1. Introduction

The present article addresses the problem of the institutionalization of political science in Brazil. The process of institutionalization was conditioned by the country’s peculiar position in the geopolitical scenario of the Cold War, strongly affected by the influence of the USA and, later on, by the military dictatorship experienced between 1964 and 1985. During their youth, the first professional Brazilian political scientists were anti-Stalinist, revolutionary activists. They had been financed by the Ford Foundation (FF) to pursue their PhDs in the USA. The existing literature on this topic does not treat explicitly the problematic relationship of Brazilian intellectuals with the American funding bodies and academia. The common approach is based on underlining their supposed commitment to the funding bodies: “Brazilians had been seduced by the Ford Foundation and betrayed the left” or “despite being American, the Ford Foundation has financed our best leftist social scientists” (Lemos Reference Lemos2014; Figueiredo Reference Figueiredo1988).

In this paper I claim that one has to distance oneself from this type of approach. I argue that the North American model of ideological war included governmental and non-governmental institutions. Among the latter, the FF played a crucial role because it had ample credibility in the state bureaucracy and was able to captivate potential copartners, who would benefit from its funding, even the anti-American ones. The FF was able to do so because it kept its distance from the bellicose image of the USA (Calandra Reference Calandra2011; Chaves Reference Chaves2009). The FF’s conduct was consistent with the agency’s ambition to position itself as a promoter of global political balance (Holmes Reference Holmes2013, 50). In this way, because Brazilian youngsters were leftist, the FF was interested in financing their studies. And, because they belonged to the anti-Stalinist left, they were more open than the communists and would not oppose intellectual exchanges with American partners.

In the first part, I address the approximation between the main agents of the institutional and intellectual construction of political science in Brazil. In the second part, I describe the first part of the trajectories of these young revolutionaries; finally, I explain how the conversion to sciences they experienced while taking their PhD degrees abroad resulted in a reconversion to politics, experienced when they came back to Brazil.

2. The Ford Foundation and fractions of Brazilian elites

The key actors responsible for constructing Brazilian political science were: 1) foreign patrons (FF); 2) members of the traditional elites – who became its “institutional mentors”; 3) young students who were anti-Stalinist revolutionary activists, recruited by these traditional elites, to benefit from the FF’s resources – who then became the “intellectual mentors” of professionalized political science.

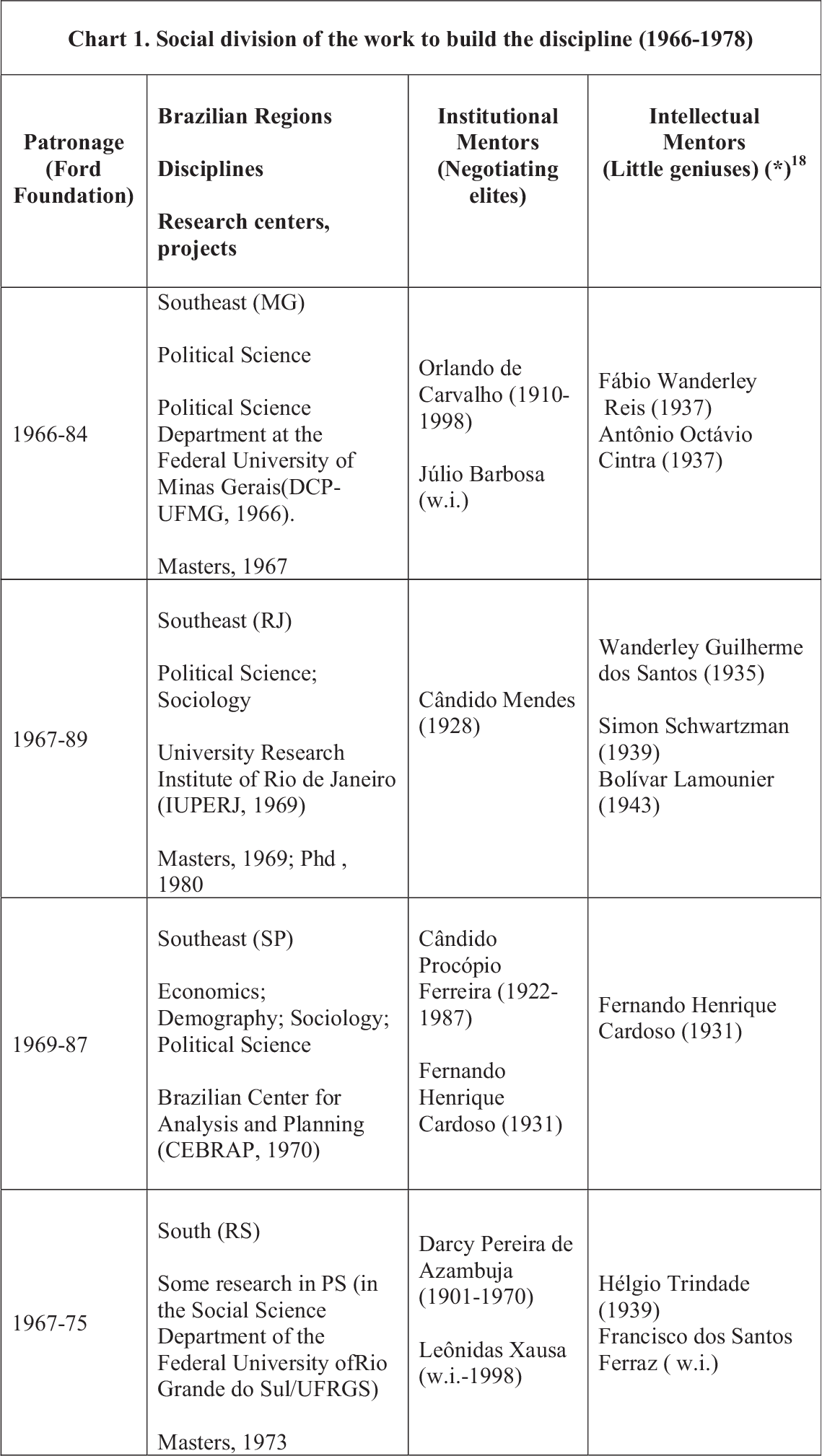

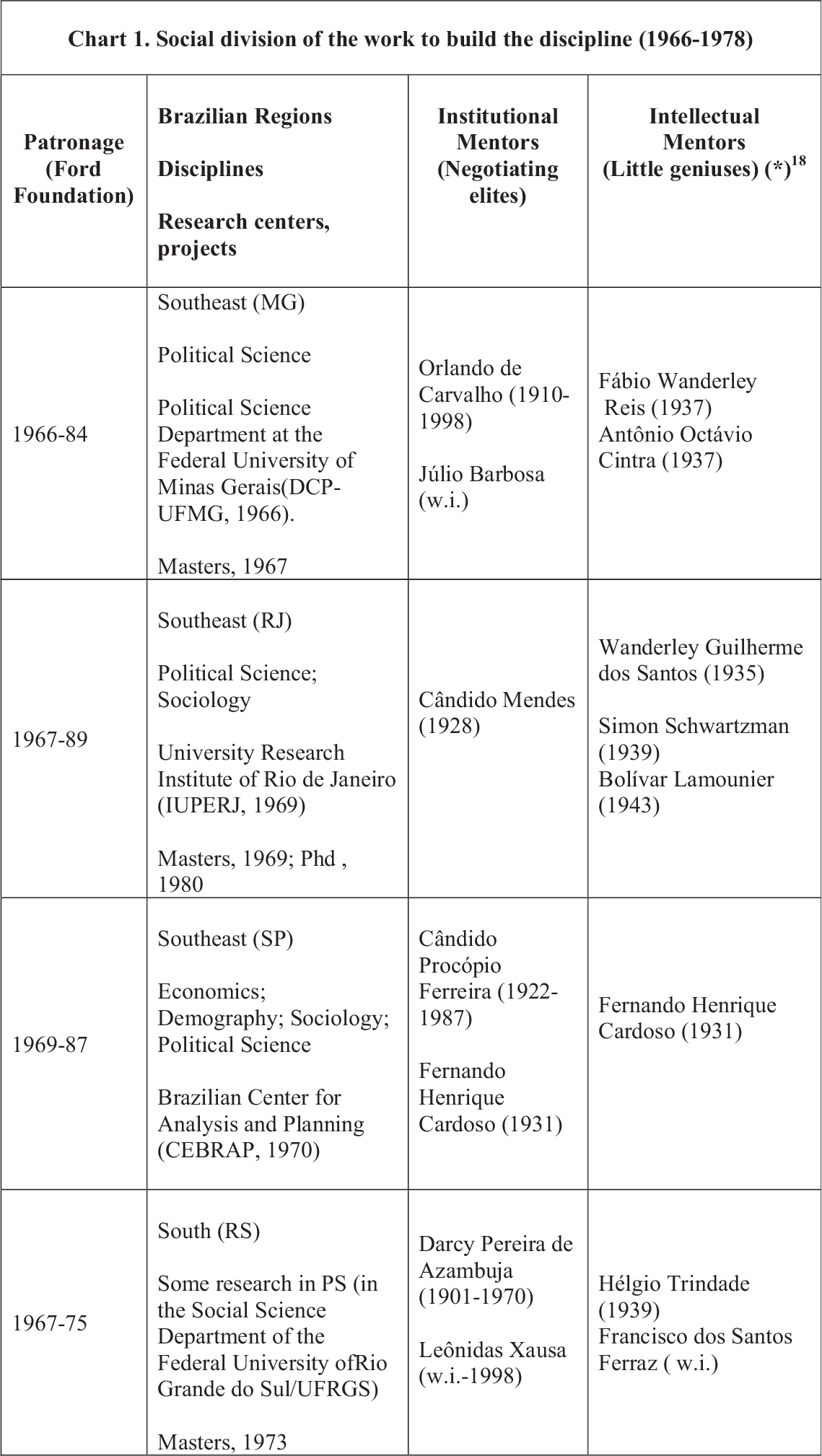

Each of these agents played specific, but different roles. The foreign patrons gave two types of economic support to Brazilians (grants to build research institutions and to finance PhDs in North American universities). The elites played a triple role: first, they negotiated the political license for institutional enterprises and made them feasible (since this could not be done otherwise due to the fact that the country was ruled by a military dictatorship); second, they managed the research institutions financed by the FF (this is the reason why one can call them “institutional mentors”); and third, since they were polymath teachers and educational entrepreneurs, they recruited students with an outstanding academic achievements and referred them to the FF’s representatives. These students became the first professional Brazilian political scientists and were the ones who defined the key research problems when the discipline was at its initial stage (this is the reason why one can call them the “intellectual mentors” of Brazilian political science). (see Chart 1 in appendix).

The position these three agents held in the social and political context conditioned all of them to negotiate their ideological principles, minimizing the polarization that, at first sight, would block their mutual alliances (Canedo 2012). These alliances confirm a trend that is common amongst the ruling elites of dominated countries: their international connections are conditioned by the domestic struggles they hold to maintain their positions (Sapiro Reference Sapiro2013). The following section addresses the relationships between the first two agents (Chart 1, 1st and 3rd columns); the next one deals with the third agent (Chart 1, 4th column).

In 1964 Brazil suffered a military coup, which was a reaction to the reformist measures of its former governments. The military took over the executive branch of the government until 1985 when José Sarney (b. 1930), a civilian, was elected by an indirect vote of the Congress as the President of the Republic. During the next twenty years, the military dictatorship was characterized by political persecution of leftists, massive investments in technology and sciences, rapid economic modernization focusing on the industrial sector, a modernization which combined domestic, state and foreign investment.

From the 1950s to the 1980s, the presence of the USA in the Brazilian educational system was progressively consolidated. The partnerships between the Brazilian government and the USAID (United States Agency for International Development) had been established in the 1950s. In 1965, the agency established a consortium with the MEC (Ministry of Education and Culture), directing resources to primary education. However, the military dictatorship focused on higher education.

In 1968, despite widespread protests by university students, the government promoted a “University Reform” (RU), resulting from a consultancy offered by USAID to the MEC. The RU led to a consistent increase in the number of university posts for students, especially if one considers the small density of the Brazilian market of diplomas and courses at the time. Between 1960 and 1980, enrollment in the Brazilian higher education system increased by 1,400 percent (Miceli Reference Miceli and Miceli1995, 17). The increase in the number of vacancies at this level implied training teachers and researchers to work in higher education. This is why, at this level of education, the dictatorship regulated, nationwide, the system of research through the creation of “post-graduation programs” (PPGs), which granted Master’s and PhD titles, offered by universities and research centers, both private and public, namely free of charge. To do so, the state created organizations aimed at financing and regulating research. Some of these already existent since the 1950s, such as the CNPq (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development) and CAPES (Coordination for Improvement of Higher Education Personnel), both connected to the MCT (Ministry of Science and Technology) and the MEC (Ministry of Education and Culture). Other organizations, like the FINEP (Studies and Projects Funding), established in 1967, were promoted by the dictatorship (Forjaz Reference Forjaz1989).

Among them, CAPES stood out because, since its establishment, it was responsible for the constant authorization and evaluation of the PPGs courses of all the institutions willing to confer Master’s and PhD titles (both public and private; Brazilian or foreign). All the institutions listed above were decisive to regulate teaching and research. Their importance in financing only became prominent in the middle of the 1970s (Martins Reference Martins2018; Patrus, Shigaki, Dantas Reference Patrus, Belintani Shigaki and Cabral Dantas2018; Miceli Reference Miceli and Miceli1993, Reference Miceli and Miceli1995).Footnote 1 Until then, the most advanced research in the field of social sciences relied on the sponsorship of foreign organizations. The most important was the Ford Foundation.

With the creation of its office in Istanbul (Turkey) in 1960, the globalizing strategy used by the FF consisted in establishing itself in areas bordering communist regimes. The alignment of the “Cuban Revolution” with the Soviet state encouraged the foundation to direct its economic and intelligence resources to Latin America, just as the State Department of the USA was doing (Calandra Reference Calandra2011). As a consequence, the Brazilian office was established in 1962, as well as the Chilean, Mexican and Nairobian, in accordance with the guidelines of the Salzburg Seminar. The FF was interested in exporting to Brazil the North American rationale concerning political and economic development (Holmes Reference Holmes2013, Pollack Reference Pollack1979). In order to acquire the desired penetration, the plan would have to be put into action with the assistance of individuals interested in intervening in the future of Brazilian society. This was a subjective input for the commissioned contract to “fix brains” by financing and training intellectuals to have an international career of which the USA was the epicenter.

The ideal partners to fulfill these goals were mainly leftists and nationalists. To put them sincerely at the service of American rationale regarding political and economic development, no ideological control could be imposed (Iber Reference Iber2015; Gremion Reference Gremion and Gemelli1998). Nevertheless, the “absolutism of freedom” had margins: an anti-Soviet one (that brought FF closer to anti-Stalinists) and a non-McCarthyist one (that distanced them) (Guilhot Reference Guilhot2005, 62). The FF financed grantees trips to the USA and allowed them to choose the university and host-professor they wanted. Socially, FF’s philanthropy depended on mediators to bring it closer to its target beneficiaries. The elite members played this role in the four states in which the institutions were built. Three of them were in the southeast: in Minas Gerais (MG), the DCP-UFMG (Political Science Department of the Federal University of Minas Gerais, 1966); in Rio de Janeiro (RJ), the IUPERJ (University Research Institute of Rio de Janeiro); in São Paulo (SP), the CEBRAP (Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning). In the south of Brazil, the state of Rio Grande do Sul (RS) was granted with inputs in the field of political science within a sector of the Department of Social Science of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS).

Orlando de Carvalho (MG), Júlio Barbosa (MG), Cândido Mendes (RJ), Cândido Procópio (SP), Fernando Henrique Cardoso (SP), Darcy Azambuja (RS) and Leônidas Xausa (RS) were recruited to exercise political control and maintain ties with the traditional business world. They held undergraduate degrees in Law, had close ties with Catholic groups, were very motivated to work for social and intellectual innovation, and had previous experience in institutional management and in international circuits (Canedo 2015; Forjaz Reference Forjaz1997). From the ideological point of view, they were opposed to the military dictatorship. For this reason, they were persecuted by the regime, compulsorily retired, and forbidden to teach. However, they were less likely to engage in the radical opposition that attracted younger student activists.

They originally aimed at exercising power but, faced with economic and social challenges, they had to find alternative strategies in order to maintain the positions held by their families. They had to adapt to the new moment, that is, to the new dominating social division of labor imposed on traditional elites by modernization and the emerging social groups. At the basis of this adaptation there was a solid capital of family relationships with ramifications in education institutions and political organizations (some of them, ruled by Catholics). Not entirely politicians, nor scientists, their hybridism corresponded to the phase of adaptation of the local ruling groups to the new conditions of domination. This profile enabled them to mediate the relationships among the national political elites, international bodies and young leftists. These men belonging to the elite were interesting for the FF, and the FF worked as a political shield for them. They carried out the necessary political articulations within the government of the military dictatorship, to which they had privileged access, due to their family relationships. A kind of calibration occurred: on one hand, their proximity with young radicals turned them into suspects; on the other hand, their proximity with the FF protected them.

These tensions explain the role performed by Peter Bell (1940-2014), who was the charismatic representative of the FF in Brazil from 1965-1969. He had been able to circumvent the two sources of suspicion that fell upon him. On one hand, he kept his distance from the strong anti-Americanism present in various ways amongst Brazilian social scientists (intensified by American support for the 1964 military coup and by the MEC-USAID agreements); on the other, he avoided the distrust of his superiors in the FF. His ability to conduct a peaceful approximation of expectations was evident if we observe his actions within the Brazilian political panorama. As of 1964, the year in which the military dictatorship was established, the FF tried to move away from initiatives connected with American foreign policy in Brazil, aiming to disconnect its image from American imperialism. Simultaneously, by means of interpersonal relationships, Bell moved closer to the persecuted members of the elites. This approximation resulted in economic and political inputs to Brazilian political science (Keinert Reference Keinert2011, 132). There were two types of economic aids: inputs directed at the establishment of institutions and scholarship grants that financed PhDs in North American universities (Miceli Reference Miceli and Miceli1993). The recruitment performed by the alliance between the FF and elites structured the discipline, because: 1) it delimited the research agenda; 2) it defined the principles of appreciation/depreciation of academic work; and 3) it defined legitimate/illegitimate modalities of participation of political scientists in the extra-scientific field (and vice-versa).

3. The Americanization of Soviet Hearts

The bifurcation between science and politics structured the stages of social aging of the “intellectual mentors” of Brazilian political science. In their youth, they approached political life following two paths. Either through radical ramifications of traditional catholic associations: JUC (Catholic University Youth) and AP (Popular Action); or through radical ramifications of communism: POLOP (Marxist Revolutionary Organization-Labor Politics) and MRT (Tiradentes Revolutionary Movement). All of them competed with the PCB (Brazilian Communist Party) in the recruitment of militants. What characterized anti-Stalinist revolutionary organizations was the fact that they were comprised of small and unarticulated groups and their principle of segmentation was that they were opposed to the communist left. This case is no exception. JUC, POLOP and MRT intended to represent a leftist alternative to the Stalinism of the PCB. The presence of the proletariat in these groups was very small, as usual. However, they gathered members of the ascending classes and younger individuals from immigrant families, while the PCB gathered leftist members of the army and descending classes (Rodrigues Reference Rodrigues and Fausto1981, 372; Ridenti Reference Ridenti1993, 147). The social context was the determinant factor in grouping the revolutionaries on the left of the left.

In MG, until the 1950s, the market’s competitive dynamism was not yet present, and the variety of professional opportunities was reduced. It was the land where families compensated for their economic stagnation by manipulating political opportunities in the state (Miceli 2001; Wirth 1982). It is not surprising that these students of modest origins, without social support, ended up in less stable spaces, the ones of social sciences and radical leftist groups. Fábio Wanderley Reis and Simon Schwartzman belonged to the POLOP; Antônio Octávio Cintra and Bolívar Lamounier belonged to the AP. All of them faced some kind of political-police persecution in 1964 (Canedo, 2015; see Chart 2 in appendix).Footnote 2

The distinctive feature proper to this group was the investment their families had made in their basic education, which resulted in high performance in their university studies. All of them were granted scholarships for their undergraduate diplomas, which were followed by recommendations on the behalf of their teachers to be recruited by the scholarship programs of the FLACSO (Latin American College of Social Sciences) in Chile, sponsored by the UN (United Nations). Professors Carvalho and Barbosa recommended them to represent foreign organizations who travelled for the diffusion of UN institutions (Beigel Reference Beigel2009, 327). Before taking their PhD degrees in the USA, they had already received some sort of warm-up to enter the universe of international schools and training. All the individuals in question followed this path in MG before going to the USA. The first international experiences marked them: the insertion into a universe above their expectations of social achievement triggered the rupture with political militancy and, as a rule of thumb, success became the driving force of their pursuit for more success. It’s no accident that, this group was nicknamed by their colleagues “little geniuses” (Arruda Reference Arruda and Miceli2001, 320); and they self-defined themselves as an “elite,” dating back to the first years of their educational training:

it’s necessary to make a distinction: the regular course and the elite of the course (who were we, the) scholarship holders …. The morning lectures were followed by an afternoon of intense studies, (we) were atypical students, because we had a lot of activities, besides political participation in the Catholic movement, in the Marxist movements, or in the UNE (National Union of Students).

Among the effects of the “warm-up” promoted by going to FLACSO, it is worth pointing out that some scientific conceptions started to be ingrained and encouraged to be defended. The freshly graduated Fábio Wanderley Reis was particularly hostile to the main group of social scientists who were mature and held national reputations at the time. His positions are paradigmatic.Footnote 3

Fabio Wanderley Reis against Philosophy, Sociology and the University Marxism practiced at the University of São Paulo (1966):

[the predilection for] issues dealing with ‘the methods’ … – constitutes an aspect [of our] underdevelopment and [of our] immaturity … ; … (Brazilian social scientists treat) empirical work as … an “inferior task” and the dialect totalization as the “true noble moment.” (Reis Reference Reis1966, 298)Footnote 4

What happened in RJ was similar, given that the young social scientists were as well considered “little geniuses” because of their school performance and their political radicalism. Wanderley Guilherme dos Santos was born in the city and, due to his modest origins, did not have the social capital that was needed to integrate the cultivated, elite-oriented, and politicized space of intellectual life. His initial education was not in the social sciences, but in philosophy. Just like his homologues from MG and RS, his militancy took place among students and in an anti-Stalinist movement (MRT). However, the city and this case are peculiar. Until 1961, RJ was the political capital of Brazil and the headquarters of the two central institutions of national intellectual life, attracting leftist intellectuals – the Brazilian Communist Party (PCB); and the Superior Institute of Brazilian Studies (ISEB), from MEC, gathered leftist military and generalist intellectuals who wrote essays about national development. This explains why before joining the MRT, Santos militated in the PCB for a little while; this explains as well why his school achievement opened up a way for an invitation to join the ISEB. Entering this universe gave Santos visibility even before migrating to the USA. The ISEB was shut down in 1964 by the military dictatorship. Cândido Mendes and Santos also faced political-police coercion.

In RS, the major figures – Leônidas Xausa, Hélgio Trindade, and Francisco Ferraz – belonged to the AP. However, they were not so modest (as the others) and differed from them for having chosen a degree in Law and by having closer social ties with the local ruling elites, which were merged with the ecclesiastic ones. As with the others, they faced political-police coercion.

The “little geniuses” – young men of modest origins and excellent school achievement, from MG, but also RJ and RSFootnote 5 – engaged in types of militancy that were brief and intense: brief enough not to prevent them from taking other paths and, at the same time, deep enough so that they could incorporate to their ethos principles of social solidarity and a relatively idealist point of view regarding social change. Gradually, but at a fast pace, the relation between cost and compensation (material and symbolic) of the two types of commitment shifted the balance towards science instead of revolutionary politics. The range of opportunities offered by the commitment to their studies was equivalent to the political persecution their close friends were facing. For this reason, although the scientific field posed uncertainties, it seemed to be more promising than the spheres of politics and radical militancy.Footnote 6

Their conversions did not result from trips to the USA, but from their previous positions and dispositions. The double domination (the fact that they belonged to the left of the left and had an uncertain professional future) conflicted with the impulses for professional ascension driven by school success and the emergence/opening up of new opportunities, which motivated their adaptations.

Loneliness of foreign doctoral students in the USA

“I left Brazil in 1967, when I was more or less a public figure […]. I suffered […], there (in Stanford), I was simply a Latin-American.”

(Santos Reference Santos2004, 39).

Thematic freedom, low integration in the USA, maintenance of restlessness

“Who was your doctoral dissertation advisor?”

“I think it was Heintz.”

“How did you choose the topic?”

“I think it was in my mind. The topic of my dissertation back then was based on a research study I had conducted with workers […] it was something related to workers’ political awareness.”

(Schwartzman Reference Schwartzman2010, 7).

The maintenance of militant origins is flagrant: the declaration made decades later maintains the lexicon that comes from Marxism, “consciousness of the working class”.

These young people took their PhDs in different institutions, with different doctoral advisers. From a scholastic point of view, this isolation would be the ideal condition for their studies. However, from a sociological point of view, the distance from their home country and reference group, associated with no integration with other groups in the USA, was the ideal condition to maintain the content of the intellectual concerns they had brought from the previous stage. In other words, the themes would range between radical political militancy and commitment to their studies. The topics addressed in their dissertations made this evident and highlighted the physiognomy of the kind of “Cold War” proper to the situation, triggering the interest of foreign professors. And some of them already were “democracy makers” (Guilhot Reference Guilhot2005; Joignant Reference Joignant2005; Chart 2, Column “Exile, PhD degrees”)Footnote 7.

These people were exposed to new models of reasoning and their reactions are/were comprehensible. In response to the social isolation and scientific training, they tried to give new shapes (American-like ones) to the issues forged during their militancy (Soviet-like ones).

It is this path that transformed the old bet on the “revolutionary awareness of the proletariat” into investigation of the nexus between “economic development, social classes and political development” (Reis); this path transformed the defeat of the left by the military coup into an investigation of the “impasses and political crisis of 1964” (Santos); it transformed the bet on the awareness of the masses into an investigation on the nexus between “ideology and authoritarian regimes” (Lamounier); and, of the Brazilian right wing in previous periods (Trindade) (Chart 2, Column “Exile, PhD degrees”).

Principles of intellectual and political appreciation

(1) Americanizing against Europeanizing

“The mechanics of post-graduation training in the United States is a true machine. When you leave, you’re different, there’s no way out […]. We wanted to really modernize [we saw that we could help and] we shared this opinion.” (Santos Reference Santos2011, 33).

“The differences between left clichés and what we were experiencing were shocking. You would arrive in a fantastic university, you engaged in incredible discussions […but] we would meet the great leftist thinkers of the United States: we met Paul Baran, who was a best-seller in Brazil, and the conversation seemed to be so uninteresting […] we were very disenchanted […] [the great leftist American thinkers] didn’t add anything [while all the rest did] […] [the US was] a country that exhaled freedom, pluralism, discussion, interesting things happening” (Lamounier Reference Lamounier2013, 11).

(2) Empirical work against dilettante Marxism

“Scientific work has lately been overloaded with ideology and programmatic intentions […] [a distinction between science and politics] should be present at a college of… show less about the suffering of our country‘s people and make deeper analysis of work relations in the countryside, etc. […] I don’t think it’s about discussing the validity or not of … dialectic sociology [Marxist]. This type of discussion is seducing, fits well with a type of “intellectual-oriented” education, but can be quite sterile… we should […] set aside the construction of a more […] philosophic aspect. […] the alternative to overcome the “deep crisis of leftist thinking […] is not discussing about it, but overcoming it, thinking about another style of activity […] I apologize for repeating obvious things.” (Schwartzman Reference Schwartzman1965).

“(…) (one of the) hindrances to knowledge on politics (…) is a scholastic variant of Marxism”; it (despises) the pedestrian, modest and tiresome work of patient research left to empiricists and functionalists” (Santos 1979, 25).

(3) From “radicalization as a prophecy” (1962) to “radicalization as a danger” (1973)

“The solution is not to undermine (…) the popular movement, but (…) make it advance (…). The popular forces will never convince the privileged majority (…)” (Santos 1962, 43 – before his PhD).

“(the objective of this thesis is to explain) the dynamics of political competition, (…) the model defines, by describing polarized systems, that a crisis of decision paralysis is the most likely result of political struggle when power resources are dispersed among actors who have radical positions (…) the period between 1961-1964 was characterized exactly by transforming a reasonably operational political system into a system incapable of producing decisions about the most compelling issues of that time” (Santos Reference Santos1986, 10 – after his PhD).

(4) Utopian market equality

“Capitalism is socially democratizing (…) (within the market, the search for interests presupposes) a principle of solidarity and compliance with the norms that regulate it (…); (this is why it can) “be the reference point of a kind of ‘realistic utopia’.” (Reis 1991, 215-229).

I emphasize here the selective principles that drove the conversion and the process of import. The conversions resulted from the combination of previous conditions and the range of scientific assets. In the case of the imports, the national tradition and the political panorama favored some and neutralized others.

4. Libido sciendi

Established by a clause in the agreement with the FF, the return to Brazil characterized the next stage of the trajectories of these people – a stage when they passed from the condition of “little geniuses” to being the first generation of professional Brazilian political scientists, which implied practices consistent with it. The homology of their positions and their responsibilities synchronized the different conducts. The intellectuals reacted in the same way facing the difficulties of the construction of the discipline, although they never planned it.

“it was then that I took the lead (of IUPERJ)– (and it) was Americanized”; “it still had very few people and I invited people from outside to participate” (Santos Reference Santos2011, 32)

“(at CEBRAP there was) an endless discussion about the use of statistics in social sciences (…) questioning if it wasn‘t inherently ideological and conservative. Can you think of a greater nonsense than this? (…)” (Lamounier Reference Lamounier2013, 58).

During the military dictatorship, elections (for councilmen, congressmen, mayors and governors) were not suppressed. There was an opposition party that was allowed to exist, the MDB (Brazilian Democratic Movement) and the pro-dictatorship party, the ARENA (National Renovating Alliance - ARENA). The latter always won these elections. In 1974, there were elections for senators and congressmen. Lamounier took part in the preparation of the MDB’s campaign that led the polls in SP.

In this state, the MDB leader, Ulysses Guimarães (1916 – 1992), contacted the CEBRAP.Footnote 8 Fernando Henrique Cardoso, CEBRAP’s charismatic leader, advocated in the press that voting for the opposition (MDB) would increase the available channels of institutional political manifestation. He discouraged the “null vote,” which was a form of protest that, according to him, delegitimized the entire electoral system. Excited with this idea, Guimarães asked CEBRAB to write the MDB’s campaign platform. Among others, Cardoso and Lamounier participated in the writing of it. From this moment on, the MDB achieved surprisingly successful results. For example, in the 1974 legislative elections, out of the 22 posts in the Senate, 16 were won by the MDB. The political scientists reacted, excited by their own involvement in the elections and by the idea of the problem that had been formulated by Santos in his thesis: how to convert the authoritarian regime through “a partial and successive solution of conflicts?” (Santos Reference Santos1978, 7).

Without previous arrangements, Trindade conducted the same electoral poll in RS. In the meantime, Reis replicated it in Belo Horizonte (at the DCP-UFMG). Although the conclusions of the research could not be the only reason for this enthusiasm, the MDB’s victory was the sign of the efforts made by the intellectual and political elites in order to seek alternatives for reestablishing democracy through conventional means – that is, “non- revolutionary” ones, namely a solution that did not imply an armed conflict. The background of fear of practices that were against the social order was notable. Moreover, evaluations regarding future expectations were negative; but regarding the present, positive.

The unplanned alignment among the first professional Brazilian political scientists gave place to calculation. The DCP-UFMG promoted the seminar “The elections and the institutional problem” which aimed at standardizing poll tools to analyze the 1976 elections. Voting intention questionnaires were applied in various cities (in MG, SP, RJ, MG), which were then chosen on the basis of morphologic features (Reis Reference Reis1978, 4).

The authoritarian regime controlled the process of democratic opening by manipulating the electoral rules. For the 1976 municipal elections, it created the “Lei Falcão (Hawk Law)” restricting propaganda, reducing, therefore, the chances of the opposition; for the 1977 election, it launched the “Pacote de abril (April Pact),” which reduced the weight of the vote in regions where the opposition tended to win. For the 1979 elections, due to the growth of the opposition, the regime eliminated the two-party system, aiming at segmenting it into many parties and, consequently, acquiring greater strength. In each election, new research studies were produced, aiming to thoroughly understand the logic of the process (Reis Reference Reis1978).

Mid-way through political analysis and intervention in the political choices of individuals:

“there weren’t, at that time (electoral polls)” (…) so I conducted the poll, working 16 to 18 hours a day, with students, visiting shanty towns, interviewing people… once the elections finished the results corresponded to what I had forecasted. (…) We conducted it in 1974, 1976” (Lamounier, Reference Lamounier2013, 29).

Tightening the ties facilitated other joint undertakings. In 1977, the Americanized political scientists joined other FF beneficiaries and fought to set up the ANPOCS (National Association of Post-Graduation in Social Sciences). Once again, the strong ties with the FF helped them to build and monopolize the main professional association of social sciences in Brazil (Keinert Reference Keinert2011). The ANPOCS had three presidents who belonged to the group of “intellectual mentors”: Reis (1981), Santos (1983) and Trindade (1985). Reis and Santos received awards from this institution. In 1985, the ANPOCS awarded the “Best Scientific Work” prize to Política e racionalidade (Politics and rationality), by Reis; in 1987, to Sessenta e quatro: anatomia da crise (Sixty-four: anatomy of the crisis), a translation of Santos’ PhD thesis.

The elections that shook the dictatorship (Senado 2014)

“(it’s necessary to act) within these limits – narrow ones – of a real conditioning of this stumbling political life (…) if there’s a failure (because it seems that there are diverging interests instead of ‘failure’), these limits come from either myopia or cleverness (which sometimes are the same thing) of the political elites that do not want to face the real problems of representativeness and democratization. They originate from the need to recognize that in an urban society that is undergoing industrialization, characterized by the active presence of workers and wage earners and by a diversity of groups, classes and class fractions, the symbolic homogeneity of the old democracy of elitist clubs, ‘Republica Velha’-style, or even, 1946-style, is impossible” (Cardoso, Lamounier Reference Lamounier and Fernando1978, 13).

Comfort and political engagement: “From the point of view of the effective exercise of democracy, it’s not important to consider the obstacles that had been overcome, but the distance that we still have to cover to reach the goals completely materializing the regime” (Martins Reference Martins, Lamounier and Cardoso1978, 78).

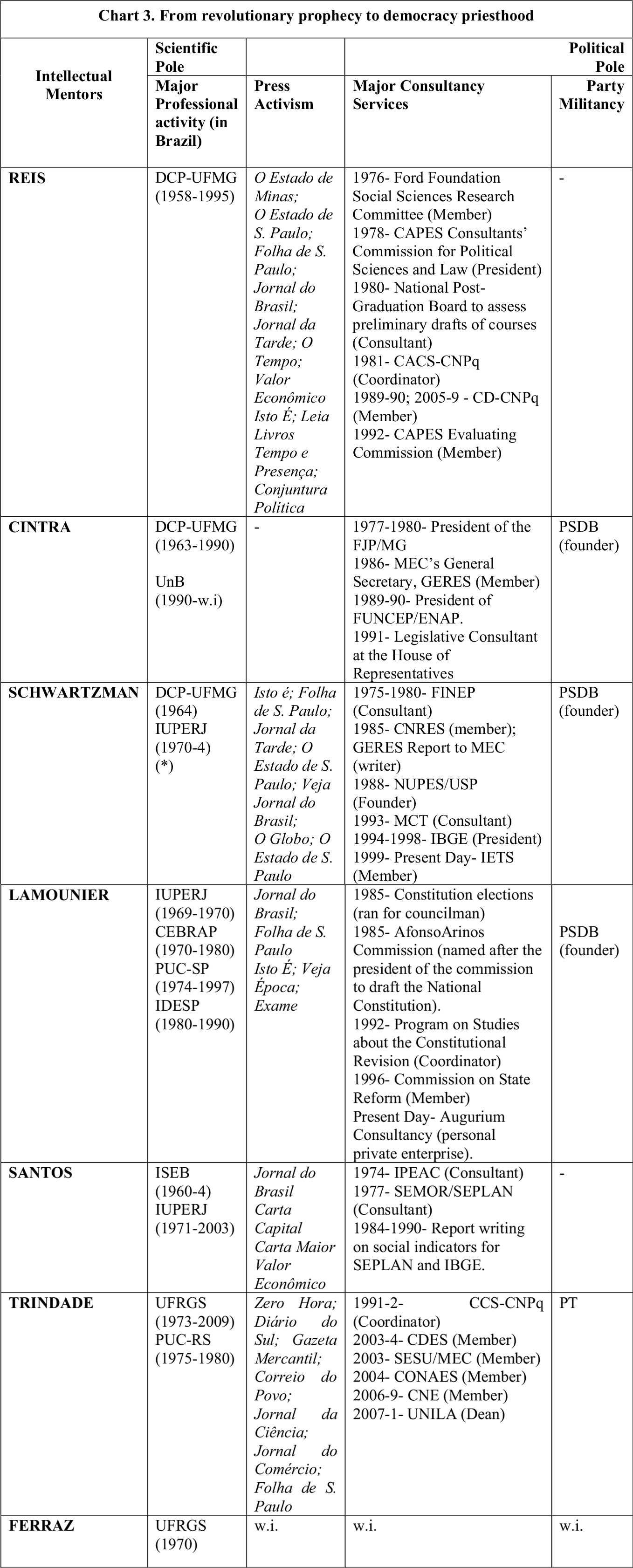

The FF’s inputs reconfigured the Brazilian social sciences, reinforcing previous asymmetries. The struggle fought in order to impose principles of scientific assessment did not eliminate the adversaries of political scientists competing to occupy a central place in this space and in the practice of political engagement. However, they managed to overcome their favorite adversaries, the Marxists, who were occupying teaching positions in less prestigious institutions (Rodrigues Reference Rodrigues2016; Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1984). The fraction which is the object of this article, confiscated the monopoly of political engagement, which was held by the Marxists until 1964 (Rodrigues Reference Rodrigues2011). In the press, this “professionalism” granted legitimacy to their interventions. These agents followed the political situation and translated the complex language of professional political sciences into accessible analysis by wise laypeople (see Chart 3 in appendix). In the state and in the parties, molecular changes combined with this social sensitivity. On one hand, there was the need of renovating party members and formulating new expertise able to manage the state apparatus; on the other hand, there was an availability of demand for social scientists, who were skilled due to their specific training. Furthermore, the agents were predisposed to join the political field, given that the inculcation of the ethos of political engagement was converted into availability to render consulting services to state organs and stand for democracy. These aspects brought some of them closer to political militancy. This movement actually often led them to abandon the scientific field altogether.

The first stage of these peoples’ careers was therefore connected with the establishment of the military regime and the repression of their revolutionary aspirations, which occurred simultaneously with their investment in achieving success through student merit. The second stage took place when they left Brazil to take their PhD degrees. The third stage was related to the responsibilities in constructing an intellectual discipline and their commitment to the process of re-democratization. In their life cycle, this corresponded to their fixation in geographic, disciplinary, ideological and sociological spaces. But in the political sphere, the range of opportunities was reopened. In this way, the attraction to politics dominated the last phase.

Science of politics: irresistible; political practice: irreversible.

“I’ve always written in newspapers (…) I don’t care about conducting research, writing puny little articles and publishing in academic journals” (Lamounier Reference Lamounier2013, 54).

5. Libido dominandi

The most successful case of conversion to professional politics is that of the intellectual and institutional mentor of the CEBRAP, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, who became substitute Senator (1978), senator (1983), member of the National Constituent Assembly (1986), Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1992); Finance Minister (1994) and, for two successive mandates, President of the Republic (1994-2002).

Preliminarily, it is worth pointing out the particular aspects of this trajectory and that of the CEBRAP in relation to the disciplinary institutionalization that is the object of this article. On the one hand, CEBRAP, which was also financed by the FF, differed from other institutions, insofar as it attracted political scientists, yet did not focus exclusively or primarily on political science and did not deliver Masters and PhD titles. On the other hand, Fernando Henrique Cardoso did not belong to the first generation of professional political scientists from the states of MG, RJ and RS, but to the first generation of professional sociologists, from SP. Moreover, if in the other institutions financed by the FF, the agents monopolized a type of scientific capital (or institutional power or scientific resources), at CEBRAP, Cardoso combined both (this is why he was its institutional and intellectual mentor). For this reason, his distinctive feature was the one of gathering together the attributes that the other agents had to share amongst themselves. These peculiarities resulted from a double ambiguity: compared to individuals of the “negotiating elites” of institutions outside of the state of São Paulo, he was the most professional since the “institutional mentors” of the former were polymaths. However, compared to the generation of “intellectual mentors” typical to political science, he was the least professional, since his entire educational background took place in Brazil and he did not get to know advanced research techniques in the field of sociology. The shift to political science took place in a transitory and circumstantial way, after graduating as a sociologist, in an advanced stage of his already consolidated career. Finally, as didactic practices were censored at the universities, the CEBRAP became a space of “consented freedom” for political debate; and, moreover, it was the institution that had the greatest circulation nationally: it included Brazilian intellectuals from many states guest visitors from abroad, invited by Cardoso. Due to these particularities, during the last years of the dictatorship, the first professional Brazilian political scientists and some members of the “negotiating elites” orbited around Cardoso. For this reason, the paths lading from academic to political careers can be understood through the reconstruction of Cardoso’s own career.

In the 1950s, at the FFCL-USP (Faculty of Philosophy, Sciences and Literature of the University de São Paulo), Cardoso was the right-hand man of Florestan Fernandes (1920-1995) – the intellectual leader of the Department of Sociology. He was responsible for the department’s arrangements, its institutional alliances, and fund raising initiatives. He performed this role skillfully, due to his ability to circulate within the elites and to his privileged capital of relationships (Rodrigues Reference Rodrigues2011, 432). In 1964, when the team began to be persecuted by the police, Cardoso fled in exile at first to Uruguay, then to Argentina, Chile, and, finally, to France, where he found the support of intellectual figures such as Alain Touraine (1925). After having published Dependência e desenvolvimento na América Latina (written with Enzo Faletto while he was at Cepal) he became the most well-known Brazilian social scientist. Upon coming back to Brazil (in 1969) he had already gathered experience in international negotiations and developed an important capital of external relationships that contributed to the economic feasibility of CEBRAP.

Cardoso was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1931 in a family of soldiers whose participation in the Brazilian political sphere dated back to the Imperial period (1822-1889). His father was a member of the nationalist branch of the military – eliminated from the political game in 1964. Just like any other heir of military families in his position, the first course he decided to study was Law. But he failed the Latin admission test to enter and ended up studying Social Sciences – typical case of a relegation course.Footnote 9 His social and family origins aligned him with the “negotiating elites” and “institutional mentors” of the political science course sponsored by the FF. However, his scientific training brought him closer to the first generation of professional political scientists – although his training had taken place a decade earlier, in the field of sociology, in São Paulo and with strong French and Marxist influences.

While he was exiled (1964-1968) in Latin-American institutions (Cepal, Flacso), however, he sought bibliographic references from North American political scientists and gradually disconnected from the Marxist readings he did in São Paulo as a student. The effects of this international experience are evident when we take into account his judgment on the new generations, guiding the evaluation of his own academic training, which was very weak concerning quantitative research techniques and highly theoretical – exactly what drove Reis, in Reference Reis1966, to oppose the intellectuals from São Paulo (Chart above, “Fabio Wanderley Reis against Philosophy, Sociology and University Marxism”).

Simon Schwartzman wrote, in a letter, to Fernando Henrique Cardoso :

let me tell you how I react to what you’re telling me …. [you complain of lack of] free time, positions and lack of enthusiasm of the ‘old’ group to which … you belong. I think [if we consider the current tasks to the youth], failure is practically inevitable. Simply because when you say ‘youth’ I hear ‘amateurism’ …. For better or worse, I am – we are – social science professionals, and only on this serious basis we can conceive, for instance, our participation in the creation of a journal …. Maybe because of bad Marxism, this distinction is hardly ever made by us, and the consequence is that scientific work is loaded with ideological intentions. (Schwartzman Reference Schwartzman1965)

Although incidental and therefore insufficient to turn him into a typical member of political science as a profession, this experience enabled him to become familiar with the lexicon, bibliography, and problems of the area. This is evident in a letter to Florestan Fernandes, who was thinking of a way of bringing him back to Brazil. He had already read enough to “sew” a bibliographic balance of political science with data gathered to address a problem different to that of the discipline. Not by chance, at CEBRAP, he coordinated polls on elections with Bolívar Lamounier.

I have the following alternative: I can “sew” a doctoral dissertation taking advantage of the inquiries about businessmen in the political section of the questionnaires and, along with an ad hoc elaboration of hypothesis about development and dependency I’m re-elaborating, basing myself on the work on Latin America that you are familiar with. Or I can write an essay in the fashion of the two first chapters of the book about the businessmen, making a critical review of political theories about development. There’s a huge modern bibliography, poorly divulged in Brazil, which would be useful to write a beautiful essay. (Cardoso 1967; emphasis in the original)

Once the chances to recover ruling positions reappeared, Cardoso did not hesitate. It was as if he was returning to the “natural” role he was prepared to play. This is why since CEBRAP’s participation in the electoral campaign, Cardoso had tightened ties with the MDB. He ran for the Senate in 1978, and was elected as a substitute. In 1983, Senator Franco Montoro was elected governor of the state of São Paulo and FHC replaced him in office as a senator. Two years later, he ran for mayor of the city of São Paulo, but was defeated. Winning or not, he accumulated advantages: he met the MDB’s rejuvenating demands and he became a true magnetic pole for his peers, who seized the opportunities opened up by his meteoric rise.

However, his peers were not as well equipped with resources to perform the reconversion (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1989) – and this asymmetry of resources implied different levels of ambition. Career reorientation, especially of the first generation of professional political scientists, geared to opportunities to exercise politics professionally, is inseparable from a double incentive to compete. On the one hand, there was an attempt to enforce and impose the modalities of intellectual excellence they possessed to the space of scientific practice; on the other hand, they wanted to impose their political-ideological conceptions and position taking – contrary to, not only “distant” from, their once revolutionary anti-Stalinist radicalism. A thorough examination of the trajectories highlights two decisive axes useful for two reasons. First, they can help us understand the entrance of the “intellectual mentors” into state organizations, the work performed by national agencies that fostered and regulated the teaching system, that is CAPES, CNPq, and FINEP (in the mid-1970s), simultaneous with affiliations in the network of FF’s own advisory committees. Second, they can be useful to characterize the attraction to the exercise of political practice of both “intellectual mentors” and “institutional mentors,” highlighting their participation in the preparation and drafting of the Constitution (1986-1988). The next section focuses on these two axes, because what happened resulted from these two types of approximation to the state – and, in both of them, the concentration of power in the image of Cardoso and resources (material, symbolic, and institutional) in São Paulo.

Throughout the period covered by this article, the proportion of economic resources from the FF in the total financing of social science research in Brazil was variable. Up to the mid-1970s, the FF was its main source of promotion. However, as of 1974, CNPq, CAPES, and FINEP partially replaced it. On the one hand, the first two institutions granted scholarships for PhD degrees abroad, awarding individuals according to their student merits, that is, the same criteria adopted by the FF previously. On the other hand, the last two institutions directed resources to non-individual entrepreneurship, to institutions (be it to conduct research projects, offer institutional or infrastructural support to build libraries, buildings, etc.). In view of these changes: a) the FF redirected and diversified its grants in Brazil (as of 1979, it started fostering cultural associations and sectors of basic education) (Miceli Reference Miceli and Miceli1993). And b) in 1984, it commissioned the Anpocs the task of administrating and allocating the resources granted by it (Figueiredo Reference Figueiredo1988, 39). On the one hand, this shifting role reveals the level of integration among Brazilians and Ford’s representatives; on the other hand, the gradual complementarity established between foreign and domestic sponsorship resulted, partially, from the simultaneous performance of a fraction of the generation in advisory and deliberative committees of all of those organisms (see Chart 3, column “Major consultancy services,” especially in the case of Reis, Cintra, and Schwartzman, between 1975 and 1980, who were members of committees at Capes, CNPq, Finep and FF).Footnote 10 Little by little, the fraction of the scientific community which the FF had invested started to work in these state institutions. Schwartzman had close ties with economists – because they had been, just like him, “revolutionaries during their youth,” and also FF’s beneficiaries – who worked in organisms of the management of national economic development, like the BNDES (National Development Bank). They changed the way other people could access positions in the FINEP, the MEC, and the MCT.

Furthermore, in 1976, CAPES began to allocate state funds for research in addition to validating, evaluating, and ranking PPGs courses (Patrus, Shigaki, and Dantas 2018, 646). In the core of this institution, the dispute to define the criteria of performance of excellence in the PPGs, pillars of this hierarchization, turned into a dispute to gain the very economic resources. Capes became the most conflictual and strategic arena in imposing certain definitions of scientific excellence at the expense of others (Martins Reference Martins2018).

The fraction of the generation who succeeded, with this strategy, to change the rules of the professional game and standards of academic careers had then the ability to enter and stay inside the field (Forjaz Reference Forjaz1989, 72; Figueiredo Reference Figueiredo1988, 54). It is not by chance that the following events happened simultaneously: at the final stage of ascension of their careers, they were redirected to the state apparatus and there was an increase in the number of scholarships and positions in higher teaching – distributed according to their legitimate scientific conceptions and principles. At this stage, it is possible to observe an expansion of the surface of social circulation, interaction and accumulation of social relations in their trajectories – which brought them close to the multipositionality of the elites (Boltanski Reference Boltanski1973) as this practice is configured in the Brazilian experience (Rodrigues and Hey Reference Rodrigues2017, 25, 33; Almeida and Hey 2018, 290 and 305).

With regards to the second episode, the elaboration of the new Constitution, it is also worth unfolding the type of engagement of these agents. Between 1986 and 1988, Brazil elaborated a new Constitutional Charter and the force of attraction of the political field over social scientists became evident.Footnote 11 Among others, Cardoso was elected as a constituent congressman, by the MDB, in SP. Then, in 1988, he broke with this party and founded the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB) – supported by old MDB members and intellectuals who became the PSDB’s activists (Cândido Mendes, Bolívar Lamounier, Simon Schwartzman, and Antônio Octávio Cintra).Footnote 12

In 1992, after the impeachment of Fernando Collor de Mello who was the first president elected by direct vote, Cardoso was appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs and, right after, Minister of Finance. Lamounier was well-known for the pioneering election polls he conducted. In 1980, he decided to raise funds to establish his own research institute, the IDESP (Economic, Social and Political Studies Institute of São Paulo). The composition of his capital of relations would gradually be comprised more and more of jurists and economists (Chart 3). During the preparation of the new Constitutional Charter, he was invited by president Sarney to take part in the “Arinos Commission to elaborate the draft of the National Constitution.” Far from scientific obligations, but very close to the academic elites, Cardoso became a passionate advocate of the PSDB. In 1992, he coordinated the Study Program on the Revision of the Constitution at the IEA (Institute of Advanced Studies of University of São Paulo). At that time a plebiscite on the option for a parliamentary regime was proposed.

As Minister of Finance, Cardoso put together an economic and political science team to create the “Plano Real,” whose main achievement was to stabilize the currency and control the rampant inflation of the 1980s. In the most crucial moment of FHC’s political career, the implementation of the “Plano Real,” Schwartzman became the president of the IBGE (Brazilian Geographical and Statistical Institute) – the government organ responsible for measuring inflation. The success of the “Plano Real” led Cardoso to be elected as the President of the Republic, a position he occupied during two terms (1994-2002). Lamounier was a member of the “Commission for State Reform” during Cardoso’s government (Loureiro Reference Loureiro1997).

Party practice, party speeches

I’m for the PSDB…. You can’t imagine how many times I have crossed the state of São Paulo, driving on my own, many times, early in the morning, in the middle of crazy storms … in order to form the PSDB’s directories. Hundreds of times, since the beginning. Hundreds of times…. a huge personal effort. I still do this…. (my point of view about the transition from dictatorship to democracy is that the 1974 elections) were the starting point of everything. (Lamounier Reference Lamounier2013, 37)

We are witnessing an historical moment in Brazilian higher education: the president is sanctioning one of the most innovative and bold university programs of the current government. Today, we’re creating a new model for the academic institutions, which will have, as its mission, the integration of Latin America through shared knowledge and solidary cooperation. (Trindade 2010)

The match between opportunities, motivation, and abilities in politics led political scientists to leave the scientific field. Distancing themselves from scientific institutions in different levels and paces, Schwartzman and Lamounier reached the limit of heteronomy and broke permanently with the scientific space. On the other hand, if we consider Brazilian scientific geopolitics, Trindade started from a more peripheral point, namely, from the southern state of Rio Grande Do Sul. As his counterparts, he moved closer to the deliberative instances of the MEC. However, because of his positon, his reconversion was completed at a slower pace. It was made viable only when the PT – the main rival of the PSDB’s – won the presidential elections in 2002.

Having occupied a party and ideological position opposed to that of his homologues corresponded to the antagonism between the southeast axis (RJ-MG-SP), wealthier and more dynamic; and the southern region (RS). The national party opposition overdetermined the opposition among political scientists – as it can also be observed in other Latin American countries (Garcé, Carpiuc 2015). The incorporation of the principle of segmentation of the political-party field in the motivations of the dominating agents of disciplinary practice is evident.

The first professional Brazilian political scientists gave a missionary-like meaning to the practices, combining the “Soviet hearts” of their youth with compliance with the “American minds” of their mature years (see Chart 2 and Chart 3, below).

Santos and Reis are two cases in which the heteronomy was minimal. While their homologues were absorbed in party life, they only worked for the state, refraining from party ties. Upon his return from the USA, Santos had the ideal assets to fulfill Cândido Mendes’ expectations. The ambition of the latter consisted in reviving and updating the ISEB, restoring the nationalist tradition of essayistic prose, to which he wanted to add modern methodologies and an American repertoire. Santos was the ideal man likely to occupy this perfect vacant position. He combined American-style mathematization with the Brazilian essayistic tradition. The combination of these two elements, namely Brazilian erudite tradition and American innovation, resulted in his intellectual triumphs. In this way, he put into practice his different skills and gathered a symbolic capital useful in different areas. The central position he achieved cannot be disconnected from this strategy.

Santos’ participation in the 1973 “Seminar on Brazilian Problems” promoted by the IPEAC (Research and Consultancy Studies Institute of the Congress) illustrated the transit between those two delimitations (scientific and politic; state and parties) and tended to be less dependent on the political field. He gave a lecture called “Strategies for Political Decompression.” This happened one year before President Ernesto Geisel announced the project of the re-democratization of the country. The talk was directed at members of the ARENA and MDB, addressing “scientifically a practical objective: suggestions of possible political behaviors able to face the new phase of the authoritarianism that Brazil was about to enter” (Santos Reference Santos1978, 11). He affirmed that the political decompression likely to establish a regime including permanently dissent and divergence, required a collective pact concerning its rules. For this reason, it was necessary not only to “avoid authoritarian distortions … (but also) to create voluntary politics to implement and maintain a non-authoritarian order.”Footnote 13 In the audience, there were members of the two parties already existing during the military dictatorship: José Sarney (ARENA), Clóvis Stenzel (ARENA), Marcos Freire (MDB), Lisâneas Maciel (MDB), Franco Montoro (MDB), Amaral de Souza (ARENA). Their reactions incarnate the dissonance between the lecturer’s intentions and the ones of the political elites. Some people in the audience paid compliments to his cold and scientific-oriented approach. Others insisted that although Santos stated he did not want to teach lessons, this was exactly what he was doing. Finally, some people claimed that, by affirming that the return to democracy had to be the result of calculations, instead of a spontaneous movement, Santos was justifying the authoritarian regime. Santos’ ambition was to do “political science,” while the congressmen were targeting topics convenient to their partiesFootnote 14 . The convergence and divergence among those who had scientific dispositions (Santos) and those who were committed to politics (congressmen) could not have been more perfect.Footnote 15

During the mid-1970s, Reis gave consulting services to the FF and to state organs. But while Trindade and Schwartzman worked in public education policies, Reis worked in instances of scientific regulation and assessment. In 1974, the CAPES was responsible for the “National Post-Graduation Plan” and, in 1977, for assessing this system. Reis was the President of the Consultants’ Commission for Political Sciences and Law. In 1980, he became a member of the National Post-Graduation Board to assess preliminary drafts of the courses. The major services he rendered were meeting the demands and formulating policies for organizations that regulated and evaluated the scientific space (see Chart 3, Political Pole). The positions he took were inseparable from the objective positions he held in these organisms. Without subordinating himself to party militancy, Reis did not separate politics from scientific practice. On the contrary, he affirmed that it was necessary to have a minimal normative project to distinguish “ideal situations” from “impediments” to democracy. The overall conditions (economic and social) of political development had always been his major research concern. For him, in order to establish democracy, it was necessary to have a specific “elector,” an elector ideologically consistent and inexistent in Brazil. This is something that persisted from the Marxism of his youth (in which in the ideal situation, the post-revolutionary society would operate as a measure to analyze the present).Footnote 16 Politically speaking, PSBD activists considered him “pro-PT,” and PT militants considered him “pro-PSDB.” It could not be otherwise in a discipline that tended to heteronomy and was overdetermined by the principle of segmentation proper to national party politics.

Dispositions, positions, taking positions

Political Science (only makes sense) if (there’s a) practical concern;” “thinking about the causes of political authoritarianism’s … in connection with the idea of political development (ties with a) normative content … there would be no politics in a society of slaves … yes, it is a utopian and normative dimension … (I need to) imagine a better condition and a worse one (to characterize) the process (that goes from one to the other). (Reis 201, 312)

Chart 3. (below) takes into account only the first generation of professional political scientist and shows practices that extrapolated instances of scientific knowledge production. Political services, in a broad sense – were categorized as: (3rd column) activism in the press (characterized, from the point of view of this article, as non-neutral communication with large audiences, but geared to intervening in electors’ decision-making conditions); (4th column) diversified consulting services. This diversity is interesting: some individuals became experts in services focused primarily on the state apparatus – a) enlightening political parties and congressmen, producing analysis (Reis, Cintra); others, in instances that regulated the education system (Schwartzman); or evaluating the production of their peers, in organizations that financed, evaluated and ranked research institutions (Santos). However, becoming a member of the two most structured political parties of the country (PT and PSDB – stressing the fact that the latter was founded by Cardoso, in 1988, after the Constitution was granted) seals the incorporation of the princples of appreciation and modalities of intellectual performances deliberately heteronomous. The scientific position taking of those who started to participate in these parties was driven by the segmentation of the political party space.

By opposing the different cases, considering only the first professional Brazilian political scientists, it is possible to affirm that their final reconversions were determined by three factors: 1) a structure of opportunities (concentrated in the southwest, and reduced in the South); 2) the accumulation of capitals in institutional circulation (along the RJ-MG-SP axis); 3) the ties with Cardoso. Given that Trindade was deprived of these three factors, his reconversion was postponed, but did take place. Santos and Reis, on the other hand, who had renounced the party militancy present in their homologues, became figurations of the possible autonomy of the field.

Conclusion. From prophets of the revolution to priests of democracy

The analytical perspective of this article combined prosopography with a transnational study of the evolution of disciplines (Heilbron Reference Heilbron2014, 2008; Gingras Reference Gingras2002). The approach adopted tried to avoid the partiality of the apparently mutually exclusive internalist and externalist analysis of the scientific world (Merton Reference Merton1973; Bloor Reference Bloor1991) and to emphasize the complex combination between these two analysis (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu2001; Camic, Gross, and Lamont Reference Camic, Gross and Lamont2011).

The Brazilian literature shows that the sagacity of the negotiations with the FF’s philanthropy resulted in the establishment of successful research institutes and professional associations; nonetheless, this literature ignores the selective principles of the intellectual imports. In order to highlight this selective dimension, this article has delved deeply into an analysis of the first generation of professionalized political scientists, shedding light on their processes of conversion and reconversion. To accomplish this, it tried to avoid the distressing embarrassment related to the national taboos crystallized in the existent scholarship (above all: the relationship of material and symbolic subordination to the USA; the rise of the middle classes to elites; the ideological metamorphoses). Without analyzing these aspects, the assessment of the content of the imports sounds mechanical, because the exchanges did not only depend on financing and travels. Transferring models from one national intellectual field to another never happens in an empty space without density nor history.

As Christophe Charle affirms, this is “a tortuous process, characterized by multiple contradictions due to its inscription in a field of internal and external intellectual struggles” (Charle Reference Charle, Charle, Schriewer and Wagner2004, 199). The inertia of traditions, practices, and places add a filter to the set of new techniques favoring certain innovations and blocking others (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu2002; Heilbron 2008). In any case, the agents of the transfers possessed previous dispositions, which are crucial if one wants to understand the transfers themselves. The young revolutionaries had to convert their militant intentions into scientific ones, their “political” disturbances into research problems and, finally, had to replace their theoretical repertoire (usually based on Marxism) with references taken from contemporary authors coming from the discipline of political science. As in other national experiences, the institutionalization of political science in Brazil took place during the Cold War and during the military dictatorship (Ravecca Reference Ravecca2016). This panorama determined the preferred themes of the first investigations proper to the field. The margins that delimited the imagination and practices of Brazilian political scientists were, on the one hand, related to asking what “were the existing … alternatives to convert the (authoritarian) regime through conventional political means, that is, negotiations, agreements and partial and successive solution of conflicts?” (Santos Reference Santos1978, 7). On the other hand, they had to establish a direct dialogue with the military regime, that would allow them to penetrate the press, state, and parties. It is this effort that enabled them to become the “intellectual mentors” during the creation of political science as a discipline.

During the first stage of the process, upon their return to Brazil, the political scientists, were attracted by the elections, just as the ruling groups and the military regime (in 1974, 1976). Once they had been readapted to the working conditions of the national field, the process of elaboration of the Constitutional Charter (from 1986-1988) ended up converging all of them. Simultaneously, they entered the sphere of the political elite, at the service of state organs and of the political parties. In this way, the political dispositions of the “little geniuses” were reactivated. They were no longer prophets of the revolution, because scientific life had converted them to the priesthood of democracy. Since they were already practicing it as professional political scientists, they rendered the services demanded from the press, the state, and the political parties.Footnote 17 Once their path of social ageing reached its end, they felt delighted, firm in the meaning and legitimacy of their changes.

At what pace and to what extent did the following generations of political scientists remain connected to the thematic agenda, principles of political and intellectual appreciation, and models of conduct crystallized by the first generation of professional Brazilian political scientists? Would they be more autonomous, namely less dependent from the state, the political parties and the press? Or did they reproduce the standards of exchange among those three spaces as constitutive of their professional identity? Certainly, these questions deserve deeper investigations, if we bear in mind the complicated question of “scientific autonomy.” By reconstructing the trajectory of a fraction of a particular generation I addressed problems that go beyond the scope of this article, and that should be inscribed in a more detailed analysis of the history of the Brazilian intellectual field. It has been through the ramifications of the state apparatus directed at education management and research that political scientists were gradually absorbed into the field of power. Once they had the opportunity of constructing and defending the institutional conditions that would secure the possibility of their scientific practices, they did not hesitate in becoming the artisans of the scientific space. However, as a result of the inertia, this path led them to militate inside a party and to abandon scientific life. This is the reason why, in Brazil, it was difficult to establish a regime of symbolic and scientific production ruled by autonomous principles, both structural and structuring. Situating this case in a broader time scale, it is possible to see that the phases of Brazilian history in which the pace of urbanization, industrialization, and modernization accelerated were also marked by the State co-optation of intellectuals. During the Vargas dictatorship (1930-1945) it was the literati, and during the military dictatorship (1964-1988), the social scientists (Miceli 2001, 2018; Loureiro Reference Loureiro1997). A phrase by Antonio Candido reflects this situation: all Brazilian intellectuals are “more or less mandarins when they deal with institutions, especially state-owned ones; and inoperative if they don’t do so” (Candido 2001).

Acknowledgments

This research was partially funded by Fapesp (the state of São Paulo Research Foundation) and this article is a revised version of a paper first submitted to Research Committee 33 (The Study of Political Science as a Discipline) in the International Political Science Association (IPSA) World Congress (2016). Thanks to Thibaud Boncourt, Paulo Ravecca, Giuseppe Bianco, Paula Ladeira Prates, Stéphane Dufoix, and Sean Purdy for their reading and precious comments on this paper.

Appendices

The charts are based on published interviews and institutional commemorative issues (Cardoso Reference Cardoso2012, Lamounier Reference Lamounier2013, Santos Reference Santos2011, Schwartzman Reference Schwartzman2010, Avritzer Reference Avritzer2016); “w.i” : “without information”.

Chart 1. Social division of the work to build the discipline (1966-1978).

Chart 2. Acronyms. AP (Popular Action); FACE/UFMG (Economy and Administration Sciences College of the Federal University of Minas Gerais); FLACSO (Latin-American Social Sciences College); JUC (Catholic University Youth); MRT (Tiradentes Revolutionary Movement); PCB (Brazilian Communist Party); POLOP (Marxist Revolutionary Organization. Labor Politics); PUC-RS (Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul); UFRJ (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro); UN (United Nations).

Chart 3. (*) Schwartzman also worked in economics faculties (EBAP-FGV: Brazilian School of Public Administration of the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, in RJ and in SP, between 1970-1990). Acronyms: CNPq (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development); CAPES (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development); CDES (Economic and Social Development Council of the Presidency of the Republic); CACS-CNPq (CNPq Social Sciences Committee); CD-CNPq (CNPq Deliberative Council); IDESP (Economic, Social and Political Sudies Institute of São Paulo); FJP (João Pinheiro Foundation/MG State); IETS (Work and Society Studies Institute/Prived); FF (Ford Foundation); FINEP (Studies and Projects Financing/Brazilian State); FUNCEP/ENAP (Public Officials’ Foundation Center/National School of Public Administration –MG State); GERES/MEC (Executive Group for the reformulation of High-education/Ministry of Education and Culture); SEMOR (Secretary for Administrative Modernization and Reform/Brazilian State); SEPLAN (Secretary For Planning/Brazilian State); SESU/MEC (MEC Secretary for Higher-Education); PUC-SP (Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo); UnB (University of Brasilia).

Lidiane Soares Rodrigues is Professor at the Federal University of São Carlos, Brazil. Doctor in History, she researches the historical sociology of the Social Sciences, in particular, the international circulation of symbolic goods and the reception of Karl Marx in Brazil.