According to Kachru's (Reference Kachru and Kachru1992) concentric circles framework, the use of English across countries can be grouped into three circles: an inner circle in which English is the native language, e.g., the UK; an outer circle in which English serves certain functions due to colonization, e.g., India; and an expanding circle in which English is taught as a foreign language, e.g., Turkey. Although many studies have examined the role of English in higher education in Turkey (e.g., Arik & Arik, Reference Arik and Arik2014; Karakaş, Reference Karakaş2016), the use of English in the media has not been explored to the same extent. The present study addresses the use of English in movies in theaters in Turkey. The study shows that English is the language of 50% of the movies shown in theaters in Turkey. Therefore, our findings provide further evidence showing the prevalence of English in Turkish movie theaters.

The spread of English has been observed in many domains of life – such as the media, the marketplace, and education – in outer circle countries such as Malaysia (Stephen, Reference Stephen2013) and expanding circle countries such as Greece (Oikonomidis, Reference Oikonomidis2003), Macedonia (Dimova, Reference Dimova2003), Azerbaijan (Shafiyeva & Kennedy, Reference Shafiyeva and Kennedy2010), and several countries in (East) Asia (Kirkpatrick, Reference Kirkpatrick2012) as well as Turkey (Doğançay–Aktuna, Reference Doğançay–Aktuna and Kiziltepe2005; Büyükkantarcı, Reference Büyükkantarcı2004; Selvi, Reference Selvi2011, Reference Selvi2016). The spread of English can be seen in movies offered in languages other than local languages, which are often subtitled or dubbed. In some countries, such as Uganda, interpreters perform simultaneous voice-overs in the theaters (Achen & Openjuru, Reference Achen and Openjuru2012). Watching movies or TV shows in English or making movies for ESL classes are strategies used to help international students learn English (e.g., Chamberlin Quinlisk, Reference Chamberlin Quinlisk2003; Rees, Reference Rees2005; Qiang, Hai & Wolff, Reference Qiang, Hai and Wolff2007; Kebble, Reference Kebble2008). The spread of English should be investigated with respect to the language's use not only for pedagogical contexts and purposes but also in daily life. However, little is known about the extent to which speakers of other languages are exposed to English while watching movies. The present study aims to answer this question by focusing on international movies in theaters in Turkey.

The research questions that this study explores are the following:

1) How are inner, outer, and expanding circle countries represented in movies shown in Istanbul, Turkey?

2) To what extent do the titles, trailers, and movies in theatres use English, Turkish, and other languages?

Methods

The present study is a descriptive quantitative study that utilizes corpus tools to investigate the role of English in movies shown in theaters in Istanbul, Turkey in 2014. Quantitative methods are necessary to capture the extent and breadth of this global phenomenon, as widespread and ubiquitous as the spread of English. Without comprehensive quantitative descriptive studies, we run the risk of reaching incomplete, if not misleading, conclusions, as the validity of our results and conclusions depend on a match between the phenomenon under investigation and the measures or scales we use to examine it. Needless to say, descriptive quantitative studies alone cannot provide all the answers we seek, as we need depth as well as breadth. Nevertheless, descriptive quantitative studies are a necessary starting point not only for subsequent comparative analyses but for the achievement of a better understanding of the spread of English globally.

We also benefit from corpus methods because these are among the data collection and analysis procedures that utilize quantitative methods extensively, taking advantage of large-scale, accurate, and reliable data (McEnery, Xia & Tono, Reference McEnery, Xiao and Tono2006). As Bolton (Reference Bolton2005) observed, English corpus linguistics is one of the contributing fields to the study of world Englishes; its aim is ‘to provide accurate and detailed linguistic descriptions of world Englishes’ (p. 70). Most corpus-based research focuses on specific linguistic features – for example, those used in various genres, languages, and disciplines by diverse groups of language users. However, corpus-based research has much wider applications than describing or comparing linguistic features. One such specific application is to look at publicly available online data that allow us to investigate the extent of the spread of English in various contexts, which we do in the present study.

To examine the languages of movies shown in theaters, we created a corpus of information about movies, extracted from online websites. We chose movies shown in theaters in Istanbul, Turkey. The theaters in Istanbul provide a good representation because Istanbul is the largest city in Turkey, with a population of about 15 million, which constitutes 20% of the nation's population. We collected data from a website, beyazperde.com, which is the oldest (established in 1998) and most popular website covering all the movies and movie theaters in Turkey. Currently, beyazperde.com is part of an international media group, Webedia. Every week, we visited this website and downloaded information about the week's new movies, which changed every Friday. Occasionally, we checked data on similar websites to ensure its reliability. We also consulted imdb.com, the renowned international website for movies, for further analysis in comparing the data from the two sources.

Corpus tools have previously been used to investigate movies. However, these studies have focused primarily on specific linguistic features in movie scripts, e.g., Pinto (Reference Pinto, Sardinha and Pinto2014). Because our main focus was the diffusion of English in movie theaters, we collected data primarily on the language choices in movies shown in Turkey rather than on the specific linguistic features in movie scripts. Our data contained the following information about the new movies of the week: title, date, genre (horror/comedy/action/drama, etc.), country of origin, language used in the trailer, synopsis, names of the movie theatres, and showtimes. We collected data from movies only when they were shown as the new movies of the week (n = 353) in 2014. We excluded data from movies if their showtimes were extended for another week or additional weeks. The data formats were .pdf and .xlsx.

Results

Overall, the findings showed that 1) although the movies shown in Istanbul, Turkey were produced in many different countries (50 countries), the distribution of these movies in terms of country of origin was uneven, e.g., over 40% of the movies were American productions, 2) movie titles were more likely to be in Turkish (90%), either because they were Turkish movies or because the titles had been translated into Turkish, than were movie trailers, with 56% of non-Turkish movies being in English with Turkish subtitles, and 3) although the languages of the movies looked diverse (39 languages), they were distributed unequally; for example, English was one of the languages in 60% of the movies, a finding parallel to our first finding about the countries of origin of the movies we investigated. We present our findings in more detail below.

Country of origin

We found that 353 movies (about seven new movies per week) were shown at movie theaters in Istanbul throughout 2014. Of them, 245 (69.4%) were international (non-Turkish) movies. Of these movies, 243 (68.9%) were produced outside Turkey. Two movies, Son Umut (The Water Divine) and Sesime Gel (Were Dengê Min [Kurdish]) were joint productions including Turkey, though their primary languages were not Turkish (i.e., English for the former and Kurdish for the latter). The remaining 108 movies (30.6%), including three joint productions, were produced in Turkish and in Turkey.

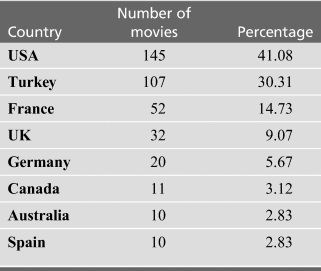

The 353 movies shown in movie theaters in Istanbul were produced in 50 countries. Because many of these countries made minimal contribution to the overall number, Table 1 presents only those countries in which at least 10 movies on the list were produced. As shown in Table 1, over half of the movies were produced by English-speaking countries such as the USA, the UK, and Australia, as well as Canada, where French and English are the commonly spoken languages. Turkish movies constituted about one-third of all movies shown in Istanbul in 2014.

Table 1: Countries of the movies shown at movie theaters in Istanbul (n > 10)

Our findings demonstrated that 56% of the movies were from inner circle countries; however, the distribution of the movies was not even among inner circle countries, as American movies constituted 41% of all the movies: larger than Turkish movies’ share, and twice the percentages of all the other inner circle country movies combined (see Anchimbe [Reference Anchimbe2006] for a discussion of how American variety of English affects other inner circle varieties). This finding is not surprising considering the fact that the market share of American movies compared to those of other countries is high and increasing around the world. For example, according to a report published by the European Commission, as early as 1998, 52% of new releases in European Union countries were American movies (Deiss, Reference Deiss2001). What is surprising is the lack of movies from outer circle countries. For example, considering the fact that India, an outer circle country, has one of the most productive movie industries in the world (Statistica, 2017), it is surprising that Indian movies do not have much representation in Turkish movie theaters; we found only three Indian movies, and Hindi was the original language of two of them. Another interesting finding regarding the country of origin of movies was the fact that there were only three expanding circle countries other than Turkey; only three European countries (France, Germany and Spain) were represented, although Turkey is not a member of the European Union. These findings suggest a close relationship between the languages represented in this context and the international relationships between the countries involved.

Languages of the titles

The data analysis suggested that Turkish was preferred in movie titles. Over 90% of the movie titles had either been in Turkish originally or translated into Turkish. Eighteen out of 353 (5.09%) titles remained the same, i.e., they were not translated into Turkish. However, most of those titles were personal names such as Yves Saint Laurent and Pompeii. The titles of three movies (1%) were originally in English and were not translated into Turkish. These were Non-Stop, Old Boy, and Mr. Banks, the latter of which is a personal name, though ‘Mr.’ is not used in Turkish.

Languages of the trailers

Compared to movie titles, movie trailers were more likely to remain in their original languages rather than be translated into Turkish. Of the 245 non-Turkish movies, 138 trailers (56.3%) were in English with Turkish subtitles, whereas 28 trailers (11.4%) were in English without Turkish subtitles. 31 trailers (12.6%) were dubbed in Turkish, whereas 44 trailers (17.9%) were in a language other than Turkish or English. The remaining four movies had no trailers. According to the data, unlike movie titles, movie trailers used English more and Turkish less. 67% of movie trailers were in English, and the vast majority of them had Turkish subtitles.

Original languages of the movies

The 353 movies were originally in a total of 39 languages, while 63 of them (17.84%) were in multiple languages. The diversity and multilingualism that these numbers suggest can be misleading because the percentages of languages other than English and Turkish were very low. According to Crystal (Reference Crystal2003), movies in English dominate not only movie theaters but also festivals and awards globally. As shown in Table 2, English was (one of) the language(s) of 60% of the movies. Turkish (30%) followed English. When we exclude Turkish, English becomes one of the languages in 86.12% of non-Turkish movies. As the highly disproportionate representation of movies that use English in Turkey illustrates, the wide reach of English often comes at the expense of other languages (Phillipson, Reference Phillipson1992). These numbers are especially striking considering the fact that Turkey is an expanding circle country. Selvi (Reference Selvi2007, Reference Selvi2011) argued that some of the practices related to English use in Turkey, especially extensive use of English in business names and shop signs, were more similar to those in inner circle countries than to those in expanding circle countries.

Table 2: Original languages of the movies shown in movie theaters in Istanbul (n > 10)

Languages of the movies in the theaters

In addition to looking at the original languages of the movies, we collected data about the language choices for these movies in movie theatres, as information about only the movies’ original languages is not very telling in terms of which languages moviegoers encounter in movie theaters. The movies were played for a total of 33,360 showtimes at 6,249 theaters (about five showtimes per theater). They were not equally distributed depending on their popularity; the range of showtimes per movie was between two and 616 while that of theaters per movie was between one and 104. As shown in Table 3, when we consider all the movies shown in theaters, 35% were in Turkish, 52% were in a language other than Turkish and shown with Turkish subtitles, and 13% were dubbed into Turkish. When we consider movies originally in English, about four-fifths of them were shown in English with Turkish subtitles, while the rest were dubbed. A closer examination of the data revealed 19 animated movies. These animated movies were dubbed most of the time (81% of the theaters and 88% of the showtimes), perhaps because of the fact that almost all animated movies target kids, and children may have trouble following subtitles. As Rudby and Saraceni (Reference Rudby, Saraceni, Rudby and Saraceni2006) stated, the decision to opt for dubbing or subtitles depends on the imagined audiences (p. 97). Table 3 shows that Turkish moviegoers prefer to watch foreign movies with Turkish subtitles.

Table 3: Languages of the movies in the theaters

Note that information was missing about the number of showtimes for the following 10 movies. International movies: 300: Bir İmparatorluğun Yükselişi (300 – Rise of An Empire), Paranormal Activity: İşaretliler (Paranormal Activity: The Marked Ones), Jack Ryan: Gölge Ajan (Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit), Bay Peabody ve Meraklı Sherman: Zamanda Yolculuk (Mr. Peabody & Sherman), Çocuk Büyütme Rehberi (No Se aceptan Devoluciones). Local movies: Sağ Salim 2: Sil Baştan, Frankenstein: Ölümsüzlerin Savaşı, Baskın 2, Bırakmak İstiyorum, 10. Köy Teyatora. Therefore, this section excludes the data from these movies.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study, we examined the movies shown in theaters in Istanbul, Turkey to investigate 1) how the movies from inner, outer, and expanding circle countries are represented and 2) the extent to which the titles, trailers, and subtitles of movies use English, Turkish, and other languages. We found that all three concentric circles were represented in the movies, as the movies were from 50 countries, while 39 languages from various language families were spoken. Moreover, more than one language was used in 17.84% of the movies. These two observations suggest signs of diversity and multilingualism in movies due to globalization. However, the role and status of English in relation to other languages displayed a less diverse picture because English, as ‘a lingua emotiva’ (Phillipson, Reference Phillipson2008: 250), appeared to be the most represented in this particular context; English accounted for 60% of all movies and 86% of all non-Turkish movies. The presence of inner circle countries more than any other group in the Turkish context illustrates the greater influence of inner circle countries on expanding circle countries such as Turkey. We also found that most of the time (about four-fifths of all showtimes), movies in English were shown in English with Turkish subtitles. The rest of the movies – mostly animated movies targeting children – were dubbed.

This predominance of English can stem from the supply of movies created by the highly productive Hollywood industry; however, it is certainly not because of proficiency in English or costs. First, most Turkish speakers are not fluent in English. Turkish is an agglutinative (extremely suffixal) language belonging to the Turkic/Altaic language family, whereas English is an analytical language belonging to the Germanic language family. This typological difference can arguably make it harder for Turkish speakers to learn English and vice versa. Similarly, these linguistic differences can make dubbing more challenging, as Ross (Reference Ross1995) has shown for translation of dialogues from English to Italian. Moreover, it is worth noting that English is the medium of instruction in only about one-fifth of undergraduate programs in Turkey (Arik & Arik, Reference Arik and Arik2014). Nor is English education as successful as planned (see British Council Report, 2015). For example, Turkish speakers who took a TOEFL iBT test in 2017 got a score of 78, whereas Dutch speakers got a score of 100 and Greek speakers got a score of 92 on average (ETS Test and Score Data Summary for TOEFL iBT Tests, 2017).

Secondly, the overrepresentation of English in the movies is not related to dubbing costs (though dubbing movies is more expensive than providing subtitles, thereby contributing to its less common use). Yet it is our observation that movies on national broadcasting TV stations are dubbed by almost all those stations, with the exception of a very few channels which provide only subtitles in Turkish. Moreover, the Turkish TV industry is very proud of its voice-over artists and dubbing skills. However, the picture is quite different when it comes to movies in theaters. Because Turkish people are not very proficient in English, the likely explanations for the predominance of English in Turkish movie theaters are the choices of movie theatres and the global dominance of Hollywood movies.

Our findings suggest that the predominance of English in movies affects not only the share of languages from countries other than Turkey but also minority languages. Evidence comes from Kurdish – one of the commonly spoken minority languages in Turkey, as 19% of Turkey's population is Kurdish in origin (The World Factbook, 2018). We observed that only five movies used Kurdish in addition to other languages. Together, these findings support Phillipson (Reference Phillipson2008), who warned about the predominance of English at the expense of other languages and pointed out that ‘our choices can either serve to maintain diversity, biological, cultural, and linguistic or to eliminate it, and current trends are alarming’ (p. 264).

Our findings make contributions to methods employed to investigate the use of English in daily life. Most corpus research relevant to the global spread of English focus on linguistic features, which is a criticism voiced by Bolton (Reference Bolton2005), Pennycook (Reference Pennycook2001), and others. It might be true that, so far, most corpus-based research has focused on linguistic features and linguistic analysis; however, nothing inherently limits corpus research to linguistic analysis alone. This study is one way of using corpus research to investigate the role and status of English. In our previous and ongoing research, we investigated the role of English in higher education, movies, and job advertisements, using corpus tools and publicly available data. Needless to say, these are not the only potential uses of corpus research in world Englishes. For example, corpus research and corpus tools can be used to design pedagogical materials that reflect varieties of English, to analyze educational data that governments and other agencies publish online about language policy for different countries and contexts, and to compare varieties of English linguistically. Researchers interested in the spread of English may find the collection and processing of big data afforded by corpus research to be very helpful in many research areas, especially considering how extensive and far-reaching English is around the world. We need larger and comparative data which will allow us to use inferential statistics. Therefore, we are continuing to collect data for the years 2015–2018 to observe trajectories over time. In the future, we plan to collect data on other expanding circle countries to identify commonalities and differences, if any, between expanding circle countries. Future research will investigate the languages of movies from other years, language-related attitudes toward international movies, and the spread of English in other domains of life in Turkey.

BERIL T. ARIK is an applied linguist whose main research interests include second-language writing, world Englishes, and corpus linguistics. She received her PhD in Second Language Studies / English as a Second Language from Purdue University. She has worked at Purdue University as a lecturer teaching language and culture classes to international students and a visiting assistant professor teaching graduate courses such as qualitative, quantitative, corpus research and identity. Email: beriltez@gmail.com

BERIL T. ARIK is an applied linguist whose main research interests include second-language writing, world Englishes, and corpus linguistics. She received her PhD in Second Language Studies / English as a Second Language from Purdue University. She has worked at Purdue University as a lecturer teaching language and culture classes to international students and a visiting assistant professor teaching graduate courses such as qualitative, quantitative, corpus research and identity. Email: beriltez@gmail.com

ENGIN ARIK is a linguist and psychologist whose main research interests include basic linguistic and applied linguistic research in several signed and spoken languages. He received his PhD in Linguistics from Purdue University. He has worked at Purdue University and several universities in Istanbul, Turkey, teaching academic writing, research methods, introduction to psychology and linguistics, and language and cognition. In his research, he uses computational, corpus, and experimental methods. Email: enginarik@enginarik.com

ENGIN ARIK is a linguist and psychologist whose main research interests include basic linguistic and applied linguistic research in several signed and spoken languages. He received his PhD in Linguistics from Purdue University. He has worked at Purdue University and several universities in Istanbul, Turkey, teaching academic writing, research methods, introduction to psychology and linguistics, and language and cognition. In his research, he uses computational, corpus, and experimental methods. Email: enginarik@enginarik.com