Introduction

In this paper I present a framework for the conceptualization of language, based on the prototype theory of categorization proposed by Eleanor Rosch and her colleagues for natural semantic categories (Rosch, Reference Rosch1973, Reference Rosch1975a, Reference Rosch, Brislin, Bochner and Lonner1975b; Rosch & Mervis, Reference Rosch and Mervis1975; Rosch, Mervis, Gray, Johnson, & Boyes-Braem, Reference Rosch, Mervis, Gray, Johnson and Boyes-Braem1976 inter alia). It is inspired by research in the Casamance region of southern Senegal, where a situation of small-scale multilingualism (Lüpke, Reference Lüpke2016b; Singer & Harris, Reference Singer and Harris2016) prevails. This manifests in the maintenance of many named, but unstandardized, languages, with varying degrees of relatedness to each other, and which are spoken for different purposes by each person, and where each interaction involves a unique constellation of languages and sociolinguistic factors. It is observed that while named languages can, to varying degrees, be distinguished according to linguistic factors, the prevailing approach to linguistic description can obscure much of the nature of language use, as it is not able to effectively account for fluidity and variation (Lüpke, Reference Lüpke and Wolff2017b).

I propose that languages can better be modelled using principles from prototype theory, which facilitate more accurate and flexible descriptions based on both the elicited judgements and observed usage of speakers, and both allow and account for variation. Such descriptions can enable an analysis of multilingual discourse whereby individual linguistic featuresFootnote 1 are interpreted within the sociolinguistic context in which they are uttered. In the following section (1), I discuss some of the research perspectives pertaining to linguistic description and multilingualism studies, and argue that both a purely structuralist and a strong variationist standpoint have inadequacies that must be resolved through a dialectic approach. In Section 2 I introduce the multilingual setting of Casamance, and discuss how high levels of linguistic variation and fluidity co-exist with essentialist and conservative language ideologies. In Section 3 I introduce relevant principles of the prototype theory of categorization, and how these can be applied to linguistic description in a way that avoids inaccuracy and erasure, accounts for variation, and includes different perspectives. In Section 4 I discuss the type of data that must be collected in order to model a language in this way and in Section 5 I illustrate how the approach can be used to describe two closely related Joola languages. Finally in Section 6 I bring together all these concepts to demonstrate how they can be applied to the analysis of multilingual data.

1. Linguistic description and multilingualism

At least since Weinreich (Reference Weinreich1954) called for a structural dialectology, a tension has been observed in linguistic research, between a concern with describing the structure and ‘rules’ of a language, and one with describing variation and deviation from those same rules. This discussion is of particular relevance to the field of African linguistics where the descriptive tradition has generally tended towards structuralism and erasure of variation which reflects poorly the fluid multilingual practices that are the norm across most of the continent (Blommaert, Reference Blommaert, Helinger and Pauwels2008b; Lüpke, Reference Lüpke2010a, Reference Lüpke and Wolff2017b; Lüpke & Storch, Reference Lüpke and Storch2013). Nevertheless, while detailed studies of variation are crucial to understanding language use in these contexts, some sociolinguistic work on (African) multilingualism has swung to the opposite extreme, denying the very existence of reified codes, a view which is inconsistent in its own way, as well as being unhelpful in developing a strategy for the study of multilingual language practice. I argue that a conceptual paradigm is required that combines elements of both perspectives to comprehensively account for both structure and variation.

African linguistics has traditionally been dominated by descriptions of languages that treat languages as fixed, monolithic entities that can be captured by listing vocabulary and grammatical rules (Lüpke, Reference Lüpke, Essegbey, Henderson and Mc Laughlin2015). As (Blommaert, Reference Blommaert2008a, p. 292) points out, any description involves not only the reduction of the language in question into a series of words and rules, but itself conforms to a “regimented form of textuality”. Any grammar or description of a named variety – or varieties in the case of multilingual descriptions – must, by its very nature, essentialize and artefactualize languages in a way that reduces “the fantastic variation that characterizes actual language in use … to an invariable, codified set of rules, features and elements” (p. 292). They necessarily result in ERASURE (Irvine & Gal, Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000, p. 38), not only of linguistic features, but of all the rich sociolinguistic context that contributes to language use in such settings. Furthermore, early descriptions by missionary and colonial linguists carried substantial ideological baggage that further distorted the facts. They were influenced by a strong link (in Europe) between language and nationhood (see Haugen, Reference Haugen1966), with a concomitant emphasis on the superiority (and a presupposition of the existence) of pure or standard forms (Irvine, Reference Irvine1995). Thus, such descriptions mirror the grammars of ancient and modern European languages; lists of grammatical rules and vocabulary with little or no attention paid to variation or multilingualism, much less to actual language practice. Furthermore, it is a regrettable fact that the beginning of linguistic research in Africa is contemporaneous with occupation and colonialism, and that the politics of language and linguistic research are intertwined to this day with concepts of oppression, social control, and power balance (Juffermans, Reference Juffermans2015, p. 208).

While contemporary descriptive and documentaryFootnote 2 linguists working in Africa and beyond may have developed more enlightened attitudes and nuanced understandings of language, in practice research enterprises may be closer to the early Eurocentric work than many would like to admit, particularly with regard to multilingualism. Dobrin and Berson (2011, p. 188) purport that “the intellectual resources documentary linguists have relied upon in conceptualizing what they are trying to do have been unfortunately limited (at times amounting to little more than their own culture-bound intuitions) and disconnected from the substantial literatures that exist on language as a sociocultural phenomenon”. For example, even where the existence of multilingualism is recognized, it is generally described, implicitly or explicitly, according to a model of ‘stacked monolingualism’ (Lüpke, Reference Lüpke2016b, p. 38) more suited to the European context. Multilingual (i.e., describing more than one language) dictionaries and grammars, even while ostensibly foregrounding the multilingualism in a particular region or society, perform a similar action, ascribing this word to one language, that word to another. They also reflect the ideological position that multilingual societies consist of “logically discrete communities of fully fluent (even monolingual) speakers” (Dobrin & Berson, Reference Dobrin, Berson, Austin and Sallabank2011, p. 191) where languages are fixed and separable entities, rather than recognizing that in multilingual societies languages are spoken by multilingual people, often in multilingual discourse, and that both significant overlap and considerable variation are observed, resulting in discourse that often defies categorical labels. It is also common for projects to retain a focus on the “ancestral code in isolation from other languages in the setting” (Woodbury, Reference Woodbury, Austin and Sallabank2011, p. 177). The notion of the ANCESTRAL CODE,Footnote 3 pervasive in the language endangerment rhetoric driving many documentation enterprises, means that the choice of which data to collect is often skewed to represent the target language, or a ‘pure’ version of it, rather than language use as it occurs (Childs, Good, & Mitchell, Reference Childs, Good and Mitchell2014, p. 171; Dobrin & Berson, Reference Dobrin, Berson, Austin and Sallabank2011, p. 193). It is recognized that “approaches privileging one ‘language’ as ancestral are problematic, and potentially even pernicious, in highly multilingual and fluid linguistic contexts where language use is organized around multilingual repertoires rather than ‘native languages’” (Childs et al., Reference Childs, Good and Mitchell2014, p. 169; Lüpke, Reference Lüpke and Wolff2017b). Nevertheless, Goodchild (2016, p. 76) describes how, despite explicit calls for the development of new research paradigms for multilingualism, “language documentation has, until recently, continued in the same isolationist vein”. Moreover, documentation is still frequently accompanied by descriptive endeavours such as grammars and dictionaries, that involve the same practices of artefactualization and erasure of variation as ever.

It is clear that any treatment of language in a multilingual setting must include information on variation. However, this presents complex methodological challenges. As has been shown by research in the third wave of variationist sociolinguistics, variation cannot be characterized by a list of alternating features predicted according to fixed social categories such as age, gender, or social class – it is multidimensional and deeply contextualized (Bucholtz & Hall, Reference Bucholtz and Hall2005, Reference Bucholtz, Hall, Llamas and Watt2010; Eckert, Reference Eckert2012; Irvine, Reference Irvine and Duranti2001). While it may be indexed to social categories, it manifests in natural language in a more nuanced way, sensitive to context, perspective, and scale. Eckert (2012, pp. 97–98) characterizes speakers:

not as passive and stable carriers of dialect, but as stylistic agents, tailoring linguistic styles in ongoing and lifelong projects of self-construction and differentiation. It has become clear that patterns of variation do not simply unfold from the speaker’s structural position in a system of production, but are part of the active—stylistic— production of social differentiation.

Speakers are constantly making situated linguistic choices based on sociolinguistic considerations such as the relative status and linguistic repertoire of their interlocutors, their own linguistic abilities and attitudes, and the context, location, and communicative goals of the interaction. It is essential to ask questions such as: Who is the person speaking to? What are the communicative goals? Where and when is the interaction taking place? What do the speakers know, or assume they know, about their interlocutors’ linguistic repertoire, background, and attitudes? These questions are even more pertinent and complex in richly multilingual contexts such as Casamance. Irvine and Gal’s (2000, p. 38) explanation of fractal recursivity and the projection of opposition holds true for language as for social groups. Perceived oppositions between languages do not define “fixed or stable [entities] … Rather, they provide actors with the discursive or cultural resources to claim and thus attempt to create shifting ‘communities’, identities, selves and roles, at different levels of contrast, within a cultural field.”

These facts have led scholars to seek a way to “overcome essentialist and artefactualized views of language” (Juffermans, Reference Juffermans2015, pp. 206–207) and in particular to “move away from descriptions of language and identity along conventional statist correlations among nation, language and ethnicity” (Otsuji & Pennycook, Reference Otsuji and Pennycook2010, p. 241). The notion of languages as entities is rejected, and multilingual language use treated as a dynamic practice. There are numerous studies of multilingualism that “shift away from conceiving language as an adequate base category towards a focus on feature, styles, or resources in order to explicate … bi/multilingualism” (Otsuji & Pennycook, Reference Otsuji and Pennycook2010, p. 243).Footnote 4 Blommaert and Backus (2013, p. 6) summarize the discussion as “(a) an increasing problematization of the notion of ‘language’ in its traditional sense – shared, bounded, characterized by deep stable structures; (b) an increasing focus on ‘language’ as an emergent dynamic pattern of practices in which semiotic resources are being used in a particular way – often captured by terms such as ‘languaging’, ‘polylingualism’ and so forth”. Although the focus of most third wave sociolinguistic studies has been Western settings, such conclusions have also been reached in work carried out in Casamance (e.g., Dreyfus & Juillard, Reference Dreyfus and Juillard2005; Goodchild, Reference Goodchild, Lu and Ritchie2016, Reference Goodchild2019; Goodchild & Weidl, Reference Goodchild, Weidl, Sherris and Adami2019; Juillard, Reference Juillard1990, Reference Juillard2005; Weidl, Reference Weidl2019). However, fine-grained variationist studies focusing on individual features are confounded by the fact that this setting involves so many unstandardized and often undescribed languages – how can we identify variation if we have no baseline to compare it to?

It is clear that monolingual linguistic descriptions cannot accurately reflect how language is used and experienced by speakers in multilingual settings. However, it is not entirely true that a view of languages as discrete entities “cannot be upheld on the basis of linguistic criteria” (Jørgensen, Karrebæk, Madsen, & Møller, Reference Jørgensen, Karrebæk, Madsen and Møller2011, p. 23). Whilst rejecting the notion of language as the basic level of analysis, they state that “we can not and should not either discard the level of ‘languages’ as irrelevant” (p. 25). As they remark, examples of highly multilingual discourse “could mislead to the idea that speakers do whatever comes to their minds without any inhibitions [whereas in fact] even the young, creative speakers with access to a wide range of resources will carefully observe and monitor norms and uphold them with each other” (p. 25). In Casamance, too, speakers distinguish between varieties which they consider to be distinct languages and use their repertoires not randomly but judiciously. Joseph (2002, p. 39) states that the “[t]he thought process by which [reification of languages] happens is a natural one. It does not necessarily lead us into error, so long as it leaves us with multiple ways of conceiving of language, and does not direct us to one of these conceptions to the exclusion of the others.” As analysts, we should try to recognize the different ways in which reification can manifest, subject to multiple perspectives, including our own. The solution is to find a way to conceptualize language and language use that can encompass the variation and creativity of multilingual language use, as well as the conservative nature of language ideology and the reality of language maintenance. In fact, fixity and fluidity need not be dichotomous, but understood as “symbiotically (re)constituting each other” ((Otsuji & Pennycook, Reference Otsuji and Pennycook2010, p. 244).

In the following I introduce the multilingual situation in Casamance, where the Crossroads research project is based, and show that aspects of the multilingual ecology here – i.e., the ostensible contradiction between diverse multilingual practice on the one hand, and conservativeFootnote 5 language attitudes and ideologies on the other – can be seen as directly analogous to the different perspectives discussed above, further motivating the proposed framework.

2. Multilingualism in Casamance

Multilingualism of the type observed in Casamance has been described by Lüpke (Reference Lüpke2016b, p. 36) as follows:

communicative practices in heteroglossic societies in which multilingual interaction is not governed by domain specialization and hierarchical relationships of the different named languages and lects used in them, but by deeply rooted social practices within a meaningful geographic setting.

Although widespread in societies across the world, this type of linguistic practice is under-researched. Prominent and influential studies of multilingualism have generally concentrated on Western contexts, where the (usually) two languages spoken in a multilingual society are assigned to different domains, such as official vs. unofficial, and exist in an asymmetrical prestige relationship. In Casamance, such a situation obtains only in the case of French, which is the official language of education and administration (although in practice this is not strictly adhered to). Elsewhere, the many minority languages and languages of wider communication exist in a relationship of equal status, with choice of language(s) dependent on the unique context of each interaction and its participants. There is no perception that any language is inherently more prestigious than another (although there do exist regionally based patterns of dominance relations between languages, in terms of their prevalence in people’s repertoires and their visibility in the linguistic landscape).

While some express surprise that so many small languages should remain vital, without coalescing or being abandoned in favour of a language of wider communication (Trudgill, Reference Trudgill2011), in fact it is exactly the small-scale, egalitarian nature of the multilingualism that allows it to flourish within a regional ecology of “longstanding and contemporary practices which contribute to maintaining, and even creating, linguistic diversity” (Vaughan, Reference Vaughan2018, p. 121). Such complementary factors include the maintenance of ideological links between language and place at the village level, adherence to social conventions based on the notions of landlords and strangers (Brooks, Reference Brooks1993), and resilience strategies necessitated by the region’s geographical, ecological, and historical situation (Lüpke, Reference Lüpke, Knörr and Trajano Filho2017c, following Kopytoff, Reference Kopytoff and Kopytoff1989). Maintenance of linguistic difference for similar motivations has been observed in other small-scale multilingual societies, including those in Amazonia (Epps, Reference Epps2018) Australia (Vaughan, Reference Vaughan2018), Cameroon (Di Carlo, Reference Di Carlo2011; Good & Di Carlo, Reference Good and Di Carlo2014), Papua New Guinea (Thurston, Reference Thurston1987, Reference Thurston and Dutton1992), and Vanuatu (François, Reference François2012).

Low visibility of this type of multilingualism is compounded by the fact that linguistic work in such rural African settings, even when multilingualism is acknowledged, still focuses on single languages, rather than taking repertoires as the starting point (Childs et al., Reference Childs, Good and Mitchell2014, p. 169). While there are certainly ideological factors that drive this bias (e.g., the fact that most researchers hail from the global North and are unfamiliar with such situations), from a purely practical point of view the complexity of studying multilingualism of this type can make it a daunting prospect. The difficulty stems not only from the number of languages involved, but also from the fact that many if not most of the languages involved are unstandardized and un- or under-described. Happily, it is gaining increasing attention in the work of researchers such as Klaus Beyer and Henning Schreiber working in Burkina Faso (e.g., Beyer, Reference Beyer2010; Beyer & Schreiber, Reference Beyer, Schreiber, Léglise and Chamoreau2013), members of the KPAAM-CAM project in Cameroon (e.g., Di Carlo, Reference Di Carlo2011, Reference Di Carlo and Seyfeddinipur2016; Good & Di Carlo, Reference Good and Di Carlo2014), and of the Crossroads project in southern Senegal (e.g., Cobbinah, Hantgan, Lüpke, & Watson, Reference Cobbinah, Hantgan, Lüpke and Watson2016; Goodchild, Reference Goodchild2019; Krajcik, Reference Krajcik2019; Weidl, Reference Weidl2019 ; and see <www.soascrossroads.org>), which is where the research informing this paper is situated. In the following, I briefly present the multilingual setting that provides the basis for the proposed framework.

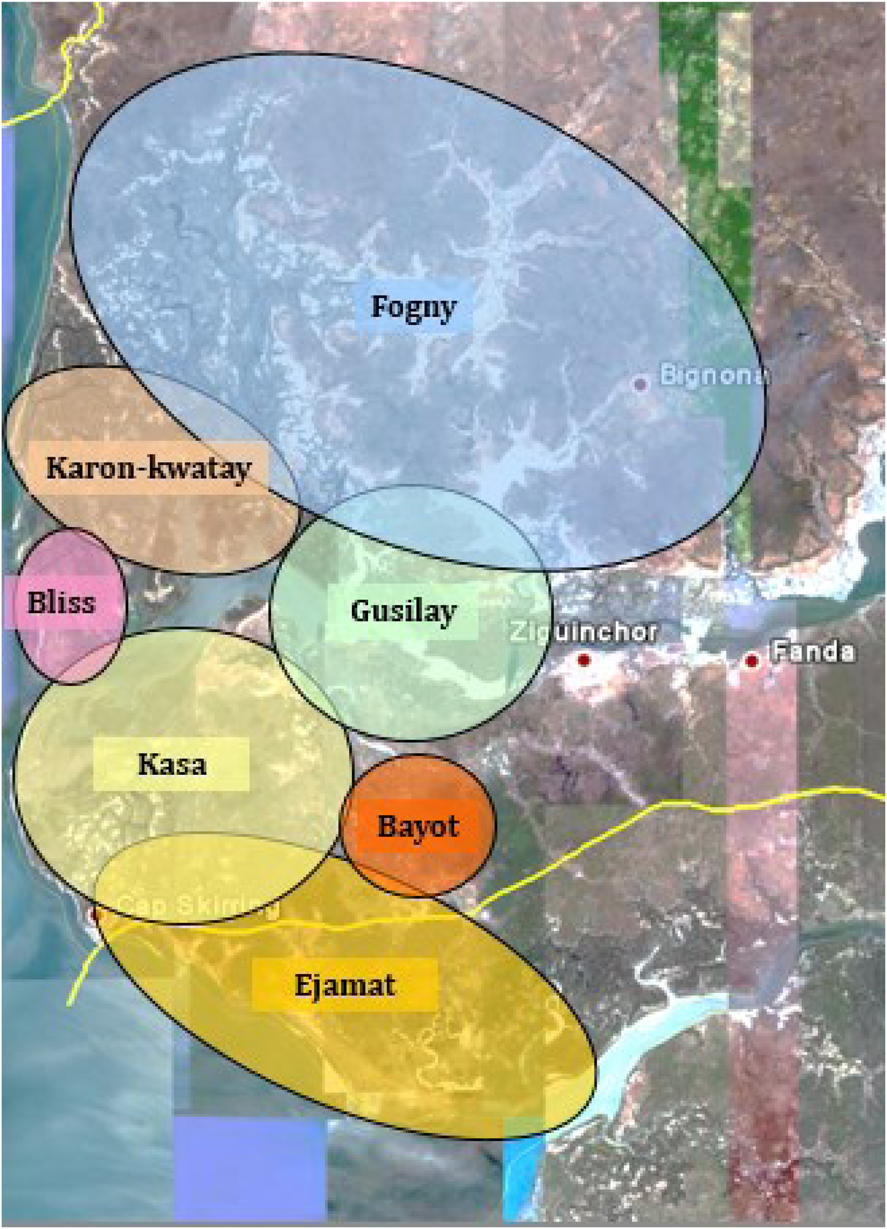

In Casamance, many indigenous ‘named’ languages are associated with a certain locality, either a village or polity. The association between language and place is one of patrimonial deixis, and indexes “the nominal or identity language of the founding clan or claims of particular groups to autochthony or land ownership” (Lüpke, Reference Lüpke, Knörr and Trajano Filho2017c, p. 7). The villages can be understood as the “ideological home bases” of the languages (p. 9), and also constitute geographical loci insofar as the greatest concentration of speakers of these small languages (and the greatest incidence of them being spoken) can be found there. These languages may be spoken as an identity language by (some) members of the population of these localities, e.g., those with strong family connections, or who trace their lineage back to the founding father of their village, although there are no restrictions on ‘outsiders’ learning and using the language. These languages are thus typically the focus of ancestral code type documentation and description projects. However, focusing solely on ideological constructs of patrimonial language erases large portions of the multilingual populations of these communities (Lüpke, Reference Lüpke2016a), as well as inherently positing some ‘pure’ variety which may well not exist (Dobrin & Berson, Reference Dobrin, Berson, Austin and Sallabank2011). These languages, such as they are, will be referred to here as PATRIMONIAL LANGUAGE OF X, where X is a geographical locus (village or polity). Named languages falling into this category include those from the Joola, Baïnounk, Bayot, and Balant groups of the Atlantic family. Figure 1 shows the approximate geographical distribution of some named Joola languages, created by Guillaume Segerer (Reference Segerer2009). This map was created to present the results of a classification enterprise and does not recognize some smaller named Joola languages that are often subsumed under these broader labels. For example, Kujireray and Banjal, the languages discussed in Sections 5 and 6 below, would both be contained in Gusilay under this analysis. Nevertheless, the map effectively illustrates the link between location and language in Casamance, as well as the differential reach of the Joola languages.

Fig. 1. Geographical distribution of some named Joola languages (Segerer, Reference Segerer2009).

In addition, there are several highly visible languages that do not have an ideological home base in Casamance in the strict sense described above, i.e.. a one-to-one relation between place and language based on a function of patrimonial deixis. These include Wolof, French, Mandinka, and Kriolu, These languages have different degrees of reach in Casamance, both geographically and sociolinguistically, with differing prevalence determined by multiple, intersecting factors. Geographically, for example, Mandinka is less prevalent in the Lower Casamance region to the west of Ziguinchor (where the Crossroads area is located). This is the one part of Casamance that is predominantly Catholic, whereas Mandinka is strongly associated with Islam, whose adherents make up the majority of Senegal’s population. Wolof is extremely widespread in people’s repertoires as the de facto national language of Senegal; however, its usage can be determined by language attitudes. Some people are rather disdainful of Wolof, as the language of the Nordistes ‘northerners’, and avoid speaking it when possible (Juillard, Reference Juillard2005, p. 33), whereas for others, particularly younger people, it is favoured as the language of sophisticated urban identity (p. 68). Knowledge and usage of French is largely determined as a result of exposure to it through education or other formal channels. For Kriolu, a divide can be seen on generational lines – this was the language of wider communication in the region before the proliferation of Wolof from the north.Footnote 6 Note that the lack of association with a particular geographical locus does not imply that these languages are not deeply ingrained in the linguistic landscape of Casamance. They have been present in the region for generations and may also play roles in the identity of certain populations and individuals and well as serving as languages of wider communication.

Table 1 shows a selection of named languages of Casamance along with their genetic affiliation and their sociolinguistic significance. Of course, the information in the table is rather generalized, and does not represent the different roles that a given language can play in different speakers’ repertoires – see Section 6 below for discussion.

table 1. Some named languages spoken in Casamance

In the following I show that, while the notion of languages as discrete entities can certainly be applied at the ideological level, at the same time, high levels of non-polyglossic multilingualism (i.e., where language choice is not categorically determined by the domain of use, but rather through uniquely situated social relations between speakers) result in varied and individual repertoires and interactions that can only be effectively analysed with recourse to a repertoire approach that gives significant weight to sociolinguistic factors.

2.1. language maintenance and ideologies

While language use in Casamance is often highly multilingual and characterized by variation, it is clear that the concept of language boundaries is valid in the minds of speakers; indeed, this is a necessary condition for language maintenance. The ideological association of language with place (and thus patrimonial heritage and identity) in a society of small village-based populations motivates the existence of a large number of languages. Their ongoing maintenance (as opposed to coalescence or abandonment to a lingua franca) can be attributed to factors to do with relational identity and group membership. Languages can be used to index affiliation with a certain group, and thus difference from other groups (Irvine & Gal, Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000). Both Lüpke (Reference Lüpke2016a), for the Casamance, and Di Carlo (Reference Di Carlo and Seyfeddinipur2016), for the Lower Fungom, Cameroon, have stressed that this differentiation has practical importance. Group identity, sanctioned and strengthened by linguistic identities, is important for strategic purposes, whether for spiritual security (Di Carlo, Reference Di Carlo and Seyfeddinipur2016, p. 73), or for claiming land rights and forging strategic alliances against invasion and slave raids (Lüpke, Reference Lüpke2016a, p. 10).

While it is inaccurate to suggest that a village’s patrimonial language is the only language spoken by the residents of that village (or indeed that this is the only place where it is spoken), we can nonetheless observe in these areas a concentration of individuals by whom that language is spoken regularly, for a variety of different registers, topics, etc., and for some of whom it strongly indexes a social identity. These patterns of use reinforce norms – thus language use among such speakers in these geographical loci can be said to represent the closest thing to a ‘standard’ variety of that language. These are the speakers most able to assess the level to which other speakers control a language (i.e., adhere to the norms), and who may hold strong opinions on what constitutes ‘good’ or ‘bad’ language use. In traditional terminology these may be described as ‘native speakers’; however, this term cannot be straightforwardly applied in a setting where speakers are so mobile and have such fluid repertoires. Within the framework proposed in this paper, these are the speakers who are central in determining the prototype of the language, both through their use of it and through their ideological conception of it. Thus, we may more accurately refer to them as prototypical speakers.

2.2. multilingual repertoires and discourse

Despite conservative and purist ideologies surrounding patrimonial languages, the actual dynamics of multilingualism – at the individual, societal, and discourse levels – are extremely fluid. Each person, location, and set of circumstances has a unique and mutable linguistic profile, which results in considerable variation from artefactualized ideals of named languages. Wide-reaching social networks and high mobility are two factors contributing to high levels of multilingualism in the area (see Lüpke & Storch, Reference Lüpke and Storch2013, pp. 33ff). People are linguistically adaptable and pick up languages throughout their life as and when it becomes necessary to their circumstances. Very often, people make an effort to learn the languages of their hosts, friends, extended families – a tradition termed plurilinguisme de voisinage ‘neighbourhood multilingualism’ by Calvet and Dreyfus (Reference Calvet and Dreyfus1992, p. 43), and see also Goodchild (Reference Goodchild, Lu and Ritchie2016). A speaker’s repertoire may include several languages according to where they have friends and family, who they have lived and worked with, and where they have resided. Thus, linguistic repertoires are not only highly contingent and individual, but also frequently shifting, presenting “an ever-changing sociolinguistic setting” (Goodchild, Reference Goodchild, Lu and Ritchie2016, p. 78). Importantly, the individual nature of people’s repertoires means that notions of ‘proficiency’ and ‘standard’ language are more problematic than in the Western arena where they are traditionally applied (and indeed they are criticized there as well – cf. Blommaert & Backus, Reference Blommaert and Backus2013, p. 4). Despite their adaptability, people do not just acquire a full language wholesale. Each language in their repertoire does not play an equivalent role, or represent an equivalent level of ‘mastery’. For detailed accounts of the variety and individuality of linguistic repertoires see Goodchild (2019, pp. 140ff), Lüpke et al. (unpublished observations), and Weidl (Reference Weidl2019). These facts have consequences for linguistic description, if linguistic description is intended to be a realistic representation of language use. As discussed above, patrimonial languages in Casamance have ideologically determined geographical loci, at which can be found a concentration of frequent and conservative speakers, and a higher incidence of that language being spoken; it seems reasonable to begin any descriptive enterprise in this place.Footnote 7 However, even here, extensive variation is observed, and it is crucial that this description occurs within a framework that allows us to fully represent this.

Even if languages are successfully described, multilingual discourse presents further challenges to the researcher. There is a complex interplay between speakers’ multilingual repertoires and how they deploy their linguistic resources in multilingual discourse – as discussed above each interaction is deeply contextualized, rendering generalizations over the use of one language or another difficult. Nevertheless, three main types of multilingual language practice can be identified for the sake of discussion; receptive multilingualism, alignment, and mixing. This typology is useful as it does not assign roles to particular languages, but instead refers to the manner in which speakers make use of their repertoires in situated interactions, and invites discussion of motivating and facilitating factors for the different practices. It is important to note that a single interaction may include features of all three, with speakers frequently and effortlessly navigating the vagaries of social interactions.

In receptive multilingualism the speakers speak to each other in different languages (cf. Jan & Zeevaert, Reference Jan and Zeevaert2007; Singer, Reference Singer2018). In most cases a speaker uses the language that plays the most prominent role in their repertoire whilst having no ostensible problem understanding their interlocutors who do the same, even when there are more significant differences between languages. This type of multilingual discourse is observed when speakers know each other well and enjoy equal social standing, and there is no compulsion to alter one’s linguistic behaviour to either accommodate or intimidate another party – see Section 6 below. The term ALIGNMENT refers to the process in which certain participants alter their linguistic behaviour to bring it into line with that of another participant or participants.Footnote 8 In a conversation where the participants have different multilingual repertoires, they may reach a consensus on a single language as the principal means of communication, based on the sociolinguistic make-up of the group and the relationships between the speakers. This can be motivated simply by necessity; if one speaker does not understand, or is assumed not to understand, all the languages in play then it is necessary to align with that speaker’s repertoire as the lowest common denominator. However, it is also observed even when speakers’ repertoires overlap, and can indicate asymmetric social relations between speakers, either deferring to the preferred language of one person, or using your addressee’s own preferred language to demonstrate your superiority.

Mixing is understood here as a practice where speakers use features from a number of languages in a fluid manner. This can be at the level of the sentence, in the more traditional sense of code-switching (Myers-Scotton, Reference Myers-Scotton and Wei2003, Reference Myers-Scotton and Coulmas2017), but can also involve mixing within the word, such as a noun class prefix associated with one language affixed to a lexical root from another (cf. Auer, Reference Auer1999), resulting in hybrid forms which are difficult to label. Mixing can be motivated by different factors; first, in the case that there is not a large overlap (real or perceived) in the speakers’ repertoires, so they can engage in neither receptive multilingualism or alignment. They may be less familiar with each other and more uncertain in their relationships. In these cases they engage in a process of BRICOLAGE using their linguistic adaptability and knowledge in using features from various languages to communicate and perform social functions. In the opposite case, where speakers are very familiar with each other, and there is an overlap in their linguistic repertories, they may engage in mixing in a playful way, to display their linguistic virtuosity and index different aspects of their relationship in a given context. Indeed, these two motivating factors are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

Multilingual discourse, its mechanisms and motivations are clearly highly complex. For the purposes of this paper, the key point is that speakers can use individual features of a given language to index social meaning associated with that language, in a fluid and situated fashion. This is of course only made possible by the fact that, even despite shared material and variation, each language can be characterized by features that are perceived by speakers as prototypical. In the following I explain the notion of prototypicality and the structure of categories as theorized by Eleanor Rosch and her colleagues, and discuss how it can be applied to the description of languages.

3. Prototype theory and language as a category

It is the hypothesis of this paper that languages can be conceptualized as categories, structured according to principles laid out by Rosch and her colleagues in their work on prototype theory (Rosch, Reference Rosch1973, Reference Rosch1975a; Rosch & Mervis, Reference Rosch and Mervis1975; Rosch et al., Reference Rosch, Mervis, Gray, Johnson and Boyes-Braem1976). This approach can account for many of the ostensible conflicts observed in multilingual settings and related research paradigms as discussed above (see also Cobbinah et al., Reference Cobbinah, Hantgan, Lüpke and Watson2016, and Lüpke, Reference Lüpke and Wolff2017b, for earlier formulations of the hypothesis put forward in this paper). This is not the first time that aspects of prototype theory have been applied to language. Notable examples include Lakoff (Reference Lakoff1987), who invokes fuzzy edges and radial categories to motivate the membership of seemingly arbitrary categorization processes in language, and Langacker (Reference Langacker1991, p. 59), who cites prototypes in calling for an alternative to the classical model of categorization to better account for the nuances of semantic and syntactic behaviour observed over traditionally defined word classes and grammatical categories (see also Joseph, Reference Joseph, Trappes-Lomax and Ferguson2002). It has also been applied to the structure of noun classification systems in languages of Casamance itself, first by Sagna (Reference Sagna2008), then Cobbinah (Reference Cobbinah2013), and Watson (Reference Watson2015). The approach proposed here builds on observations made in these works and expands the principles to create a framework for the description of languages and the analysis of multilingual discourse.

The principles of prototype theory that are relevant to the proposed conceptualization of language are the following:

1. The structure of categories is empirically determined.

2. Membership of a category is gradable, not binary.

3. Goodness of fit in a category is judged according to attributes possessed, in combination with sociocultural knowledge and personal experience.

4. Categories are relative and their structure can be understood in relation to each other.Footnote 9

In the remainder of the section I briefly introduce these concepts and discuss their application to the description of language(s).

3.1. empirically determined categories

It is widely agreed that categorization is a fundamental cognitive function and that “humans (and arguably other organisms) are seen as living in a conceptually categorized world” (Rosch, Reference Rosch, Bělohlávek and Klir2011, p. 91). Indeed, it is this cognitive faculty that, in large part, compels us to name and label languages, even when clear boundaries do not objectively exist. However, the cognitive process of categorization has not always been well understood. Prototype theory was developed in order to explain the mental representation of categories and offer an alternative to the classical theory of categorization which is inadequate to explain how we categorize entities in the world.

In the classical view of categorization, membership in a given category was determined on the basis of a list of features, known as necessary and sufficient conditions, which an item must possess in order to be included. Apart from insufficient flexibility – see Section 3.2 – this way of characterizing categories was unsatisfactory because it attempted to impose, through post-hoc introspection, objective form and order on categories that originate in human cognition. Prototype theory proposes that since categories are cognitively based their structure can only be modelled on the basis of empirical data in the form of the judgements and intuitions of people in whose cognition those categories reside (Rosch, Reference Rosch1973, Reference Rosch1975a; Rosch & Mervis, Reference Rosch and Mervis1975).

Prescriptive ideologies and artefactualizing descriptive practices have a similar effect to the classical view of categorization. They purport that a language can be comprehensively defined by a set of rules, and prioritize notions of ‘correct’ or ‘pure’ language, backgrounding or even erasing the facts of actual language use. A more robust and reliable description of a language must be based fully, and without a priori assumptions, on the judgements and intuitions of language users.

3.2. gradable membership of categories

The classical view presented category membership as fixed and binary – an entity is either in a category or out of it, subject to its possession of necessary and sufficient conditions. While this view reflects our propensity to categorize, it does not stand up to empirical examination for many commonly encountered categories; the diverse nature of the world means it is always possible to find counter-examples.Footnote 10 For example, for the natural semantic category BIRD, a postulated list of necessary and sufficient conditions might include having wings, being able to fly, laying eggs, and so on. However, it is easy to think of at least one counter-example for every condition in the list. For example, the condition of having wings may be violated by an injured bird, or the ability to fly by an ostrich or kiwi. Conversely, laying eggs is not exclusive to birds – many other classes of creature do so too. Rosch and her colleagues showed experimentally that the cognitive representation of semantic categories is not binary, but rather made up of many diverse entities that are more or less good – or prototypical – examples of the category (see Rosch, Reference Rosch, Bělohlávek and Klir2011, for an overview). For example, for the category BIRD, a sparrow or pigeon is more prototypical than an ostrich or penguin, but they are all birds.

Again, the classical view is analogous to artefactualizing descriptive practices on the part of linguistic researchers, as well as prescriptive ideologies on the part of speakers. Certain linguistic items are classified as being ‘correct’ or ‘standard’, automatically devalidating any instance of language use that does not conform to these conventions. Prototype theory, by contrast, allows for the flexibility and variation observed in (multilingual) language use, without having to reject the notion of languages as entities (albeit not stable and fixed ones). Just as for semantic categories, membership is gradable; speakers are able to identify sounds, words, and sentences as better or worse examples of a language. The case of loan words illustrates this well. There is often a lack of consensus as to what extent a loan word has ‘become’ part of the language that borrowed it. Are forms like deja-vous or loch still French and Gaelic, or have they become English? The prototype approach renders this discussion moot. The prototypicality of a form as an example of English is determined empirically on the judgement of speakers, and differing opinions are unproblematic. It might reasonably be hypothesized that such words as deja-vous or loch would occupy similar positions in the representation as the penguin or ostrich; they can be included in the category ENGLISH but are not optimal examples of it.

3.3. factors contributing to prototypicality judgements

The prototypicality of entities in categories is empirically determined on the basis of the judgements of a large number of participants, and these judgements are affected by factors such as the attributes possessed by an entity, socio-cultural representations of the category, and individual life experiences (Rosch, Reference Rosch1973, Reference Rosch1975a; Reference Rosch, Brislin, Bochner and Lonner1975b; Rosch & Mervis, Reference Rosch and Mervis1975). For example, if we look at prototypical examples of the category BIRD, we find that they have several attributes in common, such as having feathers, wings, and a beak, laying eggs, flying, etc.; indeed, so do many of the less prototypical members. Therefore, we can claim that these attribute form part of the prototype of the category BIRD, without having to posit their position as necessary or sufficient. Conversely, an attribute such as the ability to swim rapidly underwater belongs only to a subset of non-prototypical members of the category, such as the penguin and cormorant. Since this feature is rare among the membership, we can surmise that swimming is not a prototypical attribute of this category.

In language, too, some features can be characterized as frequent and stable – a.k.a. prototypical – across many examples of the language, while others are rarer and more marginal. For example, we might reasonably hypothesis that segments such as word-initial [t] or [s] are prototypical features of English as they are common and relatively stable across speakers. On the other hand, a segment such as [x] (as in some speakers’ pronunciation of loch) could be considered less prototypical (at least by a speaker of STANDARD ENGLISH). The same principles of prototypicality can be applied to prosodic, lexical, and grammatical elements.

Rosch (Reference Rosch1975a) found that there is significant consensus (from people of the same cultural background) on the central core of a category model, due to the socio-cultural aspect of category construction. At the same time, each individual has a personal life experience which also shapes their internal representation of categories. For example, a person who had a parrot as a pet may consider it a more prototypical bird than the next person. These findings are directly analogous to the way speakers reify languages, collectively and individually. There tends to be a broad consensus on which forms and features are prototypical of a language, with areas of variation dependent on each individual’s repertoire and biography. For example, any speaker of English would consider a form like [tɪ] (for tea – small phonetic differences notwithstanding) to be very prototypical – it is a highly frequent form and does not contain any variable or controversial features. On the other hand, a form such as [lox] (for loch) is less clear-cut. For some speakers, there is a clear intuition that it is an unusual example. For others, say a Scotsman who lives near a lake, it would be more ordinary, and thus prototypical.

3.4. relationships between categories

Prototype theory also invokes the notion of SALIENCE in relation to the features associated with a category.Footnote 11 The salience of a feature refers to how good a predictor of a category it is and inherently takes into account the existence of other categories, and different levels of scale. For example, features such as having wings or laying eggs are fairly good predictors of the category BIRD, because they are not frequently found in other semantic categories at the same taxonomic level, such as MAMMAL. Something like having a head is not a good predictor (at this taxonomic level) because it is common across many categories. If, however, we compare the higher-level categories of ANIMAL and FURNITURE, possession of a head becomes a more salient feature in distinguishing the two categories (Rosch, Reference Rosch, Margolis and Laurence1999; Rosch & Mervis, Reference Rosch and Mervis1975). The notion of salience presupposes that categories do not exist in isolation but in a structured relation with other categories. Indeed, fundamental to the very existence of categories is the notion of opposition, judging not just similarity between a group of entities, but distinguishing that group from other entities on the basis of perceived differences. Furthermore, the relative nature of categories also means that salience is not an absolute value – it can change with context and perspective (Rosch, Reference Rosch, Bělohlávek and Klir2011, p. 105). For example the feature [lays eggs] has high salience for the category BIRD when juxtaposed with the category MAMMAL, but lower salience when compared with the category FISH.

These principles apply also to language. Take the example of loch and the alternation in different varieties of English between [x] and [k] in word-final position. In isolation, neither pronunciation is remarkable – for their respective prototypical speakers they are both quite ordinary. It is only when they are juxtaposed that they become a salient point of difference between the two varieties. Salience of linguistic features is also subject to effects of different perspectives. The word-final [x] is a salient point of difference between Scottish and Standard English, but not between, say, Scottish English and German, in both of which it is a frequent feature.

Features that mark a difference between languages can potentially be exploited by speakers to index aspects of identity associated with a given variety; some may even become conventionalized, well-recognized linguistic symbols of that identity. This special salience of linguistic features has been termed ‘emblematicity’ (Silverstein, Reference Silverstein2003) or ‘iconicity’ (Irvine & Gal, Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000). The importance of emblematic features is invoked in the sociolinguistic literature discussing the strategies used by speakers to index facets of identity associated with different varieties (see, e.g., Blommaert, Reference Blommaert2013; Bucholtz, Reference Bucholtz, Djenar, Mahboob and Cruickshank2015; Eckert, Reference Eckert2012). It has also been recognized in research in small-scale multilingual communities including Casamance (Goodchild, Reference Goodchild2019; Hantgan, Reference Hantgan2017; Lüpke et al., unpublished observations; Weidl, Reference Weidl2019), as well as Cameroon (Di Carlo, Reference Di Carlo2011, Reference Di Carlo and Seyfeddinipur2016), Papua New Guinea (Thurston, Reference Thurston1987, Reference Thurston and Dutton1992), and Vanuatu (François, Reference François2012).

4. implications for methodology

The use of features, rather than entire codes, as the basic level of analysis has been employed to good effect in studies of multilingual discourse (e.g., Blommaert & Rampton, Reference Blommaert and Rampton2012; Jørgensen et al., Reference Jørgensen, Karrebæk, Madsen and Møller2011; Otsuji & Pennycook, Reference Otsuji and Pennycook2010, p. 243; Mufwene, Reference Mufwene2001, Reference Mufwene2017). However, for many sociolinguistic researchers, even if they eschew the notion of discrete languages in the discourse, there is a wealth of information at their disposal which can be used to assess which ‘language’ (as a socio-cultural construct) a given feature is conventionally associated with. Such information is not available for settings such as Casamance where the languages are under-described; in these cases the prototypical features of the languages must be empirically assessed, before these descriptions can be used in the analysis of multilingual discourse. The prototype description methodology achieves its greater adequacy through dependence on a large quantity of rich and varied data, from a large number of speakers and contexts – the only restriction is that it is the speaker’s ascertainable pragmatic intention to speak the language in question. This data provides us with two types of valuable information about the language; where there is consensus, and where there is variation. If there is consensus across a wide and varied number of speakers in many different contexts, we can be confident in claiming a feature as prototypical. If a feature exhibits a high level of variation we can examine possible reasons for that through correlation with sociolinguistic data.

A range of different data types allows us to examine the degree and manner of variation from prescribed norms that is tolerated. Broadly speaking, we can identify three main genres commonly collected during linguistic description: elicitation, staged communicative events, and observed communicative events (cf. Gippert, Himmelmann, & Mosel, Reference Gippert, Himmelmann and Mosel2006; Lüpke, Reference Lüpke2010b). All three genres produce different types of data, which should be considered not as contradictory but complementary. Elicitation may be criticized as producing ‘artificial’ data, as consultants may be inclined to produce ‘correct’ forms, that are less likely to occur in natural speech. From the prototype theory perspective this is unproblematic since speakers’ judgements of what is ‘correct’ or not for language X are an important part of the structure of the language category. Elicitation is thus a fast and efficient way to build a preliminary picture of the prototypical members and features of the language, provided the data collection is carried out with numerous speakers. The differences between the different types of data collection can also be instructive in examining perceptions of ‘correctness’ versus spontaneous production. Staged communicative events produce language data that are more spontaneous than those from elicitation, but in contexts that are still artificial, i.e., that would not exist outside the research context. Examples include experimental tasks, monologues or narratives performed for the purpose of the research, and demonstrations of special tools or techniques – this is a genre particularly prevalent in documentation projects. This type of data has the advantage of being more naturally produced than elicitation data, so can give us more information about variation in the language and the structure of natural speech. At the same time, the method is still relatively controlled; the researcher can impose a specific language, or a particular topic, in order to investigate areas of particular interest. Observed communicative events are those where the language data is as close as possible to naturally occurring speech. Usually this would imply conversation, but can also include more formulaic genres such as ceremonial language or songs, provided these are recorded in their natural context and not performed especially for the purposes of linguistic research. Care must be taken when including data from conversations in this corpus, as it may not always be possible to ascertain what language speakers are intending to produce. Naturalistic multilingual discourse is the subject of analysis once the prototypes have been established (although the approach is iterative, with findings from the discourse feeding back in to the prototype model).

The type of data that is indispensable to an understanding of both individual languages and multilingual language use, but that is conspicuous by its absence in most linguistic documentation and description work (Goodchild, Reference Goodchild, Lu and Ritchie2016, p. 77), is rich sociolinguistic information about the biographies, linguistic repertories, and language attitudes of speakers and the context of the language use. The understanding of the lexico-grammatical codes themselves, and the variation observed therein, is dependent on detailed information on the speakers and the settings where those codes are constructed. To give a simple example, an utterance taken from a piece of multilingual discourse may be ambiguous between two or more Joola languages – see Section 6 below. However, if we have additional data on the speakers’ repertoires and the context in which they are speaking, we may more confidently assert which language is being spoken.

This data forms a corpus, made searchable through transcription and translation, which can be mined to build a model of a language, using a specific analytical methodology informed by the principles of prototype theory. Essentially, the prototypical form of any given item (from phonetic segment to syntactic construction) can be found through examination and aggregation of numerous exemplars. Their relative frequency and stability can be assessed, and once comparable descriptions are established for other languages, they can be juxtaposed in order to investigate the relative salience of different features and variation motivated on the basis of the associated sociolinguistic data. This is illustrated in Section 5 below, and see Lüpke and Watson (unpublished observations) for a more detailed treatment. These findings can then be used to effectively analyse richly multilingual discourse, as illustrated in Section 6.

5. towards a prototype description of two Joola languages

In this section I operationalize the framework and methodology discussed in the previous two sections and show in a more concrete way how the notions of prototypicality and salience can be used in a meaningful way to describe languages. In principle, such an approach can be used to describe any language in any context. I focus here, however, on the particular challenges associated with settings such as Casamance, where languages are unstandardized, with little to no previous description or documentation of any kind, and where language boundaries may be particularly fluid due to the structural similarities between them. I will illustrate, using two Joola languages from Casamance – Kujireray and Banjal – how structural and sociolinguistic aspects of languages can be described using principles from prototype theory. Since this paper constitutes a proposal for a new framework, the methodology entailed by the framework has not yet been systematically tested. The treatment below is therefore exploratory and has been constructed in a somewhat opportunistic fashion, since I have existing knowledge of both languages.Footnote 12

Kujireray is the patrimonial language of the village of Brin; Banjal that of a polity of ten villages (each also with their own dialectal variations – Sagna, Reference Sagna2008, p. 78) located adjacent to Brin, referred to as Mof Ëvi ‘land of the king’, or simply ‘the kingdom’. By their speakers, these are considered separate Joola languages; they have their own names, and are associated with separate geographical loci. Structurally, too, speakers are able to identify many features that belong to one or the other language as part of their metalinguistic knowledge. However, there is also significant structural overlap between the two languages, which is unsurprising given their genetic and geographical relatedness. These similarities are also acknowledged by speakers. This tension between structural overlap and maintenance of significant differences provides a good opportunity for exploring the salience and emblematicity of different features. In the following, I describe how we can start to build models of these languages as categories, based on the frequency and stability of their features, followed by an assessment of their salience, when examined side by side. I will show that it is these juxtapositions that facilitate the emergence and maintenance of emblematic features, and also that emblematicity is subject to effects of scale and context.

Constructing a model detailing the prototypicality of all the features found in a language is clearly a long and complex task; I illustrate here using just a few phonetic segments, namely word-initial velar stops [k/g], word-final velar fricatives [h/x], and the coronal stop [t]. The velar segments have been observed to be rather volatile in Casamance languages (Cobbinah, Reference Cobbinah2013, p. 64; Hantgan, Reference Hantgan2017; Sagna, Reference Sagna2008, pp. 86ff; Watson, Reference Watson and Lüpkeforthcoming), and thus present a good opportunity to test the explanatory potential of a model specifically designed to handle variation. The [t] by contrast seems to be quite stable in the languages in question.

Starting with Kujireray, an examination of our extensive and varied data reveals that word-initial [k] is a very frequent feature. In the majority of instances, the third person plural subject agreement prefix is ku-, and the existence of two different noun class prefixes – ku- and ka- – both with large memberships, means that around 20% of nouns begin with this feature, as well as agreement targets co-occurring with them in utterances. Of particular prominence is the form kasuumay ‘peace’, which is an integral component of the formulaic greeting exchange, and thus present in every single exchange that occurs in Kujireray (and indeed in all Joola languages; see Lüpke et al., unpublished observations; Lüpke & Watson, unpublished observations, for a discussion of similarity and difference in Joola greetings). We also note variation. In a very few cases the voiced counterpart [g] is used where we may (according to the observed trend) expect to find a [k].

In word-final position, a greater degree of variation is observed between [x] and [h]. There are many lexical items that may be pronounced with a word-final [h] by some speakers, and word-final [x] by others. For example the word for ‘day’ is attested as both [funah] and [funax]. Word-initial [t] is identified as a segment that is not subject to variation, but is less frequent than other segments such as [t]. These findings are summarized in Table 2.

table 2. Segments in Kujireray

They can also be represented graphically as in Figure 2, where the segments are positioned along a frequency scale. The frequent [k] and the rare [g] are at opposite ends of the frequency axis. The less frequent [t], [x], and [h] are lower than [k], but higher than [g]. Where segments are observed to be subject to variation on the same sites, they are connected with a dotted line.

Fig. 2. Frequency and variation of segments in Kujireray.

As discussed in Section 3 above, categories are structured relative to other categories. To add a dimension of salience to our description of Kujireray it needs to be compared to another language – in this case, Banjal. First, we need to start building the model of Banjal. Using the same methodology, we can ascertain the following facts for the equivalent phonetic segments (see Table 3). These are illustrated graphically in Figure 3.

table 3. Segments in Banjal

Fig. 3. Frequency and variation of segments in Banjal.

We can now start to compare the languages to one another. Table 4 combines and juxtaposes the observations made in Table 2 and Table 3 concerning phonetic segments and their status in the two languages. Using this information we can now add a salience dimension to our graphical representations, resulting in feature matrices, as in Figure 4.

table 4. Segments in Banjal and Kujireray

Fig. 4. Feature matrices for segments in Kujireray and Banjal.

The matrices show that word-initial [k] is a frequent feature of Kujireray, while word-initial [g] is rare, and that the reverse is true for Banjal. Furthermore, we know from our corpora that these features prototypically contrast in cognate noun classes (ka/ku and ga/gu) and their agreement paradigms, including in the prototypical forms for ‘peace’ (kasuumay/gëssumay), which means that forms contrasting for this feature are extremely frequent in these languages. As a result, we can say these different word-initial velars plays a role in distinguishing Banjal from Kujireray (and vice versa), and are therefore not only frequent features but also salient ones. This is consistent with observed linguistic behaviour, where Kujireray (and other speakers) use the word-initial [g] to signify some sort of alignment with their Banjal-speaking interlocutors (Hantgan, Reference Hantgan2017). Discussion with speakers also indicates a high level of metalinguistic awareness of this. It is reasonable to suggest that this feature has taken on emblematic status and can be used by speakers to specifically index a sociolinguistic identity associated with that language. Note, however, that emblematicity is relative and subject to effects of scale. While [g] is emblematic of Banjal, the converse situation, i.e., that word-initial [k] is emblematic of Kujireray, does not necessarily hold, since this is a common feature in many Joola languages and other languages in Casamance. Therefore, while in a conversation with a Banjal speaker, a Kujireray speaker may use [k] to index Kujireray identity, in a conversation with a speaker of, say, Joola Kasa, in which word-initial [k] is also frequent, this option vanishes, as the segment ceases to be salient. See also Lüpke et al. (unpublished observations) and Lüpke and Watson (unpublished observations) for a presentation of scale effects in Joola greetings.

A different type of contrast is observed in the respective distributions of word-final [h] and [x]. In Kujireray, a relatively balanced variation between the two sounds is observed; neither is significantly more frequent (at the same site). In Banjal, speakers consistently produce [x], with some very rare instances of [h] at the same sites. This has a more subtle asymmetric effect with respect to the salience of these features. We cannot say that [x] is particularly salient to Banjal, as it also occurs in Kujireray. By contrast, the [h] is potentially a salient feature of Kujireray, since it does not occur in Banjal. However, the effect, and thus potential for emblematicity, is somewhat dampened by the variation, which means the contrast is not a consistent one. However, this does provide us with a promising avenue of investigation with respect to the source of the variation in Kujireray. For example, it seems plausible that the [x] variant in Kujireray is motivated through contact with Banjal (or indeed other languages) in which that segment is more frequent and less prone to variation, i.e., more prototypicial. We can investigate this hypothesis by examining the sociolinguistic background of the speakers who produce the respective segments, and the conversational contexts in which they appear. According to the proposed methodology, this is easy, as the description itself is based on a rich and varied set of data, all of which is linked to detailed sociolinguistic data. To interrogate this hypothesis, it would be a matter of pulling up all the examples from the Kujireray data where word-final [x] occurs. These can then be correlated with the speaker(s) and their repertoire(s), as well as the context in which they were uttered. If, for example, it transpired that the speakers producing [x] rather than [h] counted Joola Banjal prominently in their repertoire, this could be seen as support for the hypothesis.

Finally, in the case of word-initial [t], no contrast is observed between the two languages. It is common to both languages (as well as to many in the Casamance), in formally similar items such as pronouns and ideophones. These correspondences mean that, while frequent, word-initial [t] has low salience between these two languages. Its relative frequency and stability, however, means that any instances of variation would be strongly indicated for further investigation.

This approach to description is illustrated very simply here, but it can in principle be applied to build far more detailed models of languages as categories, incorporating not only segmental but also prosodic, lexical, semantic, and syntactic features. These models, being empirically determined, constitute robust descriptions of the languages in question and can be used a reference point for the analysis of multilingual discourse. Emblematic features of languages can be identified and situated with respect to other languages, and their use in context therefore meaningfully interpreted. However, it is clear that a language is considerably more complex than a basic semantic category. The possibility of modelling conceptual combinations, even of two-word combinations, is the topic of considerable debate (Rosch, Reference Rosch, Bělohlávek and Klir2011, pp. 109ff), and some researchers have concluded that “no model handles all the forms of combination that people can generate” (Murphy, Reference Murphy2002, p. 469). With respect to the application of the model proposed here, there are two particular challenges to overcome. First, the notion of frequency is difficult to capture, and can be defined according to different criteria (e.g., frequency in the inventory of possible words vs. the frequency with which they appear in discourse – and in the latter case, how can we ever account for every instance of a given language?). Second, the features that make up instances of language are many and multiplex, and interact, with each other and with the context. A detailed treatment of the nature of the features that determine category membership is a topic for future reflection and research, beyond the scope of this preliminary proposal.

Finally, it is important to note that this approach (or indeed any approach) will not result in a fully comprehensive model of a language, no matter how rigorously the methodology is applied. Rosch (Reference Rosch, Margolis and Laurence1999, p. 259) cautions against using the notion of prototype as a reification of a particular mental structure, i.e., a precise collection of features that make up the language, whereby:

[q]uestions are then asked in an either-or fashion about whether something is or is not the prototype or part of the prototype in exactly the same way in which the question would previously have been asked about the category boundary. Such thinking precisely violates the Wittgensteinian insight that we can judge how clear a case something is and deal with categories on the basis of clear cases in the total absence of information about boundaries.

Using the prototype approach in this way would in fact just be a roundabout way to arrive at the same artefactualizing endpoint that has been shown to be inadequate for the description of languages and the analysis of multilingual language data. In fact, “[t]o speak of a prototype at all is simply a convenient grammatical fiction; what is really referred to are judgements of degree of prototypicality” for each individual example of language use (Rosch, Reference Rosch, Margolis and Laurence1999, p. 263). That is to say, if a sufficient number of speakers count (through use and/or explicit judgment) a certain feature as belonging to a language, we can count that feature as prototypical of that language. Another point to be aware of is that the empirically determined prototype may differ sometimes from the ‘norm’ as an ideological construct (cf. Jørgensen et al., Reference Jørgensen, Karrebæk, Madsen and Møller2011, p. 33). A whole set of ideological factors are most certainly at play in the formation of prototypes as conceptualized by the speakerFootnote 13 – again motivating the necessity of several different types of data as well as maintenance of reflexivity at all levels of analysis. This is illustrated in Section 6 below, where I present and analyse examples of multilingual Joola discourse, bringing together all the concepts discussed thus far.

6. Prototype analysis of multilingual data

The data in this section consists of two extracts of discourse featuring multilingual speakers using different Joola languages (as well as French), described and analysed according to the concepts and principles discussed above. I show how discourse featuring closely related languages can be analysed through the identification of prototypical features, in correlation with sociolinguistic data. I also exemplify some of the issues related to perspective and scale. The treatment here is, again, somewhat preliminary. More rigorous application of the framework and methods described in the paper is the subject of ongoing research.

The extracts are from conversations which took place in May 2016 in UB’s courtyard in Brin. This is a popular social spot, as it is centrally located, and UB’s wife runs a bar from their house. All the featured speakers have individually determined linguistic repertories, each containing at least one Joola language. Table 5 shows the speakers and the languages in their self-reported repertoires, with a very brief reason for the existence of each language. Bold face marks the Joola language in each repertoire that can be characterized as prominent in their respective repertoires, i.e., the one with which there are most familiar and comfortable, and which they associate with their patrimonial heritage. The language occupying this role will be referred to as the prominent vernacular of the speaker. The table is illustrative only – the full complexity of a linguistic repertoire can be elucidated only through lengthy and detailed description. For examples of such descriptions of repertoires in Casamance, the reader is directed to Goodchild (2019, p. 140) and Weidl (2019, pp. 184ff).

table 5. Speakers’ linguistic repertoires

Two points are of importance to the current discussion. First, not only do the repertoires differ quite considerably in terms of the languages they contain, so also do the reasons provided for the inclusion of the languages. For example, several of the speakers report the Joola language Fogny in their repertoires, but while for UB and PHB this is due to its status as a language of wider communication, for MS it is due to his having grown up in an area where it is the patrimonial language, and for JT as a result of his having worked in the Fogny region. It is reasonable to assume that these different factors will have an effect on the role the languages play in the respective individuals’ repertoires and linguistic behaviours, their attitudes towards it, and their access to the prototype (a.k.a. their ‘proficiency’). Second, this table is compiled from self-reported repertoires provided by the speakers in interviews. As will become apparent from looking at the data, a speaker’s own assessment of their linguistic repertoire may not tally exactly with what we as linguistic researchers deduce from our observations. In fact this is not problematic but provides further support for the position that any description of a language or of multilingual discourse must be based on a thorough and holistic methodology where structural data is correlated with information about not only the speakers but also the relationships between them and the context of the conversation through a process of triangulation (Goodchild & Weidl, Reference Goodchild and Weidl2016; Weidl, Reference Weidl2019, p. 114). This dialectic approach allows the accommodation of seemingly clashing interpretations of language use through the recognition and integration of different perspectives. Multilingual discourse is not analysed on the basis of presupposed abstractions of the various languages involved, nor is a definitive description the aim of the analysis. Rather, we can gain information about features of languages, and their prototypicality and salience, according to the sociolinguistic context and purpose in which they are uttered, and vice versa, in an iterative fashion.

The first extract (Example 1) is an example of receptive multilingualism, as described in Section 2.2 above. It features UB and MS, both from Brin, whose prominent vernacular is Kujireray, and JT, a fisherman from Batiñer (a village in Mof Ëvi), whose prominent vernacular is Banjal. Also present is PS, a palm wine harvester from the village of Mlomp in the Kasa area, who lodges with UB annually for several months to exploit local palm groves. His prominent vernacular is Kasa, which is less closely related than Banjal and Kujireray, as evidenced in more extensive differences in its prototypical features (based on the grammatical description by Sambou, Reference Sambou1979, work on Joola classification such as Segerer & Pozdniakov, Reference Segerer, Pozdniakov and Lüpkeforthcoming, as well as my own observations and extensive discussion with speakers). Unlike Kujireray and Banjal, Kasa has significant reach as a language of wider communication in the southwestern part of Casamance and so is claimed in many people’s repertoires. All these speakers know each other well, and have more or less equal social status.

example 1. Extract from recording BRI060516UB

In the extracts, bold type is used to mark prototypical features of Kujireray, underlined for Banjal and italic for Kasa. French forms are contained in square brackets. All forms in regular type are not identified as belonging specifically to one language or another; rather these are forms that can be associated with two or more of the languages in question (although the current notation does not allow us to indicate between which combination of the languages the form is ambiguous – see below for discussion on scale and perspective).Footnote 14

While much of the linguistic material is not specified for a particular language, nevertheless each speaker is making use of some prototypical features associated with a particular Joola language. Moreover, the features used by each speaker correlate with their prominent vernacular – UB uses features prototypical of Kujireray, JT of Banjal, and so on. Thus, we can see that a feature-based description of languages is particularly useful in the analysis of multilingual discourse where the languages are closely related. However, the situation is more complex than it is possible to convey in two-dimensional text; there are multi-faceted issues of scale and perspective at play. First, not all of the shared linguistic material is shared between all the languages – there are different patterns of overlap. In some cases, the material is common to all three Joola languages. For example, in the first utterance it is only the feature [t] in the prohibitive form tanulob ‘don’t say’ that indexes Kujireray. That is to say, it is the only segment that is a salient feature of Kujireray with respect to the other two languages. The rest of the form is prototypical of all three of the languages. In a different constellation of similarity and difference, a subject marker of the form nV (as in nujuge ‘you see’) is not marked as a particular Joola language because it is prototypical of both Banjal and Kujireray. However, it does stand in opposition to Kasa, in which (singular) subject markers prototypically have the form dV- (as in da-kuetol ‘he stole from her’). In this case the nV- subject marker is a salient feature of Kujireray and Banjal with respect to Kasa, but when Kujireray and Banjal are juxtaposed it is no longer salient.Footnote 15

Since the mark-up shows only prototypical features salient for specific individual languages in the particular conversational context, it would look different in another context – say a conversation between only a Banjal and a Kasa speaker where the contrast between nV- and dV- becomes more salient. These notation conventions cannot therefore represent scale effects; development of an adequate solution to such issues is the topic of ongoing exploration. These observations regarding ambiguous (i.e., prototypical of more than one language) forms also highlight the importance of sociolinguistic data. were they to be examined in isolation, on purely structural terms, it would not be possible to state which Joola language they belonged to. If we examine them in conjunction with the sociolinguistic profiles of the speakers, and the context of the conversation, including the type of occasion and the respective relationships between speakers we can more convincingly claim that a speaker is using a particular language.