1. INTRODUCTION

In the early independent period, after the crisis of the Spanish colonial economy, Buenos Aires managed to keep its position as the main commercial hub of the region for both local and interregional trade. Thanks to the complete liberalisation of its overseas exchanges, the city joined a renovated export scheme, which combined the demands of the urban and rural areas.

Thus, during the first half of the 19th century, Buenos Aires successfully connected the whole hinterland of the Rio de la Plata to the Atlantic trade. Moreover, in this period overseas exchanges were favoured by a remarkable reduction in the cost of trans-Atlantic shipping, which allowed higher profits and boosted intercontinental trade. This shift meant a renovation of the alternatives on the merchant circuits and a rise in the consumption levels of overseas goods, as well as an increase in exports from rural areas. It also meant, however, the beginning of a new era of higher economic uncertainty marked by the abrupt fluctuations in trade flows, costs and prices, due in part to international cycles but, especially, to the local conflictive scenario after independence and the ever-changing political and institutional framework in Buenos Aires.

In the post-colonial economy of Buenos Aires, overseas trade was crucial for the supply of a wide range of basic popular consumption goods on the domestic market, as well as for the export of the local cattle production. It was decisive also for the revenue of the province of Buenos Aires, which was increasingly dependent on the performance of the Atlantic trade.

In recent decades, several studies have focused on these key features of the post-independence economic matrix. Scholars have examined the cycles experienced by the Buenos Aires economy, its commerce and the local financial market in detail. The studies of agricultural expansion have shown the advance and consolidation of the local productive frontier in different stages. A renovated cattle-ranching economy was well articulated to the service sector of the port city and its commercial network which stretched to the rest of the provinces.

The expansion of the production frontier and settlement in the southern and western frontier lands which began in the 1820s built-up an economic complex that was clearly oriented by the cattle-farming export industry, but without bringing an end to the social reproduction of a broad and dense patchwork of farmers and peasants. At different scales and applying diverse ways of economic exploitation, they formed the social matrix of the rural areas of Buenos Aires.Footnote 1 This economic expansion was concomitant to a fast demographic growth, both in the city and its rural hinterland. The rates of urban growth reached 1.03 between 1822 and 1838, and 2.03 between 1838 and 1854. The population of the whole province by this last year was 270,463 (Mateo Reference Mateo2013).

Likewise, research on the export trade has shown that the Buenos Aires port increased its share among the other merchant cities in the Rio de la Plata region, serving as a hub for a far-reaching economic area, which established its overseas link in Buenos Aires. As a key component of this vast complex, Buenos Aires was not just the natural connection for the farming hinterland around the city. The city was also, increasingly, a centre for control and redistribution of a business network, involving commercial, financial and all kinds of services for a large trading sphere that included the interregional markets of the inland provinces, through the circulation of export produce, as well as the profitable reselling of overseas goods.Footnote 2

After 1820 the political and institutional framework changed deeply in Buenos Aires, renovating the fiscal structure of the province with new tax and duties acts. These reforms left property and incomes virtually free of taxation, as direct taxes were not significant for the province's budget. Instead, this fiscal reform continued and enhanced the Spanish colonial tradition of a revenue system based on the taxation of commerce. Thus, public revenue in Buenos Aires followed the dynamics of overseas trade via the introduction of indirect taxes on imports in an almost constant correlation.Footnote 3 Since then, through most of the 19th century, a close relation was established between the fluctuations of revenue and overseas exchanges at the port of Buenos Aires.

Despite the significance of imports for the local economy and the fiscal capacity of the Buenos Aires government, and in contrast to the abundance of research on these topics, we still know little about the evolution of imports and prices in the Buenos Aires market, a highly relevant question for the local economic matrix during the 19th century. Thus, in this paper we focus on the fluctuations of relative prices and aim to construct an index of price baskets for imported, exported and local goods. These baskets allow us to analyse the evolution of a general price index in order to assess how the prices of the most relevant goods were affected, both in their general trends and in special situations, following the introduction of free exchange policies during the early independent era in South America and the global trend of the reduction of shipping costs. We also aim to study the impact on local prices of fluctuations in supply, the substitution of imports, as well as the negative effects of the Buenos Aires blockades, the uncontrolled issuing of inconvertible paper money, and the cycles of political instability during the first half of the 19th century.

2. INTERPRETING THE EVOLUTION OF PRICES IN BUENOS AIRES

In his classic work on Argentine federalism, Miron Burgin stated that inflation in post-revolutionary Buenos Aires was triggered by the Brazil war between February 1826 and mid-1830, and it continued, without interruption, in cycles during the following years. Later, during the 1840s, inflation, instability and price volatility would be experienced again in Buenos Aires as a result of the port blockades by France and Britain. According to Burgin, there were three moments of high inflation during the first half of the 19th century in Buenos Aires, corresponding to each port blockade, and he attempted to explain each of them with the study of records from the Buenos Aires Treasury and the local financial market, taking the fluctuations of the exchange rate of the gold ounce as the only indicator of the local inflation process (Burgin Reference Burgin1960).

Burgin acknowledged that such a devaluation of the local paper money was more than a financial symptom. The phenomenon initially appeared to be a temporary imbalance of the monetary system, but turned out to represent a major disorder of the entire economy, reflected by the high level of inflation and involving a deep shift in the distribution of income. The price increase had been a general trend but its impact was uneven among the various types of goods and services. According to Burgin, the prices of basic consumption goods rose at a faster pace than wages, meaning that the real income of salaried workers decreased, both in absolute and relative terms.

As regards the evolution of relative prices, not all consumption goods suffered from the devaluation of the local currency with the same intensity. Burgin claimed that all merchandise related to the overseas trade, both imports and exports, responded quite directly to the fluctuations of the gold exchange rate, while domestic market goods lagged behind. Therefore, those who most resented the impact of the depreciation of paper money were local manufacturers (mainly craftsmen and artisans) as well as merchants operating with those locally produced consumption goods. As for the cattle ranchers, they were in a more favourable position since their real incomes were linked to the export market and so they probably benefitted from the effects of the gold exchange rate increase.

Hence, back in the 1960s, Burgin had already advanced some interesting hypotheses concerning the evolution of prices, but his research was not based upon a full analysis of the various prices of the local market. As previously noted, his study of local prices paid much attention to monetary and financial factors, especially the variations of the gold ounce exchange rates as the main «thermometer» to assess price inflation. Burgin certainly made a valuable contribution by noting the differential shift of relative prices, but he could not provide specific evidence of the changes affecting different types of goods and their evolution in reaction to local circumstances and global cycles. However, using qualitative sources and the already existing evidence of high inflation during this period, he did point out the possible consequences of the variations of relative prices, indicating which were the social sectors affected in their purchasing power as well as those who benefitted from such drastic shifts.

Later, Tulio Halperin Donghi, in his study of Buenos Aires finances claimed that the huge increase in military expenditure resulting from the Brazil war had extremely negative effects on the public budget. The resulting fiscal deficit was covered with the massive issue of paper money without backing in gold or silver. It was the beginning of the locally well-known «inflationary financing» of the fiscal deficit; the growing public expenditure was covered not by debt, but through inconvertible money emission, with a series of consequences for prices and the economy in general. According to Halperin, it was not possible to assess accurately for the period of the Brazil war—unlike other periods—the local market impact of the overseas trade disruption due to the Brazilian blockade against Buenos Aires. However, his study included an estimation based on qualitative testimonies and the analysis of local legislation during those years, in order to understand the relation between the evolution of prices and the inconvertible money emission (Halperin Donghi Reference Halperin Donghi1982).

Halperin also claimed that a transfer of wealth could be observed through this inflation process, as different social sectors experienced the fluctuations of relative prices and the concomitant loss of their purchasing power unevenly. Thus, the Brazil war would have meant deprivation for the urban middle class, as well as the working class depending on jobs related to the paralysed overseas trade. Even some members of the proprietary classes would have felt alarmed by the economic crisis. Therefore, Halperin described the situation of war and inflation of the 1820s using qualitative sources to enrich his analysis of fiscal and financial data, and suggested, like Burgin, some hypotheses about the costs of inflation, although he did not move forward to a specific examination of prices and their evolution in relative terms.

In a 1978 work, Halperin Donghi focused on the question of prices during the Buenos Aires blockades between 1838 and 1850. This study of commercial conflicts, prices and monetary issues offered a specific analysis of the evolution of prices for several goods, showing the differential impacts of the blockades. In terms of inflation, the first blockade (1839–1841) turned out to be more intense than the second (mid-1840s). For the first time, a study of inflation went beyond government documents and financial sources and included a short series of prices for a variety of imported and locally produced goods, taken from the Gaceta Mercantil and the Women's Hospital records. The analysis of this series of prices showed that during the French blockade (1839), the prices of local products were affected less than the prices of imported goods, which experienced a remarkable increase in their nominal values (Halperin Donghi Reference Halperin Donghi1978).

Halperin also noted correctly a very clear divergence in the evolution of relative prices when considering the effects of inflation on the products in Buenos Aires with highest levels of demand, due to the official regulation of fixed prices for bread and meat. This price control policy restricted the increase of the nominal prices for those basic consumption products but did not prevent downgrades affecting quality or the reduction of piece weight at retail sales. Another of Halperin's important observations was the notorious rise in the price of wheat, hides and other foreign trade goods such as pasta, rice, sugar and yerba mate. Examining these prices, the author claimed that the inflation impact was very uneven, as some products had increased by 180 per cent while others rose by 500 per cent. However, this list did not include a very important category: textile goods. As we can see, Halperin's explorations regarding prices during the blockades had opened an interesting road to understand severe price fluctuations at key moments, and to assess the complex differential evolution of relative prices in Buenos Aires.

However, further historical research on Buenos Aires prices only came at the end of the 1980s, with Samuel Amaral's innovative work. He distinguished clearly for the first time among local historians the various types of inflation, introducing the concept of «fiduciary inflation», a phenomenon caused by the uncontrolled issue of paper money and generating a very fast alteration of relative prices. Fiduciary inflation was different from monetary inflation, which is a result of the slower adjustment of relative prices caused by the changing ratio between the circulating monetary mass and the monetary balance of the economy. Amaral was also the first to study the evolution of prices and the specific correspondence between the prices of some goods on the local market and the variables of the issue of paper money and bonds during the Brazil war simultaneously. Beyond the fluctuations of the gold exchange rate and the government resort to the issue of paper money to finance deficit, Amaral's study showed specifically the evolution of the prices of imported goods, local exports and the wages of the public workers of Buenos Aires (Amaral Reference Amaral1988, Reference Amaral1989).

According to Amaral, post-1826 inflation resulted in the increase of local prices of imported goods by 290 per cent, while export goods rose by 52 per cent, and the gold ounce rate shot up by 196 per cent. Moreover, since 9 January 1826 banknotes officially ceased to be convertible, and so a special fee was paid for the gold exchange. Comparing these figures to the price increments for 1825 allows us to observe the transition from monetary inflation to fiduciary inflation, due to the coming war with Brazil, which triggered massive monetary expansion and the deficit in the balance of trade.

The official suspension of paper money conversion meant a price acceleration which lasted between 1825 and 1834. During this period there was a long adjustment of the relative prices, marked by a clear decoupling between the price index of imported goods and the gold ounce rate, on the one hand, and the prices of exports and local wages, on the other hand. This imbalance was outstanding for the 1826–1828 period, because the prices of imported goods rose by more than 900 per cent in September 1827 (taking 1824 as base year), while the range of increments for local wages went from 112 to 200 per cent. Unfortunately, there are no data available to assess the evolution of prices from October 1827 until January 1830, but it is likely that between 1829 and 1831 there might have been a process of price adjustment which was reflected in the new equilibrium of relative prices as can be noted by the more stable figures of 1832–1834.

There is another available set of studies that focused on prices in Buenos Aires, although in a more specific way, as they traced the prices of a few products, and for quite diverse periods. Among others, we would highlight the work by Broide and Garavaglia for the livestock market, the research by Gorostegui de Torres on wheat, and Barba's study for a basket of local products and imported goods. Although all these researchers described the evolution of prices in nominal terms for the respective goods, they did not advance their analyses further into the assessment of relative prices, the comparison of price baskets, or a general inflation rate for our period.Footnote 4

Hence, despite all the valuable contributions we have reviewed, there is much to explore in order to understand the relative price evolution in Buenos Aires and to assess price baskets as well as inflation rates. These questions are still pending because previous research has only dealt with them in an incomplete way. In certain cases, researchers proceeded through the indirect use of financial variables (especially the gold ounce exchange rate and monetary emission). In the best cases (Halperin and Amaral), studies were based upon a few consumption goods (such as sugar or yerba mate, mainly), or some export goods (hides and other livestock goods) as indicators of the general evolution of prices. Moreover, most of these studies of the local evolution of prices were marked by special junctures—that is, the blockades—and were not weighted, so the resulting figures are not representative of the total traded and consumed goods in Buenos Aires, either imported, exported or locally produced. Furthermore, the long-run variations in prices during the first half of the 19th century were not assessed in most of the works mentioned, as they are mostly focused on specific crisis situations, showing at best the evolution of prices for the short run or for quite diverse time spans. Except for Halperin Donghi's (Reference Halperin Donghi1978) work, most of these studies did not take into account the incidence of local products (especially grains and meat), which are highly relevant to assess the impact of inflation on the urban population of Buenos Aires.

In order to overcome such limitations of the existing studies, we have analysed a series of weighted price baskets, taking into consideration reasonable and representative products and periods of time. Our baskets include both local products as well as import and export goods, aiming to calculate a general index of weighted prices. With this tool we are able to make a general and weighted analysis on the evolution of relative prices in Buenos Aires during the first half of the 19th century.

3. ON THE SOURCES AND METHODOLOGY

The prices used in this research were taken from the lists of wholesale prices created by the Junta de Comercio (Board of Trade) and published in the local press. Both the Gaceta Mercantil and the British Packet included sections of wholesale prices, and they are part of the collections of Argentina's National Library.Footnote 5

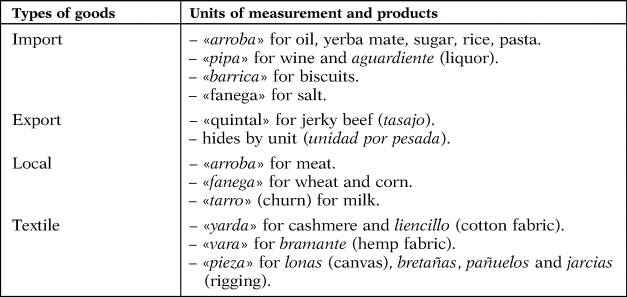

For certain products there were weekly lists of prices and we were able to generate average monthly prices. The units of measurement for these products were those of the customary Spanish system. The following table summarises the correspondence between them and the diverse products traded in Buenos Aires and listed in the press:

Prices per unit and average prices are expressed in index numbers, using 1824 as base year. Annual values for quantity of export livestock products have been taken from Rosal and Schmit (Reference Rosal and Schmit1999). Monthly and yearly figures for commercial activity and the origin of ships entering the port of Buenos Aires are taken from Nicolau (Reference Nicolau1987). The monthly exchange rates for the gold ounce and the silver peso are taken from Irigoin and Salazar (Reference Irigoin and Salazar1996) and Álvarez (Reference Álvarez1929). Statistics for monetary emission are taken from Casarino (Reference Casarino1922) and Burgin (Reference Burgin1960).

The weighted price indexes have been calculated using the Laspeyres formula:

Here, P1 = yearly price, P0 = base price and Q0 = base quantity.

For the weighting of imported goods, we have taken data from the official Report on the Buenos Aires Trade of Importation for the years of 1835 and 1837, using the following shares: textiles, 20 per cent; sugar, 15 per cent; yerba mate, 15 per cent; salt, 10 per cent; wine, 10 per cent; rice, 10 per cent; aguardiente, 5 per cent; oil, 5 per cent; pasta, 5 per cent and biscuit, 5 per cent.Footnote 6 For the information on goods taken from the available studies, we have considered this weighting: meat, 50 per cent; wheat, 30 per cent and corn, 20 per cent. Export goods have been weighted according to Rosal and Schmit (Reference Rosal and Schmit1999), considering the following composition: hides, 70 per cent and other livestock goods, 30 per cent.

As regards the incidence of imports on the Buenos Aires economy, there are diverse views about their importance as part of household consumption. Gelman and Santilli estimated the share of imported goods within the consumption basket at around 20 per cent, but Halperin and Burgin claimed that the consumption of imported goods was higher. We consider that it is necessary to take into account two factors that were differentiated along the evolution of the demand: on the one hand, the consumption of imported goods throughout the vast commercial hinterland linked to the port of Buenos Aires, while on the other hand, it is important to assess the incidence of the consumption of those imported goods on the Buenos Aires domestic market. For the general price index of Buenos Aires we have considered a weighting of local goods (70 per cent) and imported goods (30 per cent).Footnote 7

4. THE EVOLUTION OF PRICES IN BUENOS AIRES BETWEEN 1824 AND 1850

4.1 The Prices of Imported Goods

In order to analyse the evolution of the prices of imported goods in Buenos Aires, we have constructed a basket with different products that we consider to be representative of the most demanded foreign goods on the local market. It should be noted that this set of merchandise, consumed throughout the Rio de la Plata region, arrived in the city from the most diverse origins. First, there was a set of goods coming from other South American ports, including Brazilian rice, sugar or even yerba mate from Paranaguá. Other products, including oil, pasta, biscuits, aguardiente (liquor), Carlón wine, salt from Cape Verde and a vast range of textile goods came from further afield: Europe, Africa and North America.

As we see in Figures 1 and 2, these overseas trade goods experienced a constant rise in their nominal prices in paper money for our period. However, at the same time, they show a variety of trends and a significant volatility, especially due to the highly uneven impact of the blockades, changes in their demand levels and their potential substitution with alternative products available in Buenos Aires.

FIGURE 1 Prices of rice, sugar and yerba mate.

FIGURE 2 Prices of oil, aguardiente, wine, salt, pasta, biscuit and textiles.

Therefore, this divergent evolution among the imported goods should be carefully taken into account. In certain extreme cases it reached record highs and volatility was severe, especially the prices of those goods from Brazil and other South American origins—hitherto, the most studied products. In Buenos Aires these goods traditionally enjoyed high demand and were not easily substituted, so their prices suffered from drastic changes in the wake of the Brazilian blockade of 1826–1828, and also during the mid-1830s. They also recorded sharp fluctuations during the blockades of 1838–1840 and 1846–1848.

Meanwhile, the goods imported from more distant overseas origins experienced lower levels of demand and shortage. They were more easily substituted on the local market, so despite the fact that their prices showed a rising trend, these increments were less severe and showed lower volatility than the prices of imported goods from South American origins during the period under consideration.

Thus, as Samuel Amaral demonstrated for the 1820s and 1830s there was a clear trend of rapid increase in the nominal prices of South American products traded in Buenos Aires. This would fairly justify the local requests of substitution for certain imported goods, as there were competitive alternatives from upstream provinces, such as Corrientes, Santa Fe and Entre Ríos. For instance, the increments for rice (with record increases of 1,000 per cent and an average rise of 600 per cent), or sugar (with maximum increments of 800 per cent and an average increase of 500 per cent), while the prices of yerba mate rose much less, with an average of 300 per cent (Amaral Reference Amaral1988).

The issue of South American (and particularly Brazilian) imports was central to the political debate previous to the Federal Pact of 1831. This was especially crucial for the position adopted by the provincial leaders of Corrientes, who campaigned against the free exchange policies of Buenos Aires during the 1830s. Their goal was to gain commercial protection for the tobacco and yerba mate farmers and merchants in their province, affected by the imports of those goods from other South American countries into Buenos Aires and other regional markets. The debate on free trade caused frictions between the rulers of the confederated provinces as well as a commercial and tariff conflict, in which Corrientes tried to take advantage of the juncture supply difficulties of South American rival trade goods in order to raise support for their cause in Buenos Aires. However, these attempts at substitution were not successful since the quality of the Corrientes produce was not competitive, and the tariff protection they wanted was not introduced by Buenos Aires (Schmit Reference Schmit1991).

Later, through the 1840s, the prices of imported merchandise would increase dramatically again during the French and British blockades. In 1840, rice peaked following an increase of 3,500 per cent, while sugar reached a 4,200 per cent rise, and the price of yerba mate increased by 2,000 per cent. Later in 1846, this group of products increased around 4,000 per cent. However, as we can notice on the graphs, the prices of these products experienced sharp oscillations and by the end of the period, the average increases ranged from 1,200 to 2,000 per cent.

Unlike the case of goods imported from other South American countries, the prices of the rest of the imported merchandise under consideration in this study experienced divergent trends and confronted different situations, although they suffered from a lesser impact during the blockades of the 1840s. By the end of our period, their rates of increment went from a maximum of 600 per cent to a minimum of 220 per cent, much lower figures than those for the South American trade goods. Moreover, we can notice that—despite their increments—the prices of salt, oil, wine and aguardiente evidenced a long trend of gradual increment, while biscuits and textile goods had a sharp and inconstant trend, with a fast rise during the same years.

4.2 The Prices of Local Products

As we can see in Figure 3, there were also different trends in the prices of local products. The rise in the price of wheat and corn after 1830, which suggests the presence of an uneven evolution between supply and demand on the local grain market, is especially remarkable. It seems, despite the production of many farmers in the rural hinterland of Buenos Aires, that crop levels still lagged behind the needs of a growing population. In addition, as many historians have pointed out, this was a period of several droughts and political turmoil in the province; such factors would also have affected grain production (Djenderedjian Reference Djenderedjian2008).

FIGURE 3 Prices of wheat, corn, milk and meat.

Garavaglia's valuable study on the prices of rural produce sheds light on the evolution of the grain and livestock markets. While the prices of wheat and corn increased in the 1840s, the prices of bovine cattle went down. This could be explained—besides the effect of the blockades—by the consistent growth of the local cattle-raising activity (Garavaglia Reference Garavaglia2004). These remarks are coherent with the conclusions of the Rosal and Schmit (Reference Rosal, Schmit and :2004) study on the outstanding increase in cattle-ranching during the very same decade. Hence, combined with the impact of the fixed price regulation and the vast supply of meat, all these factors would help us understand the differential behaviour of the prices of these goods, which are so important for local basic foodstuff consumption.

As shown by Djenderedjian's studies, following the 1840s there was a contrast in terms of supply between the cattle-raising expansion and grain agriculture in Buenos Aires, so the growing demand for wheat and corn on the local market remained unsatisfied. This was clearly reflected in prices; from the end of the 1830s, with the port blockades, the price of wheat increased substantially, with an upward trend that would continue through the following decade. Thus, the trends for the price of wheat were clearly different from the evolution of prices on the meat market. With no doubt, beef was the main item in the local consumption basket, with prices that would evolve in a stable way despite minor and sporadic increments until the mid-19th century (Garavaglia Reference Garavaglia2004).

4.3 The Prices of Export Products

Local market prices for the main export goods—hides and jerky beef—show the juncture effect of every blockade, as they suffer from a clear fall or a downward trend in 1826–1828, 1839–1841 and 1846–1847 (Figure 4). However, in the long run the trend for these export goods reflects steady growth, despite the fact that international prices were not on the rise. They clearly experienced continuous adjustments of value, as we will see in the final section of this work, as a sequel to the local inflation, derived from the monetary emission policy in Buenos Aires.

FIGURE 4 Prices of bovine hides and jerky beef (tasajo).

Therefore, excluding the special juncture alterations caused by war or blockades, the local prices of export goods adjusted their values not so much in line with the oscillations of prices abroad or by substantial changes in their quality, but essentially due to local shifts in their nominal value due to general inflationary pressure in Buenos Aires.

4.3.1 Weighted baskets for imported goods, exports and local products

Our price indexes for imported goods, exports and local products reveal that although they all had an upward trend, each category showed specific characteristics and behaviours (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5 Weighted index of import goods, exports and local products.

For instance, the prices of imported goods started to rise following the commercial blockade of 1826 and maintained a level of approximately 400 per cent due to local market uncertainty until the end of the 1830s. Later, these prices started to increase again, reaching their extreme highs during the second and the third blockades, increasing the prices of imported goods by up to 650 per cent. These average inflation rates were significantly high, but much lower than the figures other authors have calculated in their analyses of prices on the exclusive base of import goods from other South American origins. The prices of local products, in contrast, experienced no relevant increments during the Brazil war, but after 1830 they initiated an upward trend, especially due to the shift in grain prices. This trend saw sharp increments during the 1840s, with noteworthy peaks and taking the average increase rate to 550 per cent by the end of the period under study.

Finally, local prices of export goods also experienced an upward trend with fluctuations due to the impact of the port blockades, but in this case the pattern of increment was more stable in the long run. This category of goods seems to have experienced a more gradual adjustment, closely following the dynamics of the issue of paper money and the fluctuations of the gold ounce rate, with a maximum high of 900 per cent in mid-1840, and a 700 per cent average increase at the end of the our period.Footnote 8

4.3.2 Inflation weighted index for the first half of the 19th century

If we consider the evolution of a general price index for the 1824–1850 period, based on the proposed weighting it is plausible to conclude that between the Brazilian blockade of 1826 and the mid-1830s, there was a base price increase of 400 per cent in Buenos Aires (Figure 6). For a later period, during the second blockade (1838–1840), prices increased substantially at extreme levels, due to the significant and simultaneous increment of both imported goods and local products, which led to peak average rises of 1,700 per cent in 1842 and 1,500 per cent in 1847. However, in global terms, the increments of prices in Buenos Aires for the mid-19th century have an average rate of around 650 per cent. We believe these percentages of general price increase are more realistic than the available rates in the local historiography in order to express the general impact of the local inflationary process on the main consumption goods in Buenos Aires during the first half of the 19th century.

FIGURE 6 General price index in Buenos Aires.

4.3.3 Correlation between paper money emission and the evolution of prices in Buenos Aires

A relevant question regarding the evolution of prices in Buenos Aires during our period is that of the relationship between price increments and local monetary and fiscal dynamics. Consequently, in this section we aim to advance a series of coefficients of correlation in order to assess the interaction between the evolution of prices and the issue of paper money. In order to achieve a high degree of certainty for the following calculations, we will establish monthly correlations for two periods: 1825–1834 and 1836–1850.

For the first period, the coefficient of correlation between the prices of imported goods and monetary emission is 0.93, while for the second period the figure is 0.86. This shows a high correlation between the two indexes. At the same time, it is also significant that for the whole period of our research the correlation between the gold ounce rate and the price indexes of the imported and exported goods is 0.91 in each case. The pattern seems clear: if the gold ounce adjusted its exchange rate at the pace of monetary emission, so did the local prices of export goods.

The prices of local products, however, present a quite different situation, for they had a low correlation of 0.50 and 0.45 in relation to the emission and the gold ounce. The behaviour of prices in this category was, then, evidently influenced by other factors, as already stated, more dependent on demand and supply, both in terms of their formation and their trends.

These coefficients suggest a strong correlation between monetary emission and the rise of the gold ounce, with the correspondent loss of value of the local paper currency (the so-called peso papel). However, as we have also stated, there was an intense correlation between monetary emission, the gold ounce rate and the price indexes for imported goods and export products, beyond the juncture aggregate factor of high volatility during the blockades.

It is also interesting to confirm in a quantitative way that—within the general indexes for the prices of imported goods, exports and local products—the products of each basket had among themselves a diverse degree of correlation in their evolution. In the case of imported goods, as we have already noticed, there was a high coefficient of correlation between the South American prices of rice, sugar and yerba mate at 0.80 and 0.78 because all these products shared a similar origin and they were traded within the same commercial circuit. A similar remark could be made about the coefficients of correlation for oil, wine and salt: they were all Atlantic trade goods and their coefficients of correlation were 0.90, 0.80 and 0.86, respectively.

Likewise, among the local products, there was a strong relation of 0.88 between the evolution of the price of wheat and that of corn. On the contrary, there was a very low relation of 0.46 between the prices of meat and milk. Meanwhile, between the first group (grain) and the second (meat and milk), the coefficient hardly reached 0.33 and 0.59, which indicates the remarkable differences in market conditions for the local cattle-raising activity and the grain agriculture in this region.

As for another section of the overseas trade, we can notice that between hides and jerky beef, the two main export products of Buenos Aires in this period, there was a coefficient of correlation of 0.79. This was probably due to the difference in the demand and the dynamics of the market for each product; there were important differences between the hides market (mainly Europe) and the jerky beef market (Brazil and the Caribbean area).

Hence, these indexes suggest that there were differentiated patterns within a general upward trend for prices in Buenos Aires during our period. This divergence can be explained by several factors, such as the different types of commercial circuits or the various kinds of produce from quite dissimilar regions, the momentary substitution of certain goods, and the changes in the demand and supply of those goods, especially in the case of local products for the basic consumption of the local population. In addition, the Buenos Aires monetary and fiscal policies, along with the concomitant loss of value of the local paper money, would have boosted the observed evolution of prices, especially in the cases of the imported goods and the exports. In general, the prices of imported goods were more elastic to the downside than the prices of local goods.

The divergence of trends within the general rise would certainly have been related to other factors, which—despite the fact that they have not been yet measured—must be seriously taken into account for they were conditions of possibility for the government to maintain the circulation of unbacked paper money as a regular fiscal policy as part of a peculiar fiscal policy based almost exclusively upon the Buenos Aires customs house. This core institution of the local fiscal structure absorbed a fair share of the issued paper currency, though at an unbalanced pace. Moreover, among these factors we should pay attention to the complex balance of trade between the Buenos Aires economy and its far-flung regional hinterland, which we still do not know well enough. This vast economic area maintained an intense and growing exchange with Buenos Aires, with relative prices highly convenient for this commercial and financial hub on the Rio de la Plata. It seems very likely that such a favourable balance for Buenos Aires would have turned its economic hinterland across the region into a supplier of metallic money.Footnote 9

5. CONCLUSIONS

As several studies have shown, the prices of local products in late colonial Buenos Aires were relatively stable while the goods involved in overseas trade evidenced a downward trend during the first decades of the 19th century, and subsequently remained quite stable.Footnote 10 Such a relative calm was totally changed by the crisis of the Spanish colonial order and the free market commercial system that consolidated through the post-revolutionary era in the 19th century.

Throughout this paper we have demonstrated that for this period, the nominal prices of the main trade goods in Buenos Aires had a notorious inflationary increment after the short-term drop in the early 1820s, in spite of the global trend of reduction in the costs of overseas shipping. This upward curve was clearly influenced by the political and commercial conflicts in the Rio de la Plata, especially during the port blockades, but it was also affected by the general lack of political stability. An additional special factor for the local grain market was that of the supply restraints. So the general rise that started in 1826 and lasted until the mid-1830s reached an average rate of 400 per cent, only to be exceeded by extreme record increases with an average rate of 800 per cent during the second blockade in the 1840s, a juncture that combined the rises of imported goods and local products.

Although the general level of prices looks significantly high—and we must remember that there were peak rises of 1,500 per cent at special moments of crisis—, these average figures are still remarkably lower than the rates found in other studies available until now for the evolution of prices in 19th-century Buenos Aires.Footnote 11 Prices in Buenos Aires experienced a significant increase unlike those in other South American cities. So that at the same time that price inflation happened in Buenos Aires, other cities such Lima, Caracas and Santiago de Chile experienced deflation or low prices until the middle of the 19th century.

However, beyond the evolution of the general index, it is important to consider that the patterns of inflation for nominal prices were very divergent between the various baskets of imported goods, local products and exports in Buenos Aires.

For instance, since the mid-1820s, the prices of imported goods experienced a persistent rise but such a trend does not reflect the evolution of all the trade goods within that basket, for there were deep contrasts between the patterns of behaviour for South American imports—much more intense and volatile—and the goods imported from other foreign markets. Hence, in general terms, the main imported goods in the popular consumption basket ranked high on the list of price increases. Such goods included yerba mate, sugar or rice, goods without substitution and which were clearly inelastic. The case of other foodstuffs and textile goods, which found possibilities of substitution and were more elastic on local market, was very different; their prices experienced more moderate and less volatile increments.

The prices of local products also showed differentiated trends. On the one hand, the case of meat appeared exceptionally stable, with regulated prices and, more importantly, abundant supply in the context of the Buenos Aires cattle-raising expansion. On the other hand, the case of grains evidenced a minor increase until the mid-1830s, but from that moment on, recorded sharp rises until the 1850s.

Furthermore, the local prices of export products maintained a moderated trend of proportional increments with a lower volatility than other goods, beyond the juncture collapse they suffered during the blockades. The special circumstances of these port blockades must not be considered lightly in any analysis of the divergent patterns in the evolution of prices in Buenos Aires. Blockades had differential effects on supply and the possibilities of substitution for all the products under examination. However, in their long-run trends, the impact of the Buenos Aires port blockades was determinant for the general evolution of prices, as these conflicts had lasting effects beyond the temporary disruption of trade and its fiscal consequences. One of these effects that we have already mentioned was that of monetary disorder; the blockades disrupted customs revenue and, as an emergency measure, the Buenos Aires government resorted to the unbacked issuing of paper money, with the concomitant loss of value for the local currency. We have shown how the prices of export goods followed almost at par the evolution of the gold ounce rate and monetary emission. Likewise, the prices of imported goods from other South American countries also followed this trend, while the prices of the imported merchandise which had alternatives for substitution were less affected by this monetary factor. Local products also experienced increments due to other factors, such as the cycles of high and low supply or the characteristics of local demand in a context of demographic growth, and the regulation of the prices of certain basic foodstuffs by the government.

Finally, within this inflationary scenario, it is relevant to make some comments about the impact inflation had on the level of consumption across the region. Clearly, the inflationary process in Buenos Aires did not cause increments of prices for the inter-regional circuits linking the inland markets since they operated with hard currency (silver), and the value of silver currency evolved at a rate that was even higher than the increase of the general price index of Buenos Aires. Clearly, this was not the case for the domestic market in Buenos Aires, where the salaried sectors were clearly affected by the loss of purchasing power, especially for certain basic consumption goods. The inflationary process of the late 1820s and the 1830s can be noticed, as a sequel, in the substantial increments of wages during the 1840s.Footnote 12

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper has benefitted from the comments received from anonymous referees.

SOURCES AND OFFICIAL PUBLICATIONS

Informe sobre comercio exterior del gobierno de Martín Rodríguez (1978). Academia Nacional de la Historia, Buenos Aires.

Registro Oficial de la Provincia de Buenos Aires (1872). Imprenta del Mercurio, Buenos Aires.

APPENDIX

TABLE 1 PRICES’ INDEX