The Rolling Stones are one of the most critically and commercially successful acts in rock music history. The band first rose to prominence during the mid-1960s in the UK, and in the USA as part of what Americans call the “British Invasion” – an explosion of British pop ignited by the UK success of the Beatles in 1963 and their storming of the American shores and charts in early 1964 (see Figure 1.1). The Beatles and the Stones were part of a fab new cohort of mop-topped combos that also included the Animals, the Dave Clark Five, Gerry and the Pacemakers, the Yardbirds, the Zombies, the Kinks, the Who, the Hollies, Herman’s Hermits, and even Freddie and the Dreamers. However much comparisons between the Beatles and the Stones may irritate the faithful of both groups, the similarities and differences can nevertheless be useful. Place of origin matters: The Beatles were not the first pop act from Liverpool to hit it big in London, but they were perhaps the first not to hide their northern roots. Although Brian Jones was from Cheltenham (Gloucestershire), the Stones as a band were, by contrast, from London. Songwriting factors in: John Lennon and Paul McCartney were writing together even before the Beatles were a band, while Mick Jagger and Keith Richards did not start writing until after the Stones had already begun their careers together. Commercial success is also worth noting: The first Beatles No. 1 hit single in the UK was “Please Please Me,” released in March 1963; the first Stones UK No. 1 was “It’s All Over Now,” released in August 1964. “I Want to Hold Your Hand” topped the American charts in late January and February 1964; the Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” hit the top of the US charts in the summer of 1965. The most important distinction between the two bands – and the one that probably tells us the most about the stylistic distance between them – has to do with early influences. The Beatles were very much a “song band,” focused mostly on pop songs and their vocal delivery. And while Jagger and Richards were fans of the 1950s rock and roll of Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly, they were also students (along with Brian Jones) of American blues. As a result, the Stones’ music is often more “rootsy,” at times placing more emphasis on expression than on polish.

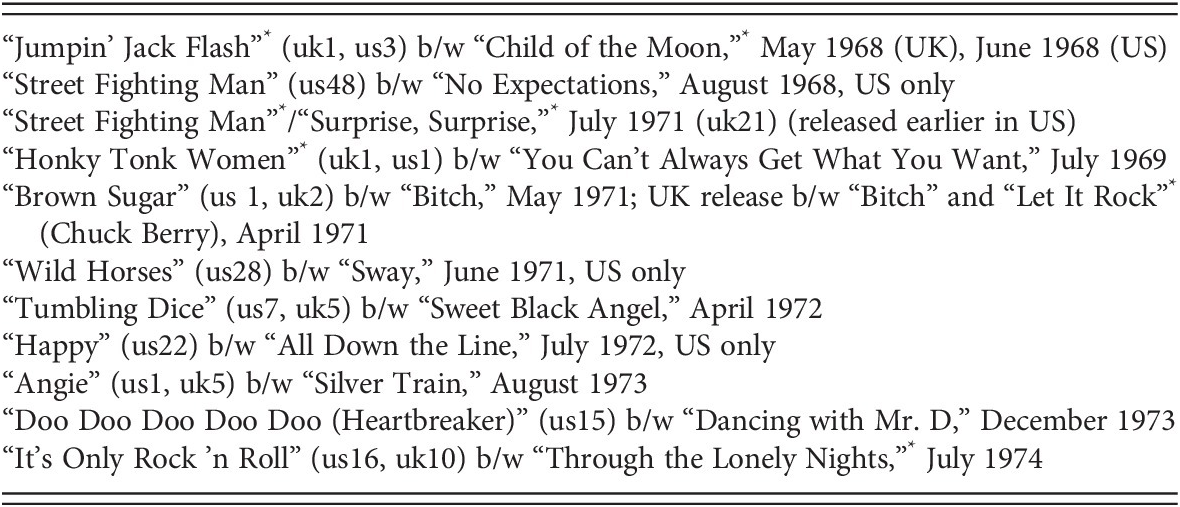

Figure 1.1 The Rolling Stones in Paris, 1964 (Charlie Watts is absent from the photo).

This chapter provides a broad survey of the Stones’ music over their first dozen years, beginning with the band’s earliest recordings in 1963 and extending to It’s Only Rock ’n Roll of 1974.1 Its purpose is to provide a historical context for several of the chapters that follow and to sketch an outline of the band’s releases and stylistic development over this period. As we shall see, the Stones emerged out of a small London blues scene to explore many styles over these twelve years. The period from 1963 through the end of 1967 – from “Come On” to Their Satanic Majesties Request – finds the Stones becoming increasingly ambitious musically, relying more and more on their own songwriting while following, and at times fueling, a practice among rock bands during the mid-1960s that emphasized innovation and experimentation. If Their Satanic Majesties Request represents the culmination of these early years of stylistic development, Beggars Banquet of 1968 marks the beginning of what would become the band’s most productive years, as the Stones balance the musical ambition and accomplishment of their previous music with a return to blues, country, and rhythm and blues influences, producing a series of albums and singles that have come to define – for fans and critics alike – the classic Stones sound. The first dozen years of the band’s history can thus be divided into two arcs of stylistic development: the period from 1963 to 1967, which is driven by increasing musical and artistic ambition; and the period from 1968 to 1974, which is characterized by striking a distinctive balance between musical ambition and stylistic tradition.2

Students of the Blues and Early Singles, 1962–63

What would become some of the most internationally celebrated music in rock history, performed in stadiums and arenas around the world, started from a desire to recreate American blues in a few small London clubs in the early 1960s. The Beatles spent their early years performing in Liverpool and Hamburg, often playing long hours and performing sets filled with their versions of American hits.3 The Stones, by contrast, developed their musical skills in the London blues revival scene of the early 1960s, far from the center of UK pop and mostly off the commercial radar. Since the mid-1940s, there had been a significant British interest in markedly American styles such as jazz, folk, and blues. By the late 1950s, the “trad” jazz scene had developed in the UK, led by performers such as Acker Bilk, Kenny Ball, and Chris Barber – the “three Bs.”4 Grounded more in Dixieland jazz than in the American bebop of the time, these British musicians were often dedicated students of American recordings. In the second half of the 1950s, a skiffle craze hit the UK, led by guitarist/vocalist Lonnie Donegan, whose “Rock Island Line” added a big beat to an American folk classic and became a hit not only in the UK but also in the USA. Like many other British musicians interested in American music, Donegan developed into an expert on American folk, reportedly scouring every possible source for information and recordings, including the library in the American Embassy in London.5 British enthusiasm for the blues on the London scene was led by guitarist Alexis Korner and harmonica player Cyril Davies.6 Their band, Blues Incorporated, began playing Sunday nights at the Ealing Club in March 1962 and in May took over Thursdays at the Marquee Club.7 Both Korner and Davies were at least ten years older than most of the young musicians they would influence, including not only Jagger, Richards, Jones, and Watts, but also Jack Bruce, Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker, Paul Jones, Eric Burdon, John Mayall, and Jimmy Page.8 The musical approach of Blues Incorporated is accurately represented on the band’s R & B at the Marquee album, recorded in June 1962 and released in November.9 This recording features a mix of originals with versions of blues classics based on recordings by Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Lead Belly. Blues Incorporated plays faithfully in the late 1950s American electric blues style without being slavish imitators, turning in a series of convincing performances that might easily be mistaken for authentic Chicago blues tracks.10

The Rolling Stones began, at least as far as Brian Jones was concerned, as a band very much in the mold of Blues Incorporated.11 The band’s first gig was at the Marquee, filling in for Blues Incorporated on the bill also featuring a band quickly formed by singer Long John Baldry.12 Bassist Bill Wyman joined the Stones in December 1962, with Charlie Watts (who had played drums with Blues Incorporated but quit to return to school) joining in January 1963. In February the Stones began their residency at the Crawdaddy Club, initially managed by Giorgio Gomelsky. In April, just two months into those gigs, a young Andrew Loog Oldham heard the band for the first time at the Crawdaddy, and by May he and senior partner Eric Easton had signed the Stones to both a management deal and a recording contract with Decca.13 The Rolling Stones’ first single, a version of Chuck Berry’s “Come On” (Chess Records, 1961) was released in the UK in June 1963 – less than a year after the band had played their first gig at the Marquee. That début single, which rose only as high as No. 38 in the UK, featured a version of Willie Dixon’s “I Want to Be Loved” on the B side – a song that had been recorded by Muddy Waters (Chess, 1955). The two sides of this first single clearly announce who the Stones will be over the next few years: a band pursuing pop appeal while also retaining a strong blues sensibility.

The path to the Stones’ second single perhaps reveals more about their aspirations for commercial success than about their blues roots. In July 1963, the band recorded Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller’s “Poison Ivy” (originally released by the Coasters on Atlantic Records in 1959), which was to be issued as the follow-up to “Come On” in August.14 But Oldham felt the track was not strong enough; he withdrew plans for its release and drafted Lennon and McCartney to write “I Wanna Be Your Man” for the Stones. Released in November 1963, this second single rose to a promising No. 12 in the UK, establishing the Stones as rising stars on the British pop scene. The Beatles also released a version of this song on With the Beatles, with Ringo singing lead. The contrast between the blues-driven, rootsy intensity of the Stones version and the commercial polish of the Beatles track provides a succinct measure of the stylistic distance between these two groups. The record also provides, on its B side “Stoned,” an early instance of the band recording its own original material. This mostly instrumental track is based loosely on “Green Onions,” a 1962 hit for Booker T. and the MGs. The Stones, however, credit songwriting to Nanker Phelge – a pen name given to songs “written” by all of the band members.15 Subsequent early Stones releases would include additional Nanker Phelge songs, which were often based on specific tracks written by others.

Singles and Albums, 1964–65

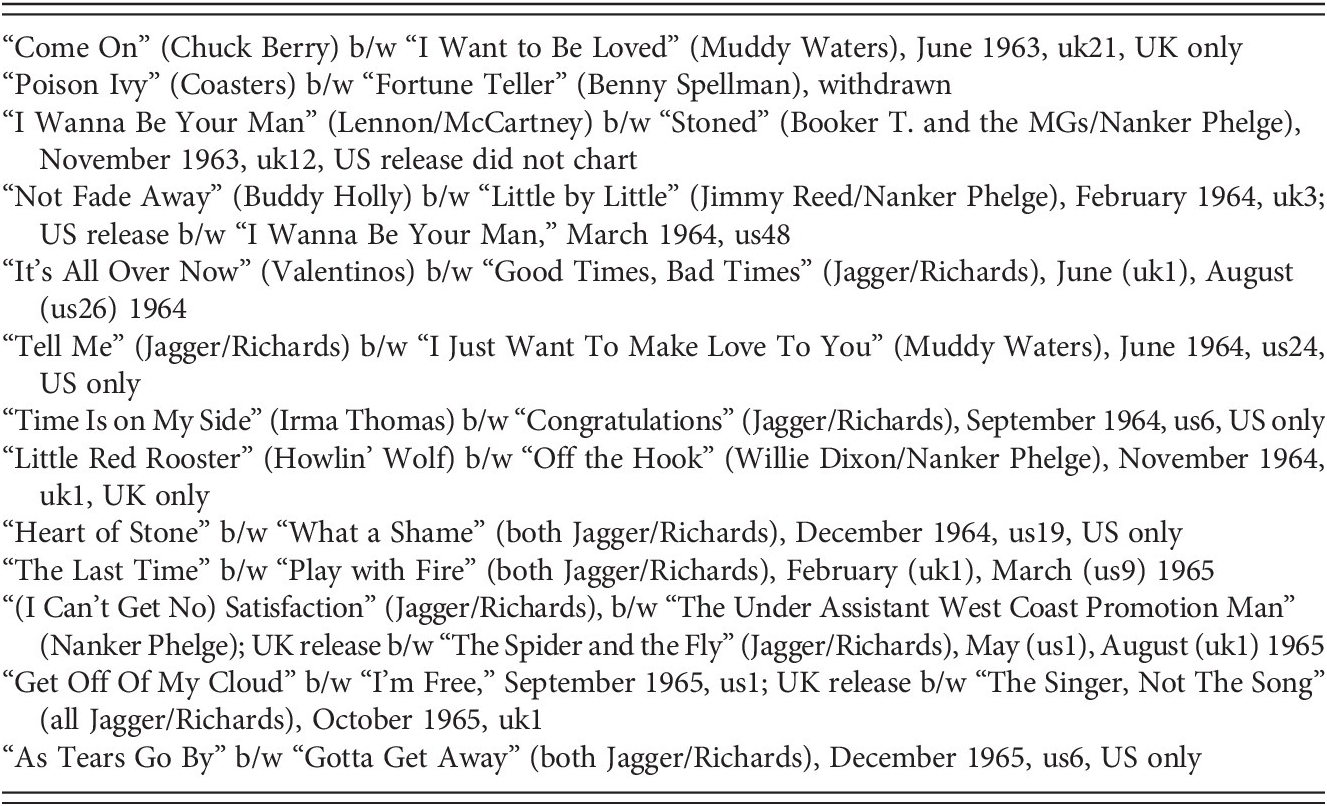

In January 1964 the Rolling Stones had their first success on the top of the charts: The EP The Rolling Stones (containing four tracks, including the previously withdrawn “Poison Ivy”) topped the UK charts. This was followed by the British release in February of “Not Fade Away,” a Buddy Holly/Norman Petty song from 1957. The B side was “Little by Little,” another Nanker Phelge song, this time based on Jimmy Reed’s “Shame, Shame, Shame” (Vee-Jay Records, 1963). This third single went to No. 3 in the UK, and when released in the USA in March with “I Wanna Be Your Man” as the B side, rose to No. 48 – the Stones’ first chart appearance in the States.16 Aside from the songs attributed to Nanker Phelge – which, as already noted, were not particularly original – the first three singles and first EP featured no songs written by Jagger and Richards. Table 1.1 lists the Rolling Stones’ singles from 1963 to 1965. Note that it is with the fourth single (not counting the aborted release of “Poison Ivy”) that a Jagger/Richards song, “Good Times, Bad Times,” is included, though as a B side. “Tell Me” marks the first Jagger/Richards song to appear as the A side of a single, though it was released in this way only in the USA. After this, with only one exception, the remainder of the singles listed in Table 1.1 feature at least one, and sometimes two, songs written by Jagger and Richards. Note also that in the fall of 1964 the band released “Time Is on My Side” in the USA (going to No. 6), but released “Little Red Rooster” in the UK. “Rooster” had been released by Howlin’ Wolf on Chess in 1961, and the release of this slow blues number as a pop single was a risky move – though it paid off with a No. 1 hit. It seems likely that with the clear pop emphasis of the previous singles, the band was eager to reestablish its blues-revival bona fides with “Rooster,” especially at home in the UK.17 Table 1.1 provides a good picture of how, over the period 1963–65, the Stones moved from versions of songs previously recorded by others to Jagger/Richards originals.

Table 1.1 Rolling Stones singles, 1963–65

Note: Chart numbers refer to A side of each single release (first-listed song). Names in parentheses indicate original artist recording that song, except in the case of “Jagger/Richards,” which indicate the songwriters. Parentheses marked “Nanker Phelge” also include the original recording artist who provided a model for that song.

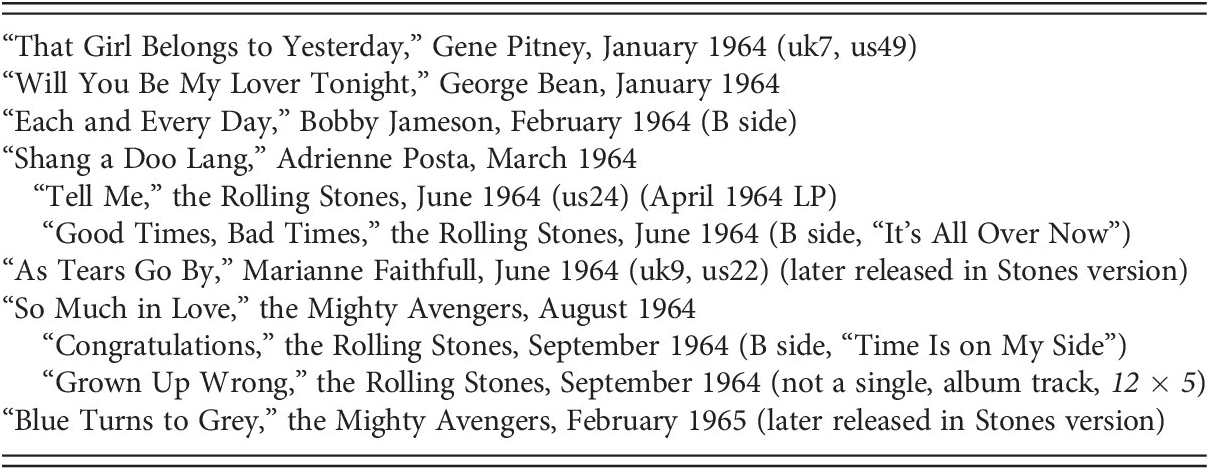

The absence of Jagger/Richards songs in the first batch of singles, as well as on the first EP, might suggest that Jagger and Richards were either not writing much or were unwilling to release what they may have been writing.18 As can be seen in Table 1.2, however, Jagger and Richards were indeed writing during this period, though these songs were released by other artists, two as early as January 1964. Among these songs, the most interesting is Marianne Faithfull’s recording of “As Tears Go By,” which (as seen in Table 1.1) the Stones released in their own version in late 1965. The use of chamber strings in the Stones version seems to be influenced by the Beatles’ “Yesterday,” but the philosophical quality of the song’s lyrics actually predates McCartney’s “Yesterday” lyrics by a year. Still, the character of these Jagger/Richards songs recorded by others suggests that the Stones believed that material to be too pop-oriented for the band. And the timing of those first songs, released in early 1964, suggests that the October 1963 meeting with Lennon and McCartney that produced “I Wanna Be Your Man” helped prod Jagger and Richards into writing their own music.19

Table 1.2 Early Jagger/Richards songs

Note: Indented singles are Rolling Stones releases.

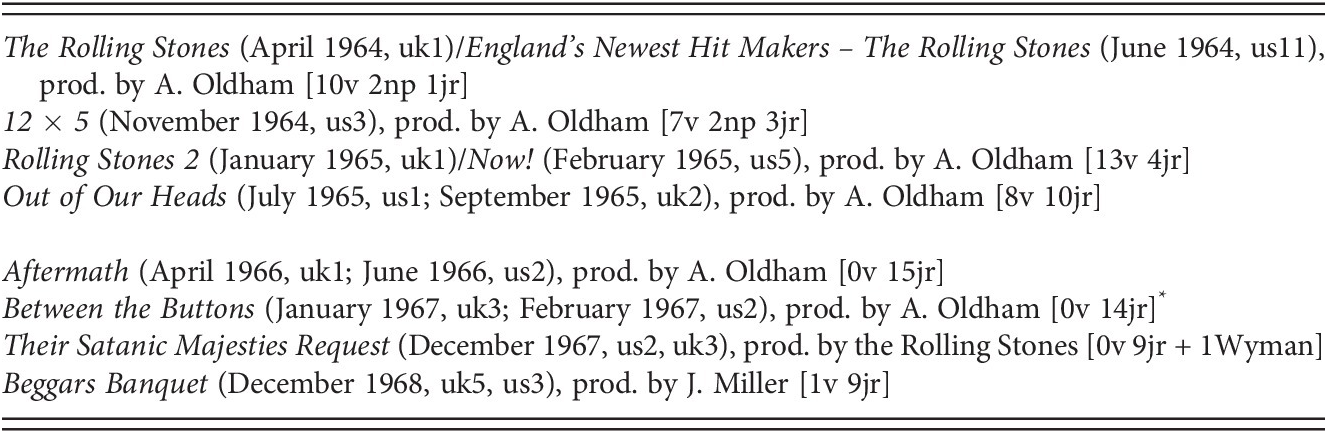

As Table 1.1 suggests, the differences in UK and US releases can make the chronological organization of the Stones’ singles difficult – or at least complicated. The problem is even more pronounced when it comes to the Stones’ albums, at least up to Their Satanic Majesties Request of December 1967. Albums with the same name, for instance, will contain a different collection of songs, while albums (or EPs) that appeared on one side of the Atlantic were never released on the other. Table 1.3 lists eight “album projects,” with each album project representing the combination of all songs that appeared on the US or UK versions of a given album. For example, the début LPs in the USA and UK together include thirteen tracks; eleven appear on both albums, while one appears on the US version only (“Not Fade Away”) and another appears on the UK version only (“Mona (I Need You Baby)”). The combination of the UK and US versions of Out of Our Heads totals eighteen tracks, with six held in common and six appearing only on one or the other. This approach to organizing the Stones’ releases has the advantage of grouping together tracks that were recorded at about the same time, allowing the development of the band’s style to be tracked from one album project to the next.20 There are some songs along the way that get left out using this general organizational scheme, but these are few. There are also albums such as December’s Children (December 1965, USA only), Big Hits (High Tides and Green Grass) (March 1966, USA; November 1966, UK), and Flowers (June 1967, USA only) that are left out of this listing; such albums are primarily compilations that introduce only a few new tracks, with these new recordings placed side by side with ones recorded much earlier and thus blurring the band’s stylistic development.21

Table 1.3 Rolling Stones album projects, 1964–68

| The Rolling Stones (April 1964, uk1)/England’s Newest Hit Makers – The Rolling Stones (June 1964, us11), prod. by A. Oldham [10v 2np 1jr] |

| 12 × 5 (November 1964, us3), prod. by A. Oldham [7v 2np 3jr] |

| Rolling Stones 2 (January 1965, uk1)/Now! (February 1965, us5), prod. by A. Oldham [13v 4jr] |

| Out of Our Heads (July 1965, us1; September 1965, uk2), prod. by A. Oldham [8v 10jr] |

| Aftermath (April 1966, uk1; June 1966, us2), prod. by A. Oldham [0v 15jr] |

| Between the Buttons (January 1967, uk3; February 1967, us2), prod. by A. Oldham [0v 14jr]* |

| Their Satanic Majesties Request (December 1967, us2, uk3), prod. by the Rolling Stones [0v 9jr + 1Wyman] |

| Beggars Banquet (December 1968, uk5, us3), prod. by J. Miller [1v 9jr] |

Note: UK release date is listed first, with US release listed second.

v = version of a song previously recorded by another artist.

np = song attributed to Nanker Phelge.

jr = song written by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards.

* According to Bill Wyman, the first album to be conceived as an album and not simply as a collection of singles.

In addition to identifying the eight Stones album projects from 1964 to 1968, Table 1.3 provides the number of songs written by Nanker Phelge and Jagger/Richards on each of these. Note that the first four album projects are dominated by Stones versions of music written by others.22 The first album project contains ten versions, two Nanker Phelge tracks (based, as noted above, on the music of others but not versions, strictly speaking), and one Jagger/Richards song. While the number of Jagger/Richards songs increases with each subsequent album project, the fourth, Out of Our Heads, still contains eight versions of songs previously recorded by others. A dramatic and important change occurs with the fifth album project, Aftermath, which contains Jagger/Richards songs exclusively – a feature continued in the sixth album project, Between the Buttons. Their Satanic Majesties Request includes one song by Bill Wyman but is otherwise all Jagger and Richards. Beggars Banquet settles into what will become the model for the Stones – one version among otherwise exclusively Jagger/Richards material. Viewed against the rest of the Stones recordings through the years, the first four albums stand out for their dependence on the music of others.

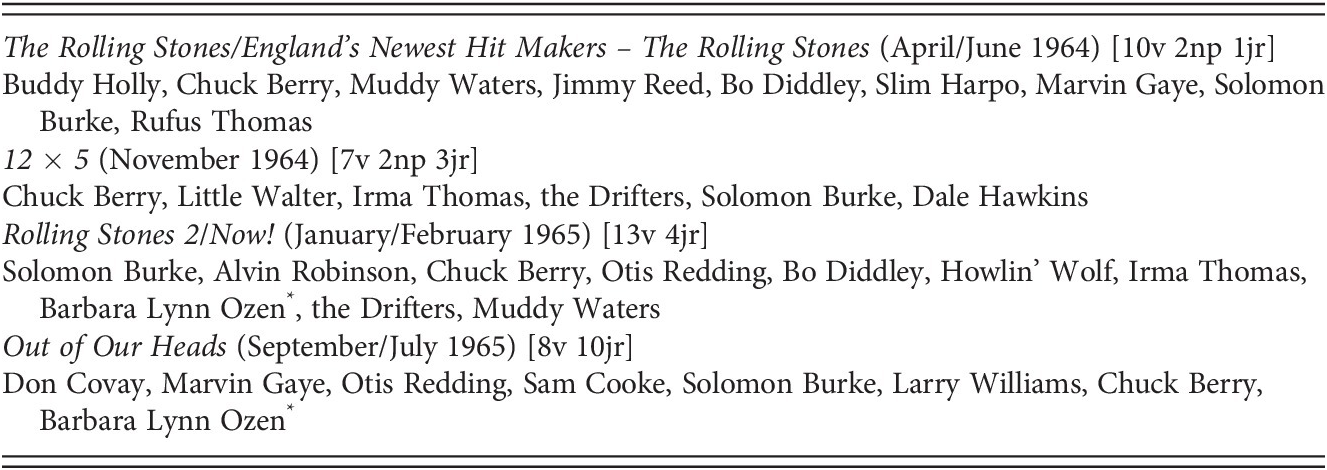

Table 1.4 lists the original artists who previously recorded the songs appearing on the first four album projects. These album versions provide us with a general sense of the music the Stones seem to have enjoyed most during these years and the names listed are almost entirely those of American rhythm and blues artists.23 Two of the hit singles from 1965 (see Table 1.1), while credited to Jagger and Richards, also reinforce this strong American R&B influence. “The Last Time” is heavily indebted to the Staple Singers’ 1954 single “This May Be the Last Time,” while “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” draws on Martha and the Vandellas’ “Nowhere to Run,” released in early 1965.24 With these songs, the Nanker-Phelge practice of adapting the music of others seeps from B sides and album tracks into Jagger and Richards A sides, and suggests that the many versions that appear on Stones albums and singles through 1965 played an important role in the band’s stylistic development. The complete turn away from versions that first occurs in 1966 with Aftermath thus marks an important shift that divides the 1963–67 period roughly into two parts: 1963–65 and 1966–67.

Table 1.4 Versions on the first four album projects (original artists)

| The Rolling Stones/England’s Newest Hit Makers – The Rolling Stones (April/June 1964) [10v 2np 1jr] |

| Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed, Bo Diddley, Slim Harpo, Marvin Gaye, Solomon Burke, Rufus Thomas |

| 12 × 5 (November 1964) [7v 2np 3jr] |

| Chuck Berry, Little Walter, Irma Thomas, the Drifters, Solomon Burke, Dale Hawkins |

| Rolling Stones 2/Now! (January/February 1965) [13v 4jr] |

| Solomon Burke, Alvin Robinson, Chuck Berry, Otis Redding, Bo Diddley, Howlin’ Wolf, Irma Thomas, Barbara Lynn Ozen*, the Drifters, Muddy Waters |

| Out of Our Heads (September/July 1965) [8v 10jr] |

| Don Covay, Marvin Gaye, Otis Redding, Sam Cooke, Solomon Burke, Larry Williams, Chuck Berry, Barbara Lynn Ozen* |

Singles and Albums, 1966–67

The practice of abandoning versions of songs recorded by others that marks Aftermath and the album projects that follow can also be seen clearly in the singles released by the Stones in 1966–67 (see Table 1.5); all but one of the songs appearing on these releases is written by Jagger and Richards, and that one song not credited to Jagger and Richards was written by Bill Wyman. These singles mostly rose into at least the top ten in the USA and UK, though the second half of 1967 finds the band struggling somewhat in the US charts due to the relatively poor showing of “We Love You” (No. 50) and “She’s a Rainbow” (No. 25), while Wyman’s “In Another Land” (No. 87) barely made a dent. The three Stones album projects during the same period, however, were strong commercial successes (see Table 1.3). The summer of 1967 was marked by legal and business problems for the band. At various points Jagger, Richards, and Jones all faced drug charges, while simultaneously the band’s relationship with manager and producer Oldham was deteriorating. While some critics believe these events took a heavy toll on the band’s music, at the very least they were a distraction that might partly explain the temporary dip in the group’s success.25

Table 1.5 Rolling Stones singles, 1966–67

Note: Chart numbers refer to song they immediately follow.

All songs written by Jagger and Richards except where noted.

In my chapter focused on Beggars Banquet, I detail the band’s increased musical ambition in the period from about 1965 to the release of Their Satanic Majesties Request in late 1967. During these years we find the Stones employing novel instrumentation (sitar, dulcimer, Mellotron, and more) and moving away from the two guitars, bass, drums, and vocals combo approach characteristic of the music from the 1963–64 period. They blend aspects of classical music into their style, by both the use of instruments associated with it (harpsichord, strings) and employment of harmonic and melodic materials that reference classical practice (“Ruby Tuesday,” “She’s a Rainbow”). The lyrics are at times philosophical and often contain evocative imagery. During the same time, it must be noted, the band also produced driving rock tracks such as “19th Nervous Breakdown,” “Mother’s Little Helper,” and “Let’s Spend the Night Together.” Thus, the overall arc from 1963 is first marked by a decisive shift towards Jagger/Richards songs, and then by a tendency to explore a variety of styles and instrumental combinations. Their Satanic Majesties Request is a point of arrival that prepares the way for Beggars Banquet and the Stones music that follows.

Singles and Albums, 1968–74

The Stones’ move towards increasingly ambitious approaches to their music leading to 1967 was not unusual in rock music of the mid-1960s. The Beatles’ album releases of 1967, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Magical Mystery Tour, combined with the singles “Penny Lane” and “Strawberry Fields,” marked a high point of musical ambition for them, as had the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds and “Good Vibrations” of 1966.26 At about this same time, significant changes were afoot in the music business, especially in the United States. The emergence of psychedelic culture into American mainstream culture during 1967’s Summer of Love brought with it an emphasis on albums rather than singles: Singles would come to be the format for AM radio – devoted to hit records in much the same way pop radio had been earlier in the decade – while the burgeoning FM band, freer in approach and at least initially less driven by advertising, would be the home for album tracks. FM radio and album-oriented rock became the music of college-age fans; pop singles on the AM band were targeted at teens and pre-teens. This change in the American music business impacted the Rolling Stones, who began to think more in terms of albums than singles.27

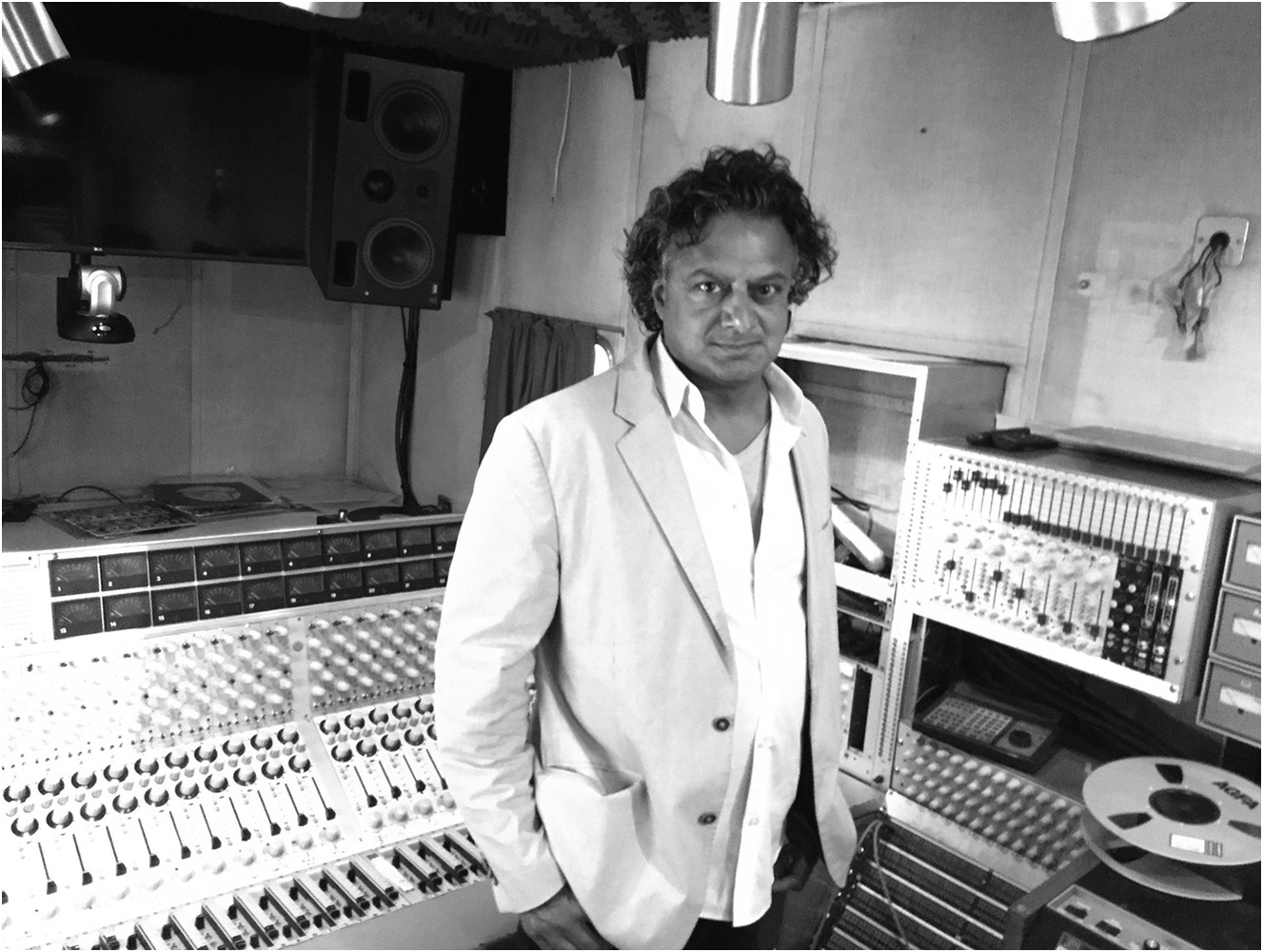

Table 1.6 provides a listing of Stones singles from the 1968–74 period, while Table 1.7 lists the albums from the same years. A comparison with Tables 1.1, 1.3, and 1.5 above reveals how the pace of these later releases slowed during the late 1960s and into the 1970s. In the 1963–67 period, for instance, the band released three or four singles a year and usually two albums (not counting compilation albums). Table 1.6 shows that this rate slowed to about two releases a year for singles, and Table 1.7 lists roughly one album per year (with no album released in 1970). This pattern conforms to a general practice among other bands during the same period, as groups took longer to record albums. It is also worth noting that for these years there is no need to invoke the album project scheme to organize the album content, since UK and US albums were identical in terms of tracks included, perhaps owing to this new focus on the album as a whole. Table 1.6 also indicates that Stones singles in the first half of the 1970s were all tracks contained on the albums released during the same general period, another indicator that singles were no longer the band’s primary focus.

Table 1.6 Rolling Stones singles, 1968–74

| “Jumpin’ Jack Flash”* (uk1, us3) b/w “Child of the Moon,”* May 1968 (UK), June 1968 (US) |

| “Street Fighting Man” (us48) b/w “No Expectations,” August 1968, US only |

| “Street Fighting Man”*/“Surprise, Surprise,”* July 1971 (uk21) (released earlier in US) |

| “Honky Tonk Women”* (uk1, us1) b/w “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” July 1969 |

| “Brown Sugar” (us 1, uk2) b/w “Bitch,” May 1971; UK release b/w “Bitch” and “Let It Rock”* (Chuck Berry), April 1971 |

| “Wild Horses” (us28) b/w “Sway,” June 1971, US only |

| “Tumbling Dice” (us7, uk5) b/w “Sweet Black Angel,” April 1972 |

| “Happy” (us22) b/w “All Down the Line,” July 1972, US only |

| “Angie” (us1, uk5) b/w “Silver Train,” August 1973 |

| “Doo Doo Doo Doo Doo (Heartbreaker)” (us15) b/w “Dancing with Mr. D,” December 1973 |

| “It’s Only Rock ’n Roll” (us16, uk10) b/w “Through the Lonely Nights,”* July 1974 |

Note: Chart numbers refer to song they immediately follow.

All songs written by Jagger/Richards except where noted.

* Indicates track that did not appear on studio album at approximate time of release.

Table 1.7 Rolling Stones albums, 1968–74

| Beggars Banquet, December 1968 (us5, uk3), prod. by J. Miller [1v 9jr] |

| Robert Wilkins, “Prodigal Son” |

| Let It Bleed, November 1969 (us3), December 1969 (uk1), prod. by J. Miller [1v 8jr] |

| Robert Johnson, “Love in Vain” |

| Sticky Fingers, April 1971 (us1, uk1), prod. by J. Miller [1v 9jr*] |

| Fred McDowell, “You Gotta Move” |

| Exile on Main Street, May 1972 (us1, uk1), prod. by J. Miller [2v 16jr†] |

| Slim Harpo, “Shake Your Hips,” and Robert Johnson, “Stop Breaking Down” |

| Goats Head Soup, August 1973 (us1, uk1), prod. by J. Miller [0v 10jr] |

| It’s Only Rock ’n Roll, October 1974 (us1, uk2), prod. by the Glimmer Twins (Jagger/Richards) [1v 9jr] |

| The Temptations, “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg” |

As noted in the discussion of the Stones’ album projects during the 1964–68 period (and shown in Table 1.3), Beggars Banquet contains one version of a song previously recorded by another artist, Robert Wilkins’ “Prodigal Son.” Table 1.7 extends the listing of Stones albums to 1974. Note that each album contains one version with the remaining tracks being Jagger/Richards songs (except where indicated). The exceptions are Exile on Main Street, a double album that includes two versions, and Goats Head Soup, which includes none. The songs the band rework clearly gravitate toward the American rhythm and blues tradition (the songs and artists are listed in Table 1.7). While the first four album projects had included significantly more versions than these later albums, the relatively consistent practice found on these releases beginning in 1968 shows a significant return to roots for the band, especially considering the absence of such versions on the 1966–67 albums. A comparison between Tables 1.3 and 1.7 also reveals that the albums from the 1964–67 period were almost all produced by Oldham, while those from the 1968–74 period were mostly produced by Jimmy Miller.28 The exceptions come at the end of each period, as Their Satanic Majesties Request is recorded during the break-up with Oldham (production credit is given to the band and Oldham’s name is excluded), and It’s Only Rock ’n Roll is produced by Jagger and Richards. And while production during the period up through 1967 was marked by increasing experimentation, often fueled by Jones’ introduction of instruments new to the band’s sound and novel in a pop and rock context, Miller’s productions more often exploited the virtuosic playing of Taylor, as well as that of other musicians such as saxophonist Bobby Keys.29

As mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, the Stones albums from the 1968–74 period strike a balance between the version-heavy releases of 1963–64, the musical ambition of 1965–67, and a return to a distinctive directness of expression that reaffirms their roots in rock and roll, rhythm and blues, and country music. Indeed, each of the six albums from Beggars Banquet to It’s Only Rock ’n Roll includes a relatively broad stylistic range of material, from acoustic ballads to blues-based rockers, from ambitious tracks that employ aspects of classical or psychedelia to those that highlight instrumental virtuosity, and from tracks that display a folk influence to those that engage the gospel tradition. It is also worth noting that while the Beatles began to come into their own, each as solo artists, during The White Album (1968), at about the same time the Stones developed a band sound that broke free of the influence of the Beatles, and ironically right after the most seemingly imitative album (Majesties).30 Other chapters in this collection delve into these Stones albums in more detail; it is nevertheless worth emphasizing here how significant this series of albums from the 1968–74 period are in securing the Stones’ prominent place in the history of rock music. They are a logical point of stylistic arrival considering the music from 1963–67 that preceded them. And they are the musical points of reference for all of the band’s music that followed.

Fifty-seven years together is a remarkable achievement for any combination of humans – in marriage; siblings; a company; not least an artistic collaboration with a core of three men, together from the fresh optimism of their twenties to the deep-lined wisdom of their seventies. It is only natural to divide such an eon into more manageable eras and chapters in order to discuss the results of such a collective. This is the organization I adopted in my most recent book about the Rolling Stones, Rocks Off: 50 Tracks that Tell the Story of the Rolling Stones (New York, 2013), in which discussions of the songs are grouped into three large sections corresponding to the band’s three guitar players who served as Keith Richards’ counterpoints over the band’s history: Brian Jones, Mick Taylor, and finally, Ron Wood. Each of these guitarists had a significant impact on the sound of the Stones, and most longtime fans view the history of the group as divided along these lines. Though there have been many other people contributing to over a half-century of Stones recordings and tours, I will be concentrating here on the musicians who made indelible impacts on Stones records, especially those who were with the band for multiple years and albums.

Guitar Slinger One: Brian Jones

For many of the original Stones fans, nothing beats the Brian Jones years, and a number who hold this opinion stopped paying attention to the band around the time of the 1969 Hyde Park Concert, which served as the coming-out party for the twenty-year-old Taylor. This type of fan values the blues purism of the early Stones and their rock and roll roots in Chuck Berry the most, while other fans of this period emphasize the sonic textures and diverse musical styles that the multi-instrumentalist Jones brought to the records of the mid-sixties. In the early days of the band, Richards and Jones spent hours trying to discern the various parts played by the musicians in their pooled record collection, but what really excited them was the overall sound of the music, the effect of the whole (ensembles and vocalists) that was greater than the sum of the individual parts. This is the direction that the Stones themselves followed on their own earliest recordings. The twin guitars of Richards and Jones are intertwined and almost indistinguishable from each other on 1964–66 albums like The Rolling Stones (UK, 1964), England’s Newest Hit Makers (USA, 1964), 12 × 5 (1964), Out of Our Heads (separate UK and US versions, both 1965), and December’s Children (1965). Their producer for these records was the inexperienced Andrew Loog Oldham, who was deeply under the influence of his mentor, Phil Spector. The Stones began to achieve more clarity in their recordings at Chess Studios in Chicago and RCA Studios in Hollywood, though Oldham’s production tastes leaned towards large amounts of reverb. So the Stones’ records of this period are generally awash in echo, and tend to have a dark and murky wall of sound, while Jagger’s vocals struggle to climb above it all to be heard.

The listening experience, however, is exhilarating. A prime example of the Jones and Richards guitar interplay can be heard on the original up-tempo blues, “Little by Little.” We know Richards is playing the brighter of the two electric guitars, because it is the one that slips into a solo at the beseeching of Jagger, who yells, “All right, Keith, come on!” During this solo, we can more clearly discern that Jones is playing the roots of the chords and some fine blues riffs. It is as if the two divide up the frequency range of the electric guitar, with Jones taking the low notes and Richards taking the high strings, instead of more clearly delineated rhythm and lead guitar parts.

The Stones, alongside the Beatles, set the template for the two-electric-guitar model for rock and roll bands. For most prior combos, a guitar was backed by drums, a bass, and maybe a piano. Or if there were two guitars, one was generally an acoustic strumming the rhythm with a lead player on electric (or in country and western, electric lap steel or pedal steel). A classic example would be the early Elvis Presley band with Scotty Moore playing single-note lines on his electric while Elvis strummed an acoustic. And with the Beatles, it was George Harrison who usually played the solos and riffs, while John Lennon was busying himself with strumming and singing. The Stones, though, were all about two guitarists playing interlocking rhythms and riffs, what Richards would later often refer to as “the ancient form of weaving.” It was a dynamic that he felt went missing for much of the Mick Taylor era, at least in live performances.1 But it clicked back into place in full force with Ron Wood joining the band.

Another early recording at Regent Sound Studios was the Stones’ version of Slim Harpo’s “I’m A King Bee,” which offers a more delineated rhythm/lead guitar split. Here is Richards strumming an acoustic bed over the sturdy laid-back groove set down by Charlie Watts and Bill Wyman, who slides his note up to replicate the buzz of a bee. Jones breaks out of his low-note riffing with a bottleneck slide, stinging us with his high notes. With one fewer electric guitar competing for space and a relatively slower song, the track is one of the crisper mixes from the band’s early period: the drums cut through, the acoustic guitar is clear, and the vocal is heard up front and present. The bass and Jones’ riffs weave around each other in the same frequency range.

A more plaintive version of his slide guitar work is on “No Expectations,” from Beggars Banquet (1968), in which Jones offers a mournful, bottleneck part on an acoustic guitar. While Jagger’s vocal is sublimely doleful and heavy with emotion, Jones does more than merely underscore the melancholy; his opening guitar lines set the tone of the song more than words themselves could. Though Richards described Jones’ minimal contributions to Let It Bleed (1969) – a percussion part on “Midnight Rambler” and autoharp on “You Got the Silver” – as “a last flare from the shipwreck,” it is really this single slide part that was Jones’ last cry.2

These two trademark slide guitar parts are bookends to a rich palette of colors that Jones brought to the Stones’ recordings of the 1960s. He was easily bored, did not write music for the band, and did not sing. On each successive record, Richards increasingly overdubbed multiple guitar parts while Jones explored different instruments. His sense of wonder was piqued when the band was let loose at the RCA Studios in Hollywood, with huge rooms full of exotic instruments, leading to his playing sitar on “Paint It, Black,” dulcimer on “Lady Jane” and “I Am Waiting,” marimba on “Under My Thumb,” and harpsichord and koto on “Ride on Baby.”3 Though he has no songwriting credits on Aftermath (1966), it’s as much a Brian Jones record as one by Jagger/Richards.

Jones’ spirit of experimentation mirrored what was occurring across town at Abbey Road Studios on Beatles recordings. We must also point to such indelible parts as his woody recorder on “Ruby Tuesday,” use of organ on “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” and of Mellotron (a keyboard that plays tape loops, like an early analog sampler) on “2000 Light Years From Home” and “She’s a Rainbow.” Of course, this experimentation went hand in hand with drug use, and, like many of his colleagues, Jones slid from experimentation to drug abuse, falling into a downward spiral of paranoia and self-medication. He was officially fired in 1969 while the Stones were hard at work on Let It Bleed, and in a matter of days was found dead, his drug-addled body drowned in the swimming pool of his home.

Guitar Slinger Two: Mick Taylor

With most of Let It Bleed completed, the band searched for a suitable replacement. On the recommendation of the Bluesbreakers’ bandleader, John Mayall, the Stones invited twenty-year-old Mick Taylor down for a session. The first track he played on was “Live With Me,” on which he traded licks with Richards in real time at Olympic Studios during the actual tracking. Taylor said that he and Richards clicked immediately on the session, and according to Taylor, they would alternate playing rhythm and lead, but live there was more lead playing, which was given to Taylor.

Thus, the Stones’ sound was changed the instant Taylor was introduced to the band. Richards had played a few concise solos on the late 1960s sessions. One thinks of the memorable cutting solo on “Sympathy for the Devil” and the slowhand blues solo on “Gimme Shelter.” Taylor was already known among guitar fans as a virtuoso blues soloist of the B.B. King, Freddie King, Eric Clapton, and Jeff Beck lineage. The first time the public heard Taylor on a Stones recording, though, was the twangy country bends that introduce the chorus of the “Honky Tonk Women” single. The solo on that track is trademark Richards, with an unhurried pace and economical note choice. While known as a lead player, Taylor also relished the chance to lay down rhythm parts and riffs to suit and support the songs.

It was rather in the live arena that Taylor particularly shone. A lot had changed on the road during the years the Stones had not toured, and by 1969, live sound technology had grown exponentially. Sound systems now could fill arenas with relatively decent sound, with each instrument mic’d up, amplified, and mixed along with the vocals through the large PA speaker stacks that typically flanked the stage. Touring became a big business in and of itself, not just a way to promote records. Bands were now playing “concerts” with sets an hour plus in length. The influence of drugs and musical experimentation was now being played out in live performances as well, from Jimi Hendrix’s incendiary performances at Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 (literally setting his guitar on fire) and Woodstock in 1969, to the Who’s high-volume, instrument-wrecking affairs, and the Grateful Dead’s long jamming takes on psychedelic Americana. Now, the Stones were retooled for this new terrain, with long-form jams like “Midnight Rambler” and the usual encore “Street Fighting Man,” the mini-epic “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” and “Sympathy for the Devil,” which could be stretched out for extended guitar solos. Such songs were reinterpreted each night. On the studio recording of “Sympathy for the Devil,” for example, the only guitar is Richards’ solos. The rest is piano driven. But on the live versions, Richards would generally start a chord progression with Watts tumbling in with a drum fill, Wyman falling in behind, and Taylor playing lead lines when Jagger was not singing.

“Midnight Rambler” provides an interesting case study as a song that Richards labored over in the studio, weaving together a couple of compelling rhythm parts on his own. He perfected the slide part alone over five nights, erasing each previous take and starting anew. Taylor was already playing torrid slide guitar solos in his début performance of the song at his coming-out party, the concert in Hyde Park in the summer of 1969. On the 1969 live album, Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!, Richards starts the song at a faster, galloping pace. Taylor joins him in playing a similar rhythm part, but swinging a bit from the relentlessly steady Richards part. It is the sort of tack that Brian Jones might have taken. The soloing is left for Jagger on the harp over the arrangement’s chugging parts. When the song breaks down in the middle, we can hear Taylor playing tastefully reined-in blues bends, freeing himself a bit more during the crescendo build-up in the final two minutes of the song. But “Midnight Rambler” took on almost operatic proportions over the next few years, so that by 1972 (as seen in the concert film, Ladies and Gentlemen: The Rolling Stones) and 1973 (as heard on the Brussels Affair live album) the song reached lengths of ten to fifteen minutes. As experienced via those recordings, the guitar interplay epitomizes the particular strength of the Richards-Taylor tandem when it was working on all cylinders. Richards launches into some of his Chuck Berry-inspired two-note solos, while Taylor eases back and forth from bluesy single-note hammerings, picked flurries, and bends, into variations of the rhythm parts.

The sustained level of excellence from Sticky Fingers (1971) through Exile on Main Street (1972) offers myriad examples of why the Mick Taylor era is so highly regarded. We get early glimpses of Taylor’s versatility on Sticky Fingers, where at the end of “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” he evokes Carlos Santana with a serendipitously recorded, impromptu, Latin-tinged jam as a coda. We also hear Taylor’s poignant slide and electric riffs interacting with Jagger’s gentle acoustic licks on “Moonlight Mile,” one of the Stones’ most sublimely beautiful ballads. It is a song without a Richards guitar track; Jagger and Taylor handled all the guitar work at the session for the song. As the recording reaches its conclusion, we hear Taylor playing an ascending and descending pentatonic figure that gets picked up and elaborated upon by the string arranger on the recording, Paul Buckminster. It has been argued that Taylor should have received some writing credit for his contributions. What constitutes songwriting as opposed to arranging is a controversial topic among collaborative bands and it was seemingly a sore point for Mick Taylor, an official member of the band. It is easier for session players to accept that their contributions to a song’s arrangement, as hired guns, will not receive songwriting credit. For example, Nicky Hopkins was an almost constant presence on Stones recordings and live performances from 1966 through 1974. His contribution in arranging “Sympathy for the Devil,” transforming it from an ambling folk song into a raging samba, is accurately documented in Jean-Luc Godard’s film One Plus One (later retitled Sympathy for the Devil). In the end, all guitars except Richards’ lacerating solo are stripped away and the song is propelled by Hopkins’ piano and the rhythm section. But Jagger had the chord progressions and seemingly much of the lyric content written before they started. What we witness in the film is how significantly an arrangement can affect the end result of a song. In this case, the final product is about 180 degrees different from how it was originally presented to the group. The case can be made that such substantial arranging warrants writing credit, and over the years Bill Wyman, Mick Taylor, and Brian Jones could have laid claim to such credit, but very few songwriters would agree.

Taylor may actually have added more than arrangement ideas. Such contributions are difficult to extricate and measure when so much of the band’s writing came out of organic jamming. In the end, Taylor’s feelings on the subject were apparently one of the main reasons he decided to leave the Stones. “I’d seen him a few days earlier and he’d spoken excitedly about some songs he’d written with Jagger and Richards that were to appear on It’s Only Rock ’n Roll,” writes Nick Kent referring to the 1974 album. “When I told him that I’d seen the finished sleeve with the song-writing credits and that his name wasn’t featured, he went silent for a second before muttering a curt ‘We’ll see about that!’ almost under his breath. Actually, he sounded more resigned than anything else …”4

Some of Taylor’s final tracks before he left the group are among his finest recorded moments. He did not get many big, soaring opportunities on Exile on Main Street. Most of his work on that record is confined to second rhythm parts and concise solos mixed relatively low dynamically as part of the whole Exile gumbo. But he did receive a writing credit on the smoldering “Ventilator Blues,” which likely means he came up with the song’s insistent main riff, as the song sprung from one of the jams the band had in the basement of Richards’ rented Nellcôte villa on the French Riviera. We also heard Taylor spread his wings on recordings from the subsequent live tour. But on the next two records, Goats Head Soup (1973) and It’s Only Rock ’n Roll (1974), we are treated to heart-melting solos on the songs “Winter,” and “Time Waits for No One,” respectively. On the latter recording, Taylor got to stretch out for more time than was typically budgeted for on Stones studio recordings. For a band that would marinate song ideas in meandering, often directionless jams, the final products tended toward the succinct and economical, in service of the songs themselves. The first song recorded for the It’s Only Rock ’n Roll sessions, “Time Waits for No One,” is the final song on side one of the LP. “There was going to be a space for a guitar solo, it was a first take,” Taylor recalled. “I mean the backing track and the guitar solo is the first or second time we actually ran through the song, so the guitar solo was done live. It’s got a long sort of extended guitar solo at the end, which is because it was a good solo and it’s peaking. That’s how long the track goes on for.”5 The song would serve as the perfect swan song for Taylor, if the last song to actually feature him had not been the even more fitting “Till the Next Goodbye.”

Guitar Slinger Three: Ron Wood

Ron Wood had showed up in Munich to help out on the 1975 Black and Blue sessions, unaware that the Stones were holding auditions for a permanent replacement guitarist to fill the shoes of Taylor. When he arrived, he saw Eric Clapton, who was one of an impressive list of hotshots who had been called into the sessions in Munich (and other dates in Rotterdam). Names commonly associated with these sessions include Irish blues sensation Rory Gallagher, Humble Pie’s Steve Marriott (also famous as singer of the Small Faces), Peter Frampton (formerly of Humble Pie and now a rising solo artist), Muscle Shoals session guitarist Wayne Perkins, Canned Heat’s Harvey Mandel, and Jeff Beck, who claimed he was tricked into auditioning.

It seems that Beck was not the only one unaware of the audition nature of the session. Despite his ties to the Faces, Wood had showed up as if the gig were his to take if he wanted it, knowing that the Faces were floundering while their singer, Rod Stewart, was enjoying superstardom as a solo artist. “Clapton said to me in Munich, ‘I’m a much better guitarist than you,’” writes Wood. “I responded, ‘I know that, but you gotta live with these guys as well as play with them. There’s no way you can do that.’ Which is true. He could never have survived life with the Stones.”6

One of the main criticisms of Ron Wood from his detractors among Stones fans is that he is too much like Keith Richards and does not bring the musicality of Brian Jones or the virtuosity of Mick Taylor. But this misses the point. Wood has shown a significantly wide versatility, able to approximate the 1960s sounds that Jones brought to the table, the bluesy slides and bends that Taylor tracked, while offering distinctive contributions of his own, such as the unexpected pedal steel guitar parts on “Shattered” and other Some Girls songs, and the authentic American funk sounds he brought to the late-1970s Stones. In fact, prior to the Faces, Wood played bass in the Jeff Beck Group (in which Rod Stewart was the lead singer), and his funky/heavy blues-rock playing on that band’s version of “I Ain’t Superstitious” on the 1968 Truth LP was an early indication of his inventiveness. It is, in fact, the funk element that Wood brought in on his first session for Black and Blue. “Hey Negrita” was a funky riff with a reggae upstroke rhythm that he had been kicking around. “So all of us, independently and together, were into reggae, and it was also a mood of the time,” said Wood.7

Charlie Watts’ recollection about Wood confidently showing up with his own idea reveals the comfort level within the group and why he immediately fitted in.8 Watts had played in a band with Wood’s brother, Art, before the Stones. Ron Wood was more like family. When Rod Stewart left the Faces in 1975, the Stones hired Wood, though he did not become a permanent member of the band until 1976, and was not a full equal partner in the band until 1990.

Wood’s impact was felt immediately. While not on the level of Mick Taylor, he ripped out great solos, such as those heard on the 1975–76 Love You Live versions of “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” “Sympathy for the Devil,” and “You Gotta Move.” While Wood’s strident tone and style is not as distinctive as that of Taylor, whose parts were almost always immediately identifiable, his solos have often been deeply soulful, with an effortless-sounding fluidity that belied his ability. His parts generally fit in with the band’s overall sound. But his approach was not always at the expense of pyrotechnics, as the torrid ending of his solo on the live “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” demonstrates. But the most satisfying moments in Wood’s tenure have generally been the intertwining parts he played with Richards, picking up the “ancient form of weaving” that Richards and Jones had practiced. The two in each case made no clear distinction between “lead” and “rhythm” roles. If there is an analogy, the Stones of the Wood era are more like a dinner conversation in a big family, with people talking to, over, and around each other. As with those Chess records they cherished early on, it was more about the ensemble sound.

This is what we hear perfectly on Wood’s first start-to-finish album project with the Stones, Some Girls (1978). The Stones had weathered deaths, perilous financial straits, drug addictions, and arrests, including, with Richards, a charge of trafficking for the amount of heroin he tried to smuggle into Toronto while the band was rehearsing for a tour there. And while some critics had been writing them off since 1967, by 1977 the Stones did seem musically adrift and at times directionless. Whether or not listeners consider Sticky Fingers or Exile on Main Street to be the apex of the band’s catalog, most agree that the material started to fall off in quality thereafter. Many of us who came of age during the mid-1970s feel Goats Head Soup, It’s Only Rock ’n Roll, and Black and Blue to be fine, and even underrated records. And in hindsight, even some older fellow fans have warmed up to a number of those songs. It is clear that the group continued to push itself, mainly under the guidance of Jagger, to remain artistically and commercially relevant.

Jagger, rock and roll’s Peter Pan, was not about to go gracefully into that good night, or to accept middling reviews and sales for the band’s records while some young upstarts playing punk rock, which was just a garage variation of the sort of two-guitar, attitude-heavy, back-to-basics attack that the Stones made famous. “No Elvis, Beatles, or the Rolling Stones in 1977,” sang Joe Strummer of the Clash. While Strummer no doubt felt as let down by his boyhood heroes as anyone – watching rock and roll morph into heavy and self-important “rock” made by bloated, jet-setting junkies and coke fiends – the Clash, Sex Pistols, and others merely understood marketing and the importance of distinguishing your generation’s music from the previous one’s.

But no musician has understood branding and marketing better than Mick Jagger. He embraced many of the surface elements of mid-to-late 1970s punk and so-called new wave. More significantly, he thrived on the energy of the music, and of disco and funk, as he trolled the clubs of New York, London, and Paris. When the band was gathering for rehearsals outside of Paris for the Some Girls sessions, he strapped on a Strat, plugged into a loud Mesa Boogie amp, and joined Richards and Wood in a three-guitar front line and kicked out the jams on the 1978 album. The sustained excellence of Some Girls proved the band remained a major cultural force, and could still make an album with not even so much as an ounce of fat on its lean twelve inches of vinyl.

And while Jagger kicked them into gear, Wood was a significant contributing force of new energy to the group. He found the space between rock and roll’s finest rhythm section and its most identifiable rhythm guitarist, a trio of musicians who had developed their own sense of timing and groove-making over the course of fifteen years of constantly playing together. And Wood managed this while Jagger relentlessly pounded away on his own guitar throughout an album’s worth of material, for the first time in the band’s career. “Mick was bringing songs in and wanted to play the electric guitar,” said Chris Kimsey, the engineer and co-producer of Some Girls and a few subsequent albums. “His energy is very different than that of Keith or Ronnie in playing guitar. It is more, I suppose you could say punk rock. It’s just a very animalistic, basic way of bashing out the chord sequence … which kind of fits with his energy as a person, the way he moves and sings anyway.”9

Listening to the conversation between the guitars on Some Girls is a treat. While Jagger pumps up the adrenaline, Wood and Richards hang their loosely woven guitar parts around the tense core of the fast songs. But it is on the slower numbers, such as the ballad “Beast of Burden,” that a listener can really soak in the pleasure of interlocking guitar parts. Not coincidentally, it is one of the few without Jagger on guitar. There is plenty of space left and Wood and Richards use it well, rarely strumming a steady pattern. Instead, you hear the two listening to and answering each other, neither one anticipating their time to shine in a solo moment.

Versatility, and not virtuosity, has been the calling card of Wood. He had been used to playing with another great soul-influenced rhythm section in the Faces, Kenney Jones (one of rock and roll’s least-appreciated drummers) and Ronnie Lane. And here he is bringing that looseness of the Faces to the Stones – rather than resulting in redundancy, the Stones settled into its strength as a groove machine, which is how the band has remained for thirty-plus years.

Hired Guns: Key Contributors to Rolling Stones Recordings

While the changing three guitarists – all official members of the group – resulted in easily recognizable shifts in the sound of the decidedly guitar-driven band, each of the Stones’ hired keyboardists brought relatively less obvious, but nevertheless essential, personality and color to the group’s recordings and performances. Al Kooper brought a distinct and indispensable gospel flavor on piano and organ to his one-off contribution, “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.” And former Faces keyboardist, Ian McLagan, sat in with the Stones from Some Girls (1978) through their early-1980s touring. But for the purposes of this essay, we will concentrate on the four long-term contributors on piano and organ. As with Brian Jones, Mick Taylor, and Ron Wood, the band’s keyboardists correspond respectively with the Stones’ early, middle, and late periods. Ian Stewart was a constant presence in the band until his death in 1985, due to his role as a founding member of the group and his running of its stage management, touring details, and equipment inventory. But his playing is mostly associated with the Brian Jones early years. Nicky Hopkins entered the fray as the band transitioned through their brief flirtation with psychedelia and stayed right through the most classic recordings and tours of their golden era (1968–72). Billy Preston started working with the Stones on Goats Head Soup (1973) and continued through Black and Blue (1976). And Chuck Leavell joined them for the early 1980s and has remained with them since.

Piano Pounder One: Ian Stewart

As a founding member who was jettisoned from the band, Stewart is thought of as a main character in Stones lore, as well as a pianist. His death from a heart attack in 1985 was a stunning blow to the group. Stewart was a relatively clean-living regular bloke who eschewed drugs. His meat-and-potatoes lifestyle was reflected in his straightforward playing, informed by boogie-woogie jazz and its Johnnie Johnson/Jerry Lee Lewis rock and roll variations. Though closely linked to their early days, Stewart periodically played with the band on record and in concert until his death. He chose his spots, and there is no greater example of Stewart’s strengths and limitations than the 1969 recording session in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, at the tail end of the band’s American tour. The Stones were not yet touring with Hopkins, their regular session player at that point, and Stewart would sit in on live performances of “Honky Tonk Women” and the Chuck Berry covers “Little Queenie” and “Carol” (as heard on the 1969 live album from the tour, Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!). The three-day session in Alabama produced “Brown Sugar,” “Wild Horses,” and “You Gotta Move.”

Stewart begged off of “Wild Horses,” later explaining, “I don’t play minor chords,” which he also mocked as “Chinese chords.” “When I’m playing on stage with the Stones and a minor chord comes along, I lift me hands in protest.”10 Jim Dickinson, who became a legendary producer but was only at this session as a young fan, got to sit at the upright tack piano (a piano with tacks punched into the hammers to produce a honky-tonk sound) and contribute to the beautiful ballad. However, the famously bawdy “Brown Sugar,” a classic R&B-based number, was right up Stewart’s alley. He is heard entering on the choruses, helping to build the arrangement. Stewart pounds in with upper-register right-hand figures on the first chorus, adding a few boogie trills before ducking back out. He re-enters on the second chorus with a steadier pattern that plays off the rhythm guitars. After Bobby Keys’ overdubbed sax solo, the band slips back into the chorus again, with Stewart coming in playing a quarter-note on the same one or two keys, using the piano as a percussion instrument, sounding almost like a cowbell. As the band starts to vamp out with the repeated final chorus and “Yeah, yeah, yeah, woo!” parts, we can hear Stewart at his best, slowly adding ascending right-hand riffs and trills. When the vocals end and the sax and guitar lock into the repeated ending riff, Stewart plays off of the figure. It is the sort of part for which Stewart had been known since the Stones’ first gigs and recordings.

Listen, for example, to the band’s take on Chuck Berry’s “Around and Around,” which served as the lead-off track to the 12 × 5 US LP and Five by Five UK EP (both 1964). It is one of the clearest and dynamically loudest examples of Stewart on the early Stones sides, cutting through the middle frequency range taken up by Richards’ and Jones’ guitars by playing in the higher registers. It is clear he was a disciple of Berry’s pianist, Johnnie Johnson, both of them masters of rhythm, sliding in and over the guitars with a mix of percussive hammering and triplets, weaving in and out like tinsel garland around a Christmas tree.

Piano Pounder Two: Nicky Hopkins

In 1966, the Stones brought in Nicky Hopkins – they had known him since the early days of the London blues scene – to start playing the kind of material that was not Stewart’s forté. The band had already gravitated away from the straight R&B-based rock and roll they had been playing, broadening their palette with the Aftermath LP (1966). Jimmy Page, who was a well-known session musician before his Yardbirds stardom, recommended Hopkins to Brian Jones, who hired Hopkins for work on the soundtrack to the film A Degree of Murder (1967).11 Hopkins first appeared on a Stones album in a few of the tracks on Between the Buttons (1967). However, one of the most famous Stones piano-driven songs from that album, “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” was played by Richards and Jack Nitzsche, an LA-based arranger for Phil Spector who worked with the Stones on most of their mid-to-late 1960s records and played keyboards on a few tracks.

The boundaries of pop music were being stretched into experimental psychedelia, heavy rock, orchestral elements, English music hall traditions, satire, and more. Hopkins had already played with the Who, for example somehow managing to play a compelling piano part to cut through the raucous din of the 1965 single “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere.” And he would soon go on to be a member of the heavy blues Jeff Beck Group with Wood (and Rod Stewart), and San Francisco’s psychedelic Quicksilver Messenger Service. In that sense, Hopkins, who could roll with anything, was right for the Stones as they wandered off into the psychedelia of Their Satanic Majesties Request (1967). But, as with the Stones themselves, Hopkins’ main interest was American roots music like blues and country. So when the band got back to their roots, taking a step back and two steps forward with Beggars Banquet (1968), the first record of their golden period, Hopkins was their man. He plays on almost all of the tracks and Stewart is not on any, even though much of the material is blues based (there is also gospel, country, country-blues, and straight-up rock, all of the essential ingredients of the Stones sound). Piano plays a big part in the natural sound of the album, which contains one of Hopkins’ signature moments, “Sympathy for the Devil,” which is driven by his samba-like part and the highly percussive rhythm section. No guitar other than Richards’ solo remains on the finished recording.

The Sympathy for the Devil Godard film, which intersperses didactic staged pieces with filmed scenes of the Stones hard at work on the song at Olympic Studios, is extremely useful for fans. We get to see how the band worked, coming in with the germ of an idea and collaborating for hours (in this case, days) as they hashed out a final master recording. We also see the diligent Hopkins, head down in the corner of the studio, switching from organ to piano as the band ever so slowly starts to settle into the groove that culminated in the song. As Bill Wyman recounted:

All Stones stuff came from jamming in the studios. A riff or a few lyrics would be built on, sometimes for days and days, but you could always say “Ere Nicky, can you try something completely different, something much more off the wall” and he’d do it. He wasn’t bogged down in a particular way of playing like I might have been; if I couldn’t get some bass line idea out of my head then someone else, like Keith, would try, just to get a different feel, but Nicky could change totally from one style to another.12

In fact, in the film we see Wyman starting in his usual position on a stool with the bass guitar, trying along with the others to find the right arrangement. By the time Hopkins has switched to piano, Richards has taken over the bass, playing a far busier part than Wyman likely would have. As with other sidemen, Hopkins didn’t receive songwriting credit on Stones tracks, no matter how big a part he played. The song “We Love You” from Satanic Majesties, for example, was based on a riff that Hopkins had been working on for weeks, but like everything else, it is attributed to Jagger/Richards.

Relegating Stewart as a salaried employee and Hopkins as a freelance sideman (though the latter’s family maintains he was offered a full-time spot in the band) allowed the group more flexibility to vary their sound. After all, it would be difficult for a collective band to simply leave out one of its permanent members in order to hire an outside musician to play on a particular track. By contracting a side or session musician, a group can instantly add a dimension not being fulfilled by one of the main players. But with the unpredictability of the Stones’ schedule, coupled with a lack of songwriting royalties or even a place on the permanent payroll, Hopkins had to look in other places to help pay the bills, and he continued to get pulled into other sessions, including a steady spot with Quicksilver Messenger Service, as well as sessions for Jefferson Airplane and the Steve Miller Band. Hopkins’ work is all over the Stones’ next masterpiece, Let It Bleed (1969), but was absent for “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” and his piano/organ spot was occupied with aplomb by Al Kooper, who just happened to be in London for a vacation. Hopkins was also unavailable for the 1969 tour. But once Quicksilver broke up, Hopkins had more time to spare and, though he only plays on one song, “Sway,” on Sticky Fingers (1971) (which had a total of seven people playing keyboards), he was with the band on their 1971 tour and then joined them in France for the recording of much of Exile on Main Street (1972).

While many highlights of Hopkins’ tenure with the Stones can be heard on Beggars Banquet and Let It Bleed, it can be argued that his work on Exile on Main Street sets a high-water mark. Hopkins is back at the piano for most of the tracks. The first time we hear him enter is on the first pre-chorus of the lead-off track, “Rocks Off,” and right away we can tell why he is held in such great esteem. He almost builds the arrangement himself, varying each section to distinguish it from the others, not only the verse from the chorus, but each verse from the other verses, and each chorus contains its own exuberant pattern and ad-libs.

It is the sort of rock and roll number that Stewart would have generally also handled. But now Hopkins was around the Stones full time – literally, in this case, living with them on the French Riviera as they recorded in Richards’ rented basement. Stewart was in charge of the Rolling Stones Mobile Unit, a truck fitted out with a recording studio control room, and by all accounts, challenging to keep powered up and running. Given that his responsibilities included keeping the band’s equipment and instruments functioning in the extremely humid basement of the villa, Stewart was likely too busy to sit in often on piano, especially when they had Hopkins there all the time. Stewart does, however, play on three central tracks: “Shake Your Hips,” “Sweet Virginia,” and “Stop Breaking Down.” But if “Rocks Off” was right in Hopkins’ wheelhouse, then “Rip This Joint” could have been tailor-made for Stewart. Yet the barrelhouse boogie-woogie we hear on that track is Hopkins again. He tears up the track with nimble fingerwork. The torrid tempo is the fastest of any Rolling Stones track and the wall-to-wall part that Hopkins plays seems to accelerate the breathless speed of the recording.

The intensity and heat gets turned up later on during the album, on another highlight, “Ventilator Blues.” Somehow, Hopkins finds a counter-rhythm to play off the stop-and-start groove of the slide guitar and drums. “Bobby Keys wrote the rhythm part, which is the clever part of the song,” said Charlie Watts. “Bobby said, ‘Why don’t you do this?’ and I said, ‘I can’t play that,’ so Bobby stood next to me clapping the thing and I just followed his timing.”13 Hopkins keeps it funky and restrained until he lets loose at the end, peppering it with Otis Spann-inspired sprays of high notes. Spann, a member of Muddy Waters’ band, is a sensible reference point, as the menacing, claustrophobic atmosphere of the song itself was ripped from the Waters playbook.14

While Hopkins could keep pace with the most intense, the loudest, and the fastest of them, his most rewarding work tended toward the elegiac and pastoral. For pure piano goodness, one need not look any further than the creamy opening chords of Exile’s “Loving Cup.” The entire first verse is backed only by Hopkins’ piano and Richards’ acoustic guitar. While Jagger and Richards pop in with a two-part harmony to open the song, the piano remains high in the mix. In fact, the vocals are low relative to how most of us are accustomed to hearing popular music. The effect, as with all of Exile, is exhilaration as the vocals strain to be heard. Hopkins was also strongly influenced by Floyd Cramer, a Nashville legend who played his slip-note riffs (playing a chord where one quickly slides or hammers the “wrong” note into the “correct” note for a bending feel) on records in the 1950s and 1960s by everyone from Elvis Presley and the Everly Brothers to Patsy Cline and Don Gibson. Cramer’s honky-tonk fingerprints can be heard on the parts Hopkins adds to the countrified “Torn and Frayed” and even on the gospel-informed “Let It Loose.”

What makes the latter such an original Stones song, as opposed to a straight gospel homage, are the twists that the band bring to it. Instead of, say, a Hammond B-3 organ opening the song as in a traditional gospel number, Richards begins with a guitar amplified via a revolving Leslie organ speaker to achieve a sound similar to that of an organ. When Hopkins enters introducing the second verse, it is not what one would immediately associate with gospel piano playing. Instead, his is a country part, which he starts to mix together with some gospel riffs and chord suspensions. The song is exemplary of the instincts Hopkins had for slipping in and out of an arrangement and for the laid-back feel for the beat that he possessed. Listen, for example, how he drops out for the vocal breakdown at about the 2:00 mark. He enters after the third line, like wisteria weaving around a trellis, dipping behind the music and then coming out to blossom at the right spot.

Piano Pounder Three: Billy Preston

– and Bobby Keys, Jim Price, and Merry Clayton

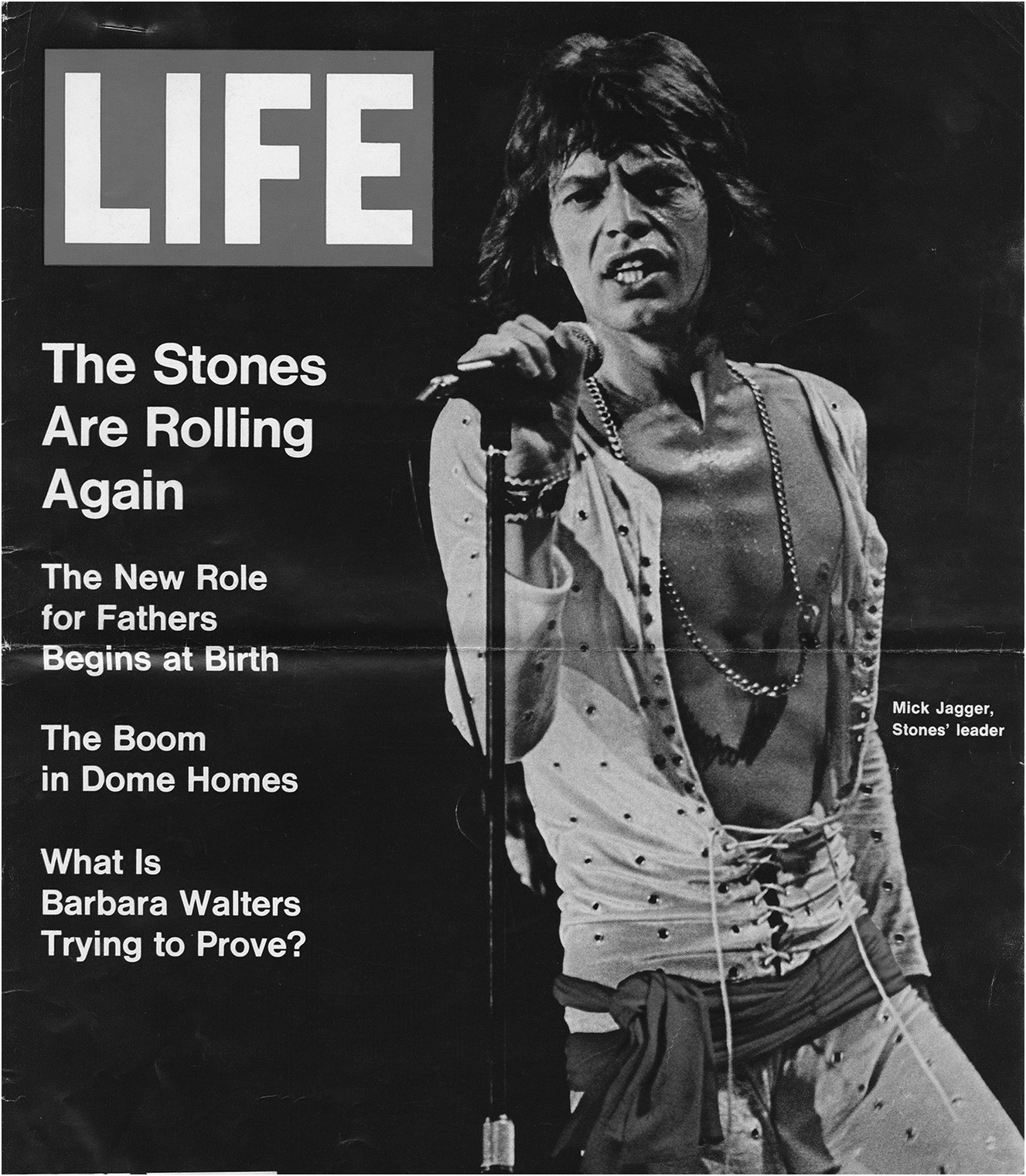

While Hopkins was conversant in gospel piano, Billy Preston was the real deal (see Figure 2.1). He played organ with Mahalia Jackson and James Cleveland, gospel royalty, at the tender age of ten. From there, he hooked up with Little Richard’s band, eventually touring England, and meeting the Beatles in the process. Preston went on to play with Ray Charles and returned to England in 1968–69 to sit in with the Beatles on Let It Be (1970). The Beatles also signed Preston as a solo artist to their Apple label. He nurtured his successful solo career concurrent with making stellar guest appearances with other artists, such as Aretha Franklin, Bob Dylan, Delaney and Bonnie, and, of course, the Rolling Stones, as is discussed later in this chapter.

Figure 2.1 Mick Jagger with Billy Preston, Plaza Monumental, Barcelona, 1976.

Bobby Keys (saxophone) and Jim Price (trumpet) had also played in the Delaney and Bonnie & Friends band and came over to the UK at the request of George Harrison to work on his masterpiece, All Things Must Pass (1970). Keys met Jagger while in London and soon he and Price became the horn section for the Stones. Starting with the appearance of Keys on “Live With Me” (from Let It Bleed) in 1969, the horns added an indelible dimension to Sticky Fingers (1971) and Exile on Main Street (1972), as well as the tours supporting those records. The interaction between all of these musicians on the records and tours of Harrison, Joe Cocker, Eric Clapton, and the Stones was indicative of an overall back to roots movement heard in the immediate post-psychedelia late 1960s on such records as the Band’s Music from Big Pink (1968), Dylan’s John Wesley Harding (1967), the Stones’ Beggars Banquet (1968), and the Beatles’ White Album (1968). But with added horn sections and backing singers, some rock shows were resembling the soul revue-type ensembles of Ike & Tina Turner, Stax, and Motown. Jim Price eventually left the fold, becoming a producer, but Keys remained a loyal sideman to the Stones for decades, falling out for a few years due to drug abuse, but back in the fold from the 1980s to his death in 2014. His brassy sax solos are inextricable from such songs as “Live With Me,” “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking,” and “Sweet Virginia,” and, of course, there is his signature solo in “Brown Sugar.”

The Stones had famously covered songs by soul artists such as Otis Redding, Don Covay, Sam Cooke, Marvin Gaye, and Solomon Burke, just to name a significant few. These influences crept back as the Stones entered the seventies. “Through that whole period, there wasn’t a whole lot going on in terms of saxophones and horns,” Keys told me, discussing the time period surrounding the Summer of Love. “Except for the soul thing: Stax, Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, and that whole bunch from Memphis. I really loved that stuff. But up until then, most bands were guitar oriented, except for a few. We were hearing some of the first Stax stuff up at Leon Russell’s house. Steve Cropper and Duck Dunn had come from Memphis to Los Angeles to do some overdubs. So I heard some of that stuff before it came out. And I was thinking this is definitely the wave of the future. It has all of these wonderful horns in it. So hell, I guess I am in good shape here.”15

The brassy element of this period is essential to the gospel-soul sound of the early-1970s Rolling Stones. Indeed, it seems that Jagger was influenced to write such songs as the Otis Redding-inspired “I Got the Blues” by his time spent enjoying Redding and other Stax records with Keys in the early days of their budding friendship, and, of course, the group had covered some of Redding’s songs on their early albums. There was an overall revival of the African-American influence – specifically gospel and its secularized offspring, soul – on rock and roll. I suggested to Keys that the horns were inspiring the Stones’ songwriting itself, with songs such as “Let It Loose” and “Shine a Light.” “Right, and Billy Preston brought a lot of that influence too,” he said.

Preston’s first appearance on a Stones record was on “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking,” followed by a searing, emotional Hammond organ solo on “I Got the Blues,” both from Sticky Fingers. As great as Hopkins, Stewart, Nitzsche, and the Stones themselves were at adding piano and organ, it is hard to imagine any of them ripping out something as authentically gospel as this concise solo. Preston only makes one appearance on Exile on Main Street, on “Shine a Light,” but it is another soul-stirring performance on both piano and organ, adding percussive and sweeping fills on each instrument during the transitions for verse to chorus. The difference in the individual styles that Preston and Hopkins brought to the Stones is obvious. Preston was also the organizing force behind the backing vocalists and the arrangements for vocal ensemble.

The Stones started adding extra voices to their records in earnest with “Salt of the Earth” from Beggars Banquet, specifically with a gospel feel in mind. Despite the addition of the Los Angeles-based Watts Street Gospel Choir, it does not come off as a gospel number, per se. But one can see the beginnings of the genre’s influence on the Stones, so that for the next album, Let It Bleed, the band took another swing and ended up with the epic “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” a song that begins as a folk-rock song but quickly becomes so full-on gospel that the group apparently felt it would be advantageous to undercut it with some irony. Instead of having the typical African-American Baptist choir, the Stones brought in the London Bach Choir:

“I’d … had this idea of having a choir, probably a gospel choir, on the track,” said Jagger, “but there wasn’t one around at that point. Jack Nitzsche, or somebody, said that we could get the London Bach Choir and we said, that will be a laugh.”16 [Richards explains the use of the choir]: “Let’s put on a straight chorus. In other words, let’s try to reach the people up there as well. It was a dare, kind of … And then, what if we got one of the best choirs in England, all these white, lovely singers, and do it that way? … It was a beautiful juxtaposition.”17

Also on Let It Bleed is the legendary star vocal turn from Merry Clayton, who gives a spine-chilling solo performance on “Gimme Shelter” – the first from a non-Rolling Stone on one of their recordings. Having written about this in detail elsewhere, suffice it to say her high-register attack, during which her voice buckles and then cracks as she soulfully pushes it even harder, is one of rock music’s greatest moments.18 It added a brand-new texture into a band which had been around for six years. On the scale of contender for greatest rock song of all time, the energy injected by Clayton’s performance tipped “Gimme Shelter” from competitor to grand champion.

As the Stones increasingly brought outside contributors to their recording sessions, they also grew more comfortable with expanding their core band into a touring ensemble that continues to characterize their live performances today, augmented by regular sidemen and women, and sharing the spotlight with guest stars. In addition to his appearances on Sticky Fingers and Exile, Preston was the mainstay keyboardist on the three albums that followed – Goats Head Soup, It’s Only Rock ’n Roll, and Black and Blue – and attendant mid-1970s tours. In fact, he was more than a mere sideman, sometimes sharing the microphone with Jagger on prominent vocal parts, and even a few turns singing one or two of his own songs.

Preston was still with the Stones in 1977, when they played the small Toronto El Mocambo Club (some of this gig is heard on Love You Live [1977]), and it was apparently there that he demonstrated the four-on-the-floor beat that formed the backbone of disco music.19 So while he is not present on the Stones’ next LP, Some Girls (1978), his influence carried through in Watts’ playing on the song “Miss You,” a smash single for the band at a crucial point.

Piano Pounder Four: Chuck Leavell