Introduction

Lobbying regulations, understood as a system of rules which lobbyists need to follow when trying to influence policy outputs (Chari et al., Reference Chari, Murphy, Hogan and Crepaz2019), are an increasingly popular form of transparency policy. This form of regulation is currently in place in 18 democratic political systems, 13 of which have statutory rules in place for the profession of lobbying. The regulation of lobbying generally involves the introduction of behavioral rules lobbyists must follow in their activities (e.g., codes of conduct) and constraints in relation to their profession (e.g., post-employment restrictions for politicians wishing to enter the lobbying industry; Chari et al., Reference Chari, Murphy, Hogan and Crepaz2019). A fundamental dimension of any lobbying regulation is the creation of a transparency register, generally managed by an independent regulator, for which lobbyists need to disclose information about their activities (Năstase and Muurmans, Reference Năstase and Muurmans2018; Bunea and Gross, Reference Bunea and Gross2019). The amount and the type of information disclosed by lobbyists vary between jurisdictions (Chari et al., Reference Chari, Murphy, Hogan and Crepaz2019), although some broad categories can still be identified. Lobbyists generally need to disclose the subject matter of their advocacy activity, the ministries and officials being targeted, a detailed report of their activity and its goals, and sometimes the associated lobbying costs. Regulators publish registration information on online databases, which are open for public scrutiny. The publicity of the disclosed data means that lobbying regulations fall in the category of transparency laws, alongside freedom of information (FOI) laws, conflict of interest regulations, campaign finance laws, whistleblower legislation, and open-data policies (Chari et al., Reference Chari, Murphy, Hogan and Crepaz2019).

Lobby registers exist for the purpose of external scrutiny by the public. Governments often claim to introduce lobbying regulations with the objective of giving citizens and the media the opportunity to monitor lobbying activity, report on malpractices or imbalances of representation, and hold policy-makers accountable for their engagement with organized interests. This is believed to help input legitimacy and accountability and prevent cases of corruption and undue influence (Bunea, Reference Bunea2018; Chari et al., Reference Chari, Murphy, Hogan and Crepaz2019).

While these benefits of lobbying regulations may indeed be real, the literature has also suggested that lobbyists themselves might ultimately support regulations because of ‘reputational concerns’ (Bunea and Gross, Reference Bunea and Gross2019: 2). The possibility of having access to information about their competitors and partners on lobby registers might represent an additional reason for lobbyists to support the introduction of more stringent disclosure requirements (Bunea, Reference Bunea2018; De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2019). As a result, lobbyists’ attitudes toward regulation and their ability to shape its content according to their interests have been extensively studied in political science. Nevertheless, the extent to which lobbyists use the information present on lobby registers remains mostly uncharted territory.

This study claims that the transparency introduced by lobby registers serves a purpose other than public scrutiny, which is important for lobbyists themselves. It argues that lobby registers represent a source of information that can support the advocacy process and the profession of lobbyists more generally. By publishing details about the policy-making process and advocacy activities, lobby registers allow lobbyists to access valuable information about their profession that might otherwise be unavailable or difficult to retrieve. The reasoning behind this argument concerns the expected effects of transparency: by reducing the cost of searching for information and increasing knowledge, transparency is expected to change the behavior of those actors who have access to the information. Hence, the main questions driving the study are: Do lobbyists use the information disclosed on lobby registers in their profession? If yes, to what purpose? Answers to these questions will not only provide a first impact assessment of lobbying regulations but also explore how transparency affects the lobbying profession.

The analysis is based on data collected through a survey of more than 300 lobbyists in Ireland, which has regulated lobbying since 2015 (Chari et al., Reference Chari, Murphy, Hogan and Crepaz2019). The paper proceeds as follows. First, the main literature on lobbying regulations is linked to that on transparency. Then, the case selection and the data to explore the use of the register are discussed. Drawing from the literature on the advocacy process, the third section formulates expectations about how different interest-group characteristics are associated with different uses of the register. The fourth section presents the results of the multivariate analysis exploring these expectations. The final section summarizes the results, discusses the implications of the study and its limitations, and proposes avenues for future research.

Lobbying regulations as transparency policies

The existence of lobby registers that are open to public scrutiny means that lobbying regulations can be classified as transparency policies. Transparency in this context is understood as any ‘release of information about institutions that is relevant for evaluating those institutions’ (Lindstedt and Naurin, Reference Lindstedt and Naurin2010: 301). Transparency policies are therefore laws and regulations that control the flow and release of such information. FOI laws, for example, allow external actors to request the state to disclose information procedures and decisions taken by public bodies (Worthy, Reference Worthy2015).

There is no difference as far as lobby registers are concerned. Governments claim to have introduced them with the intention of allowing citizens to see who is lobbying whom, when, and for what purpose.Footnote 1 The goal of such regulations is to prevent undue influence and reduce risks of corruption in lobbying (Năstase and Muurmans, Reference Năstase and Muurmans2018; Bunea and Gross, Reference Bunea and Gross2019). The function of lobby registers is based on the assumption of the so-called ‘armchair scrutiniser’ (Fung et al., Reference Fung, Graham and Weil2007), which takes external actors like citizens or the media as the main consumers of transparency. Cucciniello et al.’s (Reference Cucciniello, Porumbescu and Grimmelikhuijsen2017: 36) recent review of transparency research shows that this assumption is well accepted in the literature and that ‘much of the existing government transparency research views external stakeholders (e.g., citizens) as the primary audience of government information’.

The very same information made public by transparency policies can also be ‘consumed’ by internal actors, namely, those who disclose lobbying information (Heald, Reference Heald, Hood and Heald2006). The two scenarios have received very different attention in the literature. The effects of transparency policies on external stakeholders have been well studied. For example, depending on the efficiency of their implementation, FOI laws can increase citizens’ perceptions of transparency and accountability and reduce perceived corruption (Worthy, Reference Worthy2015).

Studies of transparency beyond the ‘armchair scrutiniser’ assumption and on the uses of information by internal stakeholders are rare. Hazell et al.’s (Reference Hazell, Bourke and Worthy2012) and Worthy’s (Reference Worthy2012) studies on the use of FOI requests by members of parliament represent noteworthy exceptions. These studies show that a small but well-defined group of British MPs frequently file FOI requests regarding the government and fellow MPs and use the information as an accountability mechanism and a surrogate for parliamentary questions. Hence, it is naïve to consider users of transparency policies as an ‘amorphous’ mass called citizens (Meijer et al., Reference Meijer, Curtin and Hillebrandt2012: 18). As Worthy (Reference Worthy2015: 791) notes, consumers of information disclosed under transparency laws ‘are a diverse population [with] varied capacities and interests, far from the general public user politicians conjure up’. While MPs seem to use FOI requests for partisan goals, lobbyists might be interested in the disclosed information for purposes related to their profession. The next section discusses how information disclosure might relate to the advocacy process.

Information and the advocacy process

In regard to lobbying regulations, the internal stakeholders are the lobbyists themselves because they are the disclosing party. Thus, they are distinguished from external stakeholders, such as journalists or the general public, who do not fall within the scope of lobbying regulations. Registers collect information about the lobbyists’ goals, objectives, strategies, targets, and sometimes expenditures. Do lobbyists use this type of information in their profession? If they do, then for what purpose? Next, this question will be explored theoretically before evidence is provided from data collected for this study.

Information is often considered as a lobbyist’s currency. Although studies on informational exchange are well established in the interest-group literature, the information found on lobby registers has not generally been the focus of these studies. However, in a recent paper by De Bruycker (Reference De Bruycker2019), these registers were described as maps of the population of interest groups, which might help many lobbyists in their profession. They provide a rather accurate description of a lobbyist’s advocacy process, containing information about the subject matter of the activity and the policy-making process, as well as information about strategies, targets, competitors, and partners. ‘How competitive is my policy domain? Who are my competitors and how are they doing financially?’ (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2019: 1) might be examples of questions that lobbyists ask themselves and that lobby registers can answer.

By making information about the advocacy process open, lobby registers might reduce the transaction costs of collecting information about the costs and availability of the goods in the market in several ways. This is better illustrated by using Mahoney’s (Reference Mahoney2008) conceptualization of the advocacy process. Mahoney defines the advocacy process as:

[…] a process that aims to influence public policy. The process is initiated with an advocate’s decision to mobilise for a political debate, at which point the advocate determines his or her position on the issue. Once the advocate chooses to engage on an issue, a series of additional decisions need to be made about the advocacy strategy, including what arguments to use, what targets to approach, what direct or inside lobbying tactics to employ, what public education or outside lobbying tactics to engage in, and which allies to work with (Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2008: 3).

For each of these phases, the following paragraphs illustrate the way in which the information disclosed on lobby registers could facilitate the advocacy process. Firstly, given that lobby registers contain information about the way interest groups attempt to influence policy outputs, they might represent an indirect way for lobbyists to collect information about the policy-making process. By accessing the register’s portals, lobbyists can monitor the state’s legislative and regulatory activity, collect information about existing legislative proposals, initiatives, and events, and form their policy position (e.g., for or against the status quo) accordingly. Given that lobbying is often described as an informational game in which informational asymmetries concerning the decision-making process contribute to success (Austen-Smith and Wright, Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1994), the use of registers could be considered key.

Secondly, information might be used to select targets of the advocacy activity. In the preparation of their activities, lobbyists need to decide whether to lobby friends or adversaries, bureaucrats or elected officials, national or local administrations (Marshall, Reference Marshall2010; Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2012; Beyers and Hanegraaff, Reference Beyers and Hanegraaff2017). Lobbyists might decide to select targets based on information about who has been lobbied in the past and for what. Thirdly, lobby registers also provide information about other lobbyists, including information about a competitor’s goals, activities, clients, targets, and resources. Specifically, the disclosed information might help lobbyists to identify whose interest competitors are representing (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2019). This information might be so valuable to a lobbyist that it influences his or her behavior. Fourthly, the information on lobby registers might also be used to select potential partners. Finally, all this information affects the refinement of a lobbyist’s strategies (or tactics), which would in turn concern both inside (direct contact through face-to-face meetings, calls, letters, and emails) and outside strategies (indirect contact through protest or traditional or social media).

The discussion above leads to the expectation that lobbyists consume the information contained in lobby registers and that this consumption is related to aspects of the advocacy process as described by Mahoney (Reference Mahoney2008). The following sections explore this expectation using data from a survey of 300 Irish interest groups registered with the Irish lobby register (Lobbying.ie). The case selection is described, the survey methodology is explained, and the data are presented.

Case selection and data

Ireland was chosen as a case study for two main reasons. First, its small but growing lobbying industry shares many characteristics and trends with the bigger European lobbying environment. Second, its lobbying regulation – classified as medium-robust in recent studies – is typical of current trends found in other regulated European countries (Chari et al., Reference Chari, Murphy, Hogan and Crepaz2019).

Traditionally, the main interest groups in Ireland have been sectional organizations, that is, representatives of capital, labor, and agriculture in the framework of neo-corporatism. As in other European countries, however, neo-corporatism in Ireland has disappeared, making space for competitive pluralist lobbying (Murphy, Reference Murphy2010). Today’s Irish system of interest representation encompasses a complex and professionalized lobbying industry. Although an official headcount of interest groups by category does not exist, studies have described the lobbying environment as similar to that of other European political systems. In a survey conducted of a sample of interest groups in five European countries, Dür and Mateo (Reference Dür and Mateo2012) found similarities between the Irish interest-group population and those in other countries in terms of ecology and strategies: first, the density of interest groups per group category was similar in all five political systems; second, Irish lobbyists did not differ from their continental counterparts in terms of multilevel lobbying and strategies employed.

The Irish lobbying environment comprises a large non-governmental organization (NGO) sector, a large number of business interests, a small but concentrated agricultural and labor sector, professional associations, and a smaller industry of professional lobbying consultancies and law firms (Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2010). While sectional interest groups remain very important in Ireland, ‘many groups, both sectional and cause-centred, professional bodies, businesses and indeed private individuals have begun to hire lobbyists (as consultants or in-house) and advocate to government on their behalf’ (Chari et al., Reference Chari, Murphy, Hogan and Crepaz2019: 132).

As of April 2019, the Irish lobby register consisted of more than 1700 registered organizations, which have, since 2015, filed 30,632 reports about their lobbying activities. These reports contain detailed information about each lobbying campaign conducted by a registered organization over a 3-month period. Each report contains information about the registered organization, the person responsible for the lobbying activity of the organization, whether the campaign was conducted on behalf of a client, and whether the person responsible for the lobbying has ever been the holder of a public office or a public servant. In addition, the reports provide complete lists of the targets of the lobbying activities (including the names of all members of parliament, ministers, local councilors, civil servants, and special advisors contacted) and a description of the means of communication used (face-to-face meetings, email, phone call, etc.). Registration before lobbying is mandatory, and organizations that fail to register or misreport can incur fines or even become the subject of a criminal prosecution for omission of information or false declarations.

The amount of information disclosed on the Irish lobby register means that it falls under the category of medium-robustness systems (Chari et al., Reference Chari, Murphy, Hogan and Crepaz2019); in other words, it provides a relatively high level of transparency in lobbying, with robust reporting mechanisms, strong enforcement but poor disclosure of lobbying expenditure (Chari et al., Reference Chari, Murphy, Hogan and Crepaz2019). The robustness of Ireland’s lobbying regulations is comparable to that of other medium-robustness systems such as Canada or France and, according to Chari et al. (Reference Chari, Murphy, Hogan and Crepaz2019), is typical of the current European situation. As far as the level of enforcement of these regulations is concerned, Chari et al. (Reference Chari, Murphy, Hogan and Crepaz2019) consider the Irish regulations to be above European standards. According to the Standards in Public Office Commission, which maintains the register, compliance levels with registration rules are high: in its latest report, it says that while there were more than 200 cases of failed or late submission of reports in 2018, no investigation into failed registrations was conducted (SIPO, 2018). The Irish lobby register (Lobbying.ie) is thus the most comprehensive directory of interest groups active in lobbying in Ireland. The use of such a sample frame in this study represents an improvement on previous studies (see, e.g., Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2010), which had to rely on less complete sources, resulting in smaller sample frames.

Irish interest-group population

The data about the use of the Irish lobby register were collected by means of an online survey of interest groups active in the Republic of Ireland. The contact details of the public affairs specialist responsible for each organization’s lobbying activity were retrieved from the publicly available information on the Irish Register of Lobbying. The contact details of more than 1700 actors were collected between 2017 and 2019. This represents the entire interest-group population, which by law has registered on the website Lobbying.ie. For each organization, one contact was identified: the person responsible for the lobbying in the organization. These lobbyists were invited to respond to the survey via email. In some cases, the lobby register listed only email addresses intended for general enquiries (e.g., addresses beginning with ‘info@’). In those cases, the email encouraged the recipient to forward the survey to the person responsible for public affairs in the organization.

To help increase the response rate, the Public Relations Institute of Ireland volunteered to disseminate the survey on its newsletter. Lobbyists who had already taken the survey were discouraged from taking the survey again, but there was no guarantee that this recommendation was followed. To avoid the risk of overrepresenting one interest group, the responses collected with the help of the Public Relations Institute of Ireland were excluded in the robustness checks in Appendix E in Supplementary material.

Overall, 304 of approximately 1800 individuals completed the survey, resulting in a response rate of 17%. This is a deceptively low rate compared with other survey work on interest groups, which score somewhere between 20% and 40% (e.g., Beyers et al., Reference Beyers, Bernhagen, Borang, Braun, Fink-Hafner, Heylen, Maloney, Naurin and Pakull2016). However, it should be noted that such studies report the response rate relative to a sample of the unknown group population, whereas the present work collects information on what should be close to the entire population of inference. Unfortunately, nothing can be said about the non-respondents, as the data collection was completely anonymous and no information was registered about organizations that did not take the survey. Nevertheless, something can be said about the representativeness of the sample of respondents. A more detailed assessment can be found in Appendix A in Supplementary material.

The sample of respondents shows similar characteristics to the population of registered actors as far as some key factors are concerned. Compared to the organizations registered on Lobbying.ie, firms are slightly underrepresented in the sample (see Table 1A, Appendix A in Supplementary material). The largest category of organizations in both groups is public-interest groups, accounting for approximately 40% of the total number of groups. The distribution of business groups matches almost perfectly, but professional associations and law firms and public affairs specialists are slightly overrepresented in the sample. These differences are small, however, and should not give rise to bias in the results.

The sample of respondents closely reflects the geographical distribution of interest groups registered on Lobbying.ie, with almost 60% of the organizations based in Dublin, 35% based outside Dublin, 4% in the UK, and 2% elsewhere in the world (the sample overrepresents this category slightly). The sample of respondents is also representative of the registered lobbyist population as far as policy area is concerned. According to the Irish Register of Lobbying, most of the country’s lobbying focuses on health care, followed by economic development and industry, agriculture, justice and equality, and education and training (SIPO, 2018). The survey’s sample closely follows this distribution, with four of these five policy areas identified as the respondents’ ‘main area of lobbying activity’. Finally, again according to the Irish Register of Lobbyists, the Dáil (Lower House) and the Seanad (Upper House) are the top two lobbied institutions followed by government departments. The same result can be found in the data collected through the survey, which can therefore be considered as representative of the Irish population of interest groups, at least as far as the factors described above are concerned.

The survey

To construct valid indicators, the survey relied on a total of 40 questions concerning three main aspects: (1) the use and purpose of use of lobby registers in Ireland; (2) attitudes toward the lobbying regulation and the register; and (3) organizational and individual characteristics of the interest group and the lobbyist working for each organization. The questions relating to each of the three aspects are discussed below, with descriptive results being presented in this section and in Appendices B and D in Supplementary material.

The first part of the survey asked about the frequency and purpose of use of the lobby register. Since this aspect is central for the study, 10 questions were asked, allowing for the measurement of detail. First, a generic question was asked about whether respondents use the information disclosed on the register in their profession. To explore the precise purpose of that use, nine questions were asked. From a theoretical point of view, the purposes closely relate to the conceptualization of the advocacy process (Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2008): to gain information about the policy-making process; collect information to form an opinion or policy position on a given issue; see what competitors are doing; see whom they are representing; choose lobbying targets; find new clients; find advocacy partners; and decide on and refine inside and outside strategies. Ten lobbyists validated these dimensions of use during the pilot stage of the project. Two of these participants participated in follow-up interviews after the pilot stage. The existence of other uses cannot be excluded. Nevertheless, the pilot stage served to guarantee that those uses under investigation in this study were relevant both theoretically and empirically. All answers were based on a five-point scale ranging from ‘Never’ to ‘Every week’.

The second part of the survey collected lobbyists’ attitudes toward the Irish lobbying regulation. In particular, the survey asked a set of questions concerning the usefulness of the register. Some of these questions will be discussed in the next section. However, since all answers correlated highly with one another, only one is used here to measure attitudes: ‘To what extent do you agree that the Irish lobbying regulation helps you in your profession?’ Answers to this question used a five-point Likert scale, allowing respondents who have a negative attitude toward lobby registers to be distinguished from those who believe it is a useful tool.

The last part of the survey collected data on organizational and individual characteristics of the organization and the person responsible for public affairs. These questions, of which a more detailed description can be found in Appendix B Supplementary material, were used to construct variables employed in the multivariate analysis.

Data

Almost 38% of the respondents said that they use the information disclosed on the register; 62% of the respondents said that they do not use the information. Figure 1 expands on this by showing the purposes of use of the register for all nine questions.

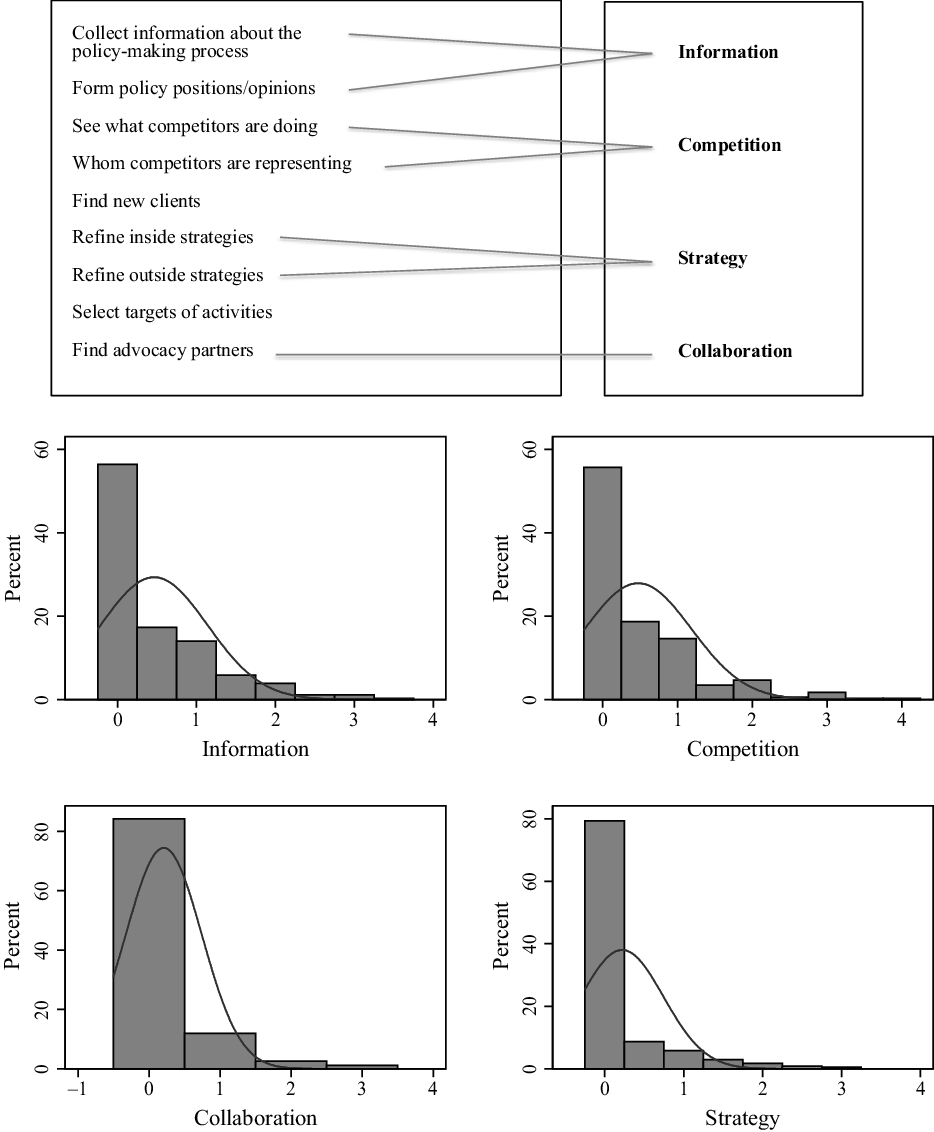

Figure 1. Purposes of use of the Irish Lobby register.

The graph confirms that most respondents do not make very frequent use of the register, even for the purposes of use identified in the survey. The most frequent uses relate to the collection of information about the policy-making process, for which 37% of the respondents claimed a use of ‘at least once a year’. Forty-two percent of the respondents stated that they use it to observe competitors ‘at least once a year’. For other purposes, such as ‘collect information to form a policy position’ or ‘to find new clients’, uses range from 26% to 5% (for a frequency of ‘at least once a year’).

With the data shown in Figure 1 in mind, one might expect to find strong associations between these dimensions of use. The collection of information about the policy-making process and the retrieval of information to form policy positions might go hand in hand. Moreover, there may be a correlation between the use of the register for refinement of inside and outside strategies. With the aim of simplifying the description of the data and reducing the numbers of dimensions of use, an exploratory factor analysis of all dimensions was conducted. Table 2A in Appendix C Supplementary material shows that the nine dimensions of use can be reduced to three, and Figure 2 shows how the factor loadings relate to one another.

Figure 2. Factor loadings for three dimensions of use.

The first factor, which is here called the informational dimension, contains the purposes of use ‘gain information about the policy-making process’ and ‘collect information and form an opinion/policy position on a given issue’. This dimension relates to the parts of the advocacy process concerning mobilization and position taking (Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2008). The second factor, competition, loads ‘see what competitors are doing’ and ‘see whom they are representing’ and concerns processes related to counter-mobilization and counter-lobbying (Lowery et al., Reference Lowery, Gray, Wolak, Godwin and Kilburn2005). The third factor, called the strategy dimension, includes decisions concerning lobbying tactics and combines the purposes of use ‘decide about and refine inside strategies’ and ‘decide about and refine outside strategies’ (Weiler and Brändli, Reference Weiler and Brändli2015). To these three factors is added a fourth, conceptually different from the others and comprising a single element of purpose, namely, ‘find advocacy partners’ (a uniqueness factor of 0.5). This relates to an aspect of the advocacy process which concerns the formation of coalitions and partnerships between lobbying actors (Klüver, Reference Klüver2013). These four dimensions represent separate aspects of the advocacy process and have been extensively studied in the literature. Their construction is summarized in Figure 3. The distribution of the frequency of use for each dimension is also shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Four dimensions of use and their distribution.

As Figure 3 shows, the distribution of the frequency of use is skewed toward zero, meaning that the majority of the respondents do not use the information disclosed on the register. The frequencies of use range from ‘once a year’, indicated by number 1, to the less common category of ‘every week’, indicated by number 4. This tendency is more prominent for the dimensions of competition and information, which are less skewed than those of strategy and collaboration.

Are these dimensions of use relevant for the legitimacy of the lobbying sector? Answering this question is relevant to the justification of this study: if it is found that all interest groups find lobby registers useless for their profession, then further investigation into the determinants of use would not contribute to the understanding of the advocacy process. The data revealed that 47% of the respondents find the lobby register at least somewhat helpful, with 18% of them finding it ‘helpful’ or ‘very helpful’. Almost 27% of the respondents find the use of the register ‘helpful’ or ‘very helpful’ for their reputation, suggesting that registration is perceived to provide some form of legitimacy to the industry. Almost 69% of the respondents believe that the register makes lobbying visible to the public, and 54% believe that this makes the government more accountable for its decisions.

These data suggest that lobbyists are not indifferent to lobbying rules. On the contrary, they believe that registers help to improve transparency and accountability in government and that the same regulatory tools can provide democratic legitimacy to their profession, which is often seen with suspicion. It must be said that most (53%) of the surveyed organizations do not find the register helpful. However, one might argue that these respondents are those that lobby less frequently and therefore have fewer reputational concerns. This is confirmed by a Spearman correlation test between the variables perceived level of helpfulness of the register (ordinal scale from 1 to 5) and volume of lobbying activity (composite count of total lobbying activities conducted over 1 year; see Appendices B and D in Supplementary material), which finds a positive and significant relationship between the two variables (ρ = 0.17, P = 0.0037***). This finding raises the question: Who uses the register for the purposes discussed in this section? Building on the literature on the advocacy process, the next section formulates expectations for the use of the register for general, informative, competitive, collaborative, and strategic purposes.

Who uses the register? Hypotheses

It is unlikely that all interest groups make equal or similar use of the information disclosed on lobby registers. Group characteristics might be associated in varying degrees with the frequency and purpose of use of such information. The association might even depend on the purpose of use.

General use

There are no strong theoretical reasons to believe that one interest group might use lobby registers more than another (without specifying the purpose of such use). It can be argued, however, that there are at least two pre-conditions under which interest groups are more likely to use the register.

First, interest groups that lobby more frequently are more likely to use the information disclosed on the register because they access the register more frequently to file reports about their activities. This might give them more opportunities to consume the information in relation to the advocacy process. This is less true for organizations that lobby only occasionally. Such organizations are less accustomed to lobby registers and will therefore find them a less useful source of information.

Previous research has, however, discussed the way in which interest groups that are more active in policy-making than others can be treated as policy insiders (Maloney et al., Reference Maloney, Jordan and McLaughlin1994). In the framework of neo-corporatism, for example, organizations that often participate in advisory committees or benefit from a privileged position in the decision-making process through institutionalized platforms of negotiation might not need to check the register because they already have the information they need (Fraussen et al., Reference Fraussen, Beyers and Donas2015, Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Pedersen and Beyers2017). A negative relationship between use and lobbying activity is therefore equally plausible.

Second, it is expected that lobbyists who believe that registers are helpful in their profession are more likely to use registers than those who do not. The general rule in behavioral economics is that negative attitudes toward rules inhibit compliance with the rules and thus hamper their successful implementation (Jensen and Aarset, Reference Jensen and Aarset2008). In particular, if rules are not perceived as legitimate and useful, then compliance is inhibited (Jagers et al., Reference Jagers, Berlin and Jentoft2012). The same logic can be applied to lobbying regulations. Scholars have already stressed that a general positive attitude toward lobbying rules promotes transparency and compliance in the case of voluntary regulations (Bunea, Reference Bunea2018; Năstase and Muurmans, 2018; Bunea and Gross, 2019). Similarly, even in the case of mandatory rules of registration (violations of which would incur sanctions), lobbyists with a negative view of lobbying regulations, who believe that registers are neither legitimate nor useful for their industry, might be less likely to access registers than lobbyists who believe that registration helps their profession. There is a problem of endogeneity here, as lobbyists might find registers useful because they have used them before. This problem is addressed in the results section.

More detailed expectations can be formulated when the specific purposes of use of the register are considered. Building on the literature, hypotheses are presented below about the use of the register for all four purposes.

Information

Information is key in lobbying, and research concerning the ways in which the quality, nature, and transmission of information determine access or even influences it is central to interest-group politics (Austen-Smith and Wright, Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1994; Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2013). The process of information retrieval, preceding its transmission, is still understudied, however. In particular, if and which interest groups retrieve information from lobby registers to support the advocacy process is still uncharted territory. Nevertheless, it is theorized that this process can be explained by factors that are well studied in the literature on information and lobbying.

First, group type matters (Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2016). Classic interest mobilization theory suggests that different interest-group types face different collective action problems when they engage in politics (Olson, Reference Olson1965). Because their existence is based on an ideology or a shared set of values, cause-centered organizations, such as NGOs and charities, ‘find it easy to position themselves on policy issues’ (De Bruycker et al., Reference De Bruycker, Berkhout and Hanegraaff2019: 295). Sectional interest groups (business and professional associations), in contrast, are not based on close policy alignment between members, and they need to go through internal negotiation processes in order to formulate their policy positions (De Bruycker et al., Reference De Bruycker, Berkhout and Hanegraaff2019). Even organizations with a narrower or no membership, such as firms, need to invest resources to form policy positions. They might need to assess the interests at stake to decide whether or not to mobilize. The political action of such organizations reflects the ‘internal management of heterogeneous actors and market competitors motivated by (economic) self-interest, which necessitates ensuring all constituents that their heterogeneous and sometimes conflicting self-interests are accounted for’ (De Bruycker et al., Reference De Bruycker, Berkhout and Hanegraaff2019: 301). Such internal dynamics can include bargains over preferences, discussion of advocacy strategies, and collection of information on policy issues and policy alternatives. In this situation, lobby registers might offer sectional interest groups and firms the opportunity to collect information for the purpose of facilitating the formation of policy positions (e.g., for or against the status quo). By contrast, public groups should be less likely to use such resources for this purpose, since they are in principle already informed about the activities that concern their cause.

A second consideration concerning the use of registers involves organizational resources. While group type has in the past been used as a proxy for resources, more recent studies have found much variation in the level of resources within and across group types (Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2016). Better-endowed interest groups tend to dominate interest representation, at least as far as access to political institutions is concerned (Rasmussen and Carroll, Reference Rasmussen and Carroll2014). Material resources, such as money and human capital, empower political activity, allowing for access to government institutions. There are several reasons for this. First, higher organizational capacity makes the maintenance of a specialized government-affairs department possible (Lowery, Reference Lowery2007). Second, larger budgets allow organizations to hire professional and specialized lobbyists with deep understanding of the decision-making process. Organizations with large material resources are thus more likely to have staff informed about what is going on in government, which policies are being debated, and whether they are being lobbied. For organizations that cannot afford to maintain a government-affairs department and do not have many resources to employ in lobbying, keeping up to date with government affairs is more challenging. As a result, if lobby registers provide interest groups with free information about issues being lobbied and the decision-making process, it is reasonable to assume that organizations less-endowed with material resources will be more likely to use such a non-material resource.

Experience in public office is expected to be another key factor. Organizations employing lobbyists that, in the past, served as elected or non-elected officials have the advantage of having a foot in the door of policy-makers, thanks to insider-knowledge, subject matter expertise, and political connections (LaPira and Thomas, Reference LaPira and Thomas2014). Recent research has suggested that the political knowledge of ‘revolvers’ and their insider connections contribute to lobbying success (Strickland, Reference Strickland2019). Given their insider status, they are expected to consume less of the information disclosed on lobby registers. Their connections in government institutions and their knowledge of decision-making processes should exempt them from the necessity of collecting additional information about the policy-making process.

Strategy

Lobbying strategies determine the way in which the lobbyists’ messages are delivered. Scholars differentiate between inside and outside strategies. Inside strategy refers to ‘lobbying activities that are directly aimed at policy-makers’ (Hanegraaff et al., Reference Hanegraaff, Beyers and De Bruycker2016, 569). This includes face-to-face meetings, phone calls, letters, emails, and texts. Outside strategy refers to all communications addressing public opinion and aimed at exercising indirect influence on policy-makers, for example, reaching out to media, campaigning on social media, protests, and boycotts (Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2016). Choosing the most adequate strategy is an important step toward lobbying success. Previous studies have found a relationship between the choice of inside and outside strategies and group characteristics (Weiler and Brändli, Reference Weiler and Brändli2015; Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2016), the institutional context (Beyers, Reference Beyers2004; Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2008), issue characteristics (Beyers, Reference Beyers2008), policy type (Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2016), and resources and competition thereof (Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2016; Hanegraaff et al., Reference Hanegraaff, Beyers and De Bruycker2016). Nevertheless, the ways in which lobbyists make such a choice remain under-theorized. It is argued here that, when information about the advocacy process is accessible on lobby registers, interest groups with fewer resources will find the information useful in choosing and refining their strategies.

With lobbying comes a degree of uncertainty in the outcome: lobbyists can never be sure which strategy best serves their objective. Certainly, experience, knowledge, intuition, and even ‘touch’ can help reduce this uncertainty (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2019). Resource-rich organizations might reduce this uncertainty with a melius abundare quam deficere approach, that is, the employment of more resources into a variety of different strategies to achieve their goals. When resources are scarce, however, a more calculated approach to strategy choice should be taken. On the one hand, an organization with low organizational capacity might invest its resources in inside strategies if public office-holders have been particularly open to direct communication with interest groups. On the other hand, it might decide to refine its outside strategy if the government’s doors have been closed. Similarly, for a resource-poor organization, it is important to see if certain proposals or issues have been lobbied before and how. This might determine whether it concentrates all its resources into an outside strategy to raise public awareness or uses its scarce resources to lobby policy-makers directly (or a combination of the two). Given that this information is available and retrievable from lobby registers, less-endowed organizations may be expected to use it for strategy refinement.

Furthermore, the extent to which an organization employs a ‘revolver’ is expected to affect the use of lobby registers for strategic purposes. For an organization, the benefit of hiring a revolving-door lobbyist derives from the person’s expertise in the policy area and his or her ability to rely on an insider network of public officials (LaPira and Thomas, Reference LaPira and Thomas2017). Given this advantage, the development of the lobbyist’s strategy is more likely to depend on contacts in government and knowledge of the policy-making process rather than on information on public registers. As a result, revolving-door lobbyists should be less likely to use lobby registers for strategic purposes.

Competition

Studies have tended to find a strong association between influence and competition. Population ecology literature, for example, explores the ways in which competition shapes access to opportunities. In dense interest communities, organizations tend to lose access as competition increases, whereas the opposite is true for less crowded interest representation systems (Lowery and Gray, Reference Lowery, Gray and Lowery2015). In line with niche theory, specialization in interest representation and the employment of more resources in lobbying can create an access advantage in competitive environments (Hanegraaff et al., Reference Hanegraaff, van der Ploeg and Berkhout2019). Similarly, lobby registers might play a role in these processes.

The possession of knowledge about your competitor is a key component of any business strategy. Likewise, the understanding of competitors in the system of interest representation is central for an organization’s lobbying activity. However, while interest groups with high organizational capacity might be less concerned about the lobbying campaigns of competitors, weaker organizations will need to fill the gap to their competitors if they want their voices to be heard. Lobby registers can provide these organizations with details of the present and past activities of competitors, helping them to decide how to develop their campaign, the timing of their lobbying, and their counteractive lobbying. As a result, less-endowed organizations are expected to use the register for competitive purposes more frequently than resource-rich organizations.

The same association might be expected for public affairs firms. These are professional consultancies that operate as ‘hired guns’. Their success is based on their ability to attract and represent clients. They are therefore expected to be the most frequent users of the register for competitive purposes. The register allows them to see what their direct competitors (other public affairs firms) are doing and whom they are representing.

Collaboration

Research has shown that interest groups often form partnerships with the aim of increasing their chance of influencing public policy (Klüver, Reference Klüver2013). These partnerships can be ad hoc or more durable (Gray and Lowery, Reference Gray and Lowery1998). Regardless of the type of partnership, studies have shown that public interest groups tend to engage more frequently in these coalitions than other organizations (Klüver, Reference Klüver2013; Hanegraaff and Pritoni, Reference Hanegraaff and Pritoni2019). This strategy allows them to pool resources, broaden their basis of representation, increase the legitimacy of their cause, and increase the chances of the lobbying activity succeeding (Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2008). Interest groups do not engage in coalitions without reason; partnerships are based on ideological affinity, alignment of policy preferences, and even strategic considerations about resources and tactics (Klüver, Reference Klüver2013). Accessing information about potential partners is therefore necessary before coalitions are formed.

With this in mind, lobby registers allow organizations to browse through organizations’ activities and policy positions, thus offering the opportunity to find like-minded interest groups and potential advocacy partners. Given that public interest groups are more likely to engage in this type of political action, they might also be more likely to use registers for collaborative purposes. Similarly, if strength lies in numbers, then less-endowed organizations should also be more likely to use the register for collaborative purposes. This would allow them to reduce the costs of finding and forming partnerships with like-minded organizations.

Overall, this section has argued that the use of the information disclosed on lobby registers varies with different interest-group characteristics. Table 1 summarizes the main hypotheses.

Table 1. Hypotheses for general use of register and four dimensions of use

Analysis

This section tests the hypotheses presented above using multivariate regression analysis. The analysis employs two groups of dependent variables (DVs). The first variable, use, is a dichotomous variable which takes the value of 1 if the respondent has stated that they ‘use the information disclosed on the register’ and 0 otherwise. The second group of DVs consists of four count variables relating to the dimensions of use of the register shown in Figure 3. For each dimension of use, if a respondent indicates that they have accessed the register for a specific purpose once a year, this counts as ‘one’ access; if they indicate that they have accessed it once every 3 months, this counts as ‘four’ accesses, and so on. This approach results in four count variables regarding how often lobbyists have accessed the register for the specific purposes of information, strategy, competition, and collaboration over the course of 1 year.

The first DV (use) was explored using a logistic regression model. Given the skewed distribution of the variables, the DVs for each dimension are explored using negative binomial models. The regression analysis fits the following independent variables: group type, lobbying budget, organizational capacity, volume of lobbying activity, positive attitudes toward regulations, and revolving door. To account for group type, a variable grouping responses into five interest-group categories was constructed (business association, professional association, firm, public interest group, and public affairs firm). Two variables measure an organization’s resources: lobbying budget indicates whether the budget of the organization employed for lobbying is less than €10,000, between €10,000 and €100,000, between €100,000 and €500,000, between €500,000 and €1 million, or above €1 million. The variable organizational capacity is an additive index based on the answers to a set of questions that measure the internal complexity of the organization (see Crepaz and Hanegraaff, Reference Crepaz and Hanegraaff2020). While lobbying budget accounts for the monetary resources of an organization employed in lobbying, organizational capacity measures its overall resources (secretariat, accountancy department, public affairs, etc.).

The volume of lobbying activity variable is a count variable constructed in the same way as the DV, but it measures the frequency of direct and indirect lobbying activities of the organization over the last year. This variable accounts for the levels of lobbying activity of an organization. The variable positive attitudes toward regulations is based on the responses to the question ‘Does registration help you in your profession?’, using a five-point scale. Finally, the extent to which an organization employs a revolving-door lobbyist is measured with the variable revolving door, a dichotomous variable that equals 1 if the lobbyist has previously occupied the position of public office-holder or advisor (0 otherwise). Table 3A in Appendix D Supplementary material presents a description and the summary statistics for each variable.

Table 2 shows the results of the logistic and negative binomial regression model.Footnote 2 Negative binomial distribution is preferred to Poisson distribution because of overdispersion in the DV. A goodness-of-fit test confirmed the better fit of the negative binomial model compared to the Poisson model. To account for potential heteroskedasticity related to the policy fields in which organizations are active, clustered standard errors were included to obtain unbiased standard errors of the coefficients, based on the 17 policy fields listed on the Irish register of lobbyists.

Table 2. Logit and Nb regression models explaining use and purpose of use

Irr. = incidence rate ratio.

Clustered standard errors in parentheses.

***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1.

General use

The results of the logistic regression show that the use of the register is best explained by the variables volume of lobbying activity, positive attitudes toward regulations and revolving doors. As Figure 4 (center) shows, for organizations that rarely lobby (0), the probability of making use of the information on the register is almost 60% lower than that of organizations lobbying frequently (almost 300 actions including direct and indirect contacts). This confirms the validity of Hypothesis 1, which predicted that more active lobbyists use the lobby register. Organizations that never, or seldom, lobby are less likely to access the lobby register and would therefore be less interested in obtaining information for their advocacy strategy. The fact that structures of privileged access, such as those put in place by social partnership in Ireland, have declined since 2006 might explain why Hypothesis 1a is disconfirmed. In the post-social partnership era, even traditional policy insiders, such as the Irish employer confederation Ibec, might find the access to lobby registers useful in their profession. The process of professionalization undergone by the lobbying industry since 2010 might help explain such phenomenon (Chari et al., Reference Chari, Murphy, Hogan and Crepaz2019).

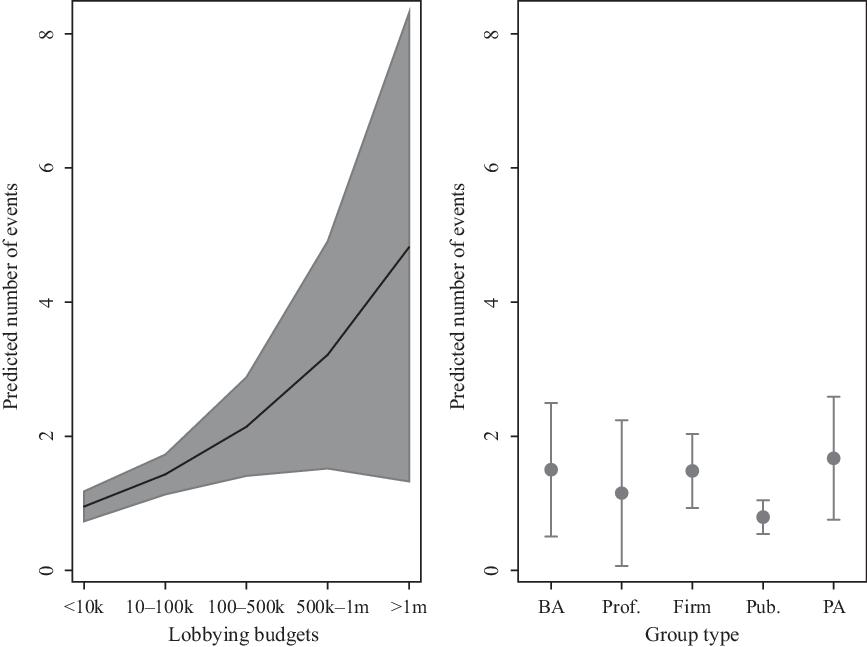

Figure 4. Predictive margins for Model 1 (Table 2).

A significant effect, confirming Hypothesis 2, is observed when lobbyists with positive attitudes toward lobby regulation are compared with lobbyists with negative attitudes toward regulation (Figure 4, left). This result is consistent across the regression models investigating purposes of use (Models 2–5), confirming the robustness of the results. It would be unreasonable to expect confrontational lobbyists to make more use of lobby registers, as they should be less familiar to the use of lobby registers. This problem of reverse causality prevents the causal path between the variables from being disentangled. It might in fact be that the increased use of the lobby register generates positive attitudes toward the rules. Similar findings have been discussed in recent studies on voluntary clubs and voluntary rules, which found that normative values about transparency in lobbying help to explain compliance with the rules of the transparency register of the EU (Năstase and Muurmans, Reference Năstase and Muurmans2018; Bunea and Gross, Reference Bunea and Gross2019). The finding in the present study adds to this topic by showing that the same attitude might explain the extent to which transparency rules shape ‘the behaviour and performance of lobbyists’ (Năstase and Muurmans, Reference Năstase and Muurmans2018: 3), an aspect that the same authors claim to be unexplored in the current literature. Future research is therefore needed to resolve the causal link between attitudes and use of the register.

Finally, and against the general expectation, Figure 4 (right) shows that revolving-door lobbyists are almost 20% more likely to use the register than non-revolvers. Given the unexpected direction of the relationship, the effect of this variable is further discussed in relation to Models 3, 4, and 5, and Hypothesis 5 and Hypothesis 7, which predict that revolving-door lobbyists make less use of the register for informational and strategic purposes.

The analysis conducted so far does not reveal associations between independent variables and the frequency of use according to the four purposes (competition, information, strategy, and collaboration). Table 2 presents the results of the regression analyses, which fit independent variables using the four dimensions of use as DVs. Table 2 presents the incidence rate ratios, and the size of the effects is shown in Figures 5, 6, and 7.

Figure 5. Predictive margins for Model 3 (Table 2).

Figure 6. Predictive margins for Model 4 (Table 2). BA, business association; Prof., professional association; Pub, public interest group; PA, public affairs.

Figure 7. Predictive margins for Model 5 (Table 2).

Information

The results of the negative binomial model provide a complex picture of the use of registers. According to Hypothesis 3, sectional interest groups were expected to use the register to collect information and to form their policy positions more often than cause-centered organizations. However, this does not seem to be the case in the data. More importantly, among sectional interest groups, professional associations seem to make less use of informational data, as do public affairs firms. While this result might make sense for public affairs firms, given their specialized knowledge of the policy-making process, no obvious reason can be found to explain the result regarding professional associations. A possible answer might lie in the modus of their advocacy activity vis-à-vis other interest groups. Even when different group types are used as a reference category, the results suggest that the retrieval of information from the register to ease the process of policy-positioning does not seem to differ between business associations, firms, and public organizations, thus disconfirming Hypothesis 3. This finding might be best explained by the literature on business lobbying. As opposed to encompassing business associations that represent a variety of sometimes contrasting interests, sectorial business associations and firms might have very clear policy positions regarding specific policy areas (Dür et al., Reference Dür, Bernhagen and Marshall2015). Financial lobbyists, for example, tend to have clear preferences over regulatory intervention (Woll, Reference Woll2013). An assessment of the use of the register to formulate an organization’s policy position is therefore not possible without a careful examination of the organization’s interest at stake. Future studies might consider distinguishing between encompassing and sectorial business associations to provide a first assessment of this process.

The finding concerning lobbying budgets complicates the overall picture. The regression analysis found a positive association between resources spent on lobbying and use of the register for informational purposes. This disconfirms Hypothesis 4 and forces a reconsideration of the association between resources and use of the register: larger lobbying budgets are associated with greater professionalism. It may be the case that highly professionalized lobbyists are also more accustomed to lobby registers and might therefore use them as a source of information about government policy-making.

Finally, Model 2 did not find a significant association between revolving-door lobbyists and the use of the register for informational purposes. This disconfirms Hypothesis 5 and is in contrast with the positive association found in Model 1. A positive association is found in Models 3, 4, and 5, which are discussed next.

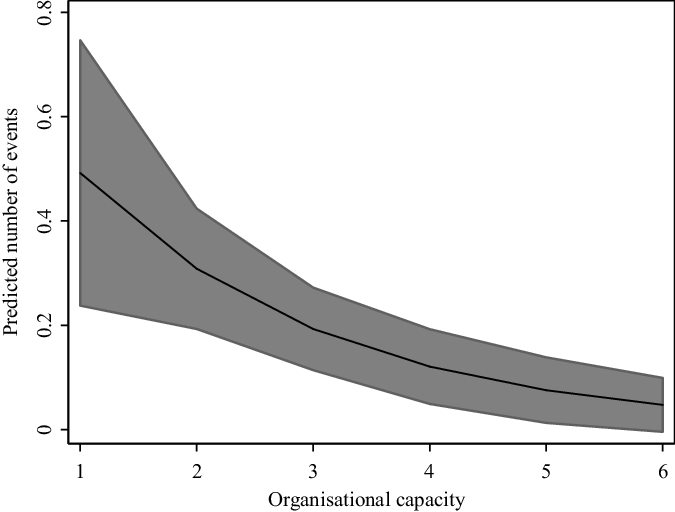

Strategy

Model 3 shows the associations between independent variables and the use of the register for strategic purposes. Hypothesis 6 hypothesized that less-endowed organizations would use the register more frequently for strategic purposes than resource-rich organizations. The analysis weakly confirms Hypothesis 6. The association between level of organizational capacity and use of the register is negative but weakly significant (P = 0.051*). The size of the effect is moderate, predicting a change in the DV of less than 1, and accounts for a change in the independent variable from its minimum to its maximum value (Figure 5, left). As will be discussed later, the association between organizational capacity and use of the register is strongest when collaborative purposes are considered. However, the size of the effect remains moderate.

The coefficient for the variable revolving door is again positive and statistically significant, confirming the results of Model 1 but disconfirming Hypothesis 7, which predicted a negative association between an organization’s strategy use of the register and its hiring of a revolving-door lobbyist. Nevertheless, Figure 5 (right) reveals an important nuance: confidence intervals are narrow when the variable value is 0 and wide when it is 1. As a result, lobbyists who do not have previous experience in government do not use the register for strategic purposes; however, revolving-door lobbyists seem to take a more varied approach. This uncertainty of the estimation might be caused by the relatively low number of revolving-door lobbyists in the data (15%) and in the industry more generally (11%). This finding should be interpreted with care, as should the results found in Models 4 and 5 concerning competition and collaboration. Nevertheless, interest-group scholars will find it interesting to observe that revolving-door lobbyists retrieve information from the lobbying register on average almost three times more frequently than other lobbyists, considering that the former tend to have information advantages over the latter. This result calls for specific studies to explore the ways in which revolving-door lobbyists conduct their advocacy activities in comparison with lobbyists with no experience in government. The growing interest in ‘revolving doors’, even in Irish politics, represents a solid basis for future research (Baturo and Arlow, Reference Baturo and Arlow2018).

Competition

Hypothesis 8 hypothesized that less-endowed organizations would be more concerned about competition than resource-rich organizations and would therefore be more likely to use the register to see what their competitors were doing and who they were representing. Model 4, however, finds an opposite and statistically significant effect. The use of the register for competitive purposes seems to increase as the lobbying budget of an interest group increases (see Figure 6, left). Confidence intervals are wide for high values of the independent variable because few organizations in the data have lobbying budgets larger than €500,000. Even so, the model predicts a 1 count increase in the DV for a change in the lobbying budget from less than €10,000 to €500,000. The register therefore seems to be a weapon of the resourceful.

As far as differences between group types are concerned, Model 4 shows that, as predicted by Hypothesis 9, public affairs firms are more likely to use the register for competition purposes than public groups (Figure 6, right). Unexpectedly, business associations and firms make more frequent use of the register for this purpose than public groups. It might be the case that government-affairs divisions of business associations and firms find the register useful to justify their advocacy strategy in front of directors. Taking a firm as an example, the head of corporate affairs at Vodafone might justify the company’s policy position to the management based on their competitors’ positions on a given issue. In this situation, information about competitors’ lobbying activities could be retrieved from lobby registers. This mechanism might be less relevant for communication directors working in NGOs, such as Greenpeace, who coordinate advocacy strategies based on campaigns.

Collaboration

Contrary to Hypothesis 10, public groups do not use the register for collaborative purposes (Model 5). When resources are considered, however, Model 5 suggests that the collaborative dimension is negatively related to organizational capacity (Figure 7). Interest groups with low organizational capacity are almost 50% more likely to use the register to find advocacy partners (which confirms Hypothesis 11). A similar finding was observed in relation to the strategy dimension. While the size of effects remains small, the direction and significance of the relationship indicate that the information on the register facilitates the process of collaboration and strategy for less-endowed organizations. The lobbying budget of an organization, in contrast, does not seem to be associated with this dimension of use of the register.

Conclusions

The goal of this study was to assess if and which organizations use lobby registers and for what purposes. The results of the study draw a complex picture. While many of these correlations make logical sense, all of them need further exploration and assessment. In light of the findings, it is undeniable that a small but well-defined minority of organizations and lobbyists use the Irish lobby register in relation to four dimensions of the advocacy process: strategy, information, competition, and collaboration. While there might be other dimensions of use, the evidence presented here should encourage scholars to consider the transparency policy as an explanatory variable of the advocacy process. The study also provides key insights into an important dynamic of the advocacy process, namely, competition vs. collaboration. While previous studies have explored competition as a situation of opposed policy positions (McKay and Yackee, Reference McKay and Yackee2007; Bombardini and Trebbi, Reference Bombardini and Trebbi2012) and collaboration as the formation of coalitions or partnerships around similar policy positions (Klüver, Reference Klüver2013; Beyers and De Bruycker, Reference Beyers and De Bruycker2018), this study stresses a relational aspect, which precedes the visible act of counter-active lobbying and coalition formation: actors spying on and searching for one another. The availability of free information seems to facilitate such a process.

The process described in this paper is endogenous, since lobbying activities might encourage more use of the lobby register and, at the same time, more use of such information might promote more lobbying. Future studies should therefore try to make sense of the direction of causality with a more detailed exploration of the relationship between transparency and the advocacy process. Such findings might provide valuable insights into how information shapes the stages of the advocacy process. Future research could also explore new dimensions of use of lobby registers. Studies have already shown, for example, that organized interests tend to strike a balance between inside and outside strategies (Hanegraaff et al., Reference Hanegraaff, Beyers and De Bruycker2016). Future studies might therefore investigate the association between the use of registers and more specific lobbying tactics.

The study of the effects of transparency on lobbying could not and should not be limited to lobby registers. Legislative footprints, public online consultations, and the disclosure of politicians’ agendas are examples of how transparency is permeating the profession of lobbyists. Given that research has already shown that interest groups have clear preferences about levels of transparency (Bunea, Reference Bunea2018; Năstase and Muurmans, Reference Năstase and Muurmans2018), it would be naïve to argue that such transparency does not affect their profession. More research is therefore needed in this area.

Finally, this study is also important for policy-makers and lobbyists. The data show that lobbyists are among the users of the Irish lobby register and that such use potentially supports their profession. Given that governments passing such regulations recognize lobbying as a legitimate and necessary aspect of democratic governance, it could be beneficial for them to design lobby registers in such a way as to promote as much participation as possible. This study shows that only a few practitioners use the information disclosed on lobby registers, some of whom are already insiders. However, registers could be designed to support both public scrutiny and lobbying activity, especially for those interest groups that grapple with access to government (Fraussen and Braun, Reference Fraussen and Braun2018). After all, as a lobbyist said in an informal interview conducted during the pilot stage of this project, lobby registers serve as ‘the LinkedIn’ of the lobbying community. Some regulations, such as the Joint Transparency Register of the European Union, have already linked rules to an incentive structure.Footnote 3 Regulators might consider improving their registers by implementing such incentive structures.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773920000156.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers as well as the editors for their constructive comments and suggestions on earlier versions. I would also like to thank Gizem Arikan, Raj Chari, and Marco Schito for their support. I am particularly indebted to Martina Byrne and PRII, Brian and Clodagh for their help with the survey. Finally, I thank the Irish Research Council, which funds this project.