Background

A cancer diagnosis is likely to have a devastating effect when it occurs, but is possibly especially problematic during adolescence. A diagnosis of cancer causes uncertainty, fear, disruption, restrictions in daily life, increased psychological and physical work, lengthy and rigorous treatment regimes. As such, cancer in adolescence can be viewed as a major life transition. It can be described as a powerful life event that causes adolescents and their families to face the above challenges.Reference Richie1 For those unfamiliar with cancer in this age, it is normal to experience a sense of intense injustice when it occurs.Reference Kelly and Gibson2 As a society, we are not equipped with the skills to manage serious illness and death, especially when they occur in children and young adults. There is something profoundly wrong about the death of a child before its parents.Reference Grinyer3 The many challenges faced by adolescents have led to a concern for their psychosocial well-being.Reference Woodgate4 There is sound evidence to support the notion that the provision of effective psychosocial care improves the outcomes of patients with cancer.Reference Botti, Endacott and Watts5

Teenagers are emotional because they are at a stage where they are renegotiating relationships with their parents, and making new peer groups, and sexual relationships, building self-esteem and preparing for adulthood. This can weaken family bonds as young people seek the company of their peers away from parental supervision, again a manifestation of the search for independence.Reference Brannen, Dodd and Oakley6 Cancer accentuates and adds new dimensions to young people’s anxieties.Reference Clarke, Michell and Sloper7 Adolescents with cancer must be recognized as a subgroup of oncology patients with specific needs requiring dedicated interest and management. The physical, emotional and social challenges posed by cancer are often unique and especially difficult for patients, families and healthcare professionals.Reference Albritton and Bleyer8

The aim of the review is to provide a detailed overview of the literature to make an informed judgment on how teenage cancer services can be effectively delivered. This shall be achieved by first critically discussing the psychosocial aspects of living with the cancer for the patient and their families and second to evaluate the role of the multi-disciplinary team with emphasis on the nurse as a key provider of the care.

The methodology for this review included a literature search of Cinahl, Medline, British Nursing Index and Cancer Literature, using the keywords teenagers, oncology nursing and psychological effects. A total of 24 relevant articles using the above criteria were identified, of which 21 research articles were selected. Some of the key issues identified include the loss of independence, uncertainty and distress, coping, body image, sexuality and fertility. The key issues are presented in the form of a theme matrix (Table 1).

Table 1. Theme matrix

No, number of paper; OR, country of origin; TY, type; U, usefulness; X, major theme; 1, Facts, statistics, research findings; 2, theory or interpretation; 3, opinions, beliefs, points of view; 4, anecdotes, clinical impressions.= Medical; +nursing; ***high; **moderate; *low.

The impact of cancer on the adolescent

In the United Kingdom, there have been a number of government initiatives being undertaken to improve the care of young people with cancer as part of the national cancer strategy. One of the recent initiatives ‘Improving Outcomes in Children and Young People With Cancer’9 in its recommendations suggests that all children and young people with cancer should have access to psychological support with clear routes of referral in principle treatment centres. A government report ‘Welfare of Children and Young People in Hospital’ stressed the impact that hospital admission can have on the normal emotional and physical challenges experienced by adolescents, and highlighted the need to provide acceptable facilities with appropriately trained staff.10

The loss of independence

The life stage of young adulthood from late teens to early 20s is one of turbulence and transition, and is characterized by attempts to gain independence from the family of origin. Such an attempt is an integral part of the process of maturing and do not necessarily denote problems within the family, although some of the attempts to breakaway and claim an individual identity may result in conflict.Reference Neville11 In this life stage, many young people may have sought and found independence before becoming ill. This can pose particular problems for the family when the young adult has to relinquish a newly found independence and once again be thrown back on relationships associated with childhood and dependency.Reference Neville11 For this group of patients, the struggle for independence is central to this stage in their life. However, practice identifies that independence is unlikely to be sustainable when these adolescents are under the stress imposed by a life-threatening illness.

Uncertainty and distress

The diagnosis of cancer continues to be associated with increased levels of psychological distress, uncertainty, a factor associated with psychological distress is a major concern to adolescents with cancer. A study examined the relationship between uncertainty and psychological distress and found that uncertainty regarding what will happen, what events may mean and what the consequences of events may be are important to individuals faced with cancer.Reference Neville11

Keeping patients and families well informed about treatment protocols and side effects, as well as prognosis and consequences of treatment may reduce the uncertainty experienced in cancer by assisting adolescents to interpret environmental cues. The period of waiting is often perceived by families as the most difficult aspect of the entire illness. Priority should be given to keep the family as best informed as realistically feasible.

Information is important because it gives patients and their families a sense of control, reduces their anxiety and uncertainty about their illness and perhaps enables them to plan to the future. It is difficult to judge the amount and type of information that an individual person wants or needs.Reference Walker, Payne and Smith12 Clinical practice has shown that it is best to elicit what the patient already understands, find out what they wish to know, and check afterwards what they have understood. A study looking at the informational needs of teenagers found that the teenagers’ priorities were information about their diagnosis, prognosis and treatment.Reference Hooker13

It is paramount that such a life-threatening illness is likely to bring about some degree of uncertainty and distress for the adolescents and their families involved. However, as it has been well documented, information can reduce the threat and uncertainty and it may help young adults to understand their illness and participate in their care.

Coping

The ways in which adolescents cope with the stress and challenges of disease are an important investigational area. How a patient copes with his/her illness may well be the difference between optimum recovery and psychological distress. Involving patients in their care and discussing treatments and options could inevitably increase motivation and lessen anxiety. It can be argued that the nurse is primarily the individual who spends the most time with the patient and therefore would be in a key position to initiate the care.

In order to understand the effects of cancer diagnosis and treatment in adolescents researchers looked into the adolescent’s experiences’ of cancer. They found the negative experiences that the adolescents described as not entirely negative and it may result in improved relationships with others (Table 2).Reference Novakovic, Fears and Wexter14 Interestingly they found that problems related to the emotional aspects of cancer may not be readily recognized in adolescents at the time of therapy. They may hide their feelings under pressure to act as adults, or they may find themselves isolated and unable to communicate with their parents.Reference Novakovic, Fears and Wexter14 This is a common trait seen recognized in the practice; having difficulties in communicating with loved ones in order to save them from further pain and anguish.

Table 2. Negative experiences of having cancer

Adolescents who have cancer are at risk of negative health outcomes. Promoting positive coping during the developmental period helps adolescents to assume greater responsibilities for their actions.Reference Hinds15 There has been an association between psychosocial development and coping, constituting of self-esteem and hopefulness.Reference Richie1 Health professionals should promote positive coping, as hopefulness in adolescents is significantly related to indicators of the adolescents’ emotional well-being.Reference Hinds15

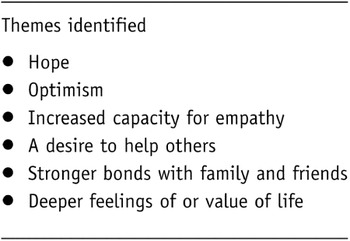

Further research examined whether cancer in adolescents had any positive consequences. The findings identified themes that relate to positive consequences (Table 3).Reference Karian, Jankowski and Beal16 Other researchers further support these findings and add that cancer during adolescence does not necessarily lead to negative consequences. Positive relations with staff and being well-cared for are positive aspects. Their findings indicate that good care for adolescents consists of meeting friendly supportive staff who provide then with appropriate information.Reference Hedstrom, Skolin and von Essen17 It can be argued that all adolescents are individual with specific needs and that a 16-year-old living at home is unlikely to have the same coping abilities as a 24-year-old single mother of two. Care and support needs to be focused on a patient’s individual needs ensuring that their coping abilities have been assessed.

Table 3. Positive aspects of having cancer

Body image

The loss of normality, disruption to life’s plans along with the physical symptoms and fears around cancer makes it challenging but when these factors are combined with the effects of appearance, morale can be even lowered even further. The illness and treatments associated with cancer result in adverse changes in body image and can manifest in hair loss, weight loss, weight gain and scars from surgery. These changes to body image leave young adults ill at ease in social situations.Reference Arbuckle, Eden, Cotton, Eden, Barr and Bleyer18 Research studies have continuously noted hair loss as a transient cosmetic detect, but also a trait that deeply influences relationships with peers.Reference Novakovic, Fears and Wexter14 It is evident that patients’ have either made light of their image or appearance, i.e. making jokes and taking the mickey out of themselves or they have kept quiet and dismissed their true feelings. A pertinent question is what we as health professionals do to support these patients? Experience has shown that unless problems are evident then we too dismiss the subject. Is it the case of why bring up the topic if it is not a problem or will we be opening up a can of worms?

A study looking at adolescents’ experiences of cancer found adolescents describing themselves as the alien when they experienced a body that was distorted and foreign to them. Hair loss, round puffy faces, weight loss or weight gain, a slow moving body, and unusual emotional feelings contributed to them having feelings of living in a strange body. However the study found that for the adolescent, it is vital that friends and family accepted them despite the changes in their bodies that transpired during the cancer trajectory. 4 Previous studies also found children want families to treat them like the ‘same old person’, even though they have endured changes in their illness due to cancer.Reference Rechner19–Reference Glasson21

For this age group, the change of appearance brought on by illness and its treatment has a profound effect on their morale and self-confidence. Health professionals need to ensure that they have adequate training and the skills in order to deal with the adolescent’s issues and concerns.

Sexuality and fertility

Much normal adolescent activity and discussion is focused on sexual awareness, finding a partner and sexual activity. Through peer group isolation, young people with life-limiting illness often miss out on this normal adolescent information and discussion.Reference Craig, Goldman, Hain and Liben22 It is a matter of everyday knowledge that parents and their children commonly find it difficult to talk about sexual issues, so comforting them can create confusion and embarrassment.Reference Grinyer3 Many parents, intentionally or not, are unaware of their children’s experiences of sexual activity. Yet already under immense emotional stress and anxiety, both parent and child have to confront not only their illness, but also a potentially detailed account of intensely private behaviour.

Clinical practice shows that some can openly discuss such issues and not feel embarrassed whereas others ignore the issue in hope that we as health professionals will discuss such matters. Discussing sexual issues is a vital area often neglected by nurses because they are embarrassed and lack the appropriate knowledge.Reference Kelly and Gibson2 However, it is evident that working in small teenage specialist cancer units has shown that we are better at discussing such matters especially as we are giving chemotherapy to young adults; so first the matter of sperm donor has to be discussed and second while having chemotherapy the matter of contraception needs to be enforced. It is perhaps more difficult to broach the subject to patients that are much older than the nurse.

A cancer treatment such as chemotherapy is likely to result in infertility. The adolescents’ parents’ concern may be to start treatment as soon as possible without paying attention to the effect on fertility. However, the patient may have a different priority. The prospect of a parent and young adult freely discussing sperm donation may be challenging to all parties. The difficulties with sexual relationships can be exacerbated by the effects of the illness and its treatment which can jeopardize fertility in both young men and women. Sex and sexuality are of fundamental importance to young adults and therefore should be the focus of health professionals’ concern during care.Reference Grinyer24

For this age group, sexuality is an important area that requires communication that includes information that is accurate and tailored to individual needs. This can be a challenging role for the professionals as the adolescent with cancer may or may not be ready to process such information and families struggle with the complexities of active treatment, quality of life issues and future aspirations. Therefore, it is essential as health professionals that a coordinated approach is developed.

The impact of cancer on the family

Parents experience a wide range of emotions and experiences when their child has cancer. Parents may ask questions such as ‘why?’ and uncertainty is a commonly described emotion. In a study looking at the experiences of adolescents with cancer, adolescents were unable to communicate with their parents.Reference Hooker13 Better psychosocial adjustment of long-term survivors of childhood cancer has been related to open and supportive communication about the diagnosis and treatment early in the course of the disease.Reference Hymovich and Roehnert25 Patients who show the lowest distress also report the best patient family communication.Reference Gotcher26

Clinical experience shows that open and honest communication is associated with families being able to provide effective emotional support. However, the threat of cancer may be so unspeakably dangerous to the security o the family unit that open communication becomes tense, consequently relationships between family members become strained.Reference Brennan23

Research found that adolescents with cancer were more in conflict with their mothers than the healthy young.Reference Manne and Miller27 They suggest that as the adolescents spent more time with their mothers, a difference of opinion appeared between them about the adolescents’ developmental needs for independence over their mothers’ overprotection during treatment.Reference Manne and Miller27 It is evident that this does often occur, mainly as the literature suggests the amount of time parents’ spend with the adolescent. They do not get any time alone and in ‘normal’ circumstances an adolescent would not spend day and night with their parents.

The involvement of parents in medical consultations may become more problematic when a son or daughter reaches young adulthood. Young people in this age group are legally entitled to be the recipient of medical information and may decide not to share this with their parents.Reference Kelly and Gibson2 This can undermine parents and make them feel unwanted and hurt. At the same time, the patient has the right to his/her own dependence. Parental concern can be a source of irritation to adolescents, even when directed towards what may become a matter of life and death.Reference Kelly and Gibson2 Clinical practice has shown that sometimes adolescents have to surrender to the parents being present and the sharing of medical information.

The literature has identified that other family responsibilities and roles may suffer especially in terms of the attention and time parents can give to other siblings. A significant factor to be taken into consideration is the effect that illness may have on siblings. They can feel isolated and invisible as the parents’ time is taken over by medical appointments and hospital stays. The sibling might feel guilty that they have caused the illness or fear that they too may become ill.Reference Grinyer3 It is not surprising that stressful relationships are a recurring theme in the literature. Contact with extended family and the role of friends is an important area of change in psychosocial stress.Reference Clarke, Michell and Sloper7 The government initiative ‘Improving Outcomes in Children and Young People’9 recommends all children and young people with cancer and their families, should be offered the advice and support of a social worker to ensure that the needs of the wider family are addressed. In practice, we are making some head way as this has started to be introduced in most Teenage Cancer Units.

Clinical practice has shown that families can be a vital source of emotional and practical support for adolescents with cancer. However, family members are often highly distressed and in need of support themselves. They are often inhibited from expressing their true feelings because they are protecting one another from further distress.Reference Brennan23 In order to provide the adolescents with holistic care, it is not just their needs that health professionals need to address. It is evident that the concerns of the family should also be taken into consideration in the delivery of care and support given by members of the multi-disciplinary team.

Friends and peers

Friends have an important role to play in the lives of young people. Adolescents with cancer need to maintain strong peer relationships and the knowledge that friends care for them is especially vital to them. Prolonged periods of hospitalization may impact on social contact with peers. Previous research suggests best friends will often become closer and friends who are less close will disappear.Reference Enskar, Carlson and Golsater28,Reference Ishibashi29 Adolescents also express concern about the challenges of being treated differently by their friends. They do not want to be singled out as being different or to be labelled as special.Reference Woodgate4

It is evident that as long as the patient is fairly fit and well, peer support is important. In fact, it is vital for patient’s morale. However, when the patient has a relapse and becomes quite ill due to the side effects of treatment than the family network becomes high priority and other provisions of care need to be introduced. For example other healthcare disciplines who have a diversity of psychological skills. This relates to the four-tier model (Table 4), adopting the model can be beneficial for those affected by cancer with regards to the reduced levels of distress, improvements in the quality of life and making the experience of having cancer more acceptable.30

Table 4. Four-tier model of psychological support

The importance of friends, both non-cancer related and cancer related must be recognized.Reference Clarke, Michell and Sloper7 Research has indicated that both sets of friends play an important psychosocial role. Patients, who meet other adolescents while having treatment, are often felt to be people who really understand how they feel. Whereas non-cancer friends are valued as they help the patient to retain some normality.Reference Richie1,Reference Woodgate31

It has been suggested that making ‘cancer friends’ is dependent on a number of variables. First the settings itself, a lot teenager cancer units are single roomed and have all the amenities that the patients need without them leaving their room. For example TV, DVD player, computer, telephone and music system. Second, a lot patients have their families staying with them, therefore they are around if the patient needs anything from the kitchen and lastly this is dependent on the patient’s personality. Practice shows that unless the patient is in for a long period of time with other patients they do not easily socialize. However, activities are organized monthly to encourage them to socialize with one another but again it is dependent on how they feel at the time. There is a need for adolescents to meet peers to engage in a variety of activities.Reference Clarke, Michell and Sloper7 Nurses need to help adolescents to find a peer group of other adolescents with cancer. This can help adolescents to identify themselves with others going through the same ordeal.Reference Enskar, Carlson and Golsater28

For this age group, a cancer diagnosis will separate young adults from their peers and disrupt friendships. Healthcare professionals have an important part to play in ensuring that these patients’ individual needs are met and throughout their treatment these patients should be given the opportunity to interact with their peers.

Teenage cancer units

Arguments are presented for the formation of specialist teenage cancer units on the premise that the centralization of care would improve treatment and survival. The physical, social and emotional needs of adolescents are best served by the expertise of a multi-disciplinary team. Multi-disciplinary team working is now a key feature of cancer services, in part to ensure that there is appropriate care throughout the patient’s journey.9 Effective team working is central not just to the patients’ and families’ experience of cancer, but also to the effect of cancer care on the professionals — both as individuals and as a group.Reference Kelly and Gibson2

Recent research supports previous findings that adolescents with cancer experience difficulties in communicating about how they feel to nurses and other health care providers.Reference Woodgate31 However in practice, health professionals are seen to block and distance themselves from the psychological and emotional content of communication between patients and relatives.Reference Booth, Maguire and Butterworth32,Reference Kelsey33 This occurs to protect the health professionals from taking on the uncomfortable and distressing feelings that occur in the patient’s situation.Reference Towers34

Nurses, who have considerable contact with patients, are well placed to assess and provide supportive and psychological care. However, research suggests Nurses need to demonstrate that they have the right skills and apply them correctly.Reference Towers34,Reference Booth, Maguire and Butterworth32 It is evident that time is a precious commodity and it is the supportive communication that is the first aspect of nursing care to be neglected on busy shifts. Talking and listening can however, be easily combined with other nursing activities, such as washing and dressing.Reference Towers34 On the contrary, this demonstrates why there is a need for other specialists from the multi-disciplinary team to intervene.

Research carried out on hopefulness suggests that nurses and other healthcare professionals are able to positively influence hopefulness in adolescents with cancer and in doing so, may improve the outcomes of these patients.Reference Hinds35 Adolescents’ feelings of decreased control and independence can be redirected toward a sense of hopefulness. Thinking about the future is common for adolescents and should be encouraged by healthcare workers.Reference Richie1 Nurses should carry out individualized and comprehensive assessments of adolescent experiences and needs. This may have a positive effect on the adolescents’ well being.Reference Hedstrom, Skolin and von Essen17 It is important for the staff working with adolescents to know what distresses them and their capacity to deal with the stressors, and furthermore to know which nursing care interventions are needed.Reference Enskar, Carlson and Golsater28 It is evident that nurses play a key role in helping patients cope with cancer and treatment by respecting individual differences and preferences. The literature shows that adolescents want professional care givers to show more encouragement and positive attitude.Reference Hokkanen, Eriksson and Ahonen36

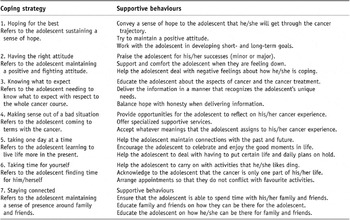

Table 5 looks at the supportive behaviour that promotes coping strategies in adolescents with cancer. Health professionals can use these as a guide to promote coping in adolescents.Reference Kelly and Gibson2 It is evident that patients do respond better when a positive attitude is conveyed both by them and health professionals. This activity should be seen as opportunities to engage in supportive care. The needs of this age group are of central importance to the provision of care. Health professionals need to address the adolescent’s needs focusing on a holistic approach. Teams caring for these patients need to be experienced in responsiveness to the specific, social, psychological and educational needs of children and young adults with cancer. The nurse as key worker with appropriate training is ideally positioned to provide the support; however the skills of the wider team should be developed.

Table 5. Supportive behaviours that promote coping strategies

Conclusion

Cancer is a life-threatening disease and as such has implications for the whole of the adolescent’s life.Reference Grinyer24 Besides the physical effects of the disease, there are psychological effects due to the gravity of the illness. The review of the literature has identified that amongst the psychological challenges; there is uncertainty and fear round the status and progression of the cancer. Issues such as body image and appearance have a profound effect on the adolescent. The literature suggests health professionals need to be trained in such areas to give the appropriate care and support. Sexuality and fertility has also been highlighted as an area of major concern to adolescents. Again there is a need for health professionals to be sensitive to the needs of the adolescent and the family. It has been identified that hopefulness and a positive attitude by patients, families and the multi-disciplinary team contribute to positive outcomes.

Psychosocial needs of adolescents are interrelated and dynamic. They are continually changing throughout the illness. A young person’s social networks play a major role in their well being, and this includes members of their family and their peers. If the cancer journey can be understood better through young adults own accounts, the provision of appropriate care and services may contribute to the improvement of outcomes.Reference Grinyer24 Specialist teenage cancer units are the ideal setting to provide psychological care and meet the needs of the adolescent. This has also been a recommendation by the government who state that there needs to be a provision of services that is age appropriate to meet the psychosocial needs of adolescents.10

In clinical practice, there are now services in place to meet the provision of young adults, with the recruitment of social workers and activities coordinators. These roles can contribute to the improvement of outcomes in the cancer journey. It is evident that we are heading in the right direction towards providing adolescents with appropriate care and support by nursing them in specialist units with the appropriate members of the multi-disciplinary team being actively involved in the care. Nurses play a key part in providing psychosocial care as they are primarily the ones who deliver the daily care and can be used as a mediator between the multi-disciplinary team. Ultimately this can improve the adolescents care throughout their cancer journey.