1. Introduction: The model

Over the last decade there has been a shift of perspective in L2 acquisition, along with a parallel shift in linguistic theory. Research has moved from questions related to parameter resetting and U(niversal) G(rammar) accessibility to how syntactic knowledge interacts with other components of grammar and cognitive (sub)systems in the interlanguage of L2 learners. A number of studies have shown that linguistic phenomena at the interfaces are particularly vulnerable in a wide range of acquisitional contexts, such as L2 acquisition, L1 attrition and child bilingualism; see Sorace & Serratrice (Reference Sorace and Serratrice2009) and White (Reference White, Ritchie and Bhatia2009) for overviews, as well as Section 3 below. An area lending itself to this type of approach is word order in L2 grammars.

In this paper, we analyse the production of Verb–Subject order (VS henceforth) in two corpora of L1 Spanish–L2 English and in a comparable native English corpus. English word order is said to be “fixed”, constrained by properties at the lexicon–syntax interface, which determine the syntactic position of verbal arguments. By contrast, Spanish “free” word order is ruled by properties at the syntax–discourse interface (i.e., topic and focus).

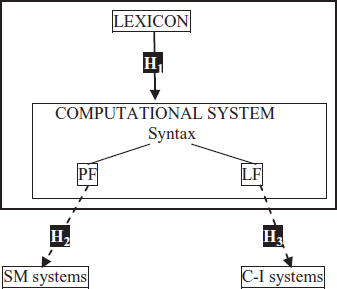

The Minimalist Program (Chomsky, Reference Chomsky1995, Reference Chomsky, Martin, Michaels and Uriagereka2000, Reference Chomsky2005) with its emphasis on interface conditions is the general framework for our study. The language faculty has an “internal” interface, connecting the lexicon (which specifies the elements entering into computation) and the syntax or computational system (which generates derivations). Derivations are pairs of interface representations, understood as “instructions” for the “external” systems with which the language faculty interacts: articulatory–perceptual (i.e., sensory–motor (S–M)) and conceptual–intentional (C–I) (Chomsky, Reference Chomsky1995, p. 169). Interaction with these systems takes place through the interface levels: Phonological Form (PF) and Logical Form (LF), respectively (see Figure 1 below; see Section 4 for the three hypotheses considered in this paper). A linguistic expression is then “nothing other than a formal object that satisfies the interface conditions in the optimal way” (Chomsky, Reference Chomsky1995, p. 171). Recent research has focused on the properties which (external) interface conditions impose on the language faculty: e.g. data analysis for language acquisition and computational efficiency (e.g. Chomsky, Reference Chomsky2005; Epstein, Reference Epstein, Epstein and Hornstein1999; Frampton & Gutmann, Reference Frampton and Gutmann1999). SLA research is now beginning to address questions related to the interaction between syntactic knowledge and knowledge from “external” components in L2 grammars.

Figure 1. The architecture of language and our three hypotheses.

Two main results have been obtained in this study: (i) the parallel use of VS structures in both L1 and L2 English (regarding verb class and the nature of the postverbal subject), indicating that VS appears to be constrained by the same conditions in native and non-native English, and (ii) Spanish learners of L2 English overuse the construction and produce mostly deviant structures. Transfer and, to a lesser extent, the role of input are explored as possible explanations. We also explore other factors, which are at the centre of debate in SLA interface studies: processing limitations (and their interaction with crosslinguistic influence) and the relative difficulty of acquiring lexicon–syntax and syntax–discourse properties.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows: in Section 2 we describe VS in the native grammars of English and Spanish. A brief review of previous research findings on VS in L2 grammars is provided in Section 3. Our hypotheses are presented in Section 4, followed by a description of the method (Section 5), our results (Section 6), a discussion (Section 7) and concluding remarks (Section 8).

2. Verb–Subject order at the interfaces

Despite having “fixed” word order, English allows subject inversion in certain contexts outside interrogatives. There are two main types: (i) “full inversion” (Verb–Subject), illustrated in (1), and (ii) “partial inversion” (subject–operator; e.g. Only then did I realize what he meant). Though both are triggered by an element other than the subject in clause-initial position, their properties are quite different (Biber et al., Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999, Section 11.2.3). Our concern here is full inversion, which is found in English in certain, highly restricted, syntactic contexts, as in (1) – an example of “locative” inversion (bold is used to mark the postverbal subject).Footnote 1

(1) Somewhere between Shigeru Shibata and Silvio Berlusconi lies the ideal husband: demonstrative but sincere, flamboyant but faithful.

(Jemima Lewis, “Why British men make good husbands”, The Independent, 3 February 2007, p. 14)

XP–V–S structures like (1) are much more commonly found in written registers than in spoken registers and constitute the main inversion type in fiction (see Biber et al., Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999, Section 11.2.3.8 for details). Typically, these structures have the following properties: (i) the initial XP contains familiar or given information (topic) – in (1), Shigeru Shibata, a member of the Japan Doting Husbands Association, has been mentioned in the preceding paragraph and Silvio Berlusconi is regarded as a well-known individual; (ii) the verb (lie) is intransitive, expressing existence, and (iii) the postverbal subject is a complex NP, with premodifiers and postmodifiers, which introduces the notion of the ideal husband as new information.Footnote 2

In Spanish, in contrast, subjects “freely” invert with all verb classes: transitives like comprar “buy” in (2a) and both intransitive types – unergatives like hablar “speak” (2b) and unaccusatives like llegar “arrive” in (2c) – with or without preverbal elements and requiring no special intonation.

(2)

An analysis of VS structures in the native grammars of English and Spanish must take into account: (i) the lexico-semantic properties of the verb and their interaction with structural properties (lexicon–syntax interface, Section 2.1 below); (ii) the discourse status of the postverbal subject (syntax–discourse interface, Section 2.2); and, additionally, (iii) phonological heaviness or weight, a property responsible for non-canonical word order at the syntax–phonology interface (Section 2.3).

2.1 Postverbal subjects at the lexicon–syntax interface

Postverbal subjects and the Null Subject Parameter

“Free inversion” is among the cluster of properties that characterises languages positively marked for the Null Subject Parameter (e.g. Spanish) (see, inter alia, Fernández-Soriano, Reference Fernández Soriano1993; Jaeggli & Safir, Reference Jaeggli and Safir1989; Rizzi, Reference Rizzi1982). Though there are counterexamples both ways (e.g. Cole, Reference Cole2000), there is a correlation between rich agreement and null subjects (see Rizzi, Reference Rizzi1982). Spanish rich agreement allows for the recovery of the ‘content’ of a null pronominal (pro) subject, illustrated in (3). English, a non-Null Subject language, has “poor” agreement and lacks pro, illustrated in (4).Footnote 3

(3)

(4)

The element pro in (3) is to be distinguished from expletive pro (pro expl) in the surface subject position (<Spec, IP>) of VS structures like those in (2), as represented in (5a) for (2c) above (Llegaron tres niñas “Three girls arrived”). This is the null counterpart of overt expletives like English there, (5b), which seems to have lost its original locative meaning and functions as a semantically empty grammatical subject like expletive it.Footnote 4 Expletives like those in (5) are commonly assumed to be involved in the licensing of a postverbal subject, with which they share agreement and Case features.Footnote 5

(5)

But there has a much more restricted distribution than proexpl: there is compatible with arrive in (5b), but not with buy (transitive) or speak (intransitive: unergative) in (6).Footnote 6

- (6)

a. *There has bought a book Mary.

b. *There spoke John.

Postverbal subjects and the Unaccusative Hypothesis

Since Perlmutter's (Reference Perlmutter1978) Unaccusative Hypothesis, it is commonly accepted in generative grammar that there are two classes of intransitive verbs, which differ in the position occupied by their only argument at the initial level or D-Structure: unergative verbs, in (7a), have an external argument, represented in <Spec, VP> (after Koopman & Sportiche, Reference Koopman and Sportiche1991), but lack an internal argument; unaccusative verbs, in (7b), have an internal argument, but no external argument.

(7)

Semantically, unergative verbs typically denote activities controlled by an agent (e.g. speak in (7a) and also cry, cough, run, etc.), while unaccusatives are associated with themes (e.g. arrive in (7b) and also appear, exist, come, etc.). Under the assumption that semantic relations are syntactically represented in a systematic way (Baker's Reference Baker1988 Uniformity of Theta-Assignment Hypothesis), agents are mapped as external arguments, and themes as internal arguments. NP-movement applies to promote the NPs to <Spec, IP> at S-Structure (see arrow lines in (7)) in order to satisfy their Case requirements and/or the requirement that <Spec, IP> must be filled by an overt element (roughly, Chomsky's EPP, see footnote 5).

The internal argument of an unaccusative verb may, however, remain in its base position, e.g. in there-constructions, as in (5b) above. Both there-insertion and NP-movement satisfy the requirement that English must have overt subjects in <Spec, IP>. Unergatives like speak in (7a) are, on the other hand, commonly assumed to be banned from there-constructions (but see Culicover & Levine, Reference Culicover and Levine2001). Additionally, not all unaccusative verbs may appear in there-constructions. Perlmutter's (Reference Perlmutter1978) intuition that unaccusativity is syntactically encoded but semantically determined has been the starting point for a number of recent studies on unaccusativity (and related phenomena) seeking to establish a relation between the semantics of verbs and the syntactic properties of the constructions they enter. These studies have revealed that the class of unaccusatives is neither semantically nor syntactically homogeneous, and two major (sub)classes have been distinguished: (i) change of state and (ii) existence and appearance (Levin & Rappapport-Hovav, Reference Levin and Rappaport-Hovav1995). In English, only the latter, shown in (8a–c), appear in there-constructions, but not the former, as is shown by (8d–f).

- (8)

a. There appeared a grotesque figure.

(= A grotesque figure appeared.)

b. There exists a unique theory.

(= A unique theory exists.)

c. There arrived three girls.

(= Three girls arrived.)

d. *There opened the door.

(= The door opened.)

e. *There broke a window.

(= A window broke.)

f. *There melted the butter.

(= The butter melted.)

The class of verbs in there-constructions overlaps with the class in XP–V–S constructions like (1) above and also those in (9). These structures show non-canonical PP–V–NP and are descriptively analysed as a variant of equivalent canonical sentences. (9a), an example of locative inversion like (1), seems to be the result of the NP and the PP ‘switching positions’, when compared to (10) (canonical NP–V–PP). In (10), NP–movement applies, as is shown in (11a), while inversion in (9a) results from a movement rule placing the PP preverbally, as is shown in (11b).Footnote 7

- (9)

a. On one long wall hung a row of Van Goghs.

b. Then came the turning point of the match.

c. With incorporation, and the increased size of the normal establishment came changes which revolutionized office administration.

(corpus examples from Biber et al., Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999, pp. 912–913, highlighting is ours)

(10) [NP A row of Van Goghs] [VP hung [PP on one long wall]].

(11)

In Spanish, however, inversion is possible with all verb classes, as shown in (2) above, so there are no constraints at the lexicon–syntax interface. Rather, Spanish (and Romance) “free” inversion appears to be governed by features operating at the syntax–discourse interface, which also operate in English.Footnote 8 This could, in principle, lead to the expectation that Spanish learners of L2 English may produce postverbal subjects with all verb classes, but several studies show that they produce VS with exactly the same subset of verbs as native speakers (see Section 3 below).

2.2 Postverbal subjects at the syntax–discourse interface

Information structure plays a crucial role in the position of subjects in “free” word order languages like Spanish. In preverbal position, subjects (and other elements) are interpreted as discourse topics, i.e., presupposed, given or (relatively) familiar information, while postverbal subjects are interpreted as (presentational/information) focus,Footnote 9 i.e., non-presupposed, new or (relatively) unfamiliar information (e.g. Belletti, Reference Belletti, Hulk and Pollock2001, Reference Belletti and Rizzi2004; Domínguez, Reference Domínguez2004; Fernández-Soriano, Reference Fernández Soriano1993; Liceras, Soloaga & Carballo, Reference Liceras, Soloaga and Carballo1994; Lozano, Reference Lozano2006a; Vallduví, Reference Vallduví1993; Zubizarreta, Reference Zubizarreta1998). In question–answer sequences like (12), the focused subject appears in postverbal position, where it is interpreted as presentation/information focus, (12Bi), while a preverbal subject is pragmatically odd, (12Bii).Footnote 10

(12)

Unlike in focus contexts like (12), verb type does seem to play a role in “out-of-the-blue” contexts, i.e., with neutral questions such as ¿Qué pasó? “What happened”: unergatives pattern like transitives, with postverbal subjects as pragmatically odd, shown in (13Bi), while inversion with unaccusatives is preferred even if the whole clause is new, not just the subject, as in (13B'i), as well as in focused contexts in (12B).

(13)

Thus, inversion in Spanish, as in other Romance languages (e.g. Italian), serves the purpose of focalising the subject (Zubizarreta's Reference Zubizarreta1998 “nuclear stress”): a postverbal subject is interpreted as presentational/information focus in transitive/unergative structures but it is ambiguous in unaccusative structures between a focus and a neutral interpretation (see also footnote 9 on contrastive focus).

As for English, postverbal subjects in there-constructions like those in (8a–c) above and in inversion structures like those in (9) and (1) above are often characterised as functionally equivalent (but see Birner & Ward, Reference Birner and Ward1993), with the postverbal subjects as focus. The tendency for elements with higher informational content to appear towards the end of the clause is descriptively known as the Principle of End-Focus (Quirk et al., Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985, Section 18.3). Thus, locative inversion constructions like (9a) are commonly analysed as involving presentational focus (e.g. Bolinger, Reference Bolinger1977; Bresnan, Reference Bresnan1994; Rochemont, Reference Rochemont1986): the referent of the postverbal NP is introduced, or reintroduced, on the scene referred to by the preverbal PP.

The terms “focus” and “topic” are used here as common labels for new and given (old) information, respectively (Belletti, Reference Belletti and Rizzi2004, p. 42, note 1). Prince (Reference Prince and Cole1981, Reference Prince, Thompson and Mann1992) distinguishes between hearer status (Hearer-old. vs. Hearer-new) and discourse status (Discourse-old vs. Discourse-new). Only the latter distinction is relevant for subjecthood. There is also a third status for an entity in discourse: inferrable, defined by Prince (Reference Prince, Thompson and Mann1992, p. 312) as NPs evoking entities that have not been mentioned, and which the reader has no prior knowledge of, but whose existence can be inferred “on the basis of some entity that was previously evoked and some belief I have about such entities”. Thus, in (14a), the door is Discourse-old. In contrast, the door in (14b) has a double status: (i) as Hearer-old (and Discourse-old), in that it relies on the earlier presence of another entity (e.g. the Bastille) triggering the inference, and (ii) as Hearer-new (and Discourse-new) in that the hearer is not expected to already have in his/her head a mental representation of the entity concerned.

- (14)

a. He passed by the door of the Bastille and the door was painted purple.

b. He passed by the Bastille and the door was painted purple.

We consider topic and focus as concepts encompassing a variety of notions best analysed in terms of a gradience (see Kaltenböck, Reference Kaltenböck2005). We consider both evoked and inferrable entities as topics, on the basis of Prince's (Reference Prince, Thompson and Mann1992) study and Birner's (Reference Birner1994, Reference Birner1995) findings that both entities are treated alike (as Discourse-old) in inversion structures. The term focus refers to “irretrievable” information, whether brand-new or new-anchored (linked in some way to the previous context), together with what Prince (Reference Prince, Thompson and Mann1992) refers to as unused (Discourse-new, Hearer-old entities).Footnote 11

Since inversion is used as a focalisation device in English and Spanish, we expect the inverted subjects produced by our learners to be Discourse-new/focus or relatively less familiar than the preverbal XP (Birner, Reference Birner1994). Importantly, Spanish makes use of this device with all verb types, while English inversion is restricted to unaccusative verbs of existence and appearance, as discussed above.

2.3 Postverbal subjects at the syntax–phonology (PF) interface and processing components

Choice of ordering seems to be also influenced by notions related to the phonetic realisation of the strings generated by the grammar, which operate in the interface with the articulatory–perceptual (i.e. sensory–motor (S–M)) systems. At Phonological Form (PF), there can be operations affecting linear ordering which are not triggered by syntactic features and do not affect meaning, for example, “heavy NP shift” in (15b), contrasted here with (15a) with canonical V–NP–PP.Footnote 12

- (15)

a. I bought [NP a book written by a specialist in environmental issues] for my sister.

b. I bought for my sister [NPa book written by a specialist in environmental issues].

Heavy NP shift is but one manifestation of a general tendency observed in many languages for constituents to occur in order of increasing size or complexity (Wasow, Reference Wasow1997). This is descriptively known as the Principle of End-Weight (Quirk et al., Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985, Section 18.9).

There is considerable debate regarding (i) the correct characterisation of “heaviness”, and (ii) the reasons for end-weight. Concerning (i), two characterisations are often found in the literature: structural/grammatical complexity and string length (number of words). The two concepts are difficult to separate but when they are studied separately studies reveal high correlations between them (e.g. Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Wasow, Losongco and Ginstrom2000; Wasow, Reference Wasow1997). As for (ii), explanations of the End-Weight Principle take either the listener's perspective – putting long and complex elements towards the end of the clause facilitates parsing, as it reduces the processing burden (e.g. Hawkins, Reference Hawkins1994) – or the speaker's perspective – weight effects exist mostly to facilitate planning and production (Wasow, Reference Wasow1997, Reference Wasow2002, chapter 2, Section 5). What is important for our purposes is that processing constraints in the performance systems, like the End-Weight Principle, influence syntax, leading to non-canonical word order structures.

Since constituents expressing new information tend to occur postverbally and heavy/complex grammatical elements tend to appear towards the end of the clause, the End-Weight Principle and the End-Focus Principle appear to reinforce each other (see Biber et al., Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999, Section 11.13; Birner & Ward, Reference Birner and Ward1998). Thus, postverbal subjects are usually focus and tend to be heavy, as in the corpus examples from Levin and Rappaport Hovav (Reference Levin and Rappaport-Hovav1995) in (16) (highlighting is ours).Footnote 13

- (16)

a. And when it is over, off will go Clay, smugly smirking all the way to the box office, the only person better off for all the fuss.

[R. Kogan, “Andrew Dice Clay Isn't Worth ‘SNL’ Flap”, p. 4]

b. Above it flew a flock of butterflies, the soft blues and the spring azures complemented by the gold and black of the tiger swallowtails.

[M. L'Engle, A Swiftly Tilting Planet, p. 197]

(Levin & Rappaport Hovav, Reference Levin and Rappaport-Hovav1995, pp. 221, 257)

Little attention has been paid to the effects of end-weight in Spanish (with the exception of Bolinger, Reference Bolinger1954, and Taboada, Reference Taboada1995). While the relatively “free” word order of Spanish means that weight effects may be less noticeable, (17a) shows that canonical word order with the adjunct PP (en el parque “in the park”) following the NP object (a los chicos. . .historias “the boys I would have liked to tell you stories about”) appears to be less “natural” than (17b), where the heavy object is in sentence-final position following the adjunct.

- (17)

a. #Vi [NPa los chicos de los que quería haberte contado varias historias] [PP en el parque].

“I saw [NP the boys I would have liked to tell you stories about] [PP in the park].”

b. Vi [PP en el parque] [NPa los chicos de los quería haberte contado varias historias].

“I saw [PP in the park] [NP the boys I would have liked to tell you stories about].”

Given that weight effects serve general processing and planning mechanisms, and that (end) weight appears to be a universal phenomenon, a characteristic of the human parser (see Hawkins, Reference Hawkins1994), we will assume that weight is the linguistic manifestation of extralinguistic properties which interact in language design (e.g. principles of structural architecture for computational efficiency; see Chomsky, Reference Chomsky2005). For SVO languages, the effects of weight involve placing long and complex elements towards the end of the clause.

The conclusion is that postverbal subjects which are focus, long and complex tend to occur postverbally in those structures which allow them. This is also the prediction for the learners in our study. The gradience approach adopted for information status is also adopted for “heaviness”: the heavier an NP is, the more likely it is to be placed in clause-final position.

3. Previous L2 findings

Previous research has focused mostly on the VS production in L2 English by L1 speakers of Null Subject languages (e.g. Oshita, Reference Oshita2004; Rutherford, Reference Rutherford1989; White, Reference White and Cook1986; Zobl, Reference Zobl1989). The focus of these studies is on parameter-resetting, transfer, UG accessibility and the psychological reality of theoretical hypotheses. Recently, the focus has shifted to how syntactic knowledge interacts with knowledge from other components (e.g. discourse) in the interpretation and use of null subjects and VS structures (see White, Reference White, Ritchie and Bhatia2009, and references cited therein).

While White's (Reference White and Cook1986) study shows that L1 Spanish – L2 English speakers rejected VS in acceptability tasks (mostly due to verb choice, as pointed out by Oshita Reference Oshita2004, p. 107), two production studies (Rutherford, Reference Rutherford1989; Zobl, Reference Zobl1989) support the hypothesis that L1 speakers of Null Subject languages produce postverbal subjects in L2 English with unaccusative verbs only, (18).

(18)

However, the two studies differ in their explanation of why VS is found with unaccusatives. For Zobl (Reference Zobl1989), the reason is developmental: VS precedes a stage when learners are able to determine the canonical alignment between semantic roles and syntactic structure. For Rutherford (Reference Rutherford1989), VS production is the result of transfer, but no explanation is offered as to why (XP)–V–S order in the learners’ grammar is restricted to unaccusatives. The problem with these studies is that their conclusions are based on a relatively small number of learners and VS instances; in addition, not enough information is provided about learners’ sample, proficiency level and so on.

Oshita (Reference Oshita2004) was the first study to use a relatively large electronic corpus, Longman Learners’ Corpus (version 1.1). He extracted 941 token sentences (concordances) with 10 common unaccusative verbs and 640 token sentences with 10 common unergative verbs from L2 English compositions written by L1 speakers of Italian, Spanish, Japanese and Korean. Since his objective was to investigate the psychological reality of null expletives, he extracted VS sentences with preverbal overt expletives (i.e., it, there) and null expletives. His results corroborate the role of unaccusativity for L1 Spanish and Italian learners, whose production ratios are similar (14/238 (6%) Spanish; 14/346 (4%) Italian), but his conclusions are also based on a relatively small number of tokens. Some examples from L1 Spanish learners are given in (19):Footnote 14

- (19)

a. . . .it will happen something exciting . . .

b. . . .because in our century have appeared the car and the plane. . .

(both L1 Spanish; Oshita, Reference Oshita2004, pp. 119–120)

Previous studies show a remarkably consistent pattern in which unaccusative and unergative verbs are treated differently by L2 learners of English regarding VS. This adds to other types of (morpho)syntactic evidence which point towards what is referred to in the literature as the “psychological reality” of the Unaccusative Hypothesis in SLA (e.g. Balcom, Reference Balcom1997; de Miguel, Reference de Miguel and Liceras1993; Hertel, Reference Hertel2003; Hirakawa, Reference Hirakawa and Kanno1999; Ju, Reference Ju2000; Lozano, Reference Lozano2003, Reference Lozano2006a, Reference Lozano, Torrens and Escobarb; Montrul, Reference Montrul1999, Reference Montrul2004; Oshita, Reference Oshita2000; Sorace, Reference Sorace1993; Yuan, Reference Yuan1999).Footnote 15 This difference is found despite the fact that English lacks overt marking for unaccusatives, rendering the unergative–unaccusative distinction inaccessible, and that unaccusatives overwhelmingly appear in SV constructions. In other words, although inversion is found with unaccusatives in English (see Section 2 above), the rarity of the construction (Biber et al., Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999, p. 945) makes it unlikely that VS is sufficiently represented in the input to count as positive evidence for learners.

As it has become clear in the previous discussion, choice of VS is determined by interface conditions. Additionally, conceptualising interfaces involves mastering the processing mechanisms for integrating information from different domains in the non-native grammar. These are issues that have barely begun to be explored in SLA research. Regarding postverbal subjects, research has focused on VS in the L2 grammars of languages like Italian and Spanish by speakers of languages with fixed word order (e.g. English) (see, among others, Belletti & Leonini, Reference Belletti, Leonini, Foster-Cohen, Sharwood Smith, Sorace and Mitsuhiko2004; Hertel, Reference Hertel2003; Lozano, Reference Lozano2006a; Belletti, Bennati & Sorace, Reference Belletti, Bennati and Sorace2007). The results of these studies show consistently that learners experience problems with linguistic phenomena at the syntax–discourse interface. There are disagreements, however, concerning the nature of these problems: are they grammar external (processing deficits) or internal (representational deficits)? As for the source, at least four explanations have been given: feature underspecification, crosslinguistic influence, processing limitations and quantity/quality of input (see Sorace & Serratrice, Reference Sorace and Serratrice2009, for a review).

Two aspects distinguish our study from previous studies: (i) for us unaccusativity is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for VS production: a full account of VS in L2 (and L1) grammars must necessarily look at the properties of both the verb (lexicon–syntax interface) and the subject (syntax–discourse and syntax–phonology interfaces); (ii) while previous studies focus mostly on ‘errors’, we focus on the interface conditions for VS production in both L1 and L2 English.

In Lozano & Mendikoetxea (Reference Lozano, Mendikoetxea, Gilquin, Papp and Díez2008) we lay the basis for the current study and set out to investigate the interface conditions under which postverbal subjects were produced in L2 English by analysing VS/SV structures in the Italian and Spanish subcorpora of the International Corpus of Learner English (ICLE; Granger, Dagneaux & Meunier, Reference Granger, Dagneaux and Meunier2002) (1,510 usable concordances). Postverbal subjects were produced with unaccusative verbs like disappear, as predicted, and were shown to be heavy as well as new information (focus), as in (20), as opposed to preverbal subjects with the same verbs.

(20)

In the current study, we compare our results on VS production by L1 Spanish learners of English with those obtained from a comparable English native corpus in order to throw some light on issues to do with, among others, transfer, processing constraints and the role of input. Given the focus of the present study, our results are also relevant for the current debate in SLA regarding the nature of deficits at the interfaces. Within the framework of the so-called “interface hypothesis”, Sorace (Reference Sorace2004, Reference Sorace, Cornips and Corrigan2005) has argued that advanced learners are more likely to show deficits at the “external” interfaces (syntax–discourse) than at the “internal” interfaces (lexicon–syntax) (but see Ivanov, Reference Ivanov2009, on native-like behaviour at the interfaces with L2 Bulgarian clitics). Our results, however, show that learners display native-like behaviour regarding interface conditions (lexicon–syntax, syntax–discourse and syntax–phonology), but overuse the VS construction and show persistent problems in its syntactic encoding.

4. Hypotheses

As a general hypothesis, we expect no substantial differences between intermediate/advanced L1 Spanish learners of L2 English and English native speakers regarding the interface conditions for VS structures production. We saw that in both English and Spanish, postverbal subjects represent new information, while preverbal subjects are given information (the Principle of End-Focus) and that postverbal subjects are typically heavier than preverbal subjects (the Principle of End-Weight).

However, while VS is restricted to a subset of unaccusative contexts in English, no such restrictions apply in Spanish. This difference could lead us to predict that our learners may invert more freely than English native speakers (as a result of transfer), but previous L2 research consistently shows that the Unaccusative Hypothesis is a guiding principle in building learners’ mental grammars (irrespective of their L1–L2 pairings). Thus, based on previous research findings (reported in Section 3 above) and theoretical studies (summarised in Section 2 above), we formulated three hypotheses, presented in (21)–(23).

(21) H1: Lexicon–Syntax interface – Unaccusativity and the postverbal subject

As in native English, postverbal subjects will be produced with unaccusative verbs only (never with unergatives) by Spanish learners of L2 English.

(22) H2: Syntax–Discourse interface – Information status of the postverbal subject

As in native English, learners will place unaccusative subjects in postverbal position when they are focus (i.e., Discourse-new and/or Hearer-new), yet in preverbal position when they are topic (i.e., Discourse-old and/or Hearer-old, inferable, containing inferable).

(23) H3: Syntax–Phonology (PF) interface – Weight of the postverbal subject

As in native English, learners’ unaccusative postverbal subjects will (typically) be heavier than their preverbal counterparts.

In Chomsky's Minimalist Program, theory-internal levels such as D-Structure and S-Structure are eliminated so the language faculty minimally contains an “internal” interface (lexicon–syntax) and two “external” interfaces, connecting the language faculty with external systems: PF and LF (see Section 1 above, based on Chomsky, Reference Chomsky1995, chapter 4). Figure 1, representing the minimalist reinterpretation of the classic generativist Y-model, shows where our three hypotheses are located within that model.

5. Method

5.1 Instrument: Corpora and concordancer

We used two learner corpora of Spanish learners of L2 English (Table 1): (i) the Spanish subcorpus of ICLE (International Corpus of Learner English, Granger et al., Reference Granger, Dagneaux and Meunier2002), with a total of 200,376 words of essays written by L1 Spanish learners of L2 English at two Spanish universities, Universidad Complutense de Madrid and Universidad de Alcalá de Henares; and (ii) WriCLE (Written Corpus of Learner English, version 1.0), which is being developed at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, following the ICLE guidelines: it contains essays written by upper-intermediate Spanish learners of L2 English (63,836 words). The two corpora were treated as one for the purposes of the study.Footnote 16

Table 1. Corpora details.

The learner corpora were contrasted against a comparable corpus of native English: LOCNESS (Louvain Corpus of Native English Essays), consisting of argumentative essays written by British and American students at pre-university and university level (288,177 words).Footnote 17

5.2 Data coding and analysis

To investigate H1 (lexicon–syntax interface), we chose 73 lemmas, or word types, (31 unaccusative and 41 unergative verb types) from the inventory of intransitives (Table 2) proposed by Levin (Reference Levin1993), and Levin and Rappaport-Hovav (Reference Levin and Rappaport-Hovav1995). For each lemma, we searched for all possible L1 and L2 forms (misspellings and overregularisations, e.g. appeard, arised, etc.), using the concordancer WordSmith Tools version 4.0 (Scott, Reference Scott2004).

Table 2. Inventory of unaccusatives (based on Levin, Reference Levin1993; Levin & Rappaport-Hovav, Reference Levin and Rappaport-Hovav1995).

*see also sound emission **see also substance emission ***see also existence

Concordances (VS and SV sentences containing those verbs) were retrieved automatically and then filtered manually according to 51 filtering criteria (due to space limitations, we present only the key filters, in (24), so as to discard structural contexts in which inversion in English is not possible, as we are interested in contexts where the choice of SV/VS is not restricted by structural factors). Only a quarter of the concordances output by the concordancer were usable: n = 58 in the learner corpora and n = 16 in the native corpus.

(24) Filtering criteria

a. The verb must be intransitive (either unaccusative or unergative from, Table 3).Footnote 18

b. The verb must be finite.

c. The verb must be in the active voice.Footnote 19

d. The subject must be an NP.Footnote 20

e. The sentence must be declarative.

f. Set expressions are excluded.Footnote 21

Table 3. A syntactic scale for measuring syntactic weight.

Notes: (i) The asterisk (*) marks a complex (i.e., recursive) lexical or phrasal structure.

(ii) Parentheses indicate the optional realisation of a given lexical category or a given phrase.

Preverbal and postverbal subjects were coded manually for weight and discursive status. While VS concordances were all coded due to their small number (n = 58 + 16), we selected a random sample of all SV concordances with unaccusative verbs (n = 762 for learners and n = 703 for native speakers) from the only four inverted unaccusatives (come, exist, begin and remain) in the native corpus (n = 91 unaccusative SV concordances) and the top four inversion unaccusatives (exist, appear, begin and come, as Figure 6 shows) in the learner corpora (n = 96 unaccusative SV concordances).

As for H2 (syntax–discourse interface), for each concordance we coded the discursive status of the (preverbal/postverbal) subject. The entire composition was inspected to determine the nature of each subject as topic or focus, where these terms encompass a variety of notions (see Section 2.2).

Regarding the analysis used for H3 (syntax–phonology interface), there is no agreement in the literature as to the most appropriate measuring instrument for syntactic weight, as seen in Section 2.3. While word length, as measured by number of words, is standardly used (e.g. Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Wasow, Losongco and Ginstrom2000; Kaltenböck, Reference Kaltenböck2005), it cannot tell us how long (or short) a constituent must be to be considered “heavy” (or “light”). Thus, while the histogram in Figure 2 shows that the most frequent lengths for the subject constituent in the learner corpora were 2 and 5 words, and the mean of all lengths was 7.5 words, it is difficult to establish the cut-off point between heavy vs. light.

Figure 2. Frequency of word-length of postverbal (VS) subjects (learner corpora).

To solve this dilemma, we started off with a syntactic scale of complexity in order to arrive at a reliable nominal dichotomous scale (heavy/light), as shown in Table 3. The nominal scale was then correlated with a numeric scale (number of words). The rationale was that, if the nominal scale is a good predictor of weight, then it should correlate significantly with the numeric scale.

Therefore, bare N(ouns) that optionally take a D(eterminer), as in (25a), were regarded as light and ranked as 0 in an ordinal scale, which ranges from 0 (syntactically simple) to 3 (syntactically complex). This is a more fine-grained scale than the nominal scale, as it mediates between the syntactic-complexity scale and the nominal scale. Its usefulness can be seen with reference to (25b): NPs with an optional D, as in (D)+ADJ+N, are slightly more complex than (D)+N and thus can be ranked as 1, though they are still light. Heavy structures can be syntactically less elaborate (ranked as 2), such as (25c), with D+N+PP, or more complex (ranked as 3), such as (25d), with a full NP+Finite-clause.

- (25)

a. However, with the awareness also came discrimination. [usarg.txt]

b. . . . that it can exist a better world. . .[spm04006]

c. With this theory also came the area of quantum mechanics. [usarg.txt]

d. . . . for there exists a general judicial presumption that Parliament does not intend to legislate contrary to European Community Law. [brsur3.txt]

With this procedure, we obtained three weight measures for each postverbal subject: number of words, degree of syntactic complexity and degree of weight. Highly significant correlations were found in the learner corpora between (i) word length and complexity (ρ = .73, n = 58, p < .001 with Spearman's rho test), (ii) length and weight (nominal scale) (ρ = .61, n = 58, p < .001) and (iii) complexity and weight (ρ = .83, n = 58, p < .001). Similar significant correlations were also found in the native LOCNESS corpus, which indicates that our nominal scale (heavy/light) is a reliable indicator of weight. Hence we decided to adopt this nominal scale together with the widely-used numeric (word-length) scale.

6. Results

6.1 Results for H1: Unaccusativity (lexicon–syntax interface)

The difference between preverbal vs. postverbal subject production is highly remarkable (Figure 3). While the proportion of postverbal subjects with unaccusatives was 7.1% for learners (i.e., 58 out of a total of 820 concordances), there were no instances of postverbal subjects with unergatives (0/181 ratio, i.e., 0%). This SV/VS difference is statistically significant (χ2 = 12.65, df = 1, p < .001; since the observed frequency in one of the cells is smaller than 5, Fisher's exact test, rather than the standard Pearson's test, was performed). The difference is also remarkable for native speakers (2.2% for unaccusatives and 0% for unergatives). Similarly, preverbal subjects are the norm in both corpora (97.8% for native speakers and 92.9% for learners). However, learners (7.1%) produce postverbal subjects with unaccusatives significantly more often than native speakers do (2.2%) (χ2 = 19.67, df = 1, p < .001 with Pearson's test).

Figure 3. Preverbal subjects (SV) and postverbal subjects (VS) produced with intransitives.

Regarding the type of VS structures (Figure 4), the most frequent structure produced by learners is it-insertion, illustrated in (26a, b), which accounts for 41.4% of all VS structures and is ungrammatical in native English.Footnote 22 This is followed by grammatical locative inversion (15.5%), in (27a, b); XP-insertion (13.8%), in (28a, b), which are ungrammatical in the learner data due to the absence of expletive there; grammatical there-insertion (10.3%), in (29a, b); AdvP-insertion (10.3%), in (30a, b), which can be classed as a type of loco/temporal inversion and is a possible grammatical structure in native English; and, finally, ungrammatical Ø-insertion (8.6%), in (31a, b). Native speakers, on the other hand, produce the following VS structures: XP-insertion (43.8%), as in (28c, d), there-insertion (37.5%), in (29c, d), and AdvP-insertion (18.8%), in (30c) (the only example produced). Surprisingly, no instances of locative inversion are found, which can be taken simply as a gap or perhaps a bias in the native corpus, since locative inversion is a relatively common VS structure in written English (see Biber et al., Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999, Section 11.2.3). As expected, native speakers did not produce any instances of ungrammatical it-insertion and Ø-insertion.

(26)

(27)

(28)

(29)

(30)

(31)

Figure 4. Frequency of the types of postverbal-subject structures produced.

Figure 5 represents the learners’ proportion of structures according to their grammaticality: two thirds (65.5%) of the VS structures produced by our learners are ungrammatical (i.e., structurally impossible in native English).Footnote 23 In short, learners produce mostly ungrammatical it-insertion (a construction that is neither in their L2 input nor directly a result of L1 transfer) and grammatical locative inversion. Native speakers produce mostly XP-insertion and there-insertion. We will come back to these results in the following section.

Figure 5. Postverbal-subjects structures according to their grammaticality.

Let us focus now on the unaccusative verb itself. Figure 6 shows the percentage that each particular unaccusative verb contributes to the grand VS total (7.1% for learners and 2.2% for native speakers, as shown in Figure 3 above). For learners, the top inversion verbs are exist (2.9%), appear (1.7%), begin (0.6%), come (0.5%) and arise/emerge/occur (0.2% each). Native speakers inverted with only four unaccusatives: come (1.3%), exist (0.7%) and begin/remain (0.1% each). In Section 7 we discuss the production of exist in the learner vs. the native corpora.

Figure 6. Production of postverbal subjects (VS) according to verb: VS/Total Concordances ratio.

6.2 Results for H2: Information status (syntax–discourse interface)

As Figure 7 shows, postverbal subjects are always focus or new information (100% for native speakers and 98.3% for learners).Footnote 24 By contrast, preverbal subjects tend to be topic or evoked information (83.5% for native speakers and 89.6% for learners). This implies that both native speakers and learners place subjects postverbally if and only if the subject represents new information, yet preverbally when it typically represents old information. The topic vs. focus difference is significantly different for each word order in each corpus (p < .001 for all comparisons). Also note that both native speakers and learners behave alike, as there are no significant differences between them in terms of preverbal subjects (χ2 = 1.485, df = 1, p = .223) and postverbal subjects (χ2 = 0.280, df = 1, p = .597). This is illustrated in (32) and (33), where we provide the context preceding the target concordance to see the focus status of the postverbal subject since (i) it has not been mentioned in the prior discourse, (ii) it is not known to the reader, and (iii) it cannot be inferred by the reader.

(32) Native speakers: postverbal focus subject

. . . Albert Einstien came onto the scene. Although his theory (his and his wife's) was basically scientific in nature, it can and has been applied to all areas of human existence. The theory I'm speaking of is relativity. With this theory also came the area of quantum mechanics. [usarg.txt]

(33) Learners: postverbal focus subject

Figure 7. Information status of preverbal (SV) and postverbal (VS) subjects with unaccusatives.

Principally, in the midle ages all the cities were filled with churches, monasteries, convents, priests and nuns. Hence, religion was part of the population. . . . God was the most important, the center their own existence. So arised the Saint Inquisition in case someone blasphemed about God. [spm05012]

By contrast, in (34) and (35) the information status of the preverbal subject is known (topic), as it has been previously mentioned in the discourse (shown by underlining).Footnote 25

(34) Native speakers: preverbal topic subjects

. . . In order to examine why Louis took such exception to Hugo it is necessary to reflect on the way in which the Party regarded intellectuals. Hugo came from a bourgeoisie background, . . . [brsur1.txt]

(35) Learners: preverbal topic subjects

The feminism is the movement that try to obtain that women have the same rights than men, . . . The feminism begun with the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution, . . . [spm07020]

Additionally, the preverbal XP in XP–V–S structures such as (28a) above shows a strong tendency to represent known/old information (topic) in both corpora: 80% (16/20) for learners and 100% (8/8) for native speakers (p = .237 with Fishers’ exact test).Footnote 26

To summarise, discourse clearly constrains both native speakers’ and learners’ distribution of the subject in SV/VS structures: postverbal subjects are focus (with the preverbal material as topic), while preverbal subjects are topic.

6.3 Results for H3: Weight (syntax–phonology interface)

The weight rates (Figure 8) are similar in both corpora: postverbal subjects are more frequently heavy (81% for learners and 81.3% for native speakers) than light (19% and 18.8%, respectively). Thus, learners’ behaviour does not significantly differ from native speaker’ (χ2 = 0.000, df = 1, p = .647 with Fisher's exact test). By contrast, preverbal subjects are more frequently light (67.7% for learners and 68.1% for native speakers) than heavy (32.3% and 31.9%, respectively). Once again, learners’ rates do not differ from native speakers’ (χ2 = 0.004, df = 1, p = .951 with Pearson's test).

Figure 8. Weight of preverbal (SV) and postverbal (VS) subjects with unaccusatives (nominal scale).

On the nominal scale, then, learners and native speakers behave alike in placing heavy subjects postverbally, as illustrated in (36) (though a small portion of them can be light, as in (37)), but light subjects preverbally, as in (38) (though some can be heavy, as is shown in (39)).

(36) Learners and native speakers: postverbal heavy subjects

a. . . . in 1880, it begun the experiments whose result was the appearance of television some years later. [learner, spm03051]

b. Thus began the campaign to educate the public on how one contracts aids. [native speaker, usarg.txt]

(37) Learners and native speakers: postverbal light subjects

a. . . . and from there began a fire, . . . [learner, spm04011]

b. Along with the traffic congestion, comes pollution. [native speaker, alevels1.txt]

(38) Learners and native speakers: preverbal light subjects

a. . . . but they may appear everywhere. [learner, 0002.cor]

b. These debates began over two decades ago. [native speaker, usarg.txt]

(39) Learners and native speakers: preverbal heavy subjects

a. However, I strongly believe the cases of men mistreated do not appear in the media because . . . [learner, 0006.cor]

b. However, my curiosities about sexual relationships still existed. [native speaker, usarg.txt]

Consider now these production rates when measured numerically (word length). The boxplot in Figure 9 shows the dispersion of word-length of the subject. For SV in both native and learner corpora, the median (represented by the vertical bar inside the box) is 2 words long (i.e., half of the preverbal subjects produced are two words long or less, while the other half are two words long or more) and the word-length mean (indicated by the cross) is 3.14 words (native speakers) and 3.24 (learners), the difference being non-significant (t = 0.252, df = 185, p = .801, with an independent-samples t test). As for VS, in the native corpus, the median is 11 words and the word-length mean is 11.06, while in the learner corpus the median is 6 words and the mean is 7.52, the difference being statistically significant (t = –2.229, df = 72, p = .029). Additionally, preverbal subjects are significantly shorter than postverbal subjects in both corpora (t = 8.221, df = 105, p < .001 for native speakers; t = 6.715, df = 152, p < .001 for learners), as Figure 9 shows.

Figure 9. Weight of preverbal (SV) and postverbal (VS) subjects with unaccusatives (numeric scale).

In short, both native speakers and learners produce significantly longer subjects in postverbal position than in preverbal position, though the native speakers’ postverbal subjects are significantly longer than the learners’. This finding confirms our previous results on the nominal (heavy/light) scale.

7. Discussion

The main result of our study is the parallel use of VS structures in native English and L2 English (L1 Spanish): postverbal subjects are produced with essentially the same (sub)class of verbs and under the same interface conditions (i.e., when the subject is focus and/or heavy). Yet, learners produce a high proportion of ungrammatical structures, due mostly to the wrong choice of preverbal element.

The fact that VS occurs only with (a class of) unaccusatives but never with unergatives, confirms our hypothesis H1 (lexicon–syntax interface) and is in line with previous L2 research on VS structures, as well as with studies showing that L2 learners are sensitive to the (morpho)syntactic and semantic manifestations of unaccusativity (see Section 3). Additionally, within the context of L2 research on the interfaces, our results could be taken as confirmation that the internal interface (lexicon–syntax) is not problematic for advanced learners (see e.g. Sorace & Serratice, Reference Sorace and Serratrice2009; Tsimpli & Sorace, Reference Tsimpli and Sorace2006; White, Reference White, Ritchie and Bhatia2009).

Regarding the two classes of unaccusatives (see Section 2.1), our results confirm the possibility of VS structures with verbs of existence and appearance in L1 Spanish–L2 English (see also Lozano & Mendikoetxea, Reference Lozano, Mendikoetxea, Gilquin, Papp and Díez2008, for L1 Italian–L2 English), but further research is needed to show that unaccusative verbs of change of state do not trigger inversion, as in L1 English.

It still needs to be explained why our learners do not produce VS structures with unergatives, which are possible in their L1 Spanish (see also Oshita, Reference Oshita2004, Section VI). Since inversion structures, though rare, are found in English with a subclass of unaccusative verbs and never with unergatives (but see footnote 13), learners’ beahaviour may be attributed to input. Given the rarity of the construction, however, we have to resort to the Unaccusative Hypothesis: learners are aware of the unergative/unaccusative distinction and use it to build mental grammars in the process of L2 acquisition, as previous research has shown (see Section 3 above, and footnote 15). Thus, while input (and, certainly, instruction) are crucial for the development of interlanguage grammars, our results cannot be accounted for by input, or at least by input alone. The fact that native speakers’ top inversion unaccusatives (as shown in Figure 6 above and also as reported by Birner, Reference Birner1995) do not coincide with learners’ (and the same applies to low inversion unaccusatives) could be taken as some evidence for this (though it may also be a bias in the sample).

Both learners and native speakers display a very strong and clear-cut pattern in terms of information status, by producing subjects (i) in postverbal position only if they represent focus (new) information, yet (ii) in preverbal position only if they represent known (topic) information. Additionally, the preverbal material in XP–V–S structures is topic, “anchoring” the structure to the preceding discourse (see Birner, Reference Birner1995, on anchoring). The syntactic distribution of VS/SV is thus regulated discursively, which supports H2 (syntax–discourse interface).

The results on weight clearly reveal that learners behaved like native speakers by producing (i) VS when the subject is heavy, yet (ii) SV when the subject is light, which confirms hypothesis H3 (syntax–phonology interface). To our knowledge, this is the first L2 (corpus-based) study that shows that L2 English learners appear to be observing the Principle of End-Weight (see Section 2.3, above) irrespective of the (un)grammaticality of the structures produced.

Much theoretical research from a functional perspective points out that end-weight and end-focus are related (Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Wasow, Losongco and Ginstrom2000; Hawkins, Reference Hawkins1994; Wasow, Reference Wasow1997, Reference Wasow2002; and Section 2.3 above). When speakers need a significant number of words to develop a new idea (i.e., a heavy subject), the constituent they form tends to be in a position typically reserved for new information (i.e., postverbally, in sentence-final position), whereas short subjects appear in a position typically reserved for old or familiar information (i.e., preverbally, in sentence-initial position).

The End-Focus and End-Weight Principles stem from a general mechanism that facilitates language processing, which lessens the processing load on the listener/reader (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins1994) and/or on the speaker/writer (Wasow, Reference Wasow1997) by leaving longer and heavier (and, very often, new) elements to be processed at the end. It then seems that learners of L2 English are overriding grammatical criteria in favour of more general (perhaps universal) processing criteria in their production of subjects with unaccusatives.

While the correlation between discourse status and weight (as summarised in Table 4) is by no means perfect in all cases, it is certainly the case that (i) all postverbal subjects are focus yet all preverbal subjects are topic, and (ii) most postverbal subjects are heavy (81%) yet most preverbal subjects are light (68%). It then seems that if a subject is heavy (long), it tends to be placed in the same position as new-information constituents, namely, postverbally. The fact that native speakers produce longer subjects than learners has to do with the correlation between complexity and proficiency: as is well known, phrasal composition increases in complexity with developmental level (Klein & Perdue, Reference Klein and Perdue1992), with length of production as one of the measures for quantifying complexity or linguistic maturity (see Ortega, Reference Ortega2000, Reference Ortega2003).Footnote 27

Table 4. Tendency of syntactic distribution with unaccusative subjects: weight × information status.

Regarding the combination of the three interfaces, previous L2 research (Oshita, Reference Oshita2004; Rutherford, Reference Rutherford1989; Zobl, Reference Zobl1989) has shown that learners produce VS structures with unaccusatives only, but these studies have failed to notice that unaccusativity is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the production of postverbal subjects: VS in both native and non-native English is constrained by properties operating at three interfaces, illustrated in (40).

(40) Conditions for postverbal-subject production

a. Lexicon–syntax interface: The verb must be unaccusative (and not unergative).

b. Syntax–phonology (PF) interface: The postverbal subject will tend to be heavy (long).

c. Syntax–discourse interface: The postverbal subject must be focus (new information).

There are two main respects in which learners’ production deviates from native speakers’ use of VS structures. Native speakers’ production of VS structures (2.2%) is significantly lower than learners’ (7.1%). It is important here to look at the verbs triggering inversion. Almost half of learner VS structures (2.9%) contain the verb exist, as opposed to 0.7% native speakers. This clearly inflates the learners’ inversion rates (Figure 6; see also Palacios-Martínez & Martínez-Insua, Reference Palacios-Martínez and Martínez-Insua2006). Since in L1 Spanish, the verb existir “exist” typically requires a postverbal subject, this may, in principle, indicate transfer. But if this was a result of L1 transfer alone, learners would be expected to produce mostly VS with exist, which is contrary to fact, since they produced 46 SV sentences out of 70 concordances. Hence, our learners’ higher overproduction rates must stem from a lexical bias (overuse of exist) rather than from L1 transfer alone.

Native speakers and learners also differ in the types of (XP)–V–S structures they produce, as shown in Section 6.1. Differences concern the relative production rates of the various constructions, as well as the nature of the preverbal element: (i) an “expletive”-type element (there, it or Ø) or (ii) a “lexical” element (locative PP, AdvP or another XP). Regarding (ii), though learners are proficient in their use of preverbal locative PPs, they show difficulties in precisely figuring out what counts as an appropriate XP in other contexts. This is not surprising as it is difficult to describe what can and what cannot appear as a preverbal XP in VS structures in L1 English: grammars simply provide lists of examples with locative and time adverbials, as well as “other types of” adverbials (e.g. Biber et al., Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999, Section 11.2.3.1). For native speakers, frequency and patterns of use may be playing a part in their choice of preverbal XP in a particular context. Even advanced learners, however, have a relatively limited exposure to the language and without clear grammatical rules they are left to make their own choices. This is a matter that needs to be explored in further studies.

More interesting for our purposes is the use of expletive-type constructions: grammatical There–V–S and ungrammatical *It–V–S and *Ø–V–S. In Lozano and Mendikoetxea (Reference Lozano and Mendikoetxea2009a, Reference Lozano and Mendikoetxeab), we compare these three structures in the Spanish, Italian and French subcorpora of ICLE. The most common ungrammatical structure for all three learner groups is *It–V–S: of all (XP)–V–S structures: 41.4% for L1 Spanish, 27% for L1 Italian and 9.1% for L1 French. This is followed by Ø–V–S, produced by L1 Spanish (8.6%) and L1 Italian (7.2%) speakers, but not by L1 French speakers.

Production of Ø–V–S structures is often attributed to crosslinguistic influence (transfer). Equivalent constructions in Spanish and Italian contain a null expletive (see Section 2.1 above). There is evidence that for L1 speakers of Null Subject languages null expletives are harder to expunge from their L2 English than null referential pronouns: learners omit expletives in sentences like In winter, snows a lot in Canada (L1 Spanish, White, Reference White and Cook1986; see also Hannay & Martínez Caro, Reference Hannay, Martínez Caro, Gilquin, Papp and Díez2008) and non-use of overt expletives persists longer than non-use of overt referential pronouns (Phinney, Reference Phinney, Roeper and Williams1987; Tsimpli & Roussou, Reference Tsimpli and Roussou1991). That is, even at advanced levels, learners may still produce sentences like those in (31) above, as an instance of what Sorace (Reference Sorace, Cornips and Corrigan2005) calls “residual” optionality, but not sentences with a missing referential pronoun, equivalent to I, you, he, etc. The transfer account would also explain why Ø–V–S is not produced by L1 French learners of L2 English.

Production of *It–V–S shows that learners are aware that the subject position must be filled in English, but despite positive evidence (e.g. there-insertion), it is the preferred expletive. Presentational there-constructions, like those in (29) above (with verbs other than be), are rarely used by L2 learners of English who are L1speakers of Null Subject languages (and L2 learners of English who are L1 speakers of topic-drop languages), as noted by Oshita, Reference Oshita2004. By contrast, a corpus study by Palacios-Martínez and Martínez-Insúa (Reference Palacios-Martínez and Martínez-Insua2006) shows that L1 Spanish learners of L2 English overuse existential there-constructions (there+be). It may well be that underuse of presentational there and overuse of existential there could be related and input could be part of the explanation. Existential there-constructions are introduced at an early stage in the learning process, and (one suspects) are high-frequency structures in the input. They are learned as formulaic or prefabricated chunks with the verb be (Palacios Martínez & Martínez-Insúa, Reference Palacios-Martínez and Martínez-Insua2006). Thus, there may not be used as an independent expletive until advanced levels of proficiency (Oshita, Reference Oshita2004, note 21). Learners’ (lack of) exposure to presentational there constructions may also be a factor. This is, of course, highly speculative, both empirically and theoretically: once we focus on different types of VS structures, we are dealing with a relatively small number of tokens, and the role of input in SLA is not well understood. Further research, possibly experimental, needs to be carried out to see whether learners actually favour some VS structures and are reluctant to accept/use others.

It is clear from the preceding discussion that our results cannot be accounted for by input alone, nor can they be accounted for by L1 transfer alone either. Firstly, if there was transfer, we would expect VS production with both unaccusatives and unergatives, since inversion structures can be also found in native Spanish with unergatives, e.g. En el parque jugaban niños “In the park played children” (Ortega-Santos, Reference Ortega-Santos2005; Torrego, Reference Torrego1989; but see Mendikoetxea, Reference Mendikoetxea, Copy and Gournay2006, for a different analysis of these constructions). Secondly, our learners’ postverbal subject rates are relatively low (7.1%), as they mainly produced grammatical SV (92.9%). Experimental work shows that Spanish native speakers significantly (and drastically) prefer VS to SV with unaccusatives, yet SV to VS with unergatives (Hertel, Reference Hertel2003; Lozano, Reference Lozano2003, Reference Lozano2006a). Hence, if L1 transfer were taking place, we would expect our learners to show higher VS rates than those shown in Figure 3.Footnote 28

However, there are other ways in which transfer or crosslinguistic influence may be affecting learner production. The fact that our learners produce mostly deviant VS structures may be interpreted in the light of current SLA research, according to which linguistic phenomena at the (external) interfaces are particularly vulnerable in non-native grammars and that failure to acquire a fully native grammar may be largely attributed to problems at integrating different types of knowledge at the interfaces: interfaces are targets for deficits such as fossilisation and optionality, even at end-states (e.g. Sorace, Reference Sorace2004, Reference Sorace, Cornips and Corrigan2005; see Section 3 above). This may be because (i) structures requiring the integration of syntactic knowledge and knowledge from other domains need more processing resources than aspects of grammar requiring only syntactic knowledge, and/or (ii) learners may be less efficient at integrating multiple types of information in on-line comprehension and production of structures at the (syntax–discourse) interface (see Sorace & Serratrice, Reference Sorace and Serratrice2009, and references therein).

Though the precise nature of processing limitations is not well understood, they could in part explain why our learners produce mostly ungrammatical VS structures. As pointed our by Sorace and Serratrice (Reference Sorace and Serratrice2009), there is evidence from bilinguals that complete de-activation of one of the two languages when hearing/speaking the other is rarely possible: they are always simultaneously active and in competition with one another (Dijkstra & van Heuven, Reference Dijkstra and Van Heuven2002; Green, Reference Green1998). However, several factors affect their relative activation levels and the strength of competing structures: task, proficiency in each language and frequency of use, among others. Thus, while not directly the result of transfer, some of the difficulties learners experience in VS production may be the result of difficulties at integrating different types of knowledge due to competition from the L1 VS form: e.g. use of Ø–V–S and It–V–S (see Lozano & Mendikoetxea, Reference Lozano and Mendikoetxea2009a, Reference Lozano and Mendikoetxeab). Our results suggest that these deficits are not external to the grammar, as learners have no difficulties in identifying topic/focus, for instance, but rather they belong to the computational system and/or the failure to map this information into appropriate syntactic structures: learners cannot encode the End-Weight and End-Focus Principles onto the correct grammatical constructions and overuse the construction, possibly due to processing difficulties and crosslinguistic influence. Future research (cross-sectional or longitudinal) is needed to clarify the precise role of interfaces (syntax–discourse and syntax–phonology) in SLA and to determine the source of deficits in those areas where the computational system interacts with external (sub)systems.

8. Conclusion

Previous research has shown that learners of English produce postverbal subjects with a (sub)type of unaccusative verbs, but never with unergatives. In SLA research the Unaccusativity Hypothesis has been invoked to account for this phenomenon. Crucially, our study shows that unaccusativity is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for Verb–Subject order to occur in both L1 and L2 English. A full account of VS must look not only at the nature of the verb, but also at the characteristics of the postverbal subject, a fact that has gone unnoticed in previous studies. Given the appropriate structural conditions (e.g. the presence of an unaccusative verb), there is a strong tendency for VS to be produced when the subject is syntactically heavy, as well as new information or focus. Interestingly, there is an interrelation between these two factors, as both conditions are designed to ease the processing burden and thus they can be considered (external) interface conditions imposed on the language faculty.

Our study does not only have a wider scope than previous studies but also has a different focus: while previous studies have mostly focused on errors, we have seeked to identify the interface conditions under which learners produce VS structures: the verb is unaccusative (lexicon–syntax interface) and the subject is heavy (syntax–phonology interface) and focus (syntax–discourse interface). These interface conditions constrain VS production, regardless of learners’ problems with the syntactic encoding and their overuse of the construction. Our study shows that the production of English native speakers and the production of L1 Spanish learners of L2 English do not differ significantly in the interface conditions that constrain Verb–Subject order, but rather in the (un)grammaticality of the outputs of syntactic encoding.