Introduction

Skilled reading is predicated on intact phonological processing, which describes an individual's awareness of sound structure within a spoken language (Melby-Lervåg, Lyster, & Hulme, Reference Melby-Lervåg, Lyster and Hulme2012; Stahl & Murray, Reference Stahl and Murray1994). Phonological processing is often measured by tests of the ability to blend or segment sounds or words, and to hold sound sequences in memory. Deficits in phonological processing are a core feature of reading disorder (RD; Lindsey, Manis, & Bailey, Reference Lindsey, Manis and Bailey2003; Vellutino, Fletcher, Snowling, & Scanlon, Reference Vellutino, Fletcher, Snowling and Scanlon2004; Vellutino, Scanlon, & Reid Lyon, Reference Vellutino, Scanlon and Reid Lyon2000) Further, training in phonological processing is associated with improved reading skill (Meyler, Keller, Cherkassky, Gabrieli, & Just, Reference Meyler, Keller, Cherkassky, Gabrieli and Just2008; Shaywitz et al., Reference Shaywitz, Shaywitz, Blachman, Pugh, Fulbright, Skudlarski, Mencl, Constable, Holahan, Marchione, Fletcher, Lyon and Gore2004; Yamada et al., Reference Yamada, Stevens, Dow, Harn, Chard and Neville2011) suggesting that deficits in phonological processing play a causal role in RD. Development of phonological processing skills appears to be under genetic control (Newbury, Monaco, & Paracchini, Reference Newbury, Monaco and Paracchini2014; Snowling & Melby-Lervag, Reference Snowling and Melby-Lervag2016) and is subserved by a functional reading circuit in the brain (Richlan, Reference Richlan2012). Consistent with this, children with RD often show genetic abnormalities (Raskind, Peter, Richards, Eckert, & Berninger, Reference Raskind, Peter, Richards, Eckert and Berninger2013), and altered functioning of the reading circuit (Koyama et al., Reference Koyama, Di Martino, Kelly, Jutagir, Sunshine, Schwartz, Castellanos and Milham2013; Richlan, Reference Richlan2012). Thus, phonological processing appears to represent a critical ability in the acquisition of reading skill.

Given the importance of the phonology of a language to reading, are children who speak a language at home that differs phonologically from the language of academic instruction (i.e., children living in language minority (LM) homes) at risk for problems in reading? In the US, one in five children are from such LM homes (Hoff, Reference Hoff2013), eighty percent of whom are Spanish–English speaking (August & Shanahan, Reference August and Shanahan2006; Samson & Lesaux, Reference Samson and Lesaux2015; Zehler et al., Reference Zehler, Fleischman, Hopstock, Stephenson, Pendzick and Sapru2003). Although bilingualism seems to confer considerable cognitive and linguistic advantages across a range of languages (Bialystok, Reference Bialystok2011; Eviatar & Ibrahim, Reference Eviatar and Ibrahim2000; Ibrahim, Eviatar, & Aharon-Peretz, Reference Ibrahim, Eviatar and Aharon-Peretz2007; Kang, Reference Kang2012; Marinova-Todd, Zhao, & Bernhardt, Reference Marinova-Todd, Zhao and Bernhardt2010), and is associated with improved word reading skills (Jasińska & Petitto, Reference Jasińska and Petitto2018), this may not always be the case, as advantages may be specific to properties of distinct languages. For example, in the US, children from LM homes enter school with reduced language proficiency and reading readiness skills in the language of academic instruction relative to their monolingual peers (Hoff, Reference Hoff2013). These delays in language proficiency are hard to interpret given that socioeconomic status (SES), a measure of education, income, and occupation that determines access to resources, is associated with LM status (Haskins, Greenberg, & Fremstad, Reference Haskins, Greenberg and Fremstad2004; Hoff, Reference Hoff2013) and with delays in language development and reading skill (Noble, McCandliss, & Farah, Reference Noble, McCandliss and Farah2007; Robins, Ghosh, Rosales, & Treiman, Reference Robins, Ghosh, Rosales and Treiman2014). Therefore, delays in language proficiency and reading readiness skills in children from LM homes may be driven by the effects of low SES in general or by more specific effects of bilingualism on language development. The current study attempts to disentangle the effects of home language environment from more general effects of lower SES on language outcomes by comparing phonological processing skills in children from LM and ED homes who are all from low SES backgrounds. Such information is critical to the development of educational practices and policy that will help to close the achievement gap between children from English-dominant homes and their peers from LM homes (Hoff, Reference Hoff2013; Wilkinson, Ortiz, Robertson, & Kushner, Reference Wilkinson, Ortiz, Robertson and Kushner2006).

Bilingualism is a highly complex construct that can have multiple effects on aspects of language development (Antovich & Graf Estes, Reference Antovich and Graf Estes2018; Hoff & Ribot, Reference Hoff and Ribot2017), including phonological processing, which can be broadly defined as oral language skills that emphasize processing of sounds (Peterson & Pennington, Reference Peterson and Pennington2015). Prior studies document bilingual advantages in phonological processing and in reading achievement in the language of instruction, specifically for children who are exposed to two languages from birth. However, children from LM homes are not typically exposed to two languages at birth. Regardless of age of exposure, studies document a bilingual advantage in phonological processing (Eviatar & Ibrahim, Reference Eviatar and Ibrahim2000; Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Eviatar and Aharon-Peretz2007; Kang, Reference Kang2012; Marinova-Todd et al., Reference Marinova-Todd, Zhao and Bernhardt2010). These studies were conducted with individuals speaking English – Greek, English – Korean, or English – Mandarin, or Arabic – Hebrew. Differences between language systems, such as alphabetic versus logographic/morpho-syllabic languages or transparent versus opaque orthographies, affect how bilingualism influences language development (Barac, Bialystok, Castro, & Sanchez, Reference Barac, Bialystok, Castro and Sanchez2014; Bialystok, Majumder, & Martin, Reference Bialystok, Majumder and Martin2003; D'Angiulli, Siegel, & Serra, Reference D'Angiulli, Siegel and Serra2001; Loizou & Stuart, Reference Loizou and Stuart2003). Findings from studies that compare languages with different alphabets, or alphabetic versus logographic languages, may not generalize to studies examining Spanish–English bilingualism, as these languages share an alphabetic system. Further, these prior studies were conducted with individuals from undisclosed SES backgrounds or from middle-to-high SES backgrounds (Eviatar & Ibrahim, Reference Eviatar and Ibrahim2000; Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Eviatar and Aharon-Peretz2007; Kang, Reference Kang2012; Marinova-Todd et al., Reference Marinova-Todd, Zhao and Bernhardt2010). Last, relative transparency versus opacity of the first versus second language acquired may also impact the advent of a bilingual advantage (Loizou & Stuart, Reference Loizou and Stuart2003). Thus, documented bilingual advantages in phonological processes and reading may not generalize to Spanish–English speaking children from low SES backgrounds, such as those in our study.

Prior studies investigating the bilingual advantage on phonological processing in Spanish–English speaking children from low SES backgrounds have yielded equivocal results. Preschool and kindergarten children from LM homes showed weaker language and phonological awareness skills in the language of instruction relative to their English-only (monolingual) peers (Brice & Brice, Reference Brice and Brice2009; Hammer & Miccio, Reference Hammer and Miccio2006; Hammer, Miccio, & Wagstaff, Reference Hammer, Miccio and Wagstaff2003; Lonigan, Farver, Nakamoto, & Eppe, Reference Lonigan, Farver, Nakamoto and Eppe2013; Páez, Tabors, & López, Reference Páez, Tabors and López2007). In contrast, relative to their monolingual peers, young children from LM homes made greater gains in some phonological skills in the language of instruction over the course of the school year (Hammer & Miccio, Reference Hammer and Miccio2006; Lonigan et al., Reference Lonigan, Farver, Nakamoto and Eppe2013). Older elementary and high school students from LM homes demonstrated stronger phonemic decoding and segmentation skills in the language of instruction than their English-only (monolingual) peers (Bialystok, Luk, & Kwan, Reference Bialystok, Luk and Kwan2005; Bialystok et al., Reference Bialystok, Majumder and Martin2003; Krizman, Skoe, & Kraus, Reference Krizman, Skoe and Kraus2016). Thus, it remains unclear to what extent LM status affects phonological processing in the language of instruction in Spanish–English speaking children from low SES backgrounds.

Even less is known about associations between LM status and phonological processing in the language of instruction among children with reading problems. In one study, kindergarten children from LM homes showed a bilingual disadvantage in phoneme identification relative to their monolingual (ED) peers in the language of instruction, regardless of reading skill level (Brice & Brice, Reference Brice and Brice2009). In contrast, sixth-grade children from LM homes with reading problems showed reduced morphological awareness (integrating phonological and orthographic information) in the language of instruction compared to monolinguals, but there were no differences in phonological processing among those without reading problems (Kieffer, Reference Kieffer2014). More research with larger samples of children is needed to fully understand the effects of LM status on language processes and language-based achievement skills in the language of instruction in Spanish–English speaking children who comprise a majority of English language learners in US schools.

The current study was designed to address these issues. In this cross-sectional study we evaluate the performance of 352 children from LM or ED homes with or without reading impairment who were seen in a clinic for low-income children with suspected learning problems. We examined whether phonological processing problems in the language of instruction would be magnified when predicting a reading disorder diagnosis in children from LM versus ED homes. We also examined whether there was a phonological processing advantage or disadvantage in the language of instruction for children from LM homes who did not have diagnosed reading problems. We were unable to hypothesize a particular direction of effects given equivocal findings in prior studies (Bialystok, Luk, & Kwan, Reference Bialystok, Luk and Kwan2005; Bialystok et al., Reference Bialystok, Majumder and Martin2003; Brice & Brice, Reference Brice and Brice2009; Krizman, Skoe, & Kraus, Reference Krizman, Skoe and Kraus2016).

Methods

Sample

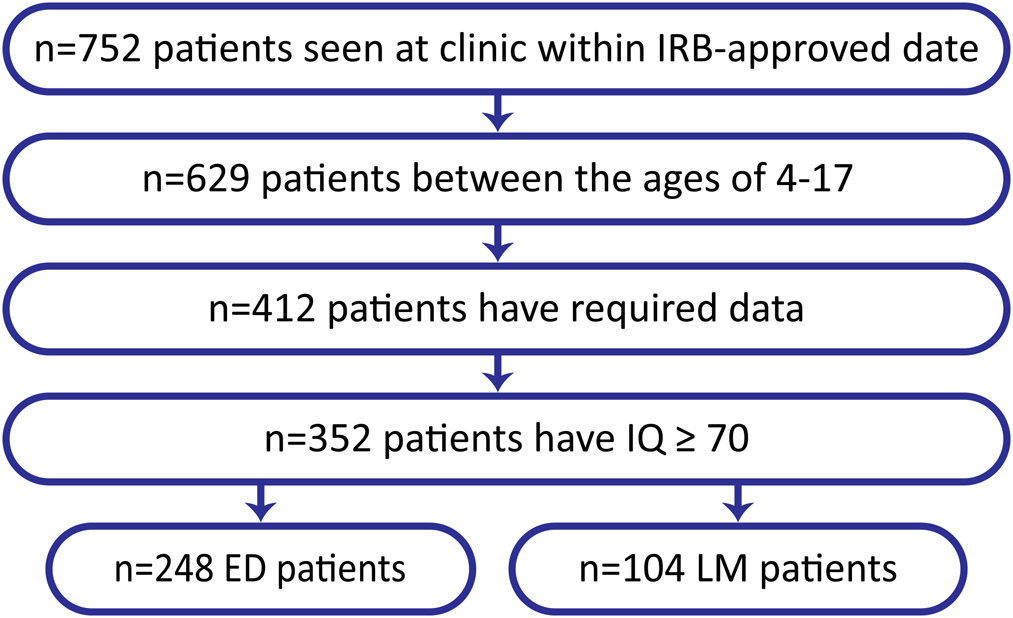

The sample was selected from a database of 752 children who were evaluated at an outpatient clinic for children with suspected learning problems from low-income backgrounds between 2011 and 2016 (see ‘Supplementary materials’ for more information, available at <https://doi.10.1017/S0305000919000576>). All Spanish–English or English dominant participants between four and seventeen years old with available phonological memory and awareness test data and IQ (Full Scale, General Ability, or Perceptual/Fluid Reasoning index) greater than or equal to 70 were selected, yielding 352 participants (248 ED and 104 LM, Figure 1). Eligibility for the clinic requires income at or less than 250% of the the federal poverty limit; for a family of four in New York City this translates to $60,625 in 2019. The median annual household income of the sample was $25,000 and 76 percent of mothers had less than a bachelor's degree. All demographic information (age, sex, race, ethnicity, maternal employment status, family income, current grade in school) was gathered from a standard survey used in the clinic (see ‘Supplementary materials'). Neuropsychological functioning (IQ) and presence of DSM-5 disorders known to be associated with RD (Language Disorder, Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), number of ADHD symptoms) were captured from de-identified assessment records (see ‘Supplementary materials’). The Institutional Review Board at the University approved this study.

Figure 1. Flowchart depicting the sample selection strategy. This figure depicts the steps taken to select the sample of children included in the analyses. ED = English dominant; LM = Language minority.

Language status

To reflect the heterogeneity of children's language exposure in the home, children are described as LM or ED rather than as bilingual or monolingual (Serratrice & De Cat, Reference Serratrice and De Cat2019). Current education and research practices classify children as LM or ED on the basis of parent report of the language(s) spoken at home (Brice & Brice Reference Brice and Brice2009; Carroll & Bailey, Reference Carroll and Bailey2015; Jasińska & Petitto, Reference Jasińska and Petitto2018). Consistent with this practice, in the current study, parent report of language spoken at home was used to form the ED and LM groups. Home language information was gathered as part of a general demographic survey included in the assessment (see ‘Supplementary materials’). Those who reported speaking ‘English Only’ or ‘Mostly English, Some Spanish’ were placed in the ED group (n = 248) and those who reported speaking ‘Spanish Only’ or ‘Mostly Spanish, Some English’ were placed in the LM group (n = 104; Figure S1). In addition, when commencing services at the clinic all parents were asked about their language preference. Those who preferred Spanish were provided with an interpreter in order to communicate with the clinic psychologists and staff. Across all families, the language reported to be spoken at home and the language used at the clinic including during the psychosocial interview were highly associated (Χ 2(5) = 333.46, p < .0001). For children whose parents reported a bilingual home environment (‘equal use’ of English and Spanish), the parent's preferred language (used at the clinic throughout the visits and at school meetings, see ‘Supplementary materials’) was used to determine language minority status (LM n = 23; ED, n = 11). Fifteen families selected ‘Other’ for the language spoken at home and were thus not included in the study.

RD diagnostic status

Current theoretical models of reading disorder identify subtypes of children with delays or deficits in word reading accuracy, reading rate or fluency, or reading comprehension (Duff & Clarke, Reference Duff and Clarke2011). Children evaluated in the clinic were assessed through multiple methods consistent with best clinical practices (Alfonso & Flanagan, Reference Alfonso and Flanagan2018). In addition to acquiring individual neuropsychological and achievement test data administered in the language of instruction (English), parent and teacher reports as well as record reviews and clinical interviews were obtained. Participants were included in the RD group if they received a diagnosis of Reading Disorder as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) IV-TR (APA, 2000) or Specific Learning Disorder, with impairment in reading as defined in DSM-5 (APA, 2013). Diagnoses were based on the presence of below average performance on measures of single word reading skills, oral reading, and/or reading comprehension; both groups may have received a range of other diagnoses as determined through the comprehensive neuropsychological assessment completed at the clinic (Figure S2). Ninety-seven percent of participants in the RD group placed in the bottom quartile for word reading (GORT 5 Accuracy or KTEA Letter and Word Identification subtests), indicating problems at the word reading level. Participants were included in the non-RD group if they did not receive a diagnosis of Reading Disorder or specific learning disorder, with impairment in reading.

Measures

Phonological Processing was measured with the phonological awareness and phonological memory indices of the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (CTOPP; Wagner, Torgeson, & Rashotte, Reference Wagner, Torgeson and Rashotte1999; Wagner, Torgeson, Rashotte, & Pearson, Reference Wagner, Torgeson, Rashotte and Pearson2013). This test yields standard scores with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15 for each index of ability and a mean of ten and a standard deviation of three for each subtest. These measures have good reported reliability (all Cronbach's alpha > 0.80; Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Torgeson, Rashotte and Pearson2013). Because this is a clinic sample, children were administered current editions of measures of phonological processing (awareness and memory) depending on the date they were seen in the clinic. In order to use all available data (CTOPP, n = 127 and CTOPP-2, n = 223), standardized rather than raw scores were analyzed. This allowed for comparison across measures and the wide age range included in the study sample.

The Phonological Awareness Index (PAI) of the CTOPP measures awareness of and access to the sound structure in oral language. The index includes three subtests for children aged four to six (Elision, Blending Words, and Sound Matching) and three subtests for children/young adults aged seven to twenty-four (Elision, Blending Words, and Phoneme Isolation).

The Phonological Memory Index (PMI) measures temporary storage of phonological information in short-term or working memory. The index includes the Memory for Digits and Nonword Repetition subtests for use with all ages.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms were assessed with the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham-IV (SNAP-IV) – Parent & Teacher Rating Scale (Swanson, Reference Swanson1995), measuring Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity as defined in the DSM-5 (APA, 2000).

Analytic plan

T-tests or chi-square examined whether children from ED and LM homes differed in relevant demographic factors including age, sex, race, ethnicity, maternal employment status, grade, IQ, Language Disorder diagnosis, ADHD symptoms, or ADHD diagnosis. P-plots evaluated whether PAI and PMI standard scores were normally distributed in the ED and LM groups. Two separate logistic regression models evaluated whether standard scores on phonological processing (PAI or PMI), language status (LM or ED), and their interaction predicted the presence of RD, controlling for age, sex, ADHD diagnosis, maternal employment, and ethnicity, which was included to control for differences between ED and LM groups. Significant effects were further corrected for testing across two measures of phonological processing (phonological awareness or phonological memory; Bonferroni correction, p < .05/2). Significant language status-by-phonological processing (phonological awareness or phonological memory) interactions were explored to assess which subtests that composed each index score (PAI or PMI) contributed to the interaction effect. Among children without RD, ANCOVA explored whether phonological processing (phonological awareness or phonological memory) varied between children from ED and LM homes, controlling for age, sex, maternal employment, and ethnicity.

Results

Participants

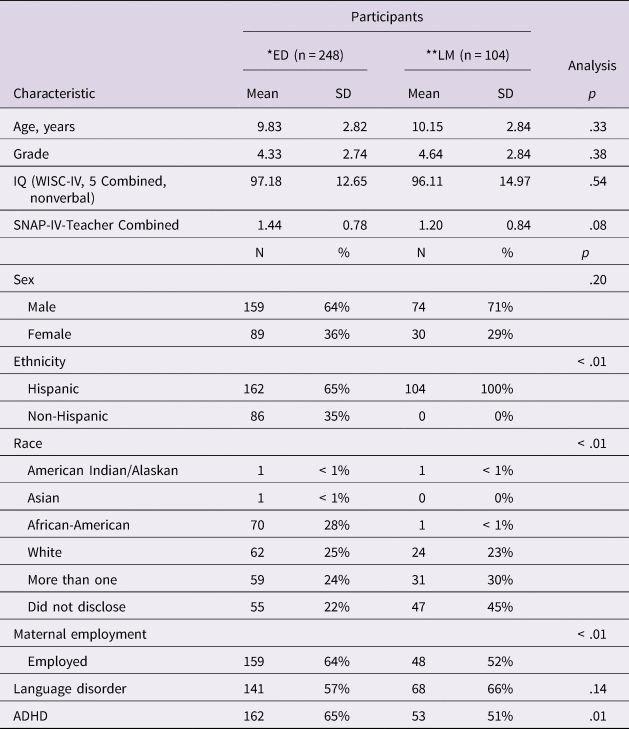

Children from LM and ED homes differed in ethnicity, race, maternal employment, and ADHD diagnosis (Table 1). They did not differ in rate of comorbid language disorder (χ 2 (1, N = 352) = 2.21, p = .14). Average performance on phonological memory, phonological awareness, word reading accuracy, and overall reading composite for each group (ED/LM; RD/non-RD) is presented in Table 2 and for RD versus non-RD in Table S1.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics

Notes: ED = English Dominant; LM = Language Minority. * Missing: Maternal Employment (19), IQ (42), SNAP (155), Grade (35); ** Missing: Maternal Employment (12), IQ (24), SNAP (49), Grade (18).

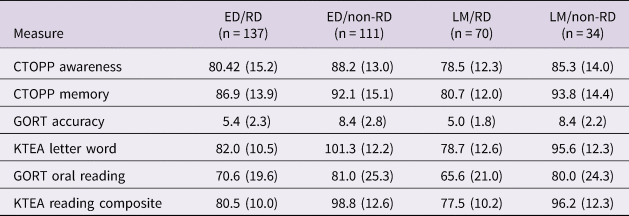

Table 2. Average performance for ED and LM children with and without RD on phonological memory, phonological awareness, word reading accuracy, and overall reading composite scores

Notes: Scores reflect performance on the edition of the measure current at time of assessment.

Scores presented are Standard Scores for CTOPP and KTEA and Scaled Scores for GORT.

CTOPP = Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing; GORT = Gray Oral Reading Test.

Predicting reading disorder from language status and phonological processing

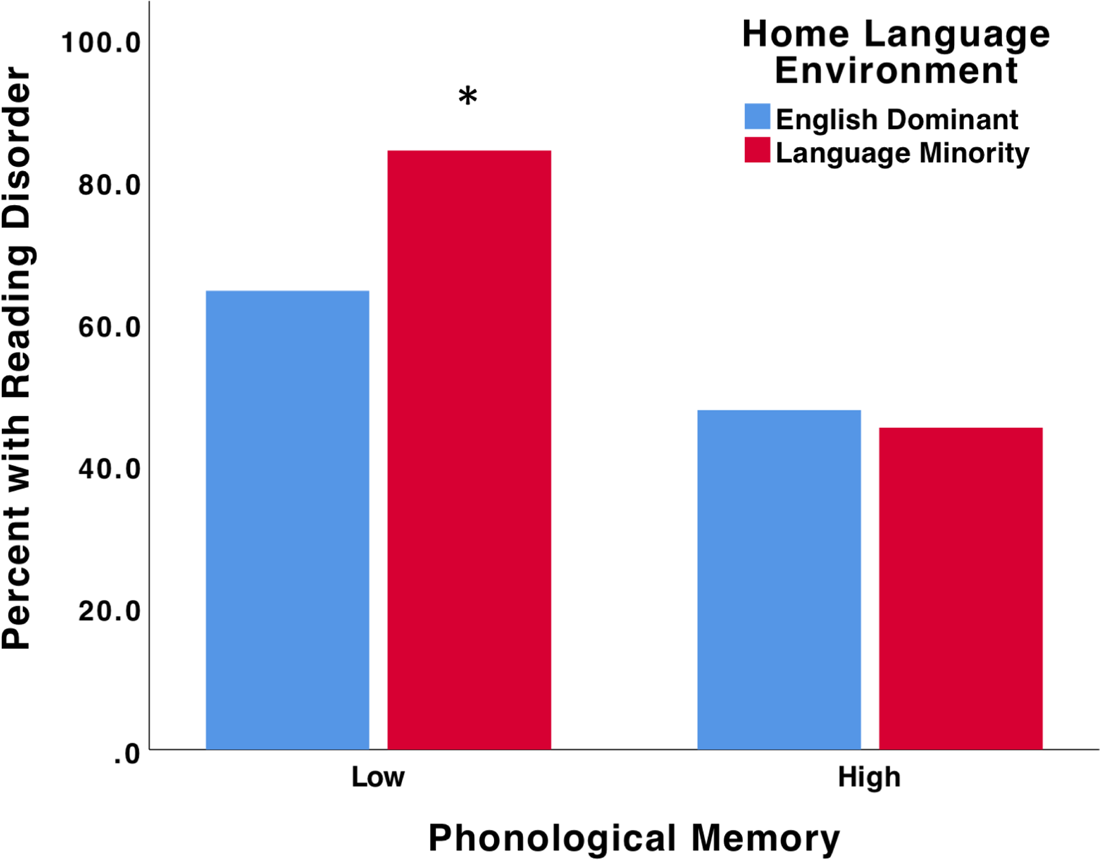

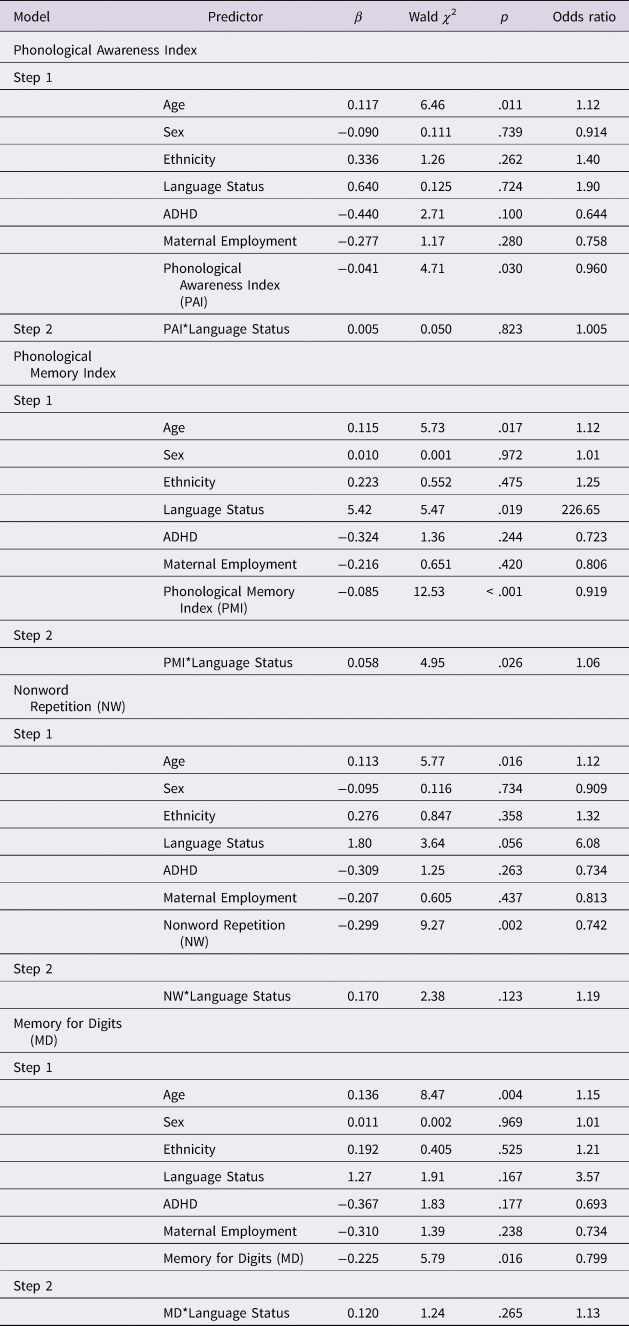

For phonological awareness, the logistic regression model was statistically significant (χ 2(8) = 36.26, p < .001). A significant main effect of phonological awareness (β = –0.041, p = .030) indicated that the likelihood of having RD increased as phonological awareness decreased (Table 3). The interaction between PAI and language status was not significant (p = .823). For phonological memory, the logistic regression model was statistically significant (χ 2(8) = 43.33, p < .001). Main effects of phonological memory (β = –0.085, p < .001), language status (Exp = 226.65, p = .019), and their interaction (β = 0.058, p = .026) were significant, such that phonological memory problems were magnified in children from LM homes when predicting RD (Table 2; Figure 2). To explore what aspects of phonological memory were most magnified in children from LM homes, mean subtest scores for Memory for Digits (MD) and Non-Word Repetition (NW) were used as independent variables in separate logistic regression models (Table 3). Logistic regression models were statistically significant for both MD and NW (ps > .001); the interaction terms for NW (β = 0.170, p = .123) and MD (β = 0.120, p = .265) were not significant.

Figure 2. Phonological memory problems are magnified when predicting RD among children from LM homes. Phonological memory group is represented by a median split of standard scores. * indicates statistically significant difference p < .05.

Table 3. Language status and phonological processing predict reading disorder

Notes: All models were hierarchically well formulated and included all lower-order terms (not shown). When the interaction term was significant only values from step 2 are presented. PAI = Phonological Awareness Index; PMI = Phonological Memory Index; MD = Memory for Digits; NW = Nonword Repetition.

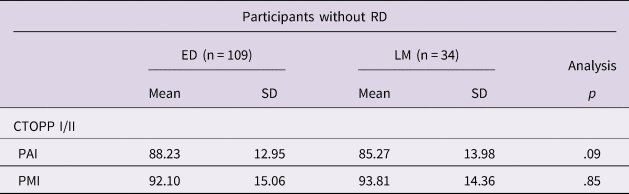

Associations between language status and phonological processing

Among children without RD (n = 143), language status was unrelated to PMI (F(1,124) = 0.171, p = .68) or PAI (F(1,129) = 2.70, p = .10). Notably, both groups performed lower than the normative sample (Table 4), which was stratified to match the US census.

Table 4. Associations between language status and phonological processing in children without reading disorder

Notes: ED = English Dominant; LM = Language Minority; PAI = Phonological Awareness Index; PMI = Phonological Memory Index

Discussion

The current study evaluated associations among language status, phonological memory and awareness, and reading disorder within a large sample of children from low-income backgrounds with suspected learning problems. Language status moderated the association between phonological memory in the language of instruction and reading disorder, such that performance on phonological memory tests was more predictive of having a reading disorder in children from LM versus ED homes. In addition, we tested whether there was a bilingual advantage or disadvantage in phonological processing in children who did not have RD. Among these children, language status was not associated with phonological memory or phonological awareness in the language of instruction. Such findings provide an initial step toward broadening our understanding of language development in the language of instruction in Spanish–English speaking children from low-income backgrounds.

Associations between phonological memory in the language of instruction and RD were magnified in children from LM homes, consistent with the multiplicative factors theory (Noble, Farah, & McCandliss, Reference Noble, Farah and McCandliss2006). These findings align with prior studies showing that phonological processing has greater associations with reading scores among children from low versus high socioeconomic backgrounds (Noble et al., Reference Noble, Farah and McCandliss2006). Bilingual advantage or disadvantage in phonological processing appears to shift with age. Although prior findings document that young children from LM homes show a phonological disadvantage at the beginning of preschool or kindergarten (Brice & Brice, Reference Brice and Brice2009; Hammer & Miccio, Reference Hammer and Miccio2006; Hammer et al., Reference Hammer, Miccio and Wagstaff2003; Lonigan et al., Reference Lonigan, Farver, Nakamoto and Eppe2013; Páez et al., Reference Páez, Tabors and López2007), they make greater gains in phonological skills over the course of the school year (Hammer & Miccio, Reference Hammer and Miccio2006; Lonigan et al., Reference Lonigan, Farver, Nakamoto and Eppe2013). Such improvement is consistent with other studies documenting a phonological advantage in older children from LM versus ED homes (Bialystok et al., Reference Bialystok, Majumder and Martin2003; Bialystok et al., Reference Bialystok, Luk and Kwan2005; Krizman et al., Reference Krizman, Skoe and Kraus2016). Our findings suggest that disadvantaged children who reside in language-minority homes and who have phonological memory problems are at greatest risk for developing RD across a wide age-range.

Many prior studies have shown that phonological processing problems are a core feature of RD (Melby-Lervåg et al., Reference Melby-Lervåg, Lyster and Hulme2012; Vellutino et al., Reference Vellutino, Fletcher, Snowling and Scanlon2004), but fewer studies have examined whether phonological processing problems are associated with RD in children from low-income and diverse ethnic backgrounds (Peterson & Pennington, Reference Peterson and Pennington2015). The current study addresses this gap in the literature. In this sample of low-income, predominantly Hispanic children, the likelihood of RD increased as phonological awareness and phonological memory decreased. Importantly, these findings also suggest that phonological memory and awareness problems and associated reading impairment in this sample are not singularly related to the effects of socioeconomic disadvantage, since children were all from lower SES backgrounds but only some had RD.

Among children without RD, language minority status was unrelated to phonological processing. This finding suggests that English-language phonics assessment with children from LM homes may not be confounded by language minority status. Nonetheless, phonological deficits in children from LM homes are often ascribed to second language acquisition rather than reading disorder (Lesaux & Siegel, Reference Lesaux and Siegel2003), leading to ineffective identification of reading problems and delayed academic intervention (Samson & Lesaux, Reference Samson and Lesaux2009). Results from the current study suggest that children from LM homes who show phonological processing deficits may have RD, which requires specific intervention. These findings offer new information for providers who are tasked with interpreting low phonological processing scores in children from LM homes.

The current study has several limitations. Sixty-three percent of families in the ED group identify as Hispanic, raising the possibility that they hear Spanish in the home environment more than non-Hispanic children from ED backgrounds. However, we controlled for effects of ethnicity in the statistical models, and ethnicity was not associated with phonological awareness or memory. Our study did not have direct measures of participants’ Spanish language proficiency or bilingualism, which might allow for further analysis of the effects of bilingualism on phonological awareness and memory. We did not have a measure of parents’ language proficiency. The age at which children were first exposed to English was also unavailable. In addition, we were unable to study whether RD subtype (word reading accuracy, reading rate or fluency, or reading comprehension) affected our findings as 97 percent of the children in the RD group had word-reading level problems; future studies could examine whether the effects of language minority status on phonological awareness and memory vary by RD subtype. Children in the comparison group also differ from a typical control group, as they likely had other learning, psychiatric, or developmental diagnoses; however, this is in some sense a strength of the study in that all of the children have learning and school related difficulties, thereby equating non-cognitive, psychosocial factors. The sample in this study included students from low-income backgrounds, thus limiting the generalizability of results to children from other socioeconomic backgrounds. However, studying this sample addresses a long-standing gap in the literature identified by multicultural neuropsychologists (Rivera Mindt, Byrd, Saez, & Manly, Reference Rivera Mindt, Byrd, Saez and Manly2010). Lastly, results of primary analyses are corrected for comparisons on multiple measures of phonological processing.

Conclusion

The current study revealed a significant interaction between language status and phonological memory on predicting RD, suggesting that phonological memory problems are magnified in children from Spanish–English LM homes when predicting RD. Moreover, phonological memory and awareness was predictive of RD in this sample of socioeconomically disadvantaged children with suspected learning problems. Last, in those without RD, language status was unrelated to phonological memory, suggesting that tests of phonological memory in English may be appropriate for use in children from Spanish–English LM homes. Our findings have implications for educational advocacy and culturally competent interpretation of neuropsychological test data for low-income, Hispanic children from LM homes, and may thus inform intervention plans for these children.

Supplementary materials

For Supplementary materials for this paper, please visit <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000919000576>

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) K23ES026239, the DeHirsh-Robinson Fellowship, and the Promise Project at Columbia.