I. INTRODUCTION

One of the most difficult challenges of mature legal systems is the need to balance the demands of stability and flexibility. Flexibility is required to achieve justice in individual cases and to cope with unforeseen contingencies; stability is considered essential both to achieve predictability and to ensure impartiality in the application of the law.Footnote 1 There is a fundamental tension between flexibility and fairness or impartiality. Impartiality is considered a key feature of the rule of law: “[f]aithfulness to the Rule of Law calls for avoiding any frivolous variation in the pattern of decision-making from one judge or court to another.”Footnote 2 An impartial legal system is one “that does the same justice to everyone, regardless of who are the parties to a case and who is judging it.”Footnote 3 Because flexibility can lead to increased variation, it is at odds with the ideals of fairness and impartiality.Footnote 4 The tension between stability and flexibility presents the law with an antinomian dilemma,Footnote 5 which has both a sociological aspect (concerning the capacity of the law to retain its functionality despite the existence of these conflicting demands) and a moral one (concerning the claim of the law to impartiality). In the present article, I explore the way in which the law copes with this dilemma by developing the idea of tolerance of incoherence.

I argue that tolerance of incoherence emerges from the interplay between the inferential and lexical-semantic rules that determine the meaning of legal speech acts. I base this argument on an inferential model of speech acts, which I develop through a discussion of graded speech acts, and on the idea of speech act pluralism (which claims that illocutionary games are governed by multiple and potentially conflicting conventions). This argument assumes that legal acts—the various moves that legal actors (judges, lawyers, plaintiffs, regulators) make in the context of legal interactions (e.g., appoint, hold, object, dissent, charge, enact, marry, enter into a contract)—constitute a species of speech acts.Footnote 6 My thesis is that this tolerance of incoherence explains the capacity of legal systems to maintain stability, despite the fluid and incoherent nature of their doctrinal and conceptual apparatus.

The article proceeds as follows. I start with a brief exposition of speech act theory, as developed by John Langshaw Austin and John Searle, and explain how my approach, which is based on a conventionalist conception of speech acts, differs from theirs. I examine the binary doctrine of infelicities, which Austin and Searle have adopted to distinguish failed speech acts from successful ones (Section II). In contrast to Austin and Searle, I argue that speech acts have a graded structure. The intuition underlying my thesis is that a failure to satisfy part of the conventional rules that regulate the use of speech acts does not necessarily lead to their complete failure. Rather, such infelicities may have an attenuating effect on the illocutionary force of the relevant speech act. This indirect form of attenuation can be combined with more direct linguistic mechanisms that provide speakers with a variety of ways to either attenuate or amplify the force of their speech acts. The conventional framework explicated by Austin and Searle should not be interpreted as establishing rigid prototypical schemas, but rather as setting out focal inferential structures that interlocutors can work around (with appropriate deontic consequences). In Section III, I demonstrate this thesis through an inferential analysis of graded speech acts. I consider first examples from informal, thinly institutionalized settings, then move to examples from the more formal setting of the law. In Section IV, I develop the argument that speech acts should be conceptualized as moves in an inferential game. I argue that we can understand the meaning of speech acts in general, and of graded ones in particular, only by studying the inferential consequences of using speech acts in a dialogue (an illocutionary game). I conclude, in Section V, by introducing my argument regarding the evolution of tolerance of incoherence in law. I link this thesis with the idea of speech act or illocutionary pluralism and with the earlier discussion of graded speech acts. I show how this tolerance allows the law to resolve the tension between dynamism and traditionality, and discuss its sociological and moral implications. In particular, I discuss how my thesis differs from recent work in cognitive moral psychology, which explores the role of consistency judgments in practical morality.Footnote 7

II. SPEECH ACTS AND INFELICITIES: A NORMATIVE-CONVENTIONALIST VIEW

In How to Do Things with Words, J. L. Austin introduced a distinction between constatives and performatives: constatives connote statements of fact that can be true or false; performatives refer to sentences that do not describe, report, or constate anything, but their utterance “is, or is a part of, the doing of an action.”Footnote 8 Examples of performatives are the acts of marrying, betting, bequeathing, christening, etc.Footnote 9 Austin eventually replaced the distinction between constatives and performatives with a more general framework, which distinguishes between locutionary, illocutionary, and perlocutionary acts.Footnote 10 A locutionary act refers to the uttering of a sentence with a certain meaning, which Austin characterizes as “sense and reference.” An illocutionary act refers to the uttering of a sentence with a certain conventional force.Footnote 11 I interpret the idea of conventional force as the capacity of an illocutionary act to create or modify institutional or deontic facts, such as the attribution of commitments, obligations, rights, and powers.Footnote 12 A perlocutionary act refers to the performance of an illocutionary act that has “certain consequential effects upon the feelings, thoughts, or actions of the audience.”Footnote 13

A good way of distinguishing between the locutionary and illocutionary aspects is to note that the same sentence can be used to perform distinct illocutionary acts.

(1) I will call a lawyer.

The above sentence can be used to make a promise, deliver a warning, or make a prediction.Footnote 14 If this sentence is taken as a promise, its utterance creates a new deontic fact, endowing the addressee with the right to have the promise fulfilled, and potentially hold the utterer liable otherwise. Depending on its particular illocutionary meaning, this sentence is expected to produce a different perlocutionary effect on the addressee.

The doctrine of infelicities focuses on cases in which something goes awry in the execution of a performative utterance. Austin described such failed speech acts as unhappy or infelicitous.Footnote 15 Austin and Searle developed a binary approach to infelicities, according to which a speech act either succeeds or fails entirely.Footnote 16 When a speech act is infelicitous, Austin argued, “the procedure which we purport to invoke is disallowed or is botched, and our act (marrying, etc.) is void or without effect … .”Footnote 17 Two examples given by Austin are someone saying “I appoint you” without being entitled to appoint, and someone performing a conventional procedure (e.g., marrying) incorrectly or incompletely.Footnote 18 In both cases, the action is void. According to this approach, for a speech act to be successful it must satisfy a minimal (threshold) subset of the relevant felicity conditions, which then ensure the realization of the deontic consequences associated with the particular speech act.Footnote 19 If these are not satisfied, the illocutionary act fails entirely.

The following quote from Searle and Vanderveken illustrates the binary approach. The authors distinguish between completely successful and successful but defective speech acts on one hand, and unsuccessful (failed) acts.Footnote 20 Despite its tripartite structure, this framework maps any speech act into the binary categories of successful/unsuccessful acts.Footnote 21

A speaker might actually succeed in making a statement or a promise even though he made a mess of it in various ways. He might, for example, not have enough evidence for his statement or his promise might be insincere. An ideal speech act is one which is both successful and nondefective. Nondefectiveness implies success, but not conversely. In our view there are only two ways that an act can be successfully performed though still be defective. First, some of the preparatory conditions might not obtain and yet the act might still be performed. This possibility holds only for some, but not all, preparatory conditions. Second, the sincerity conditions might not obtain, i.e., the act can be successfully performed even though it be insincere.Footnote 22

Searle and Vanderveken did not consider the possibility that a defective or failed speech act may possess a reduced degree of illocutionary force.Footnote 23

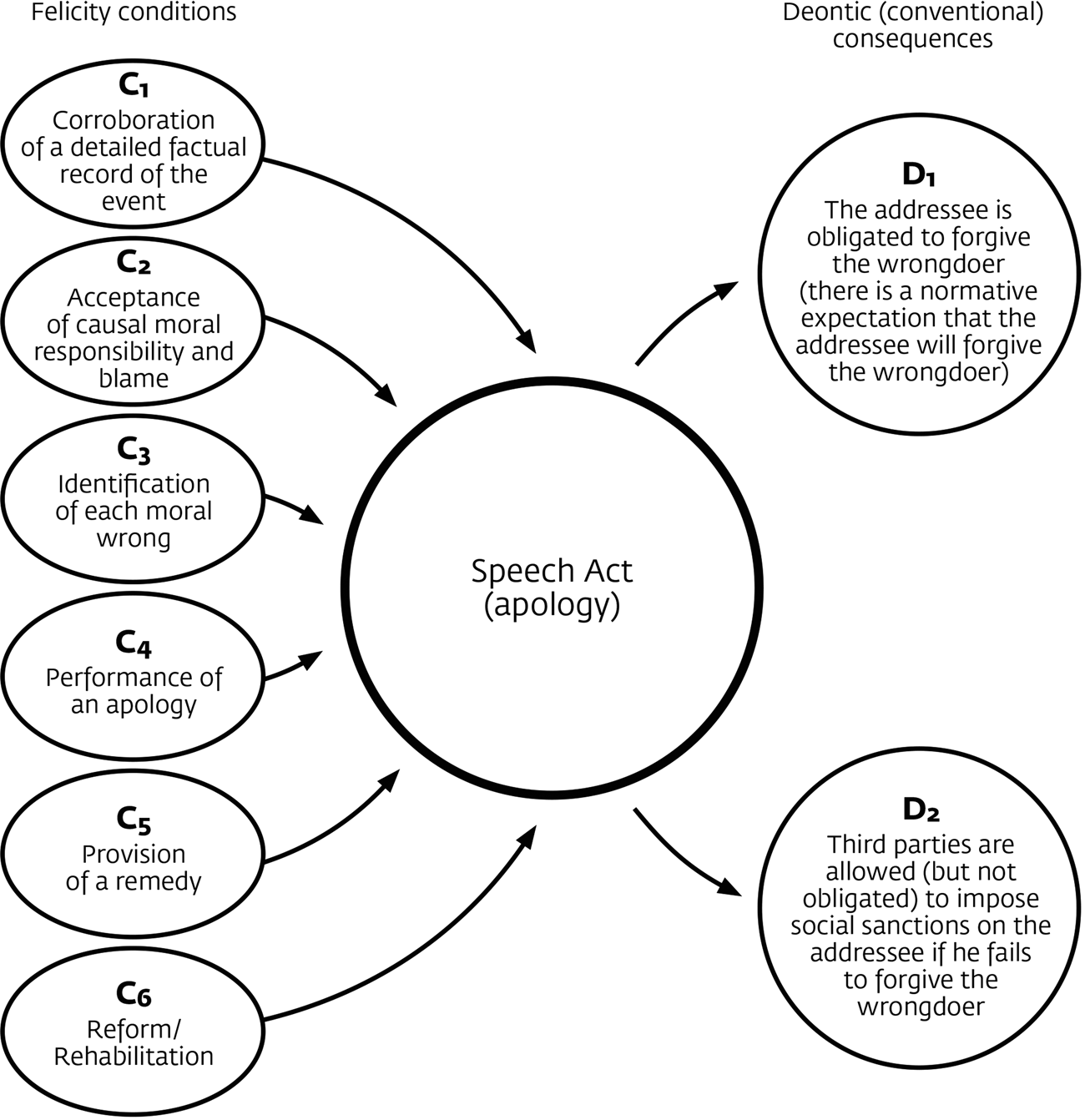

The success of an illocutionary act is realized by the achievement of certain deontic effects, which correspond to the illocutionary point of the act.Footnote 24 Being conventional, this deontic transformation depends on the conformity of the illocutionary act to the relevant convention.Footnote 25 Consider the speech act of apology. A valid (successful) apology can be associated with the following deontic transformations. First, it can establish a duty on the part of the addressee to forgive the person issuing the apology, thereby freeing the speaker from a debt owed to the addressee;Footnote 26 second, it can entitle third parties (but not obligate them) to sanction an addressee who refuses to forgive the person issuing the apology. The former transforms the deontic statuses of the speaker and the addressee; the latter transforms the deontic statuses of third parties.

Note that my account differs in some respects from Austin's original view. According to Austin, the “performance of an illocutionary act involves the securing of uptake”; it “amounts to bringing about the understanding of the meaning and of the force of the locution.”Footnote 27 Thus, an apology succeeds not if the addressee accepts it (the perlocutionary aspect) but if the addressee recognizes it as such. By contrast, I distinguish between the normative and psychological aspects of uptake.Footnote 28 The normative aspect refers to the question of whether the speaker has conformed to the relevant (nonlinguistic) conventions governing apologies (or other speech acts).Footnote 29 The psychological aspect concerns the question of whether a particular addressee has reached the appropriate cognitive state of recognition.Footnote 30 For a speech act to be successful, it is sufficient for it to conform with the relevant conventions. The recognition of the addressee is therefore not a necessary condition for the success of a speech act. The psychological aspect should further be distinguished from the perlocutionary one, which focuses on whether the speech act has triggered a behavioral reaction that corresponds to the illocutionary point of the speech act (e.g., forgiveness in the case of apology).

III. INFERENTIAL ANALYSIS OF GRADED SPEECH ACTS

A. Graded Speech Acts in Informal Contexts

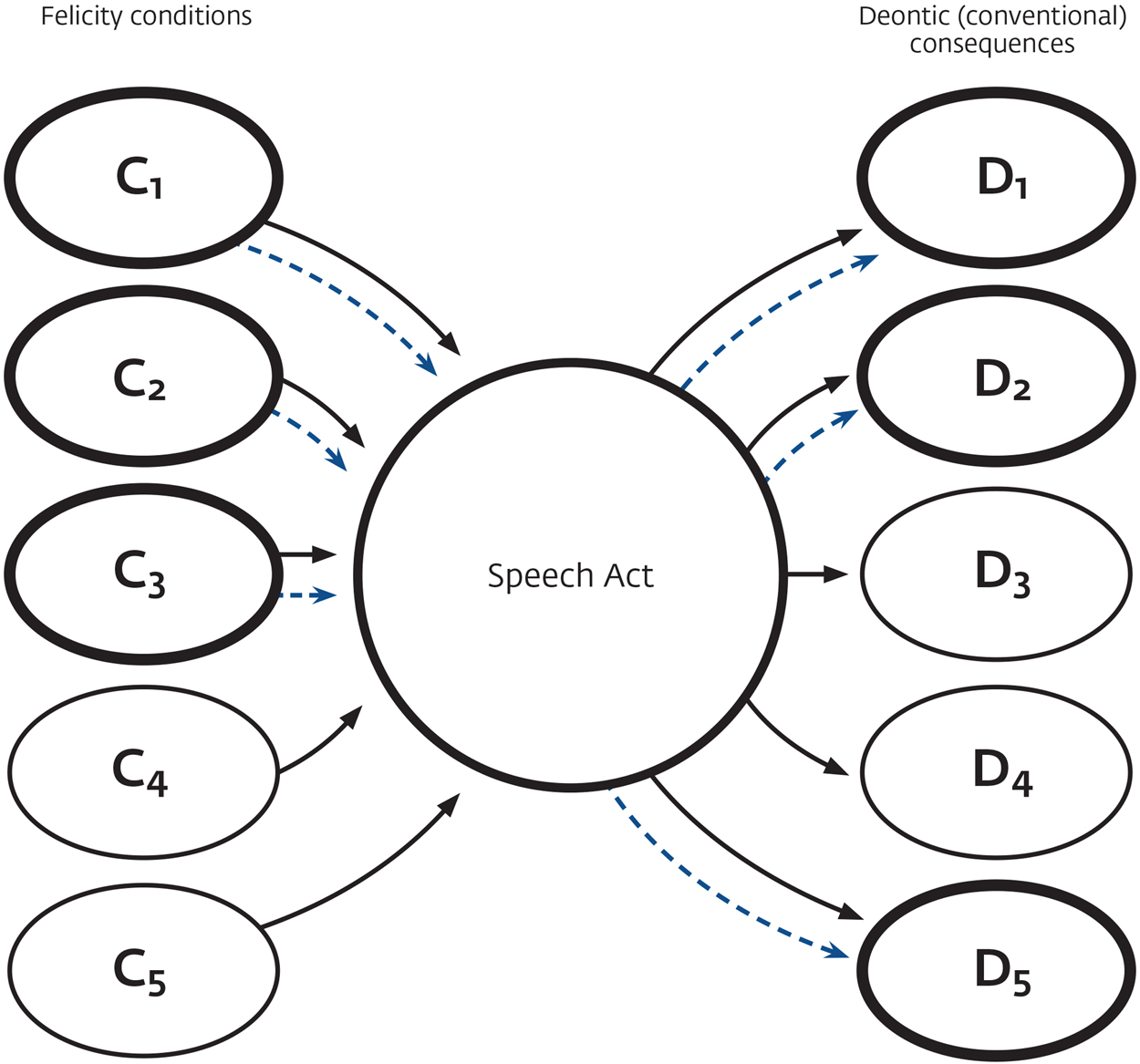

I propose to replace Austin and Searle's all-or-nothing approach to infelicities with the more nuanced concept of graded speech acts. According to this concept, the conventional schemas that Austin and Searle explicate for different types of speech acts operate only as prototypical signposts: failing to meet the requirements of these schemas does not necessarily lead to the complete failure of the given speech act. A graded speech act may succeed in achieving part of the deontic consequences of a fully successful one, depending on the extent of its divergence from the prototypical schema. This argument conceptualizes speech acts as moves in an inferential game. Replacing the binary model of Austin and Searle with a more open-ended, inferential framework extends the combinatorial possibilities for linking the felicity conditions associated with a particular speech act with deontic consequences.Footnote 31 Another important feature of the inferential model is the defeasible structure of speech acts. Graded speech acts either may need additional support to achieve the deontic or conventional results associated with a fully successful speech act, or may be defeated by arguments that a successful speech act can overcome.

Below are several examples that illustrate my thesis regarding the inferential structure of graded speech acts. I start by considering the way in which graded speech acts are used in informal contexts.Footnote 32

My first example focuses on apologies, which belong to the family of expressives. The illocutionary point of apologies is to convey the psychological state of the speaker with respect to a concrete state of affairs specified in the propositional content of the speech act (e.g., thanking, praising, apologizing). The speech act of apology is governed by multiple conventions that vary across social contexts.Footnote 33 The rules that govern apologies for major corporate wrongdoingFootnote 34 differ from those that govern minor everyday infractions,Footnote 35 which in turn differ from those that regulate communicative transgressions in online communication (e.g., blogging).Footnote 36

To illustrate my thesis, I focus on apologies in the case of serious social wrongdoings, using the concept of categorical apology, proposed by Nick Smith. Smith characterized his project as both descriptive and normative. The concept of categorical apology constitutes, on one hand, “a regulative ideal for acts of contrition”;Footnote 37 on the other hand, the elements underlying this concept are also “implicit in our commonsense expectations of apologies.”Footnote 38 According to Smith, a categorical apology should include the following elements: a detailed description of the events salient to the injury, acceptance of causal moral responsibility for the harm (distinguishing between each moral wrong), performance of an apology, and reform and redress.Footnote 39 This account of apology is not applicable to every type of wrongdoing. For example, a minor everyday infraction, such as accidentally bumping into somebody on a crowded platform of a railway station, is probably not serious enough to warrant the type of apology described by Smith.Footnote 40

Consider the apology issued by Donald Trump for the crude comments he made about women in 2005:Footnote 41

(2) I've never said I'm a perfect person, nor pretended to be someone that I'm not. I've said and done things I regret, and the words released today on this more than a decade-old video are one of them. Anyone who knows me knows these words don't reflect who I am. I said it, I was wrong, and I apologize.

Trump's statement clearly includes some of the elements of categorical apology. He said that he was wrong (indication of moral responsibility) and he performed the act of apology (by publicly stating that he apologizes). But his statement also falls short of a complete apology in several key elements. Trump did not offer a factual record of his wrongdoing, did not endorse the moral principles that were harmed (women's dignity), and did not offer any kind of redress to the victims. Finally, he did not seem to change his attitude toward women after issuing the apology.Footnote 42

The concept of graded speech acts suggests that partial apologies, such as the one offered by Trump, may be able to achieve some of the conventional effects associated with complete apologies. Although Trump's apology may be “too incomplete” and thus void, other types of partial apologies that satisfy additional conditions may be able to produce some consequences. Thus, depending on our view of the deontic consequences of a complete apology, we can argue that a partial apology may turn the act of forgiveness from obligatory into supererogatory, or from supererogatory to merely permissible.Footnote 43 Given that a partial apology does not produce an obligation to forgive, the deontic consequences of a failure to forgive are also likely to change. For example, unlike in the case of a complete apology, the imposition of sanctions for refusal to forgive will not be appropriate in this case; third parties, however, may still be entitled to express disappointment with the decision of the addressee not to respond with forgiveness.

Figures 1 and 2 provide a schematic description of an inferential understanding of graded speech acts, using apologies as a test case. Figure 1 describes the inferential structure of a complete apology, and Figure 2 describes the structure of a partial apology.

Figure 1 Inferential analysis of a complete apology

Figure 2 Inferential analysis of a partial apology

My second example focuses on the family. We tend to think about the family as the antithesis to a formal organization because it is associated with intimacy and love rather than formal rulebooks. But family life is rife with rule-like structures.Footnote 44 Such rule-like structures are either set up unilaterally by the parents or are the product of contractual negotiations between parents and children, what Aronsson and Cekaite call “activity contracts.”Footnote 45 But if life in the family is governed, at least partially, by rules, we should also be able to find cases of infelicitous speech acts with a graded structure. Consider the following family interaction. In a certain family, there is a practice that both parents must vet unusual requests by the kids. The son returns from school and asks his father whether he can sleep over at his friend's house on Friday. The father approves the request without consulting his wife. What is the status of his promise? Is it valid, given that not all the preparatory conditions have been satisfied (joint parental approval)? I suspect that in most families this faulty promise nevertheless carries some normative weight. In practice, such partial weight means that the parents can back down from the promise, but would have to provide some additional justification to defeat the normative expectation that was created by the infelicitous promise (e.g., “we have to leave early on Saturday, I forgot to mention it earlier”).

The last example draws on Rebecca Kukla's recent work on discursive injustice.Footnote 46 Kukla argued that in some circumstances, when a woman deploys standard discursive conventions to produce a speech act with a certain performative force (e.g., directive), her utterance can turn out to have less force than it would have had had it been performed by a man. One way to understand the illocutionary attenuation of directives issued by women, as described by Kukla, is to consider it as a breach of the governing discursive convention, because presumably all the felicity conditions for issuing a directive have been met.Footnote 47 Yet, it can also be interpreted as an outcome of a discursive convention that limits (by including a gender-attenuating rule) the capacity of women to issue certain directives. Most people would consider such convention, to the extent that they exist, morally obnoxious, but as Kukla and othersFootnote 48 have convincingly argued, their structure reflects the same graded pattern I described in the context of apologies.

B. Graded Speech Acts in Formal Settings: The Case of Law

Because legal acts can be viewed as a species of speech acts, law offers a particularly apt setting for the study of speech acts.Footnote 49 In this section, I argue that law has developed nuanced doctrinal structures that follow a similar inferential pattern to that of graded speech acts. My first example focuses on the doctrines of voidability and relative voidance. These were developed by courts in view of their dissatisfaction with the classical doctrine of absolute voidance, which takes a binary approach to the question of legal validity. A law that fails to satisfy the meta-rules of legal validity has no legal force: it is considered void from the outset (ab initio), as if it had never existed.Footnote 50 Under the absolute voidance doctrine, a ruling that a certain statute is invalid applies retroactively, from the moment of the flawed enactment of the law, automatically nullifying all the acts and legal measures whose validity depends on it.Footnote 51 Legal acts can fail to be valid in three main ways. First, the person or institution that attempts to perform the legal act may lack the authority to do so. A lack of authority could be due, for example, to invalid appointment or to lack of subject-matter or personal jurisdiction.Footnote 52 Second, a legislative act is considered invalid if its enactment process failed to adhere to legislative procedures.Footnote 53 Finally, in a constitutional regime, a law enacted by the parliament may be deemed null and void if it is inconsistent with the provisions of the constitution.

Austin's concept of “making undone,” which he outlined in the preparatory notes to How to Do Things with Words, has a similar structure to that of the legal doctrine of absolute voidance.Footnote 54 Marina Sbisà noted this similarity, pointing out that although the effects of our actions are usually irreversible, illocutionary acts appear to be an exception, because they may turn out to be null and void if certain conditions are found not to be satisfied:

This does not mean that what was actually done did not really take place, or that nothing at all was done by the performer of the infelicitous act … the discovery of infelicity may make the illocutionary act undone insofar as the bringing about of its conventional effect is concerned. The words were uttered, the conventional effect was supposed to be there, it was even acted upon for a while; but once we discover the infelicity, we realize that the conventional effect never really came into being.Footnote 55

Sbisà noted further that “what Austin's remarks on ‘making undone’ attribute to illocutionary acts, namely that which I have called ‘defeasibility,’ goes beyond the cancellability of achieved effects, since it affects the conventional effect in its making, and therefore the act which brings it about.”Footnote 56

Despite its allure of precision and clarity, the absolute voidance doctrine creates both logical and pragmatic difficulties. First, since validity is considered a function of multiple criteria,Footnote 57 it is not obvious why a failure to satisfy only part of these criteria should necessarily lead to the complete voidance of the legal act. These criteria can be procedural in nature (reflecting, for example, various requirements pertaining to parliamentary procedures),Footnote 58 or can have a more substantive nature (reflecting constitutional considerations).Footnote 59 Second, the absolute voidance doctrine seems to assume that void legal acts are furnished with a self-destruct mechanism that cause them to disappear the moment they emerge into the world. This image is misleading, however. In most common law systems, voiding a legal act requires a declaration by a court. Because invalid legal acts do not automatically disappear, third parties may rely on them. A decision to invalidate a primary or secondary legislative act that is already in force is liable to cause grievance to a large number of “innocent” parties.Footnote 60

In response to these logical and pragmatic difficulties, courts have developed more nuanced conceptions of voidance, which have challenged the binary interpretation of validity (law can be either valid or invalid) and have offered instead alternative interpretations based on a graded understanding of validity.Footnote 61 These nuanced interpretations have not been considered by either Austin or Sbisà in their discussion of “making undone.”Footnote 62 Under the voidability approach, an imperfect legal act (which could be an act of parliament, secondary legislation, court ruling, or private legal instrument, such as a will or contract) is not void ab initio; it is only voidable, that is, susceptible to judicial invalidation. This means that the legal act remains valid and enforceable until declared invalid by a constitutive rather than declaratory court ruling. Under this approach, the court has the power to determine whether the invalidating decision applies prospectively or retroactively.Footnote 63 The doctrine of relative voidance, developed by the Israeli Supreme Court, reflects a more nuanced and flexible approach to the question of voidance,Footnote 64 granting the court wide discretion to determine the results of voiding a particular legal act, based on the circumstances of the case at hand.Footnote 65

The inferential structure of the doctrines of voidability and relative voidance is similar to the one found in graded speech acts. Lacking some of the elements needed for a legal act to be fully valid (“happy” in Austin's terminology) does not necessarily lead to its complete failure (“nullity”). Rather, the faulty legal act loses some of its normative consequences.

The U.S. doctrine of “de facto officer” provides an apt illustration of this inferential pattern. According to the de facto officer doctrine, the “lawful acts of an officer de facto, so far as the rights of third persons are concerned, are, if done within the scope and by the apparent authority of office, as valid and binding as if he were the officer legally elected and qualified for the office and in full possession of it.”Footnote 66 This doctrine allows the court to rule that a challenge to the validity of a certain legal act applies only prospectively: “the de facto officer doctrine provides that even if the statutory provision under which a public officer is appointed is vulnerable to constitutional challenge, official actions taken by the public officer before the invalidity of his or her appointment has been finally adjudicated may not be overturned on that basis.”Footnote 67

Courts routinely limit the results of invalidation by making a distinction between prospective and retroactive effects, but at times they do more. A good example is the decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in Buckley v. Valeo.Footnote 68 After concluding that the statutory provisions governing the composition of the Federal Elections Commission violated the separation of powers clause in the U.S. Constitution because four of the six voting members of the commission were appointed by members of Congress, the Court nevertheless upheld the validity of all past actions of the commission, according the “de facto validity” of those actions.Footnote 69 But the Court went further and permitted the unconstitutionally formed Federal Elections Commission to continue to act for thirty days after the ruling was issued. This decision is remarkable because the Court, in practice, kept alive a legal act that under the absolute voidance doctrine was considered completely “dead.”Footnote 70

Another illustration of the inferential dynamics of graded legal acts comes from the law of evidence.Footnote 71 Under the common law rule against hearsay, any assertion, other than one made by a person while giving oral evidence in the proceedings, is inadmissible if tendered as evidence of the facts asserted.Footnote 72 The rule is undergirded by a binary inferential pattern: a testimony can either be admitted in court and maintain its probative value, or if it does not meet the criteria of the hearsay rule, is excluded from the proceedings, and therefore loses its probative value completely.Footnote 73 In everyday communication people use common sense, rather than a strict hearsay rule, to evaluate the epistemic force of second-order testimonies, based on factors such as the reputation or trustworthiness of the witness and the consistency of the testimony with other evidence.Footnote 74 The risk of losing significant information has caused U.S. courts to transform the binary structure of admission/exclusion, which underlies the rule against hearsay,Footnote 75 into a weight-based framework that allows judges to assign reduced probative value to the hearsay testimony, depending on the circumstances.Footnote 76 The weight of the evidence hinges on various factors, such as the reason for the absence of the first-order witness from court, the trustworthiness of the hearsay witness, and more.Footnote 77

According to the foregoing account, indirect (hearsay) testimonies, despite their imperfection, do possess some, even if reduced, probative value.Footnote 78 Consider, for example, the dying declaration exception, which refers to statements made at a time when the declarant was facing imminent death, and presented in court by secondary witnesses.Footnote 79 Various factors can reinforce or weaken the strength of a dying declaration. One of these is the trustworthiness of the declarant. We can distinguish between statements made on a declarant's own initiative, which may have given him time to plan and potentially fabricate the statement, and those made without an opportunity for planning (e.g., following an unexpected violent incident), where the likelihood of fabrication is lower.Footnote 80 Another factor is the trustworthiness of the witness testifying about the content of the testimony. The witness may be more or less sure about what the declarant said, and can use different terms to express levels of confidence, from “insist,” to “presume,” to “suppose,” to “guess.”

Similar nuanced understandings of validity have been developed by courts in other fields of law. For example, in contract law, the prevailing approach to the consequences of defects in contract formation is a nuanced one. Vitiating factors do not necessarily result in the contract being considered void, but rather tend to render the contract voidable.Footnote 81 Similarly, Delaware courts have taken a nuanced approach to the question of the validity of stock that was issued in a way that does not meet all the requirements of Delaware corporate law (rejecting an either/or interpretation).Footnote 82

IV. INFERENTIAL MODEL OF GRADED SPEECH ACTS

A. Exposition

My thesis is that speech acts should be conceptualized as moves in an inferential game. This approach enables us to understand also how graded speech acts may come to possess some pragmatic force. My approach is based on Robert Brandom's inferential semantics. Brandom's central thesis is that:

for a response to have conceptual content is just for it to play a role in the inferential game of making claims and giving and asking for reasons. To grasp or understand such a concept is to have practical mastery over the inferences it is involved in—to know, in the practical sense of being able to distinguish (a kind of know-how), what follows from the applicability of a concept, and what it follows from.Footnote 83

As moves in an inferential game, speech acts can realize the illocutionary potential of the inferential rules governing a particular illocutionary game.Footnote 84 By choosing a particular speech act schema (e.g., apologizing) and satisfying its relevant felicity conditions, an interlocutor can achieve a particular pragmatic purpose (a certain deontic transformation). Under this model, the meaning of a speech act is captured by a mapping from a set of felicity conditions to a set of deontic or conventional consequences.Footnote 85 I call this rule the constitutive mapping of the relevant speech act. This idea assumes that for any type of speech act there exists a constitutive function that maps any subset of felicity conditions associated with that speech act into a subset of the relevant set of deontic consequences.

The inferential model suggests that a graded speech act may succeed in achieving part of the deontic consequences that are associated with a perfect act; a failure to satisfy in full the felicity conditions associated with a particular speech act does not necessarily lead to its complete failure. Austin and Searle assume that the felicity conditions establish rigid prototypes (deontic consequences ensue only upon the satisfaction of all the relevant felicity conditions). By contrast I argue that these felicity schemas operate only as heuristic signposts, which interlocutors can work around while still achieving certain deontic consequences.

The graded model extends the combinatorial possibilities of linking felicity conditions with deontic or conventional effects. This extension can be described mathematically. The number of subsets in a set with n elements is 2n. Each subset of the set of felicity conditions can be linked with each of the subsets of the set of deontic consequences. The exception is the null subset and the complete set of the set of felicity conditions, which can be linked only with the null subset and the complete set of deontic consequences, respectively. Thus, the total number of potential links, with a felicity set with n elements and a deontic set with m elements is:Footnote 86

(1) (2n-2)*2m + 2

If, however, we adopt Austin and Searle's threshold model, we have only two options: we can either satisfy all the felicity conditions (and secure all the associated deontic consequences), or fail to satisfy them, in which case we end up with nothing.

Figure 3 provides a general description of this model.

Figure 3 Inferential model of graded speech acts

In the above account, the partial satisfaction of felicity conditions operates as a nonlinguistic mechanism that enables interlocutors to attenuate the force of illocutionary acts. An inferential account of graded speech acts also needs to consider other mechanisms by which users may modify the strength of speech acts. One such mechanism is the use of specialized illocutionary force indicating devices (IFID),Footnote 87 which reflect either different modes of achieving a particular illocutionary point with varying strengths or differences in the intensity of the expressed psychological state. For example, “order” and “command” are stronger than “ask” and “request,” and so are, in a different way, “beg” or “plead.” The greater strength of order and command derives from the fact that the speaker invokes a position of authority; the greater strength of beg and plead is due to the stronger intensity of the expressed psychological state.Footnote 88 Similarly, in making an assertion, people can vary the force of their claim by using strong expressions (swear, testify, or insist) or weaker ones (suggest, hypothesize, conjecture, guess, suppose, or estimate).Footnote 89 The difference here is due primarily to varying intensity in the relevant psychological state, except, perhaps, for testimony, whose strength may have institutional aspects as well. Speakers can also vary the degree of strength of a speech act by using special modifiers or hedges, as, for example, when a teacher tells the class, “I really want you to be quiet now,” or when a boss tells a new employee, “I strongly suggest you not be late for this meeting.”Footnote 90 Thus, speakers have multiple, and potentially concurrent, ways of varying the strength of the speech acts they produce.Footnote 91

One problem with the above account is that it lacks a dynamic aspect. An inferential understanding of graded speech acts requires us to analyze them as part of a conversation process, an illocutionary game, that revolves around a particular illocutionary call.Footnote 92 In the course of an illocutionary game, interlocutors seek to resolve the status of a particular illocutionary claim by exchanging arguments. Such an illocutionary game can explore, for example, whether Trump's statements involving women constitute an offensive speech that merits an apology,Footnote 93 whether his apology (example (2)) meets the relevant criteria, and what consequences should ensue from it. Daniel Vanderveken distinguished four types of illocutionary games based on the goals interlocutors collectively intend to achieve: descriptive, deliberative, declaratory, and expressive. Interlocutors can engage in a descriptive dialogue, deliberate what to do, change things by way of declarations, or manifest common attitudes.Footnote 94 Each of these conversation types is supported by a unique set of speech acts.Footnote 95 In real-life situations, these conversation types intermingle. Thus, for example, deliberative dialogue is usually preceded by a descriptive one, in which participants pool their collective knowledge;Footnote 96 apology is usually seen as a condition for amnesty.Footnote 97

We can capture the dynamic aspect of illocutionary games using the theoretical apparatus of defeasible logic, which offers a formal framework for understanding how reasons and norms can overcome conflicting reasons and norms or be defeated by them.Footnote 98 I argue that the dynamic of illocutionary games with graded speech acts is governed by two sets of rules or functions. The first is a set of constitutive functions, which link any subset of felicity conditions associated with a particular speech act with a subset of deontic effects. Such functions would also have to incorporate the use of direct linguistic attenuators (specialized IFIDs and boosters). This can be achieved by ranking the varied IFIDs according to their illocutionary force.Footnote 99 For example, an ordinal ranking for commissives can take the following form: swear (to), vow, pledge, assure, promise (the perfect form) > commit, threaten, accept, consent (the partial form). The ranking can be used to distinguish between the conventional effects associated with different verbs. Similar logic can be used to model the influence of linguistic boosters.

The second is a set of priority rules that determine how clashes between conflicting illocutionary claims (and their supporting arguments) are resolved.Footnote 100 The priority rules determine the relative strength of competing claims, which interlocutors may bring in relation to a particular illocutionary claim.Footnote 101 These two sets of rules constitute the conventional framework that determines the meaning of a particular speech act in a given social context.

To illustrate this framework, consider the University of Michigan (Medicine) Disclosure, Apology, and Offer Policy.Footnote 102 Paragraph four of the policy states:

If we have concluded that our care was unreasonable, we say so – and we apologize. If our care caused an injury, we work with the patient and his/her counsel to reach mutual agreement about a resolution. This doesn't always mean a settlement, but if it does, we compensate quickly and fairly.

The wording of this paragraph opens up a wide conversational space in which the meaning and inferential aspects of the different elements of the policy can be contested.Footnote 103 The key elements include: (a) how to distinguish between reasonable and substandard care (e.g., can clinical practice guidelines serve as “safe harbors” for clinicians);Footnote 104 (b) did the “care” cause the patient's injury;Footnote 105 (c) how to define an appropriate apology (e.g., is a mere expression of sympathy sufficient);Footnote 106 and (d) what constitutes fair compensation (e.g., should it include compensation for noneconomic damages, such as pain and suffering).Footnote 107 Each of these contestation points has inferential aspects (e.g., the duty to apologize and compensate arises only if care was unreasonable), and each of them can serve as a focal point for an argument between the parties, whose resolution depends on the content of the applicable priority rules.Footnote 108

B. Graded Speech Acts in Action: Apologies in Bar Admission Proceedings

The case of bar admission proceedings in the United States illustrates my argument about the inferential structure of graded speech acts. I focus in particular on the way in which graded speech acts extend the combinatorial links between felicity conditions and deontic effects. In some U.S. states, applicants to the bar who were involved in some misconduct must show remorse, and if the applicant's apology is judged to be appropriate by the Character and Fitness Committee (“Committee”), the applicant is accepted.Footnote 109 Similar rules are in effect for attorneys who were disbarred and apply for reinstatement. For example, under the rules of the State of Kentucky, the Committee is required to assess whether “the applicant … possesses the requisite character, fitness and moral qualification for re-admission to the practice of law.”Footnote 110 In reaching this decision, the Committee must consider five factors, one of which is whether

(e) the applicant has presented clear and convincing evidence that he/she appreciates the wrongfulness of his/her prior misconduct, that he/she has manifest contrition for his/her prior professional misconduct, and has rehabilitated himself/herself from past derelictions.Footnote 111

How should the Committee approach cases where the applicant's expression of remorse did not satisfy all the elements of categorical apology?Footnote 112 One option, illustrated by the case of Doan v. Kentucky Bar Association,Footnote 113 is to consider such apology as void and without effect, reflecting an all-or-nothing understanding of infelicitous speech acts.Footnote 114 Indeed, this was the approach followed by the Kentucky Supreme Court in the case at hand. The question before the Committee was whether Doan, a disbarred attorney, was entitled to reinstatement. Doan was disbarred from the Kentucky Bar Association because of several cases of misconduct, which included misrepresenting facts to a court, fabricating documents, forging a judge's signature on a document, and misappropriating the funds of multiple clients. The Committee found that Doan should be reinstated, noting that:

Doan testified at length concerning his continued contrition and remorse. He pointed out specific instances where he had been embarrassed by his actions and the fact that people looked at him differently. He appeared to be sincere in his feelings and testimony.Footnote 115

The decision of the Committee was not approved by the Board of Governors, and Doan appealed to the Supreme Court for review. The Supreme Court denied the motion for reinstatement, stressing the imperfections in Doan's apology. In particular, the court noted that “while Doan has stated that he was responsible for what happened, he has not completely owned up to his misconduct and was vague on the details of what he had done.”Footnote 116 The court quoted a statement made by Doan in an interview with an investigator:Footnote 117

-

Investigator: Do you recall manufacturing Judge Wehr's signature?

-

Doan: No, but I may well have done it. Or someone may have done it who was under my control. So … I am not denying it.

But what if Doan's expression of remorse, or his rehabilitation process, had been somewhat closer to the ideal apology? The inferential model of graded speech acts suggests that an imperfect apology can have some of the deontic effects associated with a full apology, rather than being entirely void. Some U.S. states offer such a midway option based on the doctrine of “conditional acceptance” or “conditional reinstatement.” According to this doctrine, an applicant whose application may have otherwise been rejected may be accepted (or reinstated) into the bar through the imposition of various conditions that are relevant to the applicant's individual circumstances.Footnote 118 For example, Rule 40.075 of the Wisconsin Supreme Court states:Footnote 119

(1) Eligibility. An applicant whose record shows conduct that may otherwise warrant denial may consent to be admitted subject to certain terms and conditions set forth in a conditional admission agreement. Only an applicant whose record of conduct demonstrates documented ongoing recovery and an ability to meet the competence and character and fitness requirements set forth in SCR 40.02 may be considered for conditional admission.

Rule 25 the ABA (American Bar Association) Model Rules for Lawyer Disciplinary Enforcement states similarly (para. 9) that:Footnote 120

The court may impose conditions on a lawyer's reinstatement or readmission. The conditions shall be imposed in cases where the lawyer has met the burden of proof justifying reinstatement or readmission, but the court reasonably believes that further precautions should be taken to protect the public.

Paragraph 10 elaborates the type of conditions that can be imposed by the court, which include, for example, “limitation upon practice (to one area of law or through association with an experienced supervising lawyer)” and “monitoring of the lawyer's compliance with any other orders (such as abstinence from alcohol or drugs, or participation in alcohol or drug rehabilitation programs).”Footnote 121

V. SPEECH ACT PLURALISM AND TOLERANCE OF INCOHERENCE IN LAW AND BEYOND

I argued above that illocutionary interactions are governed by two sets of rules: a set of constitutive mapping rules, which link felicity conditions with consequences, and a set of priority rules, which resolve clashes between conflicting illocutionary claims and their supporting reasons. By rejecting the binary framework of Austin and Searle, the inferential model extends the combinatorial possibilities of linking felicity conditions with deontic effects. One of the puzzles raised by this approach concerns the coherence of the conventions governing the use of speech acts (both in law and beyond). I argue that the use of speech acts is, at least partially, incoherent. I refer to this phenomenon as speech act (or illocutionary) pluralism.Footnote 122 According to this view, illocutionary interactions are governed by multiple conventions, with potentially conflicting inferential mappings and priority rules.Footnote 123 Our use of speech acts is characterized by second-level indeterminacy: the same speech act may be invested with conflicting values of illocutionary force.Footnote 124 This second-level indeterminacy can have both diachronic and spatial manifestations. First, the use of speech acts can be diachronically (temporally) incoherent; a family may change its internal conventions regarding apology over time.Footnote 125 Second, the use of speech acts can be spatially incoherent; diverse bar admission committees may invoke different understandings of what constitutes a proper apology. Speech act pluralism can be contrasted with strong coherentism, which assumes that our use of speech acts is governed by a common set of constitutive functions and priority rules associated with different types of speech acts.Footnote 126 Robert Brandom's model of linguistic rationalism seems to lean toward this view.Footnote 127

The idea of speech act pluralism, however, faces two challenges, touching on the foundations of social communication. First, the existence of conflicting conventions regarding what constitutes an illocutionary act of a certain type can undermine our capacity to understand each other, and consequently can weaken our ability to engage in illocutionary interactions. For example, people may fail to recognize the attempt of an interlocutor to make a promise simply because they hold a different view of how to make a promise.Footnote 128 The second challenge, which received less attention in the literature, concerns the tension between incoherence and fairness. Because speech acts are associated with various deontic consequences, there is a strong social expectation that their use be governed by a principle of fairness, or nondifferential treatment.Footnote 129 When a parent apologizes to one of his children but fails to apologize to another (for a similar incident), or when a dean uses the “order” form toward one faculty member and the “request” form toward another, with regard to a similar task, they are failing this expectation. There is evidence of inequity aversion in both thinly institutionalized domains, such as the family,Footnote 130 and in more formal ones, such as organizationsFootnote 131 and the judicial system.Footnote 132 By conflicting with the expectation for fairness, incoherence in the use of speech acts can incite interpersonal frictions and undermine social trust.Footnote 133

The key to resolving both challenges lies, I argue, in the interplay between the lexical and illocutionary conventions that jointly determine the meaning of speech acts.Footnote 134 The tension between the lexical and illocutionary levels is manifested by the fact that people may use the same elementary illocutionary verbs in diverse contexts, but be subject to incompatible illocutionary conventions that diverge between use-contexts. The core elementary verbs (e.g., apologize, promise) provide the basic scaffolding for the evolution of diverse illocutionary conventions. For example, apology can be defined as an “expression of regret at having caused trouble for someone.”Footnote 135 The open-endedness of the lexical definition of apology means that the term can be associated with conflicting constitutive functions and priority rules.Footnote 136

The gap between the lexical and illocutionary conventions that govern speech acts enables society to maintain stability in the lexical (ontological) categories that are associated with distinct speech acts, while allowing meaning to be continuously adjusted through the creation of new or revised inferential links.Footnote 137 In law, these core categories manifest themselves through the emergence of a stable body of fundamental doctrinal concepts, which retain their core semantic form despite wide-ranging fluctuations in the inferential structures that undergird their application in particular cases.Footnote 138

According to speech act pluralism, illocutionary conventions may emerge as the outcome of local negotiation between interlocutors. The capacity of interlocutors to negotiate the terms of these extralinguistic conventions depends on the relative stability of the lexical-conceptual corpus. Coherence under this view is an emergent property of local communicative interactions. Uta Lenk described this negotiation process as follows:

I consider conversational coherence not as a text-inherent property, but instead as the result of a dynamic process between the participants in conversation … Through their verbal and non-verbal exchange the speaker and the hearer are engaged in a permanent, ongoing process of ‘negotiation’ of coherence. This ‘negotiation’ is achieved through mutual influencing of the participants through their contributions to the conversation.Footnote 139

The foregoing argument still leaves open the puzzle of incoherence/fairness. I argue that tolerance of incoherence constitutes an evolutionary, institutional solution to this puzzle. Below I focus on the way in which this tolerance operates in the context of common law systems, although I believe that my account is relevant also to the use of speech acts in thinly institutionalized environments. I argue that the main explanation of this phenomenon lies in the cognitive complexity of explicating the differences between the distinct inferential schemas that operate on top of the lexical core, and of elaborating how consistency can be restored. Cognitive complexity can be defined as the number of independent conceptual dimensions that the individual brings to bear in describing a particular phenomenon.Footnote 140 The gradedness of legal speech acts further increases the conceptual complexity of legal illocutionary interactions.

Consistency judgments require observers to make explicit the inferential relations and priority rules underlying the use of a particular speech act.Footnote 141 In the legal context, making a consistency judgment requires the observer to explicate the doctrinal framework used by the legal decision maker (e.g., court).Footnote 142 One of the main difficulties facing such explication is that courts may invoke the same high-level lexical concepts even when they use slightly different inferential schemas.Footnote 143 Furthermore, in many instances, courts do not fully explicate the inferential schema on which they rely. This means that the exact inferential structure of the doctrinal framework must be extracted from the ruling by juxtaposing its wording with its applicatory consequences in the case at hand.

Consider, for example, a case of two applicants for readmission to the Kentucky bar, who have both been involved in forgery of court documents and misappropriation of client funds.Footnote 144 In both cases, the applicants made a vague general statement, accepting moral responsibility for their past misconducts. Under the rules of the Supreme Court of Kentucky, to be readmitted into the bar,Footnote 145 the applicants must present clear and convincing evidence of contrition for their prior professional misconduct.Footnote 146 In the first case (case A) the Committee ruled that the applicant can be readmitted, but in the second (case B) it refused readmission, noting that the applicant's contrition has not met the standard specified by the law.

The question for an observer considering these rulings is whether the differences between the decisions are due to distinct inferential rules or to differences in the factual background of the cases. Determining whether the rulings of the Committee are coherent is made difficult by the fact that both rulings invoked the same general lexical category (contrition) but may have applied different (implicit) inferential rules. To the extent that the Committee (or any other tribunal) does not provide an explicit explanation of its reasoning, an observer must extract the inferential differences between the rulings by juxtaposing their factual basis with their deontic consequences. Consider the following options:

(1) The differences in the rulings are the product of two incoherent doctrinal structures. In case A, the Committee adopted a lenient interpretation of the contrition requirement, which does not require applicants to accept moral responsibility for each wrongdoing. In case B, the Committee adopted a strict interpretation of the contrition requirement, which requires applicants to accept causal moral responsibility for each wrongdoing.

(2) The difference in the rulings is the product of a mistaken application of the same doctrinal framework. There are two symmetrical options: (a) in both cases, the Committee adopted a lenient interpretation of the contrition requirement, and its different ruling in case B does not stem from a doctrinal shift but from a mistaken application of the rule; (b) in both cases, the Committee has adopted a strict interpretation of the contrition requirement; in this scenario, it is the ruling in case A that represents a mistaken application of the rule.

(3) There is a factual difference between the cases, which, together with an appropriately calibrated reinterpretation of the rule, can explain their apparent incompatibility. (a) Assume that the statements of the applicants in both cases, without clearly distinguishing between the two wrongdoings, differed in that applicant A clearly referred to the moral problem that underlies his behavior in both incidents (fraud) whereas applicant B did not. In case A, therefore, a factual feature (E1) was present, which did not exist in case B. It is possible to resolve the incoherence between the rulings by adding the following exception to the rule: an applicant's show of remorse is satisfactory even if it does not distinguish between the applicant's various wrongdoings, if it explicitly refers to the common moral flaw underlying his misbehavior. In this account, the presence of E1 in case A, but not in B, together with the revised interpretation of the rule, explains the divergence between the rulings. (b) The cases may differ in the applicants’ level of sincerity: applicant A being more sincere than applicant B. The difference in sincerity represents a divergent factual feature that is present in case A but not in B (E2). It is possible to resolve the incoherence between the rulings by adding a sincerity condition to the lenient interpretation of the contrition requirement. In both examples, a factual difference between the cases (E1 or E2), together with an appropriately reconstructed interpretation of the rule, can make the two decisions coherent.

It follows that an observer analyzing the coherence of the two decisions must choose between three mutually exclusive hypotheses for explaining the divergence between the decisions: (a) blunt incoherence—the different rulings in cases A and B reflect a different (implicit) doctrinal structure, hence they are incoherent; (b) labeling one of the rulings as mistaken—the Committee used the same doctrinal structure in both cases, and the different ruling in case A or B reflects a mistaken application of the rule; or (c) the difference between the rulings can be explained by a factual variable (E*) that exists in case A but not in B (together with an appropriately reconstructed interpretation of the rule).

The problem is that to the extent that (a) the Committee has used similar wording in both cases and failed to provide a complete explication of the doctrinal framework it relied on, and (b) the two cases potentially differ in multiple aspects, it will be impossible to determine which of the above hypotheses is correct. We need to collect further evidence regarding the behavior of the Committee in similar cases. To choose between the first and second interpretations (blunt conflict or misapplication), we must compare the rulings of the Committee in the two cases with its rulings in additional (relevantly) similar cases. If we find that in most of them the applicant was admitted to the bar, we can assume that the Committee has adopted a lenient interpretation (or vice versa, for the strict option). To corroborate the third interpretation, we must find another case, relevantly similar to the original one and also having the additional feature (E1 or E2). If the rulings are the same, it will strongly support the interpretation suggested above. Note that in comparing the two original rulings with a third one, it is necessary also to consider the option that the difference between the cases is due to another factual variable (E3). For example, the applicants may differ in their seniority, in the severity of the misconducts, or in the profile of the clients who were harmed by their misconduct. The presence of a third factual variable (E3) may require a different interpretation of the rule governing the applicant's contrition.

As the above example demonstrates, determining whether apparent irregularities in the use of general concepts (remorse, apology) are due to variability in the applicable doctrinal frameworks or in the underlying social data is made difficult by the fact that courts do not always fully explain the inferential structure on which they base their ruling.Footnote 147 The appearance of univocality produced by the fact that courts invoke the same conceptual apparatus even when they apply different inferential rules could have been resolved if distinct inferential rules had been associated with distinct lexical terms (e.g., apology1, apology2, apology3), but this sort of conceptual exactness is rather rare.Footnote 148

The cognitive difficulty of identifying inconsistency is exacerbated by the fact that observers do not usually have complete access to the evidentiary data of the projected set of “similar cases.” As I showed above, without access to this data, it is difficult to challenge the presumption, based on the univocality of the lexical core, that the differences in the use of speech acts are due to factual variations rather than to conflicting inferential conventions.Footnote 149 For example, suppose we suspect that one bar committee has adopted a criterion that categorically rejects apologies made by transgender people (what Rebecca Kukla described as cases of discursive injustice).Footnote 150 Such a felicity condition is, naturally, morally problematic. But before we can criticize the Committee for adopting such a morally problematic approach, we must be convinced that the decision of the Committee was not due to some other case characteristics that are correlated with gender identity (e.g., results of bar examinations or criminal history).Footnote 151

Finally, even if observers can accurately articulate the second-order indeterminacy that characterizes the doctrinal space, restoring coherence is in itself a nontrivial challenge. This difficulty is relevant both for decision makers and for third parties that have an interest in facilitating legal coherence. Coherence can be restored by singling out one of the competing interpretations as the correct one, by replacing the conflicting interpretations with a new one, or by partitioning the legal space by coining new legal concepts, each associated with a different inferential mappings.Footnote 152 Choosing between these multiple options is a cognitively complex task, which raises difficult meta-normative questions.

Up to this point, I focused on the cognitive aspects of tolerance of inconsistency. This is a general issue, not unique to the legal domain.Footnote 153 The evolution and persistence of tolerance of incoherence in the legal system is reinforced by the diverse institutionalized incentives of legal actors. Laypeople do not possess the analytical know-how to make judgments about legal consistency. Legal professionals are in a better position to identify incoherence. But their incentives are not necessarily aligned with the goal of restoring coherence. The behavior of lawyers is heavily influenced by their financial interests. It seems highly unlikely that their interests would align perfectly with either those of their clientsFootnote 154 or of the legal system (restoring coherence).Footnote 155

The incentives of judges, in both lower and higher courts, are also not entirely aligned with the goal of achieving perfect coherence. Empirical studies of judicial behavior suggest that judges’ rulings may be influenced by various extralegal considerations, such as their ideological preferences, or by strategic considerations (the need to take into account their colleagues’ policy preferences or the possibility of legislative reprisal).Footnote 156 The opacity of legal language enables judges to conceal the influence of these extralegal motivations. Barry Friedman described one aspect of this phenomenon using the idea of “stealth overruling”: “the ability of justices to either diverge or overrule (in the case of the Supreme Court) precedents, while hiding the fact that they are doing so.”Footnote 157 Furthermore, because of the enormous caseload that courts face, only a fraction of lawsuits end in a full trial, and many disputes are resolved by settlement (the “vanishing trial” phenomenon). This phenomenon limits the capacity of case law to weed out incoherence through deliberative refinement.Footnote 158

It may be tempting to think that legislators and academics would be better positioned to act as guardians of legal coherence. But both face various constraints that prevent them from assuming this role. The need to make various political compromises to allow certain legislation to move ahead undermines the capacity of the legislative process to achieve coherence. In a fascinating study of the legislative drafting process in the U.S. Congress, Abbe Gluck and Lisa Bressman have demonstrated this phenomenon. They noted that although more than 93 percent of their respondents (congressional staffers) affirmed “that the ‘goal’ is for statutory terms to have consistent meanings throughout,” the staffers have also emphasized the significant organizational barriers that the committee system, bundled legislative deals, and lengthy, multidrafter statutes pose to the realization of that goal.Footnote 159

Changes in legal scholarship have significantly weakened the role played by legal academia in promoting the coherence of the law. Traditionally, legal scholarship has focused on doctrinal questions (studying the consistency of the use of concepts in different areas of law, exploring how different legal concepts can fit together, and extracting general principles from the existing body of law). The following quote from Lord Goff captures the spirit of traditional doctrinal legal research:

The prime task of the jurist is to take the cases and statutes which provide the raw material of the law on any particular topic; and, by a critical re-appraisal of that raw material, to build up a systematic statement of the law on the relevant topic in a coherent form, often combined with proposals of how the law can beneficially be developed in the future.Footnote 160

Contemporary legal scholarship, however, has changed its nature. Current legal research is less interested in exploring purely doctrinal questions and focuses more on studying legal questions from a theoretical perspective, drawing on interdisciplinary insights from diverse fields.Footnote 161 Improving legal coherence is not part of this research agenda.

The institutional structure of the law thus contributes to the persistence of tolerance of incoherence,Footnote 162 which enables the law to maintain a facade of consistency at the top level of general concepts, while allowing meaning to fluctuate at the level of particular cases. I believe that this paradoxical situation contributes to the resilience of the law. First, it allows the legal system to economize on the costs of establishing a fully consistent doctrinal space. Second, tolerance of incoherence provides the law with the capacity to navigate the conflicting demands and expectations of diverse communities and subcultures, without undermining its claim for impartiality.Footnote 163 Sensitivity to cultural pluralism is incompatible with consistency, because achieving consistency may come at the expense of particularistic moral or cultural points of view, and may require us to abandon one of the irreducibly independent principles at the foundation of modern culture.Footnote 164 As Christopher Kutz has argued, “ineradicable conflict and divergence in a complex legal system is not a sign that things have gone awry, but that things are going well, that the legal regime is taking seriously plural claims of value.”Footnote 165

From a moral perspective, tolerance of incoherence is compatible with the idea of moral relativism, and with the position that we should tolerate, to some extent, those with whom we morally disagree.Footnote 166 Recently, Richmond Campbell and Victor KumarFootnote 167 have outlined a different approach, by arguing that moral consistency reasoning operates as a distinctive form of moral reasoning that exposes inconsistencies between moral judgments and thus plays an important role in shaping moral thought and in driving moral progress. The idea of tolerance of inconsistency suggests, however, that moral inconsistency may be more prevalent and exhibit stronger stickiness than is suggested by Campbell and Kumar. Their work underestimates, in my opinion, the cognitive complexity underlying consistency judgments. Tolerance of inconsistency does, however, come at a price by allowing morally problematic practices to persist. In the case of apologies, for example, legal parties have recently begun to exploit the ambiguities of apologetic language to their advantage, adopting a thin interpretation of apology that does not include an admission of fault or a commitment for redress.Footnote 168 Using the notion of apology, while implicitly weakening its felicity criteria, can serve the interests of wrongdoers, particularly in the field of medical malpractice, by putting pressure on victims to settle for less than fair compensation.Footnote 169

Tolerance of incoherence is therefore a deep-seated feature of the law. Law is, in that sense, intrinsically and inescapably imperfect.

APPENDIX A

TYPES OF ATTENUATION MECHANISMS: ILLUSTRATIVE TABLE