Introduction

A native product of the Amazon forest, cacao became the most important staple of the Portuguese Amazonian colonial economy during the late seventeenth and up until the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 1 From the second half of the seventeenth century onwards, when chocolate consumption in Europe began to increase,Footnote 2 and influenced by the experience of the Spanish colony of Caracas (Venezuela),Footnote 3 the Portuguese Crown decided to spur on cacao exploitation and cultivation in the region. This momentum was most likely motivated by news sent from the Amazon region which indicated the commercial potential of cacao production.Footnote 4 The process began with incentives for cacao cultivation – the cacau manso – and continued by encouraging cacao exploitation in the vast Amazonian hinterland (sertão; plural sertões), through the gathering of wild fruits – the cacau bravo.

Based on extensive research in Brazilian and European archives, this article analyses cacao exploitation in Portuguese Amazonia.Footnote 5 The article examines the double spatial dimension of the cacao economy in the Amazon region – one related to the expansion of an agricultural frontier, and the other to the expansion of an extractive frontier in the remote hinterland – and the role that Indigenous labour played in the development of cacao exploitation.

The text deals with a period spanning from the late seventeenth century up until the mid-eighteenth century. It was only in the 1680s and especially from the 1690s onwards that cacao exploitation thrived, and this success resulted especially from strong economic policies issued by the Crown.Footnote 6 Cacao exploitation and exportation increased throughout the eighteenth century, especially after the 1720s when, according to Dauril Alden, the product eventually found a ‘dependable market’ due to the popularisation of cacao consumption in Europe.Footnote 7

We argue here that throughout the late seventeenth and first half of the eighteenth century, owing especially to cacao exploitation, a specific pattern of economic exploitation developed in the Portuguese Amazon region. This mode of production would undergo changes in the mid-eighteenth century, when the Crown abolished Indigenous slavery and secularised missionary villages. However, we argue that the combination of agriculture and extractive industry, as well as a significant quantity of native labour (whether enslaved, forced and/or tethered to missionary activities), became the basis of an economic system that would exist in the Amazon region throughout the colonial period. Thus, the exploitation of this colonial commodity would rely on both agriculture and extraction. Moreover, the exploitation of this staple, which was sent to the European markets, would rely on the intensive use of many forms of Indian labour.

Despite the importance of this period to the understanding of colonial Amazonia, the late seventeenth and the mid-eighteenth century in the economic history of the Amazon region have been neglected by historiography. Portuguese and Brazilian literature has presented the second half of the eighteenth century as a milestone. This is largely because the period marked the beginning of Dom José's reign (1750–77) and the ascent of his powerful minister, Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, known as the Marquis of Pombal. Although historiography has overstressed the extent of his reform policies in Amazonia, the year 1755 represented a change for commerce. During this year the Crown installed a monopoly trade company – the Companhia Geral do Grão-Pará e Maranhão – which lasted until 1778, a few months after Pombal fell into disgrace.Footnote 8 This trade company enjoyed the monopoly over Amazonian products traded to Portugal (especially cacao) and was obliged to deliver African slaves on a regular basis in order to foster agriculture.Footnote 9 Even though the amount of cacao production did not necessarily increase, the institution of the trade company did alter the Portuguese mercantile circuits within which cacao was traded into Portugal and reexported to other countries on the European continent.Footnote 10

Owing to their disconnection from the major Atlantic economic circuits as articulated in historiography (those which linked the American colonies to the African continent), seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Amazonian cacao production and trade within the Portuguese empire has been almost completely ignored by Luso-Brazilian scholars. One could argue that the cacao economy was sidelined by the centrality of African slavery and the African slave trade in the explanation of the colonisation of Portuguese America as a whole.Footnote 11 Except for the works of Manuel Nunes Dias, António Carreira and notably Dauril Alden, not much attention has been directed towards this commodity in Luso-Brazilian historiography.Footnote 12 These scholars, however, concentrated more on trade and less on local production (especially cultivation) and labour. Nunes Dias and Carreira analysed only the period of the second half of the eighteenth century.

Yet cacao was an important commodity in the Early Modern global economy. It was produced in many American colonies – in Central America, Ecuador, the Caribbean and Venezuela.Footnote 13 It was traded between Spanish American colonies (Mexico being an important market) and extensively exported to Europe.Footnote 14 Its main product, chocolate, was widely consumed in colonial Mexico and was slowly incorporated into the European diet, through a complex process of transformation of its original (i.e. American) forms of consumption.Footnote 15

Beyond a focus on trade and consumption, one has also to look at this colonial product from the viewpoint of the social and spatial dynamics that its economic exploitation gave rise to. In fact, the development of cacao exploitation had a territorial importance for the Portuguese dominion, not only in the vast Amazonian hinterland, but also in the areas around the main Portuguese urban centres of the region. Moreover, as mentioned above, in contrast to other cacao economies in the colonial Americas (Central America, Ecuador and Venezuela), in the Portuguese Amazon its exploitation, both in the sertões and on cultivated plots, depended almost exclusively on an Indigenous labour force, at least until the late eighteenth century. This means that one cannot ignore the role played by native compulsory work in the constitution of Atlantic economies, which has usually been associated only with the African slave trade and plantation system.

Elucidating the importance of Amazonian cacao in Early Modern colonisation, this text is divided into four parts. First, we will examine cacao production in the Amazon region, both in the cultivated areas and in the sertões. Secondly, we will analyse the expansion of the Amazonian cacao economy in the late seventeenth century and first decades of the eighteenth century. Thirdly, we will analyse the relationship of labour force to cacao production. And finally, we will examine Jesuit production, in view of the fact that the Society of Jesus had privileged access to an Indigenous labour force and was frequently accused of prospering owing to its economic activities, which included cacao exploitation.

Cacau Manso and Cacau Bravo

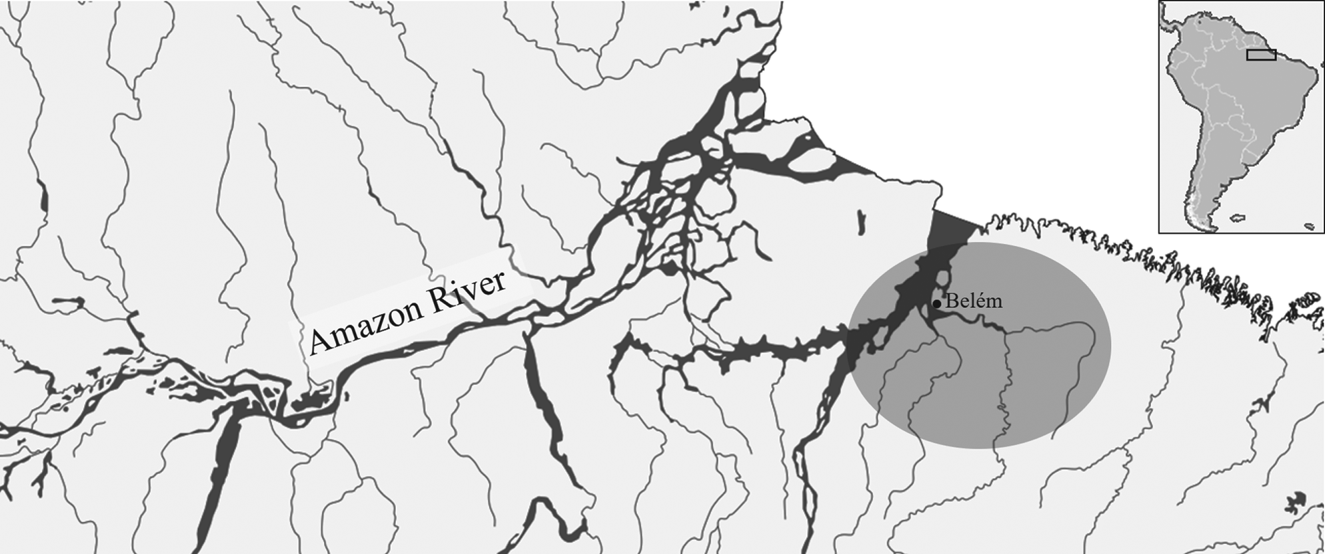

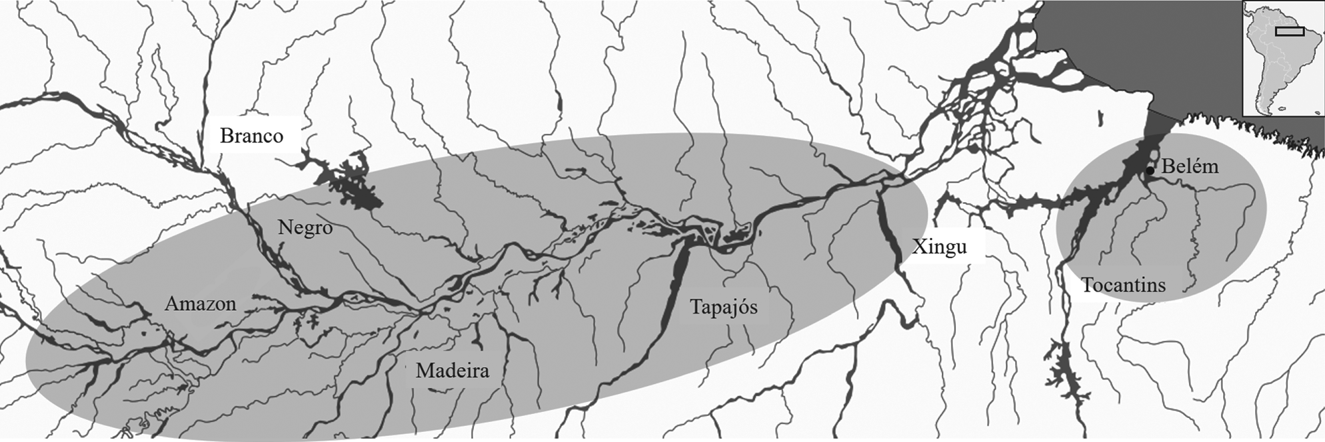

Throughout the late seventeenth and first half of the eighteenth century, settlers cultivated cacao on estates in the Amazon delta, mainly on the banks of the rivers surrounding the city of Belém. Thus, an agricultural zone strongly embedded in the complex Amazonian fluvial dynamic zone began to emerge from the late seventeenth century onwards (Figure 1). This late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century agricultural region, surprisingly, has been almost completely ignored by historiography. Scholars including Dauril Alden, who authored a pioneering work on cacao,Footnote 16 tend to stress the existence of agricultural development only from the second half of the eighteenth century.

Figure 1. Agricultural region, late seventeenth to mid-eighteenth century (shaded)

Source: Authors’ elaboration from: mapas.mma.gov.br/i3geo.

Officially, colonial governors made grants of land (sesmarias) on behalf of the king, and the settlers had to demand royal confirmation of the concession. Most of these lands had been occupied by Portuguese colonisers from the 1690s onwards. Thus many settlers demanded concessions for plots that they were already cultivating. In general, all over Portuguese America, tenure of the land and its obligatory economic exploitation became the main arguments for the concession of land grants.Footnote 17 The expressions ‘possessing and cultivating’, or simply ‘cultivating’, were common in petitions.

In 1703, for example, Teresa de Melo Maciel claimed that she had been living off her cultivation of food crops and cacao ‘for more than 14 years’, and presented this as the reason why she had asked for royal confirmation of her lands.Footnote 18 That same year, Manuel Lopes Reis demanded confirmation of the lands he had occupied ten years earlier and on which he had planted 3,000 cacao trees.Footnote 19 In 1714, Felipe Marinho stated in his plea that for more than 15 years he had been cultivating his lands with cacao and annatto.Footnote 20

Usually, planters cultivated several crops. Many of these are impossible to identify, since the documents refer solely to lavouras and roças, which meant lands devoted to agricultural activities. In the case of the colonial Amazon, these terms probably indicated the cultivation of manioc (the primary starch-rich food of Portuguese America adapted from Indigenous agriculture) and other common subsistence crops (mantimentos). Thus, in 1702, one could find sugar cane (for a still), cacao and some cattle on the lands of Mateus de Carvalho e Siqueira.Footnote 21 In 1721, Domingos de Araújo and Inácio Marques stated that they cultivated manioc as well as 5,000 trees of cacao.Footnote 22

The Crown's effort to promote a cacao ‘industry’ in the Amazon met with some success. Many of the settlers explicitly stated they were ‘planting’ or ‘cultivating’ cacao on their lands. Moreover, the use of the words cacaual (cacao orchard) and fazenda (farm) of cacao in the land grants indicates the existence of concentrated cultivation of cacao, differing from the exploitation of ‘wild cacao’ found in the sertão.

Unfortunately, there is no indication in the documents whether the varieties cultivated and gathered in the hinterland were different or the same. It is also difficult to tell whether the beans gathered along the different rivers in the vast region of the Amazon came from the same varieties. Nevertheless, since gathering and planting (which were different economic activities) were undertaken in diverse regions and on different soils one can assume that the cacao beans came from different varieties or at least had different qualities.

During the period from the mid-1690s until the mid-1750s, we find reference to 893 land grants distributed by governors among the settlers in the captaincy of Pará.Footnote 23 Almost 28 per cent of the land grants (249) mention the cultivation of cacao (as well as other cultivated products). From the details of those grants in which crops were mentioned we learn that, compared to other products cited in the grants, cacao was by and large the most frequently quoted. As mentioned before, cacao was not the only cultivated product declared in the land grants. In colonial Amazonia, at least until the late eighteenth century, no settler cultivated one crop to the exclusion of all others. Moreover, although barely cited, manioc was omnipresent.

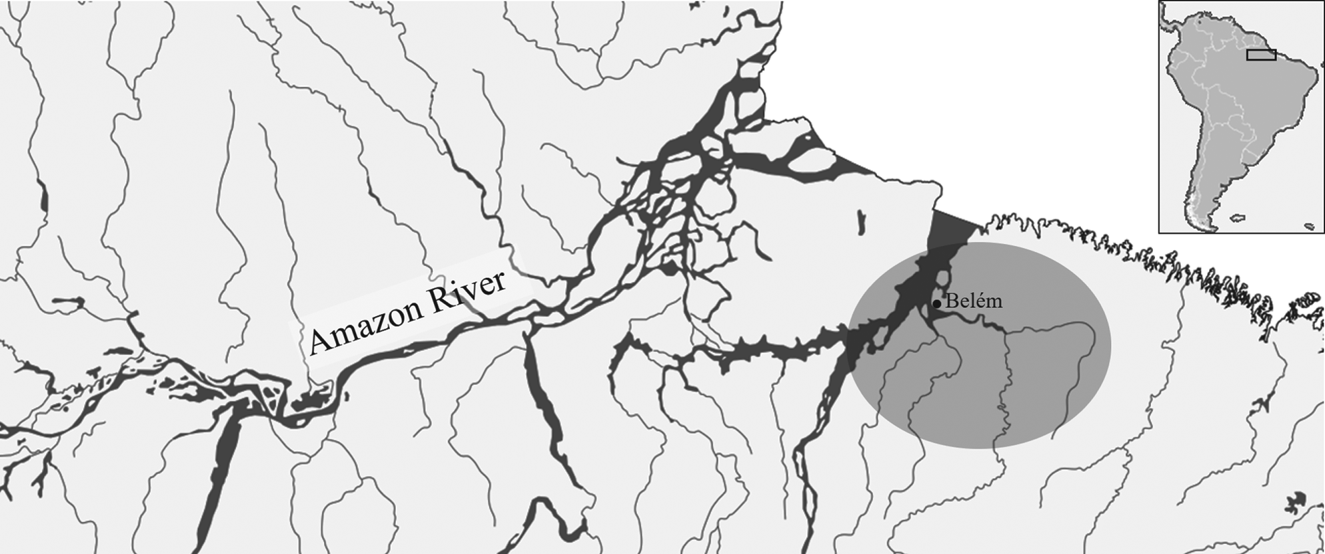

From the data related to the land grants, one can infer the strong influence that the city of Belém had in cacao cultivation. Of the 218 settlers who were already planting or who intended to cultivate cacao, 70 per cent declared living in the city of Belém. Moreover, the location of the grants indicates the importance for cacao cultivation of the river network that surrounds the city of Belém. The main rivers – the Guamá, Guajará, Capim, Moju and Acará – and some of their tributaries – such as the Irituia, Caraparu, Genipaúba, Itapecuru, Inhangapi – became a centre of cacao cultivation until the mid-eighteenth century (see Figure 2).Footnote 24

Figure 2. Main rivers with cacao cultivation

Source: Authors’ elaboration from: mapas.mma.gov.br/i3geo.

There is no certainty whatsoever as to the quantities of cultivated cacao that were represented in the region's exports. Unfortunately, sources do not differentiate cultivated cacao from fruits simply gathered in the forest, the cacau bravo. Explicit reference to the number of trees cultivated in some of the land grants and other documents come together to produce a total of 342,100 cacao trees cultivated by settlers (data from 1700 to 1750), distributed among 41 settlers. However, this was not a homogeneous scenario. There were people, such as Francisco Cordovil (1734) and Feliciano Primo dos Santos (1740), who cultivated 1000 trees, and Luís Faria Esteves (1714) and José de Silveira Goulart (1729), who had 21,800 and 36,000 trees, respectively.Footnote 25

Compared to Caracas production, for example, the Portuguese Amazon region did not represent an impressive number, at least if we count only those trees explicitly mentioned by settlers (the 342,100 trees mentioned above). According to data gathered by Robert Ferry, Caracas Province cacao cultivation increased from 434,850 trees in 1684 to 3,251,700 trees in 1720, reaching just over five million trees in 1744.Footnote 26 However, if we consider an average of 8,140 trees per grant (based on the numbers mentioned in the sesmarias),Footnote 27 and multiply them by the total of the land grants which explicitly mentioned cacao (including those settlers who intended to begin their plantations and those who already had plantations but did not provide the number of trees), we reach a final number of just over two million cacao trees, 40 per cent of Caracas’ production in the mid-eighteenth century.Footnote 28

As already pointed out, however, cultivation was not the only way of exploiting cacao in the Portuguese Amazon region. The gathering of wild cacao fruits by settlers and clerics was still a very important practice throughout the seventeenth and early eighteenth century. Unfortunately, data concerning cacao gathering remain scarce and fragmented. A registry of the Royal Treasury of Pará, between 1700 and 1702 – the only systematic series for the Treasury – indicates that, in this period, 226 boats (canoas) went into the sertão to gather cacao and clove bark,Footnote 29 each boat paying the relevant taxes to the Treasury officials.Footnote 30 In 1729, Governor Alexandre de Sousa Freire (1728–32) indicated in a letter to the king that he had sent 112 canoas into the sertão for the gathering of cacao and clove bark. Winter (i.e. the rainy season), however, had been so harsh that their yield was disappointing.Footnote 31 A register in 1738 indicates that, from October to December 1738, 101 canoas were sent into the sertões for the ‘gathering’ (colheita), as reported in the document.Footnote 32 The rainy season (starting in October/November) determined the beginning of the expeditions into the sertões for the gathering of wild products, such as cacao, clove bark and sarsaparilla.Footnote 33

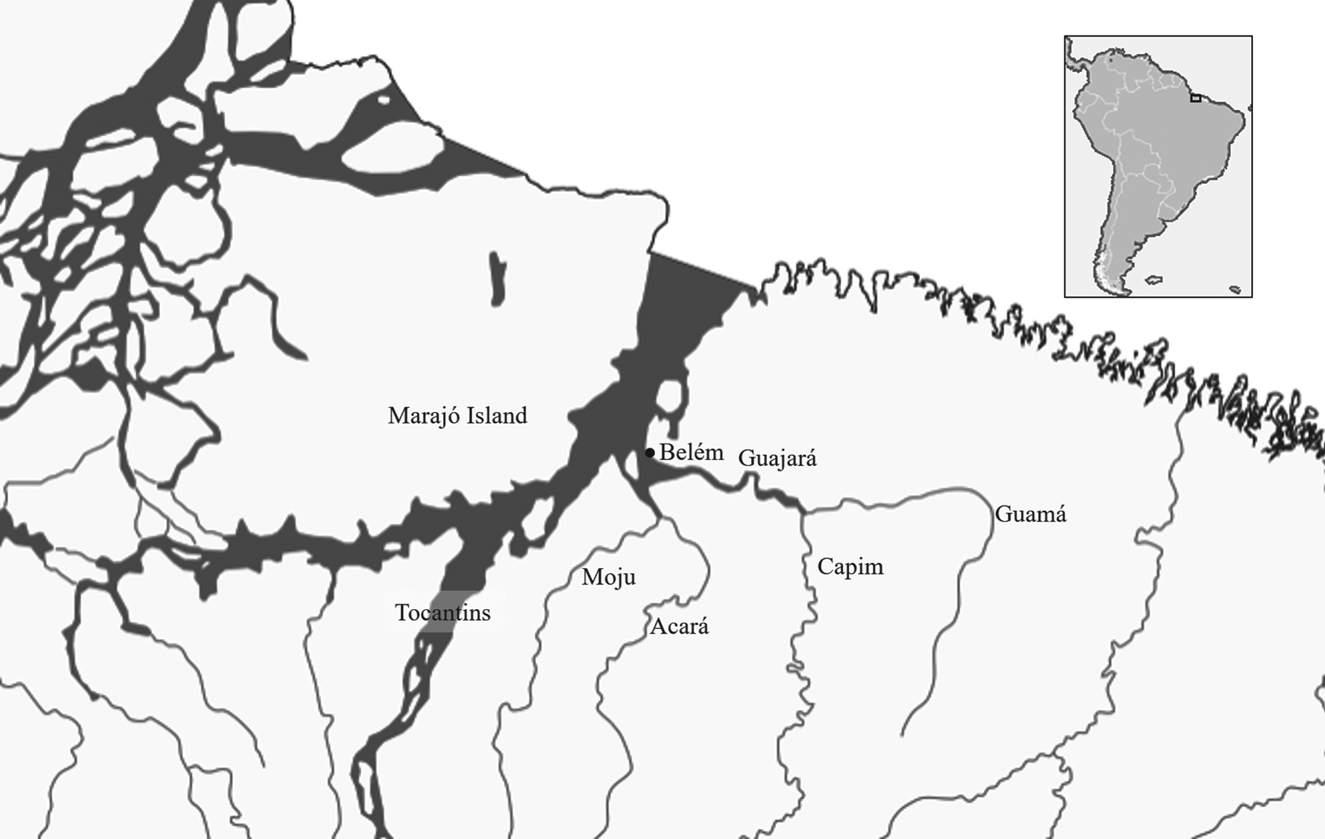

From the late seventeenth century and onwards, the Crown attempted to tighten control over the canoas travelling into the sertão, as the journey could lead to the illegal enslavement of Indians. Thus, cacao gathering and enslavement (legal or illegal) were not necessarily seen as mutually exclusive activities, as both practices took place in the remote hinterland. This was the reason why, in 1688, the king confirmed an order issued two years earlier by Governor Gomes Freire de Andrade, who compelled those who went into the sertão to register their canoas at the Gurupá fortress (see Figure 3).Footnote 34

Figure 3. The cacao sertões (shaded)

Source: Authors’ elaboration from: mapas.mma.gov.br/i3geo.

According to seventeenth- and eighteenth-century sources, native cacao was most present and concentrated on the Amazon river and some of its tributaries. Judge Maurício de Heriarte states that, downstream of the Negro River, there was ‘a lot of cacao’, which Indians used to prepare ‘a wine for their drunkenness’.Footnote 35 The Jesuit Father João Daniel, who lived in the Amazon region in the 1740s and 1750s, also mentioned cacao growing around the Madeira river and all of the rivers that drained into the Amazon below it.Footnote 36 The abundance of wild cacao in the Madeira river region had already been noticed by Jesuit Father João Felipe Bettendorff at the end of the seventeenth century.Footnote 37 In the second half of the eighteenth century, Vicar-General José Monteiro de Noronha referred to the abundance of cacao along the Amazon river and some of its tributaries above and below its confluence with the Negro river, and on the archipelago between the great island of Marajó and the northern shore of the Amazon river (see Figure 3).Footnote 38

In the late 1720s and early 1730s, data from the missionary orders’ estates (in the agricultural region near Belém) and Indian villages (in the remote hinterland) indicate that, at least for some clerics, wild cacao was exploited much more frequently than the cultivated version. One should stress, however, that the clerics could count on the labour of the many Indians from the missionary villages that they administered in the sertões. In fact, the Jesuits’ plantations produced only 5.8 per cent of the total amount of goods generated by the Society of Jesus in the Amazon region. In the case of the Carmelites, cultivated cacao comprised only 9.5 per cent of their Amazonian production.Footnote 39 For the religious orders, gathering was far more important than cultivation.

The Expansion of Cacao

Several sources reveal evidence of the expansion in cacao exploitation, which took place at the same time as an increase in cacao prices in the first decades of the eighteenth century.Footnote 40 Letters written from the Court to royal authorities in the Amazon region and from there back to Lisbon indicate a growing interest in cacao exploitation, most notably after the 1720s.

As early as 1721, the king commanded Governor Bernardo Pereira de Berredo (1718–22) to send samples of Amazonian cacao to the island of Príncipe, off the African coast. He had been informed that cacao could yield in ‘great abundance’ there.Footnote 41 In an interesting case of intercolonial exchange,Footnote 42 this order was reinstated several times in subsequent years, notably after the mid-1720s, a sign that the Portuguese Crown was aware of the importance of cacao in European trade.Footnote 43

In 1724, the king instructed Governor João da Maia da Gama (1722–8) to pay close attention to the production of local cacao, in order to achieve a quality ‘similar to that of Caracas’, so that it could fetch a ‘better price’.Footnote 44 A letter written by Governor João de Abreu de Castelo Branco in 1737 referred to the very first attempts at cacao cultivation in the Amazon region, in the late seventeenth century. He explicitly mentioned that it was from 1725 onwards that Governor Maia da Gama ‘encouraging planters, promoted this cultivation’, which was now widespread among settlers. He added that the ‘change in the price of cacao’ had positively contributed to this situation.Footnote 45

The impression of a cacao boom can be grasped from a series of manuscripts carrying news that were written in the city of Lisbon, in Portugal, between 1729 and 1734. In several short notes, the writer(s) mentioned the arrival of a number of ships from the Amazon region laden with cacao: 75,000 arrobas (1100 metric tonnes), ‘which were sold for a high price’, in December 1730.Footnote 46 We also hear of a ship which had been separated from the rest of the convoy, with a cargo of cacao, which ‘will be of most importance, owing to the price of cacao, that increased because of the loss of the [Spanish] Indies fleet’, in December 1733.Footnote 47 In the early 1740s, French scientist and explorer Charles-Marie de La Condamine also stressed the ‘direct trade’ between the Portuguese inhabitants of Pará and Portugal: this comprised ‘many useful products’ including clove bark, sarsaparilla, vanilla, sugar, coffee and ‘especially cacao, which serves as money in the land, and makes rich its inhabitants’.Footnote 48

The religious orders also encouraged the expansion of cacao beyond the boundaries of the Portuguese colony. Thus, Louis de Villette, the Jesuit Superior of Cayenne, the French possession to the north, wrote in 1733 to his confrère José Lopes in Belém to reveal that ‘we have planted a great number of cacao trees. I myself have planted about 25,000, of which only very few produced fruits.’Footnote 49

Data for cultivated cacao confirm the impression of a cacao boom. There was an increase in terrain dedicated to cacao cultivation after the 1720s: of the lands granted for its cultivation, almost 70 per cent were given after 1721. Moreover, the number of settlers claiming new and unoccupied lands for the planting of the fruit increased fivefold from the 1720s, and remained noticeably high up to 1740. This was a clear sign that the Crown's efforts to boost cacao cultivation were meeting with some success, as mentioned in 1737 by Governor Castelo Branco (see above).

Regarding the wild cacao that was gathered in the hinterland, from the late 1720s the royal authorities reinstated and tightened former orders regarding the expedition of canoas to the sertão, issued in 1688, as mentioned above. The concerns of the Crown and the royal authorities had a dual nature.

In the first place, journeys to the hinterland, although officially for the gathering of wild forest products, could lead to unlawful enslavement, since the expeditions which went to the sertão for cacao could be diverted to the illegal capture of Indians. This apprehension was evident in 1728 when Governor Alexandre de Sousa Freire reinstated the royal decree of 1688, which he decided to ‘ratify’ by issuing a new order. This new bando explicitly stated that ‘no one who goes upstream into the sertão to extract those mentioned goods [cacao and clove bark] can ransom slaves [from Indigenous groups], without a special order’.Footnote 50 Even the legal use of free Indians from the missionary villages for the gathering of forest products became a concern. In fact, the same governor issued a second edict ordering the immediate restitution to the missionary villages of the Indians distributed among those settlers who went ‘into the sertão to gather cacao and other products’.Footnote 51

Secondly, royal authorities and councils were particularly concerned by the extensive exploitation of wild cacao and other products. In 1738, ten years after the orders issued by Governor Sousa Freire, Portugal's Overseas Council debated a letter from the judge of the captaincy of Pará, Manuel Antonio da Fonseca. The judge condemned the ‘liberality’ with which governors granted licences to settlers to go into the sertão to gather ‘drugs and goods [gêneros]’. He asserted that 250 canoas had previously entered the hinterland, each with a crew of 20 to 25 Indians. He furthermore complained that in 1736 (when the letter was written), more than 320 canoas went into the hinterland, causing the ‘destruction of the cacauais [here, wild cacao orchards]’. Besides the general concerns around the excessive exploitation of the Indians from the missionary villages, the members of the Belém city council and the royal counsellor in Lisbon – in this following the worries of Judge Fonseca – feared the ‘excess of those who not only destroy most of those Indians, but also the fruits, gathered unripe and out of their season, with serious harm to trade’.Footnote 52 Even if one has to take Fonseca's words with caution, owing to the frequent clashes between royal authorities, these letters and official decrees seem to indicate a considerable increase in cacao exploitation in the sertões from the 1720s onwards, contemporary with that in cacao planting in the surroundings of Belém.

Royal tithes also reveal a general increase in production: during the first half of the eighteenth century, they grew steadily in the captaincy of Pará. In 1697, tithes resulted in the sum of 24,000 cruzados,Footnote 53 in 1706 they amounted to 37,000 cruzados. Sums more than tripled between 1731 and 1734, and almost doubled in 1748.Footnote 54 This increase confirms the growth in the cacao economy. Since the religious orders, especially the Jesuits, routinely avoided the payment of the tithes by insisting on their tax-exempt status,Footnote 55 these sums can be interpreted as an indication of the settlers’ exploitation of cacao, both on their own lands and in the hinterland.

Cacao was widely exported to Portugal, where it was consumed or reexported to other European countries. We find only crude export data for the period from 1730 onwards. Yet scattered documents show that cacao arrived in Lisbon before this time period, for example the 261 arrobas of cacao (almost 4 metric tonnes) traded by Gaspar Dias de Almeida, in 1715. We can similarly mention the 250 arrobas of cacao (3.6 metric tonnes) bought by Simão da Silva Rebelo in 1718.Footnote 56 From 1730 until 1755, the Amazon region exported an average of 42,000 arrobas annually (617.4 metric tonnes), although shipments were highly irregular.Footnote 57 During the functioning of the Companhia Geral do Grão-Pará e Maranhão (1755–78) average exports did not increase (38,000 arrobas yearly, or 560.3 metric tonnes).Footnote 58 It was only at the end of the eighteenth and in the early nineteenth centuries that cacao exports rose significantly, as Dauril Alden has already pointed out and as indicated so clearly by the Portuguese trade balances (a yearly average of 113,000 arrobas, or 1600 metric tonnes, between 1796 and 1806).Footnote 59

Although Portuguese Amazonia did not become one of the most important producers in the world, cacao from this region was known as ‘cacao from Maranhão’, perhaps related to the fact that it was a different variety. In the list of goods for which taxes were paid at the customs in Bahia, for example, we find explicit mention of ‘cacau do Maranhão’.Footnote 60 In the registers of one of the Lisbon customs houses (the Casa da Índia, where cacao was taxed), one can find mention of ‘cacau de Caracas’, ‘cacau de Índias’ (both meaning cacao from the Spanish colonies), and ‘cacau do Maranhão’.Footnote 61 Customs officials at the French port of Bayonne mention ‘cacao de Maraignon’ in the late 1740s and early 1750s.Footnote 62 In December 1755, the port of Genoa registered the arrival of ‘caccao di Maraglie’ from Lisbon.Footnote 63

Labour Force

The expansion of the cacao economy required labourers. In the Amazon region, however, contrary to many of the cacao plantations of Spanish America, the majority of these workers did not come from Africa. Instead, the growth of the Amazonian economy, owing to the intensification of cacao exploitation both in the hinterland and on cultivated lands, was intertwined with the (legal and illegal) Indian slave trade as well as with an intricate forced work system based on free Indians.

The use of Indians as the main labour force for the gathering and cultivation of cacao in the Amazon valley evokes the complex and intensely discussed question of Indigenous peoples as, in Paul Cohen's words, ‘Atlantic actors who have been largely, although not entirely, absent from Atlantic history’. An Amerindian Atlantic history (as he calls it) could ‘reconstruct the commercial relationships which Amerindians brokered with Europeans and settlers, and which in turn drew American commodities into the Atlantic exchange’, especially through less European-centred studies. Thus, Atlantic history ‘“needs” to include Amerindians to achieve the ecumenical objectives of its practitioners’. Cohen's reflexion, although entirely based on North American historiography and samples,Footnote 64 is fully applicable to the Portuguese colony on the Amazon, where natural resources were extracted and colonial structures imposed simultaneously with and against the native peoples.

In the Portuguese Amazon region, Indigenous labour, both free and slave, was a complex and complicated issue that mobilised the Crown, the colonial authorities (lay and ecclesiastical), the settlers, the missionaries, and, of course, the Indians themselves, who had their own agenda when taking part in expeditions or cultivating the settlers’ plots.Footnote 65 On the Portuguese side, it was not the legitimacy of Indian slavery – officially allowed only in certain circumstances – but its interpretation and regulation that constantly placed different colonial agents in opposition with each other.Footnote 66

Even if the Crown tried insistently to prevent settlers and even officials from unlawfully enslaving Indians in the hinterland, illegal seizure was a common practice during the whole period. Unfortunately, for the late seventeenth and the first half of the eighteenth centuries there is no way of quantifying enslavement (legal or illegal) or the use of free Indigenous labourers with any reliability. Nevertheless, at the end of the seventeenth century, Judge Miguel da Rosa Pimentel accused settlers of behaving like ‘rulers of the sertão’ after passing the control post at the fortress of Gurupá (see Figure 3), mistreating and enslaving the Indians indiscriminately.Footnote 67 Previously, the governor had explicitly stated to the Overseas Council that he had decided not to punish those involved in illegal enslavement, since he had found out that virtually all of the settlers were involved, and so punishment could ‘devastate the whole colony’.Footnote 68 A year later, the king himself issued a general pardon to the settlers, directing, nevertheless, that all Indians enslaved against his laws were to be considered free (although the authorities had to send the freed slaves to the missionary villages, rather than back to their own original communities).Footnote 69 Unfortunately, there is no proof whatsoever of compliance with this royal order.

Regarding the free Indigenous labour force, from the mid-sixteenth century the Portuguese in Brazil adopted a system of conversion to Christianity which compelled the Indians to settle in specific villages, known as aldeias, conceived for this purpose. Besides receiving regular indoctrination, the natives were forced to work for the settlers, the Crown and the Fathers themselves, although preserving at least officially their ‘free’ status.Footnote 70 This was the basis of a system of native labour that was adopted a century later in the Amazon region.

Because the Indians formed the main source of labour throughout the colonial period in the State of Maranhão and Pará, the use of natives living in the missionary villages would become a bone of contention. Although the settlers, clerics and the Crown did not dispute the legitimacy of Indian forced labour, they constantly disagreed over its regulation and implementation. A considerable part of legislation in the State of Maranhão and Pará in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries concerned the work of those who were considered to be ‘free Indians’. The fact that the latter were under the guardianship of the religious orders, especially Jesuits and Franciscans, made it difficult for settlers and the religious orders to reach an agreement over the Indigenous workforce.Footnote 71 One of the most controversial issues was the annual distribution of Indigenous labourers from the missionary villages to the settlers, which had been determined in 1686.Footnote 72 Of special concern for the religious orders was the proportion of individuals to be distributed (usually, a third of the mission's adult male population), and the time that they spent working for the settlers (up to six months), as defined by law.Footnote 73

The expansion of the frontiers (both agricultural and external) of Amazonian society and Portuguese dominion from the late seventeenth century onwards had a strong influence on both the slave and the free Indigenous labour systems. In fact, like cacao, Amazonian Indian slaves and free Indians were to be found in the remote hinterland. The advance of territorial occupation meant not only an increase in settlement, but also the exploration of new sertões in the search of: 1) more Amazonian spices, such as cacao, clove bark, sarsaparilla and copaiba balm; 2) native prisoners, purchased from different Indigenous groups, captured in authorised wars or simply illegally enslaved; and 3) free Indians, who were brought from the hinterland to the mission villages and governed by clerics (mainly Jesuits, but also Franciscans, Carmelites and Mercedarians).

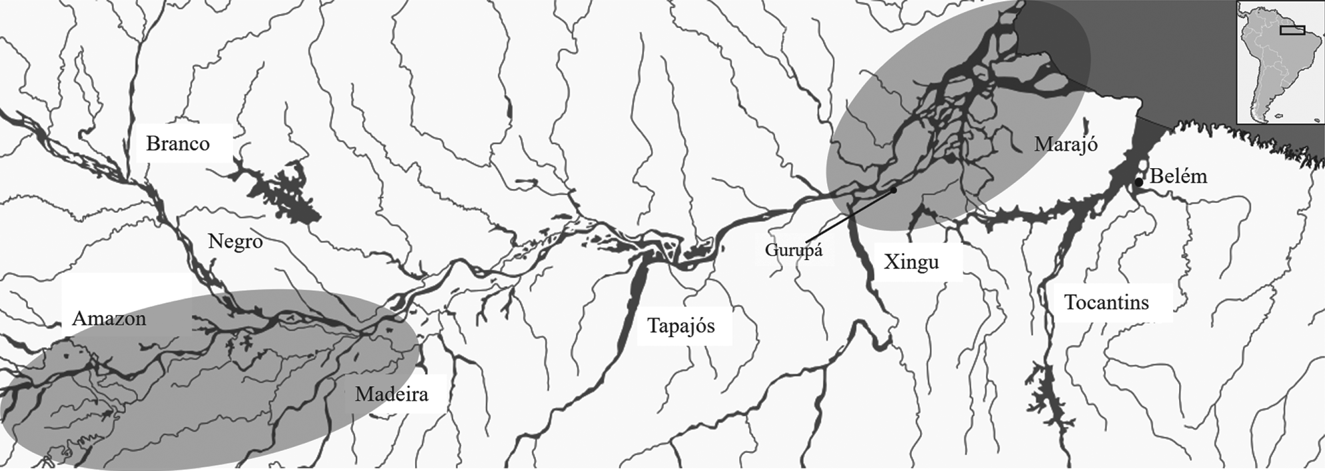

Thus, the hinterland and the agricultural region of the Amazon river delta (Figure 4) were closely linked.Footnote 74 The city of Belém, in the captaincy of Pará, represented the heart of a system in which canoas full of slaves and spices arrived from the sertões, and from where expeditions departed to the hinterland. Ships also arrived from and departed for Lisbon, carrying Amazonian products as well as African slaves, European products, new settlers, soldiers and colonial officials.

Figure 4. Belém's agricultural region (right) and hinterland (left)

Source: Authors’ elaboration from: mapas.mma.gov.br/i3geo.

One can follow the links between the economic expansion of cacao and the increase in demand for labour by examining data for official requests to purchase native slaves (resgates), as well as demands to bring free Indians from the sertão into the aldeias (descimentos). Unfortunately, as mentioned above, these records are far from systematic, for they are scattered throughout the most diverse sources. Of the 249 land grants related to the cultivation of cacao mentioned above (Footnote note 23), 55 contain some information about Indigenous labour. In royal letters granting slaves or free Indians from the sertões to the settlers, we find 11 references to settlers who explicitly demanded Indians for their cacao plantations. Unfortunately, few of these references indicate the size of the cacao estates.

In 1732, for example, Amaro Pinto Vieira requested a land grant whilst claiming that he had 6000 cacao trees, and 60 ‘servants’.Footnote 75 Although there is no way of confirming the number of his labourers, eight years later he was granted an authorisation to purchase 30 slaves from the sertão, and 50 more in 1744.Footnote 76 José da Silveira Goulart, who claimed in 1731 that he had planted 36,000 trees,Footnote 77 lost 22 of his labourers in the great measles epidemic of the late 1740s.Footnote 78 Another big planter of cacao, Cláudio Antônio de Almeida, received his lands initially in 1731.Footnote 79 In 1740, he reported having planted 20,000 trees in his two leagues of land alongside the Capim river (see Figure 2).Footnote 80 In 1728, he had received a grant of 25 to 30 free Indians or slaves for the cultivation of cacao that he would supposedly initiate.Footnote 81 In 1744, he received a new grant to buy 50 slaves from the sertões of the Japurá river, located in the distant western part of the Amazon basin.Footnote 82

The settlers’ requests amounted to almost 4,000 Indians. There is no certainty as to exactly how many of these authorisations were indeed put into practice. Since cacao was never cultivated exclusively, there is no way of quantifying with any precision how many of the Indians worked on the cacao plots. Many of these Indigenous labourers, both free and slave, could also be used for the gathering of cacao (as well as many other spices) in the hinterland, since, as mentioned before, the exploitation of cacau bravo and cacau manso was not mutually exclusive.

Camila Dias and Fernanda Bombardi analysed the available data concerning authorisations to purchase slaves or bring free Indians from the sertão from 1690 to 1745. They concluded that the increase in labour demand corresponded to the expansion of the Amazonian economy.Footnote 83 The data from our research indicate how owners of land grants dedicated to the cultivation of cacao, especially after the 1720s, mobilised a complex and extensive mechanism of Indigenous labour exploitation. In addition, epidemics, which ravaged the native population in 1695–6, 1725–6, 1743–4 and 1748–9, increased the need for labourers. Analysing settlers’ demands for slaves and free Indians, historiography has shown how the aftermath of these demographic calamities encouraged certain groups within colonial society to take initiatives in order to enslave or purchase free Indians from the sertões.Footnote 84 The available data give a clear indication that Indian labour was strongly associated with the exploitation of cultivated cacao.

Clerics and Cacao

A clearer picture of cacao cultivation and gathering, Indigenous slavery and forced work is provided by studying the Jesuits’ estates. From this examination, it becomes clear that the Society of Jesus, the most influential and the wealthiest religious order in the region, followed the same pattern as the rest of the settlers (although it enjoyed some legal advantages that were not available to the lay settlers). From the last quarter of the seventeenth century, the missionaries promoted not only the annual gathering of cacao, but also its cultivation in their key estates and far-reaching mission network. In an attempt to create a solid economic foundation for their aim of evangelising the Indians, especially after their first expulsion from the colony between 1661 and 1663 (a reaction of the settlers to the Fathers’ monopoly over the free Indigenous labour force), the Society of Jesus invested an increased effort in the production and exportation of cacao. The Fathers were aware of the huge demand for cacao beans in Europe.

Father João Felipe Bettendorff, Superior of the Amazon Mission at that time, engaged in the diffusion and cultivation of cacao trees throughout the colony. During the 1670s, he regarded cacao as one of the key products, besides clove bark, cotton and sugar, that could improve the profitability of the Maranhão Mission, as the Jesuits referred to their administrative circumscription in the Amazon. In his writings, Father Bettendorff highlighted his many attempts to plant cacao trees in the captaincy of Maranhão.Footnote 85 In 1678, his Italian confrère Pier Luigi Consalvi positively stressed Father Bettendorff's efforts to improve the economic situation of the mission by ‘planting cacao of which is made the beverage called Chiccolata’.Footnote 86 Father Bettendorff's report also shows that he intended to cooperate, to a certain extent, with the settlers, as he considered cacao as a kind of solution to the economic crisis that at the time affected not only the Portuguese possessions in the Amazon region, but the entire Portuguese colonial world.Footnote 87 According to another letter, Father Bettendorff even succeeded in convincing Governor Inácio Coelho da Silva (1678–82) to visit one of the new cacao plantations that he had established, pointing out the importance of the product in the context of the increasing consumption of hot chocolate in Europe.Footnote 88 Nevertheless, sources also indicate that, at the end of the seventeenth century, the Jesuits’ cacao production was affected by poor harvests. German-born Father Aloysius Konrad Pfeil hinted, in a letter from 1691, that the economic situation of the Mission was extremely unfavourable due to the decreasing amount of cacao beans and clove bark for exportation.Footnote 89

In 1701, an anonymous Jesuit member of the Maranhão Mission suggested to the church authorities in Rome that there existed a supposed greed among the settlers for spices, and that abuses of the native labourers were taking place. One can infer from this report the importance of cacao and clove bark in European markets. The author was alluding to harsh competition between settlers and missionaries in the production and sale of these two highly important Amazonian spices.Footnote 90

One cannot, however, take the commitment of the missionaries and the expansion of their plantations as exemplary of the whole cacao exploitation system in the Portuguese Amazonian region. As mentioned above, although non-religious settlers and missionaries alike adopted the same economic model, exploiting both cultivated and wild cacao, the Jesuits had relatively free access to the labour force who lived in the many villages that the priests administered in the sertões, as well as close to the main cities and forts of the region.Footnote 91

As the clerics also had workers, tools and expertise to fabricate canoas of various sizes, they were able to send expeditions into the sertões in search of Indians and spices, cacao included. During these incursions, they could rely on the many mission settlements scattered in the hinterland, as well as on a number of indigenous groups with whom they were already in contact. Furthermore, the Fathers received land grants not only from the Crown, but also from devout Portuguese settlers. Jesuits also routinely avoided paying royal tithes and were exempt from paying custom taxes, as mentioned above. As one can see, these factors provided enough reason for their secular businesses to prosper in the Amazon region, as indeed they did.Footnote 92 Nevertheless, references to income from cacao or other tropical products are rare in the official correspondence of the Society of Jesus. One of the few examples is a letter from Father Inácio Ferreira, rector in Belém, who informed the Superior General in 1709 that ‘he had sent 100 arrobas of clove bark and 400 of cacao to Lisbon in order to pay the expenses of the Mission’.Footnote 93

In 1704, the planters alleged in a complaint to the Crown that the Fathers were over-involved in cacao commerce, to the neglect of their spiritual obligations.Footnote 94 In the early 1720s, Paulo da Silva Nunes, an influential confidant of Governor Berredo, hyperbolically accused the Jesuits of being responsible for the systematic ‘ruin of the State’ of Maranhão and Pará through deliberate exploitation of the Indigenous labour force and the region's natural resources.Footnote 95 Berredo's successor, the Jesuit-friendly Governor João da Maia da Gama, responded that the Fathers produced more cacao, because, in addition to having more missions (and hence more Indians to work for them than the other religious orders and settlers), their missions were well run.Footnote 96

The disputes, however, did not affect ongoing Jesuit investment in cacao. Looking at the exports transacted by the religious orders in the Amazonian colony between 1743 and 1745 (the only detailed data that we have available), 78.7 per cent (a little more than 10,000 arrobas) were produced by the Society of Jesus, and 19.3 per cent (2600 arrobas) by the Carmelites. Cacao was the main product of both the Jesuits and the Friars of Mount Carmel – representing 81.4 and 90.9 per cent, respectively, of their traded goods.Footnote 97 Access to the sertões abundant in cacao, owing to the location of their missions, and to an Indigenous labour force were central to the endeavours of the Jesuits and the Carmelites.

Nevertheless, despite these numbers, one cannot state that the cacao activities of the Jesuits flourished to the detriment of settler cacao production, as the settlers would have the royal authorities in Lisbon believe. If one compares the production of the clerics with the data for all cacao exports, at least for the years 1743–5, the amount produced by the Society of Jesus represented only 5.4 per cent of the total.Footnote 98

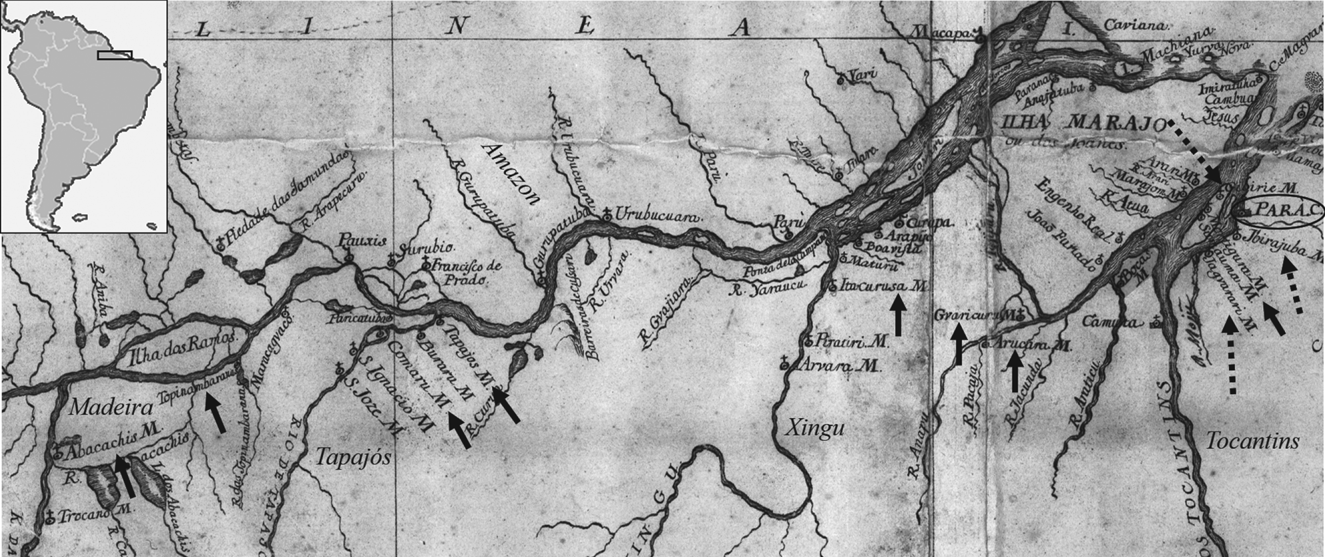

Similarly to the settlers, the Jesuits produced cultivated cacao on their estates, located in the area surrounding the city of Belém. A tenacious foe of the Jesuits, Governor Alexandre de Sousa Freire, drew up a list of the estates belonging to the priests and also collated details of their production activities. Sousa Freire – unlike his already mentioned immediate predecessor, João da Maia da Gama – certainly exaggerated the priests’ economic output in his efforts to prove to the Crown that the Jesuits had managed to ruin the Royal Treasury by routinely avoiding the payment of tithes. According to Sousa Freire, the clerics produced around 500 arrobas on their estates each year. And yet most of the cacao had come from the missionary villages in the hinterland. In their aldeias of Mortigura, Samaúma, Bocas, Guaricuru, Arucaru, Itacuruçá, Aricará, Tapajós, Cumaru/Arapiuns, Tupinambaranas and Abacaxis (on the rivers Tocantins, Xingu, Tapajós, Amazon and Madeira, and their tributaries), according to the governor, the Fathers processed around 5,400 arrobas of cacao (almost 80 metric tonnes).Footnote 99

At the time of their second expulsion from the region in the late 1750s,Footnote 100 the Jesuits themselves prepared a detailed inventory of the lands, goods and slaves that made up their estates. According to this document, they had two cacao orchards (cacauais) in Gibirié, five in Ibirajuba (which was not mentioned by Governor Sousa Freire), two in Jaguarari, and an ‘old cacaual’ in Taboatinga (also not mentioned by Sousa Freire) (see Figure 5).Footnote 101 In his report, Governor Sousa Freire listed the slaves that the clerics had been keeping on some of their farms; included amongst these were 100 servants in Gibirié. In Ibirajuba, the clerics had 300 slaves, including ‘negroes, cafusos,Footnote 102 mulattoes and Indians from the land [índios da terra], besides many Indians from the villages [aldeanos]’. Moreover, he stressed that ‘all the [missionaries’] lands here declared are cultivated by Indians, both male and female, from the villages [aldeias] that the same priests administer’.Footnote 103 Although we should approach Sousa Freire's document with caution, it indicates how crucial both free and slave Indigenous labour were in the development of the cacao industry in colonial Portuguese Amazon.

Figure 5. Jesuit missionary villages (unbroken arrows) and estates (dotted arrows) mentioned by Governor Sousa Freire. The city of Belém is ringed; missions are indicated by ‘M’ and/or a church symbol.

Source: Biblioteca Pública de Évora, Gav 4 N25, Mappa Vice Provinciae Societatis Iesu Maragnonii, 1753 (detail); river names Tocantins, Xingu, Tapajós, Amazon and Madeira have been added by the authors.

Father João Daniel, mentioned above, stressed the profitability of cacao orchards in the tropical climate of the Amazon when he recommended planting cacao in a system of crop rotation. As an example, he related the successful experience of a certain missionary – probably himself – in Cumaru on the Tapajós, where macaxeira (a kind of cassava), cacao seeds (which produced ‘10,000 trees’) and banana would be alternated annually on flooded and sandy terrain.Footnote 104 However, this form of cultivation did not prevail, nor was it adopted by other growers, since the Jesuits were expelled in 1759.

Conclusion

From the late seventeenth century, a series of Crown policies for the region (which included the encouragement of cacao cultivation) and a general expansion in chocolate consumption in Europe led to the overall intensification of cacao exploitation in the Amazon region. This increase led to the extension of lands cultivated with cacao (close to the city of Belém) and to the intensification of cacao gathering in the remote hinterland. These two economic frontiers, each with their own specific economic dynamics, required and relied upon labourers. In Amazonia, these labourers were enslaved Indigenous groups and (at least officially) free Indians, compelled to work on the settlers’ land and to row the canoas sent into the sertão by the Portuguese in search of more cacao (along with other Amazonian spices) and more Indians. This dynamic characterised the centrifugal nature of the Amazonian economy.

The expansion in Amazonian cacao, thus, did not follow the explanatory model which is most often applied to explain the development of a colonial economy: the introduction of an exogenous good (e.g. sugar cane) cultivated by imported labourers (e.g. African slaves). In fact, unlike in other cacao-producing regions, such as Caracas, the economy of Amazonian cacao – a product endemic to the region – was underpinned by recruitment of local forced labour, who also provided the necessary knowledge to explore and exploit this product. Moreover, the growth of the cacao economy was not solely reliant upon an increase in agricultural activities: it was mainly dependent upon the steady and continual opening up of the vast Amazonian hinterland, the gathering of wild fruits, and the search for additional labourers.

These dynamics of cacao exploitation in Portuguese Amazonia integrated the region through the Atlantic trade routes into the consumer markets in Europe. Contrary to Luso-Brazilian historiography, which emphasises the role of African slavery, the research undertaken so far indicates that the irrelevance of the Atlantic slave trade to cacao exploitation in Amazonia did not imply that the region became disconnected from the broader Atlantic network in the Early Modern period. Rather, intensive exploitation of Indigenous labourers underpinned the cacao exports destined for Lisbon and other European markets. Although native labour has been almost totally ignored by historiography, it was crucial for the setting up of an Atlantic trade route: an Amazonian Atlantic.