Introduction

It is becoming increasingly common for patients to be diagnosed with more than two long-term health conditions, known as multi-morbidity. A recent cohort study identified 27.2% of patients in England from a sample of over 400,000 as having multi-morbidity (Cassell et al., Reference Cassell, Edwards, Harshfield, Rhodes, Brimicombe, Payne and Griffin2018). Adults over the age of 65 years have an increased likelihood of having multi-morbidity, and this rate is predicted to increase over the next 15 years (Kingston et al., Reference Kingston, Robinson, Booth, Knapp and Jagger2018), as people are living longer and are surviving acute illnesses at a growing rate (Uijen and Lisdonk, Reference Uijen and Lisdonk2008). A third of patients with multi-morbidity also have a diagnosed mental health condition (Cassell et al., Reference Cassell, Edwards, Harshfield, Rhodes, Brimicombe, Payne and Griffin2018), and an increase in the number of long-term health conditions is associated with a higher likelihood of having a mental illness (Kingston et al., Reference Kingston, Robinson, Booth, Knapp and Jagger2018).

The increasing prevalence of multi-morbidity has an impact on health services, placing a strain on services. Patients with multiple long-term health conditions account for the majority of GP consultations (52.9%), hospital admissions (56.1%), and over three-quarters of prescriptions (78.7%; Cassell et al., Reference Cassell, Edwards, Harshfield, Rhodes, Brimicombe, Payne and Griffin2018). The need for services and associated costs is further inflated by the presence of mental health symptoms and disorders. Those with multi-morbidity including a mental illness have an estimated increase in healthcare costs of up to 45% (Mental Health Taskforce, 2016). Furthermore, those with depression have poorer outcomes of physical illnesses, as well as increased mortality (Carney et al., Reference Carney, Freedland and Sheps2004; Hjerl et al., Reference Hjerl, Andersen, Keiding, Mouridsen, Mortensen and Jorgensen2003).

Integrated services are key for supporting people with multi-morbidity. These services take a person-centred approach that combines both mental and physical health interventions (Monitor, 2014). They are co-ordinated efforts that put the individual first, rather than focusing on one symptom or condition. A systematic review of 267 studies found evidence that integrated care models increased patient satisfaction, improved perceived quality of care, and led to better access of services (Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Johnson, Chambers, Sutton, Goyder and Booth2018). However, there is currently limited evidence of cost effectiveness.

Research has also indicated that integrated services can be effective in improving symptoms of both physical and mental illness in people with multi-morbidities. A randomised controlled trial found that patients with depression and co-morbid physical health problems had a reduction in depression symptoms and an improvement in self-management of chronic illnesses (Coventry et al., Reference Coventry, Lovell, Dickens, Bower, Chew-Graham, McElvenny and Gask2015). Further research found that patients with heart failure and chronic lung conditions treated with CBT had improved symptoms of depression and anxiety, which was maintained over time (Cully et al., Reference Cully, Stanley, Petersen, Hundt, Kauth, Naik and Kunik2017). This integrated approach was found to be acceptable to patients, feasible and effective in reducing symptoms (Cully et al., Reference Cully, Stanley, Petersen, Hundt, Kauth, Naik and Kunik2017).

Within integrated psychological services for those with multi-morbidities, a transdiagnostic approach is a common intervention. This is a holistic method which is a unified intervention of disorders (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Allen and Choate2016). Transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural therapy (tCBT) aims to treat a range of conditions or symptoms that recognises shared mechanisms and aetiologies across presenting problems (Cowles and Nightingale, Reference Cowles and Nightingale2015; Newby et al., Reference Newby, McKinnon, Kuyken, Gilbody and Dalgleish2015).

There is growing evidence that tCBT is efficacious in treating comorbid psychological disorders (Cowles and Nightingale, Reference Cowles and Nightingale2015; Hague et al., Reference Hague, Scott and Kellett2015; Cowles and Nightingale, Reference Cowles and Nightingale2015; Rector et al., Reference Rector, Man and Lerman2014). In addition, research indicates that tCBT can be helpful in a case with a complex mental health presentation (Mohlman et al., Reference Mohlman, Cedeno, Price, Hekler, Yan and Fishman2008). However, currently there is limited research into the use of tCBT for integrated services, treating psychological disorders related to physical health problems. One encouraging study found that internet-based tCBT led to clinical improvements in physical and psychological symptoms in patients with gastrointestinal disorders (Dear et al., Reference Dear, Fogliati, Fogliati, Gandy, McDonald, Talley and Jones2018). These effects were maintained at 3-month follow-up, indicating sustained benefits of tCBT (Dear et al., Reference Dear, Fogliati, Fogliati, Gandy, McDonald, Talley and Jones2018).

Conducting research into the use of tCBT is important due to the prevalence of multi-morbidity and the psychological impact that this often has on the individual. This paper reports a case of a patient with multiple physical health conditions and associated mental health problems. An integrated tCBT approach was used in order to support the individual, who is diagnosed with schizophrenia, Parkinson’s disease, heart failure and other health conditions that impact her psychological wellbeing.

In this paper the aims are as follows: to explore the interaction of physical and mental health in a patient with multi-morbidity and how this impacts therapy; to assess the value of an integrated model for use in treating a patient with multi-morbidity; and to identify elements of tCBT that reduce depression and anxiety symptoms in a patient with multi-morbidity.

Case study

Demographics

Ms D is a retired 81-year-old Caucasian woman who lives alone in a flat. Ms D worked in a professional role. She is a widow and has three children.

Physical health history and its impact

Since 2016, Ms D has had deteriorating physical health which has impacted her life in various ways (Table 1). She was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, which has impacted Ms D’s general movement and mobility. She is no longer able to do some of the things she used to enjoy because of this. Ms D was also diagnosed with congestive heart failure, which has caused a shortness of breath and limits her physical activity. Currently she can only walk short distances with the use of a walking stick. Ms D has some equipment within her home which aid in her mobility and daily living activities. Her health deterioration has had a great emotional impact, as she struggles to come to terms with the things she is no longer able to do. This has made her feel low, frustrated and embarrassed. This has also impacted on how Ms D feels about herself, often having thoughts of being useless, not deserving help from others, and feeling as though she is not worthwhile.

Table 1. Medical history in chronological order

Ms D is prescribed 13 medications for her health, including Sertraline (200 mg OD) and Olanzapine (10 mg OD) for her mental health, and Sinemet (25–100 mg OD) and Co-careldopa (12.5–50 mg QD) for her Parkinson’s disease. There is a potential for interaction between the medication for schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease. The patient reported that the symptoms were managed well by medication. Some of the prescribed medications may cause drowsiness, although this was not reported by the patient.

Mental health history

Ms D has experienced periods of low mood throughout her life. After the birth of her second child she suffered from postnatal depression.

Ms D was seen for 15 sessions of individual psychotherapy under the Older Adults Mental Health Team in 2014 following a period of low mood and anxiety. She was then seen in 2016 for a further nine sessions within the same team. In both instances she found the input helpful.

Ms D has a long-standing diagnosis of schizophrenia which is managed with medication. Previous symptoms included occasionally hearing music and smelling smoke. She has been under the Older Adults Community Mental Health Team and currently has contact with the psychiatrist, community psychiatric nurse and support worker. Ms D has not experienced symptoms of psychosis for several years.

Social history

Ms D was the youngest of three children. She describes herself as being unwell as a child, suffering from illnesses such as rheumatic fever and measles. Because of this, Ms D often required more attention from her mother. This caused jealousy from her siblings; in particular she remembers them telling her she was useless. Ms D enjoyed her time at school, and performed well in most subjects. At 18, she attended university and obtained a degree, and had a career in a professional science-based role. She met her husband at work, and they had three children together. He died in 2012, and Ms D has lived alone since then. Ms D has social contact through a day centre which she attends weekly.

CBT formulation

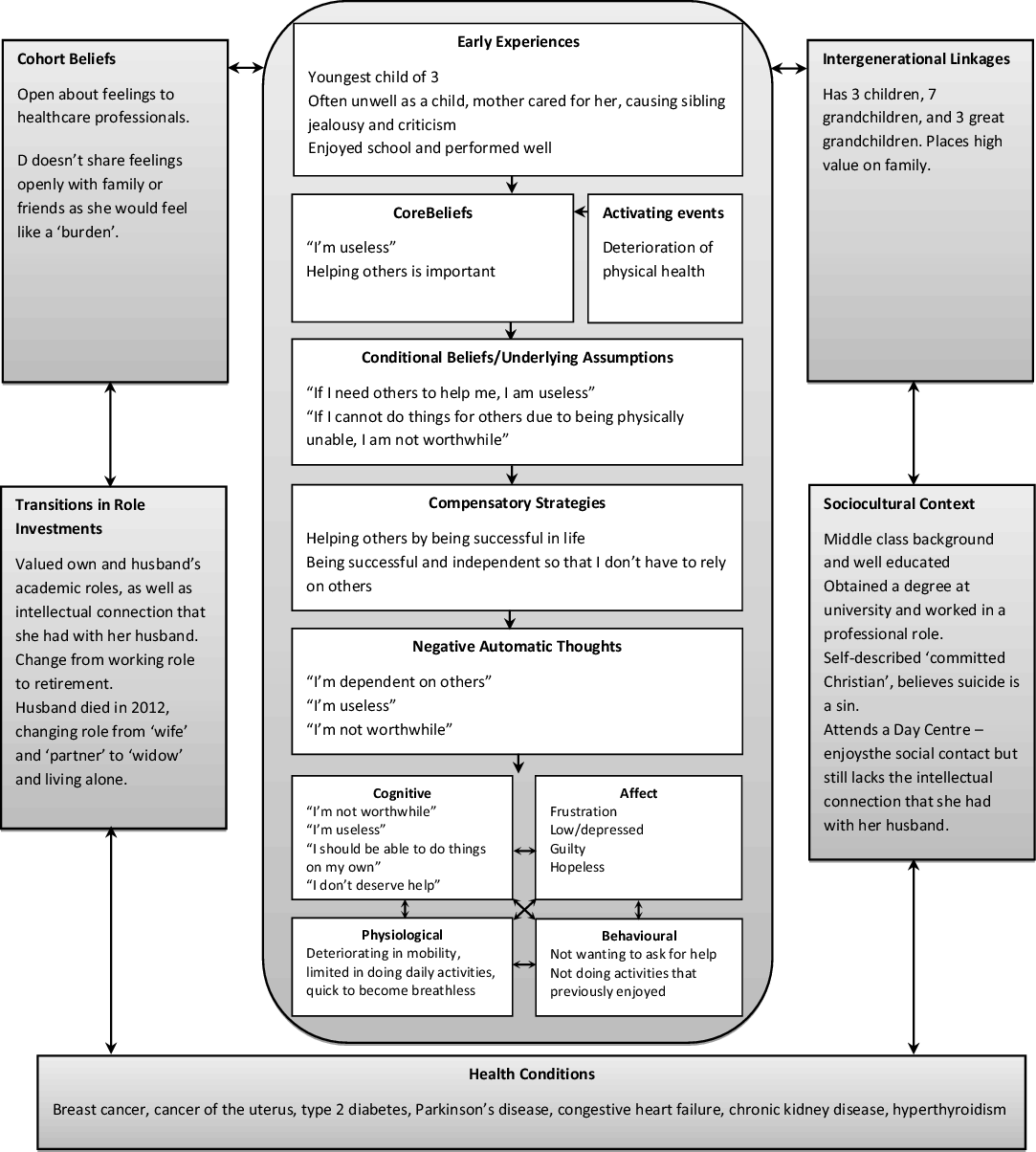

The formulation (Fig. 1) was devised using Laidlaw’s Cognitive Behavioural Model for Older Adults (Laidlaw et al., Reference Laidlaw, Thompson and Gallagher-Thompson2004).

Figure 1. Formulation of the presenting problems.

Intervention

A transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural approach was used to create an individualised plan of therapy, based on the above formulation. The intervention was delivered at the patient’s home. The therapy was delivered by an assistant psychologist who was trained in tCBT and supervised by a qualified consultant clinical psychologist. The patient was seen within the PINC service (Psychological Interventions in Nursing and Community), an integrated service that provides psychological support to patients with long-term health conditions.

Session 1: Formulation and goal setting

Ms D was introduced to the cross-sectional model of CBT and psychoeducation was completed regarding the interaction between each of the areas. Goals for therapy were:

To feel more worthwhile;

To be more accepting of my current situation;

To be kinder to myself about things that I cannot change.

Session 2: Recognising thoughts

Negative thoughts were elicited that occur often for Ms D in the context of specific situations. These were written from the perspective of Ms D:

(1) When someone has to help me do something, because of my physical limitations, I feel low, frustrated and guilty. The thoughts that occur in this situation are ‘I should be able to do this myself’, ‘I don’t deserve help’, ‘I don’t do anything to earn help from others’, ‘I’m not worthwhile’.

(2) When I try to do something but I can’t, due to my physical limitations, I feel frustrated. This makes me think ‘I’m useless’, ‘I should be able to do this’.

(3) When I try to do something and I become breathless, I feel anxious and frustrated. This makes me think ‘I can’t do anything for myself’ and ‘I’m useless’.

Using the Downward Arrow approach, the ‘core’ thoughts elicited were the most difficult thoughts for Ms D, e.g. ‘I don’t deserve help’ → ‘I’m not worthwhile’, and ‘I can’t do anything for myself’ → ‘I’m useless’. The core thoughts that were common across these situations were ‘I’m useless’ and ‘I’m not worthwhile’.

Session 3: Problem solving and thought challenging

Problem solving was used initially in this session as Ms D had recent frustrations regarding her healthcare and appointments. Ms D was supported to list possible solutions, and planned how to carry these out. Thought challenging (including evidence generation) was used for the core thoughts as shown in Table 2. The homework agreed was to recognise when the negative thought was elicited, and to practise thought challenging and alternative thought.

Table 2. Thought challenging for the thought ‘I’m useless’

Sessions 4–6: Self-esteem work and thought challenging continuation

The therapist elicited some positive attributes from Ms D about herself, including ‘I have a good sense of humour’, ‘I’m intelligent’, and ‘I care about others’.

Continuation of thought challenging was undertaken for the thought ‘I’m not worthwhile’ (Table 3), to facilitate the self-esteem and previous thought challenging work. Ms D defined being worthwhile as being helpful to others, being someone that others like, and being someone that others want to be around.

Table 3. Thought challenging for the thought ‘I’m not worthwhile’

After practising the alternative thoughts between sessions, Ms D recognised that the strength to which she held the belief had reduced. She felt that she still struggled on some days when her mood was low, but in general the thoughts were less distressing. Some psychoeducation was completed around the idea that it is okay to have bad days sometimes, and that showing self-compassion during these down days would be important.

Sessions 7–8: Worry management and recognising positives

Psychometric testing indicated that Ms D had continued to struggle with worry. Psychoeducation and normalisation were presented around worry. The therapist introduced Ms D to the Worry Decision Tree, which helps to process worries into categories – worry that can be resolved, and worry that can’t be resolved that should be moved on from. Strategies for moving on from worry were discussed that would capture Ms D’s attention, including reading and listening to music. Ms D continued to practise her alternative thoughts, and used the Worry Decision Tree through the week when new worries arose. The Worry Decision Tree helped Ms D to problem-solve her worries, and then move on when nothing more could be done. Ms D found that reading was particularly helpful.

A positivity diary was introduced to Ms D to help her to acknowledge good things that happen during the week. It was felt that this could be helpful, as Ms D often has many perceived setbacks, particularly in relation to her health, which can overshadow good things that happen.

Session 9: Relapse prevention

With improvement in mood, Ms D was motivated to go back to a lunch club that she had previously enjoyed. Ms D also noted that she had only had negative thoughts a couple of times a week, and was able to use her alternative thoughts and refocus her attention on an enjoyable activity when this happened. A relapse prevention plan was devised to support Ms D moving forward after the sessions (Table 4).

Table 4. Relapse prevention plan

Follow-up 1

A routine follow-up was completed at 3 months, in which the questionnaires were re-administered (including the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, the General Anxiety Disorder Assessment-7, and the Client Service Receipt Inventory). Ms D reported that her mental health had deteriorated during this time, in particular in response to a frustration with services and feeling that her health needs were not being met. Ms D had also deteriorated physically, reporting an increase in breathlessness, which impacted her ability to do things on her own. In light of this, Ms D was offered two additional booster sessions to review the work that had been completed.

Booster sessions 1–2: review of work

Ms D had been admitted to hospital due to breathing difficulties the previous week. This was an acute exacerbation of her physical symptoms, and she had felt better within a few days. This initially impacted Ms D’s mood negatively, but she was able to challenge her negative thoughts of being worthless by doing positive things for other people. For example, she was planning to take a friend out for dinner for her birthday. Ms D felt that this had helped to lift her mood, and focusing on these positives helped her to feel better about herself. The therapist and Ms D discussed the importance of planning these positive and enjoyable activities in which Ms D can have a positive impact on other people. Continuing from this, time was spent reviewing all the different techniques that had been covered in the previous sessions. Ms D was able to continue using the Worry Decision Tree between the booster sessions, which helped her to problem-solve her practical worries. Ms D was also able to plan enjoyable activities for the future. Ms D felt more positive about the future and more equipped to cope with difficult situations when they arose. Ms D was directed back to the relapse prevention plan that was devised, to be used in the event of future setbacks.

Follow-up 2

A second follow-up was completed at 5 months, in which the questionnaires were administered for the final time. Ms D’s health had deteriorated since the booster sessions, which had impacted her mood. In particular, the symptoms of her Parkinson’s disease had progressed, leading to a deterioration in her mobility. Ms D had also been diagnosed with a cyst on her liver, causing her pain and limiting her general movement. Despite these difficulties, Ms D continued to engage in the activities she enjoyed, and to practise the techniques that were devised in sessions.

Following the termination of sessions, the therapist liaised with the community psychiatric nurse (CPN), with whom Ms D had regular and continued contact with. With Ms D’s consent, the therapist provided an overview of the work that had been completed in sessions to the CPN. This included direction that Ms D should continue to practise techniques that had been learnt in sessions, and that prompts may be given to Ms D to engage in these strategies.

Outcomes

Psychometrics

Measures

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001) is a 9-item self-report questionnaire that measures the severity of symptoms of depression. Each item on the questionnaire is scored based on how often the person has experienced the symptom in the last 2 weeks, from 0 (not at all) to 3 (almost every day). The total maximum score is 27, and clinical cut-offs are used to distinguish the severity of the depression, ranging from mild to severe.

The General Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006) is a 7-item self-report questionnaire that measures the severity of symptoms of anxiety. Each item on the questionnaire is scored based on how often the person has experienced the symptom in the last 2 weeks, from 0 (not at all) to 3 (almost every day). The total maximum score is 21, and clinical cut-offs are used to distinguish the severity of the anxiety, ranging from mild to severe.

The PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were used periodically during sessions where it was felt clinically relevant to record any changes in mental state.

Results

As shown in Fig. 2, between the assessment session and session 3 there were scores indicating a moderate to moderate–severe depression. By session 10 the score had reduced to a 3, a score which indicates minimal depression. There was then an increase in scores at the follow-up session, which then reduced back to a minimal level after two booster sessions. A similar pattern can be seen for the GAD-7 scores (Fig. 3), which reduced over time through the scheduled sessions, resulting in a score of 0 by the end of treatment. At the follow-up there was an increase in scores indicating a moderate anxiety, which came back down over the booster sessions to a minimal anxiety. At the second follow-up, the anxiety score remains the same, and the depression score increases to a mild depression.

Figure 2. Line graph depicting scores of the PHQ-9 assessments over time.

Figure 3. Line graph depicting scores of the GAD-7 assessments over time.

Contact with services

Measures

The Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI) is a self-report tool that measures the person’s use of services over the past 3 months (Beecham and Knapp, Reference Beecham, Knapp, Thornicroft, Brewin and Wing1992). This includes the number of contacts with services, number of hospital admissions, Accident & Emergency attendances, ambulance calls, and number of tests and investigations completed.

The CSRI was collected at four stages: pre-treatment, post-treatment, and at follow-up (times 1 and 2). The data below include only the categories of the CSRI in which data were collected.

Results

The CSRI results show a mixture of increase, decrease and maintenance of the use of services (Fig. 4). The number of GP contacts remained fairly stable over time, ranging from five to eight contacts in a 3-month period. The contacts with the mental health team were more varied, with an increase from three to six contacts at the first follow-up, and a decrease back to three contacts at the second follow-up.

Figure 4. Line graph depicting the data for use of services at pre-treatment, post-treatment and follow-up.

Looking more generally at the total number of contacts with healthcare professionals, Fig. 4 shows that there was a sharp increase in contacts from seven to 17 at the first follow-up. The contacts then decrease to 10 at the second follow-up. For contacts with the emergency services, Fig. 4 shows that contacts remained between 0 and 2 in a 3-month period for the pre-treatment, post-treatment, and the first follow-up. At the second follow-up there was an increase to four contacts, which was all with the ambulance service. The trends for the tests and investigations are similar, with Fig. 4 showing that the number remained within 0 to 2 for until the second follow-up, which found an increase to 7. This was mainly due to an increase in blood tests, which was related to the contacts with the ambulance service.

Interestingly, when the number of contacts with healthcare professionals is plotted with the scores for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 questionnaires, a similar pattern is seen. There is a decrease in contacts and scores at post-treatment, and then an increase at the first follow-up followed by a decrease at the second follow-up (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Line graph depicting the number of healthcare professional (HCP) contacts in relation to the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores.

Discussion

The integration of mental and physical health services is vital in supporting people with multi-morbidity, a third of which have a diagnosed mental health condition (Cassell et al., Reference Cassell, Edwards, Harshfield, Rhodes, Brimicombe, Payne and Griffin2018). Within integrated psychological services, tCBT is used as a holistic, person-centred approach to treat a wide range of conditions. Currently, research into the use of tCBT is mainly limited to co-morbid psychological disorders (Cowles and Nightingale, Reference Cowles and Nightingale2015; Hague et al., Reference Hague, Scott and Kellett2015; Cowles and Nightingale, Reference Cowles and Nightingale2015; Rector et al., Reference Rector, Man and Lerman2014), although there is emerging evidence that tCBT can be effective in integrated services, treating both physical and psychological symptoms in patients with gastrointestinal disorders (Dear et al., Reference Dear, Fogliati, Fogliati, Gandy, McDonald, Talley and Jones2018).

The current case study was interested in the use of tCBT for a patient with multi-morbidity within an integrated service. The patient had a complex picture of physical health problems that impacted her mental health. The aims were stated as follows: to identify elements of tCBT that reduced depression and anxiety symptoms in a patient with multi-morbidity; to explore the interaction of physical and mental health in a patient with multi-morbidity and how this impacts therapy; and to assess the value of an integrated model for use in treating a patient with multi-morbidity.

The formulation devised with the patient was key in guiding the intervention. Thought recording and cognitive restructuring were important elements based on this formulation, and work around self-esteem and recognising positives through a positivity diary were used to reinforce the cognitive restructuring work. In further sessions the therapist and the patient completed some work on worry management, including problem solving of worries, and devising of behavioural strategies for moving on from worries that cannot be problem solved.

The results indicate that there was a reduction in depression and anxiety symptoms during the first nine sessions of tCBT. By the ninth session, the patient had reached recovery of depression and anxiety symptoms, defined by Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) as moving from the clinical range to the non-clinical range (Clark and Oates, Reference Clark and Oates2014). This patient moved from a moderate to healthy level in both depression and anxiety symptoms within the first nine sessions. At follow-up, booster sessions were indicated due to an increase in these symptoms to a moderate/moderately severe range. Through booster sessions, these scores were brought down to a healthy range again, and ‘recovery’ was maintained at the second follow-up for both depression and anxiety symptoms.

However, at second follow-up there was an increase in depression symptoms from the ‘healthy’ to the ‘mild’ range. Research indicates that residual symptoms of depression and anxiety are prevalent in older adults who recover from a major depressive episode (Dombrovski et al., Reference Dombrovski, Mulsant, Houck, Mazumdar, Lenze, Andreescu and Reynolds2007). This indicates that relapse may be an expected outcome of interventions in older adults.

The deterioration in the patient’s mental health was largely associated with a worsening of her physical health. This was demonstrated in the psychometric scores, indicating an increase in psychological symptoms around the times when the patient reported that her physical health had deteriorated. This led to a triggering of the same thoughts and feelings that were reported at the start of therapy. Worsening physical health had interacted with these core beliefs, and was likely to continue to do so as her health deteriorated. Understanding how core beliefs interact with a patient’s physical health problems would be important in other cases, thus it is important to anticipate this with a relapse prevention plan and, if necessary, booster sessions.

In addition to the importance of worsening health, the patient expressed that her mood had dropped due to a frustration with services. This patient had many services involved in her care, each specialising in managing one of multiple diagnosed conditions. These disease-specific services can lead to repetition, delay, confusion and gaps in service delivery which can often lead to patient frustration (Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Johnson, Chambers, Sutton, Goyder and Booth2018). Therefore the dip in mood in relation to this is somewhat expected for this patient, who was likely to have this type of experience of services.

In this case, it was important to plan ahead for future deterioration in physical health. As the service had a limited number of sessions that could be offered due to commissioning, this involved linking with other health professionals that knew the patient. The community psychiatric nurse who had continued and regular contact with the patient was provided with an overview of the work that had been completed, and was instructed to prompt the patient to engage in the learnt strategies. The aim of this was to mitigate any decline in psychological symptoms related to future physical health deterioration.

The link between mental and physical health was also reflected in the increased contact with services as seen in the CSRI questionnaire. The results from the CSRI data showed the number of contacts with services over a 3-month period. Overall, the data appeared to be varied with no clear indication that tCBT had an impact. This would be expected for a patient such as this, who has several serious physical health conditions, many of which are progressive and therefore will get worse over time. This was related to a deterioration in the patient’s physical health, requiring more contacts with the GP and Mental Health Team. Although the contacts with healthcare professionals reduced at the second follow-up, there was an increase in tests/investigations and contacts with the emergency services at this time point. This was related to a deterioration in the patient’s Parkinson’s disease, causing a limitation in mobility and an increase in the number of falls. Increased use of health resources may have also reinforced this patient’s belief that she was useless, indicating that use of services also had to be taken into account during therapy, as an increase in contact with services may be interpreted as evidence of dependency and lack of ability to help others.

Given the strong link between mental and physical health in this case, it may be helpful for future research to test whether the strength of this link has an impact on outcomes in interventions offered by services. This may be an important individual difference in patients that present with multi-morbidity, which could be used to inform practice in integrated services.

Summary

This study presented a complex case of a patient with multi-morbidity who had associated mental health problems. The use of transdiagnostic CBT was indicated to give an integrated approach to intervention. There were elements of the tCBT that were helpful in depression and anxiety symptom reduction, particularly from a cognitive perspective. To understand the elements that were helpful, it was important to conduct an in-depth formulation of problems, taking into account historical factors, eliciting core negative thoughts and targeting these in treatment.

For this patient, many of the physical health problems were chronic and progressive and likely to worsen over time. This is likely related to the variation in the depression and anxiety symptoms, which appeared to change in line with deterioration in physical health. This was also shown through the number of contacts with services, which indicate that the number of contacts with healthcare professionals closely related to the depression and anxiety symptoms. Despite this, the depression and anxiety symptoms improved throughout treatment and benefits were maintained at the final follow-up. It could be postulated that tCBT helped to moderate the impact of her deteriorating physical health on her mental health. Other forms of therapy such as acceptance and commitment therapy (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson2012) may also play a useful role in helping manage deteriorating conditions given their emphasis on how patients can make the best of such a situation.

Although this case report can give a detailed account of the intervention used in a specific case, there are limitations in generalisation of the findings. Furthermore, it is not possible to establish a cause–effect relationship in this case, so results should be interpreted with caution. Further research could be completed into the effects of transdiagnostic CBT in other complex cases with multi-morbidity, to gain further understanding of the impact of multi-morbidity on mental health, and how it can be treated within psychological services.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

The authors would like to acknowledge the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust for funding a trip to the USA, to visit services who are working with housebound patients with long-term conditions.

Conflicts of interest

Lisa Walshe and Chris Allen have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethical statements

The therapy described ran as part of the Psychological Interventions in Nursing and Community (PINC) service within Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust. It met the standard ethical procedures for this service and abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychological and Code of Conduct as set out by the APA. Informed consent for publication was gained from the patient at the end of therapy.

Key practice points

(1) Deteriorating physical health can have an impact on presenting mental health problems, such as eliciting negative core beliefs, which can be addressed in CBT.

(2) A transdiagnostic approach can be helpful for a complex case presenting with multiple physical health problems that interact with mental health.

(3) An integrated perspective to care is important for those with multi-morbidity who require a person-centred, holistic approach to their health needs.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.