1 Introduction

The lateral approximant shows allophonic variation in many accents of English, exhibiting a light [l] prevocalically (as in leaf and feeling), and a dark [ɫ] postvocalically (as in help and feel). Darkening of /l/ has typically been regarded as an example of lenition in the literature because it applies in positions (preconsonantal and word-final) that are traditionally viewed as weak. In addition, in some systems dark [ɫ] can weaken further and vocalise to [ʊ].

In this article, I analyse these processes in a recent version of Government Phonology, employing CV-representations (Lowenstamm Reference Lowenstamm, Durand and Laks1996) and monovalent elements (Backley Reference Backley2011). Lenition processes have been analysed in this approach as involving loss of elements in weak positions. However, it is not clear how velarisation can be characterised as element loss if light [l] is represented as |A I|, while dark [ɫ] is represented as |A U|. Therefore, I propose that laterals in General British English contain both the coronal |I| and the velar |U| element underlyingly (in addition to |A|), but because these elements cannot combine in a compound segment in English, they are both floating. Their association then takes place at the phrase level.

To account for the fact that in systems with alternating /l/ it is always the light variant that surfaces prevocalically and the dark variant postvocalically, I propose to employ the apophonic chain |I| → |A| → |U| → |U| (Guerssel & Lowenstamm Reference Guerssel, Lowenstamm, Lecarme, Lowenstamm and Shlonsky1996) to analyse this phenomenon, originally posited to capture vocalic alternations of the sing ~ sang ~ sung type, where the order of elements also proceeds from front to back. Mapping the apophonic chain on the structure of the syllable, |I| will be attracted to the prevocalic position, |A| to the vocalic position and |U| to the postvocalic position (although this division is not strict, as |A| also occurs in non-nuclear positions). In this approach, thus, darkening does not involve lenition of /l/, but partial interpretation in all positions (whether strong or weak).

I also examine vocalisation of dark [ɫ], which I analyse as lenition, involving loss of |A| (the tongue tip contact) in weak positions, which still shows an effect of the apophonic mechanism, representing the last step in the chain. Finally, I integrate the lateral into the system of glides in English (also including [j w ɹ]), and establish a typology of its behaviour across different accents, showing how it follows from the analysis proposed.

The study reported on in the present article is part of a larger research project analysing various phenomena related to syllable structure in English in a CV-framework: the distribution of stressed vowels (Polgárdi Reference Polgárdi, Botma and Noske2012), syncope and syllabic consonant formation (Polgárdi Reference Polgárdi2015a), and the distribution and behaviour of glides (Polgárdi Reference Polgárdi2015b), to be extended to further issues in the future. While I will briefly introduce the theoretical tools employed in this analysis, detailed motivation for the use of some of these tools can be found in the previous publications (as indicated below).

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the data on the distribution of light and dark /l/ and the morphosyntactic conditioning of /l/-darkening. Section 3 gives a concise introduction to Loose CV Phonology, providing theoretical background for the analysis. In section 4, I introduce Element Theory, and examine the problems posed by an account of darkening in terms of lenition. Section 5 presents the analysis of darkening employing the apophonic chain. In section 6, I turn to vocalisation and the typology of /l/-behaviour in different accents of English. Section 7 summarises the results.

2 /l/-darkening in English

The lateral approximant in General British English (GB), former RP (Cruttenden Reference Cruttenden2014: 217–22), has two realisations: light (or clear), with a front vowel resonance, and dark, with a back vowel resonance. In articulatory terms, the alveolar tip contact is shared by both realisations, but for light [l] the front of the tongue is raised towards the hard palate, whereas for dark [ɫ] the back of the tongue is raised towards the soft palate. Acoustically, the difference is manifested as higher vs lower F2 (Bladon & Al-Bamerni Reference Bladon and Al-Bamerni1976), or as a larger vs smaller difference between F2 and F1 (Turton Reference Turton2014).

The distribution of light and dark /l/ is shown in (1).

(1) Distribution of light and dark /l/

The light realisation occurs when /l/ precedes a vowel or [j], as in (1a–b), whether in the same morpheme or as part of a following suffix or word. It does not matter what the /l/ itself is preceded by (whether a vowel, a consonant, or a suffix/word boundary). Dark [ɫ] occurs when the /l/ appears before a consonant or phrase-finally, as in (1c–d), or when it is syllabic (regardless of what follows), as in (1e).Footnote 2 In addition, dark [ɫ] can be increasingly vocalised to [ʊ], by loss of the tongue tip contact, in Regional GB (e.g. in London).

As illustrated in (1), dark [ɫ] surfaces in the rhyme (i.e. in non-prevocalic position), while light [l] surfaces in the onset, including results of resyllabification of prevocalic word-final consonants. /l/-darkening, thus, applies at the phrase level in GB, following the terminology of a stratal approach (e.g. Bermúdez-Otero Reference Bermúdez-Otero, van Oostendorp, Ewen, Hume and Rice2011). Accents of English, however, show variation with respect to morphosyntactic conditioning of the process, as demonstrated in (2).

(2) Typology of /l/-darkening (Bermúdez-Otero Reference Bermúdez-Otero2007; Turton Reference Turton2014, Reference Turton2017)

In American English 1 (Sproat & Fujimura Reference Sproat and Fujimura1993; Gick Reference Gick, Local and Temple2003), a word-final /l/ no longer ‘sees’ the initial vowel of a following word (as in fee[ɫ] it), indicating that the domain of darkening has narrowed to the word level. American English 2 (Olive et al. Reference Olive, Greenwood and Coleman1993) has moved one stage even further in the life cycle of phonological processes, to the stem level, where word-level suffixes are not visible either for a stem-final /l/, and we get darkening also in examples like fee[ɫ]ing. Finally, in American English 3 (Hayes Reference Hayes, Dekkers, van der Leeuw and de Weijer2000; Yuan & Liberman Reference Yuan and Liberman2009, Reference Yuan and Liberman2011), the prosodic conditioning of darkening is foot-based: it applies everywhere outside a foot-initial onset, that is, it has undergone rule generalisation, and a dark [ɫ] appears in examples like gá[ɫ]a, too (cf. the light foot-initial [l] in belíeve-type tokens).

In addition to domain narrowing and rule generalisation, rule scattering may also appear. In this case, two versions of the same process coexist in the same grammar. This may happen when the stabilisation of a new categorical phonological process leaves the gradient phonetic process from which it has emerged intact. For example, in the American English variety reported by Sproat & Fujimura (Reference Sproat and Fujimura1993), categorical /l/-darkening has moved up to the word level of the grammar. But it is overlaid with a gradient process of phonetic implementation, affecting dark [ɫ]s only, where degree of darkness is dependent on duration of the rhyme (Bermúdez-Otero & Trousdale Reference Bermúdez-Otero, Trousdale, Nevalainen and Traugott2012).

In this article, I deal with the GB pattern, that is, darkening of rhymal /l/ at the phrase level.

3 Loose CV phonology with trochaic proper government

Let me begin with the basic ingredients of the analysis, the underlying assumptions that I adopt. I follow Lowenstamm's (Reference Lowenstamm, Durand and Laks1996) Strict CV approach in the idea that syllable structure consists of strictly alternating C and V positions. As a consequence, the representation of closed syllables, geminate consonants and long vowels involves an empty position, as shown by the hypothetical forms in (3).Footnote 3

(3) Strict CV (Lowenstamm Reference Lowenstamm, Durand and Laks1996)

Geminates and long vowels are built up of two CV units. In a geminate the consonantal melody straddles an empty V position, while in a long vowel the vocalic melody straddles an empty C.

Following Rowicka (Reference Rowicka1999a, Reference Rowickab), I employ trochaic (left-to-right) proper government instead of the more usual right-to-left typeFootnote 4, as defined in (4) (argued for extensively in Polgárdi Reference Polgárdi, Botma and Noske2012, Reference Polgárdi2015a,Reference Polgárdib).

(4) Trochaic (left-to-right) Proper Government (Rowicka Reference Rowicka1999a, Reference Rowickab)

A nuclear position A properly governs a nuclear position B iff

(a) A governs B (adjacent on its projection) from left to right

(b) A is not properly governed

Government is a binary, asymmetric relation between skeletal positions. Proper government, indicated by a curved arrow in (3) and in subsequent diagrams, is a special form of government, which works in conjunction with the Empty Category Principle, given in (5).

(5) Empty Category Principle (ECP) (Kaye et al. Reference Kaye, Lowenstamm and Vergnaud1990: 219)

A position may be uninterpreted phonetically if it is properly governed.

As a result, an empty V position may remain silent if it is properly governed, as shown by V2 in (3a–b) above. According to Rowicka (Reference Rowicka1999a, Reference Rowickab), the relationship between the two halves of a long vowel is also one of proper government, as shown in (3c). Since the C position between V1 and V2 is unfilled, this governing relationship is manifested by spreading the melodic content of V1 into V2. The ECP permits properly governed positions to remain uninterpreted, but it does not demand that they do so. Therefore, the realisation of V2 in (3c) does not contradict the ECP.

Finally, I use a so-called Loose CV skeleton instead of the Strict CV one (as argued for in Polgárdi Reference Polgárdi1998, Reference Polgárdi, Kenesei and Siptár2002). These two approaches are not radically different: word-medially they are the same, they only differ (potentially) at the edges. More precisely, Loose CV dispenses with domain-final empty nuclei that are always inaudible. This means that words do not need to end in a V position: C-final words are allowed (just like V-initial words, when there is no phonetic consonant initially). However, word-medially a strict alternation of C and V positions is still required.

Domain-final empty nuclei present some serious problems, as discussed in Polgárdi (Reference Polgárdi1998). One of the problems is illustrated in (6), where the noun-forming suffix -er is added to the verb listen, resulting in the form listener. In a Strict CV approach, the stem ends in the empty V3, while the suffix starts with the empty C4. This empty sequence is then customarily deleted, indicated by angle brackets; Gussmann & Kaye (Reference Gussmann and Kaye1993) refer to this as the operation of Reduction.

(6) Strict CV: Reduction

This is, however, problematic because it violates the Projection Principle, given in (7), by also removing the proper governing relation between V2 and V3.

(7) Projection Principle (Kaye et al. Reference Kaye, Lowenstamm and Vergnaud1990: 221)

Governing relations are defined at the level of lexical representation and remain constant throughout a phonological derivation.

In a Loose CV approach, as shown in (8), no reduction is necessary, as a consonant final stem and a vowel initial suffix can simply be concatenated. As a result, no governing relationship has been deleted in this analysis.

(8) Loose CV: no Reduction

Note that although -er is a word-level suffix, constituting analytic morphology, there are several arguments for removing the empty structure in a Strict CV analysis. For example, syncope (a word-level process) of the schwa in V2, as in listener [ˈlɪsnə], cannot apply if the following V position is empty, as shown by examples like faculty *[ˈfæklti] (Polgárdi Reference Polgárdi2015a). Another argument is provided by Tapping in New York City English, which is also inhibited by a following empty nucleus: e.g. get [gɛt̚] vs getting [ˈgɛɾɪŋ] and get it [ˈgɛɾɪt] (Harris & Kaye Reference Harris and Kaye1990; Harris Reference Harris1994). /l/-darkening in GB exhibits the same pattern, as shown in (1), providing further support for a Loose CV account, which does not violate the Projection Principle.

4 Is /l/-darkening lenition?

The non-prevocalic positions in (1c–d) (preceding a consonant or a pause), whose Loose CV representations are given in (9), are typical contexts for lenition, suggesting that darkening can be regarded as a weakening process.

(9) Non-prevocalic position (1c–d)

Lenition has been insightfully analysed in Element Theory as decomposition in weak positions (e.g. Harris Reference Harris1990, Reference Harris1997). A C position is weak if it is not followed by a filled V position to support it. In (9a), the V position following C2 is empty (and properly governed), while in (9b), C3 is not followed by a V position of any type. The question is whether darkening can be characterised as element loss.

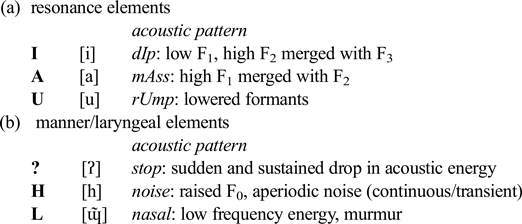

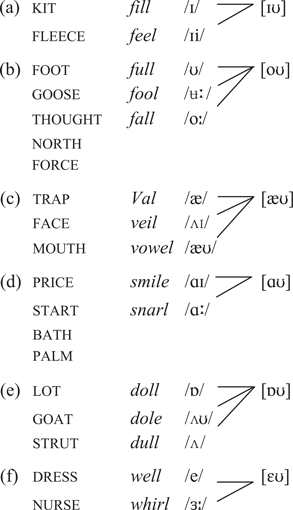

A recent introduction to Element Theory can be found in Backley (Reference Backley2011). In this version, there are three resonance elements and three manner/laryngeal elements, all monovalent, as presented in (10a–b).

(10) Element Theory (Backley Reference Backley2011)

The list in (10) gives the representation of the element in bold, its phonetic interpretation when it constitutes a segment by itself (in a V position in (10a) and in a C position in (10b)), followed by the name of the element in italics, and a brief description of the acoustic pattern it is mapped onto. All elements can occur in both V and C positions, although their interpretation differs depending on the position.

When examining vocalic expressions, the resonance element |I| occurs in front vowels, |A| in non-high vowels, while |U| in rounded vowels. The unmarkedness of the vowels [i a u] is expressed by their simplex nature, that is, that they are made up of a single element. Elements can also combine, resulting in compound expressions, mapping onto composite spectral patterns, comprising the acoustic characteristics of contributing elements. For example, the mid vowel [ɛ] is represented by the compound |A I|, combining the openness of |A| with the frontness of |I|. In addition, following Dependency Phonology (Anderson & Ewen Reference Anderson and Ewen1987), the notion of headedness is also employed. This gives an element acoustic prominence or strength (as in the contrast between [e] |A I| as a lowered front vowel vs [æ] |A I| as a fronted low vowel). As we shall see below, non-headed expressions and expressions with more than one head are also allowed.

Turning to the manner/laryngeal elements, the stop element |?| occurs as non-headed in oral and nasal stops (and affricates) and in creaky vowels, and as headed in ejectives. Non-headed |H| can be found as noise in fricatives and released stops (and affricates), while headed |H| is interpreted as voicelessness or aspiration in languages such as English, where a phonologically active voiceless series of obstruents contrasts with a phonologically neutral series of voiced obstruents lacking a laryngeal property. Conversely, in languages like French, where the phonologically active obstruent series is voiced, this series possesses the headed element |L|, representing voicing, in contrast to the neutral series, again lacking an active laryngeal element. Non-headed |L|, on the other hand, stands for nasality, in both consonants and vowels. In addition to aspiration and voicing in obstruents, headed |H| and |L| in vowels represent high and low tone, respectively.

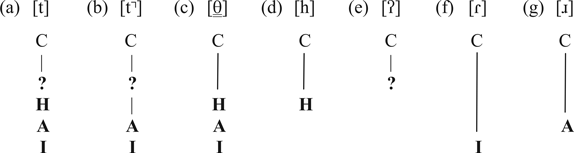

The elemental representation of the English consonant system is given in (11), except for the laryngeal distinction (in terms of headed |H| vs nothing) which will not be relevant for the following discussion.

(11) Representation of consonants in English (exc. [ɫ] |A U|), voicing disregarded

Affricates and stops are treated as phonologically identical, only distinguished by their resonance properties. Place of articulation is defined by the resonance elements, with differences in headedness again representing a difference in the strength of their acoustic cues. The parallelism with vowels is quite clear in the case of headed |U| standing for labials, non-headed |U| for velars, and headed |I| for palatals. The coronal area is more complex, and it also shows more language-specific variation. Palato-alveolars may share a class with palatals or they may be separate, as proposed here, bearing the specification |A I|. Dentals and alveolars may be represented by |I|, |A| or |A I|, depending on their behaviour (where the articulatory labels used here might not match the phonetic details). I have chosen to represent [t d θ ð] as |A I| to be able to formulate the restriction against homorganicity within branching onsets in a straightforward way (i.e. * [tl dl θl ðl] vs [tɹ dɹ θɹ ðɹ]), but nothing hinges on this with respect to the story of /l/-darkening. (Headed |A| is used for uvulars and pharyngeals, or for retroflexes, in languages that have these types of consonants.) Finally, glottals lack a resonance element altogether.

The representation of lenition as decomposition is illustrated in (12) with examples of /t/-lenition from different accents of English (again, putting aside the laryngeal distinction).

(12) /t/-lenition as decomposition

As can be seen, each lenited variant is less complex than the released stop in (12a), occurring in strong positions. The unreleased stop in (12b) results from loss of noise, the element |H|. The non-sibilant apical-alveolar (or slit alveolar) fricative in (12c), found in Liverpool (Honeybone Reference Honeybone, Carr, Durand and Ewen2005) and in Ireland (Harris Reference Harris1994: 121), lacks the stop element, i.e. it is the outcome of spirantisation.Footnote 5 It can weaken further to [h] in function words, via debuccalisation, by losing its resonance elements, shown in (12d). Another form of debuccalisation is known by the name of glottalling, found for example in London, producing a glottal stop; see (12e). Tapping in (12f), common in North America, and rhoticisation (Backley Reference Backley2011: 133), known also as T-to-R (Wells Reference Wells1982: 370), in (12g), characteristic of the north of England, are different forms of vocalisation, deriving a simplex expression of just a single resonance element.Footnote 6

Let us now return to the question as to whether /l/-darkening can also be represented as element loss, similarly to /t/-lenition in English. In (13), the representations of approximants in English are repeated, supplemented by French [ɥ]. As can be seen, they are all analysed as glides, containing solely resonance elements in a non-nuclear position.

(13) Representation of approximants

In addition to the simplex glides (|I| interpreted as palatal, |U| as labial-velar, and |A| as alveolar), complex glides also exist. |U I| defines a labial-palatal glide in (13d), while in laterals |A| stands for the alveolar closure, combined with non-headed |I| or |U|, giving front or back vowel resonance. Light [l] is thus purely coronal, see (13e), while dark [ɫ] is a velarised coronal, see (13f).Footnote 7 The problem then is that darkening of /l/ |A I| to [ɫ] |A U| cannot be represented by simple decomposition. Instead, it requires element substitution lacking a local source, a device explicitly forbidden in this approach.

In fact, another problem is also posed by trying to treat darkening as lenition. Honeybone (Reference Honeybone, Carr, Durand and Ewen2005) proposes that by default lenition applies across the board; however, it can be inhibited by positions sharing some melody with an adjacent position. This predicts that lenition cannot apply to shared structures without also affecting non-shared structures. However, this prediction is refuted by the behaviour of syllabic [ɫ̩], which is darkened even if a vowel follows (as in googling in (1e)), whereas non-syllabic [l] is light in this context (as in feeling in (1a)). The representations are given in (14a–b).

(14) Prevocalic syllabic [ɫ̩] vs intervocalic singleton [l]

Syllabic consonants in English are analysed as branching on a preceding V position in Government Phonology (Szigetvári Reference Szigetvári1999; Scheer Reference Scheer2004; Polgárdi Reference Polgárdi2015a), accounting for their alternation with a schwa plus non-syllabic consonant sequence, such as in [ˈguːgəlɪŋ].Footnote 8 Syllabic consonants, thus, constitute a shared structure, as opposed to the intervocalic singleton. If anything, we would expect to find the exact opposite of what actually happens if /l/-darkening was a weakening process.

A further question concerns the influence of a following [j], as in the examples of Italian [ɪˈtæljən] and soluble [ˈsɒljʊbəɫ] in (1b). Why does [j] block darkening? And if it does, then why do the other glides, [w], [ɹ] and [l] itself not block it too (as in bulwark [ˈbʊɫwək], walrus [ˈwɔːɫɹəs] and soulless [ˈsəʊɫləs])?

Finally, let us examine the proposal of Sproat & Fujimura (Reference Sproat and Fujimura1993), who conducted an X-ray microbeam study of darkening in American English. They submit that every /l/ contains both an apical (consonantal) and a dorsal (vocalic) gesture, and further that in the lighter, syllable-initial /l/s the apical gesture precedes the dorsal gesture, whereas in the darker, syllable-final /l/s the gestures occur in the reverse order. They suggest that the reason for this relative timing lies in the fact that consonantal gestures are drawn to syllable margins, while vocalic gestures are drawn to nuclei.

This proposal has often been criticised in the literature. For example, Ladefoged & Maddieson (Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996: 361) show that in the pronunciation of their American English speaker, velarisation is ‘anchored nearer the beginning of the consonantal articulation than the end’ in both syllable-initial and syllable-final position (as in leaf and feel, respectively), thus the two laterals are not mirror images of each other (pace Sproat & Fujimura Reference Sproat and Fujimura1993). In addition, in British English, initial [l] and final [ɫ] involve different articulatory targets (i.e. different gestures), as evidenced by palatographic and X-ray data discussed by Ladefoged (Reference Ladefoged, Local and Temple2003), based on his own speech. This is confirmed by Turton's (Reference Turton2017) ultrasound study, where for her RP speaker she finds that ‘the initial and final /l/s are an entirely different shape throughout the course of the articulation, and the tongue dorsum retraction remains stable’ (Turton Reference Turton2017: 15). Lastly, it is very difficult to interpret Sproat & Fujimura's (Reference Sproat and Fujimura1993) proposal in an Element Theory approach, where the apical gesture would correspond to the element |A| and the dorsal gesture to |U|. In what sense can |A| be regarded as consonantal, while |U| as vocalic? In fact, |A| is generally thought of as the most vocalic of all elements.

5 /l/-darkening and the apophonic chain

To solve these problems, I propose to represent the lateral in GB as |A I U| underlyingly and interpret it partially in all positions. Backley (Reference Backley2011) does not utilise the combination |A I U| in the representation of consonants, but there is no principled reason for its absence, as it does occur in the realm of vowels (e.g. French [ø]), and all other combinations exist for consonants too (|U I| is utilised for palato-velars like [c ç], and |U A| for uvulars like [q χ]). However, in English, the elements |I| and |U| do not combine in any surface segment: there are no front rounded vowels or palato-velar consonants, and even in the lateral either |I| or |U| surfaces, but not both at the same time. This kind of restriction is represented in Element Theory by |I| and |U| sharing the same line in languages like English, preventing them from combining in a compound expression. Line sharing is a stable property of the grammar; it does not change during a derivation. Therefore, if both |I| and |U| are present underlyingly in the lateral, they must be floating at this level. Association of |I| or |U| then takes place at the phrase level in GB, resulting in the variants |A I| [l] and |A U| [ɫ] in (13e–f). I propose that the choice of which element is realised in which position is determined by mapping the apophonic chain, defined by Guerssel & Lowenstamm (Reference Guerssel, Lowenstamm, Lecarme, Lowenstamm and Shlonsky1996) as |I| → |A| → |U| → |U|, on the structure of the syllable.

Apophony, or ablaut, is a context-free vocalic alternation bearing some grammatical function. An example can be provided by the German verbal forms sing-e, sang, ge-sung-en ‘sing (pres 1sg, pret 1sg, past part)’, where the stem vowel varies in the different tenses without any phonetic conditioning. Apophonic systems, like that of the German strong verbs, are generally regarded as unpredictable and therefore completely lexicalised. However, Guerssel & Lowenstamm (Reference Guerssel, Lowenstamm, Lecarme, Lowenstamm and Shlonsky1996), examining the vocalic pattern of perfective and imperfective Measure I active verbal forms of Classical Arabic, argued that the alternations are not at all arbitrary, in fact they are predictable; moreover, the independent steps can be assembled into a chain, where the output of one step provides the input to another step in the chain. Thus, if there is an empty vowel in the system and it can undergo apophony, it will always correspond to [i], while an [i] will correspond to [a], an [a] to [u], and an [u] to another [u] (giving Ø → i → a → u → u). The resulting apophonic chain has been found to be operative in many other languages, for example in Kabyle Berber (Bendjaballah Reference Bendjaballah2001), Somali, German (Ségéral & Scheer Reference Ségéral, Scheer, Fabri, Ortmann and Parodi1998) etc., and it is assumed to be universally valid. Ségéral & Scheer (Reference Ségéral, Scheer, Fabri, Ortmann and Parodi1998), analysing German strong verbs, and having to deal with compound expressions too, in addition to the simplex vowels [i a u], proposed to modify the apophonic chain to apply to elements, instead of complete segments (producing Ø → |I| → |A| → |U| → |U|). They have also suggested that the apophonic chain is active in onomatopoeic expressions as well, such as pif paf pouf [u] in French, where it does not carry the same kind of grammatical information as in apophony ‘proper’ (see also Boyé Reference Boyé, Bendjaballah, Faust, Lahrouchi and Lampitelli2014 on Malay chiming words). Here I propose to extend the application of the apophonic chain in a different direction, to the association of floating elements of a segment that is built up exclusively of |I A U|, the elements constituting the apophonic chain.

We have seen in (1) that light [l] occurs in prevocalic position in GB, whereas dark [ɫ] occurs postvocalically. In fact, this does not seem to be a property specific to English but rather a cross-linguistic generalisation: some other examples are provided by languages as diverse as Latin (Allen Reference Allen1978: 33–4), Slovene (Greenberg Reference Greenberg2000: 155–8) and Komi (Hausenberg Reference Hausenberg and Abondolo1998).Footnote 9 Although systems with non-alternating /l/ exist, what does not seem to be found are systems with an alternation between a dark [ɫ] in prevocalic position vs a light [l] postvocalically.

To account for the pattern of association of lexically floating |I| and |U|, I propose to map the (non-empty part of the) apophonic chain on the structure of the ‘syllable’, as given in (15).

(15) Mapping between the apophonic chain and the structure of the syllable

The element |A|, being underlyingly associated, can occur in any position. The floating elements, however, are more restricted: |I| is attracted to the prevocalic position, while |U| is attracted to the postvocalic position.Footnote 10 This mapping is ensured by requiring that the association of the floating element |I| be licensed by a following full vowel, while the association of the floating element |U| needs no such licence.

Let us see how the mechanism works in the different syllabic positions. In each case, both the floating |I| and |U| of the lateral want to surface, but only one of them can do so because they share the same line in this language. By virtue of the apophonic chain, association of the element |I| has precedence, but for this association to actually take place, it needs to be licensed by a following filled V position. In prevocalic positions like in (16a–b) this licensing requirement is satisfied, and the element |I| gets associated, while the element |U| remains unparsed (indicated by angle brackets in the representations), and the resulting [l] is light.Footnote 11

(16)

In contrast, in non-prevocalic positions, as in (17a–b), association of the element |I| is not licensed because it is either followed by an empty V position or by nothing, and therefore it remains unparsed. As association of |U| needs no license, it thus surfaces, and the resulting [ɫ] is dark.

(17)

Note that if in a given system the association of |I| requires no license, then it will surface everywhere (regardless of the licensing requirements concerning |U|) because |I| takes precedence on the basis of the apophonic chain. Therefore the non-existent system of dark prevocalic vs light postvocalic /l/ is predicted not to arise.Footnote 12

The representation of feeling in (18b) is entirely parallel to that of gala in (16b): they are both intervocalic singletons, and only the morphosyntactic context differs, with the following vowel being provided by a word-level suffix in (18b). Association of the element |I| is licensed in both cases, resulting in a light [l].

(18) Prevocalic syllabic [ɫ̩] vs intervocalic singleton [l]

The case of a prevocalic syllabic [ɫ̩] is, however, different, as given in (18a). As evidenced by the dark realisation, association of |I| cannot get licensed in this configuration, even though it is followed by a filled V position. I propose to account for this with the help of the Minimality Condition, according to which licensing into a shared structure may be blocked (Charette Reference Charette1989). For example, umlaut in Korean only applies to short vowels, but not to long ones, also constituting a shared structure.

That the shared structure is already present at the time when association of the floating elements happens (at the phrase level) is demonstrated in (19).

(19) Syllabic consonant formation: stem-level (optional) (Polgárdi Reference Polgárdi2015a)

As argued by Polgárdi (Reference Polgárdi2015a), syllabic consonant formation applies (optionally) at the stem level in English: it affects monomorphemic forms, shown in (19a), but in word-level suffixes starting with a sonorant consonant, the initial consonant never becomes syllabic after a schwa, given in (19b), even though the environment is phonologically entirely parallel to that in (19a). This shows that syllabic consonant formation is no longer active at the word level. The shared structures produced by it are, however, present from the stem level on and can block licensing of association of |I|, ensuring that syllabic [ɫ̩] is always dark in English.

The next question to consider is the role of a following [j]. As shown in (1b), the only non-prevocalic position where [l] is light is when it precedes the glide [j]. The question here is how this [j] prevents darkening, and why the other glides, [w], [ɹ] and [l] itself (as in bulwark [ˈbʊɫwək], walrus [ˈwɔːɫɹəs] and soulless [ˈsəʊɫləs]), do not behave in the same way.

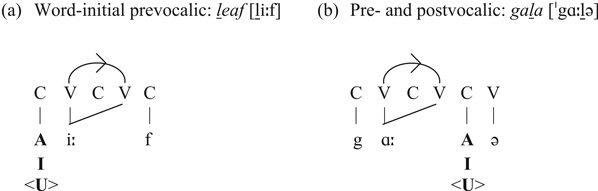

/l/+glide sequences are generally expected to be rare in English: the fake geminate /l/+/l/ arises earliest at the word level, while the other /l/+glide sequences do not constitute either well-formed branching onsets or coda-onset clusters and are, therefore, considered bogus already in earlier versions of Government Phonology. [ɫw] and [ɫɹ] sequences are indeed exceedingly rare. [lj] sequences are more common, although most of them are variable. On the one hand, words like helium [ˈhiːl{i/j}əm] exhibit High vowel gliding, i.e. free variation between a high vowel and a glide preceding an unstressed vowel. Only a few such words, like Italian [ɪˈtæljən], lack the alternant with the vowel [i]. On the other hand, words like lewd [l(j)uːd] only contain a [j] in conservative GB (listed as the second alternative by Wells Reference Wells1990), and the form without the [j] is becoming increasingly common. A stable [j] occurs only in a few words, in post-tonic position, as in soluble [ˈsɒljʊbəɫ].

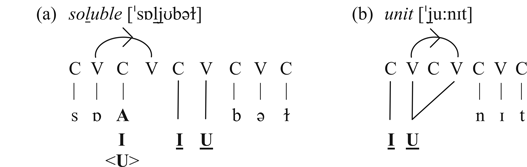

I have analysed High vowel gliding as spreading of the melody of the high vowel in V3 in (20a) into the following empty C4 position, and the sequence [juː] as a complex vowel, consisting of a light diphthong overlapping a long vowel (i.e. as [i̯uː]), shown in (20b), on the basis of distributional evidence, in Polgárdi (Reference Polgárdi2015b). In a light diphthong, two phonological expressions are associated to a single position via two root nodes, preventing the fusion of elements, and making the association of both |I| and |U| possible in this complex segment. As in both (20a) and (20b) the /l/ is followed by a pronounced V position, it is correctly predicted to surface as light.Footnote 13

(20) High vowel gliding and the complex vowel [i̯uː]

In forms like Italian [ɪˈtæljən], a solution can be to specify the [j] with the branching structure in (20a) underlyingly. In forms like soluble [ˈsɒljʊbəɫ], given in (21a), however, I have argued for a reanalysis of the reduced version of the complex vowel (i.e. of the light diphthong [i̯u]) into the sequence [ju], to account for the presence of a stable [j] (as opposed to the variable [i̯] in forms like lewd [li̯uːd]).

(21) Non-prevocalic, preceding a stable [j]

Such reanalysis also happens word-initially (in words like you [ju:] or unit [ˈju:nɪt], as in (21b)), evidenced by article allomorphy, for example. In addition, word-initial [j] followed by a vowel other than [u:] (as in all year [ɔːl jɪə], for example) is also necessarily connected to a C position. I do not have a solution for lack of /l/-darkening in these cases at the moment.

It can be seen, therefore, that the lack of /l/-darkening is justified in forms like helium [ˈhiːl{i/j}əm], lewd [l(j)uːd] and Italian [ɪˈtæljən], and historically also in the few forms like soluble [ˈsɒljʊbəɫ], as the /l/ in these latter cases was originally followed by a vowel, too. In contrast, in the even fewer forms containing a stable [ɫw] or [ɫɹ] sequence, as in bulwark [ˈbʊɫwək] and walrus [ˈwɔːɫɹəs], respectively, and in forms like soulless [ˈsəʊɫləs], containing a fake geminate, no such vocalic origin of the glides can be established, and the cluster-initial /l/ in these cases is dark, as expected.

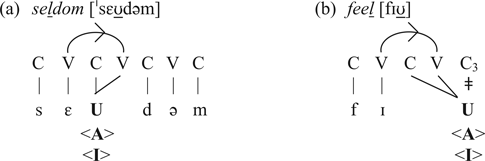

As we have seen, /l/-darkening thus does not involve lenition of /l/, but partial interpretation in all positions (whether strong or weak). In contrast, vocalisation of dark [ɫ] (as in feel [fɪʊ] seldom [ˈsɛʊdəm], google [ˈgʉːgʊ] in London English; Turton Reference Turton2017), involving loss of |A| (the tongue tip contact) in weak positions, is still analysed as lenition, shown in (22).

(22) Vocalisation of dark [ɫ]: lenition

|A U| > |U|

The resulting |U| element might remain non-headed or it might become headed, depending on whether its realisation is spread [ɤ] or rounded [ʊ], respectively.

Accents of English showing uniform realisation of /l/ do not require the abstractness proposed here for GB, and have the light |A I| or dark |A U| representation underlyingly associated in all positions (e.g. Belfast English [l] vs Manchester English [ɫ]; Turton Reference Turton2017).

6 Licensing and /l/-vocalisation

Finally, let me return to the idea of licensing required for the association of the element |I|. The solution as proposed so far is only applicable to the lateral because it is restricted to floating elements. However, the lateral is a member of the class of glides and if we extend our investigation to also include the simplex glides of English, we find that they too require licensing by a following full vowel, even though the element they contain is not floating. As shown in (23), none of the simplex glides can occur before a consonant, see (23a), or at the end of the word (whether after a short or long vowel), see (23b) (cf. examples containing ‘real’ consonants like [k] in these positions: vector, hook and hawk).

(23) Glides [j] |I|, [w] |U|, [ɹ] |A|: ruled out preconsonantally or word-finally

Similar phonetic sequences are well-formed in English (except for the long vowel + glide combination) when they can be interpreted as a diphthong, but [ʊɪ], [ɪʊ] and [ʌə] are not possible diphthongs in GB (and the accent is non-rhotic), and therefore all these examples are ruled out. This means that simplex glides (i.e. C positions containing just a single resonance element) also require licensing by a following pronounced V position (for an in-depth discussion, see Polgárdi Reference Polgárdi2015b).

Given this generalisation, it is better to incorporate the lateral in the system of glides in English, and to formulate the licensing requirement on light [l] as a condition on the element combination |A I| when it is the exclusive content of a C position (i.e. when forming a complex glide), rather than as a condition on association of a floating element |I|. That is, the complex glide [l] |A I| in GB behaves in the same way as the simplex glides in requiring licensing by a following full vowel and, therefore, it can only occur prevocalically. The complex glide [ɫ] |A U|, in contrast, does not require such licensing and, consequently, it can appear in a preconsonantal or word-final position. The mapping between the apophonic chain and the structure of the syllable in (15), repeated here for convenience as (24), still only applies to the lateral because only this glide combines the element |A| with |I| and |U|. Association of the floating elements will be blocked if the resulting combination requires licensing that is not available. Therefore, nothing changes in the analysis above.

(24) Mapping between the apophonic chain and the structure of the syllable

We can then establish a typology of licensing of complex glides in different accents of English. If neither complex glide requires licensing by a following vowel, then both light and dark /l/ are allowed to occur anywhere. However, as association of |I| takes precedence according to the apophonic chain, we expect light [l] to surface everywhere (as mentioned above), as in Belfast English in (25a).

(25) Licensing typology of complex glides

(a) complex glide requires no licensing: uniform realisation of /l/

e.g. Belfast English [l] |A I|

(b) |A I| requires licensing, |A U| does not: /l/-darkening

e.g. GB

(c) |A U| requires licensing, |A I| does not:

e.g. Belfast English [l] |A I| (?)

(d) complex glides require licensing: /l/-vocalisation

e.g. London English

Since in such a system there is no evidence for the presence of the element |U|, the next generation will lexicalise /l/ with just the elements |A| and |I|, both underlyingly associated. Of course, another possibility is to lexicalise |A U|, giving a uniformly dark [ɫ] in all positions, as in Manchester English,Footnote 14 or to lexicalise both |A I| and |A U|, producing a system with a contrast between light /l/ and dark /ɫ/ (which is unattested in English but can be found in other languages, such as Albanian; Ladefoged & Maddieson Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996: 186, 197).

When |A I| requires licensing, but |A U| does not, the result is the familiar pattern of /l/-darkening found in GB, as in (25b). The opposite situation, in (25c), where |A U| requires licensing, but |A I| does not, again produces a light [l] in all positions because of the precedence provided to the association of |I| by the apophonic chain, and this system seems therefore to be indistinguishable from (25a) (but I will return to potential cases of underlying association below). As we have seen above, there is no way in this analysis to derive a system with dark prevocalic [ɫ] vs light postvocalic [l], a prediction which is born out by the facts.

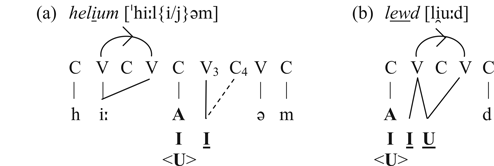

Finally, if both complex glides require licensing, we get a system like that of London English, in (25d). Prevocalically, a light [l] surfaces, just as in GB. Non-prevocalically, |A I| is not licensed, therefore |A U| is checked as the next possibility. However, this is not licensed either. Perhaps the choice of which element to underparse can be again attributed to the mapping of the apophonic chain on the structure of the syllable, as in (24). All simplex glides need to be licensed in English, but preserving |U| is in line with the next step in the apophonic chain (even if this means underparsing the element |A| which is not floating but underlyingly associated). To comply with the requirement of licensing, the configuration is reinterpreted as a diphthong. The representations of seldom [ˈsɛʊdəm] and feel [fɪʊ] are shown in (26).

(26) London English: vocalization

In Polgárdi (Reference Polgárdi2015b), I proposed to represent the off-glide of diphthongs as a branching structure, occupying a whole CV unit. This representation satisfies the requirement on glides to be licensed by a pronounced V position, and it captures the nature of diphthongs as a category in between long vowels and closed syllables. In this approach, the two CV units constituting the diphthong are bound by proper government (similarly to the representation of long vowels and closed syllables in (3)). This is automatically satisfied in (26a), where non-prevocalic vocalised /l/ follows a short vowel. However, when the preceding vowel is originally long (or a diphthong), the melody of the off-glide needs to spread to the left (and delink from its original position), searching for a proper governor, shortening the preceding vowel and leaving the abandoned C3 position unrealised, as shown in (26b).Footnote 15

This analysis is confirmed by the vowel neutralisations found in the position preceding vocalised /l/, reported by Wells (Reference Wells1982: 313–17), resulting in the formation of (new) diphthongs, illustrated in (27).

(27) London English vowel neutralisations (Wells Reference Wells1982: 313–17)

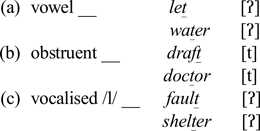

Additional evidence is provided by /t/-glottalling, which lenites /t/ to [ʔ] when it occurs outside a foot-initial onset in London English, as shown in (28a). Glottalling is blocked when /t/ is preceded by an obstruent, as in (28b), but it applies when it follows a vocalised /l/, as in (28c) (Harris Reference Harris1990, Reference Harris1994: 217–22).

(28) London English /t/-glottalling (Harris Reference Harris1990, Reference Harris1994: 217–22)

The same thing happens after a vocalised rhotic or nasal, as in [pɑːʔ] ‘part’ or [ˈtwɛ̃ʔi] ‘twenty’, indicating that the vocalised resonants indeed occupy the nucleus, providing a postvocalic context, parallelling (28a). In accents without /l/-vocalisation, forms like (28c) surface with an unlenited [t] (e.g. New York City English with tapping and Irish English with spirantisation in postvocalic positions like (28a)).

Returning to the typology in (25), repeated as (29) for ease of exposition, let us examine the possibility of underlying association in each case.

(29) Licensing typology of complex glides: with underlyingly associated elements

(a) complex glide requires no licensing: uniform realisation of /l/

e.g. Belfast English [l] |A I|, Manchester English [ɫ] |A U|

(b) |A I| requires licensing, |A U| does not: /l/-vocalisation to [ɪ]

e.g. Middle-Bavarian German [l] |A I|

(c) |A U| requires licensing, |A I| does not: /l/-vocalisation to [ʊ]

e.g. Glasgow English [ɫ] |A U|

(d) complex glides require licensing: /l/-vocalisation

e.g. as in (b) or (c)

The systems in (29a) have been discussed above. In (29b–c), lexically specifying the combination that does not require licensing, |A U| vs |A I| respectively, produces a system identical to that in (29a), i.e. Manchester English vs Belfast English. Therefore, I have not indicated them again in (29b–c). Specifying the other combination, however, can give us an account of /l/-vocalisation in systems lacking a light~dark alternation. (29c) is a typical system with prevocalic dark [ɫ], vocalised to [ʊ] postvocalically, found in several accents of English, e.g. Glasgow English (Stuart-Smith Reference Stuart-Smith, Foulkes and Docherty1999). As the element |I| is absent from the combination, the first half of the apophonic chain cannot take effect here; however, its second half is satisfied during vocalisation, similarly to the analysis of London English. The system in (29b), with prevocalic light [l] vocalising to [ɪ] postvocalically, seems to be less common, but it occurs for example in Middle-Bavarian German (Djabbari et al. Reference Djabbari, Fischer, Hassemer, Hildenbrandt, Huber, Neubarth and Rennison2007; Bendjaballah Reference Bendjaballah2012; Vollmann et al. Reference Vollmann, Seifter, Hobel, Pokorny, Moosmüller, Sellner and Schmid2017).Footnote 16 Here it is the prevocalic context that matches the apophonic chain, where no change is observed, whereas postvocalic vocalisation to |I| contradicts it. Perhaps this is the reason for the rarity of this pattern. Finally, when both complex glides require licensing, as in (29d), then specifying |A I| underlyingly will give a system of vocalisation like that just discussed in (29b), while specifying |A U| will give a system like that found in (29c).

Closer examination of the licensing relation operative in the process of /l/-darkening has, thus, revealed that the lateral, as a complex glide, fits into the system of simplex glides in English. Depending on the accent, the complex glide either requires licensing by a following pronounced V position or it does not, while the simplex glides always require such licensing. Vocalisation of /l/ has been shown to result from the lack of relevant licensing, inducing decomposition in a weak position, integrated into the mechanism of the apophonic chain.

7 Summary

I have shown that /l/-darkening in English cannot be regarded as a lenition process because it does not simply involve element loss in a weak position, but rather substitution of elements without a local source. In addition, it applies to a prevocalic syllabic [ɫ̩], while leaving intervocalic singletons intact, contradicting Honeybone's (Reference Honeybone, Carr, Durand and Ewen2005) generalisation that lenition is not expected to apply to shared structures without also affecting non-shared structures.

I have proposed to represent the lateral in GB as |A I U| underlyingly, with the elements |I| and |U| floating because of sharing the same line in this language. Their association takes place at the phrase level and is governed by a mapping of the apophonic chain (|I| → |A| → |U| → |U|) on the structure of the syllable, resulting in partial interpretation of the lateral in all positions (whether strong or weak). As the apophonic chain gives precedence to the association of the element |I|, the cross-linguistic lack of systems exhibiting an alternation between a dark prevocalic [ɫ] vs a light postvocalic [l] is accounted for.

The mapping between the apophonic chain and the CV-tier is established by requiring the element combination |A I| of a complex glide to be licensed by a following pronounced V position, while the combination |A U| is in no need of such licensing. Further, this licensing is blocked by the shared structure of a syllabic consonant, ensuring that syllabic [ɫ̩] is always dark in English. A lateral preceding a [j] is light because in most cases it in fact precedes a filled V position or it used to precede one at an earlier stage of the language. The lack of /l/-darkening before a word-initial [j] still awaits explanation.

Finally, I have integrated the lateral as a complex glide into the system of simplex glides in English, all of which need to be licensed by a following full vowel. The behaviour of the lateral varies from accent to accent, and depending on its underlying representation and whether it requires licensing, the system might or might not exhibit an alternation between light and dark /l/, as well as presence or absence of vocalisation of the lateral, analysed as loss of the element |A| in weak positions. I have argued that it is possible to derive the typology of /l/-darkening and vocalisation from the representation of the lateral and its licensing requirements, if we employ the apophonic chain also to this area of grammar.