or unbeat time of a longer note, as at the seventh text syllable in Figure 3, and yuri [

] is a kind of upper mordent, mostly performed on the second beat or unbeat time of a longer note, as at the seventh text syllable in Figure 3, and yuri [

![]() ] is a kind of slow double lower mordent, performed on long notes (either kyū or chi) as on the fifth text syllable in Figure 3. There is no exact explanation of its performance in the primary sources of gagaku songs. The approximate performance may be as shown in the transcriptions of Tanabe HisaoFootnote 34 and Shiba Sukehiro (Figures 3c, 3d, 3e). In our transnotations we use signs similar to the original notation (Figure 3b).

] is a kind of slow double lower mordent, performed on long notes (either kyū or chi) as on the fifth text syllable in Figure 3. There is no exact explanation of its performance in the primary sources of gagaku songs. The approximate performance may be as shown in the transcriptions of Tanabe HisaoFootnote 34 and Shiba Sukehiro (Figures 3c, 3d, 3e). In our transnotations we use signs similar to the original notation (Figure 3b).

Musical forms

While a majority of the gagaku songs, even many of the longer ones, have a linear form and cannot easily be divided into parts, some forms use repetitions or multipart concepts. A comprehensive description of them is beyond the scope of this article. Larger songs are often divided into two or more dan [

![]() ] (stanzas or movements), either with the same melody or with different melodies. Some of the multipart forms adopt the concept of jo-ha-kyū Footnote 35 [

] (stanzas or movements), either with the same melody or with different melodies. Some of the multipart forms adopt the concept of jo-ha-kyū Footnote 35 [

![]() ], a form that is used in traditional multipart gagaku pieces.

], a form that is used in traditional multipart gagaku pieces.

The forms of the earliest songs of Hoiku shōka show some influence from Western songs, but this influence is hardly detectable in later songs. The variety of approaches on the one hand and the establishment of common form concepts for different pieces on the other hand show that the development of larger musical forms posed a continuous challenge for the individual composers as well as for the collective of composers.

Accompaniment patterns

As already mentioned, gagaku songs – except the play-songs – are accompanied not only by the regular beats of the shakubyōshi but also by an ostinato on the wagon. A wagon ostinato may be one or several hyperbars long, and the length of an accompanied song is a multiple of the length of the wagon ostinato.

The structure and development of the wagon ostinatos show most clearly the innovation in the gagaku songs and the peculiarities of the collective creative process. The use of the wagon, which was believed to be one of the most authentic ‘national’ instruments of Japan (as opposed to instruments imported from China or elsewhere), was a strong and Restorationist symbol of the autonomous development of a modern Japanese music. Founded in the old tradition of Shinto ritual music, the ostinatos had no counterpart in the Western educational songs that served as models for the early Hoiku shōka; yet the way in which they were applied to the new compositions had no model in traditional Japanese music. Nevertheless, the foundations of the new concept were established in a very short time and then adopted by all composers of gagaku songs.

The wagon patterns are composed of very simple elements. The wagon is played with a plectrum with the right hand and with the fingers of the left hand. The most important playing technique is to pluck all six strings either forth or back with the plectrum and to damp five or four of them immediately afterwards with the fingers of the left hand, so that after an arpeggio of all strings the sound of only one or two strings remains.Footnote 36 Other techniques are to pluck all strings without damping, to pluck only one string with the plectrum, or to pluck one, two or (seldom) three strings together with the fingers of the left hand. There are no other techniques used to modify the tone.

The rhythms used for the wagon patterns are also very simple. In slow metres, one of the above-mentioned elements is played on every beat, and on the unbeat times an element may be played or not. If an element is played on the unbeat time, there may also be a tone (never an arpeggio or two tones played together) between the times. That means that in our transcription the rhythm of the wagon can be written in semibreves, minims and crotchets, and there are no dotted rhythms, rests or syncopations. Figure 4 shows the wagon pattern of the song shown in Figure 3, a one-hyperbar pattern in slow five metre. The tones with ‘+’ mark are plucked with the left hand.

The same rhythms are used in quick four metre, replacing the unbeat times by the second and fourth beat of the hyperbar, as seen in the lowest staff of Figure 5, below.

Since the wagon can only play the five main scale degrees in a closed one-octave register, its melodic possibilities are very limited, and the rhythmic effect seems to prevail. In the longer ostinatos, however, its melodic significance cannot be ignored, and the change between the stable key tone, the relatively stable fifth and the unstable other scale degrees gives them a decisive shape.

Despite these restrictions, the characteristics of the wagon patterns show a great variety, and the changes of their external form, elaboration, relation to the song melody and intertextual structures tell us a story of continuous collective and individual problem solving. At this point, we may turn to the external and collective aspects, leaving the other aspects to the individual analysis at the end of the paper.

The earliest nine songs with accompaniment, composed for the kindergarten between November 1877 and February 1878 by nine different composers, are all in quick four metre, and each song has an individual wagon pattern, which is from three to seven hyperbars long. The ostinato is played from two to six times. It is surprising that the most essential properties of the wagon accompaniments and the way they are related to the melody are already seen in the very first song, ‘Fuyu no madoi’ [

![]() , ‘Gathering in winter’], composed in 1877 by Tōgi Suenaga.Footnote 37 By the way, Suenaga was also the first to use slow metre in Hoiku shōka, namely in the song ‘Manabi no michi’ shown in Figures 3 and 4. If any individual can be named for having coined the style of late-nineteenth-century gagaku songs, it is Tōgi Suenaga.

, ‘Gathering in winter’], composed in 1877 by Tōgi Suenaga.Footnote 37 By the way, Suenaga was also the first to use slow metre in Hoiku shōka, namely in the song ‘Manabi no michi’ shown in Figures 3 and 4. If any individual can be named for having coined the style of late-nineteenth-century gagaku songs, it is Tōgi Suenaga.

Two new tendencies can be seen in the next 21 songs with accompaniment, composed from March to October 1878. First, while the song melodies become more elaborated – some of them are apparently not for the kindergarten but for older students – and now also use the slow four and five metres, the wagon patterns tend to become shorter: for example, only two hyperbars in quick four metre and one hyperbar in the slow metres. This means that the number of repetitions increases, and now ranges from 3 to 18 for simple songs and up to 44 in a multipart song. Second, some of the songs do not use new wagon patterns but re-use the accompaniment of other songs, with longer and more complex patterns particularly subject to re-use. One would perhaps expect that two songs sharing a complex accompaniment become very similar in melody and character, but that is not the case. The re-use of accompaniments in this period forms a rather subtle method of intertextual relationship between songs. It is remarkable that this experimental approach to compositional structures was undertaken in a decisively collective process. The seven songs composed between April and October 1878 that re-use accompaniments are by seven different composers; and with one exception, the composer who re-uses an accompaniment is different from the original composer. Thereafter the re-use of accompaniments stopped,Footnote 38 which also seems to have been a collective decision. While in most cases we cannot be certain in which order the melody and accompaniment were composed, the cases of re-use of accompaniment give us an interesting insight into the process of creating musical structures in late-nineteenth-century Japan.

The next 21 songs, composed between November 1878 and September 1879, continue the tendency of the previous songs, but every song now has its own wagon pattern again, as in the first period. The range of metres is extended by the exceptional slow two, three, six and eight metres, and the slow metres become predominant. The tendency to more elaborated and longer, multi-part songs also continues. The longest gagaku songs composed in the late nineteenth century are from this period, an exemplary case being the five-part song ‘Ō Shōkun’ [

![]() , ‘Wang Zhaojun’], a poem by Murata Harumi (1746–1811) composed by Oku Yoshiisa (1858–1933) and datedFootnote 39 May 1879, which has a total length of 604 times.Footnote 40 The longer songs do not use longer wagon patterns, but repeat them more often. The first four parts of ‘Ō Shōkun’, for example, are composed in slow five metre, each of them different in length and with its own melody, but using the same wagon pattern of one hyperbar length, which is repeated 58 times. Even in the fifth part, written in quick four metre, a one-hyperbar pattern is used. A one-hyperbar pattern in quick four metre is the shortest possible ostinato in a gagaku song. Such short patterns make their first appearance in this period, in the last stanzas of multipart songs, which correspond to the kyū part of the jo-ha-kyū concept. Later, they are also used in single short gagaku songs. Repeated every few seconds, a pattern this short has no melodic relevance, but, besides its rhythmic importance, also adds a sound colour to the piece.

, ‘Wang Zhaojun’], a poem by Murata Harumi (1746–1811) composed by Oku Yoshiisa (1858–1933) and datedFootnote 39 May 1879, which has a total length of 604 times.Footnote 40 The longer songs do not use longer wagon patterns, but repeat them more often. The first four parts of ‘Ō Shōkun’, for example, are composed in slow five metre, each of them different in length and with its own melody, but using the same wagon pattern of one hyperbar length, which is repeated 58 times. Even in the fifth part, written in quick four metre, a one-hyperbar pattern is used. A one-hyperbar pattern in quick four metre is the shortest possible ostinato in a gagaku song. Such short patterns make their first appearance in this period, in the last stanzas of multipart songs, which correspond to the kyū part of the jo-ha-kyū concept. Later, they are also used in single short gagaku songs. Repeated every few seconds, a pattern this short has no melodic relevance, but, besides its rhythmic importance, also adds a sound colour to the piece.

In the following period, the regular production of gagaku songs gradually ceased, until it temporarily stopped between mid-1880 and spring of 1882. Several songs that were added in this period were not newly composed, but were new poems adapted to pre-existing melodies. Since not all later songs of Hoiku shōka can be dated exactly, it is not possible to give an exact number for how many songs were composed before the interruption, but a clear stylistic tendency can be observed: songs become shorter again, quick metres prevail, wagon patterns remain individual for each song and very short patterns become more frequent.

This tendency is even more obvious after the interruption. The songs that were newly composed in 1882Footnote 41 are the shortest of all songs in Hoiku shōka, and almost half of them have a one-hyperbar wagon pattern in quick four metre. It is rather surprising that all of these short patterns are different, because such short patterns become necessarily very similar, and it is probable that it worked only because the composers were very careful to make them all different. The tendency towards simple wagon accompaniments can also be seen in some revisions of older pieces that were made at that time, replacing longer patterns by shorter ones.Footnote 42

The songs of Kōtenkōkyūsho shōka, the last official gagaku compositions in the nineteenth century, are generally similar to the latest Hoiku shōka: rather short and simple and most of them in quick four metre. Concerning the accompaniment, however, there is a great difference, since the composers decided to use the same accompaniments wherever possible. Essentially all short songs in quick four metre are accompanied by the same one-hyperbar pattern. (This pattern is not identical to any of the accompaniment patterns of Hoiku shōka.) The idea that the wagon accompaniment should give an individual colour to the piece seems not yet sustained in Kōtenkōkyūsho shōka. As already mentioned, the use of an ostinato that is common to all songs of a genre is characteristic for some traditional genres of Japanese court music. Restorationist tendencies were important for the gagaku songs from the beginning, but in the late years it seems that they gained more power.Footnote 43 This may be due partly to the reaction against the Westernized music education that had already begun, but also to the fact that Kōtenkōkyūsho shōka was composed for the education of Shinto clergymen and not, as Hoiku shōka, for general education.

The gagaku songs thus become longer until 1879 and then shorter again, but the wagon accompaniments are longest in the beginning and shortest in the end. While the early accompaniments have a strong significance for the musical form, the later patterns give mainly a colour and rhythmic effect to the piece. In Kōtenkōkyūsho shōka they finally lose their individuality and become a purely formal element of the genre.

Analysis of Three Songs that Share an Accompaniment

The songs discussed below are shown in Figure 5.

‘Hana tachibana’ [

, ‘Tachibana flowers’]

, ‘Tachibana flowers’]

The poem is a free adaptation of an English song text. The prose translation was versified in the form 5 7–5 7–7 7, a tanka with an added seven-syllable clause:Footnote 44

Satsuki tatsu / kewai mo shiruku / waga yado no

hana tachibana wa / hokorobi ni keri / niwa mo kaorite

Literal translation, clause by clause:

The fifth month begins / the atmosphere is moist / and at our house

The tachibana flowers / have bloomed / and the garden is fragrantFootnote 45

The song is dated 22 February 1878 and was composed by Yamanoi Motokazu (1853–1908).Footnote 46

A certain type of syllabic gagaku songs in quick four metre was already established at the time ‘Hana tachibana’ was composed. In songs belonging to this type every five- or seven-syllable text clause forms one phrase of one hyperbar length, with no more than two syllables per beat. Five-syllable clauses end with a long note that falls on the big time. Only the last text clause, consisting of seven syllables, is extended to two hyperbars, because seven syllables in one hyperbar do not allow a melodic closing formula. A song entirely composed in this simple style has thus one hyperbar more than the text has clauses.Footnote 47

Although this syllabic style prevails in ‘Hana tachibana’, the fourth clause, ‘hana tachibana wa’, extended to two phrases (bars 13–20), is an exception. In fact, this exception was necessary to allow a wagon pattern of more than one hyperbar length, as otherwise the song would have had a length of seven hyperbars, which is a prime number. By augmenting the song to eight hyperbars the composer makes a four-hyperbar wagon pattern possible. Incidentally, the composer makes a virtue of necessity, because by prolonging the note values in ‘hana tachibana wa’ he gives emphasis to the beautiful words that gave the song its title.

In contrast to the other two songs, for ‘Hana tachibana’ we do not know whether the melody or the accompaniment was composed first, or whether the two were composed together. The fact that both halves of the song are very similar in bars 3–10 and 19–26 makes it probable that the composer either composed the accompaniment first or was at least aware that the two sections would need a common accompaniment when he composed the melody.

The basic rhythm of the wagon accompaniment – tones on the first and second beat and an arpeggio on the third beat – is very common in gagaku songs. The accompaniment is thus divided into four sections. The first section starts from the key tone (kyū) and ends on the fifth (chi), the second is an intensified repetition of the first section, the third section proceeds from the fifth to the key tone, and the last section confirms the key tone.

The wagon plays almost in unison with the melody in bars 3–12. Since the first two bars of the accompaniment are not played in the beginning, the listener can recognize good congruence between melody and accompaniment from the beginning to the first break in the melody. In bars 13–16, however, there is a great discrepancy between melody and accompaniment, so that the confirmation of the tonality in the accompaniment loses its effect. This is important to maintain the musical tension. Thereafter, the complete congruence of melody and accompaniment in bars 17–20 has a very strong effect. It is the expressive climax of the song. The divergence between melody and accompaniment in bars 25–28 is important to prepare the final cadence. In bars 29–32, the wagon supports the melody, which closes with the formula that is most common in gagaku songs for a full cadence.Footnote 48

In an analysis of a Western song one would perhaps describe the function of melodic motives, as for example the movement B – D – E and its inversion A – F♯ – E, for the musical form, but that would be less appropriate for the analysis of a gagaku song, since all melodic movements that are used in this song are ubiquitous in gagaku songs and thus not characteristic of this particular song. It is rather the relationship between accompaniment and melody – the change between congruence and divergence – which creates the individual form of a gagaku song.

‘Shirogane’ [

, ‘Silver’]

, ‘Silver’]

The words of this song are as follows:

Shirogane mo / koganeFootnote 49 mo tama mo / nani sen ni

masareru takara / ko ni shikame ya mo / utsukushiki ko ni

Translated clause by clause:

Silver / gold and jewels / what are they for?

The greatest treasure / can it be equal to a child / to a beautiful child?

The text was originally a tanka by Yamanoue no Okura (660–733), but the last clause was added by the compiler of Hoiku shōka (see note 44). The song is dated 9 April 1878, and was composed by Shiba Fujitsune (1849–1918).Footnote 50 Together with ‘Kiku no kazashi’Footnote 51 it was the first song in Hoiku shōka to re-use the wagon pattern of another song.

Although through the addition of a seven-syllable clause the text acquired exactly the same form as ‘Hana tachibana’, and it would thus be possible to sing the words with the melody of ‘Hana tachibana’ by replacing the syllables one by one, Shiba has chosen to make the song four hyperbars longer, and, except for the first clause,Footnote 52 he does not use the simple syllabic style we have seen in ‘Hana tachibana’.

The concept of melodic and tonal cadences in ‘Shirogane’ is similar to that in ‘Hana tachibana’, since Shiba sets melodic cadences congruent to the wagon accompaniment in the third hyperbars of the first and second wagon cycle (bars 9–12 and 25–28), but divergent melodic movements in the following hyperbars. Since the second cadence in bars 25–28 is not congruent to a text clause ending, it is the weakest cadence of all, and does not entirely break the tension towards the climax of the song. In the last sixteen bars of the song, the composer sets two exceptionally long phrases. The last phrase begins and ends in congruence with the accompaniment.

Exceptional in this song is also the use of the voice registers for the expression of the words. The parts of the song that belong to the disesteemed silver, gold and jewels use mainly the lower register, and the parts belonging to the highly esteemed child use firstly the middle and then the high register. The use of the upper mordent tsuku on the high tones gives an additional emphasis. An expressive highlighting of whole phrases is exceptional in Hoiku shōka.

Although ‘Hana tachibana’ and ‘Shirogane’ share some very similar passages (bars 6–15 of the former, for example, are almost identical with bars 22–31 of the latter), the overall impression of the two songs is very different, and it can be said that the experiment of composing a new song to the old accompaniment has worked well in this case.

‘Kashima no kami’

The poem is a tanka by Ōtoneri no Chifumi (eighth century):

Arare furuFootnote 53 / Kashima no kami o / inoritsutsu

sumera mikusani / ware wa kinishi o

Translated clause by clause:

To [hailing]Footnote 54 / Kashima's deity / praying

As a warrior of the Emperor / I came!

The song was composed by Tōgi Takekata (1855–?) and is dated August 1878.Footnote 55 ‘Kashima no kami’ is the most melismatic of the three songs analysed here, with the same length as ‘Shirogane’, but only five text clauses. In bars 25–38, a principle of text distribution is observed that is more common for slow metres: each syllable has the length of two times. As is often the case in passages that follow this principle, the phrasing becomes independent of the musical metre, so that after bar 25 the caesuras are incongruent with the hyperbars.

The composer uses many melody fragments from ‘Hana tachibana’ as well as ‘Shirogane’. Bars 9–16, for example, are a transposition of bars 41–48 of ‘Shirogane’, bars 17–24 are almost identical to bars 1–8 of ‘Hana tachibana’, and the ending is the same as in ‘Shirogane’. Nevertheless, the formal concept of ‘Kashima no kami’ is very different from both other songs.

The difference is most obvious if we look at the melodic cadences on the key tone in the three songs. As described in the above analyses, the two previous songs make use of the two cadences of the wagon pattern and synchronize the interim cadences (bars 9–12 in ‘Hana tachibana’ and bars 9–12 and 25–28 in ‘Shirogane’) with the first, and the final cadence with the second. Furthermore, the interim cadences use the weaker formula of simple movement down to the key tone, and only the final cadence uses the strong formula of movement a step down from and then back to the key tone. So there is a clear distinction between ‘half’ and ‘full’ melodic cadences. In ‘Kashima no kami’, in contrast, there are three strong melodic cadences (in bars 13–16 and 27–30 and the final cadence), and none of them is congruent to the first cadence of the wagon.

The first 16 bars of ‘Kashima no kami’ are a musically closed section, symmetrically divided in a two-hyperbar solo and a two-hyperbar tutti. The former is further divided in two phrases, both closing with the key note, and the latter closes with a full cadence, congruent to the final cadence of the wagon pattern. The tension at this point is maintained only by the text, since the musical cadence falls in the middle of a text clause. (The clause endings are indicated by slashes in the transnotation. In the original notation, the clause endings are indicated by small circles between the text syllables.)

The five- and seven-syllable clauses are important for the structure of gagaku songs. As it can be observed in ‘Hana tachibana’ and ‘Shirogane’, a phrase can be identical with a text clause, but a text clause can also be divided into several phrases. However, a phrase does not extend beyond the end of a text clause.Footnote 56 That means that even if a clause is divided into several phrases, the end of the clause conveys a certain feeling of completion, and if a melodic and tonal cadence falls in the middle of a text clause, its closing function is reduced. In ‘Shirogane’ the difference between the first cadence (bars 9–12), which marks a clause ending, and the second one (bars 25–28), which falls in the middle of a clause, contributes to the consequent lead-up to the climax.

In ‘Kashima no kami’, where strong melodic cadences break the flow of the melody twice, it is very important that they are not congruent to the clause structure of the text. The second cadence (bars 27–30) is even ‘out of phase’ with the rhythm of the wagon. The strong rhythmic dissonance motivates the melodic climax in the last two text clauses, and it is not resolved until the very last phrase. It thus seems that the composer intentionally followed a very strict concept of rhythmic symmetry in the beginning – rather unusual for a gagaku song – to make the rhythmic dissonance in the second half more effective.

Conclusion

As seen in the three short examples, musical analysis of gagaku songs can reveal structural differences between particular songs and show aesthetic qualities of individual pieces. For such an analysis, however, it is necessary to know the constraints and conditions under which the process of composition operated. While the melodic shape of the gagaku songs shows almost no individuality, and the formal structures are rigidly regulated by collective processes, the interplay between the diverse rhythmic, tonal and melodic elements, namely the text clause structure, the rhythmic and tonal shape of the wagon accompaniment and the phrases and cadences of the melody, shows a great variety of individual solutions. Musical tension is produced and resolved mainly by incongruence and congruence between these elements. Since the clause structure is essentially asymmetrical, and the musical structures are symmetrical, the composer was forced to search for solutions to bring these elements together.

There remain a great number of unresolved questions: Which of the structural features shown in our analysis are generally used or widespread in gagaku songs, which are restricted to a certain period or certain composers, and which are specific to one or a few songs? Which compositional techniques are learnt from traditional music genres, especially traditional gagaku, or from the reception of non-traditional music, and which techniques are newly developed? Did the individual musical structure of certain gagaku songs have any direct influence on later gagaku songs or on compositions beyond that genre? Are there related techniques in pieces of other music genres around the same time?

Melodic, rhythmic and harmonicFootnote 57 congruence and incongruence between voice and instrument seem to be of general importance for the composition of gagaku songs. Although the specific usage of ostinatos seen in gagaku songs is not found in other genres of modern Japanese music (not even in many of the songs that belong to the gagaku song genre in a wider sense), congruence and incongruence as a general principle is also a valid concept for many other genres of Japanese music and the music of other Asian cultures. In a certain sense, this principle is the ‘heterophonic’ equivalent to consonance and dissonance in polyphonic or homophonic music.

Obviously, it is tempting to find here an ‘Asian’ approach to composition that is fundamentally opposed to the Western approach. This fundamental opposition, however, would not long stand in a broader investigation of the modernization process in Japanese music. Just as it is questionable whether the music of Debussy or Scriabin can be subsumed under the Western concepts of polyphony and homophony, in a majority of modern Japanese compositions, whether they emerged from a traditional or a Western background, it is difficult to draw a definite line between polyphonic and heterophonic techniques. The very temptation to draw such a line reflects our tendency to fall back on the binary opposition of ‘Western’ modernity and ‘Asian’ tradition, and thus to neglect modernization in traditional culture. Although consciousness of tradition and demarcation against the ‘other’ is also a phenomenon of modernity, the question of whether heterophonic or polyphonic techniques are used is, at least aesthetically, less interesting than the question of how they are used. Focusing on this last question we will not have ‘one’ heterophony and ‘one’ polyphony, but a field with a great variety of possibilities. And the composer creating within this field will not appear primarily as an ideologist belonging to a certain school or stylistic tendency, but as an individual working on real solutions for real problems.

To come back to our three songs, we do not know why the court musicians at a certain moment decided to compose songs with a shared accompaniment and why they later abandoned this practice, but the existing examples are especially interesting for musical analysis, since it is clear that these songs have a very close intertextual relationship. In a situation where very similar melodies would have been the most obvious solution, the two composers who added their composition to the first one apparently struggled to find clearly distinctive musical structures. The use of the same accompaniment for all three thus does not reflect a lack of independent originality, but was a measure to perform the difference more visibly, and it is almost impossible to imagine that this difference came about other than by a conscious act of will.

Without question the history of gagaku songs – though short – can be written as a story of solving compositional problems, and the resulting musical structures are interesting documents of musical creativity shortly after the Meiji Restoration.

I thank Professor Tom Gally from the Department of Language and Information Sciences of the University of Tokyo for the careful review of my manuscript.