Introduction

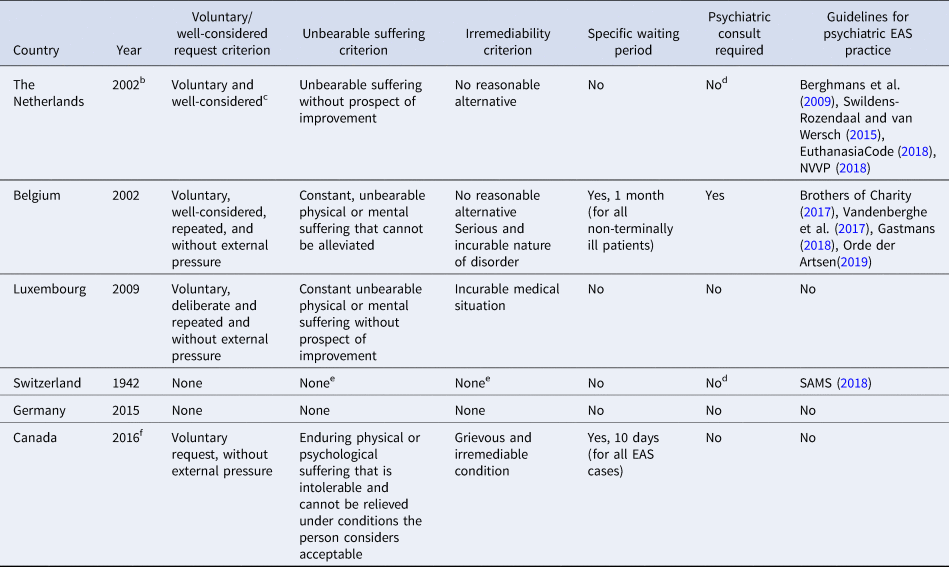

Euthanasia or assisted suicide (EAS) primarily on the basis of psychiatric disorders (psychiatric EAS) is permitted in some European countries such as the Netherlands and Belgium (Table 1). In these countries, the number of cases has been slowly but steadily increasing since 2010 and empirical papers on the topic have rapidly increased since 2015 (De Hert et al., Reference De Hert, Van Bos, Sweers, Wampers, De Lepeleire and Correll2015; Dierickx, Deliens, Cohen, & Chambaere, Reference Dierickx, Deliens, Cohen and Chambaere2017; Doernberg, Peteet, & Kim, Reference Doernberg, Peteet and Kim2016; Kim, De Vries, & Peteet, Reference Kim, De Vries and Peteet2016; Miller & Kim, Reference Miller and Kim2017; Nicolini, Peteet, Donovan, & Kim, Reference Nicolini, Peteet, Donovan and Kim2020; RTE, 2017; Thienpont et al., Reference Thienpont, Verhofstadt, Van Loon, Distelmans, Audenaert and De Deyn2015; van Veen, Weerheim, Mostert, & van Delden, Reference van Veen, Weerheim, Mostert and van Delden2019; Verhofstadt, Thienpont, & Peters, Reference Verhofstadt, Thienpont and Peters2017). In Canada, the 2016 medical assistance in dying law, limited to those whose natural death is ‘reasonably foreseeable’, engendered an ongoing controversy about whether access should be extended to the non-terminally ill (CCA, 2018). A recent Quebec court ruling declared the proximity to death requirement unconstitutional, raising important implications for psychiatric EAS in the country (Rukavina, Reference Rukavina2019).

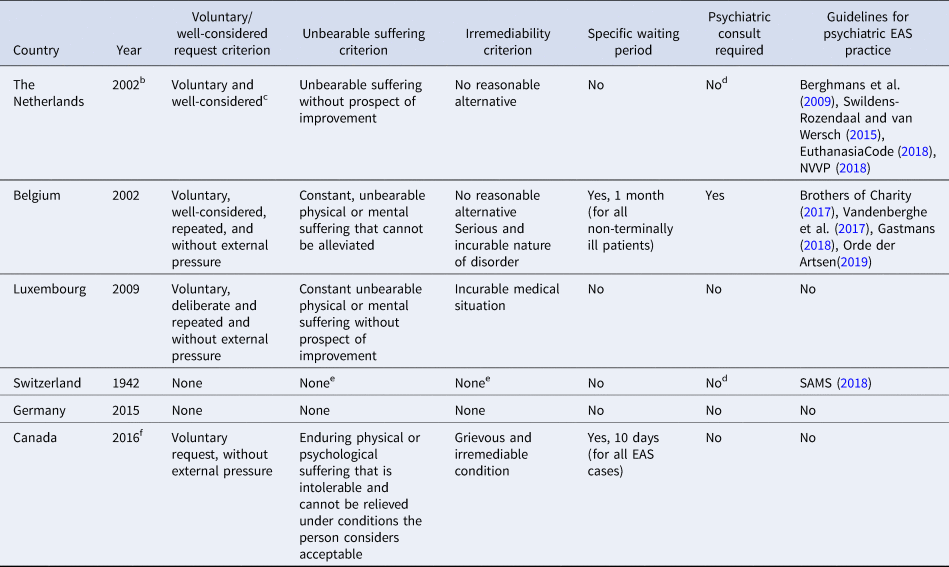

Table 1. Comparison of psychiatric EAS practice across jurisdictionsa

a Refers to psychiatric EAS in persons who are not at end of life (due to other medical conditions). The Benelux countries allow for both euthanasia and assisted suicide. The Belgian Act does not explicitly mention assisted suicide but it is allowed in practice. Switzerland and Germany do not have a specific EAS law but decriminalized-assisted suicide (not euthanasia) under certain conditions, regardless of proximity to death and there have been cases of psychiatric EAS in these countries (Black, Reference Black2012; Bruns, Blumenthal, & Hohendorf, Reference Bruns, Blumenthal and Hohendorf2016; Griffith et al., Reference Griffith, Weyers and Adams2008).

b Psychiatric EAS in particular became effectively legal following the 1994 Chabot court case involving the assisted suicide of a 50-year old woman with complex bereavement who refused treatment (Griffith et al., Reference Griffith, Weyers and Adams2008).

c While the law does not mention it, the Euthanasia Review Committees (EuthanasiaCode, 2018) add in their definition of the requirement that it be ‘without external pressure’.

d A psychiatric consultation is not stated in the law but is required by the Euthanasia Review Committees in the Netherlands (Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Huisman, Legemaate, Nolen, Polak, Scherders and Tholen2009; EuthanasiaCode 2018) and by the Swiss Federal Supreme Court following the 2006 Haas case ruling in Switzerland (Black, Reference Black2012).

e Although the Swiss law does not have an unbearable suffering or irremediability requirement, the guidelines by the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences do (SAMS, 2018).

f The 2016 Medical Assistance in Dying law (MAID) applies to persons whose natural death is ‘reasonably foreseeable’. Hence, it allows for EAS on the sole basis of a psychiatric disorder only if the person is deemed to have a ‘reasonably foreseeable death’ (CCA, 2018). However, a recent Quebec court case ruling that this requirement is unconstitutional and suggests that psychiatric EAS will likely become legal in all of Canada (Rukavina, Reference Rukavina2019).

But even in the European countries where psychiatric EAS has been legal for years, the practice remains controversial (Griffith, Weyers, & Adams, Reference Griffith, Weyers and Adams2008; Jones, Gastmans, & MacKellar, Reference Jones, Gastmans and MacKellar2017; RTE, 2018) and some cases have led to court cases (Cheng, Reference Cheng2019; Day, Reference Day2018). Attitudes among professionals vary: a 2016 Dutch survey indicated that 37% of psychiatrists found it conceivable to provide psychiatric EAS, compared to 47% in 1995 (Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al., Reference Onwuteaka-Philipsen, Legemaate, van Der Heide, van Delden, Evenblij, El Hammoud and Willems2017). Similarly, Belgian mental health professionals have been divided over the issue (Bazan, Reference Bazan2015; Claes et al., Reference Claes, Van Bouwel, An, Marc, Georges, De Lepeleire and Lemmens2015; Haekens, Calmeyn, Lemmens, Pollefeyt, & Bazan, Reference Haekens, Calmeyn, Lemmens, Pollefeyt and Bazan2017). Perhaps as a consequence of this, various guidelines by major healthcare institutions and professional organizations have been written and revised, especially over the last few years to guide and regulate the practice (EuthanasiaCode, 2018; NVVP, 2018; Orde der Artsen, 2019; Vandenberghe et al., Reference Vandenberghe, Titeca, Matthys, Van den Broeck, Detombe, Claes and Van Buggenhout2017; Verhofstadt, Van Assche, Sterckx, Audenaert, & Chambaere, Reference Verhofstadt, Van Assche, Sterckx, Audenaert and Chambaere2019).

Although the landmark Chabot case in the Netherlands occurred over 25 years ago (Griffith et al., Reference Griffith, Weyers and Adams2008), a systematic review of the literature on the ethical reasons for and against the practice is lacking. Systematic reviews of ethics literature are intended to inform bioethics argumentation, but also policy-making (McCullough, Coverdale, & Chervenak, Reference McCullough, Coverdale and Chervenak2007; Sofaer & Strech, Reference Sofaer and Strech2012; Strech & Sofaer, Reference Strech and Sofaer2012). We performed a systematic review of reasons, a specific type of review for bioethical questions which identifies and extracts all published reasons for or against a contested policy or practice. Its purpose is to provide a comprehensive and systematic descriptive overview of the ethical debate rather than a philosophical evaluation of the reasons (McDougall, Reference McDougall2014; Mertz, Strech, & Kahrass, Reference Mertz, Strech and Kahrass2017; Strech & Sofaer, Reference Strech and Sofaer2012). The aims of our review were twofold: First, to identify what reasons have been provided for why psychiatric EAS should or should not be permitted as a practice or by law. Second, to describe and characterize notable trends in the debate and identify current gaps and areas for future research.

Methods

Search strategy

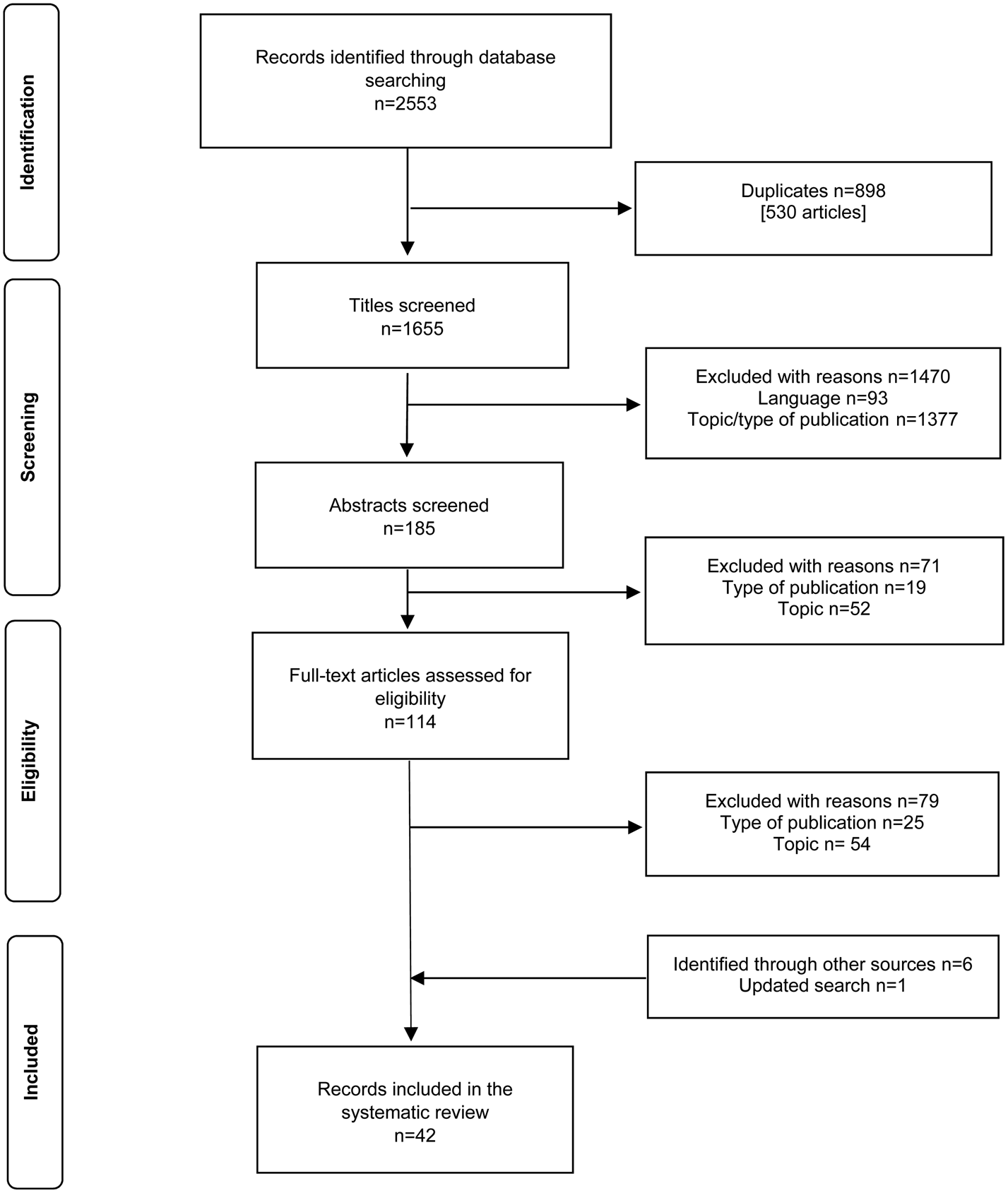

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Liberati et al., Reference Liberati, Altman, Tetzlaff, Mulrow, Gotzsche, Ioannidis and Moher2009; Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009) (Fig. 1). One author (M.N.) searched, from inception until 6 November 2018, the following databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science (Core Collection), PsycInfo, Philosopher's Index, Embase, Scopus, and CINAHL. A search strategy used keywords from three groups: mental illness; euthanasia and assisted suicide; and ethics and philosophy. The full search strategy (Appendix A) was reviewed and validated by an independent librarian from the National Institutes of Health. The search was updated to 12 June 2019. Finally, we used the snowball method and our own experience to add publications that was not detected in the seven databases. EndNote X9 was used to manage and screen citations.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow chart of the selection process.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included a publication if:

(1) It focused on psychiatric EAS defined as EAS in which mental illness is the primary reason for the request.

(2) Its primary aim was to provide ethical reasons why psychiatric EAS should or should not be permitted (as a practice or by law).

(3) The publication was peer-reviewed.

(4) The publication was written in English, Dutch, Italian or French.

Condition (I) excluded papers focusing on EAS in: persons with neurodegenerative diseases (e.g. dementia); terminally ill persons with a psychiatric disorder, where the primary reason for requesting EAS was the physical condition and not the psychiatric disorder and persons without medical conditions (e.g. ‘tired of living’ or ‘completed life’ cases). It also excluded papers about the ethics of suicide rather than assisted death and ‘euthanasia’ of the mentally ill in the context of historic eugenic practices.

Condition (II) excluded empirical studies, purely descriptive clinical or legal – rather than normative – case analyses, and articles mainly providing an overview of the reasons for or against psychiatric EAS rather than defending one's own position. Articles in which the overall position was taken was less clear but where the authors directly responded to others' positions were included because responding to an argument implies taking a position. Finally, we included case discussions only if they contained ethical arguments, principles or recommendations. Condition (III) excluded non-peer reviewed articles, newsletters, guidelines and textbook chapters. We included letters, commentaries and editorials only if they were peer-reviewed. When it was not clear from the journal's website whether a publication was peer-reviewed, we contacted their editorial office.

Study selection and data extraction

Two readers (M.N.; M.C.) independently performed the title/abstract screening following the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full-text screening and data extraction were independently performed by two readers for English articles (M.N.; M.C.) and non-English articles (M.N.; C.G.). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion involving an additional reader (S.K.). We identified and extracted reasons using the following steps. First, we identified the reasons for and against psychiatric EAS. Second, we included a passage as a reason for or against psychiatric EAS if the author proposed the reason directly as an argument for or against, or if the context made it clear that it fell within their overall argument. If the authors discussed an idea but not clearly as a reason for or against, we did not include it. Third, we grouped the reasons into content domains by qualitative content analysis. This was done by multiple readings, highlighting the meaningful units (passages of reasons), labeling them (codes), and grouping them into content domains using a combined deductive and inductive method (Elo & Kyngas, Reference Elo and Kyngas2008; Graneheim & Lundman, Reference Graneheim and Lundman2004; Mertz et al., Reference Mertz, Strech and Kahrass2017).

Results

The systematic search yielded 2553 articles (Fig. 1). Of those, 35 were eligible for inclusion. We identified six additional eligible articles pursuing reference lists and included one article from the updated literature search, for a total of 42 articles.

Publication characteristics

The dates of publication ranged from 1998 to 2019, but 81% (34/42) were published in 2013–2019. Articles were published in the following fields: medicine (52%), bioethics (40%), law (5%) and social work (2%). Based on the corresponding author's credentials, half of the articles were written by authors with a clinical background (e.g. psychiatry, palliative care, geriatrics, social work). Virtually, all clinicians were physicians (95%, 20/21), mostly psychiatrists. The other half were written by authors with a background other than medical (e.g. philosophy, bioethics, law). When an author had both clinical and non-clinical credentials, they were counted as clinicians. Overall, most (71%, 30/42) articles were written by authors in a country where EAS of some type has been legalized (in the country or in some jurisdictions within it). Over half (52%) were from a country where the eligibility for EAS is tied to its proximity to natural death (Appendix B). Of the total, 90% of articles (38/42) were written in English, four were written in Dutch or French.

The articles were nearly evenly distributed with regard to their overall position (48% articles in favor and 52% against). The authors' position was determined by their conclusions and whether the majority of arguments given were in favor or against psychiatric EAS. For example, some authors presented mostly arguments against or in favor of psychiatric EAS, even though they also expressed reasons for the other side – in which case we classified them according to their predominant position (den Hartogh, Reference den Hartogh2015; Steinbock, Reference Steinbock2017; Vandenberghe, Reference Vandenberghe2018; Vink, Reference Vink2012). The position taken varied depending on the corresponding author's background and the article type. Most articles in favor of psychiatric EAS were full-length articles written by non-clinicians (75%, 15/20). Publications against psychiatric EAS tended to be shorter, commentary-type pieces written by clinicians (73%, 16/22).

Reasons for and against psychiatric EAS

We identified 107 reasons (62 pro, 45 con) which were mentioned 407 times (232 pro, 175 con mentions) (Fig. 2). We categorized reasons into eight content domains as shown in Table 2, using the following labels and listed in descending order of frequency: (1) mental and physical (illness and suffering) (2) decisional capacity (3) irremediability (4) goals of medicine and psychiatry (5) consequences for mental health care (6) psychiatric EAS and suicide (7) self-determination and authenticity (8) psychiatric EAS and refusal of life-sustaining treatment (LST) (Table 2). Within each domain, we described the reasons according to the specific topic of disagreement they related to. Of the total, 9% of mentions (36 of 407) directly responded to another paper included in this review; this direct engagement between authors started only in 2013.

Fig. 2. Number of mentions per content domain.

Table 2. Domains, subdomains and their reasons

Mental and physical illness or suffering

Within this domain (65 pro and 32 con mentions), two main areas of discussion emerged: parity (non-discrimination) between mental and physical illness or suffering (59 mentions) and policy concerns (38 mentions). Parity reasons, mostly raised by non-clinicians, stated that if EAS is permitted in persons with terminal, physical illness, differential treatment in persons with mental illness is not justified, based on the parity of mental illness and suffering from physical illness and suffering. Assertions of parity between mental and physical suffering (24 mentions) were the most frequently cited parity reasons in favor of psychiatric EAS, followed by reasons of parity between mental and physical illness (20 mentions). Responses against parity which focused on differences between mental and physical illness, such as the often poorly understood etiology of mental illnesses, were raised by clinicians only. Non-clinicians arguing against parity instead pointed to the fact that there are morally relevant differences that could justify differential treatment in EAS between mental and physical illness. Only one author argued against the parity of mental and physical suffering, that the intolerability of suffering may be a symptom of the disorder.

Policy considerations largely focused on the issue of ‘false positives’ (the ending of lives in persons who in fact do not meet the criteria). Some authors, from different backgrounds, focused on the increased risk of error (i.e. diagnostic or prognostic) in psychiatric disorders and the unfeasibility of implementing rigorous safeguards. Others, mostly non-clinicians in favor of psychiatric EAS, noted that the risk of false positives is not sufficient to justify prohibiting psychiatric EAS or that the risks could be adequately addressed by implementing rigorous safeguards.

Decisional capacity

The domain of decisional capacity figured prominently in the debate (38 pro and 31 con mentions). In the major disagreement (17 pro and 16 con mentions), those arguing for psychiatric EAS, mostly non-clinicians, emphasized that some persons with mental disorders seeking psychiatric EAS are decisionally capable (e.g. arguing that not permitting psychiatric EAS would amount to presuming incompetence). Others argued that the main issue is the difficulty of reliably determining capacity and the need for extra caution. The second point of contention (14 and 11 mentions) regarded evaluations of decisional capacity in psychiatric EAS requests. Authors in favor, largely non-clinicians, stated that capacity evaluations for psychiatric EAS should not be different than any other capacity evaluation in health care. Others, both clinicians and non-clinicians, argued against this and focused on the impact a psychiatric disorder might have on specific abilities for capacity (i.e. on the ability to appreciate how a decision applies to oneself). A third theme (7 pro and 3 con mentions) focused specifically on the threshold for capacity assessment. Some non-clinicians argued it should be independent of the stakes or should be low in order to err on side of self-determination. Other authors argued that the threshold should be high to minimize false positives. Finally, one reason against the practice, with no corresponding reason in favor, related to voluntariness (i.e. that undue external pressure can influence a person's choice).

Irremediability

The irremediability domain (33 pro and 36 con mentions) contained reasons relating to the irremediability of mental disorders. However, authors sometimes used the term to also mean irremediability of mental suffering. The main area of disagreement (12 pro and 27 con mentions) related to whether truly irremediable cases exist in psychiatry and whether they can be reliably identified. The most common reason in favor was the view that mental illness or suffering can be truly irremediable. Responses, raised by authors from different backgrounds, pointed to practical challenges in reliably determining irremediability, such as difficulties in predicting prognosis or the lack of a unified interpretation of ‘treatment-refractory’. Only a few, non-clinicians, responded that we can reliably interpret irremediability, e.g., with the help of statistical tools. In the second dispute (11 pro and 7 con mentions), some authors in favor, mostly non-clinicians, argued that judgments about irremediability should not merely depend on statistical chances of recovery but instead on the person's own judgment. Others responded that determinations of irremediability should be made by both patient and clinician. Within this dispute, reasons in favor partially overlap with (and respond to) some reasons against the practice raised in the domain of decisional capacity, namely that a mental disorder can influence the cognitive aspects of a patient's judgment about their chances of recovery. The third subdomain (6 pro and 2 con mentions) involved the question of whether waiting for possible new treatments, such as ketamine for treatment-resistant depression, is or is not justified.

Goals of medicine and psychiatry

This fourth domain (25 pro and 26 con mentions) contained reasons focusing on the impact of psychiatric EAS on medical and psychiatric practice. The main dispute (13 pro and 14 con mentions) was whether permitting psychiatric EAS would positively or negatively affect the patient–physician relationship. Reasons against were largely raised by clinicians, responded to by authors from different backgrounds. The second dispute (12 pro and 12 con mentions) was whether psychiatric EAS is compatible with the goals of medicine and psychiatry, involving even engagement from authors from different backgrounds. Authors in favor argued that it can be compatible with physicians' role (e.g. consistent with professional integrity and physician's role as gatekeepers of lethal drugs) and duty to relieve suffering. Authors responded that the two are incompatible (e.g. pointing to professional integrity, the social meaning of medicine or the duty to preserve life) and that there is a normative difference between a right to treatment and a right to psychiatric EAS.

Consequences for mental health care

In the fifth domain (17 pro and 20 con mentions), potential consequences of allowing psychiatric EAS for mental health care more broadly were raised. The first point of contention (7 pro and 12 con mentions) was about the effect of psychiatric EAS on mental health care policy. Clinicians argued that it may negatively impact mental health care and that other factors need to be addressed first. Authors from different backgrounds responded that the two are not mutually exclusive. The second disagreement (10 pro and 8 con mentions) concerned the potential consequences for vulnerable populations. All authors arguing that consequences could be negative were clinicians. Authors in favor responded with empirical reasons (e.g. that there is little evidence for this concern) or normative ones (e.g. that expansion of EAS to other populations is not necessarily a bad outcome).

Psychiatric EAS and suicide

This domain focused on the tension between psychiatric EAS and suicide prevention policies (17 pro and 18 con mentions). Within the main disagreement (12 pro and 14 con mentions), authors in favor, mainly non-clinicians, argued that psychiatric EAS can prevent suicides and that denying access to psychiatric EAS forces persons to commit suicide. Others, from mixed backgrounds, pointed to the conflict with the duty to prevent suicide and argued that there is no duty to provide, nor a corresponding right to receive, psychiatric EAS. The second disagreement (5 pro and 4 con mentions), largely argued for by non-clinicians, related to whether patients' eligibility should or should not depend on their physical ability to end their lives.

Self-determination and authenticity

Reasons about self-determination and authenticity (22 pro and 6 con mentions) were, like decisional capacity, closely related to the general concept of autonomy. However, we categorized them separately as they addressed concerns distinct from decisional capacity. Reasons in this domain were raised by authors from different backgrounds. Most reasons related to self-determination (18 pro and 4 con mentions) and whether persons with a psychiatric disorder can have a rational wish to die or make their own free choices. Some responded that respect for autonomy is not sufficient grounds for psychiatric EAS. A second disagreement (4 pro and 2 con mentions) related to authenticity and the impact of psychiatric disorders on the ability to live up to one's goals and values.

Psychiatric EAS and refusal of life-sustaining treatment (LST)

Within this last domain (15 pro and 6 con mentions), the main disagreement related to the relationship between EAS and refusing LST. Some non-clinicians in favor of psychiatric EAS argued that that there is no morally relevant distinction between refusing LST and psychiatric EAS. Authors against psychiatric EAS, from different backgrounds, instead claimed that the justifications for respecting a person's refusal of LST do not provide justifications for psychiatric EAS.

Discussion

Rational and informed policy-making about psychiatric EAS requires a systematic understanding of the reasons for and against the practice. We conducted a systematic review of reasons, a special form of review for bioethical questions, for this purpose. Its secondary aim was to describe and characterize notable trends in the debate and identify current gaps and areas for future research.

Main findings of reasons for and against the practice

Parity arguments figured prominently in the debate, taking the form of ‘If EAS is permitted for X, then it should be permitted for Y since there is no relevant different between X and Y’. This may be because arguments in favor of psychiatric EAS were mostly conditional upon EAS for the terminal, physical illness being legally permitted. This was true for 80% (16/20) of publications in favor of psychiatric EAS, largely (87%) written from countries where some form of legal EAS exists for physical disorders, such as the USA, Canada and Australia. Most authors who argued for parity between mental and physical illness were non-clinicians also arguing for parity between mental and physical suffering (Cholbi, Reference Cholbi2013; Dembo, Schuklenk, & Reggler, Reference Dembo, Schuklenk and Reggler2018; Hirsch, Reference Hirsch2016; Player, Reference Player2018; Provencher-Renaud, Larivée, & Sénéchal, Reference Provencher-Renaud, Larivée and Sénéchal2019; Sagan, Reference Sagan2015; Schuklenk & van de Vathorst, Reference Schuklenk and van de Vathorst2015a; Steinbock, Reference Steinbock2017; Tanner, Reference Tanner2018; Varelius, Reference Varelius2016a). Parity reasons largely relied on the assumption that suffering is the justification for EAS in terminal, physical illness.

Some of these authors also made parity arguments elsewhere, for example by stating that prognostic uncertainty can be present in physical illness as well, and hence does not justify excluding persons with mental illness. Similarly, some reasons in the domains dealing with psychiatric EAS and LST refusal and with decisional capacity were parity-based (e.g. whether capacity assessments for psychiatric EAS should be different than for refusing LST) and conditional upon the right of persons with psychiatric disorders to refuse life-saving or other high-stake interventions.

The policy implications of parity reasons were disputed by both clinicians and non-clinicians. Some authors in favor, mostly non-clinicians, argued that parity requires extending EAS laws to include persons with mental illness as a matter of principle. Hence, the possibility of false positives should be tolerated to reduce overall suffering (Cholbi, Reference Cholbi2013; Provencher-Renaud et al., Reference Provencher-Renaud, Larivée and Sénéchal2019; Reel, Reference Reel2018; Rooney, Schuklenk, & van de Vathorst, Reference Rooney, Schuklenk and van de Vathorst2018; Sagan, Reference Sagan2015; Schuklenk & van de Vathorst, Reference Schuklenk and van de Vathorst2015a; Tanner, Reference Tanner2018). Other authors in favor of the practice instead raised policy concerns (Steinbock, Reference Steinbock2017; Vandenberghe, Reference Vandenberghe2018). These authors raised similar concerns about whether decisional capacity and irremediability can be reliably identified.

Other disagreements were not parity-based. Some depended on empirical assumptions which will need further testing, such as the dispute about prognosis prediction in psychiatry. For example, machine learning methods to predict prognosis at the individual level are being developed (Chekroud et al., Reference Chekroud, Zotti, Shehzad, Gueorguieva, Johnson, Trivedi and Corlett2016; Dinga et al., Reference Dinga, Marquand, Veltman, Beekman, Schoevers, Van Hemert and Schmaal2018) and may further inform the psychiatric EAS debate. Other empirical questions include the effects of psychiatric EAS on mental health care and the patient–physician relationship. Although there is some literature on the potential problem of (counter-)transference in the context of EAS and psychiatric EAS in particular (Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Huisman, Legemaate, Nolen, Polak, Scherders and Tholen2009; Groenewoud et al., Reference Groenewoud, Van Der Heide, Tholen, Schudel, Hengeveld, Onwuteaka-Philipsen and Van Der Wal2004; Hamilton, Edwards, Boehnlein, & Hamilton, Reference Hamilton, Edwards, Boehnlein and Hamilton1998; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Gastmans and MacKellar2017), other effects on the patient–physician relationship are unknown.

Some normative disputes resulted from different underlying premises or philosophical assumptions. For example, whether irremediability should be defined by ‘objective’ clinical judgment based on prevailing evidence or by the requestor's own, ‘subjective’ judgment is not an empirical question. Thus, it appears disputes about irremediablity trace back to larger conceptual disputes. Notably, no author explicitly argued that autonomy is a sufficient condition for permitting psychiatric EAS. Similarly, the normative question of what threshold should be used in evaluating decisional capacity will partly depend on how one weighs the relief of suffering against the unwarranted ending of an incapacitated patient's life. Some have pointed to this tension (den Hartogh, Reference den Hartogh2015) or argued explicitly that the relief of suffering should prevail regardless of decisional capacity (Varelius, Reference Varelius2016b).

Finally, whether psychiatric EAS is compatible with the duty to prevent suicide partly depends on whether one relies on a view that challenges, or instead relies on, current ways of conceptualizing suicide prevention. For example, current practices allow involuntary commitment to prevent suicide. Furthermore, while some argued that psychiatric EAS could prevent suicides, the underlying debated question of whether psychiatric EAS should be considered a form of suicide or not (CCA, 2018; Creighton, Cerel, & Battin, Reference Creighton, Cerel and Battin2017) was rarely addressed explicitly. This could be because the broader literature on the issue of EAS and suicide was excluded by our search criteria, or it could be a gap in the current debate.

Trends in the debate and future directions

The debate over EAS in persons with psychiatric disorders is likely to continue, as it started to intensify only fairly recently. We found that most articles (81%) were written in 2013 or later, despite the fact the Chabot case occurred over 25 years ago. This may reflect the relatively recent increase in the number of psychiatric EAS cases since 2011, with empirical papers providing a more detailed account on the practice raising rapidly only since 2015. Psychiatrists remain divided over the issue in the Netherlands and Belgium (Haekens et al., Reference Haekens, Calmeyn, Lemmens, Pollefeyt and Bazan2017; Pronk, Evenblij, Willems, & van de Vathorst, Reference Pronk, Evenblij, Willems and van de Vathorst2019). This could relate to our finding that the ethical debate is in its relatively early stages. In fact, the low overall direct engagement between authors (9% of mentions) suggests more time and research is needed for the debate to develop further.

Current controversies place parity at the center of an international debate (North-America, Europe and Australia) involving scholars from both clinical and nonclinical backgrounds. If parity arguments rely on physical and mental disorders being similar, some questions will need further study, such as whether mental disorders differ from physical ones, and if so how. There is a longstanding and ongoing dispute about psychiatric diagnosis and prognosis prediction, including in countries allowing for psychiatric EAS based on parity (Allsopp, Read, Corcoran, & Kinderman, Reference Allsopp, Read, Corcoran and Kinderman2019; Insel et al., Reference Insel, Cuthbert, Garvey, Heinssen, Pine, Quinn and Wang2010; Kendler, Reference Kendler2019; van Os, Guloksuz, Vijn, Hafkenscheid, & Delespaul, Reference van Os, Guloksuz, Vijn, Hafkenscheid and Delespaul2019; Vanheule et al., Reference Vanheule, Adriaens, Bazan, Bracke, Devisch, Feys and Calmeyn2019). However, conceptual questions of parity may not be sufficient grounds for a safe practice, as suggested by the fact that guidelines developed in the Netherlands and Belgium often contain additional and more stringent criteria than the law itself. Other important empirical, policy questions of parity need further study, e.g., whether diagnosis and prognosis in psychiatry can, similarly to staging systems in physical illness, be valid and reliable. Furthermore, how some of the consequences of allowing psychiatric EAS may play out (on e.g. the patient–physician relationship, mental health care practice and policy, or suicide rates) needs more research, including monitoring of the practice of psychiatric EAS and some of its policy considerations pointed to by both sides of the debate.

Finally, we found that reasons provided by non-clinicians, mostly in favor of psychiatric EAS, have been laid out in more full-length articles, while clinicians have expressed their view more commonly in shorter, reactive articles. It could be that authors against the practice writing longer articles argued against EAS in general (therefore against psychiatric EAS as well) were excluded by our search criteria. However, surveys show that among clinicians, e.g. in the Netherlands and Canada, there is significantly more support for EAS in terminal and physical illness than for psychiatric EAS (Bolt, Snijdewind, Willems, van der Heide, & Onwuteaka-Philipsen, Reference Bolt, Snijdewind, Willems, van der Heide and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2015; Rousseau, Turner, Chochinov, Enns, & Sareen, Reference Rousseau, Turner, Chochinov, Enns and Sareen2017). Our review suggests more thorough input, perhaps through full-length publications from this group, may further inform the debate about issues that are currently only briefly addressed. Both sides of the debate may benefit from more engagement by mental health professionals other than physicians. Finally, more input from patients e.g. through empirical research focusing on their perspectives is needed to further inform the ethical debate.

Limitations and strengths

Because articles specifically engaged in the psychiatric EAS debate tended to make conditional arguments (i.e. assuming that EAS is permissible for terminal and physical illness), our review does not speak to reasons that are more generally applicable to EAS per se. But this is a feature of the current literature on psychiatric EAS rather than a limitation of our methods. Second, qualitative coding requires judgment. We recognize that others might have grouped the domains differently: e.g. parity-type reasons occurred across domains. Instead of creating one very large domain, we chose to group the most prominent of these (parity of mental and physical) in order to highlight the different topics per content domain. Hence, there may be some overlap between domains. Another example is the notably rare issue of voluntariness, which we subsumed under the decisional capacity domain, even though it is part of the broader concept of an informed request, as this is where it fit more closely. Furthermore, voluntariness and decisional capacity are often considered together in psychiatric EAS laws and guidelines (EuthanasiaCode, 2018; Griffith et al., Reference Griffith, Weyers and Adams2008; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Gastmans and MacKellar2017). Hence, the process of categorization was the result of interpretation. However, strength was that the systematic search strategy covered bioethics literature written by both clinicians and non-clinicians, and data extraction was performed by two independent reviewers. Finally, we did not provide qualitative judgments of the reasons, as the primary intent of a systematic review of reasons is to provide a descriptive overview of the debate (Sofaer & Strech, Reference Sofaer and Strech2012). Therefore, the most commonly presented reasons are not necessarily the strongest or soundest arguments; however, they are likely to have had a greater presence in the debate.

Conclusion

Psychiatric EAS continues to pose important ethical and policy challenges. This review shows that the current debate is in its relatively early stage. As the number of cases increases in countries allowing the practice, with more empirical data becoming available, more direct engagement is needed to address conceptual questions and public policy considerations. This, in turn, will inform policy-making for jurisdictions that consider legalizing the practice.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001543.

Acknowledgements

We thank Alicia Livinski (MPH, MA), reference librarian of the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, USA), Patricia Martin (MA) and Martina Darragh, reference librarians at the Bioethics Research Library, (Georgetown University, USA), for their help in conducting the systematic literature search. We also thank Dominic Mangino (MS, RTT) and Joe Millum (PhD) for their comments provided on an earlier draft of this manuscript. No compensation was provided. Funded in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, USA (M.N., S.K. and M.C.).

Author contributions

All authors have provided substantial contributions to the conception or design, acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published.

Conflict of interest

Each of the authors reports no competing interests.