Introduction

This article addresses the theoretical question of children's sense-making of music they listen to, and reports on the findings of two closely related studies involving the analysis of their graphical notations – produced in answer to a music listening task – and the assessment of the role of age, formal musical training and the characteristics of the musical material on these notations. Rather than providing explanatory mechanisms of musical sense-making (Reybrouck, Reference REYBROUCK and Zannos1999, Reference REYBROUCK and Tarasti2003, Reference REYBROUCK2004), it aims at describing children's actual notational strategies which can be considered as representational tools for sense-making in a listening situation.

In both studies we collected a huge number of graphical notations (425 in the first and 1947 in the second study respectively) with a view to get an overall picture of children's sense-making while listening to music. The choice for this research method was motivated by previous research on children's disposition to represent aspects of their world in symbolic form in general and on the understanding of symbol systems as related to music in particular (Walker, Reference WALKER1978, Reference WALKER1981, Reference WALKER1983, Reference WALKER1987, Reference WALKER and Colwell1992; Sadek, Reference SADEK1987; Upitis, Reference UPITIS1993; Gromko & Poorman, Reference GROMKO and POORMAN1998; and for an overview: Barrett, Reference BARRETT2001, Reference BARRETT2002, Reference BARRETT, Miell, MacDonald and Hargreaves2005; Tan & Kelly, Reference TAN and KELLY2004). As argued by Davidson and Scripp (Reference DAVIDSON, SCRIPP and Sloboda1988) and Walker (Reference WALKER1983), these notations may not necessarily serve as an accurate record of listeners’ perceptual abilities, but rather as a reflection of what elements listeners find important to capture in the music and of what they consider as appropriate representational formats or tools for ‘externalising’ them (see Reybrouck, Reference REYBROUCK2004; Tan & Kelly, Reference TAN and KELLY2004).

Theoretical and empirical background

Studies on the nature of children's graphical notations are related to research on symbolic representation of music and visual representation of music perception (see Appendix C with bibliography of related articles on the Cambridge University Press website for an extensive overview). These notations can be conventional or idiosyncratic but, as a rule, they deal with different levels of specification, abstraction, formalisation and reflection with regard to music as a sounding stimulus. In order to generalise from these notations, there have been several attempts to propose classifications and typologies. Most of them are grounded in cognitive theories of development – in an attempt to describe the developmental paths of children's mental representations and their strategies for making them visual, in theories about perceptual learning, or in recent work on symbolising and knowledge construction in general.

Starting from this theoretical background, we collected and confronted empirical findings from related studies on graphical notations in music-listening tasks. Common to these studies is the finding that children draw on a broad range of notational forms, including self-invented idiosyncratic symbols as well as existing symbols borrowed from the musical as well as other domains: they use letters, words, numbers, icons, pictographs, lines and crosses, directional signs, blank space, colour, conventional music symbols and a number of other signs.

Several researchers, further, have explored also the role of age and formal musical training on children's notational strategies. They found that these notational products change over time as a result of maturation and musical experience: the strategies seem to be influenced by age and prior exposure to music and some transitions become manifest as children grow older, such as (i) an increase in sophistication with notations becoming more detailed and reflective (Barrett, Reference BARRETT2001), (ii) more accurate symbol-meaning relationships (Barrett, Reference BARRETT2000; Upitis, Reference UPITIS1992), (iii) emancipation from context-bound recordings with an increased concentration on musical elements (Barrett, Reference BARRETT1997) and (iv) an increasing range of musical dimensions to be represented (Barrett, Reference BARRETT2001).

Besides age and prior exposure to music, other factors may influence children's notational strategies as well, such as the nature of the task and the kind of musical material presented. Our review of the empirical research revealed a multitude of instructions and tasks that might have influenced, at least to some extent, the outcomes of these studies. More in particular, the test administrations differ with respect to the following four issues: (i) the instructions given to the children (e.g. are they invited to make drawings for themselves or for other people?), (ii) the restrictions and constraints as to what is allowed for graphical depiction (e.g. can the children rely on letters, words, or should they be forced to use only nonverbal means of coding?), (iii) the material that can be used for making their drawings (e.g. pencil, coloured pencil, paint, . . .) and (iv) the way in which the musical material is presented (e.g. how many times is the music listened to? Are the drawings made simultaneously with the act of listening or is there a temporal delay?).

Aims of the study: research questions

Starting from the theoretical and empirical state of affairs, we set up two exploratory empirical studies with the aim (i) to analyse the nature and the quality of children's graphical notations (or drawings) of musical fragments and (ii) to investigate the impact of age and formal musical training on these graphical notations as well as of the specific characteristics of the musical fragment.

These questions have already been addressed in previous studies but most of this research has dealt with a rather restricted set of musical materials – reducing them to, for example, rhythms or single-line melodies – and with (sometimes very) limited numbers of participants. In an attempt to broaden our understanding of the topic, our studies can be considered partly as a replication and partly as an expansion of the previous investigations, with a larger number of participants, with a greater variety of carefully selected or self-composed musical examples, and with scrutinised control for variables not being experimentally manipulated in the overall research design.

Study 1

In a first study, two age groups of elementary school children with or without formal musical training were exposed – in the context of a whole-class test – to five fragments extracted from existing musical compositions, and were asked to make graphical notations. The aim was to reveal the variety of children's graphical notations, as well as the impact of some subject and task variables on them. Another major aim was to develop a classification system of children's notations taking into account the available empirical data as well as the state of affairs of the research literature.

Method

Participants

Fifty-three third-grade children (8–9-year-olds) and 32 sixth-grade children (11–12-year-olds) took part in the experiment, which was conducted in two primary schools in Flanders (Belgium). The schools were selected on the basis of their willingness to participate in the experiment. In none of the classes had children been engaged in any teaching/learning activities asking to create or read informal graphical notations of musical fragments, nor in any kind of training in writing of reading standard musical notations. Initially, we planned to analyse also the effect of out-of-school formal musical training on children's graphical notations, but due to the unexpectedly small number of children who had received such formal training – actually, none of the third-graders and only three of the sixth-graders – we decided to drop this analysis in the first study.

The musical material

The musical fragments were extracts from existing music with the aim to differentiate between different musical characteristics. We selected five extracts on the basis of the prominence or salience of a particular musical characteristic, such as melody (fragment 1), rhythm (fragment 2), dynamics (fragment 3), repetition (fragment 4) and melodic shape (fragment 5). As we aimed at providing real music with at least some ecological validity, there was inevitably some conflation of musical parameters. Moreover, we searched for fragments of a duration of about 15–20 seconds. They are listed below. The score examples are provided in Appendix A.Footnote 1

• Fragment 1 (melody): mm. 1–8 from Michael Nyman, ‘The Piano: The Sacrifice’. (Virgin Records Ltd 1993. CDVE 919. 0777 7 88274 2 9) Duration: 17 seconds.

• Fragment 2 (rhythm): improvised drum solo from Jean Gilles, ‘Requiem: Introit’. (Harmonia Mundi, P 1990, HMD 941341) Duration: 13.60 seconds.

• Fragment 3 (dynamics): mm. 5–12 from Richard Strauss, ‘Also sprach Zarathustra: Von den Hinterweltern’. (DGG 449 332–2) Duration: 21 seconds.

• Fragment 4 (repetition): mm. 1–8 from Michael Nyman, ‘Drowning by Numbers: Great Death Game’. (Virgin Records Ltd, GDVE23, 0777 7 87399 2 0). The four bars are repeated once. Duration: 22 seconds.

• Fragment 5 (melodic shape): 2nd entry of the first phrase of John Tavener, ‘The Lament of the Mother of God’. (Virgin VC545035–2) Duration: 20 seconds.

Procedure

The participants were exposed in a whole-class setting to these five excerpts and were asked to make drawings so that someone else could imagine how this music sounds. The session lasted about one hour and the task administration was done by one of the authors (SL). Children were strongly encouraged to do their best, but it was made clear that this task was not a regular school test.

Each child received a booklet at the beginning of the session consisting of six pages. The first page asked for some personal information (name, date of birth, class or grade at school, kind and amount of formal musical training outside the school), and the five other pages (one for each musical fragment) were left blank. The following instruction was given to the children:

I would like to know how all of you would graphically depict a short fragment of music, so that I, or someone else who is not here at the moment, can imagine tomorrow how this music actually sounds. While you are listening to the music you can work out your representation in your booklet. You are allowed to use all kinds of marks which can be helpful to express what this music means or suggests to you, except letters, words or sentences. It is important also to know that whatever kind of marks you are using, they all fulfil the requirements. There is simply no correct or wrong answer and each one of you can obtain the highest score.

Each musical fragment was played back four times, with an interval of five seconds between each replay. The children made their marks or drawings simultaneously with the music playing. After having represented all five fragments, they were invited to describe and explain their notations in words on the back of the previous page of their booklet.

Data analysis: the categories

To classify the graphical notations generated by the children, we constructed a list of categories. Starting initially from classifications in the existing research literature, we subjected all graphical notations – and their accompanying explanations – to a cyclic analysis, which means that we went through the material repeatedly in an attempt to find an appropriate ‘classification grid’.

As a first result, we made a major distinction between categories that capture the music in a global way – e.g. representing the music by one single pictorial image (a drawing of a situation, an action, an atmosphere evoked by the fragment) or by a musical instrument – and categories that are more differentiated in trying to capture the temporal unfolding of at least one of the musical dimensions. A second major distinction was the difference between simple categories, which consist of only one type of graphical notation and compound categories, which contain elements that belong to different categories.

Starting from these major distinctions, we composed a categorisation grid consisting of 11 distinct categories (see Table 1), which were defined in terms of well-established, research-based criteria. They are listed below with some examples of the children's drawings – selected from both studies – that were assigned to these categories (see Figs 1–7)Footnote 2 together with some comments from the children. The assignment of the notations to the categories was based on the explicit criteria given below. If in doubt, we additionally relied on the children's verbal descriptions to categorise their graphical notations.

• Category 1: No reaction. The participant does not provide a drawing or a representation.

• Category 2: Instrument (simple/global). Global depiction of an instrument in an all-or-none fashion, as one global label assigned to the music (see Fig. 1).

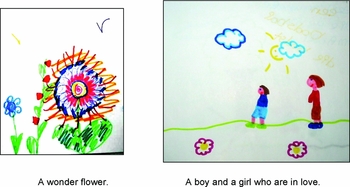

• Category 3: Evocation (simple/global). Everything that is evoked by the music, ranging from drawings of concrete objects or scenes that are globally evoked by the musical fragment to drawings of (people showing) particular feelings or emotions evoked by that fragment (see Fig. 2).

• Category 4: Floating notes (simple/global). Depiction of one or more music notes without any specific reference to specific pitches or durations (see Fig. 3).

• Category 5: Sounding object/action (simple/differentiated). A representation of an ‘object’ that is actually sounding or a sound-producing ‘action’, not as a global event, but as something with at least some temporal unfolding (see Fig. 4).

• Category 6: Analog image (simple/differentiated). Depiction of the unfolding of a musical dimension over time (pitch, loudness, duration) in a pictorial, non-formal way, using elements like increase in size or distance but without one-to-one relationship between the depicted elements and what they are referring to (see Fig. 5).

• Category 7: Non-formal graphical notation (simple/differentiated). Depiction of the unfolding of music in time, not in a pictorial but in a more abstract way, relying on non-conventional graphical notation (lines, circles, graphs) with the intention to depict the musical unfolding in a rather precise way (see Fig. 6).

• Category 8: Formal-conventional music notation (simple/differentiated). Depiction of standard musical notation of notes (on a staff) and other conventional musical symbols (see Fig. 7).

• Category 9: Combination of several global categories (compound/global).

• Category 10: Combination of several differentiated categories (compound/differentiated).

• Category 11: Combination of global and differentiated categories (compound/global/differentiated).

Table 1 Main categories and subcategories

Fig. 1 Examples of drawings that correspond to the category ‘instrument’ with their accompanying verbal annotations

Fig. 2 Examples of drawings that correspond to the category ‘evocation’ with their accompanying verbal annotations

Fig. 3 Examples of drawings that correspond to the category ‘floating notes’

Fig. 4 Examples of drawings that correspond to the category ‘sounding object/action’ with their accompanying verbal annotations

Fig. 5 Examples of drawings that correspond to the category ‘analog image’ with their accompanying verbal annotations

Fig. 6 Examples of drawings that correspond to the category ‘non-formal graphical notation’ with their accompanying verbal annotations

Fig. 7 Examples of drawings that correspond to the category ‘formal-conventional music notation’

Results and discussion

The main results of the first study are listed in Fig. 8, which depicts the overall distribution of the 425 notations (85 children × 5 notations per child) over the 11 categories of our classification scheme.

Fig. 8 Histogram of the distribution of all graphical notations from study 1 over the distinct subcategories

The most important finding of this study was that the vast majority of children of both age groups depicted the musical excerpts with global categories. Actually 93.4% of all notations were of that type. Moreover, differences between age groups and between musical extracts were negligible. The most prominent simple categories were ‘instrument’ and ‘evocation’. None of the other categories seemed to be of major importance. To summarise: elementary school children with no formal musical training and little experience of music listening or music notation do not seem to differentiate much when asked to listen and graphically respond to excerpts from existing music; they also rely on very basic global listening and representational strategies when they produce their graphical notations.

With respect to the impact of the nature of the musical excerpts on children's graphical notations, we observed some differences in the distribution of these notations over the different categories. The most atypical distribution was found for the ‘rhythm’ excerpt, which elicited a remarkably low percentage of notations in the ‘evocation’ category; it was also the only fragment with higher scores for the simple category ‘sounding object/action’. Not surprisingly, the ‘melodic shape’ excerpt elicited relatively few notations that were assigned to the ‘instrument’ category.

Study 2

Based on the results of the first investigation, we set up a second, larger study with four groups of subjects, namely younger and older subjects with and without musical training. Compared with the first study, we made the following adjustments: (i) the musical fragments were composed by ourselves, so as to maximise the specificity and unidimensionality of the musical characteristics, (ii) the number of subjects was increased considerably, and (iii) we organised the recruitment of the participants in such a way that there were musically naive subjects as well as subjects with formal musical training.

Method

Participants

Children from five third-grade classes (8–9-year-olds) and from five sixth-grade classes (11–12-year-olds) from two separate primary schools in Flanders (Belgium) participated in the second study. To guarantee that both age groups would contain a sufficient number of children with a significant level of formal musical training, we also included eight classes from a local music school in our pool of participants. We set as the selection criterion for a critical level of formal training that the children should have followed at least one full year of music instruction, which means that they have all received at least the basics of music theory and solfège. Many of these children with formal training were either third-graders or sixth-graders in the regular school, but the remaining ones belonged to other age groups, ranging from 8 until 13 years. Consequently, we decided to broaden the age ranges of the younger and older age groups in study 2: the younger group consisted of all children below the sixth grade (i.e., 8–10-year-olds), the older group consisted of all children from the sixth-grade on (i.e. 11–13-year-olds). The actual distribution of the number of children who participated in study 2 over the four categories (younger versus older children, children with and without musical training) is given in Table 2.

Table 2 Distribution of the participants in study 2 in four experimental groups

The musical material

In contrast to the first study, the musical fragments were not extracted from existing music, but were generated by the researchers themselves with the aim to maximally ‘isolate’ one of the following six musical characteristics: melody, rhythm (specified here as a gradually accelerating pulsation), dynamics, repetition, melodic shape and timbre. As a consequence, the fragments were much simpler than those of the first study. They were generated on a standard synthesizer, recorded on an audio compact disc, and played back at a standard level of loudness. A short description of the fragments is listed below. The score examples of some of them are provided in Appendix B.

• Fragment 1 (melody). A short melodic line of 13 notes played with piano timbre. Total duration: about 15 seconds.

• Fragment 2 (rhythm). A rhythmic sequence of 27 pulses which are played in succession with increasing speed. Total duration: about 9 seconds.

• Fragment 3 (dynamics). A continuous dynamic development of one single note, starting from a minimal level of intensity, towards a louder level and returning to the same minimal level again. This development is repeated twice with the second development being somewhat louder than the first one. Total duration: about 22 seconds.

• Fragment 4 (repetition). This four-bar musical pattern is repeated twice and is played with piano timbre. Total duration: about 22 seconds.

• Fragment 5 (melodic shape). Two parts (strings-like timbre on a synthesizer) play simultaneously a melodic scale. Total duration: about 17 seconds.

• Fragment 6 (timbre). A succession of four sounds with equal pitch but different timbre. The whole pattern is repeated in retrograde fashion. The timbres were specially chosen to be as unusual as possible in order to avoid too rapid recognition. Total duration: about 25 seconds.

Procedure

The test administration was the same as in the first study. The six fragments were presented one after the other, with the order of the fragments being different from class to class in order to prevent biases due to order effects.

Data analysis: the categories

The categorisation scheme of the first investigation was maintained during this second study. Two adaptations, however, seemed necessary. First, we introduced a new subcategory for ‘instrument’, in the sense that we now also differentiated between children who used ‘instrument’ only as a ‘global label’ without any further differentiation whatsoever and those who used this category as a ‘musical parameter’ that reflects the sounding quality of the music as unfolding over time. An example is given in Fig. 9, which shows the depiction of four instrumental timbres both as a simultaneous global reference without any connection to their actual unfolding over time (Fig. 9a), and as a depiction of the succession of timbral variations that unfold over time (Fig. 9b). As such, the category ‘instrument’ could be assigned to both of the main categories (global as well as differentiated), yielding two different subcategories (instrument/global and instrument/differentiated). The second adaptation concerned the category ‘formal-conventional music notation’, which was broadened to encompass also music notes that actually refer to pitch and pitch relations but without using staff notation. As a result we ended up with a categorisation scheme of 12 categories.

Fig. 9 Examples of drawings that depict the category ‘instrument’ both as a global label (a) and as a parameter (b) with their accompanying verbal annotations

Results and discussion

The main results of the second study are presented in Fig. 10, which depicts the distribution of the children's graphical notations over the categories and subcategories for the six musical fragments altogether. These notations stem from 331 children with a total number of 1946 notations (the total number of notations was not equal to 331 × 6 = 1986, but only 1946, because 20 children from one of the five third-grade classes were exposed to only four of the six musical fragments, due to technical difficulties). The histograms of the impact of the two subject variables (age and formal musical training) are depicted in Fig. 11.

Fig. 10 Histogram of the distribution of the graphical notations of study 2 over the subcategories

Fig. 11 Histograms of the distribution of the graphical notations from study 2 over the different subcategories for children without (upper pane) and with formal musical training (lower pane).

Main results

Most of the notations depict simple categories (91.3%): either global (37.4%) or differentiated (53.9%). Only a minority of children's notations were assigned to the compound categories (7.3%). Compared with study 1, which yielded notations of an almost exclusively global type, we obviously observed much more differentiation in the children's notations. Actually 60.5% of all of them were of the differentiated type.

As to the influence of the two subject variables – age and formal training – on the distribution over the main categories of notations, and more particularly, on the percentage of differentiated notations, the results can be summarised as follows (see Fig. 11):

(i) The influence of age was obvious, with the older children obtaining a much higher percentage of (simple or compound) differentiated categories (77%) than the younger ones (43.5%).

(ii) The influence of formal musical training was obvious as well, be it to a lesser extent than age. The children who received at least one year of training generated 69.6% of the simple or compound notations that were classified in a differentiated category, against 54.3% for the children without training. Moreover, the notations of the children with training were more commonly spread over the distinct categories.

(iii) There seemed to be an interaction effect between age and formal musical training in the sense that in the youngest age group formal musical training resulted in more differentiated notations (63.3% for the trained children versus only 30.7% for those without training), while the oldest age group showed almost no difference (76.6% for the trained children versus 77.5% for those without training).

(iv) With respect to the influence of the kind of musical fragment on the overall results, finally, we also observed a difference in the percentage of notations assigned to the differentiated categories between the distinct fragments (both simple and compound): 58% for melody, 72.6% for rhythm, 65.3% for dynamics, 58.6% for repetition, 43.1% for melodic shape and 63.1% for timbre.

Looking at subcategories

Of all the subcategories, two subcategories account for a very large number of the graphical notations, namely the simple global subcategory ‘instrument’ (32.3%) and the simple differentiated subcategory ‘non-formal graphical notation’ (35.5%). Together they account for about two-thirds of all the notations. A next group of three subcategories – with percentages between 4 and 8% – holds an intermediate position: the simple global subcategory evocation (4.6%) and the simple differentiated categories sounding object/action (8.0%) and formal-conventional music notation (5.8%). All other subcategories are of minor relevance. As to the compound notations, they all belong to these subcategories of minor relevance with the majority of them involving again one of the two above-mentioned dominant subcategories: instrument (global) and non-formal graphic notations.

Conclusion and perspectives

In this article, we have reported two related studies on children's graphical notations while listening to musical fragments. In what follows we summarise these findings together with some conclusive theoretical, methodological and educational considerations.

First of all, our studies confirmed a number of findings from earlier research.

(i) They illustrate the rich variety in children's spontaneous ways of perceiving and graphically depicting music.

(ii) Our data also confirm the findings from previous research concerning the role of age and formal musical education (see Barrett, Reference BARRETT1999 for an overview): children's recordings become less global and context-bound and more concerned with genuine musical ideas and concepts – the musical characteristics proper, so to speak – as they grow older and receive more formal musical training. Somewhat surprisingly, we found the role of formal musical training being less prominent than we had expected, with 69.6% differentiated notations for the trained vs. 54.3% for the untrained subjects. With respect to the subcategory of formal-conventional notations, however, there was a more obvious impact of training, with 17.4% of these notations for the trained vs. 1.6% for the untrained subjects.

(iii) Our findings also show the impact of the musical characteristics of the fragments – both in the sense of their length and complexity and in the sense of the type of musical characteristic that is most prominent – on the nature of children's (informal) external representations. We found, actually, that the level of sophistication of their notations varied considerably between both studies as well as between the different fragments that were used in each study. Study 1 yielded a vast majority of global notations whereas study 2 showed much more notations of the differentiated type. But even within the differentiated notations of study 2, we found considerable difference in the distributions over the distinct subcategories between the different musical fragments.

As such, our results provide additional evidence for two major claims: first, children move back and forth between a range of notational strategies – belonging to qualitatively different levels of musical representational sophistication – rather than moving progressively through hierarchically distinct stages with prior notational strategies being abandoned in favour of newly acquired strategies (Bamberger, Reference BAMBERGER1991); second, the notational strategies which children employ are influenced by the nature of the musical task and the task features which the children perceive as being dominant (Barrett, Reference BARRETT1999, Reference BARRETT2001).

Besides these findings which, to a great extent, confirm the findings of previous research, our studies yielded some important theoretical, methodological and educational issues and queries, some of which we plan to address more systematically in future research.

A first issue is the assumption that children's notations are ‘windows’ on their musical perception and sense-making, with the underlying idea that the view provided by such a window is an ‘actual’ rather than a ‘virtual’ view on the phenomenon of musical understanding (Barrett, Reference BARRETT2000; Davidson & Scripp, Reference DAVIDSON, SCRIPP and Sloboda1988). This assumption, according to Barrett, seems to be somewhat simplistic or misleading in several ways. First, there is the question as to what children actually record in their notations. Do they draw what they know or what they hear? Are the graphic notations to be considered as genuine external representations of sounding qualities or do they function as references to contents that are at some distance from the sounding material? Children may operate at a remove from the aural medium and their invented notations may, therefore, be ‘reflections’ on musical thinking, rather than ‘actual windows’ onto what they perceive (Barrett, Reference BARRETT2000).

A second issue is related to the completely different results obtained in our two studies. Apparently, there is a serious gap between perception and external representation of ‘complex’ musical phenomena on the one hand, and of ‘simple’ musical fragments with isolated musical parameters on the other hand. This finding is of major relevance, as many researchers have maintained that the same mental actions that guide the construction of coherence in small and very simple musical fragments may be helpful in shaping the quality, value and meaning of much larger and more complex musical phenomena (see Elkoshi, Reference ELKOSHI2002 for an overview). Our findings do not confirm this claim: they rather suggest that the relation between both types of musical perception is much more complex. As such, our findings are more in line with Elkoshi's (Reference ELKOSHI2002). As a matter of fact, we cannot generalise from the perception of simple fragments to the perception of the musical composition as a whole, and the other way round. This conclusion has important consequences for future theoretical and methodological research, in the sense that insights gathered from the representation of simplified and rather short musical fragments may be helpful to understand certain aspects of (the development of) children's listening and representational skills, but they may possibly fail in capturing the actual listening strategies that are at work in listening to ‘real music’. The interpretation of the findings of such ‘reductionist’ experiments, therefore, should be supplemented with findings from research which involves more realistic and complex musical material.

A third issue is related to the categories and subcategories that we have selected and used to analyse our data. Although our categorisation grid seemed feasible and reliable, some graphical notations were resistant to our efforts to assign them to one of the defined categories, due partly to the fact that some of them were rather ill-defined, suggesting that our categorisation grid was not yet sufficiently refined to encompass some idiosyncratic representational strategies.

As argued above, the focus of many previous studies of children's invented notations has been on the examination of their notations in isolation from their verbal accounts of the processes and products of their notational activity. Some scholars have already made attempts to probe children's verbal descriptions and explanations of their notations in conjunction with an analysis of their notational products (see Bamberger, Reference BAMBERGER1991; Barrett, Reference BARRETT2001; Elkoshi, Reference ELKOSHI2003; Kerchner, Reference KERCHNER2000; Upitis, Reference UPITIS1992, Reference UPITIS1993). In our study we actually asked the children to write down their verbal explanations in their booklet at the end of the whole-class assessment. Although these verbal accounts clearly helped us in some cases, they were helpful only to some extent. First, especially in the younger age group, insufficient writing skills prevented the children from writing clear and extensive explanations. Second, the general instruction ‘to explain the drawings’ and the impossibility to ask specific follow-up questions resulted in rather general explanations about the drawing as a whole and did not allow us to unravel the meaning or relevance of particular parts or aspects of the children's graphical notations. As such, the verbal explanations were, at best, quite incomplete. Third, the rather long delay between the moment of actual generation of the graphical notations and their verbal explanations may also have jeopardised the validity of these explanations. Clearly, richer, denser and more focused data about children's verbal descriptions and explanations are necessary (see Barrett, Reference BARRETT2001; Tan & Kelly, Reference TAN and KELLY2004). Only by means of such a complementary method, will it be possible to assess the representational quality of children's informal notations in a more appropriate way.

As to the educational issues, it should be mentioned that our studies revealed interesting associations that are generally made with regard to graphical representations and their referents. The issue, however, is whether the revealing of these associations is useful in the context of teaching and learning to really understand music. The answer is not obvious. There are, however, some interesting findings such as the prevalence of global notations over differentiated ones and the prevalence of figural over formal notations. It means that the units of description are at a level that is more global than the units of perception which are at the note level in standard music notation. As such, there seems to be a critical distinction between the strategies of listening that are typical of naïve listening and those that are typical of formal music training that relies basically on standard musical notation.

Finally, our study was an ‘ascertaining study’, with the aim to describe and analyse the development of children's graphical notations under given instructional conditions. Evidently, children's lack of educational experience in exploring instrumental and vocal sounds, and in compositional and notational tasks, may account for some of the limitations in their choice and use of drawings and notational strategies. Besides a better understanding of children's listening and sense-making of music by means of further ascertaining studies, there is an urgent need of design experiments, aimed at improving music education by helping children to gradually and actively build up conventional formal notations out of their more intuitive and informal ways of representing music. The design-based research, especially, is very promising here: it allows researchers to re-construct, re-design and re-implement their findings in one or more design cycles on the basis of what has already been learned. This plea for more design-based research is to be taken seriously, as music educators have suggested already alternative forms of music notation (see Auh & Walker, Reference AUH and WALKER1999). The rigid conventions of standard notation, in fact, are not the most ideal device to learn to graphically encode musical entities (see also Bamberger, Reference BAMBERGER1999, Reference BAMBERGER, Miell, Macdonald and Hargreaves2005). It is appealing, therefore, to question the possibility of providing a social and functional niche for children's multiple ways of constructing and communicating musical meaning in a lively and diverse musical culture.

Appendix A: Score examples of the musical fragments used in study 1

Appendix B: Score examples of some musical fragments used in study 2