“We must get rid of this bank by any means,” declared Shaykh Sulayman al-Taji al-Faruqi, a prominent Arab Palestinian landowner and politician, in an ill-tempered letter to his lawyers in November 1939. Not mincing his words, al-Faruqi reiterated that he wished to “put an end to this bank, which I see that its presence is of no value as its nonpresence . . . this bank that has spent £P140,000 and has nothing now but revenge.”Footnote 1

The Arab Agricultural Bank, the target of al-Faruqi's ire, was the first Arab-owned institution in Palestine to provide credit to Arab farmers. Al-Faruqi was among its earliest customers. It had been launched in 1933 to much commendation from the local Arabic press by a pioneering Arab Palestinian businessman, ʿAbd al-Hamid Shuman, who had earlier founded the only other Arab bank in the country, the Arab Bank.Footnote 2 Shuman had trumpeted the new bank's nationalist credentials, declaring it the only Arab institution to provide low-interest credit to the impoverished Arab farmers who were by then rapidly losing ground, literally and figuratively, to Zionist immigrants.Footnote 3

Shuman's declaration had come at a moment of churning Arab anger about uncontrolled Zionist immigration and land purchases in Palestine, and, lately, the dispossession and eviction of hundreds of tenant farmers from their lands.Footnote 4 The professed aim of the bank—“to help the Arab peasant preserve the ownership of land in Palestine”—thus offered a salve to one of the thorniest problems of the time, no trifling ambition.Footnote 5

But al-Faruqi was unimpressed. He disdained the bank's credentials, writing to his lawyers that: “The Agricultural Bank means nothing. In its coffers there is no more than 10% in cash from the capital . . . . Most of the capital is consumed by unattainable debts to (the manager's) friends . . . [who] owed the Bank tens of thousands.”Footnote 6

Al-Faruqi's rancor had been provoked not by the bank's failing financial health but by its repeated attempts to induce him to repay the large debt he had owed it since 1936. The banks had, in the summer of 1937, threatened legal action if he did not pay up. In May 1938, after several attempts to collect his overdue loan, the Agricultural Bank sued him for £P2,000, the full amount owed, plus accrued interest. Shortly thereafter, the Arab Bank launched its own suit against al-Faruqi, which, at £P6,392, was triple the Agricultural Bank's claim.

Rather than respond to this legal onslaught by paying what he owed, al-Faruqi hired a Jewish law firm run by an eminent Zionist to mount a spirited defense against the claims of both banks. When this failed he appealed to the Supreme Court, pleading his inability to pay, pointing to his desperate financial situation, protesting “the revengeful spirit” of the banks, and begging the consideration of “British justice.”Footnote 7

The proceedings dragged on for years, generating tremendous animosity between the banks, which doggedly pursued repayment, and their customer, who adamantly refused to pay. Al-Faruqi was convinced that both banks had a particular animus against him, but the fragmentary records of the Palestinian district courts indicate that these were just two of several contemporaneous suits that the banks launched in the late 1930s against their defaulting debtors. Although the scarcity of data makes it difficult to devise a comprehensive list, al-Faruqi was in good company, for the banks sued many other luminaries of the Palestinian social and political elite: landowners like ʿAbd al-Fatah Nusayba, Fakhr al-din Nusayba, and the heirs of Tawfiq al-Ghusayn; businessmen like ʿAli and Nabil al-Mustaqim, who owned the Cinema Nabil in Jaffa; and various members of Palestine's most prominent family, the al-Husaynis (see Table 1).Footnote 8

Table 1. Partial List of Lawsuits, Arab and Agricultural Banks v. Customers, 1930s and 1940s

Source: Israel State Archives, Various. All names spelled as they appear in the original legal documents.

Little is known of these cases. The archival records are incomplete even for al-Faruqi's files, which are the best documented of the lot. The details recounted here are pieced together from the “Bernard Joseph and Company” papers of the Israel State Archives, which are categorized in Hebrew and accessible, if at all, only to those who read that language. The few court documents are poorly preserved. But we are fortunate to have them, for the records of the many Arab law firms operating during the Mandate, particularly those that were based in Jaffa and Jerusalem—such as those run by ʿAziz and Fuʾad Shahada, Subhi ʿAyyubi, Abkariyus Bey, Hanna ʿAtallah, and the other lawyers of the day—are lost, as are the papers of so many businesses, accounting firms, hotels, tour companies, and citrus trading firms comprising the Arab business sector during the Mandate.Footnote 9 One of the obvious difficulties of researching Palestinian business and financial history is the disappearance of these archives, which would have provided a rich source of material for the kind of history presented here.Footnote 10 Had al-Faruqi not hired a Jewish firm to represent him in his battles against the banks, this story would have been lost to us too.

Nevertheless, taking seriously historian Sherene Seikaly's call to not abandon the business history of Palestine—or assume there is none—because of this “archival absence,” this article uses the evidence available to examine why these battles between the banks and their customers were so acrimonious; what was at stake; and how this story of indebtedness, bankruptcy, and dispossession underscores and sheds new light on the bitter realities of financial life for Arab Palestinians during the Mandate.Footnote 11

Bank Versus Land

Most economic histories of Palestine during the Mandate have focused on land, which is rightly thought to be at the heart of the conflict between the Jews and the Arabs. An enduring preoccupation is the “vexed question” of why Arabs sold their lands to Jews at a time when doing so was tantamount to betraying the national cause.Footnote 12 Some have sought answers in the motivations of Arab land sellers, painting a broad-brushed picture of a desperate peasantry bedeviled by poverty and indebtedness, a self-serving, profit-seeking landowning elite, and a distracted and divided political leadership. Others have looked at British colonial or Zionist policies. Most have ignored the role played by private Arab financial institutions in muddying the waters on both fronts, land and debt. Few have explored how these institutions survived, operating in the shadows of larger and better-funded foreign and Zionist institutions while surmounting restrictive Mandate regulations and an economy that lurched from crisis to crisis; none have analyzed what they had to do to succeed.

This article traces the earliest years of the first two independent private Arab banks in Palestine, the Arab Bank and the Arab Agricultural Bank, and uses the realm of banking to further a more complex understanding of Arab Palestinian landlessness and indebtedness during the 1930s. An analysis of the legal battles between these pioneering banks and their customers reveals how the nationalist goal of building viable Palestinian financial institutions clashed with the other nationalist goal of preventing Arab lands from being sold to Zionist buyers. It exposes the conflicting positions into which Palestinians of similar politics were forced by the political and economic exigencies of the time. It further argues that these differences cannot be explained by reductive notions of collaboration or factionalism, but instead resulted from the difficult choices necessary to survive in a system defined by the absence of sovereignty.

Shuman, a self-made entrepreneur who founded both banks, was convinced, perhaps because his social status originated not from inherited land but earned wealth, that the establishment of viable financial institutions was the only way to prevent the Palestinian nation from being destroyed by Zionism. This conviction led him, when his banks were, in al-Faruqi's words, “in a bad fix,” to sacrifice the interests of his debtors (suing them if they defaulted on loans) to the larger goal of ensuring the banks’ survival.Footnote 13

Debtors like al-Faruqi, for their part, were convinced, perhaps because they were members of the landowning elite, that preserving ownership of the lands with which they had secured their loans was far more critical to the anti-Zionist nationalist struggle than any question of the banks’ success. They wished to “get rid of the bank(s)” if that would allow them to default on their loans, which in turn would prevent them from being forced to sell their lands to Zionists, who constituted, at the time, the group in Palestine with the readiest means to purchase them.Footnote 14

And so Shuman and al-Faruqi, who were both anti-colonial, anti-Zionist nationalists, were locked in a struggle in which each was motivated not only by the ordinary impulses of survival but also by the conviction that defeat would entail the loss of a significant national asset— in al-Faruqi's case, land, and in Shuman's, the banks—and thus the national cause.Footnote 15

A related contribution of this piece is to complicate the notion that the competing priorities of Palestinian elites can easily be divided into collaboration or resistance frameworks. Some scholars have argued that wealthy Arabs sold their lands to Zionists for economic gain or convenience, caring little for the fate of the tenant farmers who had lived and worked on their lands for generations.Footnote 16 As these sales were sometimes executed through middlemen to obscure the identities of the actual sellers, an uncharitable implication was that these sellers were less committed, in private, to the nationalist cause than they claimed in public; a variation posits that some even used indebtedness as a ruse to disguise their sales as court-ordered auctions.Footnote 17 These analyses divide Arabs into those who “collaborated” by selling their lands or working, in other ways, with Zionists, and those who “resisted” by taking up arms.Footnote 18 But this article will suggest that the actions of landowners like al-Faruqi, even if they did sell their lands to Zionists, cannot be dismissed outright as collaboration.

It challenges, too, the idea that the rivalry between two prominent families, the al-Husaynis and al-Nashashibis, who disagreed on attitudes toward British rule and tactics for protest, explains the failure of Palestinian politics to mount a defense against Zionism. Although some scholars have made much of these factional allegiances, they do not explain the clash between Shuman and al-Faruqi. Shuman courted customers from both factions, whereas al-Faruqi and the Agricultural Bank's chairman, Ahmad Hilmi ʿAbd al-Baqi, were both pillars of the anti–al-Husayni opposition (al-mu‘āraḍa) during the 1930s and early 1940s; all three were on cordial terms which curdled into contempt only when the banks sued for repayment of their loans.Footnote 19

Instead, this article argues that the Palestinian tragedy of the 1930s and 1940s encapsulated in miniature in this mutually destructive struggle between the banks and their customers had less to do with collaboration or factionalism than with two interconnected political constraints. The first was the fact that Palestine was a British Mandate, which rendered it, essentially, a second-class colony encumbered with a government whose profit-and-security-maximizing priorities did not include provisions for protecting almost-bankrupt Arab banks, or bankrupt elites, or policies for helping the local economy recover from crises. The banks, when facing insolvency, had, unlike Jewish banks, no recourse to a larger bank that could act as a lender of last resort, nor to governmental bail-out or loan consolidation programs, and were left to thrive or perish as circumstances allowed. Nor were their once-wealthy customers able to avail of bankruptcy protections from the government when they fell on hard times, as Mandate officials focused their energies on the peasantry, whose indebtedness and poverty were thought to pose a greater threat to overall stability.

The second constraint was posed by the particular character of Zionism, with its urgent imperatives to settle the land and to create a thriving, self-sufficient Jewish economy. Persecution in Europe in the late 1920s and early 1930s led to ever greater numbers of Jewish refugees, some bringing with them enormous capital and donations to Jewish funds. This contributed to the once-and-for-all nature of Jewish land purchases in this period, which ensured that land, once bought, was never again resold to an Arab.Footnote 20 Private Zionist land purchasers and banks were supported by deep-pocketed international Zionist institutions and sympathetic Mandate authorities and were thus able to weather the successive local and global economic shocks that hit the Palestinian economy in the 1930s, which decimated their smaller, unprotected Arab competitors.

The inconsistent course of action that Shuman pursued—first, to grant loans to his compatriots in the name of the nationalist struggle; then to sue those compatriots in the service of the same struggle; to simultaneously litigate against a Zionist fund, once again as part of his claim to being at the forefront of the struggle—also illustrates the difficult choices facing many native nationalist entrepreneurs if they wished to succeed in a colonial context. The larger question implicit in this, about whether there can be any sustainable economic development and any lasting development of indigenous institutions, particularly of financial institutions, without political sovereignty, has preoccupied many studies of economic development under colonialism, and remains of immediate relevance to anyone interested in Palestine/Israel today, when conversations about peace and development in the region are often conducted without any acknowledgment of the lack of sovereignty of the Palestinian people.Footnote 21

This article weaves together the institutional and personal narratives of the banks and their customers. It begins with a description of the establishment of the Arab Bank and the Arab Agricultural Bank by ‘Abd al-Hamid Shuman in the early 1930s and situates these institutions within the overall economic environment of Palestine under British rule up to and during the 1936–1939 revolt. It then turns to the details of the dispute between Shaykh Sulayman al-Taji al-Faruqi and the Arab and Agricultural Banks. This story of the legal battles between the banks and their customer illustrates how conflicting notions of nationalism led to irreconcilable tensions between land-ownership and institution-building, which shaped Arab Palestinian economic life under the Mandate.

1. The Palestinian economy in the 1920s

ʿAbd al-Hamid Shuman liked to present himself as a self-made man.Footnote 22 This was no exaggeration: the illiterate younger son of a stone mason from the village of Bayt Hanina, near Jerusalem, he had emigrated to the United States in 1908, like many Arabs from the Syrian provinces in the late Ottoman era, to seek his fortune. Beginning in New York as an itinerant peddler who had no money, spoke no English, barely wrote Arabic, and knew nothing of business, he became, within a few years, a prosperous businessman with a string of “Shoman's” stores in New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia.Footnote 23

During his time abroad, Shuman, both inspired and frightened by stories he heard of successful Zionist financial institutions in Palestine, dreamed of creating a bank for his own people. He raised the matter incessantly with fellow Arabs in New York, trying to raise capital and interest in his project, but was ridiculed for his grandiose ambitions.Footnote 24 He bided his time, expanding his retail business and amassing capital for twenty years, before deciding, in 1929, to sail back to Palestine. The homeland he had left an Ottoman province was now a British Mandate with new borders and new tensions arising from Britain's support of the Zionist project.

Shuman was one of several prosperous businessmen who returned to Palestine from the Americas in the early years of the Mandate, brimming with confidence for their prospects and “dreaming,” as one historian put it, of “exploiting their wealth in the homeland and turning it into power and glory.”Footnote 25 These included the founders of various companies—the Al-Bireh, the Deir Dibwan, the Palestine—whose stories are left out of most accounts of Arab economic development in this period, which tend to echo British and Zionist views that it was capital brought by Zionists from abroad and income generated from Arab land sales to Jews that engineered the development of the local economy during the interwar years.Footnote 26

Returning émigrés were not the only ones gripped by a sense of possibility in the early years of the Mandate. A group of homegrown intellectuals founded a journal “dedicated to the management of economic life,” which declared that the end of the war “marked a transition from an economy of scarcity to an economy of plenty.”Footnote 27 These “men of capital,” to adopt Sherene Seikaly's apt phrasing, were convinced that their country was on the cusp of an “economic awakening” that would lead to a “capitalist utopia.” Their sense of awakening was not just rhetorical: a Mandate-era surveyor reported that 1,373 “new Arab enterprises” were established in Palestine between 1918 and 1927, representing 60.5 percent of all new manufacturing activity in the country.Footnote 28 Another source estimated that Arab capital investment between 1920 and 1935 reached £P2,000,000.Footnote 29 The trade catalogs and Arab Chamber of Commerce directories of the era, punctuated as they are with advertisements for soap factories, flour mills, hotels, importers and exporters of timber, cement, textiles, and tobacco, all testify to the entrepreneurial spirit of the time.Footnote 30

But the heady optimism of these entrepreneurs stood in stark contrast to the economic reality faced by the majority of their compatriots, particularly the peasantry, which had been mired in widening circles of poverty and indebtedness since the late 19th century.Footnote 31 British policies promulgated during the first decade of the Mandate (a new, regressive, direct tax system; fiscal policies that favored Jewish industrial investment; and the lack of cheap credit) exacerbated their financial woes.Footnote 32As Zionist immigration and capital flows accelerated in the late 1920s in response to growing anti-Semitism in Europe, land prices and rents soared, giving the impression of a thriving economy.Footnote 33 But the agricultural sector that dominated the Arab economy and determined its net productivity remained stagnant, with prices for basic agricultural crops plummeting.Footnote 34 Shuman himself noted, shortly after his arrival from New York, that “economic life in Palestine, belied by its superficial prosperity, was dangerously imbalanced.”Footnote 35

This “dangerous imbalance” also marked the local banking sector. In 1929, when the simmering anger felt by Arabs at their situation boiled over into violent protests, the Egyptian financier Talʿat Harb, the founder of the Bank Misr and would-be investor in Shuman's proposed bank, pulled out of the project, fearing “Palestine was about to become the scene of bloody disturbances in which a banking project is bound to fail.”Footnote 36 But that same year, the local managers of Barclays and the Ottoman Bank, then the two largest foreign banks in Palestine, competed vigorously to “corner the Arab market,” making “special efforts to attract Arab clients” by “offering better terms.”Footnote 37 In July 1929, just a month before the riots, the Ottoman Bank's branch manager complained that Barclays had stolen “our best clients in Nablus whom we are loath to part with.”Footnote 38

Similarly, in 1933, as a fresh round of protests spread through the country, a British colonel wrote to the British Treasury urging approval for a new “Pan-Arab bank” created by himself and his Arab partner, a Mr. Naufal.Footnote 39 His letters, untainted by the malaise that afflicted most Arab Palestinians and full of anticipation for the “large unexploited Arab appetite for banking,” and the “several millions of pounds hoarded that could be deposited in our bank,” suggest the kind of future Shuman hoped for his own institution.”Footnote 40

But Shuman was aware of the ways in which the economic boom caused by Zionist settlement patterns, cash flows, and land purchases obfuscated the realities on the ground for his compatriots. He lamented the “economic structure [that] furthered Zionist and British colonial goals while ignoring the needs of the native population.”Footnote 41 Convinced that a national bank, run “for and by Arabs,” was the best way to redress these “dangerous imbalances” and to “serve the highest national interest,” he set about putting into motion the plan he had been formulating for two decades.Footnote 42 It was not, however, easily done.

2. Growing Pains

From the start Shuman's project ran into obstacles placed by the British authorities who governed Palestine with little understanding of or sympathy for the needs of Arab entrepreneurs. The first obstacle came before the bank was founded, when, in the wake of the 1929 protests, the British, obsessed with calming the restive and indebted peasantry, passed a series of banking ordinances to “protect the public . . . from native banks [that] are nothing but groups of money-lenders cloaking themselves under the title of bank.”Footnote 43 These included the Companies Ordinance (1929) “establishing new minimum capital requirements for all companies registered under Palestine law”; the Usurious Loans Ordinance (1934), setting the highest legal rate of interest at 9 percent “to break the power of the money-lenders”; and, later, the Banking (Amendment) Ordinance (1936), “stemming the further proliferation of small banks all over the country.”Footnote 44 Indicating the spirit in which these were promulgated, one Mandate official remarked dismissively that “every grocer in Palestine can become a banker.”Footnote 45

Shuman, in the view of British officials one such “grocer,” had to endure months of tedious exchanges with Mandate bureaucrats to secure the permission needed, under the new ordinances, to register his bank. His first application was rejected because it did not meet the new minimum capital requirements.Footnote 46 When he raised additional capital he was refused again, this time because the bank's mission “to buy, sell and mortgage land in addition to pursuing regular banking activities” was “contrary to the proper functioning of a bank.”Footnote 47 As the Anglo-Palestine bank, the largest Zionist bank, openly conducted land transactions without any governmental objection, this permanently soured Shuman's views of British motives in Palestine.

Shuman managed to maneuver around these regulatory obstacles with the help of a well-placed friend, Musa al-ʿAlami, who worked at the Companies Registrar.Footnote 48 The Arab Bank, the first Arab-owned and Arab-funded bank in Palestine, was thus established on 14 July 1930 with a total share capital of £P105,000.Footnote 49 Its subsidiary, the Agricultural Bank, was established in 1933 with a more modest capital of £P80,000. These achievements did not, however, ease Shuman's conviction that the British were inherently prejudiced against Arab entrepreneurs.

FIGURE 1. The first branch of the Arab Bank outside Jaffa Gate (Bab al-Khalil), Jerusalem, 1930. Photo courtesy Arthur Hagopian and Apo Documentaries, armenian-jerusalem.org.

A second obstacle was posed by the government's open favoring of Barclays Bank, which received subsidies and tax incentives to open branches in towns where the Arab banks already operated. A telling incident occurred in July 1935, when the district commissioner prevented Hebron's municipal council from transferring its accounts from the (Zionist) Anglo-Palestine Bank to the Arab Bank, on the grounds that a new Barclays branch was scheduled to open there soon.Footnote 50 As even a British official noted, “the director of the Arab Bank has as a consequence formed the opinion that the Government is hostile to their institution.”Footnote 51 Meanwhile, the frankly self-serving enthusiasm of Barclays for the new banking ordinances—one branch manager writing, in private, to the Mandate authorities that “the public should be prevented from being misled when they see the word ‘bank’ written in large letters on the front of some imposing building”—did not help.Footnote 52

A third obstacle was the creation of a new British-sponsored Agricultural Mortgage Bank in 1935. This was the pet project of the Mandate's treasurer, William Johnson, who cajoled the major international banks and insurance firms in Palestine to contribute to the bank's seed capital.Footnote 53 The government itself provided a hefty advance of £P150,000 for the bank's guarantee fund so that the participating entities would not have to assume any of the risk of the loans granted by the bank.Footnote 54 Shuman viewed this venture as a direct threat to his Agricultural Bank, which was still struggling to find its feet. He feared that the British-sponsored rival would poach his customers because its government-backed guarantee and larger endowment enabled it to offer better rates on loans: 5 percent to his 9 percent.Footnote 55 That the Anglo-Palestine Bank and Barclays were key partners in the venture deepened Shuman's antipathy.Footnote 56

But the clearest instance of the government's refusal to support Shuman's banks came later in 1935, during a brief but serious financial crisis in Palestine caused by the outbreak of the Italian-Abyssinian war. As the panicking public, fearing a blockade of all Mediterranean-routed trade, rushed to withdraw its deposits, the small local banks struggled to stay solvent.Footnote 57 The Anglo-Palestine Bank collaborated with the government and Barclays to offer emergency loans to Jewish banks in trouble during the “bank run.”Footnote 58 But there was no such aid offered to the two Arab banks, which Mandate officials and Barclays deemed “too profligate and risky” to save.Footnote 59 The banks were thus forced to weather the crisis, as the Arab Bank's 1935 annual report acidly noted, “without recourse to any loan or other aid which the Mandatory Government offered Jewish banks to survive the panic.”Footnote 60

The banks’ teething problems were exacerbated by the difficult economic realities of the early 1930s. The Arab Bank's early annual statements describe these in muted apolitical language, referring in passing only to a “downturn in the agricultural sector.”Footnote 61 But in fact the agriculture-dominated sector was, by 1934, in a deep crisis brought on by an invidious combination of natural and political factors: a precipitous drop in cereal prices, particularly of wheat and barley, caused by the onset of the global depression in 1930; a further drop in prices due to successive seasons of bad harvests caused by poor rains between 1931 and 1934; regressive British tax policies and damaging tariff barriers; and, finally, accelerating Zionist immigration and land purchases, which led to soaring land prices and rents at exactly the moment when the peasantry, reeling between falling incomes and rising costs, plunged into ever-deepening traps of poverty and debt.Footnote 62

Although distracted by his struggles with the Mandate bureaucracy, Shuman was not impervious to the suffering around him. He had launched the Agricultural Bank precisely to provide relief to the peasantry via low-interest credit. The local Arabic press acknowledged the “urgent need it met”; two contemporary Arab economists deemed it “the most important bank for providing short-term loans to Arab cultivators”; and the Arab Chamber of Commerce's directory hoped “its capital [could be] increased to further benefit cultivators and fellahin.”Footnote 63

But despite the public enthusiasm for his project, Shuman's ambitions had hardened and narrowed in the absence of institutional support for his banks during the 1935 financial crisis. His primary goal became the bank's survival. Thus, although the Agricultural Bank spoke publicly of providing credit to impoverished peasants, in reality it sought, like its rival the (British) Agricultural Mortgage Bank—and, in fact, like banks everywhere—creditworthy customers who would repay their loans on time.Footnote 64 Where a critical reading might impute coldly capitalist profit seeking or, worse, hypocrisy in this, Shuman himself saw no contradiction. He viewed himself a nation-builder and his banks’ success as an “urgent part of protecting the homeland.”Footnote 65

Unlike some Arab Palestinian businessmen who, as Seikaly has argued, “severed the political from the economic,” and used “a flexible nationalism to protect their interests,” Shuman did not waver from his critique of British colonialism and Zionism, even when doing so might have brought bridging loans from larger banks such as Barclays and the Anglo-Palestine during those difficult early years.Footnote 66 Nor did he waver from his conviction that the political goal of an independent nation was indistinguishable from the economic goal of a successful national bank. His credo was simple: “We must gather strength by creating our own national institutions, our best buttress against the power of Zionism, the Mandate, and colonialism. Instead of hoping to injure foreign banks by hiding our money at home . . . we must compete.”Footnote 67

3. Citrus

Shuman's quest for a “solid foundation on which an economy may be built” led him to the local citrus industry, which had flourished since the late 19th century and continued to prosper after the establishment of the Mandate, with exports increasing “fourteen-fold between 1920 and 1937.”Footnote 68 Despite the crisis that beset the rest of the agrarian economy, the citrus industry remained profitable well into the mid-1930s, and Palestinian citrus farmers, both Arabs and Jews, continued to compete vigorously to invest in lands to plant new groves.Footnote 69

Their optimism infected even those without ample means; a Zionist surveyor noted in 1932 that “even small [Arab] landholders from Jaffa and elsewhere [bought new land to] plant citrus orchards.”Footnote 70 British officials, and, later, the scholars who based their analyses on the reports written by them, assumed that Arab capital for new groves came solely from Arab land sales to Zionists.Footnote 71 This may have been true in some cases, but it is clear from this story that many Arab Palestinians wishing to invest in citrus also approached the Arab banks directly for capital.

Al-Faruqi, the writer of the phlegmatic letters quoted at the start of this article, was one such investor. A wealthy landowner from Ramla, he had been purchasing lands to plant citrus orchards since 1929; by 1936, he owned two groves together worth £P75,000, which he funded via loans from both the Arab and Agricultural Banks.Footnote 72

Al-Faruqi's biography teems with curious facts: having gone blind as a child, he nevertheless pursued a legal education, studying Islamic jurisprudence in Cairo and receiving a law degree in Istanbul. He remained in Istanbul, dabbling in political activities, until he fell afoul of the Ottoman authorities (the first of several instances in a life full of entanglements with authority) for having protested Ottoman requisitioning policies during the First World War. Expelled from Istanbul, al-Faruqi went to Cairo, where he waited out the war by earning a doctorate in law.Footnote 73

Al-Faruqi returned to Palestine upon the establishment of the Mandate to start his law practice, but with dubious success, being disbarred in 1928 for having allegedly cheated and defrauded his customers.Footnote 74 He protested his innocence for decades, decrying the proceedings as “a grave miscarriage of justice” and appealing for reinstatement of his license, but successive chief justices refused, deeming his conduct “disgraceful, fraudulent and unprofessional” and declaring him lucky to have avoided imprisonment.Footnote 75

This dishonor did not dampen al-Faruqi's political ambitions. Active from the early 1910s in political organizations in Palestine and Istanbul, he had become, by the 1920s, a fixture in local politics and an early stalwart of the anti–al-Husayni opposition.Footnote 76 He was also a prolific essayist, publishing strident nationalist and anti-Zionist editorials in local newspapers before establishing, in 1932, his own newspaper, al-Jami‘a al-Islamiyya. But here, again, he clashed with the British authorities, who frequently suspended and eventually banned his paper in 1938.Footnote 77 His political views also found expression in poetry; an early poem, published in November 1913 in Filastin, bluntly warned of the dangers of Zionist land purchases.Footnote 78

Al-Faruqi also was, apparently, a man of such considerable appetite that his friend (and publisher of the newspaper Mir'at al-Sharq) Bulus Shahada once retorted, when inviting him for dinner, “You are welcome to come but your belly must be left behind.”Footnote 79 But it was not overindulgence that led to his financial troubles. He was, like many of his fellow Arab citrus growers, a victim of overconfidence, bad luck, and unfortunate timing.

4. Crises

Two years after al-Faruqi approached the Arab Bank for his first loan in 1933, the Palestinian citrus industry suffered a steep decline. This was partly due to local factors: overproduction by optimistic farmers who planted new groves despite declining demand abroad; competition between local Jewish and Arab growers that pushed prices down; poor packing quality that frequently led to fruit rot; and abundant Spanish citrus harvests that glutted the international market.Footnote 80

But a sharper blow came from the delayed effects of the global depression, which by the mid-1930s had reduced the appetite for imported fruit in many European countries and eventually led to a trade war in which Britain, Germany, and other European countries erected tariffs against imports to protect domestic production.Footnote 81 Britain's decision to exclude Palestine from its official definition of Empire, thus denying Palestinian citrus imports the preferential terms offered to goods from other colonies, was a particularly consequential hit.Footnote 82

By April 1936, when Arab Palestinian groups mobilized to organize a countrywide boycott to protest Zionist immigration, arms smuggling, and British inaction, the local citrus industry was already in crisis. Most Arab citrus growers nevertheless obeyed the call to collective action by contributing to the strike fund and forgoing citrus exports.Footnote 83 But, as the months wore on, their losses—already escalating due to falling prices and reduced demand caused by the global depression—soared. By September 1936 matters were grave enough for Filastin, the leading Arabic newspaper, to call for a reprieve from the boycott for citrus growers, although some radical strike committees disagreed.

An unusually wet winter in 1936, leading to fruit rot, dealt yet another unforeseen blow, and the 1936–37 season turned into the worst ever on record for Jewish and Arab growers alike, with 75 percent indebted by at least one-third of their orchards’ value and 20 percent indebted for amounts exceeding their assets.Footnote 84 The Arab Chamber of Commerce's 1937 directory bemoaned the “grave situation,” estimating that Arab growers “suffered losses of £P2 per case.”Footnote 85

This explains al-Faruqi's financial troubles. He had applied for his first loan from the Arab Bank for P£3,000 in 1933, at a time when banks and citrus growers were brimming with optimism for the future of the Palestinian citrus industry. Between 1933 and 1936 he continued to take several short-term loans from both the Arab and the Agricultural Banks, most likely to purchase more lands to plant groves, which he regularly settled when due.Footnote 86 During the 1935–36 citrus season he took additional loans of £P4,000 and P£2,000 from the Arab and Agricultural Banks respectively, but, instead of paying these when due, issued each bank a promissory note guaranteed by a friend.Footnote 87 In December 1936 he issued new promissory notes, essentially rolling the loans over without paying down any of the principal or interest. The banks accepted the notes, but added 8 percent interest, compounded every three months. By mid-1937, when the banks demanded repayment, the total amount al-Faruqi owed was over £P8,500, excluding interest.Footnote 88

This was an enormous sum by Palestinian standards; to put it in context, a luxurious property in the heart of Jerusalem known as the Palm House (which today comprises the grounds of the storied American Colony Hotel) was bought by a group of missionaries in 1933 for £P6,000.Footnote 89 In 1930 British officials estimated that the average debt of a rural Palestinian family was £P27, with an average family income of £P25–30; al-Faruqi's debts added up in 1937 to over three hundred times that amount.Footnote 90

Despite the enormity of his loans, al-Faruqi had initially boasted, in early letters to his lawyers, that his debt did “not constitute more than 10% of my fortune.”Footnote 91 But by early 1937, suffering from a serious liquidity shortfall, he lamented that, although “possessing large and valuable property . . . [he] unluckily had no cash at hand.”Footnote 92

His lawyers summarized the problem: “Our client is a man of considerable property but at the same time . . . a man of considerable poverty.”Footnote 93 By 1939, unable to furnish even the modest sums required for court fees, this man of considerable property confessed: “I am in a desperate position and cannot raise any money whatsoever.”Footnote 94

5. Shuman's Decision

Al-Faruqi and his fellow citrus traders were not the only ones battered by the successive crises of the 1930s. As he recalled years later in his autobiography, ʿAbd al-Hamid Shuman spent several sleepless nights during the summer of 1937, fretting over the failing financial health of his two banks which had “granted too many loans . . . to the great figures of the community who feel that they can borrow huge sums indefinitely.”Footnote 95

By mid-1937, the revolt, then in its fifteenth month, brought the already-faltering Arab economy to its knees: unemployment soared; property values plummeted; consumption stalled; credit vanished; economic investment, the province of those once-optimistic entrepreneurs, halted; and the citrus farmers the banks had once lent to so enthusiastically defaulted, one after the other, on their loans.Footnote 96 Even the Jewish Agency's Arab Bureau, not the most neutral source for evaluating the economic realities of Arab Palestinians, observed that “bankruptcy . . . ha[s] become a regular event [in Jaffa].”Footnote 97

Bankruptcy loomed large, too, for both of Shuman's banks. The Arab Bank's 1936 year-end report show how heavily it was leveraged, with the ratio of loans to deposits 129 percent in 1935 and 84 percent in 1936 (see Table 2).Footnote 98 Although the lack of comprehensive statistics makes it difficult to compare it to its competitors, Table 3 shows that, at year-end 1936, the six foreign banks collectively held 77 percent of Palestine's total deposits and 59 percent of total debts, whereas the local banks, of which the Arab banks were two of seventy, held only 22 percent of cash deposits but 40 percent of debts. The Arab Bank in 1936 held less than 2 percent of the country's cash deposits but at least 3 percent of its total debt.Footnote 99 If the majority of that debt were to go unpaid—as was the case at year-end 1936—it is easy to see why the bank struggled to stay solvent, and why the Arab Bank later described the period as constituting “its second greatest crisis.”Footnote 100

Table 2. Arab Bank Balance Sheets, 1935–1936

Source: Arab Bank Ltd., Year-End Balance Sheets, 1935 and 1936, S09/2003/1, Central Zionist Archives. All amounts in Palestinian pounds.

Table 3. Arab Bank and Competitors, 1936

Sources: Columns (1) and (2): George Hakim and M. Y. al-Husayni, “Monetary and Banking System,” in Economic Organization of Palestine, ed. Saʾid B. Himadeh (Beirut: American Press, 1938), 468; columns (3) and (4): Arab Bank Ltd., Year-End Balance Sheets, 1935 and 1936, S09/2003/1, Central Zionist Archives.

Just as during the first crisis in 1935, Mandate officials made no attempt to help the two Arab banks weather this new storm. This despite the alarm raised by a British official, F. G. Horwill, who had been appointed as temporary examiner of banks by the Mandate high commissioner in 1936, and who warned, as early as July 1936, of the “possibility of a major banking crisis arising as a result of the present protracted strike.”Footnote 101 He doubted the “ability of many local banks to withstand the present upheaval,” and urged Colonial Office officials in London to intervene.Footnote 102

But Horwill's interlocutors at the Colonial Office took no action, offering the excuse, in May 1937, that the “immediate danger [of a banking crisis] was averted as the disturbances have come to an end,” and the hope that “the local banking situation would improve soon.”Footnote 103 This was akin to the myopic prognosis offered a few months later by British officials who, when charged with investigating the underlying causes of the 1936 “disturbances,” concluded that “it is difficult to detect any deterioration in the economic position of the Arab upper classes,” and “Arab peasants are on the whole better off than they were in 1920.”Footnote 104

By the summer of 1937 both of Shuman's banks were in crisis, with no governmental assistance on offer in the form of emergency bridging loans or loan consolidation programs or other regulatory relief measures that might have helped staved off insolvency.Footnote 105 This reinforced Shuman's view that the Mandate existed to protect alien colonial interests, and hardened his resolve to take all necessary steps to ensure his banks’ survival. It was in this context that he decided, after (as he claimed in his memoirs) many sleepless nights, that his banks would have to sue to collect overdue loans.

Not all Palestinian capitalists thought alike; the Agricultural Bank's Chairman, Ahmad Hilmi ʿAbd al-Baqi, Shuman's father-in-law and one of the Arab Bank's earliest financiers, disagreed with this “drastic action.”Footnote 106 He advocated “leniency towards suffering debtors during [this] crisis,” arguing that the banks should defer collecting loans “not out of sentiment or generosity, but because the welfare of the Arab cause required it.” But Shuman was convinced of his decision, and, overriding Hilmi, ordered the banks to pursue all defaulting debtors in court. He claimed to have overruled his father-in-law “only reluctantly,” knowing it would upset the man who was not only “a close family member” but also “an intimate friend and co-worker in the Arab cause.” But, he rationalized, “in this conflict between personal and professional loyalty,” the latter had to prevail.

It did so at a price, engendering a permanent rift between the two men. Hilmi resigned his chairmanship of the Agricultural Bank, and later started his own bank, a watered-down clone of the Agricultural Bank, which he called, perhaps pointedly, the National Bank (al-Bank al-Watani).Footnote 107

Some scholars have emphasized the significance of the al-Nashashibi–al-Husayni schism that preoccupied many Palestinian elites at this time. Issa Khalaf, for instance, has argued that Shuman was “tacitly allied” with the al-Husayni camp whereas Hilmi was a leader of the opposition, which was, he has implied, what led to the creation of the “rival” National Bank.Footnote 108 But in fact it was the disagreement about enforced loan repayments during the revolt, and not factional politics, that led to the falling-out between the two men, and, despite this, their banks remained closely associated for years, so much so that some sources have confused Hilmi's National Bank with Shuman's Agricultural Bank.Footnote 109 Moreover, as Table 1 reveals, whatever Shuman's politics, his banks had customers from both factions, and, when it came to it, sued everyone to collect debts; the list of defendants included men like al-Faruqi (who, like Hilmi, was a pillar of the anti–al-Husayni opposition) as well as various members of the al-Husayni family.Footnote 110

Nor can Shuman's obduracy when it came to collecting debts be reduced to a capitalism that trumped nationalism when expedient. Sherene Seikaly argues that Palestinian businessmen “masked their interests as those of the public,” and exhibited a “flexible nationalism” that privileged their economic interests when necessary.Footnote 111 But whatever his private motivations—which are as inscrutable as anyone's—Shuman's nationalism cannot be easily devalued: he publicly supported the strike from the beginning and continued to do so even as the months wore on and his banks verged on bankruptcy. British officials, for their part, never stopped viewing him with suspicion and derision, deeming his banks “of inferior standing and not a little suspect.”Footnote 112 Even Horwill, who sympathized with local banks in crisis, urged “an immediate investigation of both [Arab banks’] affairs” during the strike, because their “policies are influenced by political considerations.”Footnote 113 Finally, when the strike grew into armed revolt, Shuman risked the future of the Arab Bank by allowing it to be used as a clandestine channel for funds from Iraq to various militant Palestinian groups. This led to his arrest by the Mandate authorities and imprisonment and eventual hospitalization in Acre prison for nine months.Footnote 114

Nor can Shuman be accused of being so blinded by his focus on his banks as to be indifferent to the dangers of Zionist land purchases: although he believed institutions were more important than land, his despair at the rate at which Arab lands were being sold to Jews motivated the Arab Bank's protracted legal battle with the Jewish National Fund (JNF), the main Zionist land-purchasing institution, for the rights to the property of one of the bank's debtors, Tawfiq al-Ghusayn, who died in 1939 leaving his mortgage unpaid.Footnote 115 The Arab Bank purchased the mortgage to preclude a public auction of the property, but was outmaneuvered by the JNF, which contested the bank's claim on the grounds that it had “no certificate from the High Commission to hold land.” The Zionist fund, aided by supportive rulings from the Jaffa district court, eventually wrested the property from the Arab Bank by offering al-Ghusayn's heirs a significantly higher amount than what the bank paid for the mortgage.Footnote 116

These episodes indicate the difficult positions into which Arab Palestinian businessmen like Shuman were forced by the structural and economic constraints of the time. Suing compatriots on one hand and Zionist funds on the other, Shuman grew all the more embittered against Zionism and British colonialism during the revolt, even while being reproached by Hilmi for not being “more magnanimous to debtors” and by the debtors themselves, who protested that “the banks should come to our aid under present conditions of financial stress.”Footnote 117 But Shuman was convinced that his actions “served the highest national cause.” “Bolstering the economy,” he wrote, “is far more important than showing leniency to debtors . . . . This is a duty I owe the nation, and I am determined to perform it.”Footnote 118 His banks’ lawyers duly wrote to all debtors in the autumn of 1937, demanding payment of overdue debts and threatening legal action in case of nonpayment.

6. Lawsuits

The Arab Agricultural Bank sued al-Faruqi on 10 May 1938 “for the recovery of £P2000 plus interest.” Soon thereafter the Arab Bank launched its own suit for £P6428 plus interest.Footnote 119 In January 1939, al-Faruqi wrote a cryptic letter to an eminent Jewish lawyer, Bernard Joseph, “on behalf of a person who is indebted to a number of banks with a few thousand pounds,” requesting, in a postscript, that the lawyer's response be marked “private.”Footnote 120

A few months later, dispensing with pretense, al-Faruqi engaged Joseph's firm to mount his defense against both banks’ suits. This decision on the part of a well-known Arab Palestinian politician to hire a Jewish firm is curious enough, but it becomes even more so in light of Joseph's prominence, at the time, as a member of the Mapai party and legal advisor to the Jewish Agency.Footnote 121 Given that al-Faruqi remained a publicly vocal anti-Zionist throughout the time he worked with Joseph, it is tempting to nominate him to the ranks of those Palestinian “collaborators” who, some scholars have argued, secretly cooperated with Zionists to further their own financial interests while publicly declaiming their nationalism.

Hillel Cohen has suggested, for instance, that people like al-Faruqi were “stalwart collaborators,” who “continued to act in concert with the Zionists . . . at the high hour of Palestinian nationalism” (i.e., during the revolt).Footnote 122 Although Cohen acknowledges that “we cannot know what their motives were,” he argues that, ultimately, these collaborators “put their personal interests before their political ideas.”Footnote 123 Kenneth Stein puts it more bluntly, stating: “Arab opposition to Zionism was inauthentic and inconsistent as far as land sales were concerned.”Footnote 124

But al-Faruqi's letters to his lawyers, written over the course of many years as his cases wound their ways through the Palestinian courts, suggest a more complicated story. This correspondence, in turn truculent and desperate, reveals what lay at the heart of the dispute, as far as al-Faruqi was concerned: land. Joseph's firm was famous for winning land dispute cases, and it is likely that al-Faruqi hired it to strengthen what he knew was a weak defense: he could not pretend that he didn't owe the banks money; could not dispute the amounts claimed; and did not expect to win in court. All he wanted, as he confessed to Joseph, was “somehow to obtain a little extension of time.”Footnote 125

Delay was crucial for al-Faruqi because he didn't have the £P10,000 he would need if both cases were decided against him, and he knew that the only way to raise that sum would be by selling his property. Given the depressed land prices at the time, he knew he would be forced to sell at a considerable loss, and feared that the likely buyers, given the crisis afflicting the Arab Palestinians at the time, would be the Zionists.

After a momentary slowdown in the early 1930s, Zionist land purchases had returned, during the revolt, to their highest-ever levels. Although precise numbers of sales during that period are hard to establish, given the politics involved, and because some purchases were conducted off the books and through brokers, Kenneth Stein estimates that Zionist funds and private buyers bought at least 100,000 dunams of land officially and an additional 60,000 unofficially between 1936 and 1940.Footnote 126 In 1939 alone, the year after the banks launched their lawsuits, another source suggests that the Jewish National Fund unofficially bought 53,500 dunams, its largest annual acquisition in a decade.Footnote 127 Al-Faruqi's own lawyer, Bernard Joseph, made pointed offers to help him find a buyer, writing, unprompted, shortly after having been hired, to introduce him to a “Moritz Plaut, dealer in real estate . . . who may be of assistance should you wish to dispose [of] your property.”Footnote 128

Al-Faruqi did not take up this offer. Adamant that the sale of his lands would be a “catastrophe,” he urged his lawyers to do their best to postpone the proceedings.Footnote 129 In letter after letter, he repeated his refusal to sell, while railing alternately against the Mandate authorities for not helping citrus growers “when our condition is abnormal and beyond the limits of the law” and the banks for their “revengeful spirit.”Footnote 130 When he could no longer postpone the defense, he urged his lawyers to use legal technicalities to keep the cases in court as long as possible; as the exasperated chief justice of the Jaffa District Court noted, he made “every effort to protract the proceedings [and] . . . every possible device to put off the evil day of judgment.”Footnote 131

And yet, that evil day came: the district courts of Jaffa and Jerusalem eventually ruled, as he had feared, in both banks’ favor and ordered a public auction of the properties with which al-Faruqi had secured his loans. Once again al-Faruqi fought for time, begging his lawyers to do whatever they could to postpone execution of the judgment; again adamant that he would not sell his land; again stressing the devastation this would entail, he pleaded: “Execution means sale of property, because, presently, there is no such amount of money available . . . . This will result in enormous damages . . . it will be unrepairable.”Footnote 132 When his appeals failed, al-Faruqi wrote personally to the president of the Supreme Court, emphasizing “the manifold loss I would incur if an auction is taken at the moment.”Footnote 133 The man who had written trenchant editorials criticizing British rule in Palestine, whose own newspaper had been shuttered by the authorities for its anti-colonial stance, ended with a groveling plea for the “help” and “kind consideration” of “British justice.”Footnote 134

But British justice was unmoved. The Supreme Court judge acknowledged that al-Faruqi was “an unfortunate man,” noting the “untimely death” of one son, the imprisonment of the other, and the defendant's blindness.Footnote 135 Nevertheless, ruling that “there is no merit whatsoever in this appeal,” he ordered al-Faruqi to pay both banks the full amounts owed, plus interest, plus, adding insult to injury, the banks’ legal fees, “to remove further protraction.” Twisting the knife, the Supreme Court authorized the Arab Bank to sell al-Faruqi's orange crop while waiting for the proceeds from the auction of the groves. The bank duly sold al-Faruqi's oranges—those fruits that had once inspired such optimism in both debtor and creditor—and in April 1943 served him with a bankruptcy notice.

The archival record does not indicate what happened next, nor how al-Faruqi's story ends. We do not know if, despite his efforts, he was compelled to sell his lands in a bankruptcy auction, nor do we know if the banks ever collected their debts. The only clue we have lies in a cryptic undated note, buried in the Joseph files. The man who had once written a poem railing against his countrymen for bartering their lands “for gold” to the highest Zionist bidder, who had fought for years in court to avoid doing so himself, wrote that he had “registered a mortgage for £P13,000 in August 1944 in favor of one Joseph Miller.”Footnote 136

We do not know who Joseph Miller was. Kenneth Stein, who provides a partial list of Arab land sellers in this period, does not include al-Faruqi's name among them.Footnote 137 But it seems inevitable that Joseph Miller was a Zionist purchaser, the very kind that al-Faruqi had tried, for years, to evade.

Conclusion: Bankrupt

Shaykh Sulayman al-Taji al-Faruqi had wished to “get rid of the Agricultural Bank by any means.”Footnote 138 He failed to prevent his own bankruptcy, and he failed to prevent the auction of his lands, but in this one goal he succeeded, for the Agricultural Bank, despite all Shuman's efforts, went bankrupt in 1941.

The start of the Second World War in September 1939 dealt several critical blows to the faltering institution. First, the local citrus industry suffered, at the onset of the war, from the closing off of Mediterranean shipping lanes (which effectively ended all seaborne citrus exports); from vanishing demand from European export markets; and, as al-Faruqi complained in his letters, from the Mandate government's initial reneging on promised advances for citrus cultivators.Footnote 139 These factors combined to leave the Palestinian citrus growers who comprised the bulk of the Agricultural Bank's customers even less able to repay their loans when the war started than they had been during the crisis of the late 1930s.

Next, the bank was hit, like all other banks in Palestine, by an unexpected bank run in the summer of 1940 set off by the German invasion of Holland and Belgium in May and the entry of Italy into the war in June. This led to a rash of heavy withdrawals by panicked customers, which the bank's cash reserves, already depleted by the mounting overdue debts, could not fulfill.Footnote 140 The Mandate government then dealt the final fatal blow: thinking to forestall a countrywide banking collapse triggered by the run, it amended the existing banking ordinance to stipulate that every bank in Palestine had to “maintain at least ten percent of their cash reserves liquid at all times.”Footnote 141 By 1941 the Arab Agricultural Bank was in no position to meet this requirement, for it was then, as ʿAbd al-Hamid Shuman lamented, “without liquidity, most deposits withdrawn, and no longer in a state to undertake normal business.”Footnote 142 The Mandate authorities, instead of helping the ailing bank, ushered it to its demise, ordering it “to cease to function and go into liquidation in compliance with the capital provisions of the Banking (Amendment and Further Provisions) Ordinance of 1937.”Footnote 143

The Arab Agricultural Bank was duly liquidated in 1942.Footnote 144 It was not the only bank to suffer from the Mandate government's stringent new reserve requirements: an official report estimated that a staggering fifty-two local banks were forced to close between 1936 and 1945, with only twenty local banks (including the Arab Bank) remaining solvent at the end of the war.Footnote 145 But the Arab Agricultural Bank's demise represented not only a steep financial loss for the Arab Bank, which had to take a charge of £P8,000 to absorb its assets, but also the diminishing of Shuman's dreams, and those of all his compatriots, who had put such store in the bank's promise to “help the Arab peasant preserve the ownership of land in Palestine.”Footnote 146

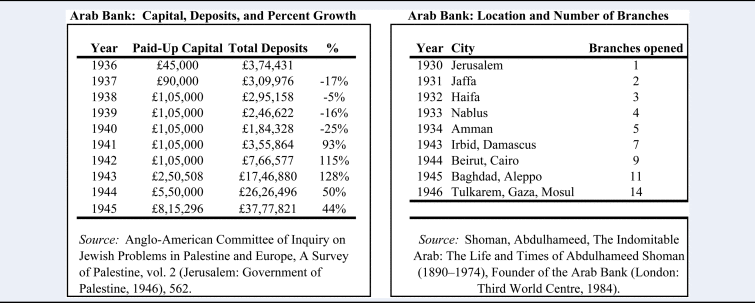

The Arab Bank, however, managed to survive on the strength of its healthier cash reserves, and, in 1943, after years of losses, turned a slim profit. In this it was helped by a wartime economic boom that began in 1941, generated by rising demand for local goods and a slew of Mandate policies geared toward boosting the local economy and provisioning British and allied troops stationed in the region.Footnote 147 By 1946 the Arab Bank's deposits totaled £P4 million, an impressive increase from the £P375,000 it had started with, and which was, as economist Jacob Metzer has noted, the “most rapid growth of any financial institution in Palestine at the time” (see Table 4).Footnote 148 The bank had by then expanded to Transjordan, Syria, Iraq, and Egypt (Table 4), providing a counterargument to those who have implied that Arab Palestinian businessmen in this period were too disorganized, unskilled, or unsophisticated to succeed economically.Footnote 149 But this success came, as this narrative has shown, at a steep price.

Table 4. Growth of Arab Bank, 1936–1945

The Arab Bank managed to survive the successive crises that battered the Palestinian economy in the late Mandate years not because of governmental support, but because Shuman relentlessly pursued what he called his “duty to the nation” by ensuring that his one remaining institution survived. Burned by both banks’ difficulties during the 1930s and by the Agricultural Bank's recent bankruptcy, he radically revised the Arab Bank's business model in 1941. Discarding his previous grand plans to build the “national economy” by investing in productive industries that would generate employment and ensure sustainable growth, Shuman decided that the Arab Bank should reorient itself toward a new wartime business of issuing short-term letters of credit to merchants looking to import food into Palestine from Egypt and Sudan.Footnote 150

As political scientist Issa Khalaf has observed, Palestine's concomitant wartime boom and food shortages had engendered the growth of a freshly minted commercial elite who grew rich by investing in food-import activities during the war. This new commercial class, as Khalaf explains, eclipsed in economic wealth and entrepreneurial energy (but not social or political standing) old landowning elites like al-Faruqi and al-Ghusayn.Footnote 151 It was to these new elites that Shuman turned in the early 1940s. Ignoring protests from other members of the Arab Bank's board, who felt that the bank should not become “so preoccupied with the import business,” Shuman grimly evoked the bitter lesson he had learned: “there is small profit in granting ordinary loans.”Footnote 152

And so by the mid-1940s the Arab Bank became a key source of short-term capital for Arab Palestinian food importers. But in one area the bank's policies remained unchanged: as Tables 1 and 4 indicate, it continued to sue defaulting customers well into the late 1940s, even as its profits grew. This policy of forswearing “ordinary” new loans on one hand while continuing to chase overdue old ones on the other most impacted the bank's earlier base of customers, the landowning, once-wealthy-but-now-bankrupt elites like al-Faruqi. We do not know how representative al-Faruqi's case is, but it is clear from the list of lawsuits that he was but one of many of the bank's customers who, still saddled with debts accrued from the 1930s, were forced by the bank's lawsuits to sell their lands against their will.

It is possible that some of these landed elites recovered a portion of their former wealth during and after the war years, helped, like many of their compatriots, by the wartime boom. But this boom had, as one observer fretted, a “false veneer,” for the war also brought surging inflation, strict austerity measures, and a rapid transformation of thousands of Arab Palestinian peasants from rural agriculturalists to urban workers.Footnote 153 And even if some of the old landed elites did regain their wealth, they never recovered lands already sold: for the Zionist goal of settling Palestine ensured that a piece of land, once bought by a Zionist, was never again sold back to an Arab Palestinian.Footnote 154

Accurate data on land transactions in this period are difficult to establish, given the politics involved, but scholarly estimates suggest that the Zionist land purchases were so abundant between 1936 and 1940 that they ensured the eventual territorial viability, and thus existence, of Israel.Footnote 155 Although there were likely other factors that induced Arab Palestinians to sell their lands to Zionists in the late Mandate period, this story has shown how the Arab banks were, at least in some cases, the unwitting “agents of Arab dispossession and Jewish colonization.”Footnote 156

This was not the outcome Shuman had wanted. When he had first returned to Palestine from New York in 1929, buoyant, like so many other entrepreneurs, with optimism, he took the rational, if ambitious, decision to build a national bank that would serve as a vehicle for national capital investment and growth, and thus an essential component of the nation-building process, as his contribution to the anti-Zionist struggle. On the first day of the Arab Bank's operation, he had exhorted his new staff:

Wherever you go—in Jerusalem, Jaffa, or Haifa—you will see evidence of Zionist and colonial institutions prospering and expanding. In their prosperity we can discern only our own weakness and dependence. Every colonial or Zionist institution that succeeds in our country drives yet one more nail into the coffin of our Palestine. But every Arab venture that manages to do well serves as a shield in the protection and defense of Palestine. Let's get to work!Footnote 157

Shuman's optimism vanished during the revolt, when his banks faced collapse and he was forced to decide between saving them or showing leniency to his indebted customers. He could not rely on the colonial government, whose officials did not prioritize distressed Arab banks, or on the international banks, whose managers thought his too precarious for assistance. So he was compelled to sacrifice the interests of his oldest customers to what he deemed the greater good, to what he felt was the only way to prevent Palestine from becoming a “coffin.” Had the local economy not been devastated before and during the revolt; had the Mandate authorities done more to protect both banks and customers; had the Jewish National Fund not possessed the funds, or the inclination, to purchase distressed Arab estates; had the Zionists been equally affected by the economic crises that destroyed the Arabs, this story might have had a different ending. As it was, al-Faruqi, upon hearing of the court-ordered auction of his property once his appeals had failed, remarked that “[the court's decision] is strange and very ridiculous indeed, and if it is to be accepted, then Palestine will have fallen into bankruptcy legally as well as politically.”Footnote 158

This is where the narrative of financial life in Palestine diverges from financial histories elsewhere. No routine story of banker versus customer, of lender versus borrower, but an account of land against bank, of nationalist against nationalist, of bankrupt against bankrupt, of optimism turned to desperation, which leads in a grim, unidirectional, irreversible line to the dispossession of Palestine's landed elites and to the diminution of the dreams of its capitalists and bankers.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the many people who helped me with this article. For generously sharing sources essential to this research: Munib Masri (who gifted me a copy of Shuman's biography); Nahed Bishara (who allowed me access to her family's copy of the 1937 Arab Chamber of Commerce Directory); and the staff at the Shehadeh Law firm (for allowing me to see what remained of their Mandate-era legal files). I'd also like to thank the staff at various archives for helping me navigate their collections: particularly, Helena Vilensky at the Israeli State Archives; Rachel Rockemacher at the Central Zionist Archives; and the staff at the reading rooms of the British National Archives and Barclays Bank Archives. For their helpful comments on drafts, I'm grateful to: Cynthia Brokaw; Jonathan Conant; Beshara Doumani; Gary Fields; Thomas Mariotti; Andrew Schrank; the participants of the Legal History and Watson Work in Progress workshops at Brown University; and of the Palestine Mandate workshop at McGill organized by Laila Parsons. I'm especially indebted to Alex Winder for his insightful and generous (and repeated!) readings, and to Sherene Seikaly, without whose interventions and encouragement this article would never have taken shape. I've also benefited immeasurably from the thoughtful comments provided by the three anonymous IJMES reviewers and from the deeply considered guidance provided by the IJMES editor, Joel Gordon and assistant editor, Sarwar Alam and from the meticulous editing by the Cambridge University Press copyeditors. I am grateful for two grants that made this research possible, from Brown University's Junior Faculty Development fund and from the Institute of Advanced Study's (Toulouse School of Economics, Toulouse, France) grant ANR-17-EURE-0010 (Investissements d'Avenir program). Finally, it anguishes me to acknowledge my deepest debt to two people who guided this research from its inception but did not live to see it published: Fu'ad Shehadeh, who taught me much about legal life during the Mandate era in Palestine and shared many details about Sulayman Taji al-Faruqi; and Roger Owen, who, taught me everything, and who, until his last moments, provided vital criticisms that shaped this work, and impatiently urged its completion.