1. Introduction

In this paper, we present some new experimental data on gender agreement in a Norwegian dialect (Tromsø), collected from several groups of speakers: adults, teenagers, and three different groups of children. Our findings show considerable differences between the groups, which indicate a surprisingly rapid change taking place in the dialect that involves the loss of feminine gender marking on the indefinite article and possibly the loss of feminine gender altogether. This means that the traditional three-gender system (masculine, feminine, neuter) is replaced by a two-gender system (common, neuter). The cause of this change is presumably linked to extensive dialect contact and other sociolinguistic factors, but we argue that the nature of the change can be explained as a result of the acquisition process.

More specifically, we argue that out of the three genders, the feminine is the most vulnerable due to low frequency and extensive syncretism in the morphological paradigm with the masculine, which has been argued to be the default gender. Furthermore, we show that the acquisition of the nominal inflectional suffixes is considerably less problematic than the acquisition of gender agreement: While the definite article—which is a suffix—is typically in place from early on, the masculine indefinite article is massively overgeneralized to the feminine and neuter. Our findings thus support the distinction between declension class and gender in Norwegian suggested, for example, by Enger (Reference Enger2004) and Lødrup (Reference Lødrup2011). This means that the definite article is typically unaffected by the change. The result of this process is a simplification of the gender system (from three to two), which is accompanied by added complexity in the declension system (the new common gender now has two different declensional classes).

The paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we briefly outline the traditional three-gender system of Norwegian and also provide some historical and sociolinguistic background. In section 3, we give an overview of some relevant previous research on the acquisition of gender in various languages, including some recent studies on the acquisition of gender in Norwegian in bilingual as well as monolingual contexts (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2013a,Reference Rodina, Westergaard, Siemund, Gogolin, Edith Schulz and Davydovab). Section 4 provides the research questions and a detailed description of the methodology of the present study, while sections 5 and 6 give an overview of the results of the experimental data. In section 7, we discuss our findings in terms of processes of language acquisition and change, and section 8 is a brief conclusion.

2. Background

2.1 The Gender System of Norwegian (Tromsø Dialect)

We take the relatively standard approach to gender expressed in the much-cited definition in Hockett Reference Hockett1958:231: “Genders are classes of nouns reflected in the behavior of associated words.” This means that gender is a morphosyntactic feature expressed as agreement between the noun and other targets, such as determiners, verbs, and adjectives. Affixes on the noun itself, expressing, for instance, definiteness or case, are considered to be part of the declensional paradigm. Thus, although affixes may differ across noun classes (and therefore across genders), they are not exponents of gender by themselves (Corbett Reference Corbett1991:146). In this paper, we therefore use the term agreement generally to mean the relationship between a noun and other targets, for example, determiner-noun agreement, as in et hus ‘a house.neut’. We also make a distinction between gender agreement and concord. Concord refers to agreement correspondence across several different targets, for example, an indefinite article and an adjective, as in et grønthus ‘a.neut green.neut house.neut’. In sections 4.2, 5.3, and 7, concord is also contrasted with discord, that is, noncorrespondence between different targets, as in en grønthus ‘a.masc green.neut house.neut’.

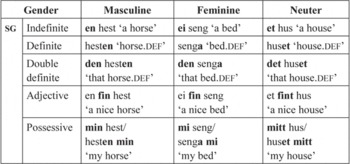

The two written standards of Norwegian, bokmål and nynorsk, both have a three-gender system with distinctions between masculine, feminine, and neuter. The bokmål standard also allows a two-gender system consisting of just common and neuter gender (see section 2.2). Just like most spoken varieties of Norwegian (see below for exceptions), the Tromsø dialect also traditionally has a three-gender system. Gender is mainly expressed within the DP, on adjectives and determiners (that is, articles, demonstratives, and possessives.Footnote 1 This applies only in the singular, as gender agreement is neutralized in the plural, for example, fine biler ‘nice cars.masc’, fine bøker ‘nice books.fem’,fine hus ‘nice houses.neut’. Table 1 gives an overview of the parts of the gender system that are relevant for the present study, illustrated by the morphology of the Tromsø dialect.Footnote 2

Table 1. The traditional gender system of Norwegian (Tromsø dialect).

As shown in table 1, the indefinite article expresses a three-way gender distinction, with en for masculine, ei for feminine, and et for neuter. This also applies to the possessives (which may be both pre- and postnominal), with the forms min, mi, and mitt in the 1st person singular (2nd person din, di, ditt, 3rd person sin, si, sitt). For virtually all adjectives there is syncretism between the masculine and feminine forms, for example, fin ‘nice’ in the masculine and feminine versus fint in the neuter.Footnote 3 The definite article in Norwegian is a suffix, that is, -en for masculine, -a for feminine, and -et for neuter. Some traditional grammars treat the definite article as an expression of gender (for example, Faarlund et al. Reference Faarlund, Lie and Vannebo1997), but according to the definition given above, the definite suffixes should be considered expressions of declension classes instead (see also Enger Reference Enger2004, Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011).Footnote 4

When a DP is demonstrative or when it is modified (for instance, by an adjective, as in den røde bilen ‘the red car’), definiteness is normally expressed twice, on a prenominal determiner as well as on the suffix. Syncretism between the masculine and feminine is also found on the prenominal determiner in double definite forms, that is, den for masculine and feminine versus det for the neuter. This is also the case for demonstratives (not shown in the table), for example, denne bilen ‘this car.masc’, denne boka ‘this book.fem’, dette huset ‘this house.neut’, as well as certain quantifiers, for example, all maten ‘all the food.masc’,all suppa ‘all the soup.fem’, alt rotet ‘all the mess.neut’. In the experiments discussed in the present paper, we focus on forms expressing gender proper (agreement with the noun) and forms expressing declension, more specifically indefinite articles and pre-nominal determiners in double definite DPs on the one hand, and definite suffixes on the other.

Gender assignment in Norwegian is traditionally viewed as non-transparent, as nouns do not provide reliable gender cues. This is in contrast to languages such as Spanish or Italian, where gender is highly predictable from morphophonological endings, that is, -o for masculine and -a for feminine. Nevertheless, Trosterud (Reference Trosterud2001) has argued that 94% of all nouns may be accounted for by 43 different assignment rules: three general rules, 28 semantic rules, nine morphological rules, and three phonological rules. He also argues that masculine is the default gender, that is, the gender that is assigned if no rule may be applied. Unfortunately, these rules are not very helpful from the perspective of language acquisition, as they typically have a high number of exceptions and also cover many classes of nouns that are infrequent in the input available to children. In fact, children's sensitivity to some of these cues has been tested in Gagliardi Reference Gagliardi2012 with negative results (more on this in section 3).

Nevertheless, three rules have been argued to have especially high predictability: Male human (for masculine gender), female human (for feminine gender), and final -e, a morphophonological cue for feminine. The latter cue is somewhat different in the (traditional) Tromsø dialect, as feminine nouns ending in -e in most varieties of Norwegian end in -a in dialects spoken in and around Tromsø (that is, Troms county). This means that there is no difference between the indefinite and definite forms of these nouns in the dialect, for example, ei dama–dama ‘a lady–the lady’. As discussed in Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2013a, there seems to be a change going on in the Tromsø dialect, as the four children investigated in that study (all born in 1992) use the two endings interchangeably in the indefinite, for example, dukke and dukka ‘doll’. The significance of this finding for the present study is discussed in section 7.

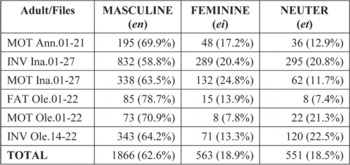

Trosterud (Reference Trosterud2001) has carried out a frequency count based on a total of 31,500 nouns in the Nynorsk Dictionary (Hovdenak et al. Reference Hovdenak, Killingbergtrø, Lauvhjell, Nordlie, Rommetveit and Worren1998): Masculine nouns clearly constitute the majority of nouns, 52%, while feminine nouns make up 32%, and neuter nouns only 16%. To our knowledge, there exists no frequency analysis based on natural spoken discourse or child-directed speech. Since frequency is an important factor in acquisition, it is crucial for our research that we have an indication of what children's input is like. We have therefore carried out a simple frequency investigation in a corpus of child language recorded in Tromsø (Anderssen Reference Anderssen2006). The corpus consists of 70 recordings of conversations between three children (aged approximately 1;8 to 3;3) and their parents and the investigators, altogether eight adults. We have conducted a search for the indefinite articles (en, ei, et) in the data of some of the adults, so that every single file in the corpus has been investigated. Table 2 shows the frequency of the three indefinite articles for the following adults: The mother (MOT) in the Ann corpus, the investigator and the mother (INV, MOT) in the Ina corpus, and the father, mother, and investigator (FAT, MOT, INV) in the Ole corpus.

Table 2. The frequency of the three indefinite articles in adult data from the Tromsø acquisition corpus (Anderssen Reference Anderssen2006).

The figures in table 2 show that the frequency counts from the dictionary only partly hold up when one considers typical child-directed speech. That is, the masculine is even more frequently attested in children's input than in the dictionary (62.6% versus 52%), while the feminine is less frequently attested (18.9% versus 32%). It also shows that there is no difference in frequency between the feminine and the neuter. Our investigation has only counted token frequencies for the indefinite article, not type frequencies of the corresponding nouns. However, we believe that this gives a relatively correct picture of what a Norwegian child is typically exposed to, as we have studied six different adults speaking to three different children across 70 different recordings.

2.2 A Brief Historical, Geographical, and Sociolinguistic Overview

Speakers of Norwegian generally speak their dialects in all situations, formal and informal. The written language has two standards, bokmål and nynorsk (see Venås Reference Venås and Håkon Jahr1993 and Vikør Reference Vikør1995 for more information about the language situation in Norway). The bokmål variety is based on the Danish language that was the written standard at the time when Norway gained its independence in 1814, and the present-day version of it is the result of a number of adaptations and Norwegianizations of Danish taking place since the first orthographic reform in 1907. In contrast, nynorsk is a written standard based on Norwegian dialects, created by the philologist, lexicographer, and poet Ivar Aasen in the mid-19th century as a real Norwegian alternative to written Danish. While nynorsk is mainly used in the Western part of the country, the bokmål variety is by far the more commonly used standard in Norway. In Troms county, where our investigation took place, only 0.1% of the children in elementary schools have nynorsk as their main written standard.Footnote 5

The three-gender system of Proto-Germanic has been lost in several of the present-day Germanic languages, including Dutch, Swedish, and Danish. These languages have generally lost the feminine gender and have developed a two-gender system consisting of common gender (masculine/feminine) and neuter. As Danish has a two-gender system, the bokmål written standard allows the use of only two genders, although the three-gender system of most spoken varieties has been introduced as an alternative. This means that nouns that are feminine in the spoken language may be used with either feminine or masculine (that is, common) declensions and gender agreement in written bokmål, as shown in 1. The version in 1b signals a somewhat more formal style.

(1)

Most dialects (and consequently also the nynorsk standard) have retained the three-gender system. The only exception to this is the Bergen dialect, which underwent a change from a three- to a two-gender system centuries ago, arguably due to extensive language contact with low German during the Hansa period (see, for example, Jahr Reference Jahr and Håkon Jahr1998, Reference Jahr2001; Trudgill Reference Trudgill and Lohndal2013). This means that the Bergen dialect only allows constructions like 1b. Forms like those in 1b were also used in a spoken variety called den dannede dagligtale ‘educated casual style’ (Torp Reference Torp, Bandle, Braunmüller and Jahr2005:1428), used by the upper classes in the 19th century (Haugen Reference Haugen1966:31). This variety was a compromise between Eastern Norwegian urban dialects and a Norwegian reading pronunciation of Danish.

More recently, Lødrup (Reference Lødrup2011) has also attested loss of the feminine in the speech of people from certain parts of Oslo. He attributes this to the spread of the educated casual style, which has influenced the traditional Oslo dialect. Lødrup has studied a corpus of adult speech consisting of altogether 142 speakers, finding that there is a difference between the age groups, the older speakers using very little feminine gender and the younger speakers using feminine gender hardly at all. He has also found that, while the indefinite article ei (feminine) is very infrequent in the data, the speakers generally still use the declensional endings of the feminine, for example, the −a suffix of the definite article.Footnote 6 This means that the pattern is the following (compare with example 1 above):

(2)

Finally, in this section, we would like to mention that Conzett et al. (Reference Conzett, Mette Johansen and Sollid2011) have attested a similar pattern in certain dialects in Northern Norway (Kåfjord and Nordreisa), spoken in areas approximately 150 kilometers north of Tromsø. This region has had extensive language contact with Saami and Kven, languages that do not have grammatical gender.Footnote 7 This language contact is argued to have caused a reduction of the gender system of the Norwegian spoken in this area from three to two genders, while the declension system is generally intact. This means that here as well, the gender and declension system of previously feminine nouns is generally as illustrated in 2.

3. Previous Language Acquisition Research

The acquisition of gender in Norwegian is largely understudied. Some early facts are reported by Plunkett & Strömquist (Reference Plunkett, Strömquist and Slobin1992) based on longitudinal data of one Norwegian child (aged 2;3–2;5) acquiring the Western Oslo dialect, which only has two genders (data from Vanvik Reference Vanvik1971). Like the Swedish and Danish children also discussed by Plunkett & Strömquist (Reference Plunkett, Strömquist and Slobin1992), the Norwegian child is found to produce occasional errors involving overgeneralization of common gender to neuter nouns, as shown by the following examples: In 3a, both the definite suffix and the possessive determiner are non-target-consistently marked for common gender. In 3b, the suffix is correctly marked for neuter, while the possessive is not. While Plunkett & Strömquist (Reference Plunkett, Strömquist and Slobin1992) only provide a few examples and no statistical evidence, these findings nevertheless indicate that gender agreement may be more vulnerable in acquisition than declensions (suffixes).

(3)

More recently, Rodina & Westergaard (Reference Rodina and Westergaard2013a) have conducted a detailed analysis of some longitudinal data from four children in Tromsø (Bentzen Reference Bentzen2000, Anderssen Reference Anderssen2006); two monolingual children (Ina, aged 2;10–3;3 and Ole, aged 2;6–2;10, both born in 1992) and two bilingual Norwegian-English children (Sunniva, aged 1;8.8–2;7.24 and Emma, aged 2;7.10–2;10.9). The examination of the children's accuracy with indefinite articles, adjectives, possessives, and prenominal determiners in double definites reveals that the acquisition of gender agreement is delayed in all four children compared to what is typically the case in other languages. The findings also show that the neuter gender is most vulnerable. For example, with indefinite DPs, which are the most problematic forms, Ina makes no errors in the masculine, but 57.8% errors in the feminine, and as many as 92.6% in the neuter. Ole makes 1.7%, 12.5%, and 21.4% errors with the masculine, feminine, and neuter, respectively. As these numbers show, there are considerable individual differences between the children (and furthermore, there is no clear difference between monolinguals and bilinguals). A qualitative analysis shows that all the children mainly overgeneralize masculine gender forms to both feminine and neuter nouns. At the same time, a discrepancy is found between the acquisition of gender agreement (for example, the indefinite article) and gender marking on suffixes (for example, definite articles). This is illustrated in the examples in 4 from Ole's data: In 4a, he produces masculine gender agreement on a neuter noun, while in 4b, which is from the same recording, he uses the target-consistent definite suffix on the same noun. This indicates that the distinction between declension versus gender marking in Norwegian may receive some psycholinguistic support from acquisition.

(4)

Further research evidence on the acquisition of gender by somewhat older children acquiring the Tromsø dialect is provided in Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina, Westergaard, Siemund, Gogolin, Edith Schulz and Davydova2013b. This is an experimental study focusing on bilingual Norwegian-Russian children, including a control group of nine mono-linguals with a mean age of 4;4, born around 2008. These children are also shown to overgeneralize masculine gender forms to the feminine and the neuter. However, in this group, it is the feminine nouns that are most problematic: The error rate with the feminine is as high as 99% for indefinite articles, while the corresponding error rate for neuter is considerably lower, 49%. Thus, according to Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina, Westergaard, Siemund, Gogolin, Edith Schulz and Davydova2013b, neither feminine nor neuter gender is acquired by the age of 4.

Finally, we consider the data in Gagliardi Reference Gagliardi2012, elicited from even older children: nine in daycare (mean age 5;1) and 11 in school (mean age 6;8). Gagliardi (Reference Gagliardi2012) is primarily concerned with how monolingual speakers of the Tromsø dialect use what she refers to as noun-internal and noun-external distributional information to assign gender to existing as well as novel nouns. With regard to noun-internal information, she identifies three gender cues that have been argued to have the most predictive power: male human for masculine, and female human and final -e for feminine (see section 2.1). With respect to the gender assignment task with existing nouns, Gagliardi observed that in the speech of these preschool and school children, feminine nouns are more problematic than masculine and neuter nouns. The error rates with the feminine nouns range between 35% and 53% depending on the cue (35% errors for the semantic cue, 46% for the phonological cue, and 53% for no cue). These errors with the feminine nouns are due to overgeneralization of the masculine gender forms. At the same time, neuter and especially masculine nouns are virtually error-free in the children's data (6% and 5% errors, respectively). Furthermore, with respect to the task with novel nouns, Gagliardi observed that the children were not sensitive to the two gender cues for feminine. In this case, neither internal nor external information (that is, indefinite articles provided by the experimenter) prevented massive overgeneralization of masculine gender.

In summary, the studies reviewed in this section show that grammatical gender is a late-acquired phenomenon in Norwegian, presumably due to the lack of transparency in gender assignment. Gender seems to be highly problematic for monolingual children at least until the age of 6. So far, there are no studies showing when gender knowledge becomes target-like. Furthermore, it is not clear what aspects of gender are most problematic for Norwegian-speaking children: While Rodina & Westergaard (Reference Rodina and Westergaard2013a) suggest that neuter is most vulnerable in two- to three-year olds, Gagliardi (Reference Gagliardi2012) and Rodina & Westergaard (Reference Rodina, Westergaard, Siemund, Gogolin, Edith Schulz and Davydova2013b) observe that 4-to-6-year olds have greater problems with the feminine. The existing research also suggests that gender agreement is considerably more complex than the declension system in the acquisition process. Finally, the high error rates at relatively late stages of acquisition could suggest that these gender facts may never be acquired by these children and that what one is really seeing is a language change in progress, involving the loss of the feminine. An important point in this respect is that the corpus data investigated in Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2013a is from children who are born 16 years earlier than the children investigated in Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina, Westergaard, Siemund, Gogolin, Edith Schulz and Davydova2013b. These unresolved issues are the main focus of the present study.

4. The Present Study

4.1 Research Questions and Goals

This study had two main goals. Our first goal was to reveal what aspects of the Norwegian gender system are most problematic for children acquiring the Tromsø dialect and how long these problems persist. In order to answer these questions, we originally wanted to compare children's mastery of masculine, feminine, and neuter gender before and after the age of 6 (5-to-6-year olds and 7-to-8-year olds). As our initial findings showed that the gender problems persisted in the older age group, we decided to investigate a group of even older children (aged 11–13) as well as a group of teenagers (aged 18–19). We also performed the same experiments with adults, in order to control for the input that children growing up in Tromsø typically receive from their parents and other caregivers.

Given that the feminine may be most vulnerable in the gender system of the Tromsø dialect, it is also necessary to investigate the status of different feminine nouns more closely. Thus, our second goal was to find out whether feminine is only late acquired or is in the process of being lost. Recall that in the previous experimental studies, 4-year olds were found to make 99% errors with feminine nouns (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina, Westergaard, Siemund, Gogolin, Edith Schulz and Davydova2013b), while in Gagliardi's (Reference Gagliardi2012) study, 4-to-7-year olds make between 35% and 53% errors. This suggests that the feminine gender may be a late acquired phenomenon, and that it does fall into place eventually. However, given that the studies use different methodologies, they are not directly comparable; we therefore wanted to test different age groups (including adults) using the same experimental method.

Furthermore, we investigated whether the use of feminine agreement could be facilitated by semantic and/or morphophonological cues which have been argued to have predictive power, that is, female human and final -e (see Trosterud Reference Trosterud2001). The latter cue would correspond to final -a in the traditional Tromsø dialect (see section 2.1). According to Gagliardi (Reference Gagliardi2012), the semantic cue may have a stronger facilitating effect than the morphophonological cue, as the children in her study make fewer errors with existing nouns denoting females than with feminine nouns ending in -e (35% versus 46%). Investigating this issue also contributes to the debate on the importance of semantic versus morphophonological cues in gender acquisition. Based on data from various languages, it has been shown that morphophonological cues are more important for children at early ages and that semantic rules take over later in development (Karmiloff-Smith Reference Karmiloff-Smith1979, Mills 1981, Levy Reference Levy1983, Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2012, Rodina Reference Rodina2014. The languages considered in these studies—French, German, Hebrew, Russian—have gender systems in which gender assignment could be argued to be (more or less) rule based.Footnote 8

The last issue that we addressed in the present study is the distinction between gender agreement (between the noun and other targets) and declension marking (on the noun itself). In previous acquisition studies (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2013a,Reference Rodina, Westergaard, Siemund, Gogolin, Edith Schulz and Davydovab), it was found that, although gender agreement is problematic for children for an extended period of time, declensional suffixes, such as the definite article, are in place from early on. In Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011 and Conzett et al. Reference Conzett, Mette Johansen and Sollid2011, which both report on a change from a three- to a two-gender system, it is shown that the change generally only affects gender, but not the declensional endings. Thus, in the present study, we tested both agreement and declension. Our research questions are summarized as follows:

1. What aspects of the gender system of Norwegian are the most problematic to acquire?

2. When is gender acquired (at 90% accuracy)?

3. Is there a distinction between gender and declension?

4. Are children sensitive to semantic and/or morphophonological cues in gender acquisition?

5. Is the feminine gender late acquired, or is it in the process of being lost?

4.2 Participants, Stimuli, and Procedure

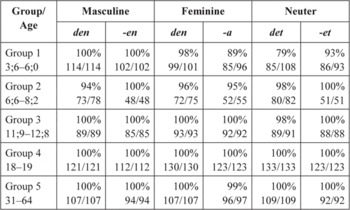

The participants in the study totalled 70 native speakers of the Tromsø dialect, including both children and adults. They were divided into five groups according to age, as illustrated in table 3. The children were born in Tromsø and grew up acquiring the local dialect. Some of them had also been exposed to other Norwegian dialects at home. The adult participants were all born in Tromsø and had lived there most of their lives. They were employees at the University of Tromsø but had no background in linguistics. The age is specified in years;months for the children (groups 1, 2, 3) and years for the teenagers and adults (groups 4, 5).

Table 3. Overview of the participant groups.

In order to answer the research questions formulated in section 4.1, we conducted two elicited production experiments: one that focused on all three genders and another that focused on feminine nouns only. The second experiment tested both a semantic and a morphophonological cue. The same experimental design was used in both tasks. This is an adaptation of a research design used in Stöhr et al. Reference Stöhr, Akpinar, Bianchi, Kupisch, Braunmüller and Gabriel2012 and Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina, Westergaard, Siemund, Gogolin, Edith Schulz and Davydova2013b. In both tasks, the materials were a series of colored pictures showing various objects depicting the target nouns. The pictures were presented on a laptop computer, and all responses were audio-recorded. In order to compare gender marking on free versus bound morphemes (that is, agreement versus declension), we elicited indefinite and double definite DPs in the same experimental setting. An example of the elicitation procedure is illustrated in 5.

(5) Pictures of a yellow and a red car shown simultaneously on the screen

The red car disappears. The picture of a yellow car remains.

The lead-in statement in 5 was carefully chosen in order not to reveal the gender of the target noun. The sentences in 6 illustrate the corresponding responses expected for feminine and neuter nouns.

(6)

Note that the experiment tests three gender forms for each item, the indefinite article, the adjective, and the prenominal determiner in the double definite DPs. This means that our study could in principle also address the question of gender assignment versus gender agreement, as defined in many recent acquisition studies on languages such as Italian and German, for example, Bianchi Reference Bianchi2013 and Kupisch et al. Reference Kupisch, Müller and Cantone2013: In cases where there is non-target-consistent agreement between the noun and the other target forms, correspondence between the different forms (concord) has been used to argue that the problem lies in gender assignment, while noncorrespondence (discord) indicates that the problem lies in agreement. However, this issue is not part of our main research focus, as the nature of the Norwegian gender system (see section 2.1) gives us reason to expect children to have problems with assignment rather than agreement. That is, gender assignment is generally nontransparent and has been found in previous studies to be late acquired (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2013a,Reference Rodina, Westergaard, Siemund, Gogolin, Edith Schulz and Davydovab), while the concord between different target forms is relatively uncomplicated (for example, there are no case forms). Thus, we assume that discord between the different targets, especially if this appears only occasionally, indicates a problem with assignment rather than agreement, in the sense that children are unsure about the gender and therefore vacillate between different forms. We return to this issue briefly in sections 5.3 and 7.

In experiment 1, we included 24 nouns distributed equally among the three genders, that is, eight masculine, eight feminine, and eight neuter nouns. The test items were presented in a randomized order preceded by a training session with three nouns, one from each gender. As shown in examples 5 and 6, the objects were contrasted with respect to color.

In experiment 2, we included 24 feminine nouns distributed equally across four subtypes of feminine nouns: nouns denoting females with a zero ending (ei heks ‘a witch’), nouns denoting nonfemales ending in -e (ei flaske ‘a bottle’), nouns with both cues, that is, denoting females and ending in -e (ei dame ‘a lady’), and nouns with neither cue, that is, denoting nonfemales and with a zero ending (ei and ‘a duck’). Note that in the traditional Tromsø dialect, the nouns ending in -e would be pronounced with a final -a, as in ei flaska ‘a bottle’ and ei dama ‘a lady’. Six neuter nouns were used as fillers. Importantly, no masculine nouns were included in the test, as we wanted to avoid any possible effect of priming. The objects in experiment 2 were contrasted with respect to both color and size.

The experiments were carried out by two investigators, a native speaker of Norwegian working as a research assistant and an advanced second language speaker of Norwegian (the first author of this paper). The order of the experiments varied, so that one group participated in experiment 1 first, while the other group participated in experiment 2 first. If the participants did not use the correct color or scalar adjective in their responses, they were never corrected. The experiments with the children were conducted in daycare centers and schools, individually in a quiet room. The experiments with the adults were conducted individually in the TROmsø Language acquisition Lab (TROLL). The adult speakers were told that the purpose of the task was to compare child and adult use of color and scalar adjectives with different nouns. This was done in order to ensure that they were not conscious of the grammatical phenomenon tested.

The recordings were transcribed by a research assistant who is a native speaker of Norwegian. We counted responses with indefinite articles, prenominal determiners, and suffixed definite articles separately. It should be noted that the number of expected responses varied for different agreement targets. In both experiments, a total of 48 responses were expected with indefinite articles (two per test item) and 24 responses with double definite forms—24 prenominal determiners and 24 suffixed definite articles. In some cases, the target noun was missing in the response and only the indefinite article or prenominal determiner was used together with an attributive adjective, as shown in 7.

(7)

Such responses are perfectly grammatical, and since the target noun was introduced in the immediately preceding context, they were included in the counts. We excluded responses where a different noun was used.

5. Results of Experiment 1: Masculine–Feminine–Neuter

5.1 Indefinite DPs

Table 4 shows the accuracy of gender agreement on the indefinite article across the five groups of participants. Figure 1 displays the same results. It is clear that the children (groups 1, 2, 3) do not have any problem with masculine nouns, producing the indefinite article en in virtually all cases. In contrast, feminine ei is highly problematic, and there is no increase in accuracy across the three age groups: The accuracy for the preschool children is 15%. This rate decreases for the school children, to 9% and 7% in groups 2 and 3, respectively. A binomial mixed effects model reveals no age effect in the three groups of children: p=0.1 and p=0.2 for group 2 versus 1 and group 3 versus 1, respectively. In contrast, the adults in group 5 use the feminine indefinite article ei as often as 99%, while the 18-19-year olds (group 4) constitute a middle group, using feminine ei 56%. The same statistical model shows that the teenagers (group 4) and adults (group 5) are significantly different from the child participants: p < 0.05 for both age groups.

Table 4 also shows that neuter is not completely target-consistent for the three groups of children, with the preschoolers (group 1) making 21% errors and the older children in groups 2 and 3 making occasional errors (8% in both groups), a proportion which does not exceed the 10% experimental error margin. Thus, there is an improvement with age in the three child groups. This turns out not to be statistically significant (p = 0.9 across the three age groups), which may be due to the generally high accuracy and the wide age range within the groups. Nevertheless, the statistical analysis reveals that there is a clear effect of noun class, in that the children's accuracy rates for feminine ei is significantly lower than for neuter et: p < 0.0001 for groups 1, 2, 3.

Table 4. Experiment 1: Accuracy of gender agreement on indefinite articles.

Figure 1 Experiment 1: Accuracy of gender agreement on indefinite articles.

The mistakes made by the children with feminine and neuter nouns are an overgeneralization of the masculine gender, as demonstrated by the examples in 8. This confirms previous findings based on both corpus and experimental data (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2013a,Reference Rodina, Westergaard, Siemund, Gogolin, Edith Schulz and Davydovab).

(8)

In order to establish the age at which neuter gender is fully mastered by these children, we divided our child participants in groups 1 and 2 into three smaller groups: 3-to-4-year olds (N=9), 5-to-6-year olds (N=8), and 7-to-8-year olds (N=10). This allows us to follow the children's development with the neuter form et more closely over time. The accuracy rates for the respective subgroups are 82%, 79%, and 91%. The statistical analysis shows no age effect (p 0.3 binomial mixed effects model). Nevertheless, the data suggest that neuter is unstable between the ages of 3 and 6, while there is a considerable increase in accuracy rates in the oldest group, the 7-to-8-year olds. This can be taken as an indication that neuter is not fully mastered until the age of 7, that is, when accuracy reaches a level above 90%. This conclusion is also supported by the results on the neuter prenominal determiner det discussed in section 5.2.

Finally, we need to consider the feminine nouns more closely, both with respect to individual speakers and specific nouns. The individual speaker preferences with the feminine nouns are summarized in table 5. As one can see, the majority of the child speakers in groups 1, 2, 3 use the masculine form en exclusively (altogether 30/39), while three use only ei and six use both forms. In contrast, all except one of the adult speakers in group 5 (13/14) use only ei, and this one speaker uses both ei and en. Finally, among the 18-to-19-year olds (group 4), five speakers use en exclusively, seven use only ei, and five use the two forms interchangeably.

Table 5. Experiment 1: The use of the indefinite article ei (fem) and en (masc) with feminine nouns, N participants/Total.

This means that the majority of speakers (58/70) only use one of the forms, either masculine or feminine. A closer inspection of the 12 speakers who produce both ei and en reveals that all of these also have clear preferences: The one adult speaker mixing the two forms produces only two occurrences of en, both of them with the same noun, thus displaying the same preference for the feminine as the other adults. The five teenagers (group 4) who use both forms also turn out to clearly favor one of them, as two prefer the masculine and three the feminine. In group 1, six of the preschool children use a mixture of forms, only one of them showing a preference for the feminine, while the remaining five favor the masculine. Thus, out of the 12 participants who use a mixture of forms, five turn out to have a clear preference for the feminine (one adult, three teenagers, and one child in the youngest group), while the rest have a preference for the masculine (two teenagers and five of the youngest children). The occasional examples that deviate from the preference do not seem to be linked to any particular nouns in the experiment.

5.2 Double Definite DPs

In double definite DPs, we considered gender agreement on the prenominal determiner as well as the form of the declensional class marker on the definite suffix. Recall that while suffixes alternate between -en, -a, and -et for masculine, feminine, and neuter nouns, respectively, there are only two forms of the prenominal determiner: den for masculine and feminine, and det for neuter nouns. Given the syncretism between the masculine and feminine, it is not surprising that the children's accuracy rates are roughly 100% for the determiner den in all three age groups, as illustrated in table 6. There is thus no difference between child and adult speakers in this respect.

In contrast, the accuracy rate with the neuter form det is somewhat lower for the youngest children (group 1)—79%, which is identical to what was observed for the neuter indefinite article et (compare table 4). Similarly, the accuracy rates for neuter det increase with age and reach the near-target level of 98% in groups 2 and 3. Yet, the differences between the three child age groups are not significant: p=0.9 (binomial mixed effects model). As expected, the errors in the neuter result from overgeneralization of common gender den.

Table 6. Experiment 1: Accuracy of gender marking in double definite DPs: prenominal determiners and suffixes.

Table 6 also shows that the use of suffixes is unproblematic in the masculine, the accuracy rates being 100% across all participant groups. Moreover, the suffixes are also produced at a target-consistent level in the feminine and neuter, with only slightly lower accuracy rates for the youngest children (group 1), at 89% and 93% respectively. This is in stark contrast to the performance on the indefinite article ei, which was used infrequently, especially by the children (groups 1, 2, 3), but also by the teenagers (group 4). A comparison of the accuracy rates for the feminine is illustrated in figure 1, where the contrast between the indefinite article ei and the suffixed definite article -a is highly significant in groups 1, 2, 3 (p < 0.0001 for all three age groups). This result also confirms previous findings (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2013a,Reference Rodina, Westergaard, Siemund, Gogolin, Edith Schulz and Davydovab).

Figure 2 Experiment 1: Comparison of accuracy rates for the feminine.

In the neuter, illustrated in figure 1, the accuracy for the suffixed definite article -et is contrasted with the accuracy for the indefinite article et. This is most striking in group 1 and turns out to be highly significant (p < 0.0001). There is also a highly significant contrast between the suffix and the neuter prenominal determiner det in group 1 (p=0.005). Both types of contrast disappear already at the next stage, in group 2 (p=0.995 for et versus -et and p=0.984 for det versus -et).

Figure 3 Experiment 1: Comparison of accuracy rates for the neuter.

The examples in 9 and 10 illustrate the contrast between gender marking on the indefinite article and the mastery of the declensional suffix with feminine and neuter nouns in the children's production. In both examples, the child uses the masculine form of the indefinite article, but the correct suffix on the same lexical item. The pattern in 12 is characteristic of all children (groups 1, 2, 3) as well as the teenagers (group 4).

(9)

(10)

In order to investigate the development of the neuter over time and to compare the children's gender marking on the prenominal determiner with that on the indefinite article, we again divided our child participants in groups 1 and 2 into three smaller groups: 3-to-4-year olds, 5-to-6-year olds, and 7-to-8-year olds. The accuracy rates are 80%, 82%, and 97%, respectively. This is similar to the developmental pattern for the indefinite article (see section 5.1). A binomial mixed-effects model also confirms that these differences are statistically significant: p=0.0165. On the basis of the similarities in the developmental pattern of the indefinite article and the prenominal determiner, we may conclude that neuter gender is mastered around the age of 7.

5.3 Gender Concord versus Discord

In this section, we address the question of consistency of gender agreement across the different targets, that is, what is often referred to as the issue of assignment versus agreement (for example, Bianchi Reference Bianchi2013, Kupisch et al. Reference Kupisch, Müller and Cantone2013). As mentioned above (sections 2.1 and 4.2), we refer to this as concord versus discord in the different agreement forms. A detailed investigation of the child data (groups 1, 2, 3) in experiment 1 reveals that, in the neuter nouns, there are 27/244 (11%) examples of gender discord and 12/244 (5%) examples of erroneous gender concord, while there are 205/244 (84%) examples of correct concord. Thirteen out of the 27 discord errors involve an erroneous form of the indefinite article (that is, en) combined with the correct form of the prenominal determiner (that is, det), illustrated in 11a, while there are 10 examples where the correct form of the indefinite article (that is, et) is combined with the erroneous form of the prenominal determiner (that is, den), illustrated in 11b. Finally, there are four cases of discord that involve both correct and erroneous use of the indefinite article, illustrated in 11c. The majority of the discord errors (63%, 17/27) occur in the speech of the preschool children (group 1).

(11)

In the masculine, there are 10/275 (4%) examples of discord and 265/275 (96%) examples of correct concord. There are no examples of erroneous concord in the masculine. In the feminine, there are 19/236 (8%) examples of discord, 197/236 (83%) examples of erroneous concord, and only 20/236 (9%) examples of correct concord.

Thus, the preschool and school children in our study occasionally show individual item variation, using the same noun both with correct and erroneous gender markers. In our view, the low number of examples with gender discord in the child data indicates a problem with gender assignment, generally in identifying which nouns are neuter and which nouns are not. Thus we suggest that the children generally do not have a problem with what is often referred to as gender agreement, as the majority of items display concord throughout. Interestingly, even the discord cases like those illustrated in 11a,b present partial concord within the DP, as there is agreement between the indefinite article and the adjectival modifier. This is characteristic of all cases of discord in the child data.

Our calculations in previous sections are based on all responses, including the ones that display gender discord. This may of course be somewhat misleading, as one of these forms is thus counted as correct, while the mismatch between the forms indicates that the child has not fully mastered the gender of that particular noun. However, we believe that the low number of examples with gender discord in the child data indicates that the children generally do not have a problem with what is often referred to as gender agreement.

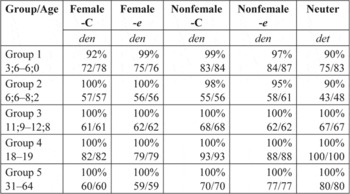

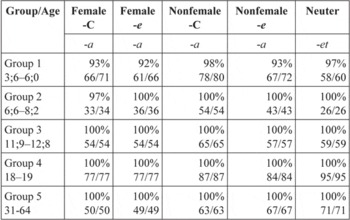

6. Results of Experiment 2: Feminine Noun Classes

Experiment 2 investigated four different classes of feminine nouns, varying with respect to a semantic and a morphophonological cue (female referent and the ending -e). Table 7 shows the use of the feminine indefinite article ei with these four subtypes of feminine nouns, and this is also illustrated in figure 1. The results are similar to what was found in experiment 1. The children in groups 1, 2, 3 use ei very infrequently, only between 10% and 21% for the four subclasses of nouns. Furthermore, there seems to be no age effect in the child data.

In contrast, the adults use the feminine indefinite article ei 100%, regardless of the noun class. The teenagers, again, constitute a middle group and use ei at a rate varying between 63% and 71%. Comparing the results for the feminine nouns to the results for the neuter fillers (the indefinite article et), it is evident that there is a clear difference between the two genders: The neuter is only slightly problematic for groups 1, 2 (the youngest children), being attested at 87% and 89%, respectively. By age 11–13 (group 3), the neuter has fallen into place, being attested at 99% (compared to only 10–18% accuracy for the feminine nouns at this stage). Thus, there is some development with respect to the accuracy with neuter nouns in the data of the children. This is also similar to what was found in experiment 1, although the accuracy rate for the neuter nouns is slightly higher in experiment 2 (87% versus 79% for the participants in group 1). However, as in experiment 1, the differences between groups 1, 2, 3 are not significant (p=0.891 for group 2 and p=0.903 for group 3, compared to group 1).

Table 7. Experiment 2: Accuracy of gender agreement on indefinite articles.

Figure 4 Experiment 2: Accuracy of gender agreement on indefinite articles.

Figure 4 also shows that the accuracy rates for feminine nouns denoting females (the first two columns) are somewhat higher than for nouns referring to nonfemale items (the next two columns) in groups 1, 2, 3, 4. A binomial mixed-effects model reveals that semantics has a weak effect in our data, in that the accuracy rates for the two groups of nouns with female reference are significantly different from the accuracy rates for the groups with nonfemale reference (p=0.0025). However, there is no difference in the accuracy rates for feminine nouns ending in

-e (the second and fourth columns) versus nouns ending in a consonant (the first and third columns) in any of the groups of speakers. This observation is also confirmed by the statistical analysis (p=0.8110). Thus, while semantics seems to have a weak effect on gender marking, morphophonology clearly does not. The noneffect of the morphophono-logical cue may be related to the change in the dialect from the -a to the standard -e ending, mentioned in section 2.1. We return to this in section 7.

Again, we look at some details behind the overall figures. Table 8 demonstrates the individual speaker preferences for all four subclasses of feminine nouns. As in experiment 1 (table 5), the majority of children (groups 1, 2, 3) prefer to use only the masculine form en (25/39 speakers). In contrast, all the adult speakers in group 5 use only the feminine form ei. Among the 18-to-19-year olds (group 4), the majority (10/17) use ei and en interchangeably. Thus, the children are very different from the adults, while the production of the teenagers is, yet again, somewhere in between.

Table 8. Experiment 2: The use of the indefinite articles ei (fem) and en (masc) with feminine nouns, N participants/Total.

Our results for double definite DPs in experiment 2 are identical to our findings in experiment 1: In the feminine nouns, both the prenominal determiner den and the suffix -a are used roughly 100% across all subclasses of nouns by all children and adults, while there is a slight delay in the neuter determiner in the two youngest groups of children. This is shown in tables 9 and 10.

Table 9. Experiment 2: Accuracy of gender marking on the prenominal determiner in double definite DPs.

Table 10. Experiment 2: Accuracy of suffixal forms in double definite DPs.

Summing up, the results from experiment 2 confirm our findings from experiment 1 that feminine gender forms are rarely used by the children, virtually always used by the adults, while the teenagers constitute a middle group. Furthermore, the morphophonological cue (-e) has no influence on gender agreement, while the semantic cue (female reference) may have a slight effect.

7 Discussion

The research questions for this study were formulated in section 4 and are repeated here for convenience:

1. What aspects of the gender system of Norwegian are the most problematic to acquire?

2. When is gender acquired (at 90% accuracy)?

3. Is there a distinction between gender and declension?

4. Are children sensitive to semantic and/or morphophonological cues in gender acquisition?

5. Is the feminine gender late acquired, or is it in the process of being lost?

The first main goal of this study was to investigate what aspects of the Norwegian gender system are most problematic for children acquiring the Tromsø dialect and determine how long these problems persist. In order to answer the first two research questions, we considered data from child participants within an age range between 3;6 and 12;8. Our findings confirm the observations made in recent experimental studies (Gagliardi Reference Gagliardi2012, Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina, Westergaard, Siemund, Gogolin, Edith Schulz and Davydova2013b) that the feminine is the most vulnerable gender. In fact, our results show that feminine gender agreement is hardly produced at all, not only in the data of the preschool children, but also in the production of school children up to the age of almost 13. Furthermore, there is no age effect for feminine nouns (table 4). Neuter agreement is also problematic, but to a much lesser extent. For example, in the youngest age group (3;6–6;0, group 1), where the children make most agreement errors in the neuter, there is a sharp contrast between the children's accuracy rates for the neuter and the feminine, 79% versus 15% respectively. In fact, the accuracy rates for gender agreement on the feminine indefinite article decrease with age, from 15% in the 3-to-6-year olds to 9% in the 6-to-8-year olds and only 7% in the 11-to-12-year olds. Although this difference was not statistically significant, we think that these differences should neverthe-less be explained: The younger children are presumably more exposed to input from their parents, who produce the feminine form 100%. In contrast, older children receive more of their input from other children, and this accumulates over time. From this perspective it is not surprising that older children in fact produce less of the feminine forms, especially if what is observed here is a change in progress (see below).

A comparison of the agreement production on the indefinite article in smaller groups (3-to-4-year olds, 5-to-6-year olds, and 7-to-8-year olds) reveals that there is an increase in target-consistent production in the neuter from around 80% at the younger ages to 91% at age 7–8. The same effect is observed for gender agreement on the prenominal determiner det, with an increase from 80% in 3-to-4-year olds to 82% in 5-to-6-year olds and 97% in 7-to-8-year olds (see section 5.2). Thus, based on this developmental pattern, we conclude that neuter agreement falls into place (at 90% target-consistent production) around age 7, which is quite late compared to what has been found for other languages. This delay can be attributed to the opacity of gender assignment in Norwegian and corresponds to what has been found for Dutch (another language with arbitrary gender assignment), where neuter gender has been shown to be problematic until approximately the age of 6 (Blom et al. Reference Blom, Poliŝenska and Weerman2008, Tsimpli & Hulk Reference Tsimpli and Hulk2013, Unsworth et al. Reference Unsworth, Argyri, Cornips, Hulk, Sorace and Tsimpli2014).

Interestingly, neuter gender marking on indefinite articles is acquired early in German, by age 3 (Müller Reference Müller and Meisel1990, Reference Müller, Unterbeck and Rissanen1999), despite the fact that grammatical gender is relatively opaque (Hopp Reference Hopp2012).Footnote 9 As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, this fact could be explained by differences in methodology: The German studies are based on spontane-ous production, while the Dutch data, as well as our present study, come from elicitation experiments. One should also consider individual differences: Recall from section 3 that errors with the neuter indefinite article et constitute 21.4% in the corpus of the Norwegian child Ole (2;6–2;10), but as much as 92.6% in the data of the child Ina (2;10–3;3).

Related to the transparency of the nominal system is the question of gender assignment versus gender agreement, as discussed in several recent studies, for example, Bianchi Reference Bianchi2013 and Kupisch et al. Reference Kupisch, Müller and Cantone2013. According to these studies, non-target-consistent correspondence between different gender forms is due to problems with gender assignment, and a mismatch between forms is due to problems with gender agreement. As mentioned above (section 4.2), we do not think that this distinction can be made for the Norwegian data: Given previous findings (for example, Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2013a,Reference Rodina, Westergaard, Siemund, Gogolin, Edith Schulz and Davydovab) as well as the nature of the system (nontransparent assignment, uncomplicated agreement), we assume that it is gender assignment that is difficult for children to acquire, not gender agreement (see section 4.2). Our findings show that concord is generally target-consistent in the majority of cases (see section 5.3), and we thus have no reason to claim that the children have problems with gender agreement. Instead, we interpret the occasional discord found in the data as a sign of uncertainty on the part of the child with respect to the gender of the noun (that is, assignment), which results in a certain vacillation of the forms used.

With respect to research question 3, our findings also support the distinction between declension class and gender in Norwegian (see Enger Reference Enger2004 based on diachronic evidence, Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011 based on corpus data from the Oslo dialect, and Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2013a based on spontaneous child data). Our new empirical data show that, while the acquisition of indefinite articles is highly problematic with feminine nouns and to some extent with the neuter, the acquisition of bound morphemes, that is, definite articles, is nearly error free. In the feminine, this is true for all three age groups of children. As shown in table 4, group 1 uses the feminine indefinite article ei only in 15% of cases, group 2 in 9% of cases, and group 3 in 7% of cases, while the suffixed definite article -a is used in 89%, 95%, and 100% of cases by the same children (table 6). In the neuter, the contrast between the indefinite and definite articles is most clear for the youngest children (group 1): 79% and 93%, respectively. This contrast is also observed in experiment 2 (tables 7 and 10). Similarly, in the data from the 18-to-19-year olds, the unstable use of the feminine indefinite article is combined with a 100% usage of the definite -a in both experiments.

Our fourth research question concerned sensitivity to the two gender cues, female reference versus the ending -e. A difference in accuracy rates between these two noun groups in the child data would indicate that one might be easier to acquire than the other; if the same difference is found in the data from the teenagers, this would indicate that there is a change taking place, affecting one subgroup of feminine nouns more than others. Our results show that, although the difference between the two sets of nouns is slight, it is nevertheless statistically significant, indicating that female reference is a stronger cue than the ending -e (see below for a possible explanation of this). This is surprising, given that previous research has shown that children are more sensitive to morpho-phonological than semantic cues at an early age.

As we have only tested six nouns in each group and no nonce words, an alternative analysis is that this difference is simply related to lexically stored gender for individual items in the experiment, and thus, further research is needed to resolve the issue of cue strength. In any case, our results correspond to the findings in Gagliardi Reference Gagliardi2012, where the children used the feminine indefinite article slightly more with nouns denoting females than with nouns ending in -e (46% versus 35%). As the difference between the two groups of nouns is also found in the production of older children and teenagers, we cannot conclude much with respect to acquisition because the children are clearly exposed to mixed input. The teenager data also indicate that subgroups of feminine nouns are changing at slightly different rates. This corresponds to general findings that both acquisition and change take place in small steps (for example, Westergaard Reference Westergaard2009, Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2012).

This leads us to the other main goal of our study, corresponding to the last research question, that is, whether gender is late acquired in Norwegian or whether there is a change in progress. The two experi-ments reported here indicate that it is both. That is, Norwegian children have massive problems with gender, both in the feminine and the neuter. In addition, while there is an age effect found for neuter, indicating that children do learn this at some stage (around age 7), this is not attested for the feminine nouns, where there is no development across the three age groups (3;6–12;8); there is, in fact, a decrease in accuracy. This indicates that the feminine gender is in the process of becoming lost in the Tromsø dialect.

Some caution is of course necessary here: As there is syncretism between the feminine and masculine forms of adjectives and the prenominal determiner in double definites, our study has only considered a single gender form, the indefinite article ei. Thus, we may only safely conclude that the feminine indefinite article is disappearing. The result of this could simply be that the syncretism in the masculine and feminine paradigms now also includes the indefinite article, en being used for both genders. In order to be able to conclude that the feminine gender is truly disappearing, we would have to investigate other gender forms where there is no syncretism (yet), the main candidates being possessives and the adjective liten/lita/lite ‘little’ (see section 2.1 and note 1). We must leave this for further research. In any case, this study seems to be capturing a change that has already taken place in other Germanic languages and some dialects of Norwegian (see section 2.2), namely, the loss of feminine gender forms. Surprisingly, this change is taking place relatively rapidly, as children up to the age of almost 13 are clearly distinct from their parent generation, adults in their thirties and forties.

It is well known that many changes have taken place in the Tromsø dialect in the last 35–40 years (for example, Bull Reference Bull and Håkon Jahr1990, Nesse & Sollid Reference Nesse and Sollid2010). During this time, the population has more than doubled (from about 30,000 in 1970 to a little over 70,000 today), and the city has seen a considerable influx of people from other dialect areas, especially educated speakers from Eastern Norway. Furthermore, there has also been a certain influence of immigrants in recent years, that is, second language learners of Norwegian. These speakers are typically taught a written version of Norwegian which only has common and neuter gender. Furthermore, most of the recent changes in the Tromsø dialect have been in the direction of Eastern Norwegian, and given that the main written variety (bokmål) may be used with only common and neuter gender, the feminine seems to have become increasingly linked to something regional, less prestigious, and possibly old fashioned. In fact, the older school children (group 3) seem to be aware of this. For instance, one of them mentioned after the experiment that using the feminine form ei is considered “uncool” in that age group. This means that the loss of the feminine would proceed in the same direction as other changes currently taking place in the dialect, that is, toward a more standard variety. Finally, a social change that may have had an effect on the language is that most children today are in full-time daycare from the age of approximately 1. This means that children are exposed to input from other children to a much larger extent than, say, 30 years ago—that is, to input produced by speakers who have not fully mastered the gender system of the language. Thus, there seem to be a number of external, social factors that may have contributed to the current simplification of the gender system from three genders to (possibly) only two.

However, the language-external factors cannot explain why it is the feminine and not the neuter that is disappearing. In Rodina & Westergaard's (Reference Rodina and Westergaard2013a) corpus study, it was argued that frequency plays an important role in the acquisition process of a language with a nontransparent gender system such as Norwegian, as in the child data, the most frequently occurring forms were always overgeneralized to less frequently occurring forms. Based on the dictionary frequency counts in Trosterud Reference Trosterud2001, Rodina & Westergaard's (Reference Rodina, Westergaard, Siemund, Gogolin, Edith Schulz and Davydova2013b) experimental study also predicted that the neuter should be the most vulnerable gender in Norwegian, due to its overall low frequency. However, in that study, the data showed that the children had more problems with the feminine, findings that are now confirmed by the present study. In section 2.1, we presented a frequency count based on child-directed speech, showing that the feminine and neuter genders are attested with equally low frequencies, approximately 18–19%, while the masculine is more than three times as frequent (see table 2). These numbers may go some way toward explaining why the neuter is not more vulnerable than the feminine.

According to the frequency counts in child-directed speech then, the feminine and neuter genders should be equally vulnerable. This is clearly not the case, as indicated in the present study—as well as in the historical data from other Germanic languages and dialects showing that it is the feminine gender that is lost (see section 2.2). One must therefore consider the variation and complexity in the agreement forms for the three genders. As shown in section 2.1, the feminine shares some agreement forms with the masculine, that is, the prenominal determiner in double definites (as we have seen in this study), as well as adjectival forms and demonstratives. This means that while the neuter forms are salient and clearly stand out as something special, it is much more difficult to distinguish the feminine and the masculine in the acquisition process. In the competition between masculine and feminine, frequency again becomes a factor, as the masculine is considerably more frequent than the feminine in child-directed speech. The findings from the present study thus support previous claims in the literature that frequency does play a role in acquisition but only in combination with other factors such as complexity or economy (Westergaard & Bentzen Reference Westergaard and Bentzen2007, Roeper Reference Roeper2007, Anderssen et al. Reference Anderssen and Westergaard2010, Anderssen & Westergaard Reference Anderssen and Westergaard2010).

Another reason why the feminine may be lost in the Tromsø dialect (suggested to us by Øystein A. Vangsnes, personal communication) is that the morphophonologial cue for feminine is also disappearing, in that the relevant feminine nouns are changing the ending in the indefinite from -a to -e (see section 2.1). That is, feminine nouns that used to end in -a, such as ei dama ‘a lady’, ei skjorta ‘a shirt’, ei pæra ‘a pear’, are now often pronounced with the -e ending: ei dame, ei skjorte, ei pære (see Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2013a). Because of the special status of the -a ending, the ending -e in this dialect has traditionally been a cue for masculine (for example, en pinne ‘a stick’, en bolle ‘a bowl’, en vase ‘a vase’). This means that the new form of these originally feminine nouns contributes to their change to masculine gender. In order to find out whether the ending of these nouns could be a factor affecting the choice of gender form, we searched the results of experiment 1, which contained five relevant nouns in this category: bøtte/bøtta ‘bucket’, kake/kaka ‘cake’, kåpe/kåpa ‘coat’, såpe/såpa ‘soap’, and dyne/dyna ‘blanket’. This search revealed that the new -e forms are produced 100% (51/51), 97% (73/75), 98% (100/102), 90% (126/130), and 79% (81/103) across all five age groups. This means that the change in the noun endings clearly precedes the loss of the gender forms: For example, the adults produce the old -a form only 21%, but the feminine indefinite article ei 99% (see table 4). Nevertheless, these results also show that there is a general correlation between the ending and the gender form used, in that the more the speakers use the old -a form, the more they also use the feminine gender form.

With respect to the distinction between gender agreement and declensional forms, the present study has confirmed findings attested in previous work: Bound morphemes such as the declensional suffixes are early acquired, while gender agreement on targets other than the noun itself are typically overgeneralized and become target-consistent relatively late in the acquisition process (around the age of 7). When a historical change is taking place, therefore, the gender forms are much more vulnerable than the declensional endings. This means that aspects of the acquisition process may explain the pattern found in other dialects that have already undergone the change, that is, Oslo (Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011) and Nordreisa and Kåfjord (Conzett et al. Reference Conzett, Mette Johansen and Sollid2011; see section 2.2). In these dialects, feminine gender agreement has been lost, while the declension is generally retained, as shown in 2, repeated here for convenience as 12:

(12)

This means that the result of this process is a simplification in the gender system from three to two genders: common and neuter. However, this simplification is accompanied by an added complexity in the declension system, as common gender nouns now have two declensional patterns, which is illustrated in 13.

(13)

The pattern in 13a corresponds to the originally masculine nouns and the one in 13b to originally feminine nouns.

8. Summary and Conclusion

In this article, we have investigated the production of gender and declension in a Norwegian dialect (Tromsø) in five different age groups of speakers: preschool children, two groups of school children, teenagers, and adults. Two experimental studies have been carried out, testing the use of indefinite articles and double definite forms, one focusing on all three genders, the other on four subgroups of feminine nouns expressing two cues: female reference and the ending -e. Based on the nature of the Norwegian gender system as well as previous research, our main research questions concerned the following issues: Identification of the main problems in gender acquisition, the age of acquisition, the distinction between gender and declension, sensitivity to gender cues, and the question of whether or not there is a historical change in progress (loss of the feminine).

The findings show that there is considerable overgeneralization of masculine forms in the child data to both the feminine and the neuter, arguably due to the lack of transparency in the system. The neuter gender seems to be acquired (at 90% accuracy) around the age of 7, making gender a late acquisition in Norwegian compared to other languages. In contrast, the feminine gender (represented by the indefinite article ei) is hardly used at all in the children's production, while the adults use it 100% and the teenagers around 60–70%. At the same time, declensional endings (represented by the suffixal definite article) are acquired early in all three genders. With respect to the sensitivity to gender cues, we find that nouns with female reference appear somewhat more often with feminine forms than nouns ending in -e. We interpret these findings as indicating an ongoing change in progress that involves loss of the feminine indefinite article (and possibly feminine gender altogether), and that affects subclasses of feminine nouns at slightly different rates. The change is presumably due to sociolinguistic factors, but we argue that the nature of the change is due to the process of language acquisition, the relevant factors being syncretism, frequency, lack of transparency, as well as early acquisition of declensional forms (bound morphemes) compared to agreement. The result of this ongoing change is a simplifi-cation in the gender category and a corresponding added complexity in the declensional system.