1. Introduction

Shock wave/boundary layer interactions (SWBLIs) are ubiquitous in internal and external flow fields of aerospace and aeronautic applications, such as transonic aerofoils, supersonic inlets and over-expansion nozzles (Green Reference Green1970). In the interaction regions, an adverse pressure gradient provoked by shock waves often thickens the boundary layer, causing the latter to be unsteady and even separated. However, the shock-induced separations are generally detrimental to an aircraft. For example, SWBLIs on an aerofoil will increase the drag; concurrently, the accompanying unsteady aerodynamic force and thermal load will affect directly the performance and fatigue life of the aerofoil structures (Dolling Reference Dolling2001; Anderson Reference Anderson2010). In addition, SWBLIs affect adversely the internal flow field in a supersonic inlet, resulting in a considerable loss in total pressure, an increase in the flow distortion, a complicated accompanying shock wave system and formation of the aerodynamic throat. Owing to these factors, the supersonic inlet is under an off-design state, leading to a significant performance degradation of the propulsion system (Babinsky & Ogawa Reference Babinsky and Ogawa2008; Krishnan, Sandham & Steelant Reference Krishnan, Sandham and Steelant2009).

Since the pioneering work by Ferri (Reference Ferri1940), SWBLIs have been investigated extensively to elucidate the complex physical mechanism, wherein the most frequently encountered interactions are shock wave/turbulent boundary layer interactions (SWTBLIs), although shock wave/laminar or transition boundary layer interactions have also been investigated in the literature. According to the type of shock wave and the application geometry, SWBLIs can be categorised into various forms, such as incident SWBLI (ISWBLI), compression ramp-induced SWBLI (CRSWBLI), normal SWBLI and swept SWBLI. In particular, ISWBLIs and CRSWBLIs have attracted considerable attention owing to their simple configuration and quasi-two-dimensional properties (Dolling Reference Dolling2001; Babinsky & Harvey Reference Babinsky and Harvey2011). In the past decades, numerous theoretical, experimental and numerical studies have been conducted on these two categories of interactions, yielding several canonical conclusions on various flow features, including the mean flow configuration (Henderson Reference Henderson1967; Settles Reference Settles1976; Viswanath Reference Viswanath1988; Zheltovodov Reference Zheltovodov2006; Délery & Dussauge Reference Délery and Dussauge2009), pressure distribution (Chapman, Kuehn & Larson Reference Chapman, Kuehn and Larson1957; Erdos & Pallone Reference Erdos and Pallone1962; Carrière, Sirieix & Solignac Reference Carrière, Sirieix and Solignac1969; Charwat Reference Charwat1970; Matheis & Hickel Reference Matheis and Hickel2015) and low-frequency unsteadiness (Dupont, Haddad & Debiève Reference Dupont, Haddad and Debiève2006; Pirozzoli & Grasso Reference Pirozzoli and Grasso2006; Ganapathisubramani, Clemens & Dolling Reference Ganapathisubramani, Clemens and Dolling2007; Dussauge & Piponniau Reference Dussauge and Piponniau2008; Wu & Martín Reference Wu and Martín2008; Piponniau et al. Reference Piponniau, Dussauge, Debiève and Dupont2009; Souverein et al. Reference Souverein, van Oudheusden, Scarano and Dupont2009; Touber & Sandham Reference Touber and Sandham2009; Souverein et al. Reference Souverein, Dupont, Debieve, Dussauge, van Oudheusden and Scarano2010; Touber & Sandham Reference Touber and Sandham2011; Priebe & Martín Reference Priebe and Martín2012; Clemens & Narayanaswamy Reference Clemens and Narayanaswamy2014; Priebe et al. Reference Priebe, Tu, Rowley and Martín2016; Adler & Gaitonde Reference Adler and Gaitonde2018).

The scale of the separated flow induced by SWBLIs is crucial for the geometric design of aeronautical applications. Previous experimental studies have shown that the free-stream Mach number, Reynolds number and deflection angle significantly influence the scale of the separated flow (Thomke & Roshko Reference Thomke and Roshko1969; Spaid & Frishett Reference Spaid and Frishett1972; Settles, Bogdonoff & Vas Reference Settles, Bogdonoff and Vas1976). According to the numerical simulation data, Ramesh & Tannehill (Reference Ramesh and Tannehill2004) established a correlation function that depends on free-stream Mach number, Reynolds number and specific pressure rise to evaluate the streamwise extent of the separation in SWTBLIs. A new scaling approach for the interaction length was derived by Souverein, Bakker & Dupont (Reference Souverein, Bakker and Dupont2013) based on the mass conservation law. By using the non-dimensional shock strength metric and non-dimensional interaction length, the new method can reconcile effectively the variations in experimental and numerical data of ISW/turbulent boundary layer interactions (ISWTBLIs) and compression ramp-induced shock wave/turbulent boundary layer interactions (CRSWTBLIs) with different Mach numbers, Reynolds numbers and geometric configurations. Moreover, heat transfer also plays a significant role in the extent of shock-induced separation (Babinsky & Harvey Reference Babinsky and Harvey2011). The recent studies indicated that the applicability of the adiabatic scaling method by Souverein et al. (Reference Souverein, Bakker and Dupont2013) is limited in hypersonic SWTBLIs in which the heat transfer generally cannot be ignored (Helm Reference Helm2021; Helm & Martín Reference Helm and Martín2021; Hong, Li & Yang Reference Hong, Li and Yang2021). Hong et al. (Reference Hong, Li and Yang2021) found that the relationship between the non-dimensional parameters proposed by Souverein was not accurate enough for hypersonic SWTBLIs. They corrected the new non-dimensional shock strength metric and identified two scaling relationships of the non-dimensional parameters in hypersonic SWTBLIs according to different Reynolds numbers. The study by Helm & Martín (Reference Helm and Martín2021) performed a control volume analysis and derived the corresponding separation length scaling for an axisymmetric cylinder-with-flare geometry (a geometry used commonly in hypersonic cases, see Brooks et al. Reference Brooks, Gupta, Marineau, Martín, Smith and Marineau2017). Considering the difference between the skin friction coefficients in adiabatic and non-adiabatic wall conditions, they modified the scaling method of Souverein et al. (Reference Souverein, Bakker and Dupont2013) and put forward a new generalised scaling method to analyse the data compilation of both the supersonic and hypersonic SWTBLIs with various wall heat transfer conditions. The new generalised scaling of the SWTBLI database (including two-dimensional compression ramp and axisymmetric cylinder-flare cases) showed a linear collapse for all incipiently separated SWTBLI data but a significant spreading in the fully separated regime. Based on the large eddy simulation database, they analysed the physical mechanisms for the two SWTBLI regimes. The result indicated that the momentum distribution in the incoming boundary layer is a crucial factor influencing separation length scaling in the incipiently separated regime; in contrast, the presence and strength of inviscid vortical structures affect significantly the separation length for fully separated cases.

Note that in the aforementioned studies, the separated flows are induced commonly by a single shock wave. However, in the internal compression process of a supersonic mixed-compression inlet with a high Mach number, the multi-stage compression induced by shock waves is often used to efficiently decelerate and pressurise the supersonic airflow (Sanders & Weir Reference Sanders and Weir2008; Tan, Sun & Huang Reference Tan, Sun and Huang2012; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Tan, Sun and Sheng2017). These shock waves inevitably interact with the boundary layer in the channel and induce multi-SWBLIs. For instance, the cowl shock wave and downstream contour-induced shock wave impinge sequentially on the boundary layer on the ramp-side surface. When the two shock interaction regions are close, they combine to form a large-scale separation (Tan et al. Reference Tan, Sun and Huang2012; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Tan, Sun and Sheng2017). Recently, Li et al. (Reference Li, Tan, Zhang, Huang, Guo and Lin2020) employed the ice-cluster-based planar laser scattering (IC-PLS) technique to visualise the flow field of dual-ISWTBLIs in a Mach 2.48 flow with the two deflection angles ![]() $8^\circ$ and

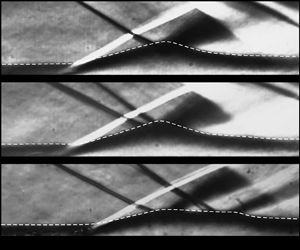

$8^\circ$ and ![]() $5^\circ$. Such a study indicated that the distance between the two incident shock waves (ISWs) affected significantly the overall separation region. According to the shape of the separation bubble, the dual-ISWTBLI flow was of three kinds. The first was a strong coupling separated flow with a triangle-like separation bubble while the shock distance was 0 (figure 1a). As the shock distance increased to four times the boundary layer thickness, the shape of the separation bubble changed to quadrilateral-like, yielding the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI (figure 1b). When the shock distance was sufficiently large (eight times the boundary layer thickness), the third kind of dual-ISWTBLI was formed with the decoupling of the two isolated single-ISWTBLIs (figure 1c). Under the specific experimental condition in the third kind of dual-ISWTBLI in that study, the adverse pressure gradient in the two single-ISWTBLIs was insufficient to induce a fully separated flow, so there are no visible separation bubbles in figure 1(c). Moreover, Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Li, Tan, Sun, Wu and Zhang2021) presented the three-dimensional structures in dual-swept SWTBLIs, thereby showing that the separated flow in the wall vicinity was extremely complicated. The overall flow can be regarded as a combination of three interactions induced by the first, second and converged swept shock waves; these interactions provoked the corresponding separation and rear shock waves, which interacted with each other and afforded a spatially intricate shock wave system.

$5^\circ$. Such a study indicated that the distance between the two incident shock waves (ISWs) affected significantly the overall separation region. According to the shape of the separation bubble, the dual-ISWTBLI flow was of three kinds. The first was a strong coupling separated flow with a triangle-like separation bubble while the shock distance was 0 (figure 1a). As the shock distance increased to four times the boundary layer thickness, the shape of the separation bubble changed to quadrilateral-like, yielding the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI (figure 1b). When the shock distance was sufficiently large (eight times the boundary layer thickness), the third kind of dual-ISWTBLI was formed with the decoupling of the two isolated single-ISWTBLIs (figure 1c). Under the specific experimental condition in the third kind of dual-ISWTBLI in that study, the adverse pressure gradient in the two single-ISWTBLIs was insufficient to induce a fully separated flow, so there are no visible separation bubbles in figure 1(c). Moreover, Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Li, Tan, Sun, Wu and Zhang2021) presented the three-dimensional structures in dual-swept SWTBLIs, thereby showing that the separated flow in the wall vicinity was extremely complicated. The overall flow can be regarded as a combination of three interactions induced by the first, second and converged swept shock waves; these interactions provoked the corresponding separation and rear shock waves, which interacted with each other and afforded a spatially intricate shock wave system.

Figure 1. IC-PLS images of three kinds of dual-ISWTBLI (Li et al. Reference Li, Tan, Zhang, Huang, Guo and Lin2020). (a) First kind of dual-ISWTBLI, with ![]() $Ma_0 = 2.48$,

$Ma_0 = 2.48$, ![]() $\alpha _1 = 8^\circ$,

$\alpha _1 = 8^\circ$, ![]() $\alpha _2 = 5^\circ$ and

$\alpha _2 = 5^\circ$ and ![]() $d = 0\delta _0$. (b) Second kind of dual-ISWTBLI, with

$d = 0\delta _0$. (b) Second kind of dual-ISWTBLI, with ![]() $Ma_0 = 2.48$,

$Ma_0 = 2.48$, ![]() $\alpha _1 = 8^\circ$,

$\alpha _1 = 8^\circ$, ![]() $\alpha _2 = 5^\circ$ and

$\alpha _2 = 5^\circ$ and ![]() $d = 4\delta _0$. (c) Third kind of dual-ISWTBLI, with

$d = 4\delta _0$. (c) Third kind of dual-ISWTBLI, with ![]() $Ma_0 = 2.48$,

$Ma_0 = 2.48$, ![]() $\alpha _1 = 8^\circ$,

$\alpha _1 = 8^\circ$, ![]() $\alpha _2 = 5^\circ$ and

$\alpha _2 = 5^\circ$ and ![]() $d = 8\delta _0$. The symbols

$d = 8\delta _0$. The symbols ![]() $Ma_0$,

$Ma_0$, ![]() $\alpha _1$,

$\alpha _1$, ![]() $\alpha _2$,

$\alpha _2$, ![]() $d$ and

$d$ and ![]() $\delta _0$ denote the free-stream Mach number, first deflection angle, second deflection angle, shock distance and boundary layer thickness, respectively.

$\delta _0$ denote the free-stream Mach number, first deflection angle, second deflection angle, shock distance and boundary layer thickness, respectively.

The multi-SWTBLI flow is ubiquitous in the supersonic mixed-compression inlet, and the sub-interaction regions often combine to form a fairly complex separated flow (Gaitonde Reference Gaitonde2015). The interaction of the turbulent boundary layer with dual-ISWs is one of the simplest forms of the multi-SWTBLIs. However, the previous study on dual-ISWTBLIs (Li et al. Reference Li, Tan, Zhang, Huang, Guo and Lin2020) was based solely on IC-PLS images, and quantitative analysis of the effect of shock distance on the flow features (such as the exact extent of the reverse flow region and wall pressure distribution) was not available. Therefore, to study quantitatively the flow mechanism involved in the dual-ISWTBLIs, this paper performs a comparative investigation on single-ISWTBLIs and dual-ISWTBLIs with identical total deflection angles by using schlieren photography, wall-pressure measurement and surface oil-flow visualisation. Since the third kind of dual-ISWTBLI can be regarded as two isolated single-ISWTBLIs, its flow features can be described by referring to the single-ISWTBLI theory reported in the literature. Therefore, this study focuses on only the first and second kinds of dual-ISWTBLIs, in which the coupling of the two sub-interactions leads to complex separation configurations. First, the impingement points of the two ISWs were ensured to intersect on the bottom wall to yield the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI. The similarities and differences between the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI and the single-ISWTBLI with an identical total deflection angle condition were analysed. Then the distance between the two ISWs was increased to explore its effect on the separation flow. Based on the free-interaction theory, an inviscid simplified model was developed for dual-ISWTBLI flow to describe the separation configurations, based on which the factors influencing the shape of the separation bubble were investigated in detail.

2. Experimental methodology

2.1. Wind tunnel and test model

Experiments were performed in a wind tunnel at Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics. The wind tunnel is a free-jet type with an atmospheric environment upstream and a ![]() $300~{\rm m}^{3}$ vacuum spherical tank downstream. When the wind tunnel is in operation, a uniform supersonic flow of Mach 2.73 is produced downstream of the Laval nozzle. The exit section of the nozzle is a square with dimensions

$300~{\rm m}^{3}$ vacuum spherical tank downstream. When the wind tunnel is in operation, a uniform supersonic flow of Mach 2.73 is produced downstream of the Laval nozzle. The exit section of the nozzle is a square with dimensions ![]() $200 \times 200\ {\rm mm}^{2}$. The operating time of the wind tunnel is 14 s. The total pressure of supersonic flow is

$200 \times 200\ {\rm mm}^{2}$. The operating time of the wind tunnel is 14 s. The total pressure of supersonic flow is ![]() $100 \pm 0.3\ {\rm kPa}$, the total temperature is

$100 \pm 0.3\ {\rm kPa}$, the total temperature is ![]() $286 \pm 1.5\ {\rm K}$ and the unit Reynolds number is approximately

$286 \pm 1.5\ {\rm K}$ and the unit Reynolds number is approximately ![]() $9.2 \times 10^6\ {\rm m}^{-1}$.

$9.2 \times 10^6\ {\rm m}^{-1}$.

Figure 2(a) is a picture of the test model in the wind tunnel, which mainly comprised a shock generator, two sidewalls embedded with optical glass and a bottom wall. Figures 2(b) and 2(c) are schematics of the test model and its relative position with the Laval nozzle, respectively. In this study, the spanwise width between the two sidewalls is 140 mm. The leading edges of the sidewall and bottom wall are unaligned, with the former 90 mm downstream of the latter. The short-sidewall arrangement is adopted to restrict the development of the sidewall boundary layer, thereby decreasing the sidewall effect on the flows in the central region. The pre-test indicated that the boundary layer 150 mm downstream of the leading edge of the bottom wall maintained a laminar state. Therefore, a rough band is set 10 mm downstream of the leading edge of the bottom wall to promote the boundary layer transition and ensure that the boundary layer upstream of the SWBLI is turbulent. The spanwise width of the front part of the bottom wall is 160 mm, and two winglets are installed on both sides to prevent the potential lateral flow from disturbing the incoming boundary layer.

Figure 2. Experimental set-up of the working section: (a) picture of the test model; (b) schematic diagram of the test model; (c) relative position of the test model and Laval nozzle.

2.2. Shock generator

In this study, single-ISWTBLIs and dual-ISWTBLIs were investigated. The single-ISW and dual-ISWs were generated using a single-ramp wedge and a dual-ramp wedge, respectively. A schematic of the shock generator is depicted in figure 3. In fact, the single-ISWTBLI can be regarded as a particular case of the dual-ISWTBLIs when the first or second deflection angle is ![]() $0^\circ$. Geometric parameters of nine shock generators are listed in table 1, including the leading edge height (

$0^\circ$. Geometric parameters of nine shock generators are listed in table 1, including the leading edge height (![]() $h$), spanwise width (

$h$), spanwise width (![]() $w$), total deflection angle (

$w$), total deflection angle (![]() $\alpha _t$), first deflection angle (

$\alpha _t$), first deflection angle (![]() $\alpha _1$), second deflection angle (

$\alpha _1$), second deflection angle (![]() $\alpha _2$), length of the first ramp (

$\alpha _2$), length of the first ramp (![]() $l_1$), and length of the second ramp (

$l_1$), and length of the second ramp (![]() $l_2$). As shown in figure 3, in the dual-ISWTBLIs, two inviscid ISWs intersect the centreline of the bottom wall at the points

$l_2$). As shown in figure 3, in the dual-ISWTBLIs, two inviscid ISWs intersect the centreline of the bottom wall at the points ![]() $O_1$ and

$O_1$ and ![]() $O_2$, respectively. The distance between

$O_2$, respectively. The distance between ![]() $O_1$ and

$O_1$ and ![]() $O_2$ is defined as the shock distance

$O_2$ is defined as the shock distance ![]() $d$ (where

$d$ (where ![]() $d=x_{O2}-x_{O1}$). Among the tests, cases 1–3 correspond to single-ISWTBLIs with deflection angles

$d=x_{O2}-x_{O1}$). Among the tests, cases 1–3 correspond to single-ISWTBLIs with deflection angles ![]() $10^\circ$,

$10^\circ$, ![]() $11^\circ$ and

$11^\circ$ and ![]() $12^\circ$, respectively. Cases 4–7 correspond to dual-ISWTBLIs with total deflection angles

$12^\circ$, respectively. Cases 4–7 correspond to dual-ISWTBLIs with total deflection angles ![]() $12^\circ$,

$12^\circ$, ![]() $12^\circ$,

$12^\circ$, ![]() $11^\circ$ and

$11^\circ$ and ![]() $10^\circ$, respectively; and the shock distance in the four cases was set to 0 mm to form the first kind of dual-ISWTBLIs. Then, in cases 8 and 9, the shock distance

$10^\circ$, respectively; and the shock distance in the four cases was set to 0 mm to form the first kind of dual-ISWTBLIs. Then, in cases 8 and 9, the shock distance ![]() $d$ was enlarged to a moderate value to form the second kind of dual-ISWTBLIs with different deflection angle combinations: (

$d$ was enlarged to a moderate value to form the second kind of dual-ISWTBLIs with different deflection angle combinations: (![]() $\alpha _1 = 5^\circ$,

$\alpha _1 = 5^\circ$, ![]() $\alpha _2 = 7^\circ$) and (

$\alpha _2 = 7^\circ$) and (![]() $\alpha _1 = 7^\circ$,

$\alpha _1 = 7^\circ$, ![]() $\alpha _2 = 5^\circ$), respectively. In dual-ISWTBLIs, the adjustment of

$\alpha _2 = 5^\circ$), respectively. In dual-ISWTBLIs, the adjustment of ![]() $d$ was achieved by changing the length of the first ramp. Due to the elongation of the shock generator along the streamwise direction in cases 8 and 9, the leading edge height of the shock generator

$d$ was achieved by changing the length of the first ramp. Due to the elongation of the shock generator along the streamwise direction in cases 8 and 9, the leading edge height of the shock generator ![]() $h$ was increased appropriately to avoid the unstart state owing to the large contraction ratio of the channel. Constrained by the test model's geometry, the coordinate of point

$h$ was increased appropriately to avoid the unstart state owing to the large contraction ratio of the channel. Constrained by the test model's geometry, the coordinate of point ![]() $O_1$ in the case of single-ISWTBLIs was 255 mm downstream of the leading edge of the bottom wall, whereas the coordinate of point

$O_1$ in the case of single-ISWTBLIs was 255 mm downstream of the leading edge of the bottom wall, whereas the coordinate of point ![]() $O_1$ in the case of dual-ISWTBLIs was 265 mm downstream of the leading edge of the bottom wall. Therefore, the origin of the coordinate system in each case was set at point

$O_1$ in the case of dual-ISWTBLIs was 265 mm downstream of the leading edge of the bottom wall. Therefore, the origin of the coordinate system in each case was set at point ![]() $O_1$ to facilitate comparisons between different cases. Also, as shown in figure 2(b), the

$O_1$ to facilitate comparisons between different cases. Also, as shown in figure 2(b), the ![]() $x$-,

$x$-, ![]() $y$- and

$y$- and ![]() $z$-axes correspond to the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise directions, respectively.

$z$-axes correspond to the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise directions, respectively.

Figure 3. Schematic of shock generator.

Table 1. Geometric parameters of shock generators.

2.3. Experimental measurement methods

We detected the flow fields using a combination of schlieren photography, static pressure measurement and surface oil-flow visualisation.

Schlieren photography is an optical measurement method commonly used to study SWBLI flows. Schlieren images can reflect the density gradient of the airflow such that the shock waves, expansion waves and shear layer can be visualised. As shown in figure 4, the schlieren system in this experiment has a classical ‘Z-type’ configuration, with a xenon lamp point light source, a pair of concave mirrors with 200 mm diameter and 2000 mm focal length, a knife edge and a high-speed camera. The first concave mirror reflected the emanative light from the point light source into parallel light rays, which then penetrated the test section and cast on another concave mirror. The second concave mirror focalised the light to a focus where a knife edge was placed horizontally. A high-speed camera (NAC Memrecam HX-3) equipped with a lens of Nikon AF vr80–400 mm f/4.5-5.6d was employed to capture schlieren image sequences with resolution ![]() $300 \times 900$ (

$300 \times 900$ (![]() $\approx$ 6 pixels

$\approx$ 6 pixels ![]() ${\rm mm}^{-1}$) at a 20-k frame rate and a

${\rm mm}^{-1}$) at a 20-k frame rate and a ![]() $3.3~\mathrm {\mu }{\rm s}$ exposure time.

$3.3~\mathrm {\mu }{\rm s}$ exposure time.

Figure 4. Sketch of the schlieren system.

As shown in figure 2(b), 55 static pressure tappings were distributed evenly along the centreline of the steel bottom wall, in the range 165–327 mm downstream of the leading edge. The distance between two adjacent tappings was 3 mm. Using the rubber tubing, the static pressure tappings were connected to pressure transducers (CYG-503, Double Bridge Inc.) with measurement range 100 kPa and accuracy 0.1 % FS (i.e. ![]() $\pm$0.1 kPa). All pressure signals were acquired using two National Instruments DAQ 6225 cards at a 1 kHz sampling rate. Before every run, all pressure transducers were carefully recalibrated using a high-precision pressure gauge to eliminate drift errors.

$\pm$0.1 kPa). All pressure signals were acquired using two National Instruments DAQ 6225 cards at a 1 kHz sampling rate. Before every run, all pressure transducers were carefully recalibrated using a high-precision pressure gauge to eliminate drift errors.

Surface oil-flow visualisation is an effective method for examining the mean flow structures in SWTBLIs. The oil mixture in this study comprised oleic acid, silicone oil and titanium dioxide powder. It should be noted that a steel plate embedded with optical glass was employed as the bottom wall to facilitate the imaging of streamlines in the flow field of interest. Before the test, the oil mixture was smeared evenly on the upper surface of the optical glass. A digital camera (Canon 1Dx Mark II) with a prime lens (Tokina AT-X Pro Macro 100 mm F2.8 D) was placed under the bottom wall to capture the images through the optical glass.The images with a ![]() $5742 \times 3648$ resolution (

$5742 \times 3648$ resolution (![]() $\approx$ 12 pixels mm

$\approx$ 12 pixels mm![]() $^{-1}$) were captured when the wind tunnel was in operation rather than after its shutdown, since the wind tunnel unstart shock would contaminate the oil flow structures.

$^{-1}$) were captured when the wind tunnel was in operation rather than after its shutdown, since the wind tunnel unstart shock would contaminate the oil flow structures.

3. Result

3.1. Upstream turbulent boundary layer

To obtain the flow parameters of the undisturbed boundary layer, the Pitot-pressure profile was measured by using a movable miniature Pitot probe at the location 195 mm downstream of the leading edge of the bottom wall (immediately upstream of the interaction region). According to the Pitot-pressure profile and the wall static pressure (the assumption of constant static pressure in the wall-normal direction is used), the Mach number profile within the boundary layer is obtained by using the Rayleigh–Pitot relation (Anderson Reference Anderson2010). Under the assumption of a turbulent recovery factor ![]() $r = 0.89$ and a nearly adiabatic wall condition, the static temperature profile and the velocity profile can be calculated based on the Crocco–Busemann relation (White Reference White2006). Then we can obtain the density profile through the ideal-gas state function

$r = 0.89$ and a nearly adiabatic wall condition, the static temperature profile and the velocity profile can be calculated based on the Crocco–Busemann relation (White Reference White2006). Then we can obtain the density profile through the ideal-gas state function ![]() $\rho = p/RT$. The method proposed by Kendall & Koochesfahani (Reference Kendall and Koochesfahani2008) is used to estimate the friction velocity

$\rho = p/RT$. The method proposed by Kendall & Koochesfahani (Reference Kendall and Koochesfahani2008) is used to estimate the friction velocity ![]() $u_{\tau }$. The wall shear stress

$u_{\tau }$. The wall shear stress ![]() $\tau _{w}$ can be calculated by using the relation

$\tau _{w}$ can be calculated by using the relation ![]() $\tau _{w}=\rho _{w}u^{2}_{\tau }$. The wall friction coefficient,

$\tau _{w}=\rho _{w}u^{2}_{\tau }$. The wall friction coefficient, ![]() $C_{{f,0}}$ = 2

$C_{{f,0}}$ = 2![]() $\tau _{w}/\rho _{0}u^2_{0}$, was found to be 0.00214. The transformed velocity profile by using the method of van Driest (Reference van Driest1951) is plotted in figure 5. The relevant parameters of the boundary layer are listed in table 2 for the free-stream Mach number

$\tau _{w}/\rho _{0}u^2_{0}$, was found to be 0.00214. The transformed velocity profile by using the method of van Driest (Reference van Driest1951) is plotted in figure 5. The relevant parameters of the boundary layer are listed in table 2 for the free-stream Mach number ![]() $Ma_0$, free-stream streamwise velocity

$Ma_0$, free-stream streamwise velocity ![]() $u_0$, undisturbed upstream boundary layer thickness

$u_0$, undisturbed upstream boundary layer thickness ![]() $\delta _0$, displacement thickness

$\delta _0$, displacement thickness ![]() $\delta ^*$, momentum thickness

$\delta ^*$, momentum thickness ![]() $\theta$, shape factor

$\theta$, shape factor ![]() $H$, Reynolds number

$H$, Reynolds number ![]() $Re_{\theta }$ and wall friction coefficient

$Re_{\theta }$ and wall friction coefficient ![]() $C_{{f,0}}$.

$C_{{f,0}}$.

Figure 5. Velocity profile of the upstream turbulent boundary layer. Here, ![]() $u_{vd}^{+}$ is the van Driest transformed streamwise velocity.

$u_{vd}^{+}$ is the van Driest transformed streamwise velocity.

Table 2. Turbulent boundary layer parameters.

![]() $^{a}$The corresponding compressible value.

$^{a}$The corresponding compressible value.

3.2. Single-ISWTBLI

Single-ISWTBLIs are interactions considered commonly in the literature (Dolling Reference Dolling2001; Babinsky & Harvey Reference Babinsky and Harvey2011). In this subsection, experiments are first performed on single-ISWTBLIs with three different deflection angles to provide a reference for subsequent dual-ISWTBLIs analysis.

The schlieren images of cases 1–3 are depicted in figure 6(a), indicating that the shock strength in each case could result in a visible boundary layer separation. Note that the schlieren image in this paper is an average result of 200 successive snapshots (about 10 ms). This is for a good presentation of the mean flow field configuration. A horizontally placed knife edge was used in the schlieren system; hence the different colours in the images report the density changes along the vertical direction. More specifically, the ISW, turbulent boundary layer, shear layer of separation bubble and expansion fan emanating from the apex of the separation bubble are black in the schlieren image. Meanwhile, the separation shock wave and reattachment compression waves are white. The schlieren images show that the shape of the separation bubble induced by single-ISW is triangle-like. The extent of the separation region increases with the deflection angle, which is consistent with the conclusions reported in the previous study (Law Reference Law1976). In the pressure distribution curves of figure 6(b), the positions of the separation and reattachment points on the centreline are indicated by dash-dot lines. It has been reported that the pressure rise (![]() $\Delta P_T$) imparted by the SWTBLI can be decompounded into two stages, i.e. the initial pressure rise at separation (

$\Delta P_T$) imparted by the SWTBLI can be decompounded into two stages, i.e. the initial pressure rise at separation (![]() $\Delta P_S$) and the pressure rise at reattachment (

$\Delta P_S$) and the pressure rise at reattachment (![]() $\Delta P_R$) (Babinsky & Harvey Reference Babinsky and Harvey2011). As can be seen in figure 6(b), the two stages occurred in all three cases. A closer inspection reveals that the first pressure rises are basically the same in all three cases; more precisely, the value of the inflection point in the pressure distribution curve is approximately 2.28 times the free-stream flow pressure

$\Delta P_R$) (Babinsky & Harvey Reference Babinsky and Harvey2011). As can be seen in figure 6(b), the two stages occurred in all three cases. A closer inspection reveals that the first pressure rises are basically the same in all three cases; more precisely, the value of the inflection point in the pressure distribution curve is approximately 2.28 times the free-stream flow pressure ![]() $p_0$. As a result, a higher pressure rise at the reattachment is required for cases with stronger ISWs. Moreover, a common phenomenon – the static pressure decreases after the second pressure rise process – emerges in all three cases. This pressure drop is caused by the impingement of the expansion wave emanating from the shock-generator tail (Daub, Willems & Gülhan Reference Daub, Willems and Gülhan2016; Grossman & Bruce Reference Grossman and Bruce2018). However, this phenomenon is inevitable in the experimental study of ISWTBLIs due to the geometric limitations of the test models.

$p_0$. As a result, a higher pressure rise at the reattachment is required for cases with stronger ISWs. Moreover, a common phenomenon – the static pressure decreases after the second pressure rise process – emerges in all three cases. This pressure drop is caused by the impingement of the expansion wave emanating from the shock-generator tail (Daub, Willems & Gülhan Reference Daub, Willems and Gülhan2016; Grossman & Bruce Reference Grossman and Bruce2018). However, this phenomenon is inevitable in the experimental study of ISWTBLIs due to the geometric limitations of the test models.

Figure 6. Flow features of single-ISWTBLIs: (a) schlieren images; (b) static pressure distribution curve along the centreline. The coordinates of the separation point (![]() $x_{s,cl}$) and reattachment point (

$x_{s,cl}$) and reattachment point (![]() $x_{r,cl}$) on the centreline are indicated by dash-dot lines.

$x_{r,cl}$) on the centreline are indicated by dash-dot lines.

In the past, numerous experimental and numerical studies have indicated that the sidewall effect could excite three-dimensional structures along the spanwise direction in ISWTBLI flows (Green Reference Green1970; Reda & Murphy Reference Reda and Murphy1973; Bookey, Wyckham & Smits Reference Bookey, Wyckham and Smits2005; Babinsky, Oorebeek & Cottingham Reference Babinsky, Oorebeek and Cottingham2013; Benek, Suchyta & Babinsky Reference Benek, Suchyta and Babinsky2013; Bermejo-Moreno et al. Reference Bermejo-Moreno, Campo, Larsson, Bodart, Helmer and Eaton2014; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Sandham, Hu and Liu2015; Grossman & Bruce Reference Grossman and Bruce2018; Xiang & Babinsky Reference Xiang and Babinsky2019). A common conclusion of these studies is that the three-dimensional separation presents an ‘owl-face’ topology (proposed by Perry & Hornung Reference Perry and Hornung1984). As summarised by Xiang & Babinsky (Reference Xiang and Babinsky2019), two typical ‘owl-face’ topologies occur commonly in ISWTBLIs. In the first topology (figure 7a), two focuses are located near the corner, and two saddles are situated at the midpoints of the separation and reattachment lines, respectively. Compared with the first topology, the second topology (figure 7b) presents a different critical-point distribution in the reattachment region, with a large-scale node in the middle and two saddle points offset laterally. In the study by Xiang & Babinsky (Reference Xiang and Babinsky2019), it has been found that the geometry of the corner separation plays an essential role in the overall surface-flow topology, which would change to another kind as the corner-separation location or intensity changes.

Figure 7. Two typical surface-flow topologies in single-ISWTBLIs (summarised by Xiang & Babinsky Reference Xiang and Babinsky2019).

Although the thickness of the sidewall boundary layer was controlled in this study, the sidewall effect could not be eliminated. As shown in the surface oil-flow visualisations in figure 8, the quasi-two-dimensional feature of the ISWTBLI flow was smudged by the sidewall effect. The topological structures, which are three-dimensional and nearly symmetric about the centreline, are presented clearly in the oil-flow images in figure 8, with annotated diagrams underneath. From these images, we can observe that the upstream separation line is formed by the accumulation of the oil flow, whereas the streamline in the downstream reattachment region is dispersive. According to these streamlines, the reverse-flow region can be inspected visually. In figure 8, the locations of the separation point, reattachment point on the centreline and impingement point of the first ISW (![]() $O_1$) are indicated by the red, blue and purple dashed lines, respectively. As the deflection angle increased from

$O_1$) are indicated by the red, blue and purple dashed lines, respectively. As the deflection angle increased from ![]() $10^\circ$ to

$10^\circ$ to ![]() $11^\circ$ and

$11^\circ$ and ![]() $12^\circ$, the separation point on the centreline moves upstream from

$12^\circ$, the separation point on the centreline moves upstream from ![]() $x_{s,cl}=-33.1\ {\rm mm}$ to

$x_{s,cl}=-33.1\ {\rm mm}$ to ![]() $-42.8$ mm and

$-42.8$ mm and ![]() $-56.5$ mm, whereas the reattachment point on the centreline moves slightly downstream, from

$-56.5$ mm, whereas the reattachment point on the centreline moves slightly downstream, from ![]() $x_{r,cl} = 4.0\ {\rm mm}$ to 4.9 mm and 6.0 mm, respectively. Although the extents of the reverse-flow regions in cases 1–3 are different (increasing with the shock strength), the separated flows exhibited similar surface-flow topologies; in other words, the distributions of the critical points in different cases are basically the same, including (i) two focus points (

$x_{r,cl} = 4.0\ {\rm mm}$ to 4.9 mm and 6.0 mm, respectively. Although the extents of the reverse-flow regions in cases 1–3 are different (increasing with the shock strength), the separated flows exhibited similar surface-flow topologies; in other words, the distributions of the critical points in different cases are basically the same, including (i) two focus points (![]() $F_{1}, F_{1}^{\prime }$) near the two sidewalls, (ii) a separation node

$F_{1}, F_{1}^{\prime }$) near the two sidewalls, (ii) a separation node ![]() $N_1$ at the middle of the upstream separation line with two saddle points (

$N_1$ at the middle of the upstream separation line with two saddle points (![]() $S_1, S_{1}^{\prime }$) offset, (iii) a reattachment node

$S_1, S_{1}^{\prime }$) offset, (iii) a reattachment node ![]() $N_2$ at the middle of the downstream reattachment line with two saddle points (

$N_2$ at the middle of the downstream reattachment line with two saddle points (![]() $S_2, S_{2}^{\prime }$) offset, and (iv) a pair of small-scale focus points (

$S_2, S_{2}^{\prime }$) offset, and (iv) a pair of small-scale focus points (![]() $F_2, F_{2}^{\prime }$) and two saddle points (

$F_2, F_{2}^{\prime }$) and two saddle points (![]() $S_3, S_{4}$) in the region between the separation and reattachment nodes. As shown in figure 8, the streamlines originating from node

$S_3, S_{4}$) in the region between the separation and reattachment nodes. As shown in figure 8, the streamlines originating from node ![]() $N_2$ converge with the streamline from the near-sidewall region, leading to two asymptotic-convergence lines connecting the two groups of saddles:

$N_2$ converge with the streamline from the near-sidewall region, leading to two asymptotic-convergence lines connecting the two groups of saddles: ![]() $S_1-S_2$ and

$S_1-S_2$ and ![]() $S_{1}^{\prime }-S_{2}^{\prime }$. According to the two asymptotic-convergence lines, we can divide the overall flow field into three regions, i.e. the core flow region in the middle of the test model slightly affected by the sidewall effect, and the two regions occupied by the focus points (

$S_{1}^{\prime }-S_{2}^{\prime }$. According to the two asymptotic-convergence lines, we can divide the overall flow field into three regions, i.e. the core flow region in the middle of the test model slightly affected by the sidewall effect, and the two regions occupied by the focus points (![]() $F_1, F_{1}^{\prime }$) that are induced by the sidewall effect. Also, two streams from the saddle points

$F_1, F_{1}^{\prime }$) that are induced by the sidewall effect. Also, two streams from the saddle points ![]() $S_1$ and

$S_1$ and ![]() $S_{1}^{\prime }$ converge at the centreline, leading to the emergence of the saddle point

$S_{1}^{\prime }$ converge at the centreline, leading to the emergence of the saddle point ![]() $S_3$. Thereafter, one of the two streams from saddle point

$S_3$. Thereafter, one of the two streams from saddle point ![]() $S_3$ moves upstream to node

$S_3$ moves upstream to node ![]() $N_1$, whereas the other collides with the reverse flow from node

$N_1$, whereas the other collides with the reverse flow from node ![]() $N_2$, yielding another saddle point

$N_2$, yielding another saddle point ![]() $S_{4}$, and finally spiralling into the focus points

$S_{4}$, and finally spiralling into the focus points ![]() $F_2$ and

$F_2$ and ![]() $F_{2}^{\prime }$. The separation and reattachment lines exhibit the ‘saddle–node–saddle’ combination structures with a ‘

$F_{2}^{\prime }$. The separation and reattachment lines exhibit the ‘saddle–node–saddle’ combination structures with a ‘![]() $\bigwedge$

$\bigwedge$![]() $\bigwedge$’ and ‘

$\bigwedge$’ and ‘![]() $\bigvee$

$\bigvee$![]() $\bigvee$’ shape, respectively, indicating that the separation length varies spanwise, with three local minima at the centreline and in the vicinity of the two sidewalls, and two local maxima near the spanwise positions of

$\bigvee$’ shape, respectively, indicating that the separation length varies spanwise, with three local minima at the centreline and in the vicinity of the two sidewalls, and two local maxima near the spanwise positions of ![]() $S_1$ and

$S_1$ and ![]() $S_{1}^{\prime }$. Furthermore, a closer inspection of figure 8(c) reveals that additional saddles and nodes appear near the sidewall, indicating that a stronger shock wave could induce a more complex surface-flow topology.

$S_{1}^{\prime }$. Furthermore, a closer inspection of figure 8(c) reveals that additional saddles and nodes appear near the sidewall, indicating that a stronger shock wave could induce a more complex surface-flow topology.

Figure 8. Surface topologies of single-ISWTBLI. (a) Case 1, ![]() $\alpha _1=10^\circ$,

$\alpha _1=10^\circ$, ![]() $\alpha _2=0^\circ$. (b) Case 2,

$\alpha _2=0^\circ$. (b) Case 2, ![]() $\alpha _1=11^\circ$,

$\alpha _1=11^\circ$, ![]() $\alpha _2=0^\circ$. (c) Case 3,

$\alpha _2=0^\circ$. (c) Case 3, ![]() $\alpha _1=12^\circ$,

$\alpha _1=12^\circ$, ![]() $\alpha _2=0^\circ$. The purple, red and blue dashed lines indicate the locations of the first inviscid impingement point, the separation point and the reattachment point on the centreline, respectively.

$\alpha _2=0^\circ$. The purple, red and blue dashed lines indicate the locations of the first inviscid impingement point, the separation point and the reattachment point on the centreline, respectively.

It is clear that the overall separation topology in this study is more complicated than the two typical topologies in which the flow in the mid-plane is affected by the sidewall effect to various extents (figure 7). The ratio of entrance width and height (![]() $W/H$) in cases 1–3 is 2.5, which is larger than that in the previous experimental studies:

$W/H$) in cases 1–3 is 2.5, which is larger than that in the previous experimental studies: ![]() $W/H=1.40$, 1.33, 1.40 and 1.0–1.38 in the experiments of Bookey et al. (Reference Bookey, Wyckham and Smits2005), Babinsky et al. (Reference Babinsky, Oorebeek and Cottingham2013), Xiang & Babinsky (Reference Xiang and Babinsky2019) and Grossman & Bruce (Reference Grossman and Bruce2018) . Additionally, the thin sidewall boundary layer can constrain effectively the scale of the corner separation. Therefore, the sidewall effect slightly affects the core flow in the central region of the test model in this study. We can imagine that if the test model width decreases or the sidewall-boundary layer thickness increases, then the spanwise extent of the core flow in the central region of the test model would shrink. While reaching a particular situation where the saddles

$W/H=1.40$, 1.33, 1.40 and 1.0–1.38 in the experiments of Bookey et al. (Reference Bookey, Wyckham and Smits2005), Babinsky et al. (Reference Babinsky, Oorebeek and Cottingham2013), Xiang & Babinsky (Reference Xiang and Babinsky2019) and Grossman & Bruce (Reference Grossman and Bruce2018) . Additionally, the thin sidewall boundary layer can constrain effectively the scale of the corner separation. Therefore, the sidewall effect slightly affects the core flow in the central region of the test model in this study. We can imagine that if the test model width decreases or the sidewall-boundary layer thickness increases, then the spanwise extent of the core flow in the central region of the test model would shrink. While reaching a particular situation where the saddles ![]() $S_1$ and

$S_1$ and ![]() $S_{1}^{\prime }$, as well as

$S_{1}^{\prime }$, as well as ![]() $S_2$ and

$S_2$ and ![]() $S_{2}^{\prime }$, merge, the surface-flow topology would shift into the first kind of topology (figure 7a). On the other hand, if we enlarge the magnitude of the corner separation and move its onset upstream (this can be achieved by putting obstacles upstream of the SWBLI, as suggested by Xiang & Babinsky Reference Xiang and Babinsky2019), then one possible result is that only

$S_{2}^{\prime }$, merge, the surface-flow topology would shift into the first kind of topology (figure 7a). On the other hand, if we enlarge the magnitude of the corner separation and move its onset upstream (this can be achieved by putting obstacles upstream of the SWBLI, as suggested by Xiang & Babinsky Reference Xiang and Babinsky2019), then one possible result is that only ![]() $S_1$ and

$S_1$ and ![]() $S_{1}^{\prime }$ merge into one saddle, with the critical-point distribution in the reattachment region maintaining the ‘saddle–node–saddle’ configuration, which corresponds to the second kind of topology (figure 7b).

$S_{1}^{\prime }$ merge into one saddle, with the critical-point distribution in the reattachment region maintaining the ‘saddle–node–saddle’ configuration, which corresponds to the second kind of topology (figure 7b).

3.3. First kind of dual-ISWTBLI

In this subsection, the experimental results of dual-ISWTBLIs with shock distance ![]() $d = 0$, i.e. the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI, are analysed in comparison with the single-ISWTBLIs under an identical total deflection angle. According to the schlieren images in figure 9, the development rate of the turbulent boundary layer could be estimated roughly to be 0.12 % mm

$d = 0$, i.e. the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI, are analysed in comparison with the single-ISWTBLIs under an identical total deflection angle. According to the schlieren images in figure 9, the development rate of the turbulent boundary layer could be estimated roughly to be 0.12 % mm![]() $^{-1}$, so the variation in the boundary layer thickness owing to the movement of the shock impingement point (

$^{-1}$, so the variation in the boundary layer thickness owing to the movement of the shock impingement point (![]() $\Delta x \approx 10$ mm) in the single-ISWTBLI and dual-ISWTBLI is neglected.

$\Delta x \approx 10$ mm) in the single-ISWTBLI and dual-ISWTBLI is neglected.

Figure 9. Flow features of the three groups of comparative experiments: (a) ![]() $\alpha _t=10^\circ$; (b)

$\alpha _t=10^\circ$; (b) ![]() $\alpha _t=11^\circ$; (c)

$\alpha _t=11^\circ$; (c) ![]() $\alpha _t=12^\circ$.

$\alpha _t=12^\circ$.

Based on the value of total deflection angle ![]() $\alpha _t$, cases 1–7 can be divided into three groups: case 1, A10, and case 7, A5B5d0, with

$\alpha _t$, cases 1–7 can be divided into three groups: case 1, A10, and case 7, A5B5d0, with ![]() $\alpha _t = 10^\circ$; case 2, A11, and case 6, A6B5d0, with

$\alpha _t = 10^\circ$; case 2, A11, and case 6, A6B5d0, with ![]() $\alpha _t = 11^\circ$; case 3, A12, case 4, A5B7d0, and case 5, A7B5d0, with

$\alpha _t = 11^\circ$; case 3, A12, case 4, A5B7d0, and case 5, A7B5d0, with ![]() $\alpha _t = 12^\circ$. Figures 9 and 10 show the comparison results between single-ISWTBLI and the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI in terms of schlieren images, centreline pressure distribution and surface oil-flow visualisation in all three groups. Since the topological structures are nearly symmetric about the centreline, the oil-flow images of the experiments are half-displayed in figure 10. From a visual perspective, the shock-induced separations in the first kind of dual-ISWTBLIs exhibit a similar triangle-like shape as the single-ISWTBLI with identical

$\alpha _t = 12^\circ$. Figures 9 and 10 show the comparison results between single-ISWTBLI and the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI in terms of schlieren images, centreline pressure distribution and surface oil-flow visualisation in all three groups. Since the topological structures are nearly symmetric about the centreline, the oil-flow images of the experiments are half-displayed in figure 10. From a visual perspective, the shock-induced separations in the first kind of dual-ISWTBLIs exhibit a similar triangle-like shape as the single-ISWTBLI with identical ![]() $\alpha _t$, and the surface topological structures in the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI are nearly identical to those in the corresponding single-ISWTBLI. For quantitative analysis, the extents of the separation region in each case are obtained according to the surface oil-flow images. Owing to the curvature of the separation and reattachment lines, their averaged locations are obtained logically along the spanwise direction. All relevant parameters are listed in table 3, where

$\alpha _t$, and the surface topological structures in the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI are nearly identical to those in the corresponding single-ISWTBLI. For quantitative analysis, the extents of the separation region in each case are obtained according to the surface oil-flow images. Owing to the curvature of the separation and reattachment lines, their averaged locations are obtained logically along the spanwise direction. All relevant parameters are listed in table 3, where ![]() $x_{s,cl}$,

$x_{s,cl}$, ![]() $\overline {x_{s}}$,

$\overline {x_{s}}$, ![]() $x_{r,cl}$,

$x_{r,cl}$, ![]() $\overline {x_{r}}$,

$\overline {x_{r}}$, ![]() $L_{int}$ and

$L_{int}$ and ![]() $L_{sep}$ denote the separation position on the centreline, spanwise-averaged separation position, reattachment position on the centreline, spanwise-averaged reattachment position, averaged upstream interaction length and averaged overall separation length, respectively. The values of

$L_{sep}$ denote the separation position on the centreline, spanwise-averaged separation position, reattachment position on the centreline, spanwise-averaged reattachment position, averaged upstream interaction length and averaged overall separation length, respectively. The values of ![]() $L_{int}$ and

$L_{int}$ and ![]() $L_{sep}$ are calculated using the relations

$L_{sep}$ are calculated using the relations ![]() $L_{int} = x_{O1} - \overline {x_{s}}$ and

$L_{int} = x_{O1} - \overline {x_{s}}$ and ![]() $L_{sep} = \overline {x_{r}} - \overline {x_{s}}$ (where

$L_{sep} = \overline {x_{r}} - \overline {x_{s}}$ (where ![]() $x_{O1} = 0$ in this study). Based on table 3, we find that the variation in

$x_{O1} = 0$ in this study). Based on table 3, we find that the variation in ![]() $L_{int}$ between the single-ISWTBLI and the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI in each group is no more than 0.5 mm (

$L_{int}$ between the single-ISWTBLI and the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI in each group is no more than 0.5 mm (![]() ${\sim }1\,\% L_{int}$). By contrast, the reattachment position in the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI is slightly downstream of that in single-ISWTBLI in all three groups. Despite this, the pressure distribution of the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI and the corresponding single-ISWTBLI coincide approximately in the region upstream of the reattachment point (shown in figure 9). Note that the pressure distribution discrepancy downstream of the reattachment point is attributed mainly to the different impingement positions of the expansion fan emanating from the shock-generator tail. Nevertheless, the primary focus of this paper is on the features of the separation region; hence the variations observed downstream of the reattachment point are not within the scope of this study.

${\sim }1\,\% L_{int}$). By contrast, the reattachment position in the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI is slightly downstream of that in single-ISWTBLI in all three groups. Despite this, the pressure distribution of the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI and the corresponding single-ISWTBLI coincide approximately in the region upstream of the reattachment point (shown in figure 9). Note that the pressure distribution discrepancy downstream of the reattachment point is attributed mainly to the different impingement positions of the expansion fan emanating from the shock-generator tail. Nevertheless, the primary focus of this paper is on the features of the separation region; hence the variations observed downstream of the reattachment point are not within the scope of this study.

Figure 10. Comparison of surface-flow topologies in single-ISWTBLI and dual-ISWTBLI. (a) ![]() $\alpha _t=10^\circ$; the top half is case 1, A10; the bottom half is case 7, A5B5d0. (b)

$\alpha _t=10^\circ$; the top half is case 1, A10; the bottom half is case 7, A5B5d0. (b) ![]() $\alpha _t=11^\circ$; the top half is case 2, A11; the bottom half is case 6, A6B5d0. (c)

$\alpha _t=11^\circ$; the top half is case 2, A11; the bottom half is case 6, A6B5d0. (c) ![]() $\alpha _t=12^\circ$; the top half is case 3, A12; the bottom half is case 4, A5B7d0. (d)

$\alpha _t=12^\circ$; the top half is case 3, A12; the bottom half is case 4, A5B7d0. (d) ![]() $\alpha _t=12^\circ$; the top half is case 3, A12; the bottom half is case 5, A7B5d0. The purple, red and blue dashed lines indicate the locations of the first inviscid impingement point, the separation point and the reattachment point on the centreline, respectively.

$\alpha _t=12^\circ$; the top half is case 3, A12; the bottom half is case 5, A7B5d0. The purple, red and blue dashed lines indicate the locations of the first inviscid impingement point, the separation point and the reattachment point on the centreline, respectively.

Table 3. Separation-related parameters in cases 1–7.

Based on the aforementioned observations, it can be concluded that except for the shock waves inducing the separation, various flow features in the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI, including the extent and shape of the separation bubble, pressure distribution and surface-flow topology, are nearly the same as those in the single-ISWTBLI with an identical total deflection angle.

3.4. Second kind of dual-ISWTBLI

The IC-PLS images in figure 1 show qualitatively that the size and shape of the separation bubble changed with the increase in the shock distance (![]() $d$). In the experiments presented in this subsection,

$d$). In the experiments presented in this subsection, ![]() $d$ was set to a moderate value to induce the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI with a quadrilateral-like separation. Also, two combinations of the deflection angles, (

$d$ was set to a moderate value to induce the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI with a quadrilateral-like separation. Also, two combinations of the deflection angles, (![]() $\alpha _1 = 7^\circ$,

$\alpha _1 = 7^\circ$, ![]() $\alpha _2 = 5^\circ$) and (

$\alpha _2 = 5^\circ$) and (![]() $\alpha _1 = 5^\circ$,

$\alpha _1 = 5^\circ$, ![]() $\alpha _2 = 7^\circ$), were employed to examine the effect of the ISWs arrangement on the quadrilateral-like separation bubble.

$\alpha _2 = 7^\circ$), were employed to examine the effect of the ISWs arrangement on the quadrilateral-like separation bubble.

As defined in § 2.2, the origin of the ![]() $x$-axis was set at the first impingement point

$x$-axis was set at the first impingement point ![]() $O_1$, which was fixed in the dual-ISWTBLI experiments, so the increase in

$O_1$, which was fixed in the dual-ISWTBLI experiments, so the increase in ![]() $d$ was achieved by moving the second ISW downstream. The values of

$d$ was achieved by moving the second ISW downstream. The values of ![]() $d$ in cases 8 and 9 were set to 22.5 mm and 19.0 mm, respectively. For comparative purposes, the schlieren images of the first and second kinds of dual-ISWTBLIs are presented in figure 11, with the separation region encircled by the yellow dashed line. The pressure distributions and surface oil-flow images are shown in figures 12 and 13, respectively. The related parameters of the separation region, extracted from the experimental results, are listed in table 4. Compared with the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI, a direct consequence of increasing

$d$ in cases 8 and 9 were set to 22.5 mm and 19.0 mm, respectively. For comparative purposes, the schlieren images of the first and second kinds of dual-ISWTBLIs are presented in figure 11, with the separation region encircled by the yellow dashed line. The pressure distributions and surface oil-flow images are shown in figures 12 and 13, respectively. The related parameters of the separation region, extracted from the experimental results, are listed in table 4. Compared with the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI, a direct consequence of increasing ![]() $d$ in the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI is that the adverse pressure gradient on the boundary layer decreases and the upstream interaction length accordingly diminishes. Compared with the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI in case 4, the separation point on the centreline in case 8 moves 18.1 mm downstream from

$d$ in the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI is that the adverse pressure gradient on the boundary layer decreases and the upstream interaction length accordingly diminishes. Compared with the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI in case 4, the separation point on the centreline in case 8 moves 18.1 mm downstream from ![]() $x_{s,cl} = -56.9$ mm to

$x_{s,cl} = -56.9$ mm to ![]() $-38.8$ mm. Similarly, the separation point on the centreline in case 9 is located 11.8 mm downstream of that in case 5, moving from

$-38.8$ mm. Similarly, the separation point on the centreline in case 9 is located 11.8 mm downstream of that in case 5, moving from ![]() $x_{s,cl} = -56.8$ mm to

$x_{s,cl} = -56.8$ mm to ![]() $-45.0$ mm. In addition, the decrease in separation-bubble height (indicated by the pink dashed line in figure 11) in the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI can be observed easily. Moreover, we find that the shock wave system in the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI is more complicated than that in the first kind. The two ISWs reflect on the shear layer, which could be regarded approximately as the isobaric boundary (Babinsky & Harvey Reference Babinsky and Harvey2011), forming two central expansion waves and concurrently leading to two remarkable turnings of the main flow; thus a quadrilateral-like separation bubble appeared. Closer inspection reveals that the flow directions of the upper shear layer of the separation bubble between the two expansion fans in cases 8 and 9 are upwards and downwards, respectively; in other words, the apex of the quadrilateral-like separation bubble in the two cases is located at the downstream and upstream vertex, respectively.

$-45.0$ mm. In addition, the decrease in separation-bubble height (indicated by the pink dashed line in figure 11) in the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI can be observed easily. Moreover, we find that the shock wave system in the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI is more complicated than that in the first kind. The two ISWs reflect on the shear layer, which could be regarded approximately as the isobaric boundary (Babinsky & Harvey Reference Babinsky and Harvey2011), forming two central expansion waves and concurrently leading to two remarkable turnings of the main flow; thus a quadrilateral-like separation bubble appeared. Closer inspection reveals that the flow directions of the upper shear layer of the separation bubble between the two expansion fans in cases 8 and 9 are upwards and downwards, respectively; in other words, the apex of the quadrilateral-like separation bubble in the two cases is located at the downstream and upstream vertex, respectively.

Figure 11. Schlieren images of the two kinds of dual-ISWTBLIs. (a) Case 4, A5B7d0. (b) Case 8, A5B7d22.5. (c) Case 5, A7B5d0. (d) Case 9, A7B5d19.0.

Figure 12. Pressure distribution of the two kinds of dual-ISWTBLIs.

Figure 13. Surface topologies of the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI. (a) Case 8, A5B7d22.5. (b) Case 9, A7B5d19.0. The purple, red and blue dashed lines indicate the locations of the first inviscid impingement point, the separation point and the reattachment point on the centreline, respectively.

Table 4. Separation-related parameters in cases 8 and 9.

As for the surface-flow topology, the distribution of critical points in the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI is still similar to that in the first kind. We find that the critical points between the separation and reattachment nodes, i.e. the focus (![]() $F_2, F_{2}^{\prime }$) and the saddles (

$F_2, F_{2}^{\prime }$) and the saddles (![]() $S_3, S_4$), are more visible. However, although the upstream interaction length decreases as the second ISW moves downstream, the reattachment line concurrently migrates downstream. Compared with cases 4 and 5, the overall separation length in cases 8 and 9 increases by 7.4 mm and 5.2 mm, respectively. Therefore, we can consider that as the shock distance increases, the separation height diminishes, whereas the extent of the reversed-flow region is elongated.

$S_3, S_4$), are more visible. However, although the upstream interaction length decreases as the second ISW moves downstream, the reattachment line concurrently migrates downstream. Compared with cases 4 and 5, the overall separation length in cases 8 and 9 increases by 7.4 mm and 5.2 mm, respectively. Therefore, we can consider that as the shock distance increases, the separation height diminishes, whereas the extent of the reversed-flow region is elongated.

4. Discussion

The experimental results provided some insights into the overall flow configurations in dual-ISWTBLIs, especially in terms of the shape and interaction length of the separation region. In this section, the experimentally observed phenomenon will be analysed further by theoretical methods. In § 4.1, an inviscid model is established to describe the shock wave system of dual-ISWTBLIs, by which the related influencing factors on the shape of the separation bubble are analysed. Also, based on the previous research on single-ISWTBLIs (Souverein et al. Reference Souverein, Bakker and Dupont2013), a scaling analysis of the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI (![]() $d = 0$) is presented in § 4.2. However, because the experimental data are limited, it is difficult to consider the shock distance while establishing the scaling model; thus the scaling analysis on the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI is not performed in this paper.

$d = 0$) is presented in § 4.2. However, because the experimental data are limited, it is difficult to consider the shock distance while establishing the scaling model; thus the scaling analysis on the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI is not performed in this paper.

4.1. Inviscid model for dual-ISWTBLI

Although the viscous effect plays a paramount role in SWBLIs, Délery, Marvin & Reshotko (Reference Délery, Marvin and Reshotko1986) developed an inviscid model for SWBLIs that is widely used in the literature to describe the shock waves involved (Babinsky & Harvey Reference Babinsky and Harvey2011; Matheis & Hickel Reference Matheis and Hickel2015; Grossman & Bruce Reference Grossman and Bruce2018). In their work, SWBLI was equivalent to an ideal flow with an outer ‘inviscid flow’ and the viscous separated boundary layer flow. Figure 14 is a schematic illustration of the inviscid model for the single-ISWTBLI, which was described in the textbook of Babinsky & Harvey (Reference Babinsky and Harvey2011). In this inviscid model, the separation region is replaced by an isobaric-dead air region. The interface between the viscous and inviscid flows is equivalent to an isobaric line. More specifically, the separation bubble is modelled as a fictitious triangular wedge. The airflow is deflected by a deflection angle at the separation point ![]() $S$, inducing the separation shock (shock 2). The separation shock intersects the incident shock (shock 1) at intersection

$S$, inducing the separation shock (shock 2). The separation shock intersects the incident shock (shock 1) at intersection ![]() $I$, producing the transmitted shocks (shocks 3 and 4). Shock 4 impinges the isobaric border at point

$I$, producing the transmitted shocks (shocks 3 and 4). Shock 4 impinges the isobaric border at point ![]() $T$, from which a central expansion fan emanates to compensate for the pressure rise caused by shock 4. Then the airflow deflects towards the wall along with the isobaric border

$T$, from which a central expansion fan emanates to compensate for the pressure rise caused by shock 4. Then the airflow deflects towards the wall along with the isobaric border ![]() $T-R$ and impacts the wall at the ‘inviscid’ reattachment point

$T-R$ and impacts the wall at the ‘inviscid’ reattachment point ![]() $R$. Thereafter, a deflection of the airflow occurs, accompanied by the generation of the reattachment shock (shock 5). To some extent, the inviscid simplification is beneficial for depicting clearly the complex wave system; hence, based on this model, we could achieve a deep understanding of the macroscopic mean separated flow in the single-ISWTBLI.

$R$. Thereafter, a deflection of the airflow occurs, accompanied by the generation of the reattachment shock (shock 5). To some extent, the inviscid simplification is beneficial for depicting clearly the complex wave system; hence, based on this model, we could achieve a deep understanding of the macroscopic mean separated flow in the single-ISWTBLI.

Figure 14. Schematic illustration of the inviscid model for the single-ISWTBLI (referring to the textbook of Babinsky & Harvey Reference Babinsky and Harvey2011).

4.1.1. Pressure estimation in the isobaric-dead air region

The core assumption for establishing the simplified inviscid model for the ISWTBLIs is replacing the separation bubble with an isobaric-dead air region. Consequently, the estimation of the static pressure in the isobaric region is of great significance. As mentioned in § 3.2, for a strong boundary layer separation, the overall pressure-rise process is divided into two stages, and the plateau pressure (after the first stage) can be regarded as the pressure of the isobaric-dead air region (Babinsky & Harvey Reference Babinsky and Harvey2011; Matheis & Hickel Reference Matheis and Hickel2015). Over the past decades, a convincing method for estimating the plateau pressure is the free-interaction theory (FIT) proposed by Chapman et al. (Reference Chapman, Kuehn and Larson1957). The theory states that the initial pressure rise at the separation is related to the properties of only the upstream undisturbed boundary layer rather than the shock wave systems imparting the adverse pressure gradient. Further, Erdos & Pallone (Reference Erdos and Pallone1962) suggested that the pressure rise during the free-interaction process can be expressed as

\begin{equation} \frac{p(s)-p_{0}}{q_{0}}=F(s) \sqrt{\frac{2 C_{f, 0}}{(M a_{0}^{2}-1)^{1 / 2}}} , \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac{p(s)-p_{0}}{q_{0}}=F(s) \sqrt{\frac{2 C_{f, 0}}{(M a_{0}^{2}-1)^{1 / 2}}} , \end{equation}

where ![]() $F(s)$ is a universal correlation function, defined as

$F(s)$ is a universal correlation function, defined as

with

where ![]() $\tau$ is the wall shear stress,

$\tau$ is the wall shear stress, ![]() $\tau _{w0}$ is the wall shear stress at the onset of the interaction region,

$\tau _{w0}$ is the wall shear stress at the onset of the interaction region, ![]() $\delta ^{*}$ is the displacement thickness of the boundary layer,

$\delta ^{*}$ is the displacement thickness of the boundary layer, ![]() $x_0$ is the streamwise coordinate of the onset of the interaction region,

$x_0$ is the streamwise coordinate of the onset of the interaction region, ![]() $l$ is the characteristic length of the free interaction and

$l$ is the characteristic length of the free interaction and ![]() $s$ is the normalised streamwise coordinate.

$s$ is the normalised streamwise coordinate.

The universal correlation function ![]() $F(s)$ in the large-scale shock-induced separation of turbulent boundary layer has been estimated experimentally by Erdos & Pallone (Reference Erdos and Pallone1962), which is depicted by the solid black line in figure 15, indicating that

$F(s)$ in the large-scale shock-induced separation of turbulent boundary layer has been estimated experimentally by Erdos & Pallone (Reference Erdos and Pallone1962), which is depicted by the solid black line in figure 15, indicating that ![]() $F(s)$ values corresponding to the separation point and pressure plateau were 4.22 and 6.0, respectively. According to (4.1), the function

$F(s)$ values corresponding to the separation point and pressure plateau were 4.22 and 6.0, respectively. According to (4.1), the function ![]() $F(s)$ is acquired in all nine cases in the current study. It is noteworthy that the characteristic length

$F(s)$ is acquired in all nine cases in the current study. It is noteworthy that the characteristic length ![]() $l$ for normalisation is estimated by

$l$ for normalisation is estimated by ![]() $l = x_{ref} - x_{0}$, where

$l = x_{ref} - x_{0}$, where ![]() $x_{ref}$ is the coordinate at which

$x_{ref}$ is the coordinate at which ![]() $F(s) = 4.22$. Such a selection of

$F(s) = 4.22$. Such a selection of ![]() $l$ is for conveniently comparing the

$l$ is for conveniently comparing the ![]() $F(s)$ profiles between this study and the work by Erdos & Pallone (Reference Erdos and Pallone1962). As shown in figure 15, the

$F(s)$ profiles between this study and the work by Erdos & Pallone (Reference Erdos and Pallone1962). As shown in figure 15, the ![]() $F(s)$ profiles in the nine cases are nearly superposable before approaching the plateau value. Separation values

$F(s)$ profiles in the nine cases are nearly superposable before approaching the plateau value. Separation values ![]() $F(s)_{separation}$ evaluated experimentally in the cases are in the range 3.62–4.38 with average 3.90, which is close to 4.22. Also, the plateau values

$F(s)_{separation}$ evaluated experimentally in the cases are in the range 3.62–4.38 with average 3.90, which is close to 4.22. Also, the plateau values ![]() $F(s)_{plateau}$ in the tests of both single-ISWTBLIs and dual-ISWTBLIs are approximately 6.0, which agrees well with the result reported by Erdos & Pallone (Reference Erdos and Pallone1962). These results reconfirmed that the pressure rise during the free interaction is determined only by the upstream flow conditions, including the free-stream Mach number and boundary layer features, rather than the outer shock wave system (single-ISW or dual-ISWs) inducing the separation. Consequently, the FIT could also be used to estimate the plateau pressure in the dual-ISWTBLIs with large-scale separations.

$F(s)_{plateau}$ in the tests of both single-ISWTBLIs and dual-ISWTBLIs are approximately 6.0, which agrees well with the result reported by Erdos & Pallone (Reference Erdos and Pallone1962). These results reconfirmed that the pressure rise during the free interaction is determined only by the upstream flow conditions, including the free-stream Mach number and boundary layer features, rather than the outer shock wave system (single-ISW or dual-ISWs) inducing the separation. Consequently, the FIT could also be used to estimate the plateau pressure in the dual-ISWTBLIs with large-scale separations.

Figure 15. Universal correlation function ![]() $F(s)$ evaluated from cases 1–9. Separation values

$F(s)$ evaluated from cases 1–9. Separation values ![]() $F(s)_{separation}$ are annotated by dash-dot lines.

$F(s)_{separation}$ are annotated by dash-dot lines.

4.1.2. Inviscid model and shock wave system in dual-ISWTBLI

In the previous work by Li et al. (Reference Li, Tan, Zhang, Huang, Guo and Lin2020), the shock wave system in dual-ISWTBLIs was described briefly via an inviscid model. Figure 16(a) depicts a general inviscid model for the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI. Shocks ![]() $C_1$ and

$C_1$ and ![]() $C_2$ are the two ISWs, and the blue region represents the modelled separation bubble, which is viewed as an isobaric region with constant pressure

$C_2$ are the two ISWs, and the blue region represents the modelled separation bubble, which is viewed as an isobaric region with constant pressure ![]() $p_{p}$ (the plateau pressure). The initial part of the separation bubble is equivalent to an isobaric line with an inclination angle, which induces the separation shock wave

$p_{p}$ (the plateau pressure). The initial part of the separation bubble is equivalent to an isobaric line with an inclination angle, which induces the separation shock wave ![]() $C_3$. Shock waves

$C_3$. Shock waves ![]() $C_1$ and

$C_1$ and ![]() $C_3$ intersect at

$C_3$ intersect at ![]() $I_1$ and then generate the transmitted shock waves

$I_1$ and then generate the transmitted shock waves ![]() $C_4$ and

$C_4$ and ![]() $C_5$, respectively.

$C_5$, respectively. ![]() $C_5$ intersects the isobaric region at point

$C_5$ intersects the isobaric region at point ![]() $T_1$. Owing to the isobaric nature of the isobaric region, a central expansion fan

$T_1$. Owing to the isobaric nature of the isobaric region, a central expansion fan ![]() $E_1$ emanates from

$E_1$ emanates from ![]() $T_1$ to counteract the pressure rise provoked by

$T_1$ to counteract the pressure rise provoked by ![]() $C_5$. This process makes the airflow deflect and then travel along the isobaric line

$C_5$. This process makes the airflow deflect and then travel along the isobaric line ![]() $T_1-T_2$. Similarly,

$T_1-T_2$. Similarly, ![]() $C_2$ and

$C_2$ and ![]() $C_4$ intersect at

$C_4$ intersect at ![]() $I_2$ and produce the transmitted shock waves

$I_2$ and produce the transmitted shock waves ![]() $C_6$ and

$C_6$ and ![]() $C_7$, respectively. Shock wave

$C_7$, respectively. Shock wave ![]() $C_7$ penetrates the first central expansion fan

$C_7$ penetrates the first central expansion fan ![]() $E_1$ and transforms into shock wave

$E_1$ and transforms into shock wave ![]() $C_8$, which impacts the isobaric border at point

$C_8$, which impacts the isobaric border at point ![]() $T_2$. In order to balance the pressure rise caused by

$T_2$. In order to balance the pressure rise caused by ![]() $C_8$, the second central expansion fan

$C_8$, the second central expansion fan ![]() $E_2$ emanates from point

$E_2$ emanates from point ![]() $T_2$. Thereafter, the airflow turns towards the wall, along the isobaric line

$T_2$. Thereafter, the airflow turns towards the wall, along the isobaric line ![]() $T_2-R$, and then impacts the wall at the reattachment point

$T_2-R$, and then impacts the wall at the reattachment point ![]() $R$, where the reattachment shock wave,

$R$, where the reattachment shock wave, ![]() $C_9$, originated. It should be noted that at intersections

$C_9$, originated. It should be noted that at intersections ![]() $I_1$ and

$I_1$ and ![]() $I_2$, we consider only the most commonly encountered regular shock reflection, i.e. Edney type-I interference (Edney Reference Edney1968), and the two Edney type-I interferences induce two slip lines, across which the fluid properties are discontinuous. Consequently, according to the inviscid model, a wave system of the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI comprising nine shock waves (

$I_2$, we consider only the most commonly encountered regular shock reflection, i.e. Edney type-I interference (Edney Reference Edney1968), and the two Edney type-I interferences induce two slip lines, across which the fluid properties are discontinuous. Consequently, according to the inviscid model, a wave system of the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI comprising nine shock waves (![]() $C_1$–

$C_1$–![]() $C_9$) and two central expansion fans (

$C_9$) and two central expansion fans (![]() $E_1$ and

$E_1$ and ![]() $E_2$) is obtained.

$E_2$) is obtained.

Figure 16. Inviscid model for dual-ISWTBLIs: (a) the second kind of dual-ISWTBLI; (b) the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI.

As for the first kind of dual-ISWTBLI, the two intersection points, ![]() $T_1$ and

$T_1$ and ![]() $T_2$, are very close, so they could be regarded as one point (figure 16b). As a result, the two central expansion fans merge into one, and the separation bubble presents a triangle-like shape, nearly consistent with the separation bubble observed in the single-ISWTBLIs.

$T_2$, are very close, so they could be regarded as one point (figure 16b). As a result, the two central expansion fans merge into one, and the separation bubble presents a triangle-like shape, nearly consistent with the separation bubble observed in the single-ISWTBLIs.

4.1.3 Influencing factors of the quadrilateral-like separation bubble

The experimental results in figure 11 show that when the combination of the deflection angles changed from (![]() $\alpha _1 = 5^\circ$,

$\alpha _1 = 5^\circ$, ![]() $\alpha _2 = 7^\circ$) to (

$\alpha _2 = 7^\circ$) to (![]() $\alpha _1 = 7^\circ$,

$\alpha _1 = 7^\circ$, ![]() $\alpha _2 = 5^\circ$), the flow direction of the upper shear layer of the separation bubble, corresponding to the isobaric line