Friederike “Friedl” Dicker-Brandeis (1898‒1944) was born into a Jewish family of modest means in Vienna at a time when the city was considered the crucible of modernity, with Sigmund Freud, Arnold Schoenberg, and other paradigm changers making their discoveries. Dicker was able to absorb aspects of Vienna's interdisciplinarity at a very early age.Footnote 1 Before she was twenty, she had taken courses at several art schools, joined a theater troupe, designed furnishings, and studied composition with Schoenberg. After becoming a Bauhaus-trained multimedia artist, she returned to Vienna to work during the interwar years, when she experienced the negative consequences of its “ambivalent modernism.”Footnote 2 As part of a generation that witnessed the city's art institutions unravel well before the Anschluss, Dicker stands out from the Vienna crowd for her overtly political art and heroic resistance to Nazism. She created Dadaistic posters to warn of fascism and painted and collaged a series of self-portraits after she was interrogated and imprisoned in Vienna in 1934. Her legacy materials include designs for furniture, theater sets, interior architecture, and some 4,300 children's drawings and collages, the result of her masterful teaching at Terezín. Using Bauhaus methods, she created an uplifting environment for the interned children—a story so inspiring that it has eclipsed her own work.Footnote 3 The drawings and collages of dreams, wishes, and memories of children who were facing great peril are now on display at the Prague Jewish Museum in “Friedl's Cabinet,” an upstairs room in a synagogue. The children's drawings could easily have been consigned to the rubble of history. But before Dicker-Brandeis boarded her 1944 transport to Auschwitz, she packed two suitcases with art by the children she had taught. She gave them to Willy Groag, the director of the dormitory, who hid them in the attic. He gave the suitcases to the Prague Jewish Community in August 1945: “I did it . . . despite the fact that the prospective receivers did not show too much interest in them. More than ten years later I was surprised to discover that the ‘not so much desired’ suitcases had become ‘the diamonds in the crown’—the exhibition of the children's drawings from Ghetto Theresienstadt and the book I Never Saw Another Butterfly turned out to be a world-wide success.”Footnote 4 Yet compared to better-known artists like Otto Dix and Georg Grosz, or even Oskar Kokoschka, Dicker-Brandeis's heroic deeds in Vienna's political underground have gone unsung, her remarkable body of work underappreciated and in some instances unassessed. Dicker-Brandeis is now receiving more sustained attention in edited volumes, theses, and group exhibitions.Footnote 5 But because she has been subject to neglect for so long, as were many women artists of her generation, our histories of the period are incomplete in significant ways. The reasons for her neglect include the gendering of modernism, the dispersal and loss of her works as she was forced into exile and then murdered at Auschwitz, the well-known reluctance to deal with the past in Austria, and a focus in scholarship on Weimar over Vienna and Prague.

In addition to the erasures that came from being a woman and Jewish, Dicker-Brandeis's interdisciplinary, allegorical, and multimedial work did not benefit from the historiographic tendency to value the separation of media in histories of twentieth-century art. For U.S. art historians especially, the long-lasting dominance of Clement Greenberg's ideas in the academy are obvious reasons why the intermedial aspects of Vienna 1900 and the Bauhaus have not been central features in prior narratives of modern art. In his 1960 essay “Modernist Painting,” for example, Greenberg outlines a selective history of modernist painting in which the separation of media was the foundation for purity and the pursuit of excellence (self-criticism in the Kantian sense).Footnote 6 Juliet Koss reports that in Europe a reluctance to look closely at Richard Wagner, too closely associated with the enthusiasm of Hitler, meant that Wagner's ideas were set aside and therefore often misunderstood.Footnote 7 The bringing together of sound, narrative, movement, theater, architecture, painting, and sculpture as theorized and practiced both at the Bauhaus and in Vienna 1900 was therefore often overlooked, or cordoned off into a separate history of design and architecture.

The breathtaking scope of Dicker-Brandeis's work bridges the perceived divide between the utopianist and politically disruptive attitudes of competing avant-gardes during the interwar years. She designed collapsible furniture, textiles, toys, purses, and interiors, and also worked in the idioms of New Objectivity, Dada, and allegorical magic realism. For a brief period late in her life, Dicker-Brandeis turned toward a Degas-like realism in a series of pastels and created completely abstract paintings with mixed media and found objects (Figures 1 and 2). One the one hand, she embraced narrative and allegory or reworked the Old Masters in unexpected realms. Oil painting, gouache, metal work, embroidery, photomontage, painted paper collage, wood, and found objects were among her chosen media. On the other hand, she was closely allied with key figures of the avant-garde, among them Johannes Itten, Paul Klee, Oscar Schlemmer, and Berthold Brecht. Dicker-Brandeis's intermedial recombinatory approach to subject matter and materials often broke with genre conventions: ridged typewriter keys appear on a painting of an interrogation scene; an ecclesiastical subject is rendered as a hinged sculpture in the idiom of the Bauhaus machine aesthetic; and her spray ink and gouache painting of a dream looks like a Moholy-Nagy photogram, an avant-garde process in which objects were placed on photo paper and exposed to light. Using ink and paint instead of light exposure, Dicker-Brandeis merges silhouetted figures, nebulous shadows, and sharply defined abstract lines and shapes in a haunting dreamscape (Dream, 1934‒38, Jewish Museum, Prague). Dicker-Brandeis's unique ars combinatoria—the Old Master in a machine aesthetic, the found object on a painting, the allegory in the surreal, the painting as photogram—developed a “why not” approach to combining any genre, medium, and subject matter.Footnote 8 Understood against the backdrop of twentieth-century modernisms and their revisions, the trajectory of Dicker-Brandeis's career appears to be far more than just the creativity of an artist moving through a turbulent twentieth century. Crucially, Dicker-Brandeis's intermedial attitude allowed her to pursue both utopianist and critical approaches to art, which read against the grain of common narratives of modernism, in which competing avant-gardes aligned themselves with either a disruptive (Dadaism and Surrealism) or constructive (Purism or De Stijl) postwar attitude.Footnote 9 Not only did she participate in the utopianist reconstruction of the Bauhaus and the political critiques of Dadaists, her political posters commemorating the fallen after the 1919 counterrevolution provide an example of a lesser-known tendency to fight fascism in the context of the Bauhaus.Footnote 10 In Vienna, where Dadaism was hardly known, her work in the underground and Dadaistic posters speak to the transnational inflections of vernacular modernism.

FIGURE 1: Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, Pavel and Maria Brandeis, 1939. Pastel on paper, 46 × 62 cm. Private collection. Scan: Visual Resource Center, UTSA.

FIGURE 2: Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, A Negative and a Positive Form of a Force Field, 1941. Wood, wire, gouache, 43 × 48 cm. Photo: University of Applied Arts, Vienna, Collections and Archive.

Situated against the received stylistic terms of the first half of the twentieth century, Dicker-Brandeis's oeuvre presents an unusual trajectory that hardly follows a linear progression toward a signature style, from a figurative approach to the discoveries of abstraction, for example. Furthermore, her body of work does not fit into the better-known templates of twentieth-century modernisms, where becoming visible meant developing a style associated with a movement, as Mondrian did with de Stijl and countless other artists associated with modernism have done.Footnote 11 As Dicker-Brandeis moved between the art centers of Vienna, Berlin, and Prague, she interpreted and reinvented techniques and ideas from the major art movements of the interwar years, ultimately leaving behind a body of work so diverse that its very comprehension requires a new metaphor. “Network” is the most apposite term. Though often used in media studies for its technical connotations and immediate associations with the Internet, the form also refers to old media, as in a web or net, and aids in visualizing infrastructure or dynamic potential. To describe the advent of globalization in the seventeenth century, for instance, Timothy Brook has used the metaphor of Indra's net, a web with a pearl at each connection of threads, reflecting all other pearls on its surface. In network theory as in Brook's use of the Buddhist tale, the metaphor makes visible the interconnectedness of all things: when one node changes, all others change.Footnote 12 As a way of visualizing a fluid, multidirectional framework for interaction, exchange, mirroring, and transformation, the network metaphor is also apt for describing the rich artistic practice of Dicker-Brandeis. At the same time, Dicker-Brandeis's unique recombinatory approach to the contemporary—characterized by an unusual breadth of subject matter, technique, political engagement, and collaborative partnerships and teaching—necessitates the further use of many verbs. She reflects, absorbs, integrates, transmits, teaches, and collaborates with other artists. Though certainly a central node of connections and reflections, in both her biography and in her aesthetic production, Dicker-Brandeis also highlights the significance of making and maintaining connections among networked nodes. As she worked through and with different styles and media, she performed her own ars combinatoria of technique, style, and subject matter, mixing categories and genres into hybrid interpretations of twentieth-century art movements. Instead of a linear trajectory toward a singular style, her aesthetic practice was based on interconnectivity, receptivity, change, remediation, and cross-pollination. This unusual interdisciplinarity, though rooted in the aesthetics of Vienna 1900, updating Old Masters and allegorizing Christian themes, would develop throughout her short life through a combination of genres, materials, media, and allegorical subject matter in unforeseen ways.

The network metaphor has also been crucial for rethinking the role of women in the creativity of Vienna 1900 and beyond, insofar as it suggests a far richer landscape of possibilities yet to be written. According to Moritz Csáky's hybrid model of Viennese modernism, which was more inclusive of women and the interwar years than either Carl E. Schorske's generational model or Steven Beller's thesis that Jews were primarily responsible for Vienna's creativity, “mehrfachidentitäten” (a sense of multiple, hybrid identities) was the norm.Footnote 13 In addition to highlighting the role that hybrid identities played in Vienna's creativity, Csáky called attention to another typical factor: mobility. Many of Vienna's most famous intellectuals came from the far-flung crown lands of the Habsburg Empire. If the capital attracted talent in the first part of the twentieth century, war or political constrictions drove them out, and then sometimes back in again. Csáky's model provides a productive framework for retroactively understanding the role that highly mobile multicultural participants played in Vienna's creativity. It was the norm for women artists like Dicker-Brandeis to travel for the purpose of study both before and after World War I.Footnote 14 Furthermore, Csáky's insistence on hybrid identities and mobility as characteristics of the Habsburg Empire can shift Dicker-Brandeis from the margins to the center of attention for her lifelong movement between cities in both “chosen and forced paths.”Footnote 15 While the visual arts in Vienna are too often perceived as a static, isolated world that ended with the monarchy and the deaths of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, Csáky's more inclusive model provides a more dynamic account of the city as a mobilized network of active participants who continued an engagement with the avant-garde movements of the twentieth century.Footnote 16

Unlike many other young women of her generation, Friederike Dicker grew up relatively unsupervised.Footnote 17 Her mother died in 1902, when Friedl was still just three, and her father, a clerk in a paper goods store, could not afford a nanny or other childcare. He brought her along to the shop, where she used paper and colored pencils to create her own world. Her independent spirit and ingenuity gave her some unexpected freedoms in Vienna, where she developed ways to experience world-class art and music without the usual expenses: she would sneak into the opera by hiding behind the stage curtains, examine reproductions in bookshops, admire the décor of coffee shops, and visit the Kunsthistorisches Museum, all without tickets. She lived in the ninth district, where she attended the Bürgerschule from 1909 to 1912.Footnote 18 By the time she was seventeen, Dicker had already earned a degree in photography at the School of Graphic and Experimental Art with the financial support of her father. She then enrolled in Rosalia Rothansl's textile course at the School of Applied Arts against his wishes. She earned tuition money by working as a prop master, costume maker, and performer in small roles for a theater company.Footnote 19 While at the School of Applied Arts, she enrolled in a design foundations course (Ornamentale Formenlehre) with Franz Cizek, known for his innovative children's course and papercutting methods, which he also used in his courses for adults.Footnote 20 In an anecdote that is telling for how much freedom she had compared to other young women in Vienna 1900, she brought a classmate from Cizek's class, Gisela Jäger-Stein, to the Prater, where they waded without shoes and stockings in the Praterauen, which for Jäger-Stein was a “revolutionary Neuheit.”Footnote 21 In pursuit of this path, Dicker also enrolled in Johannes Itten's experimental private school shortly after it opened in October 1916, and would have started with yogic breathing exercises and rhythmic drawing studies. Impressed with Itten's general adaptation of eastern philosophy, Dicker was particularly taken with the notions of the inseparability of life and art, the possibility of spiritual progress, and the importance of breathing for determining the entire rhythm of life. Because Itten placed no restrictions on student individuality, providing a mere link between word, sound, form, color, and movement for them to discover for themselves, Dicker spent her evenings in concert halls and especially loved Mahler, Stravinsky, and Schoenberg, with whom she studied composition from October 1918 to June 1919.Footnote 22 At a young age, Dicker had already absorbed the sensory lessons of Vienna 1900—the city as Gesamtkunstwerk.

Utopianism

In 1918 Dicker began a romantic and design partnership with Franz Singer (1896‒1954), another student in Itten's experimental school. As a utopian response to the devastation of World War I, Dicker and Singer designed furniture and living environments, which may at first seem naïve unless compared with Walter Gropius's rationale for the creation of the Bauhaus, a utopian art school with the aim of harnessing the destructive power of machines and creating better environments:

We find ourselves in a colossal catastrophe of world history, in a transformation of the whole of life and the whole of inner man . . . a universally great, enduring, spiritual-religious idea will rise again, which finally must find its crystalline expression in a great Gesamtkunstwerk. And this great total work of art, this cathedral of the future, will then shine with its abundance of light into the smallest objects of everyday life. . . . We will not live to see the day, but we are, and this I firmly believe, the precursors and first instruments of such a new, universal idea.Footnote 23

Although Gropius disagreed with Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg, and other participants in this utopian strain of twentieth-century modernism, they generally shared a belief that they could reconstruct a new international world and that good design would improve mankind. Gropius's idea for the Bauhaus was to hire great artists to work side by side with master craftspeople. Paul Klee, for instance, could be a form master in the weaving or glass workshops without having studied weaving and could also teach the preliminary required course. In the workshops, students were to learn by doing. Oskar Schlemmer shared Itten's concept that the fine arts were to be applied to architecture, which inherently included movement, theater, and sound. The most important premise was that there should be a total integration of the arts, a Gesamtkunstwerk with a spiritual dimension that connected movement and corporeality to art.

Dicker and Singer were among a group of twenty-five students who followed Itten from his experimental school in Vienna to his new position at the Bauhaus, where they could pursue their shared ideals on a much larger stage.Footnote 24 Further traces of this distinct connection between Vienna and the early years of the Bauhaus could be followed through Dicker and the Itten circle, which included Sofie Korner (1879‒1942), Anny Wottitz (1900‒45), and other women artists. Together they created a new synergy that carried many of the interdisciplinary interests of Vienna with them.

Based primarily on aesthetic observations, Vienna 1900 scholar Jane Kallir argued in 1986 that the intermedial, interdisciplinary modernism of Vienna 1900 was a fertile source of the multidisciplinary nature of the Bauhaus, where architecture, theater, dance, kineticism, and intermedia were the norm. The multimedial concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk had been created for the stage, but in Vienna it also “entered the home, and the home, as a result, became a stage,” according to Kallir, who draws a direct line from Ringstrasse pageantry to the Wiener Werkstaette integration of arts in spatial design and a “‘final flowering’ in the Bauhaus project, whose goal was [in Walter Gropius's words] ‘to bring together all creative effort into one whole, to reunify all disciplines of practical art—sculpture, painting, handicrafts and the crafts—as inseparable components of a new architecture. The ultimate, if distant, aim of the Bauhaus is the unified work of art—the great structure—in which there is no distinction between monumental and decorative art.’”Footnote 25 Such obvious links between Vienna 1900 and the Bauhaus 1919 have been minimized in the dominant accounts and surveys of twentieth-century art, which have prioritized purity and the separation of media, rather than their combination. The better-known accounts of connections between Vienna and Weimar that do exist have furthermore focused on founding fathers like Gropius and Itten, minimizing the role of women at the Bauhaus and overlooking potential connections to other cities of modernism in Central Europe.Footnote 26 Despite Bauhaus historian Marcel Franciscono's caution that there were “complex and multifarious” sources for the Bauhaus preliminary course, and his interest in the parallels between Cizek and Itten as early as 1971,Footnote 27 Rainer Wick noted in 2009 that Vienna is rarely brought into consideration, although it arguably functioned as a “proto-Bauhaus”: the teaching principles at the School of Applied Arts under Alfred Roller's direction (from 1909), for example, already contained many of the Bauhaus dictates, such as the focus on the material study of paper, textiles, wood, and stone, to know the qualities of what materials allow and express.Footnote 28 Itten's project to disencumber students of prior learning, to free their creative imaginations, and to focus on movement were just a few of the precepts that he held in common with Cizek.Footnote 29 Wick has sought links and direct connections between Itten and Cizek to prove influence or transfer, but has found none that he finds definitive in the documentation.Footnote 30 Along these lines, Rolf Laven pinpointed a male student shared by Cizek and Itten as a potential link, a fruitful line of inquiry that should include Dicker.Footnote 31

A Bauhaus insider from the start, Dicker completed the preliminary course in her first semester and was nominated by the Master's Council to become the first student to teach in the “Vorkurs” as Itten fine-tuned his “scientific–mystical” teaching system based on contrasts in form, shape, color, texture, and light and dark. Dicker was more prepared than other students for life at the Bauhaus, not only as an alumna of Itten's experimental school in Vienna but as one with experience in costume and prop making, theater, music composition, paper cutting, weaving, printmaking, photography, drawing, and painting. Although she taught in the preliminary course, Dicker is rarely mentioned as a Bauhaus teacher, much less a “founder.” While gender certainly played a role in this oversight, as did her youth and official role as a student, Dicker's omission from Bauhaus history was exacerbated further by long-standing models of creativity. Once again, the network metaphor might help broaden the definition of authorship and source material and provide a more inclusive and more accurate picture of contributions beyond the production of an artwork. The Bauhaus was designed to create a community of teachers and students by having them live together and host events, festivals, and parades in Weimar, Germany. Dicker most certainly participated in events like the kite festival, in which artists paraded kites through town and then flew them. She also had a popular booth with puppet shows at the Weimar market and created posters for various musical evenings, including one for the first Bauhaus evening of readings by Else Lasker-Schüler.Footnote 32 Itten, who was always more of a brilliant teacher than a great artist in his own right, would call the Vienna group his “Grundstock,” the crucial foundation for students to find a way forward at the Bauhaus. When it came time to create a lesson plan, which was published in Utopia (Figure 3), he naturally enlisted the more talented Dicker. The 1921 typeset collage, a study plan for analyzing Old Masters, instructs students to connect the movement of drawing to rhythm, so as to incorporate the spirit of the work into their own practice, drawing on Itten's concept of “Bewegung” (movement) as a foundation for life and art. Dicker's handwriting is recognizable in the corrections: “You experience the work of art, it is reborn in you.”Footnote 33 The collage uses bold lettering and colorful typefaces to create rhythm, volume, and a sense of sound. Sound and movement were connected in practice: later in life, Dicker-Brandeis would give sonorous dictations to her students at Terezín, just as Itten had done at the Bauhaus. Her student Edith Kramer described the process by which they created lines and movements on the page as a real-time response to the sound of her voice.Footnote 34

FIGURE 3: Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, draft for an untitled typeset collage of a text by Johannes Itten, “Analyses of Old Masters,” sheet 10, which appeared in Utopia: Documents of Reality (Utopia: Dokumente der Wirklichkeit), ed. Bruno Maria Adler, Weimar, 1921. Correction sheet, letterpress with collage and pencil, 32.4 × 24 cm., Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin. Scan: Visual Resource Center, UTSA.

Gender Issues at the Bauhaus

According to Anja Baumhoff, a special “women's class” was formed in 1920, when Gropius began to limit the number of female students and then to channel them into textile, ceramics, and bookbinding workshops in a “hidden agenda.”Footnote 35 Dicker was considered one of the most talented students, even in that biased environment. She received a rare scholarship and relief from student fees during part of her time there and was mentioned as a “most gifted” student they did not want to lose in 1921; at the suggestion of Gropius, the Masters agreed to pay a high price (2,000 Marks) for a rug that she wanted to sell, making an exception to the rule that required student work to be sold to the Bauhaus for a fixed price.Footnote 36 Gropius later wrote, “Miss Dicker studied at the State Bauhaus from June 1919 to September 1923. She was distinguished by her rare, unusual artistic gifts; her work constantly attracted attention. The multifaceted nature of her gifts and her unbelievable energy made her one of the best students so that already in her first year she began to teach the beginners. As the former director and founder of the Bauhaus, I follow with great interest the successful progress of Miss Dicker.”Footnote 37 In a separate study, Baumhof examined gender roles in Itten's all-encompassing art theories, but Dicker, who had already been exposed to the progressive youth movement in Vienna when she was seventeen, did not subscribe to these in Charlotte Zwiauer's estimation.Footnote 38 Rather than taking Baumhoff's groundbreaking institutional analysis for the whole story, Elizabeth Otto and Patrick Rössler propose that following the individual paths of women artists has resulted in a more nuanced view.Footnote 39 Dicker, for example, took courses in most of the Bauhaus workshops, studying with Itten, Georg Muche, Lyonel Feininger, Paul Klee, and Oskar Schlemmer. In the metal workshop her inventive approach to subject matter and new materials is already evident.Footnote 40 She combined the new machine aesthetic with the unlikely biblical subject of Anne and Joachim, who miraculously had a child late in life, namely, Mary, the mother of Jesus (Figure 4). Leonardo da Vinci offers a prototype for the scene: as an adult Mary sits on the lap of her mother Anne, she leans over to restrain the Christ child, who holds a lamb.Footnote 41 In Dicker's 1921 sculpture, the three figures fit together like nesting dolls, with tubular arms and interlocking legs. The back figure is nickel, the middle figure iron black. The floating figure, an angel without wings, is in red lacquer, the same material as the smallest figure in the nesting set, Christ. Hans Hildebrandt described the now lost work as a “hinged constructive sculpture”:

Anna Selbdritt was made by Friedl Dicker, who was among the most variably and originally gifted women of our time. Conceivably installed only in the most modern of buildings, it fits in with the architecture so organically that it appears to be part of it. The selected fabric, nickel, black iron, brass, glass, and white and red paint differentiate themselves just as much from traditional [materials] as the design of human bodies out of pipes, balls, and cones does from what has, until now, been usual. The harmlessness of female nature—that, once radicalized, throws all restraint aside—comes completely to life in this sculpture, which is much more than an interesting experiment.Footnote 42

In this work, Dicker channels her knowledge of Old Masters, gleaned first hand from visiting the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, and personal experiences of maternal longing, a theme of the intergenerational story of miraculous babies, surprises for both an aged mother and her virgin daughter.Footnote 43 Over her long-term relationship with Singer, she became pregnant more than once and each time wanted to keep the baby, but he pressured her to abort. She complied, although she longed to be a mother. On 17 March 1921 Singer married soprano Emmy Heim (1885‒1954), an older woman whom he knew from Vienna; their son was born four days after the wedding.Footnote 44 Dicker was despondent, but found solace in her art, writing to her friend Anny Wottitz of her “fear of loneliness, utter loneliness” but including this advice: “anxiety is extinguished by work—it is a sort of flight from inner turmoil.”Footnote 45 With Anna Selbdritt, Dicker interprets the emotional content of the biblical story as formal shapes of tubes and cylinders, nesting, interlocking, and unlocking while capturing the restrictions and protectiveness of motherhood, described by Otto and Rössler as a “purified vision of mystical love and self-sacrifice.”Footnote 46 In essence, Dicker collaged traditional subject matter with the applied arts, creating a mechanical Madonna for the twentieth century, to exist not in a church but in a domestic setting as part of an architectural interior design.Footnote 47 Categories of site, genre, medium, and function are all rethought and recombined in this work.

FIGURE 4: Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (Anna Selbdritt), 1921, metal sculpture (not preserved), glass, fabric, nickel, iron, brass, paint. 240 cm. high, in: Hans Hildebrandt, Die Frau als Künstlerin, Berlin, 1928. Scan: Visual Resource Center, UTSA.

During the year that Dicker was reworking the theme of Anna Selbdritt, which she did in several media, Klee arrived at the Bauhaus. A power struggle was already underway between Itten and Gropius, between the “spiritual” and the “rational” factions within the school. Klee played the role of sage observer and helped redirect some of the Itten students by creating a third outlet for their enthusiasm when he began teaching in 1921. Dicker was one of them, studying with Klee almost daily.Footnote 48 He soon became her favorite teacher and remained a lifelong source of inspiration. In her 1925 wall hanging, made after she left the Bauhaus, there is a unique focus on playful lines rather than the more typical color shapes of the Bauhaus weavers. An unexpected wit is at play again, as Dicker translates Klee's famous dictum “a line is a dot going for a walk” into the lines of the yarn weaving and stepping through the lines of the warp and weft of a loom (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5: Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, wall hanging, gift to Hanne Deutsch, b. 1931, married name Sonquist, 1925. Fabric, 90 × 155 cm. Private collection. Scan: Visual Resource Center, UTSA.

Despite her allegiance to Klee, Dicker remained closely associated with the Itten group and therefore left during the famous early split at the Bauhaus in 1923. By December 1920 Gropius had already perceived the Itten group, which he alternately called the “Singer-Adler” faction or the “spiritual Jewish” faction, as a distinct unit within the Bauhaus. Fearing a takeover, he remarked in a private letter to Lily Hildebrandt that this group would have to leave for peace to reign at the Bauhaus, claiming that the “spiritual Jewish” faction had become too large and was trying to take over the Bauhaus, creating a conflict with “Aryans.”Footnote 49 Gropius also feared the consequences of students or anyone affiliated with the Bauhaus getting involved in local politics. Dicker was among a group of students who received a warning from the Masters’ Council (Meisterrat) in 1920 because they had used Bauhaus facilities to create political posters to commemorate the burial of fallen workers in the “Gegenrevolution,” or counterrevolution, in December 1919.Footnote 50 Gropius was also concerned about the future of the Bauhaus if it did not connect to forms of industry, worrying that the Bauhaus could become an “island of loners” if it did not connect to the outside world: “I search for union in the connections, not in the separation of these life forms.”Footnote 51 These disputes were not only about aesthetics but also about food, lifestyle, and control over the institution. At the center of it all was Itten, who taught more students than anyone and had convinced Gropius early on that the preliminary, six-month course should be a prerequisite for all other courses. Gropius blamed the students who had followed Itten from Vienna for influencing their teacher, who had taken over the admission process. Itten's philosophy of art was all-encompassing. He intensified his involvement with Mazdaznan, a sect without a deity that emphasized self-purification through yogic breath and movement, fasts, purging, and a strict vegetarian diet. The canteen at the Bauhaus served only Mazdaznan food, which consisted of pureed vegetables and garlic. Students who did not want to eat the canteen's offerings had to get regular barley soup under the table, so to speak. For purification fasts, students would spend weeks in the Bauhaus garden consuming only hot juices made from berries and fruits. They were discouraged from saying anything negative and some shaved their heads and wore robes in emulation of Itten.Footnote 52 In December 1921, Klee wrote a text for the Bauhaus prospectus: “I welcome the fact that forces so differently oriented are working together in our Bauhaus. I also approve the conflict between these forces if its effect is evidenced in the final accomplishment. To meet an obstacle is a good test of strength for every force,—provided it is an obstacle of objective nature.”Footnote 53 Even a sage bystander like Klee was unable to resolve the tensions. The perceived rift between Gropius's more design-oriented group and Itten's more spiritually oriented students led to the latter's departure from the Bauhaus in 1923.Footnote 54 Dicker was an integral part of this group, as Itten's student, Singer's partner, and a teacher at the institution. Despite such conflicting loyalties, she remained on good terms with Gropius. Letters of recommendation from both Gropius and Itten demonstrate their admiration for her as an artist and teacher.Footnote 55

Multiple Studios in Berlin and Vienna

Despite her personal heartbreak, Dicker continued her design partnership and friendship with Singer. In what seems in retrospect like a dizzying itinerary, she often had more than one studio and more than one design partnership in more than one city at a time. There are letters from her about suitcases and trying to manage messages about clients from afar.Footnote 56 What was Dicker's motive for branching out in so many directions in the 1920s? Was it the changing political circumstances in Berlin, which would eventually send her back to Vienna and then on to Prague in 1934? Was it to help her friends succeed in the design business? To find occasional space away from the unhappy romantic partnership with Singer? To acquire more clients in a time of inflation and economic duress? Whether any of these were Dicker's exact motives, they all were the likely effects of her schedule. From 1923 to 1925 Singer was Dicker's design and business partner in Berlin, where they founded the Workshops for Visual Arts LLC (Werkstätten Bildender Kunst G.M.B.H.), which produced interiors, stage sets, and handmade objects. The 1925 wooden toy set Phantasus was a prototype for a Tinkertoy-like building set that allowed children to create animals, such as giraffes, elephants, or rabbits, with movable parts and wheels. Meant to stimulate children's creativity, the parts were basic and simple, allowing for endless possibilities.Footnote 57 They also sold tapestries, toys, embroideries, books, and lithographs produced by other Bauhaus alumni through their business, which they titled “Bauhaus (Weimar) Berlin Branch/Bauhaus Weimar Zweighaus Berlin.” In 1923 Dicker opened a workshop in Vienna with Anny Moller Wottitz, her lifelong friend and fellow Bauhaus student with whom she had studied and collaborated in Vienna and Berlin.Footnote 58 During this time, she began to intensify her work for the theater in the Berlin studio, and, with Singer, created stage sets and costumes first for Berthold Viertel's theater troupe, then for Berthold Brecht.Footnote 59 In 1925 Dicker opened a second studio at Wasserburggasse 2 in the ninth district in Vienna with Martha Döberl. Singer, who already had his own atelier in Vienna (from 1925) soon joined design forces with her again at the Wasserburggasse studio. The architectural design firm “Atelier Singer-Dicker” would last until the early 1930s, when Dicker opened her own atelier in the nineteenth district.Footnote 60 The firm was successful, with numerous commissions to design new buildings, rebuild or redesign interiors, and create furniture and textiles. Their stated mission was to create furniture to solve social problems of space, not just for the middle class but also for the working class.Footnote 61 Clients included private patrons and businesses. Their first big commission was to design a tennis clubhouse for Dr. Hans Hellmer.Footnote 62 For Friedrich Achleitner, the duo connected to the works of Friedrich Kiesler, which were obsessed with space: “the secret of these works appears to lie in the fact that all of these elements are melted into an original, inseparable whole . . . [that can function] in poverty or luxurious circumstances.”Footnote 63 Because of her political engagement as a Communist the Singer-Dicker firm was able to get many commissions from Red Vienna.Footnote 64 The pair designed a Montessori kindergarten and other interiors with modular and collapsible furniture, as precursors to the better-known Charles and Ray Eames of U.S. furniture design. Hedy Schwarz, the director of the kindergarten, compiled a photo album showing the kindergarten and its multifunctional furniture in use. The children performed daily activities by themselves, such as preparing food and setting the table for lunch.Footnote 65 Singer and Dicker tried to get manufacturing contracts for their prototypes, such as a stackable chair and a foldable sleeping sofa, but circumstances were less favorable than in the postwar United States. They were among the very few directly Bauhaus-trained designer/artists in Vienna. While Singer was often the named or credited designer of the architecture, the two had the same education and evidence shows that they worked interchangeably.Footnote 66

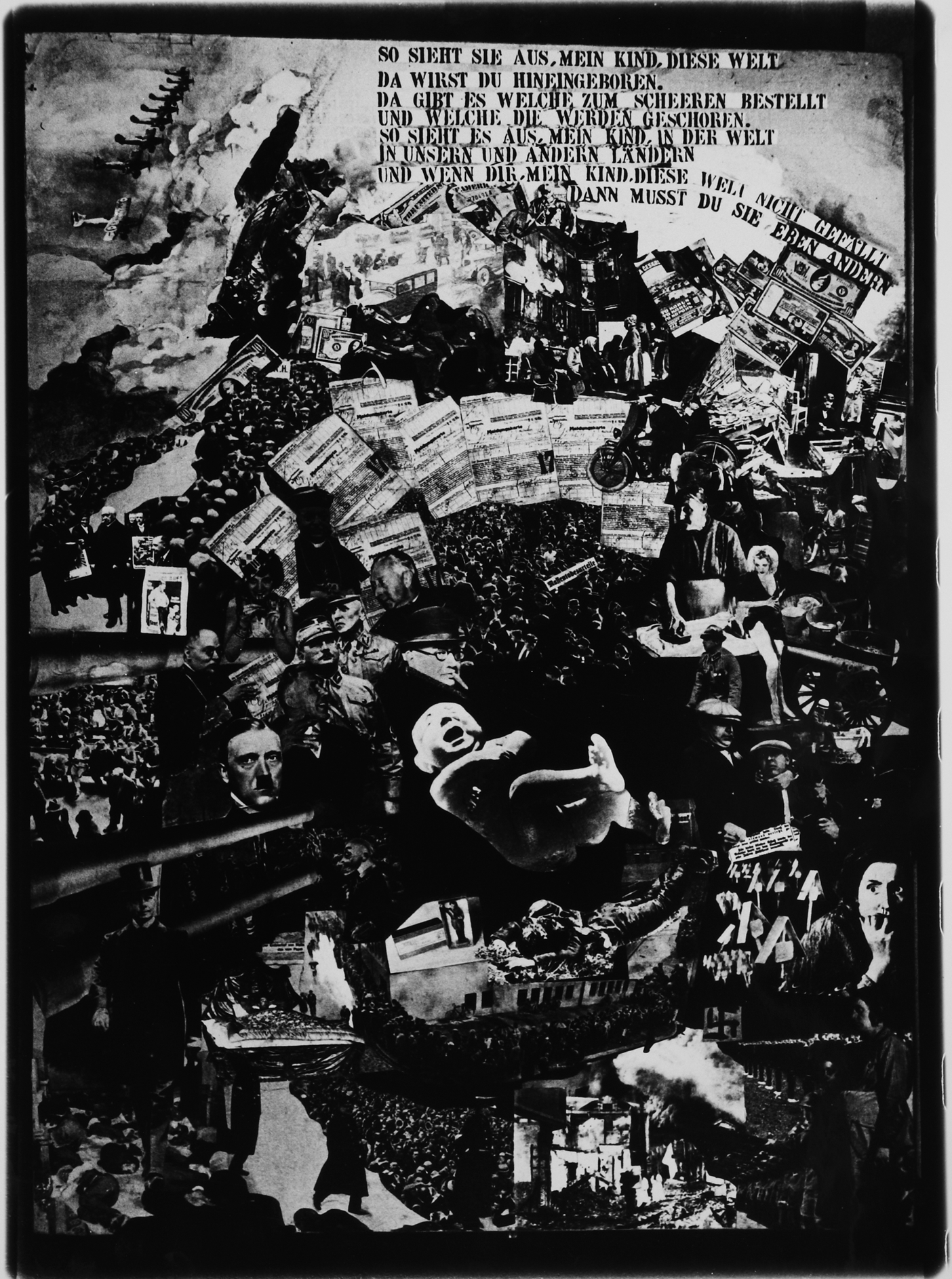

In the 1930s Dicker continued to bridge the political divide between the utopian, internationalist, and reconstructive “call to order,” on the one hand, and the disruptive cultural critiques of many Dadaists, Surrealists, and New Objectivity artists, on the other.Footnote 67 In the context of Vienna she was doubly unique: not only as one of the few Bauhaus-trained designers but also as a disruptor using the little-known idiom of Dadaism.Footnote 68 As Dicker continued to design furniture for a new world, including the kindergarten in Red Vienna, she also created politically disruptive, antifascist posters. She warned people of the political dangers on the horizon in a series of Dadaistic posters with titles like The Middle Class Turns Fascist (Das Bürgertum faschisiert sich, 1932‒33) and That's the Way of the World, My Child (So sieht sie aus, Mein Kind, 1932‒33; Figure 6).Footnote 69 In the latter work, a dizzying array of figures swirl around a crying infant. Photographs excerpted from contemporary media, spliced together to depict the “real” in the language of photomontage, include Hitler, recognizable military officers, guns, currency, wealthy top-hatted men carrying briefcases, cardinals, movie stars, and worried-looking women who are pregnant or working. The poem addresses children, advising them to change the world they were born into, and uncannily foretells what will happen to Dicker: there are those who are to shear and those who will be shorn.Footnote 70 The poem was thought to be by Berthold Brecht until recently, but Angelika Romauch determined that the poem is probably Dicker's own.Footnote 71

FIGURE 6: Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, This Is How the World Looks, My Child (So sieht sie aus, mein Kind, diese Welt), 1932‒33. Photograph of photomontage and collage, 50.6 × 41.2 cm. Photo: Bildarchiv mumok, Vienna.

After 1933 members of the Austrian Communist Party had to go underground. Dicker's studio was searched after the 1934 February Civil War in Vienna, and she was accused of fabricating and hiding passports for political activists. She was brought in for questioning by the Vienna authorities, then imprisoned and repeatedly interrogated.Footnote 72 After her trial and release, she moved to Prague, where she painted a memory of the experience, titled Interrogation I, using a combination of New Objectivity distortions to show the “real”; a unique collage addition of wooden typewriter keys lends the work a documentary quality (Figures 7 and 8).Footnote 73 Unusually, however, she uses blank disks of wood instead of actual keys, adding a theme of absence, power, and sensory memory, and anticipating some of the themes and strategies of Rachel Whiteread's ghostly uniform inside-out library on the Judenplatz in Vienna, in which the books lose their identities and humanity. Allowing the painting's plywood base to show through as the interrogator's wooden hands underscores the machine-like and intimidating interrogation. Her hair is short, her ears are red, and the looming table and inquisitor are overwhelming; she gave up no names. An image of solitude facing malevolence, Interrogation I is also a memory of sound. The official recording of an interrogation is signaled by the relentless clacking of typewriter keys. Another visual signal of sound, as she later described them, were her red, “burning” ears. Interrogation I depicts the world as it is in the view of New Objectivity: using distortion and objects excerpted from the real world to show the reality of social relations.Footnote 74 In an undated letter Dicker-Brandeis explained her new painting style to her friend Hilde Kothny, which may refer to such images: “I no longer want to work allegorically, but instead want to express the world as it is, neither modern nor outdated. Although I love Picasso and Klee as passionately as before, I cannot use their means of expression.”Footnote 75 If Interrogation I uses the vocabulary of legibility, the distortion of form to communicate the reality of a social situation, it was never exhibited as such. In Prague she was not in a position to exhibit or publish her works as Berlin's Tendenzkünstler (New Objectivity artists) once did in Dada exhibitions. After she moved to Prague she made contacts with left-leaning immigrants and became involved in the antifascist bookshop group “Schwarze Rose,” but this was an underground operation.Footnote 76

FIGURE 7: Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, Interrogation I, 1934. Mixed media: oil, plywood and typewriter keys on canvas, 120 × 80 cm. Prague, Jewish Museum. Photo: author.

FIGURE 8: Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, Interrogation I, 1934 (detail). Mixed media: oil, plywood and typewriter keys on canvas, 120 × 80 cm. Prague, Jewish Museum. Photo: author.

Her second version, Interrogation II, leaves found objects and narrative detail behind to express lasting psychological trauma through paint alone (Figure 9). The illegibility of the image, the implied violence and emotion of a grotesque smearing of paint over a face, are a return to the language of Expression (Ausdruck), that is, the representation of the world as experienced from within, as in the category of the formless, the horror of boundary loss. By contrast, a collage from happier times juxtaposes a photograph of Dicker at work, drawing lines on the page (Figure 10). A witty mixed-media cover for a portfolio of drawings, it plays on abstraction, representation, and indexicality, updating a genre of the artist's self-portrait at work in the studio, a kind of meta-painting. Her hand, in the collaged image, holds a brush that turns into a gestural red flourish, the work in front of us.

FIGURE 9: Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, Interrogation II, 1934. Oil on canvas, 75 × 60 cm. Prague: Jewish Museum. Photo: author.

FIGURE 10: Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, untitled self-portrait on a cover for drawings (gift to Ella and Josef Deutsch), 1931. Photocollage and tempera, 70 × 50 cm. Private collection. Scan: Visual Resource Center, UTSA.

In another work on paper, which was related to the Interrogation series and perhaps a preliminary study for it, Dicker layers newspaper and painted papers (lush rose madder) in a subtly textured collage (Figure 11). Itten's students used such painted paper cutouts to play with composition because it was an efficient and effective way to make decisions without overpainting or losing the freshness of a color. Dutch Baroque flower painters had also used a similar process to compose their floral imagery, with cut-out paper flowers used in preliminary compositions, with an emphasis on mimesis. The process, made invisible by trompe l'oeil in seventeenth-century Dutch still lifes, is left marvelously visible in Dicker-Brandeis's richly textured image. It leaves traces of the artist's process, where lines of shapes can be seen that have been overpainted, and layers of found papers are visible. Paper cutting, as used by Henri Matisse, Kara Walker, or nineteenth-century silhouettists, employs scissors as a drawing or line-making tool that creates a deliberate contrast between light and dark, color and field. The technique, as Dicker used and taught, was connected further to the core theoretical principle of Itten's teaching at the Bauhaus: that Bewegung, or movement, is connected to life forms, and that gestures and bodily movements are connected to line. Dicker also uses the technique as collage—the word is French for “gluing” and highlights the rich layering of textures, newsprint, and painted, overlaid papers. Wick discusses the use of the term “paper cutting” as a possible Czechoslovakian mistranslation of “collage.”Footnote 77 However, some form of the term “paper cutting” is worth rescuing for its different emphasis on the activity of creating a line through cutting, which collage—and especially the aesthetic of Dadaistic photomontage—submerge in favor of the splicing together of disparate, preexisting images. Paper cuts can become lines, shapes, or merely texture in Dicker's collaged world. While John Heartfield's photo-montages were hyperlegible, conveying political messages from the relative safety of London, Dicker's late collages are more personal and ambiguous: Is it the face of the interrogator, her own face, or a mix of the interrogator's smirk and Dicker's ears, a remembered trauma of blurred senses? A delicately drawn ear over the rose-painted paper refers to the act of listening, as do Dicker's own red ears in Interrogation I (1934). The portrait head of a smirking character, whose eyes are big black holes and whose forehead consists of an arched eyebrow and a big brown shadow, conveys emotion, but not in a way that would be politically legible. Dicker could only paint for herself after moving to Prague and becoming part of a political underground. The process of cutting and collaging is something she almost certainly learned before Itten, with Cizek's class in Vienna, where paper cutting became not only part of the curriculum at the School of Applied Arts but was celebrated at the Kunstschau 1908 in a room devoted to art for and by children; the process became influential among artists of the Wiener Werkstätte and Secession.Footnote 78 The collage, the cut, and the reassemblage signal how she navigated genres and subject matter, an ars combinatoria of assembling disparate things into new creations. This creative attitude in turn connected to her interdisciplinarity, which was further supported at the Bauhaus in Weimar.

FIGURE 11: Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, Interrogation, 1934. Gouache, collage on brown cardboard, 46 × 33 cm. Photo: University of Applied Arts, Vienna, Collection and Archive.

Dicker-Brandeis's ability to reassemble and reimagine ordinary objects spilled over into a personal and performative aspect of her everyday life. As her friend Hilde Kothny recalled, “she had a lively temperament, always ready to joke. It was her peculiar gift to perceive the comedy in every situation. The last Christmas in Hronov, Friedl's behavior was quite unabashed. She had such a whimsical spirit that she cut the ‘precious’ tablecloths for our fancy dresses.” Still, there was an edge to Dicker-Brandeis's whimsy: “She was quite impossible to restrain. She sheared a spool of black thread, poked the thread under her nose to make Hitler's moustache, threw a strand of her hair onto her forehead, and, encouraged by our laughter, began to imitate by pantomime this crazy person's speech.”Footnote 79 With increasing restrictions against Jews, Dicker-Brandeis often had to move into increasingly smaller spaces, all of which she redesigned. She married Pavel Brandeis, a cousin, in Prague on 29 April 1936, and the two would be displaced several times during their short marriage. In 1938 they moved to the village of Hronov, close to the Polish border, where Pavel secured a job as a bookkeeper and Friedl as a weaving and textile designer, both at B. Spiegler and Sons. Each time they moved, Friedl would install a new cozy apartment with whatever was on hand, until they were living in one room that served all functions. Using her design skills to create a livable space, she would repurpose crates to make modular seating or build partitions to create rooms. Anna Sladkova, an artist in Hronov, described their home as “simple, naturally elegant, a perfect home of the twentieth century.”

I have never seen one like it, neither before nor afterward. When they had to move from their flat to an attic room in a small villa near the high school, they gave up most of their furniture. They kept only the bare necessities, and thus another of their cozy homes originated. When some of her friends, who were threatened, like herself, by deportation to Terezín, asked her: “Why do you bother? Is it worth it? In a few days we will go to Terezín anyway!” She answered, “If I had to live a single day, it is worth living that day.”Footnote 80

Even in these circumstances, Dicker-Brandeis continued to paint and draw in various idioms (Figures 1 and 2) and was able to send works for an exhibition in London, curated by art dealer Paul Wengraf.Footnote 81

One of her most enigmatic works from this period, the 1940 Lenin and Don Quixote, melds the vocabulary of fantasy with a mathematical diagram (Figure 12). A looming shadowy figure, Lenin points toward a red geranium. Behind him, Don Quixote sits astride a robust white stallion, actively rearing like a healthy Lipizzaner. He leans forward to touch Lenin's shoulder as they both point toward a diagram in the foreground. Its dotted lines are in the shape of Kepler's triangle, a Pythagorean triangle that is formed with three squares that progress in size according to the golden mean. Bricolaging together such disparate subject matter as a diagram from geometry, a historical personage, and a character from literature, Dicker-Brandeis presents in this late work a rebus-like allegory that appears as if conjured from a wondrous dream, whose mysterious meaning may have perplexed even the dreamer. According to her friend Hilde Kothny, the image source was in fact a dream: “It was Friedl's dream. She jumped out of bed and immediately started to paint, right on the canvas. Friedl was always creating allegories: Don Quixote, the development of Pythagoras . . . her never-ending allegories. I begged her to sell me that painting, but she could not be persuaded. After prolonged arguments, she finally gave it to me a short time before her deportation.”Footnote 82 Dicker-Brandeis once used the word “interconnectedness” to describe what she admired most about Klee's approach: “He establishes his own interconnections between individual parts—whether they be the earth, sky, the painting's title or what is depicted. He is a mathematician who works not with numbers, but with the values and connections between them.”Footnote 83 Dicker-Brandeis's words about her teacher could well describe her own work. Lenin and Don Quixote registers connections between different planes of representation: the “real” geranium, which is an example of mathematical harmony in the plant world (the Fibonacci sequence), the harmonious order of Pythagorean geometry, and the historical and literary figures who unite as chimerical figures of the imagination. There is light and dark, and a reference to the harmony of the universe: the Pythagorean triangle is a discovery that cannot be undone by politics. Cervantes, Lenin, Pythagoras, and nature—the interdisciplinary allegory covers themes of politics, idealism, misprision, imagination, fantasy, and the enduring forms of nature and pure geometry, inviting multiple readings.

FIGURE 12: Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, Don Quixote and Lenin, ca. 1940. Oil on canvas, 77 × 100 cm. Private collection. Photo: author.

When her husband received deportation orders to Terezín in 1942, Dicker-Brandeis volunteered to go with him and used much of her quota of 110 pounds of baggage to prepare to teach children there.Footnote 84 She filled two suitcases with art supplies and sheets dyed green to throw over children to create a forest in a play.Footnote 85 Using her skills in teaching and stagecraft, she created a colorful world within the concentration camp—leaving such an important set of legacy materials that they have overshadowed her own art production, much of which was destroyed or lost. It was during this time that Dicker-Brandeis embraced Klee's aesthetic again and dedicated one of her last works to him. One can hear echoes of Klee's teaching from one of her students, a teenager at Terezín, who recalled that Dicker-Brandeis encouraged them to draw “what we like to do, what we dream about. . . . [She] transported us to a different world. . . . She painted flowers in windows, a view out of a window. She had a totally different approach. . . . She didn't make us draw Terezín!”Footnote 86 Unlike Gropius, who wanted to reconstruct the world with technology, Klee had wanted to create an alternate universe through art and imagination: “The more horrible this world (as today, for instance), the more abstract our art, whereas a happy world brings forth an art of the here and now.”Footnote 87 Dicker-Brandeis, ever the artist and political activist, now used art to create an escape and alternative world for the interned children. Dicker-Brandeis again volunteered for the transport train to Auschwitz, because she wanted to follow her husband, who had been on the previous train. Of the 1,715 people on her train (23 October 1944) only 211 survived. Dicker-Brandeis was murdered in the gas chambers. Her husband survived his internment, in part thanks to the carpentry skills that Dicker-Brandeis had encouraged him to learn.

The story of Friederike “Friedl” Dicker-Brandeis, only briefly outlined here, is only one of the many others to tell of her generation, many of whose lives ended in exile and murder. Yet their networks and circles of influence are more difficult to track than those of the previous generation. By necessity, Vienna's network of underground activists hid their political activities and the identities of fellow participants, which included not only Dicker-Brandeis but also Edith Tudor-Hart (1908‒73), whose photographs appear in Dicker-Brandeis's Dadistic collage series.Footnote 88 Tudor-Hart, a dedicated Communist, learned photography at the Dessau Bauhaus and documented street life and Communist demonstrations in Vienna in the 1930s.Footnote 89 Trude Waehner (1900‒79), for another example, was active in the political underground in Vienna and also created political works of art; she was an integral part of the Werkbund.Footnote 90 Together, these artists raise the fascinating possibility that some of the most politically charged and disruptive art of Vienna's interwar years may have come from women. And insofar as these artists present a far richer landscape of possibilities that has yet to be written, finding new ways to combine their daring, heroic stories and personal artistic legacies with history as it is now written will require its own ars combinatoria—one that is sensitive not only to the aesthetics of other disciplines like dance and music, but that also requires the skills of a detective working a cold case. Although so many of Dicker-Brandeis's works have been lost or destroyed, the remaining works and their reproductions contain the possibility of memory. However, the objects do not speak by themselves but require some activation or engagement on the part of the spectator. This qualification is crucial because there are so many works by women that have yet to find a central place in histories of modern art and design, at least as it is now construed. Beyond the evaluation of any individual object, which remains the usual focus of the art historian, Dicker-Brandeis's daring life, her intersecting networks of fellow artists and intellectuals, open a window onto reframing the legacy of Vienna 1900. To understand the critical legacy of Vienna's “ambivalent modernism,” then, is not only to acknowledge its negative history, its racism and misogyny, but also to examine forgotten aspects of its positive potential—of interdisciplinary arts, dance, theater, architecture, and the participation of women.