“Yes, I should like to perish in Valhalla’s flames! – Mark well my new poem – it contains the beginning of the world and its destruction!”Footnote 1 With those words in an 1853 letter to Liszt, Wagner introduced his Ring poem, the music as yet uncomposed. Perhaps he might more accurately have said “a” rather than “the” world, for something and, indeed, some people, “men and women, moved to the very depths of their being,” remain after the Immolation Scene from Götterdämmerung. If it would be a stretch to call them “characters,” they suggest to us that rebuilding this world is now our task. In Bayreuth’s “Centenary” Ring, the director Patrice Chéreau had them turn to the audience at the close to make that very point. We can, however, readily forgive Wagner that touch of indefinite/definite article hyperbole, given the nature and scale of the drama that has unfolded. Who, then, has populated that world whose beginning and destruction we have witnessed? Who were they? What did they do? How did they contribute to that fate, or resist it?

Gods and Nature (Including the Woodbird)

Let us start, as it were, at the top, although that will instantly require a qualification or two. For the beginning of the Ring as experienced in the theater is not the beginning of the story – or is it? Certainly not if we consider the words of Das Rheingold’s first scene to be the beginning, thinking the “Prelude” lacks its own dramatic content. That scene takes place in an already existing world, of whose earlier history we hear something in the Norns’ scene of Götterdämmerung; we hear – and piece together – hints elsewhere in the drama too. What, however, of the wordless Prelude itself? Is that the world’s creation? If so, by whom (Whom)? Listen to the music’s progress – with further words from Wagner to Liszt in mind: “just think of it! – the whole of the instrumental introduction to the ‘Rhinegold’ is constructed on the single triad of E♭!”Footnote 2 We experience here “the gradual development of the material world … a wholly natural movement from the simple to the complex, from the lower to the higher … matter … spontaneously and eternally mobile, active, productive.”Footnote 3 Those words were written after Wagner had composed this music but were written neither by him nor with him or his poem in mind. However, the theology – or anti-theology – voiced here by his revolutionary comrade-in-arms, Mikhail Bakunin, is very much Wagner’s and arises from a common, materialist, “Left Hegelian” view of spontaneous generation as opposed to divine creation, such as the young Karl Marx, another student of similar politics and philosophy, had voiced a few years earlier.Footnote 4

Why mention that, in a chapter on the characters of the Ring, especially at the start? There are two principal reasons. First, to remind us of the Ring’s complicated narrative structure, both verbal and musical, mythical and realistic: we often find out about acts, ideas, even characters, after the points at which they would have been introduced. That is just as it would be in “real life”: for instance, I tell you about my mother and her family, once we know each other well, not before we meet, notwithstanding the fact that they existed before I did.Footnote 5 Second, also to remind us, before introducing the gods “at the top” of our hierarchy, that they are, in a sense, to quote Ernst Bloch, “gods without their being such.”Footnote 6 Nature ultimately has priority in this world, even if the gods think that they do and act as if they did. They do not stand independent from it, although politics and theology, to a certain extent instruments of their ideological domination, would have the other inhabitants of their world believe that they do. The singular, Christian God is, at any rate, not a character in the Ring.

It may, however, be argued that Nature is. Not simply, nor even principally, in the guise of the earth goddess, Erda, but as a primeval force wronged by Alberich’s theft of the Rhinegold and Wotan’s assault on the World Ash Tree. Nature is a source of wisdom through which the young Siegfried learns fundamental truths. Ultimately, Nature is a force, its despoliation notwithstanding, that might just emerge triumphant over those who have wronged it: in the Rhine flooding its banks, in the fire that burns Valhalla and its denizens. Is Nature a setting, a force, or a character? Perhaps we need not choose; perhaps, in fact, Wagner does not.Footnote 7 However, when Siegfried, prior to his corruption by society, stands closest to Nature, he understands birdsong; moreover, the Woodbird – as close to a vocal representation of Nature as we come – tells him what he must know, leads him where he must go. Truth, if never unambiguous, lies in Nature.

Wotan, Chief of the Gods

Now, rather like the Ring, or indeed the Bible, with its alternative myths of creation, let us start again at the top, with the gods and with their chief, Wotan. “In the cloudy heights / live the gods,” Wotan, in earthly disguise as the Wanderer, tells Mime; “their hall is called Valhalla.” So it is, but that has not always been the case; indeed, it is a recent development. Wotan, at any rate, “reigns over” this Schar: a word that may be understood militarily or angelically (host), socially (company), or in a pastoral, religious sense (flock). That is part of the point. Wotan’s, more broadly the gods’, dominion is priestly. The priesthood, as actually existing priesthoods tend to be, is both religious and political; it relies upon tradition, custom, belief, and ultimately – although Wotan is cagey about this – upon force. “Not through force,” he tells his fellow god Donner, with his hammer; if only to sustain the illusion (Wahn), there should usually be another way.

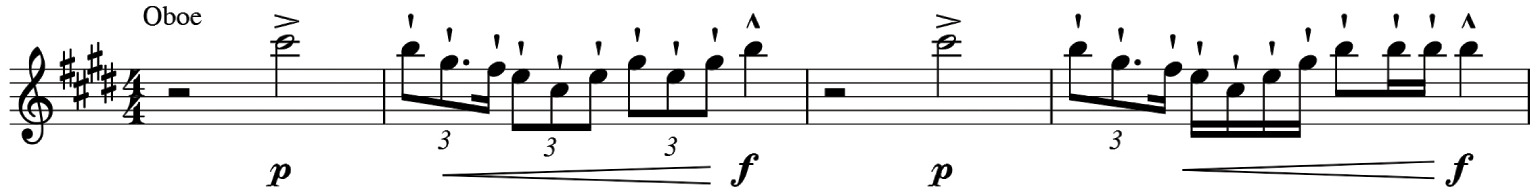

Yet force, that primeval sin against Nature, is how Wotan’s – the gods’ – rule has come about, as we learn in the Norns’ Scene. An “intrepid god” came to the spring of the World Ash, drank its cooling waters of wisdom, paid the price. For, Wagner tells us, there is always a cost, be it political, religious, economic, ecological, metaphysical. Paying with one of his eyes, hence the eye-patch, Wotan broke off a branch; he hewed from it the shaft of his spear, the violence of that deed brought home by the spear motif’s (Example 7.1) abrupt upward leap of a major seventh in the orchestra (Example 7.2).

Example 7.1 Spear motif

Example 7.2 Violence of spear creation

That that was more than the tree could take, more than Wotan should have done, is symbolized by the tree’s withering and its death, the poisoning of its spring. Yet with that deed of brutal, poisonous violence, Wotan became ruler of the heavens and thus ruler of the world. Wagner had learned much from his study of the philosophy of Ludwig Feuerbach, as he acknowledged by dedicating to Feuerbach one of the major theoretical essays accompanying the Ring, The Artwork of the Future, echoing Feuerbach’s Principles of the Philosophy of the Future. Perhaps the most important lesson learned and extended was that human beings (for that matter, giants, dwarves, heroes too) have a psychological tendency to ascribe their positive qualities, above all their capacity to love, to an exterior being or beings. In that process, not only do they deprive themselves of those positive qualities; they thereby invite, permit, enable that external force’s dominion (Herrschaft) over them.

Throughout the tetralogy, there is something ominous, indeed dominating, to the spear motif, closely associated with its creator and owner. It holds its own until finally Siegfried shatters it, scenically and musically. Wotan inscribes on it runes of law, with which he and the alien force of law rule over men, women, and their lives. His intentions have certainly not all been ignoble; he is a dreamer, with the advantages and disadvantages that entails. However, to inscribe them, literally, in dead wood is forcibly to perpetuate arrangements that have had their day. He must learn otherwise, and eventually does, yet not before having fulfilled his dream of Valhalla, a sacerdotal fortress in the sky where, as he greets it, “safe from fear and dread,” the gods will rule in eternity. (That they need to be safe from fear and dread suggests that, at some level, Wotan knows they cannot be, that there is no eternity, especially when it comes to dominion.) And so, he involves himself in a bargain with the giants, his builders, which he cannot keep; that is, he cannot keep to his own laws, his own runes. As the anarchist Wagner, friend of Bakunin, would tell you, such is the way of law, of political and religious power, of power relations tout court.

The Valhalla motif, the other principal theme associated with Wotan personally, is first heard softly, dreamily, as the young(ish) god imagines it, although even then, it has already been revealed, during the interlude between the first two Rheingold scenes as the other side of the motivic coin to Alberich’s curse, the latter’s B♭ minor paralleled by the relative major, D♭, of Valhalla (in which both Das Rheingold and the Ring as a whole will conclude).

Example 7.3 Valhalla motif

Example 7.4 The curse (trombones)

What a later, serialist generation, heavily influenced by Wagner and successors such as Debussy, would term all musical “parameters” – melody, harmony, rhythm, and timbre – cooperate in the transformation. The Ring’s baleful song is voiced by cor anglais and clarinet reeds – the future of Tristan und Isolde not so distant – as scenically, if only in our heads, Rhenish tides at horizon become clouds. Harmony shifts, shedding dissonance and pungency of timbre as one. Softer-grained violas come to the fore, paving the way for the rhythmical transition towards Valhalla. That first soft, dream-like statement of the Valhalla motif proper is heard almost before our ears and mind realize any transformation has taken place. Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, another dark tale of a castle fortress and doomed inhabitants, may have been born here in this transition, a process Wagner more generally and, in my view, quite rightly termed his “most delicate and profound art.”Footnote 8

By the time that Wotan has paid the giants, through deceit and brute force, “through theft” – as Loge has told him he must, in order to survive – and thereby enabled the gods’ entrance into Valhalla, both motif and orchestration have hardened. They dazzle, a little too brazenly. Dreamed horns (Wagner marks them weich, or “tender”) have been transmuted into the public display – almost “trespassers will be prosecuted” – of fortissimo full orchestra, at which the Rhinemaidens’ sung accusations gnaw away: “false and cowardly” are the revels above, a charge underlined by chromatic C♭ minor chords, piercing a diatonic rainbow bridge and fortress that are simply too sure of themselves. However, Wotan knows, even if he will not admit it, even if the other gods do not know it, that the gods’ rule, even at its apparent zenith, is now doomed.

Thus, when we see Wotan next, in the second act of Die Walküre, he is a man who has begun to change. He has sired a good number of children from women other than his consort – for Wotan and Fricka, read Zeus and Hera – but that is what patriarchs do. More importantly, encouraged by Erda’s words, he has begun to reflect upon his and the world’s predicament. The children of whom we know, and whom we meet, are the Volsungs – Siegmund and Sieglinde, from a mortal woman, unnamed – and the Valkyries, from Erda. Earthly heroes and the Valkyries who take them to (supposed) immortality in Valhalla serve one purpose for Wotan: to protect him and the gods, above all from Alberich. Siegmund is even intended – as ultimately is Siegfried – to win back the Ring from Alberich. Valhalla thus proves anything but “safe from fear and dread”; instead, it intensifies those feelings. As well it might, for, as Fricka’s ruthless logic points out, the tragic dilemma is entirely his own: like that of the modern political and religious order he symbolizes.

As Wagner wrote in a celebrated letter of 1854, immediately prior to starting work on the score of Die Walküre, Wotan is the “sum total of present-day intelligence,” not only an individual character.Footnote 9 He is, essentially, where the world is, nowhere more so than in his second-act scene with Brünnhilde. In the course of this self-torturing monologue, in which Brünnhilde serves only as a foil, Wotan truly discovers for himself the impossibility of his situation and thus wills “the end.” He needs a free hero to rescue the order he has created, yet he also needs to control that hero’s deeds, thus removing his – “her” would be incomprehensible to Wotan and Wagner alike – freedom. Not for the last time in the Ring, though, Wagner the dramatist knows better than Wagner the theorist or Wagner the man-in-real-life, for Brünnhilde (see below), if incapable of nominal “heroic” status, nevertheless becomes indispensable to this process. Dramatic irony indeed. Faced with his insoluble dilemma, Wotan instead comes to will oblivion: first political, eventually metaphysical. We hear not merely repeated but developed, in well-nigh Beethovenian fashion, a motif that has since been named – not by Wagner, though – “Wotan’s frustration.”

Example 7.5 Wotan’s frustration

Itself born of the spear motif, it points to the source of Wotan’s problems: pursuit and exercise of power. Its developmental recurrences seem to hark back to an older operatic tradition, punctuating, as it were, recitativo accompagnato with something equating structurally to ritornello. (If only Wagner had known Monteverdi’s music; he is certainly inspired here by Gluck and Mozart.) “I, lord of contracts,” he declares, “am now a slave to those contracts.” That, then, marks the start, if only the start, of Wotan’s conversion to the pessimistic idea of the nullity of human existence. Via his reading of Arthur Schopenhauer, Wagner had grown increasingly convinced of that since completion of the text of the Ring poems and the composition of Das Rheingold; the idea would permeate ever more strongly the music of those dramas to come. Returning to the phenomenal world, Wotan must, quite against his inclination, either as god or as father, sacrifice his own son, Siegmund. Only then will Fricka’s wrath (on which, see below) be appeased; only that way will the rule of the gods be maintained.

When, a generation later, we see – we hear too, with wondrously floating, “wandering” chords – Wotan as the Wanderer, conversion has progressed. The idea of the Wanderer had already a considerable German Romantic pedigree. Think of Schubert’s song, closing “There where you are not, there is happiness,” or Caspar David Friedrich’s painting, Wanderer above the Mist. There are, however, wanderings aplenty throughout the whole of the Western tradition, Homer’s Odyssey a case in point. In his essay A Communication to My Friends, Wagner had already drawn connections between Odysseus and earlier alienated, wandering characters in search of redemption: the Flying Dutchman, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin.Footnote 10 Wotan takes his place here in a development of so many earlier tendencies, within a more pessimistic, Schopenhauerian context. For the resigned Wotan as Wanderer takes his leave not from Odysseus’ return to his beloved Penelope – Wotan and Fricka have no issue and never will – but to Schubert’s and Friedrich’s antiheroes: resigned, unwilling to act, awaiting the end. Following their riddle contest, Mime’s head is his, yet he leaves it – not without malice – to Siegfried. He wins the upper hand in his final confrontation with Alberich by declining to engage. Alberich may still lust after the Ring of power; Wotan has (partly) learned.

In the momentous first scene of Siegfried’s third act, its Prelude having prepared the way for the perepiteia (turning point in ancient Greek tragedy) as a whole, Wotan may now reject Erda and her dictates of Fate. There may be an element of chauvinism, even misogyny, in the speed of transformation from “All-knowing! Primordially wise!” to “Unwise one,” but it is more than that. “What once I despairingly resolved in the wild anguish of internal conflict,” the conflict of family, society, and politics, “I shall now freely accomplish, gladly and joyfully.” And yet, while, having shed himself of the burden of that care – or so he thinks – Wotan cannot bring himself to acquiesce before Siegfried. The young Wotan is not entirely dead; nor will he ever be. Characters develop. Rarely, however, in plausible dramas, do they become something entirely different, any more than the head of an old political order will plausibly lead a new, revolutionary order. Here Wagner the dramatist, who had lived through the actual, political challenges of revolutionary defeat, knew better than Wagner the younger theoretician, who had called upon the king of Saxony to lead a “republican monarchy” and who had initially intended, in Siegfrieds Tod, to have the rule of the gods continue, purged and purified by the arrival of Siegfried in Valhalla. That had been almost a reversion to the old operatic necessity of a “happy ending,” the lieto fine. Neither life nor politics worked like that, however. At a dramatic level, Wagner had known that all along – as seen in Rienzi, The Flying Dutchman, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin.

A Wotan philosophically converted yet not entirely transformed must still fight, must still have his spear shattered by the young hero’s sword. There is no avoiding the moment of the revolutionary deed, however bitter its consequent disappointments. Moreover, when Waltraute visits Brünnhilde in the first act of Götterdämmerung, we learn that Wotan in Valhalla continues to behave with fear and dread, not with the joy of which he spoke to Erda. Despondently, he awaits the end; even that is more difficult than he had assumed. Gloom and foreboding, of Wotan and the world he has in good part created, pervade the score of Götterdämmerung, even if he never sets foot on stage. It is arguably more “his” drama now than ever before.Footnote 11 The most difficult lesson to learn – arguably he never does – is to await the acts of others. When Valhalla burns, a release both personal and political, it is at a moment of someone else’s choosing. Had Wotan asked himself riddles with the skill he did Mime, he might have learned that. Who, however, as even the Sphinx never asked, does that?

Alberich, Lord of the Nibelungs (with the Rhinemaidens)

The Wanderer describes himself to Mime in the second, “riddle” scene of Siegfried, as “Licht-Alberich” (“Light-Alberich”). With the advantage of hindsight, Wotan accepts that not only are he and Alberich antagonists for the Ring of power; they are two sides of the same coin of what Nietzsche, steeped in Wagner’s influence, would dub the will to power.Footnote 12 The musical connection has long been clear from the transformation, outlined above, of Alberich’s Ring and curse into Wotan’s stronghold sure. That stronghold will never be so strong and sure as Wotan thinks, though, for Alberich’s material will always be immanently corrosive. Indeed, when Wotan, as power-hungry as his antagonist, wrenches the Ring from Alberich, we hear “a musical re-creation of the moment when Alberich stole the gold.”Footnote 13

Let us therefore take a step back to that other story of primeval violence against Nature at the opening of Das Rheingold. We observe an Eden of sorts, albeit with a bitter, savage, even world-historical twist. Alberich is a dwarf, an ugly one at that, in a world of superficial beauty, of hedonism. He is not, at this stage, lord of anything or anyone; he is a lowly being in a world ruled over by the gods. Alberich would play with the Rhinemaidens, yet their reaction is to toy with his feelings, feigning interest, one by one, only so as cruelly to spurn him. “Let us see, handsome one,” says Wellgunde, having swum over to him, she far more agile, mobile than this awkward, sneezing creature, unsure of hands, of feet, of who he is: not a fish out of water, but rather a dwarf therein. “What [do] you look like? – Pfui! You hairy, humpy fool! Black, horned, sulfurous dwarf! Find yourself a sweetheart who could bear you!” And yet, while emphasizing difference, the wheedling, slippery chromaticism of Alberich’s music also already hints at a threat to the almost bland diatonic play of the Rhinemaidens. Chromaticism in Wagner’s tonal universe colors, invades, corrodes, destabilizes, without ever quite transforming itself into Schoenberg’s “air of another planet.” Instability of rhythm is just as important here too. To quote Theodor Adorno, in Wagner’s music “all the energy is on the side of the dissonance.”Footnote 14 Or as Goethe’s Mephistopheles, musically transformed into the chromaticism of Liszt’s Faust Symphony, has it: “I am the spirit that always negates.”Footnote 15

Wagner said that he “had once felt every sympathy with Alberich, who represents the ugly person’s longing for beauty.”Footnote 16 And yet, the taunting and the misery aside, there is something within, something that has been there all along, that has Alberich act as he does. “How a blazing fire burns and glows in my limbs! Rage and desire, wild and powerful, sends my spirits into turmoil! – Though you might laugh and lie, lustfully I crave you, and one of you must succumb to me!” Alberich is no “noble savage” – be that understood in terms of literary pastoral or Rousseauvian Enlightenment. No such thing exists in the Ring, as Siegfried’s boorishness will confirm. Alberich “finally stops, breathless and foaming with rage, and shakes his clenched fist,” exclaiming, “Might this fist even seize one of you!” For Alberich, like Shakespeare’s Caliban a “salvage and deformed slave,” comes close to Aristotle’s “bestial man,” a characterization placing both on the edge of rational “civilization,” which may or may not be read as having a racial or at least “othering” element.Footnote 17

Alberich has been confirmed in the hopelessness both of his specific position vis-à-vis the Rhinemaidens – they will never “love” him – and more generally of this society. When he hears Rhinemaidens sing of the gold they guard, he has been pushed to do something they had never guessed anyone would. He renounces love, a hopeless cause for him anyhow, and seizes the gold, winning the “measureless might” Wellgunde has blithely, foolishly hymned. “Alberich wrenches with terrible power,” read Wagner’s stage directions, “the gold from the reef, and then plunges into the depths, into which he quickly disappears. Heavy darkness suddenly descends upon all quarters. The maidens dive abruptly into the depths in pursuit of the robber.” On his curse, the violence of the diminished seventh C minor perversion of the original C major gold fanfare makes clear that Alberich and what Wagner, in correspondence, termed his “liebesgelüste” (erotic urge), have entered the world forever.Footnote 18 This “fall,” as in the Bible’s Creation myth, symbolizes in one sense the introduction of unfree labor into the world.

And yet, although Alberich will win power, he will never be happy, never find fulfillment for any of his urges. In capitalism, one never does; it would not be capitalism if one did. From the grand scale of the imperial power’s quest for new colonies, markets, and so forth to the personal level of the modern consumer’s never-ending quest for a new and then a newer iPhone, the psychology of capitalist economics is foretold. When Alberich makes his final appearance, he will counsel his son, Hagen, always, as he himself has done, to “hate the happy.”

We should not, however, view that world in which amoral nymphs swam carefree in the Rhine as a golden age; that no more exists in the Ring than the “noble savage.” “The state of nature,” wrote Hegel, in his Philosophy of History, well read by Wagner, “is far more a state of injustice, power, untamed natural urges, inhuman deeds and feelings” than society.Footnote 19 Does Alberich’s theft, then, in the Christian tradition, constitute a felix culpa?Footnote 20 It has elements of that. Yet, his fall – thus temporal rise – is portrayed darkly indeed. Having taken possession of the gold – which had never previously been possessed, let alone owned – Alberich has effectively transformed it into capital. Here Wagner shows the strong influence of contemporary socialist thinkers such as Bakunin and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.Footnote 21 Indeed, the actor and director Eduard Devrient, who worked – uneasily – with Wagner in Dresden, noted in his diary that the “destruction of capital” was a “hobby horse” for Kapellmeister Wagner as he began to formulate the Ring project.Footnote 22 In between the first and third scenes of Das Rheingold, Alberich has been busy. The process is essentially as outlined here by Proudhon: “How much is a diamond worth which needs only to be picked out of the sand,” or gold from the Rhine? “Nothing; it is not a product of man. How much will it be worth when cut and mounted? – The time and expense which it has cost the laborer. Why, then, is it sold at so high a price? – Because men are not free … What, then, is the value which is based upon opinion? – Illusion, injustice, and robbery.”Footnote 23 Welcome to Nibelheim, to which Wotan and Loge journey to try to redress Wotan’s fateful bargain with the giants.

Deep in the bowels of the earth, Alberich is lord, king, factory-owner, dictator. Consider him as you will, so long as you bow down. He has brutally suppressed his brother Nibelungs, Mime included. They work for him, enslaved, like workers in nineteenth-century factories. They will always be on their guard, he tells them, never knowing when he is watching, for the Tarnhelm, wrought by Mime, has granted Alberich the (totalitarian) gift of invisibility. An earlier age might have thought of secret police; our online activities and the harvesting of data by international corporations come perhaps closer still to the horror and the danger. And yet, like any capitalist, Alberich is never satisfied; he wants more. (Facebook never stops “developing.”) “Do you see the hoard that my host has accumulated for me?” he asks. That, however, is just “for today”; it will grow mightier still. “With the hoard,” he continues to boast to his visitors, “I will, I think, work miracles: the whole of the world I shall win to be my own.” He might almost have been writing the Communist Manifesto – as Marx just had been. Man, dwarf, even god: all could alienate their essence in the state, in capital, even in what they construed to be love, just as much as in God. In both Capital and the Ring, both building upon Feuerbach, they do. The Ring of power, forged from Rhinegold, gleams and intimidates as what Wagner himself dubbed a “stock-exchange portfolio.”Footnote 24 Alberich rules, like any businessman, as personification of capital.

“The relationship of industry and, in particular, the world of wealth to the political world is one of the principal problems of modern times,” we read a little earlier in Marx.Footnote 25 And such is the struggle between Wotan, Alberich, and their progeny in the Ring. A crucial distinction would be that, for Wagner, traveling between anarchist Bakunin to world-denying Schopenhauer, all power relations merit hostility, even those, such as “love,” which may initially seem forces for good. Alberich’s plan is to storm Valhalla with his band of enslaved Nibelungs and win the gods’ fortress for himself. That would be a fine revenge for his earlier misery, or so he thinks. He helps destroy Wotan, just as capital helps destroy traditional forms of authority, yet he never wins, and certainly never wins a happier life. The curse he utters on losing the Ring to Wotan falls on him too. In Siegfried, he is still more eaten up with envy, in thrall to the Ring’s power – as much the power of power-lust as anything it can actually “do” – than previously.

One final thing: unlike Hagen, unlike the gods, unlike Mime, unlike the heroes we have seen, Alberich may well survive the final conflagration. We never learn what becomes of him: surely no accidental ambiguity. The Rhinemaidens, though, summoned by Brünnhilde, retrieve “their,” Nature’s, gold – at least for now. Will the whole “cycle,” if cycle it be, start again? That, you may have guessed by now, is up to us.

Other Gods

Fricka

Next to Wotan, the most fully drawn god is his consort, Fricka. She is ever aware of her status; she jealously guards it against objects of his roving eye. She – like Brünnhilde later – views the Ring as a sign of marriage. For Fricka, it is an instrument of control that will keep her husband close to her and generally serve as an instrument of her divine guardianship of marriage. The poison from their (now) loveless marriage drips through the tetralogy. In Wagner’s words:

Alberich and his ring could not have harmed the gods unless they had already been vulnerable to evil. Where, then, should this evil’s germ be found? Look at the first scene between Wodan and Fricka – which leads ultimately to the scene in the second act of Die Walküre. The firm bond binding them both, springing from the involuntary error of a love that sought to prolong itself … sentences them both to the mutual torment of a loveless union.Footnote 26

Like the laws carved on Wotan’s spear, their union had once had validity; now it has hardened into something externally imposed. Moreover, given their godly status, it is imposed upon the world at large, not just upon the two unhappy sometime lovers. (The Norns tell us that Wotan had once loved Fricka so much that he had been willing to sacrifice his one remaining eye to win her.) Such, for Wagner, is marriage; it is no coincidence that marital unions in Wagner’s dramas rarely have issue.

As the guardian of wedlock, “lock” being the operative term, Fricka is also the voice of custom. Moreover, Wotan’s “struggle,” in that Walküre monologue, is, Wagner wrote, between “his own inclination and custom (Fricka).”Footnote 27 Brünnhilde says and does what he would like to do as man, yet cannot; Fricka pushes him to do what he must as god. She is outraged by Siegmund and Sieglinde, Wotan’s own children – making her angrier still – disregarding marital bonds in a new union that is extramarital, adulterous, and incestuous. Wotan, more or less voicing Wagner’s thoughts, sees no problem. When was ever such a thing seen before, she asks? It does not matter, answers Wotan; you have seen it now. As in Wagner’s Opera and Drama theoretical analysis of the Oedipus myth, there has been no crime against Nature; the Volsung twins will produce healthy offspring (Siegfried), just as Oedipus and Jocasta had. Those children had merely offended the “wonted relations” of a familial society whose revenge was without mercy.Footnote 28 They offend Fricka, the society and customs she must defend. That is who she is, what she is for. So much for the “freedom” of gods. That which imperils divine order and rule must be stopped.

That is how, with unsparing yet unanswerable logic, Wotan’s long-suffering consort ensnares him and elicits his pledge to do her bidding, to avenge her – and traditional society’s – honor. “Is it then over for the eternal gods, since you sired the wild Volsungs? … Your august, sacred family is worth nothing.” He rips apart the societal “bands you yourself have tied, laughingly dissolving your rule over heaven.” Therein lies Wotan’s weakness; Fricka focuses on it remorselessly, showing that the fiction of a free hero who will rescue them is nonsense. Siegmund, created by Wotan, is no freer than they are. Magisterially, she has her husband swear to sacrifice his own son to “my honor.” And yet, there is pathos on her side too. Why should she be surprised, she asks, when her own husband had been the first and most persistent offender?

Fricka then, is both a participant in a family tragedy and representative of an outdated yet still immensely powerful social morality. However, the hubristic zenith of her power initiates her downfall. Such is the way both of tragedy and of the post-Hegelian dialectics in which Wagner thought. Fricka wins, yet her victory is hollow. We never see Wotan with her again. In Siegfried, he wanders the world, mixing with those mere mortals at whom she expresses haughty revulsion. When, in Götterdämmerung, her name is invoked by humans at the Gibichung court, once again to safeguard marital bonds, she can do nothing. Hers is a cult whose day has passed. It is, after all, Götterdämmerung: twilight of the gods.

Freia, Donner, and Froh

The other “full” gods, brothers and sisters to Fricka, are cipher-like: more representatives of dramatic and divine functions than full-drawn characters. That seems at least in part to be deliberate. Das Rheingold, the only drama in which they appear and indeed play any meaningful role, is a purposely frigid world, to be contrasted with Volsung love and humanity in the ensuing first act of Die Walküre. Music associated with Freia, Donner, and Froh, then, is identical to that of the objects associated with them. (Wotan and his spear arguably share the same motif too; yet it is not the only music associated with him and proves more amenable to development.)

Freia’s golden apples bring the gods immortality. When the gods lose her to the giants, they turn gray. In a crucial dramatic parallelism and dialectic, she is also the goddess of love – at least nominally, although, in such a power-ridden world, it is not entirely clear what that means.Footnote 29 Wotan’s willingness to sacrifice her (love) first for Valhalla, and then for the Ring, shows us his values.

Donner, with his hammer, proposes resolution of the situation through brute force, which is too much (even) for Wotan. His hot-headedness is put to better use in fomenting a thunderstorm, to be followed by Froh’s rainbow bridge, which will lead the gods on the deluded, illusory majesty of their entry into Valhalla. Vocal types are as one might have expected: Freia a lightish, silvery soprano, Donner a deep baritone, Froh a lyric tenor.

Loge

Loge is strictly a demigod; he thus suffers less than his kinsmen from the loss of Freia’s apples. His semidetachment leads them, with the cleverer Wotan’s exception, to distrust Loge, yet enables him to act as voice of instrumental reason. Less bound to their privilege, he can assess the situation for what it is: not, unlike them, for what he wishes it were. When the gods seemingly have no alternative but to give up Freia to the giants – or, perhaps, to give up Valhalla, a prospect, tellingly, never discussed – Wotan consults Loge. Loge finds a way out. It may be a catastrophic way out, but that is hardly his fault; at least, it is not something for which he would take responsibility. His strength, born of his roots in the Norse trickster god, Loki, is intellectual criticism. Indeed, one might call him the sole intellectual in the Ring. (Competition is not fierce.) Like reason itself, he is available to all; he counsels Fricka concerning the Ring’s possible marital advantages too, when she will deign to speak to him. He also advises Fasolt that the Ring is worth more than the rest of the hoard put together – thus sealing the poor giant’s fate.

Words are Loge’s weapon; so is fire. If Siegfried has – misleadingly, in almost every respect – been likened to Bakunin, Loge is a much better candidate.Footnote 30 Indeed, Bakunin’s combination of pyromania and Left Hegelian criticism of the established order may be seen reproduced, even dramatized, in Wagner’s prescription of a “fire cure” for Paris: seat, for him, of so much of the very worst of modernity.Footnote 31 The gods’ entrance into Valhalla, punctured as it is by the Rhinemaidens’ plaints and Loge’s (Young Hegelian) criticism – “They hasten to their end, they who imagine themselves so strong and enduring” – is already a dance of death. It is rendered all the more slippery by the destabilizing, negating, Faustian chromaticism of Loge’s motif. Alberich has no monopoly on what, after all, is in itself neither “good” nor “bad” – and Loge surely knows his own mind better than Alberich. When Loge returns, it is as fire itself, encircling Brünnhilde on her rock, and then in the great, final conflagration. His critical work done, his flickering flames may – usually – be seen on stage; they will certainly be heard in the orchestra.

Erda, Earth Goddess

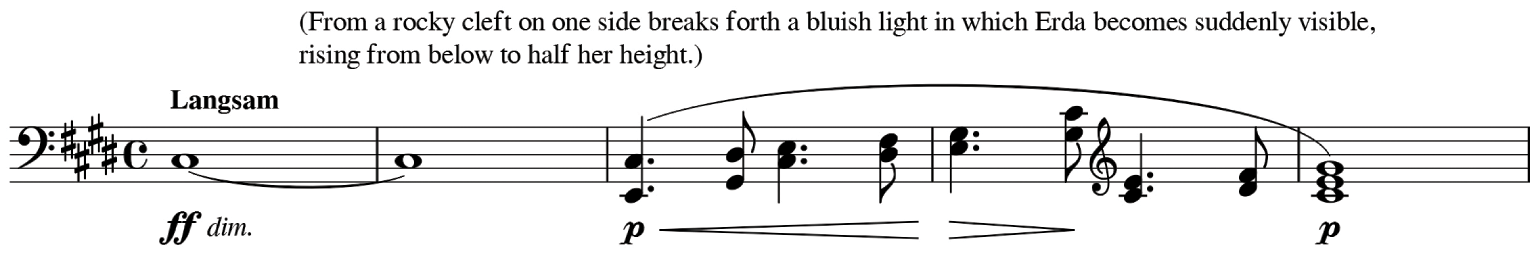

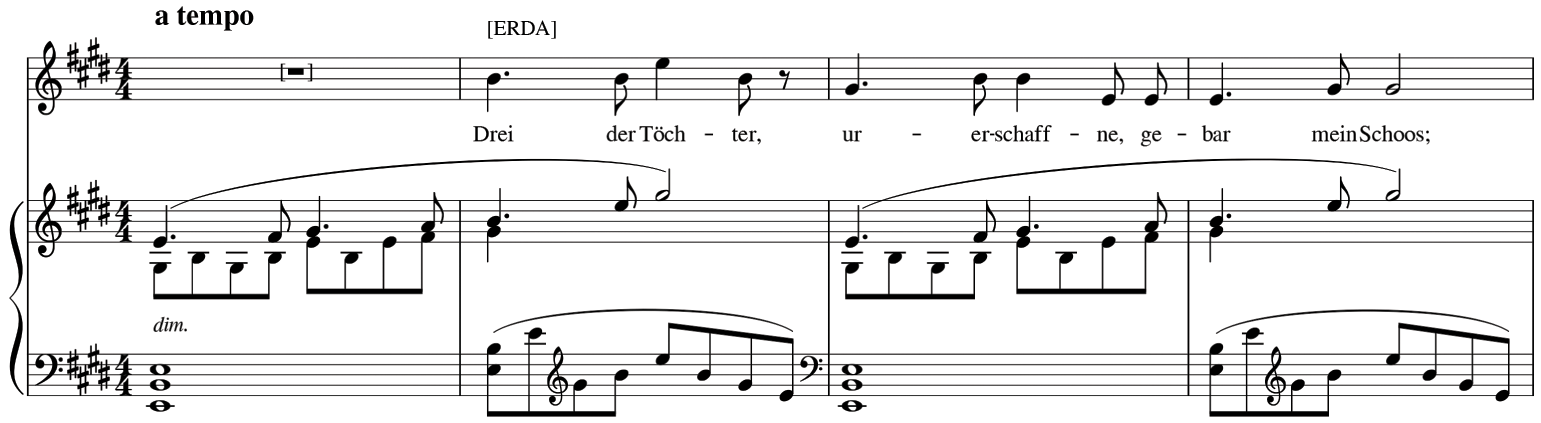

Erda’s appearance in Das Rheingold foretells the end, her motif awaiting another inversion into that of Götterdämmerung. It is her insistence, heard with that initial inversion, that a “dark day dawns for the gods,” which changes Wotan forever. Henceforth an element of metaphysical reflection will never quite be absent. She is mysterious and speaks with an eternal wisdom quite different form Loge’s reason.

Example 7.6 Erda motif

Ideally a contralto, or at least deep-toned mezzo, will emphasize her difference from all others. Wotan is determined to learn more; in the time – at least a generation – between Das Rheingold and Die Walküre – he seeks her out, possesses her. Consensually or otherwise, the Valkyrie daughters spring from that act of possession.

There remains, as would befit the instigator of quasi-religious conversion, Schopenhauerian avant la lettre, something mysterious to Erda. She can nevertheless be understood in certain respects to embody Fate.Footnote 32 With the first scene to the third act of Siegfried, Wagner returned to composition of the Ring, musical and dramatic imperatives transformed by work on the more overtly symphonic scores of Tristan and Die Meistersinger and their overtly Schopenhauerian (broadly speaking, politically pessimistic) dramas. Wotan here hopes at first that Erda will help him “hold back a running wheel.” He realizes, via her protestations – Wagner at least hints at a nagging wife, an echo of Fricka – that Fate is also a form of power to be shunned and dismisses her. “The wisdom of the primeval mothers nears its end: your knowledge is obliterated before my will.” It is, perhaps, an act of violence, although not so unambiguous as translation may suggest. For Wotan, and we are always, for better or worse, encouraged to view things through Wotan’s eye, it is also an act of renunciation. We shall not see Erda again.

The Norns

The three Norns – and, in a sense, two of the Valkyries, Waltraute and Brünnhilde – continue in Götterdämmerung their mother Erda’s tale of Fatal wisdom. In the first scene of the Prologue we see the rest of the Ring-cosmos beginning to catch up with Wotan’s dismissal of Erda, with his willing of metaphysical – probably physical too – oblivion. Fulfillment of that act may be said to be the stuff of Götterdämmerung as a whole, again returning us to the idea, partial yet not absurd, that the Ring is Wotan’s story, and that most, if not all, of the characters have something of him in them. The Norns – no names: just First, Second, and Third – weave the web of Fate, as they sing of the world over which it has apparently hitherto ruled. We learn of Wotan’s earliest deeds from them. Other characters and their actions are reexamined, retold in ways partly old, partly new. Memory and discovery work like that. Alberich’s curse gnaws away at the rope – a new perspective this, complementary to, yet not identical with, Wotan’s willing the end – and it breaks. We may already have guessed that musically, from the world-weariness of the opera’s opening E♭ minor chords: slow, laden down with chromatic, dramatic, even traumatic weight. Whatever it was the sisters were doing is ended: be it exchange of cosmic gossip, perhaps of questionable veracity, or retelling, even creation, of the “eternal knowledge” they claim. The Norns return to their mother, we are told. Like many others, they await the end.

Giants: Fasolt and Fafner

The arrival of Fasolt and Fafner in Das Rheingold is a musical coup de théâtre endearing in its clumsiness, intentional or otherwise. Their motif is simple, stable, diatonic, difficult to imagine developing into anything other than what it is: like those it depicts. They are honest workers, so it seems, whose toil has built Valhalla for Wotan. He has promised them the beautiful Freia as their wage; they stand their ground as he would extricate himself from the bargain, so he must find something for them in her stead. That is Alberich’s hoard, or so he hopes. Yet what Wotan and indeed Fafner have not allowed for is that Fasolt, the opera’s only character with a glimmer of goodness, will genuinely fall in love with Freia. It echoes, perhaps, the teasing of Alberich; yet this unbeautiful misfit, another victim of Wotan’s order, feels something more tender, more human. It is the love of which others sing yet which they never seem to have experienced. Fasolt therefore cannot bear to let her go until the piling of the hoard includes its final piece: the Ring, finally hiding his love from sight. Contemptuous of his brother giant’s weakness and immune to it, Fafner seizes his opportunity to make off with more than his fair share of the spoils. Advised by Loge to keep the Ring, Fasolt makes to do so. Fafner slays him, exiting with the hoard in its entirety, Ring included.

Fafner hoards less as a rapacious capitalist, more as a rentier. With the Tarnhelm, he transforms himself into a dragon, so as to repel treasure-seekers. “What I lie on, I own,” the slothful bass sings, utterly in thrall to the protection of something he does not, will not use. In French socialist terminology, he is oisif (lazy), not actif. So fearsome are his appearance, reputation, and the mere sight of his Neidhöhle vale that no one goes near. The giants’ theme may not truly have developed, but its timpani perfect fifth has slowed and decayed, transformed into the ever-corrosive tritone. Only the boy without fear, Siegfried, his music as yet as carefree and diatonic as Fafner’s is the opposite, will dare penetrate this musico-dramatic lair. He slays Fafner, the last of his giants, with Notung, the sword of revolution.

Siegmund and Sieglinde (with Hunding)

Children of a mortal woman and the mysterious “Wolf” or “Wälse” (English, Volsa) – they never learn that he is Wotan – the twins, Siegmund and Sieglinde, have long been separated. Siegmund comes to Sieglinde’s hut, seeking shelter from a storm. We hear a solo cello line, tender beyond anything imaginable in the loveless world of Das Rheingold.

Example 7.7 Die Walküre opening, cello solo

It speaks immediately, better than words ever could, of sexual attraction and even of a tenderness already extending beyond the merely sexual. When Sieglinde’s brutal husband, Hunding, returns home, he senses an untrustworthy identity in their eyes. Siegmund, or “Wehwalt” (“Woeful”) as he calls himself, recounts a tale of outlawry, of society as the repressive enemy both of him and of human flourishing: typical of Wagner’s charismatic heroes, from Rienzi to Parsifal. He is brave – not fearless, as his future son, Siegfried, will be – and has rescued a woman, as he will again, from forced, loveless marriage. (For Wagner, if all marriages are loveless, some are more so than others.)

Such is enough to make Siegmund Hunding’s mortal enemy, for it was Hunding’s clan from whom Siegmund had rescued the woman. Bound by the laws of hospitality, Hunding, who is nothing if he is not “traditional” – he cries for vengeance to Fricka – must let the stranger stay with them that night, but they will fight on the morrow. Sieglinde drugs her husband so that she and Siegmund might escape. Before she joins him, though – before he knows that she wants to join him – Siegmund is confronted with the sword left for him in the tree by Wotan. (So much for a “free hero,” although Siegmund knows nothing of this.) In the age-old tradition, none before could extract it, yet Siegmund can. The sexual metaphor, as Sieglinde joins him outside, is powerful if not subtle. They recognize each other at last as brother and sister, yet that is irrelevant.Footnote 33 She names her guest “Siegmund,” “Victorious,” a back-formation from her own name. Their love and identity are irrespective, as noted earlier, of kinship. “Du bist der Lenz,” (“You are the Spring”), Sieglinde tells her brother-lover, the final trace of ice from Rheingold- and Hunding-winters melting. The curtain falls just in time, to the most torrid, frenzied musical climax in the Ring and arguably in all of Wagner.Footnote 34

In the second act, then, both are outlaws, in flight from Hunding and society, though battle with the former and thus, implicitly, the latter will come. The “Annunciation of Death” scene, in which Brünnhilde, the “Valkyrie” of the opera’s Walküre title, visits Siegmund prior to battle, to take him to Valhalla proves crucial in her development towards humanity, for she sees something neither she nor Wotan could ever have anticipated. (There is freedom, after all, in Siegmund’s thoughts and acts; Wagner’s plot development is nothing if not dialectical.) When told that Sieglinde would not be permitted to accompany him, Siegmund refuses; he would choose hell over such immortality. That marks the highpoint of conscious atheist defiance in the Ring, for Siegfried will never find meaning in his deeds. This is Don Giovanni’s “No! No!” albeit in the name of true love and fidelity. Brünnhilde has been awakened to this humanity. Once Siegmund is dead, she braves her father’s wrath to ensure the temporary safety of Sieglinde that she might bear her brother’s son in the forest before she too dies.

Siegfried

Foretold musically and verbally in Die Walküre, we meet the young Siegfried in the opera bearing his name. In an intensification of his father’s charismatic origins, Siegfried has known neither father nor mother; he has never known another human, having been brought up by Mime in the forest, with only animals for companionship. What he has – all he will ever have, until his dying moments – is instinct. His strength and his weakness are his lack of reflection, his lack of consciousness of the meaning of his deeds. And so, when foes – Mime, Fafner, whoever – would frighten him, they cannot; he is the boy without fear, a fairytale figure transplanted into the politically malevolent world of the Ring.

Wagner depicts the hero – fully intended to be the hero of the Ring, prior to Wotan’s usurpation of that role – unsparingly. This, again, is no Rousseauvian noble savage, but a critique, at least partly intentional, of such a notion. If Siegfried finds his foster-father Mime unbearable, through “heroic” instinct rather than reason, it is not – not until tasting Fafner’s blood and speaking to the Woodbird afford him a little understanding – because he knows of Mime’s plotting; it is because he despises a figure less “heroic” than himself. And so, we find it difficult, perhaps impossible, to sympathize with Siegfried. Fafner and Mime may deserve their deaths at his hands, but there is something chilling to his dispatch of them with his father’s sword Notung. That, far from incidentally, proved to be a shattered sword only Siegfried could reforge: courtesy of a brute strength – perhaps a “natural” art too – entirely foreign to Mime.

It is with that revolutionary – or at least rebellious – sword that Wotan’s spear is shattered, the impatient boy, anxious to make his way to Brünnhilde’s rock, again not understanding the consequences of his deed. He simply finds a tedious old man blocking his way and acts accordingly. Discovery that this old man had been his father’s apparent foe makes things worse, but again Siegfried never understands what that entails. Does Siegfried commemorate what many on the Left would see as the bourgeois failing of elevating rebellion over thoroughgoing revolution more truly than Wagner himself realized? Many of Wagner’s critics on the Left, Adorno for instance, would argue very much so.Footnote 35 Whatever the truth of that, Siegfried unquestionably learns something important upon passing through the fire no other would dare approach to reach Brünnhilde, his sleeping beauty. In a startling psychoanalytical sequence – fairy tales are like this – he learns first that this armored warrior is “no man,” then that the woman before him is not his mother. He finally learns fear of a sort through sexual anticipation and fulfillment.

Alas, once again he never really learns the meaning of “love,” and thus, upon leaving the rock, readily falls prey to the machinations of Hagen and his Gibichung half-siblings. Gutrune’s potion of forgetfulness – which he readily drinks, instantly transferring his affections to a woman whose name he does not yet even know – is essentially a metaphor both for human corruption and wiles against which fearless Siegfried will ever stand defenseless, and for the readiness with which a “rebel without a consciousness” will, by dint of that very lack of consciousness, betray the one he loves or has loved.Footnote 36 He has “forgotten” Brünnhilde when he returns to her rock to win her for Gunther; he has no compunction in sexually assaulting her to humiliate her and to break her spirit. Again, he seems not even to realize what he has done. And so, a web of lies and betrayal, as planned by Hagen, has been spun that will lead to his downfall. Brünnhilde herself will betray Siegfried in turn, enabling Hagen to stab Siegfried in the only place her runes do not protect him: his back, since she knew he would never back away from an enemy.

In the Funeral March, we hear what is essentially an “ideal” version of this hero and of heroism more broadly. We hear Siegfried’s motivic and dramatic genealogy from his parents onwards. However, we also hear the hopes invested in him, the nobility of what might have been, just as, at the last, Siegfried finally achieves some level of conscious understanding that he had loved Brünnhilde all along. It is too late, save as a memorial, yet that has dramatic and even political significance. A hero who held revolutionary potential or, to the more skeptical, had at least been believed to have done so, has been deconstructed. Siegfried’s memory, infinitely more glorious than his actual, human reality, will serve as an example, a revolutionary memorial, perhaps even an incitement to future revolutionary deeds by us as heirs to those closing “men and women moved to the very depths of their being.” Wagner wrote that, in the Ring, he wanted to “make clear to the men of the Revolution the meaning of that Revolution, in its noblest sense.”Footnote 37 Here, at last, in tragic, Hegelian retrospect, he does, penning a response to his own programmatic explanation of Beethoven’s Eroica Funeral March:

the term “heroic” must be taken in the widest sense, and not simply as relating to a military hero. If we understand “hero” to mean, above all, the whole, complete man, in possession of all purely human feelings – love, pain, and strength – at their richest and most intense, we shall comprehend the correct object, as conveyed to us by the artist in the speaking, moving tones of his work. The artistic space of this work is occupied by … feelings of a strong, fully formed individuality, to which nothing human is strange, and which contains within itself everything that is truly human.Footnote 38

And note that we shall hear Siegfried’s motif once again: another reminder of what might have been, what still yet might be, at the close of the Immolation Scene, immediately preceding the final phrase of the Ring. There is mileage, it seems, remaining in the idea and the ideal of revolutionary heroism, of bringing down with Feuerbach those human qualities from gods to men. That holds even if it did not work as we had hoped on any particular occasion, historical, dramatic, or both.

Example 7.8 Götterdämmerung, closing phrase

Mime

We meet Mime in Das Rheingold and in Siegfried. He is first the skilled smithy enslaved by his brother Nibelung, Alberich, that kin relationship an exaggeration and condensation of sources on Wagner’s part. Mime forges the Tarnhelm only to be oppressed and beaten (physically and economically) further by him. It is from Mime, speaking to the visitors Loge and Wotan, that we learn in lyrical, Schubertian reminiscence of an older, preindustrial Nibelheim, prior to Alberich’s monstrous, capitalist conversion of it into something equivalent to the hell of a modern factory. Here, Mime seems sympathetic, eliciting our sympathy for the underdog. As mentioned above, he often does even in his dealings with Siegfried – partly because Siegfried often seems so unsympathetic. And yet, we learn that Mime has only brought up the troublesome boy because he thinks Siegfried might win Fafner’s hoard for him. Partly through his miserable existence, partly on account of that power-lust he shares with others, Mime too would do anything to win the Ring and its (apparently) measureless might. When Siegfried, having tasted Fafner’s blood, can hear Mime’s true thoughts – as opposed to his wheedling flattery – the hero swiftly finishes him off, to dark laughter from Alberich, observing from afar.Footnote 39

Hagen

In Götterdämmerung, Alberich still hopes to win back the Ring, through the “tenacious hate” of his son, Hagen, sired expressly, lovelessly, to that end. Love foresworn, force remained. Wotan’s creation of the Volsungs through a mortal woman, to keep him safe from Alberich is mirrored in Alberich’s creation of Hagen, as Alberich reminds him, to keep his father safe from heroes. The contrast by now lies in Wotan having (more or less) given up hope and thus having reached some sort of peace with himself and the world, whereas Alberich remains as eaten up with fear, anxiety, and power-lust – are they not the same? – as ever. Hagen has his own agency, his own intelligence, his own consciousness: an anti-Siegfried, perhaps, whose loyalty his father clearly fears, for Alberich continually urges him, “Be true! Be true!” Wotan necessarily failed in creating a “free hero”; Alberich fears his antihero may prove too free.

Hagen scores against Siegfried in cunning and created malevolence, his dark bass (like Alberich’s) a typically “operatic” – Siegfrieds Tod having been planned first, as a single drama – contrast to the Heldentenor of Siegfried (and his father). If any Ring character speaks of and with evil and with a strength that is not merely “natural,” a strength at which he must work, it is Hagen. If Wotan’s presence is heard throughout the score of Götterdämmerung, so too is Hagen’s, a persistent presence, both violent and corrosive. Listen to the oath of blood brotherhood between Siegfried and Gunther, and Hagen’s motif reminds us whose work this – literally – fatal oath is.

Example 7.9 Hagen motif

Hagen ensnares Siegfried, Gunther, Gutrune, the Gibichung vassals and their womenfolk, even Brünnhilde, in his plot to win the Ring – and comes very close to succeeding. He slays Siegfried, avenging the perjury that he, Hagen, has engineered. Hagen dies, however, at the potential moment of victory, majestically tossed aside by Brünnhilde. His final words, the last of the Ring, are splendidly ambiguous: “Stay away from the Ring!” (Zurück vom Ring!) Is it, as the Rhine waters overcome him, that he would still possess it; or are those words a warning, recognition of what destroyed his life and others’? In this tragic catharsis, one does not preclude the other.

The Gibichungs: Gunther and Gutrune

Gunther and Gutrune were born to Hagen’s mother, Grimhild, but not to Alberich. They are, rather, legitimate heirs to Gibich, Gunther now ruling over his father’s realm. Their vanity preoccupies them with honor, line, recognition, and royal status. Hagen manipulates that, promising consorts their status would merit, consorts they would yet never win for themselves: Siegfried and Brünnhilde. Moreover, for Gunther, to have the effortlessly heroic Siegfried as his blood brother would further bolster his authority. Brünnhilde views them both only with scorn, Gunther no match for her, Gutrune a mere Mannesgemahl (paramour) to Siegfried. There is something of the old-fashioned world of chivalry, of Lohengrin, to Gunther’s music, while Gutrune’s, tellingly, pays reference to Auber’s La muette de Portici, a representative of the French opera Wagner likened to a “coquette” (Opera and Drama).Footnote 40

The Valkyries

I left the Valkyries, above all Brünnhilde, to last, since the final scene is essentially – with any number of qualifications – hers. The Valkyries – Helmwige, Gerhilde, Ortlinde, Waltraute, Siegrune, Rossweisse, Grimgerde, and Schwertleite, and Brünnhilde – are daughters of Wotan and Erda. They are body-snatchers, collecting fallen heroes to have them form part of Wotan’s Valhalla host. Brünnhilde was always Wotan’s favorite; she is the Walküre of the opera’s title. She describes herself as “Wotan’s will,” and will on that very ground excuse her disobedience in having attempted to save Siegmund. In a sense, that is true: She does what he would have wished to. However, it is in explicit disobedience of his stated orders and in her consequent punishment that she attains selfhood and, crucially, humanity. That marks, on balance, an ascent from her previous state of divinity. Seeing and reflecting on Siegmund’s love for Sieglinde is the agent of Brünnhilde’s transformation. When Siegfried awakens her, in a variation upon the Sleeping Beauty tale, she becomes human. That is traumatic, at first, as indeed would be any waking from a deep sleep, but she too comes to love Siegfried as his parents had loved one another.

Brünnhilde’s tragedy is that she, more conscious of her humanity than Siegfried, believes in their love far more strongly. She takes the Ring, in a cruel irony, as a ring of marriage. Thus, when her sister, Waltraute visits her rock, Brünnhilde will not give it up; she would never do so, no matter how dire the need of her sisters, her father, the gods, even the world. This Götterdämmerung scene between the two sisters, one still divine, one now human, is almost a cantata in itself. It proves so moving because neither can understand the other. To Waltraute, desperately attempting to do good, attempting to avert the end of the world, Brünnhilde is unconscionably selfish; to Brünnhilde, the gods are a loveless old order, who betrayed and shunned her. They will still not accept the coming of a new order, based, after Feuerbach, on love: what Wagner sometimes referred to as “communism.”Footnote 41 Her subjugation and rape by one who had “loved” her, to win her for his new blood brother, are effected by a steely orchestral violence that speaks of terror and sheer barbarism. No wonder that Brünnhilde, cowed yet never broken, wishes vengeance upon Siegfried and that she, in the post-Meyerbeerian trio at the end of the second act, joins with Gunther and Hagen to seal Siegfried’s fate.

Only at the end, after his death, does Brünnhilde come to understand what has happened, not only to Siegfried, but to the whole world. She may not think herself “wise,” but she is. In a striking, Schopenhauerian anticipation of Parsifal, she has been “enlightened through compassion.” Wagner’s “Schopenhauer” ending to the Ring only fulfills what his composition has told us throughout the Immolation Scene. Those who would treat the “drama” as only words, and would thus say that Wagner had not even read Schopenhauer when writing the Ring poem, could not be further away from understanding him, his method, his dramas, and their meaning(s). When Brünnhilde offers a benediction to Wotan, bidding the god to rest in peace, to the tender sounds of what Valhalla might have been, she helps draw the sting of Alberich’s curse. Definitively naming the final motif of Götterdämmerung is a fool’s errand; by this stage, all motifs have developed, have acquired multiple, contested meanings. Nevertheless, Wagner’s own rare naming of that closing melody – heard previously in Sieglinde’s Walküre annunciation of Siegfried – as the “glorification of Brünnhilde” has much to be said for it.Footnote 42 Such naming, however, like the close of the drama itself, marks the beginning rather than the end of discussion. A world may have ended, not without “glorification”; another, to be informed and interpreted by what is past, has just begun. Or, to quote one of Wagner’s most distinguished interpreters, Pierre Boulez, while at work on that “Centenary” Ring:

There have been endless discussions as to whether this conclusion is pessimistic or optimistic; but is that really the question? Or at any rate can the question be put in such simple terms? Chéreau has called it “oracular”, and it is a good description. In the ancient world, oracles were always ambiguously phrased so that their deeper meaning could be understood only after the event, which, as it were, provided a semantic analysis of the oracle’s statement. Wagner refuses any conclusion as such, simply leaving us with the premises for a conclusion that remains shifting and indeterminate in meaning.Footnote 43

You often hear it said, or suggested, that politics and the arts, including of course music, inhabit totally separate worlds and that attempts to bring the two together are at best misguided, if not positively misleading.

Such a belief, however fervently held, is nevertheless only tenable, if actual history is ignored, or if you cling to the idea that music, or the arts in general, are able to somehow transcend history, stripped of all their context. Of course, the notion of transcendence has some viability. How else could we respond to the 200-year old music of Beethoven, or the 400-year old music of Monteverdi? But just as there are limits to your appreciation and understanding of a Beethoven sonata or symphony if you know nothing of sonata form or symphonic structure, so there are also limits to your understanding if you choose to ignore the historical, political, and cultural context in which they were composed.

The need for contextual understanding applies particularly strongly to opera. Any performance of opera is very much a public event, with potential social or political significance and even consequences. Opera consists of words as well as music, and those words may have a political dimension or may be perceived to have one regardless of what the composer intended. But, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, much opera has been given an explicit and deliberate political dimension. This is true of works by Giuseppe Verdi, Bedřich Smetana, Modest Mussorgsky, and Sergei Prokofiev as well as Kurt Weill, Michael Tippett, and John Adams. The question for us is, Is this also true of Richard Wagner, Verdi’s exact contemporary and the other supremely great opera composer of that age?

There is, or should be, no question that Wagner as a person was always a highly politically conscious being. I say should be, because this assertion, like almost any statement about Wagner, is still subject to dispute. It is accepted, for example, that Wagner was involved in the revolutionary turmoil that swept across Europe in 1848–9, and particularly in the uprising in Dresden of 1849. It was for this that he was exiled from Germany for eleven years. Yet one author tells us that “the revolutionary acts which led to his exile were only marginally political,”Footnote 1 while one biographer asserts that “in spite of his activities in the field, politics as such hardly impinged at all on his inner life.”Footnote 2

Similarly, it is generally recognized that Wagner was obsessively and virulently anti-Semitic. Yet this same biographer claims, in relation to Jewishness in Music, written in 1850, that for Wagner, “though otherwise not hostile to Jews … the real object of his attack was Meyerbeer and no one else.”Footnote 3 And another well-known writer on opera, Peter Conrad, has claimed that “Wagner’s remarks (about Jews) were mostly tasteless jokes, and there seems to me to be an abysmal gap between a grumpy jest and a campaign of genocide.”Footnote 4

But, leaving aside the defense of the indefensible, the real question is why anyone should seek to downplay Wagner’s concerns with politics. Wagner’s ambitions as a composer of what he preferred to think of as music drama rather than opera were bound up with his political hopes. Broadly speaking, he took a low view of mid nineteenth-century opera and in particular of its position and function in contemporary culture. Opera should not be superficial entertainment for the rich and privileged. It should be a far more serious and thoughtful experience, and it should occupy a central position in a more open and popular culture. His ideal for Bayreuth, which was never realized, was that it should be free, and so open to all.Footnote 5

Wagner was a political being, but what was his political position or philosophy? Unlike with, say, Verdi, this is a difficult question to answer with any assurance or even clarity. Wagner was born in Leipzig in 1813, at a time when the city was engulfed in Napoleon’s Central European War. When still a teenager and a student there, he felt the impact of the European revolutions and uprisings of 1830–1, and in particular of Polish refugees who fled to the city after their nationalist uprising was put down by Czarist Russia. He composed a “Political Overture” which was lost.Footnote 6 He got involved with the Young Germany movement, a campaign of intellectuals for republican and democratic principles, and got valuable support from the writer and journalist, Heinrich Laube. Laube was imprisoned in 1834 for his political activities. Rienzi, composed between 1838 and 1840, reflects to a degree Wagner’s political outlook at this time.

We have already mentioned his involvement in the unrest of 1848 and the Dresden uprising of May 1849. Contrary to what he suggested in later years, his involvement was far from peripheral. In Mein Leben, Wagner’s autobiography written at the request of King Ludwig II of Bavaria, this dichotomy is at work, where Wagner places himself “always in the thick of things,” but remains careful not to appear “anti-monarchist in the eyes of his new royal patron.” The extent of Wagner’s revolutionary activities is thus intentionally vague, but it is undeniable that he aligned himself with the revolutionary forces and was in “close contact with several of their leading lights.”Footnote 7 He took over the editorship of the subversive magazine, Volksblätter, from his radical musical colleague, August Röckel, and contributed inflammatory articles himself. He had leaflets printed urging Saxon soldiers to support the uprising, and he may have tried to get hand grenades manufactured. He held political meetings in his own garden. Through Röckel, he met the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, who came to Dresden to take part in the uprising, and they found much to discuss and debate.

In the end, Wagner fled Dresden and, with help from Franz Liszt among others, escaped to Switzerland. He stayed away from Germany in self-imposed exile for eleven years in order to evade an active arrest warrant. Bakunin and Röckel were not so lucky. Both were arrested, imprisoned, and sentenced to death, later commuted to life imprisonment.

This, then, was the period of Wagner’s involvement in radical politics. But it was also the period in which the plan of the Ring began to take shape, and in late 1848 he wrote the first version of the text of a drama he called Siegfrieds Tod, which eventually became Götterdämmerung. And it was only a year after the Dresden uprising that he published his first major attack on the Jews, Das Judentum in der Musik. When Liszt wrote to him about this article, Wagner told him “I harbored a long suppressed resentment against this Jewish business, and this resentment is as necessary to my nature as gall is to the blood.”Footnote 8 In this essay, he mocked those who argued for the emancipation of the Jews: “in reality it is we who require to fight for emancipation from the Jews. As the world is constituted today, the Jew is more than emancipated, he is the ruler. And he will continue to rule as long as money remains the power to which all our activities are subjugated.”Footnote 9

There is a conventional pattern whereby young radicals gradually mutate into crusty conservatives or even militant reactionaries, and Wagner does conform to this pattern in some respects. His anti-Semitism, already evident in the 1840s, became more virulent and obsessive in later years and was tied into a broader concern with racial purity, which was reinforced by his friendship with Count Joseph-Arthur de Gobineau and his reading of Gobineau’s Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races. His German nationalism assumed a more aggressive form: he was an enthusiastic supporter of Prussia’s war against France in 1870–1, which chimed with his longstanding and assiduously nourished hostility to all things French that had its roots in his unhappy and unsuccessful time in Paris in 1839–42. In 1871, he composed the Kaisermarsch to celebrate the German victory. But both anti-Semitism and German unification or patriotism had long been features of his political outlook, while even in his years of fame and success he still cherished dreams of a world somehow cleansed of traditional privilege and the “underlying curse of capital.”Footnote 10

How far are Wagner’s political views and experiences reflected or embodied in his operas, and most particularly in Der Ring des Nibelungen? We have already noted Wagner’s low opinion of much contemporary opera. In 1845, quite early in his composing career, he wrote to Louis Spohr, “in my own view, almost every aspect of operatic life in present-day Germany suffers from this distasteful striving after superficial success.”Footnote 11 The logical corollary of this was that Wagner saw it as his mission “to raise up opera to a higher plane & restore it to a level from which we ourselves have debased it by expecting composers to derive their inspiration from trivialities, intrigues & so on.”Footnote 12 But it was not until he had put the compromises with existing grand opera represented by Tannhäuser and Lohengrin behind him that he was really free to embark on the vast project that he believed would “raise up opera to a higher plane.” This Gesamtkunstwerk, a unification of artistic ideals, was a conception Wagner had previously touched upon in two essays of 1849 on the role of art and more specifically, opera, in society. And this grand project was what would eventually become Der Ring des Nibelungen.

He never had any doubts about the historical and philosophical significance of this project. While he was still drafting its text, he wrote to his musical colleague and friend Theodor Uhlig, “I am again more than ever moved by the comprehensive grandeur and beauty of my subject: my entire philosophy of life has found its most perfect artistic expression here.”Footnote 13 Given the scale of the project – four separate music dramas totaling more than fourteen hours of music – and the seriousness of the composer’s plans for it, it would be extraordinary if it did not express and embody at least some of Wagner’s most fundamental and far-reaching perspectives upon life itself and the nature and purpose of human society. Indeed, when he had completed the text of the Ring in 1853, he wrote to Liszt in a moment of exultation, “mark well my new poem – it contains the world’s beginning and its end!”Footnote 14

I do not think it is fanciful to hear in the vast sustained opening of Das Rheingold an evocation of the pure, unsullied waters of the Rhine, but, more than that, an evocation of the beginning of the world, with its simple E♭ arpeggios conveying the harmony of the natural world before it is disturbed by human or quasi-human activity. So too the overwhelming end of Götterdämmerung announces the end of one failed epoch in world history together with the prospect, in musical terms at least, of a better future.

The myth, which provides the central narrative of the cycle, is indeed one of global significance. The rule of the gods, led by Wotan, which we see in its delusive splendor at the close of Das Rheingold, is doomed because of its own corruption, greed, and brutality. It is destined to be replaced by a world in which free, loving, and heroic human beings hold sway, yet live in harmony with the natural world, which has been vandalized by the gods and other nonhuman inhabitants of Das Rheingold. Siegfried and Brünnhilde, stripped of her divinity by Wotan, are the first representatives of this new human order. Thus, to an extent, the Ring embodies Wagner’s utopian hopes for the human future, as Wagner himself acknowledged: “my Nibelung poem … had taken shape at a time when … I had constructed a Hellenistically optimistic world for myself which I held to be entirely realizable if only people wished it to exist, while at the same time seeking somewhat ingeniously to get round the problem of why they did not in fact wish it to exist.”Footnote 15

But, having said that, we are immediately faced with one of the paradoxes, if not contradictions, in Wagner’s plan, for the new order begins in tragedy, and the tragedy is one of betrayal. Siegfried is tricked or drugged into abandoning Brünnhilde in favor of Gutrune, while Brünnhilde takes her revenge by betraying Siegfried to Hagen. It is a bleak start to the new human order, and since Wagner began work on the Ring with the text then called Siegfrieds Tod, it is clear that this sordid tragedy was always at the heart of the whole project.

It was equally clear to Wagner, however, that the old prehuman order of gods, giants and dwarfs had to go, and one reason for this was that he equated that mythical prehuman society with the society he saw around him in nineteenth-century Europe, which he so despised and wished to see replaced. One of the first people to grasp this was George Bernard Shaw. In The Perfect Wagnerite, first published in 1898, he wrote, “The Ring … is a drama of today, and not of a remote and fabulous antiquity. It could not have been written before the second half of the nineteenth century, because it deals with events which were only then consummating themselves.”Footnote 16

Deryck Cooke, in his important but alas incomplete study of the Ring, suggested that some people are actually put off the cycle because they find the gods, giants, and dwarfs “frankly ridiculous.”Footnote 17 But Shaw had anticipated this reaction too. Reviewing what sounds to have been a poor performance of Das Rheingold in London in 1892, he observed that “Das Rheingold is either a profound allegory or a puerile fairy tale.”Footnote 18 It is, of course, the former, and Shaw went on to explore and explain it in The Perfect Wagnerite.

Das Rheingold

The essence of Das Rheingold is a ruthless struggle for power, and for a very particular and topical kind of power – the ability to create wealth and thereby dominate the world. That power is embodied in the Ring Alberich has had made out of the gold which, in the opening scene, he has stolen from the Rhine and the Rhinemaidens. One of the Rhinemaidens, Wellgunde, had foolishly told Alberich about the potential power of the gold; but then her sisters agree that, since the essential condition of obtaining that power is a renunciation of love, there is no danger of the lustful dwarf meeting that requirement. They are wrong. Alberich chooses power and curses love. He seizes the gold and makes off with it. Immediately, the Rhine goes dark.

Whether this is represented in the staging or not, it is important that we, the listeners and spectators, understand the significance of what has happened. The theft of the gold is a crime against Nature, a violation of the natural order. As Shaw wrote, the Rhinemaidens value the gold “in an entirely uncommercial way, for its bodily beauty and splendor.”Footnote 19 But Alberich sees nothing of that. For him it is only a source of wealth and power. He takes the kind of crude utilitarian approach to nature which Dickens satirized in his exactly contemporary novel, Hard Times (1854).

This is not the only violation of nature that has taken place in this old-established society. Wotan’s spear, we learn eventually from the Norns at the opening of Götterdämmerung, was created by tearing a branch from the World Ash Tree – an act that eventually killed the tree and the wisdom of which it was the source. As Mark Berry has noted, “this rape of nature appears to be purely Wagner’s invention, with no warrant in his mythological sources.”Footnote 20

As will later be seen, the obverse of these spoliations of nature is Siegfried’s exceptional rapport with the natural world. It is one striking indication of Wagner’s intuitive genius, as well as his intellectual receptiveness, that in the middle of the nineteenth century, with the Industrial Revolution in Europe in full swing, he should have made humanity’s relations with the natural world a central theme of his magnum opus.Footnote 21

Alberich’s renunciation of love in favor of power epitomizes what is wrong with the god-dominated social order of Das Rheingold. For his chief rival, Wotan, has made a similar choice. At the time when he decided to build Valhalla, the grandiose home of the gods, he was short of cash, so he offered the builder-giants his sister-in-law, Freia, instead. Bonds of relationship or affection count for little compared to his desire for glory. Fricka, his wife, rightly denounces him as a “cruel, heartless, unloving man” (Liebeloser, leidigster Mann). With the help of Loge, he resolves to pay off the giants with Alberich’s store of gold, which will be obtained “by theft,” as Loge bluntly puts it. But he and Alberich both understand – as the giants do not – that it is not existing wealth that matters but the power to go on producing it, a power that resides in the Ring. So when Alberich tries to keep the Ring while surrendering the wealth that has already been created by his army of slaves in Nibelheim, Wotan tears it off his finger. Were it not for the warning of Erda, the voice of far-sighted wisdom, he too would have held onto it and allowed the giants to make off with Freia after all. The gods then watch, horrified, as the two giants, Fafner and Fasolt, quarrel over the Ring, with Fafner striking his brother dead.