Introduction

Currently over five million persons in the United States are affected by some form of cognitive impairment including mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (hereafter referred to as “persons with dementia” or PWD). This number is anticipated to grow to 13–16 million by 2050 (Hebert et al., Reference Hebert, Weuve and Scherr2013; Alzheimer's Association, 2020). While in the advanced stages of dementia patients often live in long-term care facilities, a growing number of PWD are living in the community due to person/caregiver preferences and a growth in non-institutional support by Medicaid (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Ritchie and Patel2019). Even those with early to moderate disease can require significant help from informal family caregivers, and the burden on family caregivers is well documented (Chiao et al., Reference Chiao, Wu and Hsiao2015).

Pain is a common, undertreated, and often disabling condition in PWD that impacts both the person and their caregivers (Shega et al., Reference Shega, Hougham and Stocking2006; Achterberg et al., Reference Achterberg, Pieper and van Dalen-Kok2013; Hoffmann et al., Reference Hoffmann, van den Bussche and Wiese2014; Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Covinsky and Yaffe2015). Nearly two-thirds of PWD report bothersome pain (Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Covinsky and Yaffe2015). For PWD, pain may cause substantial distress, adversely impact quality of life, and be associated with physical disability and neuropsychiatric dysfunction that manifests as agitation and aggression (Bradford et al., Reference Bradford, Shrestha and Snow2012; Pieper et al., Reference Pieper, van Dalen-Kok and Francke2013; Corbett et al., Reference Corbett, Husebo and Achterberg2014; Husebo and Corbett, Reference Husebo and Corbett2014). Pain also increases stress for family caregivers who are themselves at risk for adverse mental and physical health outcomes (Chiao et al., Reference Chiao, Wu and Hsiao2015).

To date, the overwhelming majority of literature on pain evaluation and management in PWD focuses on those with advanced disease living in long-term care facilities (Pieper et al., Reference Pieper, van Dalen-Kok and Francke2013; Husebo et al., Reference Husebo, Achterberg and Flo2016). Given the prevalence of pain in community-dwelling patients with less advanced disease, and the impact of pain on patients and caregivers, it is important to develop relevant pain management programs that target these vulnerable individuals. Nonpharmacological approaches for pain management, particularly those based on cognitive behavioral principles such as pain coping skills training (PCST), have been found efficacious among older adults without dementia (Keefe et al., Reference Keefe, Porter and Somers2013; Niknejad et al., Reference Niknejad, Bolier and Henderson2018). While they have been recommended for PWD (Norelli and Harju, Reference Norelli and Harju2008; Keefe et al., Reference Keefe, Porter and Somers2013), to our knowledge, there have been no methodologically rigorous trials examining the efficacy of PCST in this population. Systematically involving both patients and family caregivers in PCST is a novel approach that may benefit both patients and caregivers. We have previously developed and tested caregiver-assisted PCST protocols for patients with osteoarthritis and cancer and have found they lead to improvements in outcomes for both patients and caregivers (Keefe et al., Reference Keefe, Caldwell and Baucom1996, Reference Keefe, Caldwell and Baucom1999, Reference Keefe, Ahles and Sutton2005). The goal of this study was to develop a new caregiver-assisted PCST protocol specifically tailored for community-dwelling PWD and pain and assess its feasibility and acceptability. In Phase I of the project, we conducted interviews with patients and caregivers to help develop and refine the protocol. Phase II was a single-arm pilot test to evaluate the intervention's feasibility and acceptability.

Method

Eligibility and recruitment procedures were identical for Phase I and Phase II. Participants in Phase I were not eligible for Phase II. Patients were recruited from the Duke Memory Disorders and Geriatric Evaluation and Treatment Clinics. Patient inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of MCI or mild to moderate dementia (as documented by their physician), score ≥3 on the PEG, and living at home with an informal caregiver. The PEG consists of three items (pain severity, interference with enjoyment of life, and interference with general activities, each rated from 0 to 10) which are averaged for a composite score. Additional inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years and English speaking (both patients and caregivers). Exclusion criteria were inability to complete study activities (e.g., due to hearing impairments or severe behavioral problems) as determined by the patient's healthcare provider or reported by the caregiver.

All study procedures were approved by the Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board (IRB). Potential participants were introduced to the study by the patient's healthcare provider verbally or by an IRB-approved introductory letter. This was followed by a telephone call from research staff to provide information, answer questions, and determine eligibility, including administration of the PEG. For those who were eligible and interested, a visit was scheduled to complete informed consent and conduct the interview (Phase I) or collect baseline measures (Phase II). Due to COVID-19 restrictions on in-person research activities instituted in March 2020, all study activities were conducted remotely after this time.

Caregivers were consented using a standardized IRB-approved protocol and completed written consent. Rather than assess patients for competency to provide consent, we operated under the assumption that patients may lack decision-making capacity and obtained assent (written and verbal) from the patient and consent from the caregiver (who in each case was the patient's legally authorized representative).

Phase I: Refinement of intervention

We collected demographic information from patients and caregivers and then conducted a 45-min interview in which we presented information about the intervention to dyads and elicited their feedback using a standardized interview guide. The interviewer described and/or demonstrated five pain coping skills (see Table 1) and elicited feedback about each. Participants were also asked about their preferred mode of intervention delivery (e.g., in person versus remotely by telephone or videoconferencing, and participating individually or together with their partner). Patients and caregivers each received $40 for completing the interview.

Table 1. Pain coping skills presented in the interviews

Interview data were managed and evaluated in a systematic format (Hsieh and Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005). Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed as they were conducted. Recordings and transcriptions were reviewed by the study team and analyzed using thematic content coding (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). After 10 interviews, we determined we had reached thematic saturation. To assess and categorize the valence of responses regarding perceptions of the pain coping skills, two coders (L.S.P. and K.R.) independently rated each dyad's responses to each of the skills as negative, neutral (or equally positive and negative), or positive. Ratings were consistent for 43/50 responses (86%), and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. We used these formative data to adapt and refine the intervention.

Phase II: Pilot study

Dyads in the pilot study completed baseline surveys, received five intervention sessions, and then completed post-intervention surveys. Originally, surveys were conducted in person via paper and pencil. Following implementation of pandemic restrictions, participants completed surveys at home either electronically or on paper, via mail. Patient medical information was collected via medical chart review. Patients and caregivers received a total of $100 each.

Measures

At baseline, patients and caregivers provided demographic information and caregivers completed a measure of comorbidities (Sangha et al., Reference Sangha, Stucki and Liang2003).

Feasibility was assessed through caregiver reports of coping skills use throughout the intervention period and post-intervention. At the start of sessions 2–5, caregivers reported the frequency of their practice of skills taught at the previous session. They also rated the perceived helpfulness of the skills and their confidence in using the skills (on a scale from 0 = “not at all helpful/confident” to 4 = ”extremely helpful/confident”). At the post-intervention survey, caregivers completed a measure assessing the frequency with which they used each skill during the past week and their perceptions of the skills’ ease of use and helpfulness (on a scale from 0 = “not at all easy to use/helpful” to 4 = ”extremely easy to use/helpful”).

Acceptability of the intervention was measured with the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Attkisson and Stegner1983) which assesses the effectiveness of/satisfaction with services received. Caregivers completed this scale at post-intervention only. Additional items were added to assess satisfaction with the number and length of sessions, preference for treatment modality (in person/videoconference/telephone), and aspects of the intervention they found most/least helpful (open-ended).

Patient pain and functioning was assessed via patient self-report and caregiver proxy reports completed at baseline and post-intervention. Patients completed four items from the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) (Daut et al., Reference Daut, Cleeland and Flanery1983): usual, average, and worst pain intensity rated on a 0–10 scale, and pain interference rated 0 (none) to three (extreme). The BPI has demonstrated reliability and validity (Daut et al., Reference Daut, Cleeland and Flanery1983). The three pain intensity items were averaged; Cronbach's alpha was 0.77. Patients also competed the Quality of Life in Alzheimer's Disease (QOL-AD) (Logsdon et al., Reference Logsdon, Gibbons and McCurry2002), a 13-item dementia-specific quality of life scale. The measure has good psychometric properties and can be completed by people with a wide range of severity of dementia. Cronbach's alpha was 0.83.

Caregivers completed proxy measures of the QOL-AD scale and the five-item pain interference scale from the BPI. Cronbach's alpha was 0.88 for the QOL-AD and 0.90 for pain interference. Caregivers also completed the Checklist of Nonverbal Pain Indicators (Feldt, Reference Feldt2020) which assesses pain behaviors (e.g., moaning, wincing, bracing) in cognitively impaired older adults. Scores range from 0 to 10 with higher scores indicative of more pain expression.

Caregiver outcomes. Caregivers completed the following measures at baseline and post-intervention:

Caregiver self-efficacy was measured using the pain management subscale of a standardized measure that assesses caregiver self-efficacy for helping the patient manage symptoms. This subscale includes seven items worded as questions and rated on a 10–100 scale (e.g., “How certain are you that you can help the patient control his/her pain?”). Items are averaged. Prior studies support the scale's reliability and validity (Lorig et al., Reference Lorig, Chastain and Ung1989; Keefe et al., Reference Keefe, Ahles and Sutton2005; Porter et al., Reference Porter, Keefe and Garst2011). Cronbach's alpha was 0.95.

Caregiver burden was measured with the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) (Zarit et al., Reference Zarit, Reever and Bach-Peterson1980), a 22-item scale assessing burden experienced by dementia caregivers in the home care context. The ZBI has high internal consistency and good test–retest reliability. (Hérbert et al., Reference Hérbert, Bravo and Préville2000) Scores range from 0 to 88 with higher scores indicating greater burden. Cronbach's alpha was 0.95.

Caregiving satisfaction was measured using the Caregiving Satisfaction scale of the Caregiver Appraisal measure (Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, Kleban and Moss1989) which assesses benefits associated with caregiving (e.g., feeling closer to the patient). The scale has demonstrated good test–retest reliability and internal consistency. (Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, Kleban and Moss1989) Cronbach's alpha was 0.74.

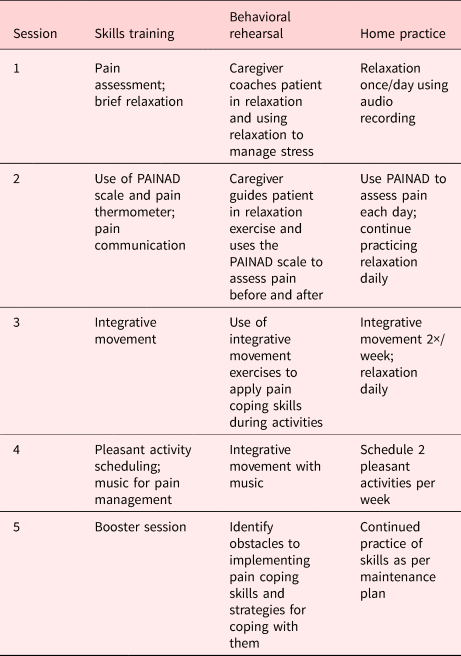

Intervention

The caregiver-assisted PCST protocol consisted of five 45–60 min sessions conducted jointly with the patient and caregiver (Table 2). The first four sessions were intended to occur weekly, but participants were given up to eight weeks to complete these sessions to accommodate factors such as travel and illness. The last session was a booster session that occurred 1 month following the fourth session. Based on findings from the interviews, we planned to conduct the first session in person and then give dyads the option of completing the remainder of the sessions either in person or remotely via telephone or videoconference. Starting in March 2020, all sessions were conducted remotely due to pandemic-related restrictions on in-person research activities.

Table 2. Intervention content

Sessions were conducted by a master's level social worker experienced in PCST and working with older adults. At the outset of the study, the therapist received training in the protocol. She followed a detailed treatment manual, and sessions were audio recorded and reviewed in supervision sessions with the first author. Sessions included training in four skills presented in the interviews (PAINAD, brief relaxation, integrative movement, and pleasant activity scheduling) plus the pain thermometer for patient reports of pain severity and music as a specific pleasant activity that can help with pain management (McConnell et al., Reference McConnell, Scott and Porter2016).

Statistical analyses

Analyses of the pilot data focused on feasibility and acceptability. Feasibility was assessed by examining overall accrual, attrition, and adherence to the study protocol. To evaluate accrual, we describe the total number of patients and caregivers screened and rates and reasons for non-eligibility and refusal. With regard to attrition and adherence, we examined the number of dyads who successfully completed study participation (i.e., provided post-intervention assessments); completion by 70% served as our feasibility benchmark. We examined caregiver use of skills and their perceived helpfulness and ease of use. Acceptability was assessed by post-intervention ratings of satisfaction with the intervention, with a benchmark of 70% of caregivers reporting satisfaction with the intervention (mean score of 3 on the four-point CSQ). Finally, we examined individual baseline to post-intervention difference scores on outcome measures and describe the pattern of changes observed. As recommended by guidelines for pilot studies with small sample sizes (Kraemer et al., Reference Kraemer, Mintz and Noda2006; Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Lancaster and Campbell2016), we did not conduct statistical tests of change scores.

Results

Phase I: Interviews

Ten patient–caregiver dyads completed the interviews. Patients’ mean age was 77.7 years (SD = 6.8, range = 67–87), 70% were female, and 80% were non-Hispanic white. Patient diagnoses included MCI (n = 3), AD (n = 5), mild dementia (n = 1), and mixed AD/vascular dementia (n = 1). Caregivers’ mean age was 73.7 years (SD = 11.3, range = 52–89), 40% were female, and 80% were non-Hispanic white. Eight caregivers were spouses and two were daughters of the patient.

Interview data are summarized in Table 3. All ten dyads responded positively to the relaxation exercise. After the interviewer guided them through the practice, many noted that it helped reduce stress, tension, and pain, and was definitely a skill that would be useful. All ten dyads also responded positively to pleasant activities; dyads participated enthusiastically in the process of identifying enjoyable activities and left the interview with plans for engaging in activities meaningful to both the patient and caregiver. Some noted that the patient's condition posed challenges to engaging in activities they previously enjoyed (e.g., playing cards), and that more recently the COVID-19 pandemic limited many of their usual activities. However, they recognized the importance of finding creative ways to engage in pleasant activities as a way of reducing patient isolation and improving both patient and caregiver mood as well as managing pain. Nine of ten dyads commented positively on the PAINAD tool, noting that it would be useful in helping them assess the patient's pain and communicating this information to healthcare providers; one dyad responded neutrally to the tool (e.g., “It makes sense”). Eight dyads had positive responses to the integrative movement exercises which they thought would be fun and encourage physical activity. Two were neutral, noting that while the exercises could be beneficial, they did other physical activities which they preferred (e.g., riding a stationary bicycle). In reaction to the activity-rest cycle, six dyads had mostly positive comments, and four had mixed positive and negative comments. While most participants believed that the skill was beneficial, many reported that at this point in their lives they had learned to do this on their own.

Table 3. Ratings and quotes from Phase I patient–caregiver interviews

In addition, some caregivers commented that the way in which patients and caregivers would learn and apply skills would depend to some degree on the severity of the patient's cognitive impairment. For example, one caregiver noted that integrative movement would need to be introduced early in the disease trajectory for the patient to be able to follow along. Another noted that relaxation would need to be started in the earlier stages, “then you don't know how long it will stay, but if they're doing it together it may work.”

With regard to format and mode of delivery, all 10 dyads responded positively to the plan to conduct sessions weekly with the patient and caregiver together, noting that this format was likely to be the most effective way for them to learn and apply the skills. Half of the dyads preferred that sessions be conducted in person at the clinic, noting that they often needed a reason to get out of the house and that they were more likely to give their undivided attention in this setting. However, one dyad stated they would be most comfortable having the sessions at home, and several did not have any strong preferences. The idea of videoconferencing was met with mixed responses; several dyads stated definitively that they did not like using technology, several others were skeptical but open to the possibility, and two caregivers noted that they would prefer videoconferencing for its convenience and flexibility.

Conducting these interviews also provided useful information that helped shape decisions about the content and process of the intervention sessions. Patients exhibited fluctuations in their ability to comprehend skills and were often only able to focus on a topic for a short time. This suggested the importance of keeping the content simple (i.e., one skill per session), limiting the number of skills included, emphasizing home practice to consolidate learning, and including strategies for maintenance enhancement. The fact that dyads had different needs and preferences with regard to location and mode of delivery suggested the importance of allowing dyads to participate either in person or remotely.

Based on these findings, we decided to offer five sessions with the first four scheduled weekly to promote continuity and a booster session 1 month later to trouble shoot and promote maintenance. Given the need to limit the number of coping skills included in the intervention, we decided to exclude the activity-rest cycle which received the fewest favorable responses.

Phase II: Pilot study

Feasibility. Thirty-one patients were approached for participation. Of these, 15 were ineligible (no pain, n = 10; pain but PEG score <3, n = 1; patient living in assisted living/memory care, n = 2; patient not living with caregiver, n = 1; patient did not speak English, n = 1). Of the 16 eligible dyads, 5 declined to participate. Reasons included patient or caregiver lack of interest (n = 3), distance (n = 1), patient being too ill (n = 1), and being too busy (n = 1).

Eleven dyads consented and provided baseline data. Patients’ mean age was 77.7 years (SD = 4.8, range = 71–84); 70% were non-Hispanic white. Patient diagnoses included MCI (n = 5), AD (n = 3), unspecified dementia (n = 2), and Parkinson's related dementia (n = 1). Pain diagnoses included knee or hip osteoarthritis (n = 6), chronic low back pain (n = 6), headache (n = 1), sciatica (n = 1), unspecified foot pain (n = 1), and back/leg pain from a gunshot wound (n = 1). Caregivers’ mean age was 69.6 years (SD = 13.3, range = 43–83); 91% were non-Hispanic white. Eight caregivers (73%) were spouses, two were daughters, and one was the sister of the patient. Two caregivers were employed full-time and nine were retired. Caregivers reported an average of 3.9 medical conditions, the most common being back pain (n = 8), high blood pressure (n = 4), and depression (n = 4).

Nine dyads (82%) completed all five sessions on schedule (within 10 weeks). Two dyads completed three sessions, one dropping out due to the caregiver's work schedule and the patient's declining health and the other because they did not find the skills helpful. Two dyads completed all of the sessions in person, four completed at least one session in person and the remainder by telephone, and five completed all sessions by telephone. All eleven dyads completed post-treatment questionnaires.

During the course of the intervention, almost all of the caregivers reported practicing the skills taught in the previous session at least once or twice, with the majority of caregivers practicing each of the skills three or more times per week (see Table 4). The exception was the pain thermometer which was used by only three caregivers. Average ratings of helpfulness ranged from 1.6 (a little bit to somewhat helpful) for the pain thermometer to 3.6 (very to extremely helpful) for pleasant activities. The PAINAD scale and music were also rated as very to extremely helpful. Caregivers reported high levels of confidence in using the PAINAD, pain thermometer, pleasant activities, and music (3.4–3.8, very to extremely confident). Relaxation for stress management was rated as very helpful, although confidence in using relaxation was low (1.4, a little bit to somewhat confident).

Table 4. Weekly reports of skill use, helpfulness, and confidence

a Range = 0 (not at all easy/confident) to 4 (extremely easy/confident).

b One item assessed confidence in using relaxation for both pain and stress.

After completing the intervention, most caregivers reported continued use of the skills at least once or twice in the preceding week (see Table 5). Most skills were rated as somewhat to quite a bit easy to use. Pleasant activities and music were rated as quite a bit to extremely helpful, with other skills rated as somewhat to quite a bit helpful.

Table 5. Caregiver post-assessment reports of skill frequency use, ease of use, and helpfulness over the past week

a Range = 0 (not at all easy to use/helpful) to 4 (extremely easy to use/helpful).

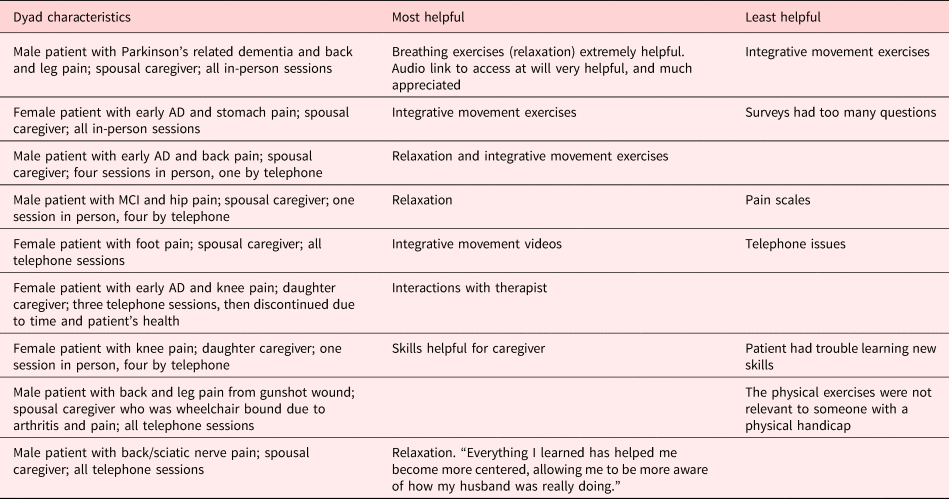

Acceptability. Caregivers reported a mean satisfaction score of 3.4 (SD = 0.35, range = 3.0–4.0). Eight caregivers said the number of sessions (five) was about right; one said it was too few and one said it was too many. Nine caregivers said the length of the sessions (45–60 min) was about right; one said they were too long. Five caregivers reported that they would prefer participating by telephone, three preferred videoconference, and two preferred in-person sessions. Comments about the most and least helpful aspects of the intervention are shown in Table 6. One caregiver did not complete this measure.

Table 6. Comments in response to open-ended questions about the most and least helpful aspects of the intervention during Phase II pilot-testing

Patient pain and functioning. Means on baseline and post-intervention measures and average difference scores are displayed in Table 7. On average, patients and caregivers reported decreases in patient pain severity and interference from baseline to post-intervention. Patients reported slight decreases in their QOL while caregivers reported slight increases in their perceptions of patient QOL.

Table 7. Scores on baseline and post-intervention measures

Caregiver outcomes. There were notable variations in baseline levels of caregiver self-efficacy for helping the patient manage pain, with some caregivers reporting high levels of confidence and others reporting very low levels. Overall, they reported small increases in self-efficacy, increases in caregiver burden, and decreases in caregiving satisfaction. There were large ranges of change on each of these variables.

Discussion

The aims of this study were to adapt a caregiver-assisted PCST intervention for PWD and their family caregivers and assess its feasibility and acceptability. Findings supported the feasibility of this approach. Eleven of 16 (69%) eligible dyads consented to participate in the pilot study, 82% of dyads completed all five intervention sessions, and caregivers reported high satisfaction ratings. Importantly, caregivers reported that they used the pain coping skills on a regular basis, and that they found most of the skills helpful and easy to use.

The most helpful and frequently used skills were pleasant activity scheduling and listening to music, while the least helpful/used skill was the pain thermometer. Many caregivers noted that the pain thermometer was not necessary in the context of MCI or mild dementia as the patients were readily able to verbalize pain. Interestingly, while relaxation and integrative movement exercises were not as highly rated as others on the quantitative surveys, they were most frequently mentioned as helpful in response to the open-ended item on the post-intervention survey. With regard to relaxation, many caregivers found it helpful for managing their own stress, however they may not have had enough time to practice it to develop their confidence in using it effectively. For integrative movement, there tended to be a bimodal response; participants who were already physically active and those who had significant physical limitations were less likely to find it helpful than those who were more sedentary but able to engage in the exercises.

The pattern of changes on outcome variables was mixed. Patients and caregivers reported decreases in patient pain severity and interference from baseline to post-intervention, and caregivers reported increases in their self-efficacy for helping the patient manage pain. However, caregivers reported increases in burden and decreased caregiving satisfaction. These difference scores should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size, large ranges, and lack of control group. While it is possible that caregivers experienced the study protocol as burdensome, only a small minority reported any burden associated with the study. Findings likely were influenced by the fact that most of the dyads participated in the study during the early months of the pandemic when caregivers may have been experiencing increased stress.

The pandemic also significantly impacted the implementation of the study. Consenting patients and caregivers and collecting data remotely was challenging and time-consuming. Many caregivers were unable to complete these activities via internet, thus we often had to mail materials and provide instructions by telephone. Also, during the interviews and at the onset of the pilot trial, many if not most dyads reported a preference for participating in the intervention in person. While caregivers who participated by telephone reported satisfaction with this format, we believe that they may have derived more benefit from having at least some in-person (or even videoconference) sessions so that the therapist could better evaluate their engagement, model skills, and provide feedback.

Lessons learned from this pilot study include the potential importance of including a qualitative assessment of caregivers’ reactions to the intervention to better understand their experiences. For example, anecdotally caregivers noted increases in positive interactions over the course of the sessions (e.g., rediscovering mutually enjoyable activities) that may not have been captured in quantitative surveys. Based on caregivers’ favorable responses to the relaxation exercise combined with relatively low levels of confidence in applying this skill, we believe that caregivers might benefit from having one or more initial individual sessions (without the patient) focused on relaxation. By first learning to use relaxation to manage their own stress and pain, caregivers may be better prepared to assist the patient in learning and applying the pain coping skills. We plan to incorporate these elements in a subsequent larger randomized controlled pilot study.

Additional limitations of the study include the small sample size, lack of comparison group, and no long-term follow up. Nonetheless, these preliminary findings suggest that a caregiver-assisted pain coping skills intervention is feasible and acceptable, and that it may be a promising approach to managing pain in patients with cognitive impairment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Laura Fish, Ph.D., Margaret Falkovic, M.S.W., Kathy Ramadanovic, and Emily Patterson, L.C.S.W., for their assistance with the study, as well as the participants who contributed their time and effort.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by a grant to the first author from the National Palliative Care Research Center's Pilot Projects Support Grants Program. Dr. Schmader also received support from NIA P30AG028716 (Pepper Older Americans Independence Center).

Conflicts of Interest

D.E.B. is co-inventor of the Preventing Loss of Independence through Exercise (PLIÉ) program and has the potential to earn royalties. The following authors have no conflicts to report: L.S.P., D.K.W., K.E.S., K.R., L.G., C.S.R., and F.J.K.