While debate persists on the broader relationship between regime type and terrorism, there is a relative consensus that powerful authoritarian governments possess an important counterterrorism tool – the ability to control information.Footnote 1 A defining feature of terrorism is that it is ‘designed to have far-reaching psychological repercussions beyond the immediate victim or target’ (Hoffman Reference Hoffman2006, 43). In mass societies, terrorism accomplishes this goal by leveraging the media to convey knowledge of attacks to the broader public (Atkinson, Sandler and Tschirhart Reference Atkinson, Sandler and Tschirhart1987; Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1981; Sandler, Tschirhart and Cauley Reference Sandler, Tschirhart and Cauley1983; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2001). Recognizing this, Margaret Thatcher famously asked the British media to stop providing terrorists with the ‘oxygen of publicity’ (Apple Reference Apple1985, A3). Her pleas were, however, largely futile: comprehensive information control is almost definitionally impossible in democracies and media self-restraint is unlikely because terrorism so reliably excites audiences (Crelinsten Reference Crelinsten1989; Farnen Reference Farnen1990; Martin Reference Martin1985; Rohner and Frey Reference Rohner and Frey2007; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson1997). Autocracies are widely assumed to be much more capable of accomplishing this goal through control of the media.Footnote 2

These stylized facts, however, can be misleading when it comes to the dilemmas that many modern autocratic regimes face, particularly given the evolving technological and media environments. In institutionalized autocracies public opinion matters, information control is not absolute, media can be partially independent and market driven, and state strategies toward terrorism are therefore nuanced.Footnote 3

China is one such autocracy.Footnote 4 Government control over the reporting of terrorist attacks is explicitly written into the 2015 Counterterrorism Law that states, ‘information on the occurrence, development, and response and handling of a terrorist incident is uniformly released by the provincial leading institution on counter-terrorism work of the place where the terrorist incident occurs…no other units or individuals are allowed to disseminate details of the incidents that may lead to copycat actions, nor may they spread cruel or inhuman images of the incidents’.Footnote 5 However, despite impressive controls, China is nonetheless an increasingly developed and connected society in which information can spread organically and unpredictably through social media and other channels and the Party is deeply sensitive to public opinion and domestic pressure.Footnote 6

How, then, does the Party manage official coverage of terrorism, and what can this tell us about its sensitivities, preferences and strategies?Footnote 7 We argue that Beijing's handling of terrorism in the official media reveals a tension between long- and short-term priorities.Footnote 8 On the one hand, prompt acknowledgment in the official press can legitimize the party by demonstrating transparency and responsiveness, internationalize China's terrorism challenges and strengthen its regional relationships in Central Asia. As we will detail, transparency is increasingly important for maintaining legitimacy in institutionalized autocracies like China where citizens have some access to independent information. Similarly, under the right conditions, transparency can allow China to place its domestic terrorism challenges in the broader context of the ‘global war on terror’ and thereby shield its repressive response from international criticism. On the other hand, the high priority placed on social stability incentivizes Chinese authorities to avoid highlighting militant violence for fear that the Chinese public will either blame the government for it or demand that the government responds in ways that it deems suboptimal. The question is: under what conditions do each of these impulses prevail?

To better understand the strategic considerations that govern this decision, we develop event history models of ‘time to official acknowledgment’ after terrorist incidents. Drawing on original, comprehensive datasets of all known Uyghur terrorist violence and the timing of official coverage in the People's Daily, we demonstrate that the official press promptly acknowledges terrorist incidents when the domestic economy is thriving and China enjoys diplomatic support abroad.Footnote 9 We establish the robustness of this finding with a variety of alternative operationalizations of domestic and international conditions, including natural disasters and composite measures of domestic and international conditions generated from machine-coded events data.

Regardless of the particular operationalization, we see prompt acknowledgment of terrorist incidents in the People's Daily only when both international and domestic conditions are favorable. When domestic conditions are broadly favorable, Chinese citizens are less likely to challenge the government's handling of terrorism; if some do, the government is better positioned to tolerate the dissent. When international diplomatic conditions are favorable, China is less likely to face external criticism of its minority policy, which in turn could further inflame public opinion. Only when both conditions hold are authorities sufficiently confident that the investment in longer-term legitimacy that accompanies transparency will not threaten the Party's immediate grip on power and individual officials' paths toward promotion. In contrast, when these conditions are not in place, delays give the authorities time to gauge the political sensitivities of the moment and the impact of the incident.

These findings contradict the rival possibility that Chinese authorities might systematically use their control of the media to stoke fear of terrorism (or the nationalist sentiments it tends to provoke) as a diversionary tactic. They also contribute to a growing body of work on China's policies toward media censorship, propaganda and collective action (Huang, Boranbay-Akan and Huang Reference Huang, Boranbay-Akan and Huang2019; King, Pan and Roberts Reference King, Pan and Roberts2013; Stockmann and Gallagher Reference Stockmann and Gallagher2011; Weiss Reference Weiss2014). The patterns that we uncover reveal a complementary but underappreciated element of Chinese authorities' information strategy: they seek to control uncertainty. When an unfavorable political environment makes it unclear how the public will react to a potentially inflammatory piece of information, the Chinese authorities are less willing to risk transparency, even when the long-term rewards might be high.

The remainder of the article proceeds in five sections. We begin by discussing the nature of terrorism in China and introducing comprehensive data on Uyghur-related terrorist incidents. We then clarify the rewards and risks (for the CCP) of prompt transparency in the official media. Leveraging the aforementioned data on terrorist incidents and time to coverage, we find that prompt acknowledgment of terrorist incidents in the official media is most likely when both international and domestic conditions are favorable. We conclude with a discussion of the implications of these findings for China, the globe and our understanding of the relationship between terrorism and regime type.

Terrorism in China

China's experiences with (and policies related to) domestic ethnic unrest have evolved substantially since the end of WWII. Maoist policy was often heavy handed, with substantial crackdowns on minority populations from Inner Mongolia to Tibet (Bovingdon Reference Bovingdon2010; Goldstein Reference Goldstein1991; Lai Reference Lai2009).Footnote 10 Xinjiang, however, was largely an afterthought during this period; Uyghurs fared somewhat better than many other minorities due to the region's remoteness and relative quiescence (Zhao Reference Zhao2010).Footnote 11 Whereas Tibet figured prominently in the ongoing rivalry with India, the USSR, for the most part, shared an interest in suppressing nationalist sentiments among the ethnic Turkic populations in Central Asia (Luong Reference Luong2004; Martin Reference Martin2001).

Xinjiang remained a distant concern during the early phases of China's economic and political revitalization under Deng Xiaoping. However, the fall of the Soviet Union and the resulting independence of its Central Asian republics changed this dynamic by raising expectations among the Uyghur population (Gladney Reference Gladney and Frederick Starr2004a).Footnote 12 The Chinese authorities, however, drew lessons from both the Soviet breakup and their own experiences in the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 and adopted a hard line against any increase in autonomy (Gladney Reference Gladney and Frederick Starr2004b; Rudelson and Jankowiak Reference Rudelson, Jankowiak and Frederick Starr2004). This stance has not softened: an overwhelming police presence, harsh crackdowns, cultural assimilation programs and Han in-migration are now the norm in the region. The result is the present status quo of simmering tension punctuated by sporadic violence (Cao et al. Reference Cao2018a; Cao et al. Reference Cao2018b; Clarke Reference Clarke2018).

To establish the scope of this violence, we developed a dataset of all known incidents of Uyghur-initiated terrorism in China from 1990 to 2014.Footnote 13 Figure 1, which graphs these data, indicates two distinct campaigns. The first, which arose around the initial push for autonomy after the fall of the USSR, reached its peak in 1997 when fifteen terrorist attacks resulted in fifty deaths and ninety-eight injured. The lead-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics marked the beginning of the second wave, culminating in 2014 when 164 people were killed and 426 others were injured in twenty-eight incidents. Figure 1 also indicates that the attacks have shifted over time toward increased civilian targeting, bringing it more in line with global trends.Footnote 14

Figure 1. Uyghur-initiated terrorist incidents, 1990–2014

Figure 2 graphs the average number of casualties from these attacks. In keeping with both global trends and the greater sophistication of Uyghur militant organizations in that period, the second wave was more lethal than the first (Potter Reference Potter2013). The difference amounts to three more deaths and eight more injuries per attack. However, while increasing, the number of casualties per attack remains relatively low compared to global averages. This is because weapons and tactics have been notably crude – predominantly knives and simple bombs – accounting for approximately 39 and 42 per cent of all attacks, respectively. There are, however, indications that the militants’ tactics are becoming more sophisticated, particularly with regard to the adoption of al Qaeda-style coordinated attacks and suicide bombing.Footnote 15

Figure 2. Killed and injured per attack, 1990–2014

In sum, Uyghur militant violence has been a significant issue for the Chinese government. Although the authorities have successfully limited, if not absolutely blocked, access to highly lethal weapons, the number of attacks and casualties have increased. Violence in Xinjiang is in a lull at the time of writing, well down from the 2014 highs at the end of our period of analysis, likely owing to an overwhelming security crackdown over the last 5 years. Members of a United Nations human rights committee announced in August 2018 that the Chinese government is holding as many as one million ethnic Uyghurs in ‘massive internment camps’, ‘shrouded in secrecy’ (Cumming-Bruce Reference Cumming-Bruce2018, A9).

The Long-Term Benefits of Transparency

The CCP has several good reasons to promptly acknowledge terrorist violence in its official media when it occurs, the most significant of which is legitimacy. The link between transparency and Party legitimacy is well documented in the Chinese context. Stockmann and Gallagher (Reference Stockmann and Gallagher2011), for example, note that exposure to news regarding labor disputes promotes the perception of pro-worker bias in the law among Chinese citizens, which helps increase the Party's popular legitimacy.Footnote 16 Similarly, Huang, Boranbay-Akan and Huang (Reference Huang, Boranbay-Akan and Huang2019) link media acknowledgment of social protests to enhanced claims of Party legitimacy.

Transparency regarding protests can increase CCP legitimacy in part because it can be spun as the government is stepping in to protect the rights of the aggrieved. The mechanism driving legitimacy gains from transparency with regard to terrorism is similar but works through two distinct channels. First, prompt acknowledgement can improve legitimacy even when the fault lies unambiguously with the government for failing to protect citizens. As the adage goes, the coverup can be worse than the crime, and if a government error will eventually come to light, owning it at the outset is often the best way to mitigate the downside by at least maintaining legitimacy as an honest provider of information. However, in the context of counterterrorism, blame is rarely that clear. It can also be the case that the government has an opportunity to reap positive rewards (not just mitigate negative repercussions) by quickly acknowledging a terrorist attack. As is the case with labor disputes and social protests, here too the government can portray itself as stepping in to protect the vulnerable and the aggrieved by increasing security and policing as well as arresting and punishing the perpetrators. Such framing tends to be effective because the Han majority in China generally blames Uyghurs rather than the government for the violence. Indeed, terrorist attacks can lead to upsurges in nationalist sentiment that can rally support for the government. However, the government cannot always tell which of these scenarios is more likely to play out (or whether the situation will turn entirely negative), hence the imperative for caution even in the face of potential rewards for transparency.

This is more than an academic insight. The CCP has grown increasingly explicit in the linkage that it draws between transparency and legitimacy and is clearly cognizant of the positive returns that can accompany quick official acknowledgment of negative events. Such transparency is described as essential to avoiding the ‘Tacitus Trap’ – a term used in Chinese policy circles as shorthand for a permanent loss of credibility, as its every subsequent action is viewed as a lie once an unknown reputation threshold has been crossed.Footnote 17 The most recent wave of intensive discussion of this trap arose in the context of a kindergarten abuse scandal at the end of 2017, in which the government was widely blamed by Chinese ‘netizens’ for failing to release enough information about the investigation process in a timely manner (Quackenbush Reference Quackenbush2017). In an enlarged meeting of the Lankao County Party Committee on 14 March 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping highlighted this concern, saying, ‘we are certainly not there [falling into the Tacitus Trap] yet, but the current problem facing us is not trivial either; if that day really comes, then the Party's legitimacy foundations and power status will be threatened’.Footnote 18

The failure to officially acknowledge high-profile incidents has proven costly in some key cases. The school collapses in the Sichuan earthquake, the 2011 high-speed rail accident, and recent events surrounding the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan are prominent illustrations of the downside risks of reticence to engage on issues of high salience to the public.Footnote 19 These costs increase as it becomes easier for Chinese citizens to determine when the government is not talking about particular issues. Media fragmentation and semi-privatization, as well as the emergence of social media, contribute to a ‘leaky’ information environment in which the government might forgo discussion of an incident in the official media, but it may still reach segments of the public. Gaps between what official voices choose to engage with and what the people are concerned about can contribute to the erosion of legitimacy (Lorentzen Reference Lorentzen2014). It is therefore important not just that information is released, but that the government is seen to be the source and conveyor of that information – hence the significance of acknowledgment in the official press. While it is broadly understood that the party heavily influences what is and is not discussed in the semi-private press, official acknowledgment sends a distinct and important signal.

International priorities can also favor rapid transparency with regard to terrorism because such incidents are more likely to receive prominent global attention. In the post-9/11 context, there are potential long-term benefits that arise from internationalizing domestic terrorism emanating from Xinjiang by linking it to global counterterrorism efforts and thereby insulating China's policies from criticism (Potter Reference Potter2013). The global fixation on militant Islamist movements provides a useful and easy rhetorical frame for Uyghur violence – this is, after all, a Muslim minority bordering Afghanistan in the heart of central Asia.Footnote 20 Credible condemnation of China's repressive policies (particularly by the United States) is difficult if the situation in Xinjiang can be successfully framed in terms of terrorism and international jihadist movements. International attentiveness to terrorism in China is, however, generally short-lived; thus authorities risk wasting an opportunity if they obscure an incident by delaying official acknowledgment.

Highlighting terrorism in the official media also legitimizes China's expansive military, political and economic ambitions in Central Asia. Beijing's presence in the region has always had the potential to be viewed as aggressive and expansionist. To combat this possibility, China draws on the threat of terrorism and the promise of counterterrorism co-operation to justify its policies in the region and frame them in a more positive light. For example, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) was formed with the explicit mandate to fight against the ‘three evils’ of separatism, fundamentalism and terrorism (Chung Reference Chung2004). Thus it is rhetorically useful for the Chinese government to promptly and officially acknowledge terrorist attacks in order to highlight the severity of these three evils and bolster the SCO as a nascent collective security institution: shared experience of terrorism, and transparent treatment of that experience, can help make the case that the threat is real. This is particularly important because, while the three evils are the stated justification for the organization's existence, there is suspicion that China's regional policy is actually driven by a desire for regional hegemony (Cohen Reference Cohen2006; Swanström Reference Swanström2005).

The Short-Term Risks of Transparency

However, there remain strong countervailing incentives for leaders to delay the acknowledgment of terrorist incidents in the official media until the risks can be mitigated and passions can cool. Since Deng Xiaoping's ‘reform and opening’ strategy, ‘stability above everything else’ (wending yadao yiqie) has been a cornerstone of domestic policy. Prompt acknowledgment of domestic terrorism in the official media has the potential to undermine that stability. Green lighting popular discussion and further media coverage in the non-official press may, for example, intensify the ethnic tensions between Han and Uyghurs by triggering (and even seeming to sanction) violent reprisals. For instance, the extensive coverage of the July 2009 Urumqi riot is thought to have contributed to the deadly protest by Han Chinese that immediately followed (Wong Reference Wong2009).

When domestic conditions are unfavorable and the party is less popular, the public reaction to a terrorist event is more uncertain, and that uncertainty is less acceptable. In other words, if support for the government is already soft, a terrorist attack is more likely to bring with it a condemnation of the authorities rather than a rally in support. While public opinion on terrorist violence is generally pro-government and anti-Uyghur, this could shift, or the authorities could come under fire for not cracking down hard enough. Moreover, when domestic conditions are less than ideal, the authorities are much less willing to risk this social instability because they are less well positioned to weather difficulties. Any weakness in domestic conditions makes the Chinese authorities even more risk averse than usual – and therefore less likely to prioritize long-term interests in legitimacy over short-term interests in stability.

The few public opinion surveys that have been conducted on such sensitive matters suggest reasons for caution. For example, Hou and Quek (Reference Hou and Quek2019) report that 96 per cent of Chinese citizens think the government should increase efforts to prevent terrorist violence, raising the possibility that popular demands could outstrip what the government is able or willing to deliver. Further, while surveys suggest that citizens do not primarily blame the government for terrorist incidents, 69 per cent of Chinese citizens do think the current ethnic policies need to be modified (Chen and Ding Reference Chen and Ding2014). And opinion is polarized on the nature of that modification: 28 per cent strongly agree with reliance on forceful suppression and 40 per cent strongly disagree. In this context, official discussion of terrorist violence can invite critiques of standing government policy, push policy in directions that the authorities would prefer it not go, or expose rifts in public consensus.

There are also disincentives for open discussion of terrorism that stem from international considerations, particularly since highlighting Uyghur ethnic violence can invite foreign criticism of China's highly repressive ethnic policies (Jacobs Reference Jacobs2016). Although global concerns over militant Islamist movements can provide China with a useful rhetorical frame for Uyghur violence, Western suspicion that China hides human rights violations against its ethnic minorities behind the ‘war on terror’ has never faded.Footnote 21 Indeed, even when China's support at the UN was urgently needed shortly after the 9/11 attacks, US President George W. Bush cautioned then-Chinese President Jiang at a press conference following their first meeting in Shanghai in October 2001 that ‘the war on terrorism must never be an excuse to persecute minorities’ (Lam Reference Lam2001). Diplomatic circumstances were such, however, that Bush was willing to prioritize co-operation in the ‘war on terror’ over these concerns – going so far as to designate the leading Uyghur militant organization (ETIM) a terrorist organization at China's request.

Poor diplomatic relations diminish the incentive to officially acknowledge terrorist incidents, since such acknowledgement is more likely to engender international critique than promote co-operation. The CCP has long perceived critiques of its human rights record and minority policies as a threat to the regime and a barrier to international prestige, which Beijing uses to nurture its legitimacy at home. Chinese policy makers have explicitly argued that these critiques represent a ‘double standard’ given US actions at Guantanamo Bay, Abu Ghraib and broadly in the war on terror. An emerging tenet of China's diplomatic posture has been that such ‘double standards’ should not be tolerated for fear that international adversaries will use them strategically to undercut the Party (Duchâtel Reference Duchâtel2016).

Balancing Short- and Long-Term Priorities

Given these incentives and constraints, Chinese authorities face a basic problem of time-inconsistent preferences. Legitimacy at home and abroad are long-term priorities for the CCP, and the erosion of that legitimacy is perceived as a fundamental threat to power (Holbig and Gilley Reference Holbig and Gilley2010; Shambaugh Reference Shambaugh2008). Domestic instability and international pressure, however, are usually of more immediate concern. The Chinese government therefore confronts a dilemma: prompt official coverage of terrorist violence is an investment in long-term legitimacy, but fear of instability biases toward delay or silence.

We argue that unless both domestic and international conditions are favorable, Chinese authorities will prioritize short-term stability by delaying or forgoing official coverage of terrorist violence. This bias arises from the very foundations of the Party's claim to authority. Caution arises from a longstanding priority placed on social stability that dates back to the collapse of communist regimes in Eastern Europe and the Tiananmen democracy movement (Wang and Minzner Reference Wang and Minzner2015).

Just before the Tiananmen protests, Deng Xiaoping reportedly told George H. W. Bush: ‘[b]efore everything else, China's problems require stability’ (Bandurski Reference Bandurski2012). Shortly after the crackdown, Deng reemphasized that ‘stability is of overriding importance’ and a People's Daily front-page article titled ‘Stability Above Everything Else’, published on the first anniversary of the Tiananmen crackdown, cemented this stance as the bedrock of China's domestic policy (People's Daily 1990). The third generation of China's leadership, led by Jiang Zemin, continued this prioritization, emphasizing that ‘stability is the premise, reform is the driving force, and development is the goal’ (Wang Reference Wang2018). Hu Jintao, in turn, repackaged this idea with the slogan ‘building a harmonious socialist society’, the core principles of which were to ‘promote harmony through reform, consolidate harmony with development, and guarantee harmony through stability’ (State Council Gazette 2006, 33). Finally, and most relevant to the issue at hand, in the second Central Work Forum on Xinjiang held in 2014, Xi Jinping emphasized that ‘safeguarding social stability and achieving an enduring peace’ is the general goal of Xinjiang work (Leibold Reference Leibold2014, 4).

Why does the CCP delay coverage in the face of international opposition rather than expedite it? One might plausibly (but mistakenly) suppose, for example, that China would be more likely to report on terrorist incidents when diplomatic conditions are otherwise adverse in order to convince other countries that it is a victim of terrorism and needs their support. The answer lies in China's history, rapid rise and current nationalism. China's emergence from a ‘century of humiliation’ has left it with an arguably outdated, but still very real, intolerance of outside criticism, particularly at times of perceived weakness (Kaufman Reference Kaufman2009). Chinese authorities have been particularly sensitive to criticisms of human rights violations, which are generally viewed as a pretext for such interference and a means of delegitimizing the Party. International critiques on these matters also tend to play very poorly with Chinese domestic audiences and therefore risk further inflaming popular passions in the wake of a terrorist incident. Most significantly, because China has thus far been unable to garner consistent international endorsement of its domestic policies in Xinjiang, there is little reason for Chinese authorities to believe the international response will be favorable when the diplomatic situation is otherwise negative. In this sense, Western attitudes and the corresponding responses to violence in Xinjiang are contingent on the bigger picture: when there are broader disagreements with China, the Uyghur issue becomes a means by which to pressure and delegitimize Beijing, but when the mood tends more toward diplomatic co-operation in other domains then the narratives shift more readily toward terrorism. The result is that Chinese leaders tend to carefully evaluate their international diplomatic position when deciding whether to acknowledge domestic terrorism and are much more likely to report quickly when international conditions are otherwise favorable.

This bias toward caution is fundamental to the Chinese system's structure and incentives from the lowest to the highest levels. For individual bureaucrats and lower-level officials, poor performance on social stability targets has an immediate impact on promotion, can result in punishment, and typically cannot be overridden by good performance on other targets (Minzner Reference Minzner2009). At the same time, the top-level leadership is perennially fearful of popular unrest and accustomed to exercising strong controls over information. The combination of these forces leads the system to default toward caution and opacity (Stern and Hassid Reference Stern and Hassid2012).

We therefore anticipate that only when both domestic and international conditions are favorable will there be prompt coverage of militant violence in the official media. To be clear, it is not the case that the negative consequences of transparency disappear entirely when domestic and international conditions are favorable – rather, the Party's tolerance of this possibility and the uncertainty that accompanies it is higher, and thus it becomes more willing to reap the longer-term rewards of transparency.

Assessing the Timing of Official Coverage

We rely on the People's Daily (Renmin Ribao) to assess official media coverage of terrorist attacks.Footnote 22 This newspaper is widely understood to be the authoritative voice of the CCP; its editorials and commentaries are carefully curated to represent official views and enjoy ‘hegemony’ in shaping Chinese public opinion (Shambaugh Reference Shambaugh2007, 53).Footnote 23 Coverage in the People's Daily is an unambiguous green light that a topic is acceptable for popular discussion and further media coverage (within certain bounds). As a result, acknowledgment of a terrorist incident in the People's Daily can amplify broader coverage because it is a strong signal to both traditional media and social media users. While the terrorism coverage of more independent, audience-driven papers is not our dependent variable of interest, we searched these resources in the course of gathering our original data on all terrorist incidents. That survey indicated that these outlets generally wait for an official go-ahead before reporting.

We rely on event history models to assess the time to coverage in the People's Daily after a terrorist incident.Footnote 24 In keeping with broader patterns in Chinese media policy (King, Pan and Roberts Reference King, Pan and Roberts2013, 5),Footnote 25 we observe in our data that terrorism is rarely reported immediately following an attack but is more likely to be covered over time. This is partly because the penetration of social media and Internet-accessible outlets put increasing pressure on authorities to address high-salience events that have become common knowledge. Event history models can capture this delayed coverage dynamic. We measure duration as the number of days (up to one year) between an attack and the date it is first reported by the People's Daily. Footnote 26

There is no perfect single indicator for such an abstract and multifaceted a concept as domestic conditions in China. Our approach is to first operationalize this concept with multiple formulations of what we deem to be the literature's consensus on the best indicator – economic performance – before establishing robustness across a wide array of alternative measures including natural disasters and machine-coded events data from the Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS) project.

We prioritize economic performance as a measure of domestic conditions for two major reasons. First, Chinese officials themselves treat economic performance as foundational. Despite tremendous economic growth over the past few decades, Chinese citizens’ income as a percentage of gross national income remains low; increasing it remains a top official priority, and doing so without substantial turmoil requires growing the overall economic pie (Zhu Reference Zhu2011). Given the size of China's population and the extent of urban–rural inequality, high growth rates are seen as important to broader social stability and cohesion. It is therefore unsurprising that since Deng Xiaoping's opening and reform strategy, much of the CCP's legitimacy stems from its ability to deliver economic growth (Laliberté and Lanteigne Reference Laliberté and Lanteigne2007; Schubert Reference Schubert2008; Womack Reference Womack2005).Footnote 27 While there have been preliminary indications of a shift from purely growth-based legitimation to one that takes social equality and welfare more seriously, even such refinements are based on the prerequisite of overall growth (Gilley and Holbig Reference Gilley and Holbig2009; Holbig and Gilley Reference Holbig and Gilley2010). Second, economic performance is broadly felt across society and is therefore hard to hide completely. Citizens have first-hand experience of (and are highly responsive to) the job market, cost of living and wages. The government is therefore highly sensitive to any negative signals from the economy.

To address concerns regarding the accuracy of official Chinese statistics, we rely on three indicators: annual GDP growth rate (Growth), the annual Consumer Confidence Index (CCI)Footnote 28 and the Li Keqiang Index (Li-Index).Footnote 29 The current Chinese premier, Li Keqiang (then a provincial governor), reportedly told an American diplomat in 2007 that he focused on three indicators to evaluate the true economy: electricity consumption, railroad freight and bank loans (Rabinovitch Reference Rabinovitch2010). Following Clark, Pinkovskiy and Sala-I-Martin (Reference Clark, Pinkovskiy and Sala-I-Martin2017), we construct the Li-Index as the annual average of the growth rate of these indicators.

Despite wide skepticism regarding the accuracy of official Chinese GDP statistics, the debate primarily centers on whether the official figure systematically overstates the true figure (Holz Reference Holz2014). The trend in GDP is still seen as informative. For example, Owyang and Shell (Reference Owyang and Shell2017, 12) note that ‘while the level of Chinese GDP may remain overstated…the recent growth rate numbers for Chinese official data are more reliable’. However, the CCI and Li Keqiang measures sidestep this concern because they are broadly viewed among experts as not being subject to the same extent of official manipulation in the first place. While they proxy for economic conditions, they lack the political salience of the direct measure (and corresponding incentives to manipulate them). With regard to the Li index, this lack of salience and manipulation is precisely the reason that Li Keqiang articulated his reliance on that set of indicators for insight into the true economy (Rabinovitch Reference Rabinovitch2010).

Perfect measures of how Chinese government officials evaluate the international environment are similarly elusive, but as Ikenberry (Reference Ikenberry2008, 30) argues, ‘the most farsighted Chinese leaders understand that globalization has changed the game and that China accordingly needs strong, prosperous partners around the world’. To capture officials’ assessments, we investigate the extent to which China is diplomatically integrated or isolated, using United Nations (UN) General Assembly voting data (Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017). The variable, Majority Frequency, measures the proportion of each year's important UN votes in which China is a member of the majority.Footnote 30 This results in a continuous variable, ranging from 26.7–77.8 per cent, with larger values indicating a more favorable international diplomatic environment. To further address the concern that Beijing may value relations with some countries more than others, we also assess two variants of the Majority Frequency measure: China's majority votes among G20 countries and China's majority votes within the Security Council.

Because our theory implies an interaction between China's domestic and international environments, we include the interaction term between them in all models.Footnote 31 Because both indicators, regardless of their specific operationalization, are continuous and lack a substantively meaningful zero, we center these variables by subtracting the mean value from the observed value.

Our models also include several confounders that are related to both the dependent variable and the independent variables of interest. Among incident-level attributes, we include dummy variables for attacks that Target Civilians, involved a Bombing or happened in densely populated Urban areas; we also account for Casualties per attack. These attributes would contribute directly to public awareness and/or newsworthiness, and therefore affect the duration of wait-to-report periods. They may also indirectly affect Chinese authorities' sensitivity to the external environment, because low-intensity attacks initiated by poorly equipped perpetrators against government targets are usually difficult for Beijing to sell as terrorist attacks; they instead tend to be interpreted as spontaneous responses to state repression.

Our models also address politically delicate periods for the CCP (Sensitive Period) when the authorities are likely to be systematically biased toward maintaining stability (wei wen). We identify these periods as: (1) a month in which annual sessions of the National People's Congress (NPC) and National Committee of the People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) are held (liang hui); (2) a month in which the National Congress of the CCP is held; (3) leadership transition years or (4) the year of the 2008 Olympics.Footnote 32 Such moments may be related to both perceptions of domestic conditions and greater cautiousness with regard to official coverage.

Finally, we include Internet Penetration (the ratio of the number of Internet users to the total population in each year) to capture the possibility that the costs of delayed transparency grow with technological change, particularly social media, while also changing domestic conditions.Footnote 33

We rely primarily on Cox proportional hazards models for which a positive (negative) coefficient indicates that a one-unit increase in that variable is associated with an increase (decrease) in the hazard rate, defined as ‘the rate at which units fail (or durations end) by t (a predetermined period of time) given that the unit has survived until t’ (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones Reference Box-Steffensmeier and Jones2004, 13).Footnote 34 The hazard is therefore interpreted as the rate at which domestic attacks are reported (or durations of wait-to-report periods) at time t given that the attack has not been reported by t.

Table 1 presents the results of seven such models. Model 1 is a streamlined test of the interaction between the domestic and international environments, measured in terms of GDP growth and UN voting majority frequency. Model 2 adds country-level control variables. Model 3 is the first full model, which contains both country-level and incident-level controls. Models 4 and 5 replicate Model 3 but with the Li Index and Consumer Confidence Index as alternate indicators of economic performance. In Models 6 and 7, we use two variants of UN voting majority frequency that focus exclusively on G20 countries and Security Council members, respectively.

Table 1. Models of time to reporting in People's Daily after terrorist incidents

Note: table entries are coefficients obtained from Cox proportional hazards models. Robust standard errors clustered on the incident are in parentheses. *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01

All the models are in line with the expectation that Chinese authorities promptly cover violence in the official media only when both domestic and international conditions are favorable.Footnote 35 This relationship is clearest when shown graphically – which we do for Models 3–5 in Figures 3–5.Footnote 36 A similar graphic can be generated from the results of any of the models in Table 1.

Figure 3. Probability of non-reporting for combinations of growth and majority (Model 3)

Figure 4. Relative risk of coverage (Model 4)

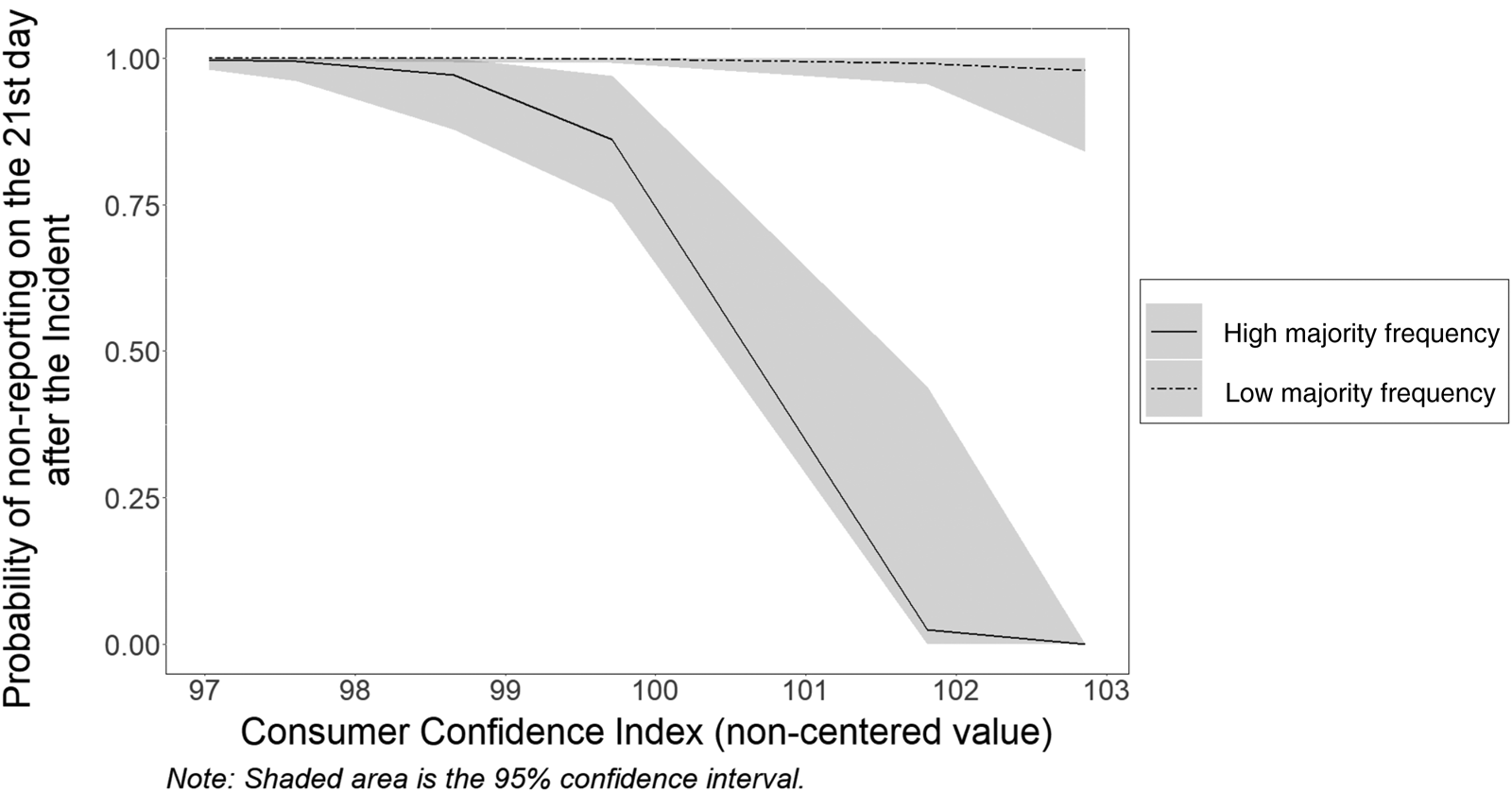

Figure 5. Probability of non-reporting by the twenty-first dafter terrorist attack (Model 5)

First, in Figure 3, we generate estimated survival curves for non-reporting under four hypothetical cases based on Model 3: (1) high growth and high frequency, (2) high growth and low frequency, (3) low growth and high frequency, and (4) low growth and low frequency.Footnote 37 The estimated probability of non-reporting in the official media drops quickly when both the domestic and international political environments are favorable –to about 0.80 one day after a terrorist incident and continues to decline over time, to about 0.59 after 4 days. In contrast, the survival curves for non-reporting under all other combinations of conditions remain statistically indistinguishable from both one another and from 1.

Figure 4 demonstrates how the relative risk of coverage varies with different combinations of Li-Index and Majority Frequency based on Model 4.Footnote 38 The left-hand panel shows that when Li-Index is high (one standard error above the mean), the probability that an incident will be reported by the People's Daily will become significantly higher than the sample mean probability only when Majority Frequency is also high. Specifically, when Li-Index is high and Majority Frequency is lower than its mean (49.57 per cent), the probability of being reported is not significantly different from the sample mean probability. However, this risk becomes 3.92 times and then 11.59 times higher than the sample mean as the Majority Frequency increases to 55 per cent and 60 per cent, respectively. In contrast, the right-hand panel of Figure 4 demonstrates that when internal conditions are not favorable, the probability of coverage is indistinguishable from the sample mean probability regardless of the proportion of UN votes in which China is a majority.

In Figure 5, we plot the variation in the probability of non-reporting by the twenty-first day (three weeks) after a terrorist attack across different values of the Consumer Confidence Index when Majority Frequency is high and low (one standard error above and below the mean). Again, the graph indicates that prompt reporting is only likely when both domestic and international conditions are favorable to the government. When Majority Frequency is high, the probability of non-reporting by the twenty-first day after an attack is nearly 1 when the CCI is below its mean value (about 99.7). This decreases to 0.86 (meaning that coverage is more likely) at the mean value for CCI. The probability of non-reporting plunges to 0.02 at one standard deviation above the mean (about 101.8). However, if the Chinese government is internationally isolated (that is, the majority frequency is low), there is essentially no change in the probability of non-reporting regardless of the state of the economy.

Among the control variables, Urban, Target Civilian and Bombing are not significant predictors. The coefficient for Sensitive Period is positive and significant in Models 2, 4, 6 and 7, which contradicts our expectation. This result is potentially caused by the increased global attention paid to China during these periods, especially during the 2008 Olympics, which could make censoring more difficult and costlier. As anticipated, the coefficients for Internet Penetration and Casualties are positive and significant.

Alternative Specifications

To establish the robustness of these findings we reassess our models with alternate operationalizations, control variables and periods of analysis (Table 2). In Model 8, we account for the possibility that both Majority Frequency and time to coverage may be confounded with underlying elements of Chinese foreign policy. Put differently, a change in China's foreign policy may simultaneously lead to voting in the majority at the UN and a willingness to acknowledge attacks in the official media. Given that the time horizon of our data covers three different Chinese leaders – Jiang, Hu and Xi – there might be systematic differences in their foreign policies that must be accounted for. To address this possibility, we include an estimate of China's ideal point from the General Assembly voting data (Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017), which is widely used as a measure of the country's foreign policy position.Footnote 39 We also include Global Terrorist Incidents, which is measured as the logged value of the total number of successful terrorist attacks in a given year around the world, to account for the possibility that the global trend of terrorism may induce Uyghur attacks and make the international climate more favorable for transparency.

Table 2. Alternative model specifications

Note: table entries are coefficients obtained from Cox proportional hazards models. Robust standard errors clustered on the incident are in parentheses. *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01

To further address concerns about specific operationalizations of key variables, we use alternative measures of domestic and international conditions – natural disasters and diplomatic relations with the United States. The Chinese government has long been sensitive to natural disasters because they disrupt regional economic development, threaten social stability and present openings for critiques of government performance. The 2008 Sichuan earthquake exemplifies this threat and sensitivity. Days after the earthquake, local residents, especially parents who lost children, turned from grief to anger and started protesting the poor workmanship and government corruption that led to the collapse of several schools (Blanchard Reference Blanchard2008; Branigan Reference Branigan2008). We posit that a year more plagued by natural disasters indicates a more challenging domestic environment, during which the Chinese government would be more reluctant to report other negative events including domestic terrorist attacks. To measure the severity of natural disasters, we calculate the total number of days in a given year during which China experienced natural disasters that caused ten or more deaths.Footnote 40 A further advantage of these data is that natural disasters are outside the government's control and are therefore plausibly exogenous to the mechanisms we are exploring.

As an alternative measure of the international environment, we focus on the Sino–US relationship. Given the United States’ primacy in the international system, the salience of the United States in Chinese foreign policy calculations, Beijing's particular sensitivity to American critiques of China's human rights record, and the centrality of the United States in global counterterrorism policy, it is reasonable to anticipate that bilateral considerations (rather than the Chinese position vis-à-vis a global average) might factor more prominently in official calculations. The variable, US–China Distance, is the absolute distance between the ideal points of China and the United States based on their UN voting (Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten Reference Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten2017). In Models 9, 10 and 11, we substitute the original measures of domestic and international conditions with these two alternative measures one by one and together, respectively (while controlling for GDP growth).Footnote 41

In Model 12, we utilize machine-coded measures of domestic and international conditions from the ICEWS event data (Boschee et al. Reference Boschee2018).Footnote 42 All of our previous operationalizations of domestic and international conditions vary only by year, which may be insufficiently granular to fully capture the decision-making environments facing the Chinese government when attacks happen. The ICEWS data allow us to address this concern with more granular ‘intensity scores’ of both domestic and international conditions.Footnote 43 The intensity scores range from −10 to 10, with lower values indicating hostile interactions and higher values indicating co-operation. For Internal Condition, we calculate the mean value of the intensity scores for all China's domestic events that happened within 90 days before each violent attack. External Condition is calculated in the same way for all international events in which China is the target.Footnote 44 We normalize both variables to a 1–10 scale.

Finally, as noted above, the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks increased the opening for China to reframe the Uyghur militancy in the context of the war on terror. Internet penetration and social media use also exploded in China at about that time. To explore this dynamic we limit the analysis to the post-2000 period in Model 13 using the ICEWS data. Unfortunately, the temporal coverage of the ICEWS data prevents us from using it for an equivalent pre-9/11 analysis, which would further clarify this point if it were possible. Table 2 indicates that the coefficients for the interaction term remain significant and in the anticipated direction in all models.

In Figure 6 we repeat the four-case survival curve comparison presented in Figure 3 for the models in Table 2. All these plots reveal almost identical patterns; the probability of non-reporting drops sharply only when both domestic and international political conditions are favorable. The plot based on the post-2000 subsample (Model 13) produces predicted probabilities that are relatively lower than those using full samples, which suggests that 9/11 was indeed a turning point after which China became more willing overall to internationalize its domestic terrorist incidents. However, even in this period, official acknowledgments were still more likely when both domestic and international conditions were favorable.

Figure 6. Alternative specifications

Conclusion

Chinese policy makers' decisions regarding official coverage of terrorist incidents are highly politicized. The available evidence indicates that this calculus is governed by caution: timely acknowledgment of terrorism occurs only when both domestic and international conditions are highly favorable. While transparency can boost the government's legitimacy, publicizing domestic terrorism immediately risks social and political stability by intensifying ethnic tensions, encouraging copycat attacks, engaging public opinion and prompting international criticism. These time-inconsistent preferences lead Chinese decision makers to attend to the short-term risk at the expense of longer-term goals unless they believe those risks are minimal.

These findings also contribute to the emerging literature on the strategic logic of China's censorship policies. While not in opposition to arguments that China's information control policies center on undermining collective action, we argue that there is evidence in favor of an underappreciated, parallel mechanism: authorities censor uncertainty (King, Pan and Roberts Reference King, Pan and Roberts2013).

With over 420 million Internet users, China has more people surfing the web than any other country, and new web-based technologies are increasingly directing media attention. Over the past decade, numerous incidents that were first reported online generated such outrage that traditional news media were compelled to report on them, often leading to changes in the government's positions.Footnote 45 The spread of these new technologies may undermine the current model of media control in China, which relies on a combination of self-censorship and official oversight (Weber and Jia Reference Weber and Jia2007). It is plausible that the growth of social media will accelerate the timeline for reporting by increasing the costs of opacity. That said, if social media growth turns out to favor government surveillance and information control, then the pressures for transparency are likely to decline, all else equal. These are trends worth keeping a close eye on as China seeks to export its model of information control around the region and even the globe.

In addition to China's media policy towards domestic terrorism, our work also draws attention to an underappreciated issue – the violence itself. Despite the increasingly intense social control and continuing ‘strike hard’ campaigns in Xinjiang, the forces that have given rise to Uyghur terrorism remain unresolved. Complicating the picture, China's domestic security crackdown contributes to grievances and pushes militants into weakly governed border states where they can congregate, train and plan attacks. Uyghur fighters have shown up in Iraq and Syria, and propaganda photos released in 2016 show Uyghur children participating in weapons training, which suggests a troubling future for terrorism in China (Weiss Reference Weiss2016). Given the strategic importance of Xinjiang and the broader Central Asia region to China's ‘Belt and Road’ strategy, it is reasonable to anticipate that these issues will become more salient in the coming decades.

Extending beyond China, future work would do well to consider the extent to which the findings that we present here generalize to other institutionalized autocracies like Russia. Our findings indicate that the ways in which China manages sensitive information are more complex than the choice to censor or not censor. The institutional mechanisms that we identify as driving this impact are, however, present in many of the most important autocracies with systems in which parties and legislatures are broadly used to manage public opinion and leaders do, in fact, have popular mandates. At the same time, changes in the media and information landscape mean that the populations in these autocracies have independent means of obtaining information, which makes notions of absolute censorship obsolete. Thus while autocrats maintain important levers of information control, they are less about censorship than they are about the decision to strategically highlight some pieces of information and obscure others.

Finally, for scholars of terrorism and political violence, the work we present here has important implications for our understanding of the event data we work with. To the extent that data collection efforts rely on local media, attack data from autocracies may be biased toward those that occur in favorable circumstances for the regime. This, in turn, could drive prior findings that autocracies are better able to limit and handle terrorist attacks. A further implication of this point is that militants may strategically time their attacks to advance their agendas. In the case of China, the official acknowledgment pattern we uncover suggests that militants who operate in similar environments (for example, the broader political pursuit has international support, but the violence is subject to condemnation) may face a tradeoff. Attacking when the government enjoys good external relations could garner publicity as the government is more likely to report it, but this could also serve the government's strategy to delegitimize the militants' political agenda. In contrast, attacking when the target government is internationally isolated would likely be followed by government attempts to suppress news of the violence, but would potentially find greater international sympathies were word to get out. Thus the degree of under-reporting or systemic missing data is likely to be affected by the dynamics of the interactions between militants and governments.

Supplementary material

Online appendices are available at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000514.

Acknowledgements

We thank seminar participants at the University of Virginia, University of Pennsylvania, University of Southern California, and RAND corporation for excellent comments and feedback. We also thank Yue Hou, Jonathan Kropko, Brantly Womack, participants of the panel on Democracy Comes to China: Transparency and Participation in Chinese Politics at the 2018 APSA annual meeting, the two anonymous reviewers, and the editor for helpful feedback at various stages of the project. All errors remain our own.

Data availability statement

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XCN5HY