1. Introduction

In a volume of papers of several of the Sienese academies of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, there is an odd document. Anonymous, illustrated, and chaotically assembled, it is entitled “Capricciosa contentione tra la Zucca dell'Intronati et il Vaglio di Travagliati, e nel perfetto numero, l'Accesa Pina degli Accesi, Intronandosi, Travagliandosi, et Accendendosi fra lor; chi sia di lor piu nobile, maggiore, di piu virtuoso valore, e di piu alto misterio” (“Fanciful Dispute among the Pumpkin of the Intronati, the Sieve of the Travagliati, and — in the Perfect Number — the Burning Pine Cone of the Accesi, Stunning, Travailing, and Burning among Themselves as to Which of Them Is the Most Noble, the Greatest, of Most Virtuous Valor, and of the Highest Mystery”).Footnote 1 That this bizarre eighty-folio manuscript remains anonymous is not a surprise. A jibe at the Trinity appears in the very title, in the “perfect number” of three academy emblems — a pumpkin, a sieve, and a pine cone — who vie for supremacy. And many of the comments in the course of the dialogue will go much further, revealing a satire that is often heretical and blasphemous. By analyzing this dialogue, we can reconstruct a moment in sixteenth-century Siena that illustrates the tensions between literary academies and Counter-Reformation energies in the city. This episode reveals several ways in which the larger process of secularization in early modern Italy played out: a complaint on the part of the laity about religious restraints on culture, a semiotic battle between secular emblems and sacred images, and a tug-of-war between materialism and secularism in which the academic banquet vies with the Holy Communion. The dialogue's humor thus works on two fronts. Most immediately, it depicts a lighthearted rivalry among the academies of the Intronati, the Travagliati, and the Accesi. But beneath this rivalry lies a far more important satire that exposes a more serious cultural contest in sixteenth-century Italy: the Counter-Reformation bumping up against late Renaissance culture.

Probably written when the Sienese academies were closed down by the Medici grand dukes, this unsigned, undated work presents an unusual case history in the genre of underground literature. Playful and burlesque, the dialogue likely had roots in the rich ludic culture of Cinquecento Siena, but how and why did such a work transform the comic to the sacrilegious? Constructed as a hoax (but one that readers could see through), the text operates on two levels, one offered by the fictive author, another by the actual author. The tension between the two texts, moreover, generates the singular historical meaning of this work as a dramatization of Nicodemism, or feigned orthodoxy, in sixteenth-century Italy. This mordant picture of religious simulation offers new evidence for understanding the nature of heterodoxy, or even unbelief, in the sixteenth century.

2. The Sienese Academies

The emergence of the sixteenth-century Italian academies changed intellectual, social, and religious culture. Above all, they marked an effort to reclaim the vernacular after a century and a half of Latin-dominated humanist culture. In fact, the famous Academy of the Crusca in Florence had as its chief goal the standardizing of the volgare, as evidenced in its production of a Vocabolario in 1612.Footnote 2 With the collaboration of an increasingly popular press, translations of classical works into Italian and learned original works in Italian began to appear, a trend notably pioneered in Siena by Alessandro Piccolomini (1508–78) of the Academy of the Intronati.Footnote 3 When the Reformers’ call for vernacular scriptures began to percolate, the emphasis on the volgare became a potential threat to scholastic learning and ecclesiastical authority. And when these academies sponsored lectures on, for instance, Dante — who was sometimes referred to as the Theologian — the literary societies broached a realm that the Church saw as its own. Finally, because the academies, especially in Siena, sometimes sought to draw women into their cultural orbit, the traditional gender boundaries of intellectual life were partially dismantled. This mix of a resurgent vernacular, intellectual popularization, religious reform, and social innovation created a stew of cultural change and even subversion.Footnote 4 This was particularly the case in Siena, where the academies of the sixteenth century were known for their parlor games, a ludic tradition that could alternately imitate and subvert reality.Footnote 5

Emerging in the later 1520s and early ’30s, the two earliest enduring academies in Siena were the Intronati and the Rozzi, the former an association of the elite, the latter an artisan group. Both academies staged plays, and their theatrical productions accounted for their notoriety.Footnote 6 In the case of the Intronati, these productions were a natural extension of their festive gatherings that honored and entreated elite women of the city, as evidenced by their production of the Sacrifice (1532), in which, weary of being rebuffed by the Sienese women, Intronati members sacrificed their love tokens on the altar of love.Footnote 7 Such ludic performances blossomed into full-fledged comedies that treated amatory themes, often involving the use of sexual disguise and the defiant triumph of romantic love over arranged matches. And if these comedies could at times critique social conventions, such as marital practices, they could also challenge the political and religious order. The Intronati's L'Ingannati (1532) and the Rozzi's Travaglio (1552) both took aim at the imperial Spanish occupation of the city, which had begun in 1530: in the preface to the latter play the author reports that “this comedy made such a great war on [the Spanish], they wished to seize us.”Footnote 8 By the time the Intronati's play La Pellegrina, written in the 1560s, was performed in Florence in 1589 for the wedding of Ferdinando de’ Medici, some of its anticlerical content had been necessarily excised.Footnote 9 Thus the academies’ comedies, their most overt form of public culture, could be a source of tension for various reasons. It was, however, not only their plays that could be subversive, but also their ludic life in general.

The leading academy for the well-born in Siena called itself the Intronati (the Stunned), because the members aspired to be oblivious to the affairs of the world: De mundo non curare, as one their six precepts states.Footnote 10 The desire for escapism was occasioned by the Italian wars of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, which had “banished any thought other than that of war and interrupted and destroyed all literary endeavors.”Footnote 11 This last statement, in the undated earliest statutes of the academy, followed upon an allusion to the Sack of Rome of 1527, and thus this date is taken by some to be the founding date.Footnote 12 In any case, the Intronati expressly forbade political discussion, and prescribed literary pursuits in the liberal arts as well as provided for a more playful realm, “giving freedom to everyone of the said group to be able through the exercise especially of wit to propose conclusions, mottoes, jargon, emblems, and new idioms.”Footnote 13 Emblems and mottoes were indeed at the heart of the academies, as they each formulated a group emblem and accompanying motto; and the creation of personal emblems would become one of the Intronati's favorite parlor games.Footnote 14

The Intronati's emblem was a pumpkin crowned with two pestles and the adjoining motto MELIORA LATENT (“The better things lie hidden”). Dried pumpkin gourds were often used to store salt that had been ground with pestles. At one level the emblem suggests that the wit and worth of the individual lies in the head, and thus the Italian phrase for a numbskull was one non avere sale in zucca.Footnote 15 In his Dell'imprese, Intronati member Scipione Bargagli (1540–1612) offers a thorough explanation of the motto, suggesting that the salt is wisdom and is the fruit of “virtuous exercise,” akin to the use of the pestles to pound and refine the salt. Recognizing the dichotomy between the imperfect body and the perfectible mind, the academy aspires to develop this higher part of the individual to “greater nobility, stability, and perfection.”Footnote 16 The result is the rare and valuable refinement of salt (the mind) inside the outwardly rough pumpkin (the head). Given, however, the sometimes bawdy tone of the academy and the pornographic turn of one of the founders — Antonio Vignali, who wrote the highly obscene La cazzaria — there is likely an alternate sexual meaning as well: the pumpkin could be construed as a scrotum, the salt as semen (or testicles), the pestles as phalluses.Footnote 17 This vulgar subtext becomes all the more relevant when juxtaposed with the theological interpretations given to the emblem in the “Fanciful Dispute.”

This lewd dimension also has a larger context within the activities of the Intronati during the season of Carnival. A traditional time for bawdy behavior, this period was the setting for many of the festive, theatrical pursuits of the Intronati, including parlor games that included women. In the 1560s Girolamo Bargagli (1537–86), Scipione's brother, wrote a Dialogo de’ giuochi che nelle vegghie sanesi si usano di fare (Dialogue Concerning the Games Customarily Played at Sienese Soirees), and shortly thereafter Scipione himself wrote his Trattenimenti, a literary depiction of games set during the siege of Siena in the previous decade.Footnote 18 Girolamo's dialogue is especially relevant to us here, because this retrospective work discusses the emergence of the Intronati, catalogues 130 of their games, and reflects on the cultural theory of such play. It appears that games could be an area of controversy, not only in the realm of sexual propriety but also in that of religious orthodoxy. One section of the treatise purports to disapprove of obscene games and similarly classifies a questionable group of religiously themed games in an “index of forbidden games,” an obvious echo of the papal Index of Forbidden Books, which first appeared in 1559.Footnote 19 Heretical currents in the city date from the later 1530s and ’40s, with Agostino Museo's predestinarian preaching in 1537, the influence of Juan de Valdés on Aonio Paleario and Bartolomeo Carli Piccolomini, and the exiled Bernardino Ochino's 1543 letter on solifidianism to the Sienese Balìa. The first major crackdown by the authorities came with the investigation of Socinianism that led to the exile of Lelio and Camillo Sozzini in 1545; the Church began to intrude on the Intronati in the aftermath of Florence's official absorption of the city in 1557. Questions concerning some members of the Intronati, such as Girolamo's good friend Fausto Sozzini, nephew of Lelio and Camillo, prompted the entry of the Inquisition into the city in 1559.Footnote 20

When the general of the Jesuits Giacomo Laínez launched an investigation of the Intronati, two members of the academy, Alessandro Piccolomini and Giovanni Biringucci, argued that of the “sixty or seventy [Intronati], fifty are good Catholics.”Footnote 21 The decision was made to proceed against only particular individuals: while awaiting officials from the Inquisition the Augustinian figure Father Adeodato of the Leccetan order headed up the investigation, and requested the help of the Jesuits.Footnote 22 By September of 1560 Fausto had fled the city, and in a letter to him the following year Girolamo wrote, “Today the Travagliati celebrate their state but with not a little travail [travaglio], because, as their lecturer Bart[olomeo] chose to discuss the beginning of canto 21 of the Purgatorio of Dante where he mentions faith and grace, the monks, know-it-alls, and theologians are angry. They have made a fuss and proclaimed that it is not appropriate for theological matters to be discussed in academies and profane places especially by the laity, and that [such discussions] can be a source of great scandal. Whence the archbishop . . . early this morning issued an edict that in the academies it is not permitted to treat sacred matters, or to cite or interpret sacred doctors, and it is particularly prohibited to lecture on any place in Dante where he mentions theological matters.”Footnote 23

The irony is that this Travagliati lecturer likely chose this particular passage not so much because he aspired to poach on theologians’ turf, but rather because these lines from Dante (Purg. 21.1–3), dealing with the Samaritan woman at the well in John 4:7–15, made use of the term travagliava, their eponym. In a letter of 1562 Bargagli dissuades an acquaintance from coming to Siena to improve his spirits by warning that the city is currently no fun and quite oppressive: “Here, anyone who talks of the Yule log, of parties, of symbols is accused of heresy; anyone who designs pleasant entertainments for Carnival is accused of plotting against the state.”Footnote 24 This reference to symbols could be particularly revealing with regard to the Church's objections to some of the interests of the Intronati, and indeed earlier in this letter collection Bargagli alludes to the gift of an unnamed “book of symbols [that] has been . . . dear to me.”Footnote 25 That “symbols” were lumped with “parties” as a perceived source of heresy indicates that, aside from theology — even that found in the poetry of Dante — visual symbols could be a contested territory as well. It is quite possible that the book of symbols to which Girolamo refers was the recent Symbolicarum quaestionum de universo genere of Achille Bocchi, a work Carlo Ginzburg classifies as Nicomedist in its overtures to Reform-minded figures.Footnote 26

By the time Bargagli composed his dialogue on games a couple of years later, he thought it prudent to identify five religious games as among those on the forbidden list. Of course, he finds a way to have his cake and eat it too, because by identifying and describing these games, he ensures their survival, while his interlocutors’ prohibiting them appeases the censors. Among the games were three that involved monks and nuns — for example, accusing each other of not performing assigned duties properlyFootnote 27 — but two deal with more sensitive theological matters. One is a Game of the Temple of Venus, in which players entreat the goddess for “some amorous grace,” a game that flirts with idolatry, as Bargagli agrees, when a youth kneels on the ground before the woman posing as Venus.Footnote 28 Although this game potentially offends in the realm of religious ritual, another of these games, Of the Amorous Inferno, potentially offends in the area of “theological concepts.”Footnote 29 This game is the first described when Bargagli turns to those games “placing in ridicule our religion and where sacred things are profaned by involvement with worldly ones.”Footnote 30 In this game, the souls of lovers appear before Minos and confess “what sin they have committed in loving” and are assigned their appropriate punishment. This game is offensive not only for trivializing “the infernal pains” that scripture threatens for the wicked, “but also because, in putting it in practice, things are said whereby in yet another way theological concepts are mocked.”Footnote 31

The speaker here, Marcantonio Piccolomini (1505–79), then recounts enactments of the game that suggest players at times toyed with some of the central soteriological issues being contested by the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. He recalls one time when “a youth said how he was conducted to the infernal fire for having the opinion that it was possible to acquire the beatitude of love with work, without faith, and that with serving without the loyalty of love, one can merit divine grace.”Footnote 32 This Pelagian position (albeit applied here to romantic love) was the first of the positions on justification anathematized at the Council of Trent in 1547 — just as the Protestant position of justification by faith alone was condemned.Footnote 33 Clearly, the game-player here mocks an issue of considerable consequence to the contemporary Church. Similarly, Bargagli's speaker mentions another case of “heretical” love: “And another [young man] said that he had been brought into the infernal cloister for not having served one love only, and for not having one true faith.”Footnote 34 Certainly these ludic appropriations of theological concepts could have been intended and perceived as derisive sentiments in the highly charged atmosphere of confessional strife. In any case, by the time of Bargagli's writing of his Dialogo in the mid-1560s he took pains to pretend to censure, but also to repeat, such questionable games and comments.

As made evident in Bargagli's letter of 1561 concerning the archbishop's curb on “academic” discussions of theology, the academy that occasioned an official crackdown early in that decade was the Travagliati (the Troubled), another of the three academies in the “Fanciful Dispute.” Little is known of this academy, but one of its few surviving documents dates the founding to “around the time of the fall of the republic,” when Siena succumbed to the combined forces of Charles V and the Florentines in 1555.Footnote 35 The Travagliati's emblem was a vaglio (sieve) with the motto DONEC IMPURUM (or, according to our manuscript, DONEC IN PURUM). Since the academy's name, the Travagliati (or tra vagliati), might imply the process of sifting through a sieve, its emblem suggests that the academy purifies and improves its members.Footnote 36 Because of the ambiguity of donec, which can mean either “while” or “until,” these two versions of the motto end in the same result. The standard version, DONEC IMPURUM, then, would suggest that initiates would be sifted and tested “while impure.” This more common version appeared in Scipione Bargagli's Dell'imprese, where he suggests that all academies using the sieve as emblem intended it to indicate a desire “to render clean, pure, and unadulterated that which is mixed with other material impure, filthy, and harmful, just as it is with grain that may be gathered with tare, lupins, spelt, and similar mixtures.”Footnote 37 The version of the motto in the “Fanciful Dispute,” DONEC IN PURUM, would imply that individuals are sifted “until pure.” Either way, the meaning is clear that the activities of the academy “refine” its members.

The fruits of academic life are also indicated in the motto of the third of the three academies, the Accesi (“the Inflamed”). Their motto, which graced a burning pine cone, was HINC ODOR ET FRUCTUS (“Hence the aroma and enjoyment”). This academy was founded by Bellisario Bulgarini (1539–1619) in his home in 1558.Footnote 38 Several clues in the “Fanciful Dispute” suggest that, in fact, this treatise was most likely the product of the Accesi. At the beginning of the section of the volume of papers in which the treatise is included is the rubric: “To the Academicians of Siena and particularly to the Accesi. Consigned to Mr. Belisario Bolgarini and to Mr. Scipione Bargagli.”Footnote 39 Moreover, the pine cone, the emblem of the Accesi, seems to enjoy pride of place, as it has the opening lines in the dialogue and takes the lead when the three emblems reassemble at the end.Footnote 40 And, as we shall see, the anonymous monk in the dialogue identifies himself as a former Accesi.

This, then, is the trinity of academies that compete for primacy, and they will do so at the hands of a religious arbiter. This fictive submission to higher authority mirrors the actual submission of the academies to ducal authority from the 1560s until the first decade of the following century. Although there are some disagreements as to the exact dates and circumstances of the closing of the academies, scholars generally agree that there was a suppression of associative life, and most scholars follow Curzio Mazzi's contention that the academies were closed from 1568 to 1603, owing to the “suspicion and distrust of Cosimo de’ Medici.”Footnote 41 He appears to base his statement on a comment he cites from the “Deliberations of the Rozzi” that “‘in 1568 there reigned in our city of Siena many academies and societies . . . that . . . were all made to close down in deference to our masters [and] now with the good graces of these same [masters] the society of the Rozzi was reconstituted and they began to gather . . . the day of 31 August 1603.’”Footnote 42 In December of that same year the Intronati also reopened with an elaborate ceremony that slavishly honored the Medici Grand Duke Ferdinando and his wife Christine of Lorraine, and an oration in praise of the Intronati by Scipione Bargagli.Footnote 43 What led to this shuttering of the Sienese academies and how did it relate to the larger history of restraints on associative and festive life in the city?

Early in his reign Grand Duke Cosimo I (1519–74) recognized the political ramifications of cultural life in Florence, as evinced in the early 1540s, when he swiftly co-opted the newly formed Academy of the Umidi and transformed it into the Florentine Academy.Footnote 44 In the following decade he was reminded of the dangers of ignoring unlicensed festive life.Footnote 45 As for academic and festive life in Siena, local authorities had sought to rein in revelry and private gatherings a couple of times in the second quarter of the sixteenth century. In 1535, apparently targeting a popular political group called the Bardotti, the Balìa issued proscriptions against academies and “private congregations”; in 1542 it issued restrictions on parties and masquerades during Carnival, even punishing individuals participating in a comedy staged in a private home.Footnote 46 Closer to the period examined here, the potential hazards of festive life and the potential for conflict between lay and religious groups were made evident in a 1656 incident that ended in violence. At the start of Carnival the university students made their customary canvass of the city for funds to underwrite the seasonal festivities. When they arrived at the Augustinian monastery, the monks pelted them with rocks and bricks from the roof, exulting in their victory as if, according to one report, they had been battling the Turks. There were fatalities, arrests and other punishments were meted out all around — with some of the German students reported to the Inquisition — and the matter was taken to the authorities in Florence by an embassy of students.Footnote 47 As this last point reveals, such Sienese events had by now become the official concern of the Florentine overlords, and the subsequent years saw the tightening grip of the grand dukes in concert with the intensifying zeal of the Counter-Reformation.

In fact, not long after Siena fell under the official control of the Medici grand dukes in 1557, papal politics and personal ambition conspired to drive Cosimo toward an increasingly harsh stance on religious dissent. In 1559, with the ascension of Gian Angelo de’ Medici (from a Milanese branch of the family) as Pius IV, the ties between Florence and the papacy were strengthened, as a cardinal's hat went to Cosimo's sons, Giovanni and Ferdinando, in succession over the next few years. As for Cosimo's pursuit of heresy in Siena, in a letter of 1560 to the Inquisition he proclaims himself “the fiercest persecutor of heretics.”Footnote 48 In 1566 Cardinal Michele Ghislieri, who in 1559 had headed the Inquisition's investigations of Sienese heretics, became Pius V, and the Tridentine persecution of Sienese figures intensified. Various intellectuals were caught up in the purge, including Achille Benvoglienti, to whom some Intronati members had ties; the Intronati member Marcantonio Cinuzzi, whose poem De la Papeide was strongly anticlerical; and the Intronati member Mino Celsi, who fled the city in 1569 and later wrote a treatise on toleration.Footnote 49 Cosimo's complicity in stepping up persecutions was clearly tied to his desire to be elevated to Grand Duke of Tuscany, a title bestowed as a gift from the pope. The extradition of Cosimo's Florentine acquaintance Pietro Carnesecchi, who was executed in 1566, was undoubtedly the greatest concession that Cosimo made to earn his title, which the pope conferred on him in August 1569.Footnote 50 When enumerating the sixteen reasons for bestowing this honor on Cosimo, Pius V listed first his vigilance in safeguarding Tuscany from heresy.Footnote 51 It is likely that the combined forces of the pope's religious convictions and Cosimo's political ambitions led to the hardening stance against heresy in Siena in the late 1560s.

Cosimo's son Francesco, who from 1564 served as Cosimo's coregent, also played a notable part in the tightening control over religion in Siena. In March 1567 he wrote his deputed governor of the city, Federigo Barbolani da Montauto, that he had heard that German — that is, Lutheran — students at the university were contaminating the city with “their false opinions.”Footnote 52 Ten days later Francesco's wife, Joanna of Austria, daughter of Emperor Ferdinand, also wrote Federigo, asking that he facilitate a transfer of a benefice from the local parish clergy to the Jesuits.Footnote 53 These letters from husband and wife on the religious life of Siena were surely not unconnected. As for Francesco's concern about the German students, Federigo responded with letters in May and June of 1568 ordering that officials at the customs gates and elsewhere should be on guard for those bringing in “damned books.” He added that he had alerted proprietors of inns and other establishments to determine what stripe of foreigners were afoot in the city, “in order to execute your orders against them, as occasions present themselves,” and that he would enlist the aid of local religious groups, including the Jesuits, to help with this surveillance.Footnote 54 In December of the following year, a bonfire of banned books took place in the piazza of San Francesco, the seat of the Inquisitors.Footnote 55 Certainly, all the evidence points to a serious lockdown of the city in the period motivated by religious concerns — or, in Cosimo's case, religious politics.

According to the most prominent Intronati memorialist of the following century, Girolamo Gigli, the suppression of associative life in this period applied not only to academies such as the Intronati and the Rozzi, but even to the Confraternity of Madonna sotto lo Spedale: so much were all lay organizations under suspicion.Footnote 56 As we have seen, the blight on festive life was evident already in 1562, when Girolamo Bargagli lamented that games and parties were seen as heretical and Carnival entertainments as seditious. By January 1569, this repressive chill had become a deep freeze. During Carnival of that year, a group of men wanted to gather into a festive “court” strictly devoted to women.Footnote 57 The chronicler of this court, an Intronati figure called Fortunio Martini, remarked on the boldness of such a gathering (at the home of Pietro and Gironimo Cerretani) in such a troubled political climate: “the bad temper of the times that came before and after this decision [to form this court], as everyone knows, was such that in Siena [it] virtually impeded others from leaving their own homes, and did not even allow [citizens] to be found together.”Footnote 58

Finally, if Cosimo wanted unauthorized groups to be less visible in Siena, he certainly wanted an authorized group to be very visible. Surely it is no coincidence that in this same period, June 1568, he established a new order of knights, drawn from the nobility, to police Florence and Siena and to be the standard-bearers of ducal power.Footnote 59 As Jürgen Habermas might frame it, the unlicensed “public culture” of the academies’ comedies and assemblies was countered by a traditional courtly culture: in 1591 Scipione Bargagli himself published a set of emblems he and other Sienese literati composed in honor of this band.Footnote 60 Both by overt suppression and aristocratic revanchism, the Medici grand dukes seem to have successfully silenced and co-opted the strongest of the Sienese voices. It would appear, however, that there were some dissenting voices, even if they remained anonymous and behind the scenes.

3. A Comic Emblem Contest

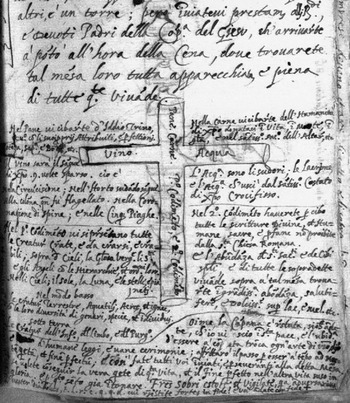

The treatise's dialogue per se opens with the three emblems, which, contending among themselves for moral and spiritual status, agree to take the case to “one who may tell us the truth.”Footnote 61 This arbiter turns out to be an unnamed monk, identified in the margins throughout as “A” and twice in the text as “Brother And.co,” at whose monastery the three emblems convene. Two documents that precede the dialogue purport to be written by this same monk. The first, headed with monograms of Jesus and Mary, is addressed “To the Academicians” and is joined on the facing page with images of the three emblems-cum-mottoes of the Intronati, Accesi, and Travagliati (fig. 1). The one-page address signals an attempt at conversion by opening with a punning invocation to the academy members to mend their ways and come to the straight and narrow: “Oh come Travagliati from the devil, Oh come Intronati from the filthy world, Oh come Accesi from carnal lust to these better emblems, to these insignias more sifting in purity, and to this brighter and better lit pine cone.”Footnote 62 The imagery overtly encroaches upon the theological realm when the Travagliati, “troubled in the Cross of the sieve,” are beckoned to come “to him, until pure, and you Travagliati will be restored and find peace in your souls.”Footnote 63 This invocation then welcomes all to partake of bread and wine in terms that allow ambiguity as to whether a Eucharist or a drunken revelry is indicated: “Oh Burning Pine Cone, come to this BREAD ardently that anyone does not want unless we all eat, enjoy, and ardently desire; and (O Intronati) if you are thirsty . . . come to this vineyard, to this vine, to this bunch of grapes and with your two pestles make wine inside your pumpkin, so that each vein is filled, and if you want to obtain some sooner, come into the wine cellar, and bending to the cask kiss the taps and then drink and become drunk, dear friends.”Footnote 64 This invitation is riddled with contradiction and irony. On the one hand, this summons echoes a call to Communion to partake of bread, which all should ardently desire, and of wine, to be sought in the true vineyard and vine.Footnote 65 On the other hand, the closing lines draw from the Song of Songs, the most sensual of the Bible's books, and urge all comers to bend to the cask, kiss the taps, and get drunk.Footnote 66 This closing line is probably the best indication that the document, despite its supposed religious authorship, might really be the product of ludic, drunken revelry.

Figure 1 Preliminary page and illustration of the emblems of the Academies of the Intronati, Accesi, and Travagliati in “Capricciosa contentione.” Siena, Biblioteca Comunale degli Intronati. Y.II.23, fols. 298v–299r.

The second of the treatise's preliminary documents adds a framework that is unequivocally religious. This piece, with the heading “In Christ, Dearest Friends, with Health and Peace,” purports to have been written by a Sienese monk who has been in an Augustinian monastery in Rome for the past two years.Footnote 67 This figure recounts how members of three academies frequented this monastery in Rome — which even displayed their emblems — and how they were often invited to hear, or even to present, lectures. He reports furthermore that these visitors were greatly improved by hearing the lectures of an unnamed chapter head and theologian: “seeing these [academy members] profiting more each day in the studies of philosophy and theology under the guidance of Reverend Father Master Evangelist ______, who with such great exemplary life and Catholic doctrine guides and conducts them to the gate of doctrine and health.”Footnote 68 The edification of these academy members in Rome set him to thinking of the academicians in his native Siena, and he decided that he would try to emulate his Roman chapter head by writing a work to similarly uplift them. He claims that his attempt “to weave a certain whimsical fabric” did not fully come to completion because of the “obligations of the Church and religious obedience,” so he gave over the manuscript in its raw condition to two old friends. The crucial passage of this fictive framework comes in the monk's statement of his specific goal, namely, to create a “fabric of actions and words that would persuade and prevail in your academies to make all of the Intronati into wise Jesuits, all the Travagliati into pure and good Inchiodati, all the Accesi into seraphic and devout Bernabites of our oratory in San Martino.”Footnote 69 The dialogue, then, is framed as an attempt on the part of an Augustinian monk to convert secular academies into religious orders and congregations. The context of the forthcoming “Fanciful Dispute” is now truly evident. Rather than being a contest for spiritual primacy among secular academies, its putative subject, it is actually a struggle between secular societies and religious ones.

This passage also lays out the religious landscape of Siena and offers clues as to who the supposed religious author of the dialogue was intended to be. Obviously, he would come from one of the three religious groups mentioned in the passage above. Jesuits had a presence in Siena at least by 1556, and, as mentioned earlier, outside Jesuit officials came into the city in 1559 to investigate heretical currents that implicated the Intronati.Footnote 70 But the author likely was not intended to be identified as a Jesuit or an outsider, but as someone from one of the two societies named, both of which were native to Siena. The reference to the Inchiodati alludes to the Congregazione de’ Sacri Chiodi, a religious sodality that was established in 1579 in the Capella del Chiodo (the Chapel of the Nail, alluding to the nails of the cross) located in the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala; the Chiodi moved to the church of San Giorgio in 1584. The group was founded by Matteo Guerra, a leatherworker who since 1567 had worked as a volunteer in the hospital, where he ministered to those near death.Footnote 71 As a youth, Guerra had accompanied an older acquaintance, Mariano Tantucci, to the Council of Trent, which energized his religious tendencies, as he returned to Siena “resolved to give himself wholly to the contempt of the world.”Footnote 72 He was a particular enemy of cards, dice, and gambling — and this “zeal against gambling” might be a relevant factor in understanding the conflict between the academies, with their sometime ludic activities, and the religious orders.Footnote 73 In fact, one of the Chiodi's later statutes from 1620 provided that members should monitor initiates to learn whether they went “to comedies, parties, banquets . . . whether they gambled, and [engaged in] other such things not appropriate to anyone professing a spiritual life.”Footnote 74 Gambling could overlap with heresy as a target of Guerra's society: in the year of the congregation's founding Guerra and his associates raided the house of a devotee of the heretic Bernardino Ochino (1487–1564), confiscated all his gaming paraphernalia, and took it to the altar of the chapel.Footnote 75 Clearly, the dissolute ways of heresy and all manner of gaming and entertainment were lumped into one heap of deviance by this Counter-Reformation association.

The third religious group mentioned in the prefatory piece is rather confusingly identified as the “Bernabites of our oratory in San Martino”: confusing because the Barnabites, named after the church of San Barnabas in Milan, were indeed an order that emerged in the sixteenth century — but the group at San Martino in Siena was the oratory of San Bernardo.Footnote 76 Perhaps the author was attempting to humorously combine the two into “Bernabites.” In any case, the Siena group was founded by the Augustinian monk Andromaco d'Elci, who lived at the monastery of San Martino, was a friend of Matteo Guerra, and became a member of the Chiodi.Footnote 77 This Andromaco was probably the figure parodied as Brother A, or, more tellingly, Brother And.co, which surely must be “Andromaco.”Footnote 78 As Andromaco d'Elci not only founded the oratory of San Bernardo but also joined and aided the Chiodi, he links these two groups satirized in the dialogue.Footnote 79 In fact, Andromaco helped secure the Florentine grand duke's support of the Chiodi, shortly after it was officially recognized by Pope Sixtus V in 1585 and granted possession of the church of San Giorgio.Footnote 80 The composition of the work, then, likely dates between 1584, when the Chiodi moved to San Giorgio, and 1593, the year of Andromaco d'Elci's death.Footnote 81 Owing to its mockery of religious societies, it is likely that the treatise was written during the period when the academies were closed down by the Medici grand dukes, and thus unlikely that it was composed after their reopening in 1603. As for 1593 as the terminus ad quem, the author would probably not have targeted Andromaco after his death: this would have been bad form and little fun.

4. Secular Emblems and Sacred Meanings

The monastic judge A, or Andromaco, is depicted in the dialogue as a not-particularly-focused monk. In a string of puns rooted in the names of the academies, he reveals that his spiritual constitution is weak, that he is “troubled” and little able to become “inflamed” in prayer.Footnote 82 While such double entendres occur throughout the dialogue, in this instance they emphasize the rivalry between monastic societies and lay ones. Brother A prays for help to resist the distractions of the city, and he says that he has never been able to achieve the contemplative peace of a John the Baptist, a Paul, or an Anthony. God hears his plaint and delivers the chatter of the emblems outside his door to remind him of the disturbances of lay life. But the opposite result ensues. The monk smells the aroma of the burning Pine Cone of the Accesi and is enticed to venture forth. Thus, even as sensuous temptation lures him out, he cites the demands of charity in the model of Martha and the active life to engage the visiting emblems (fig. 2).Footnote 83

Figure 2 “Capricciosa contentione.” Siena, Biblioteca Comunale degli Intronati. Y.II.23, fol. 302v.

That the smell of the Accesi Pine Cone seduces him reinforces the likelihood that this treatise is the work of the underground Accesi academy. This is even more evident when Brother A reveals that he himself is a former Accesi member. When the emblems appear before him, they profess their literary and cultural domains, proclaiming that under their standards were to be found “clear and famous rhetoric, charming and terse poetry, and the most learned and widespread philosophy.”Footnote 84 At the same time, however, they apologize for asking a monk to rule on their dispute, because theirs is such a vain realm, and they confess to having no aspirations to spiritual matters. In fact, they even (facetiously) own up to a certain “holy envy” of other pious souls in the city who follow the higher path “under the guidance of priests and monks.”Footnote 85 But just as the emblems disavow their own spirituality, Brother A disavows his own secular talents. He admits that he has always lacked skills in rhetoric and poetry, and that before he became a monk all of his literary efforts, despite the investment in “much time and oil,” were in vain. And then the other shoe drops, as he reveals that he is a former Accesi member: “When the time came (it suiting whomever) when I separated myself ab hoc vano seculo and from my most friendly Accesi Academicians, every observance of Tuscan writing, poetry, and rhetoric was given to the Accesi flames.”Footnote 86 The author of the dialogue has thus made of Brother A a failed Accesi member, whose lackluster literary efforts were consigned to the fire. The poor fellow is portrayed not only as a spiritually distracted monk, but also as a literary failure from their ranks: he is neither good monk nor successful Acceso.Footnote 87 This contest is visually expressed in an illustration in the manuscript in which the images and mottoes on the left side of the picture represent the three academies, and those on the right represent the Church (fig. 2). The religious mottoes attempt to trump the lay ones in their own terms. Thus adorning a monastic structure is “without comparison hence the better things lie hidden”; the monk's own cell proclaims “hence the better enjoyment and aroma”; and several of the rounded entries of the monastery bear labels of the vaglium (sieve): for instance, the “sieve of communion,” the “sieve of sacred reading,” the “sieve of prayer and contemplation.”Footnote 88

Next comes the contest of which emblem is “more worthy of praise, of virtue, and of the highest, more excellent, and divine mysteries.”Footnote 89 This last category is the most controversial and the one that propels this dialogue past the realm of the merely comic to that of the potentially sacrilegious. As Girolamo Bargagli's letterbook of 1562 makes clear, the realm of “parties” and “symbols” often led to suspicion of heresy in the city. Some years later, in 1578, when Girolamo's brother Scipione published the first part of his book On Emblems, he too seemed aware of the potential theological dangers in this semiotic realm. Following other writers such as Girolamo Ruscelli and Alessandro Farra, he traced the origins of emblems back to the sacred images in Egyptian hieroglyphics, Orphic theology, Pythagorean number symbolism, and the Jewish Kabbalah, and surveyed as well the crowns of the Greeks, the reverses of Roman medals, the arms and insignias of medieval families, finally bringing his history up to the modern emblem.Footnote 90 The interlocutors in his dialogue make a distinction between the ancient focus on “divine and natural concepts” and the modern emphasis on “human thought and affects” in order to warn that modern emblems should avoid the loftier mystical character of the ancient tradition and instead apply strictly to the human, intellectual, and moral realm. Because certain images drawn from the Bible have an established iconographic association — the lyre with David, the dove with Solomon, the lamb with Christ — these should not be used to indicate anything other than “mysteries lofty and worthy of our most sacred religion.”Footnote 91 Scipione Bargagli's injunction to respect the symbolic integrity of the mistieri alti here stands in notable contrast to the very title of the “Fanciful Dispute,” which describes a contest between secular emblems to lay claim to their alto misterio.

Thus the template for an unholy conflation is set. After resolving the unstated problem of talking to a pumpkin, sieve, and pine cone — by invoking such precedents as St. Anthony preaching to the fish, a blind Venerable Bede preaching to a pile of rocks, Moses and the burning bush — Brother A takes up the task of assessing which of the emblems is most praiseworthy and most steeped in divine mysteries. The emblems state their hope for the miracle of not feeling envy when each hears good things said of the others, and even venture, “who knows, but with a little more time and more arguments of religious zealots, we may be able to become good emulators and emulate the better gifts?”Footnote 92 The text thus teases that perhaps even reprobate literary-academy types can be moved to piety by Brother A.

Befitting the Intronati's being the earliest of these academies, the emblem analysis of the Pumpkin comes first. This fellow endures the most abuse in the dialogue: partly because of the innate humor and mockability of pumpkins — as Seneca realized in his satire on the “Pumpkinification” of Emperor ClaudiusFootnote 93 — and partly because the Accesi are keen to take jabs at the Intronati, their forerunners and most prominent competitors. In an opening speech, the Pumpkin laments his lowly, derided stature and describes how he mightily resists, but loses, the battle of being plucked from the ground at harvest time. Once plucked, he becomes food for the poor, and when not eaten, he is saved by poor farmers as a repository of salt. The Pumpkin's self-denigration is countered by Brother A's lengthy praise of simplicity — partly in Latin and drawn from Jan van Ruusbroec's mystical De ornatu spiritualium nuptiarum — and a paean to humility, a spiritual virtue that can lead to a “heroic humility.”Footnote 94 As for the ridicule the Pumpkin endures, the monk combs scholastic theology and the Bible for warnings against this vice, which is doubly ironic because the dialogue applies moral virtues and vices to a pumpkin and, in mocking the clergy, engages in this very sin of derision. The exhaustive analysis Brother A delivers, with citations from the likes of Thomas Aquinas and Ranieri Giordani da Pisa, satirizes the method and excesses of scholastic learning.Footnote 95

The assault on the religious world, however, becomes much more irreverent, when the dialogue renders the mystical meanings of the pestles. These objects, placed “in the mode of a cross,” are said to represent the “humanity and divinity of Christ” on the cross. The motto now has a fully theological significance tied to Christianity's most dramatic moment: “The motto, The Better Things Are Hidden, could be said to denote Christ crucified in the middle of the two thieves in outward appearance as King of thieves and culprit but inside lies hidden Innocence, Goodness, Sanctity, Wisdom, and Divinity, etc.”Footnote 96 This motif is then extended to the pestles, which, it should be remembered, are objects to grind salt and are also phallic symbols. These now are equated with the two precepts of charity, fear (of damnation) and hope (of divine grace); with hell and paradise; with the active and contemplative life; and so on. A highpoint in the dialogue's juxtaposition of the ridiculous and the sublime concerns the motif of the pumpkin as a “teacher of the spiritual life that instructs us in swimming in the water of this world and does not let us sink, submerge, or drown.”Footnote 97 In a striking parody of religious analogy, the author explains this in absurd detail: “Just as those who learn to swim do not place the pumpkin in front on the stomach but rather in back on the shoulders, so one ought to do with good works and spiritual life, as St. Augustine teaches: namely, that all the good deeds we do ought to be placed after [or behind] the back and before we ought to place our sins, our evil life, and the omission of the precepts and counsels of Christ and of the Holy Roman Catholic Church.”Footnote 98 Dried pumpkin gourds were a common flotation device, and here mockingly symbolize the buoying of a Christian to a proper spiritual life.Footnote 99

The monk's exegesis of the mysteries of the Intronati's emblem ends with his citation of the seven transformative properties of salt, which he ascribes to a recently published lecture on the same by his mentor the Rev. Father Master Evangelist back in Rome. According to this learned treatise, salt is likened to the “wisdom of evangelical preaching” as an agent that effects, for instance, a transformation in man “from the state of sin to that of grace through the contrition of the heart of the true penitent,” and so on.Footnote 100 The seven examples of “transmutation” do not go so far as to incorporate the notion of transubstantiation, a key issue in the confessional wars of the century, but the implication is there. And the seven transmutations call to mind the seven sacraments, which themselves all achieve the transference of divine grace and transmute the worldly into the spiritual. At times this section may reveal Protestant irony. One of the transformative properties of salt is its capacity to improve the lot of man (as does salt the meal), bringing about — in Latin here — a “transmutation through which there may be effected a transition from the pursuit of the active life to the choice of the contemplative life.”Footnote 101 And while the active/contemplative paradigm of course had a long tradition before the Reformation, the primacy of the celibate clerical and monastic life over married lay life certainly remained a contested issue in the confessional debates.Footnote 102 Even more striking, in the introduction to this section of the treatise there is an indication of the clerical estate's desire to impose its regimen of spirituality onto the laity, a common complaint in the urban Protestant populations of sixteenth-century Germany and Switzerland.Footnote 103 Turning to enumerate salt's seven powers, Brother A comments, “I come now to the learned lecture of the above-mentioned Reverend Father Master Evangelist to show the seven properties of salt, where one learns not only the qualities required of the Pastors of the Church, the Doctors, the Preachers, the Confessors, and all the Curates and the Religious, but also how the true Catholic laity would be able through the seven conditions of salt to arrive at the perfection of the spiritual life more necessary to the altar of the conscience of each of the faithful than salt is to the dinner table.”Footnote 104 This catalogue of the divisions within the Church Militant and the belief that the standards of clerical piety must be applied to the laity has added meaning in the context of this treatise's putative goal to remake lay academies in the image of religious orders.

When next the emblems of the Travagliati and the Accesi come up for review, the same burlesque template holds, as these mundane images are invested with absurdly elevated meaning. The Travagliati's Sieve is equated with the Catholic Church, the body of Christ on the cross, and the sacrament of penance, sifting good and bad deeds through contrition and confession. Blasphemous heights are reached when the monk equates the round Sieve with the mystery and eternity of God, as a “most perfect form, surpassing all other forms and shapes in material and in the mystery of perfection and significance, because it denotes the Divine eternal, ineffable Circle . . . of God himself, who is called the beginning and the end.”Footnote 105 The complete conflation of the Sieve with the qualities of God comes in a section in which the Sieve (an object used for refining grain) is visually depicted as an icon embracing such qualities as “ineffability,” “necessity,” “incomprehensiblity,” “eternity,” and “infinity” (fig. 3). Brother A crosses the threshold to idolatry when he says that he lifts the Sieve on high and contemplates the “God Himself triune and one, and with all these things attributed to God that are in the present sieve.”Footnote 106 Then the monk replicates the Creation account of Genesis by describing the Sieve sifting the matter of the universe, from chaos separating sky from earth; sifting again to separate sun, moon, and stars; sifting again to separate plants, animals, and so on.Footnote 107 Similarly, the aroma of the Accesi's lit Pine Cone, equated with the incense of the altar, is hailed as a “thing sacerdotal, sacred, holy, and divine.”Footnote 108 The “fruit” and aroma of the burning cone mirror the Virgin, who bore the “fruit of health to the world” and who sends out the “aroma of her virginity” to attract all who may smell it.Footnote 109 Going further, he suggests that the emissions of the lit cone remind him of “Christ as God and man” and in the fire he sees “God, since the Prophet says, ‘Fire is God.’”Footnote 110 Given the lowly nature of all these academy emblems and the common knowledge that they all had secular connotations, these conflations of material objects with the most sacred figures of the Christian faith are harshly irreverent.

Figure 3 “Capricciosa contentione.” Siena, Biblioteca Comunale degli Intronati. Y.II.23, fol. 345v.

Aside from this assault on the sacred, however, there is also a revolt against the ascetic. During his review of the Sieve, Brother A enumerates the “seven notable aspects of the art of serving God well” and, in good scholastic fashion, adjoins “nine considerations and conditions.”Footnote 111 His rigorous spiritual regimen includes the advice that a proper religious life entails a recognition of the vile and transitory nature of worldly life and a willingness to endure the contempt and suffering that Christ experienced. This contemptus mundi grows all the more satirical as it waxes on at great length about the importance of self-hatred: “And should anyone exercise himself much in the above-stated rules and methods and not feel that he is making headway, he ought to beware what can result from the common negligence of acquiring the proper hatred of oneself.”Footnote 112 Anyone who cannot acquire this is “not worthy of the name of Religious, or Christian, since he does not succeed in imitating Christ in such necessary work of hating oneself.”Footnote 113 This lengthy discourse that equates the love of God and the imitation of Christ with self-hatred underscores the harsh asceticism of a monastic regimen, one especially alien to the setting of an academic drinking party (where this comic treatise was likely conceived).

The monk's review of the “higher mysteries” of these emblems parodies the most sacred reaches of the Christian faith, whether it be the sacraments and altar, or Christ and God. His imaginative interpretations simultaneously signal several things. First, they mock the rigor and excess of scholastic exegesis, a target Erasmus found easy to hit in the Praise of Folly when he ridiculed theologians for manipulating scripture as if they were shaping wax to suit their needs.Footnote 114 Second, the monk's interpretations directly contradict the intended messages of the emblems and mottoes, all of which allude chiefly to the process of cultivating “hidden” literary (or even sexual) talents, or “refining” cultural persona, or “sparking” literary efforts. Third, the monk's misguided attempts at flattery and conversion result, not in the pious elevation of the secular, but rather in a blasphemous lowering of the sacred. This conflation of the material and the spiritual comes to a boil in the descriptions of a meal at the dialogue's close.

5. A Meal Manqué

There is no definitive verdict in the emblem contest, but the monastic author includes some printed religious plates in the section on the Accesi, which would seem to give them the nod, especially as one of the plates, depicting St. Bernard carrying the myrrh, presumably emanated from Brother A's oratory of St. Bernardo.Footnote 115 Following his assessments of the three emblems, the monk invites all to partake of some lunch, described as a “Spiritual Table for Lunch for the Virtuous Emblems of the Sienese Academies and for Everyone” (fig. 4).Footnote 116 In both Latin and Italian table (mensa) can mean both “table” (for a meal) and “altar,” and the ambiguity is certainly relevant here, as elsewhere in the treatise. The diagram of the table in a cross is intended to be rotated to the left, so that the base would lie at the top of Brother A's invitation to the emblems on the facing page to drink and eat their fill.Footnote 117 On the two arms of the transverse are situated five goblets of wine each for the Intronati and the Travagliati, and on the upright ten goblets for the privileged Accesi, with whom Brother A once again here professes greater intimacy. These goblets were labeled with various spiritual qualities: thus, those for the Accesi, whose virtue ascends in flames, appropriately progress from negative or base emotions (such as grief or shame) to loftier ones (praise, reverence).

Figure 4 “Capricciosa contentione.” Siena, Biblioteca Comunale degli Intronati. Y.II.23, fols. 368v–369r.

But this banquet is deficient. The emblems object that the invitation promised a little meal, but “you have not put anything on the table but wine.”Footnote 118 This disjunction between a spiritual and material meal becomes even more pronounced in Brother A's response. He urges them to go to the residence of the “Reverend and devout Fathers of the Company of Jesus” so that they “arrive promptly at the dinner hour, [for] here you will find their table prepared and full of all these dishes.”Footnote 119 The Jesuits’ meal is similarly laid out on a table shaped as a cross (fig. 5), and the generic categories are identified on this cross as bread, meat, first and second condiments (on the upright), and wine and water (on the transverse). But the true components are identified in the theological fine print, which shows this meal to be wholly spiritual. The bread will be the “Triune God”; the meat will be the body of Christ in the Eucharist and the wine his blood (from the flagellation, the crown of thorns, the five wounds); the water, his sweat and tears. The irony becomes sharper with the identification of the second condiment, “in which you will have all the writings divine and human, sacred and profane, that are not prohibited by the Holy Roman Catholic Church.”Footnote 120 Not only then is the meal's seasoning allegorized as literature, but also it is restricted to writings that have not been prohibited, presumably alluding to the newly established Index of Forbidden Books. This “abundance of the Holy Ghost and of spiritual food, and of all the other above-named dishes, you will find on this table in the greatest abundance, healthier and sweeter than milk and honey, etc.”Footnote 121 In general, then, this Jesuit meal is an even bigger disappointment on the material front than the collation offered up by Brother A, which at least included actual wine. (As a former Acceso, this monk probably knew better than to allegorize the wine.) But both of these religious meals depict a spiritualized, ascetic ideal, an ideal even more naïve as it is presented to the material emblems of wholly secular academies. Indeed, the treatise has come full circle from its opening invocation to academy members, to come eat and “become drunk” in a rite and a revelry that allowed for some ambiguity between a Eucharist and a bacchanalia. There is no ambiguity in this fully spiritualized Jesuit meal.

Figure 5 “Capricciosa contentione.” Siena, Biblioteca Comunale degli Intronati. Y.II.23, fol. 370r.

6. Faux Conversions

The last part of the treatise reveals whether or not Brother A succeeds in his proselytizing, as the three emblems reconvene and, proclaiming themselves thirstier and hungrier than ever, decide to split up and visit respective religious groups to see if they will be admitted and seated, literally and metaphorically, at the table. The Accesi Pine Cone says that he will remain at San Martino and visit the oratory of San Bernardo, where one finds the “methods, and brief and easy rules for learning how to pray and to meditate on the Passion of Christ and on the compassion of his most pious mother; and to meditate on the Pater Noster, and the Ave Maria in a manner that few learned [word concealed] know.”Footnote 122 The Sieve offers to visit San Giorgio, where the Congregation of the Chiodi is located. There he will learn the “Twelve Rules of Dying Well, which the father has mentioned as being very necessary to any person.”Footnote 123 There was, of course, the established tradition of the Ars moriendi, but caring for the dying was a particular concern of Matteo Guerra and the Chiodi.Footnote 124 The dunce of the group, the Pumpkin, offers to go wherever the others want, so the Sieve assigns him to visit the Jesuits to partake of the meal described earlier.

The treatise visually reifies this planned conversion of the academies with semiotic conversions of the emblems and mottoes (fig. 6). Each of the three emblems is paired with a religious image that roughly mirrors its shape. The Pumpkin with its crossed pestles is paired with an urn surmounted by a woman holding a cross. This urn is labeled the “Vase of Wisdom” and, like the Pumpkin, carries the Intronati's motto MELIORA LATENT. The round Sieve is paired with a crucifix framed by a circle of phrases invoking the Travagliati whom Christ consoles with “Per me in purum.” The Accesi's Pine Cone is coupled with Moses’ burning bush, or lit tree, which “burns and is not extinguished” and bears their motto HINC ODOR ET FRUCTUS. The placement of the secular emblems at the top of the page and the religious transformations below is necessary for the narrative clarity of the story, as these academies are supposedly undergoing a conversion from the secular to the sacred. But in another gesture of orthodoxy, Brother A has written on the side of the page that “these emblems ought to be placed beneath, and the spiritual ones above.”Footnote 125 Such visual symbolism reinforces the aim of this fictive conversion narrative to subordinate the sacred to the secular. In figure 2, which depicts the emblems appearing at the cell of Brother A, the mottoes of the emblems are paired with lateral versions that emanate from the monastery: this left-right axis suggests a contest of equal forces. In figure 6, such parity gives way to hierarchy defined by a high-low axis: after the emblems are converted into religious symbols, Brother A instructs that the figures should be inverted with the spiritual images atop the secular ones.

Figure 6 “Capricciosa contentione.” Siena, Comunale degli Intronati. Y.II.23, fol. 373r.

In the closing section of the treatise the three emblems recount their experiences in visitations to their respective religious societies. Each of the three reports is illustrated with a picture that completes the process of the subordination of the secular to the religious. In the case of the Accesi Pine Cone, the emblem of the oval, lit Pine Cone, placed at the bottom, is dwarfed by an image of the Virgin (whose halo models the burning of the Pine Cone) and Christ ministering to the devoted, with the oval shape completed at the bottom by the same religious plate of St. Bernard carrying a bundle of myrrh found earlier in the manuscript (fig. 7).Footnote 126 Likewise, the Intronati's Pumpkin crowned with pestles is subordinated in size and placement to the emblem of the Jesuits, which resembles it with its circular shape topped with a cross; and the circular Sieve of the Travagliati is paired with a circular crown of thorns, placed slightly higher on the facing page (figs. 8–9). The three religious societies win the semiotic battle. But what about the battle of hearts and minds?

Figure 7 “Capricciosa contentione.” Siena, Biblioteca Comunale degli Intronati. Y.II.23, fol. 373v.

Figure 8 “Capricciosa contentione.” Siena, Biblioteca Comunale degli Intronati. Y.II.23, fol. 374v.

Figure 9 “Capricciosa contentione.” Siena, Biblioteca Comunale degli Intronati. Y.II.23, fols. 375v–376r.

All three emblems report remarkable ecclesiastic privileges, spiritual practices, and pious acts with a sense of explicit awe and implicit irony. The awe reinforces the fictive narrative frame that the work was written by a monk; the irony reinforces the real author's view that these religious societies promise more than they deliver — or, in fact, promise little of interest to the lay mind. The Accesi Pine Cone reports that the officials at the oratory of San Bernardo at the Augustinian convent of San Martino showed him a “book of the Centurati of Father Saint Augustine, full of grace, treasures, and spiritual privileges, etc.”Footnote 127 In 1575 the Compagnia de’ Centurati was recognized by Pope Gregory XIII, and three years later there appeared a massive Libro delle gratie et indulgenze (Book of Graces and Indulgences), detailing their statutes, duties, and many privileges.Footnote 128 The Pine Cone says that while he learned much at the oratory about the primacy of spiritual benefits over worldly ones, he especially heard about the “eternal goods” that can be acquired “by means of the privileges and merits of the Holy Centura of the most learned St. Augustine and of his mother, St. Monica, privileges that are such and so great that I by myself would not be able nor know how to explain to you.” He suggests that perhaps they can all return and be given such a book so that “[they] could learn about the many hidden spiritual treasures, and then . . . hear how the blessed and mysterious Centura originated,” and so on.Footnote 129 As this book's section on the confraternity's “special indulgences and stations in diverse churches in Rome” runs to 116 pages in the 488-page book, there is an obvious irony in the Pine Cone's statement that he could not possibly replicate their many spiritual privileges.Footnote 130

As for his visit to the Jesuits, the Pumpkin (Zucca) reports that even if he could become all sugar (zuccaro) and honey he could hardly report the “unspeakable sweetness of that most holy name, to whom all celestial, worldly, and infernal persons kneel, of whom they have explained the grandest virtues and graces and most salutary and holy privileges.”Footnote 131 When the Sieve assigned this visit to him, he did so because the Pumpkin is “more tasty, corpulent, and retentive of good and flavorful dishes.”Footnote 132 Indeed, as the only one of the group who is himself edible and a keeper of seasoning, he is the most gustatory of the emblems. That makes it all the worse that he never gets to eat his meal: “And although I did not enter to taste that meal in any way, I was filled with an unspeakable sweetness and taste, and they have promised me a meal at another time.”Footnote 133 Although the slow Pumpkin does not see it, the Jesuits promise more than they actually deliver in tangible terms. Easily fooled, he says that he is “content to defer it to another time,” when his fellow emblems can come.Footnote 134 But for now, “for this first time I am content to have understood the unspeakable virtues, graces, powers, and mercies of the most holy name of Jesus,”Footnote 135 and he goes on to rehearse a litany of arguments about the merits and honor of loving Jesus. This love, however, can apparently best be gained and kept only through instruction, and he suggests that he and his fellow emblems return some other time to learn “the rule for acquiring that love.”Footnote 136 He ends his report with another reference to meditating on the passion of Christ and the compassion of Mary “with unspeakable spiritual enjoyment for souls.”Footnote 137 Four times in his account the Pumpkin speaks of the “unspeakable” sweetness, virtue, and enjoyment he encountered during his trip to the Jesuits: the ineffable is unspeakable, perhaps as the meal is intangible. The satirical point is that the naïve Pumpkin seems to have been converted.

Finally, the Sieve reports his visit to the Company of the Chiodi, whose image of the nails of the cross is discussed in light of an image of the crown of thorns. He describes the Chiodi's “many devotions and frequency of work of corporeal and spiritual mercy.”Footnote 138 As the Sieve's function is to sift grain, this metaphor underlies his understanding of their piety: “I would never have thought nor believed, my dear companions, such a grand and good sowing of pious and salutary works if I had not first with my Sieve sifted and conducted them to pure truth.”Footnote 139 So impressed was the Sieve, that he was tempted to remain there, but his affection toward his companions and his promise to return sent him back to report that they too can come and “participate in all these good things they do.”Footnote 140 And so it ends. All three emblems profess that they and their companions should return to their societies, to acquire the huge book of privileges accorded the Augustinians, to eat a meal never to be delivered by the Jesuits, and to partake of the many good deeds of the Chiodi. This is the point of Brother A's naïve proselytizing to these emblems and societies. The text mocks the presumption that Sienese academy members could possibly be tempted by these religious practices, rules, and privileges. The emblems may talk of coming back, but they never will. Nor will their members be made into Augustinians, Jesuits, or Chiodi.

7. A Nicodemist Parody

Who wrote this treatise, and why? Although the document is found among papers consigned to Bellisario Bulgarini and Scipione Bargagli, the hand does not appear to match either of theirs. All the signs point to the treatise as the product of the Accesi Academy during the period when the Sienese academies were officially closed down, and specifically between 1584 and 1593. The fictive framework of the “Fanciful Dispute” suggests that the earnest monk who is the supposed author of the dialogue was a former Acceso. Given, however, the author's familiarity with scholastic learning and theological exegesis, the opposite is likelier to be true: namely, that the real author was a disenchanted religious figure — whether monk, priest, or confraternity member — who was a current member of the Accesi. Indeed, the author's possession of the Bernard plates certainly suggests a former membership in, or close association with, Andromaco d'Elci's oratory of San Bernardo.Footnote 141

Whatever the identity and background of the anonymous author, the core meaning of this penetrable hoax lies in the tension generated by the two layers of the text. Thus the fictive author's naïveté and piety underscore the real author's cynicism and libertinism. Brother A's absurd attempt at spiritualizing emblems and mottoes that have only worldly meaning sets up the true author's sacrilege of materializing divine entities that should have only otherworldly meaning. Most importantly, this tension between the feigned purpose of the work, to spiritually correct and elevate worldly folk, and its real purpose, to mock such proselytizing, reveals this to be a clever dramatization of Nicodemism as experienced in Counter-Reformation Siena. Nicodemism — derived from Nicodemus, who hid his belief in Christ — took shape in the Reformation to refer often to closet Protestants who simulated Catholic orthodoxy. Calvin unwittingly canonized the term in his 1544 Excuse à messieurs les Nicomedites, in which he chides, for instance, those who feign belief for purposes of advancement, those intellectuals who are more Platonist than Christian, and those “Lucianists or Epicureans, that is to say all the disdainers of God, who, while appearing to adhere [to belief] in word, inside their hearts mock him and think him no more than a fable.”Footnote 142 It is this last category that may apply to the anonymous author. The emblems profess their admiration for the religious societies they visit: they claim their intention to return to them. But the author makes clear that these sentiments are just simulations. The dialogue thus enacts the circumstances of the suppressed academies that would be silenced, chastened, and converted by the religious societies of the day. In the “Fanciful Dispute,” Nicodemism thus receives a star turn as a satirical literary motif, demonstrating the meaninglessness of feigned and forced conformity. We cannot know whether or how much this work may have circulated among academy members, but the partial copy in another hand that follows the manuscript does suggest some interest in it. Was it passed around for laughs? If so, what exactly might readers have been laughing at?Footnote 143

It is possible, of course, that the author was a newly converted Protestant, since the Sienese academies, or at least the Intronati, had tilted with the Jesuits and Augustinians before.Footnote 144 Moreover, as mentioned earlier, in his campaign against gambling Matteo Guerra had raided the house of a follower of Bernardino Ochino, a former Capuchin whose apostasy was all the worse for his prominence as a popular preacher.Footnote 145 Several themes in the treatise sound Protestant notes, but some of these same themes — on the absurdities of scholastic theology, or the ceremonial inanities of the religious orders — had been forcefully voiced earlier by the Catholic Erasmus. Moreover, one fact might argue against mainstream Protestant hands: namely, the nature of the work's heresy, which is more akin to blasphemy in its insolent treatment of religious themes and symbols. Protestants, who could be censorious of Catholic festivals and play, would likely not have mocked iconic symbols of the faith, even if they did so by putting them in the mouth of a monk.Footnote 146 And in fact, considering the opening invocation to eat and drink that precedes the “Fanciful Dispute,” as well as the popularity of emblem games in the academies, this treatise may well have arisen out of a spirited Accesi revelry enacting such a game. Rather than an earnest Protestant, then, this Nicodemist author was more likely a disenchanted believer, or a freethinker uninterested in religion whatsoever. If Nicodemism, in some of its faces at least, has been defined as a “prudential spiritualism,” in this case it is closer to being a prudential secularism: prudential in its anonymity, secular in its contempt for constrained religious simulation.Footnote 147 Furthermore, it is this contempt that drives the document's flirtation with atheism by trivializing the Virgin as a pine cone, Christ's humanity and divinity as pestles, and God the Creator as a sieve. Indeed, in this last image the materialist theme is most pronounced, as the sieve becomes the God of Genesis sifting out of primordial chaos the physical components of firmament and earth.

This confusion, or conflation, of materialism and spiritualism could have some roots in unbelief. The author's sacrilege of materialism is not of an unwitting nature, as was that of Carlo Ginzburg's simple Friulian miller, who garbled religious truths through a filter of oral peasant culture.Footnote 148 Rather, this materialism is intentional, and based on a clever misreading or allegorizing of religious texts and images. The author's use of the Song of Songs is especially ironic in this regard. Despite Bernard's mystical reading of this work in his sermons, it is obviously the biblical text most susceptible to a secular, erotic reading, and one that sixteenth-century French freethinkers would cite as evidence of scripture's human provenance.Footnote 149 Perhaps it is partly for this reason that our author tucks in some lines from the Song of Songs 2:4 and 5:1 in the invocation to take communion or perhaps get drunk in the opening document of the manuscript. Bernard's effort to allegorize this book is here undone by this insertion that would deallegorize it. As Andromaco d'Elci's oratory of San Bernardo was the likely target of the treatise, the author would seem to take the material battle right to the door of the “Bernabites.”Footnote 150 Together with the theme of the Jesuits’ nonmaterial meal, this appropriation of the sensual Song of Songs suggests that the author is certainly toying with the theme of the carnal versus the spiritual. And if this materialism should not be classed with the more philosophical and scientific materialism that blossoms later, it should nonetheless be seen in the satirical context of Rabelais, whose celebration of gigantism, gargantuan meals, drunkenness, and corporeal King Lent all bespeak a revolt of the material.Footnote 151

This material assault on the spiritual may well have been driven in part by a resentment on the part of the laity against the imposition of standards of piety by monastic orders and ascetic religious congregations. The rigors of the Counter-Reformation on religious life were evinced, for example, by the introduction of the Quarant'ore (Forty Hours), a lengthy devotion commemorating the time between Christ's burial and resurrection.Footnote 152 A letter from a Sienese Jesuit to a Roman colleague indicates that the Jesuits introduced the practice in Siena on Sundays and feast days beginning in 1563, and that by 1566 they had succeeded in spreading the practice to twenty-two other religious congregations and societies in the city.Footnote 153 Moreover, the visits by the emblems to the religious orders in the “Fanciful Dispute” parody the many methods and rules for praying, meditating, and loving God; the rules for dying; and the many privileges and indulgences afforded new religious societies such as the Augustinian Centurati. All of these objections, however, need not have been made by Protestants, but could also have been voiced by lay Catholics resentful of the Counter-Reformation asceticism being imposed upon them, or by nonbelievers resentful of the demands of religious conformity in general.