Recent years have witnessed a surge in critical work addressing the Eurocentrism of International Relations (IR) with calls for the decolonization of IR theory (Jones Reference Jones2006; Shilliam Reference Shilliam2011). Much of this literature draws on poststructuralist methods and poses an epistemological critique of IR theory, arguing that IR's central concepts are so implicated within the European imperial project that they continue to reproduce racialized and gendered power relations in global politics (Jabri Reference Jabri2013). They argue that IR's central frameworks reflect a particular subjecthood, that of Western elites, but are stripped of their particularity within IR discourse and universalized as being applicable to all. Social forms and political subjectivities that lie outside those established from the Western perspective are either ignored or negated as representing a subordinate alterity. According to this epistemological critique, decolonizing IR involves a radical overhaul of IR's concepts – state, nation, civil society etc. – in order to bring the subaltern subject back in as a proper agent of their own history (Seth Reference Seth and Seth2013).

A parallel approach focuses on reformulating the ontology of IR theory to build holistic social theory which captures the universality as well as multiplicity of social formations within IR (Matin Reference Matin2013). Such scholars call for building historical sociological account of the non-Eurocentric origins of capitalism and the modern state-system, with some looking to Uneven and Combined Development (Matin Reference Matin2013; Anievas and Nişancioğlu Reference Anievas and Nişancıoğlu2015) and others to building a pluralist global historical sociology (Go and Lawson Reference Go and Lawson2017). This paper fits within this approach and focuses on the English School (ES), which is also considered a potential site for holistic non-Eurocentric theorizing (Buzan Reference Buzan2004). It therefore does not seek to decolonize the ES along the lines of the epistemological critique; but rather contribute towards literature seeking to revise existing ES frameworks in reference to in-depth analysis of non-European contexts.Footnote 1

There are two major strands of self-consciously non-Eurocentric ES work: socio-institutional and interactive (Pella Reference Pella2015). Within the socio-institutional strand, ES scholars have explored different types of historical and non-Western international societies to identify how these are constituted by different institutionsFootnote 2 or different interpretations of the institutions of global international society, and thereby how they differ from and relate to global international society (Buzan and Gonzalez-Pelaez Reference Buzan and Gonzalez-Pelaez2009; Buzan and Zhang Reference Buzan and Zhang2014; Suzuki et al. Reference Suzuki, Quirk and Zhang2014; Schouenborg Reference Schouenborg2017). Within the interactive strand, scholars have revisited the historical expansion of European international society to identify the agency of non-Western polities in the constitution of international society's core institutions and in their adoption and adaptation in other parts of the world (Keene Reference Keene2002; Keal Reference Keal2003; Suzuki Reference Suzuki2009; Zarakol Reference Zarakol2011; Suzuki et al. Reference Suzuki, Quirk and Zhang2014; Pella Reference Pella2015; Scarfi Reference Scarfi2017).

Both non-Eurocentric strands have helped highlight the ES’ analytical value to non-Eurocentric theorizing. However, the concerns of the socio-institutional strand are primarily structural whereas the interactive accounts are interested in the historical agency of non-Western polities in their interactions with Europeans pre-20th century. Less work has been done to capture the agency of postcolonial states in building and managing international order in contemporary international society. This paper addresses this gap by focusing attention on how postcolonial states contest and negotiate with great powers responsibilities towards order. It does so through developing an analytical framework for studying social roles negotiation between states. Moreover, to address critiques of ES neglect of political economy and tendency to reify a Westphalian ideal of the state (Hameiri and Jones Reference Hameiri and Jones2016), this paper supplements its ES conceptualization of international order with a world-systems understanding of global capitalism and neo-Gramscian focus on social forces. This allows us to account for how states are embedded within the complex and shifting geography of global capitalism, and subject to the political contests between social forces operating within and across their borders. The social roles negotiation framework set out in this paper, provides the conceptual tools for mapping how divisions of labour are negotiated between great powers and other actors in the management of international order. This helps account for the special role that great powers still perform, but also better captures the variation of great power responsibilities across different historical and regional orders and, crucially, the roles small and postcolonial powers may perform. This paper first outlines the nature of ES Eurocentrism and the recent literature seeking to counter this Eurocentrism, before setting out its theoretical claims. It then applies the role negotiation framework to the indicative case of how the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has come to play an important part in negotiating and managing order in the Asia-Pacific – a region with multiple great powers. It shows how its managerial role was first legitimized within non-communist Southeast Asia (hereafter SEA) in a division of labour with the USA in the early 1970s, extended to encompass the full extent of SEA during the Third Indochina Conflict through a role bargain with China in the 1980s, and then further extended into the wider Asia-Pacific through bargains with the USA and China in the early 1990s.

Eurocentrism of the classical English School

Matin (Reference Matin2013, 354) defines Eurocentrism according to four assumptions: firstly, the historical assumption that modernity emerged endogenously and autonomously within Europe; secondly, that this makes Europe normatively superior to the rest of the world; thirdly, the prognosis that European modernity and its practices are destined to be universally adopted and finally, that development towards modernity unfolds in stages. European imperial thought actively promoted these assumptions as an intellectual justification for European colonization. Despite formal decolonization they remain present in Western scholarship as a ‘subliminal Eurocentrism’ (Hobson Reference Hobson2012). Classical ES work arguably reflects the first three of these assumptions.

The first assumption reflects the Eurocentric ‘big bang theory’ (Hobson Reference Hobson2012). This theory presents Europe's supposed endogenous development of international society as resulting from centuries of rivalry and warfare, leading to the consolidation of modern states, a dynamic economic system, and rules and institutions to manage relations between legally independent states. Central to this was the unique anti-hegemonism of the European system that found full expression after the Renaissance and Reformation, events which broke the authority of the unified Church and gave sovereign power to individual rulers over independent Kingdoms and city states. These independent states developed vernacular identities and official languages, and the competition between them encouraged commercial, political and scientific developments, especially after the Enlightenment. The sovereignty-based order was formalized in the Westphalian peace and anti-hegemonism consolidated by the emergence of the institution of the balance of power at Utrecht in the 18th century. From there special privileges were accorded to great powers in managing international order at Vienna in 1815 after the defeat of Napoleon (Watson Reference Watson, Bull and Watson1984, Reference Watson1992). For the classical ES theorists, these developments reflected Europe's cultural dynamism in contrast to the more rigid and self-contained cultures of the Asian empires (Watson Reference Watson, Bull and Watson1984, 13). They also attribute an expansionary logic to European international society which ‘filled out all its uncultivated spaces within its boundaries and began to push back its geographical limits’ (Watson Reference Watson, Bull and Watson1984, 13). These geographical limits would be pushed out to encompass the entire world, unifying it under the rules and institutions of European international society (Bull and Watson Reference Bull and Watson1984a).

Bull and Watson recognize their account could be accused of Eurocentrism but countered that ‘it was in fact Europe and not America, Asia or Africa that first dominated and in so doing, unified the world, it is not our perspective but the historical record itself that can be called Eurocentric’ (Bull and Watson Reference Bull, Watson, Bull and Watson1984b, 2). Bull and Watson's historical account is highly selective, omitting a wealth of detail about how Europe's development was dependent on the transfer of ideas, wealth and technologies from the empires of the East – even if they do recognize that Europe's development occurred simultaneously with and was influenced by expanding European contact with the rest of the world (Bull and Watson Reference Bull, Watson, Bull and Watson1984b, 6; Hobson Reference Hobson2004, Reference Hobson2012). European powers' interactions with their colonies were also fundamental to the constitution of European societies and the intra-European state system, with colonialism a core and constitutive institution of European international society (Keene Reference Keene2002). For Seth (Reference Seth2011), this means that any satisfactory account of European let alone world history must be postcolonial. Instead, Bull and Watson's discussion of the spread of European international society ends up rationalizing imperialism and largely presents the entry of non-European states as a consensual rather than exploitative process (Hobson Reference Hobson2012, 226–28). For example, Bull (Reference Bull, Bull and Watson1984a, 122) notes that European states could not have been expected to extend the benefits of membership of international society to African and Asian polities until they engaged in the domestic and social reform which ‘narrowed the differences between them and the political communities of the West’ and thereby enabled them to ‘enter into relationships on a basis of reciprocity’.

The second assumption of Eurocentrism is reflected in the two camps of the ES normative debate, pluralism and solidarism, which tend to re-enforce Western hegemony. Solidarism does so more explicitly through its advocacy for human rights and other liberal values as a demarcation of legitimate statehood and of humanitarian interventionism as a legitimate moral practice when such rights are violated by governments in despotic or ‘failed’ states (Wheeler Reference Wheeler2000). Solidarists envision justice for individuals as the purpose of international society, regardless of national state boundaries, and therefore individuals' rights should trump the rights of states (Wheeler Reference Wheeler2000). They have acknowledged the problems of universalizing Western-derived values, whilst maintaining that certain rights are fundamental and universal (Vincent Reference Vincent1986). However, the focus on the responsibility of Western states for disseminating liberal values and upholding fundamental rights through intervention reflects an underappreciation of colonial history and reinforces Western paternalism. Equally problematic is the way solidarists have reproduced imperial dyads such as civilization/barbarism. Solidarism was at its zenith in the 1990s amongst a widespread sense of Western triumphalism after the Cold War and earnestly sought solutions to appalling atrocities and human rights abuses. However, solidarism overlooked the continuities between contemporary liberal interventionism and 19th century imperial interventionism. Humanitarian aims have long been mobilized to justify interventions by core capitalist states within peripheral states to reorder them according to core states' interests. Viewing humanitarian intervention within this broader lens sheds light on how it could be co-opted as part of a bigger project of neoliberal capitalist reordering under the guise of ostensibly apolitical and technocratic ‘good governance’ (Macmillan Reference Macmillan2013). Although morally appealing, solidarist arguments regarding human rights, legitimacy and humanitarian intervention did not tackle the broader political-economic circumstances under which such atrocities took place and instead fed into a reactionary neoliberal firefighting.

ES pluralism argues for the explicit recognition of difference within international politics rather than the normative expansion of Western-derived international society. Pluralists acknowledge that the expansion of international society involved the violent imposition of European values on other parts of the world but argue that the post-1945 system has allowed for the legal and political recognition of cultural diversity through the primary institutions of sovereignty, non-intervention and self-determination (Jackson Reference Jackson2000). Pluralists consider these institutions as universal and procedural, allowing for peaceful interaction between political communities (embodied by states) representing distinct cultural values. However, Seth (Reference Seth2011) identifies two main problems with this argument. Firstly, the ostensibly procedural institutions are fundamentally substantive, reflecting Western power in their development, global spread and in the continuing contingency of their derivative rights according to Western geopolitical interests. Secondly, modern states do not embody coherent cultural communities but are fundamentally political constructs, often representing the interests and culture of hegemonic social forces within the national boundaries that have sought to entrench their dominance through marginalizing or even erasing other cultural or value systems (Seth Reference Seth2011). Pluralism's assumption of horizontal recognition of difference therefore masks the hierarchical power relations that operate between and within states (O'Hagan Reference O'Hagan and Bellamy2005).

ES historiography also leads to the third assumption that the expansion of European international society is an essentially linear process where regional empires and social systems outside Europe succumb to the compelling logic of Europe's expanding society. Bull and Watson acknowledge the existence of regional international systems consisting of complex and sophisticated civilizational and legal structures; however, they do so to highlight the uniqueness of European international society in breaking free of hierarchical suzerain logic rather than explore the interconnections between these regional systems and how this may have shaped developments within Europe (Bull and Watson Reference Bull, Watson, Bull and Watson1984b, 2–6; Watson Reference Watson1992, 6–7). Subsequent chapters in their edited volume focus on how these regional systems collapsed upon contact with European power and were absorbed within Europe's expanding social system in the 18th and 19th centuries. Under this logic of the expanding international society non-European agency is confined to two types: ‘conditional agency’ whereby non-Europeans adopt European norms and practices to be accepted as members of international society; and ‘predatory agency’ whereby non-compliance and resistance represents a threat to international society (Hobson Reference Hobson2012, 214–15). The first is personified in Japan's entry into international society and the second in what Bull called the ‘revolt against the West’ after decolonization (Bull Reference Bull, Bull and Watson1984b). Recent literature suggests that European dominance came a lot later than is often assumed in these accounts, with China remaining at the core of the global economy until the latter half of the 19th century (Frank et al. Reference Frank, Denemark and Gills2015). Even after the Opium wars and the imposition of unequal treaties, the British and other colonial powers had to operate their treaty system in China alongside the China-centred tribute system and were never able to fully penetrate the Chinese hinterland (Hamashita Reference Hamashita2002). This was also the case with other early European colonies which often had to operate under plural legal systems rather than a single system imposed by imperial Europe (Benton Reference Benton2002). This challenges the sense that the expansion of European modernity was a linear process and shows that heterogeneity, plurality and hybridity are enduring features of international society. It also opens the door to analysing much broader forms of non-European agency during the expansion of international society and today. The next section looks at how recent ES work has begun to account for the heterogeneity of international society through in-depth analysis of the socio-institutional make-up of regional international societies and the historical agency of non-European polities in their interactions with European powers.

English School responses

Socio-institutional accounts and the constitution of non-Western international societies

The socio-institutional strand's analysis of non-Western international systems and societies has largely followed Buzan's recasting of the ES conceptual framework, which reimagined the triad of international system/international society/world society into a spectrum of types of inter-human, inter-state and transnational societies distinguished by the primary institutions present (Buzan Reference Buzan2004). A research programme was subsequently launched analysing regional international societies with two important volumes analysing the Middle East (Buzan and Gonzalez-Pelaez Reference Buzan and Gonzalez-Pelaez2009) and East Asia (Buzan and Zhang Reference Buzan and Zhang2014). Another volume has touched on pre-modern societies before the rise of the West, although its primary focus is early-modern European interactions with non-European orders (Suzuki et al. Reference Suzuki, Quirk and Zhang2014). These studies have sought to map out the primary institutions of these regional societies and explore how they differ from the European and global international societies either in containing unique institutions, lacking institutions present at the global level or containing local interpretations of how institutions present at the global level operate at the regional level (Buzan and Zhang Reference Buzan and Zhang2014, 7). This is complemented by Schouenborg's (Reference Schouenborg2017) work seeking a means to study primary institutions transhistorically and across different types of societies by categorizing them according to four functions: legitimacy and membership; regulating conflicts; trade and governance. These responses have redressed ES Eurocentrism by providing new ways of studying international societies in world history. By doing so, they allow us to take snap shots of how societies appear at any given time or to view the development of such societies in the longue durée. There is less space within these accounts to identify agency. The second strand has focused on the agency of political communities in the Americas, Africa, Asia, Russia and the Ottoman Empire in their interactions with Europeans leading up to the globalization of modern international society.

Interactive accounts and non-Western agency

The interactive accounts have three aims. Firstly, they seek to counter the Eurocentric ‘big bang theory’ by positioning Europe within its proper historical context as a peripheral part of a broader global system for the centuries preceding its rise. Phillips (Reference Phillips, Dunne and Reus-Smit2017) has shown how significant interaction took place between ‘civilizational complexes’ within a single Afro-Eurasian ecumene for centuries preceding Europe's ‘age of discovery’ and shows how Latin Christendom was just one part of a single interconnected international economic system. The foundations for Europe's subsequent rise were not internal but laid through its interaction with other civilizational complexes within the larger system. The chapters in Suzuki et al. (Reference Suzuki, Quirk and Zhang2014) look more deeply at how Europeans interacted with other civilizational complexes and how they initially came as supplicants rather than dominant players, having to adapt to local rules and practices to profit from prospective trade.

Secondly, they seek to demonstrate how the violence towards non-European peoples and societies by Europeans was not an unfortunate by-product of international society's expansion but necessary for the constitution of intra-European international society. Keene (Reference Keene2002) analysed the co-constitutive development of international law within Europe and in the colonies of European powers, noting two organizational logics – one recognizing sovereignty and self-determination within the European core, the other applying strict civilizational standards to justify colonial appropriation of land and resources. Keene (Reference Keene2014) has since revised this initial bifurcation, arguing that we should view this period not as expansion but rather as stratification. He seeks to move beyond analysis of international society as a bounded ‘family of nations’, which outsiders entered into, and instead capture the multiplicity of types of political communities and how they fit within a stratified international society. This captures the complexity and heterogeneity of IR up to the 19th century. Keene argues that this helps explain apparent anomalies such as Siam being recognized as a member of international society once deemed ‘civilized’, and the small German or Italian states being swallowed up despite being members of the civilized family of nations. The ‘life chances’ of states during this period therefore depended on their positions within the hierarchies of material power, prestige and authority (Keene Reference Keene2014).

Another conceptual modification of the expansion account is offered by Reus-Smit and Dunne (Reference Reus-Smit, Dunne, Dunne and Reus-Smit2017) who argue that we should understand this process as the globalization of international society, doing away with the system/society distinction, bringing power and contestation as central to the analysis and recognizing the ubiquity of cultural diversity. Their edited volume revisits many themes expounded in Bull and Watson's volume whilst including others that were overlooked. For example, Towns (Reference Towns, Dunne and Reus-Smit2017) analyses how central gender power relations were to the globalization of international society. A multiplicity of gender dynamics operated across different polities in the 17th and 18th centuries, including female- as well as male-dominated political systems. Political organization was homogenized into male-dominated states because the exclusion of women from politics became an integral part of the standard of civilization applied to assessing legitimate statehood. The globalization of male-dominated politics in turn prompted the emergence of globally connected feminist movements to resist patriarchy and fight for women's emancipation.

Thirdly, they explore the agency of non-European polities in negotiating the expansion of international society within their own region. Suzuki uses an adapted socialization framework to analyse China and Japan. He extends the range of options available to interacting states beyond passive internalization, identifying strategic and emulative learning as important elements of socialized states' agency. He shows how Japan's emulative learning involved the adoption of an imperialist foreign policy (Suzuki Reference Suzuki2009). Zarakol documents the experience of stigmatization by non-European states in their interactions with Europeans in the 19th century, positing this as a fundamental dynamic of norm diffusion overlooked by Eurocentric perspectives that assume norm diffusion and internalization as a progressive and modernizing process based on successful persuasion (Zarakol Reference Zarakol2011). Pella (Reference Pella2015) analyses interaction between European and West-Central African societies showing how non-state actors were crucial in constituting the globalizing international society during the 14th to 20th century (Pella Reference Pella2015). He seeks to develop the under-theorized notion of world society and move the ES away from its attachment to a static notion of the ‘Westphalian’ state (Pella Reference Pella2015, 14–20). Up until the 19th century, Europeans who interacted with non-European societies were non-state actors seeking to trade, proselytize and profit within extant, highly-developed regional systems.

These studies have provided necessary revisions to how we understand the development and spread of the key institutions of global international society. They have highlighted the subjectivity and agency of non-Western states and polities in their interaction with a globalizing international society before or during the 19th century. In doing so, they complement the socio-institutional accounts by showing how certain institutions were globalized but also how different interpretations of global institutions and uniquely regional institutions emerged within regional international societies. This reflects the ubiquity of cultural diversity emphasized by Reus-Smit and Dunne (Reference Reus-Smit, Dunne, Dunne and Reus-Smit2017) and is sensitive to the hybridity of postcolonial agents (Jabri Reference Jabri2013). It also shows the centrality of power and contestation/resistance in shaping extant institutional structures. The impact is therefore to demonstrate how pre-colonial and colonial interactions have shaped regional and global orders. To supplement this there remains a need to identify an ES framework for capturing postcolonial states' agency in building and managing order in contemporary international society, that is, after formal decolonization. This paper posits that a social roles analysis can help us in this endeavour by capturing two types of postcolonial state agency in relation to order-building and management.Footnote 3 Firstly, how postcolonial states and social forces have contested and constrained great powers by socially embedding their legitimate exercise of power (and resisting illegitimate exercises of power). Part of this can be closing off certain functions related to the management of order from being performed by external great powers. Secondly, in how postcolonial states have negotiated their own responsibilities and roles towards order vis-à-vis great powers. This has involved assuming the performance of certain order functions usually associated with the great power role and creating and performing new functions deemed necessary for the management of order, which have gained acceptance, and thereby been legitimated, by the great powers. The next section develops the conceptual and analytical frameworks for analysing these forms of postcolonial agency.

Social roles and agency

Social roles and the English School

The language of social roles and responsibilities are familiar to the ES; however, an analytical framework for tracing how social roles are negotiated has not yet been developed from an ES perspective. Doing so helps shift our attention to the relational process of contesting and negotiating responsibilities towards order in contexts where newly independent states are emerging into systems dominated by imperial great powers. Social roles are not structural properties but are instead based on the mutual expectations and bargains between relevant parties. An actor's social role – which encompasses identity, status and social responsibility – depends on the legitimacy of the actor in that role in the eyes of other actors. Analysing how such bargains are struck and the bases upon which the respective parties establish their legitimacy to perform a role enables us to bring the complex politics, resistance and contestation into the story of how order is negotiated and managed.

Assumptions regarding divisions of responsibilities are inherent within ES analysis of the institutions of international society. Classical ES work has assumed that great powers have exercised special responsibilities due both to their superior capabilities and their distinctive social status. This is not just in terms of the institution of great power management, but also the balance of power, international law, diplomacy and war, to take Bull's classic five institutions seen as crucial for the management of order. Recent re-evaluations of great power responsibility from an ES/constructivist perspective have, however, demonstrated that such responsibilities are far more complex and diffuse than is captured in the classical ES accounts. This is due to shifting distributions of power between established Western powers and rising non-Western powers and the plethora of non-state actors involved in global governance and international law (Astrov Reference Astrov2011; Bukovansky et al. Reference Bukovansky, Clark, Eckersley, Price, Reus-Smit and Wheeler2012; Cui and Buzan Reference Cui and Buzan2016; Bower Reference Bower2017). Furthermore, it has highlighted how great power responsibilities cannot be assumed from analysis of European history and then applied to different regional contexts. Rather, analysing the politics of negotiating and contesting great power responsibilities, within proper historical and regional context, is crucial in accounting for the agency of non-European political forces (Loke Reference Loke2016). This paper does precisely this by centring its analysis on the complex and contested process of negotiating regional order and social roles in Southeast Asia during and after formal decolonization. It builds on existing ES work that has analysed how the institutional structures of decolonized SEA emerged and were shaped by the agency of indigenous actors in their interactions with external great powers and global international society (Quayle Reference Quayle2013; Spandler Reference Spandler2019). It takes a different route than these socio-institutional accounts, however, positioning its analysis of social roles within an ES conceptualization of international order, embedded within a broader conception of an uneven capitalist world-system and subject to the politics of sub-state and transnational social forces.

World-system, international order and social roles

Since the onset of formal decolonization, we can identify two distinct periods within the capitalist world system which provide a backdrop to the empirical discussion in the next section. The first ran from 1945 to 1970 and was characterized by a concentration of productive, financial and military capabilities within the hegemonic state complex of the USA, and state-managed capitalism as the prevailing model for political-economic organization. During the peak of its hegemony, a hegemonic state seeks to organize expansion within the system through a wider and deeper economic division of labour and specialization of functions, which requires cooperation between the principal states in the system (Arrighi and Silver Reference Arrighi and Silver1999). The USA sought to revive Western Europe and Japan after 1945 as regional industrial centres so that they could participate in a revived world market. These regional centres were to be provided with raw materials by their former colonies in the Global South. The interventionist policies of Western powers in the Global South during this period sought to ensure friendly social forces came to power within decolonized states to further ensure the continued privileged access of Western states and corporations to the raw materials and markets of their former colonies. Such neo-colonialist policies were supported by alliances at home linking state managers, capitalist classes with transnational interests, and organized labour whose privileged access to secure employment and benefits depended on the exploitation of populations in the Global South. It was further shaped by the geopolitics of the Cold War and ideology of anti-communism. However, the Cold War also provided space for anti-communist and non-communist nationalist social forces to pursue Import Substitution Strategies to resist neo-colonial exploitation and develop indigenous capitalist classes and industries. Likewise, Germany and Japan were able to launch industrial strategies that enabled their corporations to compete directly with US corporations at the higher end of production by the late 1960s. At the same time, social movements in the USA were demanding wage rises in line with inflation, the expansion of civil rights and the expansion of welfare provision. State-managed capitalism therefore faced a crisis of profitability and overproduction, leading the USA to free itself from the constraints of the gold standard – which had forced it to maintain a stable balance of payments – and to deregulate finance.

This ushered in the second period which has run from 1970 onwards and is characterized by the post-Bretton Woods financial and military preponderance of the USA, but loss of productive preponderance with the catch-up and competition from Germany, Japan and now China. This period has seen massive financial expansion and financialization of capitalist accumulation into spheres of social reproduction previously considered the remit of state provision. The dominant model of political-economic organization has been neoliberalism, which emphasizes liberalization and the expansion of market competition. The USA's globally operative banks and the dollar's status as the global currency ensured privileged US access to global liquidity. By quashing union power at home, the USA enabled production to be restructured with manufacturing moving to East Asia and other areas with a cheap and pacified labour force. The new international economic division of labour was characterized by an indebted US government and population purchasing goods produced in East Asia, with East Asian states reinvesting accumulated surpluses within the US financial system, propping up the value of the dollar and underwriting their key export market. To attract finance from global markets centred in New York and London, states in the Global South have been compelled to implement neoliberal reforms, supported by international financial and developmental institutions often in the wake of economic crises.

Throughout the above two periods, the role of the US state in seeking to organize the world-system has been crucial. However, as Arrighi and Silver (Reference Arrighi and Silver1999, 26–31) point out, no matter how much dominance a state has within the system it can only become hegemonic if it has the consent of other actors within the system. This perspective intersects with ES work on hegemony (Clark Reference Clark2011; Goh Reference Goh2013). Consent is achieved through social negotiation and, to varying degrees, accommodation of secondary and smaller states' interests and identities. Here is where international order offers a useful conceptual frame because it focuses our attention on how states come to a consensus/accommodation over their individual and collective goals, the rules that are to govern their interactions towards achieving such goals, and the functions that need to be performed as part of the management of order (Alagappa Reference Alagappa and Alagappa2003). Other states are crucial for the co-management of the world-system, especially in more localized regional contexts where the hegemonic power's reach may be limited by logistical constraints and/or local political resistance. The hegemonic power therefore needs to reach an order arrangement and a division of labour with other states in managing order so that its goals can be met. This need not just be between the hegemonic and other great powers but could also include smaller powers. Smaller powers are not merely takers of a hegemonic or great power-determined order but active participants.

As already highlighted, however, we cannot assume states to be fixed or coherent actors but must instead account for their historical embeddedness within wider social relations, with their nature and orientation reflecting the balance between competing social forces (Jessop Reference Jessop2008). Social forces are informal or formally organized groups with shared interests, which may include classes – where strong class consciousness exists – but also groups which identify with a certain religion or ethnicity as well as broader social and political movements (Teichman Reference Teichman2012, 4–5). Social forces are intimately tied to the capitalist world-system. The constellation of social forces within a territorial space will be shaped by (and in turn shape) the position of that territory within the international economic division of labour. For example, organized labour movements emerge as a significant social force challenging repressive labour regimes where there is a concentration of industrial production. This leads capital to seek new sites for that production thereby reshaping the economic division of labour in the world system (Silver Reference Silver2003). Likewise, coterminous with the shift within the capitalist system from a state-managed to a financialized form has been the emergence of increasingly transnationally-linked neoliberal social forces within both the Global North and Global South, who challenged the state-led development paradigm adopted by most states after independence (Carroll et al. Reference Carroll, Gonzalez-Vicente and Jarvis2019).

To come back to the definition of international order, this can be broken down into three elements: goals, rules and functions. International order has the purpose of allowing social agents to pursue a mix of individual and collective goals. This paper is most interested in the overarching goals that states, and influential social forces, articulate in seeking to build consensus around what order should look like. Rules are necessary to govern interactions between states towards the achievement of individual and collective goals. Rules can take the form of explicit legal rules or deeper and more implicit norms that determine appropriate/inappropriate behaviour (Buzan Reference Buzan2004, 163–64). Order functions are a crucial element of an order arrangement between states which provides a conceptual link between order and social roles. As part of an order arrangement, states will come to a consensus over which functions are necessary for the management of order and how responsibility for the performance of those functions will be divided between the negotiating states. Order functions can fall across three categories of security, economic and diplomatic/normative (for an expanded discussion of order functions see, Yates Reference Yates2019, 22–26). The arrangement regarding the division of functions is what Yates (Reference Yates2017, 447–48) calls a role bargain: ‘a reciprocal arrangement whereby actors, implicitly or explicitly, agree to a division of labour with respect to the performance of order functions, which accords with their respective identities and statuses and satisfies their interests within the prevailing social and political context’. We can know when a role bargain has been reached when there exists agreement on: (1) a common goal for order; (2) what order functions should be performed towards achieving that goal (3) and who will perform which order functions. This will come at the end of a process of role negotiation, which itself involves three stages: role conceptualization, role claiming and role enactment (Yates Reference Yates2017). During role conceptualization an actor conceptualizes a role that they wish to perform. They then claim the role and, if they receive endorsement from the relevant legitimating constituencies, they can then legitimately enact the role by performing the functions associated with the role. If others contest the actor's role claims, then the actor can either give up or re-conceptualize the role and re-claim it. Order negotiation and role negotiation go hand in hand, so contestation and resistance over role claims, often accompanied by counter-role claims, will occur alongside more general contestation and lack of consensus over order. Both role claims and endorsement from legitimating constituencies can be understood along a spectrum according to the degree of cost to the claimant and/or endorser. The least costly may be purely discursive. The costliest will be substantive claims/endorsement which involves significant commitment in terms of material and/or political resources. In between are symbolic and performative (Yates Reference Yates2019, 30–35).

As highlighted above, the notion of a role bargain is already implicit within ES work on great power responsibilities (Bull Reference Bull1995, 194–222; Buzan Reference Buzan2004, 161–204). As great powers have superior capabilities, they are assumed to provide security and economic public goods as well as providing a general balance of power within international society and exercising local preponderance to keep other states in check (Bull Reference Bull1995, 201–02, 207–12). In addition, they are considered to perform the primary diplomatic/normative function of diplomatic leadership through acting as a concert of powers or through institution-building. This is especially at times of crisis and transition when they are expected to negotiate order and build institutions to lock-in new order arrangements. Small powers recognize the special status and rights of great powers in assigning these functions, but in return great powers need to exercise their responsibilities towards order and recognize small power identities, their status as sovereign states and the functions they may perform in upholding order (Goh Reference Goh2008). The functions of the small power role are considered to include diplomatic/normative functions in the day-to-day politics of order, not deeper questions of order at times of transition (Panke Reference Panke2012). However, as Goh (Reference Goh2013) convincingly demonstrates, small powers are fundamental to the social compacts that underpin international order, especially as expressed through bargains over issue-specific institutions. Such institutional bargains serve to tame and legitimize unequal power by setting legitimate boundaries on the exercise of hegemonic power and legitimizing small and middle-power roles. Through her analysis of the competing US-centred Asia-Pacific and China-centred East Asian institutional bargains in the post-Cold War period, Goh (Reference Goh2013, 28–71) has shown how the Southeast Asian states, acting through ASEAN, have developed a brokerage role, mediating and brokering uneasy compromises between the competing bargains. The empirical discussion below builds on Goh's work but situates ASEAN's current managerial role in the post-Cold War Asia-Pacific within a longer historical timeframe, rooted in negotiations and contestation over order and roles in SEA during decolonization and the Cold War. The role bargains reached between ASEAN and the USA, and later ASEAN and China, led to the key function of diplomatic leadership being decoupled from the great power role and transferred to the small powers acting collectively through ASEAN. ASEAN was then able to build on this earlier division of functions within SEA to expand its managerial remit to the wider Asia-Pacific during the uncertain regional order transition in the late 1980s/early 1990s. Through highlighting this, the paper demonstrates the utility of the role negotiation framework for capturing both major types of postcolonial agency outlined above.

Negotiating order and social roles in Southeast Asia and the Asia-Pacific

ASEAN has two managerial roles. The first relates to its preeminent position as primary manager of Southeast Asian order, a role that was established in non-communist SEA by 1975 and extended to the whole of SEA during the Third Indochina Conflict. The second is its diplomatic role in convening and facilitating regional dialogue and agreement over regulative norms in the Asia-Pacific. This role was created as part of the institutionalization of the ASEAN Regional Forum culminating in the adoption of its concept paper in 1995. The empirical discussion below therefore focuses primarily on the period 1945–95 to outline how order has been negotiated and how a division of labour over the performance of functions emerged placing ASEAN in its unusual position of leadership in the post-Cold War Asia-Pacific.

1945–65: Contestation over order and responsibility in Southeast Asia

Constellation of social forces in post-WW II SEA: Four key social forces emerged across SEA after the second world war (Hewison and Rodan Reference Hewison, Rodan and Robison2012). Firstly, revolutionary communists who sought a complete overhaul of social order and pursued armed struggle against the Japanese and returning imperial powers in Vietnam, Malaya (1948–60) and the Philippines (1942–54). Communists in Indonesia aligned with non-communist nationalists and tied their future to the post-independence state. Secondly, Western-aligned anti-communists who cooperated with the departing colonial powers to take over the newly independent states. These forces essentially left the social order and its institutional apparatuses intact and were dominant in Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore, as well as uncolonized Thailand. Thirdly, nationalist social forces who were resistant to political and economic involvement of foreign powers in the region. They sought to develop indigenous bourgeois classes that could drive development, end dependency on foreign capital and provide a foundation for political power. This force was dominant in Indonesia from the time of the revolutionary struggle until 1965. Finally, socialists who were anti-colonial, broadly anti-capitalist but opposed to the totalitarianism of Soviet-aligned communism. These were strong in Burma pre-1962, and more generally amongst intellectuals, students and trade unions across SEA. The fortunes of these social forces became tied up in the geopolitics of the Cold War, a period characterized by a struggle over regional order – its goals, rules and functions – between anti-communists and communists, but also, within the non-communist sphere, between the USA and its regional allies and anti-colonial and neutralist nationalists led by Indonesia. In this section we focus on the latter contest.

Indonesia promoted an autonomous regional order, claiming to perform diplomatic leadership through an indigenous great power liberator role. In contrast, the USA sought to embed an anti-communist order with the goal of communist containment, performing the functions of military and diplomatic leadership and providing security and economic club goods through a great power guardian role (Table 1).

Table 1 Indonesian and US visions of Southeast Asian order, c. 1948–65

Indonesia role conceptualization and claiming: There were two phases of Indonesia's conceptualization and claim to its indigenous great power liberator role, which correspond to the periods of parliamentary democracy (1950–57) and Sukarno's guided democracy (1958–65). During the former, a series of different cabinets were in power, reflecting the fluctuating influence of the nationalist Indonesian National Party (PNI), Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) and the Islamic parties of Nahdatul Ulama and Masjumi. Each were committed to political and economic nationalism but differed over whether to pursue development through state ownership, cooperatives or indigenous private ownership (Robison Reference Robison1986, 37). No cabinet had the political resources to expropriate foreign-held capital and instead sought to build state enterprises and foster an indigenous capitalist class to compete with foreign-owned capital. The broad principles of Indonesian foreign policy emphasized anti-imperialism and independence and activism (bebas aktif). The legitimacy of ruling cabinets during this period could therefore be bolstered through the promotion of neutralism and independence from external power machinations. Indonesia's involvement with the Colombo Powers – a grouping of neutralist Asian states – and its hosting of the Bandung Conference in 1955 were symbolic and performative claims to diplomatic leadership in guiding states within the Global South towards autonomy by following the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence (respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty; non-aggression; non-interference in internal affairs; equality and cooperation for mutual benefit; peaceful co-existence).

During Guided Democracy, Indonesia made substantive claims to its liberator role and the function of revolutionary leadership through the nationalization of first Dutch (1957–59) and then British and American enterprises (1963–66) alongside Confrontation against the Dutch in West Irian (Papua) and the British in Malaysia. Sukarno exercised centralized power and balanced between the political forces of the military – given a stake in the authoritarian system through martial law and control over former Dutch enterprises and plantations – and the communist PKI. Sukarno sought to expel neo-colonial powers from maritime SEA and thereby put the autonomous order into practice. Sukarno eventually withdrew Indonesia from the UN and set up an alternative Conference of the New Emerging Forces, aligning Indonesia with the revolutionary states of China, North Korea and North Vietnam.

US role conceptualization and claiming: The USA's great power guardian role conception derived from its hegemonic aims discussed above in rebuilding a capitalist world market protected from communism through containment. US concerns regarding European and Japanese access to raw materials in SEA, as well as establishing a Southeast Asian market for Japanese goods, shaped how US officials viewed their role in the region. US post-war planners considered Japanese access to SEA crucial for preventing Japan accommodating with the communist bloc and ensuring its revival within the capitalist world market. US role conceptualization was also shaped by the racialized perceptions of US officials, who considered Southeast Asians to be childlike, emotional and more vulnerable to propaganda, and thereby not able to fully share responsibility for order building and management (Doty Reference Doty1993). In seeking to mobilize support for its vision of regional order and role claims, the USA promoted the ‘domino theory’ that if one non-communist state fell in mainland SEA then the rest would fall in quick succession. This presented an ultimatum to regional states and social forces: either they joined the ‘in-group’ of free world states by supporting US-led communist containment and thereby gain access to the benefits of inclusion – including the promise of protection from communism and capitalist economic development – or face exclusion and opposition from the USA. The USA therefore supported independence and nationalism if it was expressed by anti-communist social forces but opposed left-wing nationalist movements. The USA supplemented its military presence in SEA through a network of state and state-aligned agencies including the CIA, the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, Ford and Rockefeller Foundations as well as other aid agencies, which provided material and ideological support for anti-communist political, civil society and labour movements in SEA.

The USA supported the reassertion of colonial power in Indochina and Malaya where revolutionary communist forces took up arms. However, as the French sought withdrawal from Vietnam in 1954 the USA took a more active stance towards the goal of communist containment claiming to perform the function of holding-the-line in Indochina against the communist advance. It backed a puppet regime in South Vietnam, supported military dictatorship in Thailand and established a military presence in SEA through bases in the Philippines, Thailand and South Vietnam. To complement its military leadership amongst supporter states, the USA claimed diplomatic leadership through establishing a collective defence organization, the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). The founding Bangkok Conference in February 1955 took place 2 months before the Bandung Conference and was used as a propaganda exercise for demonstrating equal partnership between the USA and regional states (Jones Reference Jones2005). However, the only Southeast Asian members were Thailand and the Philippines. Aside from Pakistan, nationalist constituencies represented by the Colombo Powers (India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Burma and Ceylon), rejected invitations to join SEATO rebuffing it as a neo-colonial organization. The USA subsequently moved from claiming diplomatic leadership to practicing an overt stewardship function by intervening in regional states to sway political outcomes in its favour. This included the CIA's intervention in the Indonesian outer island rebellions in 1958 (Kahin and Kahin Reference Kahin and Kahin1997) and the massive US military interventions in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia.

Responses from legitimating constituencies: Both Indonesia and the USA struggled to secure widespread endorsement of their claims. Indonesia had some support from revolutionary forces around the region including the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), which had pockets of strength around the Malayan Peninsula, North Borneo and, prior to Operation Coldstore (a state crackdown on leftist forces in 1963), Singapore, but the MCP leadership remained reticent about joining Indonesia in seeking to overthrow the Malaysian government (Fujio Reference Fujio2010). Indonesia also appeared to have some endorsement for an autonomous order from the Philippines and Malaysia through the organization of the three states into the short-lived MAPHILINDO. Its founding Manila Declaration called for the removal of external military bases from the region. However, Indonesia failed to influence events surrounding the founding of the Federation of Malaysia – linking Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak and Sabah – which it viewed as a neo-colonial plot to maintain British influence. The Philippines also had no intention of removing US military bases, promoting MAPHILINDO mainly to bolster its claim to Sabah. Sukarno's Confrontation thereafter alienated the dominant ruling classes within Malaysia and Singapore.

The USA had substantive endorsement for its vision of an anti-communist order and its great power guardian role from ruling classes within Thailand and the Philippines, performative endorsement from those in Malaysia and Singapore and contestation from Indonesian nationalists and other revolutionary forces across the region. Thailand and the Philippines remained members of SEATO and provided support for US intervention in Vietnam through hosting bases and providing their own force contributions. Malaysia offered training to South Vietnamese troops and Singapore provided R&R support. These supporter states also benefited from US demand for primary and manufactured commodities during the Vietnam conflict which helped to spur moves towards export-led industrialization (Stubbs Reference Stubbs1999). However, the major contestation from Indonesia and other nationalist and revolutionary forces across Asia meant that the USA was unable to fully legitimize its vision of an anti-communist order and its role as a great power guardian. Therefore, no order and role bargain could be reached in non-communist SEA.

1966–75: Emerging order and role bargain in non-communist Southeast Asia

Indonesia role re-conceptualization: The mass killings perpetrated against the PKI and other leftist forces in Indonesia in 1965–66 was a major turning point. Indonesia's economic decline under Sukarno's Guided Economy meant that the political-bureaucratic elite within the military, which had come to operate many of the nationalized industries, no longer supported Sukarno's policies. They also came into conflict with the PKI's promotion of workers' control of enterprises. The destruction of the PKI and the side-lining of Sukarno allowed these anti-communist social forces, led by Suharto, to take power and reorient Indonesia towards integration into the capitalist world market. The Suharto regime ended Confrontation, took out international loans and implemented a programme of liberalizing economic reforms under the guidance of US-trained economists within the newly established Ministry for National Development (Bappenas) (Robison Reference Robison1986, 138–39; Simpson Reference Simpson2008). Under Suharto a political-business oligarchy emerged around a patrimonial state, which has remained largely in place in the post-Suharto era (Robison and Hadiz Reference Robison and Hadiz2004). The Suharto regime legitimized the 1965–66 mass killings and subsequent authoritarian rule by painting the PKI as a Chinese proxy out to undermine the Indonesian revolution. The regime played up an ever-present communist threat to justify military rule, whilst simultaneously promoting the state and its agencies as technocratic and apolitical, pursuing policies based on the economic logic of Indonesian development (Robison Reference Robison1986).

The Suharto regime aligned itself with the goals of the US-led anti-communist order and dropped its claims to the Indigenous liberator role. Indonesia's new role conceptualization was a leading-from-behind role within the newly created ASEAN (Anwar Reference Anwar1994). Through creating ASEAN, Indonesia achieved reconciliation with its regional neighbours and the nationalism and sense of ‘regional entitlement’ still present within the Indonesian military and political leadership was placated through the tacit recognition of Indonesia's status as first amongst equals within ASEAN (Leifer Reference Leifer1989). Indonesia would bind itself within the institutional framework of ASEAN and temper its regional ambitions in return for the other member states consulting Indonesia on major political decisions that might impact regional order and allowing Indonesia to shape the development of ASEAN (Emmers Reference Emmers2003). This bargain was reflected in ASEAN's founding declaration, which incorporated regional autonomy rhetoric from MAPHILINDO's Manila Declaration whilst allowing the space for members to determine the nature of their external alignments with great powers and thereby posing no challenge to the USA's military presence in SEA (Ba Reference Ba2009). Through articulating national and regional resilience as a goal for regional order in non-communist SEA – achieved through capitalist economic development – the goals of autonomy and containment were merged. Communism would be contained by developing strong states committed to economic development within the capitalist world-economy, alongside continuing counter-insurgency campaigns to pacify the countryside.

US role re-conceptualization: US role re-conceptualization was shaped by the growing economic crisis within the capitalist world-system, political crisis at home, and the desire to find a face-saving withdrawal from Vietnam. In 1969, President Nixon announced the Guam Doctrine which expressed US commitment to offshore nuclear deterrence and continued military aid and assistance but end of any commitment of US troops on the ground. The administration considered this part of the USA stepping back from carrying the entire burden of protecting and expanding the capitalist world system, which was also dramatically demonstrated by the decision to end the direct convertibility of the US dollar to gold in 1971. The USA's steady disengagement meant the withdrawal of any US claims to stewardship or diplomatic leadership in SEA. The USA no longer sought to organize the region as it had before but expected regional states to do this themselves. Its new role conceptualization was that of an offshore great power guarantor rather than an interventionist guardian. US officials therefore viewed regionalism between the non-communist Southeast Asian states as a positive development (Thompson Reference Thompson2011). They also hoped that regional allies could be more vocal in legitimizing US strategy in Indochina, as is evident through conversations between US and Indonesian officials in the lead-up to the Jakarta Conference on Cambodia in 1970, an initiative by the Indonesian government to discuss responses to the Cambodian coup (Ang Reference Ang2010).

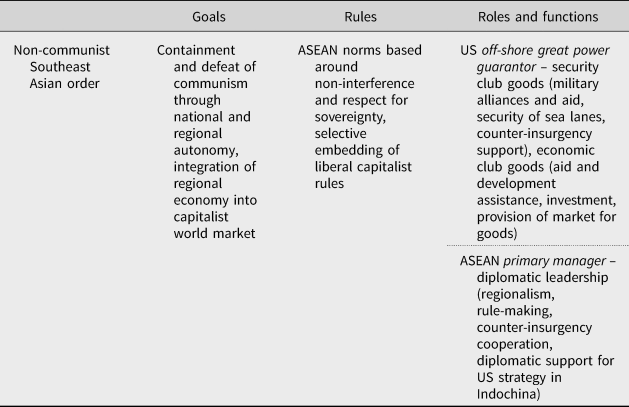

US–ASEAN role bargain: In light of the USA desire for an offshore role, negotiations around ASEAN had important implications for the division of functions in SEA. Through creating ASEAN regional states eschewed collective security functions and endorsed US provision of security club goods by accommodating external power military bases in the region. The emergent reciprocal role bargain consisted of the USA providing security club goods as the offshore great power guarantor in support of non-communist states' regime consolidation, in return for regional states collectively performing diplomatic leadership as part of ASEAN's primary manager role. ASEAN's diplomatic leadership had two aspects. First, regional states began to manage their own relations through reconciliation, regional institution-building and rule-making in their sub-region, as well as tackling communist insurgency through bilateral cooperation. Second, regional states provided a diplomatic front in support for communist containment in Indochina as shown through the Jakarta Conference 1970. The emerging US–ASEAN role bargain, fully enacted after US military withdrawal from Vietnam and Thailand in 1975–76, steadily became embedded within a broader understanding of an anti-communist order in SEA (Table 2).

Table 2 US–ASEAN role bargain, early 1970s

1975–90s: Extending ASEAN's managerial role to the whole of Southeast Asia

The early 1970s saw major geopolitical shifts in the region. The Sino–US rapprochement signalled a realignment in US policy from seeking to cut China off from Japan and SEA to seeking to shape China's re-engagement with international society in a way that supported US retrenchment from Vietnam. In the wake of US withdrawal, communist forces gained victory in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia in 1975. Individually, most ASEAN states pursued normalized diplomatic relations with both China and Vietnam, with Indonesia being a notable exception with respect to China. Collectively, the ASEAN states articulated a normative framework for relations (embodied in the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation (TAC) 1976) which they extended to Vietnam in the hope that this could form a basis for coexistence between non-communist and communist SEA. The Vietnamese rejected ASEAN's overtures, instead putting forward a Four Point position on regional relations which called for the removal of foreign military bases and progress towards ‘genuine independence’ (Nguyen Reference Nguyen, Westad and Quinn-Judge2005). During the late 1970s, geopolitical rivalry between China and Vietnam in Indochina escalated with China backing the anti-Vietnamese genocidal regime of the Khmer Rouge (KR). Both China and Vietnam sought support from the ASEAN states for their respective positions by emphasizing the threat the other posed to the region. On their respective tours of ASEAN capitals in late 1978, Deng Xiaoping and Pham Van Dong both claimed their states could perform a security guarantor role for SEA. Following a simmering border conflict, Vietnam invaded Cambodia in December 1978, sweeping the KR from power and installing the People's Republic of Kampuchea (PRK). China responded by invading northern Vietnam in February 1979. The Thai leadership viewed Vietnam's intervention as a security threat and other ASEAN states supported Thailand, viewing the Vietnamese as duplicitous having apparently offered explicit guarantees that they would not use force against any other Southeast Asian state, including Cambodia, only months before (Ang Reference Ang2013). The Third Indochina conflict, which lasted until 1991, saw a PRK–Vietnam–Soviet coalition face off against a KR–China alliance supported by ASEAN and the USA.

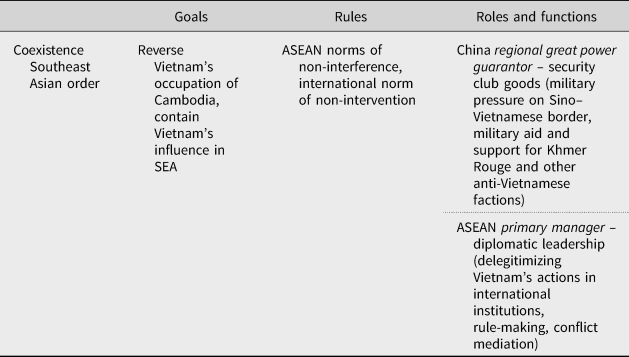

China–ASEAN role bargain: China and ASEAN shared the strategic goal of rolling back Vietnam's occupation of Cambodia and in pursuing this goal performed complementary functions in a division of responsibilities that would have significant implications for order after the end of the conflict. China performed the security function of holding-the-line against any expansion of Soviet–Vietnamese communism in SEA. China's invasion of Vietnam and brief, but costly war, fulfilled an earlier promise to ‘teach Vietnam a lesson’. China also maintained material support for rebel KR fighters along the Thai–Cambodian border and held out the possibility of another punitive attack. This provided a tangible security guarantee to Thailand, supplemented by China's withdrawal of support for the Communist Party of Thailand whose insurgency against the Thai government subsequently collapsed. To complement China's holding-the-line ASEAN performed diplomatic leadership, calling for Vietnam's withdrawal from Cambodia in yearly resolutions in the UN General Assembly and fighting to prevent the diplomatic recognition of the PRK at the UN and within the non-aligned movement. ASEAN also spearheaded the creation of the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK) in 1982 which sought to make opposition to the PRK more palatable by including the non-communist rebel factions led by Son Sann and Prince Sihanouk alongside the KR.

ASEAN was, however, divided over the conflict, with Thailand and Singapore taking a hard line against Vietnam, and Indonesia more sympathetic towards Vietnam and wary of China. Indonesia promoted compromise with Vietnam throughout the 1980s, embodied in the Kuantan Principle, which held out recognition of Vietnam's legitimate interests in Indochina in return for Vietnam ending links with the Soviet Union. Vietnam would not countenance such a proposal without a reciprocal commitment for the withdrawal of Western military forces from SEA. At the same time, Suharto was not willing to compromise ASEAN unity and so ultimately backed the Thai–Singaporean position. To try and limit China's influence in the region, ASEAN fought (unsuccessfully) for the disarming of the KR in the face of opposition from China and the USA, and thereafter for China's recognition of Cambodia's future neutrality. By extending its norms of autonomy and the TAC over Cambodia, ASEAN asserted the primacy of its vision of order and its primary manager role over the full extent of SEA. The conflict remained at a stalemate until the Sino–Soviet rapprochement and later Soviet collapse allowed for a resolution led by the UN Security Council. After this point ASEAN's diplomatic leadership over the whole of SEA was endorsed not just by China and the USA but also Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, which became members of ASEAN in the 1990s (Table 3).

Table 3 China–ASEAN role bargain during Third Indochina conflict

Interestingly, as China and Vietnam were confronting each other in mainland SEA, both states were pursuing reforms and transformations in their political-economy which would serve as a basis for their integration into the capitalist world market and for broader post-Cold War reconciliation. During the Third Indochina Conflict, Vietnam was economically isolated from the capitalist world and had to rely on Soviet aid and trade with COMECON members. Vietnam's economy stagnated in the early 1980s and by the end of the decade the leadership increasingly viewed market reforms and diversification in foreign relations as necessary to stimulate growth (Elliot Reference Elliot2012). Reforms implemented as part of the Doi Moi policy gave recognition to private land ownership, encouraging private enterprise in agricultural and commodity production and giving operational autonomy to state-owned enterprises (Gainsborough Reference Gainsborough2010). The Vietnamese leadership was inspired by the export-led industrialization of other Southeast Asian states and viewed its future in aligning with a Southeast Asian order that emphasized authoritarian capitalism over ideological confrontation.

The 1980s also witnessed a complementary shift in the political-economy of East Asia with the emergence of regional production networks financed by large flows of Japanese FDI. This integrated Southeast and Northeast Asia by developing business and production links and divisions of specializations in producing components for single products. In the 1990s China emerged at the centre of these production networks as a point of final assembly for export to the USA and the EU. China's liberalization and integration into the international economic division of labour was encouraged through the investments of overseas ethnic Chinese who invested their own capital and acted as intermediaries for other foreign capital (Peng Reference Peng2002). This network-led economic integration provided a material foundation for consensus on the goals of capitalist regional order, even if the extent of economic and political liberalization remained uneven and contested.

1989–95: ASEAN's creation of a new role in the Asia-Pacific

The above-mentioned shift in the political-economy of the region and broad consensus on economic goals was important in the context of the strategic uncertainty of the immediate post-Cold War period. Regional allies were concerned the USA would withdraw from the region because domestic sentiment both within the USA and base-hosting countries might turn against the cost of maintaining this presence without the overarching rationale of the Cold War. By 1992, the US Department of Defence had called for the reduction of US military personnel in two major policy reports and US forces withdrawn from the Philippines because of nationalist opposition. This led to further uncertainty around the potential resurgence of Japanese militarism and Chinese assertiveness. A consensus was missing over the rules that would govern relations amongst states in the Asia-Pacific and the functions that needed to be performed within the new context. Allies and partners of the USA signed new security arrangements to maintain US provision of security club goods under the incoming Clinton administration. Singapore and other Southeast Asian states signed access agreements to maintain a steady US military presence and US–Japan negotiations culminated in the 1997 revised guidelines, which extended the scope of the two states' alliance beyond the defence of Japan to provision of regional security. This gave renewed endorsement to the USA offshore great power guarantor role first enacted in the wake of the Vietnam war. With respect to China, all states in the region viewed engagement as the correct strategy for managing China's continuing integration into the capitalist world-system (Johnston and Ross Reference Johnston and Ross1999). ASEAN officials joined US business constituencies in successfully lobbying the Clinton administration to restore China's Most Favoured Nation status after the West had put sanctions on China after the crackdown at Tiananmen Square.

ASEAN's post-Cold War role conceptualization and claiming: ASEAN's conceptualization of a new managerial role in the emerging Asia-Pacific order came in response to Australian and Canadian proposals for Asia-Pacific wide security dialogue based on the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) and the establishment of the Australia–Japan-initiated Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) in 1989. Asia-Pacific regionalism threatened to subsume ASEAN and make it irrelevant. ASEAN responded by boosting its own institutional framework at the 1992 Singapore Summit through reforms to the ASEAN Secretariat and signing the ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (AFTA). ASEAN officials also rebuffed proposals for security dialogue from what they argued were ‘external’ states and counter-proposed an Asia-Pacific security dialogue based on ASEAN's Post-Ministerial Conference, launching the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) in 1994. ASEAN also secured agreement that APEC would be modelled on ASEAN-style informal and consensus-driven decision-making. ASEAN officials argued that only ASEAN could provide diplomatic leadership in the Asia-Pacific because it was an indigenous Asian association, and therefore its model was more appropriate for Asia, and because it was a non-threating group of smaller states that had demonstrated its ability to promote cooperation at the Southeast Asian level (Yates Reference Yates2019, 203–07).

By bringing all players together within a single forum through the ARF, ASEAN made performative claims to a new function of inclusive engagement. The Chairman's statement of an ASEAN-PMC meeting in 1993, outlined that ‘[t]he continuing presence of the United States, as well as stable relationships among the United States, Japan and China, and other states of the region would contribute to regional stability’ and called on ‘ASEAN and its dialogue partners to work with other regional states to evolve a predictable and constructive pattern of relationships in the Asia-Pacific’ (Emmers Reference Emmers2003, 115). By extending its diplomatic leadership through performing this new function of inclusive engagement, not only could ASEAN engage the great powers itself, but also foster an environment where the great powers could engage with each other. This could take place within a context of mutual commitment to ASEAN rules and norms. ASEAN's TAC was accepted in the ARF Concept Paper ‘as a code of conduct governing relations between states and a unique diplomatic instrument for regional confidence-building, preventive diplomacy, and political and security cooperation’ (ASEAN 1995). This gave ASEAN a rule-making function as part of its diplomatic leadership.

Post-Cold War role bargain in the Asia-Pacific: ASEAN embedded its role within role bargains with the USA and China. The USA supported ASEAN's role in return for ASEAN not challenging the USA's bilateral alliances through its proposed security dialogue, nor ‘drawing a line down the Pacific’ by developing an exclusive East Asian regional grouping. This bargain was upheld by reciprocal legitimacy dynamics: ASEAN could demonstrate regional autonomy in shaping the emerging regional order in a way that maintained its relevance; the USA, by being invited to engage the region in security dialogue, was able to better sell its Asia-focused foreign policy domestically in a way that did not alienate regional states through appearing as an ‘international nanny’. The ARF also provided the USA with a forum for engaging states with which it had troubled bilateral ties, notably China. In return for China endorsing ASEAN's role, ASEAN recognized China's interests as a responsible regional great power, but China needed to adhere to regional norms and show strategic restraint. For example, ASEAN accommodated China's concerns by emphasizing the informality of the ARF security dialogue, not inviting Taiwan to join and keeping the Taiwan issue off the agenda. China began to show signs of restraint, publishing a Defence White Paper and acquiescing to the South China Sea conflict being discussed at the second ARF meeting in Brunei in 1995. China indicated that it would abide by international law in sovereignty negotiations with other claimants to the Spratly islands representing a major concession as previously China had just insisted that the Spratlys were Chinese territory (Cheng Reference Cheng1999, 190). ASEAN's ability to persuade China to discuss the issue at the ARF impressed US officials with one reporting that this ‘convinced people that having the ASEAN Regional Forum was a useful forum. The ARF couldn't challenge the Chinese, but it could put a certain amount of pressure on the Chinese and force the Chinese to take opinions in the region into account in ways that the Chinese wouldn't have had to do if the organization didn't exist’.Footnote 4

Since these initial bargains were struck, ASEAN's managerial role in the Asia-Pacific has been contested and challenged numerous times, not least after the Asian Financial Crisis, during the Bush Administration and under the current pressures of great power rivalry.Footnote 5 However, ASEAN has been able to re-negotiate its role by renewing bargains with the great powers and asserting the importance of the functions of inclusive engagement and rule-making within a regional division of labour. ASEAN's most notable success in this regard was the development of the East Asia Summit in 2005 as the premier forum for strategic cooperation in the region. ASEAN asserted that signing the TAC was a prerequisite for membership and since then all the great powers have signed the treaty, acknowledging ASEAN's norms, at least symbolically. ASEAN faces heightened challenges due to growing great power rivalry, especially over the South China Sea and the Trump administration-initiated trade war with China. ASEAN has been unable to reach a consensus in how to deal with China's SCS claims and apparent assertiveness (Beeson Reference Beeson2016). Despite this, it remains at the centre of Asia's formal regionalism and will be crucial, alongside the great powers, in determining the future of order and power relations in the Asia-Pacific (Table 4).

Table 4 Asia-Pacific order and role bargain, c. 1995